The Elements of Power: A Story of War, Technology, and the Dirtiest Supply Chain on Earth

by Nicolas Niarchos · 20 Jan 2026 · 654pp · 170,150 words

Search of Enemies: A CIA Story (Norton, 1978), 139. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT a rebel named Jonas: This was the British tycoon and corporate raider Roland W. “Tiny” Rowland, who was for many years a go-between for Savimbi and Western governments. When Rowland called on Downing Street to advocate

The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity

by Tim Wu · 4 Nov 2025 · 246pp · 65,143 words

suffer from organizational problems, managers who feud or develop their own agendas, or just the sheer impossibility of coherently organizing so many functions. As the corporate raider T. Boone Pickens once put it, “It’s unusual to find a large corporation that’s efficient. I know about economies of scale and all

The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives

by Ernest Scheyder · 30 Jan 2024 · 355pp · 133,726 words

recalled. “It was a very scary time.”42 Freeport was, in the words of a business columnist, a desperate seller.43 * * * UNDER PRESSURE FROM the corporate raider Carl Icahn, Freeport sold parts of its oil business in September 2016 for $2 billion.44 Not long after, it sold more oil assets—this

King of Capital: The Remarkable Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Steve Schwarzman and Blackstone

by David Carey · 7 Feb 2012 · 421pp · 128,094 words

dogged the buyout business since the 1980s resurfaced. In part it was guilt by association. The industry had come of age in the heyday of corporate raiders, saber-rattling financiers who launched hostile takeover bids and worked to overthrow managements. Buyout firms rarely made hostile bids, preferring to strike deals with management

…

to finance takeovers, would soon provide undreamed-of amounts of new debt for buyout firms. Drexel’s ability to sell junk bonds also sustained the corporate raiders, a rowdy new cast of takeover artists whose bullying tactics shook loose subsidiaries and frequently drove whole companies into the arms of buyout firms. Over

…

horde that emerged on the corporate scene. The corporate establishment and a skeptical press coined a string of equally unflattering names for the new intruders: corporate raiders, buccaneers, bust-up artists, and, most famously, barbarians. Like wolves, the raiders stalked stumbling or poorly run public companies that had fallen behind the herd

…

Peltz were still plying their trade into the second decade of the twenty-first century.) While buyout firms typically enlisted management in their bids, the corporate raiders’ instrument of choice was the uninvited, or hostile, tender offer, a takeover bid that went over the heads of management and appealed directly to shareholders

…

help craft a takeover offer for Sea-Land Corporation, a shipping company that was seeking a friendly buyer after receiving a hostile bid from a corporate raider. However, when it came time to order a fairness opinion—a paid, written declaration that a deal is fair that carries great weight with investors

…

, a top official at USX Corporation, the parent of U.S. Steel. USX was battling for its corporate life with Carl Icahn, the much feared corporate raider. In 1986 Icahn had amassed a nearly 10 percent stake in USX and launched an $8 billion hostile takeover bid. U.S. Steel was three

…

Kravis and Ted Forstmann. Just as Drexel Burnham’s Michael Milken had created the junk-bond market, tapping the public capital markets to finance the corporate raiders and buyout shops of the 1980s, Lee reinvented the bank lending market with his syndicates, which allowed risk to be shared and thereby allowed much

…

in as a white knight—an ally of management—for a company facing a hostile takeover bid. In April 1989, Japonica Partners, a Drexel-backed corporate raider, launched a hostile offer for CNW Corporation, the railroad’s publicly traded parent, after buying up nearly 9 percent of CNW’s shares in the

…

the table and on June 6, Japonica dropped out—collecting a nice profit as the shares rose during the bidding. (Illustrating again that in the corporate raider game you can win by losing.) Although the $1.6 billion price was rich—Blackstone was paying eight times cash flow, twice what it had

…

the CEO and now promised to slash costs and carve up the company. To the man in the street, that was no different from what corporate raiders did. At $31.3 billion, the RJR buyout smashed all records. It was more than three times the size of the next biggest, KKR’s

…

, it did not even have internal mechanisms to gauge the profitability of its divisions or its investments. In 1986, Herbert and Robert Haft, two sometime corporate raiders whose family had owned the Dart Drug chain, thought they could do a better job running Safeway and began buying up the stock as a

…

had. Henry Silverman, who steered the HFS deal for Blackstone, was versed in the hotel franchise business from his years working for the financier and corporate raider Saul Steinberg, for whom he had led a successful LBO of the Days Inn of America chain. Steinberg was one of the early raiders, having

…

banks and, for unsecured junior debt, insurers. Drexel displaced the insurers by acting as a conduit, funneling money from the bond market to growing companies, corporate raiders, and buyout firms. Even before Drexel’s collapse, Jimmy Lee at Chemical had begun to assemble networks of banks to buy parcels of bank loans

…

Randall Smith, “Wasserstein Dies, Leaves Deal-Making Legacy,” WSJ, Oct. 16, 2009; Andrew Ross Sorkin and Michael J. de la Merced, “Obituary—Bruce Wasserstein, 61, Corporate Raider,” NYT, Oct. 16, 2009. 14 Wasserstein Perella soon won: Paltrow, “Nomura Buys Stake”; Michael Quint, “Yamaichi-Lodestar Deal Another Sign of the Trend,” NYT, July

King Icahn: The Biography of a Renegade Capitalist

by Mark Stevens · 31 May 1993 · 414pp · 108,413 words

figure I’d seen on television walk across the village green of my hometown of Bedford, New York. My mind raced. “Is that the feared corporate raider dressed in faded tennis shorts and a wrinkled top walking into the village wine shop? Is it just a look alike? If it’s Icahn

…

W. R. Tappan, Icahn “seemed pleased that we took the time to talk to them about the company.” Icahn had yet to become a feared corporate raider, and the Blasius memo speaks volumes about corporate management’s naiveté concerning his intentions. Carl Icahn “pleased” that executives of a company in which he

