We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters

description: a phrase critiquing perceived shortcomings in technological innovation, often attributed to entrepreneur Peter Thiel

21 results

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by

Jonathan Taplin

Published 17 Apr 2017

Gordon argues that the hype around the technology revolution is overdone and that digital services are less important to productivity than any one of the five great inventions that drove economic growth before 1970: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and telecommunications. Yes, it’s nice to have a phone and a computer in your pocket, but has it really changed the world the way the inventions of Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford did? Even Peter Thiel has remarked, “We wanted flying cars; instead we got 140 characters.” For Gordon, the future may be characterized by stagnant living standards, rising inequality, falling education levels, and an aging population. This chart, taken from Gordon’s book, puts the lie to notions about the computer revolution introducing radical productivity.

…

Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943). Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged (New York: Random House, 1957). Peter Thiel, “The Education of a Libertarian,” Cato Institute, April 2009, www.cato-unbound.org/2009/04/13/peter-thiel/education-libertarian. Hans Hermann-Hoppe, Democracy—The God That Failed (Newark: Transaction, 2001). Greg Satell, “Peter Thiel’s Four Rules for Creating a Great Business,” Forbes, October 3, 2014, www.forbes.com/sites/gregsatell/2014/10/03/peter-thiels-4-rules-for-creating-a-great-business/2/#2ea53ac12804. Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013).

…

We need to go ahead and get the Internet fixed or risk losing this engine of beauty.” People like Google CEO Larry Page, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, PayPal founder Peter Thiel, and Sean Parker of Napster and Facebook fame are among the richest men in the world, with ambitions so outsize that they are the stuff of fiction: Dave Eggers’s The Circle and Don DeLillo’s Zero K are populated with tech billionaires inventing technology that will enable people to live forever. But this scenario is happening in real life. Peter Thiel, Larry Page, and others are investing hundreds of millions of dollars in research to “end human aging” and to merge human consciousness into their all-powerful networks.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power

by

Max Chafkin

Published 14 Sep 2021

In July 2011, Thiel and his colleagues posted a five-thousand-word manifesto about slowing technological innovation under the title “What Happened to the Future?” Though written by a Founders Fund partner, Bruce Gibney, the ideas were the ones that Thiel had been working out for years. Its tagline compared the science fiction dreams of Thiel’s youth with ostensibly diminished aims of the world’s most successful tech companies: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” (This was a reference to Twitter, which had been heralded in the press as a potential Facebook-killer.) VCs, Thiel argued, had once funded ambitious semiconductor companies, drug developers, and hardware enterprises—iconic names like Intel, Genentech, Microsoft, and Apple.

…

the prominent tech scribe: Kara Swisher, “Kara Visits Founders Fund’s Peter Thiel,” AllThingsD, November 1, 2007, http://allthingsd.com/20071101/kara-visits-founders-funds-peter-thiel/. “hating open secrets”: Belinda Luscombe, “Gawker Founder Nick Denton on Peter Thiel, ‘Conflict and Trollery,’ and the Future of Media,” Time, June 22, 2016, https://time.com/4375643/gawker-nick-denton-peter-thiel/. a winking reference: Owen Thomas, “Peter Thiel’s Fabulous Fourth of July,” Valleywag, July 6, 2007, https://gawker.com/275650/peter-thiels-fabulous-fourth-of-july. failed to attract: Owen Thomas, “Peter Thiel’s College Tour,” Valleywag, October 6, 2017, https://gawker.com/308252/peter-thiels-college-tour.gawker.com “but Thiel’s taken”: Owen Thomas “Peter Thiel Crush Alert,” Valleywag, November 27, 2007.

…

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: PUBLIC INTELLECTUAL, PRIVATE REACTIONARY chant onto the stage: Adrienne Shih, “Protesters Break into Peter Thiel Speaker Event in Wheeler Hall,” Daily Californian, December 10, 2014, https://www.dailycal.org/2014/12/10/protestors-break-peter-thiel-speaker-event-wheeler-hall/. “spinning so much bullshit”: Kevin Montgomery, “Billionaire Peter Thiel Says Technology Isn’t Screwing Middle Class,” Valleywag, November 11, 2014, http://valleywag.gawker.com/billionaire-peter-thiel-says-technology-isnt-screwing-m-1657419404. “that’s somewhat unusual”: Ariana Eunjung Cha, “Peter Thiel’s Quest to Find the Key to Eternal Life,” The Washington Post, April 3, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-leadership/peter-thiels-life-goal-to-extend-our-time-on-this-earth/2015/04/03/b7a1779c-4814-11e4-891d-713f052086a0_story.html.

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

While it may appear that technological innovation continues to accelerate, this is merely an illusion, sustained by and mediated to a large extent through our smartphones. In reality, we have entered an age of deceleration and decline. As one noted tech investor summed it up, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” 11 The symptoms of technological, economic, and cultural stagnation can be detected everywhere. Some of the evidence is hard to quantify, but it can perhaps best be summarized by a simple thought experiment: Will children born today experience as much change as children born a century ago—a time when cars, electrical appliances, synthetic materials, and telephones were still in their infancy?

