Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Apr 2008 · 304pp · 22,886 words

R. Sunstein Yale University Press New Haven & London A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. Copyright © 2008 by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that

…

in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thaler, Richard H., 1945– Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness / Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12223-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Economics— Psychological aspects. 2

…

.” Journal of Business Venturing 3, no. 2 (1988): 97– 108. Cronqvist, Henrik. “Advertising and Portfolio Choice.” Working paper, Ohio State University, 2007. Cronqvist, Henrik, and Richard H. Thaler. “Design Choices in Privatized Social-Security Systems: Learning from the Swedish Experience,” American Economic Review 94, no. 2 (2004): 425–28. Cropper, Maureen L., Sema

…

/042507AndrewCuomotestimony.pdf. Daughety, Andrew, and Jennifer Reinganum. “Stampede to Judgment.” American Law and Economics Review 1 (1999): 158–89. De Bondt, Werner F. M., and Richard H. Thaler. “Do Security Analysts Overreact?” American Economic Review 80, no. 2 (1990): 52–57. Department of Health and Human Services. “Medicare Drug Plans Strong and Growing

…

Hershey, Jacqueline Meszaros, and Howard Kunreuther. “Framing, Probability Distortions, and Insurance Decisions.” In Kahneman and Tversky (2000), 224–40. Jolls, Christine, Cass R. Sunstein, and Richard Thaler. “A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics.” Stanford Law Review 50 (1998): 1471–1550. Jones-Lee, Michael, and Graham Loomes. “Private Values and Public Policy

…

A. Redelmeier. “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End.” Psychological Science 4 (1993): 401–5. Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler. “Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 1325–48. ———. “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and

…

Status Quo Bias.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (1991): 193–206. Kahneman, Daniel, and Richard H. Thaler. “Anomalies: Utility Maximization and Experienced Utility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, no. 1 (2006): 221–34. Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky, eds. Choices, Values, and

…

–1216. Sunstein, Cass R., David Schkade, Lisa Ellman, and Andres Sawicki. Are Judges Political? Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2006. Sunstein, Cass R., and Richard H. Thaler. “Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron.” University of Chicago Law Review 70 (2003): 1159–1202. Sunstein, Cass R., and Edna Ullman-Margalit. “Second-Order Decisions

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

a sharp-witted guy, and the comment was written in his usual swashbuckling style. They started their paper this way: “Charles Lee, Andrei Shleifer, and Richard Thaler (1991) claim to solve not one, but two, long-standing puzzles—discounts on closed-end funds and the small firm effect. Both, according to Lee

…

. 2002. “Online Investors: Do the Slow Die First?” Review of Financial Studies 15, no. 2: 455–88. Barberis, Nicholas C., and Richard H. Thaler. 2003. “A Survey of Behavioral Finance.” In Nicholas Barberis, Richard H. Thaler, George M. Constantinides, M. Harris, and René Stulz, eds., Handbook of the Economics of Finance, vol. 1B, 1053–128. Amsterdam

…

-a-behavioural-trial. Bénabou, Roland, and Jean Tirole. 2003. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation.” Review of Economic Studies 70, no. 3: 489–520. Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler. 1995. “Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110, no. 1: 73–92. ———. 1999. “Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in

…

, no. 2: 180–5. ———. 2009. “Reinforcement Learning and Savings Behavior.” Journal of Finance 64, no. 6: 2515–34. Chopra, Navin, Charles Lee, Andrei Shleifer, and Richard H. Thaler. 1993a. “Yes, Discounts on Closed-End Funds Are a Sentiment Index.” Journal of Finance 48, no. 2: 801–8. ———. 1993b. “Summing Up.” Journal of Finance

…

Strong?” Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco: Economic Letter 10: 1–5. Dawes, Robyn M., and Richard H. Thaler. 1988. “Anomalies: Cooperation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2, no. 3: 187–97. De Bondt, Werner F. M., and Richard H. Thaler. 1985. “Does the Stock Market Overreact?” Journal of Finance 40, no. 3: 793–805. De Long

…

. 12: 1713–6. Johnson, Steven. 2010. Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation. New York: Riverhead. Jolls, Christine, Cass R. Sunstein, and Richard Thaler. 1998. “A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics.” Stanford Law Review 50, no. 5: 1471–550. Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York

…

: Macmillan. ———, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler. 1986. “Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics.” Journal of Business 59, no. 4, part 2: S285–300. ———. 1991. “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and

…

, Josef, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1994. “Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation, and Risk.” Journal of Finance 49, no. 5: 1541–78. Lamont, Owen A., and Richard H. Thaler. 2003. “Can the Market Add and Subtract? Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs.” Journal of Political Economy 111, no. 2: 227–68. Landsberger, Michael. 1966

…

. “Windfall Income and Consumption: Comment.” American Economic Review 56, no. 3: 534–40. Lee, Charles, Andrei Shleifer, and Richard H. Thaler. 1991. “Investor Sentiment and the Closed-End Fund Puzzle.” Journal of Finance 46, no. 1: 75–109. Lester, Richard A. 1946. “Shortcomings of Marginal Analysis

…

Unrest and the Quality of Production: Evidence from the Construction Equipment Resale Market.” Review of Economic Studies 75, no. 1: 229–58. Massey, Cade, and Richard H. Thaler. 2013. “The Loser’s Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the National Football League Draft.” Management Science 59, no. 7: 1479–95. McGlothlin, William

