Richard Feynman: Challenger O-ring

description: Physicist Richard Feynman was part of the Rogers Commission that investigated the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, famously demonstrating the O-ring material's vulnerability to cold.

33 results

Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

by

James Gleick

Published 1 Jan 1992

The Eightfold Way. New York: Benjamin. Gemant, Andrew. 1961. The Nature of the Genius. Springfield, Ill.: Charles C. Thomas. Gerard, Alexander. 1774. An Essay on Genius. London: Strahan. Gieryn, Thomas F., and Figert, Anne E. 1990. “Ingredients for a Theory of Science in Society: O-Rings, Ice Water, C-Clamp, Richard Feynman and the New York Times.” In Theories of Science and Society. Edited by Susan E. Cozzens and Thomas F. Gieryn. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. Gilbert, G. Nigel, and Mulkay, Michael. 1984. Opening Pandora’s Box: A Sociological Analysis of Scientists’ Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

…

F-W, 800–801. 378 THE WESTERN UNION “TELEFAX": Erik Rundberg to Feynman, 21 October 1965, PERS. 378 THE FIRST CALL HAD COME: F-W, 801; “Dr. Richard Feynman Nobel Laureate!” California Tech, 22 October 1965, 1. 378 WILL YOU PLEASE TELL US: F-W, 804. 378 WHAT APPLICATIONS DOES THIS PAPER: “Dr. Richard Feynman Nobel Laureate!” 378 LISTEN, BUDDY, IF I COULD TELL YOU: F-W, 804. 378 JULIAN SCHWINGER CALLED: Schwinger, interview. 378 I THOUGHT YOU WOULD BE HAPPY: Feynman to Lucille Feynman, n.d., PERS. 379 [FEYNMAN:] CONGRATULATIONS: “Dr. Richard Feynman Nobel Laureate!” 379 THERE WERE CABLES FROM SHIPBOARD: F-W, 806. 379 HE PRACTICED JUMPING BACKWARD: Ibid., 808–9. 380 FEYNMAN REALIZED THAT HE HAD NEVER READ: Ibid., 812. 380 HE BELIEVED THAT HISTORIANS: Feynman 1965a. 380 WE HAVE A HABIT IN WRITING: Ibid. 380 AS I WAS STUPID: Ibid. 381 THE CHANCE IS HIGH: Feynman 1965c. 381 I DISCOVERED A GREAT DIFFICULTY: Ibid. 382 THE ODDS THAT YOUR THEORY: Feynman 1965a. 382 DR.

…

Genius The Life and Science of Richard Feynman James Gleick For my mother and father, Beth and Donen I was born not knowing and have only had a little time to change that here and there. —Richard Feynman CONTENTS PROLOGUE FAR ROCKAWAY •Neither Country nor City •A Birth and a Death •It’s Worth It •At School •All Things Are Made of Atoms •A Century of Progress •Richard and Julian MIT • The Best Path • Socializing the Engineer • The Newest Physics • Shop Men • Feynman of Course Is Jewish • Forces in Molecules • Is He Good Enough? PRINCETON • A Quaint Ceremonious Village • Folds and Rhythms • Forward or Backward?

The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman

by

Richard P. Feynman

and

Jeffrey Robbins

Published 1 Jan 1999

A commission was formed, led by Secretary of State William P. Rogers and composed of politicians, astronauts, military men, and one scientist, to investigate the cause of the accident and to recommend steps to prevent such a disaster from ever happening again. The fact that Richard Feynman was that one scientist may have made the difference between answering the question of why the Challenger failed and eternal mystery. Feynman was gutsier than most men, not afraid to jet all over the country to talk to the men on the ground, the engineers who had recognized the fact that propaganda was taking the lead over care and safety in the shuttle program.

…

And I wonder what the hell it must look like to the students. 12 RICHARD FEYNMAN BUILDS A UNIVERSE In a previously unpublished interview made under the auspices of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Feynman reminisces about his life in science: his terrifying first lecture to a Nobel laureate-packed room; the invitation to work on the first atomic bomb and his reaction; cargo-cult science; and that fateful predawn wake-up call from a journalist informing him that he’d just won the Nobel prize. Feynman’s answer: “You could have told me that in the morning.” NARRATOR: Mel Feynman was a salesman for a uniform company in New York City. On May 11, 1918, he welcomed the birth of his son Richard. Forty-seven years later, Richard Feynman received the Nobel Prize for Physics. In many ways, Mel Feynman had a lot to do with that accomplishment, as Richard Feynman relates. FEYNMAN: Well, before I was born, he [my father] said to my mother that “this boy is going to be a scientist.” You can’t say things like that in front of women’s lib these days, but that is what they said in those days.

…

See Federal Aviation Administration Faith healing, 106, 107, 110 Faraday, Michael, 194 Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), 161, 162, 164 Female mind, 175–176 Fermi, Enrico, 85–86, 190, 190(n), 203 Feynman diagrams, xi, 191, 198 Feynman integrals, 191 Feynman Lectures on Physics, The 191 Feynman, Richard awards for, 233. See also Feynman, Richard, and Nobel Prize and Challenger O-rings, 152. See also Space Shuttle Challenger, O-ring seals and his children, 21–22, 172, 195, 204 death of, 1 and father, 3, 4–5, 7–8, 65, 174, 180, 181–182, 183–184, 225–226 first formal lecture of, 229–230 and Freeman Dyson, x-xias irresponsible, 19–20, 86 and nanotechnology, 117, 138–139. See also Computers, size of; Machines as tiny and Nobel Prize, xviii, 11, 11(n), 12, 189, 196, 225, 227, 233–234, 235, 237 Ph.D. degree of, 55 prizes offered by, 138–139 as student, 2, 5–6, 13, 109, 172, 175, 176–177, 196, 197, 218, 228 wives of, 58, 62, 65, 66, 67, 68, 233–234 Finnegans’s Wake (Joyce), 238 Fission, 16.

Six Not-So-Easy Pieces: Einstein’s Relativity, Symmetry, and Space-Time

by

Richard P. Feynman

,

Robert B. Leighton

and

Matthew Sands

Published 22 Mar 2011

He also authored a number of advanced publications that have become classic references and textbooks for researchers and students. Richard Feynman was a constructive public man. His work on the Challenger commission is well-known, especially his famous demonstration of the susceptibility of the O-rings to cold, an elegant experiment which required nothing more than a glass of ice water. Less well-known were Dr. Feynman’s efforts on the California State Curriculum Committee in the 1960s where he protested the mediocrity of textbooks. A recital of Richard Feynman’s myriad scientific and educational accomplishments cannot adequately capture the essence of the man.

…

Even late in his life, when taking part in the investigations of the Challenger disaster, he took great pains to show, on national television, that the source of the disaster was something that could be appreciated at an ordinary level, and he performed a simple but convincing experiment on camera showing the brittleness of the shuttle’s O-rings in cold conditions. He was a showman, certainly, sometimes even a clown; but his overriding purpose was always serious. And what more serious purpose can there be than the understanding of the nature of our universe at its deepest levels? At conveying this understanding, Richard Feynman was supreme. ROGER PENROSE December 1996 SPECIAL PREFACE (from The Feynman Lectures on Physics) Toward the end of his life, Richard Feynman’s fame had transcended the confines of the scientific community.

…

At conveying this understanding, Richard Feynman was supreme. ROGER PENROSE December 1996 SPECIAL PREFACE (from The Feynman Lectures on Physics) Toward the end of his life, Richard Feynman’s fame had transcended the confines of the scientific community. His exploits as a member of the commission investigating the space shuttle Challenger disaster gave him widespread exposure; similarly, a best-selling book about his picaresque adventures made him a folk hero almost of the proportions of Albert Einstein. But back in 1961, even before his Nobel Prize increased his visibility to the general public, Feynman was more than merely famous among members of the scientific community—he was legendary.

