Seaside, Florida

description: unincorporated master-planned community in Walton County, Florida

17 results

The Year Without Pants: Wordpress.com and the Future of Work

by

Scott Berkun

Published 9 Sep 2013

See Working remotely Remy, Martin Ressler, Cari Results: culture emphasizing; judgment of ability determined by Results Only Work Environment (ROWE) Retreats, contrasted to Automattic company meeting Revenue: Automattic cultural aversion to; how WordPress.com makes; Mullenweg's restraint in chasing; WordPress.com store and Roebling, Washington Ross, Hanni Rosso, Sara S Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de San Francisco: author's October visit to; Automattic headquarters in; Automatticians living in; mini-team meet-up in; town hall meeting broadcast from Schedules: of Automatticians; determined by marketing; lack of; spreadsheets for Schneider, Toni: about; co-hosted San Francisco town hall meeting; on continuous deployment; joined as CEO of Automattic; lived in San Francisco; on management as support role; met regularly with Mullenweg; split Automattic employees into teams Scott, Joseph SCRUM Seaside, Florida. See Company meeting (Seaside, Florida) Self-host builds Self-test builds Self-toast builds Shipping: cathedral-vs. bazaar-style thinking about; incomplete work; management's emphasis on; by Microsoft Internet Explorer team; two-week work cycle's impact on; at WordPress.com Shopcraft as Soulcraft (Crawford) Shreve, Justin Skelton, Andy Skype: advantage of working in; Automattic communication via; information known about coworkers when using; manually entering names into; meetings to review spreadsheets; private chats on Solomon, Evan The Soul of a New Machine(Kidder) Sphere Spittle, Andrew Spreadsheets, for schedules Stallman, Richard Stats plug-in Stop Online Piracy Act Subscription Notification feature Succession planning Support: kept from infringing upon creativity Sutton, Bob Sutton, Hew SXSW, Jetpack launch at T Team Akismit Team Data Team Happiness: author's training work with; bug management by; defined; monitoring work of; tickets as focus of; work project ideas from Team Janitorial Team lead: Adams as; assigning work to widely geographically distributed team members; experiment with outsider as; as first hierarchy at Automattic; job of, at Athens team meeting; Lebens as; “managing up” as responsibility of; presentation by, at Budapest company meeting; report by, at Automattic board of directors meeting Team NUX (New User Experience) Team Polldaddy Team Post Postmodernism Team Social: arrived late for employee group photo Team Social meet-up (Athens, Greece): author's arrival in Athens; discussion about taking on Highlander project; as first Automattic team meet-up; homeless child encounter; Mullenweg as facilitator of culture at; Parthenon as inspiration; play during; short break after; small feature shipped; work on Highlander; working in Hotel Electra lobby Team Social meet-up (Hawaii); experiments at; play during; replacement team lead selected and installed Team Social meet-up (Lisbon, Portugal): choice of time and place for; experiments at; larger size of team at; play during; traditions for getting feedback at Team Social meet-up (New York City): play during; town hall meeting broadcast from; work on Jetpack Team Social meet-up (Portland, Oregon); meeting preceding; play during; site for; work on Highlander at Team Social mini-team meet-up (San Francisco) Team Social's P2: creation of; first post on; header updated; IntenseDebate postmortem on; new photo and team name on; pants running joke on Team Theme Team Titan Team Vaultpress Team VIP Teams: advantage of small-sized Textpattern Thinking: attempt to encourage holistic, about WordPress; cathedral-vs. bazaar-style, about shipping; cathedral-style, about customer service; incremental; long-term, at Automattic; shifting between short-and long-term Thomas, Matt Thompson, Jody Tickets: author's work on; as focus of customer support work; monitoring work on Town hall meetings: August 2010 (from San Francisco); February 2011 (from New York City) TRAC (bug database) Traditions: “blank in a blank” photos; as element of workplace culture; for getting feedback at team meet-ups; of work as serious and meaningless Training Transparency: of communications; as element of WordPress philosophy True Ventures Trust: importance for teams; necessary for managing teams; patience as manifestation of; working remotely as kind of T-shaped employees Tumblr U Updates P2 Usability User interface: complicated, for WordPress; designed first; Highlander; Jetpack; for Post Postmodernism team improvement V Vacation policy Valdrighi, Michel Values Valve (game company) Ventura, Matas Venture capital (VC) firms Voice W Warner, Tom Preston Westwood, Peter Willet, Lance WordCamp WordPress: author's use of; Automattic's continued investment in; company founded to ensure future of; complex design of; complicated user interface of; development of; distinction between WordPress.com, Automattic and; features built to decrease abandoning blogs; increasing popularity of; mission of; open source as central principle of WordPress culture: development and spread of; philosophy underlying; volunteerism as element of WordPress.com: about Work Working remotely: adjustment required for; author's opinion of; Automatticians' satisfaction with; communication when; commute when; connections with coworkers when; increasing prevalence of; as kind of trust; location options; misperceptions of; no financial advantage to company; as norm at WordPress.com; poll of author's blog readers about; psychology necessary for Writing: advantages of, vs. regular jobs; books vs. customer support tickets; exiting Automattic to concentrate on; WordPress's role in Writing Helpers Photo Credits Most photos in this book were taken by the author.

…

You can't tell the difference unless you're nosy enough to peek over his shoulder. Hidden behind our ordinary appearance were unusual facts. Although we were coworkers, our sitting together was a rare occurrence. Most of the time we worked entirely online. This meeting in Athens is only the second time we have all worked in the same room. We all met once before at Seaside, Florida, where the annual company meeting was held a few weeks prior. To convene at the Elektra, I'd flown in from Seattle. Mike Adams was from LA. Beau Lebens, who I'd bet moonlighted as a secret agent, was born in Australia but lived in San Francisco. Andy Peatling, a charmingly smart British programmer, split his time between Canada and Ireland.

…

Mullenweg would set up a webcam on his laptop, and the rest of us would join two different IRC channels: one for posting questions to Matt and the other for employees to have side chats while Matt spoke. Each of us could be anywhere in the world, and the meetings would work exactly the same. At this August town hall, he talked mostly about the newly formed teams and the intent to make everyone more autonomous and productive. The company meeting was scheduled for September in Seaside, Florida, and he confirmed details about those plans. There were also questions about revenue and company strategy. Many of the questions were softballs, but there were a couple of bold ones. The IRC channel was filled with many jokes, sarcastic commentary, and links to references about whatever Matt said.

Suburban Nation

by

Andres Duany

,

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

and

Jeff Speck

Published 14 Sep 2010

Whether America grows into a placeless collection of subdivisions, strip centers, and office parks, or real towns with real neighborhoods, will depend on whether its citizens understand the difference between those two alternatives, and whether they can argue effectively for healthy growth. Toward that end, we offer this book. It is a summing up of our experiences, as designers and citizens, over the past two decades all across our land. Since 1979, when we were first asked by Robert Davis to design Seaside, Florida, we have been intimately involved in the creation and revitalization of villages, towns, and cities from Cape Cod to Los Angeles. Everywhere we’ve visited, we have observed and studied urban and suburban life: walked the downtowns, cruised the suburbs, enjoyed meals in homes, given lectures in university theaters, corporate boardrooms, and high school cafeterias.

