Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control

by

Medea Benjamin

Published 8 Apr 2013

They bought the 38-inch-long Raven that is launched by simply throwing it into the air; the 27-foot-long Predator with its Hellfire missiles, and later the more powerful Reaper version; the 40-foot-long Global Hawk with sci-fi surveillance capabilities. The Pentagon was ordering these machines faster than the companies could produce them. In 2000, the Pentagon had fewer than fifty aerial drones; ten years later, it had nearly 7,500. Most of these were mini-drones for battlefield surveillance, but they also had about 800 of the bigger drones, ranging in size from a private aircraft to a commercial jet. Then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said that the next generation of fighter jet, the F-35 that took decades to develop at a cost of more than $500 million each, would be the Pentagon’s last manned fighter aircraft.12 From 2002–2010, the Department of Defense’s unmanned aircraft inventory increased more than forty-fold.13 Even during the financial crisis that started brewing in 2007 and led to the slashing of government programs from nutrition supplements for pregnant women to maintenance of national parks, the Defense Department kept pouring buckets of money into drones.

…

Dripping with sexual innuendos, Lockheed brags that the Romeo can “lock onto targets before or after launch,” “engage targets to the side and behind them without maneuvering into position,” and thanks to its more virile guidance and navigation capabilities, can “increase the missile’s impact angle and enhancing lethality.”65 Speaking about this man’s man of missiles, managing editor Gareth Jennings from Jane’s Missiles and Rockets gushed, “Before you would have to employ a specific missile-type to take out a particular kind of target—tank, truck, foot soldier. This allows the aircraft to engage ‘targets of opportunity’ as they appear on the battlefield.”66 Proving that size is not everything, Lockheed Martin is also getting into the drone business in smaller ways. It is developing a concept drone called the Samarai Monocopter, which the magazine Popular Mechanics reports is inspired by “the winding flight of a falling maple seed.” This would almost be beautifully poetic were its purpose not to provide “a powerful…tool for soldiers” on the battlefield.67 Lockheed’s contribution to the new world of warfare doesn’t stop there.

…

Chief among Lockheed’s drones is the stealth RQ-170 Sentinel model primarily used by the US Air Force and better known because of its enormous size as the “Beast of Kandahar.” Beyond acknowledging its massive, roughly forty-foot wingspan drone, the military has been characteristically tight lipped about its role on the battlefield. But according to the National Journal’s Marc Ambinder, it was that very Lockheed Martin drone that provided surveillance for the Navy SEAL operation that ended in the execution of Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.68 Less exciting for the company is the fact that it was this very model that showed up on TV screens around the world, in the hands of the Iranian government.

How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales From the Pentagon

by

Rosa Brooks

Published 8 Aug 2016

They can be used both for surveillance purposes and to carry out missile strikes; they can even provide close air support to troops engaged in combat. NGO and press reports suggest that it wasn’t until 2004 that drone strikes were again used outside the more traditional “hot battlefields” of Iraq and Afghanistan. In June 2004, a drone strike killed Nek Mohammed, a Pakistani militant leader, along with at least six others, including two children.4 As with the Yemeni strike in 2002, no U.S. officials would go on the record and explain exactly how Nek Mohammed ended up dead. Local residents reported hearing a drone flying nearby, and the New York Times later reported that Mohammed himself had “asked one of his followers about the strange, metallic bird hovering above him.”

…

Pakistani military officials dismissed reports of U.S. involvement as “absurd,” however, and insisted that Pakistan had the military capabilities to carry out such strikes on its own.5 Over the ensuing years, the number of U.S. drone strikes outside traditional hot battlefields began to increase, slowly at first and then more rapidly. In 2005, there were 3 reported drone strikes in Pakistan, followed by 2 more in 2006 and 4 in 2007. In 2008, the last year of the Bush presidency, there were 36. In 2009, the first year of the Obama administration, there were 52. In 2010, there were 122. After that, the number of reported annual strikes began to decline again: in 2014, there were 23 strikes reported.6 In Yemen, however, the pace of drone strikes picked up even as the number of strikes in Pakistan began to decline: there were no known strikes in Yemen between late 2002 and 2009, followed by one in 2010, 9 in 2011, and 47 in 2012, after which the number of annual strikes again began to decline.

…

Special Operators can offer quiet assistance to foreign governments interested in capturing or killing terrorists in their territory, and, if necessary, they can take direct action themselves. As a result, they have increasingly been relied upon to capture or kill suspected terrorists outside of hot battlefields, both through quick cross-border raids and through the use of drone strikes. Much of the time, their precise role is—of necessity—kept secret. Foreign governments may want U.S. military help, but only if they can deny any American role. And when military operations raise difficult questions about sovereignty, keeping them secret is often less diplomatically embarrassing for all concerned.

Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War

by

Raj M. Shah

and

Christopher Kirchhoff

Published 8 Jul 2024

Nicknamed “the cages” for its labyrinth of chain-link enclosures once used to store weapons, the warehouse had no running water, air-conditioning, or heating. Blisteringly hot in summer, cold in winter, it was crammed full of lab benches, computer terminals, and real-time communications links to experimental drones and anti-drone equipment on the mock battlefield outside. Between them, Jacobsen and Beall owned nearly fifty drones of various models and makes. When they offered to donate them to DIUx to furnish the Batcave with a starter-kit of hardware, our lawyer informed them they couldn’t. DIUx lacked “gift authority,” so receiving free goods or services was against regulation. The lawyer never noticed that Beall and Jacobsen ignored her completely, replacing in time the drones they donated with ones purchased by DIUx.

…

“Red-teaming” was fun, but from there Rogue Squadron moved on to their first real project, scouring the software inside DJI drones to discover backdoors and vulnerabilities in the code. Nobody liked the idea of using Chinese drones, but battlefield operators knew DJI’s were better than anything else on the market and generations ahead of the standard-issue portable drones the army and marines sent to front-line combat units. We needed to find a way to use the DJI hardware. One of the vulnerabilities in DJI’s operating system enabled Beall to code a hack that could shut off the ability of a DJI drone to send data back to China—making it safe for U.S. operators to use in the field.

…

The Pentagon has an equally critical role to play by ingesting the technology being created for it. Its procurement dollars, if deployed to buy the products of VC-backed startups, will make the flywheel of capital-driven defense innovation spin ever faster. CHAPTER EIGHT UKRAINE AND THE BATTLEFIELD OF THE FUTURE The conflict in Ukraine became the war DIU had envisioned, fought with drones, satellites, and artificial intelligence, hackers on both sides launching cyberattacks, and Ukrainian citizens using smartphone apps to alert their military to enemy positions. It’s a hybrid war, with legacy technology like tanks and artillery used in combination with a digital overlay.

Exponential: How Accelerating Technology Is Leaving Us Behind and What to Do About It

by

Azeem Azhar

Published 6 Sep 2021

Disinformation may soften an adversary, sowing doubt in the population; cyberattacks may weaken the day-to-day operations of their economy. But if that doesn’t achieve your objective, killing their soldiers might. Some of the most rapid exponential changes in conflict have come about on the physical battlefield. Perhaps the best example is drone technology – pilotless aircraft controlled by soldiers from a remote location. The rise of drones might, at first, seem like a wholly different force to the growth of cyberattacks and disinformation. Viewed more broadly, however, we can see how drone warfare intertwines with and compounds other forms of attack.

…

A 1990s classic of military aerial surveillance, the MQ-1 Predator combat drone, cost $20 million per system unit (about $34 million in 2019 terms);47 whereas the Global Hawk drone downed by the Iranian military in 2019 cost $130 million.48 But other countries took advantage of exponential improvements in the core technologies to build drones on the cheap. The Turkish Bayraktar TB2, launched in 2014, is on the market for around $5 million.49 Along the way, these cheaper drones brought wholly new actors into military conflicts – battlefield warfare became affordable to any number of terrorist groups and small states. Military drones represent the inverse of traditional flagship military technologies – the ballistic missiles, nuclear weapons, aircraft carriers and stealth fighters that remain the privilege of a handful of rich nations with mature defence industries. Increasingly, anyone can build a drone army.

…

When fighting broke out in the Nagorno-Karabakh region between Armenia and Azerbaijan in late 2020, drones were used on both sides. A regional proxy war involving Russia, Turkey, Israel and some Gulf nations, the conflict became a showcase of the latest drone technology. Thanks to its close links to Turkey and Israel, Azerbaijan was able to unleash a fleet of advanced drones on the battlefield, which ultimately gave it the upper hand. Such drones allowed Azerbaijani forces to penetrate deep into Armenian territory and wreak havoc on their supply lines.52 The Armenians lost more than 185 tanks and hundreds of other pieces of heavy military equipment – more than half its materiel at the start of the conflict. There was a human cost too.

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

by

James Barrat

Published 30 Sep 2013

A window for education about AI risk is starting to open. But any plan to create an advisory board or governing body over AI is already too late to avoid some kinds of disasters. As I mentioned in chapter 1, at least fifty-six countries are developing robots for the battlefield. At the height of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, three Foster-Miller SWORDS—machine gun-wielding robot “drones”—were removed from combat after they allegedly pointed their guns at “friendlies.” In 2007 in South Africa, a robotic antiaircraft gun killed nine soldiers and wounded fifteen in an incident lasting an eighth of a second. These aren’t full-blown Terminator incidents, but look for more of them ahead.

…

It’s not the least bit controversial to anticipate that when AGI comes about, it’ll be partly or wholly due to DARPA funding. The development of information technology owes a great debt to DARPA. But that doesn’t alter the fact that DARPA has authorized its contractors to weaponize AI in battlefield robots and autonomous drones. Of course DARPA will continue to fund AI’s weaponization all the way to AGI. Absolutely nothing stands in its way. DARPA money funded most of the development of Siri and is a major contributor to SyNAPSE, IBM’s effort to reverse engineer a human brain using brain-derived hardware.

