Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection

by John Green · 18 Mar 2025 · 158pp · 49,742 words

Leone is poor, you must look at a map of our railroads.” And so I did. The map looks like this: The railroads, built during colonial rule, did not connect people to each other. They connected the mineral-rich areas of Sierra Leone to the coast of Sierra Leone, where those minerals

…

, but this perspective is not supported by strong evidence. In 1950, life expectancy in Britain was sixty-nine. In Sierra Leone, after 150 years of colonial rule, life expectancy was under thirty, relatively similar to the life expectancy of premodern humans who lived five thousand or fifty thousand years ago. In general

The Elements of Power: A Story of War, Technology, and the Dirtiest Supply Chain on Earth

by Nicolas Niarchos · 20 Jan 2026 · 654pp · 170,150 words

was vital in giving Europeans license for their actions.” Bunkeya flies in the face of these assertions. In some ways, it always has. Msiri resisted colonial rule there in the 1880s, even though he was an invader himself. These days, under his distant descendent, it is trying once again to break free

Fortune's Bazaar: the Making of Hong Kong: The Making of Hong Kong

by Vaudine England · 16 May 2023 · 308pp · 122,100 words

had settled in Malacca, on the Malayan Peninsula, and boasted an ancestor who had been leader of the Chinese community, or “Kapitan Cina,” under Dutch colonial rule there. He also had an uncle in Hong Kong since the 1870s, Choa Chee-bee, comprador to a sugar firm. After joining him there in

…

combined with the ambitions of the left wing of the nationalist Kuomintang and of the fledgling Communist Party in Canton, creating a perfect storm for colonial rule. Trouble began in Shanghai in May 1925 when Sikh police under British command in the International Settlement opened fire and killed at least nine Chinese

…

different, then they have stayed. Certainly their idea of Hong Kong as home survived Japanese occupation, World War Two, and even the return of British colonial rule. As Jürgen Osterhammel has made clear, domination by foreigners was not necessarily perceived by its subjects as illegitimate; indeed, in Hong Kong a long history

…

Chinese Gazetteer of the Hong Kong Region. (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1983). Ngo Tak-wing. Hong Kong’s History, State and Society Under Colonial Rule (London: Routledge, 1999). Nocontelli, Carmen. Empires of Love: Europe, Asia and the Making of Early Modern Identity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). Norton-Kyshe

…

History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995). ———. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). ———. Along the Archival Grain—Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). Stone, Lawrence. The

Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong

by Louisa Lim · 19 Apr 2022

’s visual culture. The notes given to reporters spun the King’s work in a pro-China light as “an act of resistance to British colonial rule,” yet such a reading strips the King of the throne he spent his lifetime claiming. One day, years before the protests, I had been to

The Impossible City: A Hong Kong Memoir

by Karen Cheung · 15 Feb 2022 · 297pp · 96,945 words

the ambivalent, apolitical generation that our leaders want us to be? * * * — I came of age alongside a city that had just escaped the shadow of colonial rule. We were told we had until 2047 before China would resume total control. I was brought up on the myth that these fifty years would

The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo--And the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation

by James Donovan · 14 May 2012 · 474pp · 149,248 words

-man royalist force across the arid desolation of northern Mexico. Their destination: that charming town of San Antonio de Béxar, scene of an uprising against colonial rule led by a mixed group of Mexican revolutionaries and Anglo filibusters who had defeated a Spanish army and boldly proclaimed themselves the Republican Army of

Kowloon Tong

by Paul Theroux · 224pp · 63,405 words

its excellent unbiased reporting and its variety of arts programs. A pro-Chinese bureaucrat in Hong Kong slandered RTHK by calling it a "remnant of colonial rule." The chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa, showed considerable sympathy for this view. These ominous noises were drowned out by public opinion in Hong Kong: 90

Among the Islands

by Tim Flannery · 13 Dec 2011 · 228pp · 69,642 words

in grave danger of being killed by people who were their traditional enemies. The twentieth century was just seven years away when, in 1893, British colonial rule was established in the Solomons. Indeed it was with considerable reluctance that the British government declared the Solomon Islands a protectorate, their principal motive being

…

106 Woodlark Island 30–1, 34, 42–3 Solomon Islands 115, 230 bats 137–8, 144–5, 155–6 biodiversity 119 blackbirding 119–20 British colonial rule 120 British law 151–2 cannibalism 120–1, 124, 183 Greater Bukida landmass 181, 183 habitat destruction 184, 188 history of Spanish contact 116–18

The Human City: Urbanism for the Rest of Us

by Joel Kotkin · 11 Apr 2016 · 565pp · 122,605 words

poorly suited for rapid industrial growth. Even today, the manufacturing share of Indian GDP is half that of China.59 In contrast, the absence of colonial rule may have contributed to Tokyo’s rapid ascendancy. There, the wealthy had a great interest in developing world-class transportation, port and industrial facilities, and

Lonely Planet Pocket Seoul

by Lonely Planet · 136pp · 34,624 words

father of King Gojong, started to rebuild it in 1865. Gojong moved in during 1868, but the expensive rebuilding project bankrupted the government. During Japanese colonial rule, the front section of the palace was again destroyed in order to build the enormous Japanese Government General Building. This was itself demolished in the

