Thorstein Veblen

description: an American economist and sociologist, famous for introducing the term 'conspicuous consumption'

214 results

The Theory of the Leisure Class

by Thorstein Veblen · 10 Oct 2007 · 395pp · 118,446 words

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Veblen, Thorstein, 1857–1929 The theory of the leisure class / Thorstein Veblen; edited with an Introduction and notes by Martha Banta. p. cm. — (Oxford world’s classics) Originally published: New York : Macmillan, 1899. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN

…

the material in this Oxford World’s Classics ebook. Use the asterisks (*) throughout the text to access the hyperlinked Explanatory Notes. OXFORD WORLD’S CLASSICS THORSTEIN VEBLEN The Theory of the Leisure Class Edited with an Introduction and Notes by MARTHA BANTA OXFORD WORLD’S CLASSICS THE THEORY OF THE LEISURE CLASS

…

THORSTEIN VEBLEN was born in 1857 on the Wisconsin frontier, the sixth of twelve children of Thomas and Kari Veblen who emigrated from Norway in 1847. At

…

all the implications of Veblen’s classic study. Perhaps their quandary is caused by the fact, as one observer has stated, ‘no one remotely like Thorstein Veblen can ever be expected to appear again’.2 Certain economists and sociologists prefer to look away from this volume, finding themselves more at home with

…

? Neither was the case. Veblen’s life history provides its own compelling narrative of how not to succeed in the conventional ways of the world. Thorstein Veblen was born in 1857 of Norwegian immigrant parents on the Wisconsin frontier, the sixth of twelve children. He would die in seclusion in the mountains

…

be frightening but Americans were encouraged to feel proud of social systems that bred men capable of making vast amounts of money hand over fist. Thorstein Veblen did not concur that the practice of greed is a good thing under any guise. The ways of Wall Street and those of the jungle

…

Veblen shaped The Theory of the Leisure Class there is the nature of the man who wrote this all-important analysis of our society. Although Thorstein Veblen can be viewed as ‘a character’, more to the point is the kind of ‘character’ he possessed. Perhaps it is John Dos Passos who best

…

take over the original plates, which were used for subsequent reprints. SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Biography Diggins, John F., Thorstein Veblen: Theorist of the Leisure Class (Princeton, 1999). Dos Passos, John, The Bitter Drink: A Biography of Thorstein Veblen (San Francisco, 1939). Background Aaron, Daniel, Men of Good Hope: A Story of American Progressives (Oxford, 1951

…

York, 1907). James, William, The Principles of Psychology (New York, 1890). Louca, Francisco, and Perlman, Mark (eds.), Is Economics an Evolutionary Science? The Legacy of Thorstein Veblen (Cheltenham, 2000). Ross, Dorothy, The Origins of American Social Science (Cambridge, 1991). Silk, Leonard Solomon, Veblen: A Play in Three Acts (New York, 1966). Tilman

…

, Rick (ed.), A Veblen Treasury: From Leisure Class to War, Peace, and Capitalism (Armonk, NY, 2003). ——and Simich, J. L. (eds.), Thorstein Veblen: A Reference Guide (Boston, 1985). Trachtenberg, Alan, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York, 1982). Critical Studies Banta, Martha

…

, Taylored Lives: Narrative Productions in the Age of Taylor, Veblen, and Ford (Chicago, 1993). Brown, Doug (ed.), Thorstein Veblen in the Twenty-First Century: A Commemoration of The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899–1999) (Cheltenham, 1998). Daugert, Stanley Matthew, The Philosophy of

…

Thorstein Veblen (New York, 2002). Diggins, John F., The Bard of Savagery: Thorstein Veblen and Modern Social Theory (New York, 1978). Dorfman, Joseph, Thorstein Veblen and His America (New York, 1961). Dowd, Douglas F. (ed.), Thorstein Veblen, A Critical Reappraisal: Lectures and Essays Commemorating The Hundredth Anniversary of

…

Veblen’s Birth (Ithaca, NY, 1958). Eby, Clare Virginia, Dreiser and Veblen: Saboteurs of the Status Quo (Columbia, Mo., 1998). Mestrovic, Stjepan Gabriel, Thorstein Veblen on Culture and Society (London, 2003). Patsouras, Louis

…

, Thorstein Veblen and the American Way of Life (Montreal, 2004). Riesman, David, Thorstein Veblen: A Critical Interpretation (New York, 1953). Rosenberg, Bernard, The Values of Veblen: A Critical Appraisal (Washington

…

, DC, 1956). Schneider, Louis, The Freudian Psychology and Veblen’s Social Theory (New York, 1948). Seckler, David, Thorstein Veblen and the Institutionalists: A Study in the Social Philosophy of Economics (Boulder, Colo., 1975). Splindler, Michael, Veblen & Modern America: Revolutionary Iconoclast (London, 2002). Tilman, Rick

…

, The Intellectual Legacy of Thorstein Veblen: Unresolved Issues (Westport, Conn., 1996). ——Thorstein Veblen and His Critics, 1891–1963: Conservative, Liberal, and Radical Perspectives (Princeton, 1992). Further Reading in Oxford World’s Classics Adams, Henry, The Education

…

… Audet: ‘now neglected faith and peace, and ancient honour and shame, dares to return’ (Horace, ‘Carmen Saeculare’). 1 Joseph Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America (New York, 1961), 422. 2 Bernard Rosenberg, Thorstein Veblen (New York, 1963), 1. It is heady to realize that dealing with Veblen’s career prompts paying attention to the

…

Mumford, Max Weber, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, John Maynard Keynes, Charles S. Peirce, George Mead, and John Dewey. Rick Tilman’s The Intellectual Legacy of Thorstein Veblen: Unresolved Issues (Westport, Conn., 1996) makes this point very well, since ‘legacy’ is the key word when it comes to assessing Veblen’s influence over