…

When this fact is widely acknowledged, government officials, designers, and citizens will begin to act with the confidence that what is good for neighborhoods is good for America. Then, the work of rebuilding can begin. ANDRES DUANY ELIZABETH PLATER-ZYBERK JEFF SPECK SUBURBAN NATION ANDRES DUANY and ELIZABETH PLATER-ZYBERK lead a firm that has designed more than three hundred new neighborhood and community revitalization plans, most notably for Seaside, Florida, and Kentlands, Maryland. They are co-founders of the Congress for the New Urbanism and they lecture and teach widely, including at the University of Miami, where Plater-Zyberk is Dean of the School of Architecture. After leading projects at Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co. for a decade, JEFF SPECK spent four years as director of design at the National Endowment for the Arts, where he founded the Governors’ Institute on Community Design.

…

Louis, Pruitt Igoe housing project San Antonio San Bernardino (California) San Diego San Francisco; Embarcadero Freeway Santa Barbara Santa Fe Savannah schools; consolidated districts; federal mandate on; in new towns and villages; state policies on; urban Schuster, Bud Seagrove (Florida) Seaside (Florida); architectural style of; civic buildings in; live-work units in Seattle security; private segregation, income-based Sennett, Richard sense of place septic-tank sprawl Sert, Jose Luis setbacks sewage facilities Shaker Heights (Ohio) shipping methods shootings, high school shopping centers; adjacency versus accessibility to; along highways; versus main streets; neighborhood-scale; see also malls sidewalks; width of Sierra Club Silvetti, Jorge single-family houses; architectural style of; builders of; design of, value and; facades of; federal loan programs for; in new towns and villages; taxes on; urban single-use zoning; adjacency versus accessibility in; investor security and; in regional planning site plans; of five-minute walk neighborhoods site-value taxation Sitte, Camillo smart growth, government policies on “smart streets,” Snyder, Mary Gail soccer moms social decline, environmental causes of social equity: greenfield development and; regional planning and Southern California Association of Governments South Florida Water Management District Soviet Union sparse hierarchy spatial definition special-needs populations, facilities for speeding Spivak, Alvin sports events, urban sprawl; aesthetics of; architectural style and; components of; design to combat; developers and; environmentalist attack on; government policies to combat; history of; homebuilders and; housing as largest component of; increased automobile use and; municipalities bankrupted by; parking requirements and; plans for; poverty and; principles for reshaping, see new towns and villages; proactive approach to fighting; regional planning and; road rage and; successes in fight against; traffic congestion created by; victims of squares, town Stalin, Joseph Stanford Research Institute, state policies stores, corner, see corner stores; see also retail streets: in new towns and villages; pedestrian-friendly, see pedestrian-friendly design; in subdivisions; termination of vistas on; traditional neighborhood; width of strip centers, see shopping centers Stuart (Florida) style, architectural subdivisions; adjacency versus accessibility of shopping to; anticipated costs of servicing; boring; connectivity of new neighborhoods and; construction costs for; “cookie cutter,” 48; crime in; and federal loan programs; homebuilders and; landscaping of; marketing of; open space in; permitting process for; public realm and; street design in subsidies, retail suicide, teenage Supreme Court, U.S.

Who's Your City?: How the Creative Economy Is Making Where to Live the Most Important Decision of Your Life

by

Richard Florida

Published 28 Jun 2009

These places are typically oriented to pedestrian traffic (they restrict the use of cars) and shaped around town centers. One of the most famous examples is Celebration, Florida, on the outskirts of Disney World. But even though they have town centers, these new urbanist communities can lack diversity. Seaside, Florida, Duany’s signature project, was the community used in the movie, The Truman Show. Jim Carey’s character is unaware that he is living in a constructed reality surrounded by fake friends and family, leading a life intended for the entertainment of those who live outside it. All of these communities involve trade-offs.

…

Russia Rutgers College Ryan, Rebecca Sachs, Jeffrey Sacramento Safety/security(fig.) family and Salt Lake City San Antonio San Diego San Francisco (fig.) San Francisco Bay Area San Jose Sanchez, Matt Sansom, Liva Santa Fe Institute São Paulo Sapporo(fig.) Saxenian, AnnaLee Scandinavia Scenes Schumpeter, Joseph Schwartz, Christine Scientific discovery, clustering of (fig.) Seaside, Florida Seattle Seemel, Gwenn Selective migration Self-actualization openness and Self-esteem Self-expression Seligman, Martin Sense of self Seoul Seoul-San(fig.) September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks Service sector growing job markets and India and Sex and the City (Edlund) Sex and the City (television series) Sex Pistols Shanghai (fig.)

The End of the Suburbs: Where the American Dream Is Moving

by

Leigh Gallagher

Published 26 Jun 2013

But in 2010, in the depths of the housing crisis, McLinden came across an opportunity in his native Libertyville, Illinois, an affluent North Shore suburb thirty-five miles from Chicago. An upscale townhome community on a desirable parcel of land steps from the town’s Main Street had fallen on hard times; just five of a planned thirty-one townhomes had been built before the developer went belly-up. McLinden had recently seen Seaside, Florida, and had connected with the “romance” of the old-fashioned town, the front porches, and the narrow streets. He thought this could be the way of the future and saw particular potential in the parcel’s location steps from Libertyville’s bustling Main Street. He bid on the land and won—and began turning School Street into what is essentially a model of New Urbanism: a row of twenty-six arts and crafts–style bungalows nestled right up against one another, each with its own wide front porch.

…

., 38, 157, 198 Rose, Jonathan, 16, 203 Roseman, Diane, suburban experience of, 79–82, 84–85, 89–90, 92, 95, 111–12, 150 Rubin, Jeff, 105 St. Louis, renewal and growth (2011), 168 Salmon, Felix, 45 San Francisco, corporation relocations to, 173–74 San Mateo, California, 41 Schools declining enrollments, 147, 150 suburban, 23–24 School Street, Illinois, 140–41, 200–201 Seaside, Florida, 116, 120, 135, 140 Sellers, Pattie, 88 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944), 35 Shea Homes, 6 Sherman, Sam, 117–18, 140, 210 Shiller, Robert, 8 Shopping malls decline/vacancies, 180 emergence of, 44–45 retrofitting as communities, 180–81 Single-use zoning, 39–42, 63 Small-home movement, 138–140, 159 Small House Society, 138 Smart Growth America, 46 Smoke, Jonathan, 24, 157, 160, 210 Social interaction commuting problem, 97–98 loneliness of suburbanites, 91–92, 132–33 in walkable communities, 116, 120, 123, 134, 136, 140, 141 walking, benefits for, 92–93 Speck, Jeff, 83, 118 Spitz, Steven, 79–80, 112 Sports stadiums, in cities, 176–77 Sprawl anti-sprawl movement.

Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design

by

Matthew Carmona

,

Tim Heath

,

Steve Tiesdell

and

Taner Oc

Published 15 Feb 2010

Projects may, for example, claim to be New Urbanist, but feature few of the Charter principles; they may adopt New Urbanist layouts but not be mixed-use, mixed-income, and mixed-tenure, nor be transit-oriented development (see Sohmer & Lang 2000) (Figure 2.8). FIGURE 2.8 Seaside, Florida (Image: Steve Tiesdell). Many projects (self-)described as ‘New Urbanist’, including some of the best known (e.g. Seaside, Florida and Kentlands, Maryland), do not conform with the core principles outlined in the CNU Charter. It is thus useful to distinguish ‘deep’ and ‘shallow’ variants, where deep New Urbanism conforms with a high proportion of the Charter principles (see also Sohmer & Lang 2000) Walters (2007: 157) argues that, for all its flaws, no other activist-based approach to urban design in America matches New Urbanism in terms of projects built, nor in the impact on local government regulatory practice (see Chapter 11).

