Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

For people in wheelchairs, the scattering of scooters on sidewalks was an even more serious limitation on their mobility, and the experiences of vulnerable and marginalized road (or sidewalk) users are the least likely to be considered by most of the people in the start-up world. This also forces the question of whether these dockless services should be on sidewalks in the first place, and since that contradicts the ideology of Silicon Valley, many of its adherents naturally chose to see it another way. Micromobility services, as well as the autonomous delivery robots that are also being deployed on sidewalks, are not designed to place accessibility and affordability at the fore; rather, while forcing their way onto sidewalks, they are also seeking to entrench rentier business models that ensure they take a cut every time people access them.

…

Not only is this an extension of the elite projection that Jarrett Walker wrote about, as these founders and venture capitalists backed projects that worked for them but assumed—or at least claimed—they would work for everyone, but it is also a continuation of the history discussed in Chapter 2. In the aftermath of the recession, the same ideas that had been born in the 1970s and 1980s were once again at work; the same ideas that had created the techno-deterministic, free market ideology of Silicon Valley by men who held counter-cultural ideals but used them to justify their participation in the capitalist system. Even as the tech industry became a powerful force in the US economy and spread its influence around the world while people became dependent on hardware and software produced by American companies, the titans of the industry continued to see themselves as scrappy upstarts; the Davids fighting some increasingly abstract Goliath.

…

Light, “Developing the Virtual Landscape,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14:2, 1996, p. 127. 31 Ibid., pp. 127–9. 32 Benjamin Peters, “A Network Is Not a Network,” in Your Computer Is on Fire, MIT Press, 2020, p. 87. 33 Ibid., p. 85. 34 Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism, PublicAffairs, 2013, p. 6. 35 Ibid., p. 5. 36 Jarrett Walker, “The Dangers of Elite Projection,” Human Transit (blog), July 31, 2017, Humantransit.org. 37 Adrian Daub, What Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry into the Intellectual Bedrock of Silicon Valley, FSG Originals, 2020, p. 36. 38 Luis F. Alvarez León and Jovanna Rosen, “Technology as Ideology in Urban Governance,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110:2, 2020, p. 500. 39 “Instagram Boss Adam Mosseri on Teenagers, Tik-Tok and Paying Creators,” Recode Media, September 16, 2021. 3. Greenwashing the Electric Vehicle 1 David A.

How to Fix the Future: Staying Human in the Digital Age

by

Andrew Keen

Published 1 Mar 2018

She tells me about Singapore’s free, crowd-sourced MyResponder app developed by the Civil Defense Force, which enables the public to both report and respond to cases of cardiac arrest happening on the street. And she explains the importance of Data.gov.sg, the Singapore government’s one-stop portal for the sharing of datasets from seventy public agencies. But in contrast with the typically libertarian ideology of Silicon Valley, which fetishizes the free market and is deeply hostile to any governmental participation in the economy, Poh sees Virtual Singapore as an opportunity for citizens and the authorities to work together on projects that benefit both public and private interests. Whereas the seductive ideals of “sharing,” “collaboration,” and “community” are often appropriated by such successful Silicon Valley companies as Facebook to further their own intrinsically private goals, in Singapore these ideals fit naturally with the political culture created by Lee Kuan Yew.

…

In contrast, however, with Kapor Klein’s goal of building an alternative investment ecosystem to Silicon Valley, Taplin’s focus is more directly political. His 2017 book, Move Fast and Break Things, borrows its title from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s notorious mantra to disrupt as much as possible without taking responsibility for any of the resulting damage. Taplin reserves his sharpest critique for Silicon Valley’s libertarian ideology, with its fetishization of free market forces, which has enabled this new economy to so radically disrupt old business models and economic practices. And he has become a kind of informal labor organizer, encouraging the resistance of musicians and filmmakers to these controversial new models and practices.

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by

Jonathan Taplin

Published 17 Apr 2017

David Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie’s biographer, has said, “Carnegie could never have imagined the kind of power Zuckerberg has. Politics today is less relevant than it has ever been in our entire history. These CEOs are more powerful than they’ve ever been. The driving force of social change today is no longer government at all.” And the libertarian ideology of Silicon Valley has seeped its way into pop culture. As the New York Times film critic A. O. Scott pointed out, in our current fascination with superhero movies, the genre’s default ideology is a variant of the masters-of-the-universe libertarianism that energizes some of the most vocal sectors of the American ruling class.

…

The original mission of the Internet was hijacked by a small group of right-wing radicals to whom the ideas of democracy and decentralization were anathema. By the late 1980s, starting with eventual PayPal founder Peter Thiel’s class at Stanford University, the dominant philosophy of Silicon Valley would be based far more heavily on the radical libertarian ideology of Ayn Rand than the commune-based principles of Ken Kesey and Stewart Brand. Thiel, who was also an early investor in Facebook and is the godfather of what he proudly calls the PayPal Mafia, which currently rules Silicon Valley, has been clear about his credo, stating, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.”

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by

Rodrigo Aguilera

Published 10 Mar 2020

If New Optimism sounds like one giant TED Talk by a hyper-optimistic tech guru or venture capitalist, it’s because it shares with these people the boundless overconfidence of a future we should be anticipating with dangerously few reservations. There would also probably not be much fightback from the New Optimist camp if Silicon Valley ideology insidiously becomes more mainstream. The success of Trump and his enablers in mainstreaming their New Right sympathies proves that it only takes one convert reaching a position of power to legitimize a belief system. Institutionalizing it then becomes the next logical step. That Silicon Valley’s foundational ideology could form the backbone of a new American narrative is hardly inconceivable. It is an extreme version of the narrative that to a large extent already permeates the national psyche: that growth is the main determinant of human progress; that wealth the main determinant of personal success; that more individual freedom and less government is always better; and that the actions of the enlightened rich deserve few constraints.

