King of Capital: The Remarkable Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Steve Schwarzman and Blackstone

by

David Carey

Published 7 Feb 2012

By then, the buzz had been building for weeks. Stephen Schwarzman, cofounder of the Blackstone Group, the world’s largest private equity firm, was about to turn sixty and was planning a fête. The financier’s lavish holiday parties were already well known in Manhattan’s moneyed circles. One year Schwarzman and his wife decorated their twenty-four-room, two-floor spread in Park Avenue’s toniest apartment building to resemble Schwarzman’s favorite spot in St. Tropez, near their summer home on the French Riviera. For his birthday, he decided to top that, taking over the Park Avenue Armory, a fortified brick edifice that occupies a full square block amid the metropolis’s most expensive addresses.

…

The backlash against the buyout boom of the 2000s began in Europe, where a German cabinet member publicly branded private equity and hedge funds “locusts” and British unions lobbied to rein in these takeovers. By the time the starry canopy was being strung in the Park Avenue Armory for Schwarzman’s birthday party, the blowback had come Stateside. American unions feared the new wave of LBOs would lead to job losses, and the enormous profits being generated by private equity and hedge funds had caught the eye of Congress. “I told him that I thought his party was a very bad idea before he had his party,” says Henry Silverman, the former Blackstone partner who went on to head Cendant. Proposals were already circulating to jack up taxes on investment fund managers, Silverman knew, and the party could only fan the political flames.

…

Beneath an immense portrait of the financier—also a replica of one hanging in his apartment—the headliners, singer Rod Stewart and comic Martin Short, strutted and joked into the late hours. Schwarzman had chosen the armory, Short quipped, because it was more intimate than his apartment. Stewart alone was known to charge $1 million for such appearances. The $3 million gala was a self-coronation for the brash new king of a new Gilded Age, an era when markets were flush and crazy wealth saturated Wall Street and especially the private equity realm, where Schwarzman held sway as the CEO of Blackstone Group. As soon became clear, the birthday affair was merely a warm-up for a more extravagant coming-out bash: Blackstone’s initial public offering.

The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything

by

Jason Kelly

Published 10 Sep 2012

That’s the simple reason for the birthday party.”7 Much to Schwarzman and Blackstone’s public relations team’s chagrin, the party has become an emblem for excess, shorthand for what’s wrong with private equity and Wall Street and its highest-profile and best-paid practitioners. It is difficult to have a conversation about the LBO boom, or the perception of private equity, without someone uttering the phrase “the birthday party,” with something ranging from a smirk to a scowl. Most people don’t even mention Schwarzman’s name, but the details—a black-tie affair at the Park Avenue Armory in midtown Manhattan, replicating part of his apartment in the cavernous space, including a portrait of himself; the performances by Rod Stewart, Patti LaBelle, and Marvin Hamlisch—all are well-documented.

…

The football stadium at the school is named after him.5 Since then he has built a sprawling global empire with more than $190 billion in assets from a $400,000 investment, in a matter of a couple of decades. He lives in a Park Avenue apartment once occupied by Rockefellers. He has achieved enough wealth to have the nation’s most famous library—the Main Branch of the New York Public Library—renamed the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building in honor of his contribution of $100 million toward the building’s renovation and expansion. Companies Blackstone owns directly, as well as insights gleaned from real estate, credit, and equity markets by its various arms, give the firm the potential to analyze the global economy as well as just about anyone.

…

Bain also has opted to pursue growth by growing new businesses organically and with homegrown talent rather than by buying them. At Blackstone, Schwarzman and James were building a different type of firm, and going public was a means not only to transition the founders, but to give the firm a currency to expand the business rapidly. While a Blackstone IPO may have been inevitable, its completion was far from certain in 2007. When the time came to actually sell the shares to the public, in the middle of 2007, Schwarzman knew he had to hurry. The year had been going exceedingly well. In addition to the birthday party, he’d been on the cover of Fortune (“Wall Street’s Man of the Moment”)2 and pulled off what was for at least a few weeks the biggest leveraged buyout in history (Equity Office Properties).

Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy

by

Robert H. Frank

Published 31 Mar 2016

The problem is compounded by the fact that disdain for luck is often greatest in those who possess the most power to influence political decisions about the tax code. Consider Stephen Schwarzman, the CEO of Blackstone, the fabled private-equity firm. Schwarzman lives well. He made the news in 2007 when he staged a $3-million sixtieth birthday party for himself and several hundred of his closest friends at the Armory on Park Avenue. According to Gawker’s coverage of the event, “Rod Stewart was paid $1 million to perform for the assembled guests; Patti LaBelle sang ‘Happy Birthday.’ And the room was designed to replicate Schwarzman’s $40 million co-op at 740 Park Avenue.”18 But Schwarzman believes the government is taking far too much of “his” money.

…

And the room was designed to replicate Schwarzman’s $40 million co-op at 740 Park Avenue.”18 But Schwarzman believes the government is taking far too much of “his” money. James Surowiecki, an economics writer for the New Yorker, offered these thoughts on the Blackstone executive: The past few years have been very good to Stephen Schwarzman…. His industry, which relies on borrowed money, has benefitted from low interest rates, and the stock-market boom has given his firm great opportunities to cash out investments. Schwarzman is now worth more than ten billion dollars. You wouldn’t think he’d have much to complain about. But, to hear him tell it, he’s beset by a meddlesome, tax-happy government and a whiny, envious populace. He recently grumbled that the U.S. middle class has taken to “blaming wealthy people” for its problems.

…

., 4 Romney, Mitt, 84 RJR Nabisco, 51 Rosen, Sherwin, 46 S&P 500, 53 sadism, 122 Safer, Morley, 137 Sagan, Carl, 67 sales tax, 158, 159 Salomon Brothers, xiii same-sex marriage, 106–8 Sams, Jack, 35 Samuelson, Paul, 71 Saracini, Kirsten, 135 SATs, 32, 88 Scandinavian countries, 20 Schwartz, Barry, 48 Schwarzman, Stephen, 103, 104, 106 Scrabble, 82 Seattle Computer Products, 35 Seles, Monica, 46 self-control problems, 75–77 self-interest, 130 Seligman, Martin, 102 shipping costs, 42 60 Minutes, 135 skill premium, 53 Slate, 117 Smith, Adam, 52, 115, 132 Smith College, 58 Sony, 44 Soviet Union collapse, 107 Spanish National Lottery, 69 Stanford University, xv, 70 starve the beast strategy, 97 Stein, Herb, 105 Stewart, Rod, 103 student debt, 87 Success Equation, The, 69 sudden cardiac death/arrest, 2, 147 Supreme Court campaign finance rulings, 104 Surowiecki, James, 103 Sutton, Willie, 98 Switzerland, 20 tailwinds, 80, 81 Taleb, Nassim Nicholas, 72 Tangier, 87 tariff barriers, 42 tax accounting, 9, 43 tax resistance, 107 taxable consumption, 118, 159 taxation as theft, 96, 97 Thaler, Richard, 177 Tierney, John, 75 toil index, 113, 114 top marginal tax rates, declining, 88, 89 track and field records, 63, 64 Transparency International, 19 Tudor, Fredric, 36, 37 Turbo Tax, 10 Tversky, Amos, 70 Uffizi Gallery, 22 ultimatum game, 93–95 University of California at Berkeley, xv, 25, 137 University of Wisconsin, 25 Unlimited Savings Allowance Tax, 126 Valenti, Aurora, 19 value-added tax, 158, 159 Varney, Stuart, 3, 4, 7 VHS, 44, 45 Viard, Alan, 127 Wall Street, xiii Warren, Elizabeth, 12 waste, defined, 16 Watts, Duncan, 22, 23, 30, 31 Wealth of Nations, 52, 132 wedding costs, 14, 110, 111 Wedding March, 106 Weightman, Gavin, 37 White, E.