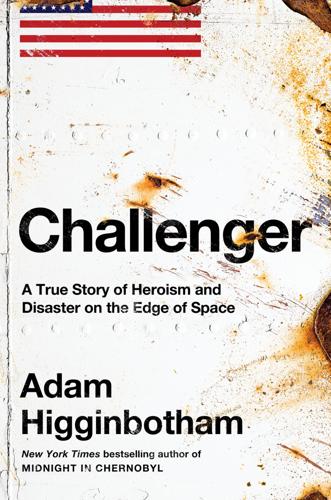

Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space

by

Adam Higginbotham

Published 14 May 2024

Meanwhile, the dozen: RCR, vol. I, 207–8; Feynman, “What Do You Care What Other People Think?,” 199. While continuing his work: Gleick, Genius, 426. he scribbled notes on: “Richard Feynman 4pp. Handwritten Document From the Challenger Investigation—Feynman’s Detailed Notes for 4 Days Spanning 7–10 February 1986, Leading Up to & Including Discovery of O-Ring Failure,” Nate D. Sanders Auctions, http://natedsanders.com/richard_feynman_4pp__handwritten_document_from_the-lot61780.aspx. To the growing irritation: Keel, author interview, October 21, 2020. He chose: Feynman, “What Do You Care What Other People Think?

…

Getty Images/Bettmann Larry Mulloy, NASA’s manager of the solid rocket booster project at the Marshall Space Flight Center, points to the O-ring in a full-size cross-section of the rocket joint during his testimony before the Rogers Commission on February 13, 1986. AP Images/Scott Stewart Caltech professor Richard Feynman alienated some of his colleagues on the commission with what they saw as his publicity-seeking antics; but his ice-water “experiment” helped crystallize the role of the O-rings in the accident with the media. AP Images/Dennis Cook In January 1987, NASA workers began lowering the recovered wreckage of Challenger into a pair of disused underground missile silos at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, which were then locked and sealed with concrete caps.

…

“Do what you think is right,” he told Feynman: Keel, author interview, October 21, 2020; RCR, vol. IV, 363; “Richard Feynman Debunks NASA,” YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=raMmRKGkGD4. Two days after: Time of flight given as 6:15 on February 13: Richard P. Feynman to Gweneth and Michelle Feynman, February 12, 1986, in Feynman and Feynman, Perfectly Reasonable Deviations from the Beaten Track, 401. By now, the causes of the accident: McDonald with Hansen, Truth, Lies, and O-Rings, 174; David Sanger, “NASA Photos Hint Trouble Started Right at Liftoff,” NYT, February 14, 1986; Boisjoly, Challenger Book Material, 431–2. Following his unexpected: McDonald with Hansen, Truth, Lies, and O-Rings, 175–79.

The Greatest Story Ever Told--So Far

by

Lawrence M. Krauss

Published 21 Mar 2017

At a talk at Caltech on the subject, Richard Feynman, characteristically, homed in on a key outstanding experimental question and asked whether the SLAC experimentalists had checked that the detector responded equally well to both left-handed and right-handed electrons. They hadn’t, but for theoretical reasons they had had no reason to expect the detectors to behave differently for the different polarizations. (Feynman would famously get to the heart of another complex problem eight years later after the tragic Challenger explosion, when he simply demonstrated the failure of an O-ring seal to the investigating commission and to the public watching the televised proceedings.)

…

While they may be strange, the connections unearthed by Einstein and Minkowski can be intuitively understood—given the constancy of the speed of light—as I have tried to demonstrate. Far less intuitive was the next discovery, which was that on very small scales, nature behaves in a way that human intuition cannot ever fully embrace, because we cannot directly experience the behavior itself. As Richard Feynman once argued, no one understands quantum mechanics—if by understand one means developing a concrete physical picture that appears fully intuitive. Even many years after the rules of quantum mechanics were discovered, the discipline would keep yielding surprises. For example, in 1952 the astrophysicist Hanbury Brown built an apparatus to measure the angular size of large radio sources in the sky.

…

It was not the proper description when relativistic effects needed to be taken into account. Ultimately Dirac succeeded where all others had failed, and the equation he discovered, one of the most important in modern particle physics, is, not surprisingly, called the Dirac equation. (Some years later, when Dirac first met the physicist Richard Feynman, whom we shall come to shortly, Dirac said after another awkward silence, “I have an equation. Do you?”) Dirac’s equation was beautiful, and as the first relativistic treatment of the electron, it allowed correct and precise predictions for the energy levels of all electrons in atoms, the frequencies of light they emit, and thus the nature of all atomic spectra.

Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster

by

Allan J McDonald

and

James R. Hansen

Published 25 Apr 2009

During the first public hearing conducted on February 11, 1986, Rogers Commission member Dr. Richard Feynman removed a piece of O-ring that he had squeezed in a C-clamp from a glass of ice water, thereby demonstrating to NASA's Larry Mulloy the loss of resiliency of a cold O-ring. (Photograph by Marilyn K. Yee/New York Times/Redux Pictures, reprinted with permission.) On February 25, 1986, I was sworn in as the first witness at the Presidential Commission's inaugural public televised hearing on the decision to launch Challenger. (Photograph © 1986, Los Angeles Times, reprinted with permission.) PART IV Obfuscation Oh, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!

…

The critical items list did not address O-ring resiliency even though it was an even more important issue relative to the ability of the O-rings to seal at the cold temperatures forecast for this launch—and this issue should also have been addressed in the waiver. Physicist Richard Feynman was very interested in the dynamics of the field-joint, particularly the pressure actuation and extrusion of the O-rings into the gap created by the motor pressure. I explained to Dr. Feynman how this occurred and why it was so important to understand the timing function in the early phases of ignition for assessing the ability of the O-rings to seal properly. “You suggested, Mr. McDonald, that the secondary seal would not be much affected by the temperature,” Feynman stated, “but now you are telling us that because of the complete or nearly complete loss of resilience—that is, the tendency to spring back—the secondary seal would require very little rotation to open.

…

Neither Wear nor Mulloy had ever intended not to accept my recommendation to drop these off the PAS report and report progress by the O-ring task force at each FRR. I never received a negative response from them verbally or in writing to that effect. If the Challenger accident hadn't happened, closing out this item would surely have been accepted because they were getting pushed by their management to reduce the size of the PAS report. “Nobody answered this letter of Mr. McDonald's?” Richard Feynman asked. “No,” Wear admitted, without saying that he had had a month and a half to respond. “That's exactly the point,” heralded Sally Ride, “because you got the system that records open problems, and you have to have some way of distinguishing ‘unimportant problems’ from ‘important problems’ from ‘very important problems,’ and it seems to me the one that says ‘launch constraint’ next to it must be the ‘very most important problem.’”

The Meaning of It All

by

Richard P. Feynman

Published 8 Jul 2012

He also authored a number of advanced publications that have become classic references and textbooks for researchers and students. Richard Feynman was a constructive public man. His work on the Challenger commission is well known, especially his famous demonstration of the susceptibility of the O-rings to cold, an elegant experiment, which required nothing more than a glass of ice water. Less well known were Dr. Feynman’s efforts on the California State Curriculum Committee in the 1960s where he protested the mediocrity of textbooks. A recital of Richard Feynman's myriad scientific and educational accomplishments cannot adequately capture the essence of the man.

…

For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02412, or call (800) 255–1514 or (617) 252–5298, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com. 05 06 07 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Publisher’s Note The Uncertainty of Science The Uncertainty of Values This Unscientific Age Index About Richard Feynman PUBLISHER’S NOTE In April 1963, Richard P. Feynman was invited to give a three-night series of lectures at the University of Washington (Seattle) as part of the John Danz Lecture Series. Here is Feynman the man revealing, as only he could, his musings on society, on the conflict between science and religion, on peace and war, on our universal fascination with flying saucers, on faith healing and telepathy, on people’s distrust of politicians—indeed on all the concerns of the modern citizen-scientist.