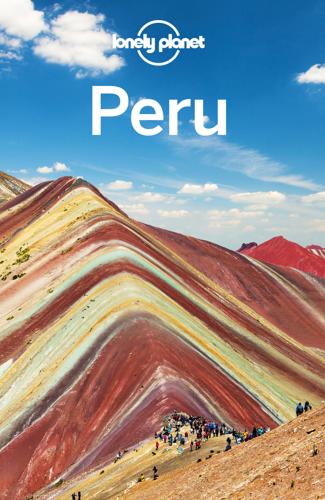

Lonely Planet Peru

by Lonely Planet · 1,166pp · 301,688 words

Icehenge

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 29 May 1994 · 334pp · 103,508 words

AI in Museums: Reflections, Perspectives and Applications

by Sonja Thiel and Johannes C. Bernhardt · 31 Dec 2023 · 321pp · 113,564 words

The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa

by Calestous Juma · 27 May 2017

Amazing Train Journeys

by Lonely Planet · 30 Sep 2018

Lonely Planet Hong Kong

by Lonely Planet

Beautiful Solutions: A Toolbox for Liberation

by Elandria Williams, Eli Feghali, Rachel Plattus and Nathan Schneider · 15 Dec 2024 · 346pp · 84,111 words

The Rough Guide to Cape Town, Winelands & Garden Route

by Rough Guides, James Bembridge and Barbara McCrea · 4 Jan 2018 · 641pp · 147,719 words

Frommer's Mexico 2008

by David Baird, Juan Cristiano, Lynne Bairstow and Emily Hughey Quinn · 21 Sep 2007

The Black Nile: One Man's Amazing Journey Through Peace and War on the World's Longest River

by Dan Morrison · 11 Aug 2010 · 307pp · 102,734 words

The Library: A Fragile History

by Arthur Der Weduwen and Andrew Pettegree · 14 Oct 2021 · 457pp · 173,326 words

The Rough Guide to Mexico

by Rough Guides · 15 Jan 2022

World Travel: An Irreverent Guide

by Anthony Bourdain and Laurie Woolever · 19 Apr 2021 · 366pp · 110,374 words

Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood With Britain in Its Darkest, Finest Hour

by Lynne Olson · 2 Feb 2010 · 564pp · 178,408 words

Picnic Comma Lightning: In Search of a New Reality

by Laurence Scott · 11 Jul 2018 · 244pp · 81,334 words

Lancaster

by John Nichol · 27 May 2020

Empires of the Weak: The Real Story of European Expansion and the Creation of the New World Order

by Jason Sharman · 5 Feb 2019 · 265pp · 71,143 words

Disrupt and Deny: Spies, Special Forces, and the Secret Pursuit of British Foreign Policy

by Rory Cormac · 14 Jun 2018 · 407pp

Lonely Planet Colombia (Travel Guide)

by Lonely Planet, Alex Egerton, Tom Masters and Kevin Raub · 30 Jun 2015

Worn: A People's History of Clothing

by Sofi Thanhauser · 25 Jan 2022 · 592pp · 133,460 words

The City

by Tony Norfield · 352pp · 98,561 words

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by Harsha Walia · 9 Feb 2021

Why Orwell Matters

by Christopher Hitchens · 1 Jan 2002 · 184pp · 54,833 words

The scramble for Africa, 1876-1912

by Thomas Pakenham · 19 Nov 1991 · 1,194pp · 371,889 words

Happy Valley: The Story of the English in Kenya

by Nicholas Best · 9 Aug 2013 · 267pp · 81,108 words

Kicking Awaythe Ladder

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Sep 2000 · 192pp

The Big Oyster

by Mark Kurlansky · 20 Dec 2006

Leading From the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies

by Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer · 14 Apr 2013 · 351pp · 93,982 words

The Rough Guide to Peru

by Rough Guides · 27 Apr 2024 · 960pp · 267,168 words

The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality

by Oded Galor · 22 Mar 2022 · 426pp · 83,128 words

Discover Caribbean Islands

by Lonely Planet

Mexico - Culture Smart!

by Maddicks, Russell;Culture Smart!; · 15 Nov 2023 · 133pp · 37,859 words

Yucatan: Cancun & Cozumel

by Bruce Conord and June Conord · 31 Aug 2000

Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness

by Simone Browne · 1 Oct 2015 · 326pp · 84,180 words

Frommer's Mexico 2009

by David Baird, Lynne Bairstow, Joy Hepp and Juan Christiano · 2 Sep 2008 · 803pp · 415,953 words

Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed

by Jared Diamond · 2 Jan 2008 · 801pp · 242,104 words

Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics

by Michael Kenny and Nick Pearce · 5 Jun 2018 · 215pp · 64,460 words

The Weather of the Future

by Heidi Cullen · 2 Aug 2010 · 391pp · 99,963 words

This Sceptred Isle

by Christopher Lee · 19 Jan 2012 · 796pp · 242,660 words

Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms Everybody

by Helen Pluckrose and James A. Lindsay · 14 Jul 2020 · 378pp · 107,957 words

Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire

by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson · 15 Jan 2019 · 502pp · 128,126 words

