How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming

by

Mike Brown

Published 7 Dec 2010

It even included a footnote that clearly stated, “The eight planets are: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune,” and that Pluto and Xena, along with the asteroid Ceres, were to be called “dwarf planets,” a term no one had ever heard before. The resolution was clear to point out that dwarf planets are not planets, which I found an odd use of the English language. The first question from the press: “Dwarf planets are planets, right?” No, I explained. The resolution was pretty clear. There are eight planets; dwarf planets, of which there might be hundreds, were clearly not planets. But how could something be called a dwarf planet yet not be a planet? they wanted to know. A blue planet is a planet, right?

…

Particularly amusing to me was the complaint about the phrase dwarf planet. By the simple rules of grammar, a dwarf planet is a planet, they would say. The fact that the IAU would say that a dwarf planet is not a planet demonstrates that the entire decision must be wrong. What no one making these arguments remembers—or admits to remembering—is that the only people who liked the phrase dwarf planet at first were the ones who hoped that it would save Pluto when the other planets were renamed “classical planets.” Yet Resolution 5B was a specific vote on this issue, and it clearly stated that dwarf planets are not planets—just as Matchbox cars are not cars, stuffed animals are not animals, and chocolate bunnies are not bunnies.

…

Could you not think of a new word which doesn’t exist in the dictionary so that it doesn’t have any baggage, and instead of calling it “dwarf planet,” use some word, since it’s an entirely new thing.… What you need is a new word rather than combination of old words; but a planet is a planet and so is a dwarf planet from a schoolmaster point of view. I was feeling punchy and kept interjecting. “Yeah, he is right,” I muttered. “ ‘Dwarf planet’ is a dumb phrase. For years we’ve called things like Pluto and Xena ‘planetoids’—planetlike. That was a perfectly good word yesterday. But they’re trying to be sneaky, they are. ‘Dwarf planet’ is dumb, but they need it so Pluto can become a planet with 5B.” The press at this point began to think that I was perhaps as crazy as all of the astronomers arguing over punctuation in Prague.

The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets

by

Alan Boss

Published 3 Feb 2009

Given the low mass of the central object, it was not clear whether this “planet” should be called a planet, but the fact that planetary-mass objects orbited even brown dwarfs was a strong indication that super-Earths could form just about anywhere there was a disk of raw material. June 11, 2008—The IAU decided to tidy up some remaining business from the 2006 vote in Prague to demote Pluto from planethood to a new category of dwarf planets. Henceforth, Pluto and Eris would be officially known as plutoids, the IAU name for dwarf planets in the outer solar system. Ceres would remain as simply a dwarf planet, with no further laurels for its résumé. June 12, 2008—The reaction to the IAU’s plutoid decision was swift and harsh, as might be expected for such a high-stakes issue. Mark Sykes and Alan Stern declared that the IAU’s decision should be ignored, and Stern hinted that the IAU could be replaced with a new organization, in effect equating the IAU with the League of Nations, which was replaced by the United Nations after World War II.

…

Within a few days, they had garnered the support of 400 irate planetary scientists, students, and engineers and were planning to bring up the question of Pluto again at the next IAU General Assembly, scheduled for 2009 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ceres had been provisionally promoted to full planethood for a little over a week in Prague, but now Ceres was merely a dwarf planet, along with Pluto and several others, while Vesta remained a lowly minor planet. It was an outrageous turn of events for the Dawn Mission team. September 13, 2006—If Pluto was now a dwarf planet, so was Xena. Michael Brown was thus free to suggest proper names for Xena and Gabrielle.

…

Resolution 5B was voted down by a margin of about 3 to 1. General applause arose once Resolution 5B was pronounced dead on arrival. Pluto was no longer a planet after that second vote. Now there were only eight. Resolution 6A proposed that Pluto should be called a “dwarf planet,” and this resolution passed by a vote of 237 to 157. Resolution 6B said that dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt should be called “plutonian objects.” Plutonian objects? “Plutonian objects” was offered as an improvement on the previous suggestion of “plutons,” which, it turned out, had been claimed long ago by geologists as a word meaning a large underground body of once-molten rock, to the dismay of the astronomers who learned this bit of geological terminology only after making their “pluton” suggestion known to the entire world, thereby managing to enrage otherwise uninterested geologists and enlist their support in the battle against Pluto and the Plutons.

Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto

by

Alan Stern

and

David Grinspoon

Published 2 May 2018

In late February 1991, the SSES was asked to pass judgment on the concept of a Pluto mission. They had received the Pluto 350 report and a document written by Alan, Fran, and colleagues describing the detailed scientific rationale for exploring Pluto and presenting a list of scientific questions that Pluto 350 could resolve. A sampling of those questions included: How does Pluto compare with Neptune’s planet-size moon, Triton? Are they really twins left over from an early massive population of icy dwarf planets? Is Pluto’s surface composition as varied as its surface markings seem to indicate? Is it really made out of completely different materials in different areas?

…

Also in that color-stretched view, Cathy noted that Pluto’s north pole could be seen to be more yellow than the rest of the planet. Randy Gladstone, also from SwRI and the head of the New Horizons atmospheres science theme team, then reported that Pluto’s diameter had been measured to be 1,472 miles (later revised upward to 1,476 miles): larger than almost anyone had predicted. Alan then took pleasure in pointing out that this meant Pluto was, after all, larger than any other of the small planets in the Kuiper Belt, laying to rest the hope by some that dwarf planet Eris was larger than Pluto. As to those hoping Pluto was the second-largest body in the Kuiper Belt, Alan declared to the combined in-person and broadcast audience, “Well, now we can dispose of that.”

…

eCover design by LeeAnn Falciani eCover image of Pluto courtesy of NASA/SwRI; star field © zitane/Shutterstock The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows: Names: Stern, Alan, 1957– author. | Grinspoon, David Harry, author. Title: Chasing New Horizons: inside the epic first mission to Pluto / Alan Stern and David Grinspoon. Description: New York: Picador, [2018] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017060114 | ISBN 9781250098962 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781250098986 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Space flight to Pluto. | New Horizons (Spacecraft) | Pluto probes. | Pluto (Dwarf planet)—Exploration. Classification: LCC TL799.P59 S74 2018 | DDC 629.43/54922—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017060114 Our ebooks may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use.

Fire and Ice: The Volcanoes of the Solar System

by

Natalie Starkey

Published 29 Sep 2021

This wasn’t very informative. New Horizons was launched to get up close to Pluto. Despite it being the ninth planet in the Solar System at the time of launch in 2006, before being demoted the same year to dwarf planet, we still knew so little about Pluto. The theory was that the planet was probably just cold and dead, thanks to its vast distance from the Sun and small size, being just two-thirds the size of our moon. The images returned by the New Horizons spacecraft helped to cement Pluto’s place in the Solar System hall of fame. Already a bit of an oddball, Pluto orbits the Sun on a different plane from all the other planets, also differing from the other small icy objects – most of which are comets – in the Kuiper Belt.

…

At the time, findings from this ground-breaking mission were a complete surprise for scientists, who were left puzzled yet excited by the implications. For this frozen dwarf planet to host such a youthful surface requires that it must have some source of internal heat. The problem is, Pluto is very small – being just two-thirds the diameter of our Moon – and so would be expected to have lost any primordial heat long ago. In addition, Pluto is very far from the Sun, so it receives almost no solar heat. As a result, Pluto was expected to be dead and should have been this way for billions of years. But it’s not just Pluto that throws up questions, because it hosts five moons. One of them is Charon, which New Horizons revealed also shows a relatively smooth, fresh surface.

…

The Kuiper Belt is the origin of many of the short-period comets that enter the inner Solar System and transit close to the Sun every now and again, but it is also home to the dwarf planet Pluto. While Triton is a little larger than Pluto, it is of a similar composition, and the two may be related way back, billions of years ago, originating from the same Solar System neighbourhood. Triton and Pluto also have something else in common: Triton may have once had a friend with it, another object that joined it in what is known as a binary system, just like Pluto and its moon Charon. However, early in Solar System history, as Triton went about its orbit around the Sun, it may have got dangerously close to Neptune, such that it was pulled in by the giant planet’s gravity.

The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission

by

Jim Bell

Published 24 Feb 2015

But the next day when the images were beamed back: For some examples of the photos of Earth taken from the surface of Mars, see photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05547 and also pancam.sese.asu.edu/pancam_instrument/projects_3.html. Chapter 9. The Edge of Interstellar Space their “planet” status: For lots more background and detail on the controversy over the demotion of Pluto, see Neil deGrasse Tyson, The Pluto Files (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009); Mike Brown, How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2012); and the details about the IAU’s decision to demote Pluto to dwarf planet status, online at iau.org/public/themes/pluto. maybe 50,000 years ago or more: See astronomer and science evangelist Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy blog entry titled “The Long Climb from the Sun’s Core” at badastronomy.com/bitesize/solar_system/sun.html for information on how long it takes photons to escape the sun’s core.

