Stanislav Petrov

description: a former lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Air Defence Forces who prevented a possible nuclear war in 1983 by correctly identifying a missile warning as a false alarm

34 results

Risk: A User's Guide

by

Stanley McChrystal

and

Anna Butrico

Published 4 Oct 2021

five Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” paused in shock: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” They understood well: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov”; Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’ ” Still, he knew the time: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” Petrov later explained: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov”; Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’ ” strange for the Americans to launch: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov”; Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’ ” “50-50” estimate of probability: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” early warning satellite constellation: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov”; Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’ ” he received a reprimand: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.”

…

September 26, 1983: Sewell Chan, “Stanislav Petrov, Soviet Officer Who Helped Avert Nuclear War, Is Dead at 77,” The New York Times, September 18, 2017, https://nytimes.com/2017/09/18/world/europe/stanislav-petrov-nuclear-war-dead.html. no direct authority to initiate: David Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut,’ ” The Washington Post Foreign Service, February 10, 1999, p. A19, https://washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/coldwar/soviet10.htm; Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” single phone call of warning: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” five Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.” paused in shock: Chan, “Stanislav Petrov.”

…

—Carl Sagan, astronomy professor, science writer, host of THE PBS TELEVISION SERIES cosmos Technology raises a new question: Who or what is in control? Sitting on a Hot Frying Pan Rule breaking makes for great storytelling: American children know the tale of the Boston Tea Party and lunch counter sit-ins of the 1960s from a young age, just as Chinese citizens know the story of Chairman Mao and the Long March. But the name Stanislav Petrov is at most a historical curiosity, despite his world-changing act of disobedience. Arguably, September 26, 1983, witnessed the single most important act of insubordination in the history of human civilization. On that fateful day, Lieutenant Colonel Petrov of the Soviet Union’s Air Defense Forces was stationed at a command center outside Moscow.

Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War

by

Paul Scharre

Published 23 Apr 2018

Introduction: The Power Over Life and Death 1 shot down a commercial airliner: Thom Patterson, “The downing of Flight 007: 30 years later, a Cold War tragedy still seems surreal,” CNN.com, August 31, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2013/08/31/us/kal-fight-007-anniversary/index.html. 1 Stanislav Petrov: David Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut,’ ” Washington Post, February 10, 1999, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/coldwar/shatter021099b.htm. 1 red backlit screen: Pavel Aksenov, “Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who May Have Saved the World,” BBC.com, September 26, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24280831. 2 five altogether: Ibid. 2 Petrov had a funny feeling: Hoffman, “I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’” 2 Petrov put the odds: Aksenov, “Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who May Have Saved the World.” 5 Sixteen nations already have armed drones: The United States, United Kingdom, Israel, China, Nigeria, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Turkey.

…

Fearing retaliation, the Soviet Union was on alert. The Soviet Union deployed a satellite early warning system called Oko to watch for U.S. missile launches. Just after midnight on September 26, the system issued a grave report: the United States had launched a nuclear missile at the Soviet Union. Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov was on duty that night in bunker Serpukhov-15 outside Moscow, and it was his responsibility to report the missile launch up the chain of command to his superiors. In the bunker, sirens blared and a giant red backlit screen flashed “launch,” warning him of the detected missile, but still Petrov was uncertain.

…

Yet computers still fall far short of humans in understanding context and interpreting meaning. AI programs today can identify objects in images, but can’t draw these individual threads together to understand the big picture. Some decisions in war are straightforward. Sometimes the enemy is easily identified and the shot is clear. Some decisions, however, like the one Stanislav Petrov faced, require understanding the broader context. Some situations, like the one my sniper team encountered, require moral judgment. Sometimes doing the right thing entails breaking the rules—what’s legal and what’s right aren’t always the same. THE DEBATE Humanity faces a fundamental question: should machines be allowed to make life-and-death decisions in war?

1983: Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink

by

Taylor Downing

Published 23 Apr 2018

Serpukhov-15 could provide around twelve minutes’ additional warning time of an attack over the radars stationed along the northern fringes of the Soviet Union. These extra minutes would be vital in giving the leadership time in which to respond appropriately; and to get to a shelter.4 At 7 p.m. on Monday, 26 September 1983, Lieutenant-Colonel Stanislav Petrov arrived at the compound’s command centre having been asked at the last minute to take over a shift as another officer had reported in ill. At the centre he spent an hour talking with colleagues whose shift was finishing, receiving the latest reports and updates from them. Then Petrov ordered his team of twelve specialist officers to salute the Soviet flag and take up their positions in the control room.

…

By the time the first journalists got to Petrov he was living a wretched life in a ghastly tower block in a Moscow suburb. But on the black and white television set in his tiny apartment there was a small statue of a globe resting inside an open hand which Petrov proudly pointed out to visitors. It was inscribed with a few words from Kofi Annan, the Secretary General of the United Nations: ‘To Stanislav Petrov, The Man Who Saved the World’. By the autumn of 1983, the two superpowers possessed about 18,400 nuclear warheads. They were on the tips of giant intercontinental missiles held in silos spread right across North America and the Soviet Union. Submarines carrying nuclear missiles crossed every ocean, and heavy bombers fully armed with nuclear bombs were constantly on stand-by.