The Future Is Asian

by Parag Khanna · 5 Feb 2019 · 496pp · 131,938 words

Diverse Bodies, Diverse Practices: Toward an Inclusive Somatics

by Don Hanlon Johnson · 10 Sep 2018 · 358pp · 106,951 words

Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

by Adom Getachew · 5 Feb 2019

Lonely Planet Sri Lanka

by Lonely Planet

Horizons: The Global Origins of Modern Science

by James Poskett · 22 Mar 2022 · 564pp · 168,696 words

Half In, Half Out: Prime Ministers on Europe

by Andrew Adonis · 20 Jun 2018 · 235pp · 73,873 words

A River in Darkness: One Man's Escape From North Korea

by Masaji Ishikawa · 2 Jan 2018 · 169pp · 54,002 words

The Rough Guide to New York City

by Rough Guides · 21 May 2018

Lonely Planet Kenya

by Lonely Planet

Lonely Planet Cancun, Cozumel & the Yucatan (Travel Guide)

by Lonely Planet, John Hecht and Sandra Bao · 31 Jul 2013

The Rough Guide to South America on a Budget (Travel Guide eBook)

by Rough Guides · 1 Jan 2019 · 1,909pp · 531,728 words

Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain

by Fintan O'Toole · 22 Jan 2018 · 200pp · 64,329 words

The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017

by Rashid Khalidi · 28 Jan 2020 · 413pp · 120,506 words

The Rough Guide to New York City

by Martin Dunford · 2 Jan 2009

Collapse

by Jared Diamond · 25 Apr 2011 · 753pp · 233,306 words

Chasing the Devil: On Foot Through Africa's Killing Fields

by Tim Butcher · 1 Apr 2011 · 347pp · 115,173 words

Bastard Tongues: A Trailblazing Linguist Finds Clues to Our Common Humanity in the World's Lowliest Languages

by Derek Bickerton · 4 Mar 2008

Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire

by Simon Winchester · 31 Dec 1985 · 382pp · 127,510 words

The City: A Global History

by Joel Kotkin · 1 Jan 2005

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 11 Apr 2011 · 740pp · 217,139 words

Not My Father's Son: A Memoir

by Alan Cumming · 6 Oct 2014 · 221pp · 71,449 words

Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Kurlansky · 7 Apr 2008 · 186pp · 57,798 words

The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

by Jonathan Kaufman · 14 Sep 2020 · 415pp · 103,801 words

I You We Them

by Dan Gretton

The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move

by Sonia Shah

Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa

by Dambisa Moyo · 17 Mar 2009 · 225pp · 61,388 words

Ghost Train to the Eastern Star: On the Tracks of the Great Railway Bazaar

by Paul Theroux · 9 Sep 2008 · 651pp · 190,224 words

The Regency Revolution: Jane Austen, Napoleon, Lord Byron and the Making of the Modern World

by Robert Morrison · 3 Jul 2019

Hostile Environment: How Immigrants Became Scapegoats

by Maya Goodfellow · 5 Nov 2019 · 273pp · 83,802 words

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

Insight Guides South America (Travel Guide eBook)

by Insight Guides · 15 Dec 2022

Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History

by Alex von Tunzelmann · 7 Jul 2021 · 337pp · 87,236 words

The Politics of Pain

by Fintan O'Toole · 2 Oct 2019

The Hidden Globe: How Wealth Hacks the World

by Atossa Araxia Abrahamian · 7 Oct 2024 · 336pp · 104,899 words

A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

by Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore · 16 Oct 2017 · 335pp · 89,924 words

After Zionism: One State for Israel and Palestine

by Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed Moor · 14 Jun 2012 · 293pp · 89,712 words

One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility

by Zack Furness and Zachary Mooradian Furness · 28 Mar 2010 · 532pp · 155,470 words

The Challenge for Africa

by Wangari Maathai · 6 Apr 2009 · 288pp · 90,349 words

China into Africa: trade, aid, and influence

by Robert I. Rotberg · 15 Nov 2008 · 651pp · 135,818 words

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by William Easterly · 4 Mar 2014 · 483pp · 134,377 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World

by Oliver Morton · 26 Sep 2015 · 469pp · 142,230 words

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

by Nancy Isenberg · 20 Jun 2016 · 709pp · 191,147 words

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words

In Spite of the Gods: The Rise of Modern India

by Edward Luce · 23 Aug 2006 · 403pp · 132,736 words

A People's History of the United States

by Howard Zinn · 2 Jan 1977 · 913pp · 299,770 words

Lonely Planet Mexico

by John Noble, Kate Armstrong, Greg Benchwick, Nate Cavalieri, Gregor Clark, John Hecht, Beth Kohn, Emily Matchar, Freda Moon and Ellee Thalheimer · 2 Jan 1992

Atlas Obscura: An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders

by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton · 19 Sep 2016 · 1,048pp · 187,324 words

Pacific: Silicon Chips and Surfboards, Coral Reefs and Atom Bombs, Brutal Dictators, Fading Empires, and the Coming Collision of the World's Superpowers

by Simon Winchester · 27 Oct 2015 · 535pp · 151,217 words

Africa: A Biography of the Continent

by John Reader · 5 Nov 1998 · 1,072pp · 297,437 words

"They Take Our Jobs!": And 20 Other Myths About Immigration

by Aviva Chomsky · 23 Apr 2018 · 219pp · 62,816 words

The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program That Shaped Our World

by Vincent Bevins · 18 May 2020 · 393pp · 115,178 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

It's Our Turn to Eat

by Michela Wrong · 9 Apr 2009 · 403pp · 125,659 words

Wealth, Poverty and Politics

by Thomas Sowell · 31 Aug 2015 · 877pp · 182,093 words

Killing Hope: Us Military and Cia Interventions Since World War 2

by William Blum · 15 Jan 2003

The Vietnam War: An Intimate History

by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns · 4 Sep 2017 · 1,433pp · 315,911 words