…

W. LIDA (Learning Intelligent Distributed Agent) Lifeboat Foundation Lipson, Hod Loebner, Hugh Lynn, William J., III Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) Singularity Summit machine learning Madoff, Bernie malware Mazzafro, Joe McCarthy, John McGurk, Sean military battlefield robots and drones DARPA, see DARPA energy infrastructure and nuclear weapons, see nuclear weapons Mind Children (Moravec) Minsky, Marvin Mitchell, Tom mobile phones see also iPhone Monster Cat Moore, Gordon Moore’s Law morality see also Friendly AI Moravec, Hans Moravec’s Paradox mortality, see immortality mortgage crisis Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) nano assemblers nanotechnology “gray goo” problem and natural language processing (NLP) natural selection Nekomata (Monster Cat) NELL (Never-Ending-Language-Learning system) neural networks neurons New Scientist New York Times Newman, Max Newton, Isaac Ng, Andrew 9/11 attacks Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies (Perrow) normalcy bias North Korea Norvig, Peter Novamente nuclear fission nuclear power plant disasters nuclear weapons of Iran Numenta Ohana, Steve Olympic Games (cyberwar campaign) Omohundro, Stephen OpenCog Otellini, Paul Page, Larry paper clip maximizer scenario parallel processing pattern recognition Pendleton, Leslie Perceptron Perrow, Charles Piaget, Jean power grid Precautionary Principle programming bad evolutionary genetic ordinary self-improving, see self-improvement Rackspace rational agent theory of economics recombinant DNA Reflections on Artificial Intelligence (Whitby) resource acquisition risks of artificial intelligence apoptotic systems and Asilomar Guidelines and Busy Child scenario and, see Busy Child scenario defenses against lack of dialogue about malicious AI Precautionary Principle and runaway AI Safe-AI Scaffolding Approach and Stuxnet and unintended consequences robots, robotics Asimov’s Three Laws of in dangerous and service jobs in sportswriting Rosenblatt, Frank Rowling, J.

A Theory of the Drone

by

Gregoire Chamayou

Published 23 Apr 2013

Given that there can be no gradation in its use of force, the drone is incapable of conforming to the very specific principle of proportionality that applies in the law enforcement paradigm. As Mary Ellen O’Connell explains: “What drones cannot do is comply with police rules for the use of lethal force away from the battlefield. In law enforcement it must be possible to warn before using lethal force.”11 Some supporters claim that drones are analogous to the bulletproof vests worn by the police.12 They are efficient means of protecting the agents of the state police force, and such protection is legitimate. That may be so, but they are forgetting an essential difference: the wearing of a bulletproof vest does not prevent the taking of prisoners.

The Driver in the Driverless Car: How Our Technology Choices Will Create the Future

by

Vivek Wadhwa

and

Alex Salkever

Published 2 Apr 2017

In fact, the public has taken little interest in the question of robots being used to kill people even in the United States. In Dallas, police used a bomb carried on a robot to kill Micah Brown, the shooter who had allegedly killed seven officers at a protest rally.8 Few questioned this use of force. And the first autonomous robots’ use on the battlefield would likely be far away, as the battlefields on which drones first killed were, in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Open Roboethics initiative is advocating an outright ban on autonomous lethal robots, a call echoed by nearly every civil rights organization and by many politicians. The issue will play out over the next few years. It will be interesting to see not only what final decision comes from world governance bodies such as the United Nations but also the decision of the U.S. military establishment and its willingness to sign an international accord on the matter.

Mbs: The Rise to Power of Mohammed Bin Salman

by

Ben Hubbard

Published 10 Mar 2020

The centers found wives for the bachelors and granted married prisoners conjugal visits in a facility built like a hotel, with magnetic door cards, playgrounds for kids, and room service. There was never an independent audit to verify the approach’s effectiveness, but American officials came to appreciate it, and Saudis argued that it was more humane than locking people up indefinitely or killing them on the battlefield with drones. MBN once told a visiting American dignitary that it had pained him to learn that Saudis had played an outsized role in the September 11 attacks. “Terrorists stole the most valuable things we have,” he said. “They took our faith and our children and used them to attack us.” His approach to dealing with militancy extended to the families of dead militants, who were told their sons had been “victims,” not “criminals.”

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 14 Sep 2015

DARPA also developed another, much larger, “more complicated” drone that interested Wohlstetter, as revealed in an obscure 1974 internal DARPA review. Nite Panther and Nite Gazelle were helicopter drones, “equipped with a real time day-night battlefield reconnaissance capability including armor plate and self-sealing, extended-range fuel tanks.” The drone helicopters were deployed into the battlefield, starting in March 1968, in response to an urgent operational request from the Marine Corps. To create the Nite Panther drone, DARPA modified a Navy QH-50 DASH antisubmarine helicopter—originally designed to fire torpedoes at submerged submarines—and added a remotely controlled television system, called a “reconnaissance-observation system,” which could transmit real-time visuals back to a moving jeep, acting as a ground station.

