Urban Transport Without the Hot Air, Volume 1

by

Steve Melia

Journal of the American Planning Association. 76 (3), pp. 265-94. 10 Summary: myths, values and challenges 267 See for example the government’s definition of ‘sustainable development’ within (2012) ‘National planning policy framework’. On: www.gov.uk. 268 Goodall, Chris (2013) Sustainability – all that matters. Abingdon: Hodder Education. 11 Four options for traffic in towns 269 Buchanan, C., Douglas (1964) Traffic in towns: The specially shortened edition of the Buchanan report. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 270 DfT (2012) ‘Transport statistics Great Britain’, Table VEH0153, divided by midyear population statistics from: ONS (2011) ‘Mid-1971 to Mid-2010 Population Estimates: United Kingdom; estimated resident population for constituent countries and regions’.

…

Buchanan used the image of the Penn Center in Philadelphia to illustrate the potential for this (Figure 11.3). Note the different levels on which pedestrians and vehicles of different kinds can access the buildings. Figure 11.3 Penn Center, Philadelphia, taken from ‘Traffic in towns’ (Buchanan report, 1961) Multi-level vehicular access has been tried in many places around the world since then (think of major airport terminals, for example), but it was never going to provide a general solution to the problem of traffic in towns. Elevated roads damage urban environments and reduce neighbouring property values; they are also expensive to build and maintain. Burying roads may have advantages in some circumstances but will always be constrained by cost.

…

If ‘restraint’ appears to imply life getting worse, there are ways that restraining traffic can improve people’s quality of life, particularly in dense urban areas, where more of us are likely to be living in future. Those are some of the challenges. Part II will look at potential solutions, starting with some proposed over 50 years ago. In 1960, the transport minister Ernest Marples set up a committee to write the report ‘Traffic in towns’, which became an unlikely paperback success.269 The Buchanan report, as it became known was written at a time of transition, and of expectation. It began with an uncannily prescient forecast of future car ownership (see Figure 11.1) and its consequences. This “rising tide of cars”, it predicted, “will not put a stop to itself until it has almost put a stop to the traffic.”

Are Trams Socialist?: Why Britain Has No Transport Policy

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 19 May 2016

Wheels Within Wheels: A Study of the Roads Lobby, p. 36.Routledge & Kegan Paul. Bagwell and Lyth (2002, p. 94). Quoted in C. Reid (2015, p. 58). House of Commons Debates, 9 May 1977, volume 931,983. C. Buchanan. 1963. Traffic in Towns: A Study of the Long Term Problems of Traffic in Urban Areas, p. 47. Penguin Special Edition. Preface to Buchanan (1963, p. 10). See Buchanan (1963, p. 62). British Road Federation. 1963. Towns and Cities, p. 12. British Road Federation. See Hamilton and Potter (1985, p. 87). Public Record Office, CAB (Cabinet Office), 134/915. See Hamer (1987, p. 68).

…

However, on this planet, and particularly in urban areas, the space available for cars is not limitless. Indeed, it is highly constrained. The road lobby has, therefore, devoted the thrust of its efforts to trying to make it less constrained. The apogee of this line of thinking was the publication of the Buchanan Report – Traffic in Towns – in 1963. The motorways were beginning to tackle the inter-urban traffic jams that regularly hit the headlines, most notoriously on the Exeter bypass in the summer, but the roads in towns were becoming clogged and the congestion was unbearable. Even in relatively small towns, congestion, noise, accidents and fumes were making life in central areas intolerable and were driving people out to the suburbs, where the quality of life was seen as better.

…

More than a hundred local authorities drew up these land use transportation plans over the next decade, determining the nature of their town planning for a generation. In the event, the Buchanan Report could not be implemented because of its own internal contradictions. While many towns and cities still bear the hallmarks of failed attempts to worship at Buchanan’s altar, none could afford the full Monty. That would simply have required far too much spending in relation to the size of the area the roads would have served and raised the ire of too many local citizens. While the constraints of cost, political opposition and practicality prevented local authorities from adopting the Buchanan thinking in toto, many town centres – ranging in size from Burnley to Birmingham, Leicester to Luton – remain blighted to this day by half-implemented ‘Buchananization’, with ring roads, dual carriageways and even odd short stretches of motorway creating soulless car-oriented environments that encourage motor vehicles to enter city centres or speed through them, cutting cities in half as decisively as the Berlin wall.

Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain

by

John Grindrod

Published 2 Nov 2013

Wood and Company (London) and Chesshire, Gibson and Company (Birmingham) 46 Professor Colin Buchanan, The Times, 19/9/66, p9 47 Geoffrey Moorhouse, The Other England, Penguin, 1964, p93 48 Joseph Minogue, Guardian, 27/3/62, p8 49 Rodney Gordon in John Gold, The Practice of Modernism, Routledge, 2007, p115 50 Rodney Gordon in Elain Harwood and Alan Powers, The Sixties, The Twentieth Century Society, 2002, p78 51 Rodney Gordon in Elain Harwood and Alan Powers, The Sixties, The Twentieth Century Society, 2002, p75 52 Guardian 3/11/77, p18 53 George Perkin, Concrete Quarterly, October-December 1970, p40 54 Sam Chippindale, Architects’ Journal, 19/1/61, p97 55 Diana Rowntree, Guardian, 29/5/64, p10 56 Jan Morris, The Times, 15/1/76, p13 57 Neville Borg, Birmingham Chief Engineer in John Holliday, ed, City Centre Redevelopment, Charles Knight, 1973, p49 58 Colin Buchanan, Guardian, 28/9/70, p7 59 Colin Buchanan, Traffic in Towns, Penguin, 1964, p37 60 ‘Must Britain be a Mess?’ 4, Observer 19/6/60, p19 61 ‘Must Britain be a Mess?’ 4, Observer 19/6/60, p19 62 W. Konrad Smigielski in John Holliday, ed, City Centre Redevelopment, Charles Knight, 1973, p154 63 Colin Buchanan, Traffic in Towns, Penguin, 1964, p32 64 Peter and Alison Smithson, Ordinariness and Light, Faber, 1970, p66 65 Wilfred Burns, British Shopping Centres, Leonard Hill, 1959, p105-6 66 G.

…

Within two decades the average traffic speed in Glasgow centre had shot up to a pulse-quickening 50 miles per hour.6 Not everybody was delighted with these developments. ‘Parked and moving vehicles obscure the scene day and night,’ wrote Professor Colin Buchanan, a traffic planning specialist, in The Times.7 ‘A generally hideous array of signals, beacons, signs, railings, petrol stations, sales depots and advertisements has come into being.’ His report for the government, Traffic in Towns, became a bestseller in 1963. At a town planning conference in 1966 he described the negative effects of the car with a bleak Reggie Perrin-like howl of despair: ‘confusion and congestion, delays, lack of parking space, inadequate facilities for loading and unloading goods, and the same sad story of death and injury, anxiety, noise, fumes, and the large-scale intrusion of the motor vehicle into the visual scene’.8 Yet if the nation’s roads were a mess, there was at least one development that injected a dose of elegance, coherence and practicality into the motoring scene.

…

One of the most ambitious schemes was the superhuman speculative shopping megastructure named High Market. It had been sponsored by the glass manufacturers Pilkington Brothers, and drawn up by yet another husband and wife team, Gordon and Eleanor Michell (who had advised Colin Buchanan while he was writing Traffic in Towns). The Michells imagined an artificial ridge stretching between two hills in the countryside near Dudley in the Midlands, creating what was effectively a dam of shops. ‘It would be approached by helicopter or high-speed monorail, as well as by high-speed roads,’ wrote Wilfred Burns.

How Cycling Can Save the World

by

Peter Walker

Published 3 Apr 2017

These were people like Robert Moses, the “master builder” of New York City, whose automobile-dominated idea of urban life was hugely influential both across the US and elsewhere. His British near-equivalent was Professor Colin Buchanan, commissioned by the government in the early 1960s to investigate what could be done to stop towns and cities being choked by motor vehicles, the number of which had doubled in a decade. Buchanan’s eventual report, 1963’s Traffic in Towns, became something of a sensation, even being published as a paperback book that remains in print. Buchanan, a civil engineer and town planner, was by no means a disciple of the car, once describing motor traffic as a “destructive lava, welling out from the towns, searing and scorching in long channels, and ever-ready to invade new areas.”

…

CHAPTER 9 1 Interview with the author. 2 Interview with the author. 3 Interview with the author. 4 Josh Strauss and Peter Walker, “Visijax: ‘The Brightest Cycling Jacket You May Ever See’” (video), The Guardian, October 24, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/video/2012/oct/24/visijax-cycling-jacket-video. 5 Peter Walker, “The Cargo Bike—Somewhere Inbetween the Courier and the Truck,” The Guardian, May 2, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2012/may/02/cargo-bike-city-courier-truck. 6 Ibid. 7 Interview with the author. 8 Pete Jordan, In The City of Bikes: The Story of the Amsterdam Cyclist (New York: Harper Perennial), 2013. 9 “Ring a Bell? It’s Borrow-a-Bike Time Again . . . ,” Cambridge News, October 12, 2007, http://www.cambridge-news.co.uk/ring-bell-borrowabike-time/story-22461332-detail/story.html. 10 Interview with the author. 11 Interview with the author. 12 Interview with the author. 13 Colin Buchanan, Traffic in Towns: A Study of the Long Term Problems of Traffic in Urban Areas (London: H. M. Stationery Office), 1963. EPILOGUE 1 Carlton Reid, Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How Cyclists Were the First to Push for Good Roads & Became the Pioneers of Motoring (Washington, DC: Island Press), 2015. 2 Agence France-Presse, “Oslo Moves to Ban Cars from City Centre within Four Years,” The Guardian, October 19, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/oct/19/oslo-moves-to-ban-cars-from-city-centre-within-four-years. 3 “Swedish Capital to Go Car Free in September,” The Local, July 20, 2015, http://www.thelocal.se/20150720/swedish-capital-to-go-car-free-for-a-day. 4 Adam Greenfield, “Helsinki’s Ambitious Plan to Make Car Ownership Pointless in 10 Years,” The Guardian, July 10, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/jul/10/helsinki-shared-public-transport-plan-car-ownership-pointless. 5 Stephen Moss, “End of the Car Age: How Cities Are Outgrowing the Automobile,” The Guardian, April 28, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/apr/28/end-of-the-car-age-how-cities-outgrew-the-automobile. 6 Interview with the author. 7 Interview with the author. 8 Interview with the author. 9 Interview with the author. 10 Interview with the author.

