Service Design Patterns: Fundamental Design Solutions for SOAP/WSDL and RESTful Web Services

by

Robert Daigneau

Published 14 Sep 2011

These rules are often retrieved from Service Registries (see Figure 6.15). Clients that communicate with services through ESBs typically have to use a standard set of messages often referred to as the Canonical Data Model [EIP]. The advantage with this approach is that you won’t need to create specialized services designed to process requests from specific client applications. Since all clients are forced to use the canonical model, a single service can be created to process all requests. Unfortunately, this shifts the burden over to the client, and clients may have to use a Message Translator [EIP] to convert their messages to the canonical form.

…

Once the bus has received a message, it may Virtual Service A Client Virtual Service B Virtual Service C Service Registry Message Store Enterprise Service Bus Wire Tap Target Service A Target Service B Business Intelligence Applications Target Service C Figure 6.15 ESBs provide a layer of indirection that enables services to be added, upgraded, replaced, or deprecated while minimizing the impact on client applications. A Q UICK R EVIEW OF SOA I NFRASTRUCTURE P ATTERNS 223 use a Message Translator to convert the canonical message to the format defined in the service’s contract. This enables the service’s contract and canonical data model to vary independently. A similar process is used to convert service responses to the canonical form, and finally to the structures used by clients (see Figure 6.16). A third key function performed by ESBs is protocol translation and transport mapping. This feature may be employed when the target service uses a protocol or transport that is foreign to the client.

…

See also Proxy servers; Reverse proxy commodity caching technologies, 45 Consumer-Driven Contracts, 253 HTTP Post, 41 Idempotent Retry, 173 Intercepting Exception Handler, 204 Origin Server, 288 perimeter caches, 52 Representational State Transfer, 289 Request/Response and intermediaries, 57 Resource APIs and REST, 46 Resource APIs and Service Interceptors, 49 Server-Driven Negotiation, 73 Service Gateway, 172 Service Interceptor, 195 web service state management, 133 WS-Reliable Messaging, 217 Cacheable responses, 46 Callback service Orchestration Engine, 224 Request/Acknowledge, 63–65, 68 Workflow Connector, 158–162 Canonical Data Model [EIP], 222 Castor, 279. See also Data binding Data Transfer Object, 97 Channel Adapters [EIP], 222 Chatty service contracts Datasource Adapters and Latency, 140 Latency, 16 Service Descriptor, 177 Chunky data transfers, 100–101 Chunky service contracts, 177–178 Data Transfer Object, 100 Latency, 16 Circular references, DTOs, 95 Cited works, 297–300 Client preferences, supporting, 44 Client-driven negotiation, Media Type Negotiation, 72–73 Client/server constraints, Resource API, 46 Client-service coupling, Service Connector considerations, 173 Client-service interactions Client-Service Interactions, 51 summary of patterns, 53.

Reactive Messaging Patterns With the Actor Model: Applications and Integration in Scala and Akka

by

Vaughn Vernon

Published 16 Aug 2015

However, when employing a Canonical Message Model and assuming that each application has a distinct model, you would need only 12 translators. However, in practice, supporting a cross-application model in the manner that the Canonical Data Model prescribes often proves to be a futile effort. For one thing, it’s nearly impossible to get every stakeholder representing the number of applications (for example, the six in Figure 8.5) to agree on a minimal model that can support everyone. So, the Canonical Data Model usually ends up with a superset of all the objects and properties that all the stakeholders imagine they might need at some point in time. The model becomes unwieldy from the start and ends up not serving any single one of the interests well [Tilkov-CDM].

…

Since the routing and translation code almost certainly does not represent an investment in your core business software models, you probably don’t want to continually commit the efforts of your valuable developer staff in this kind of sinkhole. After the first few router and translator challenges are tackled by your team, forming a well-understood approach, delegating the ongoing routing and translation work as a necessary evil can be a big benefit to your internal teams. Canonical Message Model Typically a Canonical Data Model [EIP] is used when you need to integrate several or many applications, and you want to reduce the dependencies of each application on the others’ types. Consider the six applications in the diagram in Figure 8.5. One of the main reasons you would choose to use this pattern is if each of the six applications integrates with every other application.

…

[ScalaTest] www.scalatest.org/ [SIS] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_information_system [Split-Brain] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Split-brain_(computing) [SRP] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_responsibility_principle [Suereth] Suereth, Joshua. Scala in Depth. Shelter Island, NY: Manning Publications, 2012. [Tilkov-CDM] https://www.innoq.com/en/blog/thoughts-on-a-canonical-data-model/ [Transistor Count] http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transistor_count [Transistor] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_transistor [Triode] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triode [Typesafe] http://typesafe.com [Vogels-AsyncArch] www.webperformancematters.com/journal/2007/8/21/asynchronous-architectures-4.html [Vogels-Scalability] www.allthingsdistributed.com/2006/03/a_word_on_scalability.html [Westheide] www.parleys.com/play/53a7d2c6e4b0543940d9e54d [WhitePages] http://downloads.typesafe.com/website/casestudies/Whitepages-Final.pdf?

