The Wisdom of Finance: Discovering Humanity in the World of Risk and Return

by

Mihir Desai

Published 22 May 2017

The father of Greek philosophy, the Dutch financial markets of the seventeenth century, and the entrepreneur behind Federal Express are excellent guides to understanding that question. Violet’s appreciation of self-knowledge as a prerequisite to the thoughtful use of options has deep historical resonance. Thales of Miletus, acknowledged as the father of Greek philosophy by no one less than Aristotle himself, is often credited both with the phrase “know thyself” and with originating the first options transaction. Thales earned his position as the only philosopher in the Seven Sages of Greece by pioneering the use of natural, instead of supernatural, explanations for phenomena, advocating hypothesis-driven thinking, and even managing to predict solar eclipses with the crudest of instruments.

…

In Consilience, Wilson began to outline his effort at nothing less than the unity of all knowledge, taking particular aim at the problem Snow had identified. Wilson traces his project to the “Ionian Enchantment,” an idea that all of the world’s workings can be explained by a few laws. And to whom did Wilson attribute that idea? The original source is none other than Thales of Miletus, our innovator of option securities and derivatives. Perhaps everything is connected. Wilson went on to explain his efforts to rectify the problem identified by Snow: “There is only one way to unite the great branches of learning and end the culture wars. It is to view the boundary between the scientific and literary cultures not as a territorial line but as a broad and mostly unexplored terrain awaiting cooperative entry from both sides.

…

See also mergers continuum of commitment, 112–13 Ford, William Clay, Sr., and Martha Parke Firestone, 118–19 marriages as mergers, 104–6 in modern America, 105–6 in Renaissance Florence, 100–101 in Thailand, 105 “Romance Without Finance” (Grimes, Little Feat), 98–99 Room with a View, A (Forster), 8, 89–91 Rothschild family, 8, 100, 104–5 Hannah Mayer and marriage, 105 James and marriage to Nicky Hilton, 106 Mayer Amschel and marriage, 104 Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom, 40 Russell, Bertrand, 14 S Salmon, Felix, 130 Schjeldahl, Peter, 32, 129 Scholes, Myron, 40 Seize the Day (Bellow), 48–49 Shakespeare, William, 8, 122 Sheldon, Sidney, 96 Shenk, Joshua Wolf, 139 Shkreli, Martin, 166 Shleifer, Andrei, 77 Simpsons, The (TV show), 28 Sliding Doors (film), 13 Sloan, Alfred P., 117 Smith, Adam, 121–22 Smith, Fred, 44–45 Snow, C. P., 175–77 Socrates, 168 Stevens, Wallace, xi, 7, 32–34, 170 disorder and chaos, 33–34 insurance executive, 32–33 T talent, etymology of, 58–59, 74 “Tale of Beryn” (Chaucer), 74 Talmud, 52 Thales of Miletus, 7, 42–43, 162, 177 Tiger Moms, 95 Tolstoy, Leo, 9, 162–64 tontines, 28–30 Tontine Coffee House, 28 Tootsie Roll Industries, 78–80, 83–85 transaction cost approach to mergers, 115 Trilogy of Desire (Dreiser), 165 Trollope, Anthony, 7, 38, 175 Trump, Donald, 127, 152 Turner, Ted, 108 “Two Cultures” (Snow), 175 “Two Tramps in Mud Time” (Frost), xiii Tynan, Kenneth, 96 U Ulysses (Joyce), 91–92 V Vaillant, George, 138–39 value creation and valuation, 7, 59 accounting vs. finance, 64 alpha generation or getting paid for beta, 71–73 destruction of value, 63 discounted cash flows, 65 measuring value creation, 64–67 stewardship and, 61–63, 74 terminal values, 66–67 weighted average cost of capital, 65 value of education, 65–66 value of housing, 66 van Doetechum, Lucas, 58 (illus.), 59 van Eyck, Jan, 97 (illus.), 103 Vega, Joseph de la, 5–6, 43–44 venture capital, 73, 82 Vishny, Robert, 77 W Wall Street (film), 165, 166 Warhol, Andy, 129 Washington, George, 142–43, 145 Watson, Thomas, 138 Wealth of Nations, The (Smith), 121 Weaver, Sigourney, 97–98 Wells Fargo, 80 Wesley, John, 63 West, Kanye, 99 Wheel of Fortune (TV show), 17–18 White, Vanna, 18 Whitney Museum of Modern Art, 140 Wilder, Gene, 94 Wilson, E.

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by

Mervyn King

and

John Kay

Published 5 Mar 2020

Simons, formerly a mathematics professor, employs brilliant (maths and physics) PhDs to devise algorithmic trading strategies to take very short-term positions in securities. But there is more in common in the approaches of these men than appears at first sight. Their exceptional intelligence is one; they have responded to the challenge of ‘if you’re so smart why aren’t you rich?’ It is evident from Soros’s writings that he has much in common with Thales of Miletus, and would prefer to be remembered for his ideas than his wealth. Buffett’s letters – and all-day stage performances at the Berkshire Hathaway AGM in Omaha, Nebraska – dispense genuine insights in the guise of homespun country wisdom. Simons has published papers in top mathematical journals.

…

But the lesson of experience is that there is no single approach to financial markets which makes money or explains ‘what is going on here’, no single narrative of ‘the financial world as it really is’. There is a multiplicity of valid approaches, and the appropriate tools, model-based or narrative, are specific to context and to the skills and judgement of the investor. We can indeed benefit from the insights of both Thales of Miletus and Harry Markowitz, and learn from both of the contradictory narratives of the world of finance propagated by Gene Fama and Bob Shiller. But we must also recognise the limits to the insights we derive from their small-world models. There are those in the finance sector who create programs which purport to define strategies that would maximise risk-adjusted returns.

…

The earnings stability they, and many other businesses, reported was properly a cause for concern, not congratulation; greater variability would have demonstrated a sounder basis for these earnings. The world is inherently uncertain and to pretend otherwise is to create risk, not to minimise it. Taleb describes ‘anti-fragility’ – positioning oneself to benefit from radical uncertainty and the unknowable future. The value of an option is increased by volatility. The details of Thales of Miletus’s transaction with the olive presses remain obscure – if indeed any such transaction actually occurred. Perhaps he made a futures contract with the owners of the olive presses, perhaps he bought what we would now describe as a call option: the right, but not the obligation, to rent the presses at a price agreed in advance – a price which would seem low if the harvest was as good as Thales anticipated.

Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly

by

John Kay

Published 30 Apr 2010

After several years in which he described his corporate jet to his shareholders as “The Indefensible,” he sold it and bought the largest shared-ownership aircraft business—the whole company. Buffett’s life and approach—and perhaps even more that of George Soros, another of today’s legendary investors—was foretold by Aristotle’s account of Thales of Miletus:People had been saying reproachfully to him that philosophy was useless, as it had left him a poor man. But he, deducing from his knowledge of the stars that there would be a good crop of olives, while it was still winter, and he had a little money to spare, used it to pay deposits on all the oil-presses in Miletus and Chios, thus securing their hire.

…

root method Rotella, Bob Rousseau, Jean-Jacques rules Saint-Gobain salesmen Salomon Brothers Samuelson, Paul Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral Scholes, Myron science scorecard Scottish Enlightenment Sculley, John Sears securities selfish gene September 11 attacks (2001) shareholder value share options Sieff, Israel Sierra Leone Simon, Herbert simplification Singapore Singer Smith, Adam Smith, Ed Smith, Will SmithKline soccer (English football) social contract socialism social issues socialist realism sociopaths Solon Sony Sony Walkman Soros, George Soviet Union sports Stalin, Joseph “Still Muddling, Not Yet Through” (Lindblom) Stockdale, James Stockdale Paradox stock prices Stone, Oliver successive limited comparison sudoku Sugar, Alan Sunbeam Sunstein, Cass Super Cub motorcycles superstition surgery survival sustainability Taleb, Nassim Nicholas Tankel, Stanley target goals teaching quality assessment technology see also computers teleological fallacy telephones Tellus tennis Tetlock, Philip Tet Offensive (1968) Thales of Miletus Thornton, Charles Bates “Tex” tic-tac-toe Tolstoy, Leo transnational corporations transportation Travelers Treasury, U.S. trials Trump, Donald TRW 2001: A Space Odyssey Typhoon (Conrad) ultimatum games uncertainty United Nations United States Unités d’Habitation unplanned evolution urban planning value at risk (VAR) van Gogh, Vincent van Meegeren, Han Vasari, Giorgio Vermeer, Johannes Victorian era Vietnam War Vioxx volatility Wall Street Walton, Sam Wason, Peter Wason test wealth Wealth of Nations, The (Smith) Weill, Sandy Weir, Peter Welch, Jack Whately, Archbishop What Is to Be Done?

AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War

by

Tom McNichol

Published 31 Aug 2006

As we now know, the fur transferred negatively charged electrons to the amber, giving it an imbalanced charge, which in turn attracted the straw. The phenomenon would later give electricity its name: elecktron is the Greek word for amber. Even as humans struggled to understand electricity, the subject continued to be clouded by superstition. Thales of Miletus, an early Greek philosopher and mathematician, interpreted the curious properties of amber as evidence that objects were alive and possessed immortal souls. Greek mythology explained electricity by associating lightning with Zeus, the supreme god, who threw bolts of lightning down from the heavens to vent his anger at enemies below.

…

See Batteries Swan, Joseph, 42 T Tafero, Jesse, 127 Tate, Alfred, 133 Telluride (Colorado), Ames power plant, 129–130 Tesla, Nikola: background of, 70–73; collaborated with Westinghouse, 78, 82–84; at Columbian Exposition, 137, 138–139; contrast between Edison and, 69–70, 76, 77–78, 165–166; on DC motor, 73–74; death of, 166–167; eccentricities of, 70–71, 163–164, 165, 166; Edison’s opinion of, 84; given Edison Medal, 165; invented induction motor, 74–75, 82–83, 168; met and worked for Edison, 69–70, 75, 76, 77; Niagara Falls power plant dream of, 72, 141; polyphase system of, 82–83, 137, 168; sources of information on, 188–189; stayed out of Brown/Westinghouse challenge, 113; unrealized inventions of, 164–165, 166, 167–168; on Westinghouse, 162 Tesla coil, 164 Thales of Miletus, 7 Thompson, H. O., 61 Thomson, William (Lord Kelvin), 28, 139, 140 Thomson-Houston, merged with Edison General Electric Company, 131–132, 133–134 Topsy the elephant: execution of, 145–146, 152–154; film of electrocution of, 152–153, 154, 188; history of unmanageability of, 143–144; memorial to, 189; planned hanging of, 144–145 Toshiba, 182, 184 Transformer: first American AC power plant using, 82; Gaulard-Gibbs, 66, 81; invention of, 23; long-distance transmission of AC enabled by, 80 U Virgil, 7 Vitascope, 151–152 Volta, Alessandro, 22 Voltage: for AC vs.

Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

by

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Published 27 Nov 2012

A lot of things people call robust or resilient are just robust or resilient, the other half are antifragile. APPENDIX: THE TRIAD, OR A MAP OF THE WORLD AND THINGS ALONG THE THREE PROPERTIES Now we aim—after some work—to connect in the reader’s mind, with a single thread, elements seemingly far apart, such as Cato the Elder, Nietzsche, Thales of Miletus, the potency of the system of city-states, the sustainability of artisans, the process of discovery, the onesidedness of opacity, financial derivatives, antibiotic resistance, bottom-up systems, Socrates’ invitation to overrationalize, how to lecture birds, obsessive love, Darwinian evolution, the mathematical concept of Jensen’s inequality, optionality and option theory, the idea of ancestral heuristics, the works of Joseph de Maistre and Edmund Burke, Wittgenstein’s antirationalism, the fraudulent theories of the economics establishment, tinkering and bricolage, terrorism exacerbated by death of its members, an apologia for artisanal societies, the ethical flaws of the middle class, Paleo-style workouts (and nutrition), the idea of medical iatrogenics, the glorious notion of the magnificent (megalopsychon), my obsession with the idea of convexity (and my phobia of concavity), the late-2000s banking and economic crisis, the misunderstanding of redundancy, the difference between tourist and flâneur, etc.

…

Thus he broke a bit with the purported Stoic habit: he kept the upside. In my opinion, if previous Stoics claimed to prefer poverty to wealth, we need to be suspicious of their attitude, as it may be just all talk. Since most were poor, they might have fit a narrative to the circumstances (we will see with the story of Thales of Miletus the notion of sour grapes—cognitive games to make yourself believe that the grapes that you can’t reach taste sour). Seneca was all deeds, and we cannot ignore the fact that he kept the wealth. It is central that he showed his preference of wealth without harm from wealth to poverty. Seneca even outlined his strategy in De beneficiis, explicitly calling it a cost-benefit analysis by using the word “bookkeeping”: “The bookkeeping of benefits is simple: it is all expenditure; if any one returns it, that is clear gain (my emphasis); if he does not return it, it is not lost, I gave it for the sake of giving.”

…

Book IV will take this idea to its natural conclusion and will show evidence (ranging from medieval architecture to medicine, engineering, and innovation) that, perhaps, our greatest asset is the one we distrust the most: the built-in antifragility of certain risk-taking systems. CHAPTER 12 Thales’ Sweet Grapes Where we discuss the idea of doing instead of walking the Great Walk—The idea of a free option—Can a philosopher be called nouveau riche? An anecdote appears in Aristotle’s Politics concerning the pre-Socratic philosopher and mathematician Thales of Miletus. This story, barely covering half a page, expresses both antifragility and its denigration and introduces us to optionality. The remarkable aspect of this story is that Aristotle, arguably the most influential thinker of all time, got the central point of his own anecdote exactly backward. So did his followers, particularly after the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution.

Smart Money: How High-Stakes Financial Innovation Is Reshaping Our WorldÑFor the Better

by

Andrew Palmer

Published 13 Apr 2015

An option to buy a share at ten dollars in six months’ time, say, is known as a call option; a put option gives the buyer the right to sell the same share at a specified price. Yet options predated even Zaccaria by more than fifteen hundred years. The first known call option was described by Aristotle, who recounts the story of a philosopher named Thales of Miletus (now part of Turkey), who paid a deposit for all the olive-oil presses in Miletus and Chios. This was, in effect, an option to control the market, a bet that paid off handsomely when that year’s crop of olives was a good one and Thales was able to charge pretty much what he wanted to have them pressed. *** THE HISTORY OF FINANCE until medieval Italy reveals something that can be easily forgotten in the aftermath of the recent global financial crisis: how essential finance is to solving some very basic human requirements.

…

Mungo’s, 96 Standard & Poor’s (S&P), 24, 49, 157, 184, 234 Standardization, 39–41, 45, 47 Stevens, David, 151–152 Stevens, Teresa, 151–153 Stock exchanges, 14–16 Stocker, Anil, 207, 217 Stop-loss orders, 56 Straw, Jack, 94 Structured Bioequity, xii–xiii Structured finance, 237–238 Structured investment vehicle, 37 Stub quotes, 56 Student loans, 164, 166–167, 169–171 Stumpf, John, 192 Subprime mortgage tranches, loss amounts on, 233 Subprime mortgages, x, 79, 197–198, 233 Sufi, Amir, 204 Summers, Larry, 180 Suppa, Enrico, 9 Sutherland, Martinez, 89–90, 95, 105, 112 Svenska Handelsbanken, 206–207 Swaps, credit-default, 29–30 Swaps, interest-rate, 29 Swaziland, social-impact bonds (SIBs) in Sweden, banking crisis in, 75 Syndicated loans, 41 Tail risks, 221, 237 Tanzania, financial liberalization and, 34 Testosterone and cortisol, effect of on risk appetite and aversion, 116 Thailand, insurance claims for flooding, 225 Thaler, Richard, 137 Thales of Miletus, 10 Thayer, Ignacio, 210–211 Thiel, Peter, 163 This Time is Different (Reinhart and Rogoff), 35 Titmuss, Richard, 110 TransferWise, 190–192 Trente demoiselles de Genève, 22 True Link Financial, 144 Tufano, Peter, 59, 213–214 Tulipmania, 33, 36 Tversky, Amos, 137 UBS, 60 Uganda, social-impact bonds (SIBs) in, 103 Unbanked households, 200 United States aggregate value of property, 69 consumer debt, 183, 204 corporate debt, 120 cost of diagnosed diabetes, 102 cost of entitlements, 100 credit card debt, 183 general solicitation by private firms, 153–154 government interest in alternatives to student debt, 168 government spending, 99 home-ownership rates, 28, 85, 170 household debt, 205 leverage ratio, 2007, 77 life expectancy, 125 median house price, 70 monetary charitable gifts, 109 money raised through IPOs, 120 mortgage debt, 69 nonprofits in, 105–106 prepaid cards, 203 property bubbles, 74–75 real estate cycles, 237 savings-and-loan crisis (1990s), 30 social-impact bonds (SIBs), 98 student debt, 169 Unsecured lending, 206 Upstart, 166–168, 173, 175, 182 Used-car market, use of heuristics in, 46 Vega, Joseph de la, 24 Venture capital (VC), 150–151 Veterans, SIB program for, 102 Veterans Support Organization, 102 Viatical settlements, 142 Victory Loans, 28 Vishny, Robert, 42, 44 Volcker, Paul, xv, 30 Wachovia, xiv Wadhwa, Vivek, xv Warren, Elizabeth, xiv Washington Mutual, xiv Westlake, Darren, 153–154, 158, 161–162 “What Everybody Ought to Know About This Stock and Bond Business” Merrill Lynch ad, 28 When the Money Runs Out (King), 99 Wonga, 203, 205, 208 Woo, Gordon, 221–222, 227–229, 231, 233, 238 World Bank, 169 Wren, Christopher, 16 Wyman, Oliver, 204 Yale University, income-contingent financing program of, 165 Yale University, study of loss aversion, 136 Yunus, Muhammad, 203 Zaccaria, Benedetto, 9 ZestFinance, 199, 201, 205–206 Zombanakis, Minos, 41 Zopa, 181, 187, 188, 195 Zuckerberg, Mark, 174

The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number

by

Mario Livio

Published 23 Sep 2003

PYTHAGORAS AND THE PYTHAGOREANS Pythagoras was born around 570 B.C. in the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea (off Asia Minor), and he emigrated sometime between 530 and 510 to Croton in the Dorian colony in southern Italy (then known as Magna Graecia). Pythagoras apparently left Samos to escape the stifling tyranny of Polycrates (died ca. 522 B.C.), who established Samian naval supremacy in the Aegean Sea. Perhaps following the advice of his presumed teacher, the mathematician Thales of Miletus, Pythagoras probably lived for some time (as long as twenty-two years, according to some accounts) in Egypt, where he would have learned mathematics, philosophy, and religious themes from the Egyptian priests. After Egypt was overwhelmed by Persian armies, Pythagoras may have been taken to Babylon, together with members of the Egyptian priesthood.

…

The phrase of the German poet Goethe—“of all peoples the Greeks have dreamt the dream of life the best”—is only a small tribute to the pioneering efforts of the Greeks in branches of knowledge that they invented and denominated. However, even the accomplishments of the Greeks in many other fields pale in comparison with their awe-inspiring achievements in mathematics. In the span of only four hundred years, for example, from Thales of Miletus (at ca. 600 B.C.) to “the Great Geometer” Apollonius of Perga (at ca. 200 B.C.), the Greeks completed all the essentials of a theory of geometry. The Greek excellence in mathematics was largely a direct consequence of their passion for knowledge for its own sake, rather than merely for practical purposes.

The Wisdom of Frugality: Why Less Is More - More or Less

by

Emrys Westacott

Published 14 Apr 2016

Naturally, those who have made their millions are likely to see this as just sour grapes on the part of the philosophers, who, they will point out, have rarely found a lucrative market for their ideas or their services. To this snide observation philosophers have traditionally responded by pointing to the example of Thales of Miletus, who flourished around 600 BCE and is commonly identified as the first Western philosopher. Thales, so the story goes, realized from his meteorological observations that there would be a bumper crop of olives later in the year. So he shrewdly bought up all the olive presses in the region where he lived, and when harvesting season arrived, he rented them out at a great profit.

…

See also Stoics Stoics, 8, 23–24, 50–51, 55, 60, 67, 73, 75, 88, 89, 98, 101, 105, 107, 108, 128, 141, 148, 154, 171, 272 sunk cost fallacy, 144–45 Taoism, 128 technological change, 17–18, 206, 228, 280–83 technology, 254; as solution to environmental problems, 269–71; and simplicity, 22–23, 34; and work, 80 Thales of Miletus, 48 Thoreau, Henry David, 7, 19, 21, 24–27, 29, 34, 79, 88, 117, 120, 131, 137, 166, 248, 253 thrift, 2, 13; etymology of “thrift,” 10. See also frugality; living cheaply; simple living The Tightwad Gazette, 2 Tolstoy, Leo, 32, 64, 124 toughness: reasons for praising, 42–43. See also hardiness tourism, 179 tranquillity, 50; Faustian critique of, 184–85.