…

section=publications_EDG http://www.transitorienteddevelopment.org http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/currentplanning/urbandesign/index.htm Index A Accessibility 81, 137disability and 158–160 mobility and 160–161 physical access 156 robustness and 247 symbolic access 156 visual access 156 Active engagement 211 Active frontage 215–219 Activities in public space 236 Adelaide, Australia 101, 105 Advisers 282 Aesthetic preferences 85–101patterns and 170 Agency 258 Agency models 270 Air quality 228 Alexander, Christopher 3, 6, 7, 14, 102, 103, 145, 176, 177, 203, 214, 219, 258–262, 293–294, 369 ‘All-of-a-piece’ urban designers 19 Animation 19 Appleyard, Donald 8–10, 12, 39, 102, 103, 106, 113, 116, 170, 240, 269, 346, 369, 372, 378, 379 Appraisal 302–306area-wide appraisal 303–304 district/region-wide appraisal 302–303 site-specific appraisal 305–306 Architectural code 317 Architecture 184–186types 78–92see alsoBuildings Authenticity, lack of in invented places 128–130 B Bacon, Edward 57, 111, 122, 175, 208, 259, 264, 321, 353, 370, 372, 374, 383 Balance 139 Balanced communities 142 Banerjee, Tribid 137 Barcelona, Spain 138 Barnett, Jonathan 16, 93, 97, 259, 285, 370 Battery Park City, New York, USA 93 Beijing, China 127 Ben-Joseph, Eran 12, 91, 92, 108, 109, 316, 370, 384–386 Bentley, Ian 4, 9, 11, 13, 16, 50, 56, 60, 77, 82, 91, 96, 101, 103, 121, 149, 177, 220, 227, 254, 256, 288, 289, 291, 333, 370, 371 Biddulph, Michael 42, 102, 109, 124, 142, 313, 324, 331, 370–371, 381, 385 Bilbao, Spain 45 Birmingham, England/UK 108 Bosselmann, Peter 175, 182, 331, 333, 343, 348, 351, 353, 356, 370, 371 Boston, Massachusetts, USA 193 Boundaries: edges 113–115 neighbourhoods 141–147 Breheny, Michael 25, 39, 223, 371, 382 Brisbane, Australia 101 Builders 283 Buildings as constituents of urban blocks 93–94 attributes of good buildings 243–244 freestanding buildings 85–86, 186 structures 61 symbolic role of 118 urban architecture 184–186 Built environment professions, roles of 12–13 Burgage plots 78 Burgess's Concentric Zone Model 28 C CABE (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment) 53 Cadastral (street) pattern 80–82accessibility 81 permeability 81 persistence of 101 Calthorpe, Peter 10, 15, 41–42, 84, 108, 226, 371–372 Capital web 234–240 Carmona, Matthew 7, 12–13, 55–59, 70–71, 137–139, 184–185, 219–220, 233–236, 263–265, 278, 284, 291–292, 310–311, 321–331, 355–356, 364–368 Carr, Stephen 141, 154–155, 208–209, 211, 372, 380 Cars 103accessibility and 153 impact on urban form 38 motorist's visual experience 170 parking 217 problems of car dependency 37 road networks 77, 90 traffic calming measures 237 traffic reduction proposals 238see alsoTransport Central Business District (CBD) 28block structures 57, 78, 83 Change 84management of 243–244 robustness 253–256 time frames of 252–253 urban environment 14see alsoUrban development Charter for New Urbanism 41–42 Chicago 83 Chicago School 28, 29 Childs, Mark 16, 169, 262, 263, 372see alsoconcinnity Choice 49 Circulation mesh 101 Cities 101Central Business District (CBD) 25block structures 57, 92, 93 identity 112 images of 127districts 128 edges 101 landmarks 113 nodes 41 paths 113 transformations in urban form 230industrial cities 29 informational age urban form 31–32 post-industrial urban form 29–31see alsoUrban design; Urban development; Urban environment; Urban morphology; Urban space City Beautiful Movement 3 Civic design 3 Comfort 8, 160 Communication 210communication gaps 332–335designer–non-designer gap 333 designer–user gap 334 powerful–powerless gap 334 professional–layperson gap 332–333 reality–representation gap 333 informative 349 persuasive 269 technology 31–34, 46impact on urban form 38see alsoRepresentation Communities 10balanced communities 55, 57–59 community motivators or catalysts 14 gated communities 149 role in development process 279see alsoParticipation Community urban design 17 Compact city/cities 26 Competition 45, 61 Computer imaging and animation 354 Computer-aided design 350–351 Computers, participation and 229 Concept providers 19 Conceptual urbanism 40, 41 Concinnity 262 Congress for New Urbanism 9–10 Connotation 117 Conservation 245–247, 249management 270 Consultation 284 Containment 176, 178 Continuity of place 247–248 Controls 31, 150, 258public sector role 295see alsoPublic sector smart controls 34 zoning controls 308see alsoAppraisal Conzen, John 77, 78, 183, 252, 373 Copenhagen 242 Copenhagen, Denmark 175 Crawford, Margaret 44, 372–373, 378, 381, 385 Crime 147displacement 153 fear of victimisation 165 perception of 169 prevention 307‘broken windows’ theory 328 dispositional approaches 150 situational approaches 150see alsoSecurity Crime Prevention Through Environment Design (CPTED) 150 Cul-de-sacs 151, 152 Cullen, Gordon 3, 6–7, 170, 174–175, 177, 182–185, 316, 345–346, 353, 373, 376see alsoTownscape Culture 113, 124mass culture 124 Curvilinear layouts 83 Cuthbert, Alexander 4, 5, 52, 55, 165, 205, 373 D Decentralisation 32, 25, 39 Democracies 63 Denotation 117 Density 223–226benefits of higher density 223 urban form and 224 Denver, Colorado, USA 42 Design 3, 71–74policies 18see alsoUrban design Design briefs 312–313 Design codes 316–319 Design frameworks327 seeUrban design Detroit, Michigan, USA 23 Developers 275–279motivations of 275–279 types of 275 Development advisers 282 Development funders 287 Development pipeline model 271, 270–274development feasibility 270–274market conditions 272–273 ownership constraints 271 physical conditions 271–272 project viability 273–274 public procedures 272 development pressure and prospects 270see alsoDevelopment process Development process 11–12, 269–295actors and roles 269–270, 274–275adjacent landowners 283 advisers 282 builders 282 developers 275–279 funders 280–281 investors 280 landowners 279–280 motivations of 285 occupiers 284 public sector 284–286 land and property development 269–274 models 270agency models 270 equilibrium models 270 event-sequence models 270 institutional models 270 structure models 270see alsoDevelopment pipeline model quality issues 286–295monitoring and review 324–325 producer–consumer gap 286–288 public sector role 297, 301 urban design quality 291–295 urban designer's role 288see alsoUrban development Diagrams seeRepresentation Disability 158–160 Discovery 213–214, 258 Disneyland 129 Disneyworld 152–153 Displacement 152 Districts 115 Dovey, Kim 70, 117, 119, 120, 123, 124, 130, 264, 331, 374 Duany, Andres 9, 12, 31, 37, 42, 80, 90–92, 109, 143–144, 147, 188, 222, 234, 257, 317–320, 333, 355, 374see alsoNew Urbanism Duany & Plater-Zyberk (DPZ) 9, 37, 144, 317–318, 355, 374 E Eco-masterplanning 49 Edge cities 41 Edges 89–90, 173–178 Edinburgh, Scotland/UK 197 Education 325–326 Electronic communication 21, 32impact on urban form 38 Ellin, Nan 10, 14, 119, 129–130, 140–141, 146, 148, 155, 263, 282, 297, 374–375see alsoIntegral Urbanism Enclosure 179squares 170 streets 182–183 Engagement 209, 213active 211–212 passive 209 English Heritage 196, 304 Environment seeUrban environment Environmental design 93, 150–152lighting 228–229 microclimate 226 sun and shade 227 wind 227–228 Environmental footprints 53 Environmental issues 51–55fossil fuel consumption 37, 38 global warming 38, 46 pollution 51, 55 sustainable development 7–8, 11, 51, 233by spatial scale 58–59 density and 224 strategies for 200, 218 Environmental meaning 117–119 Environmental perception 111–119 Environmental symbolism 117–119 Equilibrium models 270 Equitable environments 158disability 158–166 mobility 160–161 social segregation 145, 146 Essex Design Guide 92 Event-sequence models 270see alsoDevelopment pipeline model Everyday Urbanism 40 Exclusion 158–160disability and 158–160 mobility and 145 strategies 150–153 voluntary exclusion 148 Facades 178, 186–187 F Facilitators of urban events 19 Fear of victimisation 148 Figure-ground techniques 346 Figure-ground studies 190 Finance 269funders 280–281 investors 283 Fishman, Robert 15 Floorscape 193–195 Florida, Richard 8 Flusty, Steven 29, 156, 205, 208, 211–213, 373, 375 Footpath design 234–236 Fossil fuel consumption 37–38, 46, 51 Fragmentation 11–12, 64by roads 90–91, 256 social fragmentation 257 Frontage 183 