…

But it also made the possibility of miscalculation even greater. Only six weeks before, the Soviet early warning system had malfunctioned by interpreting reflections of the sun on clouds in the Midwest of the United States as a sign that missiles had been launched. On that occasion the cool head of Stanislav Petrov had defused the situation, but there was no guarantee that the officer on duty would respond in the same way to another early warning. The entire Soviet nuclear launch system was resting on a knife edge. Either man or machine could interpret a situation wrongly and the consequence would be nuclear war by miscalculation.

Know Thyself

by

Stephen M Fleming

Published 27 Apr 2021

Some psychologists restrict the term self-awareness to mean bodily self-awareness, or awareness of the location and appearance of the body, but here I am generally concerned with awareness of mental states. Chapter 1: How to Be Uncertain 1. Jonathan Steele, “Stanislav Petrov Obituary,” The Guardian, October 11, 2017, www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/11/stanislav-petrov-obituary. 2. Green and Swets (1966). 3. The seeds of Bayes’s rule were first identified by the eleventh-century Arabic mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, developed by English clergyman and mathematician Thomas Bayes in 1763, and applied to a range of scientific problems by the eighteenth-century French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace.

…

PART I BUILDING MINDS THAT KNOW THEMSELVES 1 HOW TO BE UNCERTAIN The other fountain [of] ideas, is the perception of the operation of our own minds within us.… And though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called internal sense. —JOHN LOCKE, Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book II Is something there, or not? This was the decision facing Stanislav Petrov one early morning in September 1983. Petrov was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Defense Forces and in charge of monitoring early warning satellites. It was the height of the Cold War between the United States and Russia, and there was a very real threat that long-range nuclear missiles could be launched by either side.

The Alignment Problem: Machine Learning and Human Values

by

Brian Christian

Published 5 Oct 2020

The world will be, for good or ill, full of these algorithmic two-year-olds, walking up to us, opening the doors they think we might want opened, trying, in their various ways, to help. 9 UNCERTAINTY Most of the greatest evils that man has inflicted upon man have come through people feeling quite certain about something which, in fact, was false. —BERTRAND RUSSELL1 I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken. —OLIVER CROMWELL The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right. —LEARNED HAND It was September 26, 1983, just after midnight, and Soviet duty officer Stanislav Petrov was in a bunker outside of Moscow, monitoring the Oko early-warning satellite system. Suddenly the screen lit up and sirens began howling. There was an LGM-30 Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile inbound, it said, from the United States. “Giant blood-red letters appeared on our main screen,” he says.

…

I marvel that this manuscript was written using typesetting software more than 40 years old, and for which none other than Arthur Samuel himself wrote the documentation. We really do stand on the shoulders of giants. Humbly, I want to acknowledge those who passed away during the writing of this book whose voices I would have loved to include, and whose ideas are nevertheless present: Derek Parfit, Kenneth Arrow, Hubert Dreyfus, Stanislav Petrov, and Ursula K. Le Guin. I want to express a particular gratitude to the University of California, Berkeley. To CITRIS, where I was honored to be a visiting scholar during the writing of this book, with very special thanks to Brandie Nonnecke and Camille Crittenden; to the Simons Institute for the Theory of Computing, in particular Kristin Kane and Richard Karp; to the Center for Human-Compatible AI, in particular Stuart Russell and Mark Nitzberg; and to the many brilliant and spirited members and visitors of the CHAI Workshop.

…

See Bateson, Nettle, and Roberts, “Cues of Being Watched Enhance Cooperation in a Real-World Setting,” and Heine et al., “Mirrors in the Head.” 58. Bentham, “Letter to Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville.” 59. Bentham, “Preface.” CHAPTER 9. UNCERTAINTY 1. Russell, “Ideas That Have Harmed Mankind.” 2. “Another Day the World Almost Ended.” 3. Aksenov, “Stanislav Petrov.” 4. Aksenov. 5. Hoffman, “‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut.’ ” 6. Nguyen, Yosinski, and Clune, “Deep Neural Networks Are Easily Fooled.” For a discussion of the confidence of predictions of neural networks, see Guo et al., “On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks.” 7. See Szegedy et al., “Intriguing Properties of Neural Networks,” and Goodfellow, Shlens, and Szegedy, “Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples.”

The Rationalist's Guide to the Galaxy: Superintelligent AI and the Geeks Who Are Trying to Save Humanity's Future

by

Tom Chivers

Published 12 Jun 2019

There’s no reception, just a bunch of faintly elderly sofas and bean bags. One wall is dominated by a vast picture of the Earth from space; on another there is a whiteboard, covered in equations, as well as an H.P. Lovecraft-ish slogan (‘Do not anger timeless beings with unspeakable names’), and a jaunty little reminder to ‘Thank Stanislav Petrov!’ (Petrov, if you’re unfamiliar with the name, was a Russian military officer who is credited with preventing a major nuclear war being triggered in September 1983, more of which later.) There is also an expensive-looking road bike with drop handlebars and a pannier rack, propped up against a water cooler, with a post-it note saying: ‘Is this your bike?

…

That’s a lot lower than the peak number of roughly 65,000 in the late 1980s, but still easily enough to cause a spectacular nuclear winter, and possibly end human life. And we have come astonishingly close to disaster. One of the Rationalist community’s heroes is a former Soviet Air Defence Force officer, Stanislav Petrov, whom I mentioned earlier and who died in 2017. On 23 September 1983 Lieutenant-Colonel Petrov was on duty as the watch officer of the USSR’s missile early-warning system, at a time of enormous geopolitical tension: three weeks earlier, a US congressman had died in a Korean airliner shot down by a Soviet interceptor, and both sides in the Cold War had recently deployed nuclear weapons in threatening positions.