…

Once DARPA technology is revealed on the battlefield, other nations inevitably acquire the science that DARPA pioneered. For example, in the early 1960s, during the Vietnam War, DARPA began developing unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones. It took three decades to arm the first drone, which then appeared on the battlefield in Afghanistan in October 2001. By the time the public knew about drone warfare, U.S. drone technology had advanced by multiple generations. Shortly thereafter, numerous enemy nations began engineering their own drones. By 2014, eighty-seven nations had military-grade drones. In interviewing former DARPA scientists for this book, I learned that at any given time in history, what DARPA scientists are working on—most notably in the agency’s classified programs—is ten to twenty years ahead of the technology in the public domain.

Twilight of Abundance: Why the 21st Century Will Be Nasty, Brutish, and Short

by

David Archibald

Published 24 Mar 2014

Bombs and strafing runs from a pair of F15 fighters and another pair of F16 fighters failed to eliminate the bunker, but it was destroyed by a Hellfire missile fired from a CIA drone aircraft at a fraction of the cost of using the conventional aircraft.8 And when al Qaeda forces recently overran northern Mali and started moving south, they were chased out of the country in a couple of weeks by mobile French troops using battlefield intelligence provided by drone aircraft. The tactics of drone warfare still have a long way to evolve. But drones are already drastically minimizing the cost of the long war against Islamic extremism. There is another reason why “the strong arms of science” will continue to widen the technological superiority of the West over Islam.

Robot Futures

by

Illah Reza Nourbakhsh

Published 1 Mar 2013

A recent news article in the Washington Post reports on drone maneuvers at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 2010, where roboticists have programmed an unmanned aerial vehicle to fly autonomously, use on-board cameras, and computer vision algorithms to search for an object on the ground, match it to a desired Brainspotting 103 target, then automatically fire on it (Finn 2011). The article goes on to explain that the eventual goal is for drones to have a database of enemy images and fly above a battlefield, looking for the desired targets with face recognition software. Following an image match, the drones would then make the autonomous decision to kill on their own. This is a poignant example because, from some distance, it may appear reasonable to a nonroboticist that drones can do face matching and then make lethal decisions. But to any roboticist aware of state-of-the-art computer vision and face recognition, the concept is absurdly out of touch with the reality in which face recognition can easily find false matches using anything from the rear end of a cow to a poster with the target’s picture pasted on it.

Spies, Lies, and Algorithms: The History and Future of American Intelligence

by

Amy B. Zegart

Published 6 Nov 2021

Which option is more moral: The military strike that is overt and democratically accountable but kills more people? Or the covert action that is secret and less accountable but saves more lives of combatants and innocent civilians? Fairness, moreover, looks different on the battlefield than it does in a classroom. When I asked one senior Navy officer what he thought of arguments that covert drone strikes were not fighting fair, he replied, “When I’m asking my sailors to risk their lives against terrorists, I don’t want a fair fight.” To get a feel for these moral dilemmas, consider the following scenario: A notorious international drug trafficker has just ousted the democratically elected leader in a foreign nation and declared a state of war against the United States.

I, Warbot: The Dawn of Artificially Intelligent Conflict

by

Kenneth Payne

Published 16 Jun 2021

The Perdix swarm was only a demonstration, but micro drones that size won’t have the endurance to travel far for recovery, and the mothership that launches them—F/A-18 or otherwise—might not have the capability to retrieve its flock, or be prepared for the risk of hanging about. One approach is to treat the units as ‘kamikaze’ drones—essentially loitering munitions that can persist in the battlefield before attacking at the appropriate time and place. The Israeli manufactured Harpy drone demonstrates the potential—able to patrol a predefined area looking for its designated target before swooping down and detonating on it.34 Even closer to our Special Forces patrol is the use of loitering grenades—ultra tactical weapons that look like micro drones you might buy from Amazon, but that carry an explosive charge underneath.

Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State

by

Dana Priest

and

William M. Arkin

Published 5 Sep 2011

The honoree for 2011, a year marking the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, couldn’t have been a more appropriate symbol of the new reality in Top Secret America: retired rear admiral and former director of national intelligence, now Booz Allen’s four-million-dollar man, J. Michael “Mike” McConnell. CHAPTER TEN Managing the Battlefield from a Suburban Sanctuary A pilot sits at a computer controlling a CIA drone loaded with weapons powerful enough to shatter a tank and accurate enough to be airmailed through a terrorist’s bedroom window. As analysts cross-reference video feeds with voice intercepts to confirm the target’s location, a weapons technician calculates the probability that innocent people walking nearby might get killed as well.

…

It also spawned a development and production frenzy within the niche community of manufacturers experimenting with other types of unmanned aircraft, and with the many larger defense contractors whose technology is used to move a drone’s surveillance pictures and targeting information around the world—from the battlefield to the sanctuary—in a matter of seconds. The number of drones in the U.S. arsenal has increased from sixty to more than six thousand since 9/11. Funding for drone-related projects and activities was about $350 million in 2001, when the first CIA Predator was being flown from a trailer once used as a daycare center in the parking lot of the agency’s headquarters.

