The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America

by John Fabian Witt · 14 Oct 2025 · 735pp · 279,360 words

-Saxon past, before mass immigration from southern and eastern Europe, before Black migration to the North, before the flu pandemic of 1919, and before the creative destruction of modern capitalism. Harding’s campaign platform of normalcy had done nothing to arrest galloping economic inequality. With each passing year, the economy’s wealthiest

Gambling Man

by Lionel Barber · 3 Oct 2024 · 424pp · 123,730 words

of life where only the fittest survive. Then again, if single companies were to last several hundred years, how did that prospect square with the creative destruction intrinsic to modern capitalism? At the same time, the salmon-spawning analogy spoke to Masa’s own investment philosophy, which involved placing bets on every

Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley

by Jacob Silverman · 9 Oct 2025 · 312pp · 103,645 words

its civic-minded, if rarely elaborated upon, mission of “changing the world.” More often the tech industry seems focused on the ways they could wreak creative destruction. The catastrophic promise of AI has practically become part of the sales pitch. In their ominous warnings of unchecked artificial intelligence escaping Pandora’s box

…

to refashion any industry in their image, from taxis to healthcare to real estate to the entire federal government. Their worldview upheld the pretense that creative destruction and technological innovation were synonymous with progress. If expertise was worthless—because the experts themselves represented the corruption of the ancien régime—then tech was

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

history of GDP, both nominal and real, for the early years of the republic (see appendix).6 We draw on that work throughout this book. CREATIVE DESTRUCTION Creative destruction is the principal driving force of economic progress, the “perennial gale” that uproots businesses—and lives—but that, in the process, creates a more productive

…

capitalist concern has got to live in.” Yet for all his genius, Schumpeter didn’t go beyond brilliant metaphors to produce a coherent theory of creative destruction: modern economists have therefore tried to flesh out his ideas and turn metaphors into concepts that acknowledge political realities, which is to say, the world

…

. It was a time in which the federal government focused overwhelmingly on protecting property rights and enforcing contracts rather than on “taming” the process of creative destruction. Thanks to relentless innovation the unit cost (a proxy for output per hour) of Bessemer steel fell sharply, reducing its wholesale price from 1867 to

…

similar cascade of improvements in almost every area of life produced a doubling of living standards in a generation. The most obvious way to drive creative destruction is to produce more powerful machines. A striking number of the machines that have revolutionized productivity look like improvised contraptions. Cyrus McCormick’s threshing machine

…

percentage points a year to real GDP growth. That added 10.6 percent to the level of real GDP in 1899. An additional aspect of creative destruction is the reduction in transportation costs. Cold-rolled steel sheet is worth more on a car located in a car dealership than rolling off a

…

ever closer together within an integrated circuit in order to produce ever-greater amounts of computing capacity. THE CUNNING OF HISTORY In the real world, creative destruction seldom works with the smooth logic of Moore’s law. It can take a long time for a new technology to change an economy: the

…

could ring up payments by 30 percent and reduced labor requirements of cashiers and baggers by 10 to 15 percent. THE DOWNSIDE OF CREATIVE DESTRUCTION The destructive side of creative destruction comes in two distinct forms: the destruction of physical assets as they become surplus to requirements, and the displacement of workers as old

…

jobs are abandoned. To this should be added the problem of uncertainty. The “gale of creative destruction” blows away old certainties along with old forms of doing things: nobody knows which assets will prove to be productive in the future and which

…

bubbles that can pop, sometimes with dangerous consequences. Partly because people are frightened of change and partly because change produces losers as well as winners, creative destruction is usually greeted by what Max Weber called “a flood of mistrust, sometimes of hatred, above all of moral indignation.”16 The most obvious form

…

, and managerial capitalism by a more entrepreneurial capitalism. Resistance can come from business titans as well as labor barons. One of the great paradoxes of creative destruction is that people who profit from it one moment can turn against it the next: worried that their factories will become obsolete or their competitors

