Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, From the Ancients to Fake News

by

Eric Berkowitz

Published 3 May 2021

Qin kept copies of the books he burned, but those who knew the texts best were not spared: hundreds of scholars were buried alive. From that point forward, anyone who criticized Qin’s regime with examples from the past—or even discussed the ideas in the banned books—was executed along with their relatives. Like most political censorship throughout history, observes the scholar Lois Mai Chan, Qin’s book burning “proved to be, rather than a condemnation, a recognition of the power of knowledge.”3 For Qin, security meant dominance not only of the wheels of state but also of the ideas darting through the minds of the governed. Intellectuals in particular were empowered by the forbidden books, which bred seditious thoughts that challenged the First Emperor’s absolute rule.4 As the twentieth-century Chinese writer Lu Xun observed: The statesman hates the writer because the writer sows the seeds of dissent.

…

Questioning whether the stricken populace—many of whom now sat in judgment on him—could grasp the existence of the very gods who were decimating them in such numbers was an outrage. Protagoras was convicted. According to tradition, his writings were collected and set afire in public. If that indeed happened, it was likely the first book burning in Western history. (His personal fate is unclear. Either he was exiled, or, according to another version of events, he fled Athens before the trial and died in a shipwreck.)24 The destruction, intended to eradicate the texts and ideas they contained, was likely also tied to religious customs.

…

On the contrary, the persecution of genius fosters its influence; foreign tyrants, and all who have imitated their oppression, have merely procured infamy for themselves and glory for their victims.34 With the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BCE, the interests of the state and the head of state merged. As the job of emperor was often risky to one’s life expectancy, speech causing even the most unjustified imperial fear could be framed as treasonous. The earliest examples of Roman book burning concerned the writings and handbooks used by itinerant seers, astrologers, and prophets. The public destruction of these texts, like public executions of criminals, was meant to affirm government power and impart blunt political messages. The job of divining the future (by, for example, analyzing the entrails of animals or evaluating bursts of lightning) and other procedures for taking the gods’ temperature belonged to state-appointed functionaries.

Clock of the Long Now

by

Stewart Brand

Published 1 Jan 1999

Luciano Canfora, The Vanished Library (Berkeley: UC California, 1987), pp. 98-99. :74 A different reason for burning books was originally invented by China’s first great emperor. My best source on Shih huangti’s book burning was one of Time-Life’s excellent Lost Civilizations series, China’s Buried Kingdoms (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life, 1993). The dinner debate is reported on p. 98. :74 The same impulse inspired Hitler’s book-burning ceremonies of May 1933. William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960), pp. 230, 241. :74 The American Revolution of 1776, by contrast, was highly conservative.

…

Instead, his ten-thousand-generation dynasty ended shortly after his death, having lasted fifteen years (221-206 B.C.E.). The Confucian Han dynasty that followed vilified Shih Huang-ti, and he remains largely a villain in Chinese history. Yet this did not prevent Mao Tse-tung from attempting a similar erasure with his Cultural Revolution in 1966, to disastrous effect. The same impulse inspired Hitler’s book-burning ceremonies of May 1933. “The German form of life is definitely determined for the next thousand years,” he declared. “There will be no other revolution in Germany for the next thousand years.” In a square by the University of Berlin twenty thousand books were burned. Other cities did the same.

…

The BBC, on a housecleaning binge a few years back, tossed out some of its video archives considered trivial and has been gnashing its teeth over that cultural loss ever since. The largest and heaviest book in the world is inscribed on 14,300 large stone tablets concealed in caves near the Yunju monastery in Beijing Province, China. In a time of book burnings, 00605 C.E., a monk set about preserving the Buddhist scriptures on stone. The work continued for a thousand years, and then the entire trove was hidden in 01644 C.E. The hoard is indeed valuable for studying the history of Buddhist thought, but probably we would value the stones more if the monks had simply recorded the weather and what they were eating.

The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World

by

Catherine Nixey

Published 20 Sep 2017

In Alexandria, Antioch and Rome, bonfires of books blazed and Christian officials looked on in satisfaction. Book-burning was approved of, even recommended by, Church authorities. ‘Search out the books of the heretics . . . in every place,’ advised the fifth-century Syrian bishop Rabbula, and ‘wherever you can, either bring them to us or burn them in the fire.’2 In Egypt at around the same time, a fearsome monk and saint named Shenoute entered the house of a man suspected of being a pagan and removed all his books.3 The Christian habit of book-burning went on to enjoy a long history. A millennium later, the Italian preacher Savonarola wanted the works of the Latin love poets Catullus, Tibullus and Ovid to be banned while another preacher said that all of these ‘shameful books’ should be let go, ‘because if you are Christians you are obliged to burn them’.4 Books had been burned under non-Christian emperors – the controlling Augustus alone had ordered the burning of over two thousand books of prophetic writings, and had exiled the misbehaving poet Ovid – but now it grew in scope and ambition.

…

As Samuel Johnson would put it, pithy as ever: ‘The heathens were easily converted, because they had nothing to give up.’16 He was wrong. Many converted happily to Christianity, it is true. But many did not. Many Romans and Greeks did not smile as they saw their religious liberties removed, their books burned, their temples destroyed and their ancient statues shattered by thugs with hammers. This book tells their story; it is a book that unashamedly mourns the largest destruction of art that human history had ever seen. It is a book about the tragedies behind the ‘triumph’ of Christianity. A note on vocabulary: I have tried to avoid using the word ‘pagan’ throughout, except when conveying the thoughts or deeds of a Christian protagonist.

…

After hearing this, Amantius was overcome by zeal and promptly ‘conducted an inquisition [and] found that the majority of the first citizens of the city and many of its inhabitants had been involved in paganism, Manicheaism, astrology, [Epicureanism], and other gruesome heresies. These he had detained, thrown in prison, and having brought together all of their books, which were a great many, he had these burnt in the middle of the stadium.’13 What did the books burned on such occasions really contain? Doubtless some did contain ‘magic’ – such practices were popular prior to Christianity and certainly didn’t disappear with its arrival. But they were not all. The list given in the life of St Simeon clearly refers to the destruction of books of Epicureanism, the philosophy that advocated the theory of atomism.

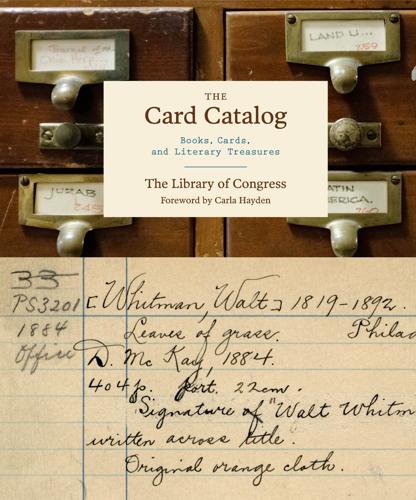

The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures

by

Library Of Congress

and

Carla Hayden

Published 3 Apr 2017

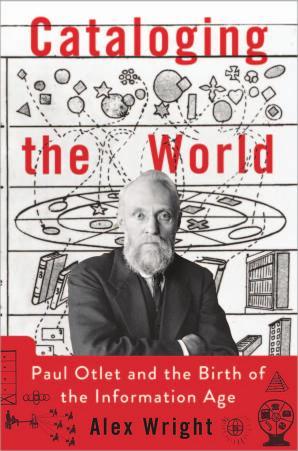

Classification: LCC Z733.U6 C36 2017 | DDC 025.3/13—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016017476 Design by Brooke Johnson Typeset in Poynter Old Style, Benton Sans, and Prestige Elite Front of case: Photograph by Shawn Miller Chronicle Books LLC 680 Second Street San Francisco, California 94107 www.chroniclebooks.com Contents 7 Foreword 9 Introduction 11 Chapter 1 Origins of the Card Catalog 12 Catalogs of Clay 12 The Library of Alexandria’s Great Catalog—The Pinakes 15 Catalogs of the Far and Middle East 17 Medieval Libraries, Movable Type, and Gessner’s Scheme 21 Vive La Revolution . . . and Card Catalogs 45 Chapter 2 The Enlightened Catalog 46 Eleven Hair Trunks and A Case for the Maps 48 The War of 1812, A Book Burning, and A New Library 81 Chapter 3 Constructing a Catalog 82 The Card Catalog Takes Shape 83 The Library Bureau 101 Chapter 4 The Nation’s Library and Catalog 102 Chaos in the Capitol 104 Ten First Street 106 Facing Congress 108 Starting From Scratch 110 Universal in Scope, National in Service 145 Chapter 5 The Rise and Fall of the Card Catalog 146 An Egalitarian Effort 148 Drowning in Cards 151 The March to Marc 154 Cards as Art Cutting the Gordian Knot 220 Acknowledgments 221 Select Bibliography 222 Image Credits 223 Index People working at desks in the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress, circa 1940.

…

It may seem peculiar that book prices were listed, but because the Library represented such a significant investment for the newly established country, Congressmen could only check books out by signing a note promising to return them—or pay for them in full. Letter from Cadeil & Davies, London booksellers, addressed to W. Bingham, esq., and Robert Wain, esq., 1800. An invoice for the first consignment of books that the Library of Congress purchased with its $5,000 appropriation, approved on April 24, 1800. THE WAR OF 1812, A BOOK BURNING, AND A NEW LIBRARY As the British fleet sailed up the Pawtuxet River on August 22, 1814, to attack a vulnerable Washington, D.C., an intrepid J. T. Frost frantically searched the deserted capital for a carriage he could use to secure the Library’s collection, which now numbered some 3,000 volumes.

China: A History

by

John Keay

Published 5 Oct 2009

The [only] books to be exempted are those on medicine, divination, agriculture and forestry.16 The emperor concurred; and so began the great bamboo-book-burning of 213 BC. It was followed, according to later sources, by a purge in which some 460 scholars were either executed or buried alive. A far-fetched explanation offered for this second assault may simply disguise the need to halt any oral, as well as written, transmission of the texts. To a people who distinguished themselves from others on the basis of their historical awareness and essentially literary culture, the book-burning and the persecution of scholars were devastating blows. Popular sentiment would never forget them, scholarship never forgive them.

…

Within the chamber, there may still reign that minutely regulated peace and order on which the First Emperor so prided himself in his inscriptions; but without, all semblance of decorum had been shattered almost before he was laid to rest. 4 HAN ASCENDANT 210–141 BC QIN IMPLODES NEARLY ALL THAT IS KNOWN OF the First Emperor and his book-burning chancellor comes from a book. In a culture as literary and historically minded as China’s, biblioclasts needed to beware; books had a way of biting back, and sure enough, both emperor and chancellor would be badly bitten. Ostensibly Sima Qian’s Shiji, one of the most ambitious histories ever written, was a direct response to the First Emperor’s assault on scholarship.

…

According to Sima Qian, at the first hint of indisposition Meng Yi, the chief minister and brother of the wall-building Meng Tian, had been sent post-haste from Shandong to organise ‘sacrifices to the mountains and rivers’, presumably for the emperor’s recovery. That left the imperial cavalcade in the charge of Li Si, the book-burning chancellor, assisted by Zhao Gao, a eunuch who held the important post of chief of the imperial carriages, plus Prince Huhai, the emperor’s youngest son. When the emperor expired just days after Meng Yi’s departure, Li Si proved uncharacteristically indecisive. Instead it was Zhao Gao who took the initiative.

