Silicon Valley startup

description: a new business venture based in Silicon Valley, often in the tech or digital sector, aiming for rapid growth and, frequently, a lucrative exit strategy

169 results

The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

by Kevin Kelly · 6 Jun 2016 · 371pp · 108,317 words

performance (ECG), oxygen level, temperature, and skin conductance all in a single instant. Someday it will also measure your glucose levels. More than one startup in Silicon Valley is developing a noninvasive, prickless blood monitor to analyze your blood factors daily. You’ll eventually wear these. By taking this information and feeding it

Why Startups Fail: A New Roadmap for Entrepreneurial Success

by Tom Eisenmann · 29 Mar 2021 · 387pp · 106,753 words

the venture’s team] ending with a shitty Skype chat where we were told we just weren’t good enough to work with the successful Silicon Valley startup in our space.” But despite all the factors that encourage an early-stage founder to delay a shutdown, there are also countervailing forces at work

…

Benefit Seniors Aging in Place?” TechForAging website, Dec. 1, 2019, describes several social robots designed for elder care. For example, team members: Jerry Kaplan, Startup: A Silicon Valley Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994), recounts GO Corp’s history; Kaplan was the startup’s CEO. “The company was dependent”: Author’s email correspondence with

…

Yang, “GO Corp,” HBS case 297021, Sept. 2016 (Apr. 2017 rev.). Facts in the next paragraph about GO Corp’s failure are from Jerry Kaplan, Startup: A Silicon Valley Adventure (New York: Penguin, 1994), Ch. 13. Iridium’s satellite phones: Bloom, Eccentric Orbits, p. 180. To illustrate the last point: Frederick Brooks, The

…

inhibit learning in ways that reduce success odds with novel ventures. Elizabeth Holmes is an example: John Carreyrou, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (New York: Knopf, 2018), p. 43. To confront this problem: Blumberg, Startup CEO, Ch. 37. For additional guidance on best practices for managing a board

Company of One: Why Staying Small Is the Next Big Thing for Business

by Paul Jarvis · 1 Jan 2019 · 258pp · 74,942 words

’s swim and basketball teams on some days and then work in the evenings instead. Miranda made her first foray into a postschool career with startups in Silicon Valley. While she enjoyed the friendships, travel, and community these jobs gave her, she also found herself hitting a glass ceiling fairly hard. Although the

The Great Fragmentation: And Why the Future of All Business Is Small

by Steve Sammartino · 25 Jun 2014 · 247pp · 81,135 words

is now being reversed. If the product is amazing, is advertising really needed? Just ask Elon Musk of Tesla Motors. Tesla Motors is a Silicon Valley–based auto startup that makes all-electric vehicles. Tesla has no advertising, no agency and no chief marketing officer and it has no plans to run television

…

a new car company can’t compete with the more than 100 years of expertise of Ford, General Motors (GM) and others? Surely a startup from Silicon Valley that’s never built real hardware — American steel — and only ever messed around with 1s and 0s can’t build a car that could be

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by Gabriel Weinberg and Lauren McCann · 17 Jun 2019

wrote in his 2014 book, Zero to One: Great companies can be built on open but unsuspected secrets about how the world works. Consider the Silicon Valley startups that have harnessed the spare capacity that is all around us but often ignored. Before Airbnb, travelers had little choice but to pay high prices

The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

by Eric Ries · 13 Sep 2011 · 278pp · 83,468 words

. They had raised venture capital from well-regarded investors, had built an awesome team, and were fresh off an impressive debut at one of Silicon Valley’s famous startup competitions. They were extremely process-oriented and disciplined. Their product development followed a rigorous version of the agile development methodology known as Extreme Programming

…

, either because of personal fame or because they are operating as part of a famous brand, face an extreme version of this problem. A new startup in Silicon Valley called Path was started by experienced entrepreneurs: Dave Morin, who previously had overseen Facebook’s platform initiative; Dustin Mierau, product designer and cocreator of

Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China's ByteDance

by Matthew Brennan · 9 Oct 2020 · 282pp · 63,385 words

YC at nine pm this Friday.” This was the mysterious message sent out to all 43 startup teams taking part in the 2011 Y Combinator startup accelerator, Silicon Valley’s most prestigious program for new startups. The cryptic announcement from the program partners drove wild speculation amongst the founders as to what would