…

Mobile temples accompany intercontinental ballistic missiles, and nuclear-armed submarines have their portable churches.” Adamsky, Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy: Religion, Politics, and Strategy (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020), 1–2. 403 “Tech Investor Peter Thiel Speaks at The New York Economic Club,” CNBC, March 15, 2008, https://www.cnbc.com/video/2018/03/15/tech-investor-peter-thiel-speaks-at-the-new-york-economic-club.html. 404 Aristotle, Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 3.6.5.1281. 405 Cited in Stephen C. Jaeger, Enchantment: On Charisma and the Sublime in the Arts of the West (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 2.

…

Instead of boldly going where no one has gone before, our current spacefarers desire nothing more than to return from the darkness of space into the comfort zone of Earth—think of 1995’s Apollo 13, 2013’s Gravity, and 2015’s The Martian. Immediately after the Moon landing in 1969, Woodstock happened, and the Space Age gave way to the New Age. This striking observation, by the venture capitalist Peter Thiel, 64 represents the broader turn to subjective spirituality and interiority that took place in the 1970s and continues to this day. This shift coincided with a general movement toward escapism and a loss of ambition and hope for the future. The technological sublime that the Apollo mission represented was replaced by meditation, yoga, and individualistic forms of spirituality.

Why Startups Fail: A New Roadmap for Entrepreneurial Success

by

Tom Eisenmann

Published 29 Mar 2021

The good news is that the solution to the missing-systems problem is simply to solve the missing-manager problem: Bring on board senior specialists who have experience with scaling startups that faced challenges similar to those now at hand—and who can make smart choices about when and how to add management systems. Passing the “Able?” portion of the RAWI test hinges on having the right kind of specialist leaders at the helm. CHAPTER 9 Moonshots and Miracles We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters. —Peter Thiel, entrepreneur and investor We might not have flying cars, but Shai Agassi dreamt of a world where the roads were filled with electric ones. He founded the startup Better Place in 2007—before Tesla or Nissan had launched any all-electric models—with a bold vision: He would create a massive network of charging stations for electric vehicles.

…

“Startups can get by”: Thomas Eisenmann and Halah AlQahtani, “Flatiron School,” HBS case 817114, Jan. 2017. In contrast to early-stage startups: This paragraph and the next one are adapted from Eisenmann and Wagonfeld, “Scaling a Startup: People and Organizational Issues.” Chapter 9: Moonshots and Miracles “We wanted flying cars”: Daniel Weisfield, “Peter Thiel at Yale: We Wanted Flying Cars, Instead We Got 140 Characters,” Yale School of Management website, Apr. 27, 2013. He founded the startup Better Place: Unless otherwise noted, facts in the first three paragraphs of this chapter are from Max Chafkin, “A Broken Place: The Spectacular Failure of the Startup That Was Going to Change the World,” Fast Company, May 2014.

…

In any case, given our penchant for attribution errors—that is, blaming our own failures on uncontrollable circumstances and others’ failures on their personal faults—we should interpret founders’ explanations for startup failure with care. While most investors blame bad jockeys for startup failure, some see slow horses as the main problem. For example, billionaire entrepreneur and investor Peter Thiel says that “all failed companies are the same: they failed to escape competition.” Paul Graham, founder of the elite accelerator Y Combinator, likewise holds that having a compelling solution to a customer’s problem—a strong horse—is the key to success: “There’s just one mistake that kills startups: not making something users want.

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

Chasing fast money on apps and games that appealed to a narrow demographic of young, educated urbanites, the Valley seemed to be out of ideas. Even leaders within the industry saw a place that was falling short of its promise. Peter Thiel became one of the more outspoken critics. “What Happened to the Future?” asked a 2011 manifesto issued by Thiel’s VC firm, Founders Fund. “We wanted flying cars; instead we got 140 characters.”14 DAY ONE Jeff Bezos also believed the Internet economy could do more. Visionary and relentless, Bezos already drew comparisons to Jobs for his intense management style and insistence on high standards.

…

The Hoover Tower points straight up.”17 The high-powered, high-profile Campbell gave his exit interview to a little student newspaper that was barely two years old and only published a few issues a year. The Stanford Review, however, was already making its mark as a self-styled voice of reason for Stanford’s conservative students. Founded in the late spring of 1987, the Review was the brainchild of a sophomore philosophy major named Peter Thiel. German-born and California-bred, a regional chess champion and J. R. R. Tolkien devotee, Thiel had arrived on campus as the battle of the Reagan library raged. For the remainder of his undergraduate years and as a Stanford law student immediately after, Thiel focused his considerable intellectual energies on the Review, making its libertarian-conservative views an inescapable feature of campus life as a fresh, even more polarizing battle erupted: the war over the undergraduate curriculum.