The Battery: How Portable Power Sparked a Technological Revolution

by

Henry Schlesinger

Published 16 Mar 2010

For one thing, it provides a welcome relief from the tame textbook pageants of politics, personalities, wars, and dates or the sour revisionist history in which flaws overshadow accomplishments currently in favor. And, with few exceptions, science and technology tend to progress in an orderly, logical manner.1 The time lines are remarkably clear, even in the ancient world. As far back as 600 BC, Thales of Miletus was already exploring the mysteries of nature. Known as one of the Seven Wise Men of ancient Greece and the father of modern mathematics, Thales left no writing. All that exists of his work are scattered anecdotes from Plato and Aristotle. But even this anecdotal evidence shows the first tenuous, unsteady steps of scientific thought.

…

B., 129 Sturgeon, William, 74–75, 80, 81, 82, 86, 89, 105 submarine battery, 108, 127 superstition, 4–9, 10 death of, 10–38 surface-to-air missiles, 248 Swammerdam, Jan, Biblia Naturae, 40 Swan, Joseph, 147 Sylvania, 248 tattoo machine, 171 telegraph, 50, 67, 89, 96, 97–130, 142, 143, 150, 153, 156, 157, 159 business, 111–13, 118, 131–33 consumer products, 131–32 financial industries, 133, 134–39 local time and, 116–18 military use, 129–30 Morse, 103–109, 109, 110–12, 120, 130, 206, 248–49 operators, 114–15, 132–34, 150 optical Chappe system, 98–99, 100, 103, 112, 123 patents, 104, 105 transatlantic, 118–30 transcontinental, 115 Wheatstone and Cooke, 103–105, 107, 120 wireless, 184–97, 198–212 telemachon, 148 telephone, 143, 157–61, 200 Bell and, 157–60 patents, 151, 157–60 societal place of, 160–61 transatlantic, 245 television, 178, 238, 253, 255 Telimco Wireless Telegraph Outfit, 198–99, 204, 204 terminology, 37, 49, 76–77, 81, 128–29, 142 Tesla, Nikola, 187, 278 Texas Instruments, 252–54, 257, 261, 263–64, 268, 277 Thackeray, William Makepeace, 120 Thales of Miletus, 2–3, 4 theatrical lighting, 125, 147, 153 Thomson, Joseph John, 176–79 Thomson, William, 124–27 Thoreau, Henry David, 115 Walden, 119 Tiffany & Co., 123, 175 time, standardized, 117–18 Timochares, 5 Titanic, sinking of, 205–206 Tom Thumb radio, 251 Toyota Prius, 281 toys, electric, 243, 249, 250, 255 TRADIC, 247 transistor radios, 251–57, 257, 258–61, 263 alien concept, 259 popular culture and, 256–58 transistors, 244–49, 262 early, 244–49 military, 248–49, 263 patents, 247 transportation, 100 Trowbridge, John, 188 Truman, Harry, 247 Tsushin, Kogyo, 258 tungsten filaments, 264 Twain, Mark, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, 97, 108–109 typewriter, 170–71 ultracapacitors, 279–80 Urry, Lewis Frederick, 249–50, 272 vacuum tubes, 208, 208, 209, 210, 216, 217, 245, 248, 262 Vail, Alfred, 106–107, 111, 133 Vail, Theodore, 133 Verne, Jules, 203 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, 127–28 versorium, 13 Victoria, Queen of England, 123, 194 vodka-gin battery, 281 volt, 81, 128, 129 Volta, Alessandro, 39, 41–50, 58, 59, 65, 66, 129, 250 battery, 43–50, 52, 65, 67, 85, 108 voltage, 142 voltaic pile, 43–47, 47, 48–50, 52, 65, 73, 74, 85, 108 voltmeter, 74, 76, 104 Walker’s platinized carbon battery, 142 walkie-talkie, 231–33, 239, 275 Walkman, 259, 273 Wall Street, 106, 153, 219 1929 crash, 219 telegraph and, 134–39 watch, 240 electric, 240–43, 243 LCD, 268–69 water, 23, 24, 48, 52, 59, 67–68, 73 Watson, Thomas, 158 Watson, William, 28 watt, 128, 129 Watt, James, 129 Welker, Heinrich, 260 Wells, H.

You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves

by

Hiawatha Bray

Published 31 Mar 2014

But for all his mistakes, Ptolemy laid out the guiding principles for a truly scientific cartography.10 By this time, sailors had mastered a simple, almost magical, tool that let them determine their direction of travel. But the magnetic compass—ubiquitous now—was a long time coming. The naturally magnetic rock called lodestone had puzzled scholars for centuries. The earliest written mention of it was by Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus around 585 BC. There is also a curious Chinese account from the second century BC, which tells of the palace of emperor Ch’in Shi Huang Ti. The main gate of the palace was made of a huge lodestone that exerted such great force that men armed with iron weapons could not enter without being detected.

…

See Space Inertial Reference Equipment SPOT Image, 165–166, 168 Sprint, 116, 117 Sputnik, 75–77, 78, 84, 102, 107, 113, 146, 160 Spychips (Albrecht), 221 Stalin, Joseph, 67, 152, 153, 154 Stanton, Joshua, 170 Stingray, 217–218 Stockman, Hervey, 156 Stone, John, 23–24 Submarines, 18, 41 celestial navigation and, 47–48 inertial navigation and, 70–71, 80–81, 82, 86 missiles and, 81 nuclear, 48, 52, 80–82 radio technology and, 30 satellite technology and, 80–82, 86 SuperVision (Gilliom and Monahan), 212 Supreme Court, US, 211, 213–215 Surveillance EZ Pass toll system and, 220–221, 227–228 government and, 209–210 in hospitals, 222 law enforcement, 212–219 legal implications of, 209–210, 225–227 license-plate recognition (LPR) systems and, 218–219 locational privacy and, 210–212 “passive,” 221–222 radio-frequency identification (RFID) and, 219–225 in schools, 222–225 in workplace, 222 Taylor, Albert Hoyt, 37–38 Telegraph system, 22–23 Tendler, Robert, 114–115 Terrorism, 27, 65, 71, 79, 80, 112 Tesla, Nikola, 36–37, 124 Texas Instruments, 116 Text messaging, 183, 197, 204 Thales of Miletus, 8 Thomas, Clarence, 214 TIMATION, 97–99, 100, 101, 118–119 Time, 14–16 atomic clocks and, 94–96 cell phones and, 112 electrical systems and, 112–113 See also Clocks Tizard Mission, 39–40, 43 T-Mobile USA, 114, 116, 117, 136 Tomlinson, Roger, 173–174 TomTom, 138, 187, 188 Tosi, Alessandro, 24 Touchdown, 158 Tournachon, Gaspard-Félix, 147 Trans World Airlines, 34, 72 Transit satellite program, 84–87, 92, 93, 94, 106 Transportation Department, US, 118 Triangulation, 16–17, 28 Truman, Harry, 154 Tucker, Samuel M., 40 Tuve, Merle, 42–43, 45 TVA.

The 5 Types of Wealth: A Transformative Guide to Design Your Dream Life

by

Sahil Bloom

Published 4 Feb 2025

The engagement ring that made your eyes sparkle becomes the ring you need to upgrade because of its imperfections. Worse yet, the incessant quest for more had blinded me to the great beauty of what I had right in front of me. In a fable recorded in Plato’s early works, a philosopher named Thales of Miletus is walking along obsessively gazing at the stars, only to fall into a well that he did not see at his feet. A poetic retelling by Jean de La Fontaine concludes, How many folks, in country and in town, Neglect their principal affair; And let, for want of due repair, A real house fall down, To build a castle in the air?