…

by electric shocks or set cities on fire.17 ENTER THE POLITICIANS America has been better at both the creative and the destructive side of creative destruction than most other countries: it has been better at founding businesses and taking those businesses to scale, but it has also been better at

…

greatest entrepreneurs, including Charles Goodyear, R. H. Macy, and H. J. Heinz, suffered from repeated business failures before finally making it. America’s appetite for creative destruction has many roots. The fact that America is such a big country meant that people were willing to pull up stakes and move on: from

…

least it avoided stagnation. The country’s political system has powerfully reinforced these geographical and cultural advantages. The biggest potential constraint on creative destruction is political resistance. The losers of creative destruction tend to be concentrated while the winners tend to be dispersed. Organizing concentrated people is much easier than organizing dispersed ones. The

…

have taken a more mature approach, admitting that creation and destruction are bound together, but claiming to be able to boost the creative side of creative destruction while eliminating the destructive side through a combination of demand management and wise intervention. The result has usually been disappointing: stagnation, inflation, or some other

…

on the idea that government was the problem rather than the solution. But can America continue to preserve its comparative advantage in the art of creative destruction? That is looking less certain. The rate of company creation is now at its lowest point since the 1980s. More than three-quarters of

…

value of hierarchy and authority and encouraged people to rely on their own judgment. For all their differences, these two traditions were both friendly toward creative destruction: they taught Americans to challenge the established order in pursuit of personal betterment and to question received wisdom in pursuit of rational understanding. Shortage of

…

was more than five times the amount invested in canals.40 The railway boom proceeded in a very American way. There was a lot of creative destruction: railways quickly killed canals because rails could carry fifty times as much freight and didn’t freeze over in winter. There was a lot of

…

” and “brings the noisy world into the midst of our slumberous peace.”45 The third revolution was an information revolution. Central to the process of creative destruction is knowledge of what combination of what resources yields maximum gains in living standards. Information-starved Americans recognized the importance of the old adage that

…

was the only one who was born to the purple, and he massively increased the power of his bank. One of the striking things about creative destruction is that it can affect members of the same family in very different ways: the very force that made Andrew Carnegie the world’s richest

…

improvement in living standards for all. These men were entrepreneurial geniuses who succeeded in turning the United States into one of the purest laboratories of creative destruction the world has seen: men who grasped that something big but formless was in the air and gave that something form and direction, men who

…

that tested America’s belief in equality of opportunity. America’s new plutocrats were increasingly keen on flaunting their wealth as Schumpeter’s spirit of creative destruction gave rise to Thorstein Veblen’s disease of conspicuous consumption. They were also increasingly keen on adopting European airs and graces. They competed to get

…

that boasted 175,000 square feet and 250 rooms, as well as farms, a village, a church, and agricultural laborers. RISING DISCONTENT The storm of creative destruction that swept across the country in the aftermath of the Civil War whipped up great concentrations of anger as well as wealth. The anger began

…

them on price. They were also the mail-order stores that by the late 1920s were forced to open physical stores, often in the suburbs. Creative destruction brought an inevitable political reaction: the losers banded together and eventually persuaded the Federal Trade Commission to pass retail price maintenance. HENRY FORD VERSUS ALFRED

…

ideal King-beaver.” Yet even Hoover’s abilities were soon to be tested beyond breaking point. The United States had enjoyed the bright side of creative destruction with three decades of barely punctuated economic growth culminating in seven years of unprecedented prosperity. It was about to experience the dark side. Seven THE

…

depression of 1893. But it was still possible in those days of small government and fatalistic politics for the government to stand pat and let creative destruction take its course. By the 1930s, people expected the government to “do something” but didn’t know what that “something” should be. The federal

…

retarded re-employment.” FDR responded to the complaints with a series of adjustments that had the perverse effect of making the contraption ever more complicated. Creative destruction was nowhere to be seen. The Supreme Court did FDR an unexpected (and certainly unacknowledged) favor by ruling that much of the NRA was unconstitutional

