Stephen Hawking

by Leonard Mlodinow · 8 Sep 2020 · 209pp · 68,587 words

Your Unconscious Mind Rules Your Behavior War of the Worldviews (with Deepak Chopra) The Grand Design (with Stephen Hawking) The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives A Briefer History of Time (with Stephen Hawking) Feynman’s Rainbow: A Search for Beauty in Physics and in Life Euclid’s Window: The Story of

…

Penguin Random House LLC. Photograph on this page courtesy of Alexei Mlodinow Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Mlodinow, Leonard, [date] author. Title: Stephen Hawking : a memoir of friendship and physics / Leonard Mlodinow. Description: First edition. New York : Pantheon Books, 2020. Identifiers: LCCN 2019049362 (print). LCCN 2019049363 (ebook). ISBN 9781524748685

…

6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Epilogue A Note on Sources Acknowledgments A Note About the Author In memory of Stephen Hawking 1942–2018 Introduction I said my last goodbye to Stephen at Great St. Mary’s church, a five-hundred-year-old structure in the midst

…

complex had won some design awards, but the design element I’d have liked most would have been arrows on signs saying “This way to Stephen Hawking.” Stephen’s pavilion was adjacent to an older building called the Isaac Newton Institute. Newton’s name came up a lot when you knew Stephen

…

and Theoretical Physics, or DAMTP, as people affectionately referred to it, pronouncing the acronym as if the P were silent. DAMTP was world famous as Stephen Hawking’s university department. There were only three stories in Stephen’s building, and the stairwell wound around an elevator shaft. I went up some stairs

…

head up, trying to balance it. His glasses slid toward his cheek. Beep beep beep beep. An alarm started up. I’d been nabbed damaging Stephen Hawking. Just then Sandi returned, and behind her, Judith, responding to the alarm. Sandi set Stephen’s head right and adjusted his glasses. With the glasses

…

more widespread belief that the issue is not one of great importance. * * * In the repository at Cambridge, stamped with the date 1 FEB 1966, is Stephen Hawking’s Ph.D. dissertation: Properties of Expanding Universes. He was twenty-four then. The dissertation opens, “Some implications and consequences of the expanding universe are

…

more complicated for black holes with spin, but that is outside the scope of this discussion. 7 The 1970s were not a good decade for Stephen Hawking’s body. He’d matured as a physicist but his disability was also advancing. In the early 1970s he lost most control of his hands

…

a senior fellow spoke of him as if giving him even that spot in a shared office was doing him a favor. “As long as Stephen Hawking pulls his weight, he can stay at the university,” the man said, “but as soon as he ceases to do that, he will have to

…

in the middle. “I’m disappointed by your inactivity,” I said. Having said it, I felt disappointed in me. Who was I to talk to Stephen Hawking that way? He made a face. I tried to read his expression. What was he thinking? It wasn’t an angry face. It looked like

…

it. Back then the author’s name was not a draw. Despite that New York Times profile, few outside the physics world had heard of Stephen Hawking. The market for popular science books hadn’t yet taken off. Still, every few years there had been a success. In 1977 there had been

…

two 360s, then raced off for the hotel entrance. The grad student saw Guzzardi observing all this. “Peter Guzzardi?” he asked. Guzzardi nodded. “That is Stephen Hawking,” he said. Guzzardi and the student took off after Stephen. They had to run to keep up, though it wasn’t the kind of place

…

ear, but she was practically yelling. “It might have been nice to let me know,” she continued. “You never do, do you! Because you’re Stephen Hawking, and you don’t need to! Well, there’s not enough food!” With that I started to withdraw, but I could tell from Stephen’s

…

, that’s not the way the book and its author were described in the media. In the media, Stephen Hawking, the man who couldn’t move, was called Master of the Universe. Of Stephen Hawking the atheist, it was declared that Courageous Physicist Knows the Mind of God. The inflated headlines were merely the

…

Bantam would agree and hadn’t given the matter any further thought. He seemed to have appreciated, which I didn’t at the time, that Stephen Hawking was the man who’d made Bantam Bantam. But Al had been right, too. The Grand Design sold well enough that in the long run

…

. I sat back and joined Stephen in focusing on Diana’s music. I wish now that I’d asked her what it was. *1 See Stephen Hawking, “Cosmology from the Top Down,” The Davis Meeting on Cosmic Inflation, March 22–25, 2003. *2 Technically, in quantum field theory, the sum is over

…

before the answer came. When it did, what he said was “My children.” * * * I was staring at a computer screen when the news flash came: Stephen Hawking is dead. He died at his home on Wordsworth Grove on March 14, 2018. It had been more than four years since I had seen

…

Seiler, Kip Thorne, Neil Turok, and Radka Visnakova. I also drew background material from two biographies: Kitty Ferguson, Stephen Hawking: His Life and Work (London: Transworld, 2011), and Michael White and John Gribbin, Stephen Hawking: A Life in Science (New York: Pegasus, 2016). For some of the details of Stephen’s life in the

…

, 2000), and Kip Thorne, Black Holes and Time Warps (New York: Norton, 1994). Finally, I also gleaned a few details from David H. Abramson, “Saving Stephen Hawking,” Harvard Magazine (May 9, 2018); Judy Bachrach, “A Beautiful Mind, an Ugly Possibility,” Vanity Fair (June 2004); and Bernard Carr

…

, “Stephen Hawking: Recollections of a Singular Friend,” Paradigm Explorer (2018/1), 9–13. Generally, I used these references only as background or for looking up facts or

…

, Beth Rashbaum, Fred Rose, Julie Sayres, Peggy Boulos Smith, Martin J. Smith, Andrew Weber, and Mariana Zahar. Most of all, I owe a debt to Stephen Hawking for choosing to work with me, and for the warmth and friendship we shared over the years we knew each other. His passing has left

…

), The Drunkard’s Walk (a New York Times Notable Book), War of the Worldviews (with Deepak Chopra), The Grand Design (with Stephen Hawking), and A Briefer History of Time (with Stephen Hawking), as well as Elastic, The Upright Thinkers, Feynman’s Rainbow, and Euclid’s Window. He has also written for the television series

A Brief History of Time

by Stephen Hawking · 16 Aug 2011 · 186pp · 64,267 words

ALSO BY STEPHEN HAWKING A Briefer History of Time Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays The Illustrated A Brief History of Time The Universe in a Nutshell

…

Bantam illustrated hardcover edition published November 1996 Bantam hardcover edition/September 1998 Bantam trade paperback edition/September 1998 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1988, 1996 by Stephen Hawking Illustrations copyright © 1988 by Ron Miller BOOK DESIGN BY GLEN M. EDELSTEIN No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

…

from the publisher. For information address: Bantam Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hawking, S. W. (Stephen W.) A brief history of time / Stephen Hawking. p. cm. Includes index. eISBN: 978-0-553-89692-3 1. Cosmology. I. Title. QB981.H377 1998 523.1—dc21 98-21874 Bantam Books are

…

few years we should know whether we can believe that we live in a universe that is completely self-contained and without beginning or end. Stephen Hawking CHAPTER 1 OUR PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He

…

, my nurses, colleagues, friends, and family have enabled me to live a very full life and to pursue my research despite my disability. Stephen Hawking ABOUT THE AUTHOR STEPHEN HAWKING was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge for thirty years, and has been the recipient of numerous awards and honors

The Grand Design

by Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow · 14 Jun 2010 · 124pp · 40,697 words

ALSO BY STEPHEN HAWKING A Brief History of Time A Briefer History of Time Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays The Illustrated A Brief History of Time

…

support, but practical and technical support without which we could not have written this book. Moreover, they always knew where to find the best pubs. STEPHEN HAWKING was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge for thirty years, and has been the recipient of numerous awards and honors including