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by

Daniel Susskind

Published 14 Jan 2020

Indeed, in the dominant model used in the field, it was impossible for new technologies to make either skilled or unskilled workers worse off; technological progress always raised everyone’s wages, though at a given time some more than others. This story was so widely told that leading economists referred to it as the “canonical model.”15 A NEW STORY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY The canonical model dominated discussion among economists for decades. But recently, something very peculiar began to happen. Starting in the 1980s, new technologies appeared to help both low-skilled and high-skilled workers at the same time—but workers with middling skills did not appear to benefit at all.

…

And this particular version was characterized by a “constant elasticity,” meaning that a percentage change in the relative price of two inputs would always cause a constant percentage change in the use of those inputs. In this model, new technologies could only ever complement workers. See Acemoglu and Autor, “Skills, Tasks and Technologies,” p. 1096, for an account of the “canonical model,” and p. 1105, implication 2, for a statement of the fact that any kind of technological progress in the canonical model leads to an increase in absolute wages of both types of labor. 16. This is an edited version of Figure 3.1 in OECD, OECD Employment Outlook 2017 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017). 17. See Autor, “Polanyi’s Paradox and the Shape of Employment Growth.” 18.

…

And using pay as a proxy measure for that particular definition of skill does turn out to be a reasonable thing to do: as we have seen, people with more schooling behind them tend to earn more as well. So whether you line up jobs according to their level of pay or the average number of years of schooling that people in them have does not really matter—the hollowing-out pattern looks roughly the same.20) The hollowing out of the labor market was a new puzzle. And the canonical model that dominated economic thinking in the late twentieth century was powerless to solve it. It was narrowly focused on just two groups of workers, the low-skilled and the high-skilled, and had no way to explain why middling-skilled workers were facing such a very different fate from their low- and high-skilled contemporaries.

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by

Kariappa Bheemaiah

Published 26 Feb 2017

The link between the relative demand for skills and technological advancement , in particular the “skill bias” of technical change (SBTC), was first established with Tinbergen’s (1974, 1975) founding work and the development of the canonical model (Acemoglu & Autor, 2010), which offered a structure to measure the changes in the return earned by workers with respect to their skill. The canonical model was especially useful in measuring the skill attribute of earnings, as it offered a model to conduct comparative analysis of different worker groups simultaneously. The empirical success of the canonical model helped account for salient changes in the distribution of earnings (Autor, 2010). However, despite the model’s applicability, modern changes in labor markets and employment trends motivated the creation of a new model more attuned to the modern era, as one of the shortcomings found in the canonical model was its lack of a concrete definition for “tasks.”

…

However, despite the model’s applicability, modern changes in labor markets and employment trends motivated the creation of a new model more attuned to the modern era, as one of the shortcomings found in the canonical model was its lack of a concrete definition for “tasks.” A task, as per Autor and Acemoglu (2010), is defined as a unit of work activity that produces an output, i.e., good or service. In contrast, a skill is a worker’s endowment or capability to perform a task or various tasks. These researchers determined that the distinction between skill and task needed to be formally addressed, as a worker’s skill to perform a task(s) was directly related to the quality of the good or service being produced, and hence to the wages earned by the worker.

