colonial exploitation

description: refers to the historical practice where colonial powers extracted natural resources and exploited indigenous populations for economic gain.

58 results

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India

by

Shashi Tharoor

Published 1 Feb 2018

The traditional British view of wealth based it on the ownership of land, which, through its solidity, connoted an earthy stability, and since land was held for a long time, reflected hierarchy and implied a sense of permanence. This had changed somewhat thanks to the advent of the mercantile classes, but the Pitt Diamond represented a dramatically alternative model, based on something far more adventurous—colonial exploits, if not exploitation. The owners of these diamonds escaped the confinement of traditional sources of wealth for something that could be acquired by colonial enterprise rather than traditional inheritance. Fifteen years after he had brought the diamond from India, Thomas Pitt sold it to the Regent of France, the Duc d’Orléans, for the princely sum of £135,000, almost six times what he had paid for it.

…

There is an ironic footnote to the issue of Britain’s economic exploitation of India, in these days of Scottish nationalism and febrile speculation about the future of the Union. It is often forgotten what cemented the Union in the first place: the loaves and fishes available to Scots from participation in the colonial exploits of the East India Company. Before Union with England, Scotland had attempted, but been singularly unsuccessful at, colonization, mainly in Central America and the Caribbean. Once Union came, India came with it, along with myriad opportunities. A disproportionate number of Scots were employed in the colonial enterprise, as soldiers, sailors, merchants, agents and employees.

…

Assam tea proved superior to the Chinese imports and more palatable to the British housewife. In the 1830s, the East India Company traded about 31.5 million lbs. (14 million kilos) of Chinese tea a year; today India alone produces nearly 300 million kilos. But even tea was not exempt from colonial exploitation: the workers laboured in appalling conditions for a pittance, while all the profits, of course, went to British firms. Early in the twentieth century, the remarkable anti-imperialist Sir Walter Strickland wrote bitterly in the preface to his now-out-of-print volume The Black Spot in the East: ‘Let the English who read this at home reflect that, when they sip their deleterious decoctions of tannin…they too are, in their degree, devourers of human flesh and blood.

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by

Edward Luce

Published 20 Apr 2017

By one recent historical measure, China and India in 1750 produced three-quarters of the world’s manufactures. On the eve of the First World War their share had dropped to just 7.5 per cent.6 Economic historians called it the Age of Divergence. Much of the East’s sharp decline – perhaps too much – has been blamed on the direct effects of colonial exploitation. The British East India Company, for example, suppressed Indian textile production, which had led the world. Indian silks were displaced by Lancashire cotton. Chinese porcelain was supplanted by European ‘china’. Both suffered from variations on what Britain later called Imperial Preference, which forced them to export low-value raw materials to Britain, and import expensive finished products, thus keeping them in permanent deficit.

…

advertising, 65–6, 178 Afghanistan, 80 Africa: Chinese investment in, 32, 84; economic growth in, 21, 31, 32; future importance of, 200–1; and liberal democracy, 82, 83, 183; migration from, 140, 181; slave trade, 23, 55, 56 African-Americans, 104 age demographics, 34–5, 155, 156; ageing populations, 39; baby boom years, 39, 121; and gig economy, 64; life expectancy, 38, 58, 59, 60; millennials, 40–1, 121–2; and support for democracy, 121–2; and voter turnout, 103–4 Airbnb, 63 Albright, Madeleine, 6 American Revolution, 9 Andorra, 72 Andreessen, Marc, 61 Apple, 27, 31, 59, 60, 156 Arab Spring, 12, 82 Arab world, 202 Arendt, Hannah, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 128 Aristotle, 138, 200 artificial intelligence, 13, 34, 51–5, 56, 60–2 Asian Development Bank, 84 Asian economies, 21–2, 162; as engine of global growth, 21, 30, 31, 32; and Industrial Revolution, 23–4; and optimism, 202; of South Asia, 31; see also China; India Asian flu crisis (1997), 29 Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), 84 Attlee, Clement, 90 Australia, 84, 160, 167, 175 Austria, 15–16, 116 autocracy: and America’s post-9/11 blunders, 80–1, 85, 86; authoritarian nature of Trump, 133, 169, 171, 178–9; China as, 78, 80, 83–6, 159–60, 165, 201; and end of Cold War, 5, 78–9; and First World War, 115; and Great Recession, 83–4; and illiberal democracy, 204; myth of as more efficient, 170–1; popular demagogues, 137; rising support for, 11, 73, 82–3, 122 automation: and Chinese workforce, 62, 169; communications technology, 13, 52–5, 56–7, 59–60, 61–6, 67–8 see also digital revolution; and education, 197, 198; and Henry Ford, 66–7; political responses to, 67–8; steam revolution, 24, 55–6; techno-optimists, 52, 60; in transport, 54, 55, 56–7, 58, 59, 61 Bagehot, Walter, 115 Baker Institute, 68 Baldwin, Richard, 25, 27, 61 Bangladesh, 32 bank bail-outs, 193 Bannon, Steve, 130, 148, 173, 181–2 Belgium, 140 Bell, Daniel, 37 Berlin Wall, fall of (1989), 3–5, 6, 7, 74, 77 Bernstein, Carl, 132 Berra, Yogi, 57 Bhagwati, Jagdish, 159 Bismarck, Otto von, 42, 78, 120, 156, 161 Black Death, 25 Blair, Tony, 45, 89–90, 91 Blum, Léon, 116 Boer War (1899-1902), 155, 156 Bortnikov, Alexander, 6 Botswana, 82 Brazil, 29 Brecht, Bertolt, 86, 87 Breitbart News, 148 Brexit, 15, 73, 88, 92, 98, 101, 104, 119, 120, 163; UKIP’s NHS spending claim, 102; urban–hinterland split in vote, 47, 48, 130; xenophobia during campaign, 100–1 Britain: elite responses to Nazi Germany, 117; foreign policy goals, 179; gig economy, 63; growth of inequality in modern era, 43, 46, 47, 48, 50–1; history in popular imagination, 163; Imperial Preference, 22; London’s elites, 98–100, 130; nineteenth-century franchise extension, 114–15; policy towards China, 164; rapid expansion in nineteenth century, 24; and rise of Germany, 156, 157; rising support for authoritarianism, 122; separatism within, 140; Thatcher’s electoral success, 189–90 British East India Company, 22 British National Party (BNP), 100 Brown, Gordon, 99 Brownian movement, 172 Bryan, William Jennings, 111 Brynjolfsson, Erik, 60 Buffet, Warren, 199 Bush, George W., 31, 73, 79–81, 103, 156, 157, 163, 165, 182 Bush Republicans, 189 Cameron, David, 15, 92, 98, 99–100 Carnegie, Andrew, 42–3 Cherokee Indians, 114, 134 Chicago, 48 China: as autocracy, 78, 80, 83–6, 159–60, 165, 201; circular view of history, 11; colonial exploitation of, 20, 22–3, 55; decoupling of economy from West (2008), 29–30, 83–4; democracy activists in, 86, 140; entry to WTO (2001), 26; exceptionalism, 166; expulsion of Western NGOs, 85; future importance of, 200–1; and global trading system, 19–20, 26–7; Great Firewall in, 129; handover of Hong Kong (1997), 163–4; history in popular