Snapchat

description: an American multimedia instant messaging app and service

321 results

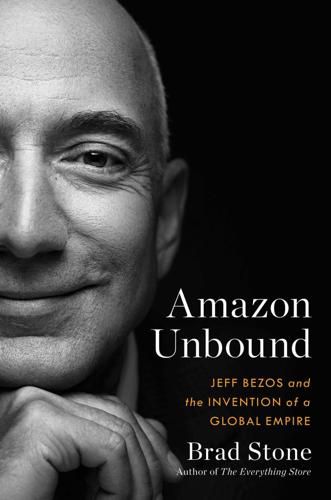

How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars: The Snapchat Story

by

Billy Gallagher

Published 13 Feb 2018

New York Times, December 31, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/31/business/media/Snapchat-Plans-a-Global-View-of-New-Years-Festivities.html Webster, Andrew. “Snapchat’s Geofilters Are Now Open to Everyone.” Verge, December 2, 2014. https://www.theverge.com/2014/12/2/7319317/snapchat-geofilters-community Chapter Twenty-Two: “We Need to Make Money” “Advertising on Snapchat.” Snapchat, October 17, 2014. https://www.snap.com/en-US/news/post/advertising-on-snapchat/. Carr, Austin. “Inside Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel’s Entertainment Empire.” Fast Company, October 19, 2015. https://www.fastcompany.com/3051612/media-tech-and-advertising-to-snapchat-i-aint-afraid-of-no-ghost Chemi, Eric.

…

Instagram warned users not to use “links asking you to add someone on another service.” This behavior attempted to slow Snapchat’s growth and served to continue the pissing contest Snapchat and Facebook had been having for years; early on after Snapchat released geofilters, they had placed a geofilter over Facebook’s campus featuring the Snapchat ghost pointing and laughing. As for Twitter, Snapchat didn’t even bother fighting back, as Snapchat passed Twitter in daily active users (150 million to 140 million) in June 2016. In August 2016, Instagram released Instagram Stories, a new feature essentially copying Snapchat Stories that let users post photo and video slideshows that disappeared after twenty-four hours.

…

Memories’s permanence was antithetical to Snapchat’s core ethos, but it was released late enough that users’ behaviors and norms were already well established. Had Snapchat released Memories in 2012, it may have been a disaster that cut into Snapchat’s real-time, fleeting nature. But because Snapchat already had hundreds of millions of users snapping for years before it released Memories, it was able to add to the product without changing core behaviors. Memories makes Snapchat’s camera even more useful, as it lets users store photos, videos, their own Snapchat stories in their entirety—indeed, their memories—all on Snapchat’s servers rather than taking up space on their phone. It is another step toward making Snapchat people’s default camera.

No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram

by

Sarah Frier

Published 13 Apr 2020

Colao, “Snapchat: The Biggest No-Revenue Mobile App Since Instagram,” Forbes, November 27, 2012, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2012/11/27/snapchat-the-biggest-no-revenue-mobile-app-since-instagram/#6ef95f0a7200. By November 2012, Snapchat: Colao, “Snapchat.” “Thanks :) would be happy… Bay Area,”: Alyson Shontell, “How Snapchat’s CEO Got Mark Zuckerberg to Fly to LA for Private Meeting,” Business Insider, January 6, 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/evan-spiegel-and-mark-zuckerbergs-emails-2014-1?IR=T. He spent the meeting insinuating: J. J. Colao, “The Inside Story of Snapchat: The World’s Hottest App or a $3 Billion Disappearing Act?

…

Warr would ask the research subjects. “Probably Snapchat,” they responded. * * * In all of its Snapchat copycatting, Facebook was forced to learn, over and over, that just because it had made one world-changing product didn’t mean it could succeed with another, even when that product was a replica of something already popular. Snapchat, meanwhile, learned that it could ignore Facebook’s repeated attacks. In fact, Facebook was so apparently unthreatening during this period that a Snapchat executive proposed trying something crazy: being friends. Snapchat’s best asset and biggest problem was Evan Spiegel himself.

…

,” Forbes, January 20, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2014/01/06/the-inside-story-of-snapchat-the-worlds-hottest-app-or-a-3-billion-disappearing-act/. And then, starting the next day: Seth Fiegerman, “Facebook Poke Falls Out of Top 25 Apps as Snapchat Hits Top 5,” Mashable, December 26, 2012, https://mashable.com/2012/12/26/facebook-poke-app-ranking/. Snapchat’s downloads climbed: Fiegerman, “Facebook Poke Falls Out of Top 25 Apps.” In June 2013, Spiegel raised: Mike Isaac, “Snapchat Closes $60 Million Round Led by IVP, Now at 200 Million Daily Snaps,” All Things D, June 24, 2013, http://allthingsd.com/20130624/snapchat-closes-60-million-round-led-by-ivp-now-at-200-million-daily-snaps/.

Crushing It!: How Great Entrepreneurs Build Their Business and Influence—and How You Can, Too

by

Gary Vaynerchuk

Published 30 Jan 2018

Less than a year later, 40 percent of American teenagers were using Snapchat daily. I learned an important lesson from that bad call on Snapchat: a devoted, sticky fan base is willing to be patient as you experiment your way to the next iteration. The next big launch, Discover, saw Snapchat graduate into a bona fide media platform by offering a page where users would find a slew of brands like National Geographic, T-Mobile, and ESPN. Snapchat now had access to advertising revenue, and that meant so did anyone who could crack the Snapchat code. The man who did that is named DJ Khaled, but before I introduce him, we’re going to reminisce about Ashton Kutcher.

…

Same with Kerry and Jayde Robinson’s salon talk. That means that to be a Snapchat influencer, you need to be strong on the other platforms as well. The content you produce for Snapchat has to be powerful enough to draw views on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram. The way to get discovered on Snapchat is not much different from the way television stations try to get people to tune in to their programs, which is to market in all the other places where people who might be interested in you are already going. That’s what I did. I was never concerned by the lack of discoverability on Snapchat, because I could see that all I had to do was draw awareness to it through my base on Twitter, YouTube, and my website.

…

If there’s one thing Shaun had learned from his jewelry-boutique experiment, it’s that he was good at creating safe online communities where people could come together to engage and have fun. “The greatest challenge was trying to grow on a platform that did not cater to growth. Snapchat was a communication platform, like text messaging, so I had to make it into a content-creating platform. Eventually, Snapchat made updates, which helped with that, but I had to get creative at first.” There’s a reason Shaun’s content got so much attention when so many others on Snapchat did not: he treated Snapchat like a business. Many people start pumping out cool content onto a platform and just hope they’ll get noticed and grow their audience enough that brands will come calling.

How to Build a Billion Dollar App: Discover the Secrets of the Most Successful Entrepreneurs of Our Time

by

George Berkowski

Published 3 Sep 2014

, article on GIGAOM.com, 29 April 2013, gigaom.com/2013/04/29/chat-apps-have-overtaken-sms-by-message-volume/. 22 Interview with Jan Koum, 20 January 2014, op. cit. 23 J. J. Colao, ‘Snapchat: The Biggest No-Revenue Mobile App Since Instagram’, article on Forbes.com, 27 November 2012, www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2012/11/27/snapchat-the-biggest-no-revenue-mobile-app-since-instagram/. 24 Evelyn M. Rusli and Douglas MacMillan, 13 November 2013, op. cit. 25 Mike Isaac, ‘Snapchat Closes $60 Million Round Led by IVP, Now at 200 Million Daily Snaps’, article on AllThingsD.com, 24 June 2013, allthingsd.com/20130624/snapchat-closes-60-million-round-led-by-ivp-now-at-200-million-daily-snaps/. 26 ‘Recent Additions to Team Snapchat’, blog post on Snapchat.com, 24 June 2013, blog.snapchat.com/post/53763657196/recent-additions-to-team-snapchat. 27 Mike Isaac, ‘Snapchat Now Boasts More Than 150 Million Photos Taken Daily’, article on AllThingsD.com, 16 April 2013, allthingsd.com/20130416/snapchat-now-boasts-more-than-150-million-photos-taken-daily/. 28 Justin Lafferty, ‘Facebook Photo Storage Is No Easy Task’, article on AllFacebook.com, 16 January 2013, allfacebook.com/facebook-photo-storage-open-compute_b108640.