…

Buiter The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (2011), Guy Standing Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2015), Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams Raising the Floor: How a Universal Basic Income Can Renew Our Economy and Rebuild the American Dream (2016), Andy Stern Index A Aadhaar program Agent Based Computational Economics (ABCE) models complexity economists developments El Farol problem and minority games Kim-Markowitz Portfolio Insurers Model Santa Fe artificial stock market model Agent based modelling (ABM) aggregate behavioural trends axiomatisation, linearization and generalization black-boxing bottom-up approach challenge computational modelling paradigm conceptualizing, individual agents EBM enacting agent interaction environmental factors environment creation individual agent parameters and modelling decisions simulation designing specifying agent behaviour Alaska Anti-Money Laundering (AML) ARPANet Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) Atlantic model Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) Autor-Levy-Murnane (ALM) B Bandits’ Club BankID system Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN) Bitnation Blockchain ARPANet break down points decentralized communication emails fiat currency functions Jiggery Pokery accounts malware protocols Satoshi skeleton keys smart contract TCP/IP protocol technological and financial innovation trade finance Blockchain-based regulatory framework (BRF) BlockVerify C Capitalism ALM hypotheses and SBTC Blockchain and CoCo canonical model cashlessenvironment See(Multiple currencies) categories classification definition of de-skilling process economic hypothesis education and training levels EMN fiat currency CBDC commercial banks debt-based money digital cash digital monetary framework fractional banking system framework ideas and methods non-bank private sector sovereign digital currency transition fiscal policy cashless environment central bank concept of control spending definition of exogenous and endogenous function fractional banking system Kelton, Stephanie near-zero interest rates policy instrument QE and QQE tendency ultra-low inflation helicopter drops business insider ceteris paribus Chatbots Chicago Plan comparative charts fractional banking keywords technology UBI higher-skilled workers ICT technology industry categories Jiggery Pokery accounts advantages bias information Blockchain CFTC digital environment Enron scandal limitations private/self-regulation public function regulatory framework tech-led firms lending and payments CAMELS evaluation consumers and SMEs cryptographic laws fundamental limitations governments ILP KYB process lending sector mobile banking payments industry regulatory pressures rehypothecation ripple protocol sectors share leveraging effect technology marketing money cashless system crime and taxation economy IRS money Seigniorage tax evasion markets and regulation market structure multiple currency mechanisms occupational categories ONET database policies economic landscape financialization monetary and fiscal policy money creation methods The Chicago Plan transformation probabilities regulation routine and non-routine routinization hypothesis Sarbanes-Oxley Act SBTC scalability issue skill-biased employment skills and technological advancement skills downgrading process trades See(Trade finance) UBI Alaska deployment Mincome, Canada Namibia Cashless system Cellular automata (CA) Central bank digital currency (CBDC) Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Chicago Plan Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) Complexity economics agent challenges consequential decisions deterministic and axiomatized models dynamics education emergence exogenous and endogenous changes feedback loops information affects agents macroeconoic movements network science non-linearity path dependence power laws self-adapting individual agents technology andinvention See(Technology and invention) Walrasian approach Computing Congressional Research Service (CRS) Constant absolute risk aversion (CARA) Contingent convertible (CoCo) Credit Default Swaps (CDSs) CredyCo Cryptid Cryptographic law Currency mechanisms Current Account Switching System (CASS) D Data analysis techniques Debt and money broad and base money China’s productivity credit economic pressures export-led growth fractional banking See also((Fractional Reserve banking) GDP growth households junk bonds long-lasting effects private and public sectors problems pubilc and private level reaganomics real estate industry ripple effects security and ownership societal level UK DigID Digital trade documents (DOCS) Dodd-Frank Act Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model E EBM SeeEquation based modelling (EBM) Economic entropy vs. economic equilibrium assemblages and adaptations complexity economics complexity theory DSGE based models EMH human uncertainty principle’ LHC machine-like system operating neuroscience findings reflexivity RET risk assessment scientific method technology and economy Economic flexibility Efficient markets hypothesis (EMH) eID system Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer (EDVAC) Elliptical curve cryptography (ECC) EMH SeeEfficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) Equation based modelling (EBM) Equilibrium business-cycle models Equilibrium economic models contract theory contact incompleteness efficiency wages explicit contracts implicit contracts intellectual framework labor market flexibility menu cost risk sharing DSGE models Federal Reserve system implicit contracts macroeconomic models of business cycle NK models non-optimizing households principles RBC models RET ‘rigidity’ of wage and price change SIGE steady state equilibrium, economy structure Taylor rule FRB/US model Keynesian macroeconomic theory RBC models Romer’s analysis tests statistical models Estonian government European Migration Network (EMN) Exogenous and endogenous function Explicit contracts F Feedback loop Fiat currency CBDC commercial banks debt-based money digital cash digital monetary framework framework ideas and methods non-bank private sector sovereign digital currency transition Financialization de facto definition of eastern economic association enemy of my enemy is my friend FT slogans Palley, Thomas I.

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by

Edward Chancellor

Published 15 Aug 2022

Even countries with relatively high interest rates enjoyed no respite, since they were inundated with foreign capital flows.fn9 There’s no need to appeal to ad hoc explanations: easy money produced the boom and the boom was followed by the inevitable bust. The closed community of central bankers and monetary economists remained obdurate to monetary explanations for the crisis. They had invested too much time and effort in their economic models and were reluctant to jettison them. Their canonical model assumes that an economy is only knocked off course by random or ‘exogenous’ shocks, such as the 1973 oil crisis. It has no place for money and credit. Interest rates are given and errors in monetary policy are revealed by instability in consumer prices but not asset prices. Speculative bubbles and irrational exuberance are not countenanced.

…

Money is a lubricant of commerce, according to this view, which allows people to avoid the inconveniences of barter; but money doesn’t shape economic activity. As Keynes’s Cambridge contemporary Arthur Pigou expressed it, ‘money is a veil behind which the action of real economic forces is concealed.’3 The claim that interest is determined by real factors alone is embedded in the canonical model used by central bankers. Interest rates in their model derive from demographics, savings and the profitability of investment, more or less as Hume envisaged. Despite a professed concern with ‘real’ economic factors, in their modelled world there are no manias, panics or crashes, and no popular delusions and the madness of crowds.