…

But there are also significant differences. For example, though smaller than our own moon, Pluto has five moons of its own, including a relatively large one (half the size of Pluto itself) called Charon, which has a surface dominated by water ice instead of nitrogen. While Pluto itself may end up showing some similarities with its possible cousin Triton, my bet is that the Pluto system overall will turn out to be just as new, strange, and alien as every other place that we’ve encountered in our travels out into the solar system. Planets, dwarf planets, moons . . . it really doesn’t matter what we call them. They are a diverse, interesting, and just plain cool lot of neighbors that we share our solar system with.

…

Plus Titan, Triton, Enceladus, Dione, Rhea, Tethys, Ariel, Ceres, Vesta, Eris, our own moon, and lots more. And Pluto—for God’s sake, it’s got an atmosphere and five moons of its own. If that’s not a planet, I don’t know what is. By my reckoning (and I’m a bit of a weirdo among my astronomy friends for this), our solar system has about thirty-five known planets so far, and it’s likely that dozens more will be discovered over the coming decades. Let’s celebrate those numbers and the diversity of planetary characteristics within our cosmic neighborhood rather than splitting them up into categories implying substandard status, such as “moon” or “dwarf planet.” I’m a lumper rather than a splitter.

Catching Stardust: Comets, Asteroids and the Birth of the Solar System

by

Natalie Starkey

Published 8 Mar 2018

This is exactly what happened when the New Horizons mission to visit Pluto, the king of the Kuiper Belt, zoomed past after its launch from Earth in 2006. Jupiter gave the spacecraft a colossal boost of momentum that increased its speed by 14,000kph (9,000mph), dramatically cutting its total journey time to the outskirts of the Solar System and making New Horizons the first spacecraft to document a Kuiper Belt object. When the mission set off, Pluto was still classed as a planet; it was demoted to dwarf planet later in 2006, not that that made it any less important to study. New Horizons captured countless stunning images of Pluto’s icy terrains, surfaces that we can probably expect some its Kuiper Belt neighbours to mirror.

…

The Kuiper Belt was first observed in 1992, with its existence having been predicted in 1951 by the Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper. It was found to be made up of hundreds of millions of icy objects which inhabit a region 30 to 55AU from the Sun. The Kuiper Belt includes not only comets but some icy dwarf planets such as Pluto, highlighting the fact that it is made up of a range of different-sized objects. The Kuiper Belt comets are on fairly stable and generally elliptical orbits. However, they can be affected by the gravity of the planets, which can disrupt them from their stable orbit, deflecting them into the inner Solar System where they pass close to the inner rocky planets, or instead end their existence in a fiery solar collision.

…

Comets 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (hereafter 67P/C-G), visited by the Rosetta mission, and 81P/Wild2, visited by the Stardust mission, are Jupiter-family comets that are both just a couple of kilometres in diameter. However, there are some fairly large objects in the scattered disc, including Eris, which reaches 2,300km (1,429 miles) in diameter and whose large size and presence at this huge distance from the Sun in part caused the reclassification of Pluto as a dwarf planet. The farthest comet reservoir, the Oort Cloud, is composed of two regions, both of which lie in interstellar space beyond the heliosphere – that is, outside the solar magnetic field. One of these is the disc-shaped inner Oort Cloud, otherwise known as the Hills Cloud, and the other is an outer spherical cloud of comets.

Strange New Worlds: The Search for Alien Planets and Life Beyond Our Solar System

by

Ray Jayawardhana

Published 3 Feb 2011

The cause of all the frenzy was the implication from part (c) that Pluto, considered a planet for more than seventy-fve years, is no longer. In fact, the IAU made it explicit: Pluto is a dwarf planet by the above defnition and is recognized as the prototype of a new category of trans-Neptunian objects. The reactions to this apparent demotion ranged from the emotional to the humorous, from the somber to the silly. Schoolchildren wrote letters to prominent astronomers calling them heartless or worse. Cartoonists and late-night comedians poked fun at Pluto being sent to the cosmic doghouse. The self-styled “Friends of Pluto,” including the widow and son of its discoverer Clyde Tombaugh, protested in Las Cruces, New Mexico, carrying placards that read “Size Doesn’t Matter.”

…

Isotopes: Different types of atoms of the same chemical element, each harboring a different number of neutrons. Some isotopes are radioactive and thus decay into other types of atoms by spontaneously emitting particles and radiation. Kuiper Belt: The region beyond the orbit of Neptune (i.e., 30–55 AU from the Sun) that contains tens of thousands of small bodies, as well as a handful of known dwarf planets like Pluto, left over from the era of solar system formation. Light-year: The distance that light travels in a year, just under 10 trillion kilometers (or about 6 trillion miles). Magma: Molten rock. Main-sequence star: A star that fuses hydrogen into helium in its core. Stars spend the bulk of their lifetime in this phase, the length of which depends on the star’s mass.

…

Since then, astronomers have identifed over a thousand other such bodies, and it became increasingly clear that Pluto belongs to the same population. With the discovery of several large Kuiper Belt objects in recent years, some more than half the size of Pluto and harboring moons just like it does, Pluto’s special status was under threat. The issue came to a head in 2005, when Michael Brown at Caltech and his colleagues found a body, later (fttingly) named Eris after the Greek goddess of discord, estimated to be not only bigger than Pluto but also more massive. Now the scientifc community had little choice: they had to either elevate Eris (and others like it) to planet status or drop Pluto. If they chose the frst option, the ranks of solar system planets might swell into the dozens pretty quickly.

Letters From an Astrophysicist

by

Neil Degrasse Tyson

Published 7 Oct 2019

At the time this letter arrived in my office at the Hayden Planetarium I was busy fielding hundreds of such letters and did not reply. But had I done so, this is what I would have said: Dear Madeline, If anybody is living on Pluto, I assure you they still exist, even after Pluto’s demotion to Dwarf Planet status. So no need to fear for their lives. Also, if Pluto is anybody’s favorite planet, then it can simply become their favorite Dwarf Planet. No harm there. But in any case, you are right about the textbooks. They will all have to be changed. Bad for book buyers. But good for publishers—they get to sell you the book again. And here is my actual signature in cursive.

…

“There used to be a large apartment building outside my window but they tore it down. Now I can see the sky and it’s beautiful.” Neil deGrasse Tyson Manhattan Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds Wednesday, June 10, 2009 I’m Georgette Burrell and I’m seven years old. I saw your special on how Pluto is a dwarf planet. I thought that it was very cool. I heard of a planet (or star) called Lucy that is a big diamond. My question is how would scientists know about what it is if it’s so far away? Thanks, Georgette Excellent question, Georgette. Many dead stars are made of carbon (they are white dwarfs).

…

That’s why, if you look up the size of Earth’s atmosphere in multiple (independent) places, you will likely find very different answers, none of which are wrong. In another example, a question as simple as, “how many planets are there in the solar system?” does not have an unambiguous answer. Six moons, including our Moon, are bigger than Pluto. Not only that, several objects in the outer solar system are almost the same size of Pluto (within a factor of two). So what matters more than “how many?” is “what are their various properties?” and “what features do they have in common?” And how about the question of when Isaac Newton was born? This too, does not have an unambiguous answer.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

NASA, “Eris,” NASA Science, https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/dwarf-planets/eris/in-depth. 55. Paul Rincon, “Pluto Vote ‘Hijacked’ in Revolt,” BBC, August 25, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5283956.stm. 56. Robert Roy Britt, “Pluto Demoted: No Longer a Planet in Highly Controversial Definition,” Space.com, August 24, 2006, www.space.com/2791-pluto-demoted-longer-planet-highly-controversial-definition.html. 57. A. Pawlowski, “What’s a Planet? Debate over Pluto Rages On,” CNN, August 24, 2009, www.cnn.com/2009/TECH/space/08/24/pluto.dwarf.planet/index.html. 58. American Dialect Society, “‘Plutoed’ Voted 2006 Word of the Year,” January 5, 2007, www.americandialect.org/plutoed_voted_2006_word_of_the_year. 59.

…

American Dialect Society, “‘Plutoed’ Voted 2006 Word of the Year,” January 5, 2007, www.americandialect.org/plutoed_voted_2006_word_of_the_year. 59. “My Very Educated Readers, Please Write Us a New Planet Mnemonic,” New York Times, January 20, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/01/20/science/a-new-planet-mnemonic-pluto-dwarf-planets.html. 60. ABC7, “Pluto Is a Planet Again—At Least in Illinois,” ABC7 Eyewitness News, March 6, 2009, https://abc7chicago.com/archive/6695131. 61. Laurence A. Marschall and Stephen P. Maran, Pluto Confidential: An Insider Account of the Ongoing Battles Over the Status of Pluto (Dallas: Benbella Books, 2009), 4. 62. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, “Exploring the Planets,” https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/exploring-the-planets/online/discovery/greeks.cfm. 63.

