Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work

by

Alex Rosenblat

Published 22 Oct 2018

It’s no wonder that any number of Uber stakeholders might feel uneasy in their alliances with the company. After Uber and Lyft left Austin in 2016, I flew there to find out how drivers felt about being left behind. As I reported for Motherboard while conducting some of my fieldwork in spring 2016,33 Karl, a former Uber and Lyft driver, said, “They claim that it was because the background checks . . . would take too long and so on, but there is a time frame from now to February 2017 for that, so they had a lot of time to do all the background checks.” He signed up to work for GetMe, a local ridehail start-up, so he could keep working. “They [Uber and Lyft] didn’t need to shut down and leave the city like they did.”

…

Researchers found that users were active for 56 percent of the time on labor-intensive online platforms like Uber (as opposed to asset-intensive platforms, like Airbnb), and their reliance on it as a secondary source of income did not change over time.22 This could be because independent workers use their income to cover short-term expenses or to transition to other careers, as Hall and Krueger have argued regarding the high turnover of Uber drivers.23 One insight from my research may offer another explanation: some drivers hesitate to commit full time because they consider it a risky proposition, even if they earn more as drivers than they do working at their other jobs.24 And for some, gig work is a way to smooth over income volatility and unexpected expenses or gaps between jobs. Uber and Lyft send jobs to drivers who log in to work, and drivers are paid on time—weekly or occasionally through instant pay—which is no small thing. As a side gig, it can be used as an additive to, rather than a substitute for, other employment.25 Drivers Who Value Flexibility One of the promises of the gig economy is that workers have more flexibility to work when and as much as they want. That’s why many people start driving to earn extra income outside of their day jobs.26 Drivers for Uber and Lyft cite the flexibility—the freedom to take breaks when they want, pause to run errands, or go home and take a nap in the middle of the day—as one of the most important benefits of this job.

…

For Jin Deng, who formerly worked as a food delivery driver for a restaurant in New Jersey, driving for Uber and Lyft in New York City is a step up, although he’s quick to note that he drives because he didn’t go to school here and doesn’t have enough education to get a better job. Jin Deng was robbed twice in his last job, once with pepper spray that stung his eyes. As we talk, he reaches for the pocket on his cargo shorts, indicating that the thieves missed his wallet when they grabbed his bag of food and the cash he carried to make change for food deliveries. Now he’s driving a large Suburban for Uber and Lyft in New York City, and he finds that the cashless exchange of payments facilitated by the apps gives a huge boost to his perceived sense of safety on the job.

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by

Tim O'Reilly

Published 9 Oct 2017

In the long run, Uber and Lyft are not competing with taxicab companies, but with car ownership. After all, if you can summon a car and driver at low cost via the touch of a button on your phone, why should you bother owning one at all, especially if you live in the city? Uber and Lyft do for car ownership what music services like Spotify did for music CDs, and Netflix and Amazon Prime did for DVDs. They are replacing ownership with access. “I tell people I live in LA like it’s New York. Uber and Lyft are my public transit station,” said one customer in Los Angeles. Uber and Lyft also replace ownership with access for the companies themselves.

…

Drivers provide their own cars, earning additional income from a resource they have already paid for that is often idle, or allowing them to help pay for a resource that they are then able to use in other parts of their lives. Meanwhile, Uber and Lyft avoid the capital expense of owning their own fleets of cars. Passengers Who Expect Transportation On Demand. Much as Michael Schrage outlined in Who Do You Want Your Customers to Become?, Uber and Lyft are asking their consumers to become the kind of people who expect a car to be available as easily as they had previously come to expect access to online content. They are asking them to redraw their map of how the world works. Uber and Lyft recognized early on that many young urban professionals had already given up on owning a car, but for their business to spread beyond major urban centers and wealthy demographics, they would need more people to accept this premise and make the switch.

…

Unlike the taxi industry, which creates an artificial scarcity by issuing a limited number of “medallions,” Uber and Lyft use market mechanisms to find the optimum number of drivers, with an algorithm that raises prices if there are not enough drivers on the road in a particular location or at a particular time. While customers initially complained, using market forces to balance the competing desires of buyers and sellers has helped Uber and Lyft to achieve an equilibrium of supply and demand in close to real time. There are other signals in addition to surge pricing that Uber and Lyft use to tell drivers that more (or fewer) of them are needed.

After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back

by

Juliet Schor

,

William Attwood-Charles

and

Mehmet Cansoy

Published 15 Mar 2020

And pooled services like UberPool and LyftLine barely made a difference: their additional miles are 2.6. City-specific estimates come to similar conclusions. A San Francisco study that looked at how things changed from 2010 (before Uber and Lyft) to 2016 found that VMT rose 13 percent, half of which is attributable to the platforms.32 By 2016, ride-hail vehicles accounted for 15 percent of all trips within the city. Even Uber and Lyft now admit they are increasing congestion. A 2019 report they funded found that while they are still a small proportion of total VMT (1 to 3 percent across six metropolitan regions), their impact can be as high as 8 percent (Boston) or 13 percent (San Francisco).33 These findings contrast with early claims.

…

By breaking the law, Uber and Lyft destroyed that viability, and we’re now seeing their drivers subjected to a similar race-to-the-bottom.27 And what the ideological high ground can’t accomplish, money can. The biggest platforms, again with Uber in the lead, have employed an army of lobbyists and public relations firms to fight even minor changes. In response to a modest proposed California law to fill the gap in insurance coverage when a driver has the app on but isn’t on a fare, Uber hired fourteen of the fifteen biggest Sacramento lobbying firms.28 In 2017 Uber and Lyft had more lobbyists than Amazon, Microsoft, and Walmart combined.29 Airbnb has also been active trying to stop laws that limit rental activity or mandate the collection of hotel and occupancy taxes.

…

Washington, DC: Kalmanowitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, Georgetown University. https://lwp.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/Uber-Workplace.pdf. White, Andy, and Dana Olsen. 2018. “Here’s Where Uber and Lyft Would Rank among the Decade’s Most Valuable VC-Backed IPOs.” Pitchbook: News and Analysis, October 16, 2018. https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/heres-where-uber-and-lyft-would-rank-among-the-decades-most-valuable-vc-backed-ipos. Whyte, William H. 1956. The Organization Man. New York: Simon and Schuster. Wilhelm, Alex. 2019. “Postmates Raises $225M More at $2.4B Valuation Despite Private IPO Filing.”

What's Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy

by

Tom Slee

Published 18 Nov 2015

Uber is ambitious: it has explored many variants on its driving services from carpooling to high-end luxury services, as well as delivery and logistics, but for now UberX makes up the bulk of its business. It makes sense to talk of Uber and Lyft in the same breath, despite their different images, because they have ended up offering essentially the same service. When, after a campaign by Peers and others, California became the first state to create a separate set of rules for what it called Transportation Network Companies (TNCs), Uber and Lyft were the main beneficiaries.21 The TNC framework has since been adopted by Colorado, as well as Seattle, Minneapolis, Austin, Houston, and Washington.

…

Racism manifests itself differently in different environments, and the better experience of black customers is an unintended side-effect of Uber’s system. Uber drivers are not told where to drive, so they may avoid what they consider as “sketchy” parts of town, and both Uber and Lyft have been accused of “redlining”: not providing services to poor and minority neighborhoods.68 Numerous comments on social media suggest that one of the appeals of Uber and Lyft to young and well-off early adopters was that the drivers matched their age, educational-level, and social background more than did taxi drivers. Instead of being driven by a middle-aged immigrant man who had 60 hours on the clock that week, you could be picked up by “a friend with a car,” more likely to be female, more likely to be well educated, and more likely to be white.69 As the companies have expanded, however, the driver population more closely matches taxi drivers and this opportunity to discriminate has faded.

…

But what comes out of this is that the real story is a long way from $90,000, even though that number is still out there (Guendelsberger refers to “that $90,000 a year figure that so many passengers asked about”). Uber drivers appear to take home about the same as a taxi driver once expenses are figured in, while Uber itself has stepped in and takes as much of the fare as do medallion holders. One of the complaints that taxi companies have against Uber and Lyft is that they are subject to different standards, and that the taxi standards are more onerous than those that the ridesharing companies have to follow. Uber maintains that its drivers are subject to a thorough screening process, but a series of assaults on the service has put this largely automated process under scrutiny.