…

that situation.” On every front, Icahn vs. Dan River was a clash of cultures, of geography, of insiders and outsiders, of company men and a corporate raider. But most of all, it was a clash between two individuals: one who wanted to keep control over a public corporation and one who wanted

…

that was quoted to him. Internally, Icahn was regarded as a difficult client; at the same time he was respected as the smartest of the corporate raiders, virtually all of whom had links to Drexel. “I knew all the raiders of the era,” said a former senior Drexel executive. “Boone Pickens, Jimmy

…

the real value in the mid-to low-$40s. Once again the management of a major American corporation had acted to protect itself from a corporate raider. As the price of his deal, Pickens signed a standstill agreeing to keep his distance from Phillips for fifteen years. But if the CEO and

…

the other end of the spectrum. In a speech, “The Pirates of Profitability,” Phillips Executive Vice President C. M. Kittrell attacked Icahn and his fellow corporate raiders for raping the shareholders. “Mr. Pickens and Mr. Icahn claim they reaped a windfall for Phillips shareholders. And to some degree that’s true. In

…

? “In Phillips’ case, we will not know the answer to these questions for many years, if ever. “But there’s one thing we know today; corporate raiders who say they represent shareholders . . . represent them, not by proxy but by piracy and they do so at great risk to everyone but themselves. “As

…

“the traveling public and the U.S. international aviation interests. This concern is based at least in part on the reputation of the so-called corporate raiders such as Mr. Icahn. They have the reputation for buying up the shares of an undervalued company and then milking or selling off the assets

…

was in their best interests was never mentioned. Instead, Meyer shifted attention from management’s intransigence by citing the popular notions about the evils of corporate raiders. “... Last month’s American Lawyer published an Icahn memo on his tactics, none of which concerned management of a target and quoted ‘his enemies and

…

this came as a rude awakening to a man who had run off a string of successes in the options business and subsequently as a corporate raider. When he acquired TWA, he assumed that those successes would continue. “When Carl took over, he was very cocky,” said Edward Gehrlein, TWA’s former

…

opportunity to lambast Icahn, expressing the pent-up hostility millions were experiencing as the biggest names in American industry were being ransacked by greenmailers and corporate raiders. This was the flip side of the Roaring Eighties—the wide gulf between the elite who were accumulating wealth and the majority who were losing

…

over U.S. Air, Icahn might be able to prevent or delay government approval of the Piedmont/U.S. Air merger. And as an experienced corporate raider, Icahn knew full well the devastating effect that a failed takeover attempt would have on a company. On the other hand, if Icahn is successful

…

an act of desperation by the defendant Icahn to ‘extricate’ himself from his TWA investment and to permit him to reemerge as American’s preeminent ‘corporate raider.’” In another suit, the IAM went to the crux of the issue, charging that “TWA is already highly-leveraged as a result of its takeover

…

was “beneath” the CEO to do so and in part because it would be viewed as a sign of weakness by Icahn and his fellow corporate raiders. By the time Corry came to power, Icahn’s plan for restructuring USX had evolved as a proposal to divide the company in two by

…

route to a Manhattan theater, Icahn was stricken with fear. Could everything he had worked for be taken from him? Could the widespread resentment of corporate raiders finally be coming home to roost? It seemed as if the establishment he had thumbed his nose at for so long had risen up to

Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

by Jeff Gramm · 23 Feb 2016 · 384pp · 103,658 words

Vanderbilt Line 3. Warren Buffett and American Express: The Great Salad Oil Swindle 4. Carl Icahn versus Phillips Petroleum: The Rise and Fall of the Corporate Raiders 5. Ross Perot versus General Motors: The Unmaking of the Modern Corporation 6. Karla Scherer versus R. P. Scherer: A Kingdom in a Capsule 7

…

General Motors in the 1980s to the well-publicized exploits of today’s fresh-faced hedge fund rabble-rousers. We’ll meet “Proxyteers,” conglomerators, and corporate raiders, and we’ll see how large public companies dealt with them. I’ve chosen eight important interventions from history, featuring original shareholder letters: BENJAMIN GRAHAM

…

letter to Chairman and CEO William Douce, February 4, 1985 After a brief interlude covering Jim Ling, Harold Simmons, and Saul Steinberg, we enter the corporate raider era to watch Carl Icahn’s Milken-funded frontal assault on hapless Phillips Petroleum. ROSS PEROT AND GENERAL MOTORS Ross Perot letter to Chairman and

…

investors ruled the markets, in the ’70s they were at its mercy, and in the ’80s they were “shorn like sheep” in the battles between corporate raiders and entrenched managers. But in time, institutional investors would begin to exert themselves. Today they are quietly teaming up with hedge fund activists to keep

…

you philosophically agree with, but it is the practical result of a corporate governance system based on shareholder-elected boards of directors. Thus, when a corporate raider wins control of Pacific Lumber and clear-cuts thousands of acres of old-growth redwoods, I view this as a regrettable result of unchecked capitalism

…

come to dominate it. And while most of the Proxyteers faded into obscurity, their tactics would be sharpened and used by later generations of conglomerators, corporate raiders, and hedge fund activists. A CONSTANT DOWNWARD SLOPE Robert Young’s first year as chairman of the New York Central lived up to his hype

…

open-market share purchases was the hostile tender offer. When the proxy fight gave way to the hostile tender, the Proxyteer was replaced by the corporate raider. 3 Warren Buffett and American Express: The Great Salad Oil Swindle “Let me assure you that the great majority of stockholders (although perhaps not the

…

growth, which was richly rewarded by Wall Street no matter how it was obtained. The go-go era collapsed quickly, but a new generation of corporate raiders emerged from the ruins. Jim Ling’s 1978 battle with Harold Simmons highlights the hostile raider’s ascendance. “Jimmy Ling the Merger King,” who ran

…

was brewing in academia based on the curious notion that financial markets are near perfect. It altered the debate on hostile takeovers and helped bring corporate raiders out of the shadows and into the boardrooms of America’s largest companies. The efficient market hypothesis came out of the University of Chicago in