…

Located far away from the Sun, the planet was named after the Roman god of the dark underworld: Pluto. But something was off. The calculations of the newly crowned planet’s size kept shrinking. In 1955, astronomers thought that Pluto had a mass similar to that of Earth. Thirteen years later, in 1968, new observations showed Pluto weighing in at roughly 20 percent of the Earth’s mass. Pluto continued to shrink until 1978, when calculations decidedly made Pluto a featherweight. Its mass was computed to be only 0.2 percent of the Earth’s mass. Pluto had been prematurely declared a planet, even though it was far smaller than the others in its league.

Interplanetary Robots

by

Rod Pyle

It is at the same time far less friendly and hospitable than we had hoped, but more fascinating than we could have imagined. It took over fifty years to reach the rest of the planets. Pluto (once a planet, now classified as a dwarf planet) was imaged by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2015, using a flyby trajectory hauntingly like Mariner 4's. That was the last of them—every planet from Mercury, nestled next to the sun, to Neptune and even (dwarf planet) Pluto had been imaged and investigated. We had done the easy part. Now it is time to go back to the most compelling places we've seen—the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, with their warm, subsurface oceans; the subterranean glaciers of Mars; the hydrocarbon oceans of Titan—and explore these places in detail.

…

Rather than being a hundreds of years old cyclonic storm like the Red Spot, however, the Great Dark Spot appears to have disappeared over the course of about twenty years—more recent Hubble Space Telescope images don't show it. To acquire the images of the furthest planet from the sun (Pluto was demoted to “dwarf planet” status in the twenty-first century), the flight controllers had to once again steer Voyager 2 as it passed Neptune to allow the cameras to track the planet as the spacecraft flew by to avoid image smear. It worked magnificently, with stunning images of the azure-blue world galvanizing the world press.

…

Only sixty years ago, the planets were places enshrouded in mystery, with most of our knowledge based on suppositions made from hazy telescopic observations. This has changed dramatically, with the pace accelerating in the past two decades as multiple international newcomers have joined exploratory efforts of the United States and Russia. We have now charted every planet we know of, including the former planet Pluto—now reduced to dwarf planet status with much acrimony (many people, astronomers among them, decried this change). We still have a long way to go—including that elusive first sample to be returned from another planet—but that achievement may not be far off. Besides the armada of government spacecraft that have reconnoitered every corner of the solar system, private entrepreneurs are getting into the game.

Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room

by

David Weinberger

Published 14 Jul 2011

The importance of this shift from the old private-then-public publishing model to a continuous now is visible in the confusion it causes in other spheres. Bradley points to a controversy over who discovered a dwarf planet called Haumea, as recounted in Alan Boyle’s book The Case for Pluto.43 It seems that the astronomer Michael Brown discovered a series of dwarf planets starting in December 2004 but kept them under wraps until July 20, 2005, when he posted a notice that he would announce the discoveries at a conference in September. On July 27, 2005, Jose Luis Ortiz Moreno filed a claim with the Minor Planet Center that his team had discovered one of those dwarf planets. Controversy ensued because Moreno had used some of Brown’s published data—his telescope logs—to find the contested dwarf planet.

…

Controversy ensued because Moreno had used some of Brown’s published data—his telescope logs—to find the contested dwarf planet. Brown says that he’d assumed people wouldn’t run with the data because generally it’s not official until you’ve checked and analyzed it sufficiently to let you submit it to a peer-reviewed journal. As Bradley writes in his post, this was a clash of conventions. The old model thinks of publishing as a point in time. Once a work has gone through that temporal portal and is published, credit and the accompanying authority are bestowed upon the author. But, in an open-science model in which the work is done in public and thus there is no one moment in which the work goes public, credit and authority become harder to bestow unambiguously.

…

See Science at Creative Commons Crick, Francis Crisis of knowledge CrisisCommons.org Crowds Crowdsourcing information amateur scientists British Parliamentarians’ use of expertise and leadership effectiveness Netflix contest open-notebook science Culture, information overload and Cybercascades Cyberchiefs: Autonomy and Authority in Online Tribes (O’Neil) Darnton, Robert DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) Darwin, Charles amateur scientists’ contributions barnacle studies Hunch.com and insight and leap of thought long-form thinking science and publishing Data accuracy of published data crowdsourcing scientific and medical information data commons evaluating metadata information and overaccumulation of scientific data scientific knowledge Data.gov Data-information-knowledge-wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy Davis, John Debian Decision-making advantages of networked corporate and government networked decision-making Debian community Dickover’s social solutions facing reality Wikipedia policy Defaults Democracy echo chambers hiding knowledge and increasing group polarization reason, truth, and knowledge Denney, Reuel Deolalikar, Vinay Derrida, Jacques Descartes, René Dialogue, exploring diversity through Dickens, Charles Dickover, Noel Diderot, Denis The Difference (Page) Discourses Diversity appropriate scoping decreasing intelligence echo chambers forking moderating negative effects of of expertise race and gender respectful conversations over DNA Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (film) Doctorow, Cory Dogger Bank Incident The Double Helix (Watson) Double-entry bookkeeping Dublin Core standard Dwarf planets eBird.org E-books Echo chambers Edge.org Ehrlich, Paul Einstein@Home Eliot, T.S. Embodied thought Emerson, Ralph Waldo Enders, John Engadget Environmental niche modeling Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Eureqa computer program Evolutionary science Experiments, scientific method and Expert Labs Expertise Challenger investigation crowdsourcing diversity in networking knowledge networks outperforming individuals professionalization of scaling knowledge and networking sub-networks Extremism: group polarization Exxon Valdez oil disaster Facebook Fact-based knowledge as foundation of knowledge British backlash against British chimney sweep reform Darwin’s work on barnacles Hunch.com international dispute settlement See also Data Fact-finding missions Facts Linked Data standard Malthusian theory of population growth networked Failed science Fear, information overload and Federal Advisory Committees (FACs) Federal Highway Administration Feminism Filters information overload as filter failure knowledge management FoldIt Food, extending shelf life of Foodies Ford Motors Forking Forscher, Bernard K.

The Mission: A True Story

by

David W. Brown

Published 26 Jan 2021

It was the kabuki dance that Ed had once described to Todd May. Ed slayed Gravity Probe B repeatedly and with mirth and quiet calm. But the probe did launch in 2004. Ed killed Alan Stern’s Pluto mission in September 2000, banned scientists from even studying the mission, vowed publicly that Pluto was “Dead! Dead! Dead!”—his actual words!—his actual exclamation marks!—because of Pluto’s price problems, and two months later, Pluto’s partisans having found a fiscally feasible way forward, why, Ed hopped on board, and New Horizons launched in 2006.356 Similarly, Ed killed the entire Mars program back in 1999, before presiding over five consecutive Mars mission successes, culminating with the Mars Phoenix landing in 2008, and there were possible sixth and seventh successes in the pipeline—Mars Science Laboratory and the orbiter MAVEN—both wrapping up development.357 Numbers eight, nine, and ten—the multidecadal Mars Sample Return campaign now embraced by the planetary science community—would follow thereafter.

…

The same could not be said for the fledgling New Frontiers, a new, middle mission class between Discovery and flagship, still finding its legs and with only a single project yet approved by 2004: a Pluto flyby called New Horizons being led by a scientist named Alan Stern. Todd had heard the Pluto mission was having problems, and to get a grip on the state of things, he took time to visit the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, which managed the mission’s science. While in town, he went to Ball Aerospace, which was building one of the Pluto spacecraft’s key science instruments. He went to Southwest Research’s San Antonio office, where the New Horizons payload was being managed.

…

To get more missions to space, he would bludgeon overbudget projects into submission: this is the funding you agreed to, launch on it, or don’t launch at all, but the coffers are hereby closed. He had succeeded with New Horizons, his Pluto mission, which launched a year earlier. Why couldn’t fiscal discipline work across the Science Mission Directorate?193 But Stern was an outsider when chosen for the job, and he knew it. Though he helped lift from Cape Canaveral one of NASA’s most prominent, promising missions, he had never actually worked for the agency. (He ran the Pluto mission from the Boulder branch of the Southwest Research Institute, a private science outfit.) So to help him navigate the alien agency bureaucracy, he recruited to be his deputy and compass Todd May, a longtime NASA manager at Marshall Space Flight Center.

