Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World

by Naomi Klein · 11 Sep 2023

deploying it as an easy scapegoat for their failures. Nothing was ever their responsibility; it was always the fault of the “deep state.” In The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, Adam Smith wrote, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the

…

by leftists in Turkey: Ryan Gingeras, “How the Deep State Came to America,” War on the Rocks, February 4, 2019. “People of the same trade”: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776; repr. London: David Campbell Publishers, 1991), 116. “the ruling class showing class solidarity”: Mark Fisher, “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” Open Democracy, November 24, 2013

…

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake Sinclair, Murray Singh, Lilly Sister Outsider (Lorde) 60 Minutes Slate slavery “slavery forever” video Slobodian, Quinn smallpox Smalls, Chris smart cities Smith, Adam Smith, Zadie Snowden, Edward social credit systems Social Democrats socialism; Jewish attraction to social media; avatars on; content moderators and; Covid and; digital doubles on; enclosure

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design

by Charles Montgomery · 12 Nov 2013 · 432pp · 124,635 words

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York], © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ) In his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Bentham’s contemporary Adam Smith warned that it was a deception to believe that wealth and comfort alone would bring happiness. But this didn’t stop his followers or

…

the average income mark. After that, each extra dollar delivers proportionately less satisfaction. If money isn’t everything, what is the full recipe for happiness? Adam Smith’s followers in classical economics have never produced a plausible answer, but the surveys offer a few. People who are well educated rate their happiness

…

course this is what philosophers and spiritual leaders have been saying all along. For all the weight that proponents of classical economics place on selfishness, Adam Smith himself grasped the duality of human need. In his other great treatise, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith argued that human conscience comes from social

…

is a fantastically complex organism that can be thrown into an unhealthy imbalance by attempts to simplify it in form or function. In Cities and the Wealth of Nations she warned specifically about the tendency for designers and planners to overscale: the larger an organism or economy, the more unstable it would become in

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

, the issues and analytical principles are more universal. The dominant view in economics concerning the role of government has shifted over time. In The Wealth of Nations (published in 1776), Adam Smith was advocating a greater role for market exchange because there were then many government restrictions on activity, favoring established interests, at a time when

…

the benchmark of a competitive market as the way to think about government and market interaction. Even so, there has been considerable debate ever since Adam Smith as to the shape and scope of public policies. The next chapter looks in more detail at the government-market relationship and in particular the

…

for improving social welfare. The Tragedy of the Commons Garrett Hardin’s 1968 Science article on the tragedy of the commons was profoundly influential. Where Adam Smith had painted a picture of isolated, self-interested individual choices combining to give desirable social outcomes, Hardin argued the opposite: that individually rational choices involved

…

the role of financial versus social or civic-minded incentives, referred to as intrinsic motivation. The importance of intrinsic motivation is not new in economics. Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments emphasized the importance of non-financial considerations, although modern mainstream economics has tended to ignore it and assume financial motivations

…

such as the Amazon basin. The industry supported those concerned about the environmental and societal impacts of logging in order to reduce competition from imports.*** * Adam Smith and Bruce Yandle (2014), Bootleggers & Baptists: How Economic Forces and Moral Persuasion Interact to Shape Regulatory Politics, Cato Institute. ** Jeffrey Miron (1999), “Violence and the

…

rather than boring maintenance. User fees also help guard against white elephant projects as the contractor will have an incentive to respond to likely demand. Adam Smith made this point about infrastructure: “When high roads are made and supported by the commerce that is carried on by means of them, they can

…

Warhol, Andy, 162 warranties, 67, 74 Washington, D.C., 5 water supply, 22, 91, 104, 116, 123, 125, 143–44, 146–47 weak ties, 157 The Wealth of Nations (Smith), 18, 280 WeChat, 91 weighted average cost of capital, 310 weights and measures, 45, 63, 65 welfare economics, 8, 9, 15–16, 36; assumptions

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

one is to serve a community with only a handful of women of childbearing age, but it makes more sense if there are hundreds—as Adam Smith famously wrote, “the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market.” As the community grows larger, therefore, we can call the professional

…

craftsmen who were unwilling to put up with the guild’s anticompetitive rules moved to suburban and rural areas, outside the guild’s reach.25 Adam Smith wrote, “If you would have your work tolerably executed, it must be done in the suburbs where the workmen, having no exclusive privileges, have nothing

…

philosophers did not explain what they would advocate if market participants tried to subvert market competition with the aid of the state—a development that Adam Smith worried about—or shut it down themselves by cartelizing the market. Nevertheless, as a blunt theoretical argument with which to bludgeon the remaining anticompetitive vestiges

…

and preserving opportunity for the many. Let us now elaborate. FREEING THE MARKETS In his book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, Adam Smith argued that by producing for the market and maximizing his own profits, the manufacturer maximized the size of the public pie, and thus

…

or even the self-indulgence of the rich, it emanated from restraints on competition and the resulting distorted prices and quantities. Seen in this light, Adam Smith was pro-market, not pro-business. Indeed, he was no fan of the businessmen of his time because of their cartelizing tendencies. In arguing against

…

interest of any individual, or small number of individuals to erect and maintain.”6 A PHILOSOPHY FOR THE MARKET It was a short step from Adam Smith’s work to the manifesto for individualism and the free market, On Liberty, written by British economist John Stuart Mill. It was published in 1859

…

the perfect competition of textbooks, with producers competing with one another to give the consumer the best deal, but this did not last. For as Adam Smith recognized, competition drove down profits, making any producer’s life greatly uncertain. The inexorable political tendency of a free, unfettered, unregulated market was for the

…

society. Among the extraordinarily successful institutions he founded are the University of Chicago, where I teach. His dismal view of competition had less resonance with Adam Smith, though, than with another insightful economist, Karl Marx. THE MARXIST RESPONSE The Industrial Revolution that started in Britain in the late eighteenth century created tremendous

…

inefficiencies of centralized monopolistic production slowed growth. Without competition to show up inefficiencies and penalize the merely greedy, and without the decentralized decision making that Adam Smith and later Friedrich Hayek thought was essential to make best use of local information, centralized monopolies eventually ended up as a sclerotic mess, as exemplified

…

inheritances; more than forty states had inheritance taxes in place by the 1910s.46 Each of these ways of containing big business has limitations. As Adam Smith recognized, regulatory bodies often become subservient to the powerful among the regulated—in which case, paradoxically, regulations become a tool with which to protect the

…

performance may also have motivated firms to seek the easy route to profits; shutting down the competition. In a sense, this is no different from Adam Smith’s frequently articulated concerns about anticompetitive instincts of corporations, but there is a greater urgency about this threat today. As new technology and global markets

…

European Miracle, 3rd ed. (1981; repr., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 98–102. 25. Jones, The European Miracle, 98. 26. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976). 27. Jones, European Miracle, 114; Eric Evans, The Forging of the Modern State: Early Industrial

…

. Quoted in Edward Cheyney, An Introduction to the Industrial and Social History of England (New York: Macmillan, 1916), chapter 8. 2. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 90. Page numbers are from the Kindle edition of this text. 3. Smith, Wealth of

…

, 143–44, 173, 175, 177–88, 395 trade and, 143–44, 173, 181–88 inheritance, 37, 45, 105 Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, An (Smith), 80 intellectual property, 73, 183, 278, 351, 362–63, 382–84 patents, 204–6, 362, 382–84 International Monetary Fund (IMF), xxvi, 146

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

and through the recent growth of economics itself as a professional and specifically mathematical discipline, has been to highlight the ‘economic’ Smith, the Smith of The Wealth of Nations. This has served to sideline what might be called the ‘political’ Smith, the Smith who examines how power, property and government co-evolve and

…

project. The fad for selective interpretation has even, perhaps especially, included economists themselves. In the words of the Chicago School economist Jacob Viner on The Wealth of Nations, ‘Traces of every conceivable sort of doctrine are to be found in that most catholic book, and an economist must have peculiar theories indeed who

…

The Wealth of Nations to support his special purposes.’ So it has proven. One example of this tendency will suffice, and from Viner’s most famous student no less. In a famous article of 1977 for Challenge magazine, Milton Friedman, fresh from winning a Nobel Prize in the previous year, undertook to spell out ‘Adam Smith