Four Battlegrounds

by

Paul Scharre

Published 18 Jan 2023

Ninety drone patrols could rack up nearly 800,000 hours of video footage a year and monitoring those video feeds required a lot of eyeballs. Technology had, in some ways, only made the problem worse. To manage the overwhelming need for more ISR, the DoD had pushed development of wide area surveillance tools that could provide a “God’s eye” view of the battlefield. In 2014, the Air Force equipped a small number of Reaper drones with an advanced sensor system called Gorgon Stare that could surveil an entire city. Equipped with multiple cameras like a fly’s eye, the Gorgon Stare pods, which hung underneath the Reaper’s wings in lieu of bombs, could monitor dozens of square kilometers at once.

…

Marine Corps, 1997), https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCDP%201%20Warfighting.pdf. 277sports team: “Official Numbers of Players on a Team,” Factmonster.com, updated February 21, 2017, https://www.factmonster.com/sports/sports-section/official-numbers-players-team. 278Swarming tactics: Arquilla and Ronfeldt, Swarming and the Future of Conflict; Edwards, Swarming on the Battlefield; Edwards, Swarming and the Future of Warfare; Scharre, Robotics on the Battlefield Part II. 278mass drone attacks: David Reid, “A Swarm of Armed Drones Attacked a Russian Military Base in Syria,” CNBC, January 11, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/01/11/swarm-of-armed-diy-drones-attacks-russian-military-base-in-syria.html. 278first true drone swarm: David Hambling, “Israel Used World’s First AI-Guided Combat Drone Swarm in Gaza Attacks,” NewScientist, June 30, 2021, https://www.newscientist.com/article/2282656-israel-used-worlds-first-ai-guided-combat-drone-swarm-in-gaza-attacks/; Zak Kallenborn, “Israel’s Drone Swarm Over Gaza Should Worry Everyone,” Defense One, July 7, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2021/07/israels-drone-swarm-over-gaza-should-worry-everyone/183156/. 278Nonmilitary robot swarms: Self-Organizing Systems Research Group (website), Harvard University, 2021, https://ssr.seas.harvard.edu/. 279“span of control”: Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States. 279AI command and control: See also Kenneth Payne, I, Warbot: The Dawn of Artificially Intelligent Conflict (London: Hurst Publishers, June 2021), 127, https://www.amazon.com/Warbot-Dawn-Artificially-Intelligent-Conflict/dp/0197611699. 279hand over execution of swarm behavior: Payne, I, Warbot, 110. 279“‘shepherd’ model”: Garry Kasparov, “AlphaZero and the Knowledge Revolution,” foreword to Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan, Game Changer: AlphaZero’s Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI (Amsterdam: New in Chess, February 15, 2019), 10, https://www.amazon.com/Game-Changer-AlphaZeros-Groundbreaking-Strategies/dp/9056918184. 279Chen Hanghui of the PLA’s Army Command College: US-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on Trade, Technology, and Military-Civil Fusion, June 7, 2019 (testimony of Elsa B.

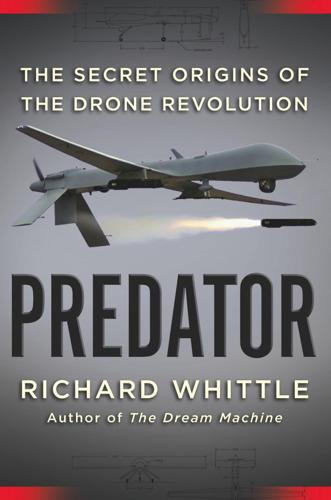

Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution

by

Richard Whittle

Published 15 Sep 2014

gave Aviation Week another rosy prognosis: “RPVs & Drones; Long-Term Observation and Radio Relay Missions Play Vital Navy Role,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, May 2, 1988, p. 70. boondoggle known as Aquila: “Aquila Remotely Piloted Vehicle, Its Potential Battlefield Contribution Still in Doubt,” United States General Accounting Office, October 1987, GAO/NSIAD—88-19. froze all spending on drones: Department of Defense Appropriation Bill, 1988, Senate Report 100–235, 100th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 250. navigated to within: Steve La Rue, “S.D. Firm’s Unmanned Plane Tested,” San Diego Union, December 1, 1988, p. C1. RPV master plan: Ronald D.

Excession

by

Iain M. Banks

Published 14 Jan 2011

Amorphia walked towards it, around and over the poised, charging cavalry and the fallen soldiers, between a pair of convincing-looking hanging fountains of earth where two cannon balls were slamming into the ground and over a small, blood-swollen stream to another part of the battlefield, where a team of three revival drones were floating above a revivee. This was unusual; people normally wanted to be woken back in their home and in the presence of friends, but over the last couple of decades - as the tableaux had become more impressive - more people had wished to be brought back to life here, in the midst of them.

Augmented: Life in the Smart Lane

by

Brett King

Published 5 May 2016

He pointed out that Amazon is already deploying its ninth generation of aerial vehicle, has ex-NASA engineers (including an astronaut) on staff working on the project and that “one day, seeing Amazon Prime Air will be as normal as seeing mail trucks on the road”. The use of drones has been toyed with in battlefields since World War II. The United States started working in earnest on drones as early as the Vietnam War, but it wasn’t until the 1982 Israeli conflict with Syria when unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were used with significant success. Since then, the drones being deployed in the theatre of war have become incredibly sophisticated. On 16th April 2015, the US Navy demonstrated the ability of its X-47B unmanned carrier air vehicle demonstrator (UCAS-D) to conduct mid-air refuelling with a KC-707 tanker.