The Library: A Fragile History

by

Arthur Der Weduwen

and

Andrew Pettegree

Published 14 Oct 2021

One clergyman in Cartmel, Lancashire, noted dryly in a memorandum that ‘I burned all the books’.25 This wave of destruction may have encompassed many more books than intended: it is understandable that not everyone tasked with book burning could tell the difference between secular manuscripts of historical importance and works of Catholic theology. Many church libraries suffered multiple book burnings. To propagate the Reformation, royal injunctions in the 1530s and 1540s had specified that each parish was to acquire at least one Protestant Bible, as well as the Paraphrases of Erasmus. These, and other Protestant books bought for parish churches, were prime targets when Edward VI was succeeded by his Catholic half-sister, Queen Mary, in 1553.

…

The first Roman index also included a category of heretical printers, sixty-one in all, whose entire output, regardless of content, was suspect. Good Christians were supposed to surrender copies of these books from their libraries, while the production, sale and ownership of all texts listed in the index was strictly forbidden. Publication of the first papal index was accompanied by substantial book burning, but mostly in Rome itself. Many secular authorities elsewhere in Italy were hesitant to put the full force of the index into effect. In Florence, Duke Cosimo de’ Medici forbade the monks of San Marco from burning any books in their library which his predecessors had donated. Future indices relaxed the most sweeping prohibitions and placed more emphasis on the capacity of local inquisitors and bishops to grant exemptions for certain individuals to own dangerous books.

…

These libraries functioned as archival storehouses, as repositories of knowledge and as meeting places. They gave shape to competing churches and fostered the spiritual health of their members. To destroy these institutions was to take one further step towards restoring unity in Christendom, the ultimate goal of every denomination, yet not all destruction needed to be as overt as book burnings. Locking up a library, reducing its contents to waste paper, or expurgating texts: these were the varied tools used to limit access to undesirable literature. In time, the missionary zeal of the separated Protestant and Catholic churches would inaugurate a new age of library building, with impressive results, but in the first two generations of the Reformation this was still some way in the future.

The Book: A Cover-To-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time

by

Keith Houston

Published 21 Aug 2016

Inroads,” Reuters, October 8, 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/08/us-usa-china-huawei-zte-idUSBRE8960NH20121008. 29. von Hagen, “Paper and Civilization,” 313; Leor Halevi, “Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper,” Speculum 83, no. 4 (2008): 917, doi:10.1017/S0038713400017073. 30. Hunter, Papermaking, 473. 31. “Koran 29:46 (Yusuf Ali Version),” n.d.; Hans J. Hillerbrand, “On Book Burnings and Book Burners: Reflections on the Power (and Powerlessness) of Ideas,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 74, no. 3 (2006): 602–3, doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfj117; “Reconquista.” 32. Robert I. Burns, “The Paper Revolution in Europe: Crusader Valencia’s Paper Industry: A Technological and Behavioral Breakthrough,” Pacific Historical Review 50, no. 1 (1981): 1–30; “Alfonso X (king of Castile and Leon),” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed December 18, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/14725/Alfonso-X. 33.

…

Chester, 265 Belgium, 35 Bembo, Bernardo, 320 Bembo (typeface), 320 Benedict, Saint, 165 Benedict VIII, Pope, 28 Berbers, 53 Bewick, Thomas, 227 Bible, 106 Gutenberg edition of, 109, 114–23, 124–25, 145, 199, 229, 314, 316–17, 318, 324 Biblia pauperum (Pfister), 200, 201 bibliographies, 329 biblion (scroll), 250 Bibliotheca historica (Diodorus), 89 bibliotheke, 252 Bibliothèque nationale de France, 245, 289 biblos (papyrus), 250 Billings, John Shaw, 146–47 Birds of America, The (Audubon), 213, 215–16, 217, 218, 225–26, 229 Birth of the Codex, The (Roberts and Skeat), 277 Bi Sheng, 110–11, 112 Black, William, 308 Black Death, 63 blackletter (Gothic textura), 99, 107, 123, 318 black tigers (hei laohu), 180 blind tooling, 303–4, 331 blockbooks, 199 Boas, Franz, 261 boats, of papyrus, 6, 7 Bologna, Italy, 323 Boner, Ulrich, 199 Boniface, Saint, 297–98 bookbinding, 283–309, 299, 303 backing process in, 301–2, 308 case binding, 308, 331 Coptic stitching in, 292–94, 293, 300–301, 302–3, 306 covers in, see covers double-cord, 296–98, 297, 330–31 dust jackets and, 304 endpapers in, 300, 308 glued, 308–9, 310, 331 headbands (endbands) in, 300–301 innovations in, 299–306, 308–9, 310 Islamic, 302–3 mechanization of, 308, 310 multiple gatherings in, 290–95 Nag Hammadi codices and, 279–81, 282 paperbacks, 309 paper sizes and, 323–28 perfect binding, 309 Ragyndrudis Codex and, 296–97 St. Cuthbert Gospel and, 284–88, 291–93, 294, 295–96, 298, 300 single gatherings in, 288–89 book industry, growth of, 69–70 book louse, 51n–52n Book of Agriculture (Wang Zhen), 111 Book of Durrow, 161 Book of Kells, 161–64, 163, 169–70 bookplate, i books: burning of, 56, 58 interdependence of paper and, 35–36, 50 mass deacidification of, 71–72 mass printing of, 128 paged, see codex, codices books, modern: trimmed edges of, 281 Books of Hours, 174 Books of the Dead, 20, 157–58, 159, 245, 248–49 Botticelli, Sandro, 208 Bouchard, Pierre, 90 Bouland, Ludovic, 305–6, 307 British Library, 28, 72, 286 British Museum, 90, 249 Bruce, David, 134–35 brushes, 84, 85, 88, 94, 180, 186, 242 Brussels, 35, 290 Brussels Madonna, 193 bubonic plague, 102, 105 Buchdrucker, Der (The Printer; Amman), 119 Buddhism: in China, 180–81, 183–84 in Japan, 181–83 bullae, 80, 82 bullet, 14 Bullock, William, 135 Burgkmair, Hans, 197–98, 197 burins, 206–7 Burke, William, 304–5 “Burke’s Skin Pocket Book,” 305 Buxheim Saint Christopher, 194, 303 Caesar, Julius, 256 memorandum books of, 273–74 Cai Lun, 11, 39–49, 45, 68, 83, 177, 178 and invention of paper, 41–49, 50–51 suicide of, 48 Cairo Museum, 20 Çakir, Mehmet, 256 calami (pens), 94 calfskin, xvii, 31, 123, 304 calligraphy, 113 Cambridge University, 62 Canaan, Canaanites, 92–93 caoutchouc (rubber), 308–9, 310 caption, 5 carbon, in ink, 85, 95, 97, 122, 186 Carchemish, 20 Carpi, Italy, 316 cartonnage, 66, 282 case binding, 308, 331 Castaldi, Panfilo, 190, 191 Cathach, An, 160–61 Cathars, 59, 60 Catherine of Siena, Saint, 193 Catholic Church, woodblock printing and, 192–93 Census, US, 145–46, 152 chalk, 74 Champollion, Jean-François, 91 Chang’an, China, 181, 187 chapter number, 3 chapter title, 3 Charlemagne, 53, 165–66, 299, 318 Charles I, king of England, 323 Charles Martel, 53 chase, 121, 128, 200 Chelsea Manufacturing Company, 67 Chen Sheng, 38 chiaroscuro, 197–98, 197 Chicago Tribune, 144 China: Buddhism in, 180–81, 183–84 copper coinage in, 176, 187 ink in, 112–13 invention of paper in, 36–37, 41–49, 43, 44, 45, 50–51, 68, 113, 177, 178–79 Japanese emulation of, 181 Marco Polo in, 176–77 movable type and, 109–14, 186 orihons in, 266, 267, 269–70 paper money invented in, 176–77, 180, 187, 188, 189, 191 printing invented in, 177–81, 183–86 rubbings in, 179–80 woodblock printing in, 183–86 writing surfaces used in, 37–38 chi rho, 163 chlorine, in papermaking, 70 Christianity, Christians, 271 book burning by, 56, 58 in Ireland, 156–57 papyrus linked to heathenism by, 287 parchment adopted by, 27–28, 56 spread of, 164–65 Christopher, Saint, 192, 193 chromolithograph, 226 chu (Broussonetia papyrifera; paper mulberry), 47, 49 in papermaking, 41–42, 46, 68 Church, William, 139, 141 cinnabar, 172 clay tablets, xvn, xvi, 79–80 Clemens, Samuel (Mark Twain), 66, 151 Paige Compositor and, 136–38, 138, 148 Cleopatra VII, pharaoh, 88 Clephane, James O., 140–41 Clymer, George E., 131 codex, codices, xv, xvn–xvin, 260, 297 binding of, see bookbinding changing market for, 310–11 collections of correspondence as origin of, 270–71 deckle-edged, 314 etymology of, 294–95 Golden Ratio and, 324 multiple-gathered, 311–12 orihons and, 266 of paper, 302–3, 312 of papyrus, 261–65, 272, 276–82, 288–91, 302–3, 311, 312–13 of parchment, 272–77, 284–88, 291–93, 311–12 in Roman Egypt, 261–65, 270 vs. scrolls, efficiency of, 253–54 single-gathered, 311 sizes of, 311–28, 314, 331 unopened edges in, 313–14 Codex Leicester, 284 Codex Peresianus, 268 codicologists, 277, 281–82, 312, 318 Coele-Syria, 21, 23 coffee-table books, xv colophons, 320, 329–31 Columba, Saint, 161, 164 Columbia Jay, 217 Columbian press, 130, 131 Committee on the Simplification of Paper Sizes, 326–27 composing stick, 120–21, 135, 136 compositors, 119–21, 120, 135 computers, xv and lithography, 236–37 typesetting and, 152 Confucianism, 185 Conrad von der Rosen, 211, 212 Constantinople, 155 contents page, xi copper, 118, 122 copper acetate, 259 copperas (ferrous sulfate), 97, 100–101 copperplate printing, xvii aquatint process and, 216, 217, 218, 230 engraving and, 203–5, 206, 207–10, 207, 215–16, 220 etching and, 211–13, 216, 230 Mansion and, 205 copper sulfate, 97 Coptic language, 91 Coptic Museum, Cairo, 277, 279, 289 Coptic stitching, 292–94, 293, 296, 300–301, 302–3, 306 Copts, 278, 294, 302–3 copyright, xvi copyright page, 73–74 correctors, 170 correspondence, collections of, as origin of codices, 270–71 cotton, 36, 41, 63 couching, in papermaking, 44, 46, 61, 64 counterpunch, 115n covers, 295–96, 331 gold leaf on, 304 of human skin, 304–5 leather, 303–4 pasteboard, 302–3 reused leaves in, 302 in St.