…

with the benefit of hindsight, Adam Smith was unequivocal: ‘The Union was a measure from which infinite good has been derived to this country.’ This view was widely shared by the leading Scottish thinkers of the day. The benefits were not simply economic: as Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, ‘By the union with

…

to his hand. It was during this time that Smith laid the intellectual foundations for his mature thought, including The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. There is one other fascinating possibility, reflected in a plausible story from John Leslie, a mathematician whom Smith recruited forty years later to teach

…

communication anticipating his later stress on sympathy and mutual recognition, while the rhetoric and suasion here anticipate the disposition to ‘truck, barter and exchange’ of The Wealth of Nations. However, the central philosophical question, of what form a science of man could properly take, still remained. Smith’s answer comes in an essay

…

international trade, interest rates, competition, markets, trust, standing armies vs. militias, and the law of nations. All of these issues would be revisited in The Wealth of Nations. The Lectures on Jurisprudence thus serve as a crucial missing link in Smith’s work. Unpublished in his own time and little known even today

…

Physiocrats. This is a mistake, for though he learned from them, he was also pitiless in analysing their errors, notably in Book IV of The Wealth of Nations. The Physiocrats were agrarians: the central plank of their approach was the belief that only the agricultural sector generated surplus economic value, that merchants,

…

with me’ to London. He would not return till 1776, and then it would be, with The Wealth of Nations in his hand. CHAPTER 4 ‘YOU ARE SURELY TO REIGN ALONE ON THESE SUBJECTS’, 1773–1776 ADAM SMITH ARRIVED IN LONDON IN MAY 1773, MOVING INTO rooms in Suffolk Street, near the present National Gallery

…

those involved by lowering prices and generating markets for produce. This ‘agricultural system’ had its virtues, as Smith acknowledged: they included a recognition of ‘the wealth of nations as consisting, not in the unconsumable riches of money, but in the consumable goods annually produced by the labour of the society’, and an understanding

…

as a supporter of militias. But he is pragmatic, here as elsewhere, about the merits and demerits of the two forms of defence. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith’s realism comes through, in an analysis that reflects considerations both of history and of political economy. Yes, important historical precedents spoke against

…

by tax policy-makers ever since Adam Smith, and they retain their value today. FROM A STRICTLY COMMERCIAL PERSPECTIVE, SMITH FOUND HIMSELF eclipsed by his friend Edward Gibbon, whose The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published the previous month, sold out almost immediately. Nevertheless, The Wealth of Nations did well. William Strahan, who

…

seen, he took elaborate measures to preserve a particular presentation of his life and work for future generations. Secondly, while the later success of The Wealth of Nations has given Smith extraordinary fame, it has also had the effect of overshadowing his Theory of Moral Sentiments and other writings—some only relatively recently

…

institutional, developmental and behavioural economics, traces its lineage back to Smith. Politicians, academics and pub bores around the world have found the authority of The Wealth of Nations and the simplicity of its core ideas an irresistible combination, and routinely draw on them to dignify and adorn their own beliefs or arguments. The

…

of Moral Sentiments offers an evolutionary account of social and moral norms, mediated as with language by the operation of sympathy or fellow feeling. The Wealth of Nations focuses in part on one specific aspect of human interaction, market exchange, locates it within a historical transition from feudalism to commercial society and

…

a debate originated among German scholars over what came to be called Das Adam Smith Problem. Was there just one Adam Smith, with one overarching theory, or were there two: the Adam Smith of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and the very different Adam Smith of The Wealth of Nations? Isn’t the former work really about altruism and human goodness,

…

will become clear. MYTH 2: ADAM SMITH WAS AN ADVOCATE OF SELF-INTEREST Understanding the true relationship between these two great works is important not merely insofar as it reveals Smith’s overall view, but because it helps guard against the mistake of seeing The Wealth of Nations as his final word—as though he

…

the baker, the focus is in part on identifying and satisfying their interests, and on the mutual benefits of exchange. MYTH 3: ADAM SMITH WAS PRO-RICH The Wealth of Nations was published at a time when Scotland was in the early stages of one of the longest and most rapid periods of national economic

…

rights, maintaining the rule of law and providing an institutional context of trust and predictability within which markets may flourish. As he remarks in The Wealth of Nations, ‘Those laws and customs so favourable to the yeomanry have perhaps contributed more to the present grandeur of England than all their boasted regulations

…

through such things as poor communications, lack of security, economically irrational behaviour and asymmetries of information or power. Unlike many works of modern economics, The Wealth of Nations is packed with facts and historical material, and although Smith employs the ‘let us assume’ thought experiments characteristic of modern economics, his general instinct is

…

often today, state and market were viewed as interdependent: hardly surprising, perhaps, in an age of corporate towns, licensed markets and chartered companies. In The Wealth of Nations Smith made a series of great attacks against established injustice: against the petty regulations of parish councils and church wardens; against the laws of settlement

…

serious caveat to be entered here. Adam Smith would almost certainly have been astonished by many of the achievements of modern mainstream economics. He would have marvelled at its theoretical sophistication and explanatory power, and he would have been amused to see how far The Wealth of Nations had the unintended but largely beneficent consequence

…

men, though not to McKenzie. But a reader of the book could be forgiven for thinking that for Arrow and Hahn Adam Smith’s real genius lay not in what The Wealth of Nations—nor for that matter The Theory of Moral Sentiments, let alone his other writings—might have actually said, but in identifying

…

But this in turn raises a series of important questions. How does mainstream economics relate to the political economy of The Wealth of Nations? What happened to economics in the intervening two centuries? Was Adam Smith the creator of rational economic man? To answer these questions, we need to review the history briefly, before turning

…

student and a trenchant critic of Adam Smith, but at first sight the idea that Marxist economics derives in any way from Smith may seem absurd. Surely Marxism is the very antithesis of free markets? How can the doctrines of the Communist Manifesto owe anything to The Wealth of Nations? These issues are too large

…

The link with the Smithian picture of the spontaneous emergence of moral and economic order is evident. Arguably The Wealth of Nations is more Austrian than neoclassical in character. Indeed, in many ways mainstream economics gets Adam Smith exactly the wrong way round. It takes individuals as fixed and isolated vehicles for preferences, rather than as

…

of Adam Smith—of Smith as, in effect, a ‘neoliberal’ economist in embryo—is quite wrong. First, as we have seen, Smith did not originate the idea of economic man, and he was scathing about human greed. Indeed, far from adopting the modern paradigm of self-interested economic rationality, in The Wealth of Nations he

…

and developed global market economy. As we saw from his critique of François Quesnay and the Physiocrats, Adam Smith rejected the use of highly idealized and artificial assumptions in political economy. His focus in The Wealth of Nations is more concrete, more historical, more closely informed by data and more policy-oriented. He tends to

…

Adam Smith despised slavery and the slave trade, and he argued with enormous force that, far from resulting from natural liberty, both were abetted by mercantilism and monopoly. Britain banned the slave trade across the British Empire by Act of Parliament in 1807, and abolished slavery itself in 1833. But already when The Wealth of Nations

…

a further 133. The move towards free trade gave Adam Smith a kind of sanctified official status. But it had not always been so. Indeed, Walter Bagehot, legendary editor of the free-trade paper The Economist, remarked at the centenary of The Wealth of Nations in 1876 that ‘It is difficult for a modern

…

one which differed in strength between Britain and France. The political, financial and economic contrasts between the two countries are a key theme in The Wealth of Nations, and Smith was apparently quite familiar with the resistance of the regional French parlements to central authority, and the autocratic interventions from Versailles which impeded

…

a world yearning for genuine sources of intellectual authority, Adam Smith has been recruited to, or disparaged by, a vast range of different economic, political or social viewpoints. But he remains little read, and that little reading has tended to focus on The Wealth of Nations. The result, as we have seen, has been a

…

. The effect, ironically, is to return inquiry almost to its starting point. For in the work of Adam Smith, from the earliest essays to The Theory of Moral Sentiments, the Lectures on Jurisprudence and The Wealth of Nations itself, what we would call ‘culture’ is in several different aspects an absolutely central concern. Yes, much

…

to Adam Smith himself. Not to Smith the caricature one-note libertarian alternately celebrated by his partisans and denounced by his detractors, but to what Smith actually thought, across all his writings, from ethics to jurisprudence to political economy. Even among economists, few read beyond Books I and II of The Wealth of Nations, if

…

Burke: The First Conservative The Big Society: The Anatomy of the New Politics BIBLIOGRAPHY WORKS BY ADAM SMITH Correspondence of Adam Smith, ed. Ernest Campbell Mossner and Ian Simpson Ross, Liberty Fund 1987 An Early Draft of Part of The Wealth of Nations, in LJ Essays on Philosophical Subjects, ed. W. P. D. Wightman and J. C.