QI: The Book of General Ignorance - The Noticeably Stouter Edition

by

Lloyd, John

and

Mitchinson, John

Published 7 Oct 2010

One of them, discovered in 2005 as 2003 UB313 and now named Eris, is actually larger than Pluto. Others, such as Sedna, Orcus, and Quaoar, aren’t far off. Now Pluto, Eris and Ceres – the largest body in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter – have been officially adopted as the first three dwarf planets. This change isn’t unprecedented. Ceres, like Pluto, was considered a planet from its discovery in 1801 until the 1850s when it was downgraded to an asteroid. The American Dialect Society voted ‘to pluto’, meaning ‘to demote or devalue someone or something’ their Word of the Year for 2006. ALAN [Pluto is] really, really big, and it goes around the sun!

…

Planets must fulfil three criteria: they have to orbit the sun, have enough mass to be spherical, and to have ‘cleared the neighbourhood’ around their orbit. Pluto only managed the first two, so was demoted to the status of ‘dwarf planet’. It’s not perfect – some astronomers argue that neither Earth, Jupiter or Neptune have cleared their orbits either – but it does resolve the anomalous position of Pluto. Even the planet’s discoverers in 1930 weren’t fully convinced of its status, referring to it as a trans-Neptunian object or TNO– something on the edge of the solar system, beyond Neptune. Pluto is much smaller than all the other planets, a fifth the mass of the Moon and smaller than seven of the moons of other planets.

…

The four innermost planets are medium-sized and rocky; the next four are gas giants. Pluto is a tiny ball of ice – one of at least 60,000 small, comet-like objects forming the Kuiper belt right on the edge of the solar system. All these planetoid objects (including asteroids, TNOs and a host of other subclassifications) are known collectively as minor planets. There are 371,670 of them already registered, around 5,000 new ones are discovered each month and it is estimated there may be almost 2 million such bodies with diameters of over a kilometre. Most are much too small to be considered as planets but twelve of them give Pluto a run for its money. One of them, discovered in 2005 as 2003 UB313 and now named Eris, is actually larger than Pluto.

Saturn's Children

by

Charles Stross

Published 30 Jun 2008

Silent Movie MERCURY, UNIQUELY AMONG the planets, is locked in a spin/orbit resonance with the sun; it revolves on its axis and has days and nights, but it takes three of its days to orbit the sun twice. At noon, things get a little hot on the surface—even hotter than down among the half-melted valleys of Venus. At midnight it’s as cold as Pluto or Eris. They build power plants here, vast beampower stations that fly in solar orbit, exporting infrared power to the shipyards of the dwarf planets of the Kuiper Belt, out beyond Neptune. To build and launch those power plants, they need heavy elements—mined locally. And guess what? Someone needs to run those mines. To avoid the extremes of temperature, the city of Cinnabar rolls steadily around the equator of Mercury on rails, chasing the fiery dawn.

…

But she told me not to, I think—and then everything goes dark. Long-Lost Sibs ERIS IS ONE of the largest dwarf planets in our home solar system, and also one of the chilliest and most isolated, for it spends most of its time well outside the Kuiper Belt, drifting in the darkness beyond the frosty edges of planetary space. It’s also spectacularly hard to get home from; its orbit is steeply inclined, almost forty-five degrees above the plane in which the rest of the planets and dwarf planets orbit. Unless you’re going to hitch a ride on one of the starships they build and launch every decade or so, this is the end of the line.

…

The inner system is rich in energy and heavy elements, with short travel time but middling-deep gravity wells. The moons of the outer-system gas giants are replete with light elements and shallower gravity wells, but their primaries are far apart. Finally, the Forbidden Cities scattered through the Kuiper Belt’s dwarf planets are loosely bound—and very far apart. Consequently, Mercury exports solar energy via microwave beam, hundreds and thousands of terawatts of the stuff, and uranium and processed metals via slow-moving cycler ship and magsail. Venus exports rare earth metals—albeit in smaller quantities, at greater cost—while Mars contributes iron, carbon dioxide, and other materials.

Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations

by

Clay Shirky

Published 28 Feb 2008

The English-language Wikipedia is the only noncommercial site in the top twenty Web sites for the United States. Wikipedia’s Content Mere volume would be useless if Wikipedia articles weren’t any good, however. By way of example, the article on Pluto as of May 2007 begins:Pluto, also designated 134340 Pluto, is the second-largest known dwarf planet in the Solar System and the tenth-largest body observed directly orbiting the Sun. Originally considered a planet, Pluto has since been recognized as the largest member of a distinct region called the Kuiper belt. Like other members of the belt, it is primarily composed of rock and ice and is relatively small; approximately a fifth the mass of the Earth’s Moon and a third its volume.

…

This works to Wikipedia’s benefit partly because bad changes can be rooted out faster, but also partly because human knowledge is provisional. During 2006 a debate broke out among astronomers on whether to consider Pluto a planet or to relegate it to another category; as the debate went on, Wikipedia’s Pluto page was updated to reflect the controversy, and once Pluto was demoted to the status of “dwarf planet,” the Pluto entry was updated to reflect that almost immediately. A Wikipedia article is a process, not a product, and as a result, it is never finished. For a Wikipedia article to improve, the good edits simply have to outweigh the bad ones.

…

It has an eccentric orbit that takes it from 29 to 49 AU from the Sun, and is highly inclined with respect to the planets. As a result, Pluto occasionally comes closer to the Sun than the planet Neptune. That paragraph includes ten links to other Wikipedia articles on the solar system, astronomical units (AU), and so on. The article goes on for five thousand words and ends with an extensive list of links to other sites with information about Pluto. This kind of thing—a quick overview, followed by broad and sometimes quite lengthy descriptions, ending with pointers to more information—is pretty much what you’d want in an encyclopedia. The Pluto article is not unusual; you can find articles of similarly high quality all over the site.

The Last Stargazers: The Enduring Story of Astronomy's Vanishing Explorers

by

Emily Levesque

Published 3 Aug 2020

The discovery turned out to be Eris, the largest Kuiper Belt object ever found at the time. Though its size was ultimately downgraded (it’s smaller than Pluto by about fifty kilometers), Eris’s discovery prompted an infamous vote by the International Astronomical Union to better define what astronomers considered a planet. The vote demoted Pluto to dwarf planet status, along with Eris and several others, a story detailed by Mike in his book, How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming. Robotic telescopes, of course, aren’t always perfect, and teaching a telescope to observe by itself comes with its own host of problems.

…

In 2014, astronomers discovered a little rocky object named 2014 MU69 in the Kuiper Belt, the wide ring of small rocky bodies orbiting our sun in the outer reaches of the solar system. The object itself wasn’t especially remarkable save for one key fact: we’d be able to pay it a visit in 2018. The New Horizons space probe had launched in 2006 and taken a nine-year trip to fly past Pluto and take the first close photographs of the dwarf planet’s surface. The flyby was a resounding success, and after zooming past Pluto, New Horizons was still flying. Anticipating this, astronomers had searched for a suitable object in the Kuiper Belt for New Horizons to aim for and came up with 2014 MU69. With a few course corrections, New Horizons would be able to fly past 2014 MU69 beginning in late 2018 and get a close-up view on January 1, 2019.

…

The Kuiper Belt (named for airborne astronomy pioneer Gerard Kuiper) is a wide ring of small solar system objects, made mainly of rock and ice, that begins just past the orbit of Neptune and stretches to a distance of 4.6 billion miles away from the sun. Today, Pluto and its moon, Charon, are considered members of the Kuiper Belt, but in 1992, with Pluto still designated as a planet, Dave and Jane were leading the search to discover the first object in this hypothesized fleet of small solar system objects. Their method employed the same technique as many other searches for moving or changing objects in the night sky, blinking between two images taken of the same region of sky to search for anything that had changed.

Life in the Universe: A Beginner's Guide

by

Lewis Dartnell

Published 1 Mar 2007

The central region, which will give birth to the Sun, is surrounded by a skirt of material, the accretion disc. The total mass of this disc is only about a hundreth that of the Sun but more than enough to make a family of planets, asteroids and comets. This accretion disc stretches ten times beyond the current orbit of the dwarf planet Pluto. Ninety-nine per cent of the disc is gas; the rest tiny particles of floating dust at a density of only a few per cubic metre. The swirling dust particles stick together, growing into larger and larger lumps. Once they become large enough to exert an appreciable gravitational tug, their growth rapidly accelerates, the rich getting richer as they pull in more and more material.