imagination, 163–4; hostility to Western liberalism, 84–6, 159–60, 162; and hydrogen bomb, 163; and Industrial Revolution, 22, 23–4; internal migration in, 41; investment in developing countries, 32, 84; military expansion, 157, 158; as nuclear power, 175; Obama’s trip to (2009), 159–60; political future of, 168–9, 202; pragmatic development route, 28, 29–30; pre-Industrial Revolution economy, 22; rapid expansion of, 13, 20–2, 25–8, 30, 35, 58, 157, 159; and robot economy, 62; Shanghai Cooperation Organization, 80; Trump’s promised trade war, 135, 145, 149; and Trump’s victory, 85–6, 140; US naval patrols in seas off, 148, 158, 165; US policy towards, 25–6, 145–6, 157–61, 165; US–China war scenario, 145–53, 161; in Western thought, 161–2; Xi’s crackdown on internal dissent, 168; Zheng He’s naval fleet, 165–6 China Central Television (CCTV), 84, 85 Christianity, 10, 105 Churchill, Winston, 98, 117, 128, 169 cities, 47–51, 130 class: creeping gentrification, 46, 48, 50–1; emerging middle classes, 21, 31, 39, 159; in Didier Eribon’s France, 104–10; Golden Age for Western middle class, 33–4, 43; Hillaryland in USA, 87–8; ‘meritocracy’, 43, 44–6; mobility as vanishing in West, 43–6; move rightwards of blue-collar whites, 95–9, 102, 108–10, 189–91, 194–5; poor whites in USA, 95–6, 112–13; populism in late nineteenth century, 110–11; and post-war centre-left politics, 89–92, 99; ‘precariat’ (‘left-behinds’), 12, 13, 43–8, 50, 91, 98–9, 110, 111, 131; and Trump’s agenda, 111, 151, 169, 190; urban liberal elites, 47, 49–51, 71, 87–9, 91–5, 110, 204; West’s middle-income problem, 13, 31–2, 34–41 Clausewitz, Carl von, 161 Clinton, Bill, 26, 71, 73, 90, 97–8, 157–9 Clinton, Hillary, 15, 16, 47, 67, 79, 160, 188; 2016 election campaign, 87–8, 91–4, 95–6, 119, 133; reasons for defeat of, 94–5, 96–8 Cold War: end of, 3–5, 6, 7, 74, 77, 78, 117, 121; nuclear near misses, 174; in US popular imagination, 163; and Western democracy, 115–16, 117, 183 Colombia, 72 colonialism, European, 11, 13, 20, 22–3; anti-colonial movements, 9–10; and Industrial Revolution, 13, 23–5, 55–6 Comey, James, 133 communism, 3–4, 5, 6, 105–8, 115 Confucius Institutes, 84 Congress, US, 133–4 Copenhagen summit (2009), 160 Coughlin, Father, 113 Cowen, Tyler, 40, 50, 57 Crick, Bernard, 138 crime, 47 Crimea, annexation of (2014), 8, 173 Cuba, 165 Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), 165, 174 cyber warfare, 176–8 Cyborg, 54 D’Alema, Massimo, 90 Daley, Richard, 189 Danish People’s Party, 102 Davos Forum, 19–20, 27, 68–71, 72–3, 91, 121 de Blasio, Bill, 49 de Gaulle, Charles, 106, 116 de Tocqueville, Alexis, 38, 112, 126–7 democracy, liberal: as an adaptive organism, 87; and America’s Founding Fathers, 9, 112–13, 123, 126, 138; and Arab Spring, 82; Chinese view of US system, 85–6; communism replaces as bête noire, 115; concept of ‘the people’, 87, 116, 119–20; damaged by responses to 9/11 attacks, 79–81, 86, 140, 165; and Davos elite, 68–71; de Tocqueville on, 126–7; declining faith in, 8–9, 12, 14, 88–9, 98–100, 103–4, 119–23, 202–3; demophobia, 111, 114, 119–23; economic growth as strongest glue, 13, 37, 103, 201–2; efforts to suppress franchise, 104, 123; elite disenchantment with, 121; elite fear of public opinion, 69, 111, 118; failing democracies (since 2000), 12, 82–3, 138–9; and ‘folk theory of democracy’, 119, 120; Fukuyama’s ‘End of History’, 5, 14, 181; and global trilemma, 72–3; and Great Recession, 83–4; and Hong Kong, 164; idealism of Rousseau and Kant, 126; illiberal democracy concept, 119, 120, 136–7, 138–9, 204; in India, 201; individual rights and liberty, 14, 97, 120; late twentieth century democratic wave, 77–8, 83; and mass distraction, 127, 128–30; need for regaining of optimism, 202–3; need to abandon deep globalisation, 73–4; nineteenth-century fear of, 114–15; and plural society, 139; popular will concept, 87, 118, 119–20, 126, 137–8; post-Cold War triumphalism, 5, 6, 71; post-war golden era, 33–4, 43, 89, 116, 117; post-WW2 European constitutions, 116; and ‘precariat’ (‘left-behinds’), 12, 13, 43–8, 50, 91, 98–9, 110, 111, 131; the rich as losing faith in, 122–3; Russia’s hostility to, 6–8, 79, 85; space for as shrinking, 72–3; technocratic mindset of elites, 88–9, 92–5, 111; Trump as mortal threat to, 97, 104, 111, 126, 133–6, 138, 139, 161, 169–70, 178–84, 203–4; and US-led invasion of Iraq (2003), 8, 81, 85; Western toolkit for, 77–9; see also politics in West Diamond, Larry, 83 digital revolution, 51–5, 59–66, 67–8, 174; cyber-utopians, 52, 60, 65; debate over future impact, 56; and education, 197, 198; exponential rate of change, 170, 172, 197; internet, 34, 35, 127, 128, 129–30, 131, 163; internet boom (1990s), 34, 59; and low productivity growth, 34, 59, 60; as one-sided exchange, 66–7; and risk-averse/conformist mindset, 40 diplomacy and global politics: annexation of Crimea (2014), 8, 173; China’s increased prestige, 19–20, 26–8, 29–30, 35, 83–5, 159; declining US/Western hegemony, 14, 21–2, 26–8, 140–1, 200–1; existential challenges in years ahead, 174–84; multipolarity concept, 6–8, 70; and nation’s popular imagination, 162–3; parallels with 1914 period, 155–61; and US ‘war on terror’, 80–1, 140, 183; US–China relations, 25–6, 145–6, 157–61, 165; US–China war scenario, 145–53, 161; US–Russia relations under Obama, 79 Doha Round, 73 drugs and narcotics, 37–8 Drutman, Lee, 68 Dubai, 48 Durkheim, Émile, 37 Duterte, Rodrigo, 136–7, 138 economists, 27 economy, global see global economy; globalisation, economic; growth, economic Edison, Thomas, 59 education, 42, 44–5, 53, 55, 197, 198 Egypt, 82, 175 electricity, 58, 59 Elephant Chart, 31–3 Enlightenment, 24, 104 entrepreneurialism, decline of in West, 39–40 Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip, 137 Eribon, Didier, 104–10, 111 Ethiopia, 82 Europe: ‘complacent classes’ in, 40; decline of established parties, 89; geopolitical loss, 141; growth of inequality in modern era, 43; identity politics in, 139–40; migration crisis, 70, 100, 140, 180–1; nationalism in, 10–11, 102, 108–9; nineteenth-century diplomacy, 7–8, 155–6, 171–2; post-war constitutions in, 116; Putin’s interference in, 179, 180; as turning inwards, 14 European Commission, 118, 120 European Union, 72, 117–19, 139–40, 179–80, 181, 201; see also Brexit Facebook, 39, 54, 67, 178 fake news, 130, 148, 178–9 Farage, Nigel, 98–9, 100, 184 fascism, 5, 77, 97, 100, 117 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), 131–2, 133 Felt, Mark, 131–2, 134 financial crisis, global (2008), 27, 29, 30, 91; Atlantic recession following, 30, 63–4, 83–4 financial services, 54 Financial Times, 136, 200 Finland, 139 First World War, 115, 154–5 Flake, Jeff, 134 Florida, Richard, 47, 49, 50, 51 Flynn, Michael, 148, 149 Foa, Roberto Stefan, 123 Ford, Henry, 66–7 Foucault, Michel, 107 France, 15, 37, 63, 102, 104–10, 116; 1968 Paris demonstrations, 188; French Revolution, 3 Franco, General Francisco, 77 Franco-German War (1870–1), 155–6 Frank, Robert H., 30, 35–6, 44 Franklin, Benjamin, 204 Freelancer.com, 63 Friedman, Ben, The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, 38 Friedman, Thomas, 74 Frontex (border agency), 181 FSB, 6 Fukuyama, Francis, 12, 83, 101, 139, 193–4; ‘The End of History?’