…

Bryce, Liberty Fund [1795] 1980 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, ed. R. H. Campbell

…

been silently corrected. Page numbers are included to hard-copy versions consulted. ABBREVIATIONS CAS: Correspondence of Adam Smith, ed. Ernest Campbell Mossner and Ian Simpson Ross, Liberty Fund 1987 ED: An Early Draft of Part of The Wealth of Nations, in LJ EPS: Essays on Philosophical Subjects, ed. W. P. D. Wightman and J. C.

…

Bryce, Liberty Fund [1795] 1980 LAS: Life of Adam Smith [by various authors] LJ: Lectures on Jurisprudence, ed. R. L. Meek, D.

…

Adam Smith, LL.D. to William Strahan, Esq., in David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, ed. Eugene F. Miller, Liberty Fund [1777] 1987 TMS: The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie, Liberty Fund [1759–90] 1982 WN: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

…

lecture: ‘What Adam Smith did was to give economics its shape… From one point of view the last two hundred years of economics have been little more than a vast “mopping up operation” in which economists have filled in the gaps, corrected the errors and refined the analysis of The Wealth of Nations’. Essays on

…

Economics and Economists, University of Chicago Press 1994, p. 78 CHAPTER 1: KIRKCALDY BOY, 1723–1746 For detailed citations supporting the facts of Adam Smith’s life, see in particular Ian Simpson Ross, LAS Gipsy encounter:

…

J. H. Hollander, ‘Adam Smith and James Anderson’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, May 1896, summarizes what is known of the relationship between the two men. Smith was evidently aware of Anderson’s criticism, but never addressed it in later editions of The Wealth of Nations Information and power asymmetries

…

: Deborah Boucoyannis, ‘The Equalizing Hand: Why Adam Smith Thought the Market Should Produce Wealth without Steep Inequality’, Perspectives on Politics, 11.4, December 2013 Government as interest

…

271 capitalism and, 325–326 changes in, 329–330 economic relationships in, 293–294 institutions in, 295 strong states of, 327 taxation and, 116–117 The Wealth of Nations on, 316 commercial system, of England, 114–115 commercialization society, 311–319 communication, 41–42, 334 companies, American, 280–282 comparative advantage, 199 compassion,

…

, 149, 174–176, 190–191, 325 British, 200 on markets, 243 mathematics in, 201, 204 Mill on, 208 rationality in, 203 Stewart on, 162 The Wealth of Nations on, 104, 119, 192 See also Illustrations of Political Economy (Martineau); On the Definition of Political Economy (Mill); Principles of Political Economy (Ricardo) political leadership

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by Meghnad Desai · 15 Feb 2015 · 270pp · 73,485 words

constraint would result in inflation. As to the question of what constituted wealth, the answer was to come from a fellow Scotsman and friend – Adam Smith. Determining the Wealth of Nations Adam Smith, a lifelong bachelor who lived with his mother and sister all his adult life, was a friend of David Hume. Smith was elected a Professor

…

with France, which lasted, on and off, from 1695 to 1815. In his celebrated book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, Adam Smith pointed out that it was the productivity of its workers which was the key to the prosperity of a nation and not the treasures

…

self-sufficiency model for nationalists. The complex voluntary cooperation which exists beneath the surface of our daily economic life was called the invisible hand by Adam Smith. It is the interdependence of people far-flung and unknown to each other which is the most difficult thing to grasp about economics. It is

…

, that there are jobs to go to for most of us and that the same will be the case tomorrow. It is as if, as Adam Smith said, an invisible hand is guiding us. The invisible hand is not always benevolent. It may also work adversely. Why else would the bankruptcy of

…

show some regularity and predictability. Devices such as the invisible hand are ways of coping with this complexity so that we can grasp its working. Adam Smith’s other powerful idea was that in order to generate and guarantee prosperity, there should be minimal restrictions on people’s choices. Governments should stick

…

of businessmen in France told the King’s Finance Minister, Colbert, “Laissez-nous passez; laissez-nous faire” [Let us pass; let us do things ourselves]. Adam Smith never used the expression laissez-faire but the idea of letting the economy be free of odious restrictions on the movement of goods and people

…

caught on. Indeed, when the French Revolution broke out, many blamed it on the radical ideas of Adam Smith! In his earlier book The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Adam Smith had expressed a distrust of someone trying to regulate a society from above. “The man of system,” he wrote, seems

…

a principle of motion of its own. Altogether different from that which the legislator might choose to impress upon it.2 The “Principle of Motion” Adam Smith and his Scottish contemporaries were part of the Scottish Enlightenment. They founded what we now consider to be the social sciences. They were deeply impressed

…

laws of the land as well as social conventions. But the dynamic energy unleashed by millions of people pursuing self-interest was the key to the wealth of nations. Adam Smith was a Deist, that is, someone who did not believe in the Revelation or the Virgin Birth but was religious. The fashionable doctrine in those

…

accumulation. The modern world wanted to be free as far as it could from such old-fashioned restrictions. Smith caught the spirit of the times Adam Smith also wrote on the perennial problem of inflation. He proposed a startling new way of viewing price volatility, a problem that had been plaguing the

…

the centers of gravity to which prices converged once the effects of money had been neutralized. Values were stable; prices volatile. Since Adam Smith was a Professor of Moral Philosophy, the Wealth of Nations was written in the style of a philosopher with a broad sweep of history and knowledge of almost the entire world and

…

advice. The Certainties of David Ricardo The years which followed Adam Smith’s death in 1790 were turbulent for Europe. Britain had already lost its colonies in North America. The Rebels had issued a Declaration of Independence in the same year the Wealth of Nations was published and defeated the mother country in a series of

…

22 years defeated the French at Waterloo in 1815. These years saw widespread political as well as economic turbulence. Inspired by the French Revolution and Adam Smith’s radical ideas, people imagined that the society they lived in could be much better. The Old Order of kings and the aristocrats could be

…

truth of John Locke’s theory on inflation but expanded to include an international context. David Ricardo (1772–1823) was a most unusual man. If Adam Smith was a reclusive philosopher, Ricardo was a busy man of affairs – stockbroker, landowner and, in his last years, Member of Parliament. He had shown no

…

with a Quaker woman and renounced Judaism to become a Christian. While visiting his convalescing wife in Bath one day, he happened to come across Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations in the local library, and immediately thought that he could make many of its propositions logically much tighter. Ricardo ended up

…

equilibrium. For hundreds of such goods and services their demand and supply would equilibrate simultaneously at a specific price. Here was the invisible hand of Adam Smith formulated mathematically as an instant solution which showed how the prices of all the goods and services were formed. One device to bring them into

…

Manchester in his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England. Marx could see that the growth of the industrial economy had made Adam Smith’s invisible hand much more problematical than was thought originally. The economy worked through convulsions of crises, ups and downs rather than a smooth establishment

…

century, but that will be discussed in its proper place. Chapter Three NEW TOOLS FOR A NEW PROFESSION Alfred Marshall and the Professionalization of Economics Adam Smith was a Professor of Moral Philosophy and David Ricardo a stockbroker. Thomas Robert Malthus was the first economist paid to teach the subject at Haileybury

…

, on the other hand, would drive a wedge between marginal cost and price and yield excess profits. Marshall gave a practical business air to economics. Adam Smith and all those who wrote in his tradition believed in the desirability of free movement of capital and labor between different sectors and the unrestricted