…

years ahead of its time, but luckily for him he was not yet thirty years old. It wasn’t long until Steinberg and his fellow corporate raiders would have their day. With help from the efficient market hypothesis and the free market movement of the 1970s, raiders were viewed less as a

…

strong economic growth and Michael Milken’s blank checkbook to fame and riches. 4 Carl Icahn versus Phillips Petroleum: The Rise and Fall of the Corporate Raiders “However, what I strenuously oppose is the Board not allowing the shareholders to receive a fair price for all their shares.” —CARL ICAHN, 1985 ON

…

offer for control. Phillips was Icahn’s fifteenth target in his seven-year career as a raider, and his note to Douce was a classic corporate raider’s “bear hug letter”—an offer to purchase the company, followed by threats should he be ignored. While Icahn had used the same playbook for

…

everyone else, these clashes at the top of our largest companies were Hollywood material. Thirty years earlier, nobody really knew what to make of fledgling corporate raiders picking fights with company CEOs. By the 1980s, such men were known as “masters of the universe.” In many ways, the

…

corporate raiders of the ’80s were not so different from the ’50s Proxyteers. Both groups featured aggressive and motivated young businessmen operating on the fringes of Wall

…

Street. But while the Proxyteers struck fear into the hearts of CEOs with their ability to harness the discontent of public shareholders, the corporate raiders had something much more powerful at their disposal: ready cash. It came from Michael Milken and the vast market he created for new-issue junk

…

times over.10 But even in the mid-2000s, when the entire world binged on cheap capital, nobody lined up to buy bonds from unproven corporate raiders angling for a buying spree.11 That’s quite a testament to Milken’s immense power in the 1980s. Whether Milken’s machine at Drexel

…

good song. When the stock market crashed in 1987, pundits called it the end of an age of debt-fueled excess. They were wrong. The corporate raiders were not dancing on a house of cards. Economic growth in the ’80s was real, the stock market recovered its losses quickly, and the next

…

the decade. He had an unlikely ascent followed by a crash that almost left him ruined. Yet today he is the best known of the corporate raiders. And, to use the metric that probably matters most to him, he is also the richest. Early in his career, Icahn was dismissed as a

…

&A, with a very early version of Martin Lipton’s poison pill and the first “highly confident” letter. The drama began when Boone Pickens, a corporate raider who started his career at Phillips Petroleum, made a run at his former employer in late 1984. SURVIVAL OF THE UNFITTEST One of Carl Icahn

…

the company at $60 per share. Bartlesville was even less welcoming to Pickens the second time around. The town became a symbol of the threat corporate raiders held for small-town America. It was abuzz with residents in “Boone Buster” T-shirts at twenty-four-hour prayer vigils, who believed Pickens would

…

were rightfully indignant at the wave of greenmail buyouts in the early 1980s. They were proof that all the talk from CEOs, as well as corporate raiders, about working on behalf of shareholders was mere posturing. Self-interest reigns supreme, and CEOs jumped at the opportunity to use company funds to free

…

liquidating assets and building the company’s cash reserves. He would later invest Bayswater’s cash in his takeover attempts. ICAHN’S CAREER AS a corporate raider was off and running. He viewed his new investment strategy as “a kind of arbitrage.”29 In 1980, he wrote a memo for prospective investors

…

empire, rattled the junk bond market. Beneath the headline failures, junk default rates were creeping up and would blow open in the 1990–91 recession. Corporate raiders were having a harder time finding compelling bargains, it was more difficult to raise capital to pursue them, and, when they did, the target company

…

, fewer good targets, sophisticated corporate defenses, regulatory pressure, and slowing economic growth. What was different in the ’80s—what ushered in the era of superstar corporate raiders and then made it disappear forever—were the rise and fall of Michael Milken, and the hard-knocks education of large institutional investors. CORNERS CUT

…

-a-lifetime opportunity to raid America’s largest corporations. They wisely took advantage of it and never looked back. WE’RE NOT GONNA TAKE IT Corporate raiders in the 1980s were not only blessed with Michael Milken bearing wads of money; they were aided by passive institutional investors who struggled with their

…

shorn like sheep.”76 He meant it. After Perot, you could no longer count on large institutional shareholders to be pushovers. This helped end the corporate raider era, while encouraging the kind of shareholder activism that dominates markets today. 6 Karla Scherer versus R. P. Scherer: A Kingdom in a Capsule “In

…

methods turned out to be powerful, driving business headlines and shaking up the executive suites of some of America’s most iconic companies. Even superstar corporate raiders like Carl Icahn and Nelson Peltz would soon join their ranks. Hedge fund is a vestigial term that Fortune magazine’s Carol Loomis used in

…

as a letter from Drexel Burnham, but it sounded impressive. Chapman attached his bear hug as an exhibit to a 13D filing, much as a corporate raider would have done in the 1980s. The gambit worked. After announcing that the value of its assets had increased to more than $12 per share

…

up its stock. It used a seemingly rock-solid dividend to seduce income-seeking retail investors into levitating its shares. Taking a page from the corporate raiders’ playbook, Star Gas was also not afraid to leverage itself to the hilt. From its very inception, Star Gas promised investors a healthy dividend of

…

, and Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital took on the multilevel-marketing great white whale, Herbalife, in a fight-to-the-death cage match. WHEREAS CORPORATE RAIDERS busted through gates with hostile tender offers for control and a supporting army of arbitragers, early hedge fund activism was an exercise in persuasion. The

…

great return by owning less than 1% of Microsoft, for example, all Microsoft shareholders need to benefit. But just as with the Proxyteers and the corporate raiders, we shouldn’t get suckered into believing everyone who spouts pro-shareholder populism. A good window into activists’ real intentions with regard to other shareholders

…

wiser voting stockholder. As shareholder activism has become ubiquitous, it looks less and less like a defined movement, as it was in the Proxyteer or corporate raider eras. Instead, it is a fixture in the stock market—it is the reality that when enough shareholders are upset at a board or management