…

This would generate a truly fearsome wind, as planet-wide convection currents rebalance the temperature gradient, with hot air from the sun-side expanding and rushing around to the dark-side. However, it may be difficult for a planet orbiting so close to its star to retain a thick atmosphere. Mars is thought to have lost most of its original atmosphere, some blown away by the solar wind. Red dwarf planets may be especially susceptible and might need to be particularly large, to keep a firm gravitational grip on their atmosphere, and have a powerful magnetic field to deflect the solar wind. Furthermore, M-class dwarves have quite an agitated temper. They are much more active in solar flares and sunspots than the Sun and their brightness can rapidly vary by as much as ten per cent.

…

The crushing pressure at the bottom of such an ocean might preclude life around any hydrothermal vents and although photosynthetic bacteria might happily drift through the surface waters, it is unclear whether prebiotic chemistry could ever produce life under these circumstances. Earth’s climatic thermostat, the carbonate-silicate cycle, would also not function on a moon with no land surface. These moons would also become tidally locked to their planet and so rotate very slowly relative to the star, presenting similar problems to red dwarf planets. A thick atmosphere could redistribute the uneven heat but to hold on to this a moon would need to be at least three times bigger than Ganymede, the largest moon in our solar system. None of these may be critical problems and life on moons orbiting gas giants remains a fascinating possibility.

The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date

by

Samuel Arbesman

Published 31 Aug 2012

Just as shifting baseline syndrome makes us assume that whatever state of affairs we were born into is the normal one, we don’t often confront changing facts until another generation grows up with a different baseline. We are then forced to confront the difference between them. This is true of what’s currently happening with Pluto. If you ask young children in 2012 to name the planets, they go up to Neptune, and they finish by saying that Pluto is a dwarf planet, or distinguish Pluto in some other way. But this is likely a temporary condition. Those teaching want these kids to know about Pluto and its curious status. But soon enough, it will just fade away into a strange footnote, paralleling what happened back in the nineteenth century: Just as Ceres and the other large asteroids were once counted as planets (marked as such on charts and taught to schoolchildren for decades) until the discovery of the abundant minor planets of the asteroid belt, Pluto’s special place will likely fade away.

…

In it, they examined the estimated mass of Pluto’s size over time. We still don’t know Pluto’s mass, at least not exactly. Since it vents gases, astronomers often have trouble telling its size, sometimes viewing its self-generated haze as part of the surface. Since Pluto’s first sighting, when it was judged to be about the size of the Earth, estimates of its mass have dropped greatly over time. Dessler and Russell explained this by arguing something simple: Pluto itself is actually shrinking. By fitting the curve of Pluto’s diminishing size to a bizarre mathematical function using the irrational number π, they argued that Pluto would vanish in 1984.

…

By fitting the curve of Pluto’s diminishing size to a bizarre mathematical function using the irrational number π, they argued that Pluto would vanish in 1984. But don’t worry! According to their function, Pluto would reappear 272 years later (its mass would go from being mathematically imaginary to real again). Of course, this is ridiculous. A far more reasonable explanation is that our tools improved over time via the Moore’s-like laws that inexorably improve technology, allowing us to resolve Pluto better. While there’s still a certain amount of uncertainty in Pluto’s mass, we now have a much better handle on this fact: There is a clear relationship between what our facts are, increases in technology, and increases in measurement.

4th Rock From the Sun: The Story of Mars

by

Nicky Jenner

Published 5 Apr 2017

Phobos is so close to Mars that atmospheric drag could potentially have had this kind of effect, but Deimos exists much further away from Mars. To apply to both moons, Mars’s super-thick primitive atmosphere would thus need to have been far-reaching, too. A good example of the capture mechanism is Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, which is a captured dwarf planet from the distant outer Solar System (a body similar to Pluto). However, Triton does not behave as well as Phobos and Deimos do; it orbits Neptune in the ‘wrong’ direction (retrograde, opposite to Neptune’s rotation) and at a very high inclination. It likely disrupted the entire Neptunian system when it joined the family, throwing some of Neptune’s other moons into disarray and potentially flinging earlier moons out of the system completely.

…

Discovered in 1846, Neptune links to independence and utopia, likely influenced by the growth of different belief systems in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such as nationalism, socialism, communism and the welfare state. Technically speaking Pluto should be omitted from this section, but its story is interesting and slightly ironic – Pluto represents transformation, or digging beneath the surface to reveal the truth, regardless of how disruptive that truth may be. A self-fulfilling prophecy! Astrology may be the poster-child of occultism, but the same symbolism used in astrology also crops up in many other places – in witchcraft, tarot and palmistry, for example, three other well-known spiritual and occult practices.

…

Notes 1 This was possible due to a dynamical relationship known as an ‘orbital resonance’ – essentially, the two planets orbited the Sun in such a way that their orbital periods had a specific ratio, allowing them to influence one another gravitationally. Other bodies in the Solar System have such resonances today, notably Pluto and Neptune (2:3, meaning that Pluto completes two orbits for every three of Neptune’s), and Jupiter’s moons Ganymede, Europa and Io (a 1:2:4 resonance). 2 We believe this water to have been delivered by asteroids and comets during Mars’s earliest days (hence why theories that remove water-rich material from Mars’s vicinity are difficult to reconcile). 3 The largest craters on Mars are the Borealis (8,500km or 5,300 miles in diameter) and Utopia (3,300km or 2,050 miles in diameter) basins in the northern hemisphere, and the Hellas basin (2,300km or 1,420 miles in diameter) in the southern hemisphere. 4 Data from ESA’s Mars Express have indicated that escape to space might not have been the only culprit, as the stripping rates appear to be low and may not have been significantly different in the past.

Velocity Weapon

by

Megan E. O'Keefe

Published 10 Jun 2019

INTERLUDE: ALEXANDRA PRIME STANDARD YEAR ONE PLUTO’S ORBIT Alexandra Halston gripped the handle attached to the wall of the sleep pod and shoved, shooting herself “up” through the central body of the Reina Mora to the viewing room. Five years of travel, and the ship was bleeding the last of its velocity as it prepared to enter orbit around Pluto. When she’d been back on Earth drawing up plans, she’d wanted to orbit Pluto’s moon Charon to be closer to the gate. That argument had been intense, but eventually cooler heads—mostly Maria’s—had prevailed, and she’d acquiesced to getting as close as the Pluto orbit would let them.

…

They were near the battlefield of Dralee, and although there was a whole lot of space between the celestial bodies, Dralee was the closest in the system to Ada. That’s why she’d been patrolling it. “Bero, is your display damaged?” “No, Sanda.” She swallowed. Icarion couldn’t have… wouldn’t have. They wanted the dwarf planet. Needed access to Ada Prime’s Casimir Gate. “Bero. Where is Ada Prime in this simulation?” She pinched the screen, zooming out. The system’s star, Cronus, spun off in the distance, brilliant and yellow-white. Icarion had vanished, too. “Bero!” “Icarion initiated the Fibon Protocol after the Battle of Dralee.

…

The screen flickered in the corner of her eye and she glance over her shoulder. Icarion’s logo flared across it, bright and ashy. “Not. Better.” “Of course. My apologies.” The screen flickered again, this time filling with the dual system of Ada Prime. She licked bitter, gel-coated lips, staring at the little hunk of dwarf planet and orbital station she’d called home, with the Casimir Gate in orbit around it. Couldn’t be gone. Couldn’t be. “Bero!” “If there is another image that would be more suited to your current mood—” “It’s not the image. I request information relating to the Fibon Protocol. Immediately.” “You do not have to speak to me like I’m a computer.”

When More Is Not Better: Overcoming America's Obsession With Economic Efficiency

by

Roger L. Martin

Published 28 Sep 2020

If not, you are out of luck. There is zero reward for nuance, for “maybes,” for “it depends.” There are certainly some right answers—like how many planets there are in our solar system: nine, at least until Pluto was downgraded to a dwarf planet and lumped together with lots of other dwarf planets. And while we’re on the subject, was that downgrade legitimate or should Pluto still be a planet?2 As with the planethood of Pluto, the vast majority of answers aren’t certainly right. They are merely the best interpretation we have yet come up with, just as Newton’s law of universal gravitation was the best interpretation when he conceived of it.

…

Author’s calculations based on 2019 estimates from the United States Census Bureau, and on Tanza Loudenback, “State Income Tax Rates across America, Ranked from Highest to Lowest,” Business Insider, October 30, 2019. Chapter 8 1. Josie Fung, I-Think Executive Director, and Nogah Kornberg, I-Think Associate Director, interview via telephone with Beth Grosso, Hamilton, Ontario, January 8, 2020. 2. Sabrina Stierwalt, “Is Pluto a Planet?” Scientific American, July 31, 2019. 3. For more information, see https://www.rotmanithink.ca/. 4. National Center for Education Statistics, “Graduate Degree Fields,” updated April 2019. 5. Philip D. Arben, “The Integrating Course in the Business School Curriculum, or, Whatever Happened to Business Policy?”