…

H., 242 Draghi, Mario, 61, 122–3, 145, 146, 147, 240, 293, 305 Drucker, Peter, 163 Dudley, William, 238 Dugas, Laurent, 56 Dumoulin, Charles, 25 Dutch Republic, 13, 33, 35–6, 39, 49, 63, 68 Dutot, Nicholas, 53–4, 57 East India Company, 33, 36–7, 37*, 53, 70 Easterly, William, 189–90 ecological systems, 154–5 economic growth: and Borio’s thinking, 134, 135–9; Brazilian ‘miracle’, 257–8; and ‘bubble economy’ concept, 183–7; during deflationary periods, 100–101; and digital technologies, 127–8, 151–2, 176–7; and Draghi’s policy at ECB, 146–8; and Fed’s easy money policy, 111, 112, 115, 124, 152–3, 182–3, 238; and global interest rates prior to crisis, 118, 135; and globalization, 260–61; in Great Depression era, 142–3; and Hayek, 296, 298; and inequality, 203–6, 216–17, 237, 299; and inflation, 108, 108*; and inflation targeting, 123; in Japan of 1980s, 105–8; in Japan of 1990s, 100–101, 146, 147; led by finance, 266; and meaning of ‘wealth’, 179–82, 193–5; negative impact of building booms, 135–6, 144–5, 148; and Piketty’s theory, 216–17; in post-crisis Iceland, 300–301; productivity collapse in post-crisis decade, 150–51, 152–3; and reduced interest rates after a bubble, 114, 136, 138, 145–6; relation to interest rates, xxiv, xxv, 10, 12, 44, 89, 124–9, 141, 162, 237–8; secular stagnation concept, 77, 124–9, 131, 132–9, 151, 205–6; slow recovery from Great Recession, 124–5, 126–9, 131–2, 150–53, 298–9, 304; in Soviet Union of 1950s, 278; as strong after Second World War, 126, 302; as strong in 1920s USA, 89, 89–90, 108, 143; as subordinated to financialization, 162–71, 182–3, 203–6, 237, 260; vast expansion in China, 265–74, 275–82, 283–9 economic models: canonical model used by central banks, 118, 131, 153*, 207; and demographics, 127, 131; distributional issues as suppressed in, 207; ignoring of resource misallocations, 153*; no place for money and credit in, 118; and perceptions of risk, 230; and productivity puzzle, 151; rational actors/perfect foresight assumptions, 118; unreal reality of academic models, 138, 207 The Economist, 63, 67, 71–2, 73, 77 EDF (French utility), 225 Edmunds, John C., 181 Egypt, 77, 78, 255, 262 Einstein, Albert, 8 Elizabeth II, Queen, 114 Ellington Capital Management, 223 Emden, Paul, 80* emerging markets: Brazilian crash (2012–13), 257–8; BRICs, 254–5, 257–8; capital controls return after 2008, 262, 291; capital flight from (starting 2015), 262, 285–6; demand for industrial commodities, 128; epic corruption scandals, 258; and extended supply chains, 261; flooding across South East Asia (2010), 255; ‘Fragile Five’, 258–9; growth of foreign exchange reserves, 252, 253, 254–5, 256; impact of ultra-low interest rates on, xxiii, 253–60, 262–3; international carry Trade, 137, 237–8; overheating during 2010, 255, 256; post-crisis capital flows into, xxiii, 253–9, 262–3; and recent phase of globalization, 260–61; recovery from 2008 crisis, 124; and savings glut hypothesis, 129, 268–9; ‘second phase of global liquidity’ after 2008 crisis, 253–9, 262–3; and taper tantrum (June 2013), xxiii, 137, 239, 256–7, 259, 263; Turkish debt, 258–60; vulnerability to US monetary policy, 137, 262–3, 267–8 see also China employment/labour markets, xx, 151–2, 240, 260–61, 260*, 296; after 2008 crisis, 210, 211; new insecurity, 211, 298 Erdogan, Recep Tyyip, 259 European Central Bank (ECB), 144, 145, 147, 239, 240, 293; inflation targeting, 119, 120, 122–3; and quantitative easing, 146, 241, 242; sets negative rate, 147, 192–3, 244, 299 European Union, 187, 241, 262 Eurozone, 124, 150–51, 226; and political sovereignty, 293, 293†; sovereign debt crisis (from 2010), 144–8, 226, 238, 239, 241, 273, 293 Evans, David Morier, 73 Evelyn, John, 36, 45 Evergrande (Chinese developer), 279, 288, 310 executive compensation schemes, 152, 162, 163–4, 170, 204, 206, 207 Extinction Rebellion, 201 ExxonMobil, 166 Fang’s Money House, Wenzhou, 281–2 farming: agricultural cycle, 11, 14, 88; and ‘Bank of John Deere’, 167; barley loans in ancient Mesopotamia, 5–6, 6*, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14; bubbles in post-crisis decade, 173; in China, 283; and language of interest, 4–5; loans related to consumption, 6, 25; US deflation of 1890s, 99 Federal Reserve, US: asymmetrical approach to rates, 136–7; as carry trader, 222; cognitive dissonance in, 118–19; Federal Reserve Act (1914), 83; ‘forgotten depression’ (1921), 84, 86, 100, 143; forward guidance policy, 131*, 133, 238, 239, 240, 241; and Gold Exchange Standard, 85, 87, 90*; the ‘Greenspan put’, 111, 186; impact on foreign countries, 137, 239, 240–41, 255–6, 259, 262–3, 267–8, 285; inflation targeting, 119, 120, 241; Long Island meeting (1927), 82–3, 88, 92; mandates of, 240, 262; and March 2020 crash, 305–6; Objectives of Monetary Policy (1937), 97; Open Market Committee (FOMC), 109, 112–13, 115†, 120, 164, 228, 238, 239, 240; Operation Twist (2011), 131*, 238; parallel