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power

by Max Chafkin · 14 Sep 2021 · 524pp · 130,909 words

classmates and a Facebook cofounder, Chris Hughes—“The Kid Who Made Obama President,” Fast Company claimed. Some were calling 2008 the “Facebook Election,” and Silicon Valley’s startup elite contributed so heavily to Obama’s campaign that the Atlantic termed the campaign “the year’s hottest start-up.” Never had Thiel seemed more

…

contacts, was the Total Information Awareness program. Officially, Poindexter’s concept had been killed, but Bowden argued that the basic approach survived, helped along by Silicon Valley. “A startup called Palantir, for instance, came up with a program that elegantly accomplished what TIA had set out to do,” he wrote. “The software produced

…

support of Donald Trump at the 2016 Republican National Convention. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book grew out of fifteen years of reporting on the world of Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurs, startups, and investors. Jane Berentson gave me my first opportunity in journalism, as a fact-checker at Inc., and convinced me that business writing need

The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley

by Leslie Berlin · 9 Jun 2005

Arthur Rock’s and Bud Coyle’s work in the establishment of Fairchild Semiconductor in many ways presaged the role of venture capitalists in future Silicon Valley startup operations, even though the term “venture capital” did not yet exist. The bankers helped the young technologists develop a business strategy, determine their funding requirements

The Immigrant Exodus: Why America Is Losing the Global Race to Capture Entrepreneurial Talent

by Vivek Wadhwa · 1 Oct 2012 · 103pp · 24,033 words

China, a prestigious post that positioned him for a top executive position in the company. Rather than remain in the Oracle fold or launch a startup in Silicon Valley, Liang chose to build his business in China. People like Liang—expats who return home—are called “sea turtles” in China. Generally people of

…

,” showed a rapid rise in the number of immigrant entrepreneurs even over the previous decade.21 In our survey, more than half (52.4%) of Silicon Valley startups had one or more immigrants as a key founder, compared with the California average of 38.8%. A comparison with Saxenian’s 1999 findings showed

…

far more tech startups. Indian immigrants outpaced their Chinese counterparts as founders of engineering and technology companies in Silicon Valley. Saxenian reported that 17% of Silicon Valley startups from 1980 to 1998 had a Chinese founder and 7% had an Indian founder. We found that from 1995 to 2005, Indians were key founders

…

of 13.4% of all Silicon Valley startups, and immigrants from China and Taiwan were key founders in 12.8%. The outsized impact of Indian founders was logical. Between 1990 and 2000, the

…

could not start up in the United States. Santiago cannot compete with Silicon Valley yet. The program has had a number of high-profile startups decamp for Silicon Valley (such as Babelverse and CruiseWise). But few would argue that Chile could one day grow into a viable competitor to Silicon Valley. And only

Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War

by Raj M. Shah and Christopher Kirchhoff · 8 Jul 2024 · 272pp · 103,638 words

No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram

by Sarah Frier · 13 Apr 2020 · 484pp · 114,613 words

Masters of Scale: Surprising Truths From the World's Most Successful Entrepreneurs

by Reid Hoffman, June Cohen and Deron Triff · 14 Oct 2021 · 309pp · 96,168 words

The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

by Sebastian Mallaby · 1 Feb 2022 · 935pp · 197,338 words

The Launch Pad: Inside Y Combinator, Silicon Valley's Most Exclusive School for Startups

by Randall Stross · 4 Sep 2013 · 332pp · 97,325 words

Rule of the Robots: How Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Everything

by Martin Ford · 13 Sep 2021 · 288pp · 86,995 words

We Are the Nerds: The Birth and Tumultuous Life of Reddit, the Internet's Culture Laboratory

by Christine Lagorio-Chafkin · 1 Oct 2018

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon

by Brad Stone · 14 Oct 2013 · 380pp · 118,675 words

That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea

by Marc Randolph · 16 Sep 2019 · 334pp · 102,899 words

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber

by Mike Isaac · 2 Sep 2019 · 444pp · 127,259 words

Super Founders: What Data Reveals About Billion-Dollar Startups

by Ali Tamaseb · 14 Sep 2021 · 251pp · 80,831 words

The Great Race: The Global Quest for the Car of the Future

by Levi Tillemann · 20 Jan 2015 · 431pp · 107,868 words

The Startup Way: Making Entrepreneurship a Fundamental Discipline of Every Enterprise