…

Face of Experience, Competition, and High Stakes.” American Economic Review 101, no. 1: 129–57. Post, Thierry, Martijn J. van den Assem, Guido Baltussen, and Richard H. Thaler. 2008. “Deal or No Deal? Decision Making under Risk in a Large-Payoff Game Show.” American Economic Review 98, no. 1: 38–71. Poterba, James

…

S., and William Kinney. 1976. “Capital Market Seasonality: The Case of Stock Returns.” Journal of Financial Economics 3, no. 4: 379–402. Russell, Thomas, and Richard H. Thaler. 1985. “The Relevance of Quasi Rationality in Competitive Markets.” American Economic Review 75, no. 5: 1071–82. Sally, David. 1995. “Conversation and Cooperation in Social

…

K. 1977. “Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 6, no. 4: 317–44. Shafir, Eldar, and Richard H. Thaler. 2006. “Invest Now, Drink Later, Spend Never: On the Mental Accounting of Delayed Consumption.” Journal of Economic Psychology 27, no. 5: 694–712. Shapiro, Matthew

…

, Hersh M., and Meir Statman. 1984. “Explaining Investor Preference for Cash Dividends.” Journal of Financial Economics 13, no. 2: 253–82. Shefrin, Hersh M., and Richard H. Thaler. 1988. “The Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis.” Economic Inquiry 26, no. 4: 609–43. Shiller, Robert J. 1981. “Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be

…

/2013-05-30/in-australia-retirement-saving-done-right. Sunstein, Cass R. 2014. “The Ethics of Nudging.” Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2526341. ———, and Richard H. Thaler. 2003. “Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron.” University of Chicago Law Review 70, no. 4: 1159–202. Telser, L. G. 1995. “The Ultimatum Game and

…

.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/369572/research-report-9-opt-out.pdf. van den Assem, Martijn J., Dennie van Dolder, and Richard H. Thaler. 2012. “Split or Steal? Cooperative Behavior When the Stakes Are Large.” Management Science 58, no. 1: 2–20. von Neumann, John, and Oskar Morgenstern. 1947

…

Lloyd, 270 Yahoo, 248n Yao Ming, 271n Zamir, Eyal, 269 Zeckhauser, Richard, 13–14, 178 in behavioral economics debate, 159 Zingales, Luigi, 274 ALSO BY RICHARD H. THALER Quasi-Rational Economics The Winner’s Curse: Paradoxes and Anomalies of Economic Life Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Cass R. Sunstein

…

) Copyright © 2015 by Richard H. Thaler All rights reserved First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth

…

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Thaler, Richard H., 1945– Misbehaving : the making of behavioral economics / Richard H. Thaler. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-393-08094-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Economics—Psychological aspects. I. Title. HB74

Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life

by Rory Sutherland · 6 May 2019 · 401pp · 93,256 words

Club. We would regard such partisanship as absurd, yet devoted fans of logic control the levers of power everywhere. The Nobel Prize-winning behavioural scientist Richard Thaler said, ‘As a general rule the US Government is run by lawyers who occasionally take advice from economists. Others interested in helping the lawyers out

…

they should. It is to correct this circular logic that behavioural economics – made famous by experts such as Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Dan Ariely and Richard Thaler – has come to prominence. In many areas of policy and business there is much more value to be found in understanding how people behave in

…

New Jersey* there seemed to be few arguments for using JFK: Newark is closer to Manhattan, and risks fewer roadworks or delays on the journey. Richard Thaler, one of the world’s most eminent decision scientists, tweeted me with strong support for Newark.* If it were only informed consumers making the choice

…

, and context and framing matter. One of my favourite ever experiments on the perception of price and value came from the father of ‘Nudge Theory’, Richard Thaler. He asked a group of sophisticated wine enthusiasts to imagine that they had bought a bottle of vintage wine (that was now worth $75) some

…

interpretation: that pilot was perhaps cleverer than he knew. One of most amusing and telling stories in the recent history of behavioural economics appears in Richard Thaler’s memoir, Misbehaving (2015), when he describes what happened when the University of Chicago Economics Faculty was required to move to a new building. These

…

a pension more appealing, particularly to younger people, without requiring such a high level of financial subsidy. We were all impressed by the work that Richard Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi had already performed in this field: together, they conceived a new mechanism for pension-saving that acknowledges one of the central principles

…

(6 September 2012). ‘. . . and more by our perception of it’, ‘The Vodka-Red-Bull Placebo Effect’, Atlantic (8 June 2017). ‘. . . the father of ‘Nudge Theory’, Richard Thaler’ Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008). ‘. . . often outdone by the taste of the latter’.’, Lucas Derks and Jaap

The Art of Execution: How the World's Best Investors Get It Wrong and Still Make Millions

by Lee Freeman-Shor · 8 Sep 2015 · 121pp · 31,813 words

, by Mohnish Pabrai (2007). 24 ‘Gambling with the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice’, Management Science, Richard H. Thaler and Eric J. Johnson, (1990). Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=1424076 25 Lynch (2000). 26 ‘Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk’, Econometrica

…

:00am, have two helpings of chocolate decadence, and a variety of Aquavit at a Norwegian restaurant.”37 4. Fear The research of Shlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler also showed that the pain of a short-term loss overpowers the pleasure of a long-term gain. This myopic (short-term) focus and a

…

100 percent year.”60 * * * 34 Lynch (2000). 35 Ibid. 36 ‘Some Empirical Evidence on Dynamic Inconsistency’, Economic Letters, by Richard Thaler (1981). 37 ‘Anomalies: Intertemporal Choice’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, George Loewenstein and Richard H. Thaler (1989). 38 ‘Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in Repeated Gambles and Retirement Investments’, Management Science, by Shlomo Benartzi and