…

Cuthbert Gospel and, 284–88, 291–93, 294, 295–96, 298, 300 single gatherings in, 288–89 book industry, growth of, 69–70 book louse, 51n–52n Book of Agriculture (Wang Zhen), 111 Book of Durrow, 161 Book of Kells, 161–64, 163, 169–70 bookplate, i books: burning of, 56, 58 interdependence of paper and, 35–36, 50 mass deacidification of, 71–72 mass printing of, 128 paged, see codex, codices books, modern: trimmed edges of, 281 Books of Hours, 174 Books of the Dead, 20, 157–58, 159, 245, 248–49 Botticelli, Sandro, 208 Bouchard, Pierre, 90 Bouland, Ludovic, 305–6, 307 British Library, 28, 72, 286 British Museum, 90, 249 Bruce, David, 134–35 brushes, 84, 85, 88, 94, 180, 186, 242 Brussels, 35, 290 Brussels Madonna, 193 bubonic plague, 102, 105 Buchdrucker, Der (The Printer; Amman), 119 Buddhism: in China, 180–81, 183–84 in Japan, 181–83 bullae, 80, 82 bullet, 14 Bullock, William, 135 Burgkmair, Hans, 197–98, 197 burins, 206–7 Burke, William, 304–5 “Burke’s Skin Pocket Book,” 305 Buxheim Saint Christopher, 194, 303 Caesar, Julius, 256 memorandum books of, 273–74 Cai Lun, 11, 39–49, 45, 68, 83, 177, 178 and invention of paper, 41–49, 50–51 suicide of, 48 Cairo Museum, 20 Çakir, Mehmet, 256 calami (pens), 94 calfskin, xvii, 31, 123, 304 calligraphy, 113 Cambridge University, 62 Canaan, Canaanites, 92–93 caoutchouc (rubber), 308–9, 310 caption, 5 carbon, in ink, 85, 95, 97, 122, 186 Carchemish, 20 Carpi, Italy, 316 cartonnage, 66, 282 case binding, 308, 331 Castaldi, Panfilo, 190, 191 Cathach, An, 160–61 Cathars, 59, 60 Catherine of Siena, Saint, 193 Catholic Church, woodblock printing and, 192–93 Census, US, 145–46, 152 chalk, 74 Champollion, Jean-François, 91 Chang’an, China, 181, 187 chapter number, 3 chapter title, 3 Charlemagne, 53, 165–66, 299, 318 Charles I, king of England, 323 Charles Martel, 53 chase, 121, 128, 200 Chelsea Manufacturing Company, 67 Chen Sheng, 38 chiaroscuro, 197–98, 197 Chicago Tribune, 144 China: Buddhism in, 180–81, 183–84 copper coinage in, 176, 187 ink in, 112–13 invention of paper in, 36–37, 41–49, 43, 44, 45, 50–51, 68, 113, 177, 178–79 Japanese emulation of, 181 Marco Polo in, 176–77 movable type and, 109–14, 186 orihons in, 266, 267, 269–70 paper money invented in, 176–77, 180, 187, 188, 189, 191 printing invented in, 177–81, 183–86 rubbings in, 179–80 woodblock printing in, 183–86 writing surfaces used in, 37–38 chi rho, 163 chlorine, in papermaking, 70 Christianity, Christians, 271 book burning by, 56, 58 in Ireland, 156–57 papyrus linked to heathenism by, 287 parchment adopted by, 27–28, 56 spread of, 164–65 Christopher, Saint, 192, 193 chromolithograph, 226 chu (Broussonetia papyrifera; paper mulberry), 47, 49 in papermaking, 41–42, 46, 68 Church, William, 139, 141 cinnabar, 172 clay tablets, xvn, xvi, 79–80 Clemens, Samuel (Mark Twain), 66, 151 Paige Compositor and, 136–38, 138, 148 Cleopatra VII, pharaoh, 88 Clephane, James O., 140–41 Clymer, George E., 131 codex, codices, xv, xvn–xvin, 260, 297 binding of, see bookbinding changing market for, 310–11 collections of correspondence as origin of, 270–71 deckle-edged, 314 etymology of, 294–95 Golden Ratio and, 324 multiple-gathered, 311–12 orihons and, 266 of paper, 302–3, 312 of papyrus, 261–65, 272, 276–82, 288–91, 302–3, 311, 312–13 of parchment, 272–77, 284–88, 291–93, 311–12 in Roman Egypt, 261–65, 270 vs. scrolls, efficiency of, 253–54 single-gathered, 311 sizes of, 311–28, 314, 331 unopened edges in, 313–14 Codex Leicester, 284 Codex Peresianus, 268 codicologists, 277, 281–82, 312, 318 Coele-Syria, 21, 23 coffee-table books, xv colophons, 320, 329–31 Columba, Saint, 161, 164 Columbia Jay, 217 Columbian press, 130, 131 Committee on the Simplification of Paper Sizes, 326–27 composing stick, 120–21, 135, 136 compositors, 119–21, 120, 135 computers, xv and lithography, 236–37 typesetting and, 152 Confucianism, 185 Conrad von der Rosen, 211, 212 Constantinople, 155 contents page, xi copper, 118, 122 copper acetate, 259 copperas (ferrous sulfate), 97, 100–101 copperplate printing, xvii aquatint process and, 216, 217, 218, 230 engraving and, 203–5, 206, 207–10, 207, 215–16, 220 etching and, 211–13, 216, 230 Mansion and, 205 copper sulfate, 97 Coptic language, 91 Coptic Museum, Cairo, 277, 279, 289 Coptic stitching, 292–94, 293, 296, 300–301, 302–3, 306 Copts, 278, 294, 302–3 copyright, xvi copyright page, 73–74 correctors, 170 correspondence, collections of, as origin of codices, 270–71 cotton, 36, 41, 63 couching, in papermaking, 44, 46, 61, 64 counterpunch, 115n covers, 295–96, 331 gold leaf on, 304 of human skin, 304–5 leather, 303–4 pasteboard, 302–3 reused leaves in, 302 in St.