by Eric Ries · 15 Mar 2017 · 406pp · 105,602 words

Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire

by Brad Stone · 10 May 2021 · 569pp · 156,139 words

The Monk and the Riddle: The Education of a Silicon Valley Entrepreneur

by Randy Komisar · 15 Mar 2000 · 385pp · 48,143 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by Roger McNamee · 1 Jan 2019 · 382pp · 105,819 words

The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers

by Ben Horowitz · 4 Mar 2014 · 270pp · 79,068 words

Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play

by Morgan Ramsay and Peter Molyneux · 28 Jul 2011 · 500pp · 146,240 words

Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think

by Viktor Mayer-Schonberger and Kenneth Cukier · 5 Mar 2013 · 304pp · 82,395 words

Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley

by Antonio Garcia Martinez · 27 Jun 2016 · 559pp · 155,372 words

Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City

by Brad Feld · 8 Oct 2012 · 169pp · 56,250 words

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

by Adam Grant · 2 Feb 2016 · 410pp · 101,260 words

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

by Peter Thiel and Blake Masters · 15 Sep 2014 · 185pp · 43,609 words

Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success

by Shane Snow · 8 Sep 2014 · 278pp · 70,416 words

The Upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb, and the Killer Companies of the New Silicon Valley Are Changing the World

by Brad Stone · 30 Jan 2017 · 373pp · 112,822 words

Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers

by Timothy Ferriss · 6 Dec 2016 · 669pp · 210,153 words

How to Build a Billion Dollar App: Discover the Secrets of the Most Successful Entrepreneurs of Our Time

by George Berkowski · 3 Sep 2014 · 468pp · 124,573 words

AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

by Kai-Fu Lee · 14 Sep 2018 · 307pp · 88,180 words

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup

by John Carreyrou · 20 May 2018 · 359pp · 110,488 words

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

Exponential Organizations: Why New Organizations Are Ten Times Better, Faster, and Cheaper Than Yours (And What to Do About It)

by Salim Ismail and Yuri van Geest · 17 Oct 2014 · 292pp · 85,151 words

Troublemakers: Silicon Valley's Coming of Age

by Leslie Berlin · 7 Nov 2017 · 615pp · 168,775 words

The New Geography of Jobs

by Enrico Moretti · 21 May 2012 · 403pp · 87,035 words

How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars: The Snapchat Story

by Billy Gallagher · 13 Feb 2018 · 359pp · 96,019 words

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

Who Owns the Future?

by Jaron Lanier · 6 May 2013 · 510pp · 120,048 words

The Simulation Hypothesis

by Rizwan Virk · 31 Mar 2019 · 315pp · 89,861 words

Uncanny Valley: A Memoir

by Anna Wiener · 14 Jan 2020 · 237pp · 74,109 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

Ludicrous: The Unvarnished Story of Tesla Motors

by Edward Niedermeyer · 14 Sep 2019 · 328pp · 90,677 words

I'm Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59

by Douglas Edwards · 11 Jul 2011 · 496pp · 154,363 words

Kings of Crypto: One Startup's Quest to Take Cryptocurrency Out of Silicon Valley and Onto Wall Street

by Jeff John Roberts · 15 Dec 2020 · 226pp · 65,516 words

The Big Score

by Michael S. Malone · 20 Jul 2021

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

The Cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion

by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell · 19 Jul 2021 · 460pp · 130,820 words