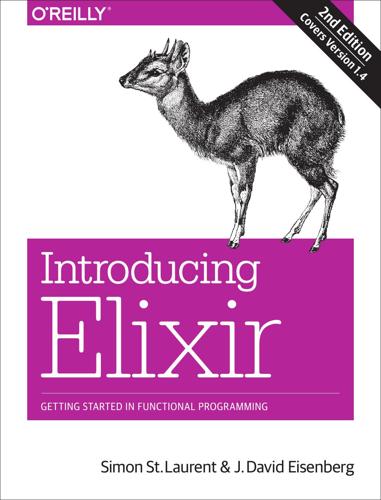

Introducing Elixir

by

Simon St.Laurent

and

J. David Eisenberg

Published 20 Dec 2016

You could create variables for arguments and then never use them, but you’ll get warnings from the compiler (which suspects you must have made a mistake), and Underscoring That You Don’t Care | 33 you may confuse other people using your code who are surprised to find your code cares about only half of the arguments they sent. You might, for example, decide that you’re not concerned with what planemo (for planetary mass object, including planets, dwarf planets, and moons) a user of your velocity function specifies, and you’re just going to use Earth’s value for gravity. Then you might write something like Example 3-5, found in ch03/ex3-underscore. Example 3-5. Declaring a variable and then ignoring it defmodule Drop do def fall_velocity(planemo, distance) when distance >= 0 do :math.sqrt(2 * 9.8 * distance) end end This will compile, but you’ll get a warning, and if you try to use it for, say, Mars, you’ll get the wrong answer: iex(1)> r(Drop) r(Drop) warning: redefining module Drop (current version loaded from _build/dev/lib/drop/ebin/Elixir.Drop.beam) lib/drop.ex:1 warning: variable planemo is unused lib/drop.ex:3 {:reloaded, Drop, [Drop]} iex(2)> Drop.fall_velocity(:mars,20) 19.79898987322333 On Mars, that should be more like 12 than 19, so the compiler was right to scold you.

…

Planemos for gravitational exploration Planemo Gravity (m/s2) Diameter (km) Distance from Sun (106 km) mercury 3.7 4878 57.9 venus 8.9 12104 108.2 earth 9.8 12756 149.6 moon 1.6 3475 149.6 mars 3.7 6787 227.9 ceres 0.27 950 413.7 jupiter 23.1 142796 778.3 saturn 9.0 120660 1427.0 uranus 8.7 51118 2871.0 neptune 11.0 30200 4497.1 pluto 0.6 2300 5913.0 haumea 0.44 1150 6484.0 makemake 0.5 1500 6850.0 eris 2400 10210.0 0.8 Although the name is Erlang Term Storage, you can still use ETS from Elixir. Just as you can use Erlang’s math module to calculate square roots by saying :math.sqrt(3), you can use ETS functions by preceding them with :ets.

…

Populating a simple ETS table and reporting on what’s there defmodule PlanemoStorage do require Planemo def setup do planemo_table = :ets.new(:planemos,[:named_table, {:keypos, Planemo.planemo(:name) + 1}]) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :mercury, gravity: 3.7, diameter: 4878, distance_from_sun: 57.9) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :venus, gravity: 8.9, diameter: 12104, distance_from_sun: 108.2) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :earth, gravity: 9.8, diameter: 12756, distance_from_sun: 149.6) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :moon, gravity: 1.6, diameter: 3475, distance_from_sun: 149.6) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :mars, gravity: 3.7, diameter: 6787, distance_from_sun: 227.9) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :ceres, gravity: 0.27, diameter: 950, distance_from_sun: 413.7) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :jupiter, gravity: 23.1, diameter: 142796, distance_from_sun: 778.3) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :saturn, gravity: 9.0, diameter: 120660, distance_from_sun: 1427.0) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :uranus, gravity: 8.7, diameter: 51118, distance_from_sun: 2871.0) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :neptune, gravity: 11.0, diameter: 30200, distance_from_sun: 4497.1) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :pluto, gravity: 0.6, diameter: 2300, distance_from_sun: 5913.0) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :haumea, gravity: 0.44, diameter: 1150, distance_from_sun: 6484.0) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :makemake, gravity: 0.5, diameter: 1500, distance_from_sun: 6850.0) :ets.insert :planemos, Planemo.planemo(name: :eris, gravity: 0.8, diameter: 2400, distance_from_sun: 10210.0) :ets.info planemo_table end end Again, the last call is to :ets.info/1, which now reports that the table has 14 items: iex(2)> r(PlanemoStorage) warning: redefining module PlanemoStorage (current version loaded from Elixir.PlanemoStorage.beam) lib/planemo_storage.ex:1 {:reloaded, PlanemoStorage, [PlanemoStorage]} iex(3)> :ets.delete(:planemos) true iex(4)> PlanemoStorage.setup [read_concurrency: false, write_concurrency: false, compressed: false, Storing Data in Erlang Term Storage | 155 memory: 495, owner: #PID<0.57.0>, heir: :none, name: :planemos, size: 14, node: :nonode@nohost, named_table: true, type: :set, keypos: 2, protection: :protected] If you want to see what’s in that table, you can do it from the shell by using the :ets.tab2list/1 function, which will return a list of records, broken into sepa‐ rate lines for ease of reading: iex(5)> :ets.tab2list :planemos [{:planemo, :neptune, 11.0, 30200, 4497.1}, {:planemo, :jupiter, 23.1, 142796, 778.3}, {:planemo, :haumea, 0.44, 1150, 6484.0}, {:planemo, :pluto, 0.6, 2300, 5913.0}, {:planemo, :mercury, 3.7, 4878, 57.9}, {:planemo, :earth, 9.8, 12756, 149.6}, {:planemo, :makemake, 0.5, 1500, 6850.0}, {:planemo, :moon, 1.6, 3475, 149.6}, {:planemo, :mars, 3.7, 6787, 227.9}, {:planemo, :saturn, 9.0, 120660, 1427.0}, {:planemo, :uranus, 8.7, 51118, 2871.0}, {:planemo, :ceres, 0.27, 950, 413.7}, {:planemo, :venus, 8.9, 12104, 108.2}, {:planemo, :eris, 0.8, 2400, 10210.0}] If you’d rather keep track of the table in a separate window, Erlang’s Observer table visualizer shows the same information in a slightly more readable form.

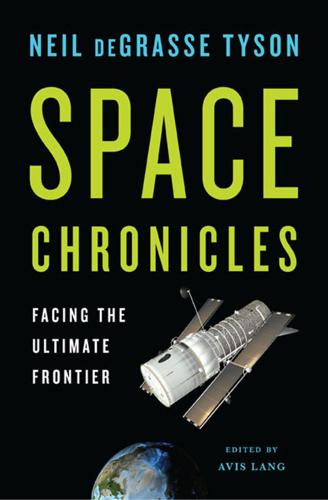

Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier

by

Neil Degrasse Tyson

and

Avis Lang

Published 27 Feb 2012

Of course, the greater your eccentricity, the more likely you are to cross somebody else’s orbit. Comets that plunge toward Earth from the outer solar system have highly eccentric orbits, whereas the orbits of Earth and Venus closely resemble circles, with very low eccentricities. The most eccentric “planet” (now officially a dwarf planet) is Pluto, and sure enough, every time it goes around the Sun, it crosses the orbit of Neptune, behaving suspiciously like a comet. Space Tweet #15 When asked why planets orbit in ellipses & not some other shape, Newton had to invent calculus to give an answer May 14, 2010 3:23 AM The most extreme example of an elongated orbit is the famous case of the hole dug all the way to China.

…

ALSO BY NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON The Pluto Files Death by Black Hole Origins To all those who have not forgotten how to dream about tomorrow CONTENTS Editor’s Note Prologue Space Politics PART I • WHY 1. The Allure of Space 2. Exoplanet Earth 3. Extraterrestrial Life 4. Evil Aliens 5. Killer Asteroids 6. Destined for the Stars 7. Why Explore 8. The Anatomy of Wonder 9. Happy Birthday, NASA 10. The Next Fifty Years in Space 11. Space Options 12. Paths to Discovery PART II • HOW 13. To Fly 14. Going Ballistic 15. Race to Space 16. 2001—Fact vs. Fiction 17. Launching the Right Stuff 18.

…

That’s where all your budget options come in above the funding threshold for heavy scrutiny, and you have no choice but to appeal to these great drivers in the history of culture. As far as basic research goes, we’ve got the Hubble telescope; we’re going to have a laboratory on Mars in a few years; we have the spacecraft Cassini in orbit around Saturn right now, observing the planet and its moons and its ring systems. We’ve got another spacecraft on its way to Pluto. We’ve got telescopes being designed and built that will observe more parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Science is getting done. I wish there was more of it, but it’s getting done. MP: But not the Large Hadron Collider, which is getting done by the Europeans. JG: There’s one other potential case for space travel that we haven’t really talked about.