God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History

by Stephen Hawking · 28 Mar 2007

GOD CREATED THE INTEGERS GOD CREATED THE INTEGERS THE MATHEMATICAL BREAKTHROUGHS THAT CHANGED HISTORY EDITED, WITH COMMENTARY, BY STEPHEN HAWKING RUNNING PRESS PHILADELPHIA • LONDON © 2007 by Stephen Hawking All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form

Pandora's Brain

by Calum Chace · 4 Feb 2014 · 345pp · 104,404 words

only scientists, industrialists and generals — should ask ourselves what can we do now to improve the chances of reaping the benefits and avoiding the risks.’ Stephen Hawking, April 2014 SELECTED REVIEWS FOR PANDORA’S BRAIN ‘I love the concepts in this book!’ Peter James, author of the best-selling Roy Grace series

From eternity to here: the quest for the ultimate theory of time

by Sean M. Carroll · 15 Jan 2010 · 634pp · 185,116 words

, 177, 213, 270, 379, and 382 by Sean Carroll. Photograph on page 204 courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Photograph on page 259 courtesy of Professor Stephen Hawking. Photograph on page 267 courtesy of Professor Jacob Bekenstein. Photograph on page 295 by Jerry Bauer, from Wikimedia Commons. Photograph on page 315 courtesy of

…

stars will have been used up. At that point, the black hole itself begins to evaporate into elementary particles. That’s the remarkable discovery of Stephen Hawking from 1976, which we’ll discuss in detail in Chapter Twelve: “black holes ain’t so black.” Due once again to quantum fluctuations, a black

…

could form in the real world, but the standard scenario is the collapse of a sufficiently massive star. In the late 1960s, Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking proved a remarkable feature of general relativity: If the gravitational field becomes sufficiently strong, a singularity must be formed.74 You might think that’s

…

destroy our would-be time machine. Nature, it seems, tries very hard to stop us from building a time machine. The accumulated circumstantial evidence prompted Stephen Hawking to propose what he calls the “Chronology Protection Conjecture”: The laws of physics (whatever they may be) prohibit the creation of closed timelike curves.101

…

HOLES: THE ENDS OF TIME Time, old gal of mine, will soon dim out. —Anne Sexton, “For Mr. Death Who Stands with His Door Open” Stephen Hawking is one of the most willful people on Earth. In 1963, while working toward his doctorate at Cambridge University at the age of twenty-one

…

visit on his annual sojourn. The institute administrator gave me a simple task: “Pick up Stephen at the airport.” As you might guess, picking up Stephen Hawking at the airport is different than picking up anyone else. For one thing, you’re not really “picking him up”; he rents a van that

…

Hawking explained that we had passed the restaurant and would have to turn around. Figure 58: Stephen Hawking, who gave us the most important clue we have about the relationship between quantum mechanics, gravity, and entropy. Stephen Hawking has been able to accomplish remarkable things while working under extraordinary handicaps, and the reason is

…

’ve used up all the extractable energy, and the hole just sits there. Those words should sound vaguely familiar from our previous discussions of thermodynamics. Stephen Hawking followed up on Penrose’s work to show that, while it’s possible to decrease the mass/energy of a spinning black hole, there is

…

. HAWKING RADIATION Along with Wheeler’s group at Princeton, the best work in general relativity in the early 1970s was being done in Great Britain. Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose, in particular, were inventing and applying new mathematical techniques to the study of curved spacetime. Out of these investigations came the celebrated

…

has been whittled down to a very small size, the end comes quickly in a dramatic explosion. Unfortunately, the numbers make it very hard for Stephen Hawking to win the Nobel Prize for predicting black hole radiation. For the kinds of black holes we know about, the radiation is far too feeble

…

community, with different people coming down on different sides of the debate. Very roughly speaking, physicists who come from a background in general relativity (including Stephen Hawking) have tended to believe that information really is lost, and that black hole evaporation represents a breakdown of the conventional rules of quantum mechanics; meanwhile

…

. In 1997, Hawking and fellow general-relativist Kip Thorne made a bet with John Preskill, a particle theorist from Caltech. It read as follows: Whereas Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne firmly believe that information swallowed by a black hole is forever hidden from the outside universe, and can never be revealed even

…

Dutch Nobel laureate Gerard ’t Hooft and American string theorist Leonard Susskind, and later formalized by German-American physicist Raphael Bousso (formerly a student of Stephen Hawking).227 Superficially, the holographic principle might sound a bit dry. Okay, the number of possible states in a region is proportional to the size of

…

describe spacetimes with different numbers of dimensions! Neither theory is “the right one”; they are completely equivalent to each other. Maldacena’s discovery helped persuade Stephen Hawking to concede his bet with Preskill and Thorne (although Hawking, as is his wont, worked things out his own way before becoming convinced). Remember that

…

principle of information conservation. Clearly, something has to give. The situation is reminiscent of the puzzle of information loss in black holes. There, we (or Stephen Hawking, more accurately) used quantum field theory in curved spacetime to derive a result—the evaporation of black holes into Hawking radiation—that seemed to destroy

…

T = (ħ/2πk)H, where ħ is Planck’s constant and k is Boltzmann’s constant. This was first worked out by Gary Gibbons and Stephen Hawking (1977). 252 You might think this prediction is a bit too bold, relying on uncertain extrapolations into regimes of physics that we don’t really

…

attention to. 275 A related strategy is to posit a particular form for the wave function of the universe, as advocated by James Hartle and Stephen Hawking (1983). They rely on a technique known as “Euclidean quantum gravity”; attempting to do justice to the pros and cons of this approach would take

…

more realistic version of the Weyl curvature hypothesis would have to be phrased in quantum-gravity language. 278 Gold (1962). 279 For a brief while, Stephen Hawking believed that his approach to quantum cosmology predicted that the arrow of time would actually reverse if the universe re-collapsed (Hawking, 1985). Don Page

…

. The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design. New York: Little, Brown, 2006. Susskind, L. The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics. New York: Little, Brown, 2008. Susskind, L., and Lindesay, J. An Introduction to Black Holes, Information, and

Einstein's Fridge: How the Difference Between Hot and Cold Explains the Universe

by Paul Sen · 16 Mar 2021 · 444pp · 111,837 words

(Lord Kelvin), James Joule, Hermann von Helmholtz, Rudolf Clausius, James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, Albert Einstein, Emmy Noether, Claude Shannon, Alan Turing, Jacob Bekenstein, and Stephen Hawking are among the smartest humans who ever lived. To tell their story is a way for all of us to comprehend and appreciate one of

…

of thermodynamics. The story of how this was discovered begins with one of the few people in history who exceeds the hype that surrounds him, Stephen Hawking. * * * In the summer of 1962, a healthy young student sat before a board of examiners at Oxford University. Twenty years old

…

, Stephen Hawking was about to receive his undergraduate degree. As his physics tutor at the time said of the examiners, “They were intelligent enough to realize they

…

if thermodynamics could somehow survive the battle with general relativity. To do so he had to assume, flying in the face of the beliefs of Stephen Hawking and others, that a black hole could have entropy. Colleagues have commented how Bekenstein’s quiet and gentle demeanor stood in stark contrast to his

…

general theory of relativity, increasing the mass of a black hole always increased the area of its event horizon. This was also in line with Stephen Hawking’s recent paper showing that event horizons can never become smaller. To summarize: Entropy increases the energy content of the black hole, increasing both its

…

who heard about it said it was patent nonsense. Some told me that I was wasting my time.” Reading Bekenstein’s paper did not make Stephen Hawking happy, either. Having spent several years studying general relativity, Hawking felt strongly that it banned the possibility of black holes giving off heat. Together with

…

fevered imaginings, could he have foreseen that the ideas he seeded would one day help us to understand the very edge of our cosmos. As Stephen Hawking wrote, “We are just an advanced breed of monkeys on a minor planet of a very average star. But we can understand the Universe. That

…

Goes Back to Alan Turing,” October 2017. Chapter Nineteen: Event Horizon Bekenstein and Hawking were the first: From The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safer for Quantum Mechanics by Leonard Susskind. Your idea is so crazy: Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam: A Life in

