The Chicago School

description: education organization in Los Angeles, United States

191 results

The Politics of Bitcoin: Software as Right-Wing Extremism

by David Golumbia · 25 Sep 2016 · 87pp · 25,823 words

its promulgation in JBS and other right-wing propaganda, but it was a theory developed and cultivated by the architects of neoliberal doctrine associated with the Chicago School of economics and the Mont Pelerin Society. Chief among these was MPS founding member and early 1970s president and University of Chicago economics professor Milton

The Extreme Centre: A Warning

by Tariq Ali · 22 Jan 2015 · 160pp · 46,449 words

when the Soviet Union self-destructed and was dismantled, new problems arose, partially political, but mostly social and economic. With the victory of Hayek and the Chicago School came the birth of what became known as neoliberalism. Accordingly, the European Union began to determine the social and economic policies of its member states

The Great Tax Robbery: How Britain Became a Tax Haven for Fat Cats and Big Business

by Richard Brooks · 2 Jan 2014 · 301pp · 88,082 words

the era of late-twentieth century economic liberalization was dawning. From 1979 Margaret Thatcher’s government began implementing the monetarism and financial deregulation advocated by the ‘Chicago school’ of economic theory and championed here by the new prime minister’s favoured think tanks such as the Institute for Economic Affairs. Her first and

This Is Not Normal: The Collapse of Liberal Britain

by William Davies · 28 Sep 2020 · 210pp · 65,833 words

public choice theory of the Virginia School aimed to represent democracy and public office in terms of the calculated self-interest of those involved.10 The Chicago School did the same in relation to law and economics. This amounts to what I’ve termed the ‘disenchantment of politics by economics’.11 It also

The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians

by Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar · 14 Oct 2024 · 175pp · 46,192 words

hold in the United States, which heavily influenced Canada’s competition policy. Driven by conservative legal scholars like Robert Bork at The University of Chicago, the Chicago School claimed that competition policy should be solely aimed at economic efficiency, and that large firms were best positioned to allocate resources in the economy. This

…

lowering prices for consumers during a period of high inflation. Competition policy was also heavily influenced during this time by the outgrowth of neoclassical economics. The Chicago School claimed that antitrust policy could become more neutral and scientific by elevating the role of economists in the process of crafting and deciding antitrust cases

Nine Crises: Fifty Years of Covering the British Economy From Devaluation to Brexit

by William Keegan · 24 Jan 2019 · 309pp · 85,584 words

of inflation was essentially a matter of controlling the money supply. In its modern version it was associated with the American economist Milton Friedman, of the Chicago School. We Keynesians always held the view that controlling inflation was much more complicated than Friedman and his disciples maintained. There was a great debate in

No Such Thing as Society

by Andy McSmith · 19 Nov 2010 · 613pp · 151,140 words

background, it is not difficult to see why some Conservative radicals were drawn to the new ideology called ‘monetarism’. Milton Friedman and other members of the ‘Chicago School’ argued that governments should not have prices or incomes policies, which only interfered with the free market. A government’s first and almost its only

Capitalism: A Ghost Story

by Arundhati Roy · 5 May 2014 · 91pp · 26,009 words

Pacific Studies Center and the North American Congress on Latin America (Palo Alto, CA: Ramparts, 1975), 93–116. 45. Juan Gabriel Valdés, Pinochet’s Economists: The Chicago School of Economics in Chile (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995). 46. Rajander Singh Negi, “Magsaysay Award: Asian Nobel, Not So Noble,” Economic and Political Weekly

The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth Is Unattainable and the Global Economy Is in Peril

by Satyajit Das · 9 Feb 2016 · 327pp · 90,542 words

of Western Affluence, Yale University Press, 2013. Graeme Maxton, The End of Progress: How Modern Economics Has Failed Us, John Wiley, 2011. Johan van Overtveldt, The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago Assembled the Thinkers Who Revolutionised Economics and Business, Agate Books, 2007. John Quiggin, Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk

Accelerando

by Stross, Charles · 22 Jan 2005 · 489pp · 148,885 words

-all of market economics, solving the calculation problem. Just because he can, because hacking economics is fun, and he wants to hear the screams from the Chicago School. Try as he may, Manfred can't see anything in the press release that is at all unusual. It's just the sort of thing

…

of upper level to the underside of the roof. "Human beings aren't rational," he calls over his shoulder. "That was the big mistake of the Chicago School economists, neoliberals to a man, and of my predecessors, too. If human behavior was logical, there would be no gambling, hmm? The house always wins