…

S., 157 life arc, 49–50 Life Dinner, 160, 174–75 life expectancy, 151, 212, 231, 233, 270 Life Razor, 37–42, 44 examples of, 41–42 life satisfaction, 137, 207 lifestyle creep, 330, 351 Lion’s breath technique, 305 listening, 180 levels of, 184–85 lists, 86, 91–94 Lloris, Hugo, 46 Lockhart, Alexis, 59–60, 65 Lombardo, Guy, 59, 65 London School of Economics, 322 loneliness, 132, 137–41 longevity, 217–19, 276 long-term investment, 318, 328, 330–31, 333, 335–36, 352–60, 363, 365 loud listening, 180, 184 love languages, 169–70, 176 Lovell, Jim, 34–35 low competency pursuits, 235–36, 238 low stress, 304 Luck, Andrew, 266–67 Luther, Martin, 320 Lydians, 323 Lynch, John, 112 M macronutrients, 283–84, 291, 299–300 Magellan, Ferdinand, 320 Maggiulli, Nick, 333, 353 Management Time, 116–17, 119–20 Marcus Aurelius, 292 marriage (see family, time spent with; partner, time spent with) Marrison, Warren, 69 Martínez, Lautaro, 46 massage therapy, 286, 297 Mayan civilizations, 68 McConaughey, Matthew, 70 McGonigal, Jane, 264 Mead, Margaret, 134 measurement of time, 68–69 meditation, 224, 277 me listening, 184 meeting length, 101 memento mori, concept of, 66–67 memorization, 190–91 memory retention, 243–44 Mental Wealth, 24, 206–9, 215–56, 335, 361, 368 core pillars of, 217–26, 256 defined, 26 life arc example and, 49–50 Wealth Score quiz and, 31, 33 Mental Wealth Guide, 226–55 Feynman technique, 228, 240–42 hacks to know at twenty-two, 228–31 1-1-1 journaling method, 228, 254–55 power-down ritual, 228, 252–53 power of ikigai, 228, 232–33 Power Walk, 228, 250–51 pursuit mapping, 228, 234–39 Socratic method, 228, 245–47 space-repetition method, 228, 243–44 Think Day, 228, 248–49 mentorship, 188 Mercuriale, Girolamo, 272 Messi, Lionel, 46–48, 82 meta-skills for high-income future, 338, 348–49 Michelangelo, 269, 271 micronutrients, 284, 300 Middle Ages, 271 Middle Way, 211 Miller, Geoffrey, 154–55 Millionaire Next Door, The (Stanley), 327 Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (Dweck), 222 mindsets, 222–23 Mohenjo Daro, 135 money, origin of, 321–25 Money for Couples (Sethi), 341 morning routine, 289, 292–94 movement, 265, 269–70, 272, 277–82, 290–97, 307 in public speaking, 194–95 Munger, Charlie, 45, 170, 330 Murthy, Vivek, 139 Musk, Elon, 221, 315 N National Academy of Medicine, 284 National Geographic, 217 natural selection, theory of, 272 Netflix, 37 networking, 182 NeuroImage study, 250–51 neuroplasticity, 229 New Opportunity test, 113–14 New York Times, 161, 165, 180, 279 New Yorker, 47, 323 Newport, Cal, 74, 106, 252–53 Newton, Aubrie, 129–32 Newton, Eric, 129–32 Newton, Sir Isaac, 69, 80, 82 Newtonian time, 69 NeXT, 216 Noble Eightfold Path, 211 Nolan, Christopher, 70, 367 normalcy, state of, 214–15 Norton, Michael, 20 nutrition, 27, 265, 276–78, 282–85, 290–94, 298–301, 307 O Occam’s razor, 36 Okinawa, 151, 212, 232–33 Olympic Games, 271–72 On the Origin of Species (Darwin), 272 On the Shortness of Life (Seneca), 79 1-1-1 journaling method, 228, 254–55 optimal stress, 304 Outlive (Attia), 279 P paper money, 323–25 Pareto, Vilfredo, 274 Pareto principle, 274 Parkinson, Cyril Northcote, 100 Parkinson’s law, 100–101, 120 partner, time spent with, 63–64, 161, 168–75 Peloton, 273 Peripatetic school of philosophy, 250 Pes, Giovanni, 218 Phelps, Michael, 272–73 Philips Global Sleep Survey, 285 phone and email notifications, 73–74, 132 physical activity (see movement) physical touch, 169–70, 176 Physical Wealth, 24, 123, 263–67, 269, 274, 287, 335, 361, 368 core pillars of, 278–87, 307 defined, 26–27 life arc example and, 49–50 Wealth Score quiz and, 32–33 Physical Wealth Guide, 287–306 breathing protocols, 289, 304–6 common-sense diet, 289, 298–301 morning routine, 289, 292–94 Movement Training Plan, 289, 295–97 nine rules for sleep, 289, 302–3 Thirty-Day Challenge, 289, 290–91, 308–9 physiological sigh, 193, 305–6 Pilates, 281 Pixar Animation Studios, 187–89, 216 Plato, 7, 271 Plutarch, 271 Pollio, Marcus Vitruvius, 268 Polo, Marco, 323 Popova, Maria, 271 Poulain, Michael, 218 Power Walk, 228, 250–51 power-down ritual, 228, 252–53 Priorities List, 92–94 procrastination, 102–5 productivity, 95–100, 252 professional time, types of, 116–21 ProfitWell, 335 Project Blueprint, 276 proteins, 283–84, 291, 298, 300 sources of, 299 Protestant Reformation, 320 Prout, Dave, 76–78 Psychology of Money, The (Housel), 156, 332 public speaking guide, 160, 190–95 Pueblo Bonito ceremonial site, 135 purpose, as pillar of Mental Wealth, 217–20, 229, 232–39, 256 pursuit mapping, 228, 234–39 Pyrrhic victory, 23, 45, 314 Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, 22–24, 44 Q quality time, 169 quartz clock, 69 questions doorknob, 178–80 engaging, 183–84 Socratic method and, 245–47 stop-sign, 178–79 Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking (Cain), 229 R rainy-day fund, 350 Randolph, Marc, 37–39 Ravikant, Naval, 101, 156, 198 razors, 35–36 Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), 354–55 recovery, 278, 285–87, 290–91, 297, 302–7 Red Queen Effect, 70–71 Reddit, 144 Reddy, Vimala Pawar, 138–40 “Regrets for My Old Dressing Gown” (Diderot), 196 relationship-map exercise, 160, 164–67, 200–201 relationships (see children; coworkers; family; friends; partner) relativity, theory of, 69, 75 Renaissance, 269, 271 return-on-hassle spectrum, 338, 358–60 Ricard, Matthieu, 223–24 Richest Man Who Ever Lived, The (Steinmetz), 320 Ridgeway, Cecilia, 154–55 Right Now test, 112, 114 Rockefeller, John D., 225–26, 314, 325 Rome (ancient), 22–23, 44, 66, 69, 135, 268, 271–72 Roosevelt, Franklin Delano, 325 royalties, 356 Rumi, 27 S sales, as meta-skill, 348 Same as Ever (Housel), 332 sand clocks, 69 savings, 339, 341, 343, 350 scattered attention, 81–82 Schulz, Marc, 150, 164 Seelig, Tina, 245 semiautonomous delegation, 110–11 Seneca, 43, 79, 192 senses, boot-up sequence and, 107–8 service, acts of, 169 Sethi, Ramit, 341 7 Habits of Highly Successful People, The (Covey), 95 shared experience, as pillar of Social Wealth, 151 Sigmund, Archduke, 319 Sikhism, 68 Silicon Valley Bank, 324 Sisyphean struggle, 314 Sivers, Derek, 113 sleep, 277, 285–87, 289–91, 297, 302–3 Sloan, Greg, 143–45 Sloan, Katherine, 145 small businesses and start-ups, 355–56 Smith, Adam, 321–22 soccer, 46–47 social class, 137 social isolation, 139, 141 social media use, 139 Social Wealth, 24, 123, 129–58, 335, 361, 368 core pillars of, 149–58, 199 defined, 26 depth and breadth foundations of, 131 life arc example and, 49–50 Wealth Score quiz and, 31, 33 Social Wealth Guide, 158–98 anti-networking guide, 160, 182–86 brain trust, 160, 187–89 hacks to know at twenty-two, 160, 161–63 helped, heard, or hugged method, 160, 176–77 Life Dinner, 160, 174–75 making conversation, 160, 178–81 public speaking guide, 160, 190–95 relationship-map exercise, 160, 164–67, 200–201 rules for growing in love, 160, 168–73 status tests, 160, 196–98 software engineering, as meta-skill, 349 South Beach diet, 273 space, as pillar of Mental Wealth, 217, 223–26, 248–53, 256 space-repetition method, 228, 243–44 space-time, 69 Sparta, 270 Spencer, Herbert, 272 Spent: Sex, Evolution, and Consumer Behavior (Miller), 154–55 sport, 46–47, 272–73 spotlight effect, 192, 194 stability training, 281 Standard Oil, 225 Stanford University, 154, 216, 221, 245, 250, 266, 286, 305 Stanley, Thomas, 327 status defined, 154 earned, 150, 154–57, 190–99 Status Game, The (Storr), 154 Steinmetz, Greg, 320 stock market, 332–33, 342, 352–53, 360 Stoic philosophy, 66 Stonehenge, 135 stonewalling, 171–72 stop-sign question, 178–79 Storr, Will, 154 storytelling, as meta-skill, 348 strength training, 280–82, 293, 296, 307 stress elimination of, 193, 195, 304–6 states of, 304 Sumerian barley, 322 sundials, 69 support, as pillar of Social Wealth, 151 supportive relationships, 164–65, 200 surfing, 50–51 Swigert, Jack, 34 Sword of Damocles, 149 systems, defined, 46 T “Tail End, The” (Urban), 64–65 Tarentum, 22 task profiling, 109 tasks, important and urgent, 95–97 Thales of Miletus, 7 Think Day, 228, 248–49 Think Different Apple ad campaign, 315 Think Week, 248 Thirty-Day Challenge, 289–91, 308–9 Thompson, Derek, 345 Thor (god), 68 Through the Looking-Glass (Carroll), 70 Tim Ferriss Show, The (podcast), 78 Timane people, 155 time chronos and kairos, 75, 83 four types of professional, 116–21 measurement of, 68–70 paradox of, 79 passage of, 60–61 understanding, 69–70 worship of, 68, 70 time billionaires, 78–79 time-blocking, 115–16 time poverty, 74 Time Smart (Whillans), 74 Time Wealth, 24, 65, 335, 361, 368 core pillars of, 77–84, 124 defined, 25–26 life arc example and, 49–50 twelve systems for, 86 Wealth Score quiz and, 31, 33 Time Wealth Guide, 85–123 anti-procrastination system, 86, 102–5 Art of No, 86, 112–14 effective delegation, 86, 109–11 Eisenhower Matrix, 86, 95–97 Energy Calendar, 86, 89–90 energy creators, 86, 122–23 flow state, 86, 106–8 hard reset, 86–88 index card strategy, 86, 98–99 Parkinson’s law, 86, 100–101 time-blocking and professional time types, 86, 115–21 two-list exercise, 86, 91–95 to-do list, 98–99 Toy Story (movie), 81–82 Troy (movie), 66 Tuesday-dinner rule, 37–38 Turkey, 323 Twain, Mark, 6, 314, 346 U University of California, Berkeley, 285 University of California, Los Angeles, 305 University of Georgia, 327 University of Hong Kong, 250 University of North Carolina, 112 Urban, Tim, 64–65, 102 Uruk, 322 U.S.

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by

Eric Posner

and

E. Weyl

Published 14 May 2018

We will also see that the solution to restore competition is surprising: it actually involves giving institutional investors more control over companies—but over individual companies rather than over industries. The Monopolist with a Thousand Faces The word “monopoly” was coined by Aristotle in a discussion of the mathematician and philosopher Thales of Miletus, who showed the value of philosophy in practical affairs by cornering the market on olive presses ahead of a harvest.1 Yet during the early modern era, the major source of monopoly was not this type of individual initiative, but the state, which authorized well-connected individuals or groups to dominate various lines of business.