…

psychology, physiology, political science, and anthropology. 3 The following comments from the Yale Review and the Journal of Political Economy are cited in Dorfman’s Thorstein Veblen and His America, 191–2. 4 Adorno, ‘Veblen’s Attack on Culture’ (1941), cited in Rick Tilman and Jo Lo Simich (eds

…

.), Thorstein Veblen: A Reference Guide (Boston, 1985), 50. 5 After Veblen’s death in 1929, a tabulation of the sales of his ten books over his lifetime

…

to a friend, ‘The president doesn’t approve of my domestic arrangements; nor do I.’ From John Dos Passos, The Bitter Drink: A Biography of Thorstein Veblen (San Francisco, 1939), 12. 9 The original Dial was the voice for the Transcendentalists, edited by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson between 1840 and

…

: Immigrant Pioneers from Valdris. It corrects the view that the Veblens lived a raw frontier life advanced by Joseph Dorfman’s Thorstein Veblen and His America. Tilman’s The Intellectual Legacy of Thorstein Veblen also demonstrates that Veblen’s father, Thomas, was hardly like a Thomas Lincoln whose son was left to elevate his

…

library contained the works of Darwin, Spencer, Ricardo, Marx, and also Shakespeare, Swift, Dante, Carlyle, Balzac, Shaw, Hardy, Knut Hamsun, and Jack London. 34 Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America, 175. Macmillan had so little faith in the book’s commercial prospects Veblen was obliged to put up a guarantee. 35 See

…

Ward in Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America, 194, and Henderson in Tilman and Simich (eds.), Veblen: Reference Guide, 436–40. H. L. Mencken, himself a famous stylist of a

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

barriers to economic development facing postcolonial nations. Of the individuals profiled, some led the conventional lives of academics, although their thinking was far from conventional. (Thorstein Veblen, John Maynard Keynes, Joan Robinson, and Stuart Hall are examples.) Others were gentlemen scholars (William Thompson and Thomas Carlyle); journalist-authors (Henry George, John Hobson

…

the United States and other countries, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the emergence of huge industrial combines and a spendthrift plutocracy, which Thorstein Veblen, for one, subjected to merciless inspection. This period also saw the rise of imperialism, which Vladimir Lenin famously described as the highest stage of capitalism

…

the centuries. Unless its foundations be laid in justice the social structure cannot stand.”80 11 “The ideal pecuniary man is like the ideal delinquent” Thorstein Veblen and the Captains of Industry It was Mark Twain and his coauthor Charles Dudley Warner, in their 1873 novel The Gilded Age, who gave a

…

label to an American era characterized by political corruption and vulgar displays of wealth.1 And it was the economist Thorstein Veblen, in his 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class, who coined some of the most memorable terms to describe the sociology of that era

…

level of wealth inequality would be higher, it pointed out.10 To be sure, this conclusion wouldn’t have come as news to Henry George, Thorstein Veblen, or Rosa Luxemburg. On both sides of the Atlantic, socialists and left-liberals had long tied the rise of monopolies, trusts, and other big capitalist

…

, money and credit, international economics, and the history of economic thought. His teachers included two eminent American economists: Herbert J. Davenport, a former student of Thorstein Veblen, and Edwin Seligman, an expert on public finance who was also a progressive activist and a former president of the Society for Ethical Culture. Seligman

…

and maintain the artisans and their families and so forms a complete cycle with the locally available reeds which constitute the raw materials.”35 Echoing Thorstein Veblen, Kumarappa also argued that in modern societies a great deal of consumption was driven by fashion and social pressures rather than genuine need. “For a

…

. George, Progress and Poverty, 480–81. 78. George, Progress and Poverty, 495. 79. George, Progress and Poverty, 473. 80. George, Progress and Poverty, 495. 11. Thorstein Veblen and the Captains of Industry 1. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (Hartford, CT: American Publishing, 1873), https

…

, Forerunner of Progressivism, 1880–1901,” The Mississippi Valley History Review 37, no. 4 (March 1951), 599–624. 9. For Veblen’s life, see Joseph Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America (New York: Viking Press, 1934); and Charles Camic, Veblen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020). 10. Dorfman, Veblen and His America, 56

…

. Edward A. Ross, “The Causes of Race Superiority,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 18 (July 1901), 67–89. 22. Thorstein Veblen, “Review of Misère de la Philosophie by Karl Marx, and of Socialisme et Science Positive by Enrico Ferri,” Journal of Political Economy 5, no. 1

…

.org/stable/1817518?seq=4, reprinted in Charles Camic and Geoffrey M. Hodgson, eds., The Essential Writings of Thorstein Veblen (New York: Routledge, 2011); see also Emilie J. Raymer, “A Man of His Time: Thorstein Veblen and the University of Chicago Darwinists,” Journal of the History of Biology 46 (2013), 669–98. 23. Veblen

…

Consumers Guide,” no. 104, https://www.google.com/books/edition/1897_Sears_Roebuck_Co_Catalogue/_gdrCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover. 28. Thorstein Veblen, “The Economic Theory of Woman’s Dress,” The Popular Science Monthly, no. 46 (1894), 198–205, http://www.modetheorie.de/fileadmin/Texte/v/Veblen-The

…

His Followers II: The Later Marxism,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 21, no. 1 (February 1907), 299–322, 304; see also Camic, Veblen, 319. 30. Thorstein Veblen, “Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 12, no. 4 (July 1898), 373–97. 31. Camic, Veblen, 274. 32. Camic

…

, Veblen, 274. 33. Camic, Veblen, 298. 34. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 10. 35. Veblen, Theory of the Leisure Class, 21. 36. Veblen, Theory of