…

“We are nourishing at great cost a monster of great potential destructiveness,” he wrote vividly.13 But for all this, Buchanan clearly saw no alternative to the private car. His report was based entirely around ways to cope with more motor traffic, not whether there was a way to avoid it. This is not to Buchanan’s personal discredit. It was the era when more or less every arm of government was planning for a car-based future. Also in 1963 came an official report into Britain’s still-huge rail network by another famous technocrat, Sir Richard Beeching, which saw almost a third of the country’s rural train lines ripped up. But it is nonetheless notable to compare Buchanan’s vision of the future with that of Babu’s when it comes to cycling.

Last Trains: Dr Beeching and the Death of Rural England

by

Charles Loft

Published 27 Mar 2013

Its answers were only partially satisfactory and, before the remaining queries could be dealt with, the Association abandoned its plan to run a commuter service, precipitating the collapse of the whole effort under a wave of tarmac. Marples was fascinated by the prospect of rebuilding urban Britain to accommodate the motor car and was heavily influenced by Professor Colin Buchanan’s 1958 book Mixed Blessing: The Motor in Britain. He appointed Buchanan to produce a report, Traffic in Towns, published in November 1963, which put forward expensive proposals for reconstructing cities to cope with traffic. That such an approach appealed to Marples the construction magnate is unsurprising, but if he saw profits for his kind in such an approach, he was also genuinely inspired – like so many others – by dreams of a new, concrete Britain.

…

As the extent to which rail could attract freight from road would have only a marginal effect on the road programme, rail investment would continue to be judged on its likely rate of return. The second key issue Hall identified was urban traffic. Although it was the publication of Buchanan’s report on Traffic in Towns, in November 1963, that highlighted this problem publicly, the Transport and Housing ministries had begun laying the foundations of a joint group on traffic and urban planning in the spring of 1961. Hall’s report warned that ‘rail transport in the cities which have it is an asset which should not be lightly eroded’.195 The ministry had already taken this issue up with Beeching and suggested that it might wish to have advance consultation before urban services were proposed for closure.

…

1 British Elecricity Authority 1 British Rail (BR) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 evaluation of APT 1 studies commissioned by 1 British Railways Board (BRB) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 British Road Services 1 British Roads Federation (BRF) 1 British Transport Authority: proposed creation of 1 British Transport Commission (BTC) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 annual report of (1961) 1 closure of M&GN routes (1958) 1, 2 central charges of 1 finances of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 freight flow map produced by (1962) 1, 2 operating surpluses of 1 personnel of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Plan for the Modernisation and Re-equipment of British Railways (Modernisation Plan) (1955) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 proposed closure of Westerham Valley Railway (1960) 1 Railway Executive of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Reappraisal (1959) 1, 2 Road Haulage Executive (RHE) 1, 2, 3, 4 shortcomings of 1 British Transport Stock 1 Brooke, Henry 1, 2 Browne, John Francis Archibald (Baron Kilmaine) 1 Buchanan, Prof. Colin 1 Mixed Blessing: The Motor in Britain (1958) 1 Traffic in Towns (1963) 1, 2, 3 Butler, Rab 1 Butterfield, Peter 1 Cadbury, Major Edgar 1, 2 Callaghan, Jim 1 Carrington, Sir William 1 Carson, Rachel: Silent Spring (1962) 1 Casserley, H. C.: Service Suspended (1952) 1 Castle, Barbara 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 British Railways Network for Development (1967) 1, 2, 3, 4 Minister of Transport, 1, 2, 3 refusal for railway line closure consent (1966) 1 Central Electricity Generating Board 1 Central Transport Consultative Committee (CTCC) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 establishment of 1 introduction of diesel engines 1 personnel of 1, 2, 3, 4 Channel Tunnel 1 Chatham and Dover 1 Chesterford, Squire 1, 2 Churchill, Winston 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Clapham Junction Rail Crash (1988) 1 Clarke, Otto 1, 2, 3, 4 Conservative Party 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 electoral manifesto (1970) 1 Conservative Party electoral performance of (1959) 1 electoral performance of (1964) 1, 2 ideology of 1, 2 links to RHA 1 members of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 support for decentralisation 1 Cooper-Key, Neil 1 Council for the Protection of Rural England: ‘Inexpensive Progress’ (1992) 1 Cousins, Frank 1 Crichel Down Affair (1954) 1 Crosland, Anthony 1 Denning, Lord Alfred 1 Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) 1, 2 Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) 1 Road Research Laboratory (RRL) 1, 2 Department of the Environment 1 Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes, The 1, 2, 3, 4 Dodgson, John: Rail Problem, The (1975) 1 Douglas-Home, Sir Alec 1, 2, 3 Duddington, Joseph 1 Dunnett, James 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 East Kent Light Railway 1, 2, 3, 4 branches of 1 closure of 1, 2, 3, 4 finances of 1 Eastry Rural District Council 1 Economic and Financial Obligations of the Nationalised Industries (1961) 1 Eden, Anthony 1, 2 Fiennes, Gerard 1 First World War (1914–18) 1 impact on road haulage industry 1 Western Front 1 Forbes, James 1 Foster, Sir Christopher 1 Francis, Stewart 1 Franks, Sir Oliver 1 Fraser, Tom 1, 2, 3, 4 background of 1 Minister of Transport 1 opposition to closure of railway stations 1, 2 Freshwater, Yarmouth and Newport Railway 1 Galbraith, Tom 1 General Post Office 1 George, Sir John: Scottish Chairman of Conservative Party 1 Germany 1 Gilbert, Sir Bernard 1 Glancey, Jonathan 1 Glover, Kenneth 1, 2 Gourvish, Terry 1 Grand Central Association 1, 2 Grant, Alexander 1, 2, 3, 4 Great Central Line Railway 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 acquired by LNER 1 closure of (1966) 1, 2 Great Eastern Railway (GER) 1 railway lines of 1, 2 Great Western Line: Cameron Branch 1 Great Western Railway (GWR) 1 creation of (1921) 1 personnel of 1 railcars of 1, 2 railway lines of 1, 2 Greater London Council 1 Greene, Sid 1 Gresley, Nigel 1 Guillebaud, Claude 1, 2 statement to Parliament (1960) 1 Guillebaud Report 1 Gunter, Ray 1 Hailsham, Lord (Quinton Hogg) 1 Hall, Sir Robert 1 Hardy, Richard 1, 2 Harris, Nigel 1 Harrow and Wealdstone rail crash (1952) 1 Hastings, Douglas Macdonald 1, 2 Hatfield rail crash (2000) 1 Hay, Will: Oh, Mr Porter!

A History of British Motorways

by

G. Charlesworth

Published 1 Jan 1984

CHARLESWORTH G. London traffic management. Traffic engineering and contro~ 1962, 4, No. 2. 2. MARLOW M. and EVANS R. Urban congestion survey 1976. Traffic flows and speeds in eight towns and five conurbations. Digest SR 438. TRRL, Crowthorne, 1978. 209 A HISTORY OF BRITISH MOTORWAYS 3. BUCHANAN C.D. et al. Traffic in towns. Report of the Working Group. HMSO, London, 1963. 4. BRUNNER C.T. Cities-living with the motor vehicle. British Road Federation, London, 1960. 5. MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT Road pricing: the economic and technical possibilities. HMSO, London, 1964. 6. ROTH G.J. The equilibrium of traffic on congested streets.

…

Existing programmes would provide 1,000 miles of motorway and about the same mileage of all-purpose dual carriageway by the end of 1972. The Government concluded that if the expanded network could be completed in the next 15 to 20 years together with a programme of work on other trunk roads "real congestion on the inter-urban trunk road system as a whole could be virtually eliminated. " The problems of traffic in towns were coming increasingly to the forefront and transport planning surveys were being carried out in the major conurbations. The White Paper envisaged a change in the balance of expenditure between roads in rural and in urban areas in favour of urban road schemes. Summary The 1960s saw the largest road building programme ever started in Britain and at the end of the decade the inter-urban network of main routes had been substantially modernised by the construction of motorways and all-purpose dual carriageways.

…

Car speeds in urban areas 0/ Great Britain in 1976 (figures/or 1967 in brackets): kmlh Peak Off-peak Area Eight towns Five towns in conurbations Eight towns Five towns in conurbations Whole towns 34.0 (32.0) 38.0 (31.7) 29.5 (29.8) 33.7 (27.6) Central areas 25.0 (19.6) 21.4 (17.6) 20.8 (18.2) 20.4 (14.9) 181 A HISTORY OF BRITISH MOTORWAYS a panel set up in 1962 by the Minister of TransportS which examined the technical feasibility of various methods for improving the pricing system relating to the use of roads and relevant economic considerations. These studies were concerned with pricing related to the allocation of resources and not to taxation, i.e. to revenue raising, although taxation is a form of pricing. The use of pricing methods to obtain better allocation of traffic in town centres was favoured by several transport economists 6 and a considerable amount of research and development went into devising equipment for charging motorists on the basis of the congestion they caused. Politically the system was not acceptable in Britain where reliance has been placed, in effect, on parking control as a means oflimiting traffic in busy urban areas.