…

cultures and partly because during the recent recession public opinion has begun to scapegoat immigrants for what are larger macroeconomic difficulties. In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith provided a definitive answer to the hotly debated question: Where does growth come from? He showed that the best source of national growth was the

…

the Money Market,” 1837. 1 The Building Blocks 1.Earl J. Hamilton, War and Prices in Spain 1651–1800 (Russell & Russell, New York, 1969). 2.Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), ed. D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie (University of Glasgow Press, Glasgow, 1976), pp. 380–1. 3.J

…

by a Perusal of Mr. J. Horsley Palmer’s Pamphlet on the Causes and Consequences of the Pressure on the Money Market,” 1837. Philipson. N., Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life. Penguin, London, 2010. Phillips, A. W. H., “The Relationship between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the

…

Equilibrium Model of the Euro Area. ECB Working Paper 171. European Central Bank, Frankfurt, 2002. Smith, A., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), ed. R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner. University of Glasgow Press, Glasgow, 1976. Smith, A., The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), ed. D

…

(i), (ii), (iii) Smith, Adam (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) the founding of the political economy (i) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (i), (ii) The Theory of Moral Sentiments (i), (ii) social science, founding (i) Socialist International (i) society regulation (i) self-organizing (i) Solow, Robert (i

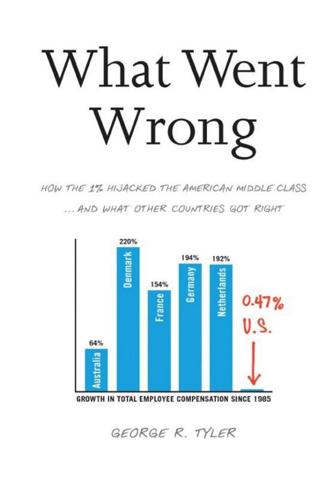

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

of canny mechanisms to maximize productivity and family income growth. Unhampered by ideology and buttressed with centuries of vigorous economic debate between the likes of Adam Smith and Friedrich Hayek, they focused on meeting election mandates demanding family prosperity. It wasn’t that difficult to accomplish, because these rich democracies came

…

reality reveals the hollowness of complaints by American firms such as Apple that routinely warn about high American labor costs and mediocre skill levels. Adam Smith, whose book, The Wealth of Nations, marked him as the father of capitalism, had heard the same thing when writing back in the eighteenth century. Like today, profits were

…

humanistic Ethics.32 Economics was considered central to the creation and preservation of democracy, making Aristotle one of the first economists two thousand years before Adam Smith. They both were market aficionados favoring competition; when it was limited through collusion by those whom Aristotle or Smith viewed as special interests—large

…

established a bright-line for whether democracy exists: Do law and regulation constrain the economically powerful and thus enable the broad diffusion of economic gains? Adam Smith, ironically championed by conservatives as the conceptualizer of free-market capitalism, understood this clearly. Perhaps his single most evocative conclusion emphasized his distrust of

…

some contrivance to raise prices.36 Drawing on the example of Bengali-based East India Company factotums, Smith explained at length in book IV of The Wealth of Nations how the business community’s motivation chronically and directly contravenes sound government policy. They aren’t amoral folks necessarily—just greedy. His writings make

…

is kept vibrant by being free from regulatory capture by any economic interest. Friedman would have none of it. Distrustful of government, he disagreed with Adam Smith, the Englishman John Maynard Keynes, and most mainstream economists on the appropriate scope of regulation in the economy. His suspicions of government regulation obligated

…

should be allocated within capitalism. I suspect President Reagan never actually understood this point. In the place of the carefully regulated market capitalism envisioned by Adam Smith and Keynes, his advisors urged with fervor a return to nineteenth-century market fundamentalism. That appeal was politically alluring to conservatives, including Ronald Reagan,

…

failure.”61 Regulatory Capture Regulatory capture describes a seizure of the tools of government by special interests; in this period, by the business community. As Adam Smith had concluded, the business community always seeks to influence government, and there was remarkable progress toward that goal during the Reagan era. The tone

…

of greed. That made him a great admirer of the grand experiment unfolding in the American colonies, especially in New England, which he praised in The Wealth of Nations: “There is more equality, therefore, among the English colonists than among the inhabitants of the mother country. Their manners are more republican, and their

…

without economic security and independence. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”55 Drawing on Adam Smith, their alternative was to remediate the flaws of laissez-faire capitalism with careful regulation, creating a twentieth-century grand bargain, with government maintaining prudent

…

. The vision of Smith, with his jaundiced eye on the merchant class, inspired European officials determining how best to prioritize family prosperity. They combined Adam Smith with mainstream Biblical verities drawn from the Catholic communitarian theology and the Protestant Social Gospel to alleviate poverty, hunger, and economic injustice. That is why

…

by President Clinton, Arthur Levitt, Jr. was no foolish ideologue channeling Ayn Rand. Savvy from a career running the American Stock Exchange, Levitt, like Adam Smith, understood that competition must be nurtured by prudent regulation. His solution to Greenspan’s ideological deregulation was simple: exploit the unparalleled expertise of the Big

…

from gambling with depositors’ funds.92 In striving for that balance, Australia and northern Europe have looked to Adam Smith as their touchstone on the proper role of regulation. Adam Smith: The Father of Regulated Capitalism Adam Smith was the Father of Capitalism, and argued in his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published

…

laissez-faire Reaganomics. For us today in interpreting Adam Smith, an especially important bubble arose in 1772 in Scotland, when the giant Ayr Bank and others collapsed, impoverishing Scotland for years. P.J. O’Rourke explained the environment in which Smith wrote the Wealth of Nations in a February 2009 column in the Financial Times

…

three years before his (Smith’s) birth. In 1772, while Smith was writing The Wealth of Nations, a bank run occurred in Scotland. Only three of Edinburgh’s 30 private banks survived.”94 As he looked out his study window, Adam Smith could scarcely avoid the financial news of the day, and realized the barrier such

…

know best, and those executives who profit best warrant superior standing. This Randian narcissism, which marks the Reagan era, is a stark rejection of Adam Smith’s capitalism, which places the interest of consumers above that of corporations. About the dangers of unbridled capitalism, where individuals can personally prosper by subverting

…

different perspectives and outcomes between shareholder capitalism and the stakeholder capitalism envisaged by Adam Smith. Adam Smith the Revolutionary: The Father of Stakeholder Capitalism Recall Adam Smith believed that producers should be subservient to the greater goal of serving consumers. That makes Adam Smith the antithesis of Ayn Rand. While Rand exalted and credentialed the selfish aspects

…

wondrous revolutionary century in the history of mankind. In making family prosperity their economic covenant, Australia and northern Europe hew closely to the dream of Adam Smith. The catastrophic Ayr Bank bankruptcy taught him firsthand the destructive effects of laissez-faire economics. Smith admonished readers to guard against such abuses and

…

March 5, 2010. Stock options were originally envisaged as a solution to the agency problem mentioned earlier, where managers prioritize their own interest, not shareholders’. Adam Smith recognized this disconnect centuries ago, writing critically of enterprise managers: “Directors … being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it

…

but he similarly argued that magnified self-interest would not benefit all, especially in complex economic settings featuring a division of labor and capital accumulation. Adam Smith agreed, sharing many of the same worries about markets, and his support for market regulation discussed earlier was strongly influenced by the insights of his

…

of Reagan-era politicians have fashioned themselves market aficionados and conservatives. By the standards of history, they are neither. They adopted Ayn Rand and threw Adam Smith under the bus, endorsing deregulation, the emergence of Red Queens and managerial capitalism characterized by stagnant wages, market failure in executive compensation, and widening

…

family capitalist countries, because citizens have been given clear choices at the polls and they’ve logically chosen self interest. Selfish voters have implemented Adam Smith’s dream of markets serving mankind by voting for public institutions and policies to institutionalize family economic sovereignty as national covenants. They strive at every

…

improving efficiency. During most of the industrial era, some sizable portion of such efficiency improvements have been shared between employers and employees, just as Adam Smith and Alfred Marshall presumed. But the whole story is more nuanced and less encouraging—a lot less encouraging. It turns out that productivity growth is