…

,” 432. 60. Cummings, “Theory of the Leisure Class,” 441, 443. 61. Camic, Veblen, 10–11. 62. Cummings, “Theory of the Leisure Class,” 443–44. 63. Thorstein Veblen, “Mr. Cummings’s Strictures on ‘The Theory of the Leisure Class,’” The Journal of Political Economy 8, no. 1 (December 1899), 106–17. 64. Camic

…

, Veblen, 321–22. 65. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of Business Enterprise (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1904; 2016 reprint), 18. 66. Veblen, Theory of Business Enterprise, 18–19. 67. Veblen

…

Laws of Motion 10. “We must make land common property”: Henry George’s Moral Crusade 11. “The ideal pecuniary man is like the ideal delinquent”: Thorstein Veblen and the Captains of Industry 12. “A particularly crude form of capitalism”: John Hobson’s Theory of Imperialism 13. “Capital knows no other solution to

Turing's Cathedral

by George Dyson · 6 Mar 2012

of Stanislaw Ulam. Stanislaw Marcin Ulam (1909–1984): Polish American mathematician and protégé of John von Neumann. Oswald Veblen (1880–1960): American mathematician, nephew of Thorstein Veblen, and first professor appointed to the IAS in 1932. Theodore von Kármán (1881–1963): Hungarian American aerodynamicist, founder of Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). John von

…

college, including their four daughters and two subsequently distinguished sons. Andrew Veblen became a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Iowa, while Thorstein Veblen, born in 1857, became an influential social theorist, best known for coining the phrase “conspicuous consumption” in his 1899 masterpiece The Theory of the Leisure

…

Class. Thorstein Veblen had a Darwinian eye, sharpened by growing up on the edge of the wilderness, for the coevolution of corporations, financial instruments, and machines. Although respected

…

against the German war machine, but by the time the Proving Ground was operational, the war in Europe was drawing to a close. According to Thorstein Veblen, the United States had entered the war, belatedly, only to ensure that the transnational interests of the industrialists would be protected against any social upheavals

…

to “the Institute for Advanced Salaries,” while Princeton University graduate students referred to “the Institute for Advanced Lunch.” The Institute was the unacknowledged realization of Thorstein Veblen’s original call (in 1918) for “a freely endowed central establishment where teachers and students of all nationalities, including Americans with the rest, may pursue

…

Princeton and its Institutions (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1879) vol. 1, p. 36. THREE: VEBLEN’S CIRCLE 1. Mrs. R. H. Fisher, in Joseph Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America (New York: Viking, 1934), p. 504. 2. Herman Goldstine, interview with Albert Tucker and Frederik Nebeker, March 22, 1985, The Princeton Mathematics

…

. 616 (Jan. 28, 1933): 54; Flexner, I Remember, p. 375; ibid., pp. 377–78; Frank Aydelotte to Herbert H. Maass, June 15, 1945, IAS. 43. Thorstein Veblen, The Higher Learning in America (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1918), p. 45. 44. Flexner, I Remember, pp. 361 and 375. 45. Abraham Flexner to

…

that had changed hands only twice since the ownership of William Penn. (Abraham Flexner, I Remember [New York: Simon & Schuster, 1940]) Oswald Veblen, nephew of Thorstein Veblen (who coined the phrase “conspicuous consumption” in his 1899 The Theory of the Leisure Class), was a topologist, geometer, ballistician, and outdoorsman who, as a

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

this era were John Bates Clark at Columbia University, Frank A. Fetter at Cornell and Princeton, Richard T. Ely at the University of Wisconsin, and Thorstein Veblen, who established the institutional school of economics. It would be fair to say that the Americans were more remodelers than architects of a new building

…

was heavily criticized by fellow economists, who made the allegation that "neoclassical economics was essentially an apologetic for the existing economic order" (Stigler 1941, 297). Thorstein Veblen, in particular, used Clark as a foil in his diatribes against the prevailing economic system. Yet Clark's application of the marginality principle to labor

…

listeners, including George Bernard Shaw and Sydney Webb, to become socialists. See Skousen (2001, 229-30). They are the American Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) and the German Max Weber (1864-1920). Thorstein Veblen: The Voice of Dissent Veblen was the principal faultfinder and censor of the new theoretical capitalism. Having taught at ten institutions

…

gloomy view of capitalism transpired during the Roaring Twenties, when American consumers were making tremendous advances. Max Weber: A Spirited Defense of "Rational" Capitalism Fortunately, Thorstein Veblen was not the only social commentator on capitalism at the turn of the century. His chief antagonist came from across the Atlantic—the German sociologist

…

in the spirit of Adam Smith than Veblen. As John Patrick Diggins states, "No two social theorists could be more intellectually and temperamentally opposed than Thorstein Veblen and Max Weber" (1999, 111). Both Veblen and Weber were obsessed with the meaning of contemporary industrial society—the issues of power, management, and surplus

…

United States, among others, it resurrected Smith and transformed him into a whole new classical man. Despite efforts to renounce the new capitalist model by Thorstein Veblen and other institutionalists, the critics were effectively countered, especially by Max Weber. The neoclassical paradigm stood tall, ready to make contributions to the new scientific

…

: Macmillan. Diggins, John Patrick. 1996. Max Weber: Politics and the Spirit of Tragedy. New York: Basic Books. . 1999. Thorstein Veblen, Theorist of the Leisure Class. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Dorfman, Joseph. 1934. Thorstein Veblen and His America. New York: Augustus M. Kelley. Downs, Robert B. 1983. Books That Changed the World. 2d ed

…

. New York: Augustus M. Kelley. Johnson, Elizabeth, and Harry G. Johnson. 1978. The Shadow of Keynes. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Jorgensen, Elizabeth, and Henry Jorgensen. 1999. Thorstein Veblen: Victorian Firebrand. Armonk, NY: M.E. Shaipe. Jouvenel, Beitrand de. 1999. Economics and the Good Life: Essays on Political Economy, ed. Dennis Hale and Marc