Pattern Breakers: Why Some Start-Ups Change the Future

by

Mike Maples

and

Peter Ziebelman

Published 8 Jul 2024

As a result, they continue with business as usual, unaware that the power to create radical change is there for the taking. Some founders have the insight to see these powers and harness them to create radical change. The insight behind Uber and Lyft was that it is possible to apply the sharing economy to cars. Just as Airbnb had allowed people to share an extra room in their houses, ridesharing start-ups like Uber and Lyft proposed to let people share an extra seat in their cars. It was possible, in other words, to radically change how people traveled from one place to another through an app that harnessed the power of GPS-enabled smartphones together with people’s willingness to share their location.

…

The inflections underpinning Uber and Lyft were not just minor; they were transformative. Their insight to apply those powerful advances to ridesharing acted as a multiplier effect. When you intertwine potent technological advancements with groundbreaking insights about how to harness them, the outcome is often transformative products that redefine industries. Before the new, foundational capabilities, nobody could have created a ridesharing network in the sense we understand them today. However, once those inflections were accessible, the insight uncovered by Uber and Lyft allowed them to usher in a service distinct from anything preceding it.

…

They achieved this through a combination of pattern-breaking ideas that were radically different and pattern-breaking actions that persuaded the rest of the world to think, feel, and act differently. Pattern-breaking ideas offer something radically different from anything that’s come before. At first, these ideas can seem crazy. Why would anyone stay in a stranger’s home? Yet Airbnb proved they would. Why would someone catch a ride in a stranger’s car? Uber and Lyft, having dispatched tens of billions of passenger rides, answered that question. How could 140-character “tweets” ignite the most explosive media revolution of the last two decades? X/Twitter, with its simplicity, transformed the media and the public square. Despite the initial strangeness of these transformative companies, their very uniqueness gave them enormous strength.

Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy

by

Alexandrea J. Ravenelle

Published 12 Mar 2019

In Sarah’s experience, TaskRabbit’s algorithm highlights people with high acceptance rates or high availability. “They want you on call for free,” she said, before describing her schedule instability as “frustrating. . . . [Y]ou are always thinking, ‘Oh, in five months I am going to be [sleeping] on a bench somewhere.’” Baran, twenty-eight, is a college student at a local university who drives for Uber and Lyft. In New York, app-based drivers have the same insurance and licensing requirements as taxi drivers, a cost that usually runs several thousand dollars. To sidestep this considerable start-up expense and the associated annual costs, some drivers rent a licensed, insured, and Uber-approved car through local services or utilize Uber’s fleet-owner and driver matching service.

…

Although early sites such as couchsurfing.com and ShareSomeSugar.com didn’t charge fees, most current “sharing economy” sites do charge them. An Airbnb host isn’t so much “sharing” her home or “hosting guests” as she is renting her home out. TaskRabbit assistants and Kitchensurfing chefs aren’t “sharing” their services but being paid. Likewise, even though Uber and Lyft describe themselves as “ride-sharing,” charging for private vehicle transportation is simply a taxi or chauffer service by any other name. While Lyft (slogan: “Your friend with a car”) originally encouraged riders to “sit in the front seat like a friend, rather than in the backseat like a fare,” such “friendship” didn’t eliminate the need to pay the fare.12 The reinvention of terms isn’t limited to the companies themselves but can also carry over into descriptions of the services by researchers.

…

Approximately half of the Uber drivers I interviewed were immigrants. An equal number of drivers identified as white (21 percent) and black (21 percent), while 14 percent described themselves as Hispanic and one driver was racially mixed.85 In the same way that a high percentage of cab drivers in New York are male (estimates range from 90 to 97 percent), all Uber and Lyft participants were male. Their ages ranged from twenty-two to fifty-nine, with 60 percent falling between twenty and thirty-nine years of age; the average age was thirty-six. Of those who answered education questions, 50 percent had at least a bachelor’s degree. Two participants listed their educational level as “some college,” one individual was currently enrolled in a local college, one had an associate’s degree, and one had a GED.

The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism

by

Arun Sundararajan

Published 12 May 2016

I’m pretty close with some hotel executives; they don’t seem to be overly concerned.” Indeed, as Alison Griswold from Slate magazine documents, the hotel industry in 2014–15 enjoyed their highest-ever levels of occupancy and average daily room prices.29 The same is not true of Uber and Lyft’s impact on traditional taxicabs. The key difference is that, rather than being merely a differentiated service, Uber and Lyft also display higher quality across the board on most dimensions that customer value, except perhaps the ability to hail a car on the street. This does not negate the point I’m making—the increase in variety will increase consumption.

…

Slate, July 6, 2015. http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2015/07/airbnb_disrupting_hotels_it_hasn_t_happened_yet_and_both_are_thriving_what.html. 30. Jennifer Surane, “New York’s Taxi Medallion Business Is Hurting. Thanks to Uber and Lyft.” Skift, July 15, 2015. http://skift.com/2015/07/15/new-yorks-taxi-medallion-business-is-hurting-thanks-to-uber-and-lyft. 31. Josh Barro, “Taxi Mogul, Filing Bankruptcy, Sees Uber-Citibank Plot,” New York Times, July 22, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/23/upshot/taxi-mogul-filing-bankruptcy-sees-a-uber-citibank-plot.html?abt=0002&abg=1. 32. Andrey Fradkin, “Search Frictions and the Design of Online Marketplaces,” September 30, 2015. http://andreyfradkin.com/assets/SearchFrictions.pdf. 33.

…

Uber Technologies, Inc. et al https://dockets.justia.com/docket/california/candce/4:2013cv03826/269290. Judge Chen’s decision (filing #251) is available at https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/california/candce/3:2013cv03826/269290/251. 4. Quoted in Dan Levine and Edward Chan, “Uber and Lyft Fail to Convince Judges,” Business Insider, March 2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/uber-and-lyft-fail-to-convince-judges-their-employees-are-independent-contractors-2015-3#ixzz3UIFTYbVy. 5. I have heard Teran discuss this at two separate events in the second half of 2015: the TAP Conference in New York on October 1, and the White House Summit on Worker Voice, October 7.

The Upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb, and the Killer Companies of the New Silicon Valley Are Changing the World

by

Brad Stone

Published 30 Jan 2017

In 2013, Boston plaintiff lawyer Shannon Liss-Riordan brought such lawsuits against Uber and Lyft in the two states where she thought the law was most favorable, California and Massachusetts. She had previously brought similar, largely unsuccessful cases against FedEx and several yellow-cab companies. Uber’s claim that it was facilitating a whole new kind of internet-enabled, on-demand work bothered her. “The mere fact that there is flexibility does not mean that the people who are doing the jobs shouldn’t get benefits and the protections of employment,” she says. “That is the reason we have these laws.” Both Uber and Lyft tenaciously fought against the cases, arguing that the great majority of their drivers didn’t actually consider themselves full-time chauffeurs and wanted to remain independent and free to take other work.

…

Uber agreed to pay as much as $100 million to a group of tens of thousands of drivers and to institute new policies, such as giving drivers explanations if they violated company rules and got kicked off the app and creating an appeals process for those decisions. But Uber and Lyft drivers were going to remain contractors. “Drivers value their independence—the freedom to push a button rather than punch a clock, to use Uber and Lyft simultaneously, to drive most of the week or for just a few hours,” wrote Kalanick in a blog post titled “Growing and Growing Up” that announced the settlement. He conceded that the company hadn’t “always done a good job working with drivers,” but reiterated that Uber presented “a new way of working: it’s about people having the freedom to start and stop work when they want, at the push of a button.”