Functional zoning 220–222 Funders 280–282 G Gans, Herbert J 133, 143, 144, 253, 375 Garages 216 Garden cities 25 Garden suburbs 199 Garreau, Joel 27, 28, 259, 262, 314, 375see alsoEdge cities Gated communities 291 Geddes, Patrick 319 Gehl, Jan 3, 7, 110, 202, 207–211, 236, 242, 259–261, 375see alsoactivities in public space Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 346, 349 Gestalt theory 170 Glasgow, Scotland/UK 193 Global context 51–55 Global warming 38, 46 Globalisation 124 Governance 64 Government 63–65market–state relations 65–68 reinventing of 69 structure of 77 Grid erosion 90 Guideline designers 19 H Harmonic relationships 173 Harvey, David 22, 55, 61, 68, 69, 124, 125, 130, 376 Hearing 111 Hebbert, Michael 15, 86, 88, 105, 109, 229, 377 Hierarchy of human needs 134, 136 Hillier, Bill 82, 150–152, 203–208, 377 Home Zones 109 Hulme, Manchester 280 I Icon, iconic 117, 126–127see alsostarchitect Identity 90, 92personalisation and 121 Image 112–113 Imageability 113 Images 113districts 115 edges 114 landmarks 116 nodes 115 paths 114 Incentive zoning 308 Incivilities 148 Industrial cities 22 Industrial Revolution 25 Informational age 31 Infrastructure 230designers 16–17 Institutional models 270 Integral Urbanism 10, 14, 263see alsoEllin, Nan Integration 187–193 Internet 342 Invented places 128–130lack of authenticity 132 manufactured difference 103–104 other-directedness 130 superficiality 130 Investors 256 Involvement seeParticipation J Jacobs, Allan 8–9, 12 Jacobs, Jane 3, 7, 10, 41, 135, 150, 151, 202, 258, 265, 378 Japanese cities 50 Jarvis Bob 6 K Kaliski, John 44 Kelbaugh, Douglas 23 Keno Capitalism 29 Kentlands, Maryland, USA 42, 317, 318see alsoNew Urbanism Kinaesthetic experience 170–176 Knox, Paul 23, 28, 30, 31, 39, 59, 112, 117–119, 121, 124, 166, 213, 244, 275, 279, 371, 374, 378–379, 381 Koetter, Fred 78, 94–95, 259, 384 Koolhaas, Rem 45 Krier, Leon 86, 95, 97, 102, 142, 172, 266, 379 Krier, Rob 95, 96, 145, 179, 222, 379 Kunstler, John Howard 14, 26, 37, 38, 227, 258, 379 L Land development 264see alsoDevelopment process; Urban development Land markets 5 Land uses 13mixed use 220–223 Land value 23 Landmarks 116 Landowners 279–280, 292adjacent landowners 283–284 Landscape code 256 Landscape Urbanism 45 Landscaping 198hard 199 soft 198, 199–200 Lang, Jon 12, 13, 17–19, 42, 48, 54–55, 67, 103, 111–112, 133, 136, 220, 332, 361, 379 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA 23 Lawson, Bryan 96 Le Corbusier 6, 21–23, 85, 87, 183, 369, 371, 379 Lefebvre, Henri 44, 84, 86, 202, 241, 246, 380 Leinberger, Christopher 33, 34, 37, 60, 62, 91, 269, 281–282, 297, 380 Lighting 228–229natural lighting 228 street lighting 228 Local context 47–51 London 48, 253, 299Canary Wharf 70 Docklands 70 Los Angeles School 29 Los Angeles, California, USA 29 Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastassia 11 Lynch, Kevin 3, 6–8, 10, 112, 113–116, 121, 145, 147, 154, 169, 170, 212, 241, 243, 245–247, 253–254, 258, 297, 302, 305, 345, 369, 380 M MacCormac, Richard 72, 216–218, 223, 239, 247, 380 McGlynn, Sue 9, 12, 14, 288–289, 334, 346, 370, 377, 380 Madanipour, Ali 4, 59, 124, 215, 219, 257, 277, 380, 381 Maintenance 328–329 Management 326–329conservation 327–328 maintenance 328–329 public realm 139–141 regeneration 327 transport 326–327 Managerialism 376 Manchester, England/UK 115 Manhattan, New York, USA 33, 83, 100 Manipulation 331–335 Maps seeRepresentation Market context 55–60, 290, 364market–state relations 65–68 operation of markets 60–61 Marketplace urbanism 40, 41 Marshall, Stephen 20, 23, 91–93, 261, 262, 372, 378, 381 Maslow's hierarchy of needs 134 Mass culture 124 Master plans 229 Meaning 113, 116–117neighbourhoods 141–147 Melbourne, Australia 70 Microclimate 226–228 Mitchell, Bill 31–34, 49, 50, 137, 159, 160, 239 Mixed use 220–223 Mobility 160–161 Models 351–353Burgess's Concentric Zone Model 28 conceptual models 352 development process 269–295agency models 270 equilibrium models 270 event-sequence models 270 institutional models 270 structure models 270 presentation models 352 working models 352see alsoDevelopment pipeline model Modernism 119Modernist urban space 23, 77 New Modernism 25 symbolism and 119 Monderman, Hans 108, 197, 198 Montgomery, John 112, 120, 122, 200, 206, 221, 244, 381 Monuments 180 Moudon, Anne Vernez 77, 79, 102, 108, 222, 228, 254, 256, 266 Movement, through public space 201 N National Playing Fields Association 234 Neighbourhoods 141–147boundaries 145 mixed-use 220–223 neo-traditional neighbourhoods (NTDs) 9–10 size of 144, 149 social mix and balanced communities 145 social relevance and meaning 145 traditional neighbourhood developments (TNDs) 9–10, 142 types of 116 Neighbourhood Unit 143 Neo-liberalism 68 Neo-traditional neighbourhoods (NTDs) 9–10 Newman, Oscar 24, 37–40, 51, 92, 150, 151, 224, 335, 376, 382 New Modernism 25 New Urbanism 9–10, 41–43Charter for 41–42 New Urbanist codes 317, 319 New York, USA 32 Nodes 115 Noise 220 O Obsolescence 248–252 Occupiers 284 Open space 234 Opportunity reduction (approaches to crime prevention) 150 Opportunity space 65 Organic growth 262 Organicists 14 Orthographic projections 348, 349 Ownership constraints 271 P Paraline drawings 349, 350 Paris 10 Parking 238–239see alsoCars Participation 297, 329bottom-up approaches 336 top-down approaches 336 Passive engagement 209–210 Paths 13–14 Patterns 6–9aesthetic preferences and 169 plot pattern 79–80see alsoCadastral (street) pattern Pedestrian activity maps 344 Pedestrian pockets 9–10 Pedestrianisation 235Copenhagen 242, 260–261 Perception 111–119environmental perception 111–119 of crime 149 Performance indicators 324 Perimeter cities 26 Permeability 99 Personalisation 121 Perspective drawings 349–350 Persuasion 331–335 Perry, Clarence 87, 89, 141–143, 382see alsoNeighbourhood Unit Perth, Australia 101 Phenomenology 112, 120 Photomontages 350 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 250 Phoenix, Arizona, USA 38 Physical conditions 271–272 Place image 112–113 Place identity 111, 112 Place theming 128 Place attributes of successful places 206 construction of 119–125 identity of 121 invented places 128–130lack of authenticity 132 other-directedness 130 superficiality 130 making places tradition of urban design 7 sense of 120–121neighbourhoods and 141–147 personalisation 121 territoriality 121 significance of 20 Placelessness 123–125globalisation and 123 loss of attachment to territory 124 mass culture and 124 Plants 209 Plater-Zyberk, Elizabeth 9, 37, 144, 317, 330, 374see alsoNew Urbanism Plot pattern 79–80 Pod developments 90–91 Policy 306–325 Policy makers 19 Politics 63 Pollution 33, 39 Portland, Oregon, USA 363 Postmodernism 119, 128, 130superficiality 130 symbolism and 117–119 Post Urbanism 43 Poundbury, Dorchester, UK 42, 236 Power 118, 119, 332 Powergram 288–291, 334 Prague, Czech Republic 80 Precinct principle 89 Preservation 246–247, 252 Privacy 219–220aural privacy 220 visual privacy 219–220 Private sector 65 Privatisation 68, 140, 148 Producer-consumer gaps 277, 285 Professional–layperson gap 332–333 Project for Public Space 127, 134, 138, 206, 292 Project viability 273–274 Property development 4see alsoDevelopment process; Urban development Property markets 222 Public goods 62 Public life 138–139 Public participation seeParticipation Public procedures 272 Public realm 10, 137–141decline of 141 design 17 exclusion strategies 156 function of 201 management and 157–158 physical and sociocultural public realms 122, 139–141see alsoPublic space Public sector 67, 69–70, 272appraisal 273area-wide appraisal 303–305 district/region-wide scale 302–303 site-specific appraisal 305–306 design briefs 312–313 design control/review 320–322 design frameworks and codes 313–316 intervention by 71 management role 298conservation 301 maintenance 328–329 regeneration 327 transport 326–327 monitoring and review 324–325 policy 229 role in development process 279 role in quality control 306 Public space 201, 205–206comfort 209 discovery 213 edges 212 engagement 209–211active 211–212 passive 209–210 exclusion strategies 157 external 139 internal 139 movement through 201, 202, 204 network 83–85 quasi-public space 138 relaxation 209 shape 266 social use of 