…

European systems of, 143–44 Taylor, Fred, 280 Tea Party, 3 “Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes” (Likert), 111 technofeudalism, 230–33 technology, 2; artificial intelligence (AI), 202, 208–9, 213, 219–24, 226, 228, 230, 234, 236, 241, 246, 248, 254, 257, 287, 292; automated video editing and, 208; biotechnology, 254; capitalism and, 34, 203, 316n4; climate treaties and, 265; common ownership self-assessed tax (COST) and, 71–72, 257–59; computers, 21 (see also computers); consumers and, 287; cybersquatters and, 72; data and, 210–13, 219, 222–23, 236–41, 244; diminishing returns and, 226, 229–30; distribution of complexity and, 228; facial recognition and, 208, 216–19; growth and, 255; human capital and, 293; hyperlinks and, 210; Hyperloop and, 30–33; immigrants and, 256–57; income distribution of companies in, 223; information, 139, 210; innovation and, 30–32, 34, 71, 172, 187, 189, 202, 258; intellectual property and, 26, 38, 48, 72, 210, 212, 239; Internet and, 21, 27, 51, 71, 210–12, 224, 232, 235, 238–39, 242, 246–48; job displacement and, 222, 253, 316n4; labor and, 210–13, 219, 222–23, 236–41, 244, 251, 253–59, 265, 274, 293, 316n4; machine learning (ML) and, 208–9, 213–14, 217–21, 226–31, 234–35, 238, 247, 289, 291, 315n48; marginal value and, 224–28, 247; markets and, 203, 286–87, 292; medical, 291; Moore’s Law and, 286–87; network effects and, 211, 236, 238, 243; neural nets and, 214–19; overfitting and, 217–18; pencils and, 278–79; programmers and, 163, 208–9, 214, 217, 219, 224; property and, 34, 66, 70–71; Quadratic Voting (QV) and, 264; Radical Markets and, 277, 285–86; rapid advances in, 4, 173; recommendation systems and, 289–90; robots and, 222, 248, 251, 254, 287; sea power and, 131; self-driving cars and, 230; server farms and, 217; siren servers and, 220–24, 230–41, 243; social media and, 231, 236, 251; spam and, 210, 245; surveillance and, 237, 293; thinking machines and, 213–20; wealth and, 254; websites, 151, 155, 221; World Wide Web and, 210 techno-optimists, 254–55, 316n1 techno-pessimists, 254–55, 316n2 TEDz talk, 169 tenant farmers, 37–38, 41 Thaler, Richard, 67 Thales of Miletus, 172 Theory of Price, The (Stigler), 49 Theory of the Leisure Class (Veblen), 78 Three Principles of the People (Sun), 46 Through the Looking-Glass (Carroll), 176 Tirole, Jean, 236–37 Tom Sawyer (Twain), 233, 237 trade barriers, 14 tragedy of the commons, 44 transportation, 136, 139, 141, 174, 207, 288, 291 trickle down theories, 9, 12 Trump, Donald, 12–14, 120, 169, 296n20 Turkey, 15 turnover rate, 58–61, 64, 76 Twain, Mark, 233, 237 Twitter, 117, 221 Uber, xxi, 70, 77, 117, 288 unemployment, 9–11, 190, 200, 209, 223, 239, 255–56 unions, 23, 94, 118, 200, 240–45, 316n4 United Airlines, 171, 191 United Arab Emirates (UAE), 151–52, 158–59 United Kingdom: British East India Company and, 21, 173; Corbyn and, 12, 13; democracy and, 95–96; House of Commons and, 84–85; House of Lords and, 85; labor and, 133, 139, 144; Labor Party and, 45; national health system of, 290–91; Philosophical Radicals and, 95; rationing in, 20; voting and, 96 United States: American Constitution and, 86–87; American Independence and, 95; Articles of Confederation and, 88; checks and balances system of, 87; Civil War and, 88; Cold War and, xix, 25, 288; common ownership self-assessed tax (COST) and, 71–76; democracy and, 86–90, 93, 95; Gilded Age and, 174, 262; gun rights and, 15, 90; H1–B program and, 149, 154, 162–63; income distribution in, 4–6; Jackson and, 14; labor and, 9–10, 130, 135–54, 157–61, 164–65, 210, 222; liberalism and, 24 (see also liberalism); lobbyists and, 262; Long Depression of, 36; markets and, 272, 288, 290; monopolies and, 21; New Deal and, 176, 200; Nixon and, 288; Occupy Wall Street and, 3; political campaign contributions and, 15; political corruption and, 27; populist tradition of, 12; primary system and, 93; Progressive movement in, 45; property and, 36, 38, 45, 47–48, 51, 71–76; Radical Markets and, 177, 182–83, 196, 201; religious liberty and, 15; Revolutionary War and, 88; stop-and-frisk law and, 89; technology and, 71–72; Trump and, 12–14, 120, 169, 296n20 United States v.

The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science

by

Michael Strevens

Published 12 Oct 2020

What would kill it is to let in the scents, the commotion, the delights of the outside world. CHAPTER 14 Care and Maintenance of the Knowledge Machine Research has given us hope that all Shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well Till the moment it’s not. It’s not. “POEM,” MAUREEN MCLANE, SAME LIFE NATURAL PHILOSOPHY BEGAN, as far as we know, when Thales of Miletus conjectured, in the sixth century BCE, that the elemental stuff of which the world was made was water. At that time, water was the lifeblood, if not of the universe, then certainly of the local economy: Miletus, controlling a harbor at the center of a vigorous trading network in the eastern Mediterranean, was in Thales’s day said to be the wealthiest city in the world.

…

P., 274, 275 Snow Crystals (Bentley), 170 snowflakes, 168–72, 169, 171 social institution, science as, 290 socialism, 14–15 social practice, modern science as, 275 Social Text (postmodernist journal), 262–63 soda, corporate-funded research and, 53 Sokal, Alan, 262–63 solar eclipse, 42–50, 73 solid behavior, 143 solid/fluid duality, 143–44 Solvay Conference on Physics and Chemistry (Brussels), 145, 145, 146 Soviet Union, 162 space Aristotle and, 123 in Cartesian physics, 132–33, 270 special creation, evolution vs., 28 special theory of relativity, 72, 114 spin, in wave function, 308n Spinoza, Baruch, 243 spiritual life, separation from civic life in 1600s, 246–47 spontaneous generation, 51–52, 82 “spores,” 51 Sprat, Thomas, 105, 166 Stalin, Joseph, 162 Standard Model, 101, 284, 318n Starn, Doug and Mike, 171 state, in quantum mechanics, 147–50 statistical analysis, 167–68 Stegosaurus, 224, 225 Stephen, Leslie, 174 “sterilization” of scientific argument defined, 161 and Newton, 311–12n prescribed by iron rule, 195, 196 parallels in courts of law, 309n and Royal Society, 249 and scientific papers, 164–66, 168 Stjerneborg (observatory), 114–15, 115 Stoics, 97–98 strangeness, in subatomic particles, 229–33, 231 Strickland, Hugh Edwin, 219 string theory, 284–85, 318n–319n Structure of Scientific Revolutions, The (Kuhn), 23–24, 137, 238 subatomic particles, 228–35 subjectivity; See also objectivity Eddington and, 48–49, 68–73, 83–84, 155–61 in interpretation of evidence, 57–58, 62–65, 79–82, 92–93, 288–89 and Kelvin’s estimation of age of Earth, 74–79 positive aspects of, 85–86 removal from scientific argument, See “sterilization” of scientific argument Todd Willingham trial and, 66–67 two sources of, 54 sun, 3, 301n sunfish, 221–22, 223, 226 superposition, 144, 147–50 SU(3) symmetry group, 230–32 symmetry, 169–72, 212, 230–32, 236–37 Tait, Peter Guthrie, 77, 78 technology Acheulean–Mousterian transition, 239–41, 240, 241 objectivity and, 168 science and, 64–65, 300n temperature gradient, 300–301n Terman, Lewis, 36 testability, of scientific ideas, 32; See also empirical testing “Testing Relativity from the 1919 Eclipse” (Kennefick), 298n textual criticism, 188 Thales of Miletus Bacon and, 304n and explanatory thinking, 117 on water as fundamental substance, 2, 142–43, 278 theology, See religion theoretical cohort auxiliary assumptions and, 79–81, 140 defined, 294 iron rule and, 102, 139–40 theory and, 71, 139 theory (generally) aesthetic judgment and, 235 Aristotle on, 201 assumptions and, 72 Baconian convergence and, 110 empirical data and, 104 explanatory power as sole criterion for judging, 195–96 Kuhn and, 23–25, 29, 38–40 partisans and, 57–58 plausibility rankings and, 79–82, 281 Popper and, 18–20, 38–40 science’s ability to eliminate old theories, 38 and shallow conception of explanation, 139 theoretical cohorts and, 71, 79–81, 139 Thirty Years’ War, 129, 135, 246–47, 247 Thompson, Sir Benjamin, Reichsgraf von Rumford, 90 Thompson, D’Arcy Wentworth, 220–27, 236, 273 Thomson, William, See Kelvin, Lord (William Thomson) Tolstoy, Leo, 264 top quark, 101 totalitarianism, 13, 162 transformations (geometrical), 221–27, 223 transmutation notebooks (Darwin), 218 tree of life, 219, 220, 229 TRH (hormone), 33–34, 37–38, 61–62, 99, 100 Trinitarianism, 250–52, 316n Trinity College, Cambridge University, 184 Newton and, 191 Newton as instructor, 135 Newton as student, 135 Newton’s Anglican ordination crisis, 250–52 Newton’s laboratory, 183, 184 Newton’s notebook, 183–85 Whewell and, 174–75, 204 two cultures (C.

The Lessons of History

by

Will Durant

and

Ariel Durant

Published 1 Jan 1968

558 B.C.), 29, 55–56, 57, 73 Sophists, 41, 49 South America, 30, 53, 84 Spain, 24, 53, 64, 83 Spanish Armada, 16 Sparta, 27, 29 Spencer, Herbert (1820–1903), 93 Spengler, Oswald (1880–1936), 89–90, 91 states, rise of, 90–91 Study of History, A (Toynbee), 69* Sulla, Lucius Cornelius (138–78 B.C.), 39 Sumeria, 13, 59 Sweden, 79 Switzerland, 23, 79 Sylvester I, Pope (r. 314–335), 45 Syracuse, Greek colony at, 29 Syria, 29 Szuma Ch’ien (B.C. 145 B.C.), 61 Taine, Hippolyte Adolphe (1828–93), 72* Talleyrand-Périgord, Charles-Maurice de (1754–1838), 90 Taranto, Greek colony at, 29 Tatars, 83 taxation, 56, 59–63, 66, 92 Ten Commandments, 40, 44 Teutons, 26, 30 Thales of Miletus (fl. 600 B.C.), 29 Thirty Years’ War, 28, 45 Thrasymachus (fl. 5th century B.C.), 39, 93 Thucydides (471?–?400 B.C.), 73, 100 Tiberius, Emperor of Rome (r. 14–37), 84 Tours, battle of (732), 24, 83 Toynbee, Arnold J. (1889– ), 69* trade routes, 15, 16, 53, 92 Trajan, Emperor of Rome (r. 98–117), 69 Treitschke, Heinrich von (1834–96), 26 Trichinopoly, 29 Trotsky, Leon (1877–1940), 66 Umbrians, 27 United States of America, 20, 21, 26, 30, 31, 42, 71, 100 industrial development, 16, 39, 40 agriculture and food supply, 22 morals and religion, 39, 40, 48, 50, 51, 96 concentration of wealth in, 55, 57 democracy in, 68, 76, 79, 91, 94, 96, 99 and Western civilization, 83, 84, 85, 91, 94, 97 Vandals, 27 Varangians, 28 Venice, 16, 92 Vico, Giovanni Battista (1668–1744), 88 Vinci, Leonardo da, see LEONARDO DA VINCI Virgil (70–19 B.C.), 53, 87 Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet; 1694–1778), 23, 40, 49, 53, 77, 92, 100, 101 Wagner, Richard (1813–83), 26 Wang An-shih (premier 1068–85), 62–63 Wang Mang, Emperor of China (r. 923), 62 war, 18–22 passim, 55, 60, 61, 66, 70, 76, 77, 79, 81–86, 93 air power in, 16 and morals and religion, 23, 24, 39, 40, 42, 44, 47, 49 causes of, 53, 81, 82 and science, 82, 95 Watt, James (1736–1819), 41 wealth, concentration of, 55–58, 70, 72, 77, 92 West, the, 53, 67, 96, 100 decline of, 16 Western Europe, 29, 40, 45, 84 civilization of 28–30, 49, 83, 94, 97 U.