…

Future Fetish “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” — Peter Thiel Libertarians and the New Right might be the most eager adherents of the progress narrative, but there is another group that finds within itself boundless possibilities for the future: tech bros. The pervasiveness of libertarianism within Silicon Valley has resulted in the ideology having its own subspecies known as technolibertarianism, also called extroprianism. This emerged in the late 1980s through the musings of futurist philosophers such as Tom Bell and Max More who co-founded the now defunct Extropy Institute. Technolibertarians broadly agree with the basic dogmas of the libertarian ideology such as free markets, minimal government, no censorship, and social liberalism, but have a particular fascination with the emancipatory promises of technology.

To Be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death

by

Mark O'Connell

Published 28 Feb 2017

The phrase, for all its absurdity, seemed to enclose within itself the strange cluster of desires and ideologies at the heart of transhumanism, with its faith in the power and benevolence of techno-capitalism. It was less a protest than a supplication, a prayer. Deliver us from evil. Save us from our bodies, our fallen selves. For Thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory. The word “solve,” in this context, seemed to me to encapsulate the Silicon Valley ideology whereby all of life could neatly be divided into problems and solutions—solutions that always took the form of some or other application of technology. Whether the problem was having to pick up your own dry cleaning, or negotiate the complexities and uncertainties of sexual relationships, or face the reality that you would one day die, that problem could be hacked.

The Googlization of Everything:

by

Siva Vaidhyanathan

Published 1 Jan 2010

However, it’s a mistake to think of Google’s social influence and social role as purely a function of science and engineering. Google’s social milieu, the petri dish from which it sprang, is more than technological or scientific. As the media historian Fred Turner demonstrates in From Counterculture to Cyberculture, the ideology of Silicon Valley is rooted in the practices and idealistic visions of 1960s counterculture. It’s a peculiar story: cultural anarchism melded with technologies developed for and by the U.S. military, unleashed in the service of both commerce and creativity, yet also accused of undermining both.49 Google, in particular, incorporates a twenty-first-century form of countercultural hedonism in its corporate structure and everyday work environment: the ethos of Burning Man.

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction

by

Matthew B. Crawford

Published 29 Mar 2015

The caption read, “A master’s degree allowed her to progress from writer to content expert.” Apparently the young woman “progressed” from being a writer to someone who aggregates bits of other people’s writing. To me that sounds more like defeat. In countless little ways, any single one of which seems trivial, this liberal arts college is unthinkingly repeating bits of Silicon Valley ideology that would seem to undermine the rationale for studying the liberal arts. The university has become “the brilliant ally of its own gravediggers,” to borrow a phrase from Milan Kundera.6 Jaron Lanier criticizes what he calls “digital Maoism,” a “new online collectivism” that shows up, for example, in the way Wikipedia is regarded and used, and is the guiding spirit of firms such as Google as well.

Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture

by

Kyle Chayka

Published 15 Jan 2024

Monopolistic growth is more important to these entities than the quality of user experience and certainly more important than the equitable distribution of culture through the services’ feeds. (A digital platform has none of the curatorial responsibility of, say, an art museum.) According to Silicon Valley ideology, the pursuit of scale far outweighs any negative consequence it might have, as a memo written by Andrew Bosworth, a deputy of Mark Zuckerberg’s at Facebook, demonstrated in 2016: So we connect more people. That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs someone a life by exposing them to bullies.

Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology From Capitalism

by

Wendy Liu

Published 22 Mar 2020

A society where most people are subject to the whims of unimaginably powerful technology corporations isn’t so bad if you’re an executive at one of those corporations. No diagnosis of Silicon Valley can be written without this fundamental divide in mind. This book is an attempt to unpack the problems of the tech industry, as told through my personal story of disillusionment. It follows the arc of how I got here: from unwittingly inhaling Silicon Valley ideology as a teenager, to working in the industry, to launching my own startup. And the more I learned about the industry — its internal mechanics, and its impact on the rest of the world — the more I began to doubt. In the process of searching for an explanation, I found a golden thread of connections I had never seen before, and slowly it all started to crystallise into a coherent whole.

Utopia Is Creepy: And Other Provocations

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 5 Sep 2016

It seemed clear that those who controlled the omnipresent screen would, if given their way, control culture as well. “Computing is not about computers any more,” wrote MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte in his 1995 bestseller Being Digital. “It is about living.” By the turn of the century, Silicon Valley was selling more than gadgets and software. It was selling an ideology. The creed was set in the tradition of American techno-utopianism, but with a digital twist. The Valleyites were fierce materialists—what couldn’t be measured had no meaning—yet they loathed materiality. In their view, the problems of the world, from inefficiency and inequality to morbidity and mortality, emanated from the world’s physicality, from its embodiment in torpid, inflexible, decaying stuff.

…

Any misstep, we tell ourselves, will be quickly corrected by subsequent innovations. If we just let progress do its thing, it will find remedies for the problems it creates. “Technology is not neutral but serves as an overwhelming positive force in human culture,” writes one pundit, expressing the self-serving Silicon Valley ideology that in recent years has gained wide currency. “We have a moral obligation to increase technology because it increases opportunities.” The sense of moral obligation strengthens with the advance of automation, which, after all, provides us with the most animate of instruments, the slaves that, as Aristotle anticipated, are most capable of releasing us from our labors.

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 28 Sep 2014

Any misstep, we tell ourselves, will be quickly corrected by subsequent innovations. If we just let progress do its thing, it will find remedies for the problems it creates. “Technology is not neutral but serves as an overwhelming positive force in human culture,” writes Kelly, expressing the self-serving Silicon Valley ideology that in recent years has gained wide currency. “We have a moral obligation to increase technology because it increases opportunities.”33 The sense of moral obligation strengthens with the advance of automation, which, after all, provides us with the most animate of instruments, the slaves that, as Aristotle anticipated, are most capable of releasing us from our labors.