The Miracle Pill

by

Peter Walker

Published 21 Jan 2021

actin (protein) 40 active applause 176–7, 180, 271 Active Ten app (Public Health England) 57, 269 adenosine triphosphate (ATP) 40, 41, 276 Aldred, Rachel 119–20, 139 Alzheimer’s disease 5, 49, 186, 226, 232, 233, 234 Agricultural Revolution/Agrarian Revolution 15–16 Amager Bakke/Copenhill waste-burning energy plant, Denmark 134–5 Amish people 17–18, 208 anaerobic respiration 40 Annual Travel Survey 3 anxiety 5, 50, 57, 112 Araujo, Claudio Gil 229–32 Aspern, Vienna 140 asthma 10–11, 160, 172, 209 Atlas, Charles (Angelo Siciliano) 31 Barnet Graph of Doom 100–1 basal metabolic rate (BMR) 51, 158, 191 Better (non-profit social enterprise) 224 BeUpstanding 195–6 bike couriers 11–13 Biobank public health project 114 biophilia 133 Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) 132–5, 138–9 Blackburn, Elizabeth 41–2 Blair, Steven 19–20, 21, 46, 169–72, 275–6 blood pressure 5, 41, 46, 48, 57, 75, 90, 160, 225, 227, 265 Boardman, Chris 124–5, 127, 137, 264 BodPod 172–3, 174 body mass index (BMI) 146–7, 150–2, 161–4, 167, 170, 171, 172, 173, 193, 243 bone density/health 16–17, 22, 23, 44, 46, 49, 67, 101, 209, 223, 227–8 Boyd, Andrew 105–6 breast cancer 48, 160 British Medical Journal (BMJ) 64, 65, 80 Buchan, William: Domestic Medicine 63 Buchanan, Colin: Traffic in Towns 120–1 Buchanan, Nigel 203–4, 206, 207–8 Buchner, David 228 Bull, Fiona 98–9 Burden of Disease, WHO 47, 90 Burfoot, Amby 78, 79 Burnham, Andy 124, 264, 266 bus drivers, heart attack rates in London 61–2, 71–3 Bushy Park Time Trial 250 calories 13, 19–20, 19n, 27, 51, 54, 75, 113, 114, 146, 148, 153, 155, 156–7, 158, 165–6, 169, 190 Cambridge University 64, 65–6, 187 cancer 5, 41, 48–9, 62, 79, 90, 114, 160, 186, 187, 227, 231–2 car children and 216, 219, 258, 263–4, 265, 272 electric 137, 268 lobby 263 social engineering and 254, 258 town/city planning and 110, 111, 113, 121, 120–2, 124, 125, 126, 127–8, 129, 130, 131, 135, 136, 137, 138, 140, 141, 142, 191–2, 263, 265, 268 walking supplanted by 2, 3, 5, 53 cardiovascular activity 168–9, 209, 271–2 cardiovascular health bus drivers, heart attack rates in London 61–2, 71–3 children and 2, 213 coronavirus and 265 diabetes and 95 Harvard Alumni Health Study 75–7, 134 heart attacks 41, 48, 50, 62, 70, 71, 74, 75, 76, 77, 91, 92, 93, 106 heart disease 5, 43, 46, 48, 59, 68, 69, 70–4, 81, 82, 88, 89, 114, 152, 154, 243, 244 inactivity first linked to 47–8 life expectancy and 93 longshoremen health study, San Francisco 75 low-density lipoprotein (LDL)/triglycerides and 41, 43, 46, 185 mitochondria and 40, 41 rheumatic heart disease 68, 69–70, 82, 152 sitting and 5, 185, 186, 187, 199 Centers for Disease Control (US government) 95, 228 chair 178–9 Chan, Margaret 152–3 children 22–3, 203–20, 235 adult health, movement in childhood and 11, 209–10 BMI and 51 bone density and 16, 23, 49, 67, 209–10 childhood movement diminishing into adolescence and onwards 11, 210–11 cycling and 121, 130, 214, 237–8, 246, 247 Daily Mile and 203–7, 212–13 decline in activity/inactivity statistics 1–2, 10–11, 22–3, 24, 203–11, 252–3, 254, 256 girls, low activity levels in 141–3, 204, 209, 210–11, 256 independent childhood mobility, perceived cosseting of children and 216–20 life expectancy and 97 obesity and 84, 152, 153, 252–3, 256–7 schools and see schools social care and 100 social engineering and 244, 245, 246, 247–9, 252–3 town/city planning and 121, 122–3, 130, 138, 139–40, 142, 216–20 cholesterol 43, 185, 242–3 cigarettes 10, 29, 47, 62, 75, 76, 79, 92, 98, 105, 176, 177, 242–4 cognitive function 5, 46, 49, 57, 87, 186, 226, 232, 233, 234 Coldbath Fields Prison, London 63–4 colon cancer 48 co-morbidity 89, 91 commuting 58, 111, 114–18, 125, 127–9, 148, 183, 184, 199–200, 221, 270, 273, 274 Cooper, Ashley 129 Cooper, Ken: Aerobics 78, 79 Copenhagen, Denmark 109–12, 122–3, 125, 134, 135, 184, 240 Coronary Heart Disease and Physical Activity of Work 61–2, 71–3 coronavirus pandemic 8–10, 13, 33, 88, 90, 100, 115, 116, 130, 138, 154, 172, 173, 182, 183, 192, 198, 201–2, 214, 240, 247, 248, 257, 259–61, 263, 264–9 Cregan-Reid, Vybarr: Primate Change 178–9, 189 Criado-Perez, Caroline: Invisible Women 141 cycling body fat and 173 calories and 113 car travel supplants 2, 3, 127, 217–18 children/schools and 121, 130, 214, 217, 237–8, 246, 247 commuting/everyday cycling for transport 7, 9, 13, 27–8, 34, 58, 104–5, 113, 114, 115–20, 129, 137, 177, 182, 183, 184, 199, 213, 254, 261, 265, 270, 272–3 couriers 11–13 Denmark and 7, 111, 121, 128, 130, 135, 239, 240, 249, 268 electric-assist bicycle/e-bike 128–30, 135 Finland and 236–8, 246, 247 heart attacks and 74 lanes/routes 9, 28, 82, 111, 119, 120–1, 122, 124, 130, 133, 192, 237, 246, 253–4, 265, 267–8 leg strength and 224, 231, 276 METs and 51, 52, 58, 115, 129 mortality and 114–20, 121 Netherlands and 119, 121, 125, 127, 128, 239, 240, 249, 268 Olympics and 34 overweight people and 166 Peloton 31 postmen and 73 safety/road danger 28, 118–19, 121, 125–6, 128, 137, 216–18, 240, 260 Slovenia and 253–4 social engineering and 236–8, 239–40, 246, 247, 249, 253–4, 256 share schemes 106 short car trips and 136, 137, 143 town/city planning and 33, 111, 112, 113, 114–20, 121, 122, 124–6, 127–31, 136, 137, 141, 143, 191, 192, 236–9, 246–7, 249, 253–4, 256, 263–4, 267–8 cytokines 42, 161, 162 Dahl, Roald 217–18 Daily Mile 203–7, 212–13, 214, 249, 251, 261, 262 Davies, Adrian 5, 35 dementia 5, 49, 87, 88, 226, 227, 229, 232–4 Denmark cycling in 7, 111, 121, 128, 130, 135, 137–8, 184, 239, 240, 249, 268 town/city planning in 109–12, 114–15, 121, 122–3, 125, 128, 130, 131, 132–5, 268 Department for Transport, UK 3 depression 5, 50, 106, 250 diabetes 88, 90, 95, 102, 186, 187, 192–3, 227 pre-diabetes 37, 59, 188 type 1 37, 94 type 2 4, 5, 36, 37, 41, 42, 43, 46, 48–9, 57, 89, 93–4, 99, 106–8, 129, 145, 146, 151, 160, 162–3, 167, 185, 193, 215, 222, 265 Diabetes UK 108 Disneyland 135–6 Dober Tek campaign 254–5 Doll, Richard 79 Donaldson, Liam 79 driverless cars 136, 137 Dunstan, David 192–3, 200 duurzaam veilig (sustainable safety) 126 electric-assist bicycle/e-bike 128–30, 135 electric vehicles 128–30, 135, 136–7, 268 endocrine system 42 Equinox (US gym chain) 32 Erickson, Kirk 226, 233–4, 275 exercise see individual exercise and area of exercise ‘fat and fit’ 147, 169–75 fat, body 42–4, 145, 146–7, 151, 161, 162, 165–6, 167, 169–75, 185, 188, 193, 242, 255 financial costs of inactivity 87–143 mortality and morbidity and 90–3 NHS/universal medical systems and 87–108 non-medical long-term action against preventable conditions and 102–8 social care and 100–2 total additional costs imposed on health services due to inactivity 94–5 Finland 236–47, 258 cycling in 236–8, 246, 247 Finnish Schools on the Move 211–12, 246, 252 Global Report Card study on childhood activity levels and 252–3, 255 Helsinki central library 252 Network of Finnish Cycling Municipalities 247 social engineering in 236–47, 249, 252, 262, 264 Sports Act (1980) 245–6 Sports Act (1999) 246 Winter Cycling Congress 238, 246 see also individual place name Fitbit 54, 181 fitness industry 3, 31, 33, 34 fitness watches 116, 181, 270–1 food corporation lobby 148 ‘four by four’ threat (four most damaging NCDs) 90 Frauen-Werk-Stadt (Women’s Work City), Vienna 140–1 Freiburg, Germany 137–8 Frome, Somerset 141–3 Garmin 116, 181, 270–1 Gehl, Jan 109–12, 120, 122–4, 125, 126, 131, 135, 184, 268, 275 Life Between Buildings 110, 122–3, 131 Gill, Tim 138, 218–20 No Fear: Growing Up in a Risk-Averse Society 219–20 Glasgow University 66, 68, 134, 163 Global Report Card study on childhood activity levels 24, 252–3 glucose intolerance 37, 38, 167, 185, 192–3, 194 Gobec, Mojca 254–5 Googleplex, Mountain View 133, 196 Greater Manchester 124–5, 127, 264–6 gyms 1, 4, 26, 30–5, 51, 106, 149, 166, 167, 220–1, 223–4, 256, 276 Hartley, Sir Percival Horton-Smith 64–5 Harvard Alumni Health Study 75–7, 134 Harvard University 46, 52, 74, 76, 77, 134, 171 Haskell, William 26, 274 Hatano, Yoshiro 54 Health Education Authority 210 health gap (gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy) 92–4, 95, 99–100, 222 Healy, Genevieve 194–6, 274 heart attacks 41, 48, 50, 62, 70, 71, 74, 75, 76, 77, 91, 92, 93, 106 see also cardiovascular health heart disease 5, 43, 46, 48, 59, 68, 69, 70–4, 81, 82, 88, 89, 114, 152, 154, 243, 244 see also cardiovascular health heart rate 13, 27, 53, 116, 117, 129, 181, 197, 270 Hidalgo, Anne 192 high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) 43, 185 Hillman, Mayer: One False Move 217–18 Hillsdon, Mervyn 79–80, 83, 84, 85 Hippocrates 63 Hobro, Denmark 131 hunter-gatherers 5, 15, 16, 17 Hunt, Jeremy 261–4 Imbeah, Alistair 224 inactivity financial costs of 87–143 see also financial costs of inactivity obesity and see obesity sitting and see sitting see also individual area and consequence of inactivity incidental activity (activity which takes place as part of your regular day) 27, 114, 220 individual responsibility 2, 30, 58, 148, 263 industrialisation 2, 30 inequality (of income and opportunity) 103 Ineos 205 inflammation 42, 48, 68, 161, 162, 223 Institute of Hygiene and Occupational Health, Sofia 165 insulin 36, 37, 38, 42, 43, 57, 146, 161, 162 International Olympic Committee 81 International Space Station 44 Johnson, Boris 259, 260, 261, 264, 266, 267 Kail, Eva 139–43 Kelly, Mark 44 Kelly, Phil 88–9, 96–7, 103–5, 107 Kelly, Scott 44 Keston, John 225 keto diet 146 King’s College Hospital, London 87–9, 91 Kiuru, Krista 238–9, 245 Korhonen, Nina 246, 248–9, 252 Kraus, Hans: Hypokinetic Disease: Diseases Produced by Lack of Exercise 74 lactic acid 40–1 Lancet, The 23, 46, 47, 73, 95, 98, 128, 153, 199, 210 Lean, Mike 163–4 Lee, I-Min 46, 47, 52, 55, 56, 59, 60, 74, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 274 Levine, James 189–92, 193, 194, 196–7, 199, 201 Lewis, Thomas 68, 71–2 life expectancy 91–2, 99, 221–2 health gap (gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy) 92–4, 95, 99–100, 222 lipaemia 43 liver 161, 186, 187 Longevity of Oarsmen study, The 64–5 longshoremen health study, San Francisco 75 low-density lipoprotein (LDL) 43, 185 Lucas, Tamara 73–4, 83, 85 lung cancer 48, 79 lung function 5, 95–6 Lykkegaard, Kasper 181–2 Mackenzie, Richard 36–8, 43, 59, 117, 274–5 Maguire, Jennifer Smith 31, 32, 33 Mancunian Way, Manchester 124–5 Marin, Sanna 238 Marmot, Michael 82–3 ‘Matthew effect’ 206 Mayer, Jean 154–6, 157, 175 Physiological Basis of Obesity and Leanness 155–6 McGovern, Artie 31 meals, movement and processing of fats and sugars after 43–4, 167, 183, 188, 194, 272 mental health 49–50, 74, 204, 211 MET (metabolic equivalent) 51–2, 58, 115, 129, 178 metabolic disorders 5, 43, 49, 74, 95 see also individual disorder name metabolic rate 39, 51, 158, 191 micro mobility 135 Miliband, Ed 266–7 minimum amount of moderate activity