…

Richard Thaler (1999). They showed that the pain of a short-term loss overpowers the pleasure of a long-term gain. This

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

even an absurd, influence on the market.”7 Two economists known for research into both market behavior and individual decision-making, Werner De Bondt and Richard Thaler, theorized that it is this overreaction to meaningless price movements that creates the conditions for mean reversion. De Bondt and Thaler speculated that investors overreact

…

.1â•… Cumulative Average Returns for Winner and Loser Portfolios of 35 Stocks over 36 months (1933 to 1982) Source: Werner F.M. De Bondt and Richard H. Thaler. “Does the Stock Market Overreact?” Journal of Finance 40 (3) (1985): 793–805. words, a stock price that has fallen a great deal becomes a

…

Share for Stocks in Winner and Loser Portfolios (1966 to 1983) Source: Eyquem Investment Management LLC using data from Werner F.M. De Bondt and Richard H. Thaler. “Further Evidence on Investor Overreaction and Stock Market Seasonality?” Journal of Finance 42 (3) (1987): 557–581. portfolio—the stocks with the largest market price

…

Average Earnings Per Share for Undervalued and Overvalued Portfolios (1926 to 1983) Source: Eyquem Investment Management LLC using data from Werner F.M. DeBondt and Richard H. Thaler. “Further Evidence on Investor Overreaction and Stock Market Seasonality?” Journal of Finance 42 (3) (1987): 557–581. portfolios in the three years leading up to

…

, 1886. 7. J. M. Keynes. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 1936. 8. Werner F.M. De Bondt and Richard H. Thaler. “Does the Stock Market Overreact?” Journal of Finance 40 (3) (1985): 793–805. 9. W. De Bondt and R. Thaler. “Further Evidence on Investor Overreaction

Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (And How to Take Advantage of It)

by William Poundstone · 1 Jan 2010 · 519pp · 104,396 words

their focus groups.” Today there is a symbiosis between psychologists studying prices and the marketing and price consultant communities. Many leading theorists, including Tversky, Kahneman, Richard Thaler, and Dan Ariely, have published important work in marketing journals. Price consultant Simon-Kucher & Partners has an academic advisory board with scholars from three continents

…

greatly diminished. This was an early description of what’s now known as the endowment effect (a name coined by the University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler in 1980). In the absence of market values, selling prices are typically twice as much as buying prices (above and beyond any strategic exaggeration for

…

a price is to build a valuation (rather than to excavate deep into the psyche and uncover one). A 1990 paper by Amos Tversky and Richard Thaler took its imagery from America’s great wellspring of metaphors, baseball. It involves the old joke about the three umpires: “I call them as I

…

be interested in another field if they weren’t. They did believe that there were a few economists willing to learn psychology, and they mentioned Richard Thaler. Shortly thereafter, Wanner was appointed president of the Russell Sage Foundation. The long-dead Russell Sage, a Wall Street speculator and notorious miser, left a

…

. In turn, a reasonable proposer should anticipate that and offer a token amount, in blissful confidence of its being accepted. That didn’t happen. When Richard Thaler tried this game on students at Cornell, he found that a “fair” fifty-fifty split was by far the most common proposer offer. He also

…

shows how hypocritical people are. When no one was watching, but only then, subjects were nearly as selfish as the economists postulated. Colin Camerer and Richard Thaler proposed an alternative interpretation: The outcomes of ultimatum and dictator games have less to do with altruism than with manners. Social norms of fair play

…

decision theorists, except that the sums of money are large and real. A 2008 article by Thierry Post, Martijn van den Assem, Guido Baltussen, and Richard Thaler notes that Deal or No Deal “almost appears to be designed to be an economics experiment rather than a TV show.” Aside from the leggy

…

the drive saves exactly $5. “Why are we more willing to drive across town to save money on a small purchase than a large one?” Richard Thaler asked. “Clearly there is some psychophysics at work here. Five dollars seems like a significant saving on a $15 purchase, but not so on a

…

findings have been widely adopted, with markets putting their main entrance on the right of the store’s layout to encourage counterclockwise shopping. One of Richard Thaler’s best-known thought experiments concerns a grocery store. You’re lying on a beach on a hot day and desperately want a cold beer

…

effectiveness of bundling. It fosters confusion. A restaurant’s prix fixe pricing prevents diners from getting upset about paying $13 for two scallops (an example Richard Thaler found in a San Francisco Zagat guide). It’s hard to be sure what costs what and whether it’s too much. The bundling effect

…

having something you want and can easily afford. Even erstwhile spendthrifts find it hard to follow this advice. It’s the principle of the thing . . . Richard Thaler explains this with the concept of “transaction utility.” When the consumer believes an item’s true value is more than its selling price, the purchase

…

best at pushing consumers’ buttons. However different the products, human nature is pretty much the same. Central to the infomercial industry is a principle that Richard Thaler calls “Don’t wrap all the Christmas presents in one box.” In a 1985 paper in the journal Marketing Science, “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice

…

the number of minutes used. The per-minute tab is surprisingly large because many customers who don’t talk much nevertheless choose flat-rate plans. Richard Thaler has explained this as a consequence of prospect theory. Just as infomercials slice and dice the product into many little bonuses, an opposite rule says

…

that rebates cast a magic spell. People are more inclined to buy a $200 printer with a $25 rebate than a similar printer for $175. Richard Thaler explains rebates as psychophysical arbitrage. The $200 does not seem that much higher than $175, first of all. But there’s a big psychological difference