…

(essay), 5, 14, 181 Garten, Jeffrey, From Silk to Silicon, 25 Gates, Bob, 177–8 gay marriage issue, 187, 188 gender, 57 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), 72 Genghis Khan, 25 gentrification, creeping, 46, 48, 50–1 Georgia, Rose Revolution (2003), 79 Germany, 15, 42, 43, 57, 78, 115; far-right resurgence in, 139–40; and future of EU, 180; Nazi, 116, 117, 155, 171; post-war constitution, 116; rise of from late nineteenth century, 156–7; Trump’s attitude towards, 179–80; vocational skills education, 197 gig economy, 62–5 Gladiator (film), 128–9 Glass, Ruth, 46 global economy: centre of gravity shifting eastwards, 21–2, 141; change of guard (January 2017), 19–20, 26–7; emerging middle classes, 21, 31, 39, 159; end of Washington Consensus, 29–30; fast-growing non-Western economies, 20–2; Great Convergence, 12, 13, 24, 25–33; Great Divergence, 13, 22–5; Great Recession, 63–4, 83–4, 192, 193; new protectionism, 19–20, 73, 149; ‘precariat’ (‘left-behinds’), 12, 13, 43–8, 50, 91, 98–9, 110, 111, 131; rapid expansion of China, 20–2, 25–8, 157, 159; spread of market economics, 8, 29; West’s middle-income problem, 13, 31–2, 34–41; see also globalisation, economic; growth, economic globalisation, economic: China as new guardian of, 19–20, 26–7; Bill Clinton on, 26; in decades preceding WW1, 155; Elephant Chart, 31–3; Friedman’s Golden Straitjacket, 74; Jeffrey Garten’s history of, 25; and global trilemma, 72–3; and multinational companies, 26–7; need to abandon deep globalisation, 73–4; next wave of, 32; radical impact of, 12–13; and stateless elites, 51, 71; and Summers’ responsible nationalism, 71–2; and technology, 55–6, 73, 174 Gongos (government-organised non-governmental organisations), 85 Google, 54, 67 Gordon, Robert, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, 57–8, 59–61 Graham, Lindsey, 134 Greece: classical, 4, 10, 25, 137–8, 156, 200; overthrow of military junta, 77 Greenspan, Alan, 71 growth, economic: and bad forecasting, 27; as Bell’s ‘secular religion’, 37; and digital economy, 54–5, 59, 60; Elephant Chart, 31–3; emerging economies as engine of, 21, 30, 31, 32; Golden Age for Western middle class, 33–4, 43; Robert Gordon’s thesis, 57–8, 59–61; and levels of trust, 38–9; as liberal democracy’s strongest glue, 13, 37, 103, 201–2; out-dated measurement models, 30–1; technological leap forward (from 1870), 58–9; West’s middle-income problem, 13, 31–2, 34–41 Hamilton, Alexander, 78 Harvard University, 44–5 healthcare and medicine, 35, 36, 42, 58, 59, 60, 62, 102, 103, 198 Hedges, Chris, Empire of Illusion, 125 Hegel, Friedrich, 161–2 Heilbroner, Robert, 10 Hispanics in USA, 94–5 history: 1930s extremism, 116–17; Chinese economy to 1840s, 22–3; Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’, 5, 14, 181; Great Divergence, 13, 22–5; Hobson’s prescience over China, 20–1; and inequality, 41–3; and journalists, 15; Keynes’ view, 153–5; Magna Carta, 9–10; of modern democracy, 112–17; nineteenth-century protectionism, 78; nineteenth-century European diplomacy, 7–8, 155–6, 171–2; non-Western versions of, 11; Obama on, 190; Peace of Westphalia (1648), 171; populist surge in late-nineteenth-century USA, 110–11; post-war golden era, 33–4, 43; post-war US foreign policy, 183–4; technological leap forward (from 1870), 58–9; theories of, 10–11, 14, 190; Thucydides trap, 156–7; utopian faith in technology, 127–8; Western thought on China, 158–9, 161–2; ‘wrong side of history’ language, 187–8, 190, 191–2; Zheng He’s naval fleet, 165–6; see also Cold War; Industrial Revolution Hitler, Adolf, 116, 128, 171 Hobbes, Thomas, 104 Hobsbawm, Eric, 5 Hobson, John, 20, 22–3 Hofer, Norbert, 15–16 homosexuality, 106, 107, 109–10 Hong Kong, 163–4 Hourly Nerd, 63 Hu Jintao, 159 Humphrey, Hubert, 189 Hungary, 12, 82, 138–9, 181 Huntington, Samuel, The Clash of Civilizations, 181 Huxley, Aldous, Brave New World, 128, 129 illiberal democracy concept, 119, 120, 136–7, 138–9, 204 India: caste system, 202; circular view of history, 11; colonial exploitation of, 22, 23, 55–6; democracy in, 201; future importance of, 167, 200–1; and Industrial Revolution, 23–4; internal migration in, 41; as nuclear power, 175; and offshoring, 61–2; pre-Industrial Revolution economy, 22; rapid expansion of, 21, 25, 28, 30, 58, 200, 201–2; Sino-Indian war (1962), 166; as ‘young’ society, 39, 200 Indonesia, 21 Industrial Revolution, 13, 22, 23–4, 46, 53; non-Western influences on, 24–5; and steam power, 24, 55–6 inequality: decline in post-war golden era, 43; and demophobia, 122–3; forces of equalisation, 41–3; global top 1 per cent, 32–3, 50–1; growth of in modern era, 13, 41, 43–51; in India, 202; in liberal cities, 49–51; in nineteenth century, 41; and physical segregation, 46–8; urban–hinterland split, 46–51 infant mortality, 58, 59 inflation, 36 Instagram, 54 intelligence agencies, 133–4 intolerance and incivility, 38 Iran, 175, 193, 194 Iraq War (2003), 8, 81, 85, 156 Isis (Islamic State), 178, 181, 182–3 Islam, 24–5; Trump’s targeting of Muslims, 135, 181–3, 195–6 Israel, 175 Jackson, Andrew, 113–14, 126, 134 Jacobi, Derek, 128–9 Japan, 78, 167, 175 Jefferson, Thomas, 56, 112, 163 Jobs, Steve, 25 Johnson, Boris, 48, 118–19 Jones, Dan, 9 Jospin, Lionel, 90 journalists, 15, 65 judiciary, US, 134–5 Kant, Immanuel, 126 Kaplan, Fred, Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War, 176–8 Kennedy, John F., 146, 165 Kerry, John, 8 Keynes, John Maynard, 153–5, 156 Khan, A.Q., 175 Khan, Sadiq, 49–50 Kissinger, Henry, 14, 162, 166 knowledge economy, 47, 61 Kreider, Tim, 111 Krugman, Paul, 162 Ku Klux Klan, 98, 111 labour markets: and digital revolution, 52–5, 56, 61–8; and disappearing growth, 37; driving jobs, 56–7, 63, 191; gig economy, 62–5; offshoring, 61–2; pressure to postpone retirement, 64; revolution in nature of work, 60–6, 191–3; security industry, 50; status of technical and service jobs, 197–8; and suburban crisis, 46; wage theft, 192; zero hours contracts, 191 Lanier, Jaron, 66, 67 Larkin, Philip, 188 Le Pen, Marine, 15, 102, 108–10 League of Nations, 155 Lee, Spike, 46 Lee Teng-hui, 158 left-wing politics: and automation, 67; decline in salience of class, 89–92, 107, 108–10; elite’s divorce from working classes, 87–8, 89–95, 99, 109, 110, 119; in France, 105–10; Hillaryland in USA, 87–8; and ‘identity liberalism’, 14, 96–8; McGovern–Fraser Commission (1972), 189; move to personal liberation (1960s), 188–9; populist right steals clothes of, 101–3; Third Way, 89–92; urban liberal elites, 47, 49–51, 71, 87–9, 91–5, 110, 204 Lehman Brothers, 30 Li, Eric, 86, 163–4 liberalism, Western: Chinese hostility to, 84–6, 159–60, 162; crisis as real and structural, 15–16; declining belief in ‘meritocracy’, 44–6; declining hegemony of, 14, 21–2, 26–8, 140–1, 200–1; elites as out of touch, 14, 68–71, 73, 87–8, 91–5, 110, 111, 119, 204; and ‘identity liberalism’, 14, 96–8; linear view of history, 10–11; Magna Carta as founding myth of, 9–10; majority-white backlash concept, 12, 14, 96, 102, 104; psychology of dashed expectations, 34–41; scepticism as basis of, 10; and Trump’s victory, 11–12, 28, 79, 81, 111; ‘wrong side of history’ language, 187–8, 190, 191–2; see also democracy, liberal Lilla, Mark, 96, 98 Lincoln, Abraham, 146 Lindbergh, Charles, 117 literacy, mass, 43, 59 Lloyd George, David, 42 Locke, John, 104 London, 46, 47, 48, 49–50, 140 Los Angeles, 50 Machiavelli, Niccolò, 133 Magna Carta, 9–10 Mahbubani, Kishore, 162 Mailer, Norman, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, 189 Mair, Peter, 88, 89, 118 Mann, Thomas, 203 Mao Zedong, 163, 165 Marconi, Guglielmo, 128 Marcos, Ferdinand, 136 Marshall, John, 134 Marshall Plan, 29 Marxism, 10, 11, 51, 68, 106, 110, 162 Mattis, Jim, 150–1 May, Theresa, 100, 152, 153 McAfee, Andrew, 60 McCain, John, 134 McMahon, Vince and Linda, 124, 125 McMaster, H.

Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

by

Adom Getachew

Published 5 Feb 2019

According to the International, Wilson’s project in the league “is meant only to change the commercial label of colonial slavery.” The idealism and universalism with which Wilsonism had become associated only masked what was a [ 52 ] Ch a pter T wo preservation of racial hierarchy and colonial exploitation.90 The League of Nations was a league of “imperialist counter-revolution” that could be defeated only through the combination of anti-imperialist and proletarian revolution.91 The language of “colonial slavery” would soon become the central metaphor of black anticolonial critique, but in February 1919, the Second Pan- African Congress, which Du Bois hastily organized in Paris to coincide with the treaty negotiations, made more moderate demands and did not break with the league.

…

They too were not allowed to manufacture any commodity which might compete with industries in the metropolitan country.13 For Nkrumah, colonialism was primarily a strategy of economic exploitation where colonies produced raw materials for the metropole and consumed its manufactured goods. This economic exploitation had required political subordination, and as a result independence and autonomy were central to overcoming colonial exploitation. However, while Nkrumah urged his fellow nationalists to “seek ye first the political kingdom,” he remained concerned that political independence alone would not transform economic dependence.14 An end to colonialism entailed the creation of a political kingdom that could secure both political independence and a transformation of colonial economic relations.15 Through their invocation of American independence, Nkrumah and Williams cast themselves and fellow anticolonial nationalists across the world as “heirs to the tradition of 1776.”16 In recent accounts, the example and legacy of 1776 is often understood as one that privileges national sovereignty.

…

The claim that imperialism had produced an uneven but integrated global economy allowed proponents of the NIEO to represent the international arena as a site for demands of redistribution that extended far beyond aid and charity. This was not pitched as a backward-looking argument for historical redress and remedy of colonial exploitation of the kind that contemporary reparations projects have articulated. Instead, it was a demand based on the claim that the structural conditions of the global economy persistently transferred the gains of productivity to the global north. On this view, the rejection of delinking was not so much an argument about feasibility but an opportunity to stage a political demand for international redistribution.

Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

by

Hans Kundnani

Published 16 Aug 2023

In fact, the core of “pro-European” thinking after World War II had already been established in the inter-war period—in particular, the idea that Europeans must unite in order to recover their dominant position in the world or at least prevent their further decline. After World War II, early “pro-Europeans” even took up the pan-European movement’s idea of the colonial exploitation of Africa as Europe’s “plantation”, as we will see in chapter 3.47 In other words, from the beginning, the European project was not just about peace, as post-war “pro-Europeans” would often later claim. It was, always, also about power. Europe’s superiority complex In the period from ancient Greece to the outbreak of World War II, Europe went from being an indeterminate space to an embryonic identity synonymous with Christianity or Christendom, to a more complex identity that was both rationalist and racialised, and finally, in the twentieth century, to a geopolitical bloc that needed to unite to survive.