needed to maintain health, recommended 116–17 mitochondria 41, 48, 167 Mitrovic, Polona Demšar 254 modal filtering 126 morbidity 89, 91–3, 160, 168–9, 227, 256–7 Morris, Annie 66–7 Morris, Jerry 61–3, 64, 65, 66–74, 75, 77, 79, 80–6, 152, 154, 241 Morris, Nathan 66–7, 83 Moscow 111, 112, 123 Mosley, Michael 229 movement decline of everyday 15–35 rediscovery of benefits of 61–86 see also individual type of movement muscle leg 224, 231, 276 skeletal 40, 42, 43, 167, 276 smooth 40 strength/muscle training 22, 223, 228, 271–2 wastage 22, 42, 223–4 Muscular Christianity 30 myosin (protein) 40 ‘nanny state’ 9, 243–4, 262–3, 264, 265 NASA 44 National Fitness Survey (1990) 84 National Health Service (NHS) 9, 70, 101, 164, 179, 223, 266 cost of inactivity to 9, 89–90, 93–7, 101, 104, 106–7, 153–4 social prescribing 105–6 National Lottery 33 Nebelong, Helle 219–20 Netherlands 119, 121, 125, 127, 128, 166, 239–40, 249, 268 Nieman, David 265 Niemi, Joonas 246, 248–9, 252 non-communicable diseases (NCDs) 90, 98 non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) 190–1, 194–5 North Karelia, Finland 241–3, 244, 245, 257 obesity 5, 19, 89, 98, 144–75, 215, 241 activity required to lose significant amounts of weight 144–7, 164–9 age and 152 basal metabolic rate and 158, 191 BMI and 146, 150–1, 160, 161–4, 167, 170, 171, 172, 173 body fat percentage and 146–7, 151, 165, 167, 170, 172–4, 193 childhood and 84, 152, 153, 212 costs of 95, 153–4 crisis 152–3, 154, 157 deaths and 47, 90, 160, 163, 170, 171 energy balance and 154–9 exercise benefits for 59, 144–7, 156, 158, 159, 165–6, 167–8 ‘fat and fit’ 169–75 health conditions associated with 160–1 obesogenic foodscape and 148–9 sex and 152 Slovenia and 256–7 stigma 147, 149–50 sugar and 146, 148, 156, 166 waist circumference and 161–4, 169, 172 weight loss/Watson and 144–6, 147–8, 149, 162, 166–7, 171, 173, 175, 270 worldwide spread of 152–3 Odense, Denmark 130 Ojajärvi, Sanna 247 older people/ageing staying active and 220–35 town/city planning and 138–9 Old Order Mennonites community 208 Olympics 33–4, 124, 224, 228, 255 (1964) 54 (1996) 33, 81 (2000) 33 (2012) 23 150-minutes of moderate exercise per-week recommendation 21–2, 26, 38, 54, 201, 270 active travel and 112 children and 207 commuting and 127–8 definitions of moderate and intense exercise 22 MET and 58 moderate activities, WHO list of possible 52 mortality and 45 older people and 222 strength training and 271–2 weight loss and 164 osteoporosis 16–17, 209, 227 Paffenbarger, Ralph 62, 64, 74, 75–82, 84–5, 101, 134, 225, 274 Paris 191–2, 197, 268 Parkrun 106, 249–51 pavement 120, 122, 124, 130, 140, 141, 237, 265, 268 pedometers 53–4 Peloton 31 personal choice, myth of 25–30 personal trainers 31 Peska, Pukka 46, 240–5, 257, 262–3 Physical Activity and Health (eds Bouchard, Blair, Haskell) 39 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PACAG) 45, 48, 57 physical activity level (PAL) 51 Pichai, Sundar 133 Policy Studies Institute 217 polypharmacy 89 portal theory 161 poverty 67, 68, 69, 82, 152, 180 Poynton, Frederic 68 protein 37, 40 Public Health England (PHE) 3, 22, 33, 57, 94–5, 97, 169, 269 Raab, Wilhelm: Hypokinetic Disease: Diseases Produced by Lack of Exercise 74 Radcliffe, Paula 36 ramp test 117–18 rheumatic heart disease 68, 69–70, 82, 152 risk-averse culture 207, 219 road danger 28, 119, 121, 125–6, 128, 137, 216–18, 240, 260 Roehampton University 36, 117, 172 Rook, Sir Alan 65 Ross, Robert 149–50, 157, 160, 161–2, 163, 164, 168–9, 171, 173, 174, 175 Rost, Leon 132–4, 135, 136, 139 Royal College of General Practitioners 105 running 1, 3, 9 ageing and 225, 227, 275 ATP and 40 bone density and 16 childhood and 203–7, 209, 210, 212–13, 214, 215, 246, 255 exercise industry and 31 home running treadmills 147 METs and 51, 58 150-minutes of moderate exercise per-week recommendation and 22, 52, 201 overweight people and 167 Paffenbarger and 76, 77, 78–9, 80, 225 Parkrun 106, 249–51 ultrarunning 32 schools 20, 27, 30, 121, 210–20, 236, 237–8, 239, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 252–7, 261–2 cycling to 121, 130, 214, 237–8, 246, 247 Daily Mile and 203–7, 212–13 English curriculum, physical education and 212, 248, 261–2 Finland and 211–12, 246, 252–3, 257 free school meals at 245 girls low activity levels in 204, 209, 210–11 Global Matrix 3.0 Physical Activity Report Card and 24, 252–3 independent childhood mobility, perceived cosseting of children and 216–20 playing fields 103, 107 Scottish schools curriculum, physical education and 212 sitting in 211–16 Slovenian 212, 255–7 social engineering and 237–8, 239, 244, 245, 246 sedentary behaviour 177–202 see also sitting Sens 181–4, 271 short-termism 107 Sidewalk Labs 136 Sim, David: Soft City 123–4, 126–7 Sinton-Hewitt, Paul 250 sit-stand test 228–31 sit-stand workstations 195, 196, 198–9, 200, 202 sitting 5, 13, 24, 26, 39, 49, 54, 62, 72, 176–202, 211–16 active applause and 176–7, 180, 271 average amounts of 179 breaking up prolonged 176–7, 180, 181, 182, 190–1, 193, 194–5, 197, 200, 271, 275 chair and 178–9 diabetes and 185, 186, 187, 188, 192–4 exercise and effects of 184, 199–201 fidgeting and 190–1, 194–5 health effects of 176–7, 185–8 low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL)/triglycerides and 185 ‘new smoking’ headlines 177 schools and 211–16 sedentary behaviour defined 177–8 sit-stand test 228–31 sit-stand workstations 195, 196, 198–9, 200, 202 tracking/measuring 179–84 TV viewing and 178, 186, 187–8, 189, 192 workplace and 189–92, 195–9, 201–2 skeletal muscles 40, 42, 43, 167, 276 skinfold body fat test 173–4, 255 Skinner, James 21 sleep 5, 42, 50, 57, 184 Sleep, Leisure, Occupation, Transportation, and Home-based Activities (SLOTH) 25 Slofit programme 255–6 Slovenia 24, 212, 253–8, 261 Smith, Edward 63–4 smooth muscle 40 social care 97, 99–101, 108 social engineering 236–58 cycling and 236–8, 239–40, 246, 247, 249, 253–4, 256 Finland and 236–47, 249, 252–3, 255, 257, 258 see also individual area of Finland kindergartens and 252 mortality rates and 240–5 ‘nanny state’ objections to 243–4 obesity and 241, 252–7 Parkrun 249–51 political support, need for complete 244–5 schools and 236, 237–8, 239, 244, 245, 246–7, 248, 252–3, 255, 256, 257 Slovenia and 253–7, 258 sports facilities funding 245–6 tax and 245–6, 252 Youth Sports Trust, UK 247–9, 251 social medicine 61, 68–71, 83 Social Medicine Unit 61, 69–70 socialism 66, 67–8 social prescribers 105–6 Spevak, Harvey 32, 35 Sport England 34 stairs 28–9, 131–4 Starc, Gregor 255–7 St Mary’s Hospital, London 93 St Ninian’s primary school, Stirling, Scotland 203–7, 213 Stockholm, Sweden 141 Stop de Kindermoord (Stop the Child Murders) road safety mass protests, Netherlands (1970s) 121, 240 strength/muscle training 22, 223, 228, 271–2 stroke 5, 46, 61, 81, 89, 160, 180, 186, 267 technology, monitoring of activity levels and Active Ten app (Public Health England) 57, 269 activity trackers 38, 57, 116, 180–4, 200–1, 214–15, 269, 270–1 Sens activity tracker 181–4, 200–1, 214–15, 271 television viewing 26, 82–3, 121, 186–9, 192 telomeres 41–2, 226 10,000 steps a day target 26, 38, 52, 53–5, 56, 184, 200, 270, 275 Titmuss, Richard 68–9 town/city planning (built environment) 5, 28–9, 108, 109–43, 210 active travel and 109–43 Amager Bakke and 134–5 Buchanan and 120–1 cars, hegemony of 110, 111, 113, 120–2, 124, 125, 126, 127–31, 135–8, 140, 141, 142, 143, 191–2, 263, 265, 268 Copenhagen 111–12, 122, 123 coronavirus lockdown and 130–1 cycling and 111, 112, 113, 114–20, 121, 122, 124–6, 127–31, 136, 137, 141, 143 driverless cars and 136–7 duurzaam veilig (sustainable safety) concept 126 e-bikes and 127–30 Gehl’s philosophy 109–12, 120, 122–4, 125, 126, 131, 135 Googleplex, Mountain View and 132–4 health dividends of active travel and 114–20 Manchester and 124–5, 127 Odense and 130 older people/those with disabilities and 138–9 stairs and 131–2 Toyota Woven City 135–6, 137, 138–9 Vauban, Freiburg 137–8 walking and 109, 112, 113, 114, 115, 120, 121–7, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 136, 137, 140, 141, 143 women and girls, discrimination against 139–43 Toyota Woven City, Japan 135–6, 137, 138–9 tracking, electronic activity 13, 17, 21, 26, 38, 52, 53–5, 56, 57, 113, 116, 180–4, 190, 200–1, 214–15, 269–71, 272 transport use see individual mode of transport travel, active 9, 24, 112–14, 118, 121, 126, 127, 131, 136, 143, 191, 216 see also individual mode of travel Travers, Andrew 100–1 treadmill desk 199 triglycerides 43, 185 True Finns 245 Tudor-Locke, Catrine 53–4, 56 Tulleken, Xand van 29–30, 44–5 Uber 137 ultrarunning 32 University of Massachusetts 53 Utrecht, Netherlands 125 Utzon, Jørn 111 Valabhji, Jonathan 93, 99, 104 Varney, Justin 97–8, 169, 198 Vartiainen, Juha-Pekka 237 Vauban, Freiburg, Germany 137–8 Vienna, Austria 140–3 VO2 max test 117–18, 173 walking Active Ten app and 57, 269–70 ageing and 102 assessing/tracking 26, 38, 52, 53–5, 56, 181, 182, 183, 184, 200, 269–70, 272 bone density and 16 brisk/speed of 3, 9, 22, 48, 52, 53, 55, 57, 60, 74, 79, 84, 86, 114, 167, 269 children and 11, 209, 214, 215, 216, 218, 246, 247 commuting and 114, 130 cycling and 114, 115 danger and 120 decline in 2, 3, 9, 16, 18, 19, 27–9, 33, 208, 216 fat processing/reduction and 43, 48, 185 150 minutes of moderate activity a week recommendation and 52–4 social prescribing and 106 stairs and 28–9, 131–4 10,000 steps a day target 26, 38, 52, 53–5, 56, 184, 200, 270, 275 town/city planning and 109, 112, 113, 114, 115, 120, 121–7, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 136, 137, 140, 141, 143 weight loss and 144–5, 157, 165, 166, 167 workplace and 196, 197, 199, 200, 201, 202, 274, 275 WALL·E (film) 25–6 Watson, Tom 144–6, 147–8, 149, 162, 166–7, 171, 173, 175, 270 Downsizing 145 weekend warriors 58–9 Wellington, Chrissie 250, 251, 252, 257 Whyte, Martin 87–9, 91, 94, 95–6, 102–5, 106–8 Wicks, Joe 10 Wiggle 270 Wijndaele, Katrien 187–8 Winter Cycling Congress 238, 246 Wollaston, Sarah 263 Wolff’s Law (bones adapt to the repeated loads put on them) 209 women 6 BMI and 51 bone density 16, 18, 227 cancer and 48 diabetes 151 girls, low activity levels in 141–3, 204, 209, 210–11, 256 life expectancy 92, 222 modern decline in activity among 19, 22, 24 obesity and 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 157, 159, 160, 161, 162–3, 164, 165, 171 150-minutes of moderate exercise per-week recommendation and 22, 207 public space and 139–43 sitting and 186 walking and 53–4, 55, 84, 121 World Health Organization (WHO) 22, 47, 52, 98, 151, 152–3, 210 World Obesity Forum 154 Wright, Chris 247–9, 252, 257 Wyllie, Elaine 203–4, 205, 206, 209, 212, 213, 262 Youth Sports Trust 247–9, 251 First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2021 Copyright © Peter Walker, 2021 The right of Peter Walker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