…

. The first great scholar of hyperinflation psychology was Irving Fisher (1867–1947), an economist currently experiencing a revival of interest. No less a figure than Richard Thaler has hailed Fisher as a pioneer of behavioral economics. One of Amos Tversky’s last papers treated Fisher’s concept of a “money illusion,” a

…

what it would cost to replace it today) (e) Negative $55 (since you’re getting a $75 bottle of wine for only $20) In 1996 Richard Thaler and Eldar Shafir posed this question to a group of wine collectors subscribing to a wine newsletter. Many must have encountered this kind of situation

…

Sara Solnick’s interest in gender and bargaining. As a young economics student she signed up for a summer institute sponsored by Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. There she came across T-shirts asking “Does Homo Economicus Exist?” “They critiqued the existing models of economic man, but they still thought it was

…

of Marketing Research, in press. ———, George Loewenstein, and Drazen Prelec (2005). “Neuroeconomics: How Neuroscience Can Inform Economics.” Journal of Economic Literature 43, 9–64. ———, and Richard Thaler (1995). “Ultimatums, Dictators and Manners.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, 209–19. Carey, Benedict (2007). “Who’s Minding the Mind?” The New York Times

…

T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, and D. Kahneman (eds.), Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. New York: Cambridge University Press. ———, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler. (1986a). “Fairness as a Constraint on Profit Seeking: Entitlements in the Market.” The American Economic Review 76, 728–41. ———, Jack L. Knetsch, and

…

Richard Thaler. (1986b). “Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics.” The Journal of Business 59, S285–S300. ———, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler (1991). “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and the Status Quo Bias.” The Journal of Economic

…

, July 4, 2007. Knetsch, Jack (1989). “The Endowment Effect and Evidence of Nonreversible Indifference Curves.” The American Economic Review 79, 1277–84. Knetsch, Jack L., Richard Thaler, and Daniel Kahneman (1986). “Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem.” Simon Fraser University Working Paper, 1988. Kouri, Elena, Scott Lukas, Harrison

…

: Penguin. Plous, Scott (1993). The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Post, Thierry, Martijn J. van den Assem, Guido Baltussen, and Richard H. Thaler (2008). “Deal or No Deal? Decision Making Under Risk in a Large-Payoff Game Show.” The American Economic Review 98, 38–71. Purcell, Frank (1969

…

Review 90, 293–315. ———(1991). “Loss Aversion and Riskless Choice: A Reference Dependent Model.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106, 204–17. Tversky, Amos, and Richard Thaler (1990). “Anomalies: Preference Reversals.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, 201–11. Tversky, Amos, Shmuel Sattath, and Paul Slovic (1988). “Contingent Weighting in Judgment and

Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

by Dan Ariely · 19 Feb 2007 · 383pp · 108,266 words

Heyman, Yesim Orhun, and Dan Ariely, “Auction Fever: The Effect of Opponents and Quasi-Endowment on Product Valuations,” Journal of Interactive Marketing (2004). RELATED READINGS Richard Thaler, “Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (1980). Jack Knetsch, “The Endowment Effect and Evidence of Nonreversible Indifference Curves

…

,” American Economic Review, Vol. 79 (1989), 1277–1284. Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler, “Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem,” Journal of Political Economy (1990). Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol

…

BASED ON Dan Ariely and Jonathan Levav, “Sequential Choice in Group Settings: Taking the Road Less Traveled and Less Enjoyed,” Journal of Consumer Research (2000). Richard Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi, “Save More Tomorrow: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Savings,” Journal of Political Economy (2004). RELATED READINGS Eric J. Johnson and Daniel

Pound Foolish: Exposing the Dark Side of the Personal Finance Industry

by Helaine Olen · 27 Dec 2012 · 375pp · 105,067 words

new ways and in new settings,” and thus raise their salaries, beat income inequality, and avoid both unplanned retirement and inadequate savings. Behavioral economics star Richard Thaler, then a professor at Cornell University’s business school, testified that he believed, over time, both 401(k) and individual retirement accounts would push up

…

things like put the papers aside to fill out another day—another day which, needless to say, never comes. As a remedy, behavioral economists like Richard Thaler, best known as the co-author of the bestselling book Nudge, began advocating automatic enrollment plans, under which people only need to sign papers if

…

National Life, Prudential Securities, The Vanguard Group, and Wachovia. But Allianz scored a public-relations coup when behavioral finance industry superstar and Nudge co-author Richard Thaler, who serves on their “academic advisory board” (and whose asset management firm Fuller & Thaler is also affiliated with Allianz), discussed annuities in his monthly New

…

literacy of the American public has remained dismal in the almost two decades since the movement began. As a result of all this, economists like Richard Thaler have come forward to denounce the movement. “The depressing truth is that financial literacy is impossible,” Thaler said an interview in the Economist. In US

…

_fee-disclosure-plan-sponsors-fees-and-expenses. As a remedy: “Should Policies Nudge People to Save?” Wall Street Journal Econblog (Richard Thaler comments), May 25, 2007, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB117977357721809835.html; Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008); African Americans

…

/b4218045699286.htm. Shlomo Benartzi: Anderson Graduate School of Management at UCLA: http://www.anderson.ucla.edu/x5515.xml. But Allianz scored a public relations coup: Richard H. Thaler, “The Annuity Puzzle,” New York Times, June 4, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/05/business/economy/05view.html; Paul J. Isaac, letter to

…

of Columbia, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, April 12, 201, http://www.gao.gov/assets/130/125996.pdf. economists like Richard Thaler have come forward to denounce the movement: “Getting it Right on the Money,” The Economist, April 3, 2008, http://www.economist.com/node/10958702; Kimberly