…

Google VP Explains How to Go Big’, article on VentureBeat.com, 19 April 2012, venturebeat.com/2012/04/19/want-to-get-acquired-by-google-google-vp-explains-howto-go-big/. 5 Mike Isaac, ‘Facebook Acquisition Talks With Waze Fall Apart’, article for AllThingsD.com, 29 May 2013, allthingsd.com/20130529/facebook-acquisition-talks-with-waze-fall-apart/. 6 Simone Wilson, ‘Billion-dollar Waze’, article on JewishJournal.com, 19 June 2013, www.jewishjournal.com/cover_story/article/billion_dollar_waze. 7 Ibid. 8 For details of the merger see www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1326801/000132680114000010/form8k_2192014.htm. 9 Gerry Shih and Sarah McBride, ‘Facebook to buy WhatsApp for $19 Billion in Deal Shocker’, article on Reuters.com, 20 February 2014, www.reuters.com/article/2014/02/20/us-whatsapp-facebook-idUSBR EA1I26B20140220. 10 ‘Facebook to Acquire WhatsApp’, press release on FB.com, 19 February 2014, newsroom.fb.com/News/805/Facebook-to-Acquire-WhatsApp. 11 Justin Lafferty, ‘Facebook Revenue Hits $2B in Q3, Now Has 507m Mobile DAUs’, article on InsideFacebook.com, 30 October 2013, www.insidefacebook.com/2013/10/30/facebook-revenue-hits-2b-in-q3-now-has-507m-mobile-daus/. 12 So WhatsApp seems to be processing more messages than all SMS in the world. 13 ‘Facebook to Acquire WhatsApp’, 19 February 2014, op. cit. 14 Adario Strange, ‘Facebook Reportedly Offered $1 Billion to Acquire Snapchat’, article on Mashable.com, mashable.com/2013/10/26/facebook-snapchat/. 15 Evelyn M. Rusli and Douglas MacMillan, ‘Snapchat Spurned $3 Billion Acquisitions Offer from Facebook’, blog post on WSJ.com, 13 November 2013, blogs.wsj.com/digits/2013/11/13/snapchat-spurned-3-billion-acquisition-offer-from-facebook/. 16 Cheryl Conner, ‘Facebook’s Reality Check: Death by a Thousand Snapchats?’, article on Forbes.com, 8 July 2013, www.forbes.com/sites/cherylsnappconner/2013/06/08/facebooks-reality-check-death-by-a-thousand-snapchats/. 17 Kara Swisher, ‘Yahoo Tumblrs for Cool: Board Approves $1.1 Billion Deal as Expected’, article on AllThingsD.com, 19 May 2013, allthingsd.com/20130519/yahoo-tumblrs-for-cool-board-approves-1-1-billion-deal/. 18 Todd Wasserman, ‘Tumblr’s Mobile Traffic May Overtake Desktop Traffic This Year’, article on Mashable.com, 21 February 2013, mashable.com/2013/02/21/tumblr-mobile-traffic/. 19 Ibid. 20 Marc Andreessen, ‘Why Software Is Eating the World’, article on WSJ.com, 20 August 2011, online.wsj.com/news/articles/ SB10001424053111903480 904576512250915629460. 21 Leena Rao, ‘As Software Eats the World, Non-Tech Corporations Are Eating Startups’, article on TechCrunch.com, 14 December 2013, TechCrunch.com/2013/12/14/as-software-eats-the-world-non-tech-corporations-are-eating-startups/. 22 Alexia Tsotsis, ‘Monsanto Buys Weather Big Data Company Climate Corporation for Around $1.1B’, article on TechCrunch.com, 2 October 2013, TechCrunch.com/2013/10/02/monsanto-acquires-weather-big-data-company-climate-corporation-for-930m/. 23 Leena Rao, 14 December 2013, op. cit. 24 Ibid. 25 Pitchbook, US, ‘VC Valuations and Trends’, 2014 annual report. 26 ‘Yesterday’s Big Payday for the IRS: 1600 Twitter Employees Now Millionaires’, research on PrivCo.com, 8 November 2013, www.privco.com/the-twitter-mafia-and-yesterdays-big-irs-payday. 27 Sven Grundberg, ‘“Candy Crush Saga” Maker Files for an IPO’, article on WSJ.com, 18 February 2014, online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304675504579390580161044024. 28 ‘UK Mobile Games Maker King Delays IPO Due to Candy Crush Surge’, article on VCPost.com, 9 December 2013, www.vcpost.com/articles/19437/20131209/uk-mobile-games-maker-king-delays-ipo-due-candy-crush.htm. 29 Phillipa Leighton-Jones, ‘Why Candy Crush Is a Success That’s Hard to Copy’, blog post on WSJ.com, 18 February 2014, blogs.wsj.com/money-beat/2014/02/18/why-candy-crush-is-a-success-that-cannot-be-copied/. 30 Mark Berniker and Josh Lipton, ‘Uber CEO Kalanick: No Plans To Go Public Right Now’, article on CNBC.com, 6 November 2013, www.cnbc.com/id/101175342.

…

Chapter 23: Revenue-Engine Mechanics 1 David Skok, ‘Startup Killer: The Cost of Customer Acquisitions’, article on forEntrepreneurs.com, 22 December 2009, www.forentrepreneurs.com/startup-killer/. 2 Eliana Dockterman, ‘Candy Crush Saga: The Science Behind Our Addiction’, article on Time.com, 15 November 2013, business.time.com/2013/11/15/candy-crush-saga-the-science-behind-our-addiction/. 3 Mia Shanley, ‘How Candy Crush Makes So Much Money’, article on BusinessInsider.com, 8 October 2013, www.BusinessInsider.com/how-candy-crush-makes-so-much-money-2013-10. 4 Dave McClure, ‘Startup Metrics for Pirates’, presented to Wildfire Interactive, May 2012, slide 73, www.slideshare.net/dmc500hats/startup-metrics-4-pirates-wildfire-interactive-may-2012. 5 Mike Isaac, ‘Snapchat Closes $60 Million Round Led by IVP, Now at 200 Million Daily Snaps’, article on AllThingsD.com, 24 June 2013, allthingsd.com/20130624/snapchat-closes-60-million-round-led-byivp-now-at-200-million-daily-snaps/. 6 Mike Isaac, ‘Snapchat Now Boasts More Than 150 Million Photos Taken Daily’, article on AllThingsD.com, 16 April 2013, allthingsd.com/20130416/snapchat-now-boasts-more-than-150-million-photos-taken-daily/. 7 Liz Gannes, ‘Popular Photo Message App Snapchat Adds Video’, article on AllThingsD.com, 14 December 2012, allthingsd.com/20121214/popular-photo-message-app-snapchat-adds-video/. 8 David Skok, ‘The Science Behind Viral Marketing’, article on forEntrepreneurs.com, 15 September 2011, www.forentrepreneurs.com/the-science-behind-viral-marketing/.

American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers

by

Nancy Jo Sales

Published 23 Feb 2016

And then, one Saturday night in October 2015, I was on my phone, scrolling through Yik Yak and not reading a book, when I heard about something which even blasé Yik Yakkers were finding shocking. “Oh my God, Syracusesnap.” “LMFAO Syracusesnap.” “What’s Syracusesnap?” people asked. Everybody wanted to know. Everybody had to know. Syracusesnap was a Snapchat Story, a series of pictures or videos on Snapchat which stay viewable for twenty-four hours rather than the usual one to ten seconds per Snap. On Snapchat, famously launched in 2011 by three fraternity brothers from Stanford, Stories have become the most popular feature, with more than a billion viewed daily, according to the company. But few go viral. Within hours of its creation, Syracusesnap was being followed by college students and teenagers across the country.

…

There was a picture of a boy holding two girls’ bodies on his shoulders, their behinds, in identical black thongs, facing the camera, his dumbstruck face encased with butt cheeks. “Snap whore,” said a picture of a girl Snapchatting, her cleavage prominently showing. There had been scandalous college Snapchat Stories before; in fact, such accounts can be found at colleges across the country. They’re a sort of rebellious parody of Snapchat’s Campus Stories, another feature on the app which many schools sponsor and monitor, and which typically shows students in their fun-filled and inspiring moments—looking joyful in the stands at winning football games, attending lectures.

…

UCLAyak, named in homage to Yik Yak, had sexually explicit photos and videos cycling “every few seconds,” according to the Daily Bruin, the University of California–Los Angeles paper. The anonymous psychobiology student who created the account told the Bruin he wasn’t surprised at the nudity: “It was just a matter of time. That’s what Snapchat is for.” He said he suspected that some of the videos on other rogue campus accounts were staged, created to shock. Snapchat’s Community Guidelines prohibit sexually explicit content, and the company routinely deletes Snapchat Stories that violate its policies, but as soon as they’re banned, they often just reappear with a different handle. So what made Syracusesnap go viral? As the Saturday night wore on and more kids were alerting one another to its scandalous appeal, the Story became more hard-core.

The Happiness Effect: How Social Media Is Driving a Generation to Appear Perfect at Any Cost

by

Donna Freitas

Published 13 Jan 2017

But for the college students I spoke with, this is an impoverished and limited understanding of Snapchat’s true delights. College students can be silly on Snapchat. They can be ridiculous. They can say dumb things. They can take goofy, ugly, unbecoming photographs and show them to other people. They can be sad, they can be negative, they can be angry, they can even be mean. They can be as emotional as they really feel. They can be honest. And it’s true, on Snapchat college students feel they can be sexy. But most of all, they play on Snapchat and they engage in all kinds of foolishness. And that’s why they love it. On Snapchat college students feel they can do all the things they’ve learned they’re not allowed to do on Facebook or any other platform that is more “permanent” and attached to their names.

…

And then I’ll be like, ‘Oh, I look nice today.’ ” Jackson likes using the selfie camera like a mirror, he tells me. But when he does take a selfie, he has to decide where it goes: Snapchat? Instagram? Facebook? “I really don’t care what I put on Snapchat,” Jackson says. I could wake up one morning, upload that selfie, and I wouldn’t put that on Instagram compared to my Snapchat, because [the morning selfie] is really more personal.” The same goes for “sleek photos,” which go up on Jackson’s Instagram but not Snapchat. On Facebook or Instagram, Jackson also posts selfies of him doing positive things. Jackson works as a tutor, and this is something he wants to share with people in a more permanent way.