…

. a black hole cannot radiate heat and therefore cannot have entropy: See A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes by Stephen Hawking. Jacob Bekenstein and his supervisor, John Wheeler: For details of this meeting and more biographical information on both, see Of Gravity, Black Holes and Information

…

Alan Turing: The Enigma Man by Nigel Cawthorne Alan Turing: The Life of a Genius by Dermot Turing The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safer for Quantum Mechanics by Leonard Susskind Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy by Kip S. Thorne A

…

Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes by Stephen Hawking The Bumpy Road: Max Planck from Radiation Theory to the Quantum, 1896–1906 by Massimiliano Badino Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson Einstein

…

World by Ian Stewart Significant Figures: Lives and Works of Trailblazing Mathematicians by Ian Stewart Sketch of Thermodynamics by Peter Guthrie Tate Stephen Hawking: His Life and Work by Kitty Ferguson Stephen Hawking’s Universe: An Introduction to the Most Remarkable Scientist of Our Time by John Boslough A Student’s Guide to Einstein

The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything

by Michio Kaku · 5 Apr 2021 · 157pp · 47,161 words

write an equation whose mathematical elegance would encompass the whole of physics. Some of the most eminent physicists in the world embarked upon this quest. Stephen Hawking even gave a talk with the auspicious title “Is the End in Sight for Theoretical Physics?” If such a theory is successful, it would be

…

the limits of our imagination. As it turns out, our guide through this uncharted territory was totally paralyzed. As a graduate student at Cambridge University, Stephen Hawking was an ordinary youth, without much direction or purpose. He went through the motions of being a physicist, but his heart was not there. It

…

was done, the Flatlanders were amazed and astonished at the dazzling, shimmering jewel that suddenly emerged before them, with its perfect, glorious symmetry. Or, as Stephen Hawking wrote, If we do discover a complete theory, it should in time be understandable in broad principle by everyone, not just a few scientists. Then

…

://backreaction.blogspot.com/2018/10/you-say-theoretical-physicists-are.html. Chapter 7: Finding Meaning in the Universe “If we do discover a complete theory”: Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time (New York: Bantam Books, 1988), 175. SELECTED READING Bartusiak, Marcia. Einstein’s Unfinished Symphony. Yale University Press, 2017. Becker, Katrin

…

, Feynman, Schrodinger, Heisenberg, and Einstein. Independently published, 2020. Misner, Charles W., Kip Thorne, and John A. Wheeler. Gravitation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2017. Mlodinow, Leonard. Stephen Hawking: A Memoir of Friendship and Physics. New York: Pantheon Books, 2020. Polchinski, Joseph. String Theory, vols. 1 and 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Smolin

The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets

by Simon Singh · 29 Oct 2013 · 262pp · 65,959 words

elite. Indeed, as the episode reaches its finale, the revolting masses focus their anger on Lisa, who is only saved when none other than Professor Stephen Hawking arrives in the nick of time to rescue her. Although we associate Hawking with cosmology, he spent thirty years as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

…

also encouraged Homer’s intellectual side to flourish in “They Saved Lisa’s Brain,” an episode that has already been discussed in Chapter 7. After Stephen Hawking saves Lisa from a baying mob, the story ends with Professor Hawking chatting to Lisa’s father in Moe’s Tavern, where he is impressed

…

picked Cygnus X-1 because it is considered a glamorous black hole, thanks to being the subject of a famous wager. The mathematician and cosmologist Stephen Hawking had initially doubted that the object in question was indeed a black hole, so he placed a bet with his colleague Kip Thorne. When careful

The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology

by Ray Kurzweil · 14 Jul 2005 · 761pp · 231,902 words

represent only the early-adoption phase. As the technologies become established, there will be no barriers to using them for vast expansion of human potential. Stephen Hawking recently commented in the German magazine Focus that computer intelligence will surpass that of humans within a few decades. He advocated that we "urgently need

…

been a long-standing debate about whether or not we can transmit information into a black hole, have it usefully transformed, and then retrieve it. Stephen Hawking's conception of transmissions from a black hole involves particle-antiparticle pairs that are created near the event horizon (the point of no return near

…

is pulled into the black hole while the other manages to escape. These escaping particles form a glow called Hawking radiation, named after its discoverer, Stephen Hawking. The current thinking is that this radiation does reflect (in a coded fashion, and as a result of a form of quantum entanglement with the

…

," New Scientist, June 30, 2004, http://www.newscientist.comlnews/news.jsp?id=ns99996092. See also http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/05/050512120842.htm. 16. Stephen Hawking declared at a scientific conference in Dublin on July 21, 2004, that he had been wrong in a controversial assertion he made thirty years ago

…

Kimberly Weaver, "The Galactic Odd Couple," http://www.scientificamerican.com. June 10, 2003; Jean-Pierre Lasota, "Unmasking Black Holes," Scientific American (May 1999): 41–47; Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes (New York: Bantam, 1988). 18. Joel Smoller and Blake Temple, "Shock-Wave Cosmology

…

news release, see "An Early Step Toward Helping the Paralyzed Walk," October 24, 2001, http://www.utah.edu/news/releases/01/oct/spinal.html. 25. Stephen Hawking's remarks, which were mistranslated by Focus, were quoted in Nick Paton Walsh, "Alter Our DNA or Robots Will Take Over, Warns Hawking," Observer, September

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach

by Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig · 14 Jul 2019 · 2,466pp · 668,761 words

Coming of Age in the Milky Way

by Timothy Ferris · 30 Jun 1988 · 661pp · 169,298 words

Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray

by Sabine Hossenfelder · 11 Jun 2018 · 340pp · 91,416 words

Massive: The Missing Particle That Sparked the Greatest Hunt in Science

by Ian Sample · 1 Jan 2010 · 310pp · 89,838 words

How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Renegades, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight

by Julian Guthrie · 19 Sep 2016

The World According to Physics

by Jim Al-Khalili · 10 Mar 2020 · 198pp · 57,703 words

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by Nicole Kobie · 3 Jul 2024 · 348pp · 119,358 words

Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 27 Feb 2012 · 476pp · 118,381 words

The Fabric of the Cosmos

by Brian Greene · 1 Jan 2003 · 695pp · 219,110 words

What We Cannot Know: Explorations at the Edge of Knowledge

by Marcus Du Sautoy · 18 May 2016

Ten Billion Tomorrows: How Science Fiction Technology Became Reality and Shapes the Future

by Brian Clegg · 8 Dec 2015 · 315pp · 92,151 words

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by Annie Jacobsen · 14 Sep 2015 · 558pp · 164,627 words

The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever

by Christopher Hitchens · 14 Jun 2007 · 740pp · 236,681 words

Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century

by P. W. Singer · 1 Jan 2010 · 797pp · 227,399 words

Collider

by Paul Halpern · 3 Aug 2009 · 279pp · 75,527 words

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

by Jay Barbree · 18 Aug 2008 · 386pp · 92,778 words

Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence

by Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb · 16 Apr 2018 · 345pp · 75,660 words

The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of Humanity

by Byron Reese · 23 Apr 2018 · 294pp · 96,661 words

Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War

by Paul Scharre · 23 Apr 2018 · 590pp · 152,595 words

Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut

by Nicholas Schmidle · 3 May 2021 · 342pp · 101,370 words

Free-Range Chickens

by Simon Rich · 1 Jan 2008 · 86pp · 14,764 words

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by Chris Impey · 12 Apr 2015 · 370pp · 97,138 words

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

by James Gleick · 1 Mar 2011 · 855pp · 178,507 words

The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos

by Christian Davenport · 20 Mar 2018 · 390pp · 108,171 words

The Scientist as Rebel

by Freeman Dyson · 1 Jan 2006 · 332pp · 109,213 words

Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind

by Susan Schneider · 1 Oct 2019 · 331pp · 47,993 words

Infinity in the Palm of Your Hand: Fifty Wonders That Reveal an Extraordinary Universe

by Marcus Chown · 22 Apr 2019 · 171pp · 51,276 words

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by Michael Shermer · 8 Apr 2020 · 677pp · 121,255 words