…

Research Associates, 102, 105 Statistical sampling, 84, 89–91 Stupidity, phenomena result of a general, 95 Systems, traffic, 118 Technology applications of, 62 and science, 50 Telekinesis, 68 Telepathy, mental, 71–74 Television advertising in, 85 looker, intelligence of average, 87–88 Testing, nuclear, 106–7 Theories, allowing for alternative, 69 Thoroughness, concept of, 17 Tops, spinning, 24–26 Traffic systems, 118 Troubles and lack of information, 91 Truth of ideas, 21 writing, 56 Uncertainties admission of, 34 dealing with, 66–67, 71 relative certainties out of, 98 remaining, 70–71 of science, 1–28 scientists dealing with, 26–27 of values, 29–57 Uncertainty, 67–68 Universe contemplation of, 39 origins of, 12 Unscientific age, 59–122 Values ethical, 43 moral, 120–21 uncertainty of, 29–57 Venus flying saucers from, 75 Mariner II voyage to, 109–12 Vocabulary, 116 War, dislike of, 32 Water, and deserts, 96 Weight, as not affected by motion, 24 Western civilization, 47 Witch doctors, 114 Words, as meaningless, 20 Writing truth, 56 ABOUT RICHARD FEYNMAN Born in 1918 in Brooklyn, Richard P. Feynman received his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1942. Despite his youth, he played an important part in the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos during World War II. Subsequently, he taught at Cornell and at the California Institute of Technology. In 1965 he received the Nobel Prize in Physics, along with Sin–Itero Tomanaga and Julian Schwinger, for his work in quantum electrodynamics.

Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout

by

Cal Newport

Published 5 Mar 2024

Feynman Is a Nobel Laureate, a Member of the Shuttle Commission, and Arguably the World’s Best Theoretical Physicist,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1986, latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-04-20-tm-1265-story.html. For a good, concise history of Feynman and the commission, including the detail of his former student roping him into participation, I recommend this article: Kevin Cook, “How Legendary Physicist Richard Feynman Helped Crack the Case on the Challenger Disaster,” Literary Hub, June 9, 2021, lithub.com/how-legendary-physicist-richard-feynman-helped-crack-the-case-on-the-challenger-disaster. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “This industry, visible”: Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, ed. John Bigelow (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1868; Project Gutenberg, 2006), chap. 6, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20203.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “To do real good physics”: Here is an article from 2014 I wrote about the clip, including the identification of the excerpt cited here (the YouTube clip of the 1981 video has been taken down for copyright violation reasons): Cal Newport, “Richard Feynman Didn’t Win a Nobel by Responding Promptly to E-mails,” Cal Newport (blog), April 20, 2014, calnewport.com/blog/2014/04/20/richard-feynman-didnt-win-a-nobel-by-responding-promptly-to-e-mails. The second half of this quote can also be found in Feynman’s Los Angeles Times obituary: Lee Dye, “Nobel Physicist R. P. Feynman of Caltech Dies,” Los Angeles Times, February 16, 1988, latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-02-16-mn-42968-story.html.

…

I neglected to mention in Deep Work, for example, that a half decade after his Horizon interview, Feynman’s protective shield of irresponsibility was pierced when his former student, William Graham, then the acting director of NASA, called Feynman and persuaded him to join the presidential commission on the space shuttle Challenger disaster. Feynman ultimately helped identify the cause of the Challenger explosion: the shuttle’s rubber O-ring seals lost their elasticity when cooled below a certain temperature. Feynman’s famous demonstration of this problem during the commission’s televised hearings, in which he plunged an O-ring into a glass of ice water, became iconic, and attracted the aging physicist a new round of late-in-life celebrity. For all the success of his participation in this commission, however, it’s undeniable that it represents a failure of Feynman’s best-laid plans to avoid extraneous projects in his professional life.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

The commission determined that the explosion resulted from a failure of the O-rings. At a commission hearing, Richard Feynman stunned television audiences by dropping an O-ring into ice water. The O-ring visibly lost its ability to seal in temperatures similar to those prevailing at the time of Challenger’s launch. The recurring problems with the O-rings had been described in NASA documents as an “acceptable risk,” the standard way of doing business. As one flight after another was completed despite dangerous levels of O-ring damage, NASA began to develop institutional tunnel vision. “Since the risk of O-ring erosion was accepted and indeed expected,” explained NASA manager Lawrence Mulloy, “it was no longer considered an anomaly to be resolved before the next flight.”2 The anomaly had become the norm.

…

noredirect=on&utm_term=.b81dd6679eee; Wyatt Andrews and Anna Werner, “Healthcare.gov Plagued by Crashes on 1st Day,” CBS News, October 1, 2013, www.cbsnews.com/news/healthcaregov-plagued-by-crashes-on-1st-day; Adrianne Jeffries, “Why Obama’s Healthcare.gov Launch Was Doomed to Fail,” Verge, October 8, 2013, www.theverge.com/2013/10/8/4814098/why-did-the-tech-savvy-obama-administration-launch-a-busted-healthcare-website; “The Number 6 Says It All About the HealthCare.gov Rollout,” NPR, December 27, 2013, www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2013/12/27/257398910/the-number-6-says-it-all-about-the-healthcare-gov-rollout; Kate Pickert, “Report: Cost of HealthCare.Gov Approaching $1 Billion,” Time, July 30, 2014, http://time.com/3060276/obamacare-affordable-care-act-cost. 2. Marshall Fisher, Ananth Raman, and Anna Sheen McClelland, “Are You Ready?,” Harvard Business Review, August 2000) https://hbr.org/2000/07/are-you-ready. 3. Fisher, Raman, and McClelland, “Are You Ready?” 4. Richard Feynman, Messenger Lectures, Cornell University, BBC, 1964, www.cornell.edu/video/playlist/richard-feynman-messenger-lectures/player. 5. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “The FIDO Rover,” NASA, https://www-robotics.jpl.nasa.gov/systems/system.cfm?System=1. 6. NASA, “Space Power Facility,” www1.grc.nasa.gov/facilities/sec. 7. The discussion on the airbag tests for the Mars Exploration Rovers is based on the following sources: Steve Squyres, Roving Mars: Spirit, Opportunity, and the Exploration of the Red Planet (New York: Hyperion, 2005); Adam Steltzner and William Patrick, Right Kind of Crazy: A True Story of Teamwork, Leadership, and High-Stakes Innovation (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2016). 8.

…

Paradoxically, a measure introduced to boost safety promoted unsafe driving behavior.77 Safety measures also backfired in the Challenger mission. The managers believed that O-rings had a sufficient safety margin “to enable them to tolerate three times the worst erosion observed up to that time.”78 What’s more, there was a fail-safe in place. Even if the primary O-ring failed, the officials assumed the secondary O-ring would seal and pick up the slack.79 The existence of these safety measures boosted a sense of invincibility and led to catastrophe when both the primary and the secondary O-rings failed during launch. These rocket scientists were like German cabbies in ABS-equipped cars, driving fast and loose.

Stephen Hawking

by

Leonard Mlodinow

Published 8 Sep 2020

In the 1980s Feynman would gain fame in popular culture as well, after publishing a few bestselling books of anecdotes, and especially after his work on the presidential commission investigating the 1986 space shuttle Challenger explosion. On that commission he kept his distance from the government-affiliated panelists and became a severe critic of NASA’s approach to safety issues, especially its tendency to underestimate risky flight conditions. Then he single-handedly identified the cause of the tragedy: they had launched the shuttle in dangerously cold weather. The result was a bad seal that developed when rubber joints called O-rings lost their flexibility. He demonstrated the effect on national television by dramatically dropping an O-ring into a glass of ice water and then pounding the ring on the table.

…

Due to difficulties of that sort, when Stephen moved to Cambridge the practitioners of general relativity and cosmology were mainly mathematicians whose work was detached from reality and whose models of the universe were unrealistic. That kept them occupied, but nobody paid much attention to their papers. The low quality of the work prompted Caltech physicist Richard Feynman to write his wife from a 1962 conference on gravity in Warsaw, “Because there are no experiments this field is not an active one…there are hosts of dopes here and it is not good for my blood pressure: such inane things are said and seriously discussed that I get into arguments…” Most physicists concurred that questions of the origin of the universe were dead ends, but those were the questions that had won Stephen’s heart.

…

Quantum theory made it possible for Bekenstein’s entropy theory to be correct. Stephen said that he was annoyed at what he’d discovered and kept it quiet for a while. As he wrote in A Brief History of Time, “I was afraid that if Bekenstein found out about it, he would use it as a further argument to support his ideas.” But as Richard Feynman used to say, physicists don’t tell nature how things behave, nature shows physicists. So Stephen eventually accepted that Bekenstein was correct: black holes have nonzero entropy that is proportional to the surface area of their horizon; they have a nonzero temperature; and they slowly convert the matter and energy they have swallowed up into radiation that they emit back into space, gradually shrinking in the process until they eventually disappear.