…

Eric Newcomer and Olivia Zaleski, “Inside Uber’s Auto-Lease Machine, Where Almost Anyone Can Get a Car,” Bloomberg.com, May 31, 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-31/inside-uber-s-auto-lease-machine-where-almost-anyone-can-get-a-car. 7. Ryan Lawler, “Uber Slashes UberX Fares in 16 Markets to Make It the Cheapest Car Service Available Anywhere,” TechCrunch, January 9, 2014, http://techcrunch.com/2014/01/09/big-uberx-price-cuts/. 8. Ellen Huet, “How Uber and Lyft Are Trying to Kill Each Other,” Forbes, May 30, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/ellenhuet/2014/05/30/how-uber-and-lyft-are-trying-to-kill-each-other/#4a7e6b063ba8. 9. Carolyn Tyler, “Mother of Girl Fatally Struck by Uber Driver Speaks Out,” ABC7 News, December 9, 2014, http://abc7news.com/business/mother-of-girl-fatally-struck-by-uber-driver-speaks-out/429535/. 10.

The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power

by

Michael A. Cusumano

,

Annabelle Gawer

and

David B. Yoffie

Published 6 May 2019

By mid-2015, Uber had expanded to 300 cities around the world and had signed up its one-millionth driver, including over 150,000 active UberX drivers in the United States, and claimed to cover 75 percent of the U.S. population.11 Lyft had expanded to 65 cities with 100,000 drivers, all in the United States, by March 2015.12 With Uber and Lyft in the market, competition for drivers and riders was fierce. Both Uber and Lyft aggressively recruited drivers, offering cash bonuses of up to $500 or even $1,000 for drivers who switched from another ride-sharing platform, including Sidecar. Current drivers also received bonuses by referring drivers from another platform. Riders received credits for their first ride and additional credits when they referred other riders. Uber and Lyft periodically cut fares to attract riders. Although the companies claimed that increased ridership would more than make up for the reduced fares in putting money in drivers’ pockets, they took additional steps to avoid alienating drivers when they cut fares.

…

The company anticipated that the majority of revenues going forward would come from deliveries of food, flowers, and even medical marijuana rather than rides, a tacit admission that it had lost its battle to compete with the larger and more well-known ride-hailing platforms Uber and Lyft.3 That pivot failed to pay off, and the company announced it would suspend operations entirely on December 31. The next month it announced that it had sold the bulk of its assets and licensed its intellectual property to General Motors, which was in the process of developing its own transportation service.4 Sidecar never became a household name. Its failure was nonetheless significant because Sidecar had pioneered the peer-to-peer ride-sharing model before Uber and Lyft transitioned their start-ups into the space. By 2015, ride-sharing platforms—where smartphone apps connected riders with nonprofessional drivers operating their personal vehicles—had become a pillar of the sharing, or gig, economy, despite the fact that such platforms had only existed for three years.

…

When Uber cut its fares by 20 percent in January 2014, for instance, it reduced its commission on each ride from 20 percent to 5 percent until April, when it raised its commission back to 20 percent on the new, lower fares. Lyft followed suit, dropping its fares by 20 percent in April 2014, and reducing its commission to zero. On and off again subsidies for drivers increased the number available on both Uber and Lyft. Uber and Lyft both lost money as they pursued aggressive growth strategies and incurred enormous costs just to find and replace drivers. For example, as we noted in Chapter 3, Uber in 2017 lost $4.5 billion despite gross booking revenues of $37 billion. Although Lyft and Uber were primarily targeting each other in their aggressive strategies, Sidecar was caught in the cross fire and attempted to match some of its rivals’ tactics to induce more drivers to use its platform.

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by

Anthony M. Townsend

Published 15 Jun 2020

Take San Francisco, for instance, ride-hail’s birthplace and the city where people have most eagerly embraced it. By 2016, one-quarter of all vehicle congestion citywide was blamed on Uber and Lyft’s fleets. Fully one-half of the increase in traffic since 2010 was attributed to the ride-hail giants. More alarming than the overall trend were the localized spikes. In the city’s downtown financial district, for instance, Uber and Lyft accounted for a whopping 73 percent of the increased traffic in recent years. Reprogramming mobility had eliminated a decade’s worth of painstaking work by transit agencies, cycling advocates, and walkability planners to reduce auto use.

…

As cyberpunk novelist William Gibson once famously said, “The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.” The first changes we notice will occur in taxis. Most market analysts agree that all taxis in the industrialized nations will be automated by 2030. In the US, that’s 300,000 vehicles. Add in all the Ubers and Lyfts and the total is closer to 1,000,000 in all. Swarming from our airports and resorts through our most beloved downtowns, driverless cabs could become the face of automation for a generation, and the gateway drug to driverless mobility for billions of passengers every year. The arrival of driverless cabs could radically change consumers’ perception of cars.

…

The scheme seemed too crazy to work—until it did. And with its decentralized approach to rebalancing, Bird’s scooter network expanded even more rapidly than dockless bike-share systems had the previous summer. There was a big problem though. Bird soon found itself with the same challenge confronting ridehail operators Uber and Lyft. Workers were taking home all the profits. Here’s where automation comes in. The Google gang’s facetious scenario incorrectly assumed that the killer app for self-driving bikes was hauling lazy people around. The shift to dockless revealed something altogether. Automation was the key to corralling thousands of wayward rides on the cheap.

Nothing but Net: 10 Timeless Stock-Picking Lessons From One of Wall Street’s Top Tech Analysts

by

Mark Mahaney

Published 9 Nov 2021

Although the Covid-19 crisis did have a materially negative impact on demand for the two leading US ridesharing services, Uber and Lyft shares were under pressure long before the pandemic because of the large losses both companies were running. In 2019, Lyft generated $2.6 billion in net income loss, while Uber generated $8.6 billion in net loss. These loss levels were practically unprecedented. And in the quarters post their IPOs, there was substantial uncertainty whether Uber and Lyft would ever be profitable. That uncertainty was exactly what Brown’s comments captured. It is striking that UBER then traded up almost 70% in 2020.

…

I tend to weigh four factors most heavily in coming up with the best comps for a profitless company: scale (companies with similar-sized revenue bases), growth (companies with similar revenue growth outlooks), gross margin, and long-term operating or EBITDA margin potential. Rarely are there perfect comps, but usually there are enough companies to come up with a reasonable range of multiples that can help determine whether a profitless company’s valuation is ballpark reasonable, at least based on comps. Uber and Lyft This brings us back to Uber and Lyft and the “fantasy valuation” that we talked about at the start of this lesson. Again, both these companies went public in 2019 in the wake of substantial losses. Neither company was expected to generate a material profit in the near future. The 10-year DCF I published in my UBER initiation report didn’t have EBITDA or free cash flow turning positive until 2023.

…

As a rule of thumb, a company with a single-digit percentage share of a large TAM might be an ideal candidate for tech investors to consider. TAMs can be expanded. By removing friction and by adding new use cases, TAMs can be made larger. That’s essentially what Uber and Lyft did over the years. By lowering prices, increasing the number of drivers on its platform, reducing wait times, and making payments and tipping seamless, Uber and Lyft expanded the use cases for and the appeal of ridesharing. There are also two specific steps that companies can take to expand their TAMs—expand into new geographic markets and generate new revenue streams. Sometimes TAMs are hard to ascertain, especially when a traditional industry is being disrupted, and creative new approaches are required.

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

In September 2019, the decision was codified into law when California’s state legislature passed Assembly Bill 5, which set a deadline of January 1, 2020, for employers to reclassify their workers—and the emphasis was placed on companies in the gig economy, including Uber and Lyft. January 1 came and went without gig workers’ status changing, but they kept pushing lawmakers to ensure the law was observed. In May 2020, California’s attorney general and the city attorneys for San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego took Uber and Lyft to court for misclassifying their workers, and the following month the PUC ruled that drivers for Uber and Lyft were employees, not contractors. On August 10, a judge ruled that the companies had ten days to reclassify their workers as employees, but at the last minute the ruling was delayed until after the election on November 3.

…

The medallions cost $250,000 and drivers had to scrape together a 5 percent deposit, but the city promised them it was a safe investment. Yet, just a few years after drivers had taken on those large debts, Uber and Lyft entered the market and the city did not hold up its end of the bargain. Not only did taxi drivers’ lives fall apart in the years following the swift transformation of their industry to serve the interests of multinational ride-hailing companies, but some felt there was no getting out of the hole they then found themselves in. A driver in Chicago told NBC News in 2018 that he had colleagues die of heart attacks and strokes after Uber and Lyft left them in dire financial straits. That same year, four taxi drivers, three livery drivers, and an Uber driver committed suicide in New York City.21 The most high-profile of those suicides was that of Douglas Schifter.