…

Matthew tried to explain the difference between Facebook and Snapchat to me, and why Snapchat is much more fun. Like many students, Matthew goes onto Facebook a lot, but not to post—posting is too time-consuming and too much work, because every post has become so high-stakes. Mostly, Matthew just scrolls through the feed and lurks, checking out other people’s updates and photos. But Matthew loves Snapchat and goes on it all the time, and unlike with Facebook, on Matthew actually participates. “When I’m bored,” Matthew says, “I’ll snap a picture of something random, send it to, like, five people and wait for somebody to respond. [Snapchat] is really simple and fast, and it’s a way I can see what all my friends are up to, especially all my friends back home, all over the state and stuff.

Collaborative Society

by

Dariusz Jemielniak

and

Aleksandra Przegalinska

Published 18 Feb 2020

Whereas Instagram recommends to its users a number of other users that they might want to follow, Snapchat was and still is primarily designed for interacting with a smaller group of friends. Nonetheless, Snapchat gradually started to add more collaborative tools to allow users to post their photos and videos to custom story threads. With Custom Stories, as Snapchat calls them, users can add friends to a chosen story by selecting people from their contacts or by inviting users in a specified radius via Snapchat’s geofencing feature. In the press release announcing the new story options, Snapchat claimed that they were “perfect for a trip, a birthday party, or a new baby story just for the family.”32 To create a story, users can tap the “Create Story” icon; if a story has not been updated or added to within a 24-hour period, it disappears in typical Snapchat manner.

…

One company describes this option in the following way: “At their own convenience, they go for a walk to go through what’s on the other person’s mind and snap back their replies.” Apparently, many teams also use Snapchat to keep fit, which takes us back to the ideas in our chapter on collaborative gadgets. As yet another pro-Snapchat company exec boasts, “Spearheaded by Alberto “Muscles” Nodale, Close.io has turned into a team that gets excited about sweating. Through Snapchat, we send each other pep talks and gym guilt.”36 Nevertheless, Snapchat was not meant to be an internal communications tool. The platform does not guarantee that employees will adopt it: not everyone wants to be a part of the Snapchat community, and not everyone knows how to become one.

…

In the press release announcing the new story options, Snapchat claimed that they were “perfect for a trip, a birthday party, or a new baby story just for the family.”32 To create a story, users can tap the “Create Story” icon; if a story has not been updated or added to within a 24-hour period, it disappears in typical Snapchat manner. Teams working remotely from different locales and time zones have discovered Snapchat as an internal communications tool in addition to their existing software stack. Today, when we think about professional collaborative tools for remote teams, we mainly refer to Zoom (video conferencing), Slack and Basecamp (project management apps and tools), or Hackpad (real-time collaborative text editing), to mention just a few. Although professional software stacks for internal communications are impressive, Snapchat attempts to compete by introducing a welcome, genuine human connection to relationships with other team members that surpasses an email exchange or a Skype call.

The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power

by

Michael A. Cusumano

,

Annabelle Gawer

and

David B. Yoffie

Published 6 May 2019

The flip side of digital technology accelerating opportunities for differentiation and niche competition was that it could be equally easy for incumbents to copy. Mark Zuckerberg almost immediately recognized Snapchat as a potential threat to Facebook. Given Facebook’s size and scale, he logically tried to buy Snap for $3 billion in cash before the company went public. When Spiegel turned him down, Zuckerberg ordered Instagram to copy Snapchat’s most compelling features and turn Instagram into a Snapchat killer.35 Especially after introducing Instagram Stories, Instagram zoomed past Snapchat, with over 700 million users. Although Snapchat was hardly dead (its market value had fallen dramatically but was still close to $6 billion in late 2018), Facebook’s attack had taken a serious toll.

…

Instead, they can access the external supply of creativity and software engineering skills available worldwide. But sometimes adding the second platform is more an act of desperation. Snapchat, for example, has struggled with competition from Facebook’s Instagram. In 2018 it opened up its APIs to encourage third parties to build complementary innovations in the hope that some new apps would make Snapchat a more compelling experience for users and a better draw for advertisers.35 Besides Facebook and Snapchat, a less obvious transaction-to-innovation hybrid example was Expedia, the travel services platform. When Expedia established an affiliate program under the banner of “Your Business.

…

Google executives have made this argument, citing the ease of multi-homing to defray criticism of their dominant position in Internet search, since competitors are merely “one click away.”30 As we discussed earlier with the Facebook example, Mark Zuckerberg may have created the world’s largest social network. However, it is easy for Facebook users to spend time on Twitter, LinkedIn, Snapchat, Pinterest, and other platforms, even if they may not take the trouble to adopt another social network for most of their activities. To control some of the revenues associated with multi-homing was at least one reason why Zuckerberg acquired Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion (considered a large sum at the time) and later used it to compete with Snapchat.31 Zuckerberg’s much more costly purchase of WhatsApp in 2014 for what amounted to $19 billion plus another $3 billion in Facebook stock was another defensive move against multi-homing for messaging as well as an offensive move to acquire more users and a potentially new revenue source.32 At the same time, clever use of data and sophisticated AI tools can discourage multi-homing because of better services.

App Kid: How a Child of Immigrants Grabbed a Piece of the American Dream

by

Michael Sayman

Published 20 Sep 2021

In eight months, our launch of Instagram Stories surpassed Snapchat’s number of users. By 2018, Instagram Stories had more than twice as many users as Snapchat. Today, over half a billion people use Instagram Stories every single day. IG Stories launched before Snapchat went public, but by the time it did, in March 2017, Snapchat had lost 56 percent of its value. It was widely reported in tech media that this was a direct result of Instagram Stories. A lot of Facebookers felt pretty cocky about that. But I thought we should be grateful for what Snapchat had taught us—which was that we weren’t the source of all creativity and innovation, nor did we have to be.

…

* * * — Lifestage wasn’t the only project I was working on. At long last, Facebook had decided to get serious about competing with Snapchat—particularly Snapchat Stories, collections of snaps that lived for twenty-four hours. So I was now helping to implement our own version of Stories for WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, and Messenger. I’d been yelling about the Snapchat threat ever since I’d given my first Teen Talk in 2014, and the executives had finally started to listen, including me in meetings and cc’ing me on memos about anything Snapchat related. I was brought in to review designs and meet with engineers and executive leadership to strategize about the company’s overall goals for the product.

…

A few teams invited me to join them in my early weeks, but I dragged my feet on accepting an offer because I wasn’t excited about the projects they were working on. Thanks to my internship, it was fresh in my mind that I shouldn’t say yes when my gut said no. My gut was telling me to hold out for a team that was working on the problem I’d been noticing since my internship: the Snapchat threat. In 2014, Snapchat was just becoming really popular, and everyone I knew loved it. But while Snapchat had every teenager in America in its thrall, Facebook was a non-player in most kids’ social media lives. Sure, we used it for school meetups and other adult-sanctioned activities, but it wasn’t where we went to hang out and be ourselves. Facebookers had to be panicking about this, didn’t they?

Facebook: The Inside Story

by

Steven Levy

Published 25 Feb 2020

So in 2011, Facebook bought Foursquare’s main independent competitor, Gowalla. Spiegel and Murphy felt that Poke was a pale imitation of Snapchat, and laughed it off. Perhaps they felt a little queasy when immediately after launch, Poke reached number one in Apple’s App Store. But they felt a lot better when Poke did a nosedive in the ratings over the next few days. Not only was Poke a failure for Facebook, but it was a boon for Snapchat. It had legitimized Snapchat’s product vision. Snapchat kept growing, making it even more attractive to Zuckerberg. In 2013, he resumed his hunt, visiting Snapchat’s Venice Beach headquarters with his chief dealmaker, Amid Zoufonoun, in tow.

…

a review from the FTC: Josh Kosman, “Facebook Boasted of Buying Instagram to Kill the Competition: Sources,” New York Post, February 26, 2019. Snapchat: In addition to interviews, I drew on Billy Gallagher’s definitive book, How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars (St. Martin’s Press, 2018). Also valuable was Sarah Frier and Max Chafkin, “How Snapchat Built a Business by Confusing Olds,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, March 17, 2016; J. J. Coloa, “The Inside Story of Snapchat: World’s Hottest App or a $3 Billion Disappearing Act?” Forbes, January 6, 2014; and Sarah Frier, “Nobody Trusts Facebook, Twitter Is a Hot Mess, What Is Snapchat Doing?” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, August 22, 2018. “When Snapchat started out”: Brad Stone and Sarah Frier, “Evan Spiegel Reveals Plan to Turn Snapchat into a Real Business,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, May 16, 2015.

…

In May 2013, Zuckerberg wrote an email outlining all the great things that would happen if Snapchat joined the Facebook family. If Snapchat sold to Facebook, he said, Facebook had a playbook to raise the user base to a billion people. There were private APIs that Facebook didn’t share with developers. What’s more, Zuckerberg wooed Spiegel personally with promises that the younger entrepreneur not only would run Snapchat with some degree of autonomy but would have an opportunity to make an impact on Facebook itself. So even though you’ll spend your time on Snapchat it would be fun to work together closely to figure out how Facebook should evolve as well.