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by

Chrystia Freeland

Published 11 Oct 2012

” — On February 13, 2007, almost exactly 120 years after the Martin ball, a leader of a new, ascendant American plutocracy hosted another epoch-making gala, also on Park Avenue, this time at the Armory, less than a mile directly north of the grand hotel rooms where the Martins and their friends had frolicked. The guests at Steve Schwarzman’s sixtieth-birthday bash didn’t come in costume, and they arrived at eight p.m., not ten thirty p.m., but in many other ways his celebration echoed New York’s most famous nineteenth-century entertainment. The ladies were bejeweled, many of the guests were moguls (Mike Bloomberg, John Thain, Howard Stringer), and the entertainment was lavish—its highlight was a half-hour live performance by Rod Stewart, for which he was reportedly paid $1 million.

…

Barton, a Canadian who lives in London but whose secretary is based in Singapore, was due to see Steve Schwarzman, the private equity investor, later that day. “The last time I saw Steve was in China,” where Blackstone had held a partners meeting the previous fall, Barton recalled. Barton himself was traveling to Chile later in the week, and then on to São Paolo, where McKinsey was holding a board meeting. Schwarzman, meanwhile, was about to move his primary residence to Paris for six months (he already owned one home in that country, in the south of France, of course), the better to oversee what he believed would be significant investment opportunities in Europe and Asia. Schwarzman spends about half his time traveling.

…

Two other former Obama backers on Wall Street—both claim to have been on Rahm Emanuel’s speed dial list—recently told me that the president is “antibusiness”; one went so far as to worry that Obama is “a socialist.” In some cases, this sense of siege is almost literal. In the summer of 2010, for example, Blackstone’s Schwarzman caused an uproar when he said an Obama proposal to raise taxes on private equity firm compensation—by treating carried interest as ordinary income—was “like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939.” However histrionic his metaphors, Schwarzman (who later apologized for the remark) is a Republican, so his antipathy for the current administration is no surprise. What is perhaps more surprising is the degree to which even former Obama supporters in the financial industry have turned against the president and his party.

The Quants

by

Scott Patterson

Published 2 Feb 2010

The Tuesday after the Fortress IPO, Stephen Schwarzman, cofounder and chief executive of private equity powerhouse Blackstone Group, threw himself a lavish sixtieth-birthday bash in midtown Manhattan. Blackstone had just completed its $39 billion buyout of Equity Office Properties, the largest leveraged buyout in history, and Schwarzman was in a festive mood. The celebrity-studded, paparazzi-thick blowout smacked of the grandiose robber baron excesses of the Gilded Age, and it marked the crest of a decades-long boom of vast riches on Wall Street—though few knew it at the time. The location was the Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue.

…

The guest list at Schwarzman’s fete included Colin Powell and New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, along with Barbara Walters and Donald Trump. Upon entering the orchid-festooned armory to a march played by a brass band, ushered by smiling children in military garb, visitors were treated to a full-length portrait of their host by the British painter Andrew Festing, president of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. The dinner included lobster, filet mignon, and baked Alaska, topped off with potables such as a 2004 Louis Jadot Chassagne-Montrachet. Comedian Martin Short emceed. Rod Stewart performed. Patti LaBelle and the Abyssinian Baptist Church choir sang Schwarzman’s praises, along with “Happy Birthday.”

…

Rod Stewart performed. Patti LaBelle and the Abyssinian Baptist Church choir sang Schwarzman’s praises, along with “Happy Birthday.” On its cover, Fortune magazine declared Schwarzman “Wall Street’s Man of the Moment.” High-society tongues were still wagging about the party a few months later, when Schwarzman gave himself another eye-popping gift. In June, Blackstone raised $4.6 billion in an IPO that valued the company’s stock at $31 a share. Schwarzman, who was known to shell out $3,000 a weekend on meals, including $400 on stone crabs ($40 per claw), personally pocketed nearly $1 billion. At the time of the offering, his stake in the firm was valued at $7.8 billion.