98–103see alsoPublic realm; Urban space Punter, John 6, 35, 63, 71, 91, 122, 257, 298, 306, 308, 310, 313, 319, 322, 324, 325, 347, 355, 356, 370, 372, 383 Q Quality in Town and Country initiative 71 Quality issues 11, 12, 13constraints 361, 362 monitoring and review 324–325 producer–consumer gap 277, 286–288 public sector role 295, 301see alsoPublic sector urban design quality 336 urban designer's role 288 Quasi-public space 138 R Radiance 180, 182, 185 Reality–representation gap 333 Redevelopment 22, 88, 89 Regeneration 327 Regulatory context 68government structure 64 market–state relations 65–68 Relaxation 209 Relph, Edward 13, 112, 119–125, 128, 130, 131see alsoplacelessness Representation 343–354analytical representations 344–348 computer imaging and animation 354 computer-aided design 354 conceptual representations 343–344 four dimensions 353–354 Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 348 models 349 orthographic projections 349 paraline drawings 350 perspective drawings 349–350 photomontages 350 serial vision 353–354 sketches 350 three dimensions 349–353 two dimensions 348–349 video animations 354 Resilience 253–256 Responsive environments 9 Reurbanism – seeFishman, Robert Rhyme 172 Rhythm 172 Rhythmic repetition 241 Road design 234–238 Road networks 86impact on urban form 21, 25, 32see alsoCars; Transport Robustness 253–256access and 304 cross-sectional depth and 254, 256 room shape and size and 254, 256 Rome, Italy 175 Rowe, Colin 78, 94, 95, 259, 384see alsoFigure-ground studies Rybczynski, Witold 83, 131, 300, 384 S Safety 147–15324-hour cities 244 road design and 234–238 San Francisco, California, USA 10 Savannah, South Carolina, USA 82 Scale 6 Schwarzer, Mitchell 36–37, 40–41, 159, 160, 166, 239 Seaside, Florida 42, 98see alsoNew Urbanism Seaside, Florida 317 Seasonal cycle 329 Seattle, Washington 51, 101 Security 147–154animation/peopling approach 153 crime prevention 150 fortress approach 153 management/regulatory approach 153 panoptic approach 153see alsoCrime Semiotics 117 Serial vision 353–354 Servicing 238–239 Seven Clamps of Urban Design 12 Seoul, South Korea 84 Shade 226 Shanghai, China 231 Shared streets 109 Short-termism 62, 257, 275, 360 Sieve maps 17 Sienna, Italy 176, 300 Signification 116–117 Simulation 130see alsoInvented places Sitte, Camillo 6–7, 83, 95, 177–184, 186, 200, 372, 385 Situational approach (to crime prevention) 150 Sketches 350 Slow Food 39 Slow City 39 Smart controls 297 Smart growth 36, 46 Smell 111 Social costs 62 Social mix 145–146 Social segregation 145, 146, 147 Social space 83, 84, 86see alsoPublic space Social urbanism 40, 41 Sonic environment 111 Soundscape 111 Southworth, Michael 26, 91, 92, 108–109, 215–216, 235, 236, 302, 316, 319, 370, 375, 380, 385 Space Left Over After Planning (SLOAP) 86, 234 Space seePublic space see alsoUrban environment; Urban space Space syntax 203–205 Spatial analysis 302 Spatial containment 176, 178 Squares 179–182amorphous squares 182 closed squares 181 dominated squares 182 enclosure 180 freestanding sculptural mass 180 grouped squares 182 monuments 180 nuclear squares 182 shape 180 Starchitect 125, 127see alsoicon, iconic Stevens, Quentin 205, 208, 211–213, 372, 375, 382, 385 Sternberg, Ernst 14 Street furniture 196–198 Street Reclaiming 80 Streets 182–183lighting 228–229 pattern seeCadastral (street) pattern; Road networks Structure models 270 Suburbs 29–31 Sunlight 227–228 Superficiality 130 Surveillance 150–154 Sustainable development 51–55, 307by spatial scale 58–59 density and 225 strategies for 56–57 SWOT analysis 306 Sydney, Australia 126 Symbolism 117–119 T Talen, Emily 42, 143, 147, 294, 319, 374, 385 Technical standards 12–13 Telecommunications 17impact on urban form 38 Territoriality 121loss of attachment to territory 125 Theme parks 129crime prevention 150, 151, 153see alsoInvented places Third place 138–139 Third way 71 Tibbalds, Francis 4, 6, 9, 47, 187, 255, 258, 264, 361, 386 Tiesdell, Steve 46, 65, 140, 147–149, 153, 220, 244, 269, 290–291, 363 Time cycles 241–244 management of 243–244 march of 244–257 time frames of change 252–253 Tissue studies 346 Tokyo (Japan) 50, 196 Toronto (Canada) 99 Total designers 19 Touch 111 Town Centre Management 298 Townscape 183–184 Traditional neighbourhood developments (TNDs) 9, 142 Traditional urbanism 40 Traffic calming measures 237 Transit-oriented development (TOD) 10, 226 Transport environmental sustainability issues 35 impact on urban form 29, 31, 36, 39 management 326 road networks 90 technology 31–34see alsoCadastral (street) pattern; Cars Trancik, Roger 86, 176, 332, 336, 386 Transect 311, 319see alsonew Urbanism, Andres Duany Trees 199air quality and 228 shade 227 wind protection 226, 227 Triangulation 211 Twenty four-hour society 243 U Urban architecture 184–186see alsoBuildings Urban code 317 Urban conservationists 19 Urban design 3–20, 269as joining up 13–16the professions 14–16 the urban environment 14 challenges 361 clients and consumers of 18–20 controls 12 definitions 4, 10ambiguities in 4 relational definitions 4 scale and 19 design briefs 312–313 design codes 316–319 design review and evaluation 320–324 frameworks 10–11Allan Jacobs and Donald Appleyard 8–9 Francis Tibbalds 9 Kevin Lynch 8 responsive environments 9 The Congress for New Urbanism 9–10 global context 51–55 holistic approach 363–366 ‘knowing’ urban design 17, 72, 162 local context 47–51 market context 55–62 monitoring and review 324–325 need for 11–13 practice 17–20types of 17 process 71–74 quality 272barriers to 357 questioning 360 regulatory context 63 Seven Clamps of Urban Design 13 technical standards 13 traditions of thought 6–8making places tradition 7–8 social usage tradition 7 visual-artistic tradition 6–7 ‘unknowing’ urban design 11, 17 Urban Design Alliance (UDAL) 15Placecheck 304 Urban Design Group (UDG) 15 Urban development change management 225 development briefs 312–313 environmental sustainability 35, 37, 45, 69, 165density and 225 strategies for 22 sustainable design by spatial scale 58–59 quality 286–295 smart growth 36 transformations in urban form 39industrial cities 21, 22 informational age urban form 31–34 post-industrial urban form 29see alsoDevelopment process; Urban design Urban entertainment destination (UED) 129see alsoInvented places Urban environment changes 49time frames of 252–253 components of 55 culture relationship 39 environment-people interaction 133environmental determinism 133 environmental possibilism 133 environmental probabilism 133 environmental perception 111–112 equitable environments 158–166disability 158–160 mobility 160–161 social segregation 145 management 277, 283, 326conservation 327–328 maintenance 328–329 regeneration 327 transport 326–327 quality issues 10, 12, 15public sector role 295, 301 urban environmental product 11see alsoCities; Urban development Urban grids 88grid erosion 90 Urban managers 19 Urban morphology 77–78building structures 78–79 cadastral (street) pattern 80–81 capital web 234–240 density and 225 freestanding buildings 85, 186 land uses 78 plot pattern 79–80 pod developments 90–91 public space network 83–85 return to streets 92 road networks 86 super blocks 89–90 urban blocks 93–94block sizes 96–99 persistence of block pattern 101see alsoCities Urban population growth 25 Urban quarters 142 Urban regeneration 327 Urban renaissance 35 Urban space 21, 176design 21–23 Modernist 22–23, 77 positive and negative space 176 positive space creation 176–179 traditional 77return to 114see alsoPublic space Urban Task Force 35, 71, 223, 225–226, 237, 257, 327, 386 Urban villages 142, 144 Urban Villages Forum 142 V Vegetation 199 Venice 175 Venturi, Robert 23, 128 Victimisation 148 Video animations 354 Virtual reality 354 Vision 111 Vision makers 19 Visual experience aesthetic preferences 169 motorists 175 patterns and 170 Visual privacy 219–220 Visual qualities 176–200 Voluntary exclusion 148 W Washington DC 28, 83 Wind environment 227–228 Whyte, William H (Holly) 7, 106, 135, 208, 210–211, 215, 379, 387 Woonerfs 109 World Wide Web 342 Y Yeang, Ken 49, 364, 387see alsoeco-masterplanning Z Zoning 220–223controls 297 incentive zoning 308 Zucker, Paul 95, 176, 179, 181–182, 387 Zukin, Sharon 61, 124, 128, 137, 213, 387