Always Day One: How the Tech Titans Plan to Stay on Top Forever

by

Alex Kantrowitz

Published 6 Apr 2020

As time went on, Sayman watched his fellow teens sharing less on Facebook’s family of apps and more on Snapchat. He turned his focus to Snapchat Stories, which he believed Facebook should build into its products. “I wanted the company to feel like Snapchat was an existential threat,” he said. “I wanted Facebook to panic.” Sayman brought his concerns to Zuckerberg, who had heard from others who came to similar conclusions. As a teenager, Sayman was invaluable. He could help Zuckerberg learn Snapchat’s culture. “He would point us to, ‘Here’s the media that I follow,’ or ‘Here are the people I think are influential, who are cool,’” Zuckerberg said.

…

And that type of sharing was starting to gravitate elsewhere. “The Most Chinese Company in Silicon Valley” At around the same time Facebook was working out its News Feed issues, an upstart messaging app called Snapchat—led by the brash Stanford graduate Evan Spiegel—built a feature called Stories, which let people share photos and videos with friends that disappeared in a day. Snapchat’s users loved how Stories gave them a carefree way to post (in contrast with Facebook, where your posts would go to everyone and stick around forever), and the app’s usage exploded. Spiegel, who once spurned a $3 billion acquisition offer from Zuckerberg, was now hitting him where it hurt.

…

In the zero-sum game of social media, where time spent on one platform is time not spent on another, Spiegel had the energy, the sharing, and was driving his company toward a hot IPO. As Snapchat took off, an eighteen-year-old developer named Michael Sayman joined Facebook. Sayman had built a game that caught Zuckerberg’s eye, and the company hired him as a full-time engineer in 2015. Sitting through orientation, Sayman heard speeches about how Facebook’s leaders would listen to anyone’s ideas, and took the message to heart. “I believed it,” he told me. Before orientation was over, he spun up a presentation about how teens, already drifting to Snapchat, were using technology, and how Facebook might want to build for them.

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by

Roger McNamee

Published 1 Jan 2019

In August 2018, Apple announced that Onavo violated its privacy standards, so Facebook withdrew it from the App Store. One of the competitors Facebook has reportedly tracked with Onavo is Snapchat. There is bad blood between the two companies that began after Snapchat rejected an acquisition offer from Facebook in 2013. Facebook started copying Snapchat’s key features in Instagram, undermining Snapchat’s competitive position. While Snapchat managed to go public and continues to operate as an independent company, the pressure from Facebook continues unchecked and has taken a toll. Under a traditional antitrust regime, Snapchat would almost certainly have a case against Facebook for anticompetitive behavior.

…

Thanks to photo tagging, users have built a giant database of photos for Facebook, complete with all the information necessary to monetize it effectively. Other platforms play this game, too, but not at Facebook’s scale. For example, Snapchat offers Streaks, a feature that tracks the number of consecutive days a user has traded messages with each person in his or her contacts list. As they build and the number of them grows, Streaks take on a life of their own. For the teens who dominate Snapchat’s user base, Streaks can soon come to embody the essence of a relationship, substituting a Streak number for the elements of true friendship. Another emotional trigger is fear of missing out (FOMO), which drives users to check their smartphone every free moment, as well as at times when they have no business doing so, such as while driving.

…

Eventually that would create problems it could not resolve with an apology and a promise to do better. 4 The Children of Fogg It’s not because anyone is evil or has bad intentions. It’s because the game is getting attention at all costs. —TRISTAN HARRIS On April 9, 2017, onetime Google design ethicist Tristan Harris appeared on 60 Minutes with Anderson Cooper to discuss the techniques that internet platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat use to prey on the emotions of their users. He talked about the battle for attention among media, how smartphones transformed that battle, and how internet platforms profit from that transformation at the expense of their users. The platforms prey on weaknesses in human psychology, using ideas from propaganda, public relations, and slot machines to create habits, then addiction.

The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything

by

Matthew Ball

Published 18 Jul 2022

The social networking giant entered 2010 with more than half a billion monthly active users, but has failed to subsume any of the hit social media platforms which emerged in the decade. Snapchat launched in 2011, with Facebook launching its own Snapchat-like app (or “clone”) in 2013, called “Poke,” which was shuttered a year later. In 2016, Facebook launched “Lifestage,” its second Snapchat clone, with was also closed after 12 months. That same year, Facebook’s Instagram app also copied Snapchat’s signature “Stories” format, with Facebook’s main app adding the feature the following year. Then in 2019, Instagram launched its own dedicated Snapchat-like app, “Threads from Instagram,” though almost no one noticed. Facebook Gaming, the company’s Twitch competitor, launched in 2018, as did Facebook’s TikTok competitor, Lasso.

…

There is a reason why every social network has shifted over time to original programming, revenue guarantees, and creator funds. Unfortunately, the dynamics that apply to “2D” content networks don’t easily carry over to IVWP. Most of the content made on YouTube or Snapchat isn’t produced using those platforms’ tools. Instead, it’s produced with independent applications, such as Apple’s Camera app, or Adobe’s Photoshop and Premiere Pro. Even when content is made on a social platform, such as a Snapchat Story, which uses Snap’s filters, the content is typically easy to export (and to use again on Instagram) because it is just a photo. Conversely, the content made for an IVWP is mostly made in that IVWP.

…

Conversely, the content made for an IVWP is mostly made in that IVWP. It cannot be easily exported, or repurposed—and there are no available “hacks” similar to using an iPhone’s “screenshot” function to grab a Snapchat Story. As such, content made on Roblox is essentially Roblox-only. And unlike a YouTube video or Snapchat Story, Roblox content is not ephemeral (like a live stream), nor is it ever intended to be catalogued (as is the case with a YouTuber’s vlogs). Instead, it is intended to be continuously updated. The consequences of these differences are profound. If a developer wants to operate across multiple IVWPs, they must rebuild nearly every part of their experiences—an investment that produces no value to users and wastes time and money.

The Art of Invisibility: The World's Most Famous Hacker Teaches You How to Be Safe in the Age of Big Brother and Big Data

by

Kevin Mitnick

,

Mikko Hypponen

and

Robert Vamosi

Published 14 Feb 2017

Generation Z’s actions on their mobile devices center around WhatsApp (ironically, now part of Facebook), Snapchat (not Facebook), and Instagram and Instagram Stories (also Facebook). All these apps are visual in that they allow you to post photos and videos or primarily feature photos or videos taken by others. Instagram, a photo-and video-sharing app, is Facebook for a younger audience. It allows follows, likes, and chats between members. Instagram has terms of service and appears to be responsive to take-down requests by members and copyright holders. Snapchat, perhaps because it is not owned by Facebook, is perhaps the creepiest of the bunch. Snapchat advertises that it allows you to send a self-destructing photo to someone.

…

In the United Kingdom, a fourteen-year-old boy sent a naked picture of himself to a girl at his school via Snapchat, again thinking the image would disappear after a few seconds. The girl, however, took a screenshot and… you know the rest of the story. According to the BBC, the boy—and the girl—will be listed in a UK database for sex crimes even though they are too young to be prosecuted.22 Like WhatsApp, with its inconsistent image-blurring capabilities, Snapchat, despite the app’s promises, does not really delete images. In fact Snapchat agreed in 2014 to a Federal Trade Commission settlement over charges that the company had deceived users about the disappearing nature of its messages, which the federal agency alleged could be saved or retrieved at a later time.23 Snapchat’s privacy policy also says that it does not ask for, track, or access any location-specific information from your device at any time, but the FTC found those claims to be false as well.24 It is a requirement of all online services that individuals be thirteen years of age or older to subscribe.

…

Robert Vamosi, When Gadgets Betray Us: The Dark Side of Our Infatuation with New Technologies (New York: Basic Books, 2011). 9. http://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2011/08/01/how-face-recognition-can-be-used-to-get-your-social-security-number/. 10. https://techcrunch.com/2015/07/13/yes-google-photos-can-still-sync-your-photos-after-you-delete-the-app/. 11. https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms. 12. http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2014/03/how-to-beat-facebook-s-biggest-privacy-risk/index.htm. 13. http://www.forbes.com/sites/amitchowdhry/2015/05/28/facebook-security-checkup/. 14. http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2012/06/facebook-your-privacy/index.htm. 15. http://www.cnet.com/news/facebook-will-the-real-kevin-mitnick-please-stand-up/. 16. http://www.eff.org/files/filenode/social_network/training_course.pdf. 17. http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/03/17/pearson-under-fire-for-monitoring-students-twitter-posts/. 18. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2015/03/14/pearson-monitoring-social-media-for-security-breaches-during-parcc-testing/. 19. http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/Passcode-Voices/2015/0513/Is-student-privacy-erased-as-classrooms-turn-digital. 20. https://motherboard.vice.com/blog/so-were-sharing-our-social-security-numbers-on-social-media-now. 21. http://pix11.com/2013/03/14/snapchat-sexting-scandal-at-nj-high-school-could-result-in-child-porn-charges/. 22. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-34136388. 23. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2014/05/snapchat-settles-ftc-charges-promises-disappearing-messages-were. 24. http://www.informationweek.com/software/social/5-ways-snapchat-violated-your-privacy-security/d/d-id/1251175. 25. http://fusion.net/story/192877/teens-face-criminal-charges-for-taking-keeping-naked-photos-of-themselves/. 26. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150206-biggest-myth-about-phone-privacy. 27. http://fusion.net/story/141446/a-little-known-yelp-setting-tells-businesses-your-gender-age-and-hometown/?

Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China's ByteDance

by

Matthew Brennan

Published 9 Oct 2020

As the platform grew, this group became outright celebrities, in some part due to their creativity, persistence, and hard work, in most part due to the invisible hand of the Shanghai content operations team tilting the attention game heavily in their favor. Younger than Snapchat Once the platform had grown large enough to garner mainstream media attention, the first thing reporters picked up on was the users’ age. “This is no question the youngest social network we’ve ever seen,” exclaimed online marketing guru Gary Vaynerchuk in an article profiling the platform. 158 “Snapchat and Instagram skew a little bit young… but with Musical.ly, you’re talking about first, second, third grade.” Above: A snapshot of the top 10 most popular Musical.ly accounts in late 2016 with numbers of followers and the ages of the creators at the time.

…

Musical.ly had built a meaningful brand that resonated strongly with American and European teens. ByteDance, Facebook, Tencent, Snapchat, 250 and Kuaishou, had all expressed interest at various times and engaged in talks with the founders. Sometimes referred to as the “Berkshire Hathaway of tech,” Tencent was a prolific investor in other internet companies. Pulling out of talks with Musical.ly and having missed the opportunity to acquire WhatsApp in 2014, Tencent instead opted to gain a foothold in Western social networking via a $2 billion stake in Snapchat. Kevin Systrom, the then CEO of Instagram, had met in person with Musical.ly’s founders in Shanghai and later persuaded Mark Zuckerberg to consider a deal.

…

As users themselves generated all content, fewer older users meant there was little content suitable for them being produced. Why produce content if there’s no audience? This meant that when older users did join, they quickly left. The solution was to broaden the types of content offerings and slowly age up the user base. “We realized while Instagram and Snapchat are social graph led, the fact that Musical.ly was content & creative led was an opportunity, NOT an obstacle. It would be mobile TV for the smartphone generation, and in order to age up, we needed to broaden the content offering and tell that story to the world,” explained product strategist James Veraldi in a later presentation.

New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World--And How to Make It Work for You

by

Jeremy Heimans

and

Henry Timms

Published 2 Apr 2018

Spiegel checks this box by abandoning Stanford University only a few credits short of graduation to pursue his Snapchat dream. He then shifts neatly into chapter 3—a legal brouhaha with his co-founders—falling out with Brown, the guy who first had the idea. Brown sues him. Our story hits its climax in chapter 4, when Spiegel gets approached by his entrepreneur-hero, Mark Zuckerberg, who offers to buy Snapchat for $3 billion. But will Spiegel believe enough in his idea to reject his hero and risk it all? Hell yes. You know what happened next. Snapchat grows wildly, Spiegel thrives. The company goes public at a $24 billion valuation.

…

“trophy case”: Lorenzo Ligato, “Here’s How to Unlock All of the New Snapchat Trophies,” Huffington Post, October 20, 2015. The online service TINYpulse: TINYpulse, July 2017. www.tinypulse.com. It has been adopted: Ibid. “The Founders Generation”: David Sims, “All Hail ‘The Founders,’ ” The Atlantic, December 2, 2015. Our story hits its climax: Jeff Bercovici, “Facebook Tried to Buy Snapchat for $3B in Cash. Here’s Why,” Forbes, November 13, 2013. The company goes public: Portia Crowe, “Snap Is Going Public at a $24 Billion Valuation,” Business Insider, March 1, 2017. “He just wants”: Austin Carr, “What Snapchat’s High-Profile Exec Departures Really Tell Us About CEO Evan Spiegel,” Fast Company, October 20, 2015.

…

Often the most extensible ideas feel imperfect and incomplete; if the idea feels “untouchable” or overly polished, it is very hard for others to feel they can take the reins and make it their own. An award-winning example of an extensible idea comes from Taco Bell, which for Cinco de Mayo in 2016 created a special lens on Snapchat that allowed people to turn their heads into giant taco shells and have hot sauce poured over the top. It won the title of most popular lens in Snapchat history by scoring 224 million views in one day. Many will scoff, but contrast this engagement to the dynamics of taking a traditional ad slot during prime-time TV programming. The guy on his couch, eating potato chips, may or may not pay attention to the message blaring out of the TV at him and everyone else in that cable district as he waits impatiently for his favorite show to start up again.

Frenemies: The Epic Disruption of the Ad Business

by

Ken Auletta

Published 4 Jun 2018

So on Instagram you see these photos three days later. On Snapchat, you see Snaps the moment they are created.” Martin Sorrell decided in 2016 to ride the Snapchat horse as a rival worth betting on. He decided to sweeten the ad dollars WPP earmarked for Snapchat. “It does become a threatening alternative to Facebook,” he told CNBC, “and I think that’s the big opportunity for them. . . . I think Facebook is concerned about the potential opposition.” Not that concerned. Sorrell’s threat was pure bluster. Although WPP would over time double the ad dollars it steered to Snapchat, from $90 million in 2016 to $200 million in 2017, it was akin to throwing pebbles in the ocean: WPP’s ad spending on Google rose five times as fast in 2016, totaling $5 billion; WPP purchased $1.7 billion of ads on Facebook in 2016.

…

By late 2015, many agencies and clients hoped two digital competitors might bust out: AOL, which was armed with new financial resources when Verizon decided it was too risky to be a dumb pipe and acquired AOL in May 2015, or Snapchat, an emerging social network Facebook competitor. With AOL and the Huffington Post providing content and Verizon providing the pipe and data on its 135 million telephone customers, AOL CEO Tim Armstrong boldly proclaimed to an Advertising Week audience in September 2015 that the new entity “has dreams of being the largest mobile media company in the world.” The competitive target, he said, was Google and Facebook. The cofounder and CEO of Snapchat, Evan Spiegel, openly aspires to disrupt Facebook, which he mocked as passé.

…

Although WPP would over time double the ad dollars it steered to Snapchat, from $90 million in 2016 to $200 million in 2017, it was akin to throwing pebbles in the ocean: WPP’s ad spending on Google rose five times as fast in 2016, totaling $5 billion; WPP purchased $1.7 billion of ads on Facebook in 2016. While Snapchat’s revenues jumped seven times faster in 2016, they only reached $404.5 million. By contrast, Facebook’s ad revenues totaled $27 billion that year. The looming threat to Facebook and Google, which would prompt Sorrell and the agencies and their clients—as well as Facebook and Google—to quake, would not come from Snapchat. It would come from Amazon. 8. THE RISE OF MEDIA AGENCIES “We always had the view that the less a media owner knows about what our objectives are and what our needs are, the more leverage we have in a negotiation.

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by

Andrew Keen

Published 5 Jan 2015

,” TechCrunch, June 15, 2011, techcrunch.com/2011/06/15/keen-on-eli-pariser-have-progressives-lost-faith-in-the-internet-tctv. 42 Claire Carter, “Global Village of Technology a Myth as Study Shows Most Online Communication Limited to 100-Mile Radius,” BBC, December 18, 2013; Claire Cain Miller, “How Social Media Silences Debate,” New York Times, August 26, 2014. 43 Josh Constine, “The Data Factory—How Your Free Labor Lets Tech Giants Grow the Wealth Gap.” 44 Derek Thompson, “Google’s CEO: ‘The Laws Are Written by Lobbyists,’” Atlantic, October 1, 2010. 45 James Surowiecki, “Gross Domestic Freebie,” New Yorker, November 25, 2013. 46 Monica Anderson, “At Newspapers, Photographers Feel the Brunt of Job Cuts,” Pew Research Center, November 11, 2013. 47 Robert Reich, “Robert Reich: WhatsApp Is Everything Wrong with the U.S. Economy,” Slate, February 22, 2014. 48 Alyson Shontell, “Meet the 20 Employees Behind Snapchat,” Business Insider, November 15, 2013, businessinsider.com/snapchat-early-and-first-employees-2013-11?op=1. 49 Douglas Macmillan, Juro Osawa, and Telis Demos, “Alibaba in Talks to Invest in Snapchat,” Wall Street Journal, July 30, 2014. 50 Mike Isaac, “We Still Don’t Know Snapchat’s Magic User Number,” All Things D, November 24, 2013. 51 Josh Constine, “The Data Factory—How Your Free Labor Lets Tech Giants Grow the Wealth Gap,” TechCrunch. 52 Alice E.

…

There’s also Twitter and Tumblr and Facebook and the rest of a seemingly endless mirrored hall of social networks, apps, and platforms stoking our selfie-centered delusions. Indeed, in an economy driven by innovator’s disasters, new social apps such as WhatsApp, WeChat, and Snapchat—a photo-sharing site that, in November 2013, turned down an all-cash acquisition offer of more than $3 billion from Facebook—are already challenging Instagram’s dominance.22 And by the time you read this, there will, no doubt, be even more destructive new products and companies undermining 2014 disruptors like Snapchat, WhatsApp, and WeChat. For us, however, Instagram—whether or not it remains the “second plotline” of the networked generation—is a useful symbol of everything that has gone wrong with our digital culture over the last quarter of a century.