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by

Satyajit Das

Published 14 Oct 2011

Offered at $18.50 each, the shares rose 68 percent on listing to $31, trading at 40 times their historical earnings. It was private equity’s Netscape moment, reminiscent of when the Internet neophyte floated its shares to the public and the price skyrocketed. Blackstone, KKR, and others rushed to cash in on the gold rush. Schwarzman’s $5 million 60th birthday celebration, held in February 2007, was another sign of impending doom. The venue—the Armory—was decorated to replicate Schwarzman’s Park Avenue apartment, featuring a large portrait of the birthday boy. Children dressed in military regalia acted as ushers, and comedian Martin Short was master of ceremonies. Guests, including Colin Powell and New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, dined on lobster and baked Alaska, whilst imbibing fine wines.

…

When Steve Schwarzman’s biography with all the dollar signs is posted on the web site none of us will like the furore that results—and that’s even if you like Rod Stewart.”13 In June 2007, Blackstone’s share offering was priced at $31 per share listed, trading upon listing in the stock exchange at around $37. The Chinese government invested $3 billion. Schwarzman cashed out stock worth over $650 million. His remaining 24 percent stake was valued at almost $8 billion, placing him near Rupert Murdoch and Steve Jobs on the list of richest people. In 2006, Schwarzman earned $398 million, around double the combined pay of the five largest American investment bank CEOs.

…

Patti LaBelle led the Abyssinian Baptist Church choir in a song especially composed in honor of Schwarzman. Rod Stewart, the sexagenarian British rock star, performed his hits including Maggie May and Do’ya Think I’m Sexy. In 2002, David Bonderman, co-founder of TPG, had staged a lavish $7 million party to celebrate his 60th birthday party for hundreds of his “closest” friends. Held at the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas, the party featured entertainment from the Rolling Stones and Robin Williams. Carlyle’s David Rubinstein was unimpressed: “We have all wanted to be private—at least until now. When Steve Schwarzman’s biography with all the dollar signs is posted on the web site none of us will like the furore that results—and that’s even if you like Rod Stewart.”13 In June 2007, Blackstone’s share offering was priced at $31 per share listed, trading upon listing in the stock exchange at around $37.

All the Money in the World

by

Peter W. Bernstein

Published 17 Dec 2008

Forbes flew in the approximately eight hundred guests, including Elizabeth Taylor and Henry Kissinger, on three airplanes—a 747, a DC-8, and the Concorde—for the three days of celebrating. The almost $2.5 million tab42 for the party included paying more than three hundred horsemen in Moroccan costume and six hundred drummers, belly dancers, and jugglers. More recently, financier Stephen Schwarzman spent43 more than $3 million on his sixtieth birthday party at the Park Avenue Armory. The party, for about six hundred guests, included performances by rock crooner Rod Stewart and soul singer Patti LaBelle. It was as much the talk of the town as Alva Vanderbilt’s lavish parties had been in the 1890s. (Her most famous party44 reputedly cost as much as $250,000, or around $5.5 million today.)

…

The 1980s are no longer the golden age81 of the LBO; in fact, fifteen of the world’s twenty largest leveraged buyouts occurred in an eighteen-month period beginning in the second half of 2005. And the new private equity boom is fattening the pockets of many of its veteran practitioners: The fortune of Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman, for example, increased by $1 billion from 2005 to 2006, and is likely to soar much higher after a planned public offering in 2007. “Private equity is a huge force—nothing is out of range for it. Nothing,” says venture capitalist Dick Kramlich. But the newly minted financiers, ensconced in their Park Avenue triplexes and Greenwich mansions, would do well to bear in mind the admonition of Henry Kravis, delivered in an early 2007 interview with the Wall Street Journal: “Any fool can buy a company,”82 he says.

