Travis Kalanick

description: American businessman best known as the co-founder and former chief executive officer of Uber

136 results

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

the company. As the scandal unfolded, Uber fired twenty employees, and a media firestorm led the company’s top investors to oust CEO and cofounder Travis Kalanick. Fowler’s essay became one of the most impactful pieces of twenty-first-century whistleblowing and made it difficult to fully swallow Silicon Valley’s

…

, 167 Juggalos, the, 91, 269 Juice WRLD, 182, 184 Juicy Couture, 47 “Just Dance” (song), 80 K Kabosu, 238 Kaelin, Kato, 90 Kaepernick, Colin, 144 Kalanick, Travis, 165–66 Karanikolaou, Anastasia “Stassie,” 218 Kardashian, Kim, 83, 96, 277 Hilton and, 48–49 Instagram face, 213–14 Kanye and (Kimye), 114–20, 178

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber

by Mike Isaac · 2 Sep 2019 · 444pp · 127,259 words

recourse to the second. —NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI, 1513 Being super pumped gives us super powers, turning the hardest problems into amazing opportunities to do something great. —TRAVIS KALANICK, 2015 CONTENTS Prologue PART Ⅰ Chapter 1: X TO THE X Chapter 2: THE MAKING OF A FOUNDER Chapter 3: POST-POP DEPRESSION Chapter 4: A

…

business as usual. Since 2009, the company had faced off against legislators, police officers, taxi operators and owners, transportation unions. In the eyes of Travis Kalanick, Uber’s co-founder and chief executive, the entire system was rigged against startups like his. Like many in Silicon Valley, he believed in the

…

and venture capitalists alike, emblematic of both the best and worst of Silicon Valley. The saga of Uber—which is, essentially, the story of Travis Kalanick—is a tale of hubris and excess set against a technological revolution, with billions of dollars and the future of transportation at stake. It’s

…

all, it is a story about how blind worship of startup founders can go wildly wrong, and a cautionary tale that ends in spectacular disaster. Travis Kalanick and his executive team created a corporate environment that looked like an admixture of Thomas Hobbes, Animal House, and The Wolf of Wall Street.

…

out to employees across the world: Uber had passed another milestone. It was time for Uberettos* to celebrate. It was an Uber tradition for Travis Kalanick to take the company on the road after hitting growth targets. Funded by billions of venture capital dollars, the trips were conceived as morale boosters

…

willing to observe with rose-colored lenses. Soon thereafter the world of uninhibited technological progress came to a screeching halt. And so did Uber and Travis Kalanick. There was one other event employees would recall long after leaving the desert. After a day of drinking beer in poolside cabanas, Uberettos checked

…

and IT consulting firm Sapient in 2001. “Anyone trying to start a company in San Francisco back then had to be fucking crazy,” Leathern said. Travis Kalanick apparently was fucking crazy. Almost immediately after Scour closed its doors, Kalanick started brainstorming with Michael Todd, one of his Scour co-founders. In relatively

…

is.” Chapter 3 notes § Kalanick saw to it that the tax withholdings eventually made their way to the IRS. Chapter 4 A NEW ECONOMY Travis Kalanick sold Red Swoosh just as a national crisis was beginning to unfold. It was April 2007. For years, American banks had been doling out loans

…

looked like a tech-world McEnroe or Agassi, power serving against hapless competitors. The JamPad served two primary purposes: a place for Travis Kalanick to crash, and a place for Travis Kalanick and his techie friends to riff on ideas. “Jamming,” in Kalanick parlance, was like playing in a jazz quartet or a psychedelic

…

chief operating officer, though in practice he became “dealmaker in chief.” His real job would eventually enmesh itself with his other job; best friend to Travis Kalanick. Michael and Kalanick became inseparable, chatting strategy and business together throughout the day while spending evenings and weekends hanging out. They would dine together, take

…

tech and automobile companies thought it was possible. He poured millions of his personal wealth into researching flying cars. Larry Page didn’t care about Travis Kalanick; he cared about the future of transportation. Moreover, Kalanick never internalized Page’s philosophy on in-house competition. Larry Page gave his divisions a

…

tactics worked. The lawmakers backed down. Chapter 12 notes ‡‡‡‡ De Blasio got his revenge and imposed a cap in 2019. Chapter 13 THE CHARM OFFENSIVE Travis Kalanick couldn’t figure out why everyone hated his guts. Feelings had no place in the business world. Being cutthroat was a quality to be celebrated

…

Gurley as a gadfly, always harassing Kalanick and poking holes in Kalanick’s ideas. Where Kalanick saw opportunity, Gurley started to see problems. When Travis Kalanick decides he likes someone, they might as well be his best friend. People close to Kalanick describe it as a fragile infatuation, a platonic mini

…

-affair where Kalanick thinks you can do no wrong. Gurley, when the two first met, was the object of Kalanick’s infatuation. When Travis Kalanick decides he doesn’t like someone, they might as well be dead. If someone challenges Kalanick—in the wrong way, not via “principled confrontation”—

…

politics. She was familiar with schmoozers and phony executives. Though she knew her boss had rough edges, she had come to believe that inside, Travis Kalanick was a good person. Hourdajian worked alongside Kalanick through some of Uber’s earliest, toughest days. He trusted her to build out the communications team

…

15 EMPIRE BUILDING For decades, Western technology executives have dreamed of successfully launching an American software business in mainland China. Very few have succeeded. When Travis Kalanick looked at the country he saw a near-perfect market for startups. Home to nearly 1.4 billion people, China presented an untapped ocean of

…

a blank check. But Kalanick had one very important requirement: Uber wouldn’t only play defense. Chapter 18 CLASH OF THE SELF-DRIVING CARS Travis Kalanick was fuming in the grand ballroom of the Terranea Resort—a seaside haven for the rich off the coast of Rancho Palos Verdes, California. It

…

colored stickers and pasted them around the San Francisco headquarters with a message they knew Levandowski would love: “Safety Third.” Their meeting felt almost predestined. Travis Kalanick and Anthony Levandowski were first introduced to one another in 2015 at the suggestion of Sebastian Thrun, a former Google executive and bigwig in the

…

comparing his win to the ascendancy of ruthless dictators like Chairman Mao Zedong in China. But as Trump’s victory became inevitable on election night, Travis Kalanick was beginning to see the silver lining. A Republican administration was less likely to come after Uber, especially if he positioned his company as

…

point, O’Sullivan had never really liked Uber. He had passively followed its various controversies; everyone in tech did. To the leftist O’Sullivan, Travis Kalanick was an avatar of Silicon Valley’s capitalist id, concerned only with user and revenue growth, not the lives of everyday workers like himself. He

…

Uber employee, who again reported him to management. He was terminated and left the company in April 2016. Chapter 23 ...THE HARDER THEY FALL Travis Kalanick woke up to an iPhone on nuclear meltdown. Within hours, the link to Susan Fowler’s blog post had been shared internally, across private messages

…

Amazon if Bezos wanted it. Chapter 24 NO ONE STEALS FROM LARRY PAGE At the end of 2016, months before Susan Fowler’s blog post, Travis Kalanick had a different problem brewing: forty miles south of San Francisco, Larry Page was fuming. Anthony Levandowski—his star pupil and golden child—had

…

of the executive leadership team could understand the data. The results were clear: People enjoyed using Uber as a service. But when you brought up Travis Kalanick, customers recoiled. Kalanick’s negative profile was actively making Uber’s brand worse. Later that day, Jones got a text from Kalanick. The CEO

…

, and different versions of the recommendations would later be distributed. But Holder and Albarrán had put their most important action items at the top: Travis Kalanick needed to take a leave of absence from his own company, relinquish his control of Uber’s business, and hire a proper chief operating officer

…

started doing yoga and meditating. Yet he still couldn’t sleep. Gurley was exhausted. The Holder report event was supposed to contain the fallout. Travis Kalanick was stepping away, the company would take steps to rebuild its brand—there was a possibility everything would shake out just fine. But the meeting

…

it would prove to be one of the most successful tech company venture capital investments of all time. ††††††††† Rubenstein, ironically, had nearly been hired by Travis Kalanick months ago, after the video showing him screaming at a driver went viral. Chapter 29 REVENGE OF THE VENTURE CAPITALISTS The day before Gurley’s

…

angry employees. Huffington had been on CNN earlier that year, claiming that Kalanick had “evolved” in his behavior and defending his capabilities as chief executive. Travis Kalanick, she claimed on live television, was the “heart and soul” of Uber. Huffington had aligned with Kalanick for years until this very moment–

…

as a push notification from the New York Times smartphone app was sent out to the home screens of hundreds of thousands of subscribers simultaneously. “Travis Kalanick resigned as chief executive of Uber after investors began revolting over legal and workplace scandals at the company,” it said. Kalanick was blindsided. He was

…

surrounded by elephants, lions, and hippopotamuses—began calling other board members to notify them of Benchmark’s next move: the firm filed a lawsuit against Travis Kalanick accusing him of defrauding Uber’s shareholders and breaching his fiduciary duty, a stunning act of open warfare between board members at a high-profile

…

” image Benchmark had worked so long to cultivate. Shervin Pishevar, an early Uber backer, came to Kalanick’s defense. In the war of investors versus Travis Kalanick, Pishevar sided with Kalanick. On August 11, Pishevar sent a letter to Benchmark, asking the firm to step down from Ubers’ board of directors.