Antwerp: The Glory Years

by

Michael Pye

Published 4 Aug 2021

Aelst, Pieter Coecke van, 164 Aemilianus, Roman Emperor, 39 Aertsen, Pieter, 155–7, 165–6, 172–3, 174 Africa Africans living in Antwerp, 99 Charles V besieges Tunis (1535), 69 gold from, 7, 15, 97, 98, 125 ships from, 2, 32 and slave trade, 7, 8, 15, 34, 98–9 spices/plants from, 33, 67, 69, 97 trade routes south across the Sahel, 98, 101 Alba, Duke of, 3, 182, 186, 191, 199, 200, 211, 217 bronze effigy of, 201, 205 calls Antwerp ‘Babylon,’ 12, 30, 150 campaign against Antwerp’s past, 201, 205 Alberti, Leon Battista, De re aedificatoria, 200 alchemy and magic, 61–3, 68 alcohol, 4, 115, 210 beer business, 162, 170–2, 205 wine trade, 31, 74, 83, 169, 215 Alexandria, 101 the Americas, 1–2, 8, 43, 69, 152, 174, 187 Amsterdam, 9, 19, 58, 63, 171, 173–4, 184 ideas move north from Antwerp, 8, 158, 161, 216–17 Anabaptists, 149, 188, 211, 217 Ancona, 93, 94, 100 animals, domestic, 2, 17, 66, 110, 140, 155, 157 Anjou, Duke of, 180, 207–9, 212 Annabon, 102 Antwerp Africans living in, 99 book burning in, 48, 49, 50 as celebrity, 3, 4, 7–8 as centre of news and rumour, 4, 7, 54–9, 82–3, 175 city as idea, 5, 6–7, 8, 21, 25, 26, 27–31, 34–41 count of Flanders seizes (1356), 32–3 and Duke of Anjou, 180, 207–9, 212 English connection, 15, 31, 32, 33–4, 42, 45–6, 51–2, 53, 150, 208 Fugger newsletters in, 55–6 growth in late medieval period, 1–2, 4, 7, 14–15 iconoclasm (1566), 6, 183–4, 186, 189, 190 the Joyous Entry (1549), 15, 18, 34, 82, 148–54, 180, 184, 207 legends/fantasy history, 6, 28, 30–1, 35–8 and the Ottoman Turks, 101, 211–13, 216 and Ottoman-Hapsburg rivalry, 100, 115 pragmatic tolerance in, 4–5, 78, 100, 174, 184, 188, 189, 204 privileges from Emperor, 16, 148, 149 Protestant ‘exodus’ (from 1567), 191, 205 sheltered anchorage at, 2 and slave trade, 7, 8, 15, 34, 98–9 stories of street life, 40, 89–92, 94 two Antwerps in Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 199, 208 van Rossum’s siege (1542), 13–14, 23–5, 39, 45, 167–8 violence of mutineers in Antwerp (1576), 12, 14, 39, 203–5 see also built environment/urban development of Antwerp; foreign merchants in Antwerp; governance of Antwerp; historical identity of Antwerp; social structure of Antwerp Antwerp, streets/districts Arenbergstraat, 18 Augustijnenstraat, 72 Borzestraat, 118, 159 Camerstraat, 59 Groenplaats, 22 Grote Markt, 9, 14, 18, 22, 43, 82, 118, 151–2, 153–4, 172, 204 Heilige Geeststraat, 8–9, 162, 163 Hochstetterstraat, 59 Hofstraat, 58 Hoogstraat, 58 Huidevetterstraat, 159 Ijzerenbrug, 59 Jodenstraat, 159 the Kipdorp, 25, 27, 191 Koningstraat, 158–9 Lepelstraat area, 89–90 Lombardstraat, 159 Maalderijstraat, 58 the Meir (market), 18, 118, 164 Nieuwstad (new town), 66, 169, 171, 172 Noordstraat., 159 Ossenmarkt, 155, 158 Sint Katelijnevest, 23 Twaalfmaandenstraat, 57, 117–18, 145 Vrijdagmarkt, 8, 58, 163, 181 Wolstraat, 58, 119 Aquinas, Thomas, 128 archery guilds, 164–5, 172 architecture baroque buildings of Counter-Reformation, 5, 9, 214–15, 216 Hanseatic style, 135 military, 61, 167–8, 199–201, 214 the new Beurs building, 16, 117–20, 129, 131, 213 of the new weigh house, 161–2 pentagon forts, 200 ready-made details, 134 Vleeshuis (butchers guildhall), 157, 164 archives and records, 11–12 losses in 1576 fire, 12, 14, 39, 205 vonnisboeken of the griffiers, 38–40 Ariosto, Ludovico, Orlando Furioso, 178 Aristotle, 35, 200 Arnolfini, Iacopo, 125 art Aertsen’s The Meat Stall, 155–7, 165–6, 172–3 Antwerp as school of style, 134–7, 138, 139 Antwerp market, 132–4, 135–7, 139 art dealers, 131–2, 133 artists’ market at Beurs (schilderspand), 131, 132 artists’ supplies, 60–1, 131 brand names based on artists’ reputations, 135–7, 155 commodification of, 5, 130, 131–9 of Counter-Reformation, 214–15, 216 Dürer in Antwerp, 60–1, 98, 131 female painters, 77 Greek notion of rhopography, 156 Guild of St Luke, 77, 132, 177 Italian tradition, 137–8, 139, 196 Italian versus Flemish disputes, 137–8 mannerists, 137 as mark of status, 10–11, 27–8, 44, 132–3 Netherlandish, 95–6, 133–7, 138, 139, 164, 196 old art market burned down, 204 the painter as economic asset, 138–9 production methods, 135–7, 155 ready-made pillars and balconies, 133–4 smashing of altar art, 206 and storytelling, 155–6 tapestry-makers, 164–5, 170 travelling craftsmen, 134–6 Ascham, Roger, 44–5, 197 de Assa, Fernando, 123 Babylon, 12, 28, 30, 36–8, 150 Back, Frans, 90 Badoaro, Andrea, 210 Badoero, Federico, 3, 4 Bandello, Matteo, Bishop of Agen, 7, 83–5, 89 Barlandus, Adrianus, 35 Baruzeel, Jan, 131–2 Basel, 38, 43, 44, 55, 93 Baudeloo, monks of, 159 Bayfield, Richard, 47 beer business, 162, 170–2, 205 Beham, Sebald, 28 bells, great, 13–15, 16–17, 24, 119, 203–4 Benoist, René, 180 Berchem, Arnold van, 20 Bergen, Gérard van, De pestis praeservatione libellus, 64 Bergen op Zoom, 32, 34 de Berlaimont, Noël, 80, 81 Bertels, Bartholomeus, 59 Beuckelaer, Joachim, 156 the Beurs (Exchange) and African trade, 101 artists’ market at (schilderspand), 131, 132 bell towers, 16, 118 burns down (1584), 213 in early seventeenth-century, 218 and Guicciardini, 118, 119–20, 128–9, 180 at heart of new financialization, 128–9 imitation of in Northern Europe, 129, 134, 213 new building, 16, 23, 30, 34, 117–22, 129, 131, 160, 165, 216 old building, 54, 59, 117, 118 and plague regulations, 65 printed news-sheets, 57–8 Beyerlinck, Ruth, 73–4 the Bible Calvinist Geneva version, 180 Coverdale’s Bible in English, 45 dancing in, 142 in English, 7, 45, 46–52, 60 Hebrew, 60, 179 Plantin’s Polyglot Bible, 60, 174–5, 179, 180, 185, 202 Tyndale’s Bible in English, 47–52 Bijns, Anna, 78 Binck, Jacob, 134 Boendale, Jan van, 73 Boethius, 6 Boisot, Dr, 111–12 Bomberg, Daniel, 180 Bomberghen, Cornelis van, 181 Bonrizzo, Luigi, 210 books/literature book burning, 48, 49, 50 books of maps, 192, 195, 198–9 Chambers of Rhetoric (De Bloeyende Wijngaerd), 72, 78, 189, 216 Chronicle of Brabant, 35 as contraband, 47 esoteric/mystical texts, 8, 61–3, 177 female writers, 78 Frankfurt Fairs, 65, 175, 177, 179, 181, 192, 193–4 Index of Forbidden Books, 63 medical, 60, 63–4, 68, 70–1, 179 of Ortelius, 6–7, 45, 176, 179–80, 193, 197, 198, 205, 218 of Peter Martyr, 188 religious exports to England, 7, 46–7, 48–50, 60 schoolbooks, 72, 75–6, 81, 141 smuggling of, 47 tafelspelen (plays), 29 to teach languages, 79–81 Turchi’s chair in, 84 Wickram’s depictions of Antwerp, 7, 89, 91–2, 94 work of Bandello, 83–5, 89 see also publishing and printing Borde, François de la (Maître Jacques), 54 Borgerhout, botanical garden, 69 Bosch, Hieronymus, 22, 95–6 Brabant alliance with Holland and Zeeland (1576), 205 Marino Cavalli on cities of, 2 and English wool, 15, 31, 32, 33–4, 42, 45–6 gardens of, 67–8, 69–71, 87 move to the local in history, 34–5 music of, 140–1, 142, 143–7 privileges to foreign merchants, 32, 51–2, 53 trade fairs, 2, 4, 15, 32, 58 see also Antwerp Brabant, Dukedom of, 16, 35 Brabo (Roman hero), 30, 31 Braun, Georg, 198 Brazil, 1–2, 102 breweries, 171–2, 205 brickworks, 167 Bruegel, Jan, 215 Bruegel, Pieter, 27, 28, 132, 157, 191, 192, 196 The Months, 27–8 The Tower of Babel (first version), 28, 36–7 The Tower of Babel (second version), 37 Bruges conflict with Maximilian, 33 Huis Craenenburg, 33 loss of business to Antwerp, 2, 15, 31–4, 42, 84, 97 and the Medici, 31 as old financial hub, 31, 32, 33 Portuguese feitoria in, 97 Zwin silts up, 33 Brussels, 2, 36, 37, 164, 187 Bruto, Giovanni Michele, 178 Budé, Guillaume, 44 built environment/urban development of Antwerp absence of documents/records, 11, 12 baroque buildings of Counter-Reformation, 5, 9, 214–15, 216 bricks, 26, 61, 161, 162, 167, 169 building regulations, 22–3, 25–6 buying and selling of property/land, 158–60 and Calvinist regime, 23, 66, 205, 206 Cammerport bridge, 63 canal building, 169, 170 civic/municipal buildings, 12, 14, 18, 34, 117, 135 clayfields of Hemiksem, 167 Croneburge tower, 205 fire regulations and risk of wooden buildings, 22–3 geography of trade/markets, 58–9, 63, 117–19 Golden Angel house, 63 great citadel, 199–200, 203, 205, 208, 214 high towers in merchants’ houses, 9, 59, 117 Houte Eeckhof (civic warehouse), 160, 161 hovenkwartier (district of courtyards), 163 new Beurs as civic monument, 117 old art market (pand), 204 open spaces, 18, 26, 161–2, 163 Otto II’s castle, 31 quality of streets/roadways, 18, 163 rules on animals, 17 Schoonbeke’s reshaping of city, 158–65, 167, 169–70, 171–2 streets of old city, 9, 17–18, 22–3, 26, 163 trade as remaking city’s space, 29 Vleeshuis (butchers guildhall), 157, 164 weigh house, 120–1, 160, 161–2, 172–3 see also Antwerp, streets/districts; the Beurs (Exchange); Church of Our Lady; city walls (mediaeval defences); housing Bullinger, Heinrich, 55, 184, 186–7 Burghley House, 134 Burgundy, 32, 33–4, 207 But, Hubrecht de, 159 Calvinism and Antwerp’s merchants, 149 and Dutch revolt, 151, 205–6 ‘hedge preachers,’ 189 heresy as discreet in Antwerp, 184–6 iconoclasm, 183–4, 186, 189, 190 as menace to tolerance, 174, 183–4, 189 move north after fall of Antwerp (1585), 199, 214 as orderly and organized, 186 and Christophe