…

Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 118, No. 8 (2010): 1109–16. 12 Rachel Aldred et al., ‘Cycling Near Misses: Findings from Year One of the Near Miss Project,’ 2015 http://rachelaldred.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Nearmissreport-final-web.pdf 13 Analysis by Professor Rachel Aldred of Westminster University for her ‘Project Pedestrian’ study. It found that 548 pedestrians were killed in the UK on pavements or verges between 2005 and 2018. 14 Peter Walker, ‘Reduction in passenger road deaths “not matched by cyclists and pedestrians” ’, The Guardian, 30 January 2020. 15 Colin Buchanan, Traffic in Towns (London: Penguin, 1964). 16 Vic Langenhoff, Stop de Kindermoord, De Tijd, 20 September 1972. Langenhoff wrote the article after his daughter Simone had been killed by a speeding car. The driver was fined the equivalent of £20. Then one of his older daughters was injured after being forced off her bike by a driver.

…

Three years after Gehl left university as a fresh-faced and obedient advocate of the new consensus, the UK saw the publication of what was, in retrospect, one of the most malignly influential publications of the era. Traffic in Towns15 first came out in 1963 as a planning report, but achieved the rare feat for such a document of becoming so popular it was later issued as a paperback book. Written by Colin Buchanan, an engineer and town planner, it expressed some concern at the rising tide of motor traffic but concluded this was the future, and thus many more roads must be built. Buchanan wondered briefly about the idea of also constructing bike routes, but dismissed this, saying it was ‘a moot point’ whether there would realistically be many cyclists remaining a few years down the line. This was the era when countries around Europe, as well as the USA, were embracing car culture, with entire historic districts of cities flattened to make way for urban motorways and ringroads.

Carmageddon: How Cars Make Life Worse and What to Do About It

by

Daniel Knowles

Published 27 Mar 2023

And this model of development was adopted all over Britain, by planners who saw the rise of the automobile as inevitable and desirable. The postwar city would become what Sir Colin Buchanan, a civil servant in Britain’s department of planning, called, “one of the most interesting reconstructions in Europe.” He was the author of “Traffic in Towns,” a government paper published in 1963 that generated so much buzz that it was reprinted by Penguin and sold tens of thousands of copies. Buchanan’s report makes for fascinating reading, precisely because it perfectly anticipated the rise of the automobile and what damage it would do to British cities—and then argued exactly why it could at best only be mitigated, rather than stopped.

…

Buchanan’s report makes for fascinating reading, precisely because it perfectly anticipated the rise of the automobile and what damage it would do to British cities—and then argued exactly why it could at best only be mitigated, rather than stopped. The moment that the car could have been contained was then, in the 1960s. Instead, everything was changed to accommodate it. “Traffic in Towns” begins with a brilliantly ominous explanation of the coming calamity. When Buchanan did his research, there were around ten million cars in Britain. Within a decade, he predicted—accurately—this number would double. “The population appears as intent upon owning cars as the manufacturers are upon meeting the demand,” he wrote. And yet the problems were already evident.

…

Looking across at America—by then already much more automotive than Britain—he noted that the car was not beautifying cities but rather “producing unrelieved ugliness on a great scale.” Yet Buchanan argued that it would be difficult to stop. “Perhaps because we have all grown up with the motor vehicle, and it has grown up with us, we tend to take it and its less desirable effects very much for granted.” The car had become a status symbol, and it was no good to tell people that their desire had downsides too. Indeed, Buchanan himself sang the praises of owning a personal vehicle. “Why cannot we be less hypocritical and admit that a motor car is just about the most convenient device that we ever invented?”

Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling

by

Carlton Reid

Published 14 Jun 2017

And it was mass motorization—a seemingly unstoppable force—that was behind the steady decline in cycling’s popularity. Traffic in Towns, the 1963 report mentioned earlier, featured cycling only in passing; lead author Colin Buchanan clearly believed that urban cycling would wither to nothing: … it is a moot point how many cyclists there will be in 2010…. [This] does affect the kind of roads to be provided. On this point we have no doubt at all that cyclists should not be admitted to primary networks, for obvious reasons of safety and the free flow of vehicular traffic … It would be very expensive, and probably impracticable, to build a completely separate system of tracks for cyclists. Traffic in Towns was commissioned by Transport Minister Ernest Marples.

…

Critics complained that this would mean drivers would get ground-level access to the streets, but all other users would have to climb into the sky or creep underground. Such plans were broadly welcomed by the establishment of the day—Tripp was especially popular in America—and the ideas were later adopted by architect and town planner Colin Buchanan in his team’s internationally influential 1963 report, Traffic in Towns. Tripp was not one of the town planners appointed to a 1943 Ministry of War Transport committee looking to reconstruct postwar Britain, but his segregationist influence can be seen throughout the committee’s report, published in 1946. Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas recommended segregated provision for the growing number of cyclists, worrying that “conditions obtaining in early postwar years will tend still further to popularize the cycling habit.”

…

In 1960, Marples told delegates at the Tory party conference that “we have to rebuild our cities. We have to come to terms with the car.” And it was this accommodation that he tasked Professor Buchanan with finding. Marples was far from a disinterested party. He owned two-thirds of Marples, Ridgway, and Partners, a Westminster-based civil engineering firm that built roads, and would later be handed the contracts for the style of motorways and flyovers illustrated in Traffic in Towns. In 1975, Marples, who had by then been made a baron, fled the country, not because of his hushed-up proclivity for prostitutes, his introduction to Britain of traffic wardens and parking-is-prohibited double yellow lines, or the conflict of interest in building motorways at the same time as cutting Britain’s rail network, but because of tax evasion.