…

They wanted us—our labor, our productivity, our network, our supposed creativity. It’s the same reason Yahoo acquired the microblogging network Tumblr, with its 300 million users and just 178 employees, for $1.1 billion in May 2013, or why in November 2013 Facebook made its $3 billion cash offering for the photography-sharing app Snapchat with its mere twenty employees.48 And that’s why Evan Spiegel, Snapchat’s twenty-three-year-old, Stanford-educated CEO, turned down Facebook’s $3 billion offer for his twenty-person startup. Yes, that’s right—he actually turned down $3 billion in cash for his two-year-old startup. But, you see, Spiegel’s minuscule app company—which, six months after rejecting Facebook’s $3 billion deal, was negotiating a new round of financing with the Chinese Internet giant Alibaba at a rumored $10 billion valuation49—isn’t really as tiny as it seems.

The Twittering Machine

by

Richard Seymour

Published 20 Aug 2019

Meanwhile, Facebook tugs on the heartstrings by displaying photos of friends who will ‘miss you’ – leveraging its control over uploaded content for commercial purposes. There is evidence that the existing platforms are reaching their peak. Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat have all seen declining user numbers, especially during 2018. Ironically, Snapchat’s fall may have been precipitated by its dependence on celebrity, as a single tweet from Kylie Jenner announcing to her 25 million followers that she didn’t ‘open Snapchat anymore’ instantly wiped $1.3 billion off the company’s value.72 But the trend is universal. Facebook’s announcement that it had lost a million users across Europe in one year has cost it $120 billion worth of value, as teens drop out.

…

On the fate of these websites and Facebook’s painstaking measures to prevent disconnections, see Tero Karppi, Disconnect: Facebook’s Affective Bonds, University of Minnesota Press: Minnesota, MN, 2018; and also Tero Karppi, ‘Disconnect.Me: User Engagement and Facebook’, University of Turku: Turku, 2014. 72. Ironically, Snapchat’s fall . . . ‘Kylie Jenner “sooo over” Snapchat – and shares tumble’, BBC News, 23 February 2018; Mark Sweeney, ‘Peak social media? Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat fail to make new friends’, Guardian, 10 August 2018; Rupert Neate, ‘Over $119bn wiped off Facebook’s market cap after growth shock’, Guardian, 26 July 2018. 73. Yet, 40 per cent of the world’s entire population . . .

…

Some of the repetitive banality of selfies can be blamed on the conventions of selfie-taking. Some of it can be blamed on the pursuit of ‘likes’ which incentivizes the repetition of popular images. But the platforms, from Snapchat to Instagram, and apps like Meitu, also offer a form of memetic enchantment. Selfies are worked through a limited range of reality-enhancers, called filters. Snapchat filters make us look cartoonish, with cute puppy ears and noses, while Instagram filters were at first notoriously nostalgic, casting a spell of mal du pays. Filters soften the features and flaws of the face, making us appear polished, perfect, almost mythical.

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

by

Nir Eyal

Published 26 Dec 2013

The more swipes, the more potential matches are made; naturally, each match sends notifications to both interested parties. 3. Snapchat As of June 2013, Snapchat, a popular photo-sharing app, boasted of 5 million daily active users collectively sending over 200 million photos and videos daily.12 This tremendous engagement means an average Snapchat user sends forty photos every day! Why are users so in love with Snapchat? Its success can largely be attributed to the fact that users load the next trigger every time they use the service. Snapchat is more than a way to share images. It is a means of communication akin to sending a text message—with the added bonus of a built-in timer that can, based on the sender’s instructions, cause the message to self-destruct after viewing.

…

Peter Farago, “App Engagement: The Matrix Reloaded,” Flurry (accessed Nov. 13, 2013), http://blog.flurry.com/bid/90743/App-Engagement-The-Matrix-Reloaded. 11. Anthony Ha, “Tinder’s Sean Rad Hints at a Future Beyond Dating, Says the App Sees 350M Swipes a Day,” TechCrunch (accessed Nov. 13, 2013), http://techcrunch.com/2013/10/29/sean-rad-disrupt. 12. Stuart Dredge, “Snapchat: Self-destructing Messaging App Raises $60M in Funding,” Guardian (June 25, 2013), http://www.theguardian.com/technology/appsblog/2013/jun/25/snapchat-app-self-destructing-messaging. 13. Kara Swisher and Liz Gannes, “Pinterest Does Another Massive Funding—$225 Million at $3.8 Billion Valuation (Confirmed),” All Things Digital (accessed Nov. 13, 2013), http://allthingsd.com/20131023/pinterest-does-another-massive-funding-225-million-at-3-8-billion-valuation/.

…

“On Fifth Anniversary of Apple iTunes Store, YouVersion Bible App Reaches 100 Million Downloads: First-Ever Survey Shows How App Is Truly Changing Bible Engagement,” PRWeb (July 8, 2013), http://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/7/prweb10905595.htm. 2. Alexia Tsotsis,“Snapchat Snaps Up a $80M Series B Led by IVP at an $800M Valuation,” TechCrunch (accessed Nov. 13, 2013), http://techcrunch.com/2013/06/22/source-snapchat-snaps-up-80m-from-ivp-at-a-800m-valuation. 3. YouVersion infographics (accessed Nov. 13, 2013), http://blog.youversion.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/themobilebible1.jpg. 4. Henry Alford, “If I Do Humblebrag So Myself,” New York Times (Nov. 30, 2012), http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/02/fashion/bah-humblebrag-the-unfortunate-rise-of-false-humility.html. 5.

Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language

by

Gretchen McCulloch

Published 22 Jul 2019

November 27, 2012. “Snapchat: The Biggest No-Revenue Mobile App Since Instagram.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2012/11/27/snapchat-the-biggest-no-revenue-mobile-app-since-instagram/#1499ff0e7200. like Instagram and Snapchat: Somini Sengupta, Nicole Perlroth, and Jenna Wortham. April 13, 2012. “Behind Instagram’s Success, Networking the Old Way.” The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2012/04/14/technology/instagram-founders-were-helped-by-bay-area-connections.html. a new format for posts: Robinson Meyer. August 3, 2016. “Why Instagram ‘Borrowed’ Stories from Snapchat.” The Atlantic. www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/08/cameras-with-constraints/494291/.

…

Awareness that your friends were in the library or watching a movie didn’t explain why people spent an average of fifty minutes per day on Facebook in 2016, up from forty minutes per day in 2014. Moreover, as connectivity became ever easier and more mobile, it was no longer necessary to explain why you were away from the computer: you weren’t. Yet social media posts got more popular, rather than less, joined by mobile-first platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, which required that posts include an image or short video. Snapchat and later Instagram even brought us a new format for posts: the story which vanishes after twenty-four hours, a window into the fun, non-computery things you’ve been doing. A “normal” profile page gradually changed from being a list of static facts about you to a list of things you’ve posted recently.

…

“From Statistical Panic to Moral Panic: The Metadiscursive Construction and Popular Exaggeration of New Media Language in the Print Media.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11. International Communication Association. pp. 67–701. Ben Rosen. February 8, 2016. “My Little Sister Taught Me How to ‘Snapchat Like the Teens.’” BuzzFeed. www.buzzfeed.com/benrosen/how-to-snapchat-like-the-teens. Mary H.K. Choi. August 25, 2016. “Like. Flirt. Ghost. A Journey into the Social Media Lives of Teens.” Wired. www.wired.com/2016/08/how-teens-use-social-media/. Andrew Watts. January 3, 2015. “A Teenager’s View on Social Media.” Wired. backchannel.com/a-teenagers-view-on-social-media-1df945c09ac6.

The Four: How Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google Divided and Conquered the World

by

Scott Galloway

Published 2 Oct 2017

We absorb imagery sixty thousand times faster than words.24 So, images make a beeline for the heart. And if Snapchat is threatening to hive off a meaningful chunk of that market, or even climb into the lead, that threat must be quashed. To do this, Facebook is developing a new camera-first interface in Ireland. It’s a clone of Snapchat. In a 2016 earnings call, Zuckerberg said, and this may sound oddly similar: “We believe that a camera will be the way that we share.” Facebook has already appropriated (that is, stolen) other Snapchat ideas, including Quick Updates, Stories, selfie filters, and one-hour messages. The trend will only continue—unless the government gets in the way.

…

April 12, 2017. http://www.cnbcafrica.com/news/technology/2017/04/10/many-48-million-twitter-accounts-arent-people-says-study/. 21. L2 Analysis of LinkedIn Data. 22. Novet, Jordan. “Snapchat by the numbers: 161 million daily users in Q4 2016, users visit 18 times a day.” VentureBeat. February 2, 2017. https://venturebeat.com/2017/02/02/snapchat-by-the-numbers-161-million-daily-users-in-q4-2016-users-visit-18-times-a-day/. 23. Balakrishnan, Anita. “Snap closes up 44% after rollicking IPO.” CNBC. March 2, 2017. http://www.cnbc.com/2017/03/02/snapchat-snap-open-trading-price-stock-ipo-first-day.html. 24. Pant, Ritu. “Visual Marketing: A Picture’s Worth 60,000 Words.”