Lions of Kandahar: The Story of a Fight Against All Odds

by

Rusty Bradley

and

Kevin Maurer

Published 27 Jun 2011

Innovation and Its Enemies

by

Calestous Juma

Published 20 Mar 2017

Self-driving cars will restructure transportation through new ownership patterns, insurance arrangements, and business models. Computer-aided diagnosis, robotic surgery, and myriad medical devices are already changing the role of doctors and how medical care is provided.7 Artificial intelligence and computer algorithms are influencing the way basic decisions are made. Battlefields are being automated with drones and other autonomous vehicles doing the work that used to be performed by a wide range of military personnel. Some of the advances are already shifting the locus of product development. Data-based firms such as Google and IBM are moving into pharmaceutical research. Sharing services such as Uber are acquiring robotics and other engineering capabilities.

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by

Alec Ross

Published 13 Sep 2021

Yet Western companies have freely exported these technologies for years, Edelman said, and “I think most members of the American public and certainly a lot of public policymakers wish they hadn’t.” Beyond this gray area, there are algorithms that can be even more consequential. Today, companies are developing systems that can identify enemy combatants on the battlefield, power semiautonomous weapons, and coordinate drone swarms. Edelman explained that certain types of AI can be more easily weaponized than others and that “those are the sorts of implementations that it is entirely appropriate to regulate, and frankly, government’s a little bit behind the ball in identifying them.” US military leaders have begun to stress the importance of AI ethics, and in 2020 the Pentagon signed on to a set of five broad principles for the ethical application of the technology.

Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War

by

Paul Scharre

Published 23 Apr 2018

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 28 Sep 2014

If we, as civilians, have yet to grapple with the ethical implications of self-driving cars and other autonomous robots, the situation is very different in the military. For years, defense departments and military academies have been studying the methods and consequences of handing authority for life-and-death decisions to battlefield machines. Missile and bomb strikes by unmanned drone aircraft, such as the Predator and the Reaper, are already commonplace, and they’ve been the subject of heated debates. Both sides make good arguments. Proponents note that drones keep soldiers and airmen out of harm’s way and, through the precision of their attacks, reduce the casualties and damage that accompany traditional combat and bombardment.

Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin's Most Dangerous Hackers

by

Andy Greenberg

Published 5 Nov 2019

Genius Makers: The Mavericks Who Brought A. I. To Google, Facebook, and the World

by

Cade Metz

Published 15 Mar 2021

Area 51: An Uncensored History of America's Top Secret Military Base

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 16 May 2011

CIA drones had provided intelligence for NATO forces in the 1999 Kosovo air campaign, collecting intelligence, searching for targets, and keeping an eye on Kosovar-Albanian refuge camps. The CIA Predator had helped war planners interpret the chaos of the battlefield there. Now, the Air Force needed the CIA’s help going into Afghanistan with drones. The first reconnaissance drone mission in the war on terror was flown over Kabul, Afghanistan, just one week after 9/11, on September 18, 2001. Three weeks later, the first Hellfire-equipped Predator drone was flown over Kandahar. The rules of aerial warfare had changed overnight.

The Future of War

by

Lawrence Freedman

Published 9 Oct 2017

Jenna Jordan in ‘When heads roll: Assessing the effectiveness of leadership decapitation’, Security Studies 18.4 (2009) suggests that ideological groups are more vulnerable to decapitation than religious groups, and are hierarchical more than decentralised, and also that the tactic can be counterproductive. Stephanie Carvin, ‘The Trouble with Targeted Killing’, Security Studies 21:5, (2012), 29–555. 13. Avery Plaw, Matthew S. Fricker, and Carlos R. Colon, The Drone Debate: A Primer on the U.S. Use of Unmanned Aircraft Outside Conventional Battlefields (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015). It’s hard to know exactly how many civilians have been killed by drones, since insurgents inevitably insist that the victims were innocent noncombatants, while the US government has tended to count most of those killed as combatants. For an idea of scale, the administration put the numbers killed outside the recognized war zones of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria between January 2009 and December 2015 as between 2,372 and 2,581 combatants and between 64 and 116 civilians, while the London-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimated that as of August 2016 US drone strikes had killed between 492 and 1,138 civilians in Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen. 14.

Team Human

by

Douglas Rushkoff

Published 22 Jan 2019

These arguments never acknowledge the outsourced slavery, toxic dumping, or geopolitical strife on which this same model depends. So while one can pluck a reassuring statistic to support the notion that the world has grown less violent—such as the decreasing probability of an American soldier dying on the battlefield—we also live with continual military conflict, terrorism, cyber-attacks, covert war, drone strikes, state-sanctioned rape, and millions of refugees. Isn’t starving a people and destroying their topsoil, or imprisoning a nation’s young black men, a form of violence? Capitalism no more reduced violence than automobiles saved us from manure-filled cities.