The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class

by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett · 14 May 2017 · 550pp · 89,316 words

very greatly excelling the latter in intrinsic beauty of grain or color, and without being in any appreciable degree superior in point of mechanical serviceability. —Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) In the 1920s, Muriel Bristol attended a summer’s afternoon tea party in Cambridge, UK. A number of

…

.5 THE THEORY OF THE LEISURE CLASS Perhaps no one captured and articulated the social significance of consumption better than the social critic and economist Thorstein Veblen. Written in the late 1800s, Veblen’s polemic treatise The Theory of the Leisure Class is the defining text that precisely expresses the relationship between

…

, the fashionable behaviour. Even their vices and follies are fashionable. —Adam Smith The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1790) In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Thorstein Veblen observed that conspicuous consumption was also practiced among those outside of the rich, or what he called the “impecunious classes.” These poorer strata of society

…

or just on average with the rest of the country on social memberships. CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION IN CITIES Mills, like his contemporary John Kenneth Galbraith, and Thorstein Veblen before, was concerned about the social ramifications of concentrated wealth and its various signals. The pernicious and less obvious examples are those of secret social

…

to engage in conspicuous production, conspicuous leisure, and inconspicuous consumption, all of which produce much greater class stratification effects than the acquisition of material goods. Thorstein Veblen believed that conspicuous leisure would decline while conspicuous consumption would increase at a rapid pace among the rich and nouveau riche. He could not have

…

boutiques of Paris. The limitations of my landscape are due to the data at hand, but the expanse of these phenomena is in evidence worldwide. Thorstein Veblen’s view of consumption in the nineteenth century still applies today, but society and class are far more complicated. Many of us have access to

…

the new consumer (1st ed.). New York: Basic Books. Scott, A. (2005). Hollywood: The place, the industry. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Seckler, D. W. (1975). Thorstein Veblen and the institutionalists: A study in the social philosophy of economics. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press. Second wind. (2014, June 14). Economist: Schumpeter. Retrieved from

Sabotage: The Financial System's Nasty Business

by Anastasia Nesvetailova and Ronen Palan · 28 Jan 2020 · 218pp · 62,889 words

to the ideas of a school of thought, often ignored nowadays, known as the old institutional economics (OIE). Most famously associated with the works of Thorstein Veblen and John R. Commons, this body of scholarship developed in the early years of the twentieth century in the USA, a time when American capitalism

…

have found a euphemism for ‘sabotage’, then? A less offensive term to describe a core technique of moneymaking in finance? We suggest not. It was Thorstein Veblen, a father of an important school of thought in economics,1 who first introduced sabotage as a core economic concept. ‘Sabotage,’ he noted, ‘is a

…

rivals or to secure their own advantage.3 Veblen believed that in this expanded meaning the term ‘sabotage’ captured an important dimension of modern business. Thorstein Veblen is a controversial figure in the history of economic thought. His writing style is archaic, quite convoluted and always political. His legacy is mostly associated

…

theories are rarely taught in university programmes; global search engines yield many more results for ‘John Maynard Keynes’ and ‘John Commons’ than they do for ‘Thorstein Veblen’. Yet in the wake of the 2007–9 crisis, and in light of the revelations of the Panama and Paradise dossiers and the like, one

…

, innovating new products if he sees a profit to doing so, strategically misrepresenting his private information if this is profitable.’10 THE BUSINESS WORLD OF THORSTEIN VEBLEN So, how do businesses make money in competitive markets? Through sabotage, was a bold answer Veblen offered to a question that few had asked in

…

competition and unscrupulous predatory tactics.’12 In short, what the captains of industry were experts in was sabotage. KNOWLEDGE, POWER AND OTHER PEOPLE’S MONEY Thorstein Veblen was not a friend of the financial industry. If he was critical of the new capitalists of his day generally, he was specifically hostile to

…

crisis: BCG’, 2 March 2017, www.reuters.com/article/us-banks-fines/banks-paid-321-billion-in-fines-since-financial-crisis-bcg-idUSKBN1692Y2. Riesman, D., Thorstein Veblen, Transaction Publishers, 1953. Robinson, E., and M. Montijano, ‘Santander’s Ana Botin has something to prove’, Bloomberg, 23 November 2015, www.bloomberg.com/news/features

…

. Sabotage in the Financial System 1. The school is known as evolutionary economics or old institutional economics. It is associated primarily with the works of Thorstein Veblen and John R. Commons. For broad discussion of the old school of evolutionary economics see: J. Hodgson, The Evolution of Institutional Economics, Routledge, 2004, and

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

the ancients, but perhaps its most influential version today is the notion of ‘conspicuous consumption’, a term made famous just over a century ago by Thorstein Veblen in his critique of the American rich and their flashy display of luxury.21 Since people want to be loved and admired, such luxury enjoyed

…

music-hall’ were the cultural byproducts of imperialism and inequality. The lower classes aped the manners of financiers and aristocrats; Hobson admired the American economist Thorstein Veblen, who who had attacked the luxurious lifestyles of the American rich as a form of social waste, and would meet him in Washington, DC, in

…

of goods around 1900 disrupted established codes of status. Accumulation and display were a way to reassert social hierarchies. In 1899, the heterodox Chicago economist Thorstein Veblen christened this phenomenon ‘conspicuous consumption’. In his Theory of the Leisure Class, he focused primarily on the super-rich and their use of costly entertainments