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by Anu Bradford · 25 Sep 2023 · 898pp · 236,779 words

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

A Brief History of Neoliberalism

by David Harvey · 2 Jan 1995 · 318pp · 85,824 words

The System: Who Owns the Internet, and How It Owns Us

by James Ball · 19 Aug 2020 · 268pp · 76,702 words

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by Meghnad Desai · 15 Feb 2015 · 270pp · 73,485 words

Zero-Sum Future: American Power in an Age of Anxiety

by Gideon Rachman · 1 Feb 2011 · 391pp · 102,301 words

#Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media

by Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Mar 2017 · 437pp · 105,934 words

Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa

by Dambisa Moyo · 17 Mar 2009 · 225pp · 61,388 words

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by Ian Kershaw · 29 Aug 2018 · 736pp · 233,366 words

The End of Growth

by Jeff Rubin · 2 Sep 2013 · 262pp · 83,548 words

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 1 Jan 2004 · 475pp · 149,310 words

How to Fix Copyright

by William Patry · 3 Jan 2012 · 336pp · 90,749 words

Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself

by Peter Fleming · 14 Jun 2015 · 320pp · 86,372 words

Moscow, December 25th, 1991

by Conor O'Clery · 31 Jul 2011 · 449pp · 127,440 words

The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991

by Robert Service · 7 Oct 2015

Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side

by Howard Marks · 30 Sep 2018 · 302pp · 84,428 words

Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth

by Juliet B. Schor · 12 May 2010 · 309pp · 78,361 words

The Nanny State Made Me: A Story of Britain and How to Save It

by Stuart Maconie · 5 Mar 2020 · 300pp · 106,520 words

The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health--And How We Must Adapt

by Sinan Aral · 14 Sep 2020 · 475pp · 134,707 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by John Lanchester · 5 Oct 2014 · 261pp · 86,905 words

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams · 1 Oct 2015 · 357pp · 95,986 words

Pity the Billionaire: The Unexpected Resurgence of the American Right

by Thomas Frank · 16 Aug 2011 · 261pp · 64,977 words

"They Take Our Jobs!": And 20 Other Myths About Immigration

by Aviva Chomsky · 23 Apr 2018 · 219pp · 62,816 words

The Internet Trap: How the Digital Economy Builds Monopolies and Undermines Democracy

by Matthew Hindman · 24 Sep 2018

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

by Elizabeth Kolbert · 15 Mar 2021 · 221pp · 59,755 words

American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers

by Nancy Jo Sales · 23 Feb 2016 · 487pp · 147,238 words

Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

by R. Christopher Whalen · 7 Dec 2010 · 488pp · 144,145 words

Work in the Future The Automation Revolution-Palgrave MacMillan (2019)

by Robert Skidelsky Nan Craig · 15 Mar 2020

Data and the City

by Rob Kitchin,Tracey P. Lauriault,Gavin McArdle · 2 Aug 2017

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen

by James Suzman · 10 Jul 2017

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The Default Line: The Inside Story of People, Banks and Entire Nations on the Edge

by Faisal Islam · 28 Aug 2013 · 475pp · 155,554 words

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by Ann Pettifor · 27 Mar 2017 · 182pp · 53,802 words

A Crack in the Edge of the World

by Simon Winchester · 9 Oct 2006 · 482pp · 147,281 words

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

by Lawrence Lessig · 14 Jul 2001 · 494pp · 142,285 words

The Making of Global Capitalism

by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin · 8 Oct 2012 · 823pp · 206,070 words

From Bauhaus to Our House

by Tom Wolfe · 2 Jan 1981 · 98pp · 29,610 words

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy--And How to Make Them Work for You

by Sangeet Paul Choudary, Marshall W. van Alstyne and Geoffrey G. Parker · 27 Mar 2016 · 421pp · 110,406 words

The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets

by Thomas Philippon · 29 Oct 2019 · 401pp · 109,892 words

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon · 2 Nov 2009 · 918pp · 260,504 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World's Tallest Skyscrapers

by Jason M. Barr · 13 May 2024 · 292pp · 107,998 words

Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be

by Diane Coyle · 11 Oct 2021 · 305pp · 75,697 words

The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community

by David C. Korten · 1 Jan 2001

Virtual Competition

by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke · 30 Nov 2016

Economists and the Powerful

by Norbert Haring, Norbert H. Ring and Niall Douglas · 30 Sep 2012 · 261pp · 103,244 words