…

Microsoft in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1975 and Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak founded Apple in 1976. And America had not lost its talent for creative destruction, even during the decade of malaise. America’s pharmaceutical industry escaped the general decline in management quality: Pfizer continued to invest heavily in R&D

…

be recombined with talent in imaginative new ways. Jack Welch became the most celebrated chief executive of the era because of his willingness to apply creative destruction to one of America’s most storied companies. He began his two-decade reign (1981–2001) with unflinching corporate brutality in pursuit of his belief

…

, left Fairchild and recruited Andy Grove to join them. More than anywhere else in America, Silicon Valley was a living embodiment of the principle of creative destruction as old companies died and new ones emerged, allowing capital, ideas, and people to be reallocated. From the mid-1970s onward, the IT revolution went

…

America’s declining dynamism. Twelve AMERICA’S FADING DYNAMISM THIS BOOK HAS REPEATEDLY shown that America’s greatest comparative advantage has been its talent for creative destruction. America was colonized by pioneers and forged by adventurers who were willing to take unusual risks in pursuit of a better life. Arjo Klamer once

…

—a barrier that offers stability and pricing power. Yet this highly productive America exists alongside a much more stagnant country. Look at any measure of creative destruction, from geographical mobility to company creation to tolerance of disruption, and you see that it is headed downward. The United States is becoming indistinguishable from

…

other mature slow-growth economies such as Europe and Japan in its handling of creative destruction: a “citadel society,” in Klamer’s phrase, in which large parts of the citadel are falling into disrepair. The Census Bureau reports that geographical mobility

…

teeth. Short? American life expectancy is more than twice what it was at the birth of the republic. THE PROBLEM WITH CREATIVE DESTRUCTION The central mechanism of this progress has been creative destruction: the restless force that disequilibrates every equilibrium and discombobulates every combobulation. History would be simple (if a little boring) if progress

…

competition. “All failed companies are the same,” Peter Thiel, the founder of PayPal, explains in Zero to One (2014), “they failed to escape competition.”6 Creative destruction cannot operate without generating unease: the fiercer the gale, the greater the unease. Settled patterns of life are uprooted. Old industries are destroyed. Hostility to

…

creative destruction is usually loudest on the left. You can see it in protests against Walmart opening stores, factory owners closing factories, bioengineers engineering new products. But

…

obvious than the benefits. The benefits tend to be diffuse and long-term while the costs are concentrated and up front. The biggest winners of creative destruction are the poor and marginal. Joseph Schumpeter got to the heart of the matter: “Queen Elizabeth [I] owned silk stockings. The capitalist achievement does not

…

unemployed silk workers put out of business by the silk-making factories than the millions of silk stockings. This leads to the second problem: that creative destruction can become self-negating. By producing prosperity, capitalism creates its own gravediggers in the form of a comfortable class of intellectuals and politicians

…

easier for the victims of “destruction” to band together and demand reform than it is for the victors to band together. The “perennial gale” of creative destruction thus encounters a “perennial gale” of political opposition. People link arms to protect threatened jobs and save dying industries. They denounce capitalists for their ruthless

…

greed. The result is stagnation: in trying to tame creative destruction, for example by preserving jobs or keeping factories open, they end up killing it. Entitlements crowd out productive investments. Regulations make it impossible to create

…

new companies. By trying to have your cake and eat it, you end up with less cake. The third problem is that creative destruction can sometimes be all destruction and no creation. This most frequently happens in the world of money. It’s impossible to have a successful capitalist

…

the like allocate society’s savings to the perceived most productive industries and the most productive firms within those industries. At its best, finance is creative destruction in its purest form: capital is more fleet-footed and ruthless than any other factor of production. At its worst, finance is pure destruction. Financial

…

best borrowers. Credit dries up. Companies collapse. People are laid off. Again the process is self-reinforcing: panic creates contraction; contraction creates further panic. FROM CREATIVE DESTRUCTION TO MASS PROSPERITY The best place to study the first problem—the fact that costs are more visible than benefits—is in the transition from