…

In Boston, it was estimated that 54 percent of the trips that users took on ride-hailing services would have been made by taking transit, cycling, or walking if the services had not been available, and 5 percent of trips would not have happened at all.12 Meanwhile, a larger survey that covered Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, DC similarly found that between 49 and 61 percent of trips on ride-hailing services pulled people from those more efficient transport modes or would not have happened if ride-hailing services had not been available. The researchers also found that people using Uber were very unlikely to get rid of their personal vehicles.13 This shows that Uber is not reducing congestion or vehicle ownership, and it is also unlikely to reduce transport emissions or to complement traditional public transit. All the Uber and Lyft vehicles that flooded North American streets also made transit services less reliable and less efficient. Buses get stuck in traffic more often and, naturally, riders then start to look for alternatives. In Toronto, less than half of ride-hailing users had a transit pass, compared to just over one-third in Boston,14 and a study of twenty-two US cities estimated that the entry of Uber or Lyft reduced the ridership of buses and heavy rail every year they operated.15 It should go without saying that taking people from transit and putting them in cars not only makes traffic worse, it also increases the environmental footprint of a trip.

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

by

Brian Merchant

Published 25 Sep 2023

I dove into the archives, interviewed historians, spent time with Luddite scholars—I even lodged with one, in an old weaver’s cottage—and tried to picture this world in the throes of change. To bring the past into dialogue with the present, I interviewed historians of automation and artificial intelligence, attended worker protests against Uber and Lyft, and stopped by then presidential candidate Andrew Yang’s campaign headquarters to hear him raise the specter of the robot jobs apocalypse. I found a ripping tale of unlikely heroes and antiheroes, of fearsome rebellion, of oath-bound secret societies and the spies sent to infiltrate them, of the fickle allegiances of celebrities like Lord Byron, and of the violent royal rage that would culminate in the largest domestic military occupation in Britain’s history.

…

“We’ve had some initial fights over autonomous vehicles already,” de Blasio said; companies that want to come onto the streets of New York that we would not allow for safety reasons alone, that might have a huge negative impact, employment-wise. But on just the for-hire vehicle sector, you know, Uber and Lyft—it’s not automation in some ways in the fullest sense, obviously, but simply a new technology that automated some functions—and had a massive dislocating impact on our transportation sector. South Korea is so far the only country to institute something akin to a robot tax. The nation eliminated incentives previously offered to companies investing in technology, but only for automation tech.

…

Bill Gates’s lawyer, John Warden, explained to listeners unversed in English history that the Luddites were a band of workers who smashed machines “to arrest the march of progress driven by science and technology.” In 2014, conservative commentators applied the Luddite label to the taxi lobby when it sought to slow the (regulation-skirting) rise of Uber and Lyft—the label was applied derisively and mockingly, and implied the efforts were doomed to fail. “I don’t know many people who still wear hand-sewn garments,” one columnist sneered.2 Part of the reason that so much derision is heaped on the Luddites is that it’s easy to look around today and see the outcomes of their lost battle.

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by

Jeremias Prassl

Published 7 May 2018

We return to a legal analysis of these terms in Chapter 5. 50. Julia Tomassetti, ‘Does Uber redefine the firm? The postindustrial corporation and advanced information technology’ (2016) 34(1) Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal 239, 293: Uber and Lyft sublimate their agency in the production of ride services into algo- rithms, programming, and technology management. The metaphor of the ‘platform’ transforms Uber and Lyft from subjects into spaces. It evokes a passive space to be inhabited by active agents—drivers and passengers. For example, Lyft argues that drivers’ ‘low ratings [are] given by passengers, not Lyft. Uber argued that passengers, and not Uber, controlled drivers’ work.

…

cc/VX4Q-77CT; Josh Dzieza, ‘The rating game: how Uber and its peers turned us into horrible bosses’, The Verge (28 October 2015), http://www.theverge. com/2015/10/28/9625968/rating-system-on-demand-economy-uber-olive- garden, archived at https://perma.cc/CVU4-GEV7; Benjamin Sachs, ‘Uber and Lyft: customer reviews and the right to control’, On Labor (20 May 2015), http://onlabor.org/2015/05/20/uber-and-lyft-customer-reviews-and-the- right-to-control/, archived at https://perma.cc/9TNM-Y95X 52. Josh Dzieza, ‘The rating game: how Uber and its peers turned us into horrible bosses’, The Verge (28 October 2015), http://www.theverge.com/2015/10/28/ 9625968/rating-system-on-demand-economy-uber-olive-garden, archived at https://perma.cc/CVU4-GEV7 53.

…

The former approach can be key to platforms’ rapid expansion, particularly in the transportation industry, in which many operators relied on a strategy of ‘asking forgiveness, not permission’. Details vary between jurisdictions and across different cities, but the fundamental question tends to be the same: should the same regulatory and licensing regimes apply to traditional transport operators and platforms such as Uber and Lyft? Historically, national and local regulators have imposed a large number of requirements on taxi companies, from licensing caps and price control, to * * * 36 Doublespeak driver background checks and general access conditions. Platforms argue that their operations are fundamentally different and thus should not be subject to the same requirements.

The Passenger

by

AA.VV.

Published 23 May 2022

An independent contractor must control their own labor and time, engage in similar work on a regular basis, and be providing a service outside the scope of the business they are contracting with. Gig-economy businesses such as Uber and Lyft lobbied to have their companies placed on the exemptions list but were denied. They weren’t alone in their disapproval; musicians and truck drivers also often fell between the cracks of typical employment classification, and they, too, sought special consideration lest their professions be adversely affected. But once refused inclusion in the exemption list, Uber and Lyft took a different stance altogether; they chose to disregard AB5 in its entirety and refused to reclassify gig workers as employees.

…

When he finally found it, he thought nothing of locating his New Helvetia, the future state capitol, in the embrace of not one river but two, the worst floodplain in all of California. The city of Sacramento, girdled by levees and erected on a twelve-foot (3.5-meter) bed of borrowed earth, its gilded statehouse stabbing at sun, could not have looked more fitting and imperiled 180 years later. Protests against Uber and Lyft at Uber’s headquarters in San Francisco. Ballot-Box Blues: The Indirect Road to Direct Democracy Direct democracy in California takes many forms, sometimes unexpected, and the results of the various ballot initiatives are not always foregone conclusions. Here we take a look at this essential democratic tool through two of the most controversial propositions of recent times.

…

But once refused inclusion in the exemption list, Uber and Lyft took a different stance altogether; they chose to disregard AB5 in its entirety and refused to reclassify gig workers as employees. In turn, the California attorney general sued the rideshare companies, and in the summer of 2020 the court ruled against Uber and Lyft and said that they were misclassifying gig workers as independent contractors. On 10 August 2020, the companies were given ten days to comply with AB5, but they threatened to shut down their rideshare services across the state. Through the app, users were sent an ominous message declaring services to be terminated across California on 20 August. On that date, the companies announced they were granted an extension by the court until 4 November.

Wild Ride: Inside Uber's Quest for World Domination

by

Adam Lashinsky

Published 31 Mar 2017

He says he earned about $1.50 per mile when he started out. That rate dropped to $1.20 and then a mere 90 cents, which explains his surge-only practice. On the other hand, Snover deftly learned how to take advantage of the generous incentives Uber and Lyft have paid to build up their driver rolls. He said he got $500 for signing up his wife to drive for each service. Together with minimum-level bonuses, the two banked $1,400 from Uber and Lyft just for starting to drive. Many Uber drivers also follow a predictable path from excitement to disappointment to resignation. Bineyam Tesfaye, a former cabbie in Washington, D.C., started driving for Uber in 2016 and was pleased to be earning up to $1,200 a week.

…

There is similar national data for driver’s licenses: The number ticked up by four million from 2014 to 2015, also according to census data. As well, the Pew Research Center reported in 2016 that while 51 percent of Americans had heard of the concept of ridesharing, just 15 percent had used a service like Uber and Lyft, and another 33 percent were unfamiliar with them altogether. Surveys suggest that Uber has had a meaningful impact on the life of young adults in urban areas but hasn’t yet triggered the kind of societal change it frequently trumpets. Uber does represent a new opportunity for drivers, if a challenging one.