Retirementology: Rethinking the American Dream in a New Economy

by Gregory Brandon Salsbury · 15 Mar 2010 · 261pp · 70,584 words

fascinating research and study. Notably, I recommend Choices, Values, and Frames by Kahneman and Tversky; Beyond Greed and Fear by Hersh Shefrin; Nudge, written by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein; the investor behavior studies on 401(k)s by Shlomo Benartzi; articles, books and research by Meir Statman; Against the Gods, The

…

. Regularly Increase Your Contribution Rate The automatic payroll deduction structure of 401(k) accounts can help investors stick to a more disciplined retirement plan. Professor Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago, and Professor Shlomo Benartzi of UCLA, took this strategy one step further. They created a program called Save More Tomorrow

…

willing to risk loss, they would need to see their gains reach at least 2.25 times the potential loss. This is what led Dr. Richard Thaler to conclude that losses hurt 2.25 times more than gains satisfy. When most investors experience loss, they spend the rest of their lives in

…

Heath, Chip, and Amos Tversky, “Preference and Belief: Ambiguity and Competence in Choice under Uncertainty,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1991. 13 Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler, National Bureau of Economic Research, “Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior,” 2007. 14 Science Direct, “Information friction and investor home bias: A perspective on

…

enjoyable than trying to meet the $200 threshold he’s set for himself driving the cab. “Opportunity costs,” according to Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky and Richard Thaler, “typically receive much less weight than out-of-pocket costs.”9 It’s conceivable that if the cab driver were to maximize the opportunity to

Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty

by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 25 Apr 2011 · 370pp · 112,602 words

the “right” thing, while, perhaps, leaving them the freedom to opt out. In their best-selling book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, an economist and a law scholar from the University of Chicago, recommend a number of interventions to do just this.38 An

…

the University of Chicago, George Lowenstein from Carnegie-Mellon, Matthew Rabin from Berkeley, David Laibson from Harvard, and others, whose work we cite here. 38 Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New York: Penguin, 2008). 39 See a comparative cost-effectiveness analysis on the

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by Evgeny Morozov · 15 Nov 2013 · 606pp · 157,120 words

Die With Zero: Getting All You Can From Your Money and Your Life

by Bill Perkins · 27 Jul 2020 · 200pp · 63,266 words

Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk

by Peter L. Bernstein · 23 Aug 1996 · 415pp · 125,089 words

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone

by John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai · 25 Jul 2025

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

Why Nudge?: The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism

by Cass R. Sunstein · 25 Mar 2014 · 168pp · 46,194 words

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman · 24 Oct 2011 · 654pp · 191,864 words

Wait: The Art and Science of Delay

by Frank Partnoy · 15 Jan 2012 · 342pp · 94,762 words

Dollars and Sense: How We Misthink Money and How to Spend Smarter

by Dr. Dan Ariely and Jeff Kreisler · 7 Nov 2017 · 302pp · 87,776 words

Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2009 · 471pp · 97,152 words

Beyond the Random Walk: A Guide to Stock Market Anomalies and Low Risk Investing

by Vijay Singal · 15 Jun 2004 · 369pp · 128,349 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

The Irrational Bundle

by Dan Ariely · 3 Apr 2013 · 898pp · 266,274 words

Expected Returns: An Investor's Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards

by Antti Ilmanen · 4 Apr 2011 · 1,088pp · 228,743 words

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy Siegel · 7 Jan 2014 · 517pp · 139,477 words

The Elements of Choice: Why the Way We Decide Matters

by Eric J. Johnson · 12 Oct 2021 · 362pp · 103,087 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Irrational Exuberance: With a New Preface by the Author

by Robert J. Shiller · 15 Feb 2000 · 319pp · 106,772 words

More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded)

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 1 Jan 2006 · 348pp · 83,490 words

Mindware: Tools for Smart Thinking

by Richard E. Nisbett · 17 Aug 2015 · 397pp · 109,631 words

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy J. Siegel · 18 Dec 2007

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 Apr 2005 · 339pp · 95,988 words

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 2 Jul 2009 · 387pp · 110,820 words

Scarcity: The True Cost of Not Having Enough

by Sendhil Mullainathan · 3 Sep 2014 · 305pp · 89,103 words

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction

by Matthew B. Crawford · 29 Mar 2015 · 351pp · 100,791 words

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by Nate Silver · 31 Aug 2012 · 829pp · 186,976 words

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

Work Rules!: Insights From Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead

by Laszlo Bock · 31 Mar 2015 · 387pp · 119,409 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

The Power of Passive Investing: More Wealth With Less Work

by Richard A. Ferri · 4 Nov 2010 · 345pp · 87,745 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

The Age of the Infovore: Succeeding in the Information Economy

by Tyler Cowen · 25 May 2010 · 254pp · 72,929 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives

by Lisa Servon · 10 Jan 2017 · 279pp · 76,796 words

The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good

by Robert H. Frank · 3 Sep 2011

Investing Amid Low Expected Returns: Making the Most When Markets Offer the Least

by Antti Ilmanen · 24 Feb 2022

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of Counterintuition

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 6 Nov 2012 · 256pp · 60,620 words

The Irrational Economist: Making Decisions in a Dangerous World

by Erwann Michel-Kerjan and Paul Slovic · 5 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 108,119 words

Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge

by Cass R. Sunstein · 23 Aug 2006

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

Virtual Competition

by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke · 30 Nov 2016

Economic Dignity

by Gene Sperling · 14 Sep 2020 · 667pp · 149,811 words

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 26 Mar 2013 · 316pp · 94,886 words

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception

by George A. Akerlof, Robert J. Shiller and Stanley B Resor Professor Of Economics Robert J Shiller · 21 Sep 2015 · 274pp · 93,758 words

Think Like a Freak

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 May 2014 · 240pp · 65,363 words

Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World

by David Easley and Jon Kleinberg · 15 Nov 2010 · 1,535pp · 337,071 words

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 14 Sep 2017 · 520pp · 153,517 words

The Intelligent Investor (Collins Business Essentials)

by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig · 1 Jan 1949 · 670pp · 194,502 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth

by Stuart Ritchie · 20 Jul 2020

On the Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did to Me and How It Drives America Insane

by Emily Guendelsberger · 15 Jul 2019 · 382pp · 114,537 words

Moneyball

by Michael Lewis · 1 Jan 2003 · 316pp · 105,384 words

Reinventing Capitalism in the Age of Big Data

by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Thomas Ramge · 27 Feb 2018 · 267pp · 72,552 words

Brave New Work: Are You Ready to Reinvent Your Organization?

by Aaron Dignan · 1 Feb 2019 · 309pp · 81,975 words

People Powered: How Communities Can Supercharge Your Business, Brand, and Teams

by Jono Bacon · 12 Nov 2019 · 302pp · 73,946 words

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot

by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy M. Weinstein · 6 Sep 2021

The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing

by Lisa Gansky · 14 Oct 2010 · 215pp · 55,212 words

Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less

by Greg McKeown · 14 Apr 2014 · 202pp · 62,199 words

Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

by Bruce C. N. Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul D. Sonkin and Michael van Biema · 26 Jan 2004 · 306pp · 97,211 words

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

What to Think About Machines That Think: Today's Leading Thinkers on the Age of Machine Intelligence

by John Brockman · 5 Oct 2015 · 481pp · 125,946 words

An Elegant Puzzle: Systems of Engineering Management

by Will Larson · 19 May 2019 · 227pp · 63,186 words

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

by Nir Eyal · 26 Dec 2013 · 199pp · 43,653 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead

by Sheryl Sandberg · 11 Mar 2013 · 241pp · 78,508 words

Big Mistakes: The Best Investors and Their Worst Investments

by Michael Batnick · 21 May 2018 · 198pp · 53,264 words

Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge From Small Discoveries

by Peter Sims · 18 Apr 2011 · 207pp · 57,959 words

How to Predict the Unpredictable

by William Poundstone · 267pp · 71,941 words

What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets

by Michael Sandel · 26 Apr 2012 · 231pp · 70,274 words

Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America

by Cass R. Sunstein · 6 Mar 2018 · 434pp · 117,327 words

Empirical Market Microstructure: The Institutions, Economics and Econometrics of Securities Trading

by Joel Hasbrouck · 4 Jan 2007 · 209pp · 13,138 words

Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change From the Cult of Technology

by Kentaro Toyama · 25 May 2015 · 494pp · 116,739 words

Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy

by Robert H. Frank · 31 Mar 2016 · 190pp · 53,409 words

The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life

by Robert Wright · 1 Jan 1994 · 604pp · 161,455 words

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by Vito Tanzi · 28 Dec 2017

To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others

by Daniel H. Pink · 1 Dec 2012 · 243pp · 61,237 words

The Wisdom of Crowds

by James Surowiecki · 1 Jan 2004 · 326pp · 106,053 words

Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked

by Adam L. Alter · 15 Feb 2017 · 331pp · 96,989 words

Financial Statement Analysis: A Practitioner's Guide

by Martin S. Fridson and Fernando Alvarez · 31 May 2011

The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy

by Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz · 4 Nov 2016 · 374pp · 97,288 words

Raw Data Is an Oxymoron

by Lisa Gitelman · 25 Jan 2013

We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves

by John Cheney-Lippold · 1 May 2017 · 420pp · 100,811 words

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, From Home Renovations to Space Exploration

by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner · 16 Feb 2023 · 353pp · 97,029 words

Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny

by Robert Wright · 28 Dec 2010

The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 14 Jul 2012 · 299pp · 92,782 words

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

No Slack: The Financial Lives of Low-Income Americans

by Michael S. Barr · 20 Mar 2012

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

by Lawrence Lessig · 14 Jul 2001 · 494pp · 142,285 words

Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined

by Lasse Heje Pedersen · 12 Apr 2015 · 504pp · 139,137 words

The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities

by John J. Mearsheimer · 24 Sep 2018 · 443pp · 125,510 words

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by Robert Higgs and Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. · 15 Jan 1987

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by Ray Kurzweil · 25 Jun 2024

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds

by Michael Lewis · 6 Dec 2016 · 336pp · 113,519 words

Capital Ideas Evolving

by Peter L. Bernstein · 3 May 2007

The Acquirer's Multiple: How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 13 Oct 2017 · 120pp · 33,892 words

The Behavioral Investor

by Daniel Crosby · 15 Feb 2018 · 249pp · 77,342 words

Inside the Nudge Unit: How Small Changes Can Make a Big Difference

by David Halpern · 26 Aug 2015 · 387pp · 120,155 words

The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less

by Barry Schwartz · 1 Jan 2004 · 241pp · 75,516 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