Tech Titans of China: How China's Tech Sector Is Challenging the World by Innovating Faster, Working Harder, and Going Global

by Rebecca Fannin · 2 Sep 2019 · 269pp · 70,543 words

Power Play: Tesla, Elon Musk, and the Bet of the Century

by Tim Higgins · 2 Aug 2021 · 430pp · 135,418 words

Founders at Work: Stories of Startups' Early Days

by Jessica Livingston · 14 Aug 2008 · 468pp · 233,091 words

Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making

by Tony Fadell · 2 May 2022 · 411pp · 119,022 words

Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in This Life and Beyond

by Tamara Kneese · 14 Aug 2023 · 284pp · 75,744 words

Ask Your Developer: How to Harness the Power of Software Developers and Win in the 21st Century

by Jeff Lawson · 12 Jan 2021 · 282pp · 85,658 words

Your Face Belongs to Us: A Secretive Startup's Quest to End Privacy as We Know It

by Kashmir Hill · 19 Sep 2023 · 487pp · 124,008 words

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by Anu Bradford · 25 Sep 2023 · 898pp · 236,779 words

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by Keach Hagey · 19 May 2025 · 439pp · 125,379 words

Startupland: How Three Guys Risked Everything to Turn an Idea Into a Global Business

by Mikkel Svane and Carlye Adler · 13 Nov 2014 · 220pp

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by Karen Hao · 19 May 2025 · 660pp · 179,531 words

Wonder Boy: Tony Hsieh, Zappos, and the Myth of Happiness in Silicon Valley

by Angel Au-Yeung and David Jeans · 25 Apr 2023 · 427pp · 134,098 words

Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology From Capitalism

by Wendy Liu · 22 Mar 2020 · 223pp · 71,414 words

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by Nicole Kobie · 3 Jul 2024 · 348pp · 119,358 words

Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech

by Sara Wachter-Boettcher · 9 Oct 2017 · 223pp · 60,909 words

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by Nate Silver · 12 Aug 2024 · 848pp · 227,015 words

Design for Hackers: Reverse Engineering Beauty

by David Kadavy · 5 Sep 2011 · 276pp · 78,094 words

Nobody's Fool: Why We Get Taken in and What We Can Do About It

by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris · 10 Jul 2023 · 338pp · 104,815 words

The Founders: The Story of Paypal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

by Jimmy Soni · 22 Feb 2022 · 505pp · 161,581 words

Life After Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy

by George Gilder · 16 Jul 2018 · 332pp · 93,672 words

Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness

by Frederic Laloux and Ken Wilber · 9 Feb 2014 · 436pp · 141,321 words

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by Jaron Lanier · 21 Nov 2017 · 480pp · 123,979 words

Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

by Jerry Kaplan · 3 Aug 2015 · 237pp · 64,411 words

Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI

by Paul R. Daugherty and H. James Wilson · 15 Jan 2018 · 523pp · 61,179 words

Lab Rats: How Silicon Valley Made Work Miserable for the Rest of Us

by Dan Lyons · 22 Oct 2018 · 252pp · 78,780 words

Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World

by Christopher Steiner · 29 Aug 2012 · 317pp · 84,400 words

Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It's Doing to Us

by Will Storr · 14 Jun 2017 · 431pp · 129,071 words

Rationality: From AI to Zombies

by Eliezer Yudkowsky · 11 Mar 2015 · 1,737pp · 491,616 words

A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas

by Warren Berger · 4 Mar 2014 · 374pp · 89,725 words

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by Walter Isaacson · 6 Oct 2014 · 720pp · 197,129 words

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader

by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli · 24 Mar 2015 · 464pp · 155,696 words

Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley's Bill Campbell

by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg and Alan Eagle · 15 Apr 2019 · 199pp · 56,243 words

The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter

by David Sax · 8 Nov 2016 · 360pp · 101,038 words

Your Computer Is on Fire

by Thomas S. Mullaney, Benjamin Peters, Mar Hicks and Kavita Philip · 9 Mar 2021 · 661pp · 156,009 words

Side Hustle: From Idea to Income in 27 Days

by Chris Guillebeau · 18 Sep 2017 · 206pp · 60,587 words

Whistleblower: My Journey to Silicon Valley and Fight for Justice at Uber

by Susan Fowler · 18 Feb 2020 · 205pp · 71,872 words

Please Report Your Bug Here: A Novel

by Josh Riedel · 17 Jan 2023 · 287pp · 85,518 words

Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley From Building a New Global Underclass

by Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri · 6 May 2019 · 346pp · 97,330 words