Wireless

by

Charles Stross

Published 7 Jul 2009

Stubby delta wings slice through the air, propelled by a rocket-bright glare. VOICE-OVER: A modified Navajo missile—test article for an XK-PLUTO payload—dives away from a carrier plane. Unlike the real thing, this one carries no hydrogen bombs, no direct-cycle fission ramjet to bring retaliatory destruction to the enemy. Traveling at Mach 3, the XK-PLUTO will overfly enemy territory, dropping megaton-range bombs until, its payload exhausted, it seeks out and circles a final target. Once over the target it will eject its reactor core and rain molten plutonium on the heads of the enemy. XK-PLUTO is a total weapon: every aspect of its design, from the shock wave it creates as it hurtles along at treetop height to the structure of its atomic reactor, is designed to inflict damage.

…

“That is minimally correct, sir, although countervailing weapons have been developed to reduce the risk of a unilateral preemption escalating to an exchange of weakly godlike agencies.” The congressman in the middle nods encouragingly. “For the past three decades, the B-39 Peacemaker force has been tasked by SIOP with maintaining an XK-PLUTO capability directed at ablating the ability of the Russians to activate Project Koschei, the dormant alien entity they captured from the Nazis at the end of the last war. We have twelve PLUTO-class atomic-powered cruise missiles pointed at that thing, day and night, as many megatons as the entire Minuteman force. In principle, we will be able to blast it to pieces before it can be brought to full wakefulness and eat the minds of everyone within two hundred miles.”

…

As the sun brightens, so shall the verdant plains of the Earth; but the Stasis have long-laid plans to deflect the inevitable. Deep in the asteroid belt, their swarming robot cockroaches have dismantled Ceres, used its mass to build a myriad of solar-sail-powered flyers. Now a river of steerable rocks with the mass of a dwarf planet loops down through the inner system, converting solar energy into momentum and transferring it to the Earth through millions of repeated flybys. Already, Earth has migrated outward from the sun. Other adjustments are under way, subtle and far-reaching: the entire solar system is slowly changing shape, creaking and groaning, drifting toward a new and more useful configuration.

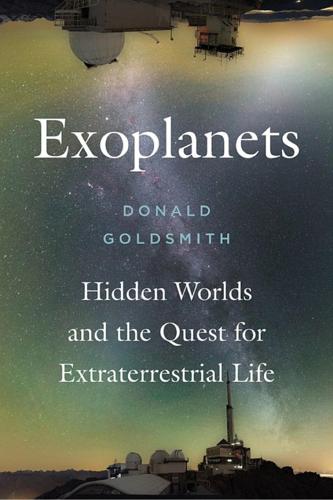

Exoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial Life

by

Donald Goldsmith

Published 9 Sep 2018

Albert Einstein, “Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper,” Annalen der Physik 17 (1905): 891–921. 5. Marina Brozovic et al., “Radar Observations and a Physical Model of Asteroid 4660 Nereus, a Prime Space Mission Target,” Icarus 201 (2009): 153–166. 6. “Enstatite mineral data,” available at http://www.webmineral.com/data/Enstatite.shtml#.WXo5saIrLBI. 7. See, generally, Thomas Hamilton, Dwarf Planets and Asteroids: Minor Bodies of the Solar System (Houston, TX: Strategic Book Publishing & Rights Agency, LLC, 2014). 8. Len Gillis, “Timmins Mine Likely to Close by 2022,” News Provincial article, November 17, 2016, available at http://www.thesudburystar.com/2016/11/17/timmins-mine-likely-to-close-by-2022. 9.

…

Because gravitational perturbations from the sun’s four giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) tend to produce random orbital characteristics, some astronomers have proposed that the orbital similarities observed in the sednoids must arise from the existence of a sizable planet with an orbit even larger than the extreme distances attained by the sednoids.7 In 2016, astronomer Michael Brown, who is best known as the man who slew Pluto as a planet (his Twitter handle is @PlutoKiller), made a more detailed analysis of these orbits in collaboration with his Caltech planetary-science colleague Konstantin Batygin.8 The astronomers concluded that half of the sednoids’ orbits might show only gravitational influences from Neptune, but six of them, including Sedna itself, display a remarkable similarity: They all orbit in nearly the same plane and make their closest approaches to the sun in the same direction.

…

Some of these exoplanets qualify as “young, hot Jupiters” that take only a few days to orbit around their stellar hosts. K2 has also studied star-forming regions, galaxies beyond the Milky Way, and numerous small objects within the solar system, including asteroids with Jupiter-like orbits and some of the trans-Neptunian objects whose size and numbers have, at least for now, downgraded Pluto from planetary status. If all goes well, K2 should at least double the number of Kepler planets. 6 DIRECTLY OBSERVING EXOPLANETS Astronomers have employed four fundamentally different approaches in their successful searches for exoplanets: radial-velocity measurements, transits, gravitational lensing, and direct observation.

The Search for Life on Mars

by

Elizabeth Howell

Published 14 Apr 2020

Chapter 10: Signatures 253 Caltech colleague: In his interview with Elizabeth Howell, Rich Rieber namechecked Professor Mike Brown, the California Institute of Technology astronomer who has found several dwarf planets about the size of Pluto in the outer solar system in the early 2000s. Brown was one of the leading advocates to remove Pluto from planetary status, a move that remains reviled by many, including Alan Stern, former NASA executive and the lead of a Pluto flyby mission called New Horizons. Brown cheerfully calls himself @plutokiller on Twitter. 257 chemical oven: Perseverance will avoid the problems with the perchlorates that have been discovered on the Martian surface.

…

This precious data would then take ten days to replay and build up into photographs at JPL. Improbably, it worked. In all, eleven useful frames were returned, some of which revealed a surprise: craters. That Mars would be peppered with craters is, in hindsight, no big deal: from innermost Mercury to Pluto at its outer extremities, all the solid bodies in our solar system show signs of cratering, a record of the violence of their birth. But in 1965, craters were a shock to geologists almost expecting a windswept desertscape and a general populace half-believing there might be canals. Taken altogether, the Mariner 4 data implied that Mars was dead in the geological sense and quite probably biologically, too.

…

He retired to spend more time in the balmier climes of the Mediterranean. He died in November 1916, thanks to “an attack of apoplexy,” in his biographer’s phrase; it was likely a stroke. “He lies buried in a mausoleum built by his widow close to the dome where his work was done.” Though the Lowell Observatory begat useful studies, notably the discovery of Pluto in 1930 and details of the expansion of the universe, its founder’s work completely polarized the scientific community. Planetary astronomy effectively died in the United States in subsequent years. In the words of one later researcher, “after Percival Lowell wrote all these crackpot books about Mars, planetary science had no reputation and nobody wanted to touch the field with a ten-foot pole.”

The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

by

Robert Zubrin

Published 30 Apr 2019

NEAR orbited Eros for more than a year, gradually lowering its orbit, and then actually landed on it in 2001, returning spectacular photographs in the process.3 This extraordinary achievement was then exceeded by the Japanese Hayabusa mission, which not only landed on the asteroid Itokawa but took off again to return dust samples to Earth in 2010.4 The European Rosetta spacecraft flew by asteroids Steins in 2008 and Lutetia in 2010 on its way to orbit the comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014.5 Another notable mission was the JPL Dawn spacecraft, a tour de force that, after orbiting the large asteroid Vesta from 2011 to 2012, used very-high-exhaust-velocity electric propulsion to depart and then go into orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres in 2015.6 The most recent asteroid missions are the Japanese Hayabusa2 and NASA's OSIRIS-REx, which launched in December 2014 and September 2016 to explore the carbonaceous asteroids Ryugu and Bennu, respectively. Hayabusa2 arrived at Ryugu in July 2018 and subsequently deployed the small European Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout (MASCOT) lander to collect samples.7 In December 2019, it will depart and hopefully return its samples to Earth in December 2020.

…

As telescopes grew and improved, other important finds followed, with the discovery of Saturn's rings and its moon Titan by Huygens in 1655; Jupiter's giant red spot by Cassini in 1665; the planet Uranus by Herschel in 1781; the planet Neptune by Adams and LeVerrier in 1846; Neptune's giant moon Triton by Lassell in 1846; Pluto by Tombaugh in 1930; Titan's atmosphere by Kuiper in 1944; and the giant iceteroid Chiron by Kowal in 1977. By the 1960s, Jupiter was known to have twelve satellites, Saturn nine, Uranus five, and Neptune two. Outer solar system exploration was revolutionized in the 1970s with the advent of robotic exploration spacecraft, starting with the Pioneer 10 mission to Jupiter, which flew by the giant planet in 1972.