Humble Pi: A Comedy of Maths Errors

by

Matt Parker

Published 7 Mar 2019

As part of the refurbishment, they were dismantled into four sections, checked to see how distorted they were, reshaped into perfect circles and put back together. Rubber gaskets called O-rings were placed between the sections to provide a tight seal. It was these O-rings that failed during the launch of Challenger, allowing hot gases to escape from the boosters and start the chain of events which led to its destruction. Famously, during the investigation, Richard Feynman demonstrated how the O-rings lost their elasticity at low temperatures. It was vital that, as the separate sections of the booster moved about, the O-rings sprang back to maintain the seal. In front of the media, Feynman put some of the O-ring rubber in a glass of iced water and showed that it no longer sprang back.

…

The first human launch thus became known as Apollo 4, giving us the niche bit of trivia that Apollo 2 and Apollo 3 never existed. More than just O-rings When the space shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after launch on 28 January 1986, killing all seven people onboard, a Presidential Commission was formed to investigate the disaster. As well as including Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride (the first American woman in space), the commission also featured Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. The Challenger exploded because of a leak from one of the solid rocket boosters. For take-off, the space shuttle had two of these boosters, each of which weighed over 500 tonnes and, amazingly, used metal as fuel: they burned aluminium.

…

In my imaginary cartoon version of human evolution, the false positives of assuming there is a danger when there isn’t are usually not punished as severely as when a human underestimates a risk and gets eaten. The selection pressure is not on accuracy. Wrong and alive is evolutionarily better than correct and dead. But we owe it to ourselves to try to work out these probabilities as best we can. This is what Richard Feynman was faced with during the investigation into the shuttle disaster. The managers and high-up people in NASA were saying that each shuttle launch had only a one in 100,000 chance of disaster. But, to Feynman’s ears, that did not sound right. He realized it would mean there could be a shuttle launch every day for three hundred years with only one disaster.

How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Renegades, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight

by

Julian Guthrie

Published 19 Sep 2016

It was December 23—the best Christmas present ever. — That year had started in a very different way. The space shuttle Challenger had disintegrated seventy-three seconds after liftoff on January 28, 1986, killing the seven astronauts, including a high school teacher, on board. The accident was found to be part mechanical failure, part management failure. Members of the Rogers Commission, appointed to determine the causes of the disaster, found among other things that NASA managers had not accurately calculated the flight risks. Commissioner Richard Feynman, the Caltech physicist and Nobel laureate, concluded, “The management of NASA exaggerates the reliability of its product, to the point of fantasy.”

…

He and his mom passed buildings 10 and 11 and stopped at building 8, the physics department. Created in the nineteenth century by MIT founder William Barton Rogers, the department had among its faculty and graduates a dazzling array of Nobel Prize winners and some of the field’s greatest minds, from Richard Feynman (quantum electrodynamics), Murray Gell-Mann (elementary particles), Samuel Ting and Burton Richter (subatomic particles), to Robert Noyce (Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel), Bill Shockley (field-effect transistors), George Smoot (cosmic microwave background radiation), and Philip Morrison (Manhattan Project, science educator).

…

Where no government filled the need and no immediate profit could fill the bill, the Orteig Prize stimulated multiple different attempts. Where $25,000 was offered, nearly $400,000 was spent to win the prize—because it was there to be won. Peter wanted to do for space what Orteig—through Lindbergh—did for aviation. He now had everyone’s attention. Peter told the cautionary story of Richard Feynman giving a Caltech lecture to the American Physical Society entitled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” where he spoke of building atomic- and molecular-size machinery. To promote the idea, Feynman offered $1,000 to the first person who could build a working electric motor no larger than one sixty-fourth of an inch on each side.

Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension

by

Samuel Arbesman

Published 18 Jul 2016

Despite all the overcomplication of the systems we vitally depend on, I’m ultimately hopeful that humanity can handle what we have built. This book is why. Chapter 1 WELCOME TO THE ENTANGLEMENT On a winter day early in 1986, less than a month after the Challenger disaster, the famous physicist Richard Feynman spoke during a hearing of the commission investigating what went wrong. Tasked with determining what had caused the space shuttle Challenger to break apart soon after takeoff, and who was to blame, Feynman pulled no punches. He demonstrated how plunging an O-ring—a small piece of rubber used to seal the joints between segments of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters—into a glass of ice water would cause it to lose its resilience.

…

because of its creation by some perfect, infinite mind: “The worship of the algorithm” is discussed further in Ian Bogost, “The Cathedral of Computation,” The Atlantic, January 15, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/the-cathedral-of-computation/384300/. CHAPTER 1: WELCOME TO THE ENTANGLEMENT the Challenger disaster: James Gleick, “Richard Feynman Dead at 69; Leading Theoretical Physicist,” The New York Times, February 17, 1988, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/09/21/reviews/feynman-obit.html. car began accelerating uncontrollably: For further information on “unintended acceleration” in Toyota vehicles, see Ken Bensinger and Jerry Hirsch, “Jury Hits Toyota with $3-million Verdict in Sudden Acceleration Death Case,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2013, http://articles.latimes.com/2013/oct/24/autos/la-fi-hy-toyota-sudden-acceleration-verdict-20131024; Ralph Vartabedian and Ken Bensinger, “Runaway Toyota Cases Ignored,” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 2009, http://www.latimes.com/local/la-fi-toyota-recall8-2009nov08-story.html#page=1; Margaret Cronin Fisk, “Toyota Settles Oklahoma Acceleration Case After Verdict,” Bloomberg Business, October 25, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-25/toyota-settles-oklahoma-acceleration-case-after-jury-verdict; Associated Press, “Jury Finds Toyota Liable in Fatal Wreck in Oklahoma,” New York Times, October 25, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/25/business/jury-finds-toyota-liable-in-fatal-wreck-in-oklahoma.html.

…

He demonstrated how plunging an O-ring—a small piece of rubber used to seal the joints between segments of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters—into a glass of ice water would cause it to lose its resilience. This small piece of the spacecraft was sensitive to temperature changes, making it unable to provide a firm seal. These O-rings seem to have been responsible for the catastrophe that cost seven crew members their lives. Contrast this example with another failure, one in the automobile industry. In 2007, Jean Bookout was driving a 2005 Toyota Camry in a small town in Oklahoma when her car began accelerating uncontrollably. She attempted to brake, even using the emergency brake and leaving skid marks on the road. Her efforts did not stop the car, and it crashed into an embankment.

The Six: The Untold Story of America's First Women Astronauts

by

Loren Grush

Published 11 Sep 2023

He’d just demonstrated to a stunned room what NASA’s managers had been reluctant to admit: the O-rings lose their flexibility when they get cold. “I believe that has some significance to our problem,” Richard concluded. It was a small science experiment that Richard Feynman would become famous for. But it all began with a game of telephone in which Sally Ride was a key participant. * * * SALLY MAY HAVE helped crack the case of the O-rings, but the four remaining women in the Six all did their part in the wake of Challenger, whatever it took to keep the space program afloat. At first, Anna and her crew went through the familiar motions of simulations.

…

Just like Sally, Don knew he needed to pass this information on to someone on the commission, preferably someone with fewer ties to the government. Don settled on a target accomplice: the eccentric physicist Richard Feynman. He’d understand the science, and he wouldn’t be afraid to speak about it, loudly. The general decided to invite him for dinner to relay the news. After the meal, Don took the physicist out to his garage to see his 1973 Opel GT. He then removed the vehicle’s carburetor, feigning that he was cleaning it. That’s when he got down to the reason for the visit. “Professor, these carburetors have O-rings in them,” Don told him. “And when it gets cold, they leak.” Richard didn’t say a word, simply processing the information he’d been given.