Decoding the World: A Roadmap for the Questioner

by Po Bronson · 14 Jul 2020 · 320pp · 95,629 words

House of Huawei: The Secret History of China's Most Powerful Company

by Eva Dou · 14 Jan 2025 · 394pp · 110,159 words

Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference

by Bregman, Rutger · 9 Mar 2025 · 181pp · 72,663 words

The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class

by Joel Kotkin · 11 May 2020 · 393pp · 91,257 words

Joel on Software

by Joel Spolsky · 1 Aug 2004 · 370pp · 105,085 words

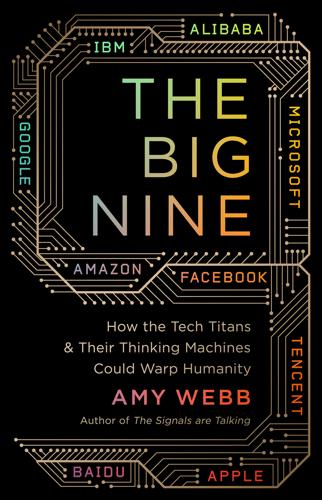

The Big Nine: How the Tech Titans and Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity

by Amy Webb · 5 Mar 2019 · 340pp · 97,723 words

Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World

by Clive Thompson · 26 Mar 2019 · 499pp · 144,278 words

Platform Capitalism

by Nick Srnicek · 22 Dec 2016 · 116pp · 31,356 words

Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets From Inside Amazon

by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr · 9 Feb 2021 · 302pp · 100,493 words

Calling Bullshit: The Art of Scepticism in a Data-Driven World

by Jevin D. West and Carl T. Bergstrom · 3 Aug 2020

Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech

by Jamie Susskind · 3 Sep 2018 · 533pp

Likewar: The Weaponization of Social Media

by Peter Warren Singer and Emerson T. Brooking · 15 Mar 2018

Hope Dies Last: Visionary People Across the World, Fighting to Find Us a Future

by Alan Weisman · 21 Apr 2025 · 599pp · 149,014 words

Battle for the Bird: Jack Dorsey, Elon Musk, and the $44 Billion Fight for Twitter's Soul

by Kurt Wagner · 20 Feb 2024 · 332pp · 127,754 words

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, From Home Renovations to Space Exploration

by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner · 16 Feb 2023 · 353pp · 97,029 words

Late Bloomers: The Power of Patience in a World Obsessed With Early Achievement

by Rich Karlgaard · 15 Apr 2019 · 321pp · 92,828 words

Habeas Data: Privacy vs. The Rise of Surveillance Tech

by Cyrus Farivar · 7 May 2018 · 397pp · 110,222 words

Final Jeopardy: Man vs. Machine and the Quest to Know Everything

by Stephen Baker · 17 Feb 2011 · 238pp · 77,730 words

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna · 23 May 2016 · 437pp · 113,173 words

Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

by Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace · 23 Jul 2009 · 325pp · 110,330 words

The Airbnb Story: How Three Ordinary Guys Disrupted an Industry, Made Billions...and Created Plenty of Controversy

by Leigh Gallagher · 14 Feb 2017 · 290pp · 87,549 words

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by Evgeny Morozov · 15 Nov 2013 · 606pp · 157,120 words

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by Margaret O'Mara · 8 Jul 2019

The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning With the Myth of the Good Billionaire

by Tim Schwab · 13 Nov 2023 · 618pp · 179,407 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by Edward Fishman · 25 Feb 2025 · 884pp · 221,861 words

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power

by Jacob Helberg · 11 Oct 2021 · 521pp · 118,183 words

Women Leaders at Work: Untold Tales of Women Achieving Their Ambitions

by Elizabeth Ghaffari · 5 Dec 2011 · 493pp · 139,845 words

Intertwingled: Information Changes Everything

by Peter Morville · 14 May 2014 · 165pp · 50,798 words

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by Gary Gerstle · 14 Oct 2022 · 655pp · 156,367 words

Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms and the Corruption of Justice

by David Enrich · 5 Oct 2022 · 373pp · 108,788 words

Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing

by Peter Robison · 29 Nov 2021 · 382pp · 105,657 words

On the Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did to Me and How It Drives America Insane

by Emily Guendelsberger · 15 Jul 2019 · 382pp · 114,537 words

eBoys

by Randall E. Stross · 30 Oct 2008 · 381pp · 112,674 words

Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War

by P. W. Singer and August Cole · 28 Jun 2015 · 537pp · 149,628 words

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by Ed Finn · 10 Mar 2017 · 285pp · 86,853 words

@War: The Rise of the Military-Internet Complex

by Shane Harris · 14 Sep 2014 · 340pp · 96,149 words

Pinpoint: How GPS Is Changing Our World

by Greg Milner · 4 May 2016 · 385pp · 103,561 words

Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace

by Ronald J. Deibert · 13 May 2013 · 317pp · 98,745 words

Geek Sublime: The Beauty of Code, the Code of Beauty

by Vikram Chandra · 7 Nov 2013 · 239pp · 64,812 words

97 Things Every Programmer Should Know

by Kevlin Henney · 5 Feb 2010 · 292pp · 62,575 words

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by Harold James · 15 Jan 2023 · 469pp · 137,880 words

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

by Kenneth Rogoff · 27 Feb 2025 · 330pp · 127,791 words

The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich

by Timothy Ferriss · 1 Jan 2007 · 426pp · 105,423 words

How to Do Nothing

by Jenny Odell · 8 Apr 2019 · 243pp · 76,686 words

The Content Trap: A Strategist's Guide to Digital Change

by Bharat Anand · 17 Oct 2016 · 554pp · 149,489 words

Hidden Figures

by Margot Lee Shetterly · 11 Aug 2016 · 425pp · 116,409 words

Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero

by Tyler Cowen · 8 Apr 2019 · 297pp · 84,009 words

Framers: Human Advantage in an Age of Technology and Turmoil

by Kenneth Cukier, Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Francis de Véricourt · 10 May 2021 · 291pp · 80,068 words

Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution

by Fred Vogelstein · 12 Nov 2013 · 275pp · 84,418 words

That Used to Be Us

by Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum · 1 Sep 2011 · 441pp · 136,954 words

The Power Surge: Energy, Opportunity, and the Battle for America's Future

by Michael Levi · 28 Apr 2013

Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth

by Stuart Ritchie · 20 Jul 2020

Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science

by Michael Nielsen · 2 Oct 2011 · 400pp · 94,847 words

May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases—And What We Can Do About It

by Alex Edmans · 13 May 2024 · 315pp · 87,035 words

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality

by Don Watkins and Yaron Brook · 28 Mar 2016 · 345pp · 92,849 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

by Adam Fisher · 9 Jul 2018 · 611pp · 188,732 words

The Inmates Are Running the Asylum

by Alan Cooper · 24 Feb 2004 · 193pp · 98,671 words

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Mine!: How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives

by Michael A. Heller and James Salzman · 2 Mar 2021 · 332pp · 100,245 words

The Enablers: How the West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption - Endangering Our Democracy

by Frank Vogl · 14 Jul 2021 · 265pp · 80,510 words

Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies

by Barry Meier · 17 May 2021 · 319pp · 89,192 words

The Driving Machine: A Design History of the Car

by Witold Rybczynski · 8 Oct 2024 · 187pp · 65,740 words

Off the Edge: Flat Earthers, Conspiracy Culture, and Why People Will Believe Anything

by Kelly Weill · 22 Feb 2022

Climate Change

by Joseph Romm · 3 Dec 2015 · 358pp · 93,969 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

E=mc2: A Biography of the World's Most Famous Equation

by David Bodanis · 25 May 2009 · 349pp · 27,507 words

Better, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline . . . And the Rise of a New Economy

by Daniel Gross · 7 May 2012 · 391pp · 97,018 words

Space 2.0

by Rod Pyle · 2 Jan 2019 · 352pp · 87,930 words

Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets

by John McMillan · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 103,988 words

The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman

by Timothy Ferriss · 1 Dec 2010 · 836pp · 158,284 words

American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History

by Casey Michel · 23 Nov 2021 · 466pp · 116,165 words

The Bin Ladens: An Arabian Family in the American Century

by Steve Coll · 29 Mar 2009 · 769pp · 224,916 words