The Ape That Understood the Universe: How the Mind and Culture Evolve

by Steve Stewart-Williams · 12 Sep 2018 · 1,132pp · 156,379 words

The Second Intelligent Species: How Humans Will Become as Irrelevant as Cockroaches

by Marshall Brain · 6 Apr 2015 · 215pp · 56,215 words

Warnings

by Richard A. Clarke · 10 Apr 2017 · 428pp · 121,717 words

Filthy Rich: A Powerful Billionaire, the Sex Scandal That Undid Him, and All the Justice That Money Can Buy: The Shocking True Story of Jeffrey Epstein

by James Patterson, John Connolly and Tim Malloy · 10 Oct 2016 · 234pp · 63,844 words

Possible Minds: Twenty-Five Ways of Looking at AI

by John Brockman · 19 Feb 2019 · 339pp · 94,769 words

The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

by David Deutsch · 30 Jun 2011 · 551pp · 174,280 words

I, Warbot: The Dawn of Artificially Intelligent Conflict

by Kenneth Payne · 16 Jun 2021 · 339pp · 92,785 words

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation That Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe

by William Poundstone · 3 Jun 2019 · 283pp · 81,376 words

The Rationalist's Guide to the Galaxy: Superintelligent AI and the Geeks Who Are Trying to Save Humanity's Future

by Tom Chivers · 12 Jun 2019 · 289pp · 92,714 words

The Infinite Book: A Short Guide to the Boundless, Timeless and Endless

by John D. Barrow · 1 Aug 2005 · 292pp · 88,319 words

The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science

by Michael Strevens · 12 Oct 2020

Explaining Humans: What Science Can Teach Us About Life, Love and Relationships

by Camilla Pang · 12 Mar 2020 · 256pp · 67,563 words

Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies

by Geoffrey West · 15 May 2017 · 578pp · 168,350 words

Time Travel: A History

by James Gleick · 26 Sep 2016 · 257pp · 80,100 words

The Burning Answer: The Solar Revolution: A Quest for Sustainable Power

by Keith Barnham · 7 May 2015 · 433pp · 124,454 words

Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science

by Michael Nielsen · 2 Oct 2011 · 400pp · 94,847 words

Everything Is Predictable: How Bayesian Statistics Explain Our World

by Tom Chivers · 6 May 2024 · 283pp · 102,484 words

A Short History of Nearly Everything

by Bill Bryson · 5 May 2003 · 654pp · 204,260 words

Singularity Rising: Surviving and Thriving in a Smarter, Richer, and More Dangerous World

by James D. Miller · 14 Jun 2012 · 377pp · 97,144 words

In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? The History and Future of Artificial Intelligence

by George Zarkadakis · 7 Mar 2016 · 405pp · 117,219 words

This Is Not Fame: A "From What I Re-Memoir"

by Doug Stanhope · 5 Dec 2017 · 323pp · 100,923 words

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

by Charles Seife · 31 Aug 2000 · 233pp · 62,563 words

To Be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death

by Mark O'Connell · 28 Feb 2017 · 252pp · 79,452 words

Neutrino Hunters: The Thrilling Chase for a Ghostly Particle to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe

by Ray Jayawardhana · 10 Dec 2013 · 203pp · 63,257 words

Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future

by Martin Ford · 4 May 2015 · 484pp · 104,873 words

The Clock Mirage: Our Myth of Measured Time

by Joseph Mazur · 20 Apr 2020 · 283pp · 85,906 words

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by Scott E. Page · 27 Nov 2018 · 543pp · 153,550 words

Editing Humanity: The CRISPR Revolution and the New Era of Genome Editing

by Kevin Davies · 5 Oct 2020 · 741pp · 164,057 words

Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence

by James Lovelock · 27 Aug 2019 · 94pp · 33,179 words

The Future Is Faster Than You Think: How Converging Technologies Are Transforming Business, Industries, and Our Lives

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 28 Jan 2020 · 501pp · 114,888 words

When Einstein Walked With Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

by Jim Holt · 14 May 2018 · 436pp · 127,642 words

The Panic Virus: The True Story Behind the Vaccine-Autism Controversy

by Seth Mnookin · 3 Jan 2012 · 566pp · 153,259 words

The Clockwork Universe: Saac Newto, Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern WorldI

by Edward Dolnick · 8 Feb 2011 · 439pp · 104,154 words

Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

by James Gleick · 1 Jan 1992 · 795pp · 215,529 words

There Is No Planet B: A Handbook for the Make or Break Years

by Mike Berners-Lee · 27 Feb 2019

The Simulation Hypothesis

by Rizwan Virk · 31 Mar 2019 · 315pp · 89,861 words

The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet

by Arthur Turrell · 2 Aug 2021 · 297pp · 84,447 words

Hope Dies Last: Visionary People Across the World, Fighting to Find Us a Future

by Alan Weisman · 21 Apr 2025 · 599pp · 149,014 words

The Pirate's Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism

by Matt Mason

Rule of the Robots: How Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Everything

by Martin Ford · 13 Sep 2021 · 288pp · 86,995 words

We Are the Nerds: The Birth and Tumultuous Life of Reddit, the Internet's Culture Laboratory

by Christine Lagorio-Chafkin · 1 Oct 2018

Track Changes

by Matthew G. Kirschenbaum · 1 May 2016 · 519pp · 142,646 words

Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies

by Nick Bostrom · 3 Jun 2014 · 574pp · 164,509 words

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

by Naomi Klein · 15 Sep 2014 · 829pp · 229,566 words

The Driver in the Driverless Car: How Our Technology Choices Will Create the Future

by Vivek Wadhwa and Alex Salkever · 2 Apr 2017 · 181pp · 52,147 words

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by Nicholas Carr · 28 Sep 2014 · 308pp · 84,713 words

Surviving AI: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence

by Calum Chace · 28 Jul 2015 · 144pp · 43,356 words

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It

by Marc Goodman · 24 Feb 2015 · 677pp · 206,548 words

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 3 Feb 2015 · 368pp · 96,825 words

The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom

by Graham Farmelo · 24 Aug 2009 · 1,396pp · 245,647 words

Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in This Life and Beyond

by Tamara Kneese · 14 Aug 2023 · 284pp · 75,744 words

Augmented: Life in the Smart Lane

by Brett King · 5 May 2016 · 385pp · 111,113 words

Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time

by Michael Shermer · 1 Jan 1997 · 404pp · 134,430 words

Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don't Have To

by David A. Sinclair and Matthew D. Laplante · 9 Sep 2019

The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution

by Charles R. Morris · 1 Jan 2012 · 456pp · 123,534 words

Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences

by Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star · 25 Aug 2000 · 357pp · 125,142 words

Microserfs

by Douglas Coupland · 14 Feb 1995

Ant Farm and Other Desperate Situations

by Simon Rich · 10 Nov 2005 · 76pp · 16,007 words

The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission

by Jim Bell · 24 Feb 2015 · 310pp · 89,653 words

The Road to Conscious Machines

by Michael Wooldridge · 2 Nov 2018 · 346pp · 97,890 words

Radicals Chasing Utopia: Inside the Rogue Movements Trying to Change the World

by Jamie Bartlett · 12 Jun 2017 · 390pp · 109,870 words

The God Delusion

by Richard Dawkins · 12 Sep 2006 · 478pp · 142,608 words

Exoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial Life

by Donald Goldsmith · 9 Sep 2018 · 265pp · 76,875 words

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

by James Barrat · 30 Sep 2013 · 294pp · 81,292 words

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration

by Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees · 18 Apr 2022 · 192pp · 63,813 words

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by Douglas Rushkoff · 7 Sep 2022 · 205pp · 61,903 words