…

Finally, Snap appeals to teens, a notoriously difficult and influential segment. Snapchat has added lots of features in the months since its founding. It has even pushed into TV, launching a mobile video channel. In 2017, the company is gaining fast on Twitter, and had 161 million daily users when it filed for an IPO.22 It IPO’d with a value of $33 billion.23 We’ll see. Facebook already is positioning itself to crush the young company. Imran Khan, the company’s chief strategy officer, claimed: “Snapchat is a camera company. It is not a social company.” I don’t know if it’s the scorn the Zuck feels after Evan rejected his overtures about acquisition, or a warranted response to a threat.

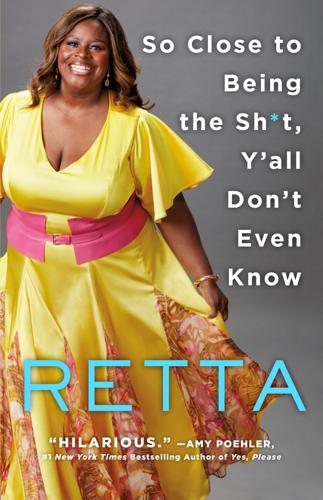

So Close to Being the Sh*t, Y'all Don't Even Know

by

Retta

Published 28 May 2018

Let it go, girl, I thought. It’s not that serious! Now I want to send my friend a formal letter of apology and present her with a $1,000 Starbucks gift card. I get it. I’m her. I’m every woman and man who loves coffee and wants to shout it out loud and proud from the rooftops to their Snapchat story! And I do. My Snapchat followers know that every morning, I post a video of my first cup of coffee, as I gleefully sing, “Dark Maaagiiic!” Can’t stop, won’t stop. So much so that since starting my coffee routine, my once relatively pearly whites ain’t so white no mo’. At my last dentist appointment, the hygienist looked in my mouth and frowned.

…

The jobless spend the most time on Snapchat. 2. Astronauts can tweet from space but I can’t get my Wi-Fi to reach my bedroom. 3. I experience anxiety when I haven’t updated my Bitmoji’s outfit to be season-appropriate. 4. I don’t care how “advanced” we’re supposed to be. I’ll give you my cordless landline when you pry it from my cold, dead hands. 5. When I get an alert that a friend has JUST joined Instagram: . 6. How do we not have voice-activated search on TiVo? So much button pressing. What are we, animals?? 7. No one cares about ur Snapchat concert vids. We get it. You’re THERE, we’re not.

…

Second, I check my notifications on Facebook. I rarely ever look at my feed. Truth be told, I only keep my Facebook account out of respect for the platform … aaaand in the hopes that my former crushes find my page and see the cute pics of myself that I’ve posted. It’s flawed but it’s honest. Third comes Snapchat. At first, I was against Snapchat. I didn’t get it. But once my friend Brian Mahoney (li’l shout-out for @mahone_alone) taught me how to work it, I was hooked. It’s where I document my coffee making and #NoPants life. It’s like my own reality show produced by me! I also enjoy receiving Snaps from like-minded people.

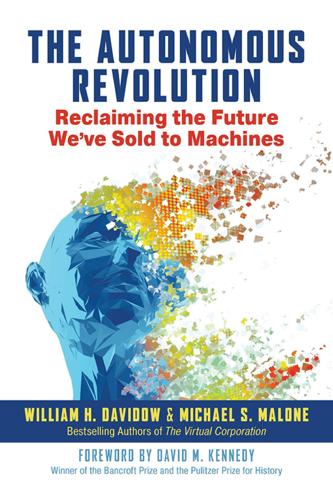

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by

William Davidow

and

Michael Malone

Published 18 Feb 2020

In many cases, the entrepreneurs of smaller companies feel that if they do not let themselves be acquired, the giant suitor will develop its own competing application and drive them out of business. That is what happened to Snapchat. The company reportedly turned down a $3 billion offer from Facebook. So Facebook added popular Snapchat-like offerings to its own messaging applications—such as new camera filters and a sharing feature called Stories.63 Snapchat still managed to go public in 2017 at $17 per share, at a market cap of about $20 billion.64 But since that time its stock has struggled, and there are many concerns about how the company will fare over the long term in the platform wars.

…

shareToken=st4499b289902f491a99df8d891ecb83ef&reflink=article_email_share&mg=prod/accounts-wsj (accessed June 27, 2019). 16. Amber Murakami-Fester, “What Are Peer-to-Peer Payments?,” NerdWallet.com, May 31, 2019, https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/banking/p2p-payment-systems/. 17. Snapchat Support, SnapChat Corporation, https://support.snapchat.com/en-US/a/snapcash-guidelines (accessed June 27, 2019). 18. PopMoney home page, https://www.popmoney.com/ (accessed June 27, 2019). 19. “Ally Bank Review: Everything You Need to Know,” The Balance, https://www.thebalance.com/ally-bank-review-315132. 20. “Why Fintech Won’t Kill Banks,” The Economist, June 17, 2015, https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2015/06/economist-explains-12 (accessed June 27, 2019). 21.

…

John Cook, “John Grisham, Stephen King and More Than 900 Other Authors Press Amazon to Solve Hachette Dispute in NYT Ad,” GeekWire, August 8, 2014, https://www.geekwire.com/2014/john-grisham-stephen-king-900-authors-press-amazon-solve-hachette-dispute/ (accessed June 27, 2019). 63. Queenie Wong, “Facebook vs. Snapchat: Competition Heats Up Between Social Media Firms,” San Jose Mercury News, March 28, 2017, https://www.mercurynews.com/2017/03/28/facebook-vs-snapchat-competition-heats-up-between-social-media-firms/ (accessed June 27, 2019). 64. Anita Balakrishnan, “Snap Closes Up 44% After Rollicking IPO,” CNBC, March 2, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/03/02/snapchat-snap-open-trading-price-stock-ipo-first-day.html (accessed June 27, 2019). 65. Nicholas Carlson, “Was $1 Billion Too Little to Ask for Instagram?

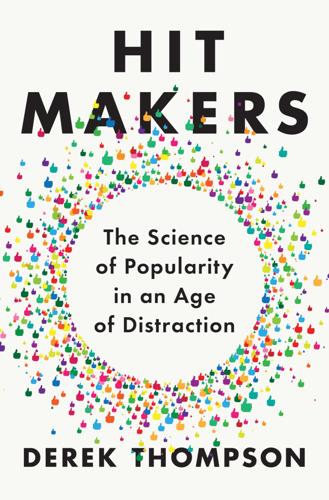

Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction

by

Derek Thompson

Published 7 Feb 2017

In other words: maps, videos, and a whole lot of talking. If you think the download counts are skewed, try the independent surveys. According to a 2014 Niche study, the most common mobile uses for teenagers are texting, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Pandora, Twitter, and phone calls. Six of the eight (texting, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and the old-fashioned telephone) are just different tools for self-expression—visual, textual, and voice. These social networks really work only when they’re big.46 There is an idea called Metcalfe’s law, which says that the value of a network is proportional to the number of its users squared.

…

But, like Disney, it is like a promiscuous vine that can live and grow in any climate. In 2016, 80 percent of BuzzFeed’s audience discovered its content somewhere other than its website—on social networks like Facebook and Snapchat, publishing partners like Apple News and Yahoo, and messaging apps like WeChat. For some consumers, BuzzFeed is a digital newspaper. For others, who find it on Snapchat, it is more like a TV company programming content for different cable networks. Content flows out and information flows in. BuzzFeed uses its distribution channels to collect information on what audiences read, watch, and share and turns those lessons into content for some other channel.

…

As communication choices abounded, modes of talking became fashionable—and then anachronistic. Corded and cordless phones connected teenagers in the 1990s. By the early 2000s, online chatting was the norm. Then centuries flipped, and the social media revolution erupted, with Friendster in 2002, MySpace in 2003, Facebook in 2004, Twitter in 2006, Whatsapp in 2009, Instagram in 2010, and Snapchat in 2011. These platforms were joined by other inventions, like Vine and Yik Yak, and modern twists on pre-alphabet pictograms like emojis, GIF keyboards, and stickers. Each of these apps and features are fundamentally pictures and words in boxes. But they all have a distinct patois and cultural context, and each represents a fashionable improvement or purposeful divergence from the previous dominant technology.

User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design Are Changing the Way We Live, Work & Play

by

Cliff Kuang

and

Robert Fabricant

Published 7 Nov 2019

And differing approaches to feedback lie behind two of the most successful startups in recent history: Instagram and Snapchat. Instagram came first, in 2010. The app initially just let you share photos and see the photos of friends to whom you were linked. Soon after it launched came the commonsense policy, popularized by Facebook, of letting your friends like your posts (and, of course, seeing how many likes your friends’ posts had gotten). That was the simple act of affirmation that the app revolved around. How many likes had you gotten? How many had your friends? Snapchat was built differently. It, too, was meant as a basic photo-sharing app.

…

If you were Instagram, that was a mechanism that could end your business altogether. And so Instagram ruthlessly adopted Snapchat’s feedback philosophy, inserting a strip of “stories” at the top of the app, which let users share photos without the possibility of getting likes, and with the only way of replying being to send a direct message. It worked. Instagram Stories was wildly successful, used by 400 million people a day within a year of launch, helping Instagram nudge its average user time ever upward. You could talk about Snapchat and Instagram as the story of two billion-dollar apps that gave people new ways to entertain themselves, and one another.