…

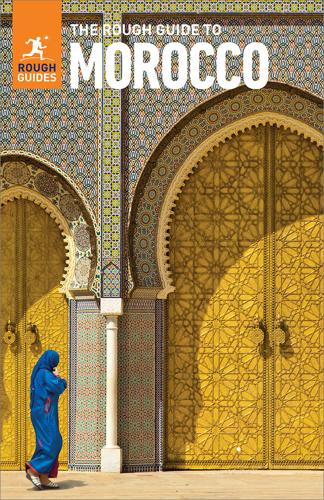

See Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front, FLN) Foner, Eric, 23 Foreign Office, 163 foreign policy, 38, 118–24, 129, 146 Forlenza, Rosario, 78–9 France, 19, 38, 55, 74, 75, 76, 83, 84, 110, 111, 120, 127, 131 Code Noir, 52, 56 colonialism, 50–1 colonies of, 70, 71, 72 control over Indochina, 70, 71, 72 Euroscepticism, 103 foreign policy, 146 L’Europe qui protège, 136–41 Macron’s approach to refugee crisis, 140 single currency, 100 Ukraine War responses, 147 Frevert, Ute, 61 Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front, FLN), 73 Frontex, 145 Gaddafi, Muammar, 110 Gaitskell, Hugh, 167 Gasset, José Ortega y, 61, 90 Gaub, Florence, 150 “geopolitical” Europe, 138, 146, 150 “geopolitics”, 59–60, 126, 130 German nationalism, 21, 22, 32 Germany, 29–30, 34, 80, 82, 83, 102, 111, 127, 130 approach to Namibia, 171 euro crisis approach, 130, 131–4 Macron’s proposals, 137, 138, 139–40 refugee crisis approach, 134–6 Russia as a potential partner, 129 Ukraine War responses, 147 Gilroy, Paul, 171, 174–5, 176, 177 “Global Britain”, 8–9, 153 Goldberg, David Theo, 49, 50, 93 Grande, Edgar, 69, 115 Greece, 43, 86–7, 89, 90, 102, 133, 140 Greek debt crisis (July 2015), 134 Greeks, 43–4, 64 Greenland, 88 “guest workers” (Gastarbeiter), 85 Habermas, Jürgen, 15–16, 17, 33, 34, 123 Haitian revolution, 55 Hall, Stuart, 31 Hay, Denys, 45–6 Heath, Edward, 166 Heine, Heinrich, 92 Herodotus, 43 Holocaust, 91–3, 95, 115, 171 Holy Roman Empire, 47 Hong Kong, 169 Horkheimer, Max, 77 Hugo, Victor, 64 human rights, 53–4 Hungary, 36, 114, 135, 143, 151 Huntington, Samuel, 142 Iberian Peninsula, 44, 45 “imagined communities”, 24–30 Immigration Act (1971), 166 Imperial War Museum, 176 International Monetary Fund (IMF), 132–3 Iran, 139 Iraq, invasion of (2003), 122, 123 Ireland, 86, 87–8, 108, 173 Ischinger, Wolfgang, 30 Islam, 8, 37, 45, 46, 48, 126, 140–1 “Islamist separatism”, 141 Islamophobia, 112, 158, 161 Italy, 71, 72, 73–4, 102, 104, 110, 129, 140 Johnson, Boris, 156 Jospin, Lionel, 144 Judt, Tony, 76, 77, 87, 92, 101, 115 Juncker, Jean-Claude, 127 Kansteiner, Wulf, 91 Kant, Immanuel, 16, 56–7, 58, 120 Kenya, 166 Kimmage, Michael, 78 Kjellén, Rudolf, 60 Kohl, Helmut, 100 Kohn, Hans, 20–1, 23 Krastev, Ivan, 97, 106 Kundera, Milan, 116 L’Europe qui protège, 136–41 labour migration, 74 See also migration Le Grand Remplacement (Camus), 37 Le Pen, Marine, 136, 139, 140 Lega (Italian political party), 142 Leonard, Mark, 41, 70 Leyen, Ursula von der, 29, 143, 148–9 Lisbon Treaty (2007), 123–4 Lumumba, Patrice, 76 Luns, Joseph, 74 Lyautey, Hubert, 62 Maastricht Treaty (1992), 97, 100–1, 103, 108, 119, 167–8 Machiavelli, 48 Macron, Emmanuel, 136–41, 143, 146 Malik, Kenan, 58 Margalit, Avishai, 92–3 Maritain, Jacques, 78 Martel, Charles, 44 Marxism, 80 May, Theresa, 19–20, 168 Medieval Europe, 32–3, 43–8 Merkel, Angela, 130, 131–2, 134–5, 139–40, 141 methodological regionalism, 172 Middelaar, Luuk van, 41 Middle East, 31, 46, 125, 128 migration refugee crisis (2015), 17, 126, 134–6, 140, 150 threats, 8, 36, 37, 144–6 Ukraine War and, 149–50 Milanovic, Branko, 114 Milward, Alan, 75 Mitterrand, François, 28, 100, 138 “mobility”, 128–9 Modern Europe, 48–53 Mollet, Guy, 81 Monnet, Jean, 80 Morin, Edgar, 34, 42 Morocco, 86, 88, 109–10 Mozarabic Chronicle, 44 Müller, Jan-Werner, 83–4, 91–2, 123 Müller-Armack, Alfred, 82 Muslim rule in Iberian peninsula, 45, 46, 50 Nachtwey, Oliver, 132 National Health Service, 165 nationalism, 28–9 Anderson on, 24–5, 47 Coudenhove-Kalergi on, 63 Gasset on, 61 methodological, 171–2 Nationality Act (1948), 165 NATO, 89, 119, 122 Nazism, 77, 176, 177 neoliberal economic policy, 159 neo-liberalisation, 4, 8, 99–104, 106 the Netherlands, 36, 71, 74, 76, 103, 142 Nkrumah, Kwame, 75 Nobel Peace Prize, 69 Nord Stream 2 (gas pipeline), 130 “normative power”, 121–2 north Africa EEC and north African states, 85–6, 110 immigration from, 129 pro-democracy protests, 128 North Atlantic Treaty (1949), 78 “offshore balancing”, 176 Orbán, Viktor, 135, 140, 141, 151 Othering, 32–3, 66, 84 Ottoman Empire, 46–7, 48 Paneuropa (pamphlet/journal), 63 pan-European movement, 61–4 Parkes, Roderick, 145 Pécresse, Valerie, 38 personal protective equipment (PPE), 29 PiS (Polish political party), 143, 150 Pius II, Pope, 46 Plato, 55 Pleven, René, 71 Poland, 36, 114, 115, 116, 129, 130, 147, 150, 151 Poos, Jacques, 120, 122 Popławski, Konrad, 133 “populism”, 35–6, 133, 154, 159, 165, 168 Eurosceptic, 126 regional, 37 Portugal, 102 accession to the EC, 86–7, 88–9, 90 Ceuta conquest (1415), 49 Posted Workers Directive, 137 “print capitalism”, 25 pro-democracy protests in North Africa and the Middle East (2011), 128 Prodi, Romano, 93–4 “pro-Europeanism”, 61, 136 “pro-Europeans” colonial exploitation of Africa, 63 on colonialism, 94 defensive civilisationalism, 38–9 demand traditional foreign policy, 122 EU stands for universal values, 53–4 European identity, thinking of, 20, 28, 30–1, 33 far right and, 37 nationalism, rejection of, 41 on regionalism, 19 on social market economy, 84 thinking on sovereignty, 27 views on nationalism, 28–9, 33–4 views on Ukraine War, 151 Putin, Vladimir, 129, 147 racial hierarchy, 56–7, 58 racism, 9–10, 93, 153 Brexit as an expression of, 153, 156, 158, 160–4 Rassemblement National (French political party), 38 Ratzel, Friedrich, 62 refugee crisis (2015), 17, 126, 134–6, 140, 150 regionalism.

The Hidden Globe: How Wealth Hacks the World

by

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian

Published 7 Oct 2024

In a few short sentences, Romer—the privileged son of a Colorado governor, with an economics PhD from the University of Chicago—implied not only that poor countries had bad governments making the rules, but that it was crucial to change the way those governments went about their business if their citizens were to become less poor. Romer didn’t mean it that way. He acknowledged his blind spot later, in a conversation on the podcast Freakonomics. “As anybody, I guess, besides me will notice, this raises all kinds of alarms about colonialism and the history of colonial exploitation in Africa,” he told the host. “It had this guilt by association that meant that everybody was a little bit horrified by the suggestion. But I felt like we just needed to talk about how we could try something else in development, because development assistance, frankly, has been a failure.” That “something else” was to separate laws from lands—only voluntarily this time around.

…

A decade after the Outer Space Treaty was signed by 110 member states of the UN, representatives of eight equatorial countries—Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Indonesia, Kenya, Uganda, and the nations now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Congo-Brazzaville—met in Bogotá to issue a statement on a “growing sector” in which they had a very keen interest: satellite technology. It was not that these countries were technologically advanced—for many, centuries of colonial exploitation had thwarted their ambitions. They were, however, fortuitously positioned to take advantage of other countries’ advances by virtue of their location along the Earth’s horizontal axis, some 22,236 miles beneath a section of the universe known as geostationary orbit. Many of the satellites we rely on every day for communications, meteorology, and data are synchronous with the Earth’s orbit, which means they follow the Earth’s rotation perfectly.

…

As we have seen, many countries commercialize their sovereignty, sometimes to absurd effect. But even former colonies’ adoption of free zones were decisions made, if not from a position of outright power, then at least from one of choice. In the Pacific, the establishment of the camps follows a broad historical pattern defined by colonial exploitation. “It’s states looking for opportunity…with little strong and sustainable economic opportunity,” Damon Salesa, the vice chancellor of Auckland University of Technology, told me over Zoom. “And because they’re small, they’re more vulnerable to single points of capital and shifting political discussions.”