The City on the Thames

by

Simon Jenkins

Published 31 Aug 2020

Guidance on implementing the post-war road schemes had been supplied by Sir Colin Buchanan, in a 1963 report titled Traffic in Towns. It was sensational. In the 1940s, the Architecture Review had preached ‘traffic modernism’. Honouring it, said Buchanan, meant a ‘traffic architecture… so people could live at peace with the motor car’. This would best be done by devoting the city’s ground floor, Barbican-style, to traffic and allocating pedestrians upstairs to a city-wide ‘deck’. The deck became the holy grail of London planners. Buchanan declared it would supply ‘the things that have delighted man for generations in towns, the snug, close, varied atmosphere, the narrow alleys, the contrasting open squares, the effects of light and shade, and the fountains and the sculpture’.

…

The Advertising Archives 61. Sir Patrick Abercrombie, 1944, photograph by Howard Coster. © National Portrait Gallery 62. Richard Seifert and the NatWest Tower, c.1979, photograph. Anthony Weller/View/Shutterstock 63. Traffic Architecture Applied to Fitzroy Square, 1963, illustration by Kenneth Browne for the Buchanan Report, Traffic in Towns. Private collection 64. Cricklewood Broadway, 1965. Getty Images 65. Cartoon from Roy Brooks, Mud, Straw and Insults: A Further Collection of Roy Brooks’ Property Advertisements, undated, 1960s. Private collection 66. Carnaby Street, 1970, illustration by Malcolm English. © Malcolm English/Bridgeman Images 67.

…

G., High Rise 301 Baltic Exchange 131, 215; bombing (1992) 290 Bangladeshi immigrants 275 Bank of England 162, 175, 214; buildings 146, 221, 290; foundation 92, 93 bank holidays, introduction of 182 Bank station 167, 194, 236, 295 banking and financial services industry 92–3, 98, 115, 175, 239, 275, 293–7, 306, 315 Bankside power station 284, 303 Banqueting House (Whitehall) 59, 66, 85, 86 Baptists 66, 84, 136 Barbican 11, 13, 243; estate 253–5, 269, 280, 283, 307, 310; see also Museum of London Barbon, Nicholas 84–5 Barbon, Praise-God 84 Barkers of Kensington (department store) 181 Barking 206, 270 Barlow Commission 232, 240 Barnard’s Inn Hall (Holborn) 49 Barnes 210, 276 Barnett, Dame Henrietta 209 Barons’ War (13th century) 29, 30, 31 baroque architecture 81, 95, 105, 198; revival 198, 199–200, 221–2 Barratt, Nick, Greater London 242 Barry, Sir Charles 146, 153–4 Bartholomew Fair 37 Bart’s see St Bartholomew’s Hospital Basildon 300 Bath House 147 baths and washhouses, public: 19th century 189; 20th century 201, 213; Roman era 11, 12, 13–14, 338 Battersea 8, 17, 136, 165, 272; Arding & Hobbs (department store) 181; power station 284, 327–8 Battersea Fields/Park 183 Bauhaus 232 Baynard’s Castle 26–7 Bayswater 141, 165, 181, 194, 250; Leinster Terrace 141; Porchester Terrace 141; see also Lancaster Gate Bayswater Road 249 Bazalgette, Sir Joseph 164, 168, 176, 177 BBC 299, 329, 334; Broadcasting House 222; Bush House 221 Beatles (band) 261 Beck, Harry 229 Becontree housing estate 223, 228, 252, 269 Bede the Venerable, St 15 Bedford, John Russell, 1st Earl of 45 Bedford, Francis Russell, 4th Earl of 61–2, 70, 83 Bedford, John Russell, 6th Duke of 139 Bedford, Herbrand Russell, 11th Duke of 220 Bedford estate 100, 101, 139, 178, 227, 250, 282 Bedford Park 179 Bedford Square 103, 123 beer see brewing and beer Beijing (Peking) 173, 174 Belgravia 72, 100–101, 139–41, 156; Belgrave Square 73, 230; Chester Square 140, 153; churches 137, 153; Eaton Square 137, 153; Wilton Crescent 140; Wilton Place 153 Belsize Park 142 Bentham, Jeremy 145 Bentinck, Hans Willem (later 1st Earl of Portland) 89, 103 Berkeley, George, 1st Earl of 84, 100, 103 Berkeley, Randal, 8th Earl of 220 Berkeley Square 73, 103–4, 123, 220–21, 259, 334 Berkhamsted 24 Berlin 3, 193, 240, 241, 313 Bermondsey 17, 95, 137, 185, 206, 216, 225, 307, 339; abbey 28, 42, 46; see also Shard Bermuda 94 Berners estate 102 Besant, Annie 177 Besant, Sir Walter 2–3, 207–8, 208 Bethnal Green 137, 151, 185, 219, 305; council housing estates 202, 223, 265–6 Betjeman, Sir John 81, 231–2 Bevan, Aneurin 240 Beveridge, William, 1st Baron, report on welfare reform (1942) 240 Bevis Marks (street) 67 Bexley 230 bicycles see cycling Biddle, Martin 15 Big Bang (financial markets deregulation) 293–4, 295–6 Big Ben (bell/clock tower) 154, 179 Bill, Peter 310 Bill Haley and the Comets (band) 248 Bill of Rights (1689) 91 Billingsgate 14, 39, 81; market 163, 284 Birch, John 78 birching (corporal punishment), outlawing 260 Birdcage Walk 197 Birmingham 148, 149, 161, 188, 190, 270, 278, 318; railways 156, 157, 165, 168; town hall 188 Birt, William 209 bishopric of London 17–18 Bishopsgate 11, 27, 49, 310; Pinnacle (22 Bishopsgate) 310, 312 Bismarck, Otto von 176 Black Death (14th-century plague) 33–4, 35, 40, 66 Black Monday (stock market crash, 1987) 296 black population 118, 261, 271, 275, 299 Blackfriars 11, 177; Apothecaries Hall 337; Black Friar pub 27; monastery 27; station 165, 166, 167; theatres 52, 57 Blackfriars Bridge 114, 120 Blackheath 39, 68, 183, 210 Blackwall Docks 131 Blackwall Tunnel 280 Blair, Tony 302–6, 308, 314, 316 Blemond, William de 72 Blériot, Louis 200 Blitz (1940–41) 3, 77, 227, 234–8, 239, 245, 262 Bloomberg Centre (office building) 10, 14 Bloomsbury 72, 100, 101, 123, 139, 172, 250, 284; Bedford Square 103, 123; Bloomsbury Square 72, 100, 139; Brunswick Centre 268; Brunswick Square 125; Friends Meeting House 230; Gordon Square 139; Gower Street 178; Mecklenburgh Square 125; Russell Square 139, 179; St George’s Church 111; Tavistock Square 139; Torrington Square 284; University of London 227, 234, 250, 284; Woburn Square 284; see also British Museum Blore, Edward 146 Blow Up (film) 261 blue plaques scheme 265 Blue Stockings Society 103, 124 Boateng, Paul, Baron 299 Boccaccio, Giovanni 36 Boer War 195 Boleyn, Anne, Queen Consort 44, 46–7 bombing: Great War 216–17; Second World War 3, 77, 227, 234–8, 239, 245, 262; terrorism 290–91, 304–5 Bon, Christoph see Chamberlin, Powell and Bon (architectural practice) Bond, Sir Thomas 84 Bond Street 126, 199, 261, 339 Boodle’s (club) 137 Booth, Charles 184, 187, 208, 334 Boots (chemist) 277 Borough High Street 51, 311 Borough Market 257, 332 boroughs, establishment of 192, 201, 263, 264 Boston (Lincolnshire) 32 Boston (Massachusetts) 118 Boswell, James 107, 126–7 Bosworth Field, Battle of (1485) 39, 40 Boudicca (Celtic queen) 2, 10 Bovis (construction company) 269 Bow 171, 191, 251, 307; Abbey Mills pumping station 164; Bryant & May match factory 189 Bow Street, court 110 Bow Street Runners 112, 148 Bowen, Elizabeth 236 Boyle, Robert 70 Bracknell 251 Bradley, Mary Anne 132 Bradley, Simon 80, 179 Bradwell-on-Sea, St Cedd’s Monastery 18 Bramante, Donato 40 Brasilia 174 Breda, Declaration of (1660) 67 Brentford 125, 206 Brewer Street 338 brewing and beer 42, 96, 112, 206 Brexit (British exit from European Union) 13, 330–31 Brick Lane 261 Bridewell Palace 46, 55 bridges see Albert Bridge; Blackfriars Bridge; Hammersmith Bridge; London Bridge; Putney Bridge; Southwark Bridge; Tower Bridge; Vauxhall Bridge; Waterloo Bridge; Westminster Bridge Bridgewater House 147 Brighton 217; Grand Hotel bombing (1984) 290 Brighton Rock (film) 248 Bristol 40, 57, 131, 278, 318 Britain, Battle of (1940) 234 Britannia (Roman province) 10, 12–13 British Library 145, 250 British Museum 101, 104, 145, 172, 241, 250, 284 British Rail 283, 329 Brixham 89 Brixton 191, 208, 275; Loughborough estate 253; prison 219 Broadgate development 296 Broadwick Street 163 Bromley 230 Brompton Road 256 Bronze Age 8 Brown, George (later Baron George-Brown) 263 Brown, Gordon 314, 315 Brown, Lancelot ‘Capability’ 133 Brown’s Hotel 200 Brummell, Beau 138 Brunel, Isambard Kingdom 165, 175, 194 Brunelleschi, Filippo 40 Brunswick Centre 268 Brunswick Square 125 Brussels 26, 275, 296, 320 Brutus (legendary founder of London) 8 Brydges Place 338 Brydon, John 198, 199, 283 Brythonic people 16–17 Buchanan, Sir Colin, Traffic in Towns report 278–9, 280, 316 Bucharest 174, 326 Buckingham, George Villiers, 2nd Duke of 84–5 Buckingham and Normanby, John Sheffield, 1st Duke of 85 Buckingham House/Palace 84, 85, 97, 139, 144, 145, 146, 166, 196–7, 304 Buckingham Palace Road 199 Bucklersbury House (office building) 14 Buenos Aires 174 Building Act (1774) 121–2, 123, 135, 159, 188, 211 Bulstrode Park 103 Burbage, James 52 Burbage, Richard 52 Burdett-Coutts, Angela, 1st Baroness 187 Burghley, William Cecil, 1st Baron 47, 48 Burke, Edmund 118, 129, 130 Burlington, Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of 84, 102 Burlington, Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of 105–6, 122 Burnham, Daniel 200 Burns, John 191 Burton, Decimus 135, 138 Burton, James 125, 135 Burton, Sir Montague 245 bus lanes 281 buses 144, 167, 177, 204, 205, 309, 317; double-decker 205, 309, 317; fares 288, 309; routes 23, 205 Bush, George W. 304 Bush, Irving T. 221 Bush House 221 Bute, John Stuart, 3rd Earl of 115–16 Byron, George, 6th Baron 127, 183 Byzantium 16, 21 CABE (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment) 314 cable car (cross-Thames) 316 Cable Street 42, 131 Cadogan, Charles, 2nd Baron 104 Cadogan estate 104, 140 Cadogan Square 179 Cadwgan ap Elystan (Welsh warlord) 104 Calcutta 37 California 48, 320; gold rush 158; see also Los Angeles; San Francisco Callaghan, James, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff 276 Camberwell 125, 143, 171, 201, 210, 272 Cambridge University 266 Camden, Charles Pratt, 1st Baron 124, 125, 143 Camden, Borough of 264, 270, 330; council housing 268, 272 Camden Lock 330 Camden Town 143, 157, 160, 230, 257 Camelford House 220 Cameron, David 315, 319, 330 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) 262, 291 Campbell, Colen 97, 103, 105 Canaletto 99, 206 Canary Wharf 293–5, 329, 338 cannabis 276–7, 305, 318 Cannes, MIPIM construction industry fair 313 Canning Town 313; Ronan Point 267, 273, 323 Cannon Street 7–8; station 7, 165 Canonbury 143 Canova, Antonio 145 Canterbury 17, 18, 35 Carausius (Roman military commander) 12 Carlton Club 192 Carlton House 132, 133, 134, 144 Carlton House Terrace 144, 283 Carnaby Street 261, 338–9 Caroline of Ansbach, Queen Consort 128 Carpaccio, Vittore, ‘Miracle of the True Cross’ 37–8 cars, motor 205, 211, 228, 239, 242, 278; accident rates 205; see also congestion charge zone; dual-carriage way roads; motorways Carshalton 8 Carter Lane 8, 337 Casanova, Giacomo 108, 110, 127, 206 Cassivellaunus (tribal chief) 9 Castlereagh, Robert Stewart, Viscount (later 2nd Marquess of Londonderry) 137 Catford 208, 230, 240 Catherine of Aragon, Queen Consort 42, 43, 44 Catherine of Braganza, Queen Consort 69, 87 Catherine of Medici, Queen Consort of France 48 Catholicism 17, 38, 44, 45, 47, 48, 61, 88–9, 105, 117; see also papacy Cavendish, Lady Margaret (later Duchess of Newcastle) 102 Cavendish Square 73, 102, 103, 123, 134 Caxton, William 41 Cecil Court 60 Cecil Hotel 177, 221 Cedd, Bishop of London 18 Celts 10, 16–17; language 7, 8, 17 censorship 98, 129, 260 Central Line 194, 204 Centre Point (New Oxford Street; skyscraper) 255–6, 257, 258, 265, 325 Chadwick, Sir Edwin 154–5, 156, 162, 163, 164, 166 Chalcot estate 142–3 Chamberlain, Joseph 190, 224 Chamberlain, Neville 223–4, 226, 232, 234, 240 Chamberlin, Powell and Bon (architectural practice) 253, 254 Chambers, Sir William 122, 123 Chandos, James Brydges, 1st Duke of 102, 106 Charing Cross 84; station 146, 165, 166, 203, 216 Charing Cross Road 177, 256 Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor 18, 24 Charles I, King 60–64, 65, 68; execution 66 Charles II, King 67–70, 73–4, 77, 78, 79–80, 81, 85–6, 87–8, 132 Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor 44 Charles, Prince of Wales 299 Charlotte Street 207; Schmidt’s restaurant 207 Charterhouse 45, 46 Chartists 161–2, 175, 192 Chatham, William Pitt, 1st Earl of 115, 116, 118 Chaucer, Geoffrey 36–8, 75, 106, 332; The Canterbury Tales 36–7 Cheapside 19, 31, 37, 51, 82, 126; St Mary-le-Bow Church 39, 161 Chelmsford 251, 300 Chelsea 171, 179; Albert Bridge 284; Cheyne Row 104; Cheyne Walk 104; King’s Road 140, 261, 323; Lots Road Power Station 203; Peter Jones (department store) 181; town hall 201; see also Kensington and Chelsea, Royal Borough of Chengdu 326 Chester Square 140; St Michael’s Church 153 Chesterfield, Philip Stanhope, 5th Earl of 126 Chesterfield House 126, 220 Chesterton, G.