…

from the end of the Civil War to America’s entry into the First World War because it was the country’s greatest era of creative destruction. Railways replaced horses and carts for long-distance transport. Steel replaced iron and wood. Skyscrapers reached to the heavens. The years just before the

…

up all this discontent into successful political movements. The Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution introduced an income tax for the first time. Yet all this creative destruction nevertheless laid the foundation for the greatest improvement in living standards in history. Technological innovations reduced the cost of inputs into the economy (particularly oil

…

, 246 Council of Economic Advisers, 275, 302–3 Countrywide Financial, 378 cowboys, 113, 116 Cowen, Tyler, 4 Cox, Michael, 431 Crain, Nicole and Mark, 413 creative destruction, 12, 14–21, 209, 324, 389, 390 downside of, 21–23 to mass prosperity, 426–32 political resistance and, 24–26 problems with, 420–26

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

4, 2001: “The books of various gurus have singled out the company as paragon of good management, for LEADING THE REVOLUTION (Gary Hamel, 2000), practising CREATIVE DESTRUCTION (Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan, 2001), devising STRATEGY THROUGH SIMPLE RULES (Kathy Eisenhardt and Donald Sull, 2001), winning the WAR FOR TALENT (Ed Michaels, 1998

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

the growth dynamic. On the one hand, the profit motive stimulates newer, better or cheaper products and services through a continual process of innovation and ‘creative destruction’. At the same time, the market for these goods relies on an expanding consumer demand, driven by a complex social logic. These two factors combine

…

that it is in fact novelty, the process of innovation, that is vital in driving economic growth. Capitalism proceeds, he said, through a process of ‘creative destruction’. New technologies and products continually emerge and overthrow existing technologies and products. Ultimately, this means that even successful companies cannot survive simply through cost minimisation

…

.20 The Venezuelan economist Carlota Perez describes how creative destruction has given rise to successive ‘epochs of capitalism’. Each technological revolution ‘brings with it, not only a full revamping of the productive structure, but eventually

…

care if individual companies go to the wall. Indeed that must inevitably be the destruction part of the process of creative destruction. It’s a different matter, though, if the process of creative destruction stops, because without it economic expansion eventually stops as well. The role of the entrepreneur – as visionary – is critical here

…

. But so is the role of the investor. It is only through the continuing cycle of investment that creative destruction is possible. When credit dries up, so does innovation. And when innovation stalls, according to Schumpeter, so does the long-term potential for growth itself

…

been a useful way of organising human society to ensure that people’s material needs are catered for. But what does this continual cycle of creative destruction have to do with human flourishing? Does this self-perpetuating system really contribute to prosperity in any meaningful sense? Isn’t there a point at

…

growth. But this imperative is now so strong that it seems to undermine the interests of those it’s supposed to serve. The cycles of creative destruction become ever more frequent. Product lifetimes plummet as durability is designed out of consumer goods and obsolescence is designed in. Quality is sacrificed relentlessly to

…

in firms. The restless desire of the ‘empty self’ is the perfect complement for the restless innovation of the entrepreneur. The production of novelty through creative destruction drives (and is driven by) the appetite for novelty in consumers. Taken together these two self-reinforcing processes are exactly what is needed to drive

…

self is motivated in part by the anxiety of the empty self. Social comparison is driven by the desire to be situated favourably in society. Creative destruction is haunted by the fear of being left behind in the competition for consumer markets. Thrive or die is the maxim of the jungle. It

…

Health Care Doesn’t (Baumol) 171, 172 Costa Rica 74, 74, 76 countercyclical spending 181–2, 182, 188 crafts/craft economies 147, 149, 170, 171 creative destruction 104, 112, 113, 116–17 creativity 8, 79; and consumerism 113, 116; future visions 142, 144, 147, 158, 171, 200, 220 see also novelty/innovation