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by Carl Benedikt Frey · 17 Jun 2019 · 626pp · 167,836 words

Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration―and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives

by Danny Dorling and Kirsten McClure · 18 May 2020 · 459pp · 138,689 words

Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology

by Adrienne Mayor · 27 Nov 2018

Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another

by Matt Taibbi · 7 Oct 2019 · 357pp · 99,456 words

Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's Computers

by John MacCormick and Chris Bishop · 27 Dec 2011 · 250pp · 73,574 words

Big Bang

by Simon Singh · 1 Jan 2004 · 492pp · 149,259 words

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?

by Bill McKibben · 15 Apr 2019

The Human Cosmos: A Secret History of the Stars

by Jo Marchant · 15 Jan 2020 · 544pp · 134,483 words

Thinking Machines: The Inside Story of Artificial Intelligence and Our Race to Build the Future

by Luke Dormehl · 10 Aug 2016 · 252pp · 74,167 words

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by Keach Hagey · 19 May 2025 · 439pp · 125,379 words

All That Glitters: A Story of Friendship, Fraud, and Fine Art

by Orlando Whitfield · 5 Aug 2024 · 306pp · 104,072 words

Rage Inside the Machine: The Prejudice of Algorithms, and How to Stop the Internet Making Bigots of Us All

by Robert Elliott Smith · 26 Jun 2019 · 370pp · 107,983 words

The Mission: A True Story

by David W. Brown · 26 Jan 2021

When Computers Can Think: The Artificial Intelligence Singularity

by Anthony Berglas, William Black, Samantha Thalind, Max Scratchmann and Michelle Estes · 28 Feb 2015

The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World

by Pedro Domingos · 21 Sep 2015 · 396pp · 117,149 words

Architects of Intelligence

by Martin Ford · 16 Nov 2018 · 586pp · 186,548 words

England

by David Else · 14 Oct 2010

The Most Human Human: What Talking With Computers Teaches Us About What It Means to Be Alive

by Brian Christian · 1 Mar 2011 · 370pp · 94,968 words

You Can't Make This Stuff Up: The Complete Guide to Writing Creative Nonfiction--From Memoir to Literary Journalism and Everything in Between

by Lee Gutkind · 13 Aug 2012 · 347pp · 90,234 words

Countdown: Our Last, Best Hope for a Future on Earth?

by Alan Weisman · 23 Sep 2013 · 579pp · 164,339 words

A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s

by Alwyn W. Turner · 4 Sep 2013 · 1,013pp · 302,015 words

Tyler Cowen-Discover Your Inner Economist Use Incentives to Fall in Love, Survive Your Next Meeting, and Motivate Your Dentist-Plume (2008)

by Unknown · 20 Sep 2008 · 246pp · 116 words

The Norm Chronicles

by Michael Blastland · 14 Oct 2013

The 4-Hour Chef: The Simple Path to Cooking Like a Pro, Learning Anything, and Living the Good Life

by Timothy Ferriss · 1 Jan 2012 · 1,007pp · 181,911 words

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by Anthony M. Townsend · 15 Jun 2020 · 362pp · 97,288 words

Space 2.0

by Rod Pyle · 2 Jan 2019 · 352pp · 87,930 words

Frommer's London 2009

by Darwin Porter and Danforth Prince · 25 Aug 2008

4th Rock From the Sun: The Story of Mars

by Nicky Jenner · 5 Apr 2017 · 294pp · 87,986 words

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna · 23 May 2016 · 437pp · 113,173 words

The Fabric of Reality

by David Deutsch · 31 Mar 2012 · 511pp · 139,108 words

Lurking: How a Person Became a User

by Joanne McNeil · 25 Feb 2020 · 239pp · 80,319 words

March of the Lemmings: Brexit in Print and Performance 2016–2019

by Stewart Lee · 2 Sep 2019 · 382pp · 117,536 words

Chaos: Making a New Science

by James Gleick · 18 Oct 2011 · 396pp · 112,748 words

The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare in the Robot Age

by Roger Bootle · 4 Sep 2019 · 374pp · 111,284 words

100 Plus: How the Coming Age of Longevity Will Change Everything, From Careers and Relationships to Family And

by Sonia Arrison · 22 Aug 2011 · 381pp · 78,467 words

Frommer's England 2011: With Wales

by Darwin Porter and Danforth Prince · 2 Jan 2010

Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (Inside Technology)

by Geoffrey C. Bowker · 24 Aug 2000

The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone

by Brian Merchant · 19 Jun 2017 · 416pp · 129,308 words

A Devil's Chaplain: Selected Writings

by Richard Dawkins · 1 Jan 2004 · 460pp · 107,712 words

Utopia Is Creepy: And Other Provocations

by Nicholas Carr · 5 Sep 2016 · 391pp · 105,382 words

Kill Your Friends

by John Niven · 7 Feb 2008 · 269pp · 78,468 words

The Fourth Industrial Revolution

by Klaus Schwab · 11 Jan 2016 · 179pp · 43,441 words

Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 10 Sep 2018 · 745pp · 207,187 words

Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley From Building a New Global Underclass

by Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri · 6 May 2019 · 346pp · 97,330 words

The Mysterious Mr. Nakamoto: A Fifteen-Year Quest to Unmask the Secret Genius Behind Crypto

by Benjamin Wallace · 18 Mar 2025 · 431pp · 116,274 words

How to Spend a Trillion Dollars

by Rowan Hooper · 15 Jan 2020 · 285pp · 86,858 words

Life After Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy

by George Gilder · 16 Jul 2018 · 332pp · 93,672 words

Great Britain

by David Else and Fionn Davenport · 2 Jan 2007

From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds

by Daniel C. Dennett · 7 Feb 2017 · 573pp · 157,767 words

Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 18 Dec 2006 · 313pp · 94,490 words

Utopias: A Brief History From Ancient Writings to Virtual Communities

by Howard P. Segal · 20 May 2012 · 299pp · 19,560 words

Artificial Whiteness

by Yarden Katz

Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming

by Mckenzie Funk · 22 Jan 2014 · 337pp · 101,281 words

Underestimated: An Autism Miracle

by J. B. Handley and Jamison Handley · 23 Mar 2021 · 130pp · 42,093 words

The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy

by Moiya McTier · 14 Aug 2022 · 194pp · 63,798 words

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith · 6 Nov 2023 · 490pp · 132,502 words

Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to Fake News and Filter-Bubbles – the Algorithms That Control Our Lives

by David Sumpter · 18 Jun 2018 · 276pp · 81,153 words

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by Ray Kurzweil · 25 Jun 2024

Elon Musk: A Mission to Save the World

by Anna Crowley Redding · 1 Jul 2019 · 190pp · 46,977 words

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

by Andrew Yang · 2 Apr 2018 · 300pp · 76,638 words

On Palestine

by Noam Chomsky, Ilan Pappé and Frank Barat · 18 Mar 2015

Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-Connected World

by Bruce Schneier · 3 Sep 2018 · 448pp · 117,325 words

When Things Start to Think

by Neil A. Gershenfeld · 15 Feb 1999 · 238pp · 46 words

Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions

by Temple Grandin, Ph.d. · 11 Oct 2022

The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work

by Richard Baldwin · 10 Jan 2019 · 301pp · 89,076 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Dreaming in Code: Two Dozen Programmers, Three Years, 4,732 Bugs, and One Quest for Transcendent Software

by Scott Rosenberg · 2 Jan 2006 · 394pp · 118,929 words

Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100

by Michio Kaku · 15 Mar 2011 · 523pp · 148,929 words

Rewired: The Post-Cyberpunk Anthology

by James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel · 30 Sep 2007 · 571pp · 162,958 words