Homeland: The War on Terror in American Life

by

Richard Beck

Published 2 Sep 2024

The war on terror gives the lie to or at least complicates the old expression about how wars “come home,” the idea that the way a country practices military violence overseas will eventually show up in its policing, or how traumatized veterans will wreak havoc in their communities upon their return from foreign battlefields. Well before Barack Obama inaugurated his drone warfare campaign across the Middle East and the Horn of Africa, before the Bush administration started agitating for the invasion of Iraq, and even before the United States dropped a single bomb on Afghanistan, the government began rounding up Muslims inside its own borders, and vigilantes across the country sought out mosques to vandalize and people on the streets who appeared to be Muslim or Arab to harass and intimidate.

The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities

by

John J. Mearsheimer

Published 24 Sep 2018

Obama had a kill list known as the “disposition matrix,” and every Tuesday there was a meeting in the White House—it was called “Terror Tuesday”—where the next victims were selected.91 The extent to which the Obama administration bought into this strategy is reflected in the distribution of drone strikes between November 2002, when they began, and May 2013. Micah Zenko reports that there were “approximately 425 non-battlefield targeted killings (more than 95 percent by drones). Roughly 50 took place during Mr. Bush’s tenure, and 375 (and counting) under Mr. Obama’s.”92 As the journalist Tom Engelhardt writes, “Once upon a time, off-the-books assassination was generally a rare act of state that presidents could deny. Now, it is part of everyday life in the White House and at the CIA.

The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos

by

Christian Davenport

Published 20 Mar 2018

Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield

by

Jeremy Scahill

Published 22 Apr 2013

As the civilian death toll mounted, the Afghan insurgency intensified. The US “targeted” killing program was fueling the very threat it claimed to be fighting. The Year of the Drone YEMEN AND THE UNITED STATES, 2010 —As thousands of US troops deployed and redeployed to Afghanistan, the covert campaign in undeclared battlefields elsewhere was widening. US drone strikes were hitting Pakistan weekly, while JSOC forces were on the ground in Somalia and Yemen and pounding the latter with air strikes. All the while, al Qaeda affiliates in those countries were gaining strength. When I met again with Hunter, who worked with JSOC under Bush and continued to work in counterterrorism under the Obama administration, I asked him what changes had taken place from one administration to the next.

Dark Mirror: Edward Snowden and the Surveillance State

by

Barton Gellman

Published 20 May 2020

One report on a surveillance operation in progress took a break from matters at hand to joke about what happens when the “mulla [sic] mixes his viagra with his heroin.” (“Now he gets an erection but can’t stand up.”) Save for the last example, these are bureaucratically vetted teaching materials. The levity extends to battlefield support for U.S. Special Forces and CIA drone operators. The work of the SIGINT Directorate, when it locates and identifies enemy combatants, can have immediate life-and-death stakes. In unguarded moments, as NSA personnel put crosshairs on an enemy, they display a gamer’s detachment from bloodshed. A surveillance photo in one official briefing depicted a man in Arab headdress strumming an instrument, oblivious to what the context suggests is his impending demise.

Because We Say So

by

Noam Chomsky

There is a long and highly instructive history showing the willingness of state authorities to risk the fate of their populations, sometimes severely, for the sake of their policy objectives, not least the most powerful state in the world. We ignore it at our peril. There is no need to ignore it right now. A remedy is investigative reporter Jeremy Scahill’s just-published DIRTY WARS: THE WORLD IS A BATTLEFIELD. In chilling detail, Scahill describes the effects on the ground of U.S. military operations, terror strikes from the air (drones), and the exploits of the secret army of the executive branch, the Joint Special Operations Command, which rapidly expanded under President George W. Bush, then became a weapon of choice for President Obama. We should bear in mind an astute observation by the author and activist Fred Branfman, who almost single-handedly exposed the true horrors of the U.S.

These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means

by

Christopher Summerfield

Published 11 Mar 2025

Freely available Palantir marketing videos demonstrate how LLMs can be used to answer queries about enemy troop types and movements, and to issue natural-language instructions to deploy surveillance drones (‘task the MQ9 to capture footage of this area’). So we are already in an era in which LLMs are being used to collect and interpret battlefield intelligence, and to directly control potentially lethal autonomous vehicles and drones. The natural language processing, reasoning, and image-analysis capabilities of LLMs make them ideally suited for helping humans with real-time command and control. You can imagine that LLMs could soon be used to issue commands in natural language to a drone swarm like Lanius, especially as text-to-speech technologies now allow queries to be spoken rapidly out loud.

The 9/11 Wars

by

Jason Burke

Published 1 Sep 2011

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 14 May 2014

The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power

by

Jacob Helberg

Published 11 Oct 2021

Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century

by

P. W. Singer

Published 1 Jan 2010

As noted earlier, something similar has already happened in the air with human pilots, who no longer sit inside most reconnaissance planes and have even less to do with the unmanned versions. Indeed, as army drone pilot Sergeant Chris Hermann says, “We all joke about it. A monkey can do this job, this bird flies itself, it lands itself.” When the weather is bad and their drone can’t fly, Hermann and his buddies will instead play video games like Battlefield 2 or Call of Duty. By comparison, they find that flying the recon drone is “kind of like old Atari, pretty basic, point and click.” Looking forward, officers describe unmanned systems as being perhaps more suitable than human-piloted planes for many other roles, including even refueling aircraft, in which a premium is placed on endurance and the ability to fly precisely at a steady speed and level.