…

The academic administrators steering the place in this era went on to become influential political advisors in the next. Stanford University’s stormy Reagan years became the stage on which the politics of the next-generation Valley were formed. As sharply polarized as Left and Right were on Stanford’s campus during this time, some common threads connected them. Both Peter Thiel and Terry Winograd were concerned about freedom of speech on campus. Both Glenn Campbell and Don Kennedy believed that Stanford scholars had an opportunity, and a responsibility, to contribute to politics and policy. Both the students crying out for a new, multicultural curriculum and the conservative elders who tut-tutted at the closing of the American mind agreed that the college years shaped a person’s trajectory for the rest of their lives.

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by

Michael Bhaskar

Published 2 Nov 2021

But in the face of perhaps the biggest challenge for seventy-five years, government, corporate and even personal thinking was often trapped by the models of the past, incapable of building those of the future on the fly. Despite all our technologies, businesses and knowledge, we are vulnerable. Entrepreneur and investor Peter Thiel famously encapsulated the argument as ‘We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.’ But there is more to it than that – in the words of David Graeber, it encompasses ‘a profound sense of disappointment about the nature of the world we live in, a sense of a broken promise – of a solemn promise we felt we were given as children about what the adult world was supposed to be like’.5 This isn't just about flying cars and colonies on Mars, the tug of war between techno optimism and pessimism.

…

, Our World in Data, accessed 10 November 2020, available at https://ourworldindata.org/us-life-expectancy-low Rosling, Hans, with Rosling, Ola, and Rosling, Anna Rönnlund (2018), Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About The World – And Why Things Are Better Than You Think, London: Sceptre Ross, Alex (2017), The Industries of the Future, London: Simon & Schuster Rotman, David (2019), ‘AI is reinventing the way we invent’, MIT Technology Review, accessed 26 March 2019, available at https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/02/15/137023/ai-is-reinventing-the-way-we-invent/ Roy, Avik (2012), Stifling New Cures: The True Cost of Lengthy Clinical Drug Trials, New York: Manhattan Institute Sand, Shlomo (2018), The End of the French Intellectual: From Zola to Houellebecq, London: Verso Sandberg, Anders, Drexler, Eric, and Ord, Toby (2018), ‘Dissolving the Fermi Paradox’, arXiv, 1806.02404 Sarewitz, Dan (2016), ‘Saving Science’, The New Atlantis, accessed 24 December 2019, available at https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/saving-science Sargent, John F. (2020), ‘Global Research and Development Expenditures’, Congressional Research Service, accessed 31 May 2020, available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44283.pdf Sautoy, Marcus du (2017), What We Cannot Know: From Consciousness to the Cosmos, the Cutting Edge of Science Explained, London: Fourth Estate Sautoy, Marcus du (2019), The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think, London: Fourth Estate Scannell, J., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H. et al. (2012), ‘Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency’, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, Vol. 11, pp. 191–200 Scharf, Caleb (2015), The Copernicus Complex: The Quest for Our Cosmic (In)Significance, London: Penguin Scheu, René (2019), ‘PayPal founder and philosopher Peter Thiel: “The heads in Silicon Valley have aligned themselves”’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, accessed 9 April 2019, available at https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/peter-thiel-donald-trump-handelt-fuer-mich-zu-wenig-disruptiv-ld.1471818?reduced=true Schwab, Klaus (2017), The Fourth Industrial Revolution, London: Portfolio Penguin Schwartz, Peter (1991), The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World, Chichester: John Wiley Senior, Andrew, Jumper, John, Hassabis, Demis, and Kohli, Pushmeet (2020), ‘AlphaFold: Using AI for scientific discovery’, DeepMind, accessed 5 February 2020, available at https://deepmind.com/blog/article/AlphaFold-Using-AI-for-scientific-discovery Shambaugh, Jay, Nunn, Ryan, Breitwieser, Audrey, and Liu, Patrick (2018), The State of Competition and Dynamism: Facts about Concentration, Start-Ups, and Related Policies, Washington DC: The Hamilton Project Shaxson, Nicholas (2018), The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer, London: The Bodley Head Sheldrake, Rupert (2013), The Science Delusion: Freeing the Spirit of Enquiry, London: Coronet Shi, Feng, and Evans, James (2019), ‘Science and Technology Advance through Surprise’, arXiv, 1910.09370 Simonite, Tom (2014), ‘Technology Stalled in 1970’, MIT Technology Review, accessed 14 July 2019, available at https://www.technologyreview.com/2014/09/18/171322/technology-stalled-in-1970/ Singh, Jasjit, and Fleming, Lee (2010), ‘Lone Inventors as Sources of Breakthroughs: ‘Myth or Reality?’

…

The writer and executive Safi Bahcall talks of ‘loonshot’ business, say a small drug company or indie film crew, versus ‘franchises’ like big pharma companies and Hollywood studios.19 Franchise projects are entrenched blockbusters: the last Harry Potter, not the first; the iPhone XII, not the iPhone. Another analogue is what Peter Thiel calls ‘0-1’ businesses or ideas.20 Most businesses are ‘1-n’; they simply extrapolate possibilities from the kernel of an existing idea. In contrast, ‘0-1’ ideas exhibit something completely new, a ‘vertical’ or ‘intensive’ progress. It means searing originality, not copying or improving; the creation of new technology versus the globalisation of that technology.