The Music of the Primes

by Marcus Du Sautoy · 26 Apr 2004 · 434pp · 135,226 words

The Golden Ticket: P, NP, and the Search for the Impossible

by Lance Fortnow · 30 Mar 2013 · 236pp · 50,763 words

AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

by Kai-Fu Lee · 14 Sep 2018 · 307pp · 88,180 words

An Optimist's Tour of the Future

by Mark Stevenson · 4 Dec 2010 · 379pp · 108,129 words

Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome

by Nessa Carey · 5 Mar 2015 · 357pp · 98,853 words

12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next

by Jeanette Winterson · 15 Mar 2021 · 256pp · 73,068 words

Notes From an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back

by Mark O'Connell · 13 Apr 2020 · 213pp · 70,742 words

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker · 13 Feb 2018 · 1,034pp · 241,773 words

The Narcissist Next Door

by Jeffrey Kluger · 25 Aug 2014 · 295pp · 89,280 words

What Technology Wants

by Kevin Kelly · 14 Jul 2010 · 476pp · 132,042 words

Tomorrowland: Our Journey From Science Fiction to Science Fact

by Steven Kotler · 11 May 2015 · 294pp · 80,084 words

Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins

by Garry Kasparov · 1 May 2017 · 331pp · 104,366 words

Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes

by Mark Penn and E. Kinney Zalesne · 5 Sep 2007 · 458pp · 134,028 words

Richard Dawkins: How a Scientist Changed the Way We Think

by Alan Grafen; Mark Ridley · 1 Jan 2006 · 286pp · 90,530 words

Beyond Weird

by Philip Ball · 22 Mar 2018 · 277pp · 87,082 words

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

by David Christian · 21 May 2018 · 334pp · 100,201 words

The Search for Superstrings, Symmetry, and the Theory of Everything

by John Gribbin · 29 Nov 2009 · 185pp · 55,639 words

The Wealth Dragon Way: The Why, the When and the How to Become Infinitely Wealthy

by John Lee · 13 Apr 2015 · 202pp · 72,857 words

What to Think About Machines That Think: Today's Leading Thinkers on the Age of Machine Intelligence

by John Brockman · 5 Oct 2015 · 481pp · 125,946 words

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by Tim Fernholz · 20 Mar 2018 · 328pp · 96,141 words

It Doesn't Have to Be Crazy at Work

by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson · 1 Oct 2018 · 117pp · 30,538 words

Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control

by Stuart Russell · 7 Oct 2019 · 416pp · 112,268 words

The Gifted Adult: A Revolutionary Guide for Liberating Everyday Genius(tm)

by Mary-Elaine Jacobsen · 2 Nov 1999 · 435pp · 136,906 words

Robot Rules: Regulating Artificial Intelligence

by Jacob Turner · 29 Oct 2018 · 688pp · 147,571 words

The Gifted Adult: A Revolutionary Guide for Liberating Everyday Genius(tm)

by Mary-Elaine Jacobsen · 18 Feb 2015 · 435pp · 136,741 words

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by Thomas W. Malone · 14 May 2018 · 344pp · 104,077 words

What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets

by Michael Sandel · 26 Apr 2012 · 231pp · 70,274 words

Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans

by Melanie Mitchell · 14 Oct 2019 · 350pp · 98,077 words

This Is for Everyone: The Captivating Memoir From the Inventor of the World Wide Web

by Tim Berners-Lee · 8 Sep 2025 · 347pp · 100,038 words

Showstopper!: The Breakneck Race to Create Windows NT and the Next Generation at Microsoft

by G. Pascal Zachary · 1 Apr 2014 · 384pp · 109,125 words

The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

by Toby Ord · 24 Mar 2020 · 513pp · 152,381 words

Brit-Myth: Who Do the British Think They Are?

by Chris Rojek · 15 Feb 2008 · 219pp · 61,334 words

Voyage for Madmen

by Peter Nichols · 1 May 2011

The New Gold Rush: The Riches of Space Beckon!

by Joseph N. Pelton · 5 Nov 2016 · 321pp · 89,109 words

Clock of the Long Now

by Stewart Brand · 1 Jan 1999 · 194pp · 49,310 words

The Age of Wonder

by Richard Holmes · 15 Jan 2008 · 778pp · 227,196 words

Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut

by Mike Mullane · 24 Jan 2006 · 506pp · 167,034 words

Raw Data Is an Oxymoron

by Lisa Gitelman · 25 Jan 2013

More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity

by Adam Becker · 14 Jun 2025 · 381pp · 119,533 words

Humankind: A Hopeful History

by Rutger Bregman · 1 Jun 2020 · 578pp · 131,346 words

Life's Greatest Secret: The Race to Crack the Genetic Code

by Matthew Cobb · 6 Jul 2015 · 608pp · 150,324 words

The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization

by Richard Baldwin · 14 Nov 2016 · 606pp · 87,358 words

The Weather Makers: How Man Is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth

by Tim Flannery · 10 Jan 2001 · 427pp · 111,965 words

A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas

by Warren Berger · 4 Mar 2014 · 374pp · 89,725 words

Crypto: How the Code Rebels Beat the Government Saving Privacy in the Digital Age

by Steven Levy · 15 Jan 2002 · 468pp · 137,055 words

Hit Refresh: The Quest to Rediscover Microsoft's Soul and Imagine a Better Future for Everyone

by Satya Nadella, Greg Shaw and Jill Tracie Nichols · 25 Sep 2017 · 391pp · 71,600 words

Uncharted: How to Map the Future

by Margaret Heffernan · 20 Feb 2020 · 335pp · 97,468 words

Empire of the Scalpel: The History of Surgery

by Ira Rutkow · 8 Mar 2022 · 509pp · 142,456 words

SuperBetter: The Power of Living Gamefully

by Jane McGonigal · 14 Sep 2015 · 525pp · 147,008 words

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by Jaron Lanier · 21 Nov 2017 · 480pp · 123,979 words

Trading Risk: Enhanced Profitability Through Risk Control

by Kenneth L. Grant · 1 Sep 2004

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

by Carl Sagan · 8 Sep 1997 · 356pp · 102,224 words

Hothouse Kids: The Dilemma of the Gifted Child

by Alissa Quart · 16 Aug 2006

Invisible Women

by Caroline Criado Perez · 12 Mar 2019 · 480pp · 119,407 words

The Cardinal of the Kremlin

by Tom Clancy · 2 Jan 1988

The Pot Book: A Complete Guide to Cannabis

by Julie Holland · 22 Sep 2010 · 694pp · 197,804 words

The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics

by Tim Harford · 2 Feb 2021 · 428pp · 103,544 words

Le Freak: An Upside Down Story of Family, Disco, and Destiny

by Nile Rodgers · 17 Oct 2011 · 296pp · 94,948 words

Total Recall: How the E-Memory Revolution Will Change Everything

by Gordon Bell and Jim Gemmell · 15 Feb 2009 · 291pp · 77,596 words

Immortality, Inc.

by Chip Walter · 7 Jan 2020 · 232pp · 72,483 words

The Science of Fear: How the Culture of Fear Manipulates Your Brain

by Daniel Gardner · 23 Jun 2009 · 542pp · 132,010 words

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel · 7 Sep 2020 · 209pp · 53,175 words

The Myth of Artificial Intelligence: Why Computers Can't Think the Way We Do

by Erik J. Larson · 5 Apr 2021

Me! Me! Me!

by Daniel Ruiz Tizon · 31 May 2016 · 218pp · 67,930 words

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by David Eagleman and Anthony Brandt · 30 Sep 2017 · 345pp · 84,847 words

Illustrated Theory of Everything: The Origin and Fate of the Universe

by Stephen Hawking · 1 Aug 2009 · 81pp · 28,120 words

Big Mistakes: The Best Investors and Their Worst Investments

by Michael Batnick · 21 May 2018 · 198pp · 53,264 words

The End of Work: Why Your Passion Can Become Your Job

by John Tamny · 6 May 2018 · 165pp · 47,193 words

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by Jeremy Lent · 22 May 2017 · 789pp · 207,744 words