War Without Mercy: PACIFIC WAR

by John Dower · 11 Apr 1986 · 516pp · 159,734 words

Lonely Planet Cancun, Cozumel & the Yucatan (Travel Guide)

by Lonely Planet, John Hecht and Lucas Vidgen · 31 Jul 2016

Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil

by Nicholas Shaxson · 20 Mar 2007

The Secret World: A History of Intelligence

by Christopher Andrew · 27 Jun 2018

Atlantic: Great Sea Battles, Heroic Discoveries, Titanic Storms & a Vast Ocean of a Million Stories

by Simon Winchester · 27 Oct 2009 · 522pp · 150,592 words

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by Tim Harford · 1 Jan 2008 · 250pp · 88,762 words

An Impeccable Spy: Richard Sorge, Stalin’s Master Agent

by Owen Matthews · 21 Mar 2019 · 589pp · 162,849 words

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by Jason Hickel · 3 May 2017 · 332pp · 106,197 words

A Pipeline Runs Through It: The Story of Oil From Ancient Times to the First World War

by Keith Fisher · 3 Aug 2022

The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood

by Rashid Khalidi · 31 Aug 2006 · 357pp · 112,950 words

Dark Laboratory: On Columbus, the Caribbean, and the Origins of the Climate Crisis

by Tao Leigh. Goffe · 14 Mar 2025 · 441pp · 122,013 words

Persian Gulf Command: A History of the Second World War in Iran and Iraq

by Ashley Jackson · 15 May 2018 · 714pp · 188,602 words

The Rough Guide to Morocco (Travel Guide eBook)

by Rough Guides · 23 Mar 2019 · 1,058pp · 302,829 words

When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World

by Jordan Thomas · 27 May 2025 · 347pp · 105,327 words

Arabs: A 3,000 Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires

by Tim Mackintosh-Smith · 2 Mar 2019

Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, From the Ancients to Fake News

by Eric Berkowitz · 3 May 2021 · 412pp · 115,048 words

Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World's Tallest Skyscrapers

by Jason M. Barr · 13 May 2024 · 292pp · 107,998 words

War of Shadows: Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis From the Middle East

by Gershom Gorenberg · 19 Jan 2021 · 555pp · 163,712 words

Cuba: An American History

by Ada Ferrer · 6 Sep 2021 · 723pp · 211,892 words

The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good

by William Easterly · 1 Mar 2006

On the Grand Trunk Road: A Journey Into South Asia

by Steve Coll · 29 Mar 2009 · 413pp · 128,093 words

Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet

by Jeffrey Sachs · 1 Jan 2008 · 421pp · 125,417 words

Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World

by Kwasi Kwarteng · 14 Aug 2011 · 670pp · 169,815 words

Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

by Jason Stearns · 29 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 139,297 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Brit-Myth: Who Do the British Think They Are?

by Chris Rojek · 15 Feb 2008 · 219pp · 61,334 words

The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam

by Max Boot · 9 Jan 2018 · 972pp · 259,764 words

City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age

by P. D. Smith · 19 Jun 2012

Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 9 Mar 2000 · 1,015pp · 170,908 words

Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart

by Tim Butcher · 2 Jul 2007 · 341pp · 111,525 words

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker · 24 Sep 2012 · 1,351pp · 385,579 words

Imagining India

by Nandan Nilekani · 25 Nov 2008 · 777pp · 186,993 words

England

by David Else · 14 Oct 2010

Engines of War: How Wars Were Won & Lost on the Railways

by Christian Wolmar · 1 Nov 2011 · 410pp · 122,537 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

by Robert Fisk · 2 Jan 2005 · 1,800pp · 596,972 words

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by Branko Milanovic · 10 Apr 2016 · 312pp · 91,835 words

Dictatorland: The Men Who Stole Africa

by Paul Kenyon · 1 Jan 2018 · 513pp · 156,022 words

Railways & the Raj: How the Age of Steam Transformed India

by Christian Wolmar · 3 Oct 2018 · 375pp · 109,675 words

Southeast Asia on a Shoestring Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet · 30 May 2012

The Vast Unknown: America's First Ascent of Everest

by Broughton Coburn · 29 Apr 2013 · 313pp · 95,361 words

Culture and Imperialism

by Edward W. Said · 29 May 1994 · 549pp · 170,495 words

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India

by Shashi Tharoor · 1 Feb 2018 · 370pp · 111,129 words

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century

by Geoffrey Parker · 29 Apr 2013 · 1,773pp · 486,685 words

The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970

by John Darwin · 23 Sep 2009

Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain

by John Darwin · 12 Feb 2013

O Jerusalem

by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre · 31 Dec 1970 · 784pp · 229,648 words

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

by Niall Ferguson · 1 Jan 2002 · 469pp · 146,487 words

Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan

by Herbert P. Bix · 1 Jan 2000 · 1,056pp · 275,211 words

The WikiLeaks Files: The World According to US Empire

by Wikileaks · 24 Aug 2015 · 708pp · 176,708 words

Imperial Legacies

by Jeremy Black; · 14 Jul 2019 · 264pp · 74,688 words

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World

by Laura Spinney · 31 May 2017

Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism

by Elizabeth Becker · 16 Apr 2013 · 570pp · 158,139 words

The Future of War

by Lawrence Freedman · 9 Oct 2017 · 592pp · 161,798 words

Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language

by Robert McCrum · 24 May 2010 · 325pp · 99,983 words

The Edifice Complex: How the Rich and Powerful--And Their Architects--Shape the World

by Deyan Sudjic · 27 Nov 2006 · 441pp · 135,176 words

Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre

by Kim Wagner · 26 Mar 2019

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by Jeremy Paxman · 6 Oct 2011 · 427pp · 124,692 words