…

He’d called to tell her that she was being appointed to a presidential commission, helmed by William Rogers, the former secretary of state under Richard Nixon. She and thirteen others would be responsible for deciphering what had caused Challenger to explode a little more than a minute into liftoff. She’d be the only current astronaut on the panel, though she’d be working with some of spaceflight’s biggest names, including Neil Armstrong and Chuck Yeager. Controversial theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, who’d helped develop the atomic bomb, would also serve as a member. It was an enormous ask. But Sally put down the phone and turned to her friends. “I need to do this,” she said

This Will Make You Smarter: 150 New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking

by

John Brockman

Published 14 Feb 2012

The person who has access to his unconscious processes and mines them without getting mired in them can try new approaches, can begin to see things in new ways, and, perhaps, can achieve mastery of his pursuits. In a word: Relax. It was ARISE that allowed Friedrich August Kekulé to use a daydream about a snake eating its tail as inspiration for his formulation of the structure of the benzene ring. It’s what allowed Richard Feynman to simply drop an O-ring into a glass of ice water, show that when cold the ring loses pliability, and thereby explain the cause of the space shuttle Challenger disaster. Sometimes it takes a genius to see that a fifth-grade science experiment is all that is needed to solve a problem. In another word: Play. Sometimes in order to progress, you need to regress. Sometimes you just have to let go and ARISE.

…

Then there’s what we do with the information we have. The core of a scientific lifestyle is to change your mind when faced with information that disagrees with your views, avoiding intellectual inertia, yet many of us praise leaders who stubbornly stick to their views as “strong.” The great physicist Richard Feynman hailed “distrust of experts” as a cornerstone of science, yet herd mentality and blind faith in authority figures is widespread. Logic forms the basis of scientific reasoning, yet wishful thinking, irrational fears, and other cognitive biases often dominate decisions. What can we do to promote a scientific lifestyle?

…

A better understanding of the meaning of “probability”—and especially realizing that we don’t need (and never possess) “scientifically proved” facts but only a sufficiently high degree of probability in order to make decisions—would improve everybody’s conceptual toolkit. Uncertainty Lawrence Krauss Physicist, Foundation Professor, and director, Origins Project, Arizona State University; author, Quantum Man: Richard Feynman’s Life in Science The notion of uncertainty is perhaps the least well understood concept in science. In the public parlance, uncertainty is a bad thing, implying a lack of rigor and predictability. The fact that global warming estimates are uncertain, for example, has been used by many to argue against any action at the present time.

Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, From Missiles to the Moon to Mars

by

Nathalia Holt

Published 4 Apr 2016

How did they handle the sometimes awkward, sometimes wonderful challenges of being a woman, a mother, and a scientist all at once? There was only one way to find out: I’d have to ask them. JANUARY 1958 Launch Day The young woman’s heart was pounding. Her palms were sweaty as she gripped the pencil. She quickly scribbled down the numbers coming across the Teletype. She had been awake for more than sixteen hours but felt no fatigue. Instead, the experience seemed to be heightening her senses. Behind her she could sense Richard Feynman, the famous physicist, peeking at her graph paper. He stood looking over her shoulder, occasionally sighing.

…

The rocket was out of their hands, and they could only hope it would be a success. Success or failure would be ascertained by those at JPL. Back in Pasadena, data began to come across the Teletype. Barbara started her calculations, her pencil moving furiously across the paper. Sitting at the light table, she could sense three very intimidating men towering over her: Richard Feynman, the famed physicist, now at Caltech; Feynman’s former PhD student Al Hibbs, now director of Space Science at JPL; and Lee DuBridge, the president of Caltech. Feynman stood behind her and peeked over her shoulder as she calculated the satellite’s velocity leaving Earth. He was unnaturally calm, a departure from his usually jumpy behavior.

…

Onizuka—wouldn’t survive. The disaster was caused by a rubber loop: an O-ring seal in the right solid rocket booster had failed. The Rogers Commission, tasked by President Reagan with investigating the disaster, later found that concerns over the O-ring were raised years earlier by engineers at the Marshall Space Flight Center. A memo sent in January 1978 from the chief of the Solid Rocket Motor branch at Marshall to his superior specifically pointed out problems with the O-ring and stated that proper sealing of the joint maintained by O-ring pressure was “mandatory to prevent hot gas leaks and resulting catastrophic failure.”

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by

Chris Impey

Published 12 Apr 2015

After a call for proposals from museums and public institutions, NASA distributed the four remaining orbiters: original Shuttles Atlantis and Discovery, Challenger’s replacement Endeavor, and an atmospheric test orbiter named Enterprise. Kennedy Space Center, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the California Science Center, and the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum in New York City were the lucky recipients. 18. After the Challenger disaster, President Reagan formed the Rogers Commission to investigate. In their televised hearings, physicist Richard Feynman had a memorable moment when he dipped an O-ring into a cup of ice water to show how it became less resilient at the low temperatures at the time of launch.

…

The frontier of telepresence is its merger with artificial intelligence, a development foreseen by computer science pioneer Marvin Minsky in 1980.7 A robot doesn’t need to be just a remote extension of a human; it can process information and make its own decisions. This will be exciting, but it will raise fascinating moral and ethical questions, especially if these semiautonomous robots come into contact with each other. Here Come the Bots Richard Feynman was an iconic physicist who won a Nobel Prize for his work in quantum theory. His delight in understanding how nature worked was infectious. In 1959, he wrote an influential essay titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” in which he argued that miniaturization of computers still had a long way to go.

…

In its early years, it was used for a mixture of scientific and military payloads; in its later years, it was used to complete assembly of the International Space Station. It also served as a reminder of the danger and the high cost of space travel.17 On January 28, 1986, a nationwide TV audience was stunned when the Space Shuttle Challenger broke up and exploded in a clear blue winter sky, just seventy-three seconds after launch. Later investigation showed that a leak from an O-ring seal on one of the solid-fuel boosters had led to extreme aerodynamic stress on the spacecraft as it traveled at twice the speed of sound. Millions of schoolchildren were watching because NASA had selected Christa McAuliffe to be the first teacher in space.

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by

Andrew W. Lo

Published 3 Apr 2017

However, when exposed to cold temperatures, rubber becomes more rigid, and it no longer provides an effective seal. Richard Feynman demonstrated this in a simple but unforgettable way at a press conference. He dipped a perfectly flexible O-ring in ice water for a few minutes, took it out, and squeezed it. The O-ring broke apart. The Challenger launched on an unseasonably cold day in Florida—it was so cold that ice had built up on the Kennedy Space Center launch pads the night before—and the O-rings had apparently become stiff. This allowed pressurized hot gases to escape through the seal during the launch.

…

Perhaps the cause was a leak in a liquid oxygen line, or an explosive bolt misfiring, or a flame burning through one of the solid booster rockets … Rumors abounded for weeks before NASA released more data.3 Six days after the disaster, President Reagan signed Executive Order 12546 establishing the Rogers Commission, an impressive fourteen-member panel of experts that included Neil Armstrong, the first person to walk on the moon; Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman; Sally Ride, the first American woman in space; and legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager. On June 6, 1986, a little over five months after the disaster, after conducting scores of interviews, analyzing all the telemetry data from the shuttle’s flight, sifting through the physical wreckage recovered from the Atlantic Ocean, and holding several public hearings, the Rogers Commission concluded that the explosion was caused by the failure of the Shuttle’s now-infamous O-rings on the right solid fuel booster rocket.4 The O-rings were large rubber seals around the joints of the booster rocket, rather like the gasket on a faucet.

…

The evidence assembled by the Commission indicates that no other element of the Space Shuttle system contributed to this failure. 5. The O-ring issue had already been identified in 1985 by engineers at Morton Thiokol. In fact, one of these engineers—Roger Boisjoly—even asked participants at an October meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers conference for assistance with the problem. Moreover, on July 31, 1985—six months prior to the Challenger disaster—Boisjoly (1985) sent an internal memo to Morton Thiokol’s vice president of engineering, R. K. Lund, in which he wrote: This letter is written to insure that management is fully aware of the seriousness of the current O-ring erosion problem in the SRM joints from an engineering standpoint.… The result would be a catastrophe of the highest order—loss of human life.… It is my honest and very real fear that if we do not take immediate action to dedicate a team to solve the problem with the field joint having the number one priority, then we stand in jeopardy of losing a flight along with all the launch pad facilities.

The Zenith Angle

by

Bruce Sterling

Published 27 Apr 2004

Realistically speaking, how could one computer-science professor cure an ailing multibillion-dollar spacecraft? But Van also knew that the job was not hopeless. Such things sometimes happened in real life. For instance: Richard Feynman was just a physicist. But Feynman had dropped a chunk of rubber O-ring into a glass of ice water, and he had shown the whole world, on TV, how a space shuttle could blow up. If Van somehow solved Hickok’s zillion-dollar problem, that would prove that he, Derek Vandeveer, had a top-notch, Richard Feynman kind of class. Van had sacrificed a lot to get his role in public service. He’d given up his happy home, his family life, his civilian career, his peace of mind, and a whole, whole lot of his money.