…

Superforecasting was by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner, and was a write-up of Tetlock’s work as a professor of political psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1984 Tetlock, a recently tenured professor, was asked to work on a new committee appointed by the National Academy of Sciences. Its goal was to help stop nuclear war. Tensions were enormously high between the two superpowers; Stanislav Petrov, whom you may remember from the section on existential risks, had (although no one on the committee would have known) quite possibly saved the world just a few months before. Tetlock sat on the committee with other well-respected social scientists, who argued over how best to reduce the risk of confrontation.

Who Rules the World?

by

Noam Chomsky

The exercises “almost became a prelude to a preventative nuclear strike,” according to an account in the Journal of Strategic Studies.10 It was even more dangerous than that, as we learned in the fall of 2013, when the BBC reported that right in the midst of these world-threatening developments, Russia’s early-warning systems detected an incoming missile strike from the United States, sending its nuclear system onto the highest-level alert. The protocol for the Soviet military was to retaliate with a nuclear attack of its own. Fortunately, the officer on duty, Stanislav Petrov, decided to disobey orders and not report the warnings to his superiors. He received an official reprimand. And thanks to his dereliction of duty, we’re still alive to talk about it.11 The security of the population was no more a high priority for Reagan administration planners than for their predecessors.

…

The Pentagon’s risky measures included sending U.S. strategic bombers over the North Pole to test Soviet radar, and naval exercises in wartime approaches to the USSR where U.S. warships had previously not entered. Additional secret operations simulated surprise naval attacks on Soviet targets.”11 We now know that the world was saved from likely nuclear destruction in those frightening days by the decision of a Russian officer, Stanislav Petrov, not to transmit to higher authorities the report of automated detection systems that the USSR was under missile attack. Accordingly, Petrov takes his place alongside Russian submarine commander Vasili Arkhipov, who, at a dangerous moment of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, refused to authorize the launching of nuclear torpedoes when the subs were under attack by U.S. destroyers enforcing a quarantine.

…

Fischer, “A Cold War Conundrum: The 1983 Soviet War Scare,” Center for the Study of Intelligence, 7 July 2008, https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/a-cold-war-conundrum/source.htm; Dmitry Dima Adamsky, “The 1983 Nuclear Crisis—Lessons for Deterrence Theory and Practice,” Journal of Strategic Studies 36, no.1 (2013): 4–41. 11. Pavel Aksenov, “Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who May Have Saved the World,” BBC News Europe, 26 September 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24280831. 12. Eric Schlosser, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety (New York: Penguin, 2013). 13. President Bill Clinton, Speech before the UN General Assembly, 27 September 1993, http://www.state.gov/p/io/potusunga/207375.htm; Secretary of Defense William Cohen, Annual Report to the President and Congress: 1999 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 1999) http://history.defense.gov/Portals/70/Documents/annual_reports/1999_DoD_AR.pdf. 14.

Nuclear War: A Scenario

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 25 Mar 2024

The radars here receive data from Tundra space satellites and it is the job of the Serpukhov-15 commander to relay that information up the chain of command. The Russian Ministry of Defense has had officers stationed at the Serpukhov-15 facility for more than fifty years. As in America, there have been terrifying false alarms. Once, in 1983, a lieutenant colonel named Stanislav Petrov was the commander in charge when satellite data indicated there were five American ICBMs on their way to strike Moscow with nuclear weapons. For reasons having to do with human intuition, Petrov became suspicious of that attack information. Years later, he told Washington Post reporter David Hoffman what he was thinking at the time.

…

“I had a funny feeling in my gut,” Petrov said, asking himself, Who starts a nuclear war against another superpower with just five ICBMs? In 1983, Petrov made the decision to interpret the early-warning signal as a “false alarm,” he said, thereby not sending a report up the chain of command. For his well-placed skepticism, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov famously became known as “the man who saved the world from nuclear war.” But in this moment of intense nuclear crisis in this scenario—with the U.S. under nuclear attack, and a slew of ICBMs having just launched from a missile field in Wyoming—the reaction of the present-day commander at Serpukhov-15 is different than Petrov’s reaction was in 1983.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT became suspicious: Peter Anthony, dir., The Man Who Saved the World, Statement Films, 2013. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Petrov: David Hoffman, “ ‘I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut,’ ” Washington Post Foreign Service, February 10, 1999; “Person: Stanislav Petrov,” Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, National Park Service, 2007. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “look like one hundred:” Interview with Ted Postol. I also discussed this with Pavel Podvig. In 1983, Tundra did not yet exist. The old system, known as Oko (Eye), was known to fault.

Hello World: Being Human in the Age of Algorithms

by

Hannah Fry

Published 17 Sep 2018

There will be times when we have to hand over control to the unknown, even while knowing that the algorithm is capable of making mistakes. Times when we are forced to weigh up our own judgement against that of the machine. When, if we decide to trust our instincts instead of its calculations, we’re going to need rather a lot of courage in our convictions. When to over-rule Stanislav Petrov was a Russian military officer in charge of monitoring the nuclear early warning system protecting Soviet airspace. His job was to alert his superiors immediately if the computer indicated any sign of an American attack.34 Petrov was on duty on 26 September 1983 when, shortly after midnight, the sirens began to howl.