Insight Guides Iceland

by Insight Guides · 6 Dec 2024 · 415pp · 110,831 words

Imagine a City: A Pilot's Journey Across the Urban World

by Mark Vanhoenacker · 14 Aug 2022 · 393pp · 127,847 words

Fodor's Essential Belgium

by Fodor's Travel Guides · 23 Aug 2022

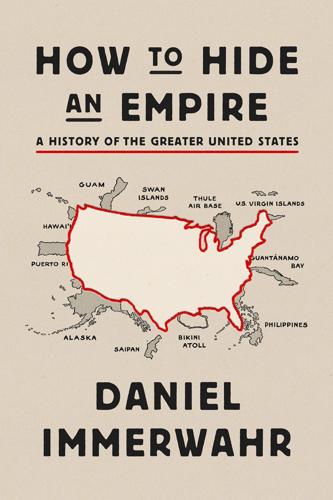

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States

by Daniel Immerwahr · 19 Feb 2019

The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community

by David C. Korten · 1 Jan 2001

Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the World (Politics of Place)

by Tim Marshall · 10 Oct 2016 · 306pp · 79,537 words

The Bin Ladens: An Arabian Family in the American Century

by Steve Coll · 29 Mar 2009 · 769pp · 224,916 words

The Rough Guide to Egypt (Rough Guide to...)

by Dan Richardson and Daniel Jacobs · 1 Feb 2013

Winning the War on War: The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide

by Joshua S. Goldstein · 15 Sep 2011 · 511pp · 148,310 words

Legacy of Empire

by Gardner Thompson · 427pp · 114,531 words

The English

by Jeremy Paxman · 29 Jan 2013 · 364pp · 103,162 words

The Emperor's New Road: How China's New Silk Road Is Remaking the World

by Jonathan Hillman · 28 Sep 2020 · 388pp · 99,023 words

Great Britain

by David Else and Fionn Davenport · 2 Jan 2007

A Game as Old as Empire: The Secret World of Economic Hit Men and the Web of Global Corruption

by Steven Hiatt; John Perkins · 1 Jan 2006 · 497pp · 123,718 words

GDP: The World’s Most Powerful Formula and Why It Must Now Change

by Ehsan Masood · 4 Mar 2021 · 303pp · 74,206 words

China's Good War

by Rana Mitter

Empire of Cotton: A Global History

by Sven Beckert · 2 Dec 2014 · 1,000pp · 247,974 words

The Making of an Atlantic Ruling Class

by Kees Van der Pijl · 2 Jun 2014 · 572pp · 134,335 words

The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible

by Simon Winchester · 14 Oct 2013 · 501pp · 145,097 words

A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East

by David Fromkin · 2 Jan 1989 · 681pp · 214,967 words

The Cold War: A New History

by John Lewis Gaddis · 1 Jan 2005 · 392pp · 106,532 words

Year 501

by Noam Chomsky · 19 Jan 2016

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean

by David Abulafia · 4 May 2011 · 1,002pp · 276,865 words

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

Powers and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 16 Sep 2015

Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty

by Bradley K. Martin · 14 Oct 2004 · 1,509pp · 416,377 words

The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism

by Noam Chomsky · 24 Oct 2014

Age of Anger: A History of the Present

by Pankaj Mishra · 26 Jan 2017 · 410pp · 106,931 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

Lonely Planet China (Travel Guide)

by Lonely Planet and Shawn Low · 1 Apr 2015 · 3,292pp · 537,795 words

The Rough Guide to Jamaica

by Thomas, Polly,Henzell, Laura.,Coates, Rob.,Vaitilingam, Adam.

Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 2006

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

by Francis Fukuyama · 29 Sep 2014 · 828pp · 232,188 words

The Great Surge: The Ascent of the Developing World

by Steven Radelet · 10 Nov 2015 · 437pp · 115,594 words

The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin

by H. W. Brands · 1 Jan 2000 · 961pp · 302,613 words

The Devil's Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America's Secret Government

by David Talbot · 5 Sep 2016 · 891pp · 253,901 words

From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

by Pankaj Mishra · 3 Sep 2012

The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times

by Giovanni Arrighi · 15 Mar 2010 · 7,371pp · 186,208 words

The Cold War: Stories From the Big Freeze

by Bridget Kendall · 14 May 2017 · 559pp · 178,279 words

The Ages of Globalization

by Jeffrey D. Sachs · 2 Jun 2020

Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy

by Daron Acemoğlu and James A. Robinson · 28 Sep 2001

The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism

by Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias · 19 Aug 2019 · 458pp · 116,832 words

The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World

by Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro · 11 Sep 2017 · 850pp · 224,533 words

Artificial Whiteness

by Yarden Katz

About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks

by David Rooney · 16 Aug 2021 · 306pp · 84,649 words

Cyprus Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber · 1 Jan 2010 · 725pp · 221,514 words

Mindf*ck: Cambridge Analytica and the Plot to Break America

by Christopher Wylie · 8 Oct 2019

Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017

by Ian Black · 2 Nov 2017 · 674pp · 201,633 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