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by

Jesse Norman

Published 30 Jun 2018

As we have seen, Adam Smith deplored the tendencies to monopoly and colonial exploitation, the anti-competitive effects of trade restrictions, privileges and tariffs, and the distortion of domestic politics created by the great mercantile lobbies—the national and international forerunners of today’s crony capitalism. And there can be little doubt he would have denounced many of these later developments. He was a committed believer in the wisdom of freeing up trade as between willing partners, but he was also acutely aware of the evil effects of colonial exploitation, and was hostile to the use of coercion to open up trade.

…

See England broken windows theory, 309 Brougham, Henry, 200 Brown, Gordon, xi Buccleuch, Duke of, 81–84, 86–88, 91, 93, 132 Buchanan, James, 271 Buffett, Warren, 224–225 Burke, Edmund, xv–xvi, 66, 101, 125, 138–140, 150, 258 Burns, Robert, 60–61 Butler, Bishop, 76 Calas, Jean, 83, 288–291 campaign finance law, 258 Canongate Church, 133 capital accumulation, 181–182 banks and, 108 in cash account, 89 circulating, fixed, 110 in markets, 273–274 money and, 91–92, 108 services in, 111 shortage, in Scotland, 89, 91 Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Piketty), 259 capitalism, 258–259, 265 commercial society and, 325–326 corporate, 267 equality and, 273–276 franchise, khaki, licence, 263 globalization and, 287 monopoly, 263 wealth-creation in, 275, 321 See also crony capitalism; narco-capitalism cases, effects and, 44 cash account, 89, 92 Catholicism, 31–32, 83, 163–164, 183, 288–289 Cato (Addison), 8 Charles I (king), 47 Charles II (king), 12 church funding, 120–121 state and, 120–121 Church of England, 22 Church of Scotland, 18, 127 circulating capital, 110 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), 258 civilizing process, commerce as, 292–295 Clarkson, Thomas, 235 Clay, Henry, 276 Cochrane, Andrew, 53 collective mind, 174 colonial exploitation, 278 colonial monopolies, 138 colonization, 114 Commentaries on the Laws of England (Blackstone), 100 commerce capital accumulation and, 181–182 as civilizing process, 292–295 free, 200 Hume on, 292–293 regulation of, 113–114, 188–189 in system of natural liberty, 292 value of, 235–236 See also doux commerce commercial society, 223, 265–266, 268, 271 capitalism and, 325–326 changes in, 329–330 economic relationships in, 293–294 institutions in, 295 strong states of, 327 taxation and, 116–117 The Wealth of Nations on, 316 commercial system, of England, 114–115 commercialization society, 311–319 communication, 41–42, 334 companies, American, 280–282 comparative advantage, 199 compassion, 58 competition, 108–109, 216 conjectural history, 77–78 conscience, 76 “Considerations Concerning the First Formation of Languages” (Smith, A.), 41 consumers algorithmic, 285 digital, 285–286 producers and, 109–110 Cooper, George, 252 corporate capitalism, 267 corporate lobbying, 264 corporations, 257–258, 321 cosmos, 46 Cournot, Antoine Augustin, 202 Cromwell, Oliver, 12 crony capitalism, 328, 332 defining, 262 in inequality, 275 lobbying in, 262–264 mercantile interest and, 262–273 new forms of, 280–287 technology in, 280–284 Cullen, William, 49, 98–99, 151 culture, 291–292 customers, 283 Darwin, Charles, 168–169, 173 death, of Smith, A., 153 Debreu, Gérard, 194–195, 205–206 Declaration of Independence, 103, 128 The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Gibbon), 123 Defoe, Daniel, 16–17 Descartes, René, 165 Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (Hume), 127–128, 130, 132, 171, 302 Dialogues of the Dead (Lucian), 130–131 Dictionary of the English Language (Johnson), 51–52, 97–98 didactical method, 42–43 digital consumers, 285–286 A Discourse on Government with Relation to Militias (Fletcher), 118 Discourse on Inequality (Rousseau), 55 disregard, 308 division of labour, 105 in markets, 106–107 in The Wealth of Nations, 177 wealth-creation and, 110 Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, 260 Douglas, Janet, 68, 133, 140, 151, 155–156, 218 Douglas, John, 143–144 Douglas, Margaret, 6 doux commerce, 292, 326 Dr.

A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

by

Raj Patel

and

Jason W. Moore

Published 16 Oct 2017

Recent financial histories have ignored the Casa di San Giorgio, in part because of the obscurity of its manuscripts, in part because the Genoese weren’t the showboaters that the Venetians were.50 But their facility with credit lines and their connections to European aristocracies made it possible for them to access money at the lowest possible interest rates until the eighteenth century.51 They were masters of cheap money, a mastery they achieved by financing, and reaping the rewards from, Spain’s colonial exploits. The Genoese weren’t alone in making the provision of credit pay, and other banking institutions followed in their footsteps, later in Amsterdam and then in London and the United States. But the Genoese story is significant because it brings together many of the key elements of cheap money: the need for profit, the capacity to fund colonies, and the requisite attitude to nature.

…

Under colonial rule, India was tasked with funding, through taxation, Britain’s worldwide imperialism: “Ordinary Indians . . . paid for such far-flung adventures of the Indian army as the sacking of Beijing (1860), the invasion of Ethiopia (1868), the occupation of Egypt (1882), and the conquest of the Sudan (1896–98).”37 Colonial exploitation intensified yet further when Germany and the United States—and quickly Japan and the rest of Europe—joined Britain on the gold standard after 1871. The value of India’s silver-based rupees collapsed by more than a third between 1873 and 1894—while its payments to Britain were denominated in gold.38 Market mechanisms and violence went hand in hand with the flow of cheap food from Asia to Europe.

From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

by

Pankaj Mishra

Published 3 Sep 2012

In 1951, arguing his case for the nationalization of Iran’s British-run oil industry at the United Nations, Mohammad Mossadegh spoke of how the Second World War had changed ‘the map of the world’. ‘In the neighbourhood of my country,’ he said, ‘hundreds of millions of Asian people, after centuries of colonial exploitation, have now gained their independence and freedom.’ Speaking of countries that had ‘struggled for the right to enter the family of nations on terms of freedom and equality’, the Iranian prime minister asserted that ‘Iran demands that right’. He received a tremendous ovation. Even Taiwan, ushered into the UN through the back door by the United States, was moved to remind the British that ‘the day has passed when the control of the Iranian oil industry can be shared with foreign companies’.22 Two years after this speech, which is still remembered in Iran, Mossadegh was toppled by an Anglo-American coup.

…

But the transition from criticizing foreign rule and instigating mass movements to establishing a stable basis for self-determination proved to be very difficult. The idealist impulses behind revolt and national independence soon faded before the sheer magnitude of such nation-building tasks as sustained economic growth and territorial consolidation. Stumbling out of long decades of colonial exploitation into a world bitterly divided by the Cold War, the new states had to urgently find aid and capital for weak, often pre-industrial economic systems; set fiscal policy; institute land reforms; build such political institutions as parliaments, electoral commissions and parties; make national citizenship more attractive than local loyalties to ethnic, religious, linguistic and regional groupings; codify a legal order; make primary education and health care accessible; attack poverty and crime; and maintain roads and railways.

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by

Malcolm Harris

Published 14 Feb 2023

The southern campaign famously, on the counsel of Ella Baker, opted for a diversity of tactics, registering voters and running candidates while maintaining direct-action agitation for integration.13 And much like people’s liberation armies throughout the decolonizing world, COFO organizers found themselves doing development work to counter the forced underdevelopment endemic to colonial exploitation, which meant setting up “freedom schools” to teach literacy in particular.14 Among the outside organizers, the willing ones learned a lot from the rural workers they were there to organize as well, not least about the vital importance of guns to the movement’s self-defense. Into the mid-1960s, white violence and the experience of black community endurance shifted the consciousness of organizers.

…

16 There are other, more popular interpretive frames for American politics in the 1960s: There is the Oedipal one about generational struggle; the cultural one about the disillusioned shift to individualism; the patriotic reformist one about protests moving a nation’s heart and securing formal equality. It has been made difficult to see the country in a global-historical frame, as one nation among many that came together in their current forms at the end of the nineteenth century and have teetered on unstable foundations of colonial exploitation ever since. These countries faced a set of analogous pressures in the years following the Second World War, and despite its unique position America wasn’t exempt, especially if we’re conscious of the country’s timeline of development and expansion. California had more in common historically with South Africa than with England.

…

At the time, on the ground, the division between the personal revolutionaries and the California decolonists was much clearer: One side tossed rocks at the other. There is no single line that connects California to the world anticolonial struggle; they are embedded in the same history, as I contended in the first section. It was colonial exploitation that linked these conflicts in the first place, not the spread of doctrines or encounters between individuals. We know this is the case because when large-scale street violence and conflict kicked off in California in the 1960s, it wasn’t thanks to an armed insurrectionary party. Riots that went beyond organizational politics—the organic black-led uprising of the urban exploited, what King called “the language of the unheard”—erupted across Johnson’s America.

"They Take Our Jobs!": And 20 Other Myths About Immigration

by

Aviva Chomsky

Published 23 Apr 2018

Modernization theorists compared “underdeveloped” or “less developed” countries to “developed” countries, implying that “development” was a discrete process that all countries would go through at their own pace. Scholars from the dependency school responded that underdevelopment and development were two sides of the same coin: underdevelopment was not a starting state but rather a result of colonial exploitation. Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa critiques the term and the theory behind it. Other economists offered “industrialized” and “non-industrialized,” and later added “newly industrialized” or NICS (newly industrialized countries, referring usually to Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong).

Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture

by

Marvin Harris

Published 1 Dec 1974

Instead they taught about creation, prophets and prophecies, angels, a messiah, supernatural redemption, resurrection, and an eternal kingdom in which the dead and the living would be reunited in a land of milk and honey. Inevitably, these concepts—many rather precisely analogous to themes in the aboriginal belief system—had to become the idiom in which mass resistance to colonial exploitation was first expressed. “Mission Christianity” was the womb of rebellion. By repressing any form of open agitation, strikes, unions, or political parties, the Europeans themselves guaranteed the triumph of cargo. It was relatively easy to see that the missionaries were lying when they said that cargo would only be given to people who worked hard What was difficult to grasp was that there was a definite link between the wealth enjoyed by the Australians and Americans and the work of the natives.

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by

William N. Goetzmann

Published 11 Apr 2016

Chinese entrepreneurs managed their way through a multicultural world of foreign competition, wars, and the complexities of an eroding nation-state to lead China into the modern world economy. By 1905, Chinese officials had adopted corporate governance and a sophisticated corporate legal code that formed the basis for the transition to successful private corporate ownership. However, China’s Communist Revolution in 1949 reinterpreted this success story in stark terms as colonial exploitation by the capitalistic West. There is a germ of truth in their revisionist history. China’s financial modernization resulted from the weakening of the central government and erosion of sovereignty. It also began with a dangerous drug. ADDICTION IS A VALUE PROPOSITION The opium trade is one of the most shameful episodes in the history of finance.

…

Alignment of incentives to promote growth works a lot better than a control-and-command approach. Keynes, of course, posited a central role for government in solving the disjunctions caused by unchecked financial globalization and bad savings habits. His legacy is a financial architecture designed to blunt the potential for colonial exploitation by disintermediating lenders and sovereign borrowers—replacing that relationship with a collective institutional financial organization. Did Bretton Woods save the world from a revival of imperialism? Did it bring more nations into the fold of prosperity? Whether it did or not, it undeniably altered the way that nations interact with one another and with the capital markets.

Happy Valley: The Story of the English in Kenya

by

Nicholas Best

Published 9 Aug 2013

The chief constitutional adviser to the Africans was Dr Thurgood Marshall. He was a black American lawyer, later to become a judge in the US Supreme Court. Before the conference, Marshall had irritated Kenya’s white settlers by writing an anti-imperialist article in a Baltimore newspaper. He had accused the settlers of being colonial exploiters who had never even taken the trouble to learn the local language. At one of the conference sessions therefore, Sir Michael Blundell formally tabled a motion for proceedings to be conducted in Swahili. The language was spoken fluently by all the Kenya Europeans present, but not by Thurgood Marshall.

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

In 2004, Le Guin described how “‘Technology’ and ‘hi tech’ are not synonymous, and a technology that isn’t ‘hi,’ isn’t necessarily ‘low’ in any meaningful sense.”26 We need to stop being distracted by the Hyperloops and the Boring Companies designed to stifle investment in trains and transit; the on-demand services that decimate workers’ rights in service of convenience; and the electric sports cars and SUVs that promise a green future while driving a new wave of neo-colonial exploitation. Better futures are possible, but they will not be delivered through technological advancement alone. They require engaging with the problems of our time and recognizing that they do not exist simply because we do not have the requisite technology to solve them. Addressing the inequities and harms of our world does not require the invention of new technologies; it requires a new politics that recognizes economic growth and technological innovation do not guarantee social progress.

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by

Douglas Rushkoff

Published 1 Mar 2016

The expected “synergies” never quite pan out, which is why 80 percent of mergers and acquisitions end up reducing profit on both sides of the deal.17 Other companies attempt to lower expenses by outsourcing core competencies. Offshoring allows corporations to utilize workforces as they did back in the good old days of colonial exploitation. Finding employees overseas to work for almost nothing is easy. Indebted nations make the easiest targets. Forced to service their loans by exporting their local crops and resources, such countries can no longer offer subsistence farming opportunities to their citizens. So foreign multinational corporations end up with monopolies on employment and trade very similar to the kinds they enjoyed back in the 1600s.

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

by

Steven Johnson

Published 15 Nov 2016

But perhaps the most extraordinary passage comes when she attempts to integrate the global reach of the spice trade into a broader story of Divine Purpose: God, she explained, saw fit to distribute the “good things of his creation . . . into the most remote places of the universal world . . . he having so ordained that the one land may have need of the other; and thereby, not only breed intercourse and exchange of their merchandise and fruits, which do so superabound in some countries and want in others, but also engender love and friendship between all men, a thing naturally divine.” Knowing the grim history that was to follow—almost four hundred years of colonial exploitation and slavery in pursuit of those “good things”—it is hard not to be cynical, if not outright appalled, by the talk of “love and friendship between all men.” But Elizabeth does hit upon an essential fact: that spices were distributed into the “most remote places of the universal world.” The taste for those spices compelled human beings to invent new forms of cartography and navigation, new ships, new corporate structures, not to mention new forms of exploitation—all in the service of shrinking the globe so that pepper raised in Sumatra might more efficiently be delivered to the kitchens of London or Amsterdam.

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality

by

Don Watkins

and

Yaron Brook

Published 28 Mar 2016

In America today, even those who are poor relative to their neighbors are among the richest people in history. Unfortunately, some have not benefited from human progress, namely the people who live in those parts of the world that have not industrialized. In some tragic cases, they have been victims of invasion and colonial exploitation. But this is not the cause of their poverty, nor was colonization the main source of the West’s prosperity. The West’s prosperity came from creating the conditions under which individuals could think, create, trade, and prosper. Today, more and more of the world is following our lead, with the result that billions around the globe have been liberated from poverty in recent decades: since 1981, the fraction of the earth’s population living on less than a dollar a day has dropped from over 40 percent to only 14 percent.23 This is an incredible achievement.

The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth Is Unattainable and the Global Economy Is in Peril

by

Satyajit Das

Published 9 Feb 2016

Greater economic activity helped improve living standards, reducing pressure for wealth redistribution. The democratization of credit allowed lower income groups to borrow and spend despite stagnant real incomes. Global economic growth improved the wealth of emerging nations, increasing the living standards of their citizens. This avoided awkward issues of colonial exploitation and reparations. Growth was perceived to benefit poorer members of society by improving the economy as a whole. Henry Wallich, a former governor of the US Federal Reserve, summed it up: “So long as there is growth there is hope, and that makes large income differentials tolerable.”4 But while growth has been the focus of economic management, it is a relatively recent phenomenon.

American Marxism

by

Mark R. Levin

Published 12 Jul 2021

Degrowthers want to engage in policies that will set ‘a maximum income, or maximum wealth, to weaken envy as a motor of consumerism, and opening borders (“no-border”) to reduce means to keep inequality between rich and poor countries.’ And they demand reparations by supporting a ‘concept of ecological debt, or the demand that the Global North pays for past and present colonial exploitation of the Global South.’ ”11 The degrowthers also demand that government establish a living wage and reduce the workweek to twenty hours.12 Serge Latouche, a French emeritus professor of economics at the University of Paris-Sud, is among the leading degrowthers. “In the 1970s, Serge Latouche spent several years in South Africa, where he conducted extensive research on traditional Marxism, where he formed his own ideology based on ‘progresses and development.’

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 10 Apr 2016

These advantages were distributed among the workers very unevenly; the lion’s share was snatched by a privileged minority, though something was left over from time to time for the broad masses.”14 By 1915, when Bukharin wrote Imperialism and World Economy, there was no more doubt that even workers in rich countries enjoyed a higher standard of living than most of the population in colonies. The labor aristocracy that was created in the rich countries thanks to colonial exploitation, among other factors, was the reason why the Second International broke down and supported the war: as Bukharin (1929, 165) wrote, “the exploitation of third persons (pre-capitalist producers) and colonial labor led to the rise in the wages of the European and American workers.” This is exactly the phenomenon we see reflected in Figure 3.3: the rising importance of location meant that, say, British workers’ standard of living outpaced the standard of living of the middle classes and even of many rich people in Africa and Asia (that is, people who were rich within their own countries’ distributions).

Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape Our World

by

Gaia Vince

Published 22 Aug 2022

These reasons help keep urban Africans significantly poorer than their counterparts on other continents. This makes them more vulnerable to the effects of climate change and other shocks and stresses – and a priority for mass migration. There are multiple factors behind this, including the legacy of colonial exploitation, HIV, conflict and poor governance, plus an unproductive agricultural sector that makes food costly and limits incomes. However, better urban planning, with denser housing, wider roads, and good transport and infrastructure, would vastly improve the productivity and wealth of cities in Africa during the transition to urbanization this century – and improve people’s climate resilience.

Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic

by

Hugh Sinclair

Published 4 Oct 2012

It was little more than two months after leaving my post with USAID as Asia Regional Advisor on Development Management that a fresh insight hit me. Foreign aid, as practiced, is almost inherently destructive, because it increases the dependence of poor countries on the goods, technologies, markets, finance, and expertise of rich countries and leaves them exposed to classical colonial exploitation in a new guise. It is hard to see the truth of a system on which your pay and prestige depend. Follow the Money To my surprise and shock, I once heard a microlending advocate make the amazing claim that high interest rates are a rich people’s concern. They don’t matter to the poor.