Rush Hour: How 500 Million Commuters Survive the Daily Journey to Work

by

Iain Gately

Published 6 Nov 2014

Their existence was acknowledged and provided for after the publication of Professor Sir Colin Buchanan’s Traffic in Towns report in 1963. The report had been commissioned by Ernest Marples, minister of transport between 1959 and 1964, the éminence grise behind the railway cuts, who had both employed Dr Beeching and handed him his axe. Marples, who resembled a second-hand car dealer, had made a fortune from property development and civil engineering, and stood to gain more from new roads than old railways. Traffic in Towns supported him. ‘For the first time, the fact of unrestrained growth in car ownership was factored into town planning and urban design.’ Traffic in Towns predicted an apocalypse if Britain failed to adapt to the reality of car commuting: ‘Unless steps are taken, the motor vehicle will defeat its own utility and bring about a disastrous degradation of the surroundings for living’.

…

Index a Achen Motor Company 315 Acton 43, 46 Acts of Parliament 17 Acworth, Sir William Mitchell 73 aeroplanes 307 America cars 90–101 commuting 224–5 railways 66–80 American Automobile Association (AAA) 198, 209–10 American Bicycle Co. 91 American Motors 120 American School Bus Council (ASBC) 236 Andrade, Claudio 279, 280 Apple 295–6 Australia 232 autobahn 103, 109, 151, 166 b Bagehot, Walter 59 Balfour, A.J. 65 Barter, David Obsessive Compulsive Cycling Disorder 168 Bazalgette, Joseph 60 Beeching, Dr Richard cuts 137, 146, 158, 313, 328 Beerbohm, Max 58 Beijing 160, 161 Metro 160, 162 Benz, Karl 90 Bern, Switzerland 86, 87 Besant, Sir Walter 57 Best Friend of Charleston crash 69 Betjeman, John 109, 135, 272–3 bicycle Boris bikes 167 Brompton 167 commuting in Britain 101, 138–9, 166–8, 216–17 commuting in Europe 166, 222 Flying Pigeon 161–2 penny farthing 101 Raleigh 139 Rover 101–2 Birmingham HS2 329 number 8 bus 141 Birt, William 61 Bishop’s Waltham 313, 327 Blake, William Marriage of Heaven and Hell 104 Booth, Henry 27 Boris bikes 167 Boston 69, 97 Boston and Worcester Line 72 Botley station, Hampshire 1, 2, 3–5, 7, 313, 334 Bowser, Sylvanus Freelove 95 Brazil 279 British Telecom 291–3 Bromley 23, 46 Brompton bike 167 Brunel, Isambard Kingdom 331 Buchanan, Professor Sir Colin Traffic in Towns 145–6 buses 48, 140–41, 235–6, 275–6 c California High Speed Rail (CHSR) 330, 331 Callan Automobile Law 95 carriages (railway) 29–30, 54, 55 in America 71–3 in France 83–4 WCs 33, 72, 226–7 women-only 188–9 ‘workmen’s trains’ 33–4, 60, 61, 83 cars 89–92, 195 commuting in America 101, 113, 116–17 in Britain 107, 142–4, 249–52 in communist countries 151–2 in Italy 149–50 congestion 192–5 congestion charge 312 driverless 316–17, 320–27 ownership 97–8, 100, 103, 125 radio 119, 255–8 SUVs 204–8 Central Railroad of Long Island 76 C5 (electric tricycle) 309–11 Chaplin, William James 15 Cheap Trains Act 61 Chesterton, G.K. 57, 105, 109 Chicago Automobile Club 96–7, 256 Great Fire of 1871 79 Oak Park suburb 79–80 Park Forest suburb 113–15 China 160–62, 314–15 Chrysler 119, 160 Churchill, Winston 308–9 City and South London Railway 54–5, 62 Clean Air Act 286–7 Cobbett, William 334 Collins, Wilkie Basil 52 commuting (car) see cars commuting (cycling) see cycling commuting (rail) comic representation of 137 commuter etiquette 72–3, 82, 249 extreme commuting 233–4 in America 66–80 in France 81–7 in Germany 80, 86–7 in Japan 177–84 in the 1950s 136 in Victorian times 33–9, 42 food in England 36–7, 247 in France 84–5 origin of the term 67 overcrowding 171–83 coronations 140 County Durham 14 Coventry 102 Crawshay, William 35 Croton Falls 66 Croydon 56 Cultural Revolution (China) 161 Cunarders 140 cycling commuting in Britain 101, 138–9, 166–8, 216–17 commuting in Europe 166, 222 Cyclists’ Touring Club 102–3 d Dagenham 107 Dahl, Roald 129, 135–6 Daimler, Gottlieb 90 Dalai Lama 210 Darwin, Charles 13, 32 Daudet, Alphonse 83–4 Daumier, Honoré The Third-Class Carriage 83 The New Paris 86 Landscapists at Work 86 Defense Advance Research Projects Agency (DARPA) 317, 318 Delhi 211–13 Deng Xiaoping 161, 162 Denmark 222, 288 Detroit 110, 121, 123–4 ‘Detroit by the Volga’ 153 Dickens, Charles 12, 25, 50 food 36–7, 84–5, 247 Mugby Junction 84–5 Great Expectations 12 Our Mutual Friend 50 train travel in America 70, 71, 74 Diggins, John 3 Docklands Light Railway (DLR) 279 Downing, Andrew Jackson 66 driverless cars 316–17, 320–27 driving schools 215–16 driving tests New York State 94–5 UK 216 Duluth, Minnesota 79–80 e Ealing, London 38, 40, 42, 46, 56 Eden, Emily 58 Edinburgh 13, 14, 16, 329 Edmondson, Brad 314 Einstein, Albert 87 Eliot, William G.

…

Traffic in Towns predicted an apocalypse if Britain failed to adapt to the reality of car commuting: ‘Unless steps are taken, the motor vehicle will defeat its own utility and bring about a disastrous degradation of the surroundings for living’. Both drivers and city-centre pedestrians would suffer as a result of congestion, and the aspirations of the entire population, of whom it was expected that they would take car ownership ‘as much for granted as an overcoat’, would be frustrated. The answer, in Professor Buchanan’s opinion, was to create ring roads around cities, and car-free zones within them: ‘Distasteful though we find the whole idea, we think that some deliberate limitation of the volume of motor traffic is quite unavoidable.’ He had visited California and Texas as part of his research, and concluded that: ‘The American policy of providing motorways for commuters can succeed, even in American conditions, only if there is a disregard for all considerations other than the free flow of traffic which seems sometimes to be almost ruthless.