The Hidden History of Burma

by Thant Myint-U

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson · 23 Sep 2019 · 809pp · 237,921 words

The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

by William Dalrymple · 9 Sep 2019 · 812pp · 205,147 words

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by Ian Kershaw · 29 Aug 2018 · 736pp · 233,366 words

Caribbean Islands

by Lonely Planet

Venice: A New History

by Thomas F. Madden · 24 Oct 2012 · 466pp · 146,982 words

Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

by Romeo Dallaire and Brent Beardsley · 9 Aug 2004 · 897pp · 210,566 words

Nobody's Perfect: Writings From the New Yorker

by Anthony Lane · 26 Aug 2002 · 879pp · 309,222 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry

by Peter Warren Singer · 1 Jan 2003 · 482pp · 161,169 words

Power Systems: Conversations on Global Democratic Uprisings and the New Challenges to U.S. Empire

by Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian · 1 Nov 2012

Hopes and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Jan 2009

Democracy Incorporated

by Sheldon S. Wolin · 7 Apr 2008 · 637pp · 128,673 words

Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism

by Peter Marshall · 2 Jan 1992 · 1,327pp · 360,897 words

Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq

by Francis Fukuyama · 22 Dec 2005

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by James C. Scott · 8 Feb 1999 · 607pp · 185,487 words

We Were Soldiers Once...and Young: Ia Drang - the Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam

by Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway · 19 Oct 1991 · 496pp · 162,951 words

Frommer's Egypt

by Matthew Carrington · 8 Sep 2008

The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War

by Tim Butcher · 2 Jun 2013 · 302pp · 97,076 words

From Peoples into Nations

by John Connelly · 11 Nov 2019

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

The River of Lost Footsteps

by Thant Myint-U · 14 Apr 2006

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

by J. Bradford Delong · 6 Apr 2020 · 593pp · 183,240 words

A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841-1997

by Steve Tsang · 14 Aug 2007 · 691pp · 169,563 words

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor

by David S. Landes · 14 Sep 1999 · 1,060pp · 265,296 words

1946: The Making of the Modern World

by Victor Sebestyen · 30 Sep 2014 · 476pp · 144,288 words

Lemon Tree: An Arab, a Jew, and the Heart of the Middle East

by Sandy Tolan · 1 Jan 2006 · 488pp · 150,477 words

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

by Naomi Klein · 15 Sep 2014 · 829pp · 229,566 words

Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam

by H. R. McMaster · 7 May 1998 · 615pp · 175,905 words

A Swamp Full of Dollars: Pipelines and Paramilitaries at Nigeria's Oil Frontier

by Michael Peel · 1 Jan 2009 · 241pp · 83,523 words

Rogue States

by Noam Chomsky · 9 Jul 2015

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World

by Tom Wright and Bradley Hope · 17 Sep 2018 · 354pp · 110,570 words

The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics

by William R. Easterly · 1 Aug 2002 · 355pp · 63 words

The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India's New Gilded Age

by James Crabtree · 2 Jul 2018 · 442pp · 130,526 words

Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of Flags

by Tim Marshall · 21 Sep 2016 · 276pp · 78,061 words

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa's Wealth

by Tom Burgis · 24 Mar 2015 · 413pp · 119,379 words

A World Beneath the Sands: The Golden Age of Egyptology

by Toby Wilkinson · 19 Oct 2020

The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977

by Gershom Gorenberg · 1 Jan 2006 · 600pp · 165,682 words

The Cosmopolites: The Coming of the Global Citizen

by Atossa Araxia Abrahamian · 14 Jul 2015 · 138pp · 41,353 words

Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World

by Simon Winchester · 19 Jan 2021 · 486pp · 139,713 words

The Rough Guide to Morocco

by Rough Guides

The Key Man: The True Story of How the Global Elite Was Duped by a Capitalist Fairy Tale

by Simon Clark and Will Louch · 14 Jul 2021 · 403pp · 105,550 words

Owning the Sun

by Alexander Zaitchik · 7 Jan 2022 · 341pp · 98,954 words

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by Karen Hao · 19 May 2025 · 660pp · 179,531 words

A Short Ride in the Jungle

by Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent · 6 Apr 2014 · 316pp · 100,329 words

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge

by Ian Kumekawa · 6 May 2025 · 422pp · 112,638 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

Armed Humanitarians

by Nathan Hodge · 1 Sep 2011 · 390pp · 119,527 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

Thinking Without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953-1975

by Hannah Arendt · 6 Mar 2018 · 653pp · 218,559 words

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by John Darwin · 5 Feb 2008 · 650pp · 203,191 words

Strength in What Remains

by Tracy Kidder · 29 Feb 2000 · 267pp · 91,984 words

Finding Zero: A Mathematician's Odyssey to Uncover the Origins of Numbers

by Amir D. Aczel · 6 Jan 2015 · 204pp · 60,319 words

The Tragedy of Great Power Politics

by John J. Mearsheimer · 1 Jan 2001 · 637pp · 199,158 words

Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order

by Parag Khanna · 4 Mar 2008 · 537pp · 158,544 words

Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2011

by Steve Coll · 23 Feb 2004 · 956pp · 288,981 words

America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism

by Anatol Lieven · 3 May 2010

A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories)

by Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf · 27 Sep 2006

Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century

by Christian Caryl · 30 Oct 2012 · 780pp · 168,782 words

Democracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism Through a Turbulent Century