The Loop: How Technology Is Creating a World Without Choices and How to Fight Back

by Jacob Ward · 25 Jan 2022 · 292pp · 94,660 words

The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio

by William J. Bernstein · 26 Apr 2002 · 407pp · 114,478 words

A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market

by John Allen Paulos · 1 Jan 2003 · 295pp · 66,824 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets

by Brett Scott · 4 Jul 2022 · 308pp · 85,850 words

Licence to be Bad

by Jonathan Aldred · 5 Jun 2019 · 453pp · 111,010 words

Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess

by Robert H. Frank · 15 Jan 1999 · 416pp · 112,159 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

The Confidence Game: The Psychology of the Con and Why We Fall for It Every Time

by Maria Konnikova · 28 Jan 2016 · 384pp · 118,572 words

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by Phil Thornton · 7 May 2014

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

The Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties

by Christopher Caldwell · 21 Jan 2020 · 450pp · 113,173 words

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 20 Feb 2018 · 306pp · 82,765 words

Mindwise: Why We Misunderstand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want

by Nicholas Epley · 11 Feb 2014 · 369pp · 90,630 words

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall · 19 Mar 2019 · 393pp · 115,217 words

Toward Rational Exuberance: The Evolution of the Modern Stock Market

by B. Mark Smith · 1 Jan 2001 · 403pp · 119,206 words

The Knowledge Illusion

by Steven Sloman · 10 Feb 2017 · 313pp · 91,098 words

Grouped: How Small Groups of Friends Are the Key to Influence on the Social Web

by Paul Adams · 1 Nov 2011 · 123pp · 32,382 words

The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class

by Guy Standing · 27 Feb 2011 · 209pp · 89,619 words

The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism

by Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias · 19 Aug 2019 · 458pp · 116,832 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing

by Burton G. Malkiel · 10 Jan 2011 · 416pp · 118,592 words

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

by Steven Pinker · 14 Oct 2021 · 533pp · 125,495 words

The Panic Virus: The True Story Behind the Vaccine-Autism Controversy

by Seth Mnookin · 3 Jan 2012 · 566pp · 153,259 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

The Googlization of Everything:

by Siva Vaidhyanathan · 1 Jan 2010 · 281pp · 95,852 words

The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Doto Get More of It

by Kelly McGonigal · 1 Dec 2011 · 354pp · 91,875 words

Intertwingled: Information Changes Everything

by Peter Morville · 14 May 2014 · 165pp · 50,798 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

Mine!: How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives

by Michael A. Heller and James Salzman · 2 Mar 2021 · 332pp · 100,245 words

Willful: How We Choose What We Do

by Richard Robb · 12 Nov 2019 · 202pp · 58,823 words

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom

by Tony Robbins · 18 Nov 2014 · 825pp · 228,141 words

Gene Eating: The Science of Obesity and the Truth About Dieting

by Giles Yeo · 3 Jun 2019 · 351pp · 112,079 words

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by David G. Blanchflower · 12 Apr 2021 · 566pp · 160,453 words

The Social Life of Money

by Nigel Dodd · 14 May 2014 · 700pp · 201,953 words

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing (Eleventh Edition)

by Burton G. Malkiel · 5 Jan 2015 · 482pp · 121,672 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

Foolproof: Why Safety Can Be Dangerous and How Danger Makes Us Safe

by Greg Ip · 12 Oct 2015 · 309pp · 95,495 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

The Intelligent Asset Allocator: How to Build Your Portfolio to Maximize Returns and Minimize Risk

by William J. Bernstein · 12 Oct 2000

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

Eat People: And Other Unapologetic Rules for Game-Changing Entrepreneurs

by Andy Kessler · 1 Feb 2011 · 272pp · 64,626 words

The Fifth Domain: Defending Our Country, Our Companies, and Ourselves in the Age of Cyber Threats

by Richard A. Clarke and Robert K. Knake · 15 Jul 2019 · 409pp · 112,055 words

The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being

by William Davies · 11 May 2015 · 317pp · 87,566 words

The Fissured Workplace

by David Weil · 17 Feb 2014 · 518pp · 147,036 words

Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side

by Howard Marks · 30 Sep 2018 · 302pp · 84,428 words

The Formula: How Algorithms Solve All Our Problems-And Create More

by Luke Dormehl · 4 Nov 2014 · 268pp · 75,850 words

The Choice Factory: 25 Behavioural Biases That Influence What We Buy

by Richard Shotton · 12 Feb 2018 · 184pp · 46,395 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

The Revolution That Wasn't: GameStop, Reddit, and the Fleecing of Small Investors

by Spencer Jakab · 1 Feb 2022 · 420pp · 94,064 words

Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World

by J. Doyne Farmer · 24 Apr 2024 · 406pp · 114,438 words

The Soul of Wealth

by Daniel Crosby · 19 Sep 2024 · 229pp · 73,085 words

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 2002 · 901pp · 234,905 words

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker · 24 Sep 2012 · 1,351pp · 385,579 words

The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic at Work and at Home

by Dan Ariely · 31 May 2010 · 324pp · 93,175 words

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

Vassal State

by Angus Hanton · 25 Mar 2024 · 277pp · 81,718 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

Smart Money: How High-Stakes Financial Innovation Is Reshaping Our WorldÑFor the Better

by Andrew Palmer · 13 Apr 2015 · 280pp · 79,029 words

The Self-Made Billionaire Effect: How Extreme Producers Create Massive Value

by John Sviokla and Mitch Cohen · 30 Dec 2014 · 252pp · 70,424 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control

by Stuart Russell · 7 Oct 2019 · 416pp · 112,268 words

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by Tim Harford · 1 Jan 2008 · 250pp · 88,762 words