Plantin, 174, 175, 180, 181, 182 printed works, 175, 180, 181, 182 regime in Antwerp (1577-85), 6, 9, 14, 15, 16, 23, 66, 74, 199, 205–6, 214 sale of Catholic artefacts, 206 salonpredikaties, 185 and Scribanius, 216 smashing of altar art, 206 and teaching of French, 75 William’s attempts at compromise, 190 canals, 8, 17, 18, 66, 158, 169, 170, 204 Cardano, Girolamo, 7, 84 Carion, Jean, Chronicles, 84 Carleton, Sir Dudley, 218 Carmelite Church of St John, 159, 164 Carneiro, Manoel, 108 Carolus bell, 13–14, 15, 24, 119, 203–4 cartography, 45, 60, 192–3, 196–7 Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Braun and Hogenberg), 198–9, 208 see also Ortelius, Abraham Castillo, Canon, 183–4, 189–90 Catarina, Queen of Portugal, 105 Catholicism Antwerp offered a bishop (1563), 15–16, 186 banned in Antwerp (1581), 206 and Anna Bijns, 78 Calvinism as formidable opponent, 186 Charles V and Lutherans, 52–3, 55, 149–50 clergy in Antwerp, 78, 175, 179, 183–4, 186, 199 Counter-Reformation, 5, 9, 201–3, 214–15, 216 in England, 7, 46–7, 187 and events of 1566 in Antwerp, 183–4, 186, 188–9 idea of the Eucharist, 188 imposed on Antwerp (after 1585), 9, 14, 214 the Jesuits, 7, 47, 79, 179, 211, 215–16 as menace to tolerance, 174, 184, 189, 190–1 the new breviary (1568), 201–3 and Christophe Plantin, 181–2, 185, 202–3 printed works, 7, 175, 201–3 procession of Our Lady through streets, 25 response to iconoclasm, 186, 189, 190–1 Table of the Holy Ghost, 10 see also Inquisition Cavalli, Marino, 2–3 Çayas, Gabriel de, 182, 202 Cecil, William, 61–2, 134 Chambers of Rhetoric (De Bloeyende Wijngaerd), 72, 78, 189, 216 Charles V, Emperor artistic depictions of, 11 the ‘bloody edict’ (1550), 184 Carolus bell named for, 13, 15 de Granvelle as counsellor, 146, 183 and Ducci, 123–4 François I as prisoner of, 133 funeral of (1558), 178 and heretics, 15–16, 52–3, 93, 103, 109, 111–12, 149–50, 152–3, 184–5 investigates disorder in Antwerp, 170, 187 jailing of Diogo Mendes, 105–7 the Joyous Entry (1549), 15, 18, 34, 82, 148–54, 180, 184, 207 lays siege to Tunis (1535), 69 and legal system in Antwerp, 23, 157 makes the Beurs into clearing house, 117 and maps, 6, 192 and musicians, 140 and the Ottoman Turks, 54, 100, 103, 149–50 visits Antwerp (1515), 143–4 and weigh house in Antwerp, 162 Cheke, Sir John, 187 Chesneau, Thomas, 142 China, 4, 8, 68–9, 97 Christian II, King of Denmark, 24, 67 Christianity and Aertsen’s The Meat Stall, 156–7 and commodification of art, 136–7 Corpus Christi procession, 199 heresy as discreet in Antwerp, 100, 184–6 loss of moderation in Antwerp, 183–7, 188–91 and morality of dancing, 142 pragmatic tolerance in Antwerp, 4–5, 78, 100, 174, 184, 188, 189 Seven Sorrows of Our Lady, 156 smuggling of texts, 47 texts exported to England, 7, 46–7, 48–50, 60 and the useful sin of usury, 102 views of how to read Scripture, 174–5 William the Silent’s Antwerp compromise, 190 see also Calvinism; Catholicism; Lutherans; Protestant religion Christina of Lorraine, 146 Church of Our Lady balls from the Knights of Malta, 20 Carolus bell, 13–14, 15, 24, 119, 203–4 as cathedral, 9, 13, 183 Confraternity of Our Lady, 143, 144 damaged by fire (1534), 21–2 market at, 58, 118, 132 in More’s Utopia, 43 vast size of, 140 Cicero, 35 the Cimmerians, 36 city state notion, 206 city walls (mediaeval defences) and great citadel, 199–200, 201, 205, 208, 214 rebuilding after 1542 siege, 25, 39, 120, 149, 157, 168, 169, 186 Spaniards rebuild bastions, 214 St Joris gate, 27 strike by masons, 170 unfinished state of, 149, 164, 167, 168–9 weaknesses of, 25, 39, 167–8 Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Braun and Hogenberg), 198–9, 208 Cleve, Cornelis van, 139 Cleve, Joos van, 135–7, 139 Cleynaerts, Nicolaes, 99 cloth and wool and Antwerp feitoria, 98–9 and Gaspar Ducci, 127 English wool, 7, 15, 31, 33–4, 42, 45–6, 48 industry in Flanders, 31, 98 trade in Venice, 1 Clusius (Charles de l’Écluse), 69, 194, 205, 214 Cock, Hieronymus, 118, 178 Cock, Symon, 38 Coignet, Michiel, 74 Colmar, 7, 92, 93–4 Cologne, 34, 45, 48, 55, 65, 110, 129, 194, 198, 206 Columbus, Christopher, 43 Condecini, Bartolomeo, 125 confraternities, 143, 144 Constantine, George, 47 Contarini, Gasparo, 2 copper trade, 7, 15, 34, 98, 126, 127 Coracopetra, Henricus, 179 Cordus, Valerius, 70 Coudenberghe, Peeter, 69–70, 214 Dispensatorium, 70–1 countryside/rural life country houses, 10, 11, 67, 128 property booms, 29–30 as source of urban workers/materials, 29–30 and urban merchants, 27–9 and urbanisation, 5, 15, 29 crime and disorder diefclocke (thief bell), 16–17 and Ducci, 59 and fragility of wealth, 120–4, 166, 167, 174, 189–90 and greed, 167 Lepelstraat area, 89–90 riots in early 1550s, 170, 172, 187 rules to make streets safer, 60 Turchi story, 82–4, 85–9 and unofficial stories, 40 violence in culture of commerce, 120–3 ward-masters (wijkmeesters), 172 Cromwell, Thomas, 55, 129 Cyprus, 211 Dale, Jozina van, 77 dance, 76–7, 142 Dati, Giorgio, 114–15 Dee, John, 8, 61–2 Monas Hieroglyphica, 62–3 Denmark, 23, 24, 46, 56, 146 Deodati, Geronimo, 85, 86–9, 123 diamonds, 7, 15, 97, 131, 132, 133 Dias, Gracia, 94 Diericx, Volcxken, 118 Dioscorides (Greek doctor), 68, 70 Dodoens, Rembert, 69, 205 Does, Jan van der, 218 Druon Antigon (monster), 30, 35 Ducci, Gaspar, 59, 120–8, 145, 158, 160, 163 Dudith, Andre, 218 Dürer, Albrecht, 3, 27, 60–1, 96, 98, 131, 140, 142, 143, 196 education Antwerp as centre, 5, 7, 72–3, 74–7 Heyns’ Bay Tree School, 72–3, 74–7 language books, 79–81 Latin (parish) schools, 72 schools for girls, 72–3, 74–7, 141 schools run by ‘free teachers,’ 72 teachers’ Guild of St Ambrose, 72 Egypt, 101 Eighty Years’ War (Dutch War of Independence, 1568-1648) Antwerp’s role in, 6, 14, 56, 191, 199, 205–6, 207–9, 211–14 arrival of Anjou in Antwerp (1582), 180, 207–8 Calvinist regime in Antwerp (1577-85), 6, 9, 14, 15, 16, 23, 66, 74, 199, 205–6, 214 fall of Antwerp (1585), 6, 9, 14, 199, 213–14, 217 impact on Fuggers’ trade, 56 and the Ottoman Turks, 211–13 and the ‘Sea Beggars,’ 202, 212 siege of Antwerp (1584-5), 74, 213 Strada writes history of, 211 violence of mutineers in Antwerp (1576), 12, 14, 39, 203–5 William seeks Protestant allies, 207 Elizabeth I, Queen of England, 134, 140, 146, 207 Emden, 135, 189 England connection with Antwerp, 15, 31, 32, 33–4, 42, 45–6, 51–2, 53, 150, 208 English ale, 170 Jews from Portugal in, 109 Merchant Adventurers guild, 33–4, 42, 129, 189 Protestants fleeing from, 186–7 religious books from Antwerp, 7, 46–7, 48–50, 60 William hopes for help from, 207 wool from, 7, 15, 31, 32, 33–4, 42, 45–6, 48 English House, 51–2, 119, 218 Erasmus, 38, 42, 44, 96, 116–17, 141 In Praise of Folly, 39 Eric XIV, King of Sweden, 140–1, 146 Eucharius, Eligius, 78 Evelyn, John, 214 exchanges, 129 see also the Beurs (Exchange) Fagel, Abigail, 77 Family of Love, 149 conventional appearance, 186 doubtful reputation, 177 Plantin encodes his support, 185 Farnese, Alexander, 213–14, 217 Fernandes, Christopher, 109 Fernandes, Vasco (Grão Vasco), 138 Ferrara, 7–8, 93, 100, 112, 113, 114, 115, 209 feudal system, 27, 28, 29, 39 Filips, Emmanuel, 202 financialization Antwerp as hub, 3, 8, 15, 42, 45–6 and fragments of the old order, 29 land as commodity for new men, 29, 30, 39 Lefebvre on, 5 market for information, 57–8 money markets, 2–3, 5, 8, 15, 109, 117–24, 125–30 and value of money, 116, 128–9, 130 Fischart, Johann, 138 Flanders, 2, 3, 80, 83, 103, 105, 201 army of tall men from, 25 art from, 137, 139 cloth industries, 31, 98 gardens of, 67 guilds and corporations, 31–2 loss of business to Antwerp, 2, 15, 31–4, 42, 84, 97 music of, 140, 141 seizure of Antwerp (1356), 32–3 see also Bruges Flanders, Count of, 32, 33 Florence, 4, 15, 67, 86, 114, 135, 150 Floris, Cornelis, 134 Floris, Frans, 27, 137, 152, 157 food and drink, 4 countryside as source of, 30 quality of water, 171, 172, 205 weekly ‘free’ markets, 18 see also alcohol Ford, John, The Broken Heart, 84 foreign merchants in Antwerp and Brabant-Flanders rivalry, 31–2 Cardano on, 7 and city’s tolerance, 5, 100, 204 and civic identity, 117 and disorder in Antwerp, 189–90 Gaspar Ducci, 59, 120–8, 145, 158, 160, 163 English connection, 15, 31, 32, 33–4, 42, 45–6, 51–2, 53, 150, 208 greeting of Anjou by (1582), 208 headquarters/offices/warehouses, 34, 51–2, 58–9, 96, 97–9, 106 and the Joyous Entry (1549), 148–9, 150, 152–3 move from Bruges, 2, 15, 31–4 nations/nationalities, 15 Christophe Plantin on, 176 privileges in Brabant, 32, 51–2, 53 prove loyal in van Rossum’s siege (1542), 25, 39, 168 and the religious divide, 5, 15–16, 51–3, 96–7, 100, 103–15, 152–3, 174–6, 181–2, 185–6, 204–6 and secret information, 54–5, 57 see also Plantin, Christophe France arrival of Anjou in Antwerp (1582), 207–8 and art market, 133, 137, 164 and Gaspar Ducci, 120, 126 House of Valois, 24 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre, 203 war with the Hapsburgs, 13–14, 23–5, 39, 54, 167–8, 170, 173, 188 William hopes for help from, 207 Franciscanus, Andreas, 16 François I, King of France, 133, 137, 164 Frankfurt Fair, 175, 177, 179, 181, 192, 193–4 mortal dangers