…

Theodore Forstmann and his brother, Nicholas, started the buyout firm Forstmann Little & Company in 1978. Peter G. Peterson14, commerce secretary in the Nixon administration, and Stephen A. Schwarzman (like Peterson, an alumnus of Lehman Brothers, an old-line Wall Street firm) started Blackstone Group in 1985. Forstmann’s niche was friendly buyouts; Blackstone, buttressed by Peterson’s connections and Schwarzman’s deal-making drive, became more of a small investment bank. But by getting in early on the LBO craze, they also became renowned, and Forstmann and Schwarzman landed on the Forbes 400 list, as well. * * * The really big money men (and one woman)… The financial business has been minting money since the Forbes list began in 1982.

House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street

by

William D. Cohan

Published 15 Nov 2009

Goldman had extracted its pound of flesh by insisting on the ability to get out of the agreement “at the first hint of trouble.” That night, ironically, Steve Schwarzman, one of the two founders of the Blackstone Group, gave himself a boffo $4 million sixtieth-birthday party at the Armory on Park Avenue for 350 of Manhattan's glitterati. Martin Short emceed. Rod Stewart and Patti LaBelle sang. The menu included lobster, baked Alaska, and a 2004 Louis Jadot Chassagne-Montrachet. Cayne was there. “The festivities served as a coronation of sorts for Mr. Schwarzman, a billionaire several times over, an active Republican donor and chairman of the Kennedy Center in Washington whose influence reaches deep into the worlds of finance, politics and the arts,” the Times reported afterward.

…

The price must be a typo, the consensus seemed to be, since surely a company that fourteen months earlier had been trading at $172.69 per share could not now be worth so little. Steve Schwarzman, the head of The Blackstone Group, had been vacationing with his wife in St. Barts, the exclusive Caribbean island. He had spoken to Schwartz on Friday for about thirty minutes to see if Schwartz needed Blackstone's help and was told, “We're fine. We're good. We don't need any help.” That Sunday evening, he had just sat down for dinner with fellow Philadelphia billionaire Ron Perelman on Perelman's 188-foot yacht, the Ultima III, when the news paraded across his Black-Berry that Bear Stearns had been sold for $2 a share. “It must be $20,” Schwarzman and Perelman said to each other.

…

That night, Warren Spector was at a private dinner in Washington with other senior Wall Street executives to meet presidential candidate Senator Barack Obama. Spector introduced himself as working for Bear Stearns, “the current scourge of Wall Street.” At the same time that Spector was in Washington, Steve Schwarzman's Blackstone Group priced its highly anticipated $4.75 billion IPO at $31 per share. The offering, a huge success from Blackstone's perspective, briefly made Schwarzman worth close to $8 billion. The two lead managers of the deal, Morgan Stanley and Citigroup, hoovered up around $100 million of the $202 million in underwriting fees. (Bear Stearns was a co-manager on the deal.) By the next afternoon, Spector was back at his office in New York spending hours on the phone with other Wall Street executives.

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by

James Rickards

Published 7 Apr 2014

Another technique China uses to disguise its market intelligence operations was reported on May 20, 2007, in The New York Times when Andrew Ross Sorkin disclosed that the China Investment Corporation (CIC), another sovereign wealth fund, had agreed to purchase $3 billion of stock in Blackstone Group, the powerful and secretive U.S.-based private equity firm. Blackstone Group was cofounded by former Nixon administration senior official Peter G. Peterson, later chairman of both the Council on Foreign Relations and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The other Blackstone cofounder, Stephen A. Schwarzman, is a multibillionaire who became notorious for his sixtieth birthday party held at the New York Park Avenue Armory on February 13, 2007, just a few months before Blackstone’s sale. That party included a thirty-minute performance by Rod Stewart, for which the singer was reportedly paid $1 million.