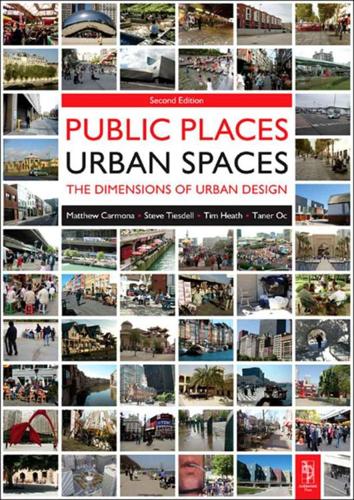

Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design

by

Matthew Carmona

,

Tim Heath

,

Steve Tiesdell

and

Taner Oc

Published 15 Feb 2010

Seeing through-traffic as an obstacle to community formation and busy traffic routes as obvious boundaries for residential areas, rather than places, as was the case in traditional settlements (e.g. the traditional high street), he proposed that arterial roads bypass rather than penetrate his neighbourhood unit, thereby protecting it from through-traffic. Within the unit was a hierarchy of roads, each sized according to the intended traffic load and deliberately less well-integrated than in a grid layout to minimise opportunities for rat runs An exceptionally clear statement of the principles of hierarchy came in the 1963 Buchanan Report, Traffic in Towns:‘The function of the distributory network is to canalise the longer movements from locality to locality. The links of the network should therefore be designed for swift, efficient movement. This means that they cannot also be used for giving direct access to buildings, nor even to minor roads serving the buildings, because the consequent frequency of the junctions would give rise to traffic dangers and disturb the efficiency of the road.

…

Similarly, Tripp (1942) advocated a ‘precinct principle’ from which extraneous traffic would be excluded. Given the ideas of his day, Tripp saw the precincts as specialised, single-land-use areas. A similar idea appears in the Buchanan Report (1964) – though rather than specialised single land use precincts, Buchanan’s environmental areas were intended to be mixed-use (Figure 4.16). FIGURE 4.16 Buchanan’s environmental areas (Image: adapted from Scoffham 1984). Buchanan proposed dividing the city into ‘environmental areas’ each bounded by major roads and kept free from through-traffic Pope (1996: 189) describes these processes as ‘grid erosion’, whereby open grid street systems become ‘ladder’ street systems – a grid allows movement in a variety of directions and through a variety of paths; a ‘ladder’ permits movement from A to B and vice versa (Figure 4.17a–c).

…

Many are not particularly historic, nor of high aesthetic quality, and are primarily valued for social and cultural rather than physical qualities (see Hayden 1995). Context must also be considered broadly. Buchanan (1988a: 33), for example, argued that context was not just the ‘immediate surroundings’, but the ‘whole city and perhaps its surrounding region’, and included:‘… patterns of land use and land value, topography and microclimate, history and symbolic significance and other socio-cultural realities and aspirations – and of course (and usually especially significant) the location in the larger nets of movement and capital web.’ (Buchanan 1988a: 33). Offering a useful point of departure for exploring the diversity of established urban contexts, a study of London’s urban environmental quality (TCKWM 1993) identified eight key factors (Figure 3.2).

Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing

by

John Boughton

Published 14 May 2018

Deck-access entry to homes and walkways joining the blocks offered ‘the social advantage of greater choice of friends amongst neighbours and for old people the advantage of easy contact with the passing world where they want it’, he argued.4 In an updated application of Radburn principles, given impetus by Colin Buchanan’s influential 1963 report, Traffic in Towns, a strict separation of cars and people was embedded into the plans. Garaging was provided, with service roads to the rear base of the blocks, while the busy Stretford Road was transformed into a ‘pedestrian way’. The overall scheme, with a library, doctors’ surgeries, communal laundry and pool, several churches and a range of pubs and clubs, was intended to offer a new but less prescriptive version of Abercrombie’s neighbourhood unit.

…

Holding, et al., ‘A Qualitative Study of the Impact of the UK “Bedroom Tax”’, Journal of Public Health, vol. 38, no. 2, 2016, 119–200, academic.oup.com, accessed 5 May 2017. 23Kathryn Hopkins, ‘Social Housing Builder Genesis Blames Rent Cut as it Slashes Affordable Homes’, Times, 29 October 2015, thetimes.co.uk, accessed 7 May 2017. 24Patrick Butler, ‘Benefit Cap Will Hit 116,000 of Poorest Families, Say Experts’, Guardian, 1 November 2016, theguardian.com, accessed 5 May 2017, and Jenny Pennington, ‘The Benefit Cap: This Changes Everything’, Shelter Policy Blog, 20 July 2015, blog.shelter.org.uk, accessed 5 May 2017. 25Moffatt, Lawson, Patterson, Holding, et al., ‘A Qualitative Study of the Impact of the UK “Bedroom Tax”’, 202. 26Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies (eds), City Villages: More Homes, Better Communities (IPPR, March 2015), 9, ippr.org, accessed 8 May 2017. 27Yolande Barnes, ‘A City Village Approach to Regenerating Housing Estates’, in Adonis and Davies (eds), City Villages, 56. 28Jules Pipe and Philip Glanville, ‘Hackney City Villages’, in Adonis and Davies (eds), City Villages, 82. 29Duncan Bowie, ‘City Villages – The Wrong Solution to London’s Housing Crisis’, Red Brick, 12 January 2016, redbrickblog.wordpress.com, accessed 8 May 2017. 30Savills Research Report to Cabinet Office, Completing London’s Streets: How the Regeneration and Intensification of Housing Estates Could Increase London’s Supply of Homes and Benefit Residents, January 2016, 5, pdf.euro.savills.co.uk, accessed 8 May 2017. 31Caroline Davies, ‘David Cameron Vows to “Blitz” Poverty by Demolishing UK’s Worst Sink Estates’, Guardian, 10 January 2016, theguardian.com, accessed 8 May 2017. 32David Cameron, Estate Regeneration, 10 January 2016, gov.uk, accessed 8 May 2017. 33Haringey Council’s Local Plan Consultation: Response by Broadwater Farm Residents’ Association (24 March 2015), 7, haringey.gov.uk, accessed 9 May 2017. 34Iain Duncan Smith, ‘We Cannot Arrest Our Way Out of These Riots’, Times, 15 September 2011, thetimes.co.uk, accessed 9 May 2017. 35Cameron, Estate Regeneration. 36Space Syntax, 2011 London Riots Location Analysis: Proximity to Town Centres and Large Post-War Housing Estates (2011), image.guardian.co.uk, accessed 9 May 2017. 37Reading the Riots: Investigating England’s Summer of Disorder (Guardian and the London School of Economics, 2011), 4, eprints.lse.ac.uk, accessed 9 May 2017. 38Bob Jeffery and Waqas Tufail, ‘“The Riots Were Where the Police Were”: Deconstructing the Pendleton Riot’, Contention: The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest, vol. 2, no. 2, October 2016, 53, shura.shu.ac.uk, accessed 9 March 2017. 39Social Life, Cressingham Gardens Estate, October 2013, social-life.co, accessed 10 May 2017. 40Save Cressingham Gardens, Petition: Stop Mott MacDonald Profiting from Community Destruction, 6 May 2017, savecressingham.wordpress.com, accessed 10 May 2017. 41Barnet Council, ‘West Hendon Estate, West Hendon, London NW9: Application Summary’, 17 December 2014, barnet.moderngov.co.uk, accessed 13 June 2017. 42Dave Hill, ‘Jasmin Parsons and the Troubled Tale of the West Hendon Estate’, Guardian, 4 November 2015, theguardian.com, accessed 13 June 2017. 43Chris Godfrey, ‘How Council Promises Have Fallen Away, Leaving the West Hendon Estate in Dire Straits’, New Statesman, 28 January 2015, newstatesman.com, accessed 10 May 2017. 44James Caven, ‘“You Are Displacing a Whole Community”: Public Inquiry into West Hendon Estate Starts’, Hendon and Finchley Times, 20 January 2015, times-series.co.uk, accessed 13 June 2017. 45Dave Hill, ‘Earls Court Regeneration: Reviews and Uncertainties’, Guardian, 3 October 2016, theguardian.com, accessed 10 May 2017. 46West Ken and Gibbs Green – The People’s Estates, ‘Residents Launch People’s Plan for Improvements and New Homes Without Demolition’, 21 July 2016, westkengibbsgreen.wordpress.com, accessed 10 May 2017. 47Sam Gelder, ‘Northwold Estate Campaigners Fight Developers over Demolition of Housing Blocks’, Hackney Gazette, 30 November 2016, hackneygazette.co.uk, accessed 11 May 2017. 48Shelter, Shelter’s Response to the CLG’s Consultation – Reform of Council Housing Finance, October 2009, 6, england.shelter.org.uk, accessed 12 May 2017. 49Price Waterhouse Cooper, HRA Reform: One Year On, July 2013, 2, pwc.co.uk, accessed 12 May 2017. 50Janice Morphet, ‘Is Austerity the Mother of Invention? How Local Authorities are Providing Housing Again’, LSE British Politics and Policy, blogs.lse.ac.uk, accessed 11 May 2017. 51UK Government, ‘Table 600: Numbers of Households on Local Authorities’ Housing Waiting Lists, by District, England, from 1997’, gov.uk, accessed 11 May 2017. 52Michael Buchanan and Sophie Woodcock, ‘Councils Spent £3.5bn on Temporary Housing in Last Five Years’, BBC News, 17 November 2016, bbc.co.uk, accessed 11 May 2017. 53Alex Homer, ‘Town Halls Buy Back Right-to-Buy Homes’, BBC News, 3 May 2017, bbc.co.uk, accessed 11 May 2017. 54Haringey Council, ‘Haringey’s Development Partnership – A New Approach to Regeneration’, 11 November 2015, haringey.gov.uk, accessed 13 June 2017. 55Dave Hill, ‘Q&A: Haringey Leader Claire Kober on Borough’s “Development Vehicle” Plans’, 28 February 2017, onlondon.co.uk, accessed 13 June 2017. 56Aditya Chakrabortty, ‘Lives Torn Apart and Assets Lost: This is What a Labour Privatisation Would Mean’, Guardian, 19 January 2017, theguardian.com, accessed 13 June 2017. 57Shelter, ‘Can Haringey’s Housing Development Vehicle Provide a Case Study in Joint Ventures?’

…