Volt Rush: The Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green

by Henry Sanderson · 12 Sep 2022 · 292pp · 87,720 words

The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Sep 2019

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President

by Bandy X. Lee · 2 Oct 2017 · 369pp · 105,819 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

by Jerry Kaplan · 3 Aug 2015 · 237pp · 64,411 words

The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 15 Mar 2015 · 409pp · 125,611 words

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by Roger McNamee · 1 Jan 2019 · 382pp · 105,819 words

Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (And How to Take Advantage of It)

by William Poundstone · 1 Jan 2010 · 519pp · 104,396 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by Jonathan Taplin · 17 Apr 2017 · 222pp · 70,132 words

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

by Benjamin H. Bratton · 19 Feb 2016 · 903pp · 235,753 words

The Trouble With Billionaires

by Linda McQuaig · 1 May 2013 · 261pp · 81,802 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

by Anand Giridharadas · 27 Aug 2018 · 296pp · 98,018 words

On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World

by Timothy Cresswell · 21 May 2006

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by Evgeny Morozov · 15 Nov 2013 · 606pp · 157,120 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America’s Overdose Crisis

by Beth Macy · 15 Aug 2022 · 389pp · 111,372 words

Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and How They Broke Capitalism

by Richard Brooks · 23 Apr 2018 · 398pp · 105,917 words

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by Branko Milanovic · 9 Oct 2023

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by Jason Hickel · 3 May 2017 · 332pp · 106,197 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World

by J. Doyne Farmer · 24 Apr 2024 · 406pp · 114,438 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by Rana Foroohar · 5 Nov 2019 · 380pp · 109,724 words

Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy

by Quinn Slobodian · 4 Apr 2023 · 360pp · 107,124 words

Chaos Kings: How Wall Street Traders Make Billions in the New Age of Crisis

by Scott Patterson · 5 Jun 2023 · 289pp · 95,046 words

Who Stole the American Dream?

by Hedrick Smith · 10 Sep 2012 · 598pp · 172,137 words

The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age

by Tim Wu · 14 Jun 2018 · 128pp · 38,847 words

The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

by Tim Wu · 14 May 2016 · 515pp · 143,055 words

There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century

by Fiona Hill · 4 Oct 2021 · 569pp · 165,510 words

Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2009 · 471pp · 97,152 words

The Quants

by Scott Patterson · 2 Feb 2010 · 374pp · 114,600 words

The Cigarette: A Political History

by Sarah Milov · 1 Oct 2019

Arrival City

by Doug Saunders · 22 Mar 2011 · 366pp · 117,875 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by Costas Lapavitsas · 14 Aug 2013 · 554pp · 158,687 words

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman · 24 Oct 2011 · 654pp · 191,864 words

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by Guy Standing · 13 Jul 2016 · 443pp · 98,113 words

Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago

by Eric Klinenberg · 11 Jul 2002 · 440pp · 128,813 words

Cities Are Good for You: The Genius of the Metropolis

by Leo Hollis · 31 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 118,314 words

Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century

by Christian Caryl · 30 Oct 2012 · 780pp · 168,782 words

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by Paul Tucker · 21 Apr 2018 · 920pp · 233,102 words

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by John Kay · 24 May 2004 · 436pp · 76 words

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Stacy Mitchell

by Big-Box Swindle The True Cost of Mega-Retailers and the Fight for America's Independent Businesses (2006)

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design

by Matthew Carmona, Tim Heath, Steve Tiesdell and Taner Oc · 15 Feb 2010 · 1,233pp · 239,800 words

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Chokepoint Capitalism

by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow · 26 Sep 2022 · 396pp · 113,613 words

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by Phil Thornton · 7 May 2014

Data Action: Using Data for Public Good

by Sarah Williams · 14 Sep 2020

Owning the Sun

by Alexander Zaitchik · 7 Jan 2022 · 341pp · 98,954 words

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by Gary Gerstle · 14 Oct 2022 · 655pp · 156,367 words

Making It in America: The Almost Impossible Quest to Manufacture in the U.S.A. (And How It Got That Way)

by Rachel Slade · 9 Jan 2024 · 392pp · 106,044 words

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

by J. Bradford Delong · 6 Apr 2020 · 593pp · 183,240 words

Globalists

by Quinn Slobodian · 16 Mar 2018 · 451pp · 142,662 words

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City

by Richard Sennett · 9 Apr 2018

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 14 Sep 2017 · 520pp · 153,517 words

The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 7 May 2024 · 470pp · 158,007 words