…

food delivery. Everyone was ready to start trading shares of $UBER. There was some tension leading up to the big day. Khosrowshahi had asked Travis Kalanick not to join him on the balcony for the ceremonial bell-ringing that morning, something that pissed Kalanick off. Word leaked to the press that

…

4 “fast-growing”, “pugnacious”, a “juggernaut”: Kara Swisher, “Man and Uber Man,” Vanity Fair, November 5, 2014, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2014/12/uber-travis-kalanick-controversy. 6 a noun coined in 2013: Aileen Lee, “Welcome to the Unicorn Club: Learning From Billion-Dollar Startups,” TechCrunch, October 31, 2013, https://techcrunch

…

bonnie-kalanick-mother-of-uber-founder-remembered-fondly-by-former-daily-news-coworkers/. 17 an inherent competitive spirit: Chou, “Bonnie Kalanick.” 17 Travis later said: Travis Kalanick, “Dad is getting much better in last 48 hours,” Facebook, June 1, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=10155147475255944&id=564055943. 17

…

, 2008, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB121788532632911239. 20 recalled Sean Stanton: Interview with author, 2017. 21 it occurred to some of them: TechCo Media, “Travis Kalanick Startup Lessons from the Jam Pad—Tech Cocktail Startup Mixology,” YouTube video, 38:34, May 5, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMvdvP02f-Y

…

/jan/29/uber-app-changed-how-world-hails-a-taxi-brad-stone. 44 flourish on Bond’s cell phone: Stone, Upstarts. 46 his personal blog: Travis Kalanick, “Expensify Launching at TC50!!,” Swooshing (blog), September 17, 2008, https://swooshing.wordpress.com/2008/09/17/expensify-launching-at-tc50/. 46 a roomful of

…

of Uber,” Medium, August 22, 2017, https://medium.com/@gc/the-beginning-of-uber-7fb17e544851. Chapter 6: “LET BUILDERS BUILD” 54 “Looking 4 entrepreneurial product”: Travis Kalanick (@travisk), “Looking 4 entrepreneurial product mgr/biz-dev killer 4 a location based service.. pre-launch, BIG equity, big peeps involved—ANY TIPS??,” Twitter, January

…

.com/digits/2013/11/13/snapchat-spurned-3-billion-acquisition-offer-from-facebook/. Chapter 9: CHAMPION’S MINDSET 82 Kalanick once said onstage: Liz Gannes, “Travis Kalanick: Uber Is Raising More Money to Fight Lyft and the ‘Asshole’ Taxi Industry,” Recode, May 28, 2014, https://www.recode.net/2014/5/28

…

://abovethecrowd.com/2014/07/11/how-to-miss-by-a-mile-an-alternative-look-at-ubers-potential-market-size/. 87 In a policy paper published: Travis Kalanick, “Principled Innovation: Addressing the Regulatory Ambiguity Ridesharing Apps,” April 12, 2013, http://www.benedelman.org/uber/uber-policy-whitepaper.pdf. 87 “nervous breakdowns”: Swisher, “

…

Bonnie Kalanick.” 88 Kalanick would tweet: Travis Kalanick (@travisk), “@johnzimmer you’ve got a lot of catching up to do . . . #clone,” Twitter, March 19, 2013, 2.22 p.m., https://twitter.com/

…

Mission Impossible in China,” The Information, January 11, 2016, https://www.theinformation.com/articles/inside-ubers-mission-impossible-in-china. 143 “This kind of growth”: Travis Kalanick, “Uber-successful in China,” http://im.ft-static.com/content/images/b11657c0-1079-11e5-b4dc-00144feabdc0.pdf. 144 sailing out amid the rough waters: Octavio

…

-conference-video. 178 “We get stuff like this”: Biz Carson, “New Emails Show How Mistrust and Suspicions Blew Up the Relationship Between Uber’s Travis Kalanick and Google’s Larry Page,” Business Insider, July 6, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/emails-uber-wanted-to-partner-with-google-on-self-driving-cars

…

to the party #deleteUber,” Twitter, January 28, 2017, 11:33 p.m., https://twitter.com/MM_schwartz/status/825562459088023552. 210 attempted a mealy-mouthed apology: Travis Kalanick, “Standing Up for What’s Right,” Uber Newsroom, https://www.uber.com/newsroom/standing-up-for-whats-right-3. 210 “many people internally and externally

…

.E.O. to Leave Trump Advisory Council After Criticism,” New York Times, February 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/02/technology/uber-ceo-travis-kalanick-trump-advisory-council.html?_r=1. Chapter 22: “ONE VERY, VERY STRANGE YEAR AT UBER . . .” 213 85 percent of Uber engineers were men: Johana

…

Arianna Huffington Says She’s Been Emailing Ex-Engineer About Harassment Claims,” CNBC, March 3, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/03/03/arianna-huffington-travis-kalanick-confidence-emailing-susan-fowler.html. 273 “Uber has a long way to go”: Emil Michael, “Email from Departing Uber Executive,” New York Times, June

…

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/12/technology/document-Email-From-Departing-Uber-Executive.html. 274 “For the last eight years”: Entrepreneur Staff, “Read Travis Kalanick’s Full Letter to Staff: I Need to Work on Travis 2.0,” Entrepreneur, June 13, 2017, https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/295780. 278 Bonderman

…

Chief Is Gaining Even More Clout in the Company,” New York Times, June 12, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/12/technology/uber-chief-travis-kalanick-stock-buyback.html. 288 the two rarely spoke afterwards: Alex Konrad, “How Super Angel Chris Sacca Made Billions, Burned Bridges and Crafted the Best

Wild Ride: Inside Uber's Quest for World Domination

by Adam Lashinsky · 31 Mar 2017 · 190pp · 62,941 words

CHAPTER 11 Outflanked in China CHAPTER 12 A Long Walk Through San Francisco Photographs Acknowledgments About the Author CHAPTER 1 A Wild Ride Through China Travis Kalanick sits in the back of a chauffeur-driven black Mercedes making its way through the traffic-clogged streets of Beijing. It is the dead of

…

walk through the streets of San Francisco; and during numerous additional formal and informal chats after that. Uber’s story isn’t strictly synonymous with Travis Kalanick’s, but he is its central character. In fact, Uber wasn’t initially his idea. Kalanick’s involvement with Uber was part time for the

…

asshole, a ruthless, authority-defying libertarian, admired for his tenacity but reviled for his scorched-earth tactics. That image didn’t sit well with him. Travis Kalanick, even close followers of the Silicon Valley scene might be surprised to know, felt misunderstood. What wasn’t disputable, however, was that he was now

…

how Kalanick and Uber came to be who and what they are—and how they reached such a high pinnacle of success. I first met Travis Kalanick in July 2011, less than a year after he’d become CEO of Uber. The company was tiny then, with just several hundred licensed limousine

…

span of roughly two years, beginning in the middle of 2013, when UberX first took off. At the center of this story, of course, is Travis Kalanick, who came to define what it meant to be a tech entrepreneur in the second decade of the twenty-first century. Kalanick is different from

…

business that has wreaked havoc on incumbent players from taxi companies to rental-car agencies. Operating from a playbook he devised more or less himself, Travis Kalanick also has defied the odds. A college dropout like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg before him, unlike them he knew failure first and

…

as Todd, and Kevin Smilak, another Bay Area native. The student destined to become the club’s most famous member grew up practically next door. Travis Kalanick, who came from the nearby San Fernando Valley and was pursuing a double major in computers and business, quickly gravitated toward the club. He remembers

…

near obsessions for Kalanick a decade later, at Uber. Yet by the end of 2000 Scour was all but gone, and twenty-four-year-old Travis Kalanick, like his closest friends from UCLA, had no college degree and no job. He would need a new plan—and fast. CHAPTER 3 Lean Times

…

’t own that would dwarf the number of cars operated by any competing taxi service. In short, Scour and Red Swoosh represented, at least for Travis Kalanick, a direct through-line to Uber. Most audacious of all was how the young entrepreneurs managed to salvage relationships with the very companies they’d

…

of employees, including Kalanick. His personal deal with Akamai was to stay for three years. “I did one,” he says. CHAPTER 4 Jamming Once again, Travis Kalanick was at a transition point in his career, this time under more favorable circumstances than when Scour cratered six years earlier. Now thirty-one years

…

in the future. The Lobby gathered at the plush Fairmont Orchid on the Big Island of Hawaii, and it was the first time Camp met Travis Kalanick, whose company, Red Swoosh, had been in the portfolio of August Capital. Camp and Kalanick shared a dinner in Hawaii with Evan Williams, cofounder of