…

Krier identified four models or systems of urban space – in the first three buildings-define-space, while, in the fourth, buildings are objects-in-space: (a) the urban blocks are the result of the patterns of streets and squares: the pattern is typologically classifiable; (b) the pattern of streets and squares is the result of the position of blocks: the blocks are typologically classifiable; (c) the streets and squares are precise formal types: the public ‘rooms’ are typologically classifiable; and (d) the buildings are precise formal types: there is a random distribution of buildings standing in space FIGURE 4.25 Typo-morphological zoning – Seaside, Florida (Image: Mohney & Easterling 1991: 101–2). At Seaside the development is typo-morphologically zoned. An urban code defines nine development types, while a regulating plan allocates each plot a particular development type. When the plots are developed, the public space network is created as a three-dimensional entity.

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier

by

Edward L. Glaeser

Published 1 Jan 2011

The New Urbanism “stand[s] for the restoration of existing urban centers and towns within coherent metropolitan regions, the reconfiguration of sprawling suburbs into communities of real neighborhoods and diverse districts, the conservation of natural environments, and the preservation of our built legacy.” Poundbury is considerably more conservationist than the New Urbanist communities of America, such as Seaside, Florida; Kentlands, Maryland; Breakaway, North Carolina; and the Disney Corporation’s town of Celebration, Florida. These places do try to reduce car dependence, but their objectives seem as much social as they are environmental. In Celebration, 91 percent of people who leave their homes to work take cars.