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by

Ed Finn

Published 10 Mar 2017

These changes will be effected not only in the material realm but in the cultural, mental, and even spiritual spaces of empowerment and agency. The algorithm offers us salvation, but only after we accept its terms of service. The important lesson here is not merely that the venture capitalism of Silicon Valley is the ideology bankrolling much of our contemporary cathedral-building, or even Bogost’s warning about computation as a new theology. The lesson is that it’s much harder to question a set of ideas when they are assembled into an interconnected structure. A seemingly complete and consistent expression of a system of knowledge offers no seams, no points of access that suggest there might be an outside or alternative to the structure.

New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future

by

James Bridle

Published 18 Jun 2018

One result of this was the growth of the software industry: freed from its reliance on hardware manufacturers, software became vendor independent, leading first to the dominance of huge companies like Microsoft, Cisco, and Oracle, and then to the economic – and increasingly political and ideological – power of Silicon Valley. Another effect, according to many in the industry, was the end of a culture of craft, care, and efficiency in software itself. While early software developers had to make a virtue of scarce resources, endlessly optimising their code and coming up with ever more elegant and economical solutions to complex calculation problems, the rapid advancement of raw computing power meant that programmers only had to wait eighteen months for a machine twice as powerful to come along.

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by

Karen Hao

Published 19 May 2025

And because those problems are so hard and so hard to think about, I think most people just choose not to, and they just accept this.” * * * — It was in this context that effective altruism arrived from the UK and found its most loyal audience. EA, to which many in OpenAI’s Safety clan were early adherents, made for the perfect Silicon Valley ideology. It preaches making the world a better place and doing it with rigorous logic, being disciplined enough to focus on the far future instead of the present, and fervently embracing the principles of capitalism and libertarianism—all in the name of morality. Core to the EA philosophy is a mathematical concept called “expected value.”

Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in This Life and Beyond

by

Tamara Kneese

Published 14 Aug 2023

The New Class Conflict

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 31 Aug 2014

Dirk Hanson, The New Alchemists: Silicon Valley and the Microelectronics Revolution (Boston: Little Brown, 1982).pp. 84, 92–94. 41. Myles D. Crandall, “Lockheed Grew up with Sunnyvale,” Silicon Valley Business Journal, February 25, 2007. 42. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture, vol. 6, no. 1 (1996): 44–72. 43. Arun Rao, with Piero Scaruffi, A History of Silicon Valley: The Greatest Creation of Wealth in the History of the Planet, 2nd ed. (Palo Alto, CA: Omniware Group, 2013). 44. Anna Lee Saxenian, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1994). 45.

…

He compares the Valley’s pretensions with those of firms that make T-shirts with Che Guevera’s picture, for sale at the local mall: Presumably, some people really believe Silicon Valley entrepreneurs when they say they don’t care about making money. This appears to be a capitalist attempt to hide capitalism, to exploit its wealth-generating capabilities without having to assume its responsibilities and drawbacks. The post-profit Silicon Valley has, for some, been quite profitable.49 Yet despite its countercultural trappings and progressive ideological leanings, Silicon Valley has turned out to be every bit as cutthroat and greedy as any capitalist region—as I will demonstrate below. The technological revolution may have changed the locus of power and influence, but it did not change the fundamentally acquisitive and self-seeking realities of human nature.

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by

Jeremias Prassl

Published 7 May 2018

Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work

by

Alex Rosenblat

Published 22 Oct 2018

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by

Andrew Keen

Published 5 Jan 2015

The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of How Social Media Rewired Our Minds and Our World

by

Max Fisher

Published 5 Sep 2022

Still, these companies accrued some of the largest corporate fortunes in history by exploiting those tendencies and weaknesses, in the process ushering in a wholly new era in the human experience. The consequences—though in hindsight almost certainly foreseeable, if someone had cared to look—were obscured by an ideology that said more time online would create happier and freer souls, and by a strain of Silicon Valley capitalism that empowers a contrarian, brash, almost millenarian engineering subculture to run the companies that run our minds. By the time those companies were pressured into behaving at least somewhat like the de facto governing institutions they had become, they found themselves at the center of political and cultural crises for which they were a partial culprit.

…

But while antitrust enforcement can be a powerful tool, it is a blunt one. Splintering Facebook from Instagram, or Google from YouTube, would weaken the companies, maybe even drastically. But it would not change the underlying nature of their products. Neither would it remove the economic or ideological forces that had produced those products in the first place. For all its talk of rebuilding trust, Silicon Valley showed, in an episode only a month after Biden’s inauguration, that it would wield the full weight of its power against whole societies to deter them from acting. Australian regulators had moved to target the Valley’s greatest vulnerability: revenue.

AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

by

Kai-Fu Lee

Published 14 Sep 2018

It’s an environment of abundance that lends itself to lofty thinking, to envisioning elegant technical solutions to abstract problems. Throw in the valley’s rich history of computer science breakthroughs, and you’ve set the stage for the geeky-hippie hybrid ideology that has long defined Silicon Valley. Central to that ideology is a wide-eyed techno-optimism, a belief that every person and company can truly change the world through innovative thinking. Copying ideas or product features is frowned upon as a betrayal of the zeitgeist and an act that is beneath the moral code of a true entrepreneur. It’s all about “pure” innovation, creating a totally original product that generates what Steve Jobs called a “dent in the universe.”

After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back

by

Juliet Schor

,

William Attwood-Charles

and

Mehmet Cansoy

Published 15 Mar 2020

Twenty years later, sharing platforms, many of which have been funded by the tech giants, would adopt the same antiregulatory stance and also become monopolies. While the path from New Communalism to the sharing economy is yet to be fully researched, there is a through line of location, people, and ideology.18 For some, the history of Silicon Valley is a case of genuinely transformative ideas and technologies gone awry. But it’s a more complicated story. From the beginning many believed that the software itself would ensure good outcomes—a strong technological determinism. It’s now clear this view was wrong. Unregulated markets frequently lead to monopolies, particularly in tech.19 The popular equation of democracy and the internet is also fatuous, as recent political events have made clear.20 And in retrospect we can see that entitlement played an important role in solidifying the Californian Ideology.