…

Cost Index 1979–2007. Output/hour is private nonfarm sector productivity growth. Source: “National Employment Survey and Employment Cost Survey,” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Adam Smith would have found that odd, because the American workforce is better educated and more productive today than ever in its history, yet wage earners for

…

of high profits. They are silent with regard to the pernicious effects of their own gains. They complain only of those of other people.”4 ADAM SMITH, The Wealth of Nations The Roman Empire of Caesar Augustus was an extractive behemoth built on trade, specialized labor in factories and farms, well-developed markets, and, most

…

to globalization and on upskilling to boost productivity and grow wages, it proved to be absurdly inadequate. It certainly redistributes income from families to those Adam Smith called merchants and master manufacturers. But it weakens productivity growth, and has proved to be the variant of capitalism you want your stoutest competitor

…

loading it on their shoulders.”34 Milton Friedman would grimace to hear that and American CEOs would shake their heads. But Wittenstein would have made Adam Smith proud of the remarkable stakeholder capitalism he first envisioned more than two centuries ago that has blossomed in the family capitalism countries. Section 4

…

way gains from growth are received, the way management interacts with employees, and the way domestic content is nurtured. Are these reforms likely under Reaganomics? Adam Smith wouldn’t think so. Recall his warning about governments comprised of merchants? To frame the answer, I first return to Joseph Stiglitz. Reprising Aristotle

…

have mastered the art of self-aggrandizement and become millionaires. But in terms of delivering value for others, they have proven to be lemons. Those Adam Smith called merchants and master manufacturers must be reoriented to eliminate short-termism, here lamented editorially by the Financial Times in March 2009: “Good business

…

translate into support from across the political spectrum. One thing is certain. The reforms proposed provide the only viable pathway for restoring the promise of Adam Smith. He gazed across lands where income disparities were stark and envisioned a better world, one where economic sovereignty resided with families. Americans face that

…

Charles Duhigg and Keith Bradsher, “How the U.S. Lost Out on iPhone Work,” New York Times, January 21, 2012. 13 Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London: Oxford University Press, 1993), 94. CHAPTER 2 1 Peter Whoriskey, “A bargain for BMW means jobs for 1,000

…

2010. 92 “Bonus Windfall Tax,” Editorial, Financial Times, Nov. 20, 2009. 93 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (New York: Oxford University Press Classics), 376. 94 P.J. O’Rourke, “Adam Smith Gets the Last Laugh,” Financial Times, Feb. 10, 2009. 95 Ibid. 96 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 129. 97 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 188. 98 Trevor Manuel, “Let Fairness Triumph over Corporate Profits,” Financial Times

…

, March 16, 2009. 99 Nicholas Phillipson, Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life (Hartford, CT: Yale University Press, 2010

…

and Nitin Nohria, “Management Needs to Become a Profession,” Financial Times, Oct. 20, 2008. 27 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 368–69. 28 Joe Nocera, “Nice Wasn’t Part of the Deal,” New York Times, Aug. 1, 2009. 29 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations. 30 Milton Friedman, “Rethinking the Social Responsibility of Business,” Reason, October 2005. 31 David Magee,

…

, “Income Inequality: Too Big to Ignore,” New York Times, Oct. 17, 2010. An excellent biography of Smith is Nicholas Phillipson’s Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life. 52 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations. 53 Amartya Sen, “Adam Smith’s Market Never Stood Alone.” 54 As quoted by Hedrick Smith, “When Capitalists Cared,” New York Times, Sept. 3, 2012. 55

…

Appointments: A Market-Based Explanation for Recent Trends,” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings May 2004. 60 Scott Thrum, “Oracle’s Ellison: Pay King.” 61 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, book V, chapter I, part 3, article I. 62 Liu Zheng and Xianming Zhou, “The Effects of Executive Stock Options on Firm Performance: Evidence From

…

and the National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. Also see James Surowiecki, “Mind the Gap,” The Financial Page, The New Yorker, July 9, 2012. 13 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, book IV, chapter vii, 372–73. 14 Claire Gatinois, “The Bosses’ Lament,” Le Monde, May 28, 2012. 15 Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics (London:

…

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975). 11 David Cay Johnston, Perfectly Legal, 3. 12 Sean Wilentz, “Confounding Fathers,” The New Yorker, Oct. 18, 2010. 13 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 451, and “Tax Policy Concept Paper,” American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2007, 1. 14 “Tax Policy Concept Paper,” American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

…

Wages Fail to Match a Rise in Productivity,” New York Times, Aug. 28, 2006. 3 As quoted by David Cay Johnston, Free Lunch, 270. 4 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, book I, chap. IX, 94. 5 Timothy H. Parsons, The Rule of Empires (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 36. 6 Javier Blas, “OPEC

…

“Transforming the EITC to Reduce Poverty and Inequality,” Pathways, Stanford University (Winter 2009). 52 Chris Hanger, “Inside the Journals,” The Churchill Centre, Washington, DC. 53 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 94. 54 Paul Gregg, “The Use of Wage Floors as Policy Tools,” OECD Economic Studies no. 31 (2000), Paris, OECD. 55 “U.K. Low Pay

…

Battellino, “Twenty Years of Economic Growth,” address to Moreton Bay Regional Council, Redcliffe, Queensland, Aug. 20, 2010. 13 Robert Kuttner, “The Copenhagen Consensus, Reading Adam Smith in Denmark,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2008. 14 As quoted by Patricia Veldhuis “Unemployment at 3.7 Percent—a Dutch Miracle?,” NRC Netherlands, Handelsblatt, Dec

…

–15 Lynn Stout and, 163 Milton Friedman and, 47, 102–4, 142, 205 Reaganomics and, 38–40, 46, 66, 163, 177–78, 235, 442–43 The Wealth of Nations, 13, 27, 60–61, 271, 339 Shierholz, Heidi (economist, Economic Policy Institute), 234 Shiller, Robert J. (economist), 30, 63, 82, 162, 465 Shine, Willy,

…

241 Squam Lake economists, 465 Staats, Bradley R., 161 Stakeholder capitalism, 46, 101, 108, 115–21, 287–306. See also codetermination; European countries; shareholder capitalism Adam Smith and, 111–12 attitudes towards employees: shareholder capitalism vs. stakeholder capitalism, 115–19 attitudes towards investors: shareholder capitalism vs. stakeholder capitalism, 119–21 Friedman criticism

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

with a long title destined to have gargantuan global impact. The author was Dr. Adam Smith, a quiet, absent-minded professor who taught "moral philosophy" at the University of Glasgow. The Wealth of Nations was the intellectual shot heard around the world. Adam Smith, a leader in the Scottish Enlightenment, had put on paper a universal formula for

…

introduction by Max Lerner. There have been many editions of The Wealth of Nations, including the official edition issued by the University of Glasgow Press, but this edition is the most popular. It was not a book for aristocrats and kings. In fact, Adam Smith had little regard for the men of vested interests and commercial

…

little progress had been achieved over the centuries in England and Europe because of the entrenched system known as mercantilism. One of Adam Smith's main objectives in writing The Wealth of Nations was to smash the conventional view of the economy, which allowed the mercantilists to control the commercial interests and political powers of

…

of the rich and the powerful, but what would be the origin of wealth for the whole nation and the average citizen? That was Adam Smith's paramount question. The Wealth of Nations was not just a tract on free trade, but a world view of prosperity. The Scottish professor forcefully argued that the keys to

…

production and exchange be maximized and thereby encourage the "universal opulence" and the "improvement of the productive power of labor"? Adam Smith had a clear answer: Give people their economic freedom! Throughout The Wealth of Nations, Smith advocated the principle of "natural liberty," the freedom to do what one wishes with little interference from the state

…

most advantageous to themselves, is a manifest violation of the most sacred rights of mankind" (549). Under Adam Smith's model of natural liberty, wealth creation was 2. This passage in the first chapter of The Wealth of Nations is remarkably similar to the theme developed by Leonard Read in his classic essay, "I, Pencil," which