…

About 70 percent of the homes in Celebration are single-family, and only 17 percent of Poundbury’s homes are apartments. The New Urbanist communities do have a higher concentration of condominiums than America as a whole, but they are still mostly full of traditional large homes that use lots of energy. For example, a quick look at Seaside, Florida, real estate for sale found houses between 2,000 and 3,800 square feet, a far cry from a 1,000-square-foot urban apartment. Kentlands, Maryland, another New Urbanist model, was similarly full of four- and five-bedroom homes that need plenty of air conditioning during humid Maryland summers. While Prince Charles seems to long for a simpler, more agrarian world, Ken Livingstone’s green vision combines sustainability and dynamic urban growth.

Retrofitting Suburbia, Updated Edition: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs

by

Ellen Dunham-Jones

and

June Williamson

Published 23 Mar 2011

Most of the original 75,000-square-foot center was retained, though several buildings were gut-renovated. (See Figure 5-3.) New shops with more traditional architectural detailing were added to form a small double-fronted outdoor mall surrounded by “streets” with sidewalks, transforming the center’s focus from the car to the pedestrian. Inspired by the new urbanist example of Seaside, Florida, the developers wanted to do more, to create a real village, like the older examples that existed elsewhere on Cape Cod. Thus began a long process, now over two decades in duration, of adding to that initial retrofit to establish a substantial town center.3 Figure 5-3 In the 1986 Chace and Storrs retrofitting plan, the Star Market supermarket building was retained.

…

Community participants’ desires for green construction, nonchain-store retail, extensive public art, and affordable senior housing led to several innovative elements in the plan: a 1,500-foot-long, 50-foot-tall public art screen wall along the interchange intended to function as a solar collector, wind harvester, and gateway to Rockville; green roofs for most of the buildings and permeable pavers in the public spaces; and the development of a market building for inexpensive “incubator” local retail (perhaps modeled on those at Mashpee Commons and Seaside, Florida), as well as inclusion of a large restaurant near the project’s entrance. The project will provide approximately 850 condominiums and apartments, plus 106 moderately priced units reserved for seniors in five wrapped parking deck residential buildings organized around a series of walkable streets, art-filled public spaces, and courtyards designed for social interaction.

Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities

by

Witold Rybczynski

Published 9 Nov 2010

., 10, 142 Robinson, Charles Mulford, 14–27, 44, 51 Rochester, New York, 23 Rock-and-Roll Museum (Seattle), 137 Rockefeller Center (New York City), 25, 72, 110, 149 Rockefeller Foundation, 57 Rockville Town Square (Rockville, Maryland), 107 Rodwin, Lloyd, 61 Rogers, Richard, 141 Roth, Emory, 87 Roth, William, 120 Rothenburg, Germany, 35 Rouse Company, 148 Rouse, James, 124–25 Royal Opera Arcade (London), 94–95 RTKL, 108 Ruhlmann, Jacques-Émile, 41, 42 Russell Sage Foundation, 33–34, 36, 37, 38 Russian Hill (San Francisco), 54 Sacramento, California, 23 Safdie, Moshe, 190–91, 192, 195, 196 Sagalyn, Lynne, 100 Saint-Gaudens, Augustus, 21, 22 Saint Petersburg, Russia, 95 Salisbury, Harrison, 56 Salon d’Automne show, 40–41, 42, 50 Salt Lake City, Utah, 183 San Antonio, Texas, 122–24 San Diego, California, 24, 118, 170 San Francisco, California: and benefits of cities, 175; and City Beautiful movement, 24, 58–59; city center of, 76; Civic Center in, 58–59; density of, 177; department stores in, 97; downtown of, 89, 176, 177; employment in, 183; grid planning model in, 13; as port city, 118, 120–22; residential streets in, 54; riots in, 79; tourism in, 184; as transit-oriented city, 183; walkability in, 193; waterfronts in, 118, 120–22; World’s Fair in, 24 San Jose, California, 106, 167 San Remo Building (New York City), 87 Sandusky, Ohio, 13 Santa Barbara, California, 23 Santa Fe Effect, 174 Santa Monica, California, 83 Santana Row (San Jose, California), 106 Saunders’s grocery (Memphis), 102–3 Savannah, Georgia, 10–11, 87, 164 Schlesinger, Leopold, 96 Science Fiction Museum (Seattle), 137 Scott, M. H. Baillie, 32 Scully, Vincent, 21–22, 92 Sears Tower (Chicago), 77 Seaside (Florida resort), 85 Seattle, Washington: and benefits of cities, 175; and cities Americans want, 168; and City Beautiful movement, 25; downtown of, 176, 177; employment in, 183; as favorite American city, 170; iconic architecture in, 137; as port city, 118, 120; shopping centers in, 97–98; as transit-oriented city, 183; waterfronts in, 113, 118, 120; and Wright’s Broadacre City, 72 Second Empire style, 135 Seligman, Daniel, 54 sense of place, 146, 157 Shaker Heights, Ohio, 38 Shalom Baranes Associates, 156 Shaw, George Bernard, 28, 30 Sheep Meadow (Queens), 7 shipping containers, 119–20 shopping: Jacobs’s concerns about, 52; origins of changes in, 94.

The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a New American Dream

by

Christopher B. Leinberger

Published 15 Nov 2008

(It is possible, but not ideal, to be nontransit-served and still create 118 | THE OPTION OF URBANISM walkable urbanism, as some of the examples below demonstrate). Transitoriented development can occur in any density that supports transit. In general, New Urbanism has played out on the ground as neighborhood-serving walkable urbanism. Its best-known, iconic projects, such as Seaside, Florida; Kentlands, Maryland; and Stapleton, Colorado,7 are second-home or bedroom communities (neighborhood-serving) that may or may not become regional-serving someday. “TND” as a term tends to be interchangeable with “New Urbanism” and focuses on neighborhoodserving places. New Urbanism and TNDs have played pivotal roles in the rebirth of neighborhood-serving places in suburban greenfields.

Celebrating the Third Place: Inspiring Stories About the Great Good Places at the Heart of Our Communities

by

Ray Oldenburg

Published 30 Nov 2001

Proprietor Papa Joe Glasper often tends bar at Joey’s Cory Corner. Goe’s Cozy Corner and Galatoire’s NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA I MET Richard Sexton some years ago when he asked me to write an epilogue for his book Parallel Utopias, which compared the new communities of Sea Ranch, California, and Seaside, Florida. Richard is an author/photographer who knows New Orleans intimately. His photographic book Elegance and Decadence is one of the finest ever produced on The Big Easy. Richard reports on two very different New Orleans third places. Joe’s Cozy Corner is in the Treme neighborhood of the city, a section that tourists are cautioned to avoid.