by Torben Iversen and David Soskice · 5 Feb 2019 · 550pp · 124,073 words

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

by Edward E. Baptist · 24 Oct 2016

The Asian Financial Crisis 1995–98: Birth of the Age of Debt

by Russell Napier · 19 Jul 2021 · 511pp · 151,359 words

The Cold War: A World History

by Odd Arne Westad · 4 Sep 2017 · 846pp · 250,145 words

1968: The Year That Rocked the World

by Mark Kurlansky · 30 Dec 2003 · 538pp · 164,533 words

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

by David Abulafia · 2 Oct 2019 · 1,993pp · 478,072 words

Why the Dutch Are Different: A Journey Into the Hidden Heart of the Netherlands: From Amsterdam to Zwarte Piet, the Acclaimed Guide to Travel in Holland

by Ben Coates · 23 Sep 2015 · 300pp · 99,410 words

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

by David Christian · 21 May 2018 · 334pp · 100,201 words

Spies of No Country: Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel

by Matti Friedman · 5 Mar 2019 · 220pp · 69,282 words

Can Democracy Work?: A Short History of a Radical Idea, From Ancient Athens to Our World

by James Miller · 17 Sep 2018 · 370pp · 99,312 words

England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country – and How to Set Them Straight

by Tom Baldwin and Marc Stears · 24 Apr 2024 · 357pp · 132,377 words

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

by Madhumita Murgia · 20 Mar 2024 · 336pp · 91,806 words

Lonely Planet Belgium & Luxembourg

by Lonely Planet

Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order

by Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright · 23 Aug 2021 · 652pp · 172,428 words

Great American Railroad Journeys

by Michael Portillo · 26 Jan 2017

McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld

by Misha Glenny · 7 Apr 2008 · 487pp · 147,891 words

Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War

by Robert Fisk · 1 Jan 1990 · 1,208pp · 364,966 words

Disaster Capitalism: Making a Killing Out of Catastrophe

by Antony Loewenstein · 1 Sep 2015 · 464pp · 121,983 words

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future

by Laurence C. Smith · 22 Sep 2010 · 421pp · 120,332 words

India's Long Road

by Vijay Joshi · 21 Feb 2017

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality From the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century

by Walter Scheidel · 17 Jan 2017 · 775pp · 208,604 words

The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality

by Branko Milanovic · 15 Dec 2010 · 251pp · 69,245 words

Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians (Updated Edition) (South End Press Classics Series)

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Apr 1999

What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response

by Bernard Lewis · 1 Jan 2001

A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order

by Richard Haass · 10 Jan 2017 · 286pp · 82,970 words

Countdown: Our Last, Best Hope for a Future on Earth?

by Alan Weisman · 23 Sep 2013 · 579pp · 164,339 words

Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities

by Vaclav Smil · 23 Sep 2019

Lonely Planet Egypt

by Lonely Planet · 476pp · 132,840 words

Necessary Illusions

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Sep 1995

Innovation and Its Enemies

by Calestous Juma · 20 Mar 2017

American Secession: The Looming Threat of a National Breakup

by F. H. Buckley · 14 Jan 2020

Shantaram: A Novel

by Gregory David Roberts · 12 Oct 2004 · 1,222pp · 385,226 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Step by Step the Life in My Journeys

by Simon Reeve · 15 Aug 2019 · 309pp · 99,744 words

Super Continent: The Logic of Eurasian Integration

by Kent E. Calder · 28 Apr 2019

Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea's Feminist Movement and What It Means for Women's Rights Worldwide

by Hawon Jung · 21 Mar 2023 · 401pp · 112,589 words

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

by Brian Merchant · 25 Sep 2023 · 524pp · 154,652 words

House of Huawei: The Secret History of China's Most Powerful Company

by Eva Dou · 14 Jan 2025 · 394pp · 110,159 words

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World

by Fareed Zakaria · 5 Oct 2020 · 289pp · 86,165 words

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by Annie Jacobsen · 14 Sep 2015 · 558pp · 164,627 words

Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations

by Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel · 14 Apr 2008

Zero-Sum Future: American Power in an Age of Anxiety

by Gideon Rachman · 1 Feb 2011 · 391pp · 102,301 words

Dreams and Shadows: The Future of the Middle East

by Robin Wright · 28 Feb 2008 · 648pp · 165,654 words

This America: The Case for the Nation

by Jill Lepore · 27 May 2019 · 86pp · 26,489 words

Narcotopia

by Patrick Winn · 30 Jan 2024 · 425pp · 131,864 words

In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan

by Seth G. Jones · 12 Apr 2009 · 566pp · 144,072 words

Discover Great Britain

by Lonely Planet · 22 Aug 2012

Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think

by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund · 2 Apr 2018 · 288pp · 85,073 words

Think Like a Freak

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 May 2014 · 240pp · 65,363 words

Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World

by Timothy Garton Ash · 23 May 2016 · 743pp · 201,651 words

Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey Into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley

by Corey Pein · 23 Apr 2018 · 282pp · 81,873 words

Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security

by Sarah Chayes · 19 Jan 2015 · 352pp · 90,622 words

Supertall: How the World's Tallest Buildings Are Reshaping Our Cities and Our Lives

by Stefan Al · 11 Apr 2022 · 300pp · 81,293 words

Korea--Culture Smart!