…

’ existence. Interestingly, American houses stopped growing in the 2000s, in spite of dizzying bonuses and escalating inequality. Many observers continue to take their inspiration from Thorstein Veblen, the great critic of ‘conspicuous consumption’ in America a century ago, whom we met earlier. Veblen’s moral outrage about the wastefulness of elite leisure

…

, Understanding Consumption (Oxford, 1992); Herbert A. Simon, Models of Bounded Rationality (Cambridge, MA, 1982); and D. Southerton A. Ulph, eds., Sustainable Consumption (Oxford, 2014). 21. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions (New York, 1899/1953). 22. For this emerging field, see, e.g., Jukka Gronow

…

: Cornhill Magazine, 36 (July 1877), repr. in The Novels and Tales of Robert Louis Stevenson (1895 edn), 73; emphasis in original. 25. This applies to Thorstein Veblen as well, whose theory of the idle rich ignored the hard-working Rockefellers and more thrifty members of the elite. For a more balanced picture

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

in the United States appeared due for a turn in the latter direction, the direction of the institutionalists. The institutionalist of most durable fame was Thorstein Veblen, author of acid critiques of capitalism that are still in print and coiner of such durable terms as “conspicuous consumption” and “technocracy.” Veblen had studied

…

Reserve System—were the work of lawyers, bankers, and other practical sorts, not economists. The institutional economists envisioned themselves as technocrats, the business engineers that Thorstein Veblen argued would steer the economy more rationally than profit-driven “absentee owners” could.14 It’s hard to run a technocracy without a technology, though

…

the most famous economist of the twentieth century. What was this Keynesianism? In part, it was a critique of free market verities that surpassed even Thorstein Veblen’s in its stinging mockery. “Professional investment,” Keynes wrote in a famous passage of his 1936 classic, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

…

of orthodox economic theory had long been that its assumptions were unrealistic, that man was not really “a lightning calculator of pleasures and pains,” as Thorstein Veblen put it in 1898.5 Friedman’s gloriously liberating reply in 1953 was, So what!? [T]he relevant question to ask about the “assumptions” of

…

of independent shop owners and entrepreneurs seemed laughable to most of America’s intellectuals. The mockery had begun at the turn of the century with Thorstein Veblen’s tirades against free market economists and the capitalists they celebrated.13 It continued less caustically in Berle and Means’s book, and achieved more

…

me.” David Hume, The Philosophical Works of David Hume, vol. 4, sec. 4, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding” (Aalen, Germany: Scientia Verlag, 1964), 30. 8. Thorstein Veblen, “Fisher’s Capital and Income,” Political Science Quarterly (March 1908): 112. 9. Lucy Sprague Mitchell, Two Lives: The Story of Wesley Clair Mitchell and Myself

…

Economy 29 (1997): 3. Reprinted in Wesley Clair Mitchell, The Backward Art of Spending Money (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1999), ix–xxxv. 14. Thorstein Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System (New York: Viking, 1921). 15. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (San Diego: Harcourt

…

York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1946). 4. Milton Friedman, “Wesley C. Mitchell as Economic Theorist,” Journal of Political Economy (Dec. 1950): 465–93. 5. Thorstein Veblen, “Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (July 1898). Reprinted in Veblen, The Place of Science in Modern Civilisation and Other

The Power Elite

by C. Wright Mills and Alan Wolfe · 1 Jan 1956 · 568pp · 174,089 words

power. Perhaps that is what has happened to the local societies and metropolitan 400’s of the United States. In his theory of American prestige, Thorstein Veblen, being more interested in psychological gratification, tended to overlook the social function of much of what he described. But prestige is not merely social nonsense

…

of 1940. Cf. Baltzell Jr., op. cit. Table 2. 16. See ibid. Table 14, pp. 89 ff. 17. Wecter, op. cit. pp. 235, 234. 18. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899 (New York: New American Library, Mentor Edition, 1953), p. 162. Cf. also my Introduction to that edition for

…

drawn upon Harold Nicolson’s The Meaning of Prestige (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1937). 34. Gustave Le Bon, op. cit. p. 140. 35. Cf. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899 (New York: New American Library, Mentor Edition, 1953). 36. Cf. John Adams, Discourses on Davila (Boston: Russell and

…

. Time, 2 June 1952, pp. 21–2. 25. Business Week, 15 August 1954. 26. ‘You’ll Never Get Rich,’ Fortune, March 1938, p. 66. 27. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Macmillan, 1898;, pp. 247–9. 28. H. Irving Hancock, Life at West Point (New York: Putnam, 1903

…

consumption’ and ‘conspicuous waste.’ For America, and for the second generation of the period of which he wrote, he was generally correct. * A word about Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) which—fortunately—is still read, not because his criticism of the American upper class is still adequate

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

up to, without accounting for folly, cruelty, sex, friendship, credulity and the general rough and tumble of our crazy lives. The renegade economist and thinker Thorstein Veblen was an extraterrestrial of a different kind. He too perched himself outside the normal range of human experience, but this enabled him to sit far

…

and Nicholas Shaxson, ‘The Finance Curse: how oversized financial centres attack democracy and corrupt economies’, Tax Justice Network, May 2013. 1 Sabotage 1. Nils Gilman, ‘Thorstein Veblen’s neglected feminism’, Journal of Economic Issues, September 1999. 2. Cited in Sidney Plotkin and Rick Tilman, The Political ideas of

…

Thorstein Veblen, p.16. The friend was a professor called Jacob Warshaw. 3. As Matthew Watson of Warwick University put it, Leisure Class was in a sense

…

books; it raises barely a stir in the collective consciousness of contemporary economists.’ Watson sent me these comments via email, 2016. See also Matthew Watson, ‘Thorstein Veblen, The Thinker Who Saw Through the Competitiveness Agenda’, foolsgold.international, 29 February 2016, to be posted on financecurse.org. 4. William Heath Robinson was a