…

. Young, 146. 26. Brooks, 7 Fat Years, 12. Also see Diana B. Henriques, The White Sharks of Wall Street: Thomas Mellon Evans and the Original Corporate Raiders (New York: Scribner, 2000), 133. 27. Karr, Fight for Control, 15. 28. Ibid., 32. 29. Borkin, Robert R. Young, 151, citing New York Times, February

…

Bullish 60s (New York: Wiley, 1999), 238. 54. Ibid. 55. Ibid., 258–59. 4: CARL ICAHN VERSUS PHILLIPS PETROLEUM: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CORPORATE RAIDERS 1. Mark Stevens, King Icahn: The Biography of a Renegade Capitalist (New York: Dutton, 1993), 133. 2. Ibid., 134. 3. Ibid., 150. 4. Ibid., 150

…

of, 72–73 Apple and, xvi, 72, 164 arbitrage and, 77–78, 93, 123, 192 childhood and youth of, 76–77 corporate governance philosophy, 79 corporate raider career beginnings, 78 on director independence, 142 greenmail and, 72, 74, 79, 92, 93–94 hedge fund activism and, 148, 168 investment strategy of, 78

The Taking of Getty Oil: Pennzoil, Texaco, and the Takeover Battle That Made History

by Steve Coll · 12 Jun 2017 · 645pp · 190,680 words

proffered of large, publicly held oil companies such as Getty was persuasive. The domestic oil industry, Pickens said, was already in a state of liquidation; corporate raiders such as himself were only accelerating an inexorable trend. For more than ten years, the largest American oil companies had been unable to replace their

…

. He was distressed above all because the value gap meant that Getty Oil was a prime takeover target for Pickens or some other like-minded corporate raider. What Petersen appreciated better than Gordon Getty did, however, was that the debate on Wall Street and in corporate boardrooms over the oil industry’s

…

Getty Oil. In that position, he had certain legal obligations to protect the company’s shareholders. Turning over secret company documents to a competitive, aggressive corporate raider was hardly consistent with those obligations. What Gordon Getty did not realize when he wrote his hopeful, friendly letter to Sid Petersen on December 24

…

not an open-ended meeting, they said, with a vague agenda. It was a confrontation with Gordon Getty, an attempt to end his dalliances with corporate raiders and royalty trust analysts, all those outside encounters that Winokur described facetiously to Getty Oil executives as “Gordon Getty’s Odyssey of Discovery.” They gathered

…

career was ending for reasons beyond one’s control: the power of Wall Street, the value gap in the oil industry, the greed of a corporate raider. But it was another thing to feel that everything one cherished—career, power, position, community, the lifelong realization of work and ambition—was slipping away

…

secret effort by Petersen, Winokur, and Copley to instigate a family lawsuit against Gordon; the negotiations with Pickens; lingering concerns about the Cullens and other corporate raiders; the million-dollar restructuring study undertaken by Goldman, Sachs, now nearing completion; and the continued thinking and tinkering by Gordon at his Broadway mansion, from

…

for the stock price study. Neither had the board been fully informed about the overtures by Pickens and the contacts by Gordon with other potential corporate raiders. For his part, Gordon continued to act in similar isolation as sole trustee, receiving phone calls and reviewing documents in his basement study, never consulting

…

despite the personal fortune he had made during its halcyon days. He even drafted legislation and testified before Congress, urging that restrictions be imposed on corporate raiders such as Boone Pickens, Carl Icahn, and Irwin “The Liquidator” Jacobs. Lipton’s critics, and there were plenty of them, decried the hypocrisy of his

…

so modestly averted, its jaw slack and withdrawn—the face of a small-town high school principal—and suspect its owner was a ruthless, indefatigable corporate raider, a man intensely driven to acquire not only wealth, but to achieve recognition, political power, and sweeping reform of American industry? And yet it was

…

forward with his plans. Speed was critical; if Getty Oil’s vulnerability was now apparent to Liedtke, then it must also be apparent to other corporate raiders as well. Liedtke’s investment bankers at Lazard Frères advised that a good time to make a surprise hostile takeover announcement was over the Christmas

…

, Pennzoil v. Texaco had again come to life, and once more the puckish Jamail was at the center of things. Carl Icahn, an enormously successful corporate raider who had gained control of TWA Inc. in a hostile takeover, had decided there was potential for profit in Texaco’s travails. After the stock

Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco

by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar · 1 Jan 1990 · 713pp · 203,688 words

mean. On one thing they all agreed: The executives who launched LBOs got filthy rich. “The wolf is not at the door,” Johnson said. No corporate raider was forcing him to do this. “This is simply the option that I think is best for our shareholders. I believe it is a doable

…

Atkins had been brought along by Hugel. Lifting the veil of secrecy was ordinarily enough to kill a developing buyout in its cradle: Once disclosed, corporate raiders or other unwanted suitors were free to make a run at the company before management had a chance to prepare its own bid. Still, Johnson

…

and Roberts had sought and received permission from their investors to secretly accumulate stock in their targets. These so-called toehold investments, a mainstay of corporate raiders like Boone Pickens, would give Kravis negotiating advantage with chief executives and allow the firm to profit from the inevitable run-up in a target

…

, hired in June 1986, was a controversial figure named Daniel Good, who as merger chief at E. F. Hutton had built a thriving business backing corporate raiders. Good, so boundlessly optimistic he was sometimes called “Dan Quixote,” didn’t back four-star investors like Carl Icahn or Boone Pickens. His clients were

…

head, in Wall Street parlance, is intended to leave directors with few options. Disclosing the overture prematurely tends to put the company “in play” for corporate raiders and risks frightening off a certain offer from management. For years boards capitulated and signed merger agreements with the “ambushing” management. Many still did. Wall