50 Future Ideas You Really Need to Know

by Richard Watson · 5 Nov 2013 · 219pp · 63,495 words

Bill Bailey's Remarkable Guide to Happiness: THE FEELGOOD BOOK OF THE YEAR

by Bill Bailey · 14 Oct 2020 · 112pp · 34,520 words

Against Technoableism: Rethinking Who Needs Improvement

by Ashley Shew · 18 Sep 2023 · 154pp · 43,956 words

Smart Cities, Digital Nations

by Caspar Herzberg · 13 Apr 2017

A Pelican Introduction: Basic Income

by Guy Standing · 3 May 2017 · 307pp · 82,680 words

The Deep Learning Revolution (The MIT Press)

by Terrence J. Sejnowski · 27 Sep 2018

The Best of Best New SF

by Gardner R. Dozois · 1 Jan 2005 · 1,280pp · 384,105 words

Underground

by Suelette Dreyfus · 1 Jan 2011 · 547pp · 160,071 words

AI 2041: Ten Visions for Our Future

by Kai-Fu Lee and Qiufan Chen · 13 Sep 2021

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by John Markoff · 24 Aug 2015 · 413pp · 119,587 words

The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism

by Calum Chace · 17 Jul 2016 · 477pp · 75,408 words

The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values

by Sam Harris · 5 Oct 2010 · 412pp · 115,266 words

Heart of the Machine: Our Future in a World of Artificial Emotional Intelligence

by Richard Yonck · 7 Mar 2017 · 360pp · 100,991 words

The Pattern Seekers: How Autism Drives Human Invention

by Simon Baron-Cohen · 14 Aug 2020

Space at the Speed of Light: The History of 14 Billion Years for People Short on Time

by Becky Smethurst · 1 Jun 2020 · 71pp · 20,766 words

The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph From the Frontiers of Brain Science

by Norman Doidge · 15 Mar 2007 · 515pp · 136,938 words

The Equality Machine: Harnessing Digital Technology for a Brighter, More Inclusive Future

by Orly Lobel · 17 Oct 2022 · 370pp · 112,809 words

When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within Reach

by Ashlee Vance · 8 May 2023 · 558pp · 175,965 words

Flash Crash: A Trading Savant, a Global Manhunt, and the Most Mysterious Market Crash in History

by Liam Vaughan · 11 May 2020 · 268pp · 81,811 words

Leadership by Algorithm: Who Leads and Who Follows in the AI Era?

by David de Cremer · 25 May 2020 · 241pp · 70,307 words

Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net's Impact on Our Minds and Future

by John Brockman · 18 Jan 2011 · 379pp · 109,612 words

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by Roger McNamee · 1 Jan 2019 · 382pp · 105,819 words

Interplanetary Robots

by Rod Pyle

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by Guy Standing · 13 Jul 2016 · 443pp · 98,113 words

The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

by Kevin Kelly · 6 Jun 2016 · 371pp · 108,317 words

On the Future: Prospects for Humanity

by Martin J. Rees · 14 Oct 2018 · 193pp · 51,445 words

The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us

by Robert H. Frank, Philip J. Cook · 2 May 2011

The Ethical Algorithm: The Science of Socially Aware Algorithm Design

by Michael Kearns and Aaron Roth · 3 Oct 2019

Future War: Preparing for the New Global Battlefield

by Robert H. Latiff · 25 Sep 2017 · 158pp · 46,353 words

In the Land of Invented Languages: Adventures in Linguistic Creativity, Madness, and Genius

by Arika Okrent · 1 Jan 2009 · 226pp · 75,783 words

Through the Glass Ceiling to the Stars: The Story of the First American Woman to Command a Space Mission

by Eileen M. Collins and Jonathan H. Ward · 13 Sep 2021 · 394pp · 107,778 words

Einstein's Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond the Quantum

by Lee Smolin · 31 Mar 2019 · 385pp · 98,015 words

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by Nate Silver · 12 Aug 2024 · 848pp · 227,015 words

The Great Divergence: America's Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It

by Timothy Noah · 23 Apr 2012 · 309pp · 91,581 words

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

by Jim Al-Khalili · 28 Sep 2010 · 467pp · 114,570 words

The Big Nine: How the Tech Titans and Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity

by Amy Webb · 5 Mar 2019 · 340pp · 97,723 words

The Behavioral Investor

by Daniel Crosby · 15 Feb 2018 · 249pp · 77,342 words

The Little Black Book of Decision Making

by Michael Nicholas · 21 Jun 2017

Same as Ever: A Guide to What Never Changes

by Morgan Housel · 7 Nov 2023 · 210pp · 53,743 words

Infinite Ascent: A Short History of Mathematics

by David Berlinski · 2 Jan 2005 · 158pp · 49,168 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

Trend Following: How Great Traders Make Millions in Up or Down Markets

by Michael W. Covel · 19 Mar 2007 · 467pp · 154,960 words

My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance

by Emanuel Derman · 1 Jan 2004 · 313pp · 101,403 words

McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld

by Misha Glenny · 7 Apr 2008 · 487pp · 147,891 words

The Battery: How Portable Power Sparked a Technological Revolution

by Henry Schlesinger · 16 Mar 2010 · 336pp · 92,056 words

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 11 Apr 2011 · 740pp · 217,139 words

Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road

by Matthew B. Crawford · 8 Jun 2020 · 386pp · 113,709 words

Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms Everybody

by Helen Pluckrose and James A. Lindsay · 14 Jul 2020 · 378pp · 107,957 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Epic Win for Anonymous: How 4chan's Army Conquered the Web

by Cole Stryker · 14 Jun 2011 · 226pp · 71,540 words

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by Nouriel Roubini · 17 Oct 2022 · 328pp · 96,678 words

Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World

by Don Tapscott and Alex Tapscott · 9 May 2016 · 515pp · 126,820 words

Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines

by Thomas H. Davenport and Julia Kirby · 23 May 2016 · 347pp · 97,721 words

Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

by Eric Topol · 1 Jan 2019 · 424pp · 114,905 words

The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives

by Leonard Mlodinow · 12 May 2008 · 266pp · 86,324 words

NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity

by Steve Silberman · 24 Aug 2015 · 786pp · 195,810 words

Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order

by Parag Khanna · 4 Mar 2008 · 537pp · 158,544 words

Science in the Soul: Selected Writings of a Passionate Rationalist

by Richard Dawkins · 15 Mar 2017 · 420pp · 130,714 words

SUPERHUBS: How the Financial Elite and Their Networks Rule Our World

by Sandra Navidi · 24 Jan 2017 · 831pp · 98,409 words

Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers

by Timothy Ferriss · 6 Dec 2016 · 669pp · 210,153 words

Lonely Planet London City Guide

by Tom Masters, Steve Fallon and Vesna Maric · 31 Jan 2010

SuperFreakonomics

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 19 Oct 2009 · 302pp · 83,116 words

Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World

by Timothy Garton Ash · 23 May 2016 · 743pp · 201,651 words

The Elements of Marie Curie

by Dava Sobel · 20 Aug 2024 · 346pp · 96,466 words

Sunfall

by Jim Al-Khalili · 17 Apr 2019 · 381pp · 120,361 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

Fifty Degrees Below

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 25 Oct 2005 · 560pp · 158,238 words