…

the creation of UberCab. Uber’s corporate Web site, in a section labeled “Our Story,” would say that “on a snowy Paris evening in 2008, Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp had trouble hailing a cab. So they came up with a simple idea—tap a button, get a ride.” Like other company

…

was straightforward. The company would drop the word “cab” from its name and otherwise ignore the letter. CHAPTER 6 Travis Takes the Wheel The company Travis Kalanick decided to take over in the fall of 2010 was still tiny. It had been operating in a single city, San Francisco, for four months

…

those chosen to hold the distinction of “rider zero” included local tech CEOs, sports stars, and other influential personalities. In Los Angeles, in early 2012, Travis Kalanick’s parents were joint Rider Zero; the actor Edward Norton, an Uber investor and ardent celebrity cheerleader for the company, was Rider One. For all

…

phone,’” says Gurley. “He would say that over and over again: ‘If I could only have one app on my phone, it would be this.’” Travis Kalanick was more prepared than most entrepreneurs to raise money. After all, he had learned the craft under far less advantageous circumstances, having scraped together funding

…

.” The acrimony over a topic that was simultaneously wonky and relatable to any passenger also helped introduce the public to a new global commercial character: Travis Kalanick, the “asshole.” Suddenly a public figure with his face on the cover of magazines and a highly sought-after speaker on the conference circuit, Kalanick

…

question too, and soon enough he would address it. David Krane was on the verge of completing the most important deal of his life when Travis Kalanick called him and began the conversation by saying, “Hear me out.” These were not the words he wanted to hear. Krane’s career had followed

…

drivers, even women: all could justifiably feel aggrieved by something Uber said or did. Its offender-in-chief was its public face and chief executive, Travis Kalanick, who prided himself on speaking his mind. He seemed incapable, in public or in private, of holding back, as if his outspokenness were a DNA

…

. The Rideshare Guy has gotten big enough that Campbell now has writers working for him. One, John Ince, wrote a critique of an onstage interview Travis Kalanick did in late 2016 with Graydon Carter, the editor of the magazine Vanity Fair. “The interview is revealing not because of what Kalanick says,” Ince

…

service, Uber barely needed to manage its volunteer army of drivers. In the summer of 2013, with his business booming yet barely three years old, Travis Kalanick confronted Uber’s own potential disruption: autonomous vehicles, also known as self-driving cars. The development was so potentially game-changing that it could eliminate

…

its sights. One application of its wholly automated car, Google said, was a smartphone app that could summon and direct driverless taxis. By this time, Travis Kalanick was paying careful attention. The same executive Kalanick asked to revamp product development would be his liason to the advent of self-driving cars. Jeff

…

, Android, and also paved the way for its own eventual self-driving taxi service. Looming largest for Uber, at least in the ultracompetitive mind of Travis Kalanick, were Tesla and its founder, Elon Musk. Tesla had added a controversial feature to its electric cars called Autopilot, a kind of glorified cruise control

…

-star hotel on the outskirts of town, the general managers of Uber China settled in for a no-holds-barred question-and-answer session with Travis Kalanick. On the agenda was the state of the affairs in one of Uber’s most high-profile and problematic markets. They sat at four tables

…

-out contest with Didi. The angst of the executives also showed an uncomfortable truth: Uber China may legally have been an independent Chinese entity, but Travis Kalanick was calling the shots for it from San Francisco. Indeed, unable to find the right candidate to lead the country overall, Kalanick personally had been

…

Lyft and unlike Uber, Didi allowed tipping, a driver favorite. Didi also had something of a chip on its shoulder, an emotion not foreign to Travis Kalanick. Mindful that Baidu had arisen as the leading Chinese Internet search engine not so much because it was the best but because government policy made

…

I’ve arrived at Uber’s San Francisco headquarters building at this unusual hour for what has been promised to be a long interview with Travis Kalanick. I’m told he has blocked out two hours for our chat. Having a business meeting at this hour is a bit out of the

…

Uber’s work space was to understand Uber itself. It was also clear that divining Uber was the key to knowing the true nature of Travis Kalanick. “You know when, like, a city is made from scratch?” he asks. “You’ve got clean lines everywhere. This is like a manufactured city. So

…

the “Travis” he has picked up—all Uber drivers have the first name of their paying passenger—is the company’s CEO. DRIVER: Are you Travis? KALANICK: Yeah. How you doing, man? DRIVER: I never met you. KALANICK: Yeah, yeah. DRIVER: How you doing, man? KALANICK: I’m good, I’m good

…

do that, when you’re doing something really, really different, you’re going to have some naysayers. You just have to get used to that.” Travis Kalanick, the philosopher/execution guy, a jerk to many but not to himself, very likely will never get used to the naysayers. Adversity, after all, had

…

become part of the journey. A young Travis Kalanick. Kalanick’s fourth-grade football team; he’s number 21. The Scour team on the last day of its existence. From left to right, Kevin

…

Smilak, Craig Grossman, Travis Kalanick, Dan Rodrigues, and Michael Todd. The Red Swoosh team in 2002: Travis Kalanick (second from left), Francesco Fabbrocino (standing, fourth from left), Evan Tsang (third from right), Rob Bowman (far right). Garrett

…

Camp (left) and Travis Kalanick in front of the Eiffel Tower during their pivotal 2008 trip. The Uber team in the beginning. From

…

left to right: Curtis Chambers, Travis Kalanick, Stefan Schmeisser, Conrad Whelan, Jordan Bonnet, Austin Geidt, Ryan Graves, Ryan McKillen. The early UberCab Web site. Edward Norton was Rider One in Los Angeles

…

in 2012. Ryan Graves and Austin Geidt jamming in Uber’s early days. Shervin Pishevar and Travis Kalanick, moments after signing the term sheet for Series B funding in Dublin, October 2011. Kalanick with two employees at Uberversity Happy Hour, an event for

The Upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb, and the Killer Companies of the New Silicon Valley Are Changing the World

by Brad Stone · 30 Jan 2017 · 373pp · 112,822 words

CEO of that once-fledgling company, Airbnb. “It was the coldest morning of my life. Everyone cheered when the sun came up.” Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick also attended the festivities that week, and their experience was nearly as ignominious. A friend on the inaugural committee, the investor Chris Sacca, had convinced

…

consequences to their approaches that even Uber and Airbnb did not anticipate. At the center of this maelstrom are the young, wealthy, charismatic chief executives: Travis Kalanick and Brian Chesky. They represent a new kind of technology CEO, nothing at all like Bill Gates, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg, the awkward,

…

looking to score political points by vilifying a high-profile target; others are legitimately worried about Airbnb’s impact on housing affordability. Unlike his friend Travis Kalanick, Chesky presents himself as a sympathetic ally of those in the latter category. “We want to enrich cities. We don’t want to be

…

ahead of time, sitting in on conversations, and taking copious notes. Then there was the monumental challenge of obtaining the cooperation of the famously combative Travis Kalanick, known as a contrarian who advocated fiercely for his company’s interests. He did not disappoint. “I came to this meeting out of respect for

…

officially in development. And so Camp left for Paris and the LeWeb conference, where he was meeting McCloskey and a close friend and fellow entrepreneur—Travis Kalanick. Every company creates its own origin myth. It’s a useful tool for expressing the company’s values to employees and the world and for

…

one. This was only a limo company, a new way to shepherd relatively affluent users around the city in style. So on January 5, 2010, Travis Kalanick Tweeted in the peculiar shorthand common to the 140-character messaging service: Looking 4 entrepreneurial product mgr/biz-dev killer 4 a location based service

…

involved enough or because they saw the concept as an extravagant indulgence for wealthy urbanites. Some said no because they had worked with the combative Travis Kalanick before at his previous companies and didn’t want to deal with the aggravation again; others because they knew the company was going to run

…

be shut down. So on October 20, 2010, four months after the launch, when Graves was at a board meeting at First Round Capital with Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, four government enforcement officers walked into the tiny UberCab office. Two were from the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulated limousines and

…

it. —Travis Kalanick1 Around the same time Brian Chesky was warned about the Samwer brothers, someone much closer to home was making life difficult for Travis Kalanick and the small band of employees at the city’s other rising startup, Uber. The four plainclothes enforcement officers who had served Uber with its

…

was in the board meeting at First Round Capital. Graves stepped outside to call her, then returned to the office to discuss the situation with Travis Kalanick, Garrett Camp, and investors Chris Sacca and Rob Hayes. The letter threatened penalties of five thousand dollars per ride and ninety days in jail for

…

with regulating limos and town cars, and they orchestrated the joint cease-and-desist. After receiving the threatening letter, Uber promptly asked for a meeting. Travis Kalanick, Ryan Graves, and Uber’s outside lawyer Dan Rockey met Hayashi and other city and state officials on November 1 in a conference room on