…

capital without government restraint—important keys to economic growth. Adam Smith endorsed the virtues of thrift, capital investment, and labor-saving machinery as essential ingredients to promote rising living standards (326). In his chapter on the accumulation of capital (Chapter 3, Book II) in The Wealth of Nations, Smith emphasized saving and frugality as keys to

…

economic growth, in addition to stable government policies, a competitive business environment, and sound business management. Smith's Classic Work Receives Universal Acclaim Adam Smith's eloquent advocacy of natural liberty fueled the minds of

…

of politics, dismantling the old mercantilist doctrines of protectionism and enforced labor. Much of the worldwide movement toward free trade can be attributed to Adam Smith's work. The Wealth of Nations was the ideal document to usher in the Industrial Revolution and the political rights of man. Smith's magnum opus has received almost universal

…

spent half a dozen years studying Greek and Latin classics, French and English literature, and science and philosophy. Referring to Oxford University, he wrote in The Wealth of Nations that "the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching" (Smith 1965 [1776],

…

ing in his old nightgown and ended up several miles outside town. 4. George Stigler, whose favorite economist was Adam Smith, was known for telling his students at Chicago that he recommended all of The Wealth of Nations "except page 720" (Stigler 1966,168n). If students looked up this passage, found in book V, part II

…

, article 2, they encountered Smith's attack on the teaching profession and the "sham-lecture." But if you ask me, that citation is nothing compared to what Adam Smith wrote a

…

even a Bantam paper-back, unabridged! My preference is the 1937 (latest reprint, 1994) Modern Library edition, edited by Edwin Cannan. The significance of The Wealth of Nations has reached such biblical proportions that a complete concordance was prepared by Fred R. Glahe (1993), economics professor at the University of Colorado. Oh, the

…

of computers! Did you know that the word "a" appears 6,691 times in The Wealth of Nations? A concordance is undoubtedly valuable, especially for scholars. For example, "de-5.1 recommend the book Adam Smith Across Nations: Translations and Receptions of The Wealth of Nations, edited by Cheng-chung Lai (2000), for a fascinating account of the influence of

…

Adam Smith's book over the centuries. mand" appears 269 times while "supply" appears only 144 times

…

replaced by reasonable duties. Smith intended to write a third philosophical work on politics and jurisprudence, a sequel to his Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations.1 Yet he apparently spent a dozen years enforcing arcane customs laws instead. Such is the lure of government office and job security. Another

…

self-interest is often called "the invisible hand," based on a famous passage (paraphrased) from The Wealth of Nations: "By pursuing his own self interest, every individual is led by an invisible hand to promote the public interest" (423). Adam Smith's invisible hand doctrine has become a popular metaphor for unfettered market capitalism. Although Smith

…

uses the term only once in The Wealth of Nations, and sparingly elsewhere, the phrase "invisible hand" has come to symbolize the workings of

…

hand theory of the marketplace has become known as the "first fundamental theorem of welfare economics."8 George Stigler calls it the "crown jewel" of The Wealth of Nations and "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics." He adds, "Smith had one overwhelmingly important triumph: he put into the center of

…

Hand Surprisingly, Adam Smith uses the expression "invisible hand" only three times in his writings. The references are so sparse that economists and political commentators seldom mentioned the invisible hand idea by name in the nineteenth century. No references were made to it during the celebrations of the centenary of The Wealth of Nations in 1876

…

advance the interests of the society. (Smith 1982 [1759], 183-85)" The third mention, already quoted above, occurs in a chapter on international trade in The Wealth of Nations, where Smith argues against restrictions on imports, and against the merchants and manufacturers who support their mercantilist views. Here is the complete quotation: As every

…

Creator, the great Judge of hearts, Deity, and the all-seeing Judge of the world. How Religious Was Adam Smith? That God is not mentioned in The Wealth of Nations has caused some observers to conclude that Adam Smith, like his closest friend of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume, was a nonbeliever. Smith did in fact share many

…

, or rewards and punishments in a future life. His Theory of Moral Sentiments endured six editions during his lifetime, and the final one, written after The Wealth of Nations, makes frequent references to God. As Robert Heilbroner states, the theme of "the Invisible Hand . . . runs through all of the Moral Sentiments. .. . The Invisible

…

faith in capitalism (Skousen 2005, 261-67). Does Adam Smith Condone Egotism and Greed? Critics worry that the Scottish blueprint for freedom would also give license to avarice and fraud, even "social strife, ecological damage, and the abuse ^f power" (Lux 1990). Is not The Wealth of Nations an unabashed endorsement of selfish greed and vanity

…

? How could Adam Smith ignore everyday cases of rapacious capitalists deceiving, defrauding, and taking advantage of customers, thus pursuing their own self-interest at

…

not just an economist, but a professor of moral philosophy. Das Adam Smith Problem: Sympathy Versus Self-Interest In his 1759 work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith wrote that "sympathy" was the driving force behind a benevolent, prosperous society. In The Wealth of Nations, "self-interest" became the primary motive. German philosophers called this apparent

…

contradiction Das Adam Smith Problem, but Smith himself saw no conflict between the two. He took

…

spokesman for the Physiocrats, Quesnay endorsed the false belief in agriculture as the only "productive" expenditure and industry as "sterile." As to Quesnay's influence, The Wealth of Nations proclaimed Dr. Quesnay a "very ingenious and profound author" who promoted the popular slogan "Laissez faire, laissez passer," a phrase Smith would endorse wholeheartedly,

…

laissez-faire economics. (He preferred "natural liberty" or "perfect liberty.") As a leading Physiocrat, Quesnay opposed French mercantilism, protectionism, and state interventionist policies. However, The Wealth of Nations denied the basic physiocratic premise that agriculture, not manufacturing and commerce, was the source of all wealth (1965 [1776], 637-52). Richard Cantillon The other

…

house to cover up the crime. Cantillon's Essay is really quite impressive and undoubtedly influenced Adam Smith. It focuses on the automatic market mechanism of supply and demand, the vital role of entrepreneurship (downplayed in The Wealth of Nations), and a sophisticated "pre-Austrian" analysis of monetary inflation—how inflation not only raises prices,

…

but changes the pattern of spending. Jacques Turgot Jacques Turgot (1727-81) was a leading French Physiocrat whose profound work, Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766), also inspired Adam Smith. As a

…

The Wealth of Nations. Condillac's economics was amazingly advanced. He recognized that manufacturing was productive, that exchange represented unequal values, that both sides gain from commerce, and that prices are determined by utility value, not labor value (Macleod 1896). David Hume The great philosopher David Hume (1711-76) was a close friend of Adam Smith

…

John Rae and Ian Simpson Ross give credence to the story that the American founding father, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), developed a friendship with Adam Smith and had some influence on his writing The Wealth of Nations. John Rae recounted how Franklin visited with Smith in Scotland and London and, according to a friend of Franklin

…

, "Adam Smith when writing his Wealth of Nations was in the habit of bringing chapter after chapter as he composed it to himself [Franklin], Dr. Price,

…

1 They are equalized at the margin. 1. Here's a strange twist in the history of economics: Adam Smith actually had the correct answer to the diamond-water paradox a decade prior to writing The Wealth of Nations. Smith's lectures on jurisprudence, delivered in 1763, reveal that he recognized that price was determined by

…

Smith 1982 [1763], 33, 3, 358). Oddly, his cogent explanation of the diamond-water paradox disappeared when he was writing Chapter 4, Book I, of The Wealth of Nations. Was Smith suffering from absent-mindedness? Economist Roger Garrison doesn't think so. He blames the change on Smith's Calvinist background, which emphasized the

…

water and other "useful" goods. Garrison points to Smith's odd dichotomy between "productive" and "unproductive" labor; see the third chapter of Book II in The Wealth of Nations, where Smith refers to professions such as minister, physician, musician, orator, actor, and other producers of services as "frivolous" occupations (1965 [1776], 315). Farmers

…

cherished ambitions. In 1895, the London School of Economics (LSE) was established, devoted almost entirely to economic studies. In sum, Adam Smith had talked about his "Newtonian" method in his study of the wealth of nations, but not for another century did economics truly become established as a science and a separate discipline. The Role of