The Human City: Urbanism for the Rest of Us

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 11 Apr 2016

., 150 Rosenfeld, Michael, 128 Rotterdam, 154 Rural economies, 50 Rurbanization, 76 Russia, 55, 98, 139, 194–195 Rust Belt cities, 173 Rybczynski, Witold, 41 S Sa’at, Alfian, 99 Sacramento, 159 Sacred space, 21–23 Safety, 166–167 Saint Petersburg, 23, 33, 59 Salt Lake City, 126, 186 San Antonio, 152 San Diego, 152 San Francisco childlessness in, 117 children in, 16 decreased diversity in, 42 family households in, 144 financial jobs in, 186 as global city, 84 high-tech-related businesses in, 8 housing market in, 101–102 income spent on rent in, 174 loss of racial/ethnic diversity in, 157 as luxury-oriented city, 40 micro-apartments in, 132–133 post-familialism in, 128 racial income inequality in, 156–157 reinvention of city center in, 31 same-sex couple households in, 179 scenery of, 38 suburban inequality around, 159 as transactional city, 32 San Francisco Bay Area, 274n16 construction costs in, 11–12 foreign housing investments in, 101 global influence of, 81–83 housing bubble in, 134 as “necessary” region, 83–84 Sanitation, 68–69, 116 San Mateo County, 8 Santa Clara, California, 184 Santa Monica, 166 São Paulo, 13, 68, 69, 73 Sassen, Saskia, 80 Saunders, Pete, 41–42 Scandinavia, 136 Schama, Simon, 27 Schill, Mark, 96–97 Scruton, Roger, 146 Seaside, Florida, 161 Seattle children in, 16 decreased diversity in, 42 density of, 183 housing bubble in, 134 loss of racial/ethnic diversity in, 157 micro-apartments in, 132–133 micro-units in, 12 as “necessary” city, 84 scenery of, 38 Secularism, 125 Segregation, 156 Self, Will, 13 Sellers, Charles, 148 Sellers, Christopher, 191 Seneca, 109 Seoul colonialism in, 60 cultural district in, 107 fertility rate in, 16 growth of, 51, 176 and immigration, 87 as political power center, 25 post-familialism in, 119–121 traffic in, 187 Seoul-Incheon, 52 Sexual mores, 128–130 Shanghai, 25, 87 dispersion in, 155 foreign housing investments in, 100 as global city, 90–92 housing prices in, 175 and immigration, 87 micro-apartments in, 132–133 population of, 74 post-familialism in, 119–120 Sharma, R.

The Metropolitan Revolution: The Rise of Post-Urban America

by

Jon C. Teaford

Published 1 Jan 2006

In their manifesto on New Urbanism, Duany and Plater-Zyberk urged their followers to remember the refrain: “No more housing subdivisions! No more shopping centers! No more office parks! No more highways! Neighborhoods or nothing!”34 A scattering of New Urbanist communities attracted considerable attention at the close of the twentieth century. The initial New Urbanist offering was Seaside, Florida, a small resort community designed by Duany and Plater-Zyberk in the 1980s. They followed this with Kentlands in suburban Maryland. The Disney Corporation signed on to the movement, constructing the New Urbanist community of Celebration adjacent to its Florida Disney World. In each of these communities, the planners eschewed the cul-de-sacs, expansive lawns, and front-facing garages of standard edgeless-city subdivisions, building instead houses with small yards and garages on back alleys within walking distance of stores and schools.

Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World

by

Henry Grabar

Published 8 May 2023

Mostly, though, Disney World moves the masses on a fleet of four hundred diesel buses, which clock 175,000 rides a day, making the resort’s transit system roughly on par with that of Atlanta or Minneapolis. Just as Main Street revivalists drew inspiration from Walt Disney’s small-town facsimile in Anaheim, California, so the parking people had come to Orlando to soak in the Disney way. Two visitors were from Newport News Shipbuilding. Another was from Seaside, Florida, an architectural experiment in tightly knit urbanism that had grown so popular as a tourist destination that some visitors had to park their cars miles away and ride a shuttle bus downtown. At the NPA conference, parking people didn’t have to explain themselves. Men in oxford shirts milled about in the hallways of the Loews Sapphire Falls Resort, the colossal hotel on the edge of Universal Studios that served as our home base, ducking in and out of the day’s many panels until the drinking could finally begin.

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design

by

Charles Montgomery

Published 12 Nov 2013

eight parking spaces for every car: Chester, Mikhail, Arpad Horvath, and Samer Madanat, “Parking Infrastructure: Energy, Emissions, and Automobile Life-cycle Environmental Accounting,” Environmental Research Letters, 2010. an entirely new code: Duany Plater-Zyberk, “Projects Map, U.S,” www.dpz.com/projects.aspx (accessed January 27, 2011); Seaside, Florida, “History,” www.seasidefl.com/communityHistory.asp (accessed January 27, 2011). Seaside was the most influential: “Best of the Decade: Design,” Time, January 1, 1990, www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,969072,00.html (accessed January 27, 2011). rate of home ownership: McKenna, Barrie, “To Follow Canada’s Example, U.S.

The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community

by

Ray Oldenburg

Published 17 Aug 1999

It represents our architects’ best attempts at recreating community. A closing essay (an Afterword) by Vince Scully deserves careful attention. Recently appearing and already in its second printing is Richard Sexton’s Parallel Utopias which looks deeply into the thinking behind, and execution of, two notable attempts at creating community today. Seaside, Florida (based on an urban model despite its location) and Sea Ranch, California (based on the model of a rural community) are closely examined. Sexton is a first-rate photographer who illustrates as well as he explains in this book. A volume which catches everyone’s attention when, on my trips, I show it around is David Sucher ’s City Comforts.

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by

Kurt Andersen

Published 14 Sep 2020

What began in the late 1960s and ’70s as fond, bemused takes on old architectural styles morphed during the ’80s into no-kidding reproductions of buildings from the good old days. Serious architects and planners calling themselves New Urbanists convinced developers to build entirely new towns (first and most notably Seaside, Florida), urban neighborhoods (such as Carlyle in Alexandria, Virginia), and suburban extensions (The Crossings in Mountain View, California) that looked and felt like they had been built fifty or one hundred years earlier, with narrow streets and back alleys and front porches. A convincingly faux-old baseball park, Camden Yards in Baltimore, established a new default design for American stadiums.

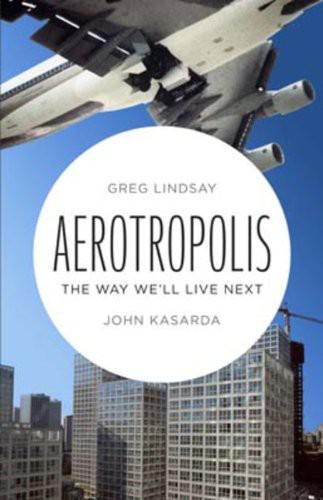

Aerotropolis

by

John D. Kasarda

and

Greg Lindsay

Published 2 Jan 2009

Doing this in a prefab, spec-built, single-use zoning universe required writing their own manual, SmartCode, containing not only guidelines for densities but also prescriptions for everything from street widths to rooflines, porches, stoop heights, and even the style of streetlights. In practice, the results were startlingly good—so good they seemed unreal. Their first and most famous experiment was Seaside, Florida. Its invocation of the Panhandle’s beach cottages was made famous by The Truman Show as a town too halcyon to be true. But New Urbanism has succeeded in building entire communities from scratch and rehabbing sick ones. Any Mayberryness is just salesmanship, a shortcut for convincing a skeptical generation of suburbanites why living in a freshly reconstituted urban village might actually be safe, humane, and fun.