of Book Fair, 65 Frans, Peter, 168 Fugger, house of, 55–6, 58, 123, 127, 128, 136, 195, 206 funeral monuments, 133–4 fustian, 34, 127 Gabriel (great bell), 15 Garamond, Claude, 178 gardens of the Netherlands, 67–8, 69–71, 87, 214 Garzoni, Costantino, 210 Gase, Jacob, 90 Geeraerts, Anneke, 75 Geest, Wilhelm van der, 20 Gelder, Lynken van, 77 Gelderland, 23, 24 Genoa, 15, 118, 137, 146, 150, 152–3, 203 Gentile, Stefano, 146 Germany Charles V’s campaigns against Lutherans, 55, 150, 152 and the Cimmerians, 36 German language, 79–80 Germanic cultures, 135, 138, 139, 196 Hanseatic League, 15, 32, 58, 140, 162, 189, 218 imperial troops, 172, 203 merchants in Antwerp, 7, 9, 58–9, 104, 123, 125, 145, 149, 162, 189, 204, 208 mining in south, 2, 7, 15, 34 and movement of English goods, 31, 34, 45 old Germanic tribes, 6 and silver, 98 Gessner, Conrad, 69, 70 Gheens, Jacob, 204 Ghent, 2, 64, 111, 206 giants, 25, 30, 35 Gillis, Peter, 42, 43–4 Goedenhuyze, Joseph (Giuseppe Casabona), 67 Goes, Damião de, 95–7, 107 Golconda (India), 15, 97, 133 gold, 3, 7, 15, 61, 98, 125, 127–8 ‘golden age’ concept, 5–7 the Golden Fleece, Order of, 123, 214 Goltzius, Henrik, 196 Gorp, Jan van, 35–6, 67 governance of Antwerp aldermen, 10–12 Anjou departs, 209 arrival of Anjou (1582), 180, 207–8 Brede Raad (general council), 168 burgomasters, 3, 10–12, 44, 191 Calvinist regime (1577-85), 6, 9, 14, 15, 16, 23, 66, 74, 199, 205–6, 214 city council, 20, 67, 73–4, 159, 160–1, 168 corruption, 158, 159, 160–1, 165–6, 168, 169–70 griffiers (town clerks), 38–40, 42, 43–4, 150–1 magistrates, 14, 15–16, 160, 162, 163–4, 166, 168, 172 Margrave of Holy Roman Empire, 16, 20, 31, 49, 60, 90, 111, 127–8, 183 and market economy, 5 oath of allegiance to Hapsburgs, 148, 149 plague regulations, 64–6 privileges from Emperor, 16, 148, 149 Grammay, Gérard, 178 Granjon, Robert, 178 Granvelle, Antoine Perrenot de, 146, 183–4, 188–9, 190, 202, 211–12 Grapheus, Alexander, 193 Grapheus, Cornelius, 15, 22, 34, 96, 150–1, 152, 153, 154, 159 Gregory XIII, Pope, 176 Gresham, Thomas, 134 Grimel, Alexius, 125 Gruberus, Magnus, 196 Guevara, Felipe de, Comentario de la pintura y pintores antiguos, 138–9 Guicciardini, Lodovico, 16, 25, 55, 69, 140, 149, 205 and the Beurs, 118, 119–20, 128–9, 180 guilds, 22, 75, 134, 150, 168, 172, 216 archery guilds, 164–5, 172 Chambers of Rhetoric (De Bloeyende Wijngaerd), 72, 78, 189, 216 and confraternities, 143 guild houses on Grote Markt, 9, 22, 92 guild of butchers, 156–7, 164 Guild of Coinmakers, 153 Guild of St Anne (hosiers’ guild), 143 Guild of St Luke, 77, 132, 177 missing archives/records, 12 shooting guilds, 170 teachers’ Guild of St Ambrose, 72 weakness of in Antwerp, 31–2, 175, 177 Guser, Mathyus, 90 Gustav I, King of Sweden, 134 Hackendover, Jacobus Godefridus, 64 Hackett, Sir John, 49 Hamburg, 51, 129, 135, 170, 189, 199 Hanseatic League, 15, 32, 58, 140, 162, 189, 218 Hapsburg Empire Antwerp under (from 1585), 9–10, 214–18 campaigns against Lutherans in Germany, 55, 150, 152 claim on all of Antwerp’s past, 9–10, 201, 205, 214–16 and Dona Gracia’s fortune, 102–3, 107–8, 112, 113, 114, 209 and Gaspar Ducci, 120, 122, 123–4, 126 idea of a special destiny, 4, 152 need for Antwerp’s money, 3, 124, 149, 184, 188, 203 and the Ottoman Turks, 21, 45, 53, 54, 100–1, 103, 150, 152, 191, 211–12 and Christophe Plantin, 63, 67–8, 178, 180, 182, 202–3, 205 theatrical rituals of, 148, 151, 152–4 Van Schoonbeke supplies armies of, 172, 173 war with the French Valois, 13–14, 23–5, 39, 54, 167–8, 170, 173, 188 see also Charles V, Emperor; Philip II, King of Spain Hebrew, 48, 50, 52, 53, 61, 104, 180, 181 Bible, 60, 179 Hemessen, Catharina van, 77 Hencxthoven, Jacob van, 167 Henriques, Manoel, 112 Henry VIII, King of England, 51, 53, 54, 57, 105, 109, 123, 126–8, 164 Henschel, Caspar (or Hanshel), 93, 94 Herman, Richard, 56 Hertsen, Adriaan, 10–12, 30 Hertsen, Jacob, 10 Hesiod, 6 Heyden, Michiel van der, 159, 161, 165, 168 Heyns, Peeter, 72–3, 74–6, 77, 218 Hillenius, Johannes, 46 historical identity of Antwerp Alba’s campaign against city’s past, 201, 205 Antwerp as Babylon fantasy, 28, 30, 36–8 Antwerp as Rome fantasy, 28, 30–1, 34–5, 36, 44–5, 165–7 city as idea, 5, 6–7, 8, 21, 25, 26, 27–31, 34–41 gaps in archive record, 11–12, 39 ‘golden age’ metaphor, 5–7 Hapsburg claim on all of past, 9–10, 201, 205, 214–16 ideas move north to Amsterdam, 8, 158, 161, 216–17 legend and myth, 6, 28, 30–1, 35–8 the rise of Netherlandish, 34–5 role of the countryside, 27–30 Scribanius churchifies Antwerp, 215–16 unofficial stories, 40–1 Hobreau, Jean (Petit-Jehan), 141 Hochstetter house (merchant family), 58, 59, 61, 121 Hoefnagel, Joris, 192, 198 Hof, Paul van, 135 Hogenberg, Frans, 189 Holanda, Francisco de, De pintura antigua, 138 Holy Roman Empire arrest of Luther, 96 book burning in, 48, 49, 50 capture and execution of Tyndale, 52–4 Emperor Maximilian I, 33, 62, 106 margrave of, 16, 20, 31, 49, 60, 90, 111, 127–8, 183 and the Ottoman Turks, 100 see also Charles V, Emperor; Hapsburg Empire homosexuality, 90–1 Hooftman, Aegidius, 45 Hooper, Anne, 186 Horace, 39 horses, 2, 17, 30, 82, 110, 123, 132 housing bankers’ mansions on Groenplaats, 22 building booms, 25–6 as capital, 2, 19, 21, 158–60 and the citadel, 201, 205 cleanliness of, 3 country houses, 10, 11, 67, 128 destroyed by Spanish mutineers (1576), 204 and marriage law, 74 merchants’ homes, 9, 51–2, 59, 104, 117 and the new Beurs, 117–18 plague houses, 64, 65 rising prices, 19, 25–6, 163 Schoonbeke’s reshaping of city, 158–9, 162 of the social elite, 3, 10–12, 25, 26, 27, 39, 86, 104, 163, 183 villas in suburbia, 27, 59, 87–8, 163 waste and sewage disposal, 17, 66 wooden, 22–3 Huguenots, 142, 203 humanism, 39, 42–5, 70, 96, 99, 175, 198 Huygens, Constantijn, 90 Ibrahim Pasha, 100 iconoclasm, 6, 183–4, 186, 189, 190 India, 4, 15, 102 Ingolstadt, 192 Inquisition Alba brings to Antwerp, 9, 38, 146, 191 allowance of rumour, 107, 209 familiares, 99–100 fear of in Antwerp, 1, 16, 188, 189, 218 in Portugal, 93, 95, 96, 99–100, 107, 108, 109, 209 in Rome, 103 Isabella of Austria, 67 Isabella of Spain, 101, 102 Islam, 100, 164, 198, 216 Istanbul, 8, 93, 100, 115, 199, 209–11, 212 Italy, 2, 31, 84, 85, 137, 146, 178, 191 art tradition, 137–8, 139, 196 as destination for escaping Jews, 94, 100, 109, 112, 114–15, 209 and maps, 192 merchants in Antwerp, 1, 7, 15, 32–3, 57, 98, 104, 118, 137, 152, 162, 188, 204 and military architecture, 200–1 Jaffa, 19, 21 Janssen, Anna, 77 Janssen, Geeraest, 203, 204 Japan, 4 Jeronymite friars, 175 Jerusalem, pilgrimages to, 13, 19–21 Jesuit College, Antwerp, 216 the Jesuits, 7, 47, 79, 179, 211, 215–16 Jews in Antwerp, 7–8, 15, 68, 92–3, 100, 103–7, 108–10, 111–14, 149, 190 escape route across Europe, 7–8, 92–3, 103, 108–11, 112–15, 209 expulsion from Spain (1492), 101–2, 105 fleeing from Portugal, 7–8, 15, 96, 99–100, 108–15, 149, 209 insecurity of life in Portugal, 99–100, 101–3, 107–8 in Istanbul, 100, 209–11, 212 jailing of Diogo Mendes, 105–7 massacre of in Portugal (1506), 102 novos cristianos or conversos, 15, 68, 92–4, 96, 97, 102, 103–15, 149, 209 João III, King of Portugal, 102, 105–6, 107–8 Jongelinck, Niclaes, 27–8, 36, 132 Josephus, Flavius, 37–8 Juana, Queen of Spain, 140 Junius, Hadrianus, 156, 166 Juvenal, 39, 165–7 Kareets, Margriete, 74 Keyser, Merten de, 166 Knights of Malta, 20 knowledge and ideas Antwerp as hub, 7, 8, 42–5, 46–52, 60–4, 68–71, 209 collections of Ortelius, 195–7 and disorder of 1560s, 195 and merchants, 44–5, 197 secret information, 54–9, 175 travelling craftsmen, 134–6 Laan, Nicolaas van der, 191 Laen, Maria van der, 214 Laet, Jan de, 144 Lamponius, 27 land ownership, 28, 29–30, 39 languages Antwerp as centre, 5, 7, 79–80 Antwerp speaks language of Paradise, 36 books on, 79–81 move to Netherlandish, 34–5 Plantin’s Polyglot Bible, 60, 174–5, 179, 180, 185, 202 Tyndale’s bible, 47–52 Lasso, Orlando di, 146 Laureins, Justus, 194 Le Bé, Guillaume, 178 Lefebvre, Henri, 5, 29 legal system and book crimes, 49, 181 and butchers’ monopoly, 157 case law on neighbours’ disputes, 23 griffiers (town clerks), 38–40, 42, 43–4 inheritance laws, 74 money and justice, 90 privileges to foreign merchants, 32, 51–2, 53 punishment for homosexual activity, 90–1 violence in culture of commerce, 120–3 and women, 73–4 Leiden, 71, 175, 197, 206, 216–17 Leipzig, 199 Leonardo da Vinci, 137 Lepanto, sea battle of (1571), 212 Leuven, 2, 43, 53, 61, 96, 104, 192 liberty, 1, 4–5, 74, 188, 189, 190 Liefrinck, Mynken, 179 Lipsius, Justus, 194, 197 Lisbon, 2, 15, 25, 99, 101, 102, 107–8 Lobbet, Jean, 194 Lobel, Matthias de, 67, 69, 205 Lohoys, Georges, 141 Lollards, 48 London, 15, 46, 47, 63, 109, 129, 209, 213 Lopes, Alves, 109 Lopes, Caterina, 93 Lopes, Gaspar, 104–5 Lopes, Isabel, 94 Lopes, Marten, 123 Lorini, Buonaiuto, 201 Lübeck, 135 Lucca, 15, 82, 83, 85, 86, 87, 124–5, 135, 149 Luilekkerland story, 40–1 Lusitano, Amato, 68 Luther, Martin, 50, 52, 78, 96 Lutherans and Anna Bijns, 78 and Charles V, 52–3, 55, 149–50 and de Granvelle, 211 English Bibles, 7, 45, 46–52, 60 Hapsburg campaigns against in Germany, 55, 150, 152 