…

He’d given up his happy home, his family life, his civilian career, his peace of mind, and a whole, whole lot of his money. Van wanted to see real results from all that sacrifice. He wanted to do something vital. The KH-13 was probably the grandest and most secret gizmo that the USA possessed. If Van somehow found the KH-13’s busted O-ring, then he would be giving America the ability to photograph the entire planet, in visible and infrared, day and night, digitally, repeatedly, on a three-inch scale. Yes, that really mattered. Careful not to mention the advice he had gotten from Tony, Van broached the matter with Jeb. Jeb quickly understood the implications.

…

So a better security model would not “lock” or “wall away” anything. Instead, it would scan constantly for evil processes inside the machine. It would hunt for bad acts inside the system, in the way that the bloodstream fights germs. This was an exciting new paradigm. It offered fruitful ways forward that resolved a host of the day’s knottiest security challenges. The concept was a generation ahead of its time. Maybe two generations, given the awful state of the computer market. All the more vital, then, that the CCIAB should pioneer a serious breakthrough like that. They could run it within the Vault, an ideal place to start a working demo for a core audience.

Leaving Orbit: Notes From the Last Days of American Spaceflight

by

Margaret Lazarus Dean

Published 18 May 2015

Months later, the presidential commission tasked with investigating Challenger issued its report. The cause of the explosion had been the solid rocket boosters, whose faulty design combined with the unseasonably cold weather in Florida to create a catastrophic failure. A picture in the paper showed Richard Feynman, a physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project, smirking and holding up a piece of O-ring he’d been soaking in ice water to show that it became brittle. Sally Ride, also on the commission along with Neil Armstrong, sat a few seats away, looking pissed. She’d trusted her life to Challenger twice. Only recently, since her death, has it come to light that the key piece of information about the O-rings had been supplied to another member of the commission by Sally Ride herself.

…

When a shuttle flew with a known issue and came back safely, the tendency among managers was to assume that the issue was not in fact a risk, using the previous success as “evidence.” “Try playing Russian roulette that way,” Richard Feynman remarked after Challenger. CAIB found that after a short period of vigilance, the same error of thinking had crept back into NASA decision making. The board stated in the report that “the causes of the institutional failure responsible for Challenger have not been fixed.” The return-to-flight mission after Columbia was on Discovery, as the return-to-flight mission had been after Challenger. This one was commanded by Eileen Collins, the first woman to command a shuttle mission and one of only two women ever to do so.

…

A special tool used to close the hatch to the crew compartment had broken off, and technicians had been unable to remove it within the launch window. If Challenger had taken off that day, a day much warmer than the fateful January 28, the rubber O-ring in the right solid rocket booster probably would not have stiffened with cold, and burning gases probably would not have escaped to detonate the external tank. Engineers, already aware of the O-ring problem, might have had a chance to fix it before the next attempt to launch in unusually cold weather. The space shuttle program might have moved forward as was intended, with the Department of Defense continuing to use it to deploy spy satellites.

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by

Gabriel Weinberg

and

Lauren McCann

Published 17 Jun 2019

Safety concerns were ignored at the launch meeting. Why were safety concerns ignored? There was a lack of proper checks and balances at NASA. That was the root cause, the real reason the Challenger disaster occurred. As you can see, you can ask as many questions as you need in order to get to the root cause—five is just an arbitrary number. Nobel Prize–winning physicist Richard Feynman was on the Rogers Commission, agreeing to join upon specific request even though he was then dying of cancer. He uncovered the organizational failure within NASA and threatened to resign from the commission unless its report included an appendix consisting of his personal thoughts around root cause, which reads in part: It appears that there are enormous differences of opinion as to the probability of a failure with loss of vehicle and of human life.

…

One technique commonly used in postmortems is called 5 Whys, where you keep asking the question “Why did that happen?” until you reach the root causes. Why did the Challenger’s hydrogen tank ignite? Hot gases were leaking from the solid rocket motor. Why was hot gas leaking? A seal in the motor broke. Why did the seal break? The O-ring that was supposed to protect the seal failed. Why did the O-ring fail? It was used at a temperature outside its intended range. Why was the O-ring used outside its temperature range? Because on launch day, the temperature was below freezing, at 29 degrees Fahrenheit.

…

That’s because mental models unlock the ability to think at higher levels. We hope that you’ve enjoyed reading about them, and that our book has helped you in your super thinking journey. Since many of these concepts may be new to you, you will need to practice using them to get the most out of them. As Richard Feynman famously wrote in his 1988 book, What Do You Care What Other People Think?, “I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.” A related mental model is the cargo cult, as explained by Feynman in his 1974 Caltech commencement speech: In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people.

The Little Black Book of Decision Making

by

Michael Nicholas

Published 21 Jun 2017

The consensus of its members was that the disintegration of the vehicle began after the failure of a seal between two segments of the right solid rocket booster (SRB). Specifically, two rubber O-rings designed to prevent hot gases from leaking through the joint during the rocket motor's propellant burn failed due to cold temperatures on the morning of the launch. One of the commission's members, theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, even demonstrated during a televised hearing how the O-rings became less resilient and subject to failure at the temperatures that were experienced on the day by immersing a sample of the material in a glass of iced water.

…

The night before the launch, Bob Ebeling, one of four engineers at Morton Thiokol who had tried to stop the launch, told his wife that Challenger would blow up.2 In 1985, the problem with the joints was finally acknowledged to be so potentially catastrophic that work began on a redesign, yet even then there was no call for a suspension of shuttle flights. Launch constraints were issued and waived for six consecutive flights and Morton Thiokol persuaded NASA to declare the O-ring problem “closed”. While the O-rings naturally attracted much attention, many other critical components on the aircraft had also never been tested at the low temperatures that existed on the morning of the flight.

…

Multiple Levels of “Truth” Picking up on that last sentence, you might be wondering how “truth” can vary. Our case study of the Challenger shuttle disaster and the subsequent discussion about how mental biases occur illustrates this point: Level 1: the disintegration of the spacecraft began following the failure of the O-rings in one of the joints of the right SRB. This is the most superficial explanation of how the accident happened – true, but also highly incomplete. Level 2: the O-rings would not have had the opportunity to fail had NASA's safety procedures been effective. The reason no solution was found was to do with the culture of the organisations involved, which resulted in years of poor decision making.

Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives

by

Michael Specter

Published 14 Apr 2009

By 1986, America had become so confident in its ability to control the rockets we routinely sent into space that on that particular January morning, along with its regular crew, NASA strapped a thirty-seven-year-old high school teacher named Christa McAuliffe from Concord, New Hampshire, onto what essentially was a giant bomb. She was the first participant in the new Teacher in Space program. And the last. The catastrophe was examined in merciless detail at many nationally televised hearings. During the most remarkable of them, Richard Feynman stunned the nation with a simple display of show-and-tell. Feynman, a no-nonsense man and one of the twentieth century’s greatest physicists, dropped a rubber O-ring into a glass of ice water, where it quickly lost resilience and cracked. The ring, used as a flexible buffer, couldn’t take the stress of the cold, and it turned out neither could one just like it on the shuttle booster rocket that unusually icy day in January.

…

In all, the Vitamin Advisor recommended a daily roster of twelve pills, including an antioxidant and multivitamin, each of which is “recommended automatically for everyone as the basic foundation for insurance against nutritional gaps in the diet.” Since, as he points out on the Web site, finding the proper doses can be a “challenge,” Dr. Weil offered to “take out the guesswork” by calculating the size of every pack, which, over the previous ninety seconds, had been customized just for me. That would take care of one challenge; another would be coming up with the $1,836 a year (plus shipping and tax) my new plan would cost. Still, what is worth more than our health? If that was how much it would cost to improve mine, then that was how much I was willing to spend.