…

Brown knows Airbnb,” Chesky says. “It was this crescendo. It was an airplane, reaching a higher and higher elevation.” In May, Chesky met fellow traveler Travis Kalanick for the first time. At a conference in New York City called TechCrunch Disrupt, Chesky and Kalanick were invited to appear onstage together in a

…

ve never seen an entrepreneur work as hard. He lives, eats and breathes Uber. —Shervin Pishevar, e-mail to his partners at Menlo Ventures To Travis Kalanick, Uber wasn’t merely a fecund investment opportunity or a promising startup with an auspicious set of early results. As he described it at the

…

CEO Jeff Bezos told board member Bill Gurley after a surge fracas, according to Gurley. “Most CEOs would have caved.” In the fall of 2011, Travis Kalanick once again set out to raise capital. The rancor surrounding surge pricing would be nothing compared to the animosity that was about to be unleashed

…

to Washington, DC, city council members1 Until this point in its brief but eventful history, Uber had moved with relative caution into new cities. Though Travis Kalanick and his colleagues had come to distrust taxi ordinances as schemes designed to protect incumbents and their shoddy levels of service from new competition, they

…

ground zero in the ridesharing movement. It was the first to regulate the ridesharing upstarts, and its deliberations were being closely watched—not only by Travis Kalanick at Uber but by other states who knew the ridesharing phenomenon would be coming to them soon. Nearly the first thing Kennedy did was stride

…

limo companies all arrived separately, stating their gripes against Lyft and Sidecar but also Uber and, comically, one another, based on decades of simmering hatreds. Travis Kalanick also visited the CPUC conference room on the fifth floor that fall, with Hallisey, his attorney, and general counsel Salle Yoo. He made a lasting

…

Lyft expanded into Los Angeles and Sidecar moved more aggressively into L.A., Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Austin, Brooklyn, and DC. The ridesharing wars had begun. Travis Kalanick had watched, waited, and even quietly agitated for Lyft and Sidecar to be shut down. Instead, they spread, undercutting Uber’s prices. Now that their

…

increasingly hostile reception in cities like San Francisco, Barcelona, Amsterdam, and particularly New York City, its largest market at the time. Throughout 2012, Johnson watched Travis Kalanick’s fiery battles in DC, San Francisco, and elsewhere, and believed Airbnb had to do things differently than Uber. She talked about ethereal concepts like

…

unions, and all of their powerful allies in government. The upstarts were about to unleash events in Silicon Valley and around the world that neither Travis Kalanick nor Brian Chesky could possibly have envisioned. PART III THE TRIAL OF THE UPSTARTS CHAPTER 10 GOD VIEW Uber’s Rough Ride Anything you can

…

predict, I expect you to handle. —Travis Kalanick to Uber CTO Thuan Pham The Facebook IPO on May 18, 2012, had been a messy affair, with technical problems in the NASDAQ that delayed

…

of their dominance outweigh the well-publicized drawbacks? What was their true impact on cities? Were they good for society or bad? Facing these questions, Travis Kalanick and Brian Chesky, both shedding the baggage of their pasts, would have to rise to meet the future with credible testimony on behalf of their

…

sure that it liked what it saw. Back in the summer of 2013, just as Silicon Valley investors were moving from optimism to outright exuberance, Travis Kalanick set out to raise Uber’s fourth round of financing. Colleagues say Kalanick set the terms of the financing round himself. He initiated discussions with

…

first, Uber denied any involvement. We can confirm that this accident DID NOT involve a vehicle or provider doing a trip on the Uber system, Travis Kalanick Tweeted the afternoon after the accident.10 When more facts emerged, Uber released a more carefully worded abrogation of responsibility that, even coming after a

…

constantly vied not only to capture new drivers but to poach one another’s. It was bare-knuckle competition, the kind of junkyard brawling that Travis Kalanick loved—so Uber excelled at it. Inside the company, employees called it slogging, only later ginning that word into an acronym for a meaningless term

…

Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk were each worth $1.5 billion on paper and joined the Forbes billionaires list the same year as Travis Kalanick, Garrett Camp, and Ryan Graves from Uber.4 They were all in their thirties. There was another, more unfortunate parallel between the companies. Like Uber

…

held technology startup in history. The rise of ridesharing also sparked another wave of conflict in nearly every major city and country in the world. Travis Kalanick had promised a more optimistic and mature style of leadership during Uber’s PR calamities of 2014, but while he toned down his rhetoric, he

…

Kuaidi was going to be financially ruinous for everyone involved. Didi’s and Kuaidi’s investors eventually realized the folly of their mounting rivalry. With Travis Kalanick starting to eye China as Uber’s next big opportunity, they urged an armistice between the two startups and their corporate backers. The savvy Russian

…

recalled when Uber was composed of only a few employees sitting around a cramped conference-room table in borrowed offices near the Transamerica Pyramid. Then Travis Kalanick took the podium, looking nervous and emotional, with his parents sitting in the first row. Over the next twenty minutes, speaking awkwardly from a

…

capital, political connections, a great many thousands of fervent customers, and the grand arc of history itself on its side. In the fall of 2015, Travis Kalanick treated his five thousand employees to a lavish, four-day, all-expenses-paid retreat in Las Vegas. It was part all-hands meeting, part gaudy

…

an entrepreneur is how well he or she can identify new opportunities, and so, not surprisingly, in the fall of 2016, both Brian Chesky and Travis Kalanick were ready to talk about the future. In October, I visited Airbnb at its bustling headquarters on Brannan Street. As usual, the impressive three-story

…

And having dinner in Japan with a sumo wrestler sounded delicious. A few weeks later, with Uber’s battle in China finally over, I visited Travis Kalanick in his San Francisco headquarters for our last interview. Unlike Chesky, he wasn’t pitching anything, though Uber was just as actively rethinking its future

…

And there’s going to be a very, very different world in terms of how we experience our cities. We are just getting started.” Both Travis Kalanick and Brian Chesky had made big promises: to eliminate traffic, improve the livability of our cities, and give people more time and more authentic experiences

…

of the author) An early screenshot in 2010 of the UberCab website. (Courtesy of the author) The early Uber crew: (left to right) Curtis Chambers, Travis Kalanick, Stefan Schmeisser, Conrad Whelan, Jordan Bonnet, Austin Geidt, Ryan Graves, and Ryan McKillen. (Courtesy of Uber) Early Uber executives Ryan Graves and Austin Geidt pondering

…

AP Photo) Taxi drivers demonstrate against Uber, in Cali, Colombia, on June 28, 2016. (Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty Images) Uber co-founders Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick in front of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. (Courtesy of Uber) Lyft President John Zimmer wearing a frog costume to promote the ridesharing service Zimride

…

value in a deep look at a momentous era in Silicon Valley history. At Uber, thanks go to Jill Hazelbaker, David Plouffe, Nairi Hourdajian, and Travis Kalanick and his executives. At Airbnb, I’m grateful to Kim Rubey, Maggie Carr, and Mojgan Khalili, as well as Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, Nathan

…

. M. G. Siegler, “StumbleUpon Beats Skype in Escaping eBay’s Clutches,” TechCrunch, April 13, 2009, http://techcrunch.com/2009/04/13/ebay-unacquires-stumbleupon/. 3. “Travis Kalanick, Uber and Loic Le Meur, Co-Founder, LeWeb,” YouTube video, December 13, 2013, https://youtu.be/vnkvNQ2V6Og. 4. Siegler, “StumbleUpon Beats Skype.” 5. Erin Biba

…

10 Applications That Make the Most of Location,” Wired.com, January 19, 2009, http://www.wired.com/2009/01/lp-10coolapps/. 6. “Fireside Chat with Travis Kalanick and Marc Benioff,” September 17, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zt8L8WSSr1g. 7. David Cohen, “The Pony’s Lucky Horseshoe,” Hi, I’m David

…

November 3, 2010, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-11-03/the-new-new-andreessen. Chapter 5: Blood, Sweat, and Ramen 1. “Disrupt Backstage: Travis Kalanick,” YouTube video, June 22, 2011, https://youtu.be/0-uiO-P9yEg. 2. Ilene Lelchuk, “Probe Clears 2 S.F. Elections Officials; Case Against 3rd Remains

…

, “What Makes Uber Run,” Fast Company, September 8, 2015, http://www.fastcompany.com/3050250/what-makes-uber-run. 7. Ibid. 8. “Travis Kalanick Startup Lessons from the Jam Pad.” 9. “Travis Kalanick of Uber,” This Week in Startups, YouTube video, August 16, 2011, https://youtu.be/550X5OZVk7Y. 10. “Power Tools,” Time, April 24,

…

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB928970934179363266. 13. Ibid. 14. Marc Graser and Justin Oppelaar, “Scour Power Turns H’wood Dour,” Variety, June 24, 2000. 15. “Travis Kalanick of Uber,” This Week in Startups. 16. Karen Kaplan and P. J. Huffstutter, “Multimedia Firm Scour Lays Off 52 of Its 70 Workers,” Los Angeles