…

control of the company, the firm would almost certainly realize a massive gain on its stock holdings. What Strong described was exactly the strategy that corporate raiders such as Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn had been using for years. For a major investment bank to try the same approach was unheard of

…

than an affront to Forstmann’s morals, of course. It was laying waste to his business as well. Because the use of junk bonds allowed corporate raiders to raise money cheaply and easily, it tended to drive up the prices of takeover targets. Forstmann found himself being outbid for companies where once

…

share, or nearly $2.5 billion, of his $90 bid, was a masterstroke Shearson couldn’t easily equal. Two years of backing Dan Good’s corporate raiders had left Cohen’s junk-bond department sadly lacking in the expertise it now needed. The worldwide market for PIK stock, which is convertible into

…

intimidating people, earning him a spot on Fortune’s list of “America’s toughest bosses.” As chief executive of Gulf + Western, he had faced down corporate raiders such as Carl Icahn. He had also overhauled the company from a sprawling conglomerate to a media and financial power. He knew how to value

…

businesses, and he thought $75 a share to be insulting or bungling or both. Bill Anderson of NCR simply didn’t like junk bonds, corporate raiders, or any of the modern folderol that kept business from doing business. At NCR he preached a homespun philosophy of looking after “stakeholders”: employees, suppliers

…

pizza and soft drinks. As we worked on the book, we worried that RJR would be eclipsed by some even bigger and wilder deal. Between corporate raiders, LBO artists, and junk-bond financiers, the whole 1980s business world had gone mad. The barbarians’ next assault could reduce RJR from epic to footnote

Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America's Fifty-Year Fall--And Those Fighting to Reverse It

by Steven Brill · 28 May 2018 · 519pp · 155,332 words

had purchased the bulk of the Stevens operations in 1988 had gone through a 2003 bankruptcy stemming from foreign competition. It was then bought by corporate raider Carl Icahn. Most of its manufacturing is now done overseas, and what remains has been highly automated. The industry as a whole shared the same

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by William D. Cohan · 25 Dec 2015 · 1,009pp · 329,520 words

run of increasing profitability, just as the M&A market exploded in a rare confluence of large strategic mergers and the emergence of well-financed corporate raiders and buyout shops. Nineteen eighty-one was also the year that Felix and Lazard were able to--finally and quietly--put the ITT scandal behind

…

at ITT. While far from the biggest deal, at a mere $1.83 billion, the Perelman-Revlon fight seemed to have it all: an upstart corporate raider, using money borrowed with the help of Michael Milken, trying to buy one of the world's best-known consumer brands, versus a proud corporate

…

Felix directed the firm professionally, too. Felix, of course, was a leading critic of the Wall Street fads of junk bonds, bridge loans, and advising corporate raiders, a source of huge but unsustainable profits at places like First Boston and Drexel Burnham in the 1980s. Michel defended Felix and the firm's

…

that, within four years, added yet another dimension to his growing legend. In this regard, he was taking after Sir James Goldsmith, the famed British corporate raider, who was Stern's distant cousin. In partnership with Goldsmith, Stern bought a number of hotel properties in Vietnam. Accounts vary as to just how

…

as "rather like the Rome city council slapping a demolition order on the Vatican." Bollore was--and remains--the French equivalent of a 1980s-style corporate raider, but unlike most raiders, he also controls his own corporate empire. The indirect investment in Lazard was but one of several Bernheim had recommended Bollore

…

sources--banks, insurance companies, and the public-equity markets--but also Milken pioneered the use of these securities to finance the huge financial ambitions of corporate raiders, like Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens, and of LBO firms, such as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts. Before long, the unknown firm of Drexel Lambert was

…

brought him plenty of notoriety and, not for the first time, a seat at the table opposite Felix. Bruce agreed to advise Ron Perelman, the corporate raider, on his attempt in 1987 to buy Salomon Inc., the parent company of Salomon Brothers, the large Wall Street investment bank focused primarily on bond

…

BEGRUDGING ACCOLADES for Bruce keep coming despite the valid criticism he received in some circles for agreeing to represent, in late November 2005, the billionaire corporate raider Carl Icahn and a group of dissident Time Warner shareholders--who together owned some 3.3 percent of the company--in their very public battle

…

the same form in Felix G. Rohatyn, Twenty-Year Century (New York: Random House, 1984), p. 36. "For the handful of men": Leslie Wayne, "The Corporate Raiders," NYT, July 18, 1982. "These fees don't come from widows and orphans": Ibid. "The level of fees is so different": Ibid. "There's a

The Predators' Ball: The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham and the Rise of the JunkBond Raiders

by Connie Bruck · 1 Jun 1989 · 507pp · 145,878 words

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1990 · 1,335pp · 336,772 words

How Money Became Dangerous

by Christopher Varelas · 15 Oct 2019 · 477pp · 144,329 words

The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It

by Robert B. Reich · 24 Mar 2020 · 154pp · 47,880 words

Buffett

by Roger Lowenstein · 24 Jul 2013 · 612pp · 179,328 words

Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World

by William D. Cohan · 11 Apr 2011 · 1,073pp · 302,361 words

Den of Thieves

by James B. Stewart · 14 Oct 1991 · 706pp · 206,202 words

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by Grace Blakeley · 9 Sep 2019 · 263pp · 80,594 words

For Profit: A History of Corporations

by William Magnuson · 8 Nov 2022 · 356pp · 116,083 words

Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation

by Tom McGrath · 3 Jun 2024 · 326pp · 103,034 words

A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History

by Diana B. Henriques · 18 Sep 2017 · 526pp · 144,019 words

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

When the Wolves Bite: Two Billionaires, One Company, and an Epic Wall Street Battle

by Scott Wapner · 23 Apr 2018 · 302pp · 80,287 words

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception

by George A. Akerlof, Robert J. Shiller and Stanley B Resor Professor Of Economics Robert J Shiller · 21 Sep 2015 · 274pp · 93,758 words