The Gene Machine

by Venki Ramakrishnan

Dreams of Leaving and Remaining

by James Meek · 5 Mar 2019 · 232pp · 76,830 words

Demystifying Smart Cities

by Anders Lisdorf

Eleanor Rigby: A Novel

by Douglas Coupland · 29 May 2006 · 247pp · 65,550 words

Discover Great Britain

by Lonely Planet · 22 Aug 2012

8 Day Trips From London

by Dee Maldon · 16 Mar 2010 · 32pp · 7,759 words

Virus of the Mind

by Richard Brodie · 4 Jun 2009 · 289pp · 22,394 words

Citation Needed: The Best of Wikipedia's Worst Writing

by Conor Lastowka and Josh Fruhlinger · 14 Oct 2011 · 158pp · 16,993 words

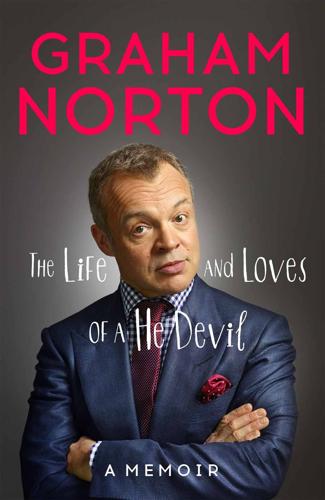

The Life and Loves of a He Devil: A Memoir

by Graham Norton · 22 Oct 2014 · 225pp · 78,025 words

Meantime: The Brilliant 'Unputdownable Crime Novel' From Frankie Boyle

by Frankie Boyle · 20 Jul 2022 · 286pp · 86,480 words

Scary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our World

by Mo Gawdat · 29 Sep 2021 · 259pp · 84,261 words

No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention

by Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer · 7 Sep 2020 · 317pp · 89,825 words

The City and the Stars / The Sands of Mars

by Arthur C. Clarke · 23 Oct 2010 · 542pp · 163,735 words

The Lights in the Tunnel

by Martin Ford · 28 May 2011 · 261pp · 10,785 words

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking

by Malcolm Gladwell · 1 Jan 2005 · 264pp · 90,379 words

The Orbital Perspective: Lessons in Seeing the Big Picture From a Journey of 71 Million Miles

by Astronaut Ron Garan and Muhammad Yunus · 2 Feb 2015

Exponential Organizations: Why New Organizations Are Ten Times Better, Faster, and Cheaper Than Yours (And What to Do About It)

by Salim Ismail and Yuri van Geest · 17 Oct 2014 · 292pp · 85,151 words

Drugs 2.0: The Web Revolution That's Changing How the World Gets High

by Mike Power · 1 May 2013 · 378pp · 94,468 words

Spin

by Robert Charles Wilson · 2 Jan 2005 · 541pp · 146,445 words

With the End in Mind

by Kathryn Mannix · 29 Dec 2017 · 316pp · 101,950 words

Some Remarks

by Neal Stephenson · 6 Aug 2012 · 335pp · 107,779 words

We Are Anonymous: Inside the Hacker World of LulzSec, Anonymous, and the Global Cyber Insurgency

by Parmy Olson · 5 Jun 2012 · 478pp · 149,810 words

E=mc2: A Biography of the World's Most Famous Equation

by David Bodanis · 25 May 2009 · 349pp · 27,507 words

The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity

by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott · 1 Jun 2016 · 344pp · 94,332 words

The Four: How Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google Divided and Conquered the World

by Scott Galloway · 2 Oct 2017 · 305pp · 79,303 words

Scotland’s Jesus: The Only Officially Non-Racist Comedian

by Frankie Boyle · 23 Oct 2013

A Year of Living Danishly: My Twelve Months Unearthing the Secrets of the World's Happiest Country

by Helen Russell · 14 Sep 2015 · 322pp · 99,918 words

The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health--And How We Must Adapt

by Sinan Aral · 14 Sep 2020 · 475pp · 134,707 words

Generation A

by Douglas Coupland · 2 Jan 2009 · 312pp · 78,053 words

Bitcoin: The Future of Money?

by Dominic Frisby · 1 Nov 2014 · 233pp · 66,446 words

Odd Girl Out: An Autistic Woman in a Neurotypical World

by Laura James · 5 Apr 2017 · 249pp · 80,762 words

Wonders of the Universe

by Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen · 12 Jul 2011

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect

by Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie · 1 Mar 2018

Work! Consume! Die!

by Frankie Boyle · 12 Oct 2011

The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of How Social Media Rewired Our Minds and Our World

by Max Fisher · 5 Sep 2022 · 439pp · 131,081 words

Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism

by Sarah Wynn-Williams · 11 Mar 2025 · 370pp · 115,318 words

Exploring Everyday Things with R and Ruby

by Sau Sheong Chang · 27 Jun 2012

The Words You Should Know to Sound Smart: 1200 Essential Words Every Sophisticated Person Should Be Able to Use

by Bobbi Bly · 18 Mar 2009 · 251pp · 44,888 words

Help

by Simon Amstell · 15 Jan 2017 · 117pp · 36,809 words

Thinking in Bets

by Annie Duke · 6 Feb 2018 · 288pp · 81,253 words

Googled: The End of the World as We Know It

by Ken Auletta · 1 Jan 2009 · 532pp · 139,706 words

Hello World: Being Human in the Age of Algorithms

by Hannah Fry · 17 Sep 2018 · 296pp · 78,631 words

The Knowledge Illusion

by Steven Sloman · 10 Feb 2017 · 313pp · 91,098 words

Antisemitism: Here and Now

by Deborah E. Lipstadt · 29 Jan 2019 · 276pp · 71,950 words

Genius Makers: The Mavericks Who Brought A. I. To Google, Facebook, and the World

by Cade Metz · 15 Mar 2021 · 414pp · 109,622 words

The Art of Rest: How to Find Respite in the Modern Age

by Claudia Hammond · 5 Dec 2019 · 249pp · 81,217 words

Chaos Kings: How Wall Street Traders Make Billions in the New Age of Crisis

by Scott Patterson · 5 Jun 2023 · 289pp · 95,046 words

Elon Musk

by Walter Isaacson · 11 Sep 2023 · 562pp · 201,502 words

A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market

by John Allen Paulos · 1 Jan 2003 · 295pp · 66,824 words

Moonwalking With Einstein

by Joshua Foer · 3 Mar 2011 · 329pp · 93,655 words

The Knife's Edge

by Stephen Westaby · 14 May 2019 · 259pp · 85,514 words

The Content Trap: A Strategist's Guide to Digital Change

by Bharat Anand · 17 Oct 2016 · 554pp · 149,489 words

The Cultural Logic of Computation

by David Golumbia · 31 Mar 2009 · 268pp · 109,447 words

The Dark Cloud: How the Digital World Is Costing the Earth

by Guillaume Pitron · 14 Jun 2023 · 271pp · 79,355 words

The Trauma Chronicles

by Westaby, Stephen · 1 Feb 2023

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

Losing the Signal: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of BlackBerry

by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff · 6 Apr 2015 · 327pp · 102,322 words

The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom

by Simon Winchester · 1 Jan 2008 · 385pp · 105,627 words

Split-Second Persuasion: The Ancient Art and New Science of Changing Minds

by Kevin Dutton · 3 Feb 2011 · 338pp · 100,477 words

But What if We're Wrong? Thinking About the Present as if It Were the Past

by Chuck Klosterman · 6 Jun 2016 · 281pp · 78,317 words

Unequal Britain: Equalities in Britain Since 1945

by Pat Thane · 18 Apr 2010 · 241pp · 90,538 words

Hello, Habits

by Fumio Sasaki · 6 Nov 2020 · 195pp · 60,471 words

How Not to Grow Up: A Coming of Age Memoir. Sort Of.

by Richard Herring · 5 May 2010 · 368pp · 115,889 words

The Genius Within: Unlocking Your Brain's Potential

by David Adam · 6 Feb 2018 · 258pp · 79,503 words

Stolen Focus: Why You Can't Pay Attention--And How to Think Deeply Again

by Johann Hari · 25 Jan 2022 · 390pp · 120,864 words

Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life

by Daniel C. Dennett · 15 Jan 1995 · 846pp · 232,630 words

It's Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution, and Future of HBO

by Felix Gillette and John Koblin · 1 Nov 2022 · 575pp · 140,384 words

Planes, Trains and Toilet Doors: 50 Places That Changed British Politics

by Matt Chorley · 8 Feb 2024 · 254pp · 75,897 words

How to Fix the Future: Staying Human in the Digital Age

by Andrew Keen · 1 Mar 2018 · 308pp · 85,880 words