…

.ecommercetimes.com/story/6043.html. 18. “FailCon 2011—Uber Case Study,” YouTube video, November 3, 2011, https://youtu.be/2QrX5jsiico. 19. Ibid. 20. Ibid. 21. Travis Kalanick, interview by Ashlee Vance, September 30, 2011. 22. “FailCon 2011—Uber Case Study,” YouTube video. 23. Ibid. 24. Michael Arrington, “Payday for Red Swoosh: $

…

-look-at-ubers-dynamic-pricing-model/. 12. Kara Swisher, “Man and Uber Man,” Vanity Fair, December 2014, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2014/12/uber-travis-kalanick-controversy. 13. Alex Konrad, “How Super Angel Chris Sacca Made Billions, Burned Bridges and Crafted the Best Seed Portfolio Ever,” Forbes, March 25, 2015,

…

the gay community rides and solicited donations as payment. Sunil Paul says he tried the service on a trip to the airport in 2011. 21. “Travis Kalanick of Uber,” This Week in Startups, YouTube video, August 16, 2011, https://youtu.be/550X5OZVk7Y. 22. Tomio Geron, “Ride-Sharing Startups Get California Cease

…

Roll Out Ride Sharing in California,” Bits Blog, New York Times, January 31, 2013, http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/31/uber-rideshare/. 26. Travis Kalanick, “@johnzimmer You’ve Got a Lot of Catching Up,” Twitter, March 19, 2013, https://twitter.com/travisk/status/314079323478962176. 27. David Pierson, “Uber Fined $

…

Uber Driver Speaks Out,” ABC7 News, December 9, 2014, http://abc7news.com/business/mother-of-girl-fatally-struck-by-uber-driver-speaks-out/429535/. 10. Travis Kalanick, “@connieezywe Can Confirm,” Twitter, January 1, 2014, https://twitter.com/travisk/status/418518282824458241. 11. “Statement on New Year’s Eve Accident,” Uber, January 1, 2014

…

/04/24/lyft-24-new-cities/. 22. Kara Swisher, “Man and Uber Man,” Vanity Fair, December 2014, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2014/12/uber-travis-kalanick-controversy. 23. Sara Ashley O’Brien, “15 Questions with… John Zimmer,” CNN, http://money.cnn.com/interactive/technology/15-questions-with-john-zimmer/. 24.

Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work

by Alex Rosenblat · 22 Oct 2018 · 343pp · 91,080 words

8. A screenshot of an email from Uber in 2016, illustrating how the company disciplines drivers who refuse too many uberPOOL requests 9. Uber CEO Travis Kalanick leaning in for a heated debate with his uberBlack driver 10. Uber’s stated policy on cancellation fees as of May 30, 2015 11. Uber

…

SILICON VALLEY It shouldn’t be surprising that Uber has adopted the myth of tech entrepreneurship: after all, the company was started by such entrepreneurs. Travis Kalanick, the most visible cofounder of Uber, is hailed as one of Silicon Valley’s “Great Men.” The Great Man theory of success celebrates America’s

…

and others—the state, networks, capital, and so on—that can make them successful. The message is that it takes a Steve Jobs or a Travis Kalanick, not a village. The dedication it takes to get your start-up off the ground is not the same dedication it takes to pee into

…

has designed in its own favor. While drivers had long been aware of Uber’s ham-fisted treatment of them, a video capturing Uber CEO Travis Kalanick in an encounter with an Uber driver showcased this dynamic to a wider public in February 2017 (see figure 9).32 Figure 9. Uber CEO

…

Travis Kalanick leaning in for a heated debate with his uberBlack driver. This is a screenshot of the video about the incident posted on YouTube in 2017.

…

give us pause. Algorithmic systems can treat similarly situated users differently, even if the systems are supposedly operating neutrally. Take Uber’s surge-pricing algorithm. Travis Kalanick, Uber’s cofounder and former CEO, reiterated the neutrality of Uber’s surge algorithm when he said, with reference to surges, “We are not setting

…

Apple’s fraud detection protocols by manipulating what Apple’s app-review team would see when approving the Uber app. Under orders from then-CEO Travis Kalanick, Uber’s engineers duped Apple for a time by building a “geofence” around Apple’s corporate headquarters in Cupertino, California. Anyone within that geofence (e

…

give it a better grade.) In a meeting that took place years before the event became public knowledge, Apple CEO Tim Cook summoned a nervous Travis Kalanick to his office to discuss Uber’s willful disregard for Apple’s rules. Kalanick agreed to comply properly. Between 2016 and 2017, Uber’s many

…

, and it stuck with me for a while. He mused that Uber’s conflicts were about the new world, represented by leaders like Uber cofounder Travis Kalanick, coming into direct contact with the old world of compliance, law, hierarchy, and order. The clash is big, public, and polarizing. In California, where Uber

…

impossible deadline. It was an organization in complete, unrelenting chaos.”67 Ultimately, the fallout from this controversy culminated in the departure of Uber’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, in June 2017.68 In the wake of these events, Uber endeavored to ally with the cause of “women who code” by pledging a $1

…

disgust and admiration for the sheer boldness and cleverness of its daring feats. Responding to the controversy, Perri Chase, a founder of Unroll.Me, said: Travis Kalanick is out of control and no one can stop him. No one except a board who refuses to hold him accountable for his disgusting behavior

…

after a cluster of scandals. In the 2017 spring roundup of Uber’s failings, including the sexual harassment scandals86 that culminated in the departure of Travis Kalanick,87 the company selected Dallas and Dubai as the cities where it planned to launch flying cars in 2020.88 Just a few months after

…

. And the terms that Uber has set for its drivers shapes the terms on which we negotiate technology’s role in the future of work. Travis Kalanick, Uber’s most prominent cofounder, has come to represent Silicon Valley warrior-kings. Despite Uber’s status as a “decacorn” and its valuation of approximately

…

-484696894139. 44. Mike Isaac, “Uber’s C.E.O. Plays with Fire,” New York Times, April 23, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/04/23/technology/travis-kalanick-pushes-uber-and-himself-to-the-precipice.html; Ali Griswold, “Oversharing: Waymo Hits Uber Where It Hurts, Instacart Talks Cash-Flow, and Airbnb Dorm Rooms

…

-economy. 21. Mike Isaac, “Uber’s C.E.O. Plays with Fire,” New York Times, April 23, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/04/23/technology/travis-kalanick-pushes-uber-and-himself-to-the-precipice.html. 22. Other researchers have found similar speculation among drivers. See, e.g., Mareike Glöss, Moira McGregor, and

…

-liberal-narcissism.html. 34. Johana Bhuiyan, “A New Video Shows Uber CEO Travis Kalanick arguing with a Driver over Fares,” ReCode, February 28, 2017, www.recode.net/2017/2/28/14766964/video-uber-travis-kalanick-driver-argument. 35. Julia Carrie Wong, “Uber CEO Travis Kalanick Resigns Following Months of Chaos,” The Guardian, June 21, 2017, www

…

.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jun/20/uber-ceo-travis-kalanick-resigns. 36. Rosenblat, “What Motivates Gig Economy Workers.” 4. THE SHADY

…

/902639193033240580. 48. Mike Isaac, “Uber’s C.E.O. Plays with Fire,” New York Times, April 23, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/04/23/technology/travis-kalanick-pushes-uber-and-himself-to-the-precipice.html. 49. See, e.g., Julie E. Cohen, Configuring the Networked Self: Law, Code, and Play of Everyday

…

his great work building this partnership and our fantastic counterparts in the organization.” Nikolenka, Instagram, June 29, 2017, www.instagram.com/p/BV74IA-g6Pi/. 51. Travis Kalanick, “Record Shouldn’t Bar Ex-offenders from Work,” Uber Under The Hood, October 5, 2016, https://medium.com/@UberPubPolicy/record-shouldnt-bar-ex-offenders-from

…

Behind as Uber Promises Change at the Top,” The Guardian, June 17, 2017, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/17/uber-drivers-homeless-assault-travis-kalanick. 81. Eric Newcomer and Olivia Zaleski, “When Their Shifts End, Uber Drivers Set Up Camp in Parking Lots across the U.S.,” Bloomberg Technology, January

…

-1501786430. 84. Mike Isaac, “Uber’s C.E.O. Plays with Fire,” New York Times, April 23, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/04/23/technology/travis-kalanick-pushes-uber-and-himself-to-the-precipice.html. 85. Julia Carrie Wong, “Uber’s ‘Hustle-Oriented’ Culture Becomes a Black Mark on Employees’ Résumés,” The

…

Guardian, March 7, 2017, www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/mar/07/uber-work-culture-travis-kalanick-susan-fowler-controversy. 86. Susan J. Fowler, “Reflecting on One Very, Very Strange Year at Uber,” February 19, 2017, Susan Fowler (blog), www.susanjfowler.com