Circle of Greed: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Lawyer Who Brought Corporate America to Its Knees

by Patrick Dillon and Carl M. Cannon · 2 Mar 2010 · 613pp · 181,605 words

Liar's Poker

by Michael Lewis · 1 Jan 1989 · 314pp · 101,452 words

One Up on Wall Street

by Peter Lynch · 11 May 2012

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy

by David Gelles · 30 May 2022 · 318pp · 91,957 words

Cable Cowboy

by Mark Robichaux · 19 Oct 2002

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 7 May 2024 · 470pp · 158,007 words

What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider's Story of Organizational Drift and Its Unintended Consequences

by Steven G. Mandis · 9 Sep 2013 · 413pp · 117,782 words

file:///C:/Documents%20and%...

by vpavan

The Future Was Now: Madmen, Mavericks, and the Epic Sci-Fi Summer Of 1982

by Chris Nashawaty · 251pp · 86,553 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Buy Now, Pay Later: The Extraordinary Story of Afterpay

by Jonathan Shapiro and James Eyers · 2 Aug 2021 · 444pp · 124,631 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

The Smartest Guys in the Room

by Bethany McLean · 25 Nov 2013 · 778pp · 233,096 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

The King of Content: Sumner Redstone's Battle for Viacom, CBS, and Everlasting Control of His Media Empire

by Keach Hagey · 25 Jun 2018 · 499pp · 131,113 words

The Acquirer's Multiple: How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 13 Oct 2017 · 120pp · 33,892 words

House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street

by William D. Cohan · 15 Nov 2009 · 620pp · 214,639 words

Capitalism 3.0: A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons

by Peter Barnes · 29 Sep 2006 · 207pp · 52,716 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

The America That Reagan Built

by J. David Woodard · 15 Mar 2006

Palace Coup: The Billionaire Brawl Over the Bankrupt Caesars Gaming Empire

by Sujeet Indap and Max Frumes · 16 Mar 2021 · 362pp · 116,497 words

Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets

by Brett Scott · 4 Jul 2022 · 308pp · 85,850 words

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter

by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac · 17 Sep 2024

Unreal Estate: Money, Ambition, and the Lust for Land in Los Angeles

by Michael Gross · 1 Nov 2011 · 613pp · 200,826 words

Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final--His Life and the Decisions That Built a Hotel Empire

by Dale van Atta · 14 Aug 2019 · 520pp · 164,834 words

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

The Future of Money

by Bernard Lietaer · 28 Apr 2013

The New Economics: A Bigger Picture

by David Boyle and Andrew Simms · 14 Jun 2009 · 207pp · 86,639 words

Devil's Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump, and the Storming of the Presidency

by Joshua Green · 17 Jul 2017 · 296pp · 78,112 words

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990

by Jonathan Mahler · 11 Aug 2025 · 559pp · 164,804 words

Tomorrow's Capitalist: My Search for the Soul of Business

by Alan Murray · 15 Dec 2022 · 263pp · 77,786 words

More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite

by Sebastian Mallaby · 9 Jun 2010 · 584pp · 187,436 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

740 Park: The Story of the World's Richest Apartment Building

by Michael Gross · 18 Dec 2007 · 601pp · 193,225 words

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom

by Tony Robbins · 18 Nov 2014 · 825pp · 228,141 words

Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local - and Helped Save an American Town

by Beth Macy · 14 Jul 2014 · 473pp · 140,480 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

by Tripp Mickle · 2 May 2022 · 535pp · 149,752 words

Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly

by John Kay · 30 Apr 2010 · 237pp · 50,758 words

Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets

by John McMillan · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 103,988 words

Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol

by Iain Gately · 30 Jun 2008 · 686pp · 201,972 words

Londongrad: From Russia With Cash; The Inside Story of the Oligarchs

by Mark Hollingsworth and Stewart Lansley · 22 Jul 2009 · 471pp · 127,852 words

The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World

by Russell Gold · 7 Apr 2014 · 423pp · 118,002 words

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by Duff McDonald · 24 Apr 2017 · 827pp · 239,762 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies

by Barry Meier · 17 May 2021 · 319pp · 89,192 words

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

by Anand Giridharadas · 27 Aug 2018 · 296pp · 98,018 words

Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and How They Broke Capitalism

by Richard Brooks · 23 Apr 2018 · 398pp · 105,917 words

Collision Course: Carlos Ghosn and the Culture Wars That Upended an Auto Empire

by Hans Gremeil and William Sposato · 15 Dec 2021 · 404pp · 126,447 words

The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry

by William K. Black · 31 Mar 2005 · 432pp · 127,985 words

Trillions: How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever

by Robin Wigglesworth · 11 Oct 2021 · 432pp · 106,612 words

Mastering Private Equity

by Zeisberger, Claudia,Prahl, Michael,White, Bowen, Michael Prahl and Bowen White · 15 Jun 2017

After the New Economy: The Binge . . . And the Hangover That Won't Go Away

by Doug Henwood · 9 May 2005 · 306pp · 78,893 words

The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources

by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy · 25 Feb 2021 · 565pp · 134,138 words

All the Devils Are Here

by Bethany McLean · 19 Oct 2010 · 543pp · 157,991 words

Confidence Game: How a Hedge Fund Manager Called Wall Street's Bluff

by Christine S. Richard · 26 Apr 2010 · 459pp · 118,959 words

The Fissured Workplace

by David Weil · 17 Feb 2014 · 518pp · 147,036 words

Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris

by Richard Kluger · 1 Jan 1996 · 1,157pp · 379,558 words

Frenemies: The Epic Disruption of the Ad Business

by Ken Auletta · 4 Jun 2018 · 379pp · 109,223 words

Sabotage: The Financial System's Nasty Business

by Anastasia Nesvetailova and Ronen Palan · 28 Jan 2020 · 218pp · 62,889 words

A Colossal Failure of Common Sense: The Inside Story of the Collapse of Lehman Brothers

by Lawrence G. Mcdonald and Patrick Robinson · 21 Jul 2009 · 430pp · 140,405 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