Vanishing New York

by Jeremiah Moss · 19 May 2017 · 479pp · 140,421 words

, Max. The City’s End: Two Centuries of Fantasies, Fears, and Premonitions of New York’s Destruction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010. ———. The Creative Destruction of Manhattan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. Patterson, Clayton, ed. Resistance: A Radical Social and Political History of the Lower East Side. New York

…

and the Rise of the American Empire (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008). 75–76“Irredeemable rookeries” speech by Robert Moses, found in Max Page, Creative Destruction of Manhattan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), noted as typescript of speech by Robert Moses at the Commodore Hotel, November 14, 1956, Municipal Reference

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

and ignored the long-term effects on the whole community.18 He attacked what he called the ‘fetish’ of full employment. Schumpeter’s idea of ‘creative destruction’ must be allowed to operate unhindered, Hazlitt wrote, as it was as important for the health of an economy that dying industries be allowed to

…

low rates would boost corporate investment. But White suggested firms were actually investing less. Furthermore, ultra-easy money was responsible for the misallocation of capital. Creative destruction was thwarted. ‘It is possible,’ White concluded, ‘that easy money conditions actually impede, rather than encourage, the reallocation of capital from less to more productive

…

‘process of industrial mutation … that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.’1 That phrase stuck. If Schumpeter is widely remembered today, it’s because he owns the intellectual copyright on

…

creative destruction – the evolutionary process by which new technologies and business methods displace older, less efficient ways of doing things. Schumpeter’s borrowing from Darwin’s theory

…

of natural selection is as important to our understanding of the nature of capitalism as Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’. Most discussion of creative destruction revolves around the adoption of new technologies, the roles played by entrepreneurs as harbingers of change and by competition in selecting the most efficient businesses

…

businesses, Hadley added, interest ensures the ‘productive forces of the community are better utilized’.2 Schumpeter himself saw interest as arising from the profits of creative destruction. ‘The true function of interest,’ he wrote, ‘is, so to speak, the brake, or governor’ on economic activity.3 A ‘necessary brake’, in Schumpeter’s

…

of production. Time is money. Entrepreneurs who save time in production, who bring goods most quickly to market, emerge as winners in the game of creative destruction. Interest rations capital.fn1 From this perspective, interest is not a deadweight but a spur to efficiency – a hurdle that determines whether an investment is

…

– the last tempo being ‘very, very slow’. At zero interest rates, the economy progresses at the solemn pace of a funeral march. The forces of creative destruction are at their most unremitting during sharp economic downturns. In the panic phase, the cost of borrowing soars.fn2 Sales dry up. Bankers call in

…

riches of nations can be measured by the violence of the crises which they experience,’ opined the nineteenth-century French economist Clément Juglar.13 Once creative destruction is taken into account, Juglar’s observation doesn’t appear so puzzling. Some economists take a ‘pit-stop’ view of recessions, seeing them as periods

…

labour costs, the PIIGS were going to have to embrace deep structural reforms. Unemployment in Spain climbed to Great Depression levels. Schumpeter’s forces of creative destruction were about to be unleashed, big time. Then along came Mario Draghi (a former economics professor, Goldman Sachs managing director and, lately, Governor of the

…

fridge makers to car manufacturing – that lingered for years. Corporate profits and returns on capital declined. Productivity growth suffered. Deflation lingered. With the forces of creative destruction stilled, Japan Inc. appeared increasingly sclerotic. Capital-constrained Japanese banks, aided and abetted by the Ministry of Finance in Tokyo, are usually blamed for the

…

disbelief cracked before the IPO got underway, however, and some $40 billion was wiped off its private market value. A tale not so much of creative destruction, but of capital destruction on a grand scale. THE PRODUCTIVITY PUZZLE Economies on both sides of the Atlantic experienced a collapse in productivity growth in

…

enter sectors plagued with excess capacity and miserable returns. Zombies slowed the adoption of new technologies and business practices. As Phil Mullan in his book Creative Destruction writes: When too many resources are stuck in low productivity areas and in zombie businesses – businesses that are too weak to invest in their underlying