…

on, 6, 222n14; Uber’s surveillance of, 13–14, 161 JPMorgan Chase, 57 Juneau, Alaska, 169 Juneau Taxi and Tours, 169 Juno, 51, 52, 154 Kalanick, Travis: criticisms of, 173, 190, 191; departure as CEO by, 188, 195, 204; incident with driver of, 104–5, 104 fig., 168, 238n33; legacy of, 81

The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

by Sebastian Mallaby · 1 Feb 2022 · 935pp · 197,338 words

. A few years into its existence, Founders Fund made an expensive error by refusing to invest in the ride-hailing startup Uber; its bratty founder, Travis Kalanick, had alienated both Howery and Nosek. “We should be more tolerant of founders who seem strange or extreme,” Thiel wrote, when Uber had emerged as

…

people immediately,” Gurley recalls thinking.[35] But again he showed the discipline to control his excitement. When he met Uber’s founders, Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick, he was not impressed to learn that neither of them would commit full time to the business. Instead, they had recruited a young CEO named

…

company was looking for a Series A investor, and it had undergone a change: the young Ryan Graves had shifted to a lesser job, and Travis Kalanick had become the full-time chief executive. This put Uber in an entirely new light. Kalanick had two previous startups under his belt, and he

…

REFERENCE 50 Asked in 2019 whether Founders Fund would press the founder-friendly principle as far as not firing a clearly problematic leader such as Travis Kalanick of Uber, Trae Stephens replied that Founders Fund would not have removed Kalanick. Stephens, author interview. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 51 Cyan Banister was a

…

denied the allegations in the suit, saying, “The lawsuit is completely without merit and riddled with lies and false allegations.” Mike Isaac, “Uber Investor Sues Travis Kalanick for Fraud,” New York Times, August 10, 2017. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 79 Benchmark Capital Partners VII, L.P., v

…

. Travis Kalanick and Uber Technologies, Inc. (2017), online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/BenchmarkUberComplaint08102017.PDF. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 80 Press reports portray Khosrowshahi and Goldman Sachs

…

United States. 2017 Building on its success with Palantir and SpaceX, Founders Fund backs a third defense contractor, Anduril. 2018 Benchmark and its allies oust Travis Kalanick, Uber’s founder, demonstrating the limits to “founder friendliness.” 2019 WeWork’s failed IPO demonstrates the dangers of hands-off venture tourists who neglect corporate

…

eBay investment, 166–71, 302 founding of Benchmark, 161–62, 163–64 Golden State Warriors investment, 302 Jamba Juice investment, 163–64 Starbucks investment, 163 Kalanick, Travis, 351–71 Andreessen Horowitz’s investment, 353–55, 378 Benchmark and Gurley, 351–56, 358–71, 372, 380, 458n Founders Fund and, 211, 444n Gurley

…

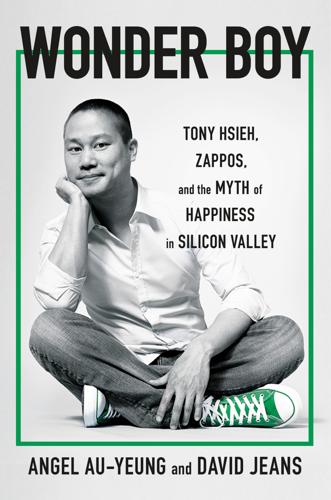

, they achieved “unicorn” status: their valuations shot past the $1 billion mark, even as they remained private. WeWork’s Adam Neumann (left) and Uber’s Travis Kalanick (middle) became the poster children for the risks in this state of affairs: as passive growth investors showered them with capital, unicorn founders could be

Brotopia: Breaking Up the Boys' Club of Silicon Valley

by Emily Chang · 6 Feb 2018 · 334pp · 104,382 words

that revealed forty-seven cases of sexual harassment, resulting in the departure of twenty employees. In a dramatic climax, Uber’s investors forced out CEO Travis Kalanick. Many women who have been victimized have been silenced by a long tradition of settlements and nondisparagement agreements, especially in the tech industry. A few

…

his home near Lake Tahoe, California, to brainstorm and bond with up-and-coming entrepreneurs. He noted how impressed he was by then Uber CEO Travis Kalanick’s endurance. “Travis can spend eight to ten hours in a hot tub. I’ve never seen a human with that kind of staying power

…

again at the epicenter of public backlash. A couple of weeks earlier, a wave of users had deleted the app over perceptions that then CEO Travis Kalanick was aligned with newly elected President Trump. And before that, Kalanick had caught flack for making a joke in response to a question about his

…

.” Employees felt optimistic that TK had publicly taken responsibility, but they wanted to see him take action. (I’ve heard some people say that if Travis Kalanick wasn’t “an asshole,” Uber never would have soared to a $70 billion valuation. But nobody stops to think that if he were less of

…

safe and respected.” • • • LOOKING BACK OVER THE controversy she kicked off, Fowler told me she never once fathomed that her blog post could take down Travis Kalanick, but she felt it was the only way that Uber’s culture could ever improve. “Thinking they are above any sort of moral decency, that

…

with George Clooney for presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, was one of Uber’s most influential backers; he maintained an especially close relationship to co-founder Travis Kalanick. Geidt, who joined Uber as its fourth employee and its first woman, was in charge of launching the ride-sharing company in new cities at

…

that time, however, Kleiner didn’t typically invest at such an early stage. Later, she encouraged the partners to meet with Uber’s then-CEO Travis Kalanick as he was raising the Series B, but there was little interest. Given the juggernaut that Uber became—despite its cultural issues—clearly this was

…

HR may not be surprising, given that open relationships were being explored at the highest levels of the Uber organization. At the time, then-CEO Travis Kalanick was dating Gabi Holzwarth, a violinist. Holzwarth entered the Silicon Valley scene when Uber investor Shervin Pishevar hired her to play at a fundraiser at

…

pattern: angry accusations followed first by denials and then by public mea culpas. Several powerful men in Silicon Valley, including the once-untouchable Uber CEO Travis Kalanick and the investors Justin Caldbeck, Dave McClure, Chris Sacca, Steve Jurvetson, and Shervin Pishevar subsequently resigned, were fired, or were publicly disgraced. There were moments

…

Top Exec Obtaining the Medical Records of a Rape Victim in India,” Recode, June 11, 2017., https://www.recode.net/2017/6/11/15758818/uber-travis-kalanick-eric-alexander-india-rape-medical-records. Uber finally revealed the results: Mike Isaac, “Uber Fires 20 Amid Investigation into Workplace Culture,” New York Times, June

…

/uber-report-eric-holders-recommendations-for-change.html. his own “selfish ends”: Mike Isaac, “Uber Investor Sues Travis Kalanick for Fraud,” New York Times, Aug. 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/10/technology/travis-kalanick-uber-lawsuit-benchmark-capital.html. A Kalanick spokesperson: Ibid. sued Uber (while she was still employed): Heather

Whistleblower: My Journey to Silicon Valley and Fight for Justice at Uber

by Susan Fowler · 18 Feb 2020 · 205pp · 71,872 words

to it on Twitter, it had been retweeted by reporters and celebrities and was a “developing story” covered by local, national, and international news outlets. Travis Kalanick, then the CEO of Uber, shared a link to my blog post on Twitter and said, “What’s described here is abhorrent & against everything we

…

Google that was developing self-driving cars, sued Uber for patent infringement and trade secret theft. Less than a week later, a video leaked of Travis Kalanick berating an Uber driver. And that was only the beginning. By the time I found myself across the table from President Obama’s attorney general

…

ran an investigation into Uber’s culture, and reported that the Vegas trip had been an incredibly extravagant—and debauched—company gathering. Uber’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, had arranged for the entire company to fly into Vegas and party for a few days. There was unlimited alcohol, food, and entertainment. Beyoncé—who

…

why. On the last day of Uberversity, we had an hour-long Q&A with “TK,” who, we all finally realized, was Uber’s CEO, Travis Kalanick. Afterward, the entire class of new recruits and several members of the Uberversity training staff gathered on the stage for a photo. Nearly everyone in

…

dancing. I didn’t understand why more people weren’t out there, enjoying the party. As I stood there, surveying the scene, I realized that Travis Kalanick was standing right next to me. I turned to him. “Why isn’t anyone dancing?” I yelled over the music, pointing to the sidelines where

…

came into work to tear down, not to build up. Uber’s success was due, in large part, to its aggressive disregard for the law; Travis Kalanick and his team were operating in cities across the world without permission, unashamedly breaking and disregarding laws and regulations—all in the name of “hustle

…

world reflected back at them, reinforcing their awful behavior. It was generally understood that the entire mess came from the very top; it seemed that Travis Kalanick and Thuan Pham liked watching their employees fight against each other. Anytime I’d meet with my skip-level manager, Kevin, he’d tell me

…

, I would pull the book out in between meetings, reading as I walked up and down the halls of Uber’s headquarters, sometimes walking past Travis Kalanick, who would be pacing around the building, talking on his phone. I started to feel that I had more control over my life. By defining