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by

Jonathan Haskel

and

Stian Westlake

Published 4 Apr 2022

Although we do not often hear this critique from economists, it is widely cited by laypeople and by commentators in other academic disciplines who seem to share a belief that what goes on in today’s economy lacks the “realness” and authenticity that it should have and that it once had. The idea that the modern economy is unsatisfyingly fake is a recurrent theme in conservative critiques of modernity. We see it in investor Peter Thiel’s lament that “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Commentators make clear their belief that a lot of modern economic activity is somehow fake, inauthentic, or even fraudulent. This discontent became acute during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many Western countries found themselves short of ventilators and personal protective equipment and without the wherewithal to make them rapidly.

…

The rationale for subsidy is partly one of spillovers and partly the belief that young people are capital constrained. The fifty-year expansion of universities around the world is a manifestation of the quantity theory of intangibles. There is of course a widespread critique of this expansion; we see it in Peter Thiel’s rationale for setting up the Thiel Fellowships to fund smart kids not to attend university, and in the United Kingdom’s 2018 review of postsecondary education. This critique holds that a lot of university education isn’t worthwhile for students, employers, or society. Liberal arts degrees are too generic, and the nature of the university funding system provides very weak incentives for universities and for students to teach and study genuinely worthwhile things.

…

Two Political Problems None of these recommendations are particularly controversial, and most governments at least pay lip service to them. A left-leaning government might put more emphasis on government-set challenges, like the Green New Deal, and a right-leaning government might focus more on DARPA-style research and entrepreneurship. But the differences between Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or John McDonnell, on the one hand, and Peter Thiel or Dominic Cummings, on the other, are smaller than the similarities. This would not have been the case a decade ago. But working out the approximate policy mix is not the most difficult challenge here. Executing these policies, and doing so effectively and at scale, requires a government to confront some important political questions and to challenge some vested interests.

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America

by

George Packer

Published 4 Mar 2014

“The anthology of the top twenty-five sci-fi stories in 1970 was, like, ‘Me and my friend the robot went for a walk on the moon,’” Thiel said, “and in 2008 it was, like, ‘The galaxy is run by a fundamentalist Islamic confederacy, and there are people who are hunting planets and killing them for fun.’” Together with Sean Parker and two other friends, Thiel had started an early-stage venture capital firm called Founders Fund. It published an online manifesto about the future that began with a complaint: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” There was no single cause of the tech slowdown. Perhaps there were no more easy technological problems, those had all been solved a generation ago and the big problems left were really hard ones, like making artificial intelligence work. Perhaps science and engineering were losing their prestige along with their federal funding.

…

John Russo, “Integrated Production or Systematic Disinvestment: The Restructuring of Packard Electric” (unpublished paper, 1994). Sean Safford, Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown: The Transformation of the Rust Belt (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). PETER THIEL AND SILICON VALLEY Sonia Arrison, 100 Plus: How the Coming Age of Longevity Will Change Everything, from Careers and Relationships to Family and Faith, with a foreword by Peter Thiel (New York: Basic Books, 2011). Eric M. Jackson, The PayPal Wars: Battles with eBay, the Media, the Mafia and the Rest of Planet Earth (Los Angeles: World Ahead Publishing, 2010). David Kirkpatrick, The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

…

Clinton had banned top officials who left the administration from contacting the federal government for five years. The rule applied to Quinn but not to Connaughton, who wasn’t senior enough. So, at the age of thirty-seven, he joined Arnold & Porter and launched a new career: as a lobbyist. SILICON VALLEY Peter Thiel was three years old when he found out that he was going to die. It was in 1971, and he was sitting on a rug in his family’s apartment in Cleveland. Peter asked his father, “Where did the rug come from?” “It came from a cow,” his father said. They were speaking German, Peter’s first language—the Thiels were from Germany, Peter had been born in Frankfurt.

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by

Edward Luce

Published 20 Apr 2017

With the exception of most of the 1990s, productivity growth has never recaptured the rates it achieved in the post-war decades. ‘You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics,’ said Robert Solow, the Nobel Prize-winning economist. Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire, who has controversially backed Donald Trump, put it more vividly: ‘We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters [Twitter].’ That may be about to change, with the acceleration of the robot revolution and the spread of artificial intelligence. But we should be careful what we wish for. The squeeze is already uncomfortable enough. I am nearing fifty.

…

But there are gaping holes in this pleasant reverie. The digital revolution is still in its infancy, yet we are already throwing our toys out of the pram. As political societies, we are further away from plausible solutions than when the digital revolution began. Unlike the Industrial Revolution, it is taking place in a hyper-democratic world. Peter Thiel was right, of course; Twitter cannot be compared to the invention of printing, or flying cars. Yet he was also wrong. We live in a world where everyone with a grievance wields more digital power in the palm of their hand than the computers that sent Apollo 14 into orbit. The Industrial Revolution was unleashed on undemocratic – or in the case of Britain and the US, semi-democratic – societies.