The Grand Design

by

Stephen Hawking

and

Leonard Mlodinow

Published 14 Jun 2010

When the gods were pleased, mankind was treated to good weather, peace, and freedom from natural disaster and disease. When they were displeased, there came drought, war, pestilence, and epidemics. Since the connection of cause and effect in nature was invisible to their eyes, these gods appeared inscrutable, and people at their mercy. But with Thales of Miletus (ca. 624 BC–ca. 546 BC) about 2,600 years ago, that began to change. The idea arose that nature follows consistent principles that could be deciphered. And so began the long process of replacing the notion of the reign of gods with the concept of a universe that is governed by laws of nature, and created according to a blueprint we could someday learn to read.

The Little Book of Hedge Funds

by

Anthony Scaramucci

Published 30 Apr 2012

Sharpen your pencils. Take out your notebooks. It’s time for a bit of a history lesson. Inside the Olive Pit Like any other history lesson, our story begins in ancient Greece with renowned philosopher Aristotle preaching to his disciplines about the mathematician, philosopher, and daydreamer Thales of Miletus. Having predicted an abundant olive crop for the coming season, Thales struck up a deal with all of the local olive refiners in the region. In exchange for a large sum of money, he asked these unknowing farmers “for the right but not the obligation” to rent the entire olive pressing facility for a set fee for the duration of the year’s harvest.1 As luck would have it, Thales’ prediction proved to be true as the olive crop experienced a record-breaking harvest.

The Planets

by

Dava Sobel

Published 1 Jan 2005

The orderliness of their motions brought “cosmos” out of “chaos” in the same language, and inspired an entire lexicon for describing planetary positions. Just as the gods’ names still cling to the planets, Greek terms such as “apogee,” “perigee,” “eccentricity,” and “ephemeris” endure in astronomical discussions. The first observers to coin such words fill a roster of ancient heroes, from Thales of Miletus (624–546 B.C.), the founding Greek scientist who predicted a solar eclipse and questioned the substance of the universe, to Plato (427–347 B.C.), who envisioned the planets mounted on seven spheres of invisible crystal, nested one within the other, spinning inside the eighth sphere of the fixed stars, all centered on the solid Earth.* Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) later raised the number of celestial spheres to fifty-four, the better to account for the planets’ observed deviations from circular paths, and by the time Ptolemy codified astronomy in the second century A.D., the major spheres had been augmented further by ingenious smaller circles, called “epicycles” and “deferents,” required to offset the admitted complexities of planetary motion.

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by

Costas Lapavitsas

Published 14 Aug 2013

Interest is the augmentation of money by itself rather than through exchanging goods and is rightly called ‘birth’ (tokos) since money makes money; this is the most unnatural (para physin) manner of obtaining wealth. The various money-making methods of kapelike were not directly discussed by Aristotle, even though he mentioned extant accounts of individual successes in profit making. But there is no doubt about their complexity. Thus, Aristotle made reference to Thales of Miletus who, after being mocked for his philosopher’s poverty, sought to prove that philosophers could easily command the ways of chrematistike but chose not to do so (ou tout’ esti peri o spoudazousin). In the midst of winter Thales predicted that there was going to be a bumper olive crop, raised money and pledged the functioning of all the oil presses of Miletus and Chios.

…

Cornering the market in this manner (monopolian auto kataskeuazein) was a recognized principle of money making in Aristotle’s time. History does not tell us whether other impoverished Greek philosophers deployed their skills with similar success, but in the years of financialization plenty of economists have followed in the steps of Thales of Miletus with none of his disdain for the filthy business of money making. The commercial and predatory character of profit, particularly in its financial form, is also apparent in the forensic speeches of Demosthenes, the richest literary source on moneylending and its associated practices in Greek antiquity.

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by

Andrew W. Lo

and

Stephen R. Foerster

Published 16 Aug 2021

One of the first recorded accounts of such a transaction is related to the underlying price of olive oil presses. At the time, olive oil was used for making soap and for cooking and was also used as fuel for lamps and as a skin softener.10 After several years of poor harvests, the Greek philosopher and mathematician Thales of Miletus (known as one of the Seven Sages of Greece) used astronomy to predict an upcoming bumper olive crop. During the winter, he negotiated call options to buy the presses in the spring at their depressed current prices. He bought all the olive presses he could find from discouraged growers and made a fortune when the predicted bumper crop arrived.

…

Sharpe Associates established by, 74 Sharpe ratio, 74 Shiller, Robert (Bob), 226–54, 292; academic career of, 230–31; on bubbles, 241–43; connections to other pioneers, xiv; cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio and, 246–47; dissertation of, 230; on diversification, 252; early life of, 227–28; education of, 228–30; on efficient markets, 82, 97, 232–36; on Fed leadership’s expression of opinions about market, 237–40; on financial advisers, 253; on financial innovations, 253–54; housing price index of, 247–51; interest in economics, 228; MacroShares and, 250–51; market timing and, 252–53, 318; as Nobel Prize winner, 83, 243, 283; on overvaluation of stock market, 303–4; Perfect Portfolio of, 251–54, 317–18; on price-earnings ratio, 303; publications of, 230, 232–33, 249, 301; on rational expectations, 229–30, 232–34; relationship with Siegel, 300–301; on tulip bubble, 9; unconventional nature of, 231–32 Siegel, Bernard, 281 Siegel, Jeremy, 229, 239, 281–307; academic career of, 285–86; on asset allocation, 295, 306–7; on baby boomer retirement effect on investor portfolios, 299–300; connections to other pioneers, xiv; on cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, 301–2; dissertation of, 283–84; early life of, 281–82; education of, 282–83; on equity premium, 288–91; on exchange-traded funds, 304–5; on forward exchange rate, 284–85; on growth traps, 298–300; guidelines to successful investing, 305; on overvaluation of stock market, 303; Perfect Portfolio of, 305–7, 318–19; on price-earnings ratio, 297–98, 299, 302, 303, 305, 306, 307; publications of, 229, 281, 283–85, 288–95, 296–300, 305–6; relationship with Friedman, 285; relationship with Shiller, 300–301; on risk, 294–95; on technology sector overvaluation, 295–98; at WisdomTree Investments, 304 Siegel’s Paradox, 284–85 Simon, Herbert, 22 “A Simplified Model for Portfolio Analysis” (Sharpe), 61–62 Sims, Christopher, 230 Singer Corporation, Merton’s investment in, 176 single-index model, 58–61 Sinquefield, Rex, 46, 109 smart beta, Ellis on, 274 SmartNest, 189 Smith, Edgar Lawrence, 292 Smith, Harrison, 124 Société des Moulins de Bazacle, 8 Solow, Robert, 283 South Sea Company, 11–13 S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index, 248–51 speculation, investing vs., Markowitz on, 33–34 Sprenkle, Case, 152 “Stability of a Monetary Economy with Inflationary Expectations” (Siegel), 283–84 Standard & Poor’s (S&P), 248, 251 Standard Oil of New Jersey, growth trap and, 298–99 Steinberg, Jonathan (Jono), 304 Steinberg, Saul, 304 Steinberger, Jack, 174 Stewart, Ian, 148 Stigler, George, 166 stock market: bubbles in (see bubbles); business cycles and, Siegel’s interest in, 286–88; cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio and, 246–47; Fed leadership’s expression of opinions about, 237–40; irrational exuberance and, 237–39; Shiller/Siegel controversy over overvaluation of, 302–4; Trump’s election and, 301 stock market crashes: of Black Monday (October 19, 1987), 236–37; Fama on, 245; of 1929, Bogle family and, 114 Stocks for the Long Run (Siegel), 229, 281, 289, 291–95, 300, 305–6 stock splits, Fama’s research on, 90–93 Strange, Robert, 258 “Studies in the Theory of Risk Bearing” (Mossin), 71 Stulz, René, 108, 110–11 substitution swaps, 211 swaps, Leibowitz and Homer’s memorandum on, 211–12 Swensen, David, 219, 269, 270–71 target date funds, 224 Target Date Retirement Income Funds, 196, 197 taxes, 48, 322; Bogle on, 135; corporate, 1964 cut in, 260; Ellis on, 279 technical analysis, 88, 89 technology sector overvaluation, Siegel on, 295–98 terminal wealth, Scholes on, 167 Tesler, Lester, 87 Texas Instruments calculators, 161 Thaler, Richard (Dick): on equity premium, 290; on market efficiency, 245; as Nobel Prize winner, 83, 245, 290; publications of, 245; relationship with Fama, 245 Thales of Miletus, 4–5 Theiler, Max, as Nobel Prize winner, 174 The Theory of Finance (Fama and Miller), 108 The Theory of Interest, as Determined by Impatience to Spend Income and Opportunity to Invest It (Fisher), 15 The Theory of Investment Value (Williams), 15, 23, 28 “The Theory of Speculation” (Bachelier), 83 Thorndike, Doran, Paine & Lewis, 121 three-factor model, 102–5 Three P’s of Investments, 322–23 time value of money, 2 timing: achieving financial goals and, 332; market timing and, 318 Timmons, Bruce, 228 Tobin, James, 22, 39, 231 “To Get Performance, You Have to Be Organized for It” (Ellis), 261 tokens, for ancient record keeping, 2 Toronto Maple Leafs, 141 traditional index funds (TIFs), exchange-traded funds vs., 136–37 transfer prices, Sharpe’s interest in, 55 Treasury bills, Fama’s predictability study of, 105 Treasury bonds, Fama’s predictability study of, 106–7 Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), 193, 197, 198, 311, 322 Trente demoiselles de Geneve, 13–14 Treynor, Jack, 69–70, 347n46; “Market Value, Time, and Risk,” 69; research on option pricing, 149–50 trills, 253–54 Trump, Donald, Siegel and Shiller’s views on stock market effects of election of, 301 tulip bubble, 9–10 Tversky, Amos, 42, 83 Twain, Shania, 141 Twardowski, Jan, 127 underperformance, Ellis on, 272–73 Ur, financial district of, 3 Uspensky, J.