…

in an age of inflation. In 1976, on the 200th anniversary of both the Declaration of Independence and the publication of The Wealth of Nations, it was fitting that Friedman won the Nobel Prize. Adam Smith was his mentor. "The invisible hand has been more potent for progress than the visible hand for retrogression," he wrote

…

"Comment on the Critics." In Milton Friedman's Monetary Framework, ed. Robert J. Gordon, 132-37. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. . 1978. "Adam Smith's Relevance for 1976." In Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776-1976 Bicen tennial Essays, ed. FredR. Glahe. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 7-20. . 1981. The Invisible Hand in Economics and

…

(Fall): 287-94. . 2001. Time and Money. London: Routledge. Glahe, Fred R., ed. 1978. Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776-1976 Bi-centennial Essays. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press. . 1993. Adam Smith's An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations: A Concordance. Landam, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. Gordon, H. Scott. 1967. "Discussion on Das Kapital

…

Spring Mills, PA: Libertarian Press. . 1980 [1952]. Planning for Freedom. 4th ed. Spring Mills, PA: Libertarian Press. Modigliani, Franco. 1986. "Life Cycle, Individual Thrift, and the Wealth of Nations." American Economic Review 76, 3 (June): 297-313. Moggridge, D.E. 1983. "Keynes as an Investor." In The Collected Works of John Maynard Keynes, 1

…

Washington, DC: Capital Press. Smith, Adam. 1947. "Letter from Adam Smith to William Strahan." In Supplement to David Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, ed. Norman Kemp Smith. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 248. . 1965 [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. New York: Modern Library. . 1982 [1759]. The Theory of Moral

The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives

by Ernest Scheyder · 30 Jan 2024 · 355pp · 133,726 words

tin eventually overtook those of silver, but they could not match the wealth that silver had generated. It was an inevitability that Adam Smith had warned about in his capitalistic guidepost The Wealth of Nations, declaring: “If new mines were discovered as much superior to those of Potosí as they were superior to those of Europe

…

Times, May 29, 1977, www.nytimes.com/1977/05/29/archives/the-glory-that-was-once-potosi-the-glory-that-was-once-potosi.html. 10. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Chapter 11. 11. Lawrence Wright, “Lithium Dreams: Can Bolivia Become the Saudi Arabia of the Electric-Car Era?” The New Yorker, March 15, 2010, www

Globalists

by Quinn Slobodian · 16 Mar 2018 · 451pp · 142,662 words

the label “neoliberalism.” The term appeared poised for the mainstream, appearing in the Financial Times, the Guardian, and other newspapers.11 Also in 2016, the Adam Smith Institute, founded in 1977 and a source of guidance for Margaret Thatcher, “came out as neoliberals,” in their words, shedding their former moniker, “libertarian.”12

…

time.21 The metaphor of the barometer implied that the economy was like the weather, a sphere outside of direct human control. One could adapt Adam Smith’s famous metaphor of the invisible hand to speak of the invisible wind of the market, captured in charts and graphs. The economic conditions portrayed

…

of national welfare state programs in the late 1960s make it easy to mistake the scale of the term for Hayek, Mises, Lippmann, and indeed Adam Smith before them. For all of them, the term meant the full reach of the realm of market exchange; the Great Society, as Mises put it

…

, as in the case of income equalization, that they get less than they might have had in order that others may get more.”52 Reversing Adam Smith’s hypothetical question about how much Western pain would be averted for the death of a Mandarin, they asked how much Western effort would be

…

Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, ed. Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 90; Sam Bowman, “Coming Out as Neoliberals,” Adam Smith Institute Blog, October 11, 2016, https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/coming-out-as-neoliberals. 13. Lars Feld quoted in Bert Losse, “Economic Neoliberalism: Philosophy of

…

and Global Change 10, no. 1 (1998): 23–38. For other key studies, see Sarah Babb, Behind the Development Banks: Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Nitsan Chorev, “The Institutional Project of Neo-Liberal Globalism: The Case of the WTO,” Theory and Society 34, no

…

York: United Nations, 1976). 24. Tinbergen et al., Reshaping the International Order. 25. See Sarah Babb, Behind the Development Banks: Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). 26. Hank Overbeek and Kees van der Pijl, “Restructuring Capital and Restructuring Hegemony: Neo-Liberalism and the Unmaking of

…

at the Centre William Rappard (Geneva: World Trade Organization, 2015), 9. 80. Petersmann, International Economic Law in the 21st Century, 9. 81. F. A. Hayek, “Adam Smith’s Message in Today’s Language,” in New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, ed. F. A. Hayek (Chicago: University of

…

signals, 225, 229, 234, 245, 256–257, 261, 274, 281. See also Cybernetics; Information Silesia, 110 Slavery, 108, 161, 195 Smith, Adam, 61, 81, 103; Adam Smith Institute, 3 Smith, Ian, 175, 177–178 Social democracy, 34, 127, 138; in Austria, 44 Socialism, 81, 89, 107, 161; socialist calculation debate, 82, 107

Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone

by John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai · 25 Jul 2025

The Oil Age Is Over: What to Expect as the World Runs Out of Cheap Oil, 2005-2050

by Matt Savinar · 2 Jan 2004 · 127pp · 51,083 words

Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health

by H. Gilbert Welch, Lisa M. Schwartz and Steven Woloshin · 18 Jan 2011 · 302pp · 92,546 words

The Communist Manifesto

by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels · 1 Aug 2002 · 51pp · 14,616 words

Shorter: Work Better, Smarter, and Less Here's How

by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang · 10 Mar 2020 · 257pp · 76,785 words

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

by Andrew Yang · 2 Apr 2018 · 300pp · 76,638 words

How the City Really Works: The Definitive Guide to Money and Investing in London's Square Mile

by Alexander Davidson · 1 Apr 2008 · 368pp · 32,950 words

Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century

by Mark Leonard · 4 Sep 2000 · 131pp · 41,052 words

The Prince

by Niccolò Machiavelli and Peter Bondanella · 1 Jan 1532 · 95pp · 32,910 words

How to Be Human: An Autistic Man's Guide to Life

by Jory Fleming · 19 Apr 2021 · 150pp · 50,821 words

The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives

by Leonard Mlodinow · 12 May 2008 · 266pp · 86,324 words

The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought

by Ayn Rand, Leonard Peikoff and Peter Schwartz · 1 Jan 1989 · 411pp · 136,413 words

Blue Mars

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 23 Oct 2010 · 824pp · 268,880 words

Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?

by Thomas Geoghegan · 20 Sep 2011 · 364pp · 104,697 words

Barometer of Fear: An Insider's Account of Rogue Trading and the Greatest Banking Scandal in History

by Alexis Stenfors · 14 May 2017 · 312pp · 93,836 words

Armed Humanitarians

by Nathan Hodge · 1 Sep 2011 · 390pp · 119,527 words

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by Roger Scruton · 16 Nov 2017 · 190pp · 56,531 words

Emergence

by Steven Johnson · 329pp · 88,954 words

The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century

by George Friedman · 30 Jul 2008 · 278pp · 88,711 words

The Patient Will See You Now: The Future of Medicine Is in Your Hands

by Eric Topol · 6 Jan 2015 · 588pp · 131,025 words

The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalization

by Michael O’sullivan · 28 May 2019 · 756pp · 120,818 words

Makers

by Chris Anderson · 1 Oct 2012 · 238pp · 73,824 words

Trading Risk: Enhanced Profitability Through Risk Control

by Kenneth L. Grant · 1 Sep 2004

The Diary of a Bookseller

by Shaun Bythell · 27 Sep 2017 · 310pp · 88,827 words

SuperFreakonomics

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 19 Oct 2009 · 302pp · 83,116 words

In Defense of Global Capitalism

by Johan Norberg · 1 Jan 2001 · 233pp · 75,712 words

The Myth of Meritocracy: Why Working-Class Kids Still Get Working-Class Jobs (Provocations Series)

by James Bloodworth · 18 May 2016 · 82pp · 21,414 words

Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money That We Understand to Money That Understands Us (Perspectives)

by David Birch · 14 Jun 2017 · 275pp · 84,980 words

Beyond Outrage: Expanded Edition: What Has Gone Wrong With Our Economy and Our Democracy, and How to Fix It

by Robert B. Reich · 3 Sep 2012 · 124pp · 39,011 words

The Road Ahead

by Bill Gates, Nathan Myhrvold and Peter Rinearson · 15 Nov 1995 · 317pp · 101,074 words