…

—a number that continued to grow as Twitter and the media covered Uber’s connections to the Trump administration. Alongside other CEOs like Elon Musk, Travis Kalanick had joined Trump’s economic advisory council shortly after the election; now, in light of the Muslim ban, Uber’s employees and customers were pressuring

…

and what I’d written. It didn’t take long for Uber to discover what I’d done. Several hours after the post went live, Travis Kalanick retweeted it, saying, “What’s described here is abhorrent & against everything we believe in. Anyone who behaves this way or thinks this is OK will

…

single day. I was able to push aside the small stories, but the bigger ones were impossible to ignore. The day after my blog post, Travis Kalanick and Uber hired Eric Holder, the former U.S. attorney general under President Obama, and Tammy Albarrán, a partner at the law firm Covington & Burling

…

inside. Waymo, a Google subsidiary that was developing self-driving cars, sued Uber for patent infringement and trade secret theft, and a video leaked of Travis Kalanick berating an Uber driver. There was something validating about all the stories that were finally coming out about problems at Uber, because they proved to

…

the broken culture at Uber, at the very top of the list was the most important recommendation of all: “Review and Reallocate the Responsibilities of Travis Kalanick.” Immediately after the report was released, Kalanick took an indefinite leave of absence. On June 21, succumbing to pressure from Uber’s major investors, Kalanick

…

resigned. * * * — When I heard the news of Travis Kalanick’s resignation and read through Eric Holder’s report, I felt like a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I thought back to the

…

, I felt like I was truly the subject, not the object, of my own life. I was free. * * * — The day after the news broke that Travis Kalanick had resigned, I took a Lyft home from the city. We crossed the bay and drove across the bridge, and as we passed the exit

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

sector is Uber, a John Doerr–backed company that also has received a quarter-billion-dollar investment from Google Ventures. Founded in late 2009 by Travis Kalanick, by the summer of 2014 Uber was operating in 130 cities around the world, employing around 1,000 people, and, in a June 2014 investment

…

feedback loop of Sergey Brin’s “big circle” is coming to encircle more and more of society. And then there’s Google’s interest in Travis Kalanick’s Uber—another play that may turn out to be a massive job killer. In 2013, Google Ventures invested $258 million in Uber, the largest

…

Chapman University geographer Joel Kotkin has broken down what he calls this “new feudalism” into different classes, including “oligarch” billionaires like Thiel and Uber’s Travis Kalanick, the “clerisy” of media commentators like Kevin Kelly, the “new serfs” of the working poor and the unemployed, and the “yeomanry” of the old “private

…

content to give their own stuff away for nothing, Napster gave away everybody else’s as well. Along with other peer-to-peer networks like Travis Kalanick’s Scour and later pirate businesses such as Megaupload, Rapidshare, and Pirate Bay, Napster created a networked kleptocracy, masquerading as the “sharing economy,” in which

…

’s self-congratulatory tenor, failure as a lesson in humility. But the award for the most successful and least humble of FailCon failures went to Travis Kalanick, the cofounder and CEO of the transportation network Uber, whose prematurely graying hair and hyperkinetic manner suggested a life of perpetual radical disruption. Both his

…

disrupters who, without our permission, are building the distributed capitalist architecture of the early twenty-first century. The market knows best, hard-core libertarians like Travis Kalanick insist. It solves all our problems. “Where lifestyle meets logistics” is how Uber all too innocently describes its mission to become the platform for the

…

Valley’s slick apologists of disruption. Real failure is a $36 billion industry that in a decade shrank to $16 billion because libertarian badasses like Travis Kalanick invented products that destroyed its core value. Real failure is the $12.5 billion in annual sales, the more than 71,000 jobs, and the

…

Europe since 2008.26 No wonder FailCon is coming to Spain. FailCon is coming everywhere soon. While it’s amusing to satirize libertarian clowns like Travis Kalanick with their pathetic boasts about $250 billion lawsuits and their adolescent Ayn Rand fetishes, this really is no laughing matter. Behind many of today’s

…

an unregulated, hyperefficient platform like Airbnb for buyers and sellers. Their answer is the distributed system of capitalism being built, unregulated cab by cab, by Travis Kalanick. Their answer is a “lean startup” like WhatsApp that employs fifty-five people and sells for $19 billion. Their answer is data factories that turn

…

networks hovered hopefully around the hotel, too—companies like Lyft, Sidecar, and the fleet of me-too mobile-ride-hailing startups trying to out-Uber Travis Kalanick’s $18 billion market leader. Some of the people scrambling for a living as networked drivers were themselves aspiring entrepreneurs with billion-dollar startup ideas

…

on a Muni bus.29 Perhaps old ladies take Muni, I would have explained, because they can afford the $0.75 senior’s fare, whereas Travis Kalanick’s Uber service, with its surge pricing, could cost them $94 for a two-mile ride. And then there’s what the San Francisco–based

…

many ways, repeating itself. Today’s digital upheaval represents what MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee call the “second industrial revolution.” “Badass” entrepreneurs like Travis Kalanick and Peter Thiel have much in common with the capitalist robber barons of the first industrial revolution. Internet monopolists like Google and Amazon increasingly resemble

…

like Google, Uber, and Facebook are, on the one hand, enabling the vast personal fortunes of twenty-first-century Internet plutocrats like Mark Zuckerberg and Travis Kalanick; and, on the other, wrecking the lives of a woman like Pam Wetherington, the nonunionized worker at Amazon’s Kentucky warehouse who was fired after

Gigged: The End of the Job and the Future of Work

by Sarah Kessler · 11 Jun 2018 · 246pp · 68,392 words

for weed. Uber itself hinted that it would take its business model far beyond transportation: “Uber is a cross between lifestyle and logistics,” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick told Bloomberg. “Lifestyle is gimme what I want and give it to me right now and logistics is physically delivering it to the person that

…

it would serve as a conduit for opportunities that had otherwise left his small town, and others like it, behind. CHAPTER 4 UBER FOR X Travis Kalanick joined his first startup more than ten years before co-founding Uber, dropping out of the University of California, Los Angeles, to work on a

…

press release along these lines, creating a powerful technology that “delivers turnkey entrepreneurship to drivers across the country and around the world.” Explained Uber CEO Travis Kalanick: “For the first time, I think in possibly history, work is flexible to life and not the other way around.”2 He later stretched the

…

. Even as Abe crusaded against the entrepreneurs who he believed had scammed him, he also obviously admired them. He had “researched the hell” out of Travis Kalanick and learned that Uber’s CEO had taken some risks, like joining an early Napster-like startup that was later sued for billions of dollars

…

harassment and misogyny at the company, which led to an internal investigation that ultimately resulted in the firing of 20 employees and the ousting of Travis Kalanick, who resigned amid a shareholder revolt. The company was so desperate to mitigate the impact of this news that on a steamy summer day in

…

less, according to the company’s official account), had grown within years into a global empire—an astounding feat. Uber’s cofounder and longtime CEO, Travis Kalanick, meanwhile, had an interesting story line of his own. Often portrayed as a belligerent frat boy, he seemed hell-bent on ruthlessly eliminating any obstacles

…

even pick up an occasional project on the weekend, if he got bored or just needed some beer money. This is why then–Uber CEO Travis Kalanick had called the gig economy a “safety net.” For Curtis, it really was. * * * Forming a cooperative version of Mechanical Turk started to look less feasible

…

reason Uber could be expensive is because you’re not just paying for the car—you’re paying for the other dude in the car,” Travis Kalanick said on stage at a conference in 2014. “When there’s no other dude in the car, the cost of taking an Uber anywhere becomes

…

Squawk Box. CNBC. Wednesday, April 27, 2016. Transcript available from: http://www.cnbc.com/2016/04/27/cnbc-exclusive-cnbc-excerpts-uber-co-founder-ceo-travis-kalanick-on-cnbcs-squawk-box-today.html. 3 Kokalitcheva, Kia. Uber’s CEO Calls His Company a Labor “Safety Net.” Fortune. June 24, 2016. http://fortune

…

. 15 Isaac, Mike. Uber’s C.E.O. Plays with Fire. New York Times. April 23, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/23/technology/travis-kalanick-pushes-uber-and-himself-to-the-precipice.html?_r=0. 16 Federal Trade Commission website. Uber Agrees to Pay $20 Million to Settle FTC Charges

…

as Uber Promises Change at the Top. The Guardian. June 17, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/17/uber-drivers-homeless-assault-travis-kalanick. 18 Manyika, James, Susan Lund, Jacques Bughin, Kelsey Robinson, Jan Mischke, and Deepa Mahajan. Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy. McKinsey Global Institute

…

as Uber Promises Change at the Top. The Guardian. June 17, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/17/uber-drivers-homeless-assault-travis-kalanick. 20 Salehi, Niloufar, Lilly Irani, Michael S. Bernstein, Ali Alkhatib, Eva Ogbe, Kristy Milland, and Clickhappier. We Are Dynamo: Overcoming Stalling and Friction in Collective