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by

Tim Fernholz

Published 20 Mar 2018

Musk was now asking Founders Fund to invest $20 million— 10 percent of its current funds—in SpaceX. Whatever personal enmity had led the team to eject Musk from the CEO suite at PayPal, it had not exhausted their faith in him as an entrepreneur. The Founders Fund manifesto famously complained that “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” an unsubtle dig at Twitter and what they saw as the limited ambitions of other Silicon Valley investors. Given a chance to invest in a rocket ship, they said yes, and the first outside investment in SpaceX was sealed in early 2008. The backing of the US space agency and Silicon Valley allowed Musk to avoid the fate of his competitors.

…

It was an attitude he had developed as an entrepreneur in the early days of the internet boom. Not many had thought that a new way of paying for goods and services on the internet was necessary in 1999. But Musk and the other members of the so-called PayPal Mafia—many of whom, like the investors Peter Thiel and Luke Nosek, would also back SpaceX—were not deterred. Once they had built their simple tool for exchanging money safely over the emerging consumer web, other entrepreneurs found ways to use it. The ability to exchange money online became the basis for a whole new economy. When the auction site eBay paid $1.5 billion for PayPal in 2002, Musk’s share of the proceeds provided him with the fortune to find new markets—including in space.

…

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. In 2001, Musk was at loose ends. He had sold his advertising start-up, Zip2, to Compaq two years earlier, for more than $300 million, earning a $22 million payout. PayPal, the online payment company that emerged from a merger between Musk’s next venture—an “online bank” called X.com—and Peter Thiel’s financial start-up Confinity, was now a booming success. But Musk had been forced out as CEO of the combined company after just a year, following clashes with other executives. Whatever the conflict, he remained a PayPal adviser, and the company’s biggest investor. And then, at age thirty, he reset his life.

Utopia for Realists: The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-Hour Workweek

by

Rutger Bregman

Published 13 Sep 2014

Demand doesn’t exist in a vacuum, after all; it’s the product of a constant negotiation, determined by a country’s laws and institutions, and, of course, by the people who control the purse strings. Maybe this is also a clue as to why the innovations of the past 30 years – a time of spiraling inequality – haven’t quite lived up to our expectations. “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” mocks Peter Thiel, Silicon Valley’s resident intellectual.16 If the post-war era gave us fabulous inventions like the washing machine, the refrigerator, the space shuttle, and the pill, lately it’s been slightly improved iterations of the same phone we bought a couple years ago. In fact, it has become increasingly profitable not to innovate.

…

See: Tony Schwartz and Christine Poratz, “Why You Hate Work,” The New York Times (May 30, 2014). http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/01/opinion/sunday/why-you-hate-work.html?_r=1 15. Will Dahlgreen, “37% of British workers think their jobs are meaningless”, YouGov (August 12, 2015). https://yougov.co.uk/news/2015/08/12/british-jobs-meaningless 16. Peter Thiel, “What happened to the future?” Founders Fund, http://www.foundersfund.com/the-future 17. William Baumol, “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive,” Journal of Political Economy (1990), pp. 893-920. 18. Sam Ro, “Stock Market Investors Have Become Absurdly Impatient,” Business Insider (August 7, 2012). http://www.businessinsider.com/stock-investor-holding-period-2012-8 19.

The Future Is Faster Than You Think: How Converging Technologies Are Transforming Business, Industries, and Our Lives

by

Peter H. Diamandis

and

Steven Kotler

Published 28 Jan 2020

At the turn of the last century, in a now famous IBM commercial, comedian Avery Brooks asked: “It’s the year 2000, but where are the flying cars? I was promised flying cars. I don’t see any flying cars. Why? Why? Why?” In 2011, in his “What Happened to the Future?” manifesto, investor Peter Thiel echoed this concern, writing: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Yet, as should be clear by now, the wait is over. The Flying Cars Are Here. And the infrastructure’s coming fast. While we were sipping our lattes and checking our Instagram, science fiction became science fact. And this brings us back to our initial question: Why now?

…

A half-dozen companies are now involved in this effort, producing about a dozen drugs that obliterate zombie cells, delaying or alleviating everything from frailty and osteoporosis to cardiological dysfunction and neurological disorder. Backed by investments from Jeff Bezos, the late Paul Allen, and Peter Thiel, Unity Biotechnology is one of the most interesting of these. They’ve developed a way to identify, then kill senolytic cells, or at least they’ve developed a way that works in mice. But it really works. Periodic treatments from midlife forward both extend lifespan by 35 percent and keep the mouse healthier along the way.