…

In a blog post addressed to the “Uber-Faithful,” the company warned that proposed rule changes would make Uber’s pricing model illegal (which it compared to telling hotels they couldn’t charge by the night), ban Uber drivers from downtown Denver (“TAXI protectionism at its finest”), and make it illegal to partner with limousine companies. Uber urged its supporters to contact the state’s governor, John Hickenlooper, directly. In 2014, Hickenlooper signed a bill that lightly regulated Uber and its competitors, effectively legalizing the service. These battles played out almost everywhere Uber—and Lyft, often behind it—went. In early 2014, for example, the news site BuzzFeed counted seventeen active regulatory fights in various U.S. cities, counties, and states. These included a protracted battle in New York City, where one of the bones of contention was the city’s demand that Uber share trip data with officials, and Orlando, where proposed rules attempted to force Uber and similar companies to charge 25 percent more than taxis.

Gigged: The End of the Job and the Future of Work

by

Sarah Kessler

Published 11 Jun 2018

“In the new world of on-demand everything,” wrote one critic of this system, “you’re either pampered, isolated royalty—or you’re a 21st century servant.”1 The price of this affordable royalty treatment was still falling. Under pressure to grow as quickly as possible, startups often discounted their services to attract customers and undercut competitors. Uber and Lyft engaged in a “price war” that would eventually in some cities make their services cheaper than public transportation. These price reductions were partially subsidized by venture capitalists who had invested billions in the companies, but they were also funded by cuts to drivers’ pay. As Uber and Lyft became prevalent, the startups continued to cut fares and increase commissions, claiming a higher percentage of each fare as a fee. Customers, if they were aware of any impact that this had on drivers, didn’t seem to care.

…

“The much-touted virtues of flexibility, independence and creativity offered by gig work might be true for some workers under some conditions,” she said in a speech at an annual conference for the New America Foundation in Washington, “but for many, the gig economy is simply the next step in a losing effort to build some economic security in a world where all the benefits are floating to the top 10 percent.”21 The speech wasn’t exactly about the gig economy: “The problems facing gig workers are much like the problems facing millions of other workers,” Warren noted. But the headlines were definitely about the gig economy: “Elizabeth Warren Takes on Uber, Lyft and the ‘Gig Economy’”;22 “Elizabeth Warren Calls for Increased Regulations on Uber, Lyft, and the ‘Gig Economy’”;23 “Elizabeth Warren Slams Uber and Lyft.”24 In her speech, Warren had acknowledged that talking about TaskRabbit, Uber, and Lyft was “very hip.” It seemed she was right. Sometimes politicians and labor leaders didn’t even need to frame their positions within the context of the gig economy to have them interpreted that way. The media did it for them. When the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division published new guidance on worker classification in July 2015 (which would later be rescinded by the Trump administration), it did not mention Uber.

…

“We’ve never had a layoff,” the application site bragged. It was a decent job, but not one that was likely to survive automation. In some industries, the gig economy serves as a stop-gap technology, with companies employing people in the cheapest way possible until, eventually, it becomes cheaper to buy a machine. This is the case with Uber and Lyft, for instance. “The reason Uber could be expensive is because you’re not just paying for the car—you’re paying for the other dude in the car,” Travis Kalanick said on stage at a conference in 2014. “When there’s no other dude in the car, the cost of taking an Uber anywhere becomes cheaper than owning a vehicle.”2 Uber started picking up passengers in its first tests of self-driving cars in Pittsburgh in 2016.

New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World--And How to Make It Work for You

by

Jeremy Heimans

and

Henry Timms

Published 2 Apr 2018

Think of Twitter, which has been challenged because its super-participants (the influential super-users who dominate the platform) love its quirky functionality and culture, while those same qualities prevent growth among the vastly larger market of everyday participants, many of whom find Twitter noisy, confusing, and nasty. To dig into these dynamics a bit more deeply, let’s turn to the sharply contrasting ways that Uber and Lyft—two ridesharing apps with very similar businesses—are managing their new power communities. This juxtaposition tells us a lot about the connections among platforms, super-participants, and participants, and the factors that can bring them closer together, or drive them farther apart. ORGANIZING PICKETS VS. ORGANIZING PICNICS: THE BIG DIFFERENCE BETWEEN UBER AND LYFT The battle of Uber vs. Lyft has become the Coke vs. Pepsi of the new power economy. The two companies are both chasing the same drivers and riders.

…

They live in fierce and unfriendly competition, with Uber well ahead, having scaled much faster and expanded globally, leading to a valuation over ten times that of Lyft, but with Lyft posing a real threat in some of Uber’s biggest markets. The functionality of the two platforms is very similar. An Uber user feels thoroughly at home with the Lyft app and vice versa. But from the beginning, Uber and Lyft have positioned themselves very differently. Uber launched as “everyone’s private driver”—the pitch being that you, too, could slink into the back of a badass shiny black ride. Lyft came to life as “your friend with a car,” with a giant pink mustache amiably perched on the grille, riders hopping in the front seat and fist-bumping the driver a hello.

…

They created structures to get all three corners of the new power triangle allied in facing the challenge, with incentives for their drivers and the hashtag campaign for their passengers. Inductions and inducements “Rideshare Guy” Harry Campbell has been a driver for both companies. He explained to us that the stark difference in culture between Uber and Lyft plays out broadly in how they manage their drivers. For both firms, the ease of signing up as a driver is touted throughout their networks. (Compare the promise of “signing up takes less than four minutes” with the two years of deep study of the “knowledge” needed to become a London taxi driver—a powerful reminder of how our notions of expertise are changing in a new power world.)

Tech Titans of China: How China's Tech Sector Is Challenging the World by Innovating Faster, Working Harder, and Going Global

by

Rebecca Fannin

Published 2 Sep 2019

The most acquisitive by far is Tencent with 146 deals and $25.7 billion of investment, followed by Alibaba with 51 deals and its part-owned Alipay with 2 deals and $3.7 billion in volume, and Baidu with 28 tech investments at $4.1 billion.2 China’s dragons have teamed up with top-tier US-based venture firms Mayfield and New Enterprise Associates, private equity firms General Atlantic and Carlyle Group, corporate strategic investors General Motors and Warner Brothers, and Japan’s acquisitive SoftBank. They’ve invested in US ride-hailing leaders Uber and Lyft, electric-carmaker Tesla, and augmented reality innovator Magic Leap. These Chinese tech titans have taken their cues directly from Silicon Valley venture capitalists. They’ve scoured the Valley for promising startups and based their operations not far from Menlo Park’s storied Sand Hill Road firms that backed winners Google, Facebook, and eBay.

…

The appeal of ride hailing is the ability to tap on a mobile screen and secure a driver to take you where you want to go for less than a taxi fare, then step out of the car without dealing with cash. Didi has proven to be an innovator in ride hailing, a segment that has gotten a lot of attention with the recent public offerings of Uber and Lyft in the United States. One Didi service sends a driver to your personal car when you’ve had too much to drink. Another is an SOS feature to activate in case of a hazard or emergency. Today, in China’s congested cities, it’s no longer a status symbol to own a car. It’s a pain because of traffic jams, parking hassles, and financial costs.

…

Not sure if Uber will be trying this out in the United States. The Traffic Brain In some other realms, Didi sees a brighter horizon. The company is focusing on expanding outside China, investing more in AI systems and autonomous driving, conducting research at a Silicon Valley lab, and planning an electric vehicle network of 10 million by 2028. Like Uber and Lyft experimenting with new self-driving thrills, Didi is testing self-driving vehicles in four cities in China and the United States and has a grand plan to launch driver-less taxis soon. Robo taxis are already a reality in China—and the United States. The self-driving highway is looking more and more jammed.