…

With this woman’s blessing, her daughter, who had just given birth, declined to vaccinate her baby. The woman didn’t actually say, “It’s all a conspiracy,” but she didn’t have to. Denialism couldn’t exist without the common belief that scientists are linked, often with the government, in an intricate web of lies. When evidence becomes too powerful to challenge, collusion provides a perfect explanation. (“What reason could the government have for approving genetically modified foods,” a former leader of the Sierra Club once asked me, “other than to guarantee profits for Monsanto?”) “You have a point,” I told the woman. “I really ought to write a book.”

Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk

by

Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak

and

Paul Swartz

Published 8 Jul 2024

“In physics you’re playing against God, and He doesn’t change His laws very often. In finance you’re playing against God’s creatures, agents who value assets based on their ephemeral opinions.” Emanuel Derman, Models. Behaving. Badly.: Why Confusing Illusion with Reality Can Lead to Disaster, on Wall Street and in Life (New York: Free Press, 2011). Richard Feynman is claimed to have said jokingly, “Imagine if protons had feelings,” after the stock market crash of 1987. 13. Letter from John Maynard Keynes to economist Roy Harrod, July 4, 1938, https://economicsociology.org/2018/04/03/what-is-economics-read-keynes-definition/. 14. We are reminded of Ludwig von Mises’s words in Human Action (1949), where he uses understanding in the way we use judgment: “Understanding is not a privilege of the historians.

…

Nouriel Roubinin, “A Greater Depression?” Project Syndicate, March 24, 2020, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/coronavirus-greater-great-depression-by-nouriel-roubini-2020-03. 6. Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak, Martin Reeves, and Paul Swartz, “What the O-Ring Tells Us About Forecasting in the Age of Coronavirus,” BCG Henderson Institute, April 14, 2020, https://bcghendersoninstitute.com/what-the-o-ring-tells-us-about-forecasting-in-the-age-of-coronavirus/. 7. It’s worth considering this quotation from John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1936): “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.

…

As a result, cyclical proclivities will also change slowly over time, much as we showed in figure 3.2. For example, the economy’s vulnerability to real recessions likely falls when the economy’s trend growth strengthens because it is better able to absorb shocks, whether domestic or global. The risk of policy-induced recessions will change with the inflation challenges faced by policymakers. Those challenges will be greater as the era of tight labor markets persists (see chapters 13 and 21); it also implies that the risk of policy-induced recession is higher relative to the 2010s, when it was very low. Financial risks will also change based on the health and complexity of credit intermediation.

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World

by

David Epstein

Published 1 Mar 2019

Decades later, an astronaut who flew on the space shuttle, both before and after Challenger, and then became NASA’s chief of safety and mission assurance, recounted what the “In God We Trust, All Others Bring Data” plaque had meant to him: “Between the lines it suggested that, ‘We’re not interested in your opinion on things. If you have data, we’ll listen, but your opinion is not requested here.’” Physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman was one of the members of the commission that investigated the Challenger, and in one hearing he admonished a NASA manager for repeating that Boisjoly’s data did not prove his point.

…

And now for one last surprise. They all got it wrong. The Challenger decision was not a failure of quantitative analysis. NASA’s real mistake was to rely on quantitative analysis too much. * * * • • • Before ignition, Challenger’s O-rings sat squashed in the joints that connected vertical sections of the booster. At ignition, burning gas came shooting down the booster. The metal walls that connected to form a joint pulled apart for a split second, at which point the rubber O-rings immediately expanded to fill the space and keep the joint sealed. When the O-rings got cold, the rubber hardened and could not expand as quickly.

…

The temperature and engine failure data are taken exactly from NASA’s tragic decision to launch the space shuttle Challenger, with the details placed in the context of racing rather than space exploration. Jake’s face goes blank. Rather than a broken gasket, Challenger had failed O-rings—the rubber strips that sealed joints along the outer wall of the missile-like rocket boosters that propelled the shuttle. Cool temperatures caused O-ring rubber to harden, making them less effective seals. The characters in the case study are loosely based on managers and engineers at NASA and its rocket-booster contractor, Morton Thiokol, on an emergency conference call the night before the Challenger launch. Weather reports on January 27, 1986, predicted unusually cool Florida weather for launch.

The New Science of Asset Allocation: Risk Management in a Multi-Asset World

by

Thomas Schneeweis

,

Garry B. Crowder

and

Hossein Kazemi

Published 8 Mar 2010

The same could be said for the process of investment and the market in which investment products exist. Moreover, the search costs of finding, monitoring, and assessing risk and return are extensive, continuous, and variable. Richard Feynman of physics fame (remember the O-ring and the Challenger story in which Feynman, instead of a lengthy discussion, simply put the rubber O-ring into a cold class of water, pulled it out, showed how inflexible it was when too cold, and thereby showed how cold temperature made it fail—end of story) has pointed out that what works at the “macro” may not work at the “micro” and that “things on a small scale behave nothing like things on a large scale.”

…

Relative risks and returns and the ability to monitor and manage the process by which these evolving assets fit into portfolios will change and will be based on currently unknown relationships and information. Certainly today the challenge is greater, not only because we are working in a more dynamic market but the number of investment vehicles available to investors has increased as well. Hopefully, the following chapters will provide some guidance to meet this challenge. WHAT EVERY INVESTOR SHOULD REMEMBER ■ Much of what we do in asset allocation is based on the tradeoffs between the costs and returns of various approaches to return and risk estimation.

…

The writing of this book began in the early spring of 2009 and concluded in early 2010. Throughout this period, extreme events have occurred. If history is to be a teacher, we know that the future will provide additional information where many of the thoughts and questions within this book will be challenged as well as proven incorrect. Also, throughout this book the reader has been cautioned to be wary of historical data, historical thoughts, and historical performance. In other words show little fear in puncturing myths and their companions. History rarely repeats itself in the same manner; and one of the failings of modern portfolio design as well as some of the recent academic xviii PREFACE and quantitative research is the presumption that it will.

Amazing Stories of the Space Age

by

Rod Pyle

Published 21 Dec 2016

While the crew cabin of the orbiter was blown clear, and continued ascending until it arced into the ocean, survival was impossible. There was no abort system for that phase of the flight—when the SRBs were burning, you were along for the ride no matter what. As the famed physicist Richard Feynman, who was a member of the investigation board, pointed out, the O-rings had not been tested below 50°F. They became brittle when cold, as he famously demonstrated by immersing a piece of one in a glass of ice water and snapping it in two. He ended his summary with, “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”5 There was no better summary of the relaxed safety culture that had taken hold at NASA prior to the accident.

…

There had been multiple warnings prior to the Challenger accident as well. In January 1985, Discovery flew a mission called 51-C. When the SRBs were recovered and disassembled—they came apart into four separate tube segments—severe blowby was seen on some of the O-rings on both SRBs. The rubber gasket, the culprit in the Challenger accident, was severely charred and burned away, allowing hot gas to reach a secondary seal (this too failed on Challenger). The Discovery launch was also the coldest to date, at 53°F.7 This alone should have rung alarm bells when Challenger was attempting to launch on a morning that was only 28°F.

…

The Discovery launch was also the coldest to date, at 53°F.7 This alone should have rung alarm bells when Challenger was attempting to launch on a morning that was only 28°F. After the Challenger incident, the joints between the SRB segments were redesigned to add another O-ring, and also had a rim-capture feature—basically, rather than allowing the joint to bend open if the booster flexed, it would tighten. This is how it should have been designed in the first place. And there were dangers while in orbit as well. Low Earth orbit, where the shuttle operated, is filled with space junk. Debris from exploded satellites, spent rocket boosters, meteorites, and dozens of other sources, orbit Earth at the same altitudes as the shuttle did and the International Space Station does today.

The Wisdom of Crowds

by

James Surowiecki

Published 1 Jan 2004

Six months after the explosion, the Presidential Commission on the Challenger revealed that the O-ring seals on the booster rockets made by Thiokol—seals that were supposed to prevent hot exhaust gases from escaping—became less resilient in cold weather, creating gaps that allowed the gases to leak out. (The physicist Richard Feynman famously demonstrated this at a congressional hearing by dropping an O-ring in a glass of ice water. When he pulled it out, the drop in temperature had made it brittle.) In the case of the Challenger, the hot gases had escaped and burned into the main fuel tank, causing the cataclysmic explosion.