The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

by

Sebastian Mallaby

Published 1 Feb 2022

When Stephens scoured the Valley and came up with nothing, his comrades responded with a simple prompt. If no such company exists, start one.[64] Four years later, the resulting unicorn, Anduril, is building a suite of next-generation defense systems. Its Lattice platform combines computer vision, machine learning, and mesh networking to create a picture of a battlefield. Its Ghost 4 sUAS is a military reconnaissance drone. Its solar-powered Sentry Towers have been deployed on the U.S.-Mexico border. In an age when artificial intelligence will overwhelm the war machines of yesteryear, Anduril’s aspiration is to combine the coding virtuosity of a Google with the national-security focus of a Lockheed Martin.

The Rare Metals War

by

Guillaume Pitron

Published 15 Feb 2020

Pax Technica: How the Internet of Things May Set Us Free or Lock Us Up

by

Philip N. Howard

Published 27 Apr 2015

Smashing your opponent’s computers is not just an antipropaganda strategy, and tracking people through their mobile phones is not just a passive surveillance technique. Increasingly, the modern battlefield is not even a physical territory. And it’s not just the front page of the newspaper either. The modern battlefield involves millions of individual instructions designed to hobble an enemy’s computers through cyberwar, long-distance strikes through drones, and coordinated battles that only bots can respond to. The reason that digital technologies are now crucial for the management of conflict and competition is that they respond quickly. Brain scientists find that it takes 650 milliseconds for a chess grandmaster to realize that her king has been put in check after a move.

New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI

by

Frank Pasquale

Published 14 May 2020

v=HipTO_7mUOw; Jessica Cussins, “AI Researchers Create Video to Call for Autonomous Weapons Ban at UN,” Future of Life Institute, November 14, 2017, https://futureoflife.org/2017/11/14/ai-researchers-create-video-call-autonomous-weapons-ban-un/?cn-reloaded=1. 4. Shane Harris, “The Brave New Battlefield,” Defining Ideas, September 19, 2012, http://www.hoover.org/research/brave-new-battlefield; Benjamin Wittes and Gabriella Blum, The Future of Violence- Robots and Germs, Hackers and Drones: Confronting the New Age of Threat (New York: Basic Books, 2015). 5. Gabriella Blum, “Invisible Threats,” Hoover Institution: Emerging Threats, 2012, https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/emergingthreats_blum.pdf. 6. P. W.

Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

by

Parag Khanna

Published 18 Apr 2016

It is too soon to tell whether Africa will pull together or succumb to another round of divide and rule. The answer will reveal itself only by watching the supply chain tug-of-war. FROM SYKES-PICOT TO PAX ARABIA While embedded with U.S. Special Operations Forces in 2007, I witnessed firsthand America’s incredible ability to apply technology to the battlefield. The digital map layered on Iraq’s topography was rich with satellite feeds, drone surveillance, heat maps of local violence, real-time situation reports from troops on the ground, and other forms of human and signals intelligence. With about two hours’ notice, special ops teams could strike anywhere in the country. During the so-called surge, the “op tempo” was relentless, and yet the coalition’s ability to hold Iraq together was fleeting at best.

The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations

by

Daniel Yergin

Published 14 Sep 2020

Looking on are U.S. energy secretary Ernest Moniz, on the left, and, on the right, Ali Akbar Salehi (Ph.D. from MIT), head of Iran’s atomic energy agency. General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Quds (“Jerusalem”) Force, the international arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, pulled the strings in Iraq and masterminded the “axis of resistance” across the Middle East. The battlefield, he said, was “another kind of paradise.” He was killed by an American drone in 2020. Houthi militants in Yemen cheer the launch of a ballistic missile aimed at Saudi Arabia. The Yemen civil war led to a huge humanitarian crisis. A surge in U.S. shale oil—the biggest and fastest growth ever registered in the history of oil production—created a global surplus that set the stage for the 2014–15 oil price collapse.

Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins

by

Andrew Cockburn

Published 10 Mar 2015

The Pentagon Papers, the secret history of the war leaked by Daniel Ellsberg in 1971, contained a detailed account of the original Jason deliberations, including those cerebral ruminations on the relative lethal merits of cluster bombs and other munitions. Amid the general horrors of the war, the specter of an automated battlefield, in which targets were selected and struck by remote control, touched a sensitive public nerve, just as drone attacks unleashed by the Obama administration forty years later ignited similar debate. At scientific conferences in Europe, venerable Nobel Prize winners confronted by angry demonstrators had to be rescued by riot police. Other Jasons received death threats at home.

Who Rules the World?

by

Noam Chomsky

The War Came to Us: Life and Death in Ukraine

by

Christopher Miller

Published 17 Jul 2023

Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel's Targeted Assassinations

by

Ronen Bergman

Published 30 Jan 2018