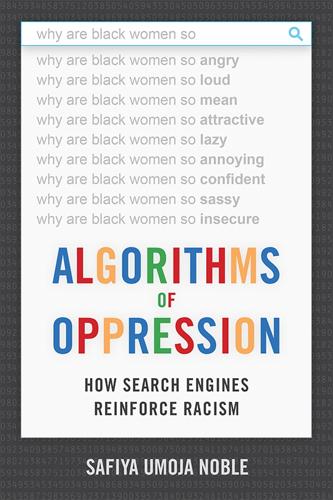

Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism

by

Safiya Umoja Noble

Published 8 Jan 2018

More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity

by

Adam Becker

Published 14 Jun 2025

“If I get pushed hard about questions about what the Singularity is going to be like,” he said, “my most common retreat is to say, ‘Why do you think I called it the Singularity?’”40 Nonetheless, the prospect of a tech-fueled civilizational apotheosis meshed well with the ideological foundations of the futurist groups already swirling around Silicon Valley in the 1980s and ’90s—and they largely didn’t share Vinge’s reluctance to speculate about what the Singularity might bring. “We see this need for transcendence deeply built into humanity,” said the futurist Max More in 1994. “It seems to be something inherent in us that we want to move beyond what we see as our limits.

…

He was, instead, asking him about housing policy in and around San Francisco. Altman prefaced his reply with his statement about AGI as a way of explaining why he hadn’t thought much about housing policy, but that answer also implies that anything other than AGI is ultimately just a footnote. This is a key part of the appeal of the ideology of technological salvation, one that’s especially important to Silicon Valley billionaires and tech executives: boiling all the problems in the world down to one question of computer technology. Altman even claims that saving democracy itself requires the growth that tech start-ups will purportedly enable. “Democracy only works in a growing economy.

Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Start-Up Bubble

by

Dan Lyons

Published 4 Apr 2016

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

As his company grew, Dave Packard became one of the area’s most important civic leaders, including a stint leading Stanford’s Board of Trustees. A staunch Republican and champion of free markets and entrepreneurial public policy, Packard had sharp political instincts to match his ideological convictions. A friend to one generation of politicians and mentor and donor to the next, he leveraged his business reputation to become a de facto Silicon Valley brand ambassador in the world of politics. And Packard may have been a free-enterprise man, but he was keenly attuned to how the tech industry’s relationship with Washington shaped its fortunes.8 Like his mentor Fred Terman, Dave Packard’s political education began during World War II, when he had rallied fellow executives to form the West Coast Electronics Manufacturers Association, known as WEMA, which successfully lobbied for a chunk of wartime military contracts.

…

At a time when big business was increasingly unpopular, particularly among young people who’d spent their college years protesting corporations as soul-crushing warmongers, this new generation of companies entered the market seemingly unencumbered by history. And while all of American society was utterly saturated in politics, the Silicon Valley crowd appeared remarkably (and to many, reassuringly) unconnected to the political. Their politics was an ideology of working hard, building great technology, and making lots of money along the way. Nearly all of them were transplants from somewhere else, their loyalties and social bonds all lay with the industry that brought them there, and they remained remarkably untouched by the local political culture.

…

Other important connectors in the Internet-age Valley salon were Tim O’Reilly and Stewart Alsop, each of whom built influential empires around annual conferences and publications aimed at the industry. 3. Quoted in Lambert et al., “Esther Dyson.” 4. See, for example, Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s incendiary take on Silicon Valley mythmaking, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture 6, no. 1 (January 1996): 44–72. On the National Performance Review, see Al Gore, The Gore Report on Reinventing Government: Creating a Government that Works Better and Costs Less (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1993). Silicon Valley also played a role in this plank of the Clinton-Gore agenda; the Vice President hailed Sunnyvale (whose then mayor was Larry Stone) as a national example of and test bed for municipal reinvention, and several policies originating there became final recommendations of the performance review. 5.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by

Steven Pinker

Published 13 Feb 2018

The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age

by

David E. Sanger

Published 18 Jun 2018

And, in a pointed jab at the NSA, the code ended with a smiley face. * * * — The Snowden affair kicked off a remarkable era in which American firms, for the first time in post–World War II history, broadly refused to cooperate with the American government. They wrapped some of that refusal in Silicon Valley’s typical libertarian ideology. But their real fear was that any open association with the NSA would prompt customers to wonder whether Washington had bored holes into their products. Snowden gave allies and adversaries alike grounds for an argument about the dangers of using American technology—the same argument the United States raised regularly about letting Kaspersky antivirus software, designed in Russia, run on American computers, or permitting Chinese firms to sell their cell phones and network equipment in the United States.

Long Game: How Long-Term Thinker Shorthb

by

Dorie Clark

Published 14 Oct 2021

Finally, in section three, “Keeping the Faith,” we’ll turn to what is often the hardest part about playing the long game: moving forward despite challenges or setbacks. In chapter 8, we’ll discuss strategic patience, the key to persevering when you’ve hit a plateau (or even, at times, when it feels like you’re slipping backward). Chapter 9 takes on failure, which usually feels awful and humiliating, Silicon Valley’s “fail fast” ideology notwithstanding. The secret is understanding the crucial difference between failure and experimentation—because if you’re learning, you’re not actually failing. Finally, in chapter 10, we’ll talk about the final step: reaping the rewards of your hard work. Ironically, that’s not always easy for successful people.

The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream

by

Tyler Cowen

Published 27 Feb 2017

Terms of Service: Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection

by

Jacob Silverman

Published 17 Mar 2015

And who would have suspected that as technology and freedom were worshipped more and more, it would become less and less possible to say anything sensible about the society in which they were applied? —Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology” In 1995, two British media theorists, Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, launched an extraordinary broadside against Silicon Valley. In a work they titled “The Californian Ideology,” Barbrook and Cameron described a “new faith” emerging “from a bizarre fusion of the cultural bohemianism of San Francisco with the hi-tech industries of Silicon Valley.” Mixing “the freewheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies,” the Californian Ideology drew on the state’s history of countercultural rebellion, its role as a crucible of the New Left, the global village prophecies of media theorist Marshall McLuhan, and “a profound faith in the emancipatory potential of the new information technologies.”