Sunbelt Blues: The Failure of American Housing

by Andrew Ross · 25 Oct 2021 · 301pp · 90,276 words

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by Alec Ross · 13 Sep 2021 · 363pp · 109,077 words

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by Satyajit Das · 15 Nov 2006 · 349pp · 134,041 words

Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America's Eyeballs

by Gina Keating · 10 Oct 2012 · 347pp · 91,318 words

Why Wall Street Matters

by William D. Cohan · 27 Feb 2017 · 113pp · 37,885 words

Outliers

by Malcolm Gladwell · 29 May 2017 · 230pp · 71,320 words

Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis

by David Boyle · 15 Jan 2014 · 367pp · 108,689 words

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Invention of Donald Trump and the Erosion of America

by Sarah Kendzior · 6 Apr 2020

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

Vassal State

by Angus Hanton · 25 Mar 2024 · 277pp · 81,718 words

Bernie Madoff, the Wizard of Lies: Inside the Infamous $65 Billion Swindle

by Diana B. Henriques · 1 Aug 2011 · 598pp · 169,194 words

Power Hungry: The Myths of "Green" Energy and the Real Fuels of the Future

by Robert Bryce · 26 Apr 2011 · 520pp · 129,887 words

The Oil and the Glory: The Pursuit of Empire and Fortune on the Caspian Sea

by Steve Levine · 23 Oct 2007 · 568pp · 162,366 words

The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World's Most Coveted Microchip

by Stephen Witt · 8 Apr 2025 · 260pp · 82,629 words

The Asylum: The Renegades Who Hijacked the World's Oil Market

by Leah McGrath Goodman · 15 Feb 2011 · 553pp · 168,111 words

Crapshoot Investing: How Tech-Savvy Traders and Clueless Regulators Turned the Stock Market Into a Casino

by Jim McTague · 1 Mar 2011 · 280pp · 73,420 words

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India

by Shashi Tharoor · 1 Feb 2018 · 370pp · 111,129 words

Making It in America: The Almost Impossible Quest to Manufacture in the U.S.A. (And How It Got That Way)

by Rachel Slade · 9 Jan 2024 · 392pp · 106,044 words

The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Sep 2019

How to Form Your Own California Corporation

by Anthony Mancuso · 2 Jan 1977

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

Chokepoint Capitalism

by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow · 26 Sep 2022 · 396pp · 113,613 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

Conspiracy of Fools: A True Story

by Kurt Eichenwald · 14 Mar 2005 · 992pp · 292,389 words

The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

by David Callahan · 1 Jan 2004 · 452pp · 110,488 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

Drowning in Oil: BP & the Reckless Pursuit of Profit

by Loren C. Steffy · 5 Nov 2010 · 305pp · 79,356 words

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

by Joshua B. Freeman · 27 Feb 2018 · 538pp · 145,243 words

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 28 Jan 2020 · 408pp · 108,985 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

Dead Companies Walking

by Scott Fearon · 10 Nov 2014 · 232pp · 71,965 words

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Mar 2016 · 366pp · 94,209 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right

by Jane Mayer · 19 Jan 2016 · 558pp · 168,179 words

Democracy for Sale: Dark Money and Dirty Politics

by Peter Geoghegan · 2 Jan 2020 · 388pp · 111,099 words

Trillion Dollar Triage: How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic---And Prevented Economic Disaster

by Nick Timiraos · 1 Mar 2022 · 357pp · 107,984 words

The Crux

by Richard Rumelt · 27 Apr 2022 · 363pp · 109,834 words

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski · 5 Mar 2019 · 202pp · 62,901 words

The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age

by Tim Wu · 14 Jun 2018 · 128pp · 38,847 words

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Bezonomics: How Amazon Is Changing Our Lives and What the World's Best Companies Are Learning From It

by Brian Dumaine · 11 May 2020 · 411pp · 98,128 words

The Intelligent Investor (Collins Business Essentials)

by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig · 1 Jan 1949 · 670pp · 194,502 words

The Decline and Fall of IBM: End of an American Icon?

by Robert X. Cringely · 1 Jun 2014 · 232pp · 71,024 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

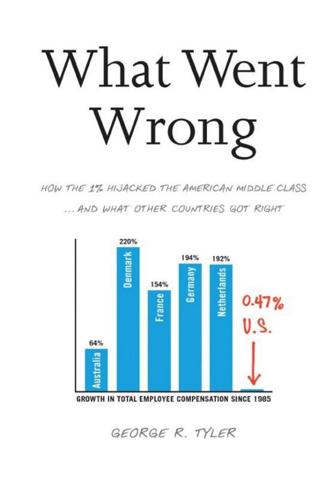

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Trust: The Social Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 1995 · 585pp · 165,304 words

The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India's New Gilded Age

by James Crabtree · 2 Jul 2018 · 442pp · 130,526 words

The Self-Made Billionaire Effect: How Extreme Producers Create Massive Value

by John Sviokla and Mitch Cohen · 30 Dec 2014 · 252pp · 70,424 words

Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

by Bruce C. N. Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul D. Sonkin and Michael van Biema · 26 Jan 2004 · 306pp · 97,211 words

Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time

by Howard Schultz and Dori Jones Yang

Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

by R. Christopher Whalen · 7 Dec 2010 · 488pp · 144,145 words

Binge Times: Inside Hollywood's Furious Billion-Dollar Battle to Take Down Netflix

by Dade Hayes and Dawn Chmielewski · 18 Apr 2022 · 414pp · 117,581 words

Concentrated Investing

by Allen C. Benello · 7 Dec 2016

Unscripted: The Epic Battle for a Media Empire and the Redstone Family Legacy

by James B Stewart and Rachel Abrams · 14 Feb 2023 · 521pp · 136,802 words

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America

by George Packer · 4 Mar 2014 · 559pp · 169,094 words

In-N-Out Burger

by Stacy Perman · 11 May 2009 · 454pp · 122,612 words

Jim Henson: The Biography

by Brian Jay Jones · 23 Sep 2013 · 702pp · 215,002 words

Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 7 Nov 2017 · 346pp · 89,180 words