with US Forest Service, 154–5; and post-Great War inflation, 84; as the ‘price of leverage’, xxi–xxii; quantitative easing by, 12*, 76, 131*, 137, 175, 215, 228, 236, 238, 239–40, 241; raised rates announcement (2015), 138, 239; reaches ‘zero lower bound’ (2008), 243–4; response to 1929 Crash, 98, 100, 101, 108; suggested as responsible for 2008 crisis, 116–17, 118–19, 155, 204, 226–7; TALF fund, 175; taper tantrum (June 2013), xxiii, 137, 239, 256–7, 259, 263; ultra-easy money after 2008 crisis, xxi, 60, 124, 131–8, 146, 149, 152–5, 181–3, 206–17, 221–4, 230, 235–41, 243–4, 262, 291–2; Paul Volcker runs, 108–9, 145; Janet Yellen runs, 120 see also Bernanke, Ben; Greenspan, Alan Feldstein, Martin, 119 Ferri, Giovanni, 277* Fetter, Frank, 30 Field, Alexander, The Great Leap Forward, 142–3 financial crisis (2008): accelerates financialization, 182–3; and complex debt securities, 116, 117–18, 231; ‘crunch porn’ on causes of, 114; economists who anticipated crisis, 113–14, 132; failure of unconventional monetary policies after, xxi, xxii, 43–4, 291–4, 298–9, 301–3; Fed’s monetary policy as suggested cause, 116–17, 118–19, 155, 204, 226–7; generational impact of, 211–12, 213; as ‘giant carry trade gone wrong’, 253–5; global causes of, 117–18; Icelandic recovery from, 301–2; and inequality, 204, 205–17, 299; interest at lowest level in five millennia during, xxi, 243–4, 247; Law’s System compared to, 49, 60–61; low/stable inflation at time of, 134, 135; monetary policy’s role in run-up downplayed, 115–16, 115*, 115†; and quoting of Bagehot, 76; recovery of lost industrial output after, 124; regulatory interpretation of, 114–15, 117; and return of the state, 292–5, 297, 298; return to ‘yield-chasing’ after, 221–6, 230–31, 233–4, 237–8; the rich as chief beneficiaries of, 206–10; savings glut hypothesis, 115–16, 117, 126, 128–9, 132, 191, 252, 268–9; ‘second phase of global liquidity’ after, 253–9, 262–3; unwinding of carry trades during, 221, 227; warnings from BIS economists before, 113–14, 131–4, 135–9 see also Great Recession financial derivatives market, 225–6 financial engineering: buybacks, 53, 152, 163–6, 167, 169, 170–71, 183, 224; crowding out of real economy by, 158–9, 160, 166–71, 182–3, 185, 237; ‘funding gap’ as impetus, 164, 176–7, 291; merger ‘tsunami’ after 2008 crisis, 160–63, 161*, 168–70, 237, 298; ‘promoter’s profit’ concept, 158–9, 160, 161, 164; and ‘shareholder value’, 163–6, 167, 170–71; Truman Show as allegory for bubble economy, 185–7; use of leverage, 111, 116, 149, 155, 158–71, 204, 207, 223, 237, 291; zaitech in Japan, 106, 182, 185 financial repression: in China, 264–5, 265*, 266–81, 268*, 283, 286–9, 292; and inequality, 287–8; McKinnon coins term, 264; political aspects, 265, 265*, 286–9, 292; returns to West after 2008 crisis, 291–3; after Second World War, 290–91, 302 financial sector: bond markets as ‘broken (2014), 227; complex securitizations, 116, 117–18, 221, 227, 231; decades-long bull market from early 1980s, 203–4; economics as fundamentally monetary, 132, 138–9; Edmunds’ ‘New World Wealth Machine’, 181–2; expansion in 1920s USA, 203; finance as leading growth, 266; financial mania of 1860s, 72–4, 75–6; fixed-income bonds, 68–9, 193, 219, 222, 225, 226; foreign securities/loans, 66, 77–8, 91; investment trusts appear (1880s), 79; liquidity traps, 114; mighty borrowers within, 202; profits bubble in post-crisis USA, 183, 183†, 185, 211; robber baron era in USA, 156–9, 203; stability as destabilizing, 82, 143, 233, 263, 285; stock market bubble in post-crisis decade, 175–7, 176*; trust companies in US, 83–4, 84*; US bond market ‘flash crash’ (2014), 138; and volatility, 153, 228–30, 233, 234, 254, 304, 305; volatility as asset class, 229–30, 229*, 233, 234, 304, 305; ‘Volmageddon’ (5 February 2018), 229–30, 234 see also banking and entries for individual institutions/events financial system, international: Asian crisis, 114, 252, 278; Basel banking rules, 232; Borio on ‘persistent expansionary bias’, 262–3; complex mortgage securities, 116, 117–18; crash (12 March 2020), 304–6; ‘excess elasticity’ of, 137; global financial imbalances, 137, 138; Louvre Accord (1987), 105–6; stock market crash (October 1987), 106, 110–11, 229 financialization, 162–71, 182–3, 185, 203–8, 237 Fink, Larry, 209, 246 Finley, Sir Moses, Economy and Society in Ancient Greece (1981), 18* fire-fighting services, 154–5 First World War, 84, 85 Fisher, Irving: and debt-deflation, 98–9, 100, 119, 280; first to refer to ‘real’ interest rate, 88–9, 219*; founds Stable Money League (1921), 87, 96; and Gesell’s rusting money, 243, 246; on interest, 29–30, 82, 189, 189*, 201; losses in 1929 crash, 94; monetarist view of 1929 Crash, 98–9, 100, 101, 108; ‘money illusion’ concept, 87*; on nature’s production, 4–5; on negative interest, 246; The Theory of Interest, xxiv, xxv, xxvi*, 16, 173 Fisher, Peter, 194 Fisher, Richard, 164 Fitzgerald, F.