Extreme Economies: Survival, Failure, Future – Lessons From the World’s Limits

by Richard Davies · 4 Sep 2019 · 412pp · 128,042 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History

by Diana B. Henriques · 18 Sep 2017 · 526pp · 144,019 words

The Vanishing Neighbor: The Transformation of American Community

by Marc J. Dunkelman · 3 Aug 2014 · 327pp · 88,121 words

Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right

by Jennifer Burns · 18 Oct 2009 · 495pp · 144,101 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being

by William Davies · 11 May 2015 · 317pp · 87,566 words

Free Market Missionaries: The Corporate Manipulation of Community Values

by Sharon Beder · 30 Sep 2006 · 273pp · 34,920 words

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 22 Oct 2018 · 402pp · 126,835 words

The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

by David Callahan · 1 Jan 2004 · 452pp · 110,488 words

Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution

by Wendy Brown · 6 Feb 2015

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by Vito Tanzi · 28 Dec 2017

The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett · 1 Jan 2009 · 309pp · 86,909 words

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 Apr 2005 · 339pp · 95,988 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City

by Alan Ehrenhalt · 23 Apr 2012 · 281pp · 86,657 words

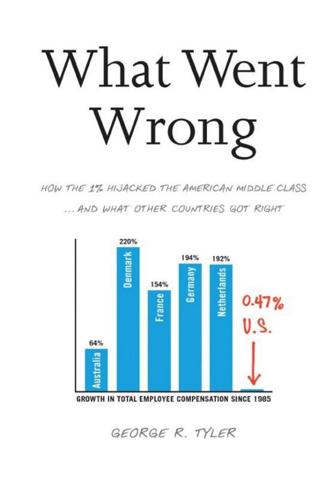

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JPMorgan Chase

by Duff McDonald · 5 Oct 2009 · 419pp · 130,627 words

Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris

by Richard Kluger · 1 Jan 1996 · 1,157pp · 379,558 words

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

Aerotropolis

by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay · 2 Jan 2009 · 603pp · 182,781 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

The Physics of Wall Street: A Brief History of Predicting the Unpredictable

by James Owen Weatherall · 2 Jan 2013 · 338pp · 106,936 words

The Origins of the Urban Crisis

by Sugrue, Thomas J.

Multicultural Cities: Toronto, New York, and Los Angeles

by Mohammed Abdul Qadeer · 10 Mar 2016

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by Richard Florida · 9 May 2016 · 356pp · 91,157 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

It's Better Than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear

by Gregg Easterbrook · 20 Feb 2018 · 424pp · 119,679 words

Once the American Dream: Inner-Ring Suburbs of the Metropolitan United States

by Bernadette Hanlon · 18 Dec 2009

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics

by Nicholas Wapshott · 10 Oct 2011 · 494pp · 132,975 words

Economic Dignity

by Gene Sperling · 14 Sep 2020 · 667pp · 149,811 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton

by Colin Read · 16 Jul 2012 · 206pp · 70,924 words

From Peoples into Nations

by John Connelly · 11 Nov 2019

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

by Matthew Desmond · 1 Mar 2016 · 444pp · 138,781 words

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right

by Jane Mayer · 19 Jan 2016 · 558pp · 168,179 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

Class Warfare: Inside the Fight to Fix America's Schools

by Steven Brill · 15 Aug 2011 · 559pp · 161,035 words

Milton Friedman: A Biography

by Lanny Ebenstein · 23 Jan 2007 · 298pp · 95,668 words

1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die, Updated Ed.

by Patricia Schultz · 13 May 2007 · 2,323pp · 550,739 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1997 · 1,106pp · 335,322 words

USA Travel Guide

by Lonely, Planet

No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age

by Jane F. McAlevey · 14 Apr 2016 · 423pp · 92,798 words

When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor

by William Julius Wilson · 1 Jan 1996 · 399pp · 116,828 words

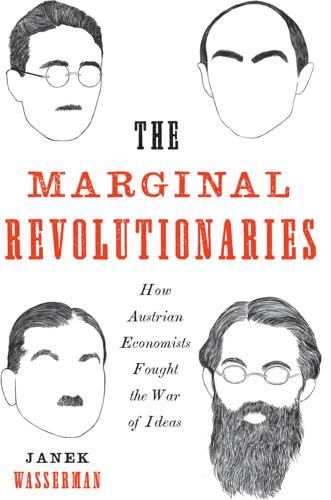

The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas

by Janek Wasserman · 23 Sep 2019 · 470pp · 130,269 words