The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy

by

Nick Romeo

Published 15 Jan 2024

Gould IV, “Will Voters Side with the Continued Exploitation of Gig Workers?,” Hill, October 15, 2020, https://thehill.com/opinion/finance/521146-will-voters-side-with-the-continued-exploitation-of-gig-workers/. 5. Ken Jacobs and Michael Reich, “What Would Uber and Lyft Owe to the State Unemployment Insurance Fund?,” (data brief), CWED, IRLE, UC Berkeley Labor Center, May 2020, https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/pdf/2020/What-would-Uber-and-Lyft-owe-to-the-State-Unemployment-Insurance-Fund.pdf. 6. Julian Bingley, “Exploited Gig Workers Need Industry Reform Claims New Flinders University Study,” ZDNET, May 30, 2022, https://www.zdnet.com/article/exploited-gig-workers-need-industry-reform-claims-new-flinders-university-study/. 7.

…

Gilbert, of the forest brawls, is a restaurant manager. 5 Disrupting the Disruptors Gig Work as a Public Utility One October morning in 2020, a week before California voters passed Proposition 22, denying gig workers the legal status of employees and associated benefits such as paid sick time and unemployment insurance, an Oakland nonprofit hosted a talk entitled “Beyond the Gig Economy.” Companies such as Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash had spent over $200 million campaigning for Proposition 22, outspending their opponents by a factor of ten to one in the costliest ballot fight in the state’s history.1 For the companies, this was a good investment: the valuations of Uber and Lyft increased by $13 billion after the proposition passed.2 For their workers, it was a different story. A calculation by UC Berkeley researchers found that unpaid waiting time, underpayment of expenses, and unpaid payroll taxes made drivers’ guaranteed effective minimum wage after the measure passed $5.64 an hour.3 California gig workers could be penalized for declining jobs, for not delivering orders within a specific time frame, for missing shifts, regardless of the reason, or for not logging in with sufficient frequency.

…

A calculation by UC Berkeley researchers found that unpaid waiting time, underpayment of expenses, and unpaid payroll taxes made drivers’ guaranteed effective minimum wage after the measure passed $5.64 an hour.3 California gig workers could be penalized for declining jobs, for not delivering orders within a specific time frame, for missing shifts, regardless of the reason, or for not logging in with sufficient frequency. They lacked overtime, antidiscrimination protection, family leave, workers’ compensation, expense reimbursement, and other protections.4 The misclassification of workers also harmed the state budget: one study found that Uber and Lyft would have paid $413 million into the state unemployment insurance fund if workers had been classified as employees between 2014 and 2019.5 Gig workers face exploitation around the world. In Australia, an Uber Eats driver was fired for allegedly arriving ten minutes late to a delivery, after working ninety-six hours in one week.6 In Europe, 62 percent of gig workers in 2021 worried about how unfair feedback would affect their prospects for future work.7 Across America, 58 percent of full-time gig workers said that they would struggle to come up with $400 in an emergency.8 Responding to such issues, California’s state legislature had in 2019 reclassified some part-time and gig workers—including drivers for Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash—as employees.

Lonely Planet Pocket Reykjavík & Southwest Iceland

by

Lonely Planet

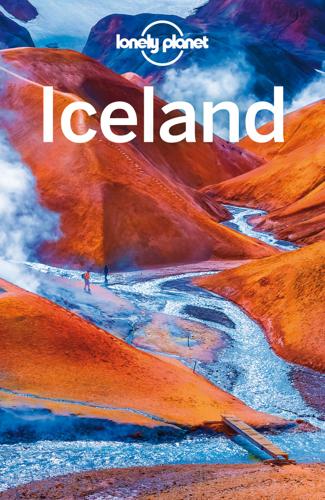

Airport Direct Slightly less-expensive bus to the city (3900kr to BSÍ bus terminal, 4990kr with hotel drop off). By Rental Car You can pick rentals up at the airport if exploring beyond Reykjavík (a car is unnecessary in the city centre). Pre-booking is best. By Taxi A taxi to the city (40 minutes) is relatively expensive at about 17,000kr. Uber and Lyft do not operate in Iceland. Other Points of Entry Reykjavík Domestic Airport This airport is in central Reykjavík, just 2km south of lake Tjörnin. Some flights to/from Greenland and the Faroe Islands fly here, as do sightseeing services and domestic flights. There’s a taxi rank at the airport.

…

Boats A weekly return ferry runs from northern Denmark to Seyðisfjörður in East Iceland, stopping at the Faroe Islands. Several cruise lines sail to Iceland from Canada, Europe and the UK. Getting Around Reykjavík is a small, walkable city. It's easy to get around without a car, and you can take the bus if you're heading across town. Uber and Lyft are not available, and there are no trains. For the countryside, nothing beats the freedom of a car, but tours can take you there, too. Walking The best way to get to know this compact city is on foot. Many of the city's top sights are within walking distance of one another. Bus Reykjavík has an extensive bus system operated by Strætó (bus.is) but it’s harder to get around by bus beyond Selfoss on the southern coast and Borgarnes to the north.

…

Parking Street parking in the city centre is limited and costs 600kr per hour in the Red/Pink zone 1 and 220kr per hour in the Blue, Green and Orange zones (zones 2, 3 and 4, respectively). The hours of operation vary (check reykjavik.is). Pay with coins, card (with PIN only) or Easypark and Parka apps. Parking outside the city centre is free. Vitatorg Car Park is a relatively central, covered lot. Taxis & Rideshares Uber and Lyft don't operate here. Book taxis online or via the Hreyfill app. Taxis are metered and can be pricey. Tipping is not expected. There are usually taxis outside bus stations, airports and bars on weekend nights. Iceland has a vibrant carpool scene. People submit routes they’re driving on samferda.net, and passengers can request rides and offer to split costs.

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by

Alec Ross

Published 13 Sep 2021

By March 25, 2019, Rideshare Drivers United: Alexia Fernández Campbell, “Thousands of Uber Drivers Are Striking in Los Angeles,” Vox, March 25, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2019/3/25/18280718/uber-lyft-drivers-strike-la-los-angeles; Bryce Covert, “‘It’s Not Right’: Why Uber and Lyft Drivers Went on Strike,” Vox, May 9, 2019, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/5/9/18538206/uber-lyft-strike-demands-ipo. On May 8, 2019, days before Uber: Covert, “Why Uber and Lyft Drivers Went on Strike,” https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/5/9/18538206/uber-lyft-strike-demands-ipo; Ben Chapman, “Uber Drivers in UK Cities Go on Strike in Protest over Pay and Workers’ Rights,” Independent, May 7, 2019, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/uber-drivers-strike-london-birmingham-glasgow-nottingham-pay-rights-a8898791.html.

…

You interact with the company only when something goes wrong with the app. For the most part, your marching orders—and your pay—are dictated by software. But just as technology platforms developed this new way to work, their contractors are pioneering new ways to organize. On August 22, 2017, more than one hundred Uber and Lyft drivers gathered outside Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) to protest for higher wages. In their effort to lower costs for passengers, the companies had reduced the pay rates for drivers. Between 2013 and 2017, rideshare drivers across the country had seen their monthly earnings fall more than 50 percent.

…

I’m going to ask you, what is your time worth?” Like many other grassroots initiatives, the protest was organized through a Facebook page. In the following months, the organizers of the event came together to form a new group called Rideshare Drivers United (RDU), with the goal of improving pay and work conditions for Uber and Lyft drivers. To advance the cause, the group needed to build its membership, and that required connecting with drivers who could go days without crossing paths with their fellow gig workers. In short, RDU needed to solve the proximity problem. To do so, the organizers turned to technology. If they were working through an app, why not strike through an app?

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

Published 7 Jan 2021

GDP also goes up when banks post financial profits, but it remains stagnant when digital innovations get introduced that make our lives easier. 40 “The Treasury's Living Standards Framework,” New Zealand Government, December 2019, https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-12/lsf-dashboard-update-dec19.pdf. 41 “New Zealand's Ardern Wins 2nd Term in Election Landslide,” Associated Press, October 2020, https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-new-zealand-mosque-attacks-auckland-elections-new-zealand-b1ab788954f23f948d8b6c3258c02634. 42 “Uber and Lyft Drivers Guild Wins Historic Pay Rules,” Independent Drivers Guild, December 2018, https://drivingguild.org/uber-and-lyft-drivers-guild-wins-historic-pay-rules/. 43 I'm a New York City Uber Driver. The Pandemic Shows That My Industry Needs Fundamental Change or Drivers Will Never Recover,” Aziz Bah, Business Insider, July 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/uber-lyft-drivers-covid-19-pandemic-virus-economy-right-bargain-2020-7?