SEDATED: How Modern Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis

by James. Davies · 15 Nov 2021 · 307pp · 88,085 words

The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution

by Gregory Zuckerman · 5 Nov 2019 · 407pp · 104,622 words

Fancy Bear Goes Phishing: The Dark History of the Information Age, in Five Extraordinary Hacks

by Scott J. Shapiro · 523pp · 154,042 words

More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite

by Sebastian Mallaby · 9 Jun 2010 · 584pp · 187,436 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

Walk Away

by Douglas E. French · 1 Mar 2011 · 93pp · 24,584 words

The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50

by Jonathan Rauch · 30 Apr 2018 · 277pp · 79,360 words

Building Secure and Reliable Systems: Best Practices for Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Systems

by Heather Adkins, Betsy Beyer, Paul Blankinship, Ana Oprea, Piotr Lewandowski and Adam Stubblefield · 29 Mar 2020 · 1,380pp · 190,710 words

The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics

by Tim Harford · 2 Feb 2021 · 428pp · 103,544 words

This Will Make You Smarter: 150 New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking

by John Brockman · 14 Feb 2012 · 416pp · 106,582 words

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by Scott E. Page · 27 Nov 2018 · 543pp · 153,550 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Human Diversity: The Biology of Gender, Race, and Class

by Charles Murray · 28 Jan 2020 · 741pp · 199,502 words

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 8 Oct 2017 · 322pp · 87,181 words

The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity

by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott · 1 Jun 2016 · 344pp · 94,332 words

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by Gabriel Weinberg and Lauren McCann · 17 Jun 2019

Chaos Kings: How Wall Street Traders Make Billions in the New Age of Crisis

by Scott Patterson · 5 Jun 2023 · 289pp · 95,046 words

Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation

by Tyler Cowen · 11 Sep 2013 · 291pp · 81,703 words

Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty

by Peter Singer · 3 Mar 2009 · 190pp · 61,970 words

Red-Blooded Risk: The Secret History of Wall Street

by Aaron Brown and Eric Kim · 10 Oct 2011 · 483pp · 141,836 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Beyond Diversification: What Every Investor Needs to Know About Asset Allocation

by Sebastien Page · 4 Nov 2020 · 367pp · 97,136 words

The Hidden Half: How the World Conceals Its Secrets

by Michael Blastland · 3 Apr 2019 · 290pp · 82,871 words

Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction

by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner · 14 Sep 2015 · 317pp · 100,414 words

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by David Hale and Lyric Hughes Hale · 23 May 2011 · 397pp · 112,034 words

Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming

by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby · 22 Nov 2013 · 165pp · 45,397 words

A Wealth of Common Sense: Why Simplicity Trumps Complexity in Any Investment Plan

by Ben Carlson · 14 May 2015 · 232pp · 70,835 words

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by Douglas Rushkoff · 7 Sep 2022 · 205pp · 61,903 words

Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us About Economics and Life

by Alan B. Krueger · 3 Jun 2019

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

Where Good Ideas Come from: The Natural History of Innovation

by Steven Johnson · 5 Oct 2010 · 298pp · 81,200 words

Stuffocation

by James Wallman · 6 Dec 2013 · 296pp · 82,501 words

Hello, Habits

by Fumio Sasaki · 6 Nov 2020 · 195pp · 60,471 words

Why Startups Fail: A New Roadmap for Entrepreneurial Success

by Tom Eisenmann · 29 Mar 2021 · 387pp · 106,753 words

This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World

by Yancey Strickler · 29 Oct 2019 · 254pp · 61,387 words

Money Moments: Simple Steps to Financial Well-Being

by Jason Butler · 22 Nov 2017 · 139pp · 33,246 words

Quantitative Value: A Practitioner's Guide to Automating Intelligent Investment and Eliminating Behavioral Errors

by Wesley R. Gray and Tobias E. Carlisle · 29 Nov 2012 · 263pp · 75,455 words

Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking

by Matthew Syed · 9 Sep 2019 · 280pp · 76,638 words

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

SuperFreakonomics

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 19 Oct 2009 · 302pp · 83,116 words

The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution

by Jonathan Eig · 12 Oct 2014 · 420pp · 121,881 words

Messy: The Power of Disorder to Transform Our Lives

by Tim Harford · 3 Oct 2016 · 349pp · 95,972 words

All About Asset Allocation, Second Edition

by Richard Ferri · 11 Jul 2010

They Don't Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy

by Lawrence Lessig · 5 Nov 2019 · 404pp · 115,108 words

Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change

by George Marshall · 18 Aug 2014 · 298pp · 85,386 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

The Future of the Internet: And How to Stop It

by Jonathan Zittrain · 27 May 2009 · 629pp · 142,393 words

Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 10 Feb 2010 · 307pp · 94,069 words

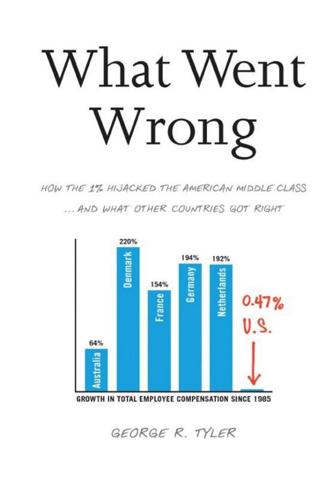

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges and Leaderboards

by Yu-Kai Chou · 13 Apr 2015 · 420pp · 130,503 words

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion

by Jonathan Haidt · 13 Mar 2012 · 539pp · 139,378 words