Sextant: A Young Man's Daring Sea Voyage and the Men Who ...

by

David Barrie

Published 12 May 2014

READING ABOUT COOK’S exploits today, it is easy to underestimate the scale of the challenges he faced. So many of the places he visited are now holiday destinations that we may even envy him the privilege of seeing them in their pristine state—before they were ravaged by imported pests and diseases and turned upside down by missionary Christianity, colonial exploitation, and tourism. It requires an effort of imagination to grasp how demanding and relentless were the difficulties he had to overcome. The single biggest problem, apart from the safe management of his ship, was ensuring that her crew and passengers had adequate supplies of fresh food and water—an anxious and unremitting task when sailing in almost completely uncharted waters.

Red Flags: Why Xi's China Is in Jeopardy

by

George Magnus

Published 10 Sep 2018

China may have lost between 15 and 20 million people, and had to cope with up to 100 million refugees.21 War weakened the Nationalists and emboldened the Communists, and after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War and the withdrawal of its forces from the mainland, the Nationalists and Communists continued to fight until 1949. Legacies and myths It is not surprising that dark memories of this period of colonial exploitation, war and civil war persist in China. They have shaped and influenced China and its attitudes ever since the People’s Republic was declared. In looking for explanations for China’s chronically weak economic performance in the century before 1949, the carve-up of China occupies pride of place.

The City

by

Tony Norfield

See also financial power; economic power price fixing 118, 120–1 privatisation 120 production 77, 78, 86 productive capital 90 productivity 69, 148–9, 150 profit and profitability 21–2, 77, 129–39 American rate of 153–9, 154, 157 amount 149, 150 comparing 136–9 and costs 149–50 drivers 135–6 equalising 137 and financial crisis 135 and financial returns 135 and fixed assets 137 global 156 and interest rates 156–7 investment location 152 and labour costs 155–6 leverage 130–6, 133, 134 measurement 153 moribund 159–60 and productivity 148–9, 150 rate of 130, 147–50 restoration of 152, 154–5 return on equity (RoE) 129–30 role of financial assets 137 sources 129, 139–47, 143 volatility 131 property bubbles 151 proprietary positions 79 quantitative easing 65, 152, 157–9 Radcliffe Report 35 Reagan, Ronald 65 real economy, the 5 reform agenda 214 regulation 9, 215–16 American 39–40 state 115–16 Regulation Q (US) 39, 48 regulatory arbitrage 42 rentiers 98 repo borrowing 46 return on assets 132 return on equity (RoE) 129–30, 132 returns, distribution of 102–3 revenue-earning assets, bank creation of 137, 137–8 Rich, Marc 122 risk 130 rivalry 28 Robin Hood tax 215–16 Rolling Stone 161 Rome, Treaty of 33, 57, 58, 69 Royal Bank of Scotland 4 Royal Dutch/Shell Group plc 3, 112–13, 220 Rubin, Robert 16 Russia 18, 93, 106, 107, 109, 113–14, 154, 171, 216, 222, 223, 224 SABMiller 121 Samsung 118, 120, 121–2 sanctions 113–14, 172, 216 San Francisco 37 Saudi Arabia 55–6, 109, 208, 220 Scotland, independence referendum 217–18 Second World War 26–8, 151 seigniorage 43, 163–6 Shanghai 18, 182, 222–3 shareholders, power 88 share issues 179 shares 139 value 86–7 share swaps 179, 199 Sharpe ratio 131 Shell 114 Shenzhen 18 Sherman Antitrust Act (US) 119 short-term money-market instruments 79, 144 Simon, William 55–6 Singapore 177–8, 179, 206, 209 Snowden, Edward 59 South Africa 18, 222, 224 South Korea 101, 120 Soviet Union 29, 30 Spain 65 speculation, madcap 135–6 stamp duty 48 Standard Chartered 225 Standard Oil 119 state, the and capitalism 111–15 and finance 115–17 and imperialism 119 imperialist 126 power 115, 126 sterling collapse, 1992 62 convertibility 31 devaluation, 1949 31 Sterling Area, the 31–3, 35, 58 stock exchange prices 182 stock market crash, 1987 xi, 68 stock swaps 179 Suez crisis 27–8, 60 supply-chain links 77 surplus labour 149 surplus value 90, 140 appropriation of 173–4 creation of 149 global system 161 and securities 144–6 transfer of 97 Sveriges Riksbank 116 Sweden 4, 9, 116 Swiss Bankers’ Association 176 Switzerland 4, 9, 165, 175–6, 178, 184 Taibbi, Matt 161 Taiwan 18 Tanzanian groundnut scheme 33 tariffs 114 tax and taxation 114, 215–16 tax avoidance 48 tax havens 2, 22, 71, 184, 193, 209, 211 Temasek 177 Thailand 101 Thatcher, Margaret xi, 63, 65, 69 Tokyo 49, 50 Toyota 121 trade gap 188 trade patterns 6, 60–1, 61 trading revenues 146–7 Treasury, the 48 UK Independence Party 219 unemployment 53 Unilever 112–13 United Kingdom anti-monopoly policies 119–21 appropriation of value 187 balance of payments 187, 188, 200, 203 bank assets and liabilities 4, 141–4, 143 bank borrowing 206–8 bank deficits 206–10 bank lending 208–10 bank leverage data 134 banking centre status 50 banks 4, 116, 134, 191–7, 192, 194, 196, 206–10, 214 borrowing 201–2, 204–5 China policy 225–6, 227 colonial exploitation 30–3 colonialism 30–1 credit rating 204–5 current account balance 188–90, 189, 190 current account deficit 200, 202, 211, 217 current account surplus 33, 34, 69 debt costs 204–5 decolonisation 30 direct investment returns 202–3, 203 domination 162 earnings from financial services 43–4 economic power 2 economic weakness 35 Empire protectionism 30, 33 equity holdings 102–3 equity market capitalisation and turnover 181, 182 and the EU 16–17, 21 European policy 53–4 FDI 107, 200, 205 financial account 197–200, 199 financial machine 22 financial market share 70–1, 71 financial operations 185–212 financial policy 14, 44–7, 65–70 financial position, 1950s 34–5 financial power 2, 3, 64–5 financial sector benefits 185 financial sector employment 186 financial sector tax revenues 186 financial services assets location 205–6, 207 financial services exports 174 financial services revenues 190–7, 192, 194, 196 financial wealth 103 foreign direct investments 3, 66 foreign exchange trading 109 foreign exchange turnover 193–5, 194 foreign investment income 189–90 freedom of action 63, 64 GDP 4, 106, 107, 155–6 Gowan’s analysis 11–12 Helleiner’s analysis 13–14, 70 Hilferding’s analysis 93, 94 imperialism 7–8, 186, 228 imperial strategy 59–65 inflows of foreign money-capital 69 international banking index 108 international banking position 191–2, 192 international banking share 70–1, 71 international financial revenues 10 international investment position 200–1, 201 investment income 200–4, 203 investment income, 1899–1913 98 invisible empire 7–8 joins EEC 34, 57–8 Lend-Lease debts 29, 36 liabilities 204–5, 206–7 military interventions 1–2 military spending 110 monetary policy 66 OPEC’s investment in 57 pension fund assets 103 quantitative easing 158–9 relationship with America 21, 27–8, 29–30, 36, 59, 73 relationship with Europe 62 return to gold standard 23–6 seigniorage 165–6 status 1–2, 3–4, 27–8, 30, 30–5, 52, 73–4, 110, 111, 196, 204, 210, 213, 214, 216–17, 227–8 tax havens 193 trade currency pricing 163 trade deficit 44, 188–9, 189, 211 trade gap 22 trade pattern 60–1, 61 wealth distribution 102–3 United Nations 3–4, 123 United Nations Security Council 109 United States of America 2, 205 aftermath of First World War 24 anti-monopoly policies 119–21 attitude to Bretton Woods 31 bank Eurodollar deposits 41–2 bank leverage data 132–3 bank regulation 36 banking system fragmented 40 banks 132–3, 193 capital flows from 38 capital markets 55 China policy 226, 227 Chinese challenge to 17–18 corporate rate of profit 153–5, 154 cost of living 155 credit bubble 156 credit restrictions 42 current account deficit 167–8 domestic market 28 domination 3, 7, 10, 11, 26–7, 35, 162, 183–4, 223 equity holdings 102 equity market capitalisation and turnover 181–2, 181 exorbitant privilege 166–9 FDI 107 Federal Reserve System 40 financial business split 37 and financial crises 12 financial market regulations 39–40 financial policy 11, 65–6, 67–8 financial power 6, 11–12, 14–15, 55, 170–3, 183 financial services exports 173–4 financial services revenues 190 financial system 36–40 foreign direct investments 3, 42 foreign exchange trading 108–9, 109 foreign exchange turnover 194, 194 foreign investment revenues 9–10 foreign investment stock position 169 foreign securities market 48 GDP 106, 107 gold reserves 39 gold standard abandoned 54 Gowan’s analysis 11–12 hegemony 21, 105 Helleiner’s analysis 12–14 Hilferding’s analysis 93 imperial advantage 164 imperialism 12, 14–15, 166–9 interbank money market 46 interest rates 168 international banking index 108 international banking position 192, 192 international banking share 50, 71, 71 international capital outflows 66 investment income 169 leverage ratios 131 military spending 109 millionaires 99 mortgage-backed securities 140 mortgage debt 56 Panitch and Gindin’s analysis 14–17 privileged position 22 quantitative easing 157–8 rate of profit 153–9, 154, 157 relationship with Britain 21, 27–8, 29–30, 36, 59, 73 relationship with Saudi Arabia 55–6 role in the world economy 12–14, 14–17 role of 111 seigniorage 163–5 status 105, 110, 111 UK-based lending 209–10 UK debt 29 working-class living standards 154–5 United Technologies 121 unsecured loans, interbank 46 US–China Economic and Security Review Commission 18 US Commerce Department 56 US dollar, the 6, 15, 30 Chinese foreign exchange reserves 167 domination 55, 164–5 exchange rate 68, 163 exorbitant privilege 166–9 financial power 170–3 global role 170–3 glut 38–9 gold standard abandoned 54 imperial advantage 164 privileged position 22 as reserve currency of choice 166 status 35, 108–9 UK colonies surplus 33 US Federal Reserve 14, 41, 42, 44, 116, 157–8, 157, 172–3, 185 US Treasury 14 value xi–xiii appropriation of 187 creation 76, 104, 150–1 extraction 77, 104 relations 90 surplus 90, 97, 144–5, 149 transfer of 164–5 Vietnam War 54, 105 Vodafone Group plc 3, 180 Volcker, Paul 156 Volkswagen 121 wages 77, 144, 148, 152, 155–6 Wal-Mart 77, 155 waste, elimination of 152 wealth concentration of 91–2 distribution 102–3 fictitious capital 88, 147 UK household 103 West, Admiral Lord 1–2, 3, 4 West African Marketing Boards 32 WhatsApp 91 Wilson, Harold 32 Wolf, Martin 214 working-class, living standards 154–5 working hours 38 World Bank 14, 27, 29, 73, 223 world economy 2, 9–10 American role 14–17 world hierarchy 105–11, 111 world monetary system 10 ‘zero hour’ contracts 152 zero sum games 145 Zuckerberg, Mark 91

Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart

by

Tim Butcher

Published 2 Jul 2007

Disease, hostile tribes and the lack of any clear commercial potential in Africa meant that hundreds of years after white explorers first circumnavigated its coastline, it was still referred to in mysterious terms as the Dark Continent, a source of slaves, ivory and other goods, but not a place white men thought worthy of colonisation. It was Leopold's jostling for the Congo that forced other European powers to stake claims to Africa's interior, and within two decades the entire continent had effectively been carved up by the white man. The modern history of Africa - decades of colonial exploitation and post-independence chaos - was begun by a Telegraph reporter battling down the Congo River. Reading about this epoch-changing journey seeded an idea in my mind that soon grew into an obsession. To shed my complacency about modern Africa and try to understand it properly, it was clear what I had to do: I would go back to where it all began, following Stanley's original journey of discovery through the Congo.

Wireless

by

Charles Stross

Published 7 Jul 2009

I mean, that the alternate-Americans wiped them out in an act of colonialist imperialist aggression but did not survive their treachery,” he adds hastily. Misha’s lips quirk in something approaching a grin: “Better work on getting your terminology right the first time before you see Brezhnev, comrade,” he says. “Yes, you are correct on the facts, but there are matters of interpretation to consider. No colonial exploitation has occurred. So either the perpetrators were also wiped out, or perhaps . . . Well, it opens up several very dangerous avenues of thought. Because if New Soviet Man isn’t home hereabouts, it implies that something happened to them, doesn’t it? Where are all the true communists? If it turns out that they ran into hostile aliens, then . . .

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality

by

Angus Deaton

Published 15 Mar 2013

Since World War II, rich countries have tried to help close these gaps using foreign aid. Foreign aid is the flow of resources from rich countries to poor countries that is aimed at improving the lives of poor people. In earlier times, resources flowed in the opposite direction, from poor countries to rich countries—the spoils of military conquest and colonial exploitation. In later periods, rich-country investors sent funds to poor countries to seek profits, not to seek better lives for the locals. Trade brought raw materials to the rich countries in exchange for manufactured goods, but few poor countries have succeeded in becoming rich by exporting raw materials.

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 13 Nov 2007

Equipment was affordable, energy available and labour so abundant that manufacturing textiles in China or India ought to have been a hugely profitable line of business.13 Yet, despite the investment of over a billion pounds of Western funds, the promise of Victorian globalization went largely unfulfilled in most of Asia, leaving a legacy of bitterness towards what is still remembered to this day as colonial exploitation. Indeed, so profound was the mid-century reaction against globalization that the two most populous Asian countries ended up largely cutting themselves off from the global market from the 1950s until the 1970s. Moreover, the last age of globalization had anything but a happy ending. On the contrary, less than a hundred years ago, in the summer of 1914, it ended not with a whimper, but with a deafening bang, as the principal beneficiaries of the globalized economy embarked on the most destructive war the world had ever witnessed.

Why geography matters: three challenges facing America : climate change, the rise of China, and global terrorism

by

Harm J. De Blij

Published 15 Nov 2007

Consider the following quote from a lecture presented at the United States Naval War College by another noted economist, Jeffrey Sachs: "Virtually all of the rich countries of the world are outside the tropics, and virtually all of the poor countries are within them . . . climate, then, accounts for quite a significant proportion of the cross-national and cross-regional disparities of world income" (Sachs, 2000). That would seem to be a reasonable conclusion, but the condition of many of the world's poor countries results from a far more complex combination of circumstances including subjugation, colonialism, exploitation, and suppression that put them at a disadvantage that will long endure and for which climate may not be the significant causative factor Mr. Sachs implies. In any case, while it is true that many of the world's poor countries lie in tropical environs, many others, from Albania to Turkmenistan and from Moldova to North Korea, do not.

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air

by

Richard Holmes

Published 24 Apr 2013

Infuriated natives in fact feature regularly throughout the novel. Long before, Shelley had imagined that ‘the shadow of the first balloon’ crossing Africa would be an instrument of liberation and enlightenment. But for Verne the balloon is more a symbol of imperial command, and scientific superiority.fn24 Cinque semaines is paradoxically a work of colonial exploitation, as much as exploration. It is blatantly – almost naïvely – racist throughout, and observations such as ‘Africans are as imitative as monkeys’ occur regularly throughout the story.51 Balloon height gives the crew not only safety, but also moral superiority. To them, tribesmen are savages, and the wildlife – the elephant, the blue antelope – is there largely for big-game hunting.

The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution

by

Charles R. Morris

Published 1 Jan 2012

In the Northeast, its traditional industries like clocks, textiles, and shoes grew to global scale, along with big-ticket fabrication businesses like Baldwin locomotives, Collins steamships, Hoe printing presses, and the giant Corliss engines. The South, in the meantime, slipped into the position of an internal colony, exploiting its slaves and being exploited in turn by the Northeast and Midwest. Boston and New York controlled much of the shipping, insurance, and brokerage earnings from the cotton trade, while the earnings left over went for midwestern food, tools, and engines shipped down the Mississippi and its branches.

The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good

by

William Easterly

Published 1 Mar 2006

As many as 3.4 million Congolese are still refugees.61 After five centuries of European intervention, the DRC is still today contesting the record for worst and longest misgovernment. Many of the problems since independence are admittedly homegrown. I am not sure that the DRC would be a prosperous place if the Europeans had never come. But after five centuries of European violence, slavery, paternalism, colonialism, exploitation, and aid to prop up bad rulers after independence, the DRC is an extreme example of why the West’s successive interventions of exploitation, colonization, foreign aid, and nation-building have not worked out well. White Mischief If you thought European colonization was bad, decolonization was not much better.

Life Inc.: How the World Became a Corporation and How to Take It Back

by

Douglas Rushkoff

Published 1 Jun 2009

We identify with the plight of abstract corporations more than that of flesh-and-blood human beings. We engage with corporations as role models and saviors, while we engage with our fellow humans as competitors to be beaten or resources to be exploited. Indeed, the now-stalled gentrification of Brooklyn had a good deal in common with colonial exploitation. Of course, the whole thing was done with more circumspection, with more tact. The borough’s gentrifiers steered away from explicitly racist justifications for their actions, but nevertheless demonstrated the colonizer’s underlying agenda: instead of “chartered corporations” pioneering and subjugating an uncharted region of the world, it was hipsters, entrepreneurs, and real-estate speculators subjugating an undesirable neighborhood.

A Line in the Tar Sands: Struggles for Environmental Justice

by

Tony Weis

and

Joshua Kahn Russell

Published 14 Oct 2014

Some of this analysis can be found in a publication entitled Colonization Redux: New Agreements, Old Games, which argues that “while some may see the bewildering proliferation of bilateral FTAs (Free Trade Agreements) and BITs (Bilateral Investment Treaties) throughout the world as a relatively new phenomenon,” in fact this mania “has deep roots,” which “lie in a long history of colonial exploitation, capitalism and imperialism. The classic colonial state was structured for the exploitation and extraction of resources.”11 An Alternative Approach Considering the limitations of previous campaigns against the FIPA with China can help us to achieve more effective analysis and resistance in the future.

A Half-Built Garden

by

Ruthanna Emrys

Published 25 Jul 2022

What will they do, when NASA’s plans don’t perfectly align with theirs?” “A sister can make decisions for her new-hatched brothers, because she knows what they need to survive,” said Cytosine. Athëo glared, ticked off points. “We aren’t ‘new-hatched.’ We aren’t your little brothers, or your children. And we recognize colonial exploitation, no matter how it’s dressed up.” He took a deep breath, visibly trying to center himself. “This is an injustice by all our laws. If you want to be better than that, if you really want to negotiate, you need to start treating us as people worth listening to.” St. Julien wouldn’t look at us, but said: “He’s right.

The Tyranny of Nostalgia: Half a Century of British Economic Decline

by

Russell Jones

Published 15 Jan 2023