…

Those who work for platforms or companies must have a say in the way these companies operate, how they treat their workers, and what responsibility they take toward society. There have been real-life experiments to assemble these stakeholders, such as when Rideshare Drivers United, a Californian advocacy group for drivers of Uber and Lyft, called for a global strike in May 2019, ahead of Uber's planned IPO. They encouraged drivers to shut off their mobile apps to make their case for more pay and better protections.15 But despite attracting a lot of media and political attention16 and leading to a one-off financial settlement for some drivers ahead of the IPO,17 the strike mostly revealed how hard it will be to replicate the influence taxi unions once had, as the structural demands of the drivers were not met.

…

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, April 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/e00099f0-3c19-11e8-b9f9-de94fa33a81e. 15 “The Worldwide Uber Strike Is a Key Test for the Gig Economy,” Alexia Fernandez Campbell, Vox, May 219, https://www.vox.com/2019/5/8/18535367/uber-drivers-strike-2019-cities. 16 “Uber Pre IPO, 8th May, 2019 Global Strike Results,” RideShare Drivers United, May 2019, https://ridesharedriversunited.com/uber-pre-ipo-8th-may-2019-global-strike-results/. 17 “Worker or Independent Contractor? Uber Settles Driver Claims Before Disappointing IPO,” Forbes, May 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2019/05/13/worker-or-independent-contractor-uber-settles-driver-claims-before-disappointing-ipo/#7a157b93f39f. 18 “Uber and Lyft Drivers in California Will Remain Contractors”, Kate Conger, The New York Times, November 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/04/technology/california-uber-lyft-prop-22.html. 19 “Are Political Parties in Trouble?” Patrick Liddiard, Wilson Center, December 2018, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/happ_liddiard_are_political_parties_in_trouble_december_2018.pdf. 20 “A Deep Dive into Voter Turnout in Latin America,” Holly Sunderland, Americas Society / Council of the Americas, June 2018, https://www.as-coa.org/articles/chart-deep-dive-voter-turnout-latin-america. 21 “Historical Reported Voting Rates, Table A.1,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/voting-and-registration/voting-historical-time-series.html. 22 “How to Correctly Understand the General Requirements of Recruiting Party Members?”

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

and

Peter Vanham

Published 27 Jan 2021

GDP also goes up when banks post financial profits, but it remains stagnant when digital innovations get introduced that make our lives easier. 40 “The Treasury's Living Standards Framework,” New Zealand Government, December 2019, https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-12/lsf-dashboard-update-dec19.pdf. 41 “New Zealand's Ardern Wins 2nd Term in Election Landslide,” Associated Press, October 2020, https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-new-zealand-mosque-attacks-auckland-elections-new-zealand-b1ab788954f23f948d8b6c3258c02634. 42 “Uber and Lyft Drivers Guild Wins Historic Pay Rules,” Independent Drivers Guild, December 2018, https://drivingguild.org/uber-and-lyft-drivers-guild-wins-historic-pay-rules/. 43 I'm a New York City Uber Driver. The Pandemic Shows That My Industry Needs Fundamental Change or Drivers Will Never Recover,” Aziz Bah, Business Insider, July 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/uber-lyft-drivers-covid-19-pandemic-virus-economy-right-bargain-2020-7?

…

Those who work for platforms or companies must have a say in the way these companies operate, how they treat their workers, and what responsibility they take toward society. There have been real-life experiments to assemble these stakeholders, such as when Rideshare Drivers United, a Californian advocacy group for drivers of Uber and Lyft, called for a global strike in May 2019, ahead of Uber's planned IPO. They encouraged drivers to shut off their mobile apps to make their case for more pay and better protections.15 But despite attracting a lot of media and political attention16 and leading to a one-off financial settlement for some drivers ahead of the IPO,17 the strike mostly revealed how hard it will be to replicate the influence taxi unions once had, as the structural demands of the drivers were not met.

…

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, April 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/e00099f0-3c19-11e8-b9f9-de94fa33a81e. 15 “The Worldwide Uber Strike Is a Key Test for the Gig Economy,” Alexia Fernandez Campbell, Vox, May 219, https://www.vox.com/2019/5/8/18535367/uber-drivers-strike-2019-cities. 16 “Uber Pre IPO, 8th May, 2019 Global Strike Results,” RideShare Drivers United, May 2019, https://ridesharedriversunited.com/uber-pre-ipo-8th-may-2019-global-strike-results/. 17 “Worker or Independent Contractor? Uber Settles Driver Claims Before Disappointing IPO,” Forbes, May 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2019/05/13/worker-or-independent-contractor-uber-settles-driver-claims-before-disappointing-ipo/#7a157b93f39f. 18 “Uber and Lyft Drivers in California Will Remain Contractors”, Kate Conger, The New York Times, November 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/04/technology/california-uber-lyft-prop-22.html. 19 “Are Political Parties in Trouble?” Patrick Liddiard, Wilson Center, December 2018, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/happ_liddiard_are_political_parties_in_trouble_december_2018.pdf. 20 “A Deep Dive into Voter Turnout in Latin America,” Holly Sunderland, Americas Society / Council of the Americas, June 2018, https://www.as-coa.org/articles/chart-deep-dive-voter-turnout-latin-america. 21 “Historical Reported Voting Rates, Table A.1,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/voting-and-registration/voting-historical-time-series.html. 22 “How to Correctly Understand the General Requirements of Recruiting Party Members?”

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy--And How to Make Them Work for You

by

Sangeet Paul Choudary

,

Marshall W. van Alstyne

and

Geoffrey G. Parker

Published 27 Mar 2016

BEYOND THE CORE INTERACTION As we’ve seen, platform design begins with the core interaction. But over time, successful platforms tend to scale by layering new interactions on top of the core interaction. In some cases, the gradual addition of new interactions is part of the long-term business plan that platform founders had in mind from the beginning. In early 2015, both Uber and Lyft began experimenting with a new ride-sharing service that complements their familiar call-a-taxi business model. The new services, known as UberPool and Lyft Line, allow two or more passengers traveling in the same direction to find one another and share a ride, thereby reducing their cost while increasing the revenues enjoyed by the driver.

…

The evolution of Uber, Lyft, and LinkedIn illustrates several of the ways that new interactions may be layered on top of the core interaction in a given platform: • By changing the value unit exchanged between existing users (as when LinkedIn shifted the basis of information exchange from user profiles to discussion posts) • By introducing a new category of users as either producers or consumers (as when LinkedIn invited recruiters and advertisers to join the platform as producers) • By allowing users to exchange new kinds of value units (as when Uber and Lyft made it possible for riders to share rides as well as arranging solo pickups) • By curating members of an existing user group to create a new category of users (as when LinkedIn designated certain participants as “thought leaders” and invited them to become producers of informational posts) Of course, not every new interaction is successful.

…

Multihoming occurs when users engage in similar types of interactions on more than one platform. A freelance professional who presents his credentials on two or more service marketing platforms, a music fan who downloads, stores, and shares tunes on more than one music site, and a driver who solicits rides through both Uber and Lyft all illustrate the phenomenon of multihoming. Platform businesses seek to discourage multihoming, since it facilitates switching—when a user abandons one platform in favor of another. Limiting multihoming is a cardinal competitive tactic for platforms. Here’s an example of how the effort to limit multihoming plays out in the new world of strategy.

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot

by

Rob Reich

,

Mehran Sahami

and

Jeremy M. Weinstein

Published 6 Sep 2021

A consortium of tech companies: Kari Paul and Julia Carrie Wong, “California Passes Prop 22 in a Major Victory for Uber and Lyft,” Guardian, November 4, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/nov/04/california-election-voters-prop-22-uber-lyft; Andrew J. Hawkins, “An Uber and Lyft Shutdown in California Looks Inevitable—Unless Voters Bail Them Out,” Verge, August 16, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/8/16/21370828/uber-lyft-california-shutdown-drivers-classify-ballot-prop-22. “I doubt whether”: Andrew J. Hawkins, “Uber and Lyft Had an Edge in the Prop 22 Fight: Their Apps,” Verge, November 4, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/11/4/21549760/uber-lyft-prop-22-win-vote-app-message-notifications.