by Culture Smart! · 15 Jun 201 · 124pp · 37,476 words

How to Spend a Trillion Dollars

by Rowan Hooper · 15 Jan 2020 · 285pp · 86,858 words

Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990

by Katja Hoyer · 5 Apr 2023

The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being in Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be

by Moises Naim · 5 Mar 2013 · 474pp · 120,801 words

Becoming Kim Jong Un: A Former CIA Officer's Insights Into North Korea's Enigmatic Young Dictator

by Jung H. Pak · 14 Apr 2020 · 395pp · 103,437 words

The Twittering Machine

by Richard Seymour · 20 Aug 2019 · 297pp · 83,651 words

Stuff White People Like: A Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions

by Christian Lander · 5 Aug 2008 · 287pp · 9,386 words

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 23 Dec 2010 · 356pp · 103,944 words

Surveillance Valley: The Rise of the Military-Digital Complex

by Yasha Levine · 6 Feb 2018 · 474pp · 130,575 words

Squid Empire: The Rise and Fall of the Cephalopods

by Danna Staaf · 14 Apr 2017 · 244pp · 69,183 words

The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive During the Collapse of the Welfare State

by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg · 3 Feb 1997 · 582pp · 160,693 words

I'm Judging You: The Do-Better Manual

by Luvvie Ajayi · 12 Sep 2016 · 232pp · 78,701 words

The Shame Machine: Who Profits in the New Age of Humiliation

by Cathy O'Neil · 15 Mar 2022 · 318pp · 73,713 words

Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth

by Ingrid Robeyns · 16 Jan 2024 · 327pp · 110,234 words

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976-1980

by Rick Perlstein · 17 Aug 2020

No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Apr 2015 · 324pp · 93,606 words

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion

by Gareth Stedman Jones · 24 Aug 2016 · 964pp · 296,182 words

Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles

by Ruchir Sharma · 8 Apr 2012 · 411pp · 114,717 words

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived

by Adam Rutherford · 7 Sep 2016

How to Stand Up to a Dictator

by Maria Ressa · 19 Oct 2022

The Global Minotaur

by Yanis Varoufakis and Paul Mason · 4 Jul 2015 · 394pp · 85,734 words

Straight to Hell: True Tales of Deviance, Debauchery, and Billion-Dollar Deals

by John Lefevre · 4 Nov 2014 · 243pp · 77,516 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

The Evolution of God

by Robert Wright · 8 Jun 2009

Tory Nation: The Dark Legacy of the World's Most Successful Political Party

by Samuel Earle · 3 May 2023 · 245pp · 88,158 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

by Jim Al-Khalili · 28 Sep 2010 · 467pp · 114,570 words

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

by Claire L. Evans · 6 Mar 2018 · 371pp · 93,570 words

The Behavioral Investor

by Daniel Crosby · 15 Feb 2018 · 249pp · 77,342 words

Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error

by Kathryn Schulz · 7 Jun 2010 · 486pp · 148,485 words

Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield

by Jeremy Scahill · 22 Apr 2013 · 1,117pp · 305,620 words

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by Ruchir Sharma · 5 Jun 2016 · 566pp · 163,322 words

The Rebel and the Kingdom: The True Story of the Secret Mission to Overthrow the North Korean Regime

by Bradley Hope · 1 Nov 2022 · 257pp · 77,612 words

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World

by Daniel Yergin · 14 May 2011 · 1,373pp · 300,577 words

A United Ireland: Why Unification Is Inevitable and How It Will Come About

by Kevin Meagher · 15 Nov 2016

Revolting!: How the Establishment Are Undermining Democracy and What They're Afraid Of

by Mick Hume · 23 Feb 2017 · 228pp · 68,880 words

Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

by Alain Bertaud · 9 Nov 2018 · 769pp · 169,096 words

Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space

by Adam Higginbotham · 14 May 2024 · 523pp · 204,889 words

Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton · 3 Feb 2002 · 353pp · 148,895 words

The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window Into Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 10 Sep 2007 · 698pp · 198,203 words

The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

by Tim Wu · 14 May 2016 · 515pp · 143,055 words

How to Write Like Tolstoy: A Journey Into the Minds of Our Greatest Writers

by Richard Cohen · 16 May 2016

A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder

by Mark O'Connell · 27 Jun 2023 · 245pp · 82,536 words

Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968

by Thomas E. Ricks · 3 Oct 2022 · 482pp · 150,822 words

Scotland’s Jesus: The Only Officially Non-Racist Comedian

by Frankie Boyle · 23 Oct 2013

Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism

by Sarah Wynn-Williams · 11 Mar 2025 · 370pp · 115,318 words

MacroWikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World

by Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams · 28 Sep 2010 · 552pp · 168,518 words

The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts

by Shane Parrish · 22 Nov 2019 · 147pp · 39,910 words

The Powerhouse: Inside the Invention of a Battery to Save the World

by Steve Levine · 5 Feb 2015 · 304pp · 88,495 words

Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen

by Dan Heath · 3 Mar 2020

We Are Electric: Inside the 200-Year Hunt for Our Body's Bioelectric Code, and What the Future Holds

by Sally Adee · 27 Feb 2023 · 329pp · 101,233 words

Shorter: Work Better, Smarter, and Less Here's How

by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang · 10 Mar 2020 · 257pp · 76,785 words

This Is Only a Test: How Washington D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War

by David F. Krugler · 2 Jan 2006 · 423pp · 115,336 words

The New Economics: A Bigger Picture

by David Boyle and Andrew Simms · 14 Jun 2009 · 207pp · 86,639 words

The America That Reagan Built

by J. David Woodard · 15 Mar 2006