…

If you strip the story down to its basics, after all, what happened that January day was this: a large group of individuals (the actual and potential shareholders of Thiokol’s stock, and the stocks of its competitors) was asked a question—“How much less are these four companies worth now that the Challenger has exploded?”—that had an objectively correct answer. Those are conditions under which a crowd’s average estimate—which is, dollar weighted, what a stock price is—is likely to be accurate. Perhaps someone did, in fact, have inside knowledge of what had happened to the O-rings. But even if no one did, it’s plausible that once you aggregated all the bits of information about the explosion that all the traders in the market had in their heads that day, it added up to something close to the truth.

…

That’s the question that Maloney and Mulherin found so vexing. First, they looked at the records of insider trades to see if Thiokol executives, who might have known that their company was responsible, had dumped stock on January 28. They hadn’t. Nor had executives at Thiokol’s competitors, who might have heard about the O-rings and sold Thiokol’s stock short. There was no evidence that anyone had dumped Thiokol stock while buying the stocks of the other three contractors (which would have been the logical trade for someone with inside information). Savvy insiders alone did not cause that first-day drop in Thiokol’s price.

Inviting Disaster

by

James R. Chiles

Published 7 Jul 2008

The worst damage occurred during the January 1985 cold-weather launch of the Discovery, when five O-rings sustained heat damage. You may have seen the effect of cold weather on rubber. A garden hose left out in winter weather turns as stiff as a pipe regardless of whether it has water in it. During the post-accident investigation, physicist Richard Feynman would demonstrate the principle by dipping a segment of an O-ring into a glass of ice water. In August 1985 top officials from Marshall flew to Utah to talk over the problem with Morton Thiokol management. Roger Boisjoly, a seal engineer with Thiokol, got the assignment to put together a “Seal Task Force” to come up with a quick solution.

…

For an ordinary pipeline this would have been fine, but not for the high-powered, hot-firing boosters. One challenge was that at each field joint a thin air gap remained between the solid fuel castings in each segment. Without some precautions, flame would fill this gap during a launch and attack the half-inch-thick steel of the booster’s outer casing. To keep the flame at the core of the booster where it belonged, the field joints had heat-resistant putty to close off the gap between the fuel castings, and two rubber O-rings fitted into the rim-and-slot arrangement as a final seal. FIGURE 4: SPACE SHUTTLE CHALLENGER PROBABLE SEQUENCE 1. Cold temperatures before launch reduce sealing ability of O-rings inside Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) field joints. 2.

…

If Boisjoly, prisoner of bureaucracy that he was, had been allowed the proverbial single phone call, I wish he could have summoned Dick Scobee, the Challenger’s commander, to the telecon. Scobee would have heard that his flight the next day was going to be an off-the-chart experiment. The Challenger’s solid rocket boosters would be operating well outside of their tested boundaries, going farther up a sketchy but suggestive trend line of gas leaks that were becoming so common that the engineers had been finding them on almost every other flight. The crew could have heard that the flight was shaded with an element of danger simply because every flight under cold conditions showed damage to the O-rings. It would have given Scobee a choice, and the chance to insist on more information from NASA and Morton Thiokol.

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by

Tim Fernholz

Published 20 Mar 2018

It was the worst NASA accident since a harrowing 1967 episode in which an Apollo space capsule burst into flame during a routine pre-launch test, killing the three astronauts on board. Challenger led to serious reconsideration of US space policy. The loss of the seven astronauts who perished in that venture convinced the top brass at NASA that it was too risky to put humans on every flight into space. That was especially true of those missions intended to launch satellites or space probes, with no real human exploration component. Since the shuttle was designed expressly for human spaceflight, this conclusion required the government to find new rockets to launch satellites without people on board. Noble Prize–winning physicist Richard Feynman, a member of the distinguished panel investigating the disaster, famously demonstrated the tiny flaw that had led to Challenger’s loss.

…

Noble Prize–winning physicist Richard Feynman, a member of the distinguished panel investigating the disaster, famously demonstrated the tiny flaw that had led to Challenger’s loss. He dunked rubber O-rings, used in the construction of the solid fuel rocket booster, into a pitcher of cold water. At lower temperatures, the tight-fitting seals became brittle and stiff, making them likelier to crack under pressure and leak superheated gas. On launch day, temperatures had fallen below freezing—well below acceptable conditions for the rocket boosters—and warnings from the engineers who built the boosters apparently never made it up the chain to NASA management.

…

Indeed, the US reliance on just one launch vehicle for space access had worried some Americans, especially as delays and cost overruns in the shuttle program mounted, but it was not until Challenger that the government was forced to reckon with the consequences of its policy. “The government put all their eggs in one basket,” John Garvey, a veteran aerospace engineer who began his career the year of the Challenger disaster and spent the following decades developing rocket technology at McDonnell Douglas, Boeing, and a series of space start-ups, told me. “The shuttle was flawed because it tried to do everything for everybody, and it ended up not satisfying anybody.

Warnings

by

Richard A. Clarke

Published 10 Apr 2017

Rather than creating an airtight seal, hot combustion gases were burning through the putty, leaking into the joints, and burning the O-rings. Moreover, this problem, which became known as joint rotation, was exacerbated by cold temperatures. Boisjoly was a solid rocket booster engineer at Morton-Thiokol. He became seriously concerned, not only by the joint rotation itself, but by the fact that NASA continued pressing ahead with Shuttle launches with the consent of the Morton-Thiokol management, despite not having found an acceptable fix. Among top officials in both organizations, the O-ring problem became viewed as an acceptable flight risk. In a memo dated July 31, 1985, about six months before the Challenger incident, Boisjoly warned Thiokol’s vice president of Engineering that the O-ring issues were a disaster in the making, ominously predicting that the “result would be catastrophic of the highest order—loss of human life.”

…

In a memo dated July 31, 1985, about six months before the Challenger incident, Boisjoly warned Thiokol’s vice president of Engineering that the O-ring issues were a disaster in the making, ominously predicting that the “result would be catastrophic of the highest order—loss of human life.” Boisjoly’s warnings were ignored. The morning before Challenger’s final flight, the temperature forecast was 30 degrees Fahrenheit, far colder than any previous Shuttle launch. Boisjoly and his engineering colleagues at Thiokol argued that, due to past O-ring performance problems, the temperature posed an unacceptable risk to the safety of the launch. These Cassandras were unable to persuade NASA and Morton-Thiokol’s management, who were under pressure after several previous aborted launch attempts.

…

After the hearing, surrounded by reporters, Hansen said, “It is time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here.” The next day his words were the New York Times “Quotation of the Day.”7 We were curious about what it took for Hansen to see global warming first, and in particular, if it required a lot of individual resolve or belief in himself. He referenced the physicist and Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman: “Well, I’m not a person who has a great deal of self-confidence. And I’ve considered that an advantage; Feynman says that ‘You have to be very skeptical of any conclusion, especially your own because you are the easiest person to fool.’ Often you start out, you want some answer, you think you know some answer and you try to persuade yourself.

The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy

by

Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

Published 16 May 2011

A year later, when Fermi died at the age of 53, Bayes’ rule lost a stellar supporter in the physical sciences. Fermi was not the only important physicist to use Bayesian methods during this period. A few years later, at Cornell University, Richard Feynman suggested using Bayes’ rule to compare contending theories in physics. Feynman would later dramatize a Bayesian study by blaming rigid O-rings for the Challenger shuttle explosion. During this exciting period in 1950s Chicago, Savage and Allen Wallis founded the university’s statistics department, and Savage attracted a number of young stars in the field. Reading widely, Savage discovered the work of Émile Borel, Frank Ramsey, and Bruno de Finetti from the 1920s and 1930s legitimizing the subjectivity in Bayesian methods.

…

Because SAC bombers had a monopoly on transporting America’s nuclear arsenal and General LeMay sat at the pinnacle of the world’s military might, RAND’s voice was often influential. By the time Savage visited Santa Monica that summer RAND reports had already challenged some of SAC’s sacred cows. To drop nuclear weapons on Soviet targets, macho air force pilots wanted to fly the new B-52 Strato-fortress jets; RAND recommended fleets of cheaper conventional planes. RAND had also described SAC’s overseas bases for manned bombers as sitting ducks for Soviet attack. A year after Savage’s visit, RAND would challenge Cold War dogma by arguing that victors typically fare better with negotiated settlements than with unconditional surrenders.

…