…

Mannick, “mTOR Inhibition Improves Immune Function in the Elderly,” Science Translational Medicine, December 2014. drug called metformin: Nir Barzilai, “Metformin as a Tool to Target Aging,” Cell Metabolism, June 14, 2016. 23(6): pp. 1060-1065, See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5943638/. Jeff Bezos, Paul Allen, and Peter Thiel, Unity Biotechnology: See: https://unitybiotechnology.com. extend lifespan by 35 percent: Jan M van Deursen, “Senolytic Therapies for Healthy Longevity,” Science 364, no. 6441 (May 2019): 636–637. Samumed: Osman Kibar, author interview, 2018. See also: https://www.samumed.com/default.aspx. Backed by a $12 billion valuation: Brian Gormley, “Drugmaker Samumed Closes $438 Million Round at $12 Billion Pre-Money Valuation,” Wall Street Journal Pro, August 6, 2018.

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

But since the maturation of digital communications technologies, and the internet in particular, a common view has set in that innovation has seemed to slow down. Now there are plenty of new apps and derivative consumer products, but the type of discoveries of the twentieth century seem to have become much rarer. Venture capitalist Peter Thiel has voiced these concerns many times, and his firm, Founders Fund, once subtitled its manifesto, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” in reference to Twitter. Thiel acknowledged the importance of the state’s role in funding basic research in the past, but argued it cannot be replicated in the present. He dreamed of the return of modernist planners like Robert Moses who disregarded how their projects affected the residents of the cities they oversaw, and did not believe the modern political system could deliver technological progress because governments would not “cut health-care spending in order to free up money for biotechnology research” or “make serious cuts to the welfare state in order to free up serious money for major engineering projects.”14 For Thiel, the successes of the past were not because of expansive spending on major public projects like the New Deal and the Interstate Highway System, but rather in spite of it, and the government no longer has the capacity to direct any such project.

…

Understanding the Silicon Valley Worldview 1 Margaret O’Mara, The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, Penguin Books, 2020, p. 7. 2 Ibid., p. 15. 3 AnnaLee Saxenian, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, Harvard University Press, 1996. 4 O’Mara, The Code, pp. 75–6. 5 Tom Wolfe, “The Tinkerings of Robert Noyce,” Esquire, December 1983, Classic.esquire.com. 6 Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 31. 7 Ibid., p. 73. 8 Ibid., p. 76. 9 Ibid., p. 14. 10 Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture 6:1, 1996, imaginaryfutures.net. 11 Saxenian, Regional Advantage, p. 90. 12 O’Mara, The Code, p. 214. 13 Ibid., p. 226. 14 Peter Thiel, “The End of the Future,” National Review, October 3, 2011, Nationalreview.com. 15 Tom Simonite, “Technology Stalled in 1970,” MIT Technology Review, September 18, 2014, Technologyreview.com. 16 David Graeber, “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit,” The Baffler 19, March 2012, Thebaffler.com. 17 O’Mara, The Code, pp. 90–1. 18 Tim Maughan, “The Modern World Has Finally Become Too Complex for Any of Us to Understand,” OneZero, November 30, 2020, Onezero.medium.com. 19 Ibid. 20 Senator Gore, speaking on S. 1067, 101st Congress, 1st sess., Congressional Record 135, May 18, 1989, S 9887. 21 Daniel Greene, The Promise of Access: Technology, Inequality, and the Political Economy of Hope, MIT Press, 2011. 22 Madeline Carr, US Power and the Internet in International Relations: The Irony of the Information Age, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, p. 58 (author’s emphasis). 23 Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, p. 194. 24 John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” February 8, 1996, Eff.org. 25 Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, p. 209. 26 Ibid., p. 222. 27 Ibid. 28 Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs.

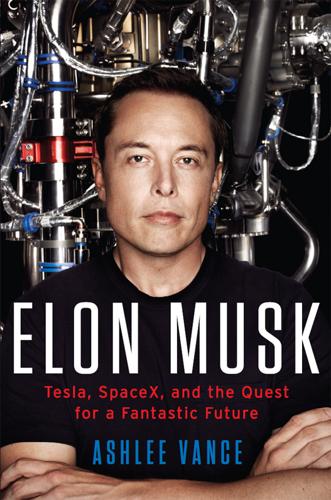

Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future

by

Ashlee Vance

Published 18 May 2015

“I think the probability of us discovering another top-one-hundred-type invention gets smaller and smaller,” Huebner told me in an interview. “Innovation is a finite resource.” Huebner predicted that it would take people about five years to catch on to his thinking, and this forecast proved almost exactly right. Around 2010, Peter Thiel, the PayPal cofounder and early Facebook investor, began promoting the idea that the technology industry had let people down. “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters” became the tagline of his venture capital firm Founders Fund. In an essay called “What Happened to the Future,” Thiel and his cohorts described how Twitter, its 140-character messages, and similar inventions have let the public down.