…

When work orders come through a smartphone and we know that if we don’t respond immediately, we might not get such an opportunity again? When we can’t even talk to another human being about the task at hand and we must work constantly just to make minimum wage? Well, if you share these concerns, don’t worry: Silicon Valley is already thinking ahead. And their plan involves no less than doubling down on social ideology and online labor, turning everything, and everyone, into something to be bought or sold. Welcome to the sharing economy. BAIT AND SWITCH The sharing economy combines all the elements of online labor, reputation, and social media’s marketing-of-the-self to help make one’s entire life purely transactional.

Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World

by

Clive Thompson

Published 26 Mar 2019

Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves From the American Dream

by

Alissa Quart

Published 14 Mar 2023

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by

Evgeny Morozov

Published 15 Nov 2013

It’s time we abandon the chief tenet of Internet-centrism and stop conflating physical networks with the ideologies that run through them. We should not be presenting those ideologies as inevitable and natural products of these physical networks when we know that these ideologies are contingent and perishable and probably influenced by the deep coffers of Silicon Valley. Instead of answering each and every digital challenge by measuring just how well it responds to the needs of the “network,” we need to learn how to engage in narrow, empirically grounded arguments about the individual technologies and platforms that compose “the Internet.”

…

If we don’t find the strength and the courage to escape the silicon mentality that fuels much of the current quest for technological perfection, we risk finding ourselves with a politics devoid of everything that makes politics desirable, with humans who have lost their basic capacity for moral reasoning, with lackluster (if not moribund) cultural institutions that don’t take risks and only care about their financial bottom lines, and, most terrifyingly, with a perfectly controlled social environment that would make dissent not just impossible but possibly even unthinkable. The structure of this book is as follows. The next two chapters provide an outline and a critique of two dominant ideologies—what I call “solutionism” and “Internet-centrism”—that have sanctioned Silicon Valley’s great ameliorative experiment. In the seven ensuing chapters, I trace how both ideologies interact in the context of a particular practice or reform effort: promoting transparency, reforming the political system, improving efficiency in the cultural sector, reducing crime through smart environments and data, quantifying the world around us with the help of self-tracking and lifelogging, and, finally, introducing game incentives—what’s known as gamification—into the civic realm.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by

Nate Silver

Published 12 Aug 2024

Instead I endorse Nick Bostrom’s idea of a moral parliament, which I imagined in chapter 7 as a mix of different philosophical traditions (e.g., utilitarianism, liberalism, conservatism, progressivism) that are credible and robust enough to deserve some consideration in your moral framework. It is imperative, however, to be wary of totalizing ideologies, whether in the form of utilitarianism, Silicon Valley’s accelerationism, the Village’s identitarianism,[*7] or anything else. In our fast-moving, topsy-turvy world, it’s hard to know when an ideological movement might suddenly accumulate a lot of power very quickly, as utilitarianism did under Sam Bankman-Fried, and exercise its worst impulses.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power

by

Max Chafkin

Published 14 Sep 2021

He would sometimes connect his move with the rising real estate prices in the Bay Area—complaining that as a venture capitalist, most of his investment capital was going to “urban slumlords,” in the form of commercial rents and the high salaries demanded by employees to cover their housing costs—but mostly his complaints were political, a near faithful reprise of the barbs he’d first crafted as a Stanford undergraduate, and were pitched perfectly to conservative media. Silicon Valley, he would often say, was so ideologically oppressive that it resembled North Korea. It was, he said, full of very smart but “brainwashed” workers who’d been driven into political correctness, which Thiel diagnosed as the single most important problem in American society. His critics on the left would point out the obvious hypocrisy: A man who’d vindictively destroyed a liberal media outlet for writing things he didn’t like was complaining about the oppressiveness of liberals—but on Fox and Breitbart, and among the commentators of the alt-right and the Intellectual Dark Web, he was a truth-teller, even a hero.

The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties

by

Paul Collier

Published 4 Dec 2018

Woolly: The True Story of the Quest to Revive History's Most Iconic Extinct Creature

by

Ben Mezrich

Published 3 Jul 2017

The Twittering Machine

by

Richard Seymour

Published 20 Aug 2019

The early hope of cybernetics, to design a system of control by means of organizing communication, turned into its opposite. It helped create, as Justin Joque put it, ‘a globally networked system so complex that no known model could ever describe it, let alone regulate it’.21 And by the same logic, the neo-liberal values that aligned Silicon Valley bosses with the Obama White House are not necessarily the same as the real ideological effects of the machine. We might say that if the machine has its conscious uses, it also has an unconscious. We feign omniscience at our peril. One of the pleasures of the ‘backlash’ style is to be a Cassandra, seeing it all so clearly, yet so impotently.

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by

Nicholas Lemann

Published 9 Sep 2019

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by

Gary Gerstle

Published 14 Oct 2022

Surviving AI: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence

by

Calum Chace

Published 28 Jul 2015

But for various historical reasons including military funding, Silicon Valley has assembled a uniquely successful blend of academics, venture capitalists, programmers and entrepreneurs. It is home to more high technology giants (Google, Apple, Facebook, Intel, for instance) than any other area and it receives nearly half of all the venture funding invested in the US. (43) Silicon Valley takes this leadership position very seriously, and an ideology has grown up to go along with it. If you work there you don’t have to believe that technological progress is leading us towards a world of radical abundance which will be a much better place than the world today – but it certainly helps. Probably nowhere else in the world takes the ideas of the singularity as seriously as Silicon Valley.

After the Fall: Being American in the World We've Made

by

Ben Rhodes

Published 1 Jun 2021

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by

Shoshana Zuboff

Published 15 Jan 2019

Decoding the World: A Roadmap for the Questioner

by

Po Bronson

Published 14 Jul 2020

Nobody thinks the world is without problems. The problem is we can’t agree on the problem. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley is out here doing its usual thing, trying to solve everything at once, but accidentally spreading mass confusion and plenty of sparkling distractions. Silicon Valley purposefully and intentionally creates a bubble. It’s an ideological bubble, where it’s safe to experiment on the improbable. Where mere illusions have the chance to become reality. Only by taking on the impossible can we learn what’s possible. This realm of illusion is spread by our creations. The secret appeal of social media was its meritocracy.