and idea of the Eucharist, 188 merchants in Antwerp, 15, 96, 111, 149, 189 Scribanius on, 216 William’s attempts at compromise, 190 Luython, Claude, 79–80 Lyons, 72, 114, 126 Machiavelli, Niccolò, 200 Madeira, 32, 97 Maes, Jacob, 164, 170 Maes, Nicholas, 122 Malta, 20, 212 Mandeville, Sir John, 193 Manoel, King of Portugal, 46, 102 Manutius, Paulus, 201–2 Margaret of Parma, 181, 190–1, 213 Margriete Meyererts, 73 maritime trade Brabant-Flanders rivalry, 31–4 port facilities at Antwerp, 2, 169 sixteenth-century trade routes, 1–2, 4, 8, 31, 97, 98–9, 101 and spread of ideas, 7, 8 vulnerability/fragility of, 38–41, 120–4, 166–8, 174, 180–2, 189–90, 194, 203–6, 213–14, 218 Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, 218 Marsili, Alessandro, 84 Martens, Dirk, 43 Mary I, Queen of England, 187 Mary of Hungary, 24, 77, 115, 184 and Ducci, 122, 124, 126, 127, 128, 163 and the House of Mendes, 106, 107, 113 and van Schoonbeke, 163–4, 168–9 Matsys, Quentin, 44, 61, 95 Maximilian I, Emperor, 33, 62, 106 Maximilian II, Emperor, 218 Medici, Cosimo de,’ 55, 122–3, 164, 199, 200 Medici family, 31, 114–15, 132, 141, 200 medicine and alchemy, 68 Antwerp as hub, 8, 60, 63–6, 68–71 books about plague, 63–4 books/literature, 60, 63–4, 68, 70–1, 179 China root for syphilis, 8, 68–9 female surgeons, 77 and gardens of the Netherlands, 67, 68 Lusitano’s Index Dioscoridis, 68 ‘St Anthony’s fire’ (ergotism), 95–6 use of herbs/plants, 8, 67, 68–71, 179 Melanchthon, Philip, 96 Mendes, House of Beatriz de Luna (Dona Gracia Naçi), 102–3, 107–10, 112–15, 209–10 Brianda Mendes, 112, 113 Diogo Mendes, 97, 103–7, 108–9, 112, 113 Francisco Mendes, 101, 102–4, 105–7, 112, 113, 209 João Micas (Joseph Naçi), 114, 115, 210–11, 212 Ana Naçi, 107–8, 113, 209 Mennonites, 216 Menuwey, Jan de, 77 Mercator, Gerardus, 192, 198 Meteren, Emanuel van, 45, 183, 195, 217 Meurier, Gabriel, 75–6, 80, 81, 141 Mexico, 70, 131, 133 Michelangelo, 138 Middelburg, 19, 109, 145 Militia of the Old Longbow, 10 Moer, Guillaume de, 14 money chains of credit, 81 city council as lender, 20 as civic identity, 117 and concept of value, 116, 128–9, 130 Empire’s need of Antwerp for, 3, 124, 149, 184, 188, 203 English Beurs on Wolstraat, 51–2, 119, 218 exchange rates, 57, 119, 120, 125 female lenders, 77 financialization, 3, 5, 8, 116–30 Fugger newsletters, 55–6 housing/property as source of, 2, 19, 21, 158–63, 169 and information/intelligence, 7, 59, 127 insurance market, 19, 20–1, 27 lending for interest in Antwerp, 74, 79, 128–9 letters of credit, 81, 99, 100, 109, 117, 119, 125 loans to the English, 15, 31, 109, 120, 126–8 London Royal Exchange, 129, 134, 213 in Luilekkerland story, 40–1 mints, 27, 101, 127 money markets of Antwerp, 2–3, 5, 8, 15, 109, 117–24, 125–30 moving/transport of, 116, 123, 127–8 New World riches, 126, 152 old financial hub in Bruges, 31, 32, 33 the painter as economic asset, 138–9 printed news-sheets, 57–8 scale of city’s debt (by 1551), 168, 169–70 supply of, 124, 125–6, 128–9 usury forbidden by Church, 102 and Van der Beurse tribe, 33 vulnerability/fragility of wealth, 38–41, 120–4, 166–8, 174, 180–2, 189–90, 194, 203–6, 213–14, 218 see also the Beurs (Exchange) Montanus, Benito Arias, 67–8, 179, 180, 185, 201, 202 More, Thomas, 42, 45, 47 Utopia, 43–4 Moretus, Jan, 216–17 Morillon, Maximilien, 188, 189, 190, 211 Moscow, 198–9, 206, 212 Mostaert, Jan, 99 Mühlberg, battle of (1547), 152 Mulay Hasan (Bey of Tunis), 101 music of bell-ringers, 16 capilla flamenca, 140 commodification of, 5, 130, 140–1, 142, 143–7 holy, 22, 140, 143–4 of the Netherlands, 140–1, 142–6 printed, 143–5, 147 printed polyphony, 143–4 in the streets, 16, 140, 142, 143 Myconius, Oswald, 55 Naples, 3, 114 Navagero, Bernardo, 2, 124 Necton, Robert, 47 Negro, Gabriel de, 103, 111–12 Nettesheim, Cornelius Agrippa von, 35 Netto, Diogo Fernandes, 108, 110 Nettoli, Niccolò, 83, 85, 86, 89 Niclaes, Hendrik, 177, 182 Nicolai, Nicolas (Grundius), 145–6 Nigri, Filips, 186 Nîmes, 199 Nimrod (legendary tyrant), 37–8 Nobili, Niccolò, 125 North Sea, 2, 33, 212 Northern Renaissance, 174 Occo, Pompeius, 136 Orange, House of, 75, 86, 124, 190, 191, 205, 206, 207, 209, 212 Orléans, 10 d’Orleans, Louis, 196–7 Orrida (great bell), 14–15 Ortelius, Abraham background of, 45, 191–2 collections of, 195–7 and fantastic creatures, 193 at Frankfurt Fairs, 192, 193–4 letters/correspondence, 195, 197 painting of at rural event, 28–9 and the religious divide, 183, 185, 194, 195, 217–18 stays in city under Spanish rule, 217–18 travels of, 192–4 as witness to iconoclasm, 183 Album Amicorum, 193, 218 Aurei Saeculi Imago, 6–7 Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 45, 176, 179–80, 192, 193, 197, 198, 205 Thesaurus Geographicus, 196 Otto II, Emperor, 31 Ottoman Turks and Antwerp, 101, 211–13, 216 convention with Antwerp (1583), 212–13, 216 golden throne in Istanbul, 100–1 and the Hapsburgs, 21, 45, 53, 54, 100–1, 103, 150, 152, 191, 211–12 and Islam, 100, 198, 216 and Jews fleeing from Hapsburgs, 100, 103, 115, 209–11, 212 ransoming of pilgrims, 21 seizure of Tunis (1534), 101 Selim and Joseph Naçi, 210–11 trade routes through lands of, 97, 101 war fleets of, 19 and the wool trade, 45 oudkleerkopers (old clothes dealers), 163 Ovid, 39–40 Paciotto, Francesco, 200–1 Packington, Augustine, 50 Paesschen, Dierick, 19–21 Palmanova (near Venice), 161 Pape, Jean de, 131 Papenbroch, Daniel, Annales Antverpienses, 216 Paracelsus (alchemist), 8, 68 Paris as centre of news and rumour, 83, 84–5 Haussmann’s boulevards, 10 Plantin’s shop in, 175, 180–1, 182, 203 and Guilherme Postel, 185 as print centre, 43, 44, 206 size of in early sixteenth-century, 15 Parsons, Robert, 47 Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards, 196 pearls, 15, 101, 124, 127, 133 Pegolotti, Francesco Balducci, 32 Peltz, Elizabeth, 144 Perez, Loys, 103 Pérez, Luis, 205 Peter Martyr Vermigli, 187, 188 Philibert of Châlon, Prince of Orange, 86 Philip II, King of Spain Anjou replaces in Antwerp, 180, 207–8 and Antwerp’s money, 3, 149, 188, 203 appoints Alba as governor, 191 and art as commodity, 138–9 art collection, 164 court gardens of, 67–8 de Granvelle as counsellor, 146, 183–4 and disorder in Antwerp, 187, 188, 189, 199–200 and Hapsburg special destiny, 4, 152 and Hapsburg world of theatre, 151, 152 and heretics, 189, 190–1, 211–12 the Joyous Entry (1549), 15, 18, 34, 82, 148–54, 180, 184, 207 and new breviary (1568), 202–3 personality of, 149, 184 and Christophe Plantin, 180, 182, 202–3, 205 war with France, 188 Phillips, Henry, 52–3 piracy, 2, 116, 195 Barbary pirates, 19, 200 Pires, Diogo (Didacus Pyrrhus Lusitanus), 109, 138 Pires, Henrique, 68 Pisa, 114, 135 plague, 63–6, 75, 114 Plantin, Christophe and arrival of Anjou, 208 background of, 175–7 and Calvinist regime, 205–6 and Coudenberghe’s Dispensatorium, 70–1 dominates print trade in Netherlands, 179–81 and educational books, 76, 81 fonts/typefaces, 178, 180, 181, 203 and Frankfurt Fairs, 179, 181 and the Hapsburgs, 63, 67–8, 178, 180, 182, 202–3, 205 illustrated texts, 178–9 in Leiden, 175, 206, 216–17 and new breviary (1568), 202–3 and Niclaes, 177, 182 and Ortelius, 179–80, 191, 196, 205 pays off Spanish soldiers (1576), 204–5 permissions (privileges) to print books, 178 Polyglot Bible, 60, 174–5, 179, 180, 185, 202 and religious divide, 174–6, 180–2, 185–6, 202–3, 204–6 shop in Antwerp, 179 shop in Paris, 175, 180–1, 182, 203 Plato, 200 Pliny, 35 Plutarch, 77 polder land, 30, 67, 145, 146, 192 Portugal Casa de India, 95, 96–7, 107 craftsmen from, 98 Dona Gracia collaborates with, 209–10 and eastern trade routes, 4 feitoria (headquarters), 34, 96, 97–9, 106 Inquisition in, 93, 95, 96, 99–100, 102, 107, 108, 109, 209 insecurity of Jewish life in, 99–100, 101–3, 107–8 and Jews expelled from Spain, 101–2, 105 Jews fleeing from, 7–8, 15, 92–4, 96, 99–100, 103, 108–15, 149, 209 merchants in Antwerp, 4, 6, 15, 34, 58, 95–9, 103–7, 125–6, 149, 150, 209 Netherlandish art popular in, 95, 133, 138 spice ships, 6, 15, 32, 34, 68, 95, 97–8, 101, 102–8 Possevino, Antonio, Moscovia, 179 postal systems, 187, 194–5 Postel, Guilherme, 185–6, 197 Poyntz, Thomas, 51–2 Printz, Daniel, 197 prostitution, 89–90 Protestant religion Antwerp as way-station, 186–7 English Bibles, 7, 45, 46–52, 60 ‘exodus’ from city (from 1567), 191, 205 move north after fall of Antwerp (1585), 199, 214 and psalms in Dutch, 146 Schmalkaldic League, 152 ‘Sea Beggars,’ 202, 212 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre, 203 Tyndale’s bible, 47–52 William seeks allies, 207 see also Calvinism; Lutherans public health and overcrowding, 166 plague regulations, 64–6 waste and sewage disposal, 17, 66 publishing and printing Antwerp as hub, 8, 42–4, 46–52, 60 bookbinders, 176, 180 copperplate engraving, 178, 180, 198 exports to England, 7, 46–7, 48–50, 60 female printers, 77 of financial statistics, 57–8 fonts/typefaces, 50, 178, 180, 181, 203 Hoochstraten’s presses, 50 of Juvenal’s Satires, 166 of More’s Utopia, 43–4 move north after fall of Antwerp (1585), 216–17 the new breviary (1568), 201–3 Ortelius’ broad view of, 195, 197 paper for, 8, 