…

-and-work/what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages. 5 Lynley, Matthew. Travis Kalanick Says Uber Has 40 Million Monthly Users. TechCrunch. October 19, 2016. https://techcrunch.com/2016/10/19/travis-kalanick-says-uber-has-40-million-monthly-active-riders/. 6 Quoted in Dray, Philip. There Is Power

…

of Teamsters International Labour Office (United Nations) Irani, Lilly iStockphoto Janah, Leila janitorial industry JCPenney jobs, traditional definition of Juno (ride-hailing service) jury duty Kalanick, Travis Kasriel, Stephane Kath, Ryan Kelly Services (“Kelly Girls”) Kinder, Shane King, Martin Luther, Jr. Knight, Brandon Knox, Anthony Konsus (project outsourcing service) Koopman, John Krueger

…

Freedom (Facebook page) #Uberspotting UberX unions and valuation worker benefits worker earnings worker equity packages worker expenses Xchange Leasing See also Campbell, Harry; Husein, Mamdooh; Kalanick, Travis; Leadum, Mario “Uber for X” model “Uberization” of work UN International Labour Office unemployment unemployment benefits unicorns (high-valuation startups) Unionen (Swedish white-collar trade

Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley

by Jacob Silverman · 9 Oct 2025 · 312pp · 103,645 words

Billion Dollar Loser: The Epic Rise and Spectacular Fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork

by Reeves Wiedeman · 19 Oct 2020 · 303pp · 100,516 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World--And How to Make It Work for You

by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms · 2 Apr 2018 · 416pp · 100,130 words

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by Rana Foroohar · 5 Nov 2019 · 380pp · 109,724 words

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by Jeremias Prassl · 7 May 2018 · 491pp · 77,650 words

What's Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy

by Tom Slee · 18 Nov 2015 · 265pp · 69,310 words

Unleashed

by Anne Morriss and Frances Frei · 1 Jun 2020 · 394pp · 57,287 words

Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy

by Alexandrea J. Ravenelle · 12 Mar 2019 · 349pp · 98,309 words

The Seven Rules of Trust: A Blueprint for Building Things That Last

by Jimmy Wales · 28 Oct 2025 · 216pp · 60,419 words

Super Founders: What Data Reveals About Billion-Dollar Startups

by Ali Tamaseb · 14 Sep 2021 · 251pp · 80,831 words

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by Paris Marx · 4 Jul 2022 · 295pp · 81,861 words

Risk: A User's Guide

by Stanley McChrystal and Anna Butrico · 4 Oct 2021 · 489pp · 106,008 words

The Cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion

by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell · 19 Jul 2021 · 460pp · 130,820 words

How to Fix the Future: Staying Human in the Digital Age

by Andrew Keen · 1 Mar 2018 · 308pp · 85,880 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain

by James Bloodworth · 1 Mar 2018 · 256pp · 79,075 words

After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back

by Juliet Schor, William Attwood-Charles and Mehmet Cansoy · 15 Mar 2020 · 296pp · 83,254 words

Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech

by Sara Wachter-Boettcher · 9 Oct 2017 · 223pp · 60,909 words

Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World

by Clive Thompson · 26 Mar 2019 · 499pp · 144,278 words

The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations

by Daniel Yergin · 14 Sep 2020

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by Anthony M. Townsend · 15 Jun 2020 · 362pp · 97,288 words

Modern Monopolies: What It Takes to Dominate the 21st Century Economy

by Alex Moazed and Nicholas L. Johnson · 30 May 2016 · 324pp · 89,875 words

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by Alec Ross · 13 Sep 2021 · 363pp · 109,077 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

The Gig Economy: A Critical Introduction

by Jamie Woodcock and Mark Graham · 17 Jan 2020 · 207pp · 59,298 words

How to Build a Billion Dollar App: Discover the Secrets of the Most Successful Entrepreneurs of Our Time

by George Berkowski · 3 Sep 2014 · 468pp · 124,573 words

Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology From Capitalism

by Wendy Liu · 22 Mar 2020 · 223pp · 71,414 words

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

by Brian Merchant · 25 Sep 2023 · 524pp · 154,652 words

Lab Rats: How Silicon Valley Made Work Miserable for the Rest of Us

by Dan Lyons · 22 Oct 2018 · 252pp · 78,780 words

Life as a Passenger: How Driverless Cars Will Change the World

by David Kerrigan · 18 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 80,835 words

Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere

by Christian Wolmar · 18 Jan 2018

Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World

by Meredith Broussard · 19 Apr 2018 · 245pp · 83,272 words

Tech Titans of China: How China's Tech Sector Is Challenging the World by Innovating Faster, Working Harder, and Going Global

by Rebecca Fannin · 2 Sep 2019 · 269pp · 70,543 words

The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power

by Michael A. Cusumano, Annabelle Gawer and David B. Yoffie · 6 May 2019 · 328pp · 84,682 words

Internet for the People: The Fight for Our Digital Future

by Ben Tarnoff · 13 Jun 2022 · 234pp · 67,589 words

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy--And How to Make Them Work for You

by Sangeet Paul Choudary, Marshall W. van Alstyne and Geoffrey G. Parker · 27 Mar 2016 · 421pp · 110,406 words

The Network Imperative: How to Survive and Grow in the Age of Digital Business Models

by Barry Libert and Megan Beck · 6 Jun 2016 · 285pp · 58,517 words

Rich White Men: What It Takes to Uproot the Old Boys' Club and Transform America

by Garrett Neiman · 19 Jun 2023 · 386pp · 112,064 words

The Industries of the Future

by Alec Ross · 2 Feb 2016 · 364pp · 99,897 words

Hype: How Scammers, Grifters, and Con Artists Are Taking Over the Internet―and Why We're Following

by Gabrielle Bluestone · 5 Apr 2021 · 329pp · 100,162 words

Silicon City: San Francisco in the Long Shadow of the Valley

by Cary McClelland · 8 Oct 2018 · 225pp · 70,241 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

Blood and Oil: Mohammed Bin Salman's Ruthless Quest for Global Power

by Bradley Hope and Justin Scheck · 14 Sep 2020 · 339pp · 103,546 words

Nothing but Net: 10 Timeless Stock-Picking Lessons From One of Wall Street’s Top Tech Analysts

by Mark Mahaney · 9 Nov 2021 · 311pp · 90,172 words

The Driver in the Driverless Car: How Our Technology Choices Will Create the Future

by Vivek Wadhwa and Alex Salkever · 2 Apr 2017 · 181pp · 52,147 words

Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It

by Scott Kupor · 3 Jun 2019 · 340pp · 100,151 words

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by Thomas W. Malone · 14 May 2018 · 344pp · 104,077 words

This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World

by Yancey Strickler · 29 Oct 2019 · 254pp · 61,387 words

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

by Anand Giridharadas · 27 Aug 2018 · 296pp · 98,018 words

Who Needs the Fed?: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America's Central Bank

by John Tamny · 30 Apr 2016 · 268pp · 74,724 words

Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It's Doing to Us

by Will Storr · 14 Jun 2017 · 431pp · 129,071 words

Bullshit Jobs: A Theory

by David Graeber · 14 May 2018 · 385pp · 123,168 words

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter

by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac · 17 Sep 2024

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?

by Bill McKibben · 15 Apr 2019

Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House

by Michael Wolff · 5 Jan 2018 · 394pp · 112,770 words

The Smartphone Society

by Nicole Aschoff

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou · 15 Feb 2015 · 400pp · 88,647 words

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power

by Max Chafkin · 14 Sep 2021 · 524pp · 130,909 words

No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram

by Sarah Frier · 13 Apr 2020 · 484pp · 114,613 words

Bezonomics: How Amazon Is Changing Our Lives and What the World's Best Companies Are Learning From It

by Brian Dumaine · 11 May 2020 · 411pp · 98,128 words

The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything

by Paul Vigna and Michael J. Casey · 27 Feb 2018 · 348pp · 97,277 words

Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?

by Thomas Frank · 15 Mar 2016 · 316pp · 87,486 words

Apple in China: The Capture of the World's Greatest Company

by Patrick McGee · 13 May 2025 · 377pp · 138,306 words

Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies

by Reid Hoffman and Chris Yeh · 14 Apr 2018 · 286pp · 87,401 words

Masters of Scale: Surprising Truths From the World's Most Successful Entrepreneurs

by Reid Hoffman, June Cohen and Deron Triff · 14 Oct 2021 · 309pp · 96,168 words

The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again

by Robert D. Putnam · 12 Oct 2020 · 678pp · 160,676 words

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by Guy Standing · 13 Jul 2016 · 443pp · 98,113 words

The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter

by David Sax · 8 Nov 2016 · 360pp · 101,038 words

The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets

by Thomas Philippon · 29 Oct 2019 · 401pp · 109,892 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

Extreme Economies: Survival, Failure, Future – Lessons From the World’s Limits