What We Cannot Know: Explorations at the Edge of Knowledge

by

Marcus Du Sautoy

Published 18 May 2016

Then around the fifth century BC things began to change as the ancient Greeks got their teeth into the subject. The algorithms come with arguments to justify why they will always do what it says on the tin or tablet. It isn’t simply that it’s worked the last thousand times, so it will probably work the next time: the argument explains why the proposal will always work. The idea of proof was born. Thales of Miletus is credited with being the first known author of a mathematical proof. He proved that if you take any point on the circumference of a circle and join that point to the two ends of a diagonal across the circle, then the angle you’ve created is an exact right angle. It doesn’t matter which circle you choose or what point on the circle you take, the angle is always a right angle.

…

415–18; certainty and 364–6; consciousness and see consciousness; conjectures as lifeblood of 420; cracking of great unsolved problems 375–8; dice and see dice; God and see God; infinity and see infinity; limit of senses and 417–18; mathematical universe hypothesis (MUH) 297–8; proof and 6, 366–73, 377–8, 401, 405–6, 417; proves that certain things are beyond knowledge 369–73, 401, 405–6, 417; quantum physics and see quantum physics; science vs. 364–6; theorems see under individual theorem name; timeless nature of 297–8; unknowns in see under individual area of mathematics; ‘unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics’ 298 see also individual area of mathematics Maxwell, James Clerk 34, 136, 142, 143, 419; Matter and Motion 47 May, Robert M. 51–3, 72; chaos theory and 48–54, 55, 56, 57, 72; ‘Simple Mathematical Models with Very Complicated Dynamics’ 48–51, 56 McCabe, Herbert 15, 181 McGurk effect 328 Mendeleev, Dmitri 89–90, 91, 106, 108, 116 Mercury 63–4, 190, 194 Méré, Chevalier de 24–5, 26 Mermin, David 154, 155 Messiaen, Olivier 305 MET office 46–7, 61–2 Michell, John 275 Michelson, Albert Abraham 10–11, 253, 254, 255, 275 microscopes 78–9, 88, 93, 126, 305, 307, 416 Milky Way 203, 204, 227 Millikan, Robert Andrews 142–3 mind-body problem 330–2 Minkowski, Hermann 261–2, 270 Mittag-Leffler, Gösta 39–41, 204, 399 Moon 20, 34, 37, 38, 189, 190, 198, 206, 250, 251, 267 Moore’s law 8, 281 Mora, Patricia 280 Morley, Edward 253, 254, 255, 275 Mount Wilson, California 105–6, 204 multiverse 227–35, 238, 242, 298, 382, 404–5 muon 104, 105, 106, 258–9 Museum of the History of Science 188 music 77, 78, 79, 80–1, 82, 85, 88, 89, 90, 101, 121, 122, 126, 127, 137, 138, 139, 140, 177, 191, 195, 308, 314, 369, 419 mysterianism 349–50, 351 National Physical Laboratory, London 252, 254 Nature 8, 48, 53 Navier–Stokes equations 34 Ne’eman, Yuval 115 Necker cube 321, 323, 328 Neddermeyer, Seth 104 negative curvature 210 negative numbers 371–2 Neptune 197, 227 neurons: ageing and 258, 259; C. elegans worm complete neuronal network published 4, 345, 349; consciousness and 5, 309, 311–14, 323–9, 340, 341, 342, 343–6, 347, 348, 349, 350, 351, 353, 359, 376–7; Jennifer Aniston neuron 4, 324–7, 347, 359; Ramón y Cajal discoveries 311–13, 348 neutrinos 105, 221, 407 neutron 79, 90, 95, 100–1, 103, 105, 106, 107, 110, 116, 119, 125, 126, 165, 166 New Scientist 2, 4 Newlands, John 90 Newton, Sir Isaac 5, 6, 28–9, 53, 86, 131, 141, 156, 168, 176, 179, 262, 272; calculus and 30–2, 87; dice and 35–6, 154; God and 71; gravity and 29, 30, 32, 33–4, 37, 38, 72, 88, 196, 278–9; laws of motion and 29, 32–7, 38, 67, 72, 78, 87–8, 97, 133, 143, 153, 154, 159, 278–9, 280; life of 29–30; Opticks 88, 134; Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica 29, 32–5, 88, 252, 257; planetary motion and 33–41, 72, 280; relativity and 257; space and time, view of absolute nature of 252, 253, 262; Theory of Everything and 35; theory of light 88, 134, 135, 141 Nishijima, Kazuhiko 109–10 Nobel Prize 5, 106, 143, 204, 236, 321 non-commutativity 164 novae 204 nuclear fusion 274 nucleons 107–8 number theory 378, 384–8, 401–2, 403, 404 observation, quantum physics and 148–58, 168–70, 173, 178 Occam’s razor 233 Old Babylonian Period 83 omega particle 115–16 ontology 70, 170, 177, 178, 179, 418 Oppenheimer, Robert 117 Oresme, Nicolas 190–1, 218, 235, 391–2, 393, 394 Oscar II of Norway and Sweden, King 37–8, 62 out-of-body experiences 328–30 Owen, Adrian 333–4 Pais, Abraham 109 Papplewick Pumping Station 137–8, 139 paradox of unknowability 413–14 parallax 200–1, 202 parallel postulate 378–80, 401 Paris, Jeff 388 Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank 307–8, 313–14 Pascal, Blaise 24–5, 26–8, 36; Pascal’s wager 26–8, 241, 242; Pensées 389 Penrose, Roger 277–8, 290, 291–6, 387 pentaquark 120, 124 Pepys, Samuel 35–6 perceptronium 356 Perelman, Grigori 375–6 periodic paths 38–9 periodic table 86–7, 89–92, 95, 97, 101, 103, 106, 116, 125, 274 Perrin, Jean Baptiste: Les Atomes 94 photoelectric effect 140–3, 147 photons 10, 108, 141, 147, 148, 149, 150, 155, 156, 163, 168–9, 207, 208, 220–1, 227–8, 284, 287, 291, 292 physics: limits of discoveries 10–11, 12, 20, 123, 405, 418; many worlds’ interpretation of 155–6; no mechanism to explain 230; tension between mathematics and 404–5; unification of general relativity and quantum physics 7, 168, 219, 220 see also under individual area of physics pions 106, 107, 108, 109, 110–11, 115, 118 Planck, Max: Planck constant 138–9, 141, 163, 407; Planck length 167–8, 407 Planck spacecraft 226 planets: detecting new 195–8, 200–1, 227; distances between 193–5; measuring time and 251, 259, 267, 269, 278–9, 280; modelling of future trajectories 63–4, 72; motion of 29, 33–41, 62–4, 72, 88, 193, 279, 280; multiverse and 231; music of the spheres and 81; new habitable 3; singularities and 280 Plato 81–2, 113, 188, 208–9, 304, 368, 373, 409–10, 412 Pleiades 20, 250 Plough or Big Dipper 190, 191, 213 Podolsky, Boris 172 Poincaré, Henri 4, 36–41, 42, 44, 62, 64, 375 Poisson, Siméon-Denis 34 Polaris star 188 Polkinghorne, John 69–70, 174–9, 240, 355 Popper, Karl 233, 239, 415 population dynamics 1–2, 48–51, 56, 62, 65, 176, 280–1 PORC conjecture 376–7, 388, 420 Preskill, John 289–90 prime numbers 8, 157, 404, 415 probability 21–2, 23–8, 35, 37, 60, 92, 94, 146–8, 153, 154, 155, 157, 158, 159, 162, 178, 308, 349, 403, 405, 408 proof: birth of idea 366–9; by contradiction 83–4, 243; certain knowledge and mistakes in mathematical 39–41, 377, 383–8, 402–3, 412–16; chance to establish more permanent state of knowledge and 6, 366–7; false 412–13 proprioception 416–17 proton 79, 90, 95, 98–9, 100, 101, 103, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 116, 117, 119–20, 123, 125, 126, 166 Proxima Centauri 188, 201, 202 punctuated equilibria 61 Pythagoras 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 89, 117, 127, 206, 243, 255, 256, 262, 324, 325, 326, 359, 363, 370, 374 qualia 325, 350, 357 quantum physics 11, 12, 28, 69, 70, 104, 126, 127, 131, 132, 133, 143–58, 159–83, 219, 220, 228–9, 231, 241, 274, 284, 288, 289, 297, 338, 354, 355, 402, 407, 408–9; black holes and 274, 284, 288, 289, 355; chaos theory and see chaos theory; Copenhagen interpretation of 178; counterintuitive nature of 132, 159, 164, 284; density of electron and 126; double-slit light experiment 134–6, 143, 144–7, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152–3, 154, 157, 161–2, 163, 165, 166, 169, 170, 171, 173; electromagnetism, attempt to unify with 104; general relativity, unifying with theory of 7, 168, 219, 220; inflation and 229; language and 408–9; observation and 148–58, 168–70, 173, 178; particle nature of light and 88, 134–49; quantum entanglement 172; quantum fluctuations 182, 183, 228–9, 231, 288; quantum gravity 7, 168, 183; quantum microscopes 79; quantum tunnelling 165–6; quantum Zeno effect 150–1; radioactive uranium emission of radiation and 131–3, 143–4, 150, 151, 158, 159, 160, 166–7, 171–2, 173–4, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 183; repeating an experiment in 408; reversible laws of 284–5, 355; trusting the maths of 165; uncertainty principle and 133, 159–60, 162–3, 164, 165, 166–7, 168–70, 180, 181–3, 243, 266, 274–5, 288, 290; wave function 5, 146–9, 153–8, 165, 169, 173, 177, 178–9, 402 quark 3, 79, 116–21, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 175, 187, 298, 335, 407 quidditism 298 Rabi, Isidor 105 radioactivity 98–9, 107, 131, 132–3, 171, 173 Ramón y Cajal, Santiago 311–13, 348 randomness 70, 131, 133, 143–4, 153, 154–5, 171–2, 174, 230, 338 redshift 214–16, 220, 222, 224 Rees, Martin 418 Reiss, Diana 318 relativity, theories of 5, 6, 7–8, 12, 72, 105, 115, 141, 143, 168, 219, 220, 248, 252, 253–72, 273, 275, 277, 278, 281, 282, 285, 288, 291, 293, 296, 299, 359 religion 13–15, 68–71, 174–8, 179, 181, 235–40, 320, 348–9, 355, 393, 399, 401–2, 410, 411 see also God rhetoric, art of 368, 369 Riemann, Bernhard 261–2, 376, 377, 388, 402, 404, 413, 420 Robertson, Howard 163 Robinson, Julia 401 Rømer, Ole 199 Rosen, Nathan 172 Rosetta Stone 113 Rovelli, Carlo 300 Royal Academy of Sciences, Paris 199 Royal Institution Christmas Lectures 2–3 Royal Observatory 197 Royal Society 90, 326–7 Royal Swedish Academy of Science 39 Rufus of Ephesus 306 Rumsfeld, Donald 11 Rushdie, Salman: Midnight’s Children 247, 264 Russell, Bertrand 380–1, 412 Rutherford, Ernest 98, 99, 100, 119, 120 Saint Augustine 22, 296; City of God 391; Confessions 249 Sartre, Jean-Paul 337 Saturn 63, 64, 190, 196 Schopenhauer, Arthur 77, 78 Schrödinger, Erwin 5, 131, 132, 146, 154, 177 Schumacher, Heinrich Christian 392 science/scientific discovery: constantly evolving nature of 364–6; dominance of 1–2; exponential growth in 3–4, 8–9; laws of nature, search for ultimate 9; mathematics vs. 364–6; only appears to describe reality 418; questions that can never be resolved 9–13, 295, 347, 349–50, 353, 355–60, 405–6, 407–20; success rate of and production of true knowledge 416 Scientific American 2 Searle, John 338–9 self-recognition test, animals and 317–19 sense of self 317, 319–20, 331, 342, 343 senses: limit of 416–18; out-of-body experiences and 328–30, 416 Serber, Robert 117, 119 S4 (group of symmetries) 112 Shakespeare, William 219, 399 Shapely, Harlow 204 Shull, Clifford 165 Sigma baryons 107, 108, 109, 110, 115, 119 singularity 8–9, 219, 220, 238, 248, 278–82, 283, 284, 289, 290, 293, 294 61 Cygni 201, 202 sleep, consciousness and 315–16, 339–41, 342, 343, 344, 346 Small Magellanic Cloud 203 Socrates 412 space-time: black holes and 276–8, 283, 284, 285; God and 296–8; origin of concept 262–4; shape of 264–72, 275–8, 283; singularities and 283, 284, 293 special relativity, theory of 105, 141, 143, 248, 252, 253–64, 275, 296, 359 Sphinx observatory, Switzerland 213–14, 223 square number 392, 394 ‘squaring the circle’ 373–4 Stanford University 229, 401; Stanford Linear Accelerator Center 119 stars: Andromeda nebula 203, 204; Big Bang and 220; black holes and 274–7, 284; chemical composition of 10; collapse of 222, 275, 276, 277; Comte predicts we will never know constituents of 10, 202, 243, 347, 409; creation of a 274; curved space-time and 271–2; death of 222; expanding universe and 214–18, 220, 222–3, 224, 227; fusion of atoms in 274; general theory of relativity and 271, 272; luminous matter and 238; measuring distance/brightness of 202–5, 214–16; paper star globe 187–8, 190, 195, 200, 201, 225, 227, 244; red giant 63; redshift and 214–16, 220, 222, 224; shape of universe and 187–8, 208–9; size of universe/infinity and 187–8, 190–2, 202–7; speed of light and 253; stellar parallax 200–1, 202; supernova and 222; white dwarf 274–5 see also under individual star and constellation name stellar parallax 200–1, 202 Stoppard, Tom: Arcadia 19, 53 strange quark 117, 118, 119, 120, 121 strangeness 108, 109–11, 115–16 string theory 127, 168, 234 strong nuclear force 107, 108, 109–10 Strzalko, Jaroslaw 67 SU(3) (symmetrical object) 5, 111–12, 113, 114, 115, 116–17, 120, 125 SU(6) (symmetrical object) 121 Sun 188, 189, 190, 193, 196, 199–200, 201, 203, 275; black holes and 276, 277; as centre of universe 193, 227, 413; Cepheid stars and 203, 204; chemical composition of 10; creation of 274; curved space-time and 271; distance of Earth from 193–5, 201, 206; entropy and 287; gravity and creation of 274; mass of 34, 275; measuring time and 251, 253, 271; pattern of movement 20, 188, 227, 251, 253, 271; planets orbit of 176, 193–6, 227; red giant, evolution into 63; size of 189; speed of light and 198, 199–200, 201, 253; time measurement and 251, 253, 271; trigonometry and 189, 201 supernova 222, 275 symmetry 103, 110, 111–17, 120, 121, 125, 269–72, 273, 327, 342, 344, 374, 376 synesthesia 325–6 Taleb, Nassim: The Black Swan 12 Tartaglia, Niccolò Fontana 25 technology: brain studies and 306, 314, 329–30, 336; singularity 281; rate of change/growth in 8, 281 Tegmark, Max 297–8 telescope: Andromeda and 204; discovery of new planets and 3, 195–8; invention of 189, 190, 192, 193–5, 200, 296, 305, 416; measuring distance of planets and 193–5; name 193; neural 305, 314–16, 323; paper 322–3, 325–6, 328; speed of light and 198–9, 200; stellar parallax and 201; trigonometry as 189–90 telomeres 5 Templeton Foundation 236, 237 Templeton, Sir John/Templeton prize 235–6, 237 Thales of Miletus 366–7 ‘The Great Debate’, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, 1920 203–4 theory of abduction 233 Theory of Everything 9, 34–5 thermal time hypothesis 300 thermodynamics, second law of 285–6, 287, 290, 293 Thomson, J. J. 95, 96, 97, 98, 104–5, 140 Thorne, Kip 277, 289, 290 time: aeon concept and 292–6; asymmetrical twins and 269–70; atomic clock 123, 252, 254, 269; before Big Bang, existence of 7, 9, 248–9, 262–7, 284, 290, 291–6, 407; black holes and see black holes; calculus and 30, 31; day, measuring the 251; Einstein and see Einstein, Albert; emergence and 331; entropy and 286–7; equivalence and 267–9; existence of 7, 299–300; future of universe and 291–3; general relativity and 5, 6, 7–8, 115, 143, 168, 219, 220, 248, 265, 267–72, 273, 277, 278, 281–2, 285, 288, 293; God and space-time 296–8; Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and 181–3; incompleteness of knowledge, as an expression of 299–300; infinite 192; Leibniz belief in relative nature of 252–3; muon decay and 258–9; nature of 247–72, 273; Newton’s belief in absolute nature of 252, 253, 262; relative nature of 252–64; second, measuring the 251–2; shape of 264–72, 275–8, 283; space-time, origin of concept 262–4 see also space-time; special relativity and 105, 141, 143, 248, 252, 253–64, 268, 269–72, 275, 281–2, 296, 359; speed of light and 72, 105, 176, 198–200, 217, 224, 228, 253–8, 259, 260–1, 262–3, 264, 268, 269–72, 275, 281–2, 291; thermal time hypothesis 300; time and space, infinite divisibility of 87, 252–4, 261–4; what is?