…

In the user-friendly era, in which it is assumed that new products and apps shouldn’t require much instruction, Autopilot conveyed a muddy sense of what it could and could not do—with sometimes fatal consequences. 2016: INSTAGRAM STORIES In 2016, after noticing that users were becoming more self-conscious about posting to Instagram, the company copied the disappearing-messages feature of Snapchat, to spectacular success. Just a few years before, the iPod click wheel had proved that a user-experience innovation could ignite widespread adoption; Snapchat did the same. But in an era of digital products, those innovations are nearly impossible to defend from copycats for long. 2016: GENERAL DATA PROTECTION REGULATION, European Union EU decision makers opened up a new frontier in user-friendly design by enacting a set of laws intended to give users control over their personal data.

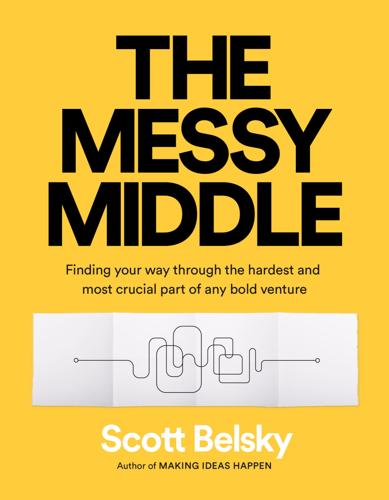

The Messy Middle: Finding Your Way Through the Hardest and Most Crucial Part of Any Bold Venture

by

Scott Belsky

Published 1 Oct 2018

If so, you should consider taking the same tactic yourself. In 2016 and 2017, Instagram infamously copied Snapchat’s tactics over and over again. Both apps were playing in the same field, and Instagram used what Snapchat learned to get ahead of it in its own game. Instagram implemented Snapchat’s “stories” and augmented-reality features, like facial overlays, because these tactics were directly aligned with its strategy: to host the media friends share with one another. Instagram was getting ideas from Snapchat, but these tactics advanced their strategy rather than diverted it. Sometimes the thing you admire most in your competitor isn’t smart or scalable.

…

The only time you should force new behaviors or terminology is when they enable a unique and important value in your product. For example, Snapchat was the first social network that would open on the camera view when you clicked on the app instead of other competitive products like Instagram and Facebook that open on a feed of others’ content. This behavior struck new users as foreign, but it retrained users for an entirely different kind of social experience. Snapchat aspired to be more of a camera than an app, and launching the product in camera mode sent a strong and differentiating message to its users that helped distinguish Snapchat from other social apps—as well as the kind of content created with it.

…

Empathy for those suffering the problem must come before your passion for the solution. Consider the rise of the popular camera and messaging app Snapchat. There were a lot of start-ups trying to help people share photos and hoping to compete with Facebook. But founder Evan Spiegel recognized the unique insecurities and preferences of its first users: teenagers. At the time of its founding in 2011, teenagers were especially sensitive to leaving a trail of data online that their parents and teachers could see. The idea of ephemeral content that would quickly disappear relieved the anxieties of these teenage users. Snapchat was also empathetic to the fact that many of these teenagers had hand-me-down smartphones with limited storage and cracked screens.

Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech

by

Sara Wachter-Boettcher

Published 9 Oct 2017

Siri’s responses to a series of queries in March 2016. (Sara Wachter-Boettcher) Or in August 2016, when Snapchat launched a new face-morphing filter—one it said was “inspired by anime.” In reality, the effect had a lot more in common with Mickey Rooney playing I. Y. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s than a character from Akira. The filter morphed users’ selfies into bucktoothed, squinty-eyed caricatures—the hallmarks of “yellowface,” the term for white people donning makeup and masquerading as Asian stereotypes. Snapchat said that this particular filter wouldn’t be coming back, but insisted it hadn’t done anything wrong—even as Asian users mounted a campaign to delete the app.

…

As Adrienne LaFrance, writing in the Atlantic, put it, “The simplest explanation is that people are conditioned to expect women, not men, to be in administrative roles” 9 (just think about who you picture when you hear the term “secretary”). Or let’s look once more at Snapchat. In addition to the so-called “anime-inspired” filter we saw earlier, the app is known for releasing filters that purport to make you prettier, like the popular “beauty” and “flower crown” features. These filters smooth your skin, contour your face so your cheekbones pop, and . . . make you whiter.10 Why is whiter the default standard for beauty? Well, that’s a complex cultural question—but I doubt it’s one that the three white guys from Stanford who founded Snapchat ever thought about. These might seem like small things, but default settings can add up to be a big deal—both for an individual user like Messer, and for the culture at large.

…

Adrienne LaFrance, “Why Do So Many Digital Assistants Have Feminine Names?” Atlantic, March 30, 2016, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/03/why-do-so-many-digital-assistants-have-feminine-names/475884. 10. For a whole ton of examples, see Neha Prakash, “Snapchat Faces an Outcry against ‘Whitewashing’ Filters,” Mashable, May 16, 2016, http://mashable.com/2016/05/16/snapchat-whitewashing/#pLqUZA7KJuqs. 11. Jessica Nordell, “Stop Giving Digital Assistants Female Voices,” New Republic, June 23, 2016, https://newrepublic.com/article/134560/stop-giving-digital-assistants-female-voices. 12. Todd Rose, The End of Average: How to Succeed in a World That Values Sameness (New York: HarperCollins, 2016). 13.

The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health--And How We Must Adapt

by

Sinan Aral

Published 14 Sep 2020

As a result, “the network effects insulating digital platforms from competitive pressure will be mitigated….Individuals could switch between platforms based on their tastes and preferences as well as the innovations devised by different platforms….The point is that the ability to earn money from a user’s attention will become more contestable as a result of identity portability.” Second, social media services differ from phone calls. Text and voice exchanges are standardized and therefore easier to make interoperable. But messages on Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, and Snapchat are harder to seamlessly exchange across the different networks. Messages on Snapchat disappear, while messages on Facebook persist. Messages on Twitter are public and limited to 240 characters, while messages on WhatsApp are private and unlimited in length. While protocols for distinct message types could be developed, the complexity of interoperability in this context certainly exceeds that of the exchange of voice calls and text messages on mobile phones.

…

The Hype Machine Every minute of every day, our planet now pulses with trillions of digital social signals, bombarding us with streams of status updates, news stories, tweets, pokes, posts, referrals, advertisements, notifications, shares, check-ins, and ratings from peers in our social networks, news media, advertisers, and the crowd. These signals are delivered to our always-on mobile devices through platforms like Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter, and they are routed through the human social network by algorithms designed to optimize our connections, accelerate our interactions, and maximize our engagement with tailored streams of content. But at the same time, these signals are much more transformative—they are hypersocializing our society, scaling mass persuasion, and creating a tyranny of trends.

…

I was the chief scientist at SocialAmp, one of the first social commerce analytics companies (until its sale to Merkle in 2012) and at Humin, a social platform that The Wall Street Journal called the first “Social Operating System” (until its sale to Tinder in 2016). I have worked directly with senior executives at Facebook, Yahoo!, Twitter, LinkedIn, Snapchat, WeChat, Spotify, Airbnb, SAP, Microsoft, Walmart, and The New York Times. Along with my longtime friend Paul Falzone, I’m a founding partner at Manifest Capital, an investment firm that helps young companies grow into the Hype Machine. From this perch, I evaluate hundreds of companies a year and get to look around the corner at what’s next.

The Best Interface Is No Interface: The Simple Path to Brilliant Technology (Voices That Matter)

by

Golden Krishna

Published 10 Feb 2015

As a reporter at *The Verge,* I interviewed Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel before the launch of the company’s video chat and texting features. Spiegel said something that really stuck out to me: “The biggest constraint of the next 100 years of computing is the idea of metaphors,” he said. “For Snapchat, the closer we can get to ‘I want to talk to you’—that emotion of wanting to see you and then seeing you — the better and better our product and our view of the world will be.” Instead of allowing you to ring friends for a video chat, as with FaceTime or Skype, Snapchat forces both users to be present inside a chat window before video can begin.

…

Instead of allowing you to ring friends for a video chat, as with FaceTime or Skype, Snapchat forces both users to be present inside a chat window before video can begin. So, instead of texting someone to set up a FaceTime call, you can simply chat them on Snapchat, and if they log on, you can start a video chat when you’re both in the same conversation. The “Hey, want to chat?” text replaces the ring entirely. You might have thought that Snapchat’s mission was to bring “ephemeral,” disappearing messages to the masses, when it was only one facet of a bigger idea that Spiegel had been stewing over. He had been thinking about digitally replicating the ways we talk in real life — ephemerality just happened to be one means of doing so.

…

People are inherently drawn to new ideas and not old, derivative ones. People are drawn to hope for better solutions, even if they manifest themselves in tiny, seemingly insignificant ways. *Ring, ring.* Ellis Hamburger was a reporter for the technology news and culture website The Verge from 2012–2015. Now he’s working in marketing at Snapchat. Contents Welcome 1 Introduction Why did you buy this book? Um, why did you buy this book again? 2 Screen-based Thinking Let’s make an app! Tackle a global issue? Improve our lives? No, no. When smart people get together in Silicon Valley they often brainstorm, “What app can we make?”

Talk on the Wild Side

by

Lane Greene

Published 15 Dec 2018