…

Big tech is also spending millions to lobby European regulators to ward off efforts to limit digital advertising, contributing to what some call a “Washingtonization of Brussels.” Those lobbying efforts are unlikely to abate anytime soon, even as those companies come under greater antitrust scrutiny. One of the recent battlefronts in tech companies’ push to influence regulation comes from California’s effort to reclassify gig economy workers, such as Uber and Lyft drivers and delivery people for companies such as DoorDash, as employees rather than contractors of the firms they work for. In 2019, the California legislature passed Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5), with the aim of reclassifying thousands of independent contractors as employees, thereby guaranteeing them numerous benefits such as minimum wage, unemployment insurance, and sick leave.

…

The bill was a textbook case of government seeking to contain a negative externality created by a profit-seeking company. Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, an author of the bill, described her motivation: “As lawmakers, we will not in good conscience allow free-riding businesses to continue to pass their own business costs onto taxpayers and workers.” Providing such benefits would cost the likes of Uber and Lyft millions of dollars. Their response was swift. First, they tried to get an injunction against the new law, delaying its effective date. They were denied. Then they threatened to shut down their operations in the state. In the meantime, they worked on producing a ballot initiative, Proposition 22, that defined “app-based transportation (rideshare) and delivery drivers as independent contractors and [the adoption of] labor and wage policies specific to app-based drivers and companies,” effectively exempting them from the requirements of AB 5.

Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism

by

Robin Chase

Published 14 May 2015

But nothing prevents drivers from agreeing to drive for both companies or prospective passengers from having both apps on their smartphones. It is my experience with Zipcar and its competitors that customers choose based on a combination of convenience (the technology), price, and proximity. Both Uber and Lyft have business models and apps that appear to work; can the market sustain both? Buying (bribing) users too early in a company’s life cycle will just eat up a lot of money and won’t produce anything lasting. Doing so later is indeed possible, but it can be a very risky strategy depending on a company’s ability to defend that lead.

…

Right now, the Internet and GPS are wholly open platforms. It is this openness that has made for the infinite variation in applications. But some Inc platforms don’t want a lot of variation or creativity or innovation, and so they constrain the types of participation possible. Prosper wants to make loans to creditworthy borrowers. Uber and Lyft want safe drivers with clean cars. Twitter, on the other hand, doesn’t much care what you do with those 140 characters. The French precursor to the Internet was called Minitel and was widely used. It didn’t share these key characteristics. You needed a license to publish on it, and it was in every way a corporate and government walled garden.

…

In IT governance, this is the point at which the enterprise (the government, the business, the institution) competes against mission delivery (its own goals). As I looked at the graph, it became evident: having some rules (some structure) encourages me to participate, but having too many rules (too much structure) discourages me. Taxi regulations are full of outdated rules; hence the success of Uber and Lyft. Washington, D.C.’s Taxicab Commission chairman, Ron Linton, said that “Uber’s service is illegal because its drivers do not give passengers a receipt as they exit.”11 That’s true only if you define a receipt as a piece of paper. Everyone who uses these services pays by credit card from a preestablished online account and receives an email receipt in real time, pretty much as they close the door of the vehicle.

Street Smart: The Rise of Cities and the Fall of Cars

by

Samuel I. Schwartz

Published 17 Aug 2015

You don’t have to spend ten years learning the commuting ropes to know whether the train or bus you’re on is an express or a local, or even when it’s going to show up. You just need a smartphone. Smartphones are also all that’s needed to take advantage of other revolutionary new transportation options: ridesharing services like Via, car-sharing like Zipcar, and—especially—dispatchable taxi services like Uber and Lyft.c However, these and other cool new businesses didn’t create Millennial distaste for driving. They just exploited it. The question remains: why do Millennials find the automobile so much less desirable than their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents did? Woodbridge, Virginia, is a small suburb about twenty miles south of Washington, DC.

…

However, even these aren’t the biggest concerns. If the goal is to improve mobility for city dwellers—to replace automobile dependency with active and multimodal transportation options—then it’s difficult to see how ride-matching can ever be more than a small part of the solution. That’s because the defining characteristic of the Ubers and Lyfts of the world (and of their very vocal cheerleaders) is hostility to regulation. For decades now, regulation has been getting very bad press, and not just from conservative politicians and libertarian economists. Everyone has a list of silly bureaucratic rules that have long outlived their usefulness, and I’m no exception.

…

Beyond that point—that is, beyond the maximum carrying capacity of a particular city’s streets—the numbers won’t add up to more mobility, but less. This is an unavoidable fact of life. No matter how sophisticated the technology becomes, public streets will remain a public resource with finite capacity. When ride-matching services like Uber and Lyft treat city streets as a free good, they’re just repeating the same conceptual mistake that the original champions of motordom did during the 1920s—the argument that, while streetcars and trains were responsible for maintenance of “their” right-of-way, streets were free for everyone. Smart cities shouldn’t insist on stupid regulation.

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by

Nathan Schneider

Published 10 Sep 2018

Municipal and national politicians have come to Scholz and me, among others, in search of policies to consider and evidence they will work. The city of Barcelona has taken steps to enshrine platform cooperativism into its economic strategies. After Austin, Texas, required Uber and Lyft drivers to perform standard safety screenings, the companies pulled their services from the city in May 2015, and the city council aided in the formation of a new co-op taxi company and a nonprofit ride-sharing app; the replacements worked so well that Uber and Lyft paid millions of dollars in lobbying to force their way back before Austin became an example. Meanwhile, UK Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn issued a “Digital Democracy Manifesto” that included “platform cooperatives” among its eight planks.26 The challenge of such digital democracy goes beyond local tweaks.

…

The airport’s website had a notice about an impending contract bid for taxi companies, replacing the permits. This could reshape the city’s taxi business and make or break Green Taxi’s plan to cooperativize—and unionize, with CWA—one-third of the market. The airport’s new regime affected only taxi companies, but it had everything to do with the influx of apps. Unlike taxis, Uber and Lyft drivers faced no restrictions on their airport usage. They often drove nicer cars and spoke better English; they were more likely to be white. In December 2014, the app drivers made 10,822 trips through the airport, compared to 30,535 by taxis. A year later, for the first time, app-based airport trips exceeded the taxis, and they’d done so every month since.

…

Self-driving cars hadn’t come to the city’s roads yet, but Wall Street’s anticipation of them was fueling investment in the big apps, which put pressure on the taxi market and motivated so many drivers to set off on their own. The disruption was already happening, and Green Taxi had been born of it. In the beginning, before Uber and Lyft and even checkered taxicabs, there was sharing. At least that’s the story according to Dominik Wind, a German environmental activist with a genial smile and a penchant for conspiracy theories. Years ago, out of curiosity, Wind visited Samoa for half a year; he found that people shared tools, provisions, and sexual partners with their neighbors.

Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company's Future - and What to Do About It

by

Tien Tzuo

and

Gabe Weisert

Published 4 Jun 2018

The company may take a short-term profitability hit, but the goal is to gain long-term customer loyalty in a very young and turbulent market—and this customer loyalty is becoming more and more important as ridesharing becomes a commodity. Here in the Bay Area, the Uber and Lyft markets are really fluid. I’ll frequently toggle between the two services—lots of the cars even feature both logos in their windshields. There’s very little brand loyalty on my part. Now contrast that with my Amazon Prime experience. All due respect to other potential ecommerce vendors, but Amazon has my business, in no small part due to Amazon Prime—they hooked me with the free shipping, and now I’ve got music, movies, and all sorts of other services. I’m not going anywhere. Uber and Lyft are both vying for that same lock-in effect by offering discounted services around consistent consumption patterns—in other words, they’re going after my commute.

…

Online streaming was just around the corner (as many people have pointed out, Reed Hastings called it Netflix for a reason). Zipcar was also a really interesting new concept. It was initially seen as an hourly competitor to Hertz and Budget, but you could already see new ideas opening up around cars and transportation, which Uber and Lyft capitalized on later. And of course the iPhone had just come out—at the time it was more of a fun, plug-and-play app container, but there was the potential for geolocation, identity, messaging. As bandwidth increased and platform costs decreased, there was a logical progression going on toward on-demand, digitally enabled services.

…