…

The whole idea was to shift away from slow-moving banks with their mainframes taking days to process payments and to create a kind of agile bank account where you could move money around with a couple of clicks on a mouse or an e-mail. This was revolutionary stuff, and more than 200,000 people bought into it and signed up for X.com within the first couple of months of operation. Soon enough, X.com had a major competitor. A couple of brainy kids named Max Levchin and Peter Thiel had been working on a payment system of their own at their start-up called Confinity. The duo actually rented their office space—a glorified broom closet—from X.com and were trying to make it possible for owners of Palm Pilot handhelds to swap money via the infrared ports on the devices. Between X.com and Confinity, the small office on University Avenue had turned into the frenzied epicenter of the Internet finance revolution.

…

From new kinds of energy storage systems to electric cars and solar panels, the technology never quite lived up to its billing and required too much government funding and too many incentives to create a viable market. Much of this criticism was fair. It’s just that there was this Elon Musk guy hanging around who seemed to have figured something out that everyone else had missed. “We had a blanket rule against investing in clean-tech companies for about a decade,” said Peter Thiel, the PayPal cofounder and venture capitalist at Founders Fund. “On the macro level, we were right because clean tech as a sector was quite bad. But on the micro level, it looks like Elon has the two most successful clean-tech companies in the U.S. We would rather explain his success as being a fluke.

Give People Money

by

Annie Lowrey

Published 10 Jul 2018

You can look around you on an airplane, and it’s little different from 40 years ago—maybe it’s a bit slower because the airport security is low-tech and not working terribly well,” Peter Thiel, a billionaire tech investor and adviser to President Trump, recently mused to Vox. “The screens are everywhere, though. Maybe they’re distracting us from our surroundings.” (He more famously said, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”) It could also be that our sluggish rate of economic growth has spurred our sluggish rate of innovation. The economist J. W. Mason of the Roosevelt Institute, a left-of-center think tank, argues that depressed demand for goods and services and crummy wages across the economy have reduced the impetus for businesses to get leaner, more productive, and more creative.

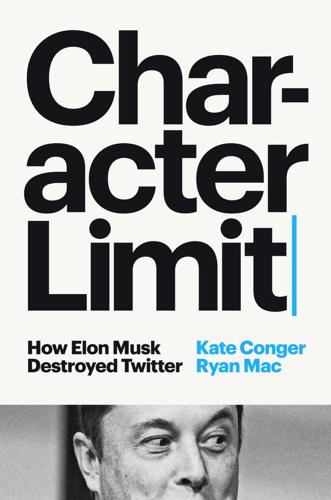

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter

by

Kate Conger

and

Ryan Mac

Published 17 Sep 2024

(“Jack doesn’t want to come back,” Musk replied. “He is focused on Bitcoin.”) Not everyone that Musk or his bankers approached, however, forked over checks. Founders Fund, the venture fund founded by Peter Thiel, Musk’s PayPal cofounder and frenemy, was among the tech investors who seemed unimpressed by the venture. Thiel was not a fan of Twitter. “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” Thiel famously once said, mocking Twitter’s original value proposition. His firm passed when approached by Musk’s team. Morgan Stanley also reached out to a diverse group of potential backers including Japanese investment conglomerate SoftBank, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, and Joe Rogan.

…

At twenty-eight, he was one of the few people in the nascent era of the consumer internet to have already sold a company. Why not hitch yourself to his star? But before X.com could take on the big credit card corporations, Musk found himself preoccupied with another competing start-up called Confinity. Its founders, Stanford University alums Peter Thiel, Max Levchin, and Luke Nosek, had developed a product called PayPal that allowed people online to email each other money. For a while, Confinity was located in the same Palo Alto building as X.com, leading some Confinity employees to believe that X had copied their product. The dot-com bubble burst in 2000, and by March of that year, both X.com and Confinity decided to merge under the X.com name.

The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare in the Robot Age

by

Roger Bootle

Published 4 Sep 2019

Yet the Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow famously remarked in 1987: “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” 29 (Mind you, the pickup in US productivity in the late 1990s suggests that the gains from computers were real but, as with many other advances, delayed.) The American entrepreneur and venture capitalist, Peter Thiel, has put recent technological disappointment more pithily. He has said: “We wanted flying cars. Instead, we got 140 characters.” This contention of Robert Gordon’s that technological progress has largely run its course is sensational. Think of it: the rapid development of the emerging markets slowing inexorably; overall economic progress essentially dribbling away to nothing; living standards barely rising at all; no prospect of the next generation being appreciably better off than the current one; a return to the situation and the outlook (if not the living standards) that pertained before the Industrial Revolution.

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by

Ian Goldin

and

Chris Kutarna

Published 23 May 2016

Despite the hundreds of billions of dollars we’ve plowed into medical research in the last 40 years, rich people only live some 8 percent (five years) longer than their grandparents, and we suffer from the same chronic diseases: cancer, heart disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s and organ failure. As Peter Thiel, who co-founded PayPal, put it: “We wanted flying cars—instead we got 140 characters.”36 Figure 6-1. To date, many expectations of the future have been disappointed. Image credit: Bill Watterston (1989). Calvin and Hobbes. Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved. Diminishing dreams All the above has sown a deeper doubt: that humanity’s glory days may be permanently past.