Chicken: The Dangerous Transformation of America's Favorite Food

by Steve Striffler · 24 Jul 2007 · 208pp · 51,277 words

The Secret World of Oil

by Ken Silverstein · 30 Apr 2014 · 233pp · 73,772 words

Street Fighters: The Last 72 Hours of Bear Stearns, the Toughest Firm on Wall Street

by Kate Kelly · 14 Apr 2009 · 258pp · 71,880 words

The Vanishing Middle Class: Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy

by Peter Temin · 17 Mar 2017 · 273pp · 87,159 words

The Land Grabbers: The New Fight Over Who Owns the Earth

by Fred Pearce · 28 May 2012 · 379pp · 114,807 words

Swimming With Sharks: My Journey into the World of the Bankers

by Joris Luyendijk · 14 Sep 2015 · 257pp · 71,686 words

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by Danielle Dimartino Booth · 14 Feb 2017 · 479pp · 113,510 words

Why We Can't Afford the Rich

by Andrew Sayer · 6 Nov 2014 · 504pp · 143,303 words

The Wisdom of Finance: Discovering Humanity in the World of Risk and Return

by Mihir Desai · 22 May 2017 · 239pp · 69,496 words

When the Iron Lady Ruled Britain

by Robert Chesshyre · 15 Jan 2012 · 434pp · 150,773 words

The Theft of a Decade: How the Baby Boomers Stole the Millennials' Economic Future

by Joseph C. Sternberg · 13 May 2019 · 336pp · 95,773 words

Overhaul: An Insider's Account of the Obama Administration's Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry

by Steven Rattner · 19 Sep 2010 · 394pp · 124,743 words

Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming

by Mckenzie Funk · 22 Jan 2014 · 337pp · 101,281 words

Money Men: A Hot Startup, a Billion Dollar Fraud, a Fight for the Truth

by Dan McCrum · 15 Jun 2022 · 361pp · 117,566 words

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge

by Ian Kumekawa · 6 May 2025 · 422pp · 112,638 words

The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything

by Jason Kelly · 10 Sep 2012 · 274pp · 81,008 words

Shipping Greatness

by Chris Vander Mey · 23 Aug 2012 · 231pp · 71,248 words

The Ripple Effect: The Fate of Fresh Water in the Twenty-First Century

by Alex Prud'Homme · 6 Jun 2011 · 692pp · 167,950 words

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition

by Charles Eisenstein · 11 Jul 2011 · 448pp · 142,946 words

Global Financial Crisis

by Noah Berlatsky · 19 Feb 2010

The New Rules of War: Victory in the Age of Durable Disorder

by Sean McFate · 22 Jan 2019 · 330pp · 83,319 words

Rush Hour: How 500 Million Commuters Survive the Daily Journey to Work

by Iain Gately · 6 Nov 2014 · 352pp · 104,411 words

The Little Book of Hedge Funds

by Anthony Scaramucci · 30 Apr 2012 · 162pp · 50,108 words

The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry

by Jon Ronson · 12 May 2011 · 274pp · 70,481 words

Underwater: How Our American Dream of Homeownership Became a Nightmare

by Ryan Dezember · 13 Jul 2020 · 279pp · 87,875 words

Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 1 Jan 2001 · 111pp · 1 words

The Frackers: The Outrageous Inside Story of the New Billionaire Wildcatters

by Gregory Zuckerman · 5 Nov 2013 · 483pp · 143,123 words

Money Mavericks: Confessions of a Hedge Fund Manager

by Lars Kroijer · 26 Jul 2010 · 244pp · 79,044 words

Who Needs the Fed?: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America's Central Bank

by John Tamny · 30 Apr 2016 · 268pp · 74,724 words

The New Geography of Jobs

by Enrico Moretti · 21 May 2012 · 403pp · 87,035 words

The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science

by Paul Krugman · 18 Feb 2010 · 162pp · 51,473 words

Shoe Dog

by Phil Knight · 25 Apr 2016 · 399pp · 122,688 words

The Five-Year Party: How Colleges Have Given Up on Educating Your Child and What You Can Do About It

by Craig Brandon · 17 Aug 2010 · 282pp · 26,931 words

Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia

by Peter Pomerantsev · 11 Nov 2014 · 251pp · 80,243 words

The Mysterious Mr. Nakamoto: A Fifteen-Year Quest to Unmask the Secret Genius Behind Crypto

by Benjamin Wallace · 18 Mar 2025 · 431pp · 116,274 words

Flight of the WASP

by Michael Gross · 562pp · 177,195 words

They All Came to Barneys: A Personal History of the World's Greatest Store

by Gene Pressman · 2 Sep 2025 · 313pp · 107,586 words

Boom: Mad Money, Mega Dealers, and the Rise of Contemporary Art

by Michael Shnayerson · 20 May 2019 · 552pp · 163,292 words

The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation Is the Key to an Abundant Future

by Jeff Booth · 14 Jan 2020 · 180pp · 55,805 words

Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel

by Max Blumenthal · 27 Nov 2012 · 840pp · 224,391 words

Filthy Rich: A Powerful Billionaire, the Sex Scandal That Undid Him, and All the Justice That Money Can Buy: The Shocking True Story of Jeffrey Epstein

by James Patterson, John Connolly and Tim Malloy · 10 Oct 2016 · 234pp · 63,844 words

The Wisdom of Frugality: Why Less Is More - More or Less

by Emrys Westacott · 14 Apr 2016 · 287pp · 80,050 words

Practical Ext JS Projects With Gears

by Frank Zammetti · 7 Jul 2009 · 602pp · 207,965 words

Political Ponerology (A Science on the Nature of Evil Adjusted for Political Purposes)

by Andrew M. Lobaczewski · 1 Jan 2006 · 396pp · 116,332 words

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words