…

Distances to the nearest known stars are tens of thousands of times greater than those to the furthest planets in our solar system. The Earth travels at a distance of 150 million kilometers, or one astronomical unit (AU), from the sun. Mars orbits at 1.52 AU, Jupiter at 5.2, Saturn at 9.5, Uranus at 19, Neptune at 30, and Pluto at 39.5. In contrast, the nearest known stellar system, Alpha Centauri (consisting of the sunlike type G star Alpha Centauri A and the dwarf stars Alpha Centauri B and Proxima Centauri) is 4.3 light-years, or 270,000 AU, distant. Our fastest spacecraft to date, Voyager, took thirteen years to reach Neptune.

The Moon: A History for the Future

by

Oliver Morton

Published 1 May 2019

Three of Jupiter’s moons—Ganymede, Io and Callisto—are more massive than the Moon. So is Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. But those moons represent only a tiny fraction of the mass of the mighty planets they orbit—about a five-thousandth—as opposed to the Moon’s eightieth of the Earth’s. The Moon is more than five times the mass of the dwarf planet Pluto and some 25 times the mass of all the asteroids in the asteroid belt put together. At least 95% of this mass is rock. A small amount of it forms a crust, which is about 40km thick, on average; the rest of it forms an underlying mantle. The Moon’s iron core, if it has one, is less than a twentieth of the mass of all that rock.

…

Most of the craters which contain this perpetual darkness are around the South Pole: the crater named after Gene Shoemaker is one. Being in the depths of the South Pole-Aitken basin gives the region a head start when it comes to avoiding sunlight. But there are pools of perpetual darkness in the north, too. And at both poles the darkness is phenomenally cold—colder, remarkably, than the surface of Pluto, which is 30 times farther from the Sun. Pluto may get sunlight a thousand times weaker than that which bathes the Moon, but every square metre of it gets some of that light some of the time. Go without sunlight at all for a few billion years and you can get really cold: the floors of the sunless craters are at about minus 238°C, 35 degrees above absolute zero.

Accelerando

by

Stross, Charles

Published 22 Jan 2005

Ten million kilometers out and Hyundai +4904/-56 looms beyond the parachute-shaped sail of the Field Circus like a rind of darkness bitten out of the edge of the universe. Heat from the gravitational contraction of its core keeps it warm, radiating at six hundred degrees absolute, but the paltry emission does nothing to break the eternal ice that grips Callidice, Iambe, Celeus, and Metaneira, the stillborn planets locked in orbit around the brown dwarf. Planets aren't the only structures that orbit the massive sphere of hydrogen. Close in, skimming the cloud tops by only twenty thousand kilometers, Boris's phased-array eye has blinked at something metallic and hot. Whatever it is, it orbits out of the ecliptic plane traced by the icy moons, and in the wrong direction.

…

As long as the original Amber and her incarnate team can keep it running, the Field Circus can continue its mission of discovery, but they're part of the posthuman civilization evolving down in the turbulent depths of Sol system, part of the runaway train being dragged behind the out-of-control engine of history. Weird new biologies based on complex adaptive matter take shape in the sterile oceans of Titan. In the frigid depths beyond Pluto, supercooled boson gases condense into impossible dreaming structures, packaged for shipping inward to the fast-thinking core. There are still humans dwelling down in the hot depths, but it's getting hard to recognize them. The lot of humanity before the twenty-first century was nasty, brutish, and short.

…

At the far end of a wormhole, two hundred light-years distant in real space, coherent photons begin to dance a story of human identity before the sensoria of those who watch. And all is at peace in orbit around Hyundai +4904/-56, for a while … Chapter 3 Nightfall A synthetic gemstone the size of a Coke can falls through silent darkness. The night is quiet as the grave, colder than midwinter on Pluto. Gossamer sails as fine as soap bubbles droop, the gust of sapphire laser light that inflated them long since darkened. Ancient starlight picks out the outline of a huge planetlike body beneath the jewel-and-cobweb corpse of the starwisp. Eight Earth years have passed since the good ship Field Circus slipped into close orbit around the frigid brown dwarf Hyundai +4904/-56.

Geography of Bliss

by

Eric Weiner

Published 1 Jan 2008

He says this like it’s an obvious fact, as in, “Oh, it’s Sunday, so of course the shops are closed today.” Not see the sun? I don’t like the way this sounds. In the past, the sun has always been there for me, the one celestial body I could count on. Unlike Pluto, which for decades led me to believe it was an actual planet when the whole time it was really only a dwarf planet. I had plenty of time to ponder celestial bodies on the long flight from Miami. Flying from Florida to Iceland in the dead of winter is at best counterintuitive and at worst sheer lunacy. My body sensed this before the rest of me. It knew something was wrong, that some violation of nature was taking place, and expressed its displeasure by twitching and flatulating more than usual.

…

Some people, those on an especially tight budget, will park a bottle of booze on the sidewalk near the bar and then step outside for a nip every few minutes. It is this kind of resourcefulness, I think, that explains how this hardy band of Vikings managed to survive more than one thousand years on an island that is about as hospitable to human habitation as the planet Pluto—if Pluto were a planet, that is, which it’s not. The music is loud. Eva and Harpa are sloshed. I am jet-lagged. These three facts conspire against coherent conversation. “I’m a writer,” I tell Eva, trying to break through the fog. She looks confused. “A rider? What do you ride, horses?” “No, a WRITER,” I shout.

Day We Found the Universe

by

Marcia Bartusiak

Published 6 Apr 2009

The observatory's new director, Vesto M. Slipher, continued to administer the search. In 1930 a newly hired staff member, twenty-four-year-old Clyde Tombaugh, at last made the discovery. The new planet was named Pluto. The first two letters—PL —honored the man who initiated the planetary hunt. In 2006 Pluto, always considered an oddball because of its small size and eccentric orbit, was demoted to dwarf planet (a type of solar system body now called a plutoid), no longer one of the pantheon of classical planets. Though detecting the swift speeds of the spiral nebulae was his most heralded accomplishment, Slipher made other notable discoveries during his long career.

…

Saturn's immense gravitational pull, avowed Maxwell, would have torn apart any sort of solid disk. If true, then Newton's law of gravity would predict that the myriads of tiny chunks located in the outer part of the ring would be traveling slower than those closer in, nearer to Saturn's gravitational grip—just as Pluto, far from the Sun, orbits at a slower velocity than the solar system's inner planets. A spectrum, taken on the night of April 9, 1895, gave Keeler the direct proof. The spectral lines indicated that the ring's particles were circulating around Saturn according to the rules of Sir Isaac. The ring was not a rigid plate after all.

Calling Bullshit: The Art of Scepticism in a Data-Driven World

by

Jevin D. West

and

Carl T. Bergstrom

Published 3 Aug 2020

Not that this process is always trivial—one can miscount, mismeasure, or make mistakes about what one is counting. Take the number of planets in the solar system. From the time that Neptune was recognized as a planet in 1846 through to 1930 when Pluto was discovered, we believed there were eight planets in our solar system. Once Pluto was found, we said there were nine planets—until the unfortunate orb was demoted to a “dwarf planet” in 2006 and the tally within our solar system returned to eight. More often, however, exact counts or exhaustive measurements are impossible. We cannot individually count every star in the measurable universe to arrive at the current estimate of about a trillion trillion.

The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy

by

Moiya McTier

Published 14 Aug 2022

Most of the galaxies who are still around are dwarf galaxies, which I suppose I must describe because there’s some potential for confusion about the threshold between a dwarf galaxy and a big galaxy like me. Several years ago, there was a large controversy when one of your beloved planets in your solar system was demoted to a dwarf planet. Astronomers claimed it was because the icy chunk of rock wasn’t massive enough to have cleared out the debris in its orbital path. I have no quarrel with that; what you call a planet is up to you. What do I care? I have hundreds of billions of planets. I wonder, though: Would you have the same kind of outraged reaction if I were demoted to a dwarf galaxy?

…

Amanda McLoughlin and Julia Schifini, “Norse Cosmology,” August 12, 2020, in Spirits, produced by Julia Schifini, podcast, 49:10, https://spiritspodcast.com/episodes/norse-cosmology. 2A few of the planets may line up once every few decades, but it would be nearly impossible for all eight (or nine if you count Pluto) of the planets to form a solar system–wide syzygy. The last time all of the planets were even in the same vague region of the sky was over a thousand years ago. But even if the planets did align, their combined gravitational pull would barely be noticeable to us, and it certainly wouldn’t be enough to bring about the end of the world!

Engineering Infinity

by

Jonathan Strahan

Published 28 Dec 2010