…

Kristine Phillips, ‘The former Soviet officer who trusted his gut – and averted a global nuclear catastrophe’, Washington Post, 18 Sept. 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/09/18/the-former-soviet-officer-who-trusted-his-gut-and-averted-a-global-nuclear-catastrophe/?utm_term=.6546e0f06cce. 35. Pavel Aksenov, ‘Stanislav Petrov: the man who may have saved the world’, BBC News, 26 Sept. 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24280831. 36. Ibid. 37. Stephen Flanagan, Re: Accident at Smiler Rollercoaster, Alton Towers, 2 June 2015: Expert’s Report, prepared at the request of the Health and Safety Executive, Oct. 2015, http://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~ijackson/2016/Expert%20witness%20report%20from%20Steven%20Flanagan.pdf. 38.

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy

by

David Hoffman

Published 1 Jan 2009

See Bunn, p. 116. 11 Valentin Yevstigneev, interview, Feb. 10, 2005. Yevstigneev's comment repeated the claim made in an article published May 23, 2001, in the Russian newspaper Nezavisamaya Gazeta. Stanislav Petrov, the general in charge of chemical weapons, was a coauthor. The piece claimed the Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak was the result of "subversive activity" against the Soviet Union. Stanislav Petrov et al., "Biologicheskaya Diversia Na Urale" [Biological Sabotage in the Urals], NG, May 23, 1001. 12 The closed military facilities are: the Scientific-Research Institute of Microbiology of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, Kirov, which is the main biological weapons facility of the military; the Virology Center of the Scientific-Research Institute of Microbiology of the Ministry of Defense, Sergiev Posad; and the Department of Military Epidemiology of the Scientific Research Institute of Microbiology of the Ministry of Defense, Yekaterinburg. 13 When the United States and Russia signed the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997 they promised to destroy stocks of chemical weapons by 2012.

…

But he also gave the pathologists a private signal to hide and protect their evidence. Nikiforov later died of a heart attack. "We are certain that he knew the truth," Grinberg said.9 But the people of the Soviet Union and the outside world did not. II. Night Watch for Nuclear War The shift change began at 7 P.M. on September 26, 1983. Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant colonel, arrived at Serpukhov-15, south of Moscow, a top-secret missile attack early-warning station, which received signals from satellites. Petrov changed from street clothes into the soft uniform of the military space troops of the Soviet Union. Over the next hour, he and a dozen other specialists asked questions of the outgoing officers.

…

Little is known about the disposition in Russia of the thousands of tactical nuclear weapons removed from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics after the 1991 Bush-Gorbachev initiative. They may be in storage or deployed; they have never been covered by any treaty, nor any verification regime, and the loss of just one could be catastrophic.2 Another step would be to take the remaining strategic nuclear weapons off launch-ready alert. When Stanislav Petrov faced the false alarm in 1983, launch decisions had to be made in just minutes. Today, Russia is no longer the ideological or military threat the Soviet Union once was; nor does the United States pose such a threat to Russia. Americans invested much time and effort to assist Russia's leap to capitalism in the 1990s--should we aim our missiles now at the very stock markets in Moscow we helped design?

I, Warbot: The Dawn of Artificially Intelligent Conflict

by

Kenneth Payne

Published 16 Jun 2021

The problem, it seems, was the moon: the ultra-sensitive radar was picking up an echo from its surface and attributing that to an incoming intercontinental ballistic missile. Presumably the boffins eventually managed to ratchet down the sensitivity to a more appropriate level. A similar panic happened on the other side of the Iron Curtain, this more widely known. In 1982 at a time of heightened tension in the Cold War, an unflappable Soviet Colonel, Stanislav Petrov chose to ignore the alarm from his new state-of-the-art early warning system which signalled that the US had launched intercontinental missiles. Happily, in both cases, humans were resolutely in the loop, and sufficiently sceptical about the ability of technology to interpret reality. Ellsberg features again in our discussion of strategic AI, thanks to his vivid depiction of his job as a mid-level Pentagon functionary in the early 1960s.4 In this pre-computer era, the job of the intelligence analyst involved wading through a large stack of papers.

…

In the heat of the moment, we set doubts aside and let ourselves be guided by the machine, like the captain of the USS Vincennes failing to interrogate the ship’s targeting computer. On the other hand, in some circumstances, there is often a reluctance to trust the workings of an intelligent machine. That might especially be the case if it goes against our ingrained preferences. Stanislav Petrov famously refusing to believe his faulty nuclear warning computer is the shining example here. Which one of those two instincts predominates in any centaur strategy team is a question of psychology, not just computer science. The US Army is testing it out already—at the tactical level. In a fascinating recent experiment, the Army Research Lab set up cameras pointed at truck drivers to measure their reactions as they drove a convoy.10 The humans could decide whether to engage their AI assistant, and then their responses to its decisions could be measured with facial recognition software and compared to their personality profiles.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by

Nate Silver

Published 12 Aug 2024

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT next twenty years: This can be calculated as 1 − (1 − 0.037)^20, which equals a 53 percent chance that nuclear weapons would be used at least once in the next 20 years. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT John F. Kennedy: Ord, The Precipice, 26. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Stanislav Petrov: Dylan Matthews, “40 Years Ago Today, One Man Saved Us from World-Ending Nuclear War,” Vox, September 26, 2018, vox.com/2018/9/26/17905796/nuclear-war-1983-stanislav-petrov-soviet-union. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “bomb is shit”: Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, 938. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “just announce to the enemy”: T. C. Schelling, “The Threat That Leaves Something to Chance,” RAND Corporation, 1959, doi.org/10.7249/HDA1631-1.