The Behavioral Investor

by

Daniel Crosby

Published 15 Feb 2018

No matter how unfair the split, the money on offer wasn’t yours to begin with and you’d be leaving with more than you started with. Yet even knowing what ought to be done, it is hard to move beyond our emotional responses to money and our thoughts around fairness. Logic, it would seem, has very little to do with it. Canonical models of economics assume that money has indirect utility, that is, it is only as good as the things we can hope to buy with it, but neuroscience tells a different story. Neural evidence suggests that money produces the same sort of dopaminergic rewards as other primary reinforcers such as beautiful faces, funny cartoons, sports cars and drugs.

…

Thinking is hard How many decisions would you guess that you make in a given day? Take a second, mentally walk through your day and hazard a guess. Most people I ask this question land somewhere around 100, which is way off – try 35,000.35 That’s right, you make 35,000 decisions per day. Canonical models of decision-making deal with two types of decisions – certain (i.e., with a known set of alternatives with given outcomes) and uncertain (just the opposite). In theory, decisions made under conditions of certainty involve ranking the known alternatives and choosing the most preferred option, simple enough.

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by

David G. Blanchflower

Published 12 Apr 2021

What theoretical backing can we give to our claims to observe underemployment and overemployment, when the so-called “canonical” model of Pencavel (1986) suggests that workers are free to choose their hours of work, given the wage rate? In answer to this, first, we note that more recently Pencavel (2016) himself acknowledged that this model where workers select their hours, dominant in the literature since Lewis (1957), neglects the role of employer preferences in hours determination.6 Even though Lewis himself stepped back from this position (1969), acknowledging that the preferences of employers are neglected in the canonical model, the assumption that workers select from a continuum of hours, while treating the wage rate as exogenous, continues to dominate research and teaching.

…

However, if employers are monopsonistic, they may be able to vary workers’ hours in response to fluctuations in demand even if there is little joint investment in firm-specific skills.8 Hours variations are invariably less expensive than rescaling the workforce, and firms may use such variations when they perceive the probability of inefficient separations is low. Bhaskar, Manning, and To (2002) suggest a number of explanations as to why labor markets are typically “thin,” giving employers a degree of market power. Manning, while also lamenting the preeminence of the canonical model, argues that under monopsony, utility-maximizing employees may be displaced from their supply curve and would express a desire to increase or decrease their current hours at the current wage rate (2003, 228). Using data from the British Household Panel Survey for the period 1991–98, he shows that the desire to reduce hours substantially exceeded desired hours increases.

Big Data and the Welfare State: How the Information Revolution Threatens Social Solidarity

by

Torben Iversen

and

Philipp Rehm

Published 18 May 2022

We present the argument in three steps: (i) We begin by introducing the classic asymmetric information case and show that it leads to majority support for public provision under most realistic assumptions; (ii) we then turn to the symmetric information case and show that when information is plentiful and can be credibly shared with insurers, a majority may prefer market provision (or a public system that mimics markets); (iii) lastly, we show that when market solutions are blocked, whether for political or economic reasons, preferences over public provision will become polarized as information increases. The model is developed from the perspective of individuals’ demand for insurance, and it will be readily recognizable to readers familiar with canonical models of demand for public insurance in political science. For readers familiar with the standard economic model of private insurance markets, Appendix 2.1 shows the correspondence between that model and the one presented in the main text. For every result, Appendix 2.2 shows that the insurer’s budget constraint is satisfied.