…

Finance Curse: how oversized financial centres attack democracies and corrupt economies’. This present book is substantially the fruit of those earlier pieces of work. 38. Thorstein Veblen, who once asked a student to assess the value of her church to her in terms of kegs of beer, would have understood the problem

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

The Trouble With Brunch: Work, Class and the Pursuit of Leisure

by Shawn Micallef · 10 Jun 2014 · 104pp · 34,784 words

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

Utopias: A Brief History From Ancient Writings to Virtual Communities

by Howard P. Segal · 20 May 2012 · 299pp · 19,560 words

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

The Day the World Stops Shopping

by J. B. MacKinnon · 14 May 2021 · 368pp · 109,432 words

Class Acts: Service and Inequality in Luxury Hotels

by Rachel Sherman · 18 Dec 2006 · 380pp · 153,701 words

The Googlization of Everything:

by Siva Vaidhyanathan · 1 Jan 2010 · 281pp · 95,852 words

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by Giles Slade · 14 Apr 2006 · 384pp · 89,250 words

The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics

by Christopher Lasch · 16 Sep 1991 · 669pp · 226,737 words

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1997 · 1,106pp · 335,322 words

Who Rules the World?

by Noam Chomsky

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

World Economy Since the Wars: A Personal View

by John Kenneth Galbraith · 14 May 1994 · 293pp · 91,412 words

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages

by Carlota Pérez · 1 Jan 2002

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

A Beautiful Mind

by Sylvia Nasar · 11 Jun 1998 · 998pp · 211,235 words

Debunking Economics - Revised, Expanded and Integrated Edition: The Naked Emperor Dethroned?

by Steve Keen · 21 Sep 2011 · 823pp · 220,581 words

Uneasy Street: The Anxieties of Affluence

by Rachel Sherman · 21 Aug 2017 · 360pp · 113,429 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

The Wisdom of Frugality: Why Less Is More - More or Less

by Emrys Westacott · 14 Apr 2016 · 287pp · 80,050 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations

by Christopher Lasch · 1 Jan 1978

The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times

by Giovanni Arrighi · 15 Mar 2010 · 7,371pp · 186,208 words

Journey to the Edge of Reason: The Life of Kurt Gödel

by Stephen Budiansky · 10 May 2021 · 406pp · 108,266 words

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

How the Mind Works

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 1997 · 913pp · 265,787 words

Capital Without Borders

by Brooke Harrington · 11 Sep 2016 · 358pp · 104,664 words

Ellul, Jacques-The Technological Society-Vintage Books (1964)

by Unknown · 7 Jun 2012

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by Benjamin R. Barber · 1 Jan 2007 · 498pp · 145,708 words

Framing Class: Media Representations of Wealth and Poverty in America

by Diana Elizabeth Kendall · 27 Jul 2005 · 311pp · 130,761 words

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

by Arlie Russell Hochschild · 5 Sep 2016 · 435pp · 120,574 words

The End of Work

by Jeremy Rifkin · 28 Dec 1994 · 372pp · 152 words

Work in the Future The Automation Revolution-Palgrave MacMillan (2019)

by Robert Skidelsky Nan Craig · 15 Mar 2020

Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess

by Robert H. Frank · 15 Jan 1999 · 416pp · 112,159 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

Milton Friedman: A Biography

by Lanny Ebenstein · 23 Jan 2007 · 298pp · 95,668 words

Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Achieving Financial Independence: Revised and Updated for the 21st Century

by Vicki Robin, Joe Dominguez and Monique Tilford · 31 Aug 1992 · 426pp · 115,150 words

In Pursuit of Privilege: A History of New York City's Upper Class and the Making of a Metropolis

by Clifton Hood · 1 Nov 2016 · 641pp · 182,927 words

Unsustainable Inequalities: Social Justice and the Environment

by Lucas Chancel · 15 Jan 2020 · 191pp · 51,242 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon · 2 Nov 2009 · 918pp · 260,504 words

The Coke Machine: The Dirty Truth Behind the World's Favorite Soft Drink

by Michael Blanding · 14 Jun 2010 · 385pp · 133,839 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

In the Age of the Smart Machine

by Shoshana Zuboff · 14 Apr 1988

What's Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live

by Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers · 2 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 80,925 words

Aftershock: The Next Economy and America's Future

by Robert B. Reich · 21 Sep 2010 · 147pp · 45,890 words

Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time

by Brigid Schulte · 11 Mar 2014 · 455pp · 133,719 words

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

Having and Being Had

by Eula Biss · 15 Jan 2020 · 199pp · 61,648 words

Willful: How We Choose What We Do

by Richard Robb · 12 Nov 2019 · 202pp · 58,823 words

Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control

by Stuart Russell · 7 Oct 2019 · 416pp · 112,268 words

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by Branko Milanovic · 9 Oct 2023

On Paradise Drive: How We Live Now (And Always Have) in the Future Tense

by David Brooks · 2 Jun 2004 · 262pp · 79,469 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 2002 · 901pp · 234,905 words

More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources – and What Happens Next

by Andrew McAfee · 30 Sep 2019 · 372pp · 94,153 words

Do Nothing: How to Break Away From Overworking, Overdoing, and Underliving

by Celeste Headlee · 10 Mar 2020 · 246pp · 74,404 words

The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Metropolitan Elite

by Michael Lind · 20 Feb 2020

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism

by Eric Hobsbawm · 5 Sep 2011 · 621pp · 157,263 words

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

E=mc2: A Biography of the World's Most Famous Equation

by David Bodanis · 25 May 2009 · 349pp · 27,507 words

What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry

by John Markoff · 1 Jan 2005 · 394pp · 108,215 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception

by George A. Akerlof, Robert J. Shiller and Stanley B Resor Professor Of Economics Robert J Shiller · 21 Sep 2015 · 274pp · 93,758 words

Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places

by Sharon Zukin · 1 Dec 2009 · 415pp · 119,277 words

Carjacked: The Culture of the Automobile and Its Effect on Our Lives

by Catherine Lutz and Anne Lutz Fernandez · 5 Jan 2010 · 269pp · 104,430 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

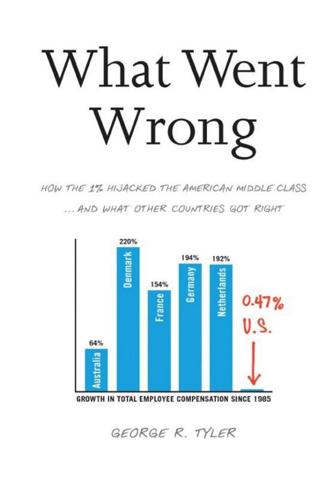

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Pity the Billionaire: The Unexpected Resurgence of the American Right

by Thomas Frank · 16 Aug 2011 · 261pp · 64,977 words

Work Less, Live More: The Way to Semi-Retirement

by Robert Clyatt · 28 Sep 2007

Cities: The First 6,000 Years

by Monica L. Smith · 31 Mar 2019 · 304pp · 85,291 words

Because We Say So

by Noam Chomsky

Shadow Work: The Unpaid, Unseen Jobs That Fill Your Day

by Craig Lambert · 30 Apr 2015 · 229pp · 72,431 words

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by Richard Florida · 9 May 2016 · 356pp · 91,157 words

With Liberty and Dividends for All: How to Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don't Pay Enough

by Peter Barnes · 31 Jul 2014 · 151pp · 38,153 words

Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own

by Garett Jones · 15 Feb 2015 · 247pp · 64,986 words

New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI

by Frank Pasquale · 14 May 2020 · 1,172pp · 114,305 words

No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Apr 2015 · 324pp · 93,606 words

The Digital Divide: Arguments for and Against Facebook, Google, Texting, and the Age of Social Netwo Rking

by Mark Bauerlein · 7 Sep 2011 · 407pp · 103,501 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility

by Zack Furness and Zachary Mooradian Furness · 28 Mar 2010 · 532pp · 155,470 words

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by John Markoff · 24 Aug 2015 · 413pp · 119,587 words

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by Duff McDonald · 24 Apr 2017 · 827pp · 239,762 words

Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?

by Thomas Geoghegan · 20 Sep 2011 · 364pp · 104,697 words

The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window Into Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 10 Sep 2007 · 698pp · 198,203 words

The Light That Failed: A Reckoning

by Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes · 31 Oct 2019 · 300pp · 87,374 words

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by David G. Blanchflower · 12 Apr 2021 · 566pp · 160,453 words

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by Jan Lucassen · 26 Jul 2021 · 869pp · 239,167 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Hacking Capitalism

by Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman

by Timothy Ferriss · 1 Dec 2010 · 836pp · 158,284 words

The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

by David Callahan · 1 Jan 2004 · 452pp · 110,488 words

Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture

by Marvin Harris · 1 Dec 1974 · 206pp · 67,030 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy

by Robert W. McChesney · 5 Mar 2013 · 476pp · 125,219 words

The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett · 1 Jan 2009 · 309pp · 86,909 words

How Will Capitalism End?

by Wolfgang Streeck · 8 Nov 2016 · 424pp · 115,035 words

Energy: A Human History

by Richard Rhodes · 28 May 2018 · 653pp · 155,847 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life

by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky · 18 Jun 2012 · 279pp · 87,910 words

100 Years of Identity Crisis: Culture War Over Socialisation

by Frank Furedi · 6 Sep 2021 · 535pp · 103,761 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

The Computer Boys Take Over: Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Technical Expertise

by Nathan L. Ensmenger · 31 Jul 2010 · 429pp · 114,726 words

The New Elite: Inside the Minds of the Truly Wealthy

by Dr. Jim Taylor · 9 Sep 2008 · 256pp · 15,765 words

Affluenza: When Too Much Is Never Enough

by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss · 31 May 2005

Head, Hand, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect

by David Goodhart · 7 Sep 2020 · 463pp · 115,103 words

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 22 Oct 2018 · 402pp · 126,835 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?

by Thomas Frank · 15 Mar 2016 · 316pp · 87,486 words

Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There

by David Brooks · 1 Jan 2000 · 142pp · 18,753 words

The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 1 Jan 2010 · 369pp · 94,588 words

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by Matt Ridley · 395pp · 116,675 words

The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story

by Michael Lewis · 29 Sep 1999 · 146pp · 43,446 words

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by Guy Standing · 13 Jul 2016 · 443pp · 98,113 words

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

by Tom Wolfe · 1 Jan 1968 · 224pp · 91,918 words

GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

by Diane Coyle · 23 Feb 2014 · 159pp · 45,073 words

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

by Joshua B. Freeman · 27 Feb 2018 · 538pp · 145,243 words

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by Jeremy Lent · 22 May 2017 · 789pp · 207,744 words

Interventions

by Noam Chomsky

Culture works: the political economy of culture

by Richard Maxwell · 15 Jan 2001 · 268pp · 112,708 words

Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest

by Zeynep Tufekci · 14 May 2017 · 444pp · 130,646 words

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by John Kay · 24 May 2004 · 436pp · 76 words