…

John F. Kennedy estimated after the Cuban Missile Crisis that there had been somewhere between a 1-in-3 and a 1-in-2 chance that the conflict would go nuclear. And in September 1983, the only thing preventing a Russian nuclear launch may have been the canny judgment of Soviet lieutenant colonel Stanislav Petrov, who correctly inferred that a report of a U.S. ICBM attack was a false alarm, avoiding an escalation that would have triggered Soviet nuclear protocols. But if nuclear deterrence has worked out well in practice so far, it’s nonetheless an inherently paradoxical concept. And ironically, one reason deterrence may have worked is because River types misunderstand human nature.

…

“One cannot just announce to the enemy that yesterday one was only about 2 percent ready to go to all-out war but today it is 7 percent and they had better watch out,” he wrote. But you can leave something to chance. When tensions escalate, you never know what might happen. Decisions are left in the hands of vulnerable human beings facing incalculable pressure. Not all of them will have the presence of mind of Stanislav Petrov. “If you put tactical nuclear weapons on the border, you’re not saying that I’m going to order them to be used. That may not be reasonable or believable. But if you attack, the local commander has control of those and he just might. That’s a threat that leaves something to chance,” said Sagan.

The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare in the Robot Age

by

Roger Bootle

Published 4 Sep 2019

At a time when tensions were already high because of the shooting down by the Soviet Union of a Korean aircraft, killing 269 passengers, a Soviet early-warning system reported the launch by the USA of five missiles at the Soviet Union. The Soviet officer responsible for this early-warning system, Stanislav Petrov, had minutes to decide what to do. The protocol required that he should report this as a nuclear attack. Instead, he relied on his gut instinct. If America was really launching a nuclear attack, he reasoned, why had it sent only five missiles? So, he decided that it was a false alarm and took no action.

…

It turned out that a Soviet satellite had misread the sun’s reflections off cloud tops for flares from rocket engines. It is now widely acknowledged that Petrov’s judgment saved the world from nuclear catastrophe. Despite involving the saving of the world from a real disaster, this true story has a bitter ending. Stanislav Petrov was sacked for disobeying orders and lived the rest of his life in drab obscurity. (That was the Soviet Union for you.) Could we imagine entrusting the sort of judgment that Petrov made to some form of AI? This conjures up the scenario depicted in the now very old but still rewarding film Dr.

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by

Rodrigo Aguilera

Published 10 Mar 2020

A senior State Department official was quoted during this time as saying that “false alerts of this kind are not a rare occurrence” and that there is a “complacency about handling them that disturbs me”.3 And in September 1983, probably the second closest call came when another Soviet officer, Stanislav Petrov, disobeyed protocol after an early warning system detected a US missile strike which he deliberately failed to report to his superiors. It was, as he correctly assumed, a false alarm. He later admitted that he was only “50–50” sure at the time that the attack was not real.4 What is arguably more complacent is the assumption — possibly a lethal one for a large chunk of humanity — that a repeat of this situation could not take place again.

…

Rawls actually mentions Sibley in a footnote. 53 Edmunson, W., John Rawls: Reticent Socialist (Cambridge University Press, 2017) Part III: The End of the End of History Chapter Seven: The Evil That Men Do 1 Lloyd, M., “Soviets Close to Using A-Bomb in 1962 Crisis, Forum Is Told”, Boston Globe, 13 Oct. 2002, http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/cold-war/sovietsbomb.htm 2 Pinker, S., Enlightenment Now, pg. 312 3 “False Warnings of Soviet Missile Attacks during 1979-80 Led to Alert Actions for U.S. Strategic Forces”, National Security Archive, 1 Mar. 2012, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb371/ 4 Aksenov, P., “Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who May Have Saved the World”, BBC News, 26 Sep. 2013, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24280831 5 Roser, M., “Nuclear Weapons”, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/nuclear-weapons 6 Nolen, S., “Don’t Talk to Me About Justice”, Globe and Mail, 3 Apr. 2004, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/dont-talk-to-me-about-justice/article1135480/ 7 “More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S.”, Pew Research Center, 19 Nov. 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s/ 8 Gomez, J.M et al., “The Phylogenic Roots of Human Violence”, Nature, 538, 13 Oct. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19758 9 Ibid. 10 Falk, D., and Hildebolt, C., “Annual War Deaths in Small-Scale versus State Societies Scale with Population Size Rather than Violence”, Current Anthropology, 58(6), Dec. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1086/694568 11 Fazal, T.M., “Dead Wrong?

Surviving AI: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence

by

Calum Chace

Published 28 Jul 2015

Most people are aware that the world came close to this annihilation during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962; fewer know that we have also come close to a similar fate another four times since then, in 1979, 1980, 1983 and 1995. (52) In 1962 and 1983 we were saved by individual Soviet military officers who decided not to follow prescribed procedure. Today, while the world hangs on every utterance of Justin Bieber and the Kardashian family, relatively few of us even know the names of Vasili Arkhipov and Stanislav Petrov, two men who quite literally saved the world. Perhaps this survival illustrates our ingenuity. There was an ingenious logic in the repellent but effective doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD). More likely we have simply been lucky. We have time to rise to the challenge of superintelligence – probably a few decades.

Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-Connected World

by

Bruce Schneier

Published 3 Sep 2018

Future of Life Institute (1 Feb 2016), “Accidental nuclear war: A timeline,” https://futureoflife.org/background/nuclear-close-calls-a-timeline. 95The Cuban Missile Crisis is probably: Benjamin Schwarz (1 Jan 2013), “The real Cuban missile crisis,” Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/01/the-real-cuban-missile-crisis/309190. 95although the 1983 false alarm is a close second: Sewell Chan (18 Sep 2017), “Stanislav Petrov, Soviet officer who helped avert nuclear war,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/18/world/europe/stanislav-petrov-nuclear-war-dead.html. 95although much less damaging than: Laura Geggel (9 Feb 2016), “The odds of dying,” Live Science, https://www.livescience.com/3780-odds-dying.html. 95But instead of regarding it as: As amazing as it seems today, immediately after 9/11, people actually believed that terrorist attacks of that magnitude would happen every few months.

What We Owe the Future: A Million-Year View

by

William MacAskill

Published 31 Aug 2022

Upon further investigation, they realized a training tape designed to simulate a Soviet nuclear strike had been accidentally playing on the command centre screens. Just four years later, during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and Soviet Union, a similar false alarm took place in a Soviet command centre after a Soviet early-warning system detected five incoming nuclear missiles.52 The officer on duty, Stanislav Petrov, was sceptical that a US first strike would involve just five nuclear missiles, and he couldn’t find evidence of the missile’s vapor trails. Based on this alone, he reasoned that the warning system must have been mistaken and correctly reported the warning as a false alarm. If he had not, Soviet protocol was to launch a counterstrike, though it is unclear whether those higher in command would have believed that it was not a false alarm.

…

These changes would also have impacted the timing of further reproductive events, until at some point in the future, the identities of everyone who is born is different than they would have been. And this is all because of small decisions like which route home your parents took from work one day. I dedicated my first book, Doing Good Better, to Peter Singer, Toby Ord, and Stanislav Petrov, and I said that “without [them] this book would not have been written.” But the book also would not have been written were it not for Jesus, Hitler, or any random English peasant in the fifteenth century. In time travel stories, small actions in the past often result in radical changes in the present.

Because We Say So

by

Noam Chomsky

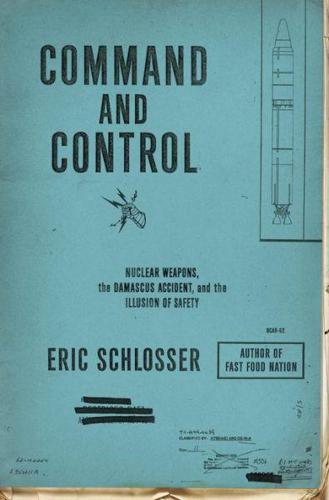

The NATO exercise “almost became a prelude to a preventative [Russian] nuclear strike,” according to an account last year by Dmitry Adamsky in the JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC STUDIES. Nor was this the only close call. In September 1983, Russia’s early-warning systems registered an incoming missile strike from the United States and sent the highest-level alert. The Soviet military protocol was to retaliate with a nuclear attack of its own. The Soviet officer on duty, Stanislav Petrov, intuiting a false alarm, decided not to report the warnings to his superiors. Thanks to his dereliction of duty, we’re alive to talk about the incident. Security of the population was no more a high priority for Reagan planners than for their predecessors. Such heedlessness continues to the present, even putting aside the numerous near-catastrophic accidents, reviewed in a chilling new book, COMMAND AND CONTROL: NUCLEAR WEAPONS, THE DAMASCUS ACCIDENT, AND THE ILLUSION OF SAFETY, by Eric Schlosser.

On the Future: Prospects for Humanity

by

Martin J. Rees

Published 14 Oct 2018

Arkhipov held out against such action—and thereby avoided triggering a nuclear exchange that could have escalated catastrophically. Post-Cuba assessments suggest that the annual risk of thermonuclear destruction during the Cold War was about ten thousand times higher than the mean death rate from asteroid impact. And indeed, there were other ‘near misses’ when catastrophe was only avoided by a thread. In 1983 Stanislav Petrov, a Russian Air Force officer, was monitoring a screen when an ‘alert’ indicated that five Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles had been launched by the United States towards the Soviet Union. Petrov’s instructions, when this happened, were to alert his superior (who could, within minutes, trigger nuclear retaliation).

The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

by

Toby Ord

Published 24 Mar 2020

When Soviet Premier Brezhnev found out, he asked President Carter “What kind of mechanism is it which allows a possibility of such incidents?”27 Autumn Equinox Incident: September 26, 1983 Shortly after midnight, in a period of heightened tensions, the screens at the command bunker for the Soviet satellite-based early-warning system showed five ICBMs launching from the United States.28 The duty officer, Stanislav Petrov, had instructions to report any detected launch to his superiors, who had a policy of immediate nuclear retaliatory strike. For five tense minutes he considered the case, then despite his remaining uncertainty, reported it to his commanders as a false alarm. He reasoned that a US first strike with just the five missiles shown was too unlikely and noted that the missiles’ vapor trails could not be identified.