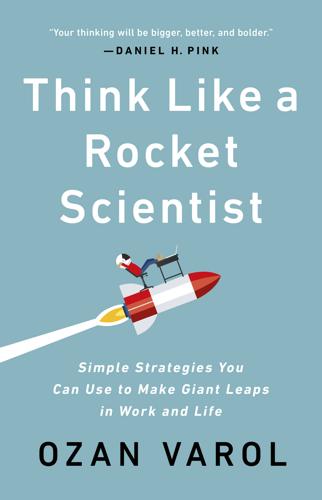

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

Shane Snow summarizes the relevant research in Smartcuts: “From 2001 to 2011, an investment in the 50 most idealistic brands—the ones opting for the high-hanging purpose and not just low-hanging profits—would have been 400 percent more profitable than shares of an S&P index fund.”15 Why? Moonshots appeal to human nature and attract more investors. Poking fun at the limited ambitions of most Silicon Valley firms, the manifesto for Founders Fund—a prominent venture-capital firm—reads: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”16 The firm became the first outside investor in SpaceX’s moonshots. Moonshots are also talent magnets. This is why SpaceX and Blue Origin have been able to cherry-pick the best rocket scientists from traditional aerospace companies and make them work around the clock on audacious engineering projects.

…

This approach provides psychological safety to those who might otherwise withhold dissent for fear of offending you. If you can’t find opposing voices, manufacture them. Build a mental model of your favorite adversary, and have imaginary conversations with them. This is what Marc Andreessen does. “I have a little mental model of Peter Thiel,” explains Andreessen, referring to fellow venture capitalist and PayPal cofounder, “a simulation that lives on my shoulder, and I argue with him all day long.”59 He added, “People might look at you funny while it’s happening,” but it’s well worth the ridicule. The voice of dissent could be anyone.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by

Steven Pinker

Published 13 Feb 2018

Capitalism has lost its capitalists: too much investment is tied up in “gray capital,” controlled by institutional managers who seek safe returns for retirees. Ambitious young people want to be artists and professionals, not entrepreneurs. Investors and the government no longer back moonshots. As the entrepreneur Peter Thiel lamented, “We wanted flying cars; instead we got 140 characters.” Whatever its causes, economic stagnation is at the root of many other problems and poses a significant challenge for 21st-century policymakers. Does that mean that progress was nice while it lasted, but now it’s over? Unlikely! For one thing, growth that is slower than it was during the postwar glory days is still growth—indeed, exponential growth.

…

Variously attributed; quoted in Brand 2009, p. 75. 89. Necessity for standardization: Shellenberger 2017. Selin quote: Washington Post, May 29, 1995. 90. Fourth-generation nuclear power: Bailey 2015; Blees 2008; Freed 2014; Hargraves 2012; Naam 2013. 91. Fusion power: E. Roston, “Peter Thiel’s Other Hobby Is Nuclear Fusion,” Bloomberg News, Nov. 22, 2016; L. Grossman, “Inside the Quest for Fusion, Clean Energy’s Holy Grail,” Time, Oct. 22, 2015. 92. Advantages of technological solutions to climate change: Bailey 2015; Koningstein & Fork 2014; Nordhaus 2016; see also note 103 below. 93.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by

Robert J. Gordon

Published 12 Jan 2016

For us to determine that labor productivity and TFP growth were even quicker during 1941–50 does not diminish the boldness of Field’s imagination with his claim or the depth of evidence that he has marshaled to support it.61 Chapter 17 INNOVATION: CAN THE FUTURE MATCH THE GREAT INVENTIONS OF THE PAST? We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters. —Peter Thiel INTRODUCTION The epochal rise in the U.S. standard of living that occurred from 1870 to 1940, with continuing benefits to 1970, represent the fruits of the Second Industrial Revolution (IR #2). Many of the benefits of this unprecedented tidal wave of inventions show up in measured GDP and hence in output per person, output per hour, and total factor productivity (TFP), which as we have seen grew more rapidly during the half-century 1920–70 than before or since.

…

Dick Tracy’s wrist radio in cartoon comic strips of the late 1940s finally is coming to fruition seventy years later with the Apple Watch. The Jetsons’ vertical commuting car/plane never happened, and in fact high fuel costs caused many local helicopter short-haul aviation companies to shut down.43 As Peter Theil quipped, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” THE INVENTIONS THAT ARE NOW FORECASTABLE Despite the slow growth of TFP recorded by the data of the decade since 2004, commentators view the future of technology with great excitement. Nouriel Roubini writes, “[T]here is a new perception of the role of technology. Innovators and tech CEOs both seem positively giddy with optimism.”44 The well-known pair of techno-optimists Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee assert that “we’re at an inflection point” between a past of slow technological change and a future of rapid change.45 They appear to believe that Big Blue’s chess victory and Watson’s victory on the TV game show Jeopardy presage an age in which computers outsmart humans in every aspect of human work effort.