42, 176–7, 180 penalties for book crimes, 49, 181 pestboekjes (plague pamphlets), 63 printed music, 143–5, 147 printers’ district, 63, 118 religious books to England, 7, 46–7, 48–50, 60 woodcut borders on the pages, 46 of the wrong kind of holy books, 146, 149, 174–5, 180, 181, 182 see also books/literature; Plantin, Christophe pubs and bars, 171 Quinget, Christoffel, 162 Radermacher, Johannes, 45, 192 Raet, William de, 135 Rantzau, Heinrich, 59 Rensi, Antonio, 120, 121 Requesens, Luis de, 203 Rhedinger, Nicolaus, 197 Rhine, River, 2, 48, 52–3, 100, 110, 193, 196, 209 Rieulin, Jacques, 16 Rio, Hieronymus del, 189–90 Rivière, Jeanne, 176 Rodrigues, Antoine, 99 Rogers, Daniel, 34 Rogers, John, 52 Rogna, Antonio della, 109 Rome, 19, 20, 137, 212 ancient, 9–10, 30, 34–5, 68, 72, 133, 134, 148, 156, 165–7, 193, 197 Antwerp as Rome fantasy, 28, 30–1, 34–5, 36, 44–5, 165–7 Church of St John Lateran, 146 city walls, 199 Fugger newsletters in, 55 Inquisition in, 103 in Juvenal’s Satires, 39, 165–7 Mussolini’s editing of, 9–10 the new breviary (1568), 201–3 printing of Columbus’ letter, 43 Vatican printers, 43, 201–2 Rossum, Maarten van, 13–14, 23–5, 39, 45, 167–8 Rossy, Jacomo de, 90 Rubens, Peter Paul, 5, 214–15, 216 Ruiz, Simon, 119 Ruremund, Catherine van, 49 Ruremund, Christoffel van, 46, 49 Ruremund, Hans van, 49 Ryt, Willem van der, 159, 165 Saint-Omer, Charles de, 70 Salkyns, William, 186–7 Salonika, 8, 93, 94, 103, 115, 209 Sambucus, Johannes, 195 Sampson, Richard, 42 Sampson, Thomas, 187 Santiago de Compostela, 19 São Tomé, 97, 101–2 Scheldt, River, 2 blockades of, 6, 194, 202, 213, 216 blocking of by ice, 2, 19–20 fireships on (1585), 14, 213 Roman fort on, 30 Schetz, Erasmus, 103, 104, 116–17 Schetz brothers, 27 Schiappalaria, Stefano Ambrogio, 153 Schijn, River, 171 Schille, Jan van, 193 Schmalkaldic League, 152 Schoonbeke, Gilbert van, 120–2, 158–65, 167, 168–70, 171–3, 216 Schoonbeke, Gilbert van (father), 158, 160 Schot, Frans, 157, 173 Schottus, Andreas, 195 Schoyte, Aart, 10, 30 Schroegel, George, 34 Scribanius, Carolus, 137, 215–16 Seiler, Hieronymus, 125 Selim (Ottoman Sultan), 115, 210–11, 212 Serrano, Manoel, 103, 114 Seville, 2, 12, 126 shipping Antwerp insurance market, 19, 20–1, 27 Antwerp merchant marine, 21 Antwerp’s hiring of, 19, 20–1, 34 docking at Antwerp, 2, 7, 33, 169 fireships on Scheldt (1585), 14, 213 pilgrimages to Jerusalem, 13, 19–21 Portuguese caravels, 2, 19, 97 Venetian galleys, 2, 19, 31 shops, 18, 118, 170, 176, 196, 218 apothecaries,’ 69, 70 bookshops, 45, 46, 130, 175, 179, 180–2, 198 women in charge of, 77 Sidney, Sir Philip, 194 silver, 2, 7, 8, 14, 15, 34, 98, 101, 125–6 Silvius, Willem, 63, 74 slave trade, 7, 8, 15, 98–9 smilax (China root), 8, 68–9 smuggling, 47 social structure of Antwerp building regulations after 1542 siege, 25–6 burgomasters, 3, 10–12, 44, 191 commerce as civic identity, 117 and education for girls, 73, 77 feudal system, 27, 28, 29, 39 fragments of the old order, 28, 29, 39 grandees, 1, 10, 22, 85, 86, 121, 130, 154, 158, 159, 168, 176 housing of social elite, 3, 10–12, 25, 26, 27, 39, 86, 104, 163, 183 land as commodity for new men, 29, 30, 39 land ownership, 28, 29–30, 39 magistrates, 14, 15–16, 160, 162, 163–4, 166, 168, 172 money and justice, 90 urban elites and the countryside, 28–9 villas in suburbia, 27, 59, 87–8, 163 violence in culture of commerce, 120–3 vulnerability/fragility of, 38–41, 120–4, 166–8, 174, 180–2, 189–90, 194, 203–6, 213–14, 218 Spain and art market, 138–9 and Bruges, 32 cost of money in, 3 expulsion of Jews (1492), 101–2, 105 and gardens of the Netherlands, 67–8 merchants in Antwerp, 7, 15, 57, 119, 128, 152, 204, 205 Netherlandish art popular in, 95, 133 and New World riches, 126, 152 Spanish Netherlands Duke of Alba as governor, 3, 12, 150, 182, 186, 191, 199, 200, 201, 217 fall of Antwerp to Spanish (1585), 6, 9, 14, 199, 213–14, 217 income from tax on exports, 184 Luis de Requesens as governor, 203 Margaret of Parma as governor, 181, 190–1, 213 Mary of Hungary as Governor, 24, 124, 126, 127, 163–4, 168–9, 184 need for Antwerp’s money, 3, 124, 149, 184, 188, 203 rule of Albert and Isabella, 215 States General, 188, 206, 208 unrest of 1566-7 period, 183–4, 189–90 spice trade, 7, 8, 32, 34, 40, 68, 77, 97–8 Casa de India, 95 first Portuguese ships (1501), 6, 15, 97 and the House of Mendes, 101, 102–8 Ottoman routes, 101 spies, 7, 54, 56–7 Spillemans brothers, 118 St Amand, 31 St Andreus, Church of, 90 ‘St Anthony’s fire’ (ergotism), 95–6 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre, 203 St Bernard, Abbot of, 206 St Elizabeth Gasthuis (hostel/hospital), 64–5, 152, 164–5 St Eloy, 31 St Joris, Church of, 90 Steenwinkel, Laurens van, 135 Stegemans, Anna, 158 Stinen, Jasper, 106 Strada, Famianus, 211 Strype, John, 187 Suleiman (Ottoman Sultan), 100–1, 210, 212 Susato, Tielman, 142–3, 144, 145–7 Swandeleeren, Heylwijch, 131–2 Sweerts, Francis, 192, 195 syphilis, 8, 68–9 Tafur, Pero, 164 tapestry-makers, 164–5, 170 Tassis, Giovanni Battista de, 194 taxes imperial income from Antwerp, 3, 15, 184, 188 raised for new citadel, 200–1 and rebuilding of city walls, 168, 169, 186 refusals to pay, 168, 186, 189 tax collectors, 27, 126, 145–6 Theobald, Thomas, 53 Thorius, Johannes, 194 Tiepolo, Paolo, 3 tobacco, 69–70 Tonnellero, Pero, 110 Town Hall burning of (1576), 12, 14, 39, 205 Gothic building (before 1549), 18 interim wooden structure (1549), 18, 34, 151–2 new structure (1560s), 34, 135 trade and commerce Aertsen’s The Meat Stall, 155–7, 165–6, 172–3 Antwerp as hub, 3, 7, 31–2, 42, 45–6, 209 Antwerp’s expansion, 1–3, 15, 31 arms trade, 215 brand marks, 46 the business of plague, 63–6 buying and selling process, 59 Casa de India, 95, 96–7, 107 as civic identity, 117 female traders, 74, 77 global trade routes, 1–2, 4, 8, 31, 97, 98–9, 101 the House of Mendes, 101, 102–10, 112–15, 209–10 and knowledge/scholarship, 44–5, 195–7 in Luilekkerland story, 40–1 Mediterranean, 97, 101 merchant assistants, 97–8 and plague regulations, 65–6 Portuguese craftsmen, 98 Portuguese feitoria (headquarters), 34, 96, 97–9, 106 shift from Bruges to Antwerp, 2, 15, 31–4, 42, 84, 97 trade fairs, 2, 4, 15, 32, 58 violence in culture of, 120–3 vulnerability/fragility of, 38–41, 120–4, 166–8, 174, 180–2, 189–90, 194, 203–6, 213–14, 218 the weigh house, 120–1, 160, 161–2, 172–3 weigh house (old), 120–1 see also foreign merchants in Antwerp; maritime trade Trithemius, Johannes, Steganographia, 62 Trognaesius, Joachim, 79 Tucher, Lazarus, 121 Tunstall, Cuthbert, 42, 48, 50 Turchi, Simone, 82–4, 85–9 Turin, 200 Tymbach, Bernaert, 74 Tyndale, William, 47–54 urbanisation, 5, 15, 29 Ursel, Lancelot van, 161 Usque, Samuel, Consolaçam, 107, 209 Valerius Cordus, 79 Vasari, Giorgio, 137–8 Vaughan, Stephen, 49–50, 51, 55, 57, 59, 60, 123, 126–8 Veken, Beatrix van der, 158 Venice, 100, 180, 209, 211 Antwerp compared to, 2–4 Fugger newsletters in, 55 and the Ottoman Turks, 21, 210, 212 printed music in, 144–5 and trade routes, 1–2 Vermigli, Peter Martyr, 187, 188 Vernois, Pierre, 178 Verstegan, Richard, Theatrum Crudelitatum haereticorum nostri temporis, 175 Vesalius, 68, 69, 179 Vezeleer, Joris, 133 Vienna, 199 Viking raids, 30, 35 Vilvoorde castle, 53–4 Virgil, the Aeneid, 22 Vitelli, Chiappino, 200 Vives, Juan Luis, 35, 76–7 Vivianus (city chaplain), 193 Volder, Willem de, Acolastus, 92 Vuysting, Johannes, 93, 103, 109 Waelrant, Hubert, 144 Walraven, Jacques, 157, 172–3 water engineers, 135 Welser, Bartolomeo, 125 Welser, house of (merchant family), 58, 125 Werve, Maria van den, 85, 86, 121 Wesenbeeke, Jacob van, 190 Wesenpuele, Magdalena van, 73 Wickram, Georg, 7, 89, 91–2, 94 William the Silent (William of Orange), 75, 124, 190, 191, 205, 206, 207, 209, 212 Wilson, Thomas, 129 wine trade, 31, 74, 83, 169, 215 Wingfield, Richard, 57 Wittenberg, 96 Wolfenbüttel, 135 Wolsey, Cardinal, 42 women art dealers, 131–2 and dancing, 142 gender relations in Antwerp, 1, 4, 72, 85–6 and languages, 79 and legal system, 73–4 and marriage, 73–4 painters, 77 printers, 179 schools for girls, 72–3, 74–7, 141 and sexual matters, 1, 4, 72, 76–7, 85–6, 141–2 traders, 74, 77 and van Rossum’s siege (1542), 24–5 writers, 78 wool trade see cloth and wool workforce apprentices, 74 casting of Carolus, 13, 14 countryside as source of, 29 craftsmen, 29, 98, 99, 134–6, 150, 151, 152, 169 housing for, 26 labour market, 22 night workers, 17, 66 ordered by bells, 16 of Plantin, 177, 181, 182, 202–3 strikes/unrest, 170 Wyllughby, Lord, 56 Zoncha, Giovanni, 1, 4, 188 Zuichem, Wigle de, 211 Zwingli, Huldrych, 55 THIS IS JUST THE BEGINNING Find us online and join the conversation Follow us on Twitter twitter.com/penguinukbooks Like us on Facebook facebook.com/penguinbooks Share the love on Instagram instagram.com/penguinukbooks Watch our authors on YouTube youtube.com/penguinbooks Pin Penguin books to your Pinterest pinterest.com/penguinukbooks Listen to audiobook clips at soundcloud.com/penguin-books Find out more about the author and discover your next read at penguin.co.uk PENGUIN BOOKS UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

…