The Age of AI: And Our Human Future

by

Henry A Kissinger

,

Eric Schmidt

and

Daniel Huttenlocher

Published 2 Nov 2021

The conviction that what we see reflects reality—and that we can fully comprehend at least aspects of this reality using discipline and reason—inspired the Greek philosophers and their heirs to great achievements. Pythagoras and his disciples explored the connection between mathematics and the inner harmonies of nature, elevating this pursuit to an esoteric spiritual doctrine. Thales of Miletus established a method of inquiry comparable to the modern scientific method, ultimately inspiring early modern scientific pioneers. Aristotle’s sweeping classification of knowledge, Ptolemy’s pioneering geography, and Lucretius’s On the Nature of Things spoke to an essential confidence in the human mind’s capacity to discover and understand at least substantial aspects of the world.

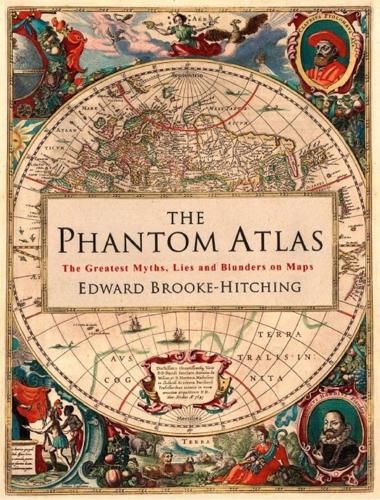

The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps

by

Edward Brooke-Hitching

Published 3 Nov 2016

Some think it is spherical, others that it is flat and drum-shaped. For evidence they bring the fact that, as the sun rises and sets, the part concealed by the earth shows a straight and not a curved edge . . . Others say the earth rests upon water. This, indeed, is the oldest theory that has been preserved, and is attributed to Thales of Miletus. It was supposed to stay still because it floated like wood and other similar substances, which are so constituted as to rest upon water but not upon air. He then forms his own conclusion in II, 14: ‘Our observations of the stars make it evident . . . that the earth is circular in shape, but also that it is a sphere of no great size: for otherwise the effect of so slight a change of place would not be quickly apparent.’

Coming of Age in the Milky Way

by

Timothy Ferris

Published 30 Jun 1988

Living as they did with the sea at their feet and the mountains at their backs, they appreciated that waves erode the land, and were acquainted with the strange fact that seashells and fossils of marine creatures may be found on mountaintops far above sea level.* At least two of the realizations essential to the modern science of geology—that mountains can be thrust up from what was once a seabed, and that they can be worn down by wind and water—were mentioned as early as the sixth century B.C., by Thales of Miletus and Xenophanes of Colophon. But they tended to regard these transformations as mere details, limited to the current cycle of a cosmos that was in the long run eternal and unchanging. “There is necessarily some change in the whole world,” wrote Aristotle, “but not in the way of coming into existence or perishing, for the universe is permanent.”3 For science to begin to assess the antiquity of the earth and the wider universe—to locate humanity’s place in the depths of the past as it was to chart our location in cosmic space—it had first to break the closed circle of cyclical time and to replace it with a linear time that, though long, had a definable beginning and a finite duration.

…

The Mayans, obsessed with ball playing, conjectured that their creator was transformed into a solar kickball each time the planet Venus disappeared behind the sun. Tahitian fisherman told of an angler god who tugged their islands from the ocean floor; the Japanese sword-wielders formed their islands from drops of blood dripping from a cosmic blade. To the logic-loving Greeks, creation was elemental: For Thales of Miletus, the universe originally was water; for Anaximenes (also of Miletus), air; for Heraclitus, fire. In the fecund Hawaiian Islands, genesis was managed by a team of spirits skilled in embryology and child development. African bushmen huddled around a fire watched the sparks fly upward into the night sky and recited these words: The girl arose; she put her hands into the wood ashes; she threw up the wood ashes into the sky.

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton

by

Colin Read

Published 16 Jul 2012