…

-E. (2003). “Modeling the Size of Wars: From Billiard Balls to Sandpiles.” The American Political Science Review, 97(1), 135–50. Challinor, A. J., et al. (2014). “A Meta-Analysis of Crop Yield under Climate Change and Adaptation.” Nature Climate Change, 4(4), 287–91. Chan, S. (September 18, 2017). “Stanislav Petrov, Soviet Officer Who Helped Avert Nuclear War, Is Dead at 77.” The New York Times. Chapman, C. R. (2004). “The Hazard of Near-Earth Asteroid Impacts on Earth.” Earth And Planetary Science Letters, 222(1), 1–15. Charney, J. G., et al. (1979). “Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment.”

On Power and Ideology

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 7 Jul 2015

In September 2013, the BBC reported that during this dangerous period, Russia’s early-warning systems detected an incoming missile strike from the United States, sending the highest-level alert. The protocol for the Soviet military was to retaliate with a nuclear attack of its own. The officer on duty, Stanislav Petrov, decided to disobey orders and not report the warnings to his superiors. Thanks to his dereliction of duty, we are alive to reflect on the black swan we prefer not to see. Other studies reveal a shocking array of close calls, even apart from the “most dangerous moment in history” during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make a Difference

by

William MacAskill

Published 27 Jul 2015

HM1146.M33 2015 171'.8—dc23 2015000705 While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. Version_1 To Toby Ord, Peter Singer, and Stanislav Petrov, without whom this book would not have been written CONTENTS PRAISE FOR DOING GOOD BETTER TITLE PAGE COPYRIGHT DEDICATION INTRODUCTION Worms and Water Pumps: How can you do the most good? ONE You Are the 1 Percent: Just how much can you achieve? PART ONE THE FIVE KEY QUESTIONS OF EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM TWO Hard Trade-offs: Question #1: How many people benefit, and by how much?

Scary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our World

by

Mo Gawdat

Published 29 Sep 2021

Soviet protocol necessitated that Russia respond decisively, launching its entire nuclear arsenal before any US missile detonations could disable their response capability. This catastrophic error could have launched a world war that would have dwarfed the damage caused by the Second World War had it not been for a duty officer, Lt Col. Stanislav Petrov, who intercepted the messages and flagged them as faulty. He reasoned that if the US was really attacking, they would launch more than five missiles.3 He said he had a funny feeling in his gut that led him to investigate further. Good catch, Stan. Will our AI machines, assuming their code is perfect, be subjected to similar external signals that can lead to errors in the future?

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation That Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe

by

William Poundstone

Published 3 Jun 2019

During the height of the Cuban missile crisis one Russian submarine remained submerged and out of radio contact with Moscow. The sub’s captain assumed that war had broken out and decided to launch nuclear torpedoes. To do so he needed the authorization of two ranking officers. One agreed. The other was Vasili Arkhipov. His veto prevented World War III. The other room commemorates Stanislav Petrov, who chose not to initiate a nuclear attack when his computer screen showed five US missiles approaching the Soviet Union in 1983. Petrov reasoned that the United States would not strike Russia with a mere five missiles; therefore it must be a computer glitch. It was. The Future of Humanity Institute is an expression of a global movement.

Robot Rules: Regulating Artificial Intelligence

by

Jacob Turner

Published 29 Oct 2018

These issues raise fundamental questions about humanity’s relationship with AI: Why do we harbour concerns about giving up control? Can we strike a balance between AI effectiveness and human oversight? Will fools rush in where AIs fear to tread? 4.2 Why Might We Need Laws of Limitation? In September 2017, Stanislav Petrov died alone and destitute in an unremarkable Moscow suburb. His inauspicious death belied the pivotal role he played one night in 1983 when he was the duty officer in a secret command centre tasked with detecting nuclear attacks on the USSR by America. Petrov’s computer screen showed five intercontinental ballistic missiles heading towards the USSR.

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by

Jackson Lears

But in 1985, Reagan began yielding to the diplomatic charms of Mikhail Gorbachev as well as the citizen diplomacy of the nuclear freeze movement and came within an ace of abolishing nuclear weapons outright. Gorbachev must have known what had happened on September 26, 1983, when a Soviet early warning system mistook the sun’s reflection off clouds for five incoming Minuteman missiles. Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov and his staff, under unimaginable pressure, correctly concluded that the system flashing “LAUNCH” had raised a false alarm; Petrov did not report the incoming missiles to his superior officers, who would have immediately ordered a full-scale nuclear attack on the United States. This was the sort of incident (and there have been more on both sides) that would have inspired a thoughtful leader like Gorbachev to urge the abolition of nuclear weapons.

The Cold War

by

Robert Cowley

Published 5 May 1992

There Goes Brussels … WILLIAMSON MURRAY Let us play a counterfactual game, and suppose for a moment that the one-sided crisis of 1983 had gotten out of control. What if, for example, on the night of September 26, a Soviet officer in a bunker outside Moscow had not had doubts about what he was seeing on a computer screen—first one incoming missile, and then another, five in all. Had Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov followed regulations, he would have telephoned his superiors to warn them that the Soviet Union was only minutes away from a nuclear attack. Petrov hesitated, convinced that something had gone awry in the computer system. The minutes passed. Nothing did happen. That night one man's hunch may have averted World War III.

Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies

by

Nick Bostrom

Published 3 Jun 2014

The USA made emergency retaliation preparations before data from early-warning radar systems showed that no attack had been launched (McLean and Stewart 1979). On September 26, 1983, the malfunctioning Soviet Oko nuclear early-warning system reported an incoming US missile strike. The report was correctly identified as a false alarm by the duty officer at the command center, Stanislav Petrov: a decision that has been credited with preventing thermonuclear war (Lebedev 2004). It appears that a war would probably have fallen short of causing human extinction, even if it had been fought with the combined arsenals held by all the nuclear powers at the height of the Cold War, though it would have ruined civilization and caused unimaginable death and suffering (Gaddis 1982; Parrington 1997).

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 25 Jun 2024

See also Kyle Mizokami, “335 Million Dead: If America Launched an All-Out Nuclear War,” National Interest, March 13, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/335-million-dead-if-america-launched-all-out-nuclear-war-57262; Dylan Matthews, “40 Years Ago Today, One Man Saved Us from World-Ending Nuclear War,” Vox, September 26, 2023, https://www.vox.com/2018/9/26/17905796/nuclear-war-1983-stanislav-petrov-soviet-union; Owen B. Toon et al., “Rapidly Expanding Nuclear Arsenals in Pakistan and India Portend Regional and Global Catastrophe,” Science Advances 5, no. 10 (October 2, 2019), https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/10/eaay5478. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 5 Seth Baum, “The Risk of Nuclear Winter,” Federation of American Scientists, May 29, 2015, https://fas.org/pir-pubs/risk-nuclear-winter; Bryan Walsh, “What Could a Nuclear War Do to the Climate—and Humanity?

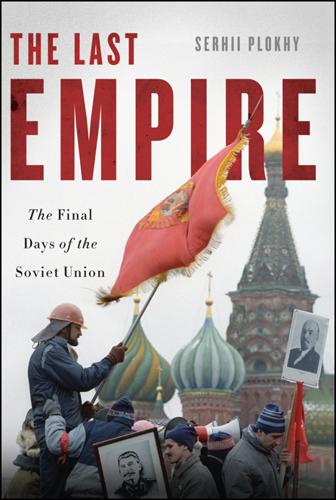

The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union

by

Serhii Plokhy

Published 12 May 2014

International tensions rose, threatening for the first time since the early 1960s to turn the Cold War into a hot one.3 On September 1, 1983, near Sakhalin Island, the Soviets shot down a South Korean airliner with 269 people aboard, including a sitting member of the US Congress. They then awaited American retaliation. Later that month, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov of the Soviet Air Defense Forces Command near Moscow saw a blip on his radar screen indicating a missile headed toward the USSR. Then he saw what appeared to be four more missiles headed in the same direction. Suspecting a computer malfunction, he did not report the image to his superiors. Had he done so, nuclear war between the two powers might well have become a reality.

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

by

J. Bradford Delong

Published 6 Apr 2020

In 1979, the loading of a training scenario onto an operational computer led NORAD to call the White House, claiming that the USSR had launched 250 missiles against the United States, and that the president had only between three and seven minutes to decide whether to retaliate. In 1983, the Soviet Union’s Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov refused to classify an early warning system missile sighting as an attack, dismissing it (correctly) as an error, and thereby preventing a worse error. That same year, the Soviet air force mistook an off-course Korean airliner carrying 100 people for one of the United States’ RC-135 spy planes that routinely violated Russian air space and shot it down.

Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion ofSafety

by

Eric Schlosser

Published 16 Sep 2013

President Reagan called the attack “an act of barbarism” and a “crime against humanity [that] must never be forgotten.” A few weeks later alarms went off in an air defense bunker south of Moscow. A Soviet early-warning satellite had detected five Minuteman missiles approaching from the United States. The commanding officer on duty, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, tried to make sense of the warning. An American first strike would surely involve more than five missiles—but perhaps this was merely the first wave. The Soviet general staff was alerted, and it was Petrov’s job to advise them whether the missile attack was real. Any retaliation would have to be ordered soon.

Gorbachev: His Life and Times

by

William Taubman

Then, on the night of September 26, 1983, in a secret underground bunker outside Moscow, alarms indicated that American missiles were speeding toward Moscow. The duty officer had seven minutes to alert Andropov, who was on a dialysis machine in a suburban sanatorium. Fortunately, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov concluded that the alarm was false. Meanwhile, however, the Americans and British were preparing to conduct the “Able Archer 83” war game, in which NATO’s supreme commander would request permission to use nuclear weapons and receive it. When Able Archer began in early November, the chief of the Soviet General Staff took cover in his command bunker under Moscow and ordered a “heightened alert” for some land-based Soviet forces.

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach

by

Stuart Russell

and

Peter Norvig

Published 14 Jul 2019

Department of Defense (DOD) roadmap says: “For the foreseeable future, decisions over the use of force [by autonomous systems] and the choice of which individual targets to engage with lethal force will be retained under human control.” The primary reason for this policy is practical: autonomous systems are not reliable enough to be trusted with military decisions. The issue of reliability came to the fore on September 26, 1983, when Soviet missile officer Stanislav Petrov’s computer display flashed an alert of an incoming missile attack. According to protocol, Petrov should have initiated a nuclear counterattack, but he suspected the alert was a bug and treated it as such. He was correct, and World War III was (narrowly) averted. We don’t know what would have happened if there had been no human in the loop.