The Tyranny of Nostalgia: Half a Century of British Economic Decline

by Russell Jones · 15 Jan 2023 · 463pp · 140,499 words

Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves

by Nicola Twilley · 24 Jun 2024 · 428pp · 125,388 words

World Cities and Nation States

by Greg Clark and Tim Moonen · 19 Dec 2016

Sleeping Giant: How the New Working Class Will Transform America

by Tamara Draut · 4 Apr 2016 · 255pp · 75,172 words

Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World

by Paul Collier · 30 Sep 2013 · 303pp · 83,564 words

Fred Schwed's Where Are the Customers' Yachts?: A Modern-Day Interpretation of an Investment Classic

by Leo Gough · 22 Aug 2010 · 117pp · 31,221 words

Who Gets What — and Why: The New Economics of Matchmaking and Market Design

by Alvin E. Roth · 1 Jun 2015 · 282pp · 80,907 words

Inside the Robot Kingdom: Japan, Mechatronics and the Coming Robotopia

by Frederik L. Schodt · 31 Mar 1988 · 361pp · 83,886 words

1494: How a Family Feud in Medieval Spain Divided the World in Half

by Stephen R. Bown · 15 Feb 2011 · 295pp · 92,670 words

Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences

by Edward Tenner · 1 Sep 1997

An Economist Gets Lunch: New Rules for Everyday Foodies

by Tyler Cowen · 11 Apr 2012 · 364pp · 102,528 words

Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net's Impact on Our Minds and Future

by John Brockman · 18 Jan 2011 · 379pp · 109,612 words

The Evolution of Useful Things

by Henry Petroski · 2 Jan 1992 · 307pp · 97,677 words

Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make a Difference

by William MacAskill · 27 Jul 2015 · 293pp · 81,183 words

Brazillionaires: The Godfathers of Modern Brazil

by Alex Cuadros · 1 Jun 2016 · 433pp · 125,031 words

Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline

by Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson · 5 Feb 2019 · 280pp · 83,299 words

Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations

by Clay Shirky · 28 Feb 2008 · 313pp · 95,077 words

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words

Imagining India

by Nandan Nilekani · 25 Nov 2008 · 777pp · 186,993 words

Power Systems: Conversations on Global Democratic Uprisings and the New Challenges to U.S. Empire

by Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian · 1 Nov 2012

Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant

by W. Chan Kim and Renée A. Mauborgne · 20 Jan 2014 · 287pp · 80,180 words

The Irrational Economist: Making Decisions in a Dangerous World

by Erwann Michel-Kerjan and Paul Slovic · 5 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 108,119 words

The People vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (And How We Save It)

by Jamie Bartlett · 4 Apr 2018 · 170pp · 49,193 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by Jane Gleeson-White · 14 May 2011 · 274pp · 66,721 words

The Techno-Human Condition

by Braden R. Allenby and Daniel R. Sarewitz · 15 Feb 2011

Tyler Cowen-Discover Your Inner Economist Use Incentives to Fall in Love, Survive Your Next Meeting, and Motivate Your Dentist-Plume (2008)

by Unknown · 20 Sep 2008 · 246pp · 116 words

The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions

by Victor Haghani and James White · 27 Aug 2023 · 314pp · 122,534 words

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by Thomas W. Malone · 14 May 2018 · 344pp · 104,077 words

Elsewhere, U.S.A: How We Got From the Company Man, Family Dinners, and the Affluent Society to the Home Office, BlackBerry Moms,and Economic Anxiety

by Dalton Conley · 27 Dec 2008 · 204pp · 67,922 words

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay

by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman · 14 Oct 2019 · 232pp · 70,361 words

Letters From an Astrophysicist

by Neil Degrasse Tyson · 7 Oct 2019 · 189pp · 49,386 words

The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality

by Oded Galor · 22 Mar 2022 · 426pp · 83,128 words

The Great Tax Robbery: How Britain Became a Tax Haven for Fat Cats and Big Business

by Richard Brooks · 2 Jan 2014 · 301pp · 88,082 words

Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won or Lost Together

by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin · 21 Jun 2023 · 248pp · 73,689 words

On the Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did to Me and How It Drives America Insane

by Emily Guendelsberger · 15 Jul 2019 · 382pp · 114,537 words

The Green New Deal: Why the Fossil Fuel Civilization Will Collapse by 2028, and the Bold Economic Plan to Save Life on Earth

by Jeremy Rifkin · 9 Sep 2019 · 327pp · 84,627 words

Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree World

by Robert Lawson and Benjamin Powell · 29 Jul 2019 · 164pp · 44,947 words

Third World America: How Our Politicians Are Abandoning the Middle Class and Betraying the American Dream

by Arianna Huffington · 7 Sep 2010 · 300pp · 78,475 words

The New Sell and Sell Short: How to Take Profits, Cut Losses, and Benefit From Price Declines

by Alexander Elder · 1 Jan 2008 · 394pp · 85,252 words

Impact: Reshaping Capitalism to Drive Real Change

by Ronald Cohen · 1 Jul 2020 · 276pp · 59,165 words

The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less

by Barry Schwartz · 1 Jan 2004 · 241pp · 75,516 words

The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival

by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan · 8 Aug 2020 · 438pp · 84,256 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

Why Your World Is About to Get a Whole Lot Smaller: Oil and the End of Globalization

by Jeff Rubin · 19 May 2009 · 258pp · 83,303 words

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 8 Oct 2017 · 322pp · 87,181 words

Financial Fiasco: How America's Infatuation With Homeownership and Easy Money Created the Economic Crisis

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2009 · 246pp · 74,341 words

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Gobal Crisis

by James Rickards · 10 Nov 2011 · 381pp · 101,559 words

Great American Hypocrites: Toppling the Big Myths of Republican Politics

by Glenn Greenwald · 14 Apr 2008 · 286pp · 79,601 words

Doctored: The Disillusionment of an American Physician

by Sandeep Jauhar · 18 Aug 2014 · 320pp · 97,509 words

Swindled: the dark history of food fraud, from poisoned candy to counterfeit coffee

by Bee Wilson · 15 Dec 2008 · 384pp · 122,874 words

The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic at Work and at Home

by Dan Ariely · 31 May 2010 · 324pp · 93,175 words

The Extreme Centre: A Warning

by Tariq Ali · 22 Jan 2015 · 160pp · 46,449 words

Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization

by Iain Gately · 27 Oct 2001 · 434pp · 124,153 words

The Wisdom of Crowds

by James Surowiecki · 1 Jan 2004 · 326pp · 106,053 words

Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges and Leaderboards

by Yu-Kai Chou · 13 Apr 2015 · 420pp · 130,503 words

The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics

by William R. Easterly · 1 Aug 2002 · 355pp · 63 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

Social Life of Information

by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid · 2 Feb 2000 · 791pp · 85,159 words

Writing on the Wall: Social Media - the First 2,000 Years

by Tom Standage · 14 Oct 2013 · 290pp · 94,968 words

Complexity: A Guided Tour

by Melanie Mitchell · 31 Mar 2009 · 524pp · 120,182 words

Culture & Empire: Digital Revolution

by Pieter Hintjens · 11 Mar 2013 · 349pp · 114,038 words

Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking

by Matthew Syed · 9 Sep 2019 · 280pp · 76,638 words

The Scandal of Money

by George Gilder · 23 Feb 2016 · 209pp · 53,236 words

The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance

by Henry Petroski · 2 Jan 1990 · 490pp · 150,172 words

How to Own the World: A Plain English Guide to Thinking Globally and Investing Wisely

by Andrew Craig · 6 Sep 2015 · 305pp · 98,072 words

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski · 5 Mar 2019 · 202pp · 62,901 words

Stubborn Attachments: A Vision for a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals

by Tyler Cowen · 15 Oct 2018 · 140pp · 42,194 words

The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth

by Jonathan Rauch · 21 Jun 2021 · 446pp · 109,157 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words