Servants: A Downstairs History of Britain From the Nineteenth Century to Modern Times

by Lucy Lethbridge · 18 Nov 2013 · 457pp · 128,640 words

Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City

by Peter D. Norton · 15 Jan 2008 · 409pp · 145,128 words

Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making

by David Rothkopf · 18 Mar 2008 · 535pp · 158,863 words

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks (Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global Enterprise)

by Andrew L. Russell · 27 Apr 2014 · 675pp · 141,667 words

Future Tense: Jews, Judaism, and Israel in the Twenty-First Century

by Jonathan Sacks · 19 Apr 2010 · 305pp · 97,214 words

This Will Make You Smarter: 150 New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking

by John Brockman · 14 Feb 2012 · 416pp · 106,582 words

The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance

by Henry Petroski · 2 Jan 1990 · 490pp · 150,172 words

World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech

by Franklin Foer · 31 Aug 2017 · 281pp · 71,242 words

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

by Richard Heinberg · 1 Jun 2011 · 372pp · 107,587 words

Paper Money Collapse: The Folly of Elastic Money and the Coming Monetary Breakdown

by Detlev S. Schlichter · 21 Sep 2011 · 310pp · 90,817 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

The Sirens' Call: How Attention Became the World's Most Endangered Resource

by Chris Hayes · 28 Jan 2025 · 359pp · 100,761 words

The Gated City (Kindle Single)

by Ryan Avent · 30 Aug 2011 · 112pp · 30,160 words

When Einstein Walked With Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

by Jim Holt · 14 May 2018 · 436pp · 127,642 words

What to Think About Machines That Think: Today's Leading Thinkers on the Age of Machine Intelligence

by John Brockman · 5 Oct 2015 · 481pp · 125,946 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

Different: Escaping the Competitive Herd

by Youngme Moon · 5 Apr 2010 · 221pp · 64,080 words

Why We Can't Afford the Rich

by Andrew Sayer · 6 Nov 2014 · 504pp · 143,303 words

The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain

by Brett Christophers · 6 Nov 2018

The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

by David Deutsch · 30 Jun 2011 · 551pp · 174,280 words

The End of Growth

by Jeff Rubin · 2 Sep 2013 · 262pp · 83,548 words

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by Jaron Lanier · 21 Nov 2017 · 480pp · 123,979 words

Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences

by Edward Tenner · 1 Sep 1997

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by Charles Handy · 12 Mar 2015 · 164pp · 57,068 words

If You're So Smart, Why Aren't You Happy?

by Raj Raghunathan · 25 Apr 2016 · 505pp · 127,542 words

The God Delusion

by Richard Dawkins · 12 Sep 2006 · 478pp · 142,608 words

Status Anxiety

by Alain de Botton · 1 Jan 2004 · 187pp · 58,839 words

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by Philip Coggan · 6 Feb 2020 · 524pp · 155,947 words

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by Scott E. Page · 27 Nov 2018 · 543pp · 153,550 words

This Is Not Normal: The Collapse of Liberal Britain

by William Davies · 28 Sep 2020 · 210pp · 65,833 words

Servant Economy: Where America's Elite Is Sending the Middle Class

by Jeff Faux · 16 May 2012 · 364pp · 99,613 words

Busy

by Tony Crabbe · 7 Jul 2015 · 254pp · 81,009 words

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by Roger Scruton · 16 Nov 2017 · 190pp · 56,531 words

Unacceptable: Privilege, Deceit & the Making of the College Admissions Scandal

by Melissa Korn and Jennifer Levitz · 20 Jul 2020 · 520pp · 134,627 words

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Video Games Conquered Pop Culture

by Harold Goldberg · 5 Apr 2011 · 329pp · 106,831 words

Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 1 Jan 2004 · 475pp · 149,310 words

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 Apr 2005 · 339pp · 95,988 words

The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth Is Unattainable and the Global Economy Is in Peril

by Satyajit Das · 9 Feb 2016 · 327pp · 90,542 words

Utopia for Realists: The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-Hour Workweek

by Rutger Bregman · 13 Sep 2014 · 235pp · 62,862 words

Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals

by Robert M. Pirsig · 1 Jan 1991 · 497pp · 146,551 words

The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

by Tim Sullivan · 6 Jun 2016 · 252pp · 73,131 words

Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers

by Tom Wolfe · 1 Jan 1970

Democracy Incorporated

by Sheldon S. Wolin · 7 Apr 2008 · 637pp · 128,673 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

Decline of the English Murder

by George Orwell · 24 Jul 2009 · 96pp · 33,963 words

Philanthrocapitalism

by Matthew Bishop, Michael Green and Bill Clinton · 29 Sep 2008 · 401pp · 115,959 words

Ayn Rand and the World She Made

by Anne C. Heller · 27 Oct 2009 · 756pp · 228,797 words

Labyrinths

by Jorge Luis Borges, Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby, William Gibson and André Maurois · 1 Jan 1962 · 276pp · 91,719 words

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by James C. Scott · 8 Feb 1999 · 607pp · 185,487 words

Bullshit Jobs: A Theory

by David Graeber · 14 May 2018 · 385pp · 123,168 words

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

Stuffocation

by James Wallman · 6 Dec 2013 · 296pp · 82,501 words

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

The Stolen Year

by Anya Kamenetz · 23 Aug 2022 · 347pp · 103,518 words

Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them

by Donovan Hohn · 1 Jan 2010 · 473pp · 154,182 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Life as a Passenger: How Driverless Cars Will Change the World

by David Kerrigan · 18 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 80,835 words

Elsewhere, U.S.A: How We Got From the Company Man, Family Dinners, and the Affluent Society to the Home Office, BlackBerry Moms,and Economic Anxiety

by Dalton Conley · 27 Dec 2008 · 204pp · 67,922 words

Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand

by John Markoff · 22 Mar 2022 · 573pp · 142,376 words

The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions

by Greta Thunberg · 14 Feb 2023 · 651pp · 162,060 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

The Art of Rest: How to Find Respite in the Modern Age

by Claudia Hammond · 5 Dec 2019 · 249pp · 81,217 words