Woke, Inc: Inside Corporate America's Social Justice Scam

by

Vivek Ramaswamy

Published 16 Aug 2021

Artificial Whiteness

by

Yarden Katz

See also racial science Science for the People (SFTP), 45 Selfridge, Oliver, 297n61 Semi-Automated Forces (SAFOR), 43–44 Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), 264n8 settler-colonialism, 8, 16; and policing, 144; and whiteness, 161–62, 280n27 Shannon, Claude, 21–23, 241n8 Shubik, Martin, 23 Silicon Valley, 12, 79, 105; alliance with national security state, 59, 133; ideology of, 69, 166. See also governance by the numbers Simon, Herbert A., 28–33, 42, 54–55, 58, 77, 97, 99–104, 106, 108, 159, 165, 189 Simpson, Audra, 230 simulation, 23, 28, 151; in discourse on “cognitive revolution,” 268n47; for military and war, 28–29, 44, 54, 210, 213, 215–17, 220, 250n96, 298n68; limits of, 199, 291n33; and modernity, 296n60 situated robotics, 207–9, 295n51, 295nn55–56, 296n60, 299n79.

Can't Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation

by

Anne Helen Petersen

Published 14 Jan 2021

Digital Barbarism: A Writer's Manifesto

by

Mark Helprin

Published 19 Apr 2009

What follows is an affirmation of human nature versus that of the machine, via a defense of copyright, the rights of authorship, and the indispensability of the individual voice. Of late, these have come under sustained attack. A movement that, whatever its ideological origins, finds its most congenial home and support in the geek city states of Silicon Valley, has successfully channeled and combined the parochial interests both of giant corporations and legions of resentful adolescents who believe that they have a natural right to whatever they want. It is known informally as the “Creative Commons,” and the charitable mask it presents, selfless people contributing their work—software, music, writing—to the common weal, is merely the cover (not much bigger than a postage stamp) for a well organized effort to cut away at intellectual property rights until they disappear.

Your Computer Is on Fire

by

Thomas S. Mullaney

,

Benjamin Peters

,

Mar Hicks

and

Kavita Philip

Published 9 Mar 2021

Ways of Being: Beyond Human Intelligence

by

James Bridle

Published 6 Apr 2022

Letter from Charles Darwin to Alphonse de Candolle, 28 May 1880, in Francis Darwin (ed.), The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, Vol. II (London: John Murray, 1887), p. 506. 21. For the military origins of the internet, see Yasha Levine, Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet (London: Icon Books, 2019). For a critique of Silicon Valley neoliberalism, see Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, ‘The Californian Ideology’, Mute, 1(3), 1 September 1995; http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology. 22. I. O. Buss, ‘Bird Detection by Radar’, The Auk, 63(3), 1 July 1946, pp. 315–18; https://doi.org/10.2307/4080116. 23. For an account of Varley and Lack’s work, see A.

We Are the Nerds: The Birth and Tumultuous Life of Reddit, the Internet's Culture Laboratory

by

Christine Lagorio-Chafkin

Published 1 Oct 2018

The gatekeepers who determined what was on the front page of the Wall Street Journal and New York Times weren’t welcome here: This was a place where the crowd decided what was deeply interesting. To avoid that “gatekeeper” effect, the people operating the site should be hands-off and let the community be self-organizing. This perspective was a simple, rules-minimizing precursor to the “we are a platform, not a publisher” argument so many Silicon Valley media companies would later adopt. But the ideology didn’t foresee some of the ways in which it could be abused. The philosophy within Reddit assumed that humans were fundamentally good—and thus staff admins and moderators should allow users to treat the site as a free-speech sandbox. Now users were building the most bizarre and disturbing creations.

The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by

Ross Douthat

Published 25 Feb 2020

The Mysterious Mr. Nakamoto: A Fifteen-Year Quest to Unmask the Secret Genius Behind Crypto

by

Benjamin Wallace

Published 18 Mar 2025

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by

Anu Bradford

Published 25 Sep 2023

She noted how this was a pertinent concern for Europe given the number of languages spoken there, warning, “I guarantee you there are a lot of languages in Europe with no safety systems, or minimal safety systems.”166 In addition to the pervasive linguistic bias, the US companies’ products and services offered overseas are marked by a cultural and ideological bias that reflects the worldview of Silicon Valley engineers. Danielle Citron has highlighted how the architectural choices that US tech companies bake into their products reproduce largely the values held by white and Asian men steeped in the Silicon Valley mentality, with all their personal and environmental cognitive biases.

The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA's Visionary Leader George M. Low

by

Richard Jurek

Published 2 Dec 2019

“Bob went to the Langley Research Center and told them the number of people he needed,” Low said, though they would get “a few from Lewis also.”44 Initially, Gilruth had no specific assignments to fill. He had simply a proposal and a broad idea and a very enthusiastic team. Like his PARD before it, the STG operated in an environment very much like a modern-day Silicon Valley start-up—staffed with young, bright, ideological overachievers like Low, hungry to make the next big breakthrough. “George was always at the heart of the action,” Gilruth said. “I was so impressed with him that I asked him to join me in managing Project Mercury.”45 “I spent about two weeks at Langley working for Bob,” Low recalled.46 Gilruth had offered him the tantalizing job of being Faget’s deputy, working on spacecraft design and hands-on engineering.

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by

Parmy Olson

Different objectives were on track to crash into one another, driven by an almost religious zealotry on one side and an unstoppable hunger for commercial growth on the other. For now and thanks to his own personal reasons for wanting to chase AGI, Hassabis was keeping these battling ideologies at arm’s length. He was in England, living thousands of miles away from the Silicon Valley bubble, and he had surrounded himself with a team of spectacularly clever AI scientists and engineers, a team that was about to grow even larger. Hassabis resolved that he would crack the conundrum of AGI in the next five years, most likely earning a Nobel Prize along the way, according to people who worked with him.

