Light This Candle: The Life & Times of Alan Shepard--America's First Spaceman

by

Neal Thompson

Published 2 Jan 2004

The rocket lifted four inches off the ground but then the imperfect electrical cord disconnected a few milliseconds too soon, which automatically shut down the engines. Such failed launches weren’t uncommon at a time when the success rate of certain American rockets hovered around an appalling 50 percent. Shepard’s response to such failures: What do you expect from rockets built by the lowest bidder? By mid-1960, as the astronauts passed their first anniversary as a team and the training and traveling routine reached full speed, the seven were on the road constantly, hundreds of days a year— so much traveling that Gordo Cooper’s accountant told him he could pick any state he wanted as his residence for tax purposes.

…

I won’t even tell anyone. But I want to know.” Shepard thought about it a minute, then looked at Cronkite. “Well, you know,” he said, “I looked at those toggle switches I had to turn on cue, I looked at the dials I had to turn on cue, and I thought to myself: My God, just think, this thing was built by the lowest bidder.” The two men cracked up, and Cronkite realized he hadn’t seen that toothy, big-lipped smile in ages. About six months after Victor Poulos emerged from surgery, the symptoms that had dogged Shepard for more than five years disappeared. House’s surgery was a great success, and Shepard returned to Slayton’s office and told him that he was ready to fly again.

Comedy Writing Secrets

by

Mel Helitzer

and

Mark Shatz

Published 14 Sep 2005

Humor may be our only rational way of coping with the fear of terrorism, an invasion of spooks from outer space, or the chemical mutation of our planet. They asked John Glenn what he thought about just before his first capsule was shot into space, and he said: "I looked around me and suddenly realized that everything had been built by the lowest bidder." Group Differences: Us vs. Them Mocking the beliefs or characteristics of social groups is one of humor's most controversial subjects because it caters to our most primitive 48 Comedy Writing Secrets instincts—prejudice and insecurity. We hope to maintain some sense of superiority by ridiculing abnormal characteristics of others.

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by

Chris Impey

Published 12 Apr 2015

The Space Shuttle was like a Ferrari, but it was a project driven by performance, not cost. Thousands of man-hours were required to refurbish it between launches. The astronauts knew they were riding in an exquisite machine, where hundreds of thousands of parts had to work in perfect synchrony (Figure 25). They also were uncomfortably aware that it had been built by the lowest bidder. Rocket technology hasn’t improved much since the 1960s. But there’s a cheaper way to design rockets. Figure 25. The most powerful and highest-performance rocket engine ever built. The RS-25 was built by Rocketdyne as the main engine for the Space Shuttle, generating 420,000 pounds of thrust at launch.

Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man's First Journey to the Moon

by

Robert Kurson

Published 2 Apr 2018

Then they walked across an access arm to a small loading area, where technicians would make a final check of the space suits. From there it was a short walk for the astronauts across a small metal bridge and into the spacecraft. It was 4:58 A.M., still dark outside. From his vantage point, Lovell couldn’t help but think of the old astronaut joke—How does it feel to sit atop a vehicle built by the lowest bidder? A NASA staffer gave the signal for the astronauts to start loading. Borman went first and, after some maneuvering, settled into the left-hand seat of the command module, lying flat on his back as an airline pilot would if his airplane were tipped back onto its tail. A technician gave Anders a hug, then sent him, too, into the spacecraft, where he took the right-hand seat in the small cabin.

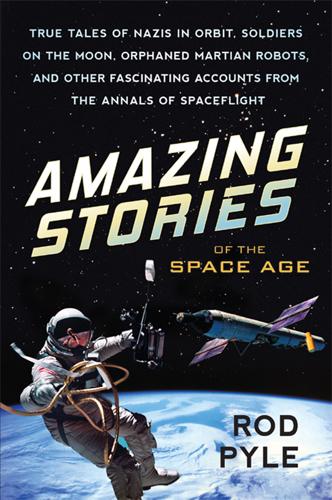

Amazing Stories of the Space Age

by

Rod Pyle

Published 21 Dec 2016

About 240,000 miles away, that son of Ohio, Neil Armstrong, along with his partner Buzz Aldrin, had made a weightless crawl through a short tunnel connecting the Apollo 11 capsule to the waiting lunar module, leaving the third member of the crew, Michael Collins, to a lonely vigil. He would orbit the moon alone as his two comrades gambled their lives on $32 million of technology, the cost of one of NASA's lunar modules, which had, as always, been built by the lowest bidder.1 Soon the two astronauts would disconnect from the command module, make only the second descent toward the moon's surface ever (Apollo 10 had performed a “dress rehearsal” in May, descending and coming back but not landing), and attempt to land. Collins wished them well, but in private thought their chances of success were about fifty-fifty.2 They did in fact make a successful landing, but the entire scenario was ultimately jeopardized by a slug of ice in a fuel line that wouldn't have lasted ten seconds on an overheated Wapakoneta sidewalk.