…

the Chinese Investment Corporation (CIC) . . . : Andrew Ross Sorkin and David Barboza, “China to Buy $3 Billion Stake in Blackstone,” New York Times, May 20, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/20/business/worldbusiness/20cnd-yuan.html?pagewanted=print. notorious for his sixtieth birthday party . . . : James B. Stewart, “The Birthday Party,” New Yorker, February 11, 2008, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/02/11/080211fa_fact_stewart. “I want war, not a series . . .”: Quoted in Andrew Clark, “The Guardian Profile: Stephen Schwarzman,” Guardian, June 15, 2007, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/jun/15/4. “to put its vast reserves . . .”: Sorkin and Barboza, “China to Buy.”

…

The Chinese investment due diligence teams get a look at confidential deal target information, even on deals that do not ultimately get done. The $3 billion sale price may seem like a lot of money to Schwarzman, but it is only one-tenth of one percent of China’s reserves, the equivalent of dropping a dime when you have a hundred-dollar bill. China’s penetration of Schwarzman and Blackstone is a significant step in its advance toward East Asian hegemony and a possible confrontation with the United States. Of course, information channels are a two-way street, and firms such as Blackstone do assist the U.S. intelligence community with insights on Chinese capabilities and intentions. The United States is not the only potential Chinese financial warfare target.

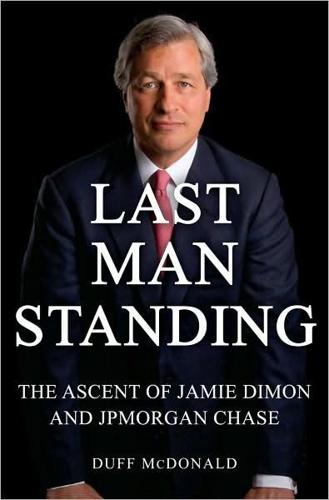

Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JPMorgan Chase

by

Duff McDonald

Published 5 Oct 2009

Friends and colleagues noticed that Dimon basically stopped making an effort to remain friendly with Weill after the book’s release. While always respectful, he just doesn’t go out of his way anymore. • • • Although he rarely appears in the social pages, Dimon did attend the $3 million birthday fete that the private equity kingpin Stephen Schwarzman threw for himself at the Park Avenue Armory in February 2007. The bash was seized on as a symbol of the new gilded age—Rod Stewart was paid $1 million to play for half an hour—and the city’s financial elite turned out in full force to eat lobster and baked Alaska and drink 2004 Louis Jadot Chassagne-Montrachet. Along with Dimon were Goldman Sachs’s CEO Lloyd Blankfein, Merrill Lynch’s Stan O’Neal, Bear Stearns’ Jimmy Cayne, and Lazard’s Bruce Wasserstein.

…

The CEOs of most of the top Wall Street firms were in attendance—Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs; Ken Chenault of American Express; Dimon; Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers; Bob Rubin, chairman of the executive committee at Citigroup; and John Thain of Merrill Lynch. A few kingpins of private equity and hedge funds were also there, including Ken Griffin of Citadel Investment Group, Bruce Kovner of Caxton Associates, and Steve Schwarzman of the Blackstone Group. There was no one representing Bear Stearns in the room; Schwartz had not even been invited. On the morning of Wednesday, March 12, Schwartz appeared on CNBC in an effort to deflect growing concerns about the company. “Some people could speculate that Bear Stearns might have problems, since we’re a significant player in the mortgage business,” he said to the anchor, David Faber.

…

He has also called for a systematic regulator that can anticipate problems in the system rather than merely respond to them. Even though Dimon, as a college student, wrote that admiring letter to Milton Friedman, the king of the laissez-faire economists, he also values the lessons of John Maynard Keynes and Keynes’s argument in favor of adult supervision in the markets. In October 2008, Blackstone’s chief, Steve Schwarzman, embarked on a campaign to have so-called “mark to market” accounting rules changed. The rules, he (and others) complained, meant that companies with deteriorating asset values were constantly forced to mark down their balance sheet values; this entailed having to raise capital by selling more assets, which put further downward pressure on those asset values, which … a vicious circle.