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by

Astra Taylor

Published 4 Mar 2014

Elias Grol, “Can Twitter Go Public and Still Be a Champion of Free Speech?,” Foreign Policy, September 13, 2013. 10. See Frances Saunders, The Cultural Cold War (New York: The New Press, 2001) and the afterword to the Canongate edition of Lewis Hyde’s The Gift. 11. For the classic take on libertarianism and Silicon Valley see Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Alamut, August 1999. More recently George Packer, David Golumbia, and others have written on the topic. 12. For more on the history and funding of the Internet, see Part One and Part Four of James Curran, Natalie Fenton, and Des Freedman, Misunderstanding the Internet (London: Routledge, 2012).

Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better

by

Jennifer Pahlka

Published 12 Jun 2023

See also USSR Safari safety net Sánchez, Yadira San Francisco county court records district attorney’s office food stamp office scalability Schoolhouse Rock! schools COVID shut down and enrolling children in vaccination clinics volunteering in Schoonover, Eric Scott, Tony search engines Seattle flu study Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Sheldon, Jack Shirky, Clay Silicon Valley Single Client Database Skype Small Business Administration (SBA) small cities and towns small government ideology cost of SOAP protocol Social Security Act (1935) Social Security Administration Social Security card Social Security website software agile vs. waterfall approach and importance of government development of mission-critical speed of development, as priority solar permitting Solomon, Jake Soss, Joe Spanish-language sites Stanford University State Department state legislators states federal grants and SNAP application UI programs and steel production stewardship stimulus programs Stop Payment Alert—Claim Review items subprime mortgage crisis Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, food stamps) Table 64 Taft, William Tangherlini, Dan Tavenner, Marilyn Tavoulareas, Emily taxes automatic filing credits energy-saving rebates unpaid tax ID number tax return forms tech industry.

The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians

by

Denise Hearn

and

Vass Bednar

Published 14 Oct 2024

As Canada turns the corner on the pro-consolidation approach that has left consumers, workers, and entrepreneurs with fewer and fewer options, The Big Fix reminds us that there is more work to be done and that all Canadians will be better off for it.” – Keldon Bester, executive director of the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project “In 2014, Silicon Valley godfather Peter Thiel published a little book that dismissed competition as a destructive ideology. A decade later, Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar published a little book that shows the limits of Thiel’s notion that ‘creative monopoly’ can benefit everyone. The Big Fix succinctly describes why capitalism needs competition, how Canada lost its way, and what policymakers can do about it

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by

Michael Bhaskar

Published 2 Nov 2021

Even if you take the more positive spin on all of the above – that corporates have simply outsourced research to universities and startups – materially fewer innovative products and processes are created.18 Society itself is stuck, working against radical ideas. Despite the boosterish pronouncements of Silicon Valley gurus, we are hostile to breakthroughs, more conservative, cautious, rule-bound, anti-maverick, return-oriented, ideologically blinkered and short-sighted than we might think. There are no easy answers to the question of how this could change, which is why the social context weighs so heavily on the future, compounding the Idea Paradox. Bell isn't unique.

The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work

by

David Frayne

Published 15 Nov 2015

Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets

by

Brett Scott

Published 4 Jul 2022

The Future of Technology

by

Tom Standage

Published 31 Aug 2005

Luckily for it companies, there is one customer that is spending more now than it did during the internet bubble: government. And that is only one of the reasons why the it industry is becoming more involved in Washington, dc. 31 THE FUTURE OF TECHNOLOGY Regulating rebels Despite its libertarian ideology, the IT industry is becoming increasingly involved in the machinery of government ven among the generally libertarian Silicon Valley crowd, T.J. Rodgers stands out. In early 2000, when everybody else was piling into the next red-hot initial public offering, the chief executive of Cypress Semiconductor, a chipmaker, declared that it would not be appropriate for the high-tech industry to normalise its relations with government.

Geek Sublime: The Beauty of Code, the Code of Beauty

by

Vikram Chandra

Published 7 Nov 2013

Ibid., 813. 33. Barrett, “Why We Don’t Hire .NET Programmers.” 34. Ibid. 35. Ibid. 36. Solnit, “Diary.” 37. Ibid. 38. See Lacy, “And You Thought SF Cabs Were Bad? BART Strike Is Crippling Fledgling Mid-Market Tech Corridor.” 39. Silver, “In Silicon Valley, Technology Talent Gap Threatens G.O.P. Campaigns.” 40. Barbrook and Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” 44. 41. Ibid., 55. 42. Matyszczyk, “Woz: Microsoft Might Be More Creative Than Apple.” 43. Torvalds, “Re: Stable Linux 2.6.25.10”; Leonard, “Let My Software Go!”; Raymond, “Microsoft Tries to Recruit Me.” 44. Bailey, “Dear Open Source Project Leader: Quit Being a Jerk.” 45.

From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

by

Fred Turner

Published 31 Aug 2006

In the case of Stewart Brand and others associated with the Whole Earth Catalog, so too did a series of social networks, a set of reputations, and a series of social and rhetorical tactics for bringing communities together and facilitating the articulation of their interests. Over the next twenty years, Brand’s cultural credibility and his networking skills allowed him to transform the lingering ideals of the New Communalists into ideological resources for the technologists of the computer and software industries in what had begun to be called Silicon Valley. This process took place alongside two dramatic shifts in computer technology: miniaturization and networking. By the early 1970s, computing power that had formerly been available only to those with access to massive mainframes had been fit into desktop boxes.