…

We present the argument in three steps: (i) We begin by introducing the classic asymmetric information case and show that it leads to majority support for public provision under most realistic assumptions; (ii) we then turn to the symmetric information case and show that when information is plentiful and can be credibly shared with insurers, a majority may prefer market provision (or a public system that mimics markets); (iii) lastly, we show that when market solutions are blocked, whether for political or economic reasons, preferences over public provision will become polarized as information increases. The model is developed from the perspective of individuals’ demand for insurance, and it will be readily recognizable to readers familiar with canonical models of demand for public insurance in political science. For readers familiar with the standard economic model of private insurance markets, Appendix 2.1 shows the correspondence between that model and the one presented in the main text. For every result, Appendix 2.2 shows that the insurer’s budget constraint is satisfied.

…

We present the argument in three steps: (i) We begin by introducing the classic asymmetric information case and show that it leads to majority support for public provision under most realistic assumptions; (ii) we then turn to the symmetric information case and show that when information is plentiful and can be credibly shared with insurers, a majority may prefer market provision (or a public system that mimics markets); (iii) lastly, we show that when market solutions are blocked, whether for political or economic reasons, preferences over public provision will become polarized as information increases. The model is developed from the perspective of individuals’ demand for insurance, and it will be readily recognizable to readers familiar with canonical models of demand for public insurance in political science. For readers familiar with the standard economic model of private insurance markets, Appendix 2.1 shows the correspondence between that model and the one presented in the main text. For every result, Appendix 2.2 shows that the insurer’s budget constraint is satisfied.

The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science

by

Paul Krugman

Published 18 Feb 2010

The standard response of economists is that to blame the financial markets in such a situation is to shoot the messenger, that a crisis is simply the market’s way of telling a government that its policies aren’t sustainable. You may wonder at the abruptness with which that message is delivered. But that, says the canonical model, is simply part of the logic of the situation. To see why, forget about currencies for a minute, and imagine a government trying to stabilize the price of some commodity, such as gold. The government can do this, at least for a while, if it starts with a sufficiently large stockpile of the stuff: All it has to do is sell some of its hoard whenever the price threatens to rise about the target level.

Understanding Exposure, Fourth Edition: How to Shoot Great Photographs With Any Camera

by

Bryan Peterson

Published 15 Mar 2016

Both images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 24mm, f/16 for 4 sec., ISO 200 MULTIPLE EXPOSURES If taking a single exposure of a scene or subject doesn’t quite do it for you, how about taking two exposures? Or why not seven or nine exposures of the same subject, stacking all the exposures one on the other and within seconds collapsing them all into a single image? You can do all this in camera with most Nikon cameras, a few of the Pentax models, and of late a few of the Canon models. Get out your manual if you have trouble finding this feature, because once you do, you can explore the many creative possibilities it affords. I like to inject a bit of implied movement into my multiple exposures. To do this you simply point your camera at the subject, choose the appropriate aperture (f/16 or f/22 for storytelling, f/4 or f/5.6 for isolation, or f/8 or f/11 for “who cares?”)

Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth

by

Juliet B. Schor

Published 12 May 2010

Chapter Three ECONOMICS CONFRONTS THE EARTH Both the original Limits theorists of the 1970s and the expanding sustainability movement of the 1990s found one group particularly reluctant to address the threat of business-as-usual: mainstream economists. A fateful methodological choice made by the discipline helps to understand why. The canonical models used by the mainstream are addressed to what happens within markets, rather than to economic dynamics more broadly. Because air, water, and many natural resources are neither owned nor priced, the effects of economic activity on their health and functioning do not fall within the purview of the standard treatments.

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by

Tim Harford

Published 1 Jan 2008

The original paper is Adam B. Jaffe, Manuel Trajtenberg, and Rebecca Henderson, “Geographic Localization of Knowledge Spillovers as Evidenced by Patent Citations,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, no. 3(August 1993): 577–98. I also interviewed Adam Jaffe in November 2006. To see the reason: The canonical model of this argument is the paper that launched the so-called New Economic Geography, Paul Krugman’s elegant “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography,” Journal of Political Economy 99, no. 3(June 1991): 483–99. This and many other Krugman academic papers are available at math.stanford.edu/~lekheng/ krugman/index.html.

Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net's Impact on Our Minds and Future

by

John Brockman

Published 18 Jan 2011

But this model, too, probably severely underestimates the number of systems constituting thought. If a confederacy of systems constitutes thought, is the number closer to 4 or 400? I don’t think we have much basis today for answering one way or another. Consider also the tendency to treat thought as a logic system. The canonical model of cognitive science views thought as a process involving mental representations, and rules for manipulating those representations (a language of thought). These rules are typically thought of as a logic, which allows various inferences to be made and allows thought to be systematic (i.e., rational).

Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer-And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class

by

Paul Pierson

and

Jacob S. Hacker

Published 14 Sep 2010

A Brief History of Democratic Capitalism 1 The two quotes are from Michael Thompson, The Politics of Inequality: A Political History of the Idea of Economic Inequality (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 25, 45; see also Sean Wilentz, “America’s Lost Egalitarian Tradition,” Daedalus, 131, no. 1 (Winter 2002): 66–80. 2 Thompson, The Politics of Inequality, 27, 45, 47–48. 3 James Madison, “Federalist #10: The Utility of the Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection,” in The Federalist Papers, http://www.constitution.org/fed/federa10.htm, originally published in Daily Advertiser, November 22, 1787. 4 James Madison, “Federalist #39: Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles,” in The Federalist Papers, http://www.constitution.org/fed/federa39.htm, originally published in Independent Journal, January 16, 1788. 5 Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2005), 17. 6 John Adams, “Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States,” in The Founders’ Constitution, vol. 1, Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986). 7 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. and ed. by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 201. 8 Ibid. 9 The canonical model is Allen H. Meltzer and Scott F. Richards, “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government,” Journal of Political Economy 89, no. 5 (1981): 914–927. For a nice review, see Jo Thori Lind, “Why Is There So Little Redistribution?” Nordic Journal of Political Economy 31 (2005): 111–125. 10 Quoted in Steve Fraser, Wall Street: A Cultural History (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 158. 11 Michael Waldman, ed., My Fellow Americans: The Most Important Speeches of America’s Presidents, from George Washington to George W.

The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money

by

Bryan Caplan

Published 16 Jan 2018

To ease my intellectual conscience, I now confess my greatest doubts about my efforts. Completion probabilities. Probabilities are definitely low, especially for weaker students, but the evidence is surprisingly thin. I end up relying on one model for high school and one for the bachelor’s. I wish I had ten canonical models of completion probability for each educational level, but to the best of my knowledge, they aren’t accessible. How school and work feel. There isn’t enough research on how students emotionally experience school versus work. Most adults have done both for years, but few researchers seriously compare the two.

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by

Scott E. Page

Published 27 Nov 2018

That exercise would undoubtedly reveal contingencies. Each learning rule would result in efficient outcomes for some games but not for others. Each learning rule would also vary in the contexts in which it accurately describes behavior. Hence, we advocate many models. In this chapter, we covered two canonical models. Each includes only a few moving parts. Our goal was to provide a gentle introduction to a large and exciting literature. By adding more details to either learning model, we would better fit experimental and empirical data. Recall that in the reinforcement learning model, individuals add or subtract weight to an alternative or action depending on whether its reward (payoff) exceeds the aspiration level.

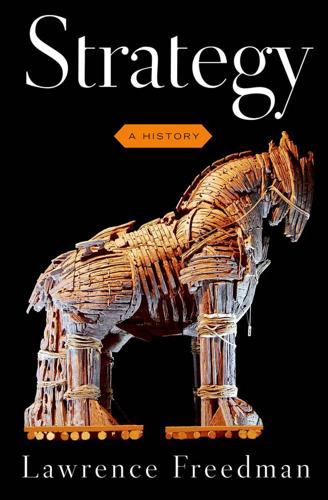

Strategy: A History

by

Lawrence Freedman

Published 31 Oct 2013

Playing these games with children also demonstrated that altruism was something to be learned during childhood.20 As they grew older, most individuals turned away from the self-regarding decisions anticipated by classical economic theory and become more other-regarding. The exceptions were those suffering from neural disorders such as autism. In this way, as Angela Stanton caustically noted, the canonical model of rational decision-making treated the decision-making ability of children and those with emotional disorders as the norm.21 The research confirmed the importance of reputation in social interactions.22 The concern with influencing another’s beliefs about oneself was evident when there was a need for trust, for example, when there were to be regular exchanges.

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach

by

Stuart Russell

and

Peter Norvig

Published 14 Jul 2019

In fact, the principal result in Gaifman (1964a) is the construction of a single probability model requiring 1) a probability for every possible ground sentence and 2) probability constraints for infinitely many existentially quantified sentences. One solution to this problem is to write a partial theory and then “complete” it by picking out one canonical model in the allowed set. Nilsson (1986) proposed choosing the maximum entropy model consistent with the specified constraints. Paskin (2002) developed a “maximum-entropy probabilistic logic” with constraints expressed as weights (relative probabilities) attached to first-order clauses. Such models are often called Markov logic networks or MLNs (Richardson and Domingos, 2006) and have become a popular technique for applications involving relational data.