The People vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (And How We Save It)

by

Jamie Bartlett

Published 4 Apr 2018

The Gig Economy: A Critical Introduction

by

Jamie Woodcock

and

Mark Graham

Published 17 Jan 2020

However, globalization has not only meant the shifting of work and trade to different parts of the world, but also brought about a generalization of what Barbrook and Cameron (1996) have termed the ‘Californian Ideology’, referring to the encouragement of deregulated markets and powerful transnational corporations. While this is often linked to the rise of ‘cognitive capitalism’ (Moulier-Boutang, 2012) and the companies creating the software and platforms in Silicon Valley, it increasingly becomes a driver to open up markets in low- and middle-income countries too. Alongside this ideological globalization, there has been a spread of common or shared technological infrastructures. For example, the IP addressing system, Visa/Mastercard/Amex (as well as new mobile) payment platforms, the GPS system, Google Maps as a base layer, and the Apple and Google Android phone operating systems, allow an increased internationalization of working practices.

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by

Bruce Nussbaum

Published 5 Mar 2013

Life After Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy

by

George Gilder

Published 16 Jul 2018

Meanwhile, these delusions of omnipotence have not prevented the eclipse of its initial public offering market, the antitrust tribulations of its champion companies led by Google, and the profitless prosperity of its hungry herds of “unicorns,” as they call private companies worth more than one billion dollars. Capping these setbacks is Silicon Valley’s loss of entrepreneurial edge in IPOs and increasingly in venture capital to nominal communists in China. In defense, Silicon Valley seems to have adopted what can best be described as a neo-Marxist political ideology and technological vision. You may wonder how I can depict as “neo-Marxists” those who on the surface seem to be the most avid and successful capitalists on the planet. Marxism is much discussed as a vessel of revolutionary grievances, workers’ uprisings, divestiture of chains, critiques of capital, catalogs of classes, and usurpation of the means of production.

Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart Contracts

by

David Gerard

Published 23 Jul 2017

Kings of Crypto: One Startup's Quest to Take Cryptocurrency Out of Silicon Valley and Onto Wall Street

by

Jeff John Roberts

Published 15 Dec 2020

The one-time startup was applying for a federal bank charter, a powerful license that would open the door to offering FDIC-insured deposits and give Coinbase direct access to the Federal Reserve. Without realizing it, the two leaders, seemingly as far apart ideologically as their offices were geographically, had been moving toward each other. By 2019, the worlds of Wall Street and Silicon Valley were suddenly not so far apart. Coinbase had spent the year playing catch up to Binance. But, “in the long term, it’s not Coinbase versus Binance,” says Barry Silbert, the early Coinbase investor and bitcoin billionaire. “It’s Coinbase versus JP Morgan.”

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by

Brink Lindsey

Published 12 Oct 2017

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by

Mariana Mazzucato

Published 1 Jan 2011

This Machine Kills Secrets: Julian Assange, the Cypherpunks, and Their Fight to Empower Whistleblowers

by

Andy Greenberg

Published 12 Sep 2012

Anti-Vietnam War protesters burned down the Bank of America in the neighboring college town of Isla Vista. But May largely went about his work, graduated, and took a job beside his fellow physics geniuses at Intel. May’s time at Intel was less a career than a few years’ detour from his ideological wanderings. After his alpha particle victory and disillusionment with the world of business, he would retire and retreat from Silicon Valley, over the hills to his own personal Galt’s Gulch, a two-story house a mile from the beach in Aptos, California, with only his cat, Nietzsche. In his new life of aimless intellectual exploration, May would walk down to the beach every day with a stack of business, science, and technology magazines, academic papers, and science fiction novels, and greedily consume them until the sun set.

The Charisma Machine: The Life, Death, and Legacy of One Laptop Per Child

by

Morgan G. Ames

Published 19 Nov 2019

Who Owns the Future?

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 6 May 2013

One example is when investors are perfectly confident to value a Siren Server that accumulates data about people in the tens of billions of dollars, no matter how remote the possibility of an actual business plan that would make a commensurate amount of profit. And yet, at the same time, these same investors can’t imagine that the people who are the sole sources of what is so valuable can have any value. And then there are ideological pundits from the sidelines who strike out at anyone who points out the absurdities of what we’re up to in Silicon Valley lately. If someone complains that all those brilliant recent PhDs ought to perhaps be working on something more substantive than putting yet more paid links in front of people, you can expect a rigorous defense of the nonmonetary value being created by today’s cloud computing.

The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power

by

Jacob Helberg

Published 11 Oct 2021

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 1 Mar 2015

Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts

by

Jill Abramson

Published 5 Feb 2019

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

by

Benjamin H. Bratton

Published 19 Feb 2016

For those unfamiliar, Survival Research Laboratories is a Bay Area-based “industrial performing arts” collective famous for its pyrotechnic displays of machinic mayhem and which might typify a DIY engineering ethic often associated with the “California Ideology,” whereas Page Mill Road in Palo Alto (and Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park) have housed important clusters of important Silicon Valley venture capital firms. 21. Nick Whitford-Dyer, “Red Plenty Platforms,” Culture Machine 14 (2013): 1–27, and Tiziana Terranova, “Red Stack Attack!” in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, ed. Robin Mackay and Armen Avanessian (Falmouth, Cornwall: Urbanomic and Merve Verlag, 2014), 379–400, both make explicit connections between Spufford's version of cybernetic planning, contemporary computing platforms, and my Stack thesis.

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by

Malcolm Harris

Published 14 Feb 2023

Both parties agreed that it was time for the capitalist class to take a real Cold War victory lap, and with the exception of the perennially frustrating Social Security privatization, the Hoover agenda was law once more. What about the tech companies? Given Al Gore’s personal support for the high-tech industry—as a congressman, he led the push for the civilian supercomputer infrastructure—one might imagine that Bush had to write off support from Silicon Valley, but not so. The Weekly Standard detailed the campaign’s regional push in 2000.5 The Bush campaign relied on ideologically committed executives to wrangle their fellows, and the team split its appeals by generation. For those under forty, there was Gregory Slayton, an energetic, wild-eyed evangelical Christian with a circle beard and a baseball cap who made millions selling a company to Silicon Graphics and was then CEO of an email marketing company called ClickAction that, naturally, contracted with GOP campaigns.