…

is but never can be stationary.’54 He spoke too soon. The lowest interest rates in history put the brake on Schumpeter’s evolutionary process. Creative destruction was replaced by unnatural selection and capital destruction. As the tempo of business life slowed, the economy returned to a stationary state. FIREFIGHTERS AND ARSONISTS

…

of ecological systems, which also suffer at times from misguided, if well-intentioned, interference by public bodies. The part played by economic downturns in promoting creative destruction has a parallel in nature. Fires have an important role in regenerating forests. Trees are stressed when woodlands become overgrown, which renders them vulnerable to

…

Serfdom, Hayek’s Austrian contemporary Joseph Schumpeter published an equally notable book. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) is best known for introducing the idea of creative destruction (as discussed in Chapter 10). Schumpeter believed that a capitalist economic system would atrophy if it ever became stationary. At which point, Schumpeter predicted, profits

…

–1500 (Baltimore, Md, 1997). Muldrew, Craig, The Economy of Obligation: The Culture of Credit and Social Relations in Early Modern England (Basingstoke, 1998). Mullan, Phil, Creative Destruction: How to Start an Economic Renaissance (Bristol, 2017). Muller, Jerry, The Tyranny of Metrics (Princeton, 2018). Muroi, Kazuo, ‘Interest Calculations in Babylonian Mathematics: New Interpretations

…

and Refet Gurkanayak showed a strong statistical correlation between investment in physical capital and the growth rate of output per worker (cited by Phil Mullan, Creative Destruction: How to Start an Economic Renaissance (Bristol, 2017), p. 44). 49. Richard Peach and Charles Steindel, ‘Low Productivity Growth: The Capital Formation Link’, Liberty Street

…

that a third of the productivity slowdown in the UK since the financial crisis was due to the slower reallocation of resources between firms; Mullan, Creative Destruction, p. 159. 51. Ibid., p. 42. The OECD claimed that ‘it has become relatively easier for firms that do not adopt the latest technologies to

…

marginal costs in New Economy, 127–8; Marxist-Leninist critique of, 159–60, 217*, 298; primacy of finance in modern era, 138–9; process of ‘creative destruction’, xx, 140–43, 143*, 153, 296–7; Proudhon on, xvii; role of risk in, 220, 298; Schumpeter on, 140, 153, 296–7; Adam Smith on

…

, 108; calculating of how much due, 6, 14; central banks’ influence on long-term rates, 133, 134–5; concealed in bills of exchange, 24; and ‘creative destruction’ idea, 140–43, 143*; determining of rate level, 10–13; feedback loop with globalization, 260–61, 311; as hard to predict, 310–11; Hazlitt on

…

Railroad, 159 New Paradigm (Goldilocks Economy), 111 new technologies: in 1920s, 89, 90, 96, 100; in 1930s USA, 142–3; in China, 276, 284; and ‘creative destruction’ idea, 140; and demand for capital, 125, 126, 127; digital, 127–8, 149–50, 151–2, 176, 177, 179, 204, 276, 283; digital currencies concept

…

, 82, 92, 312 Schäuble, Wolfgang, 299 Scheidel, Walter, 204 Schumpeter, Joseph, 16, 32, 46, 95, 218; Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942), 126, 140, 296–7; ‘creative destruction’ idea, xx, 140–43, 153, 296–7; on deflation, 100; History of Economic Analysis, xviii; view of intellectuals, 297 Schwartz, Anna, 98, 99, 105, 116

…

of a natural rate of interest. fn4 This viewpoint is forcefully expressed by Boston University’s Perry Mehrling: ‘Credit is critical for the process of “creative destruction” that is the source of capitalism’s dynamism, because it provides the crucial mechanism that allows the new to bid resources away from the old

Defending the Free Market: The Moral Case for a Free Economy

by Robert A. Sirico · 20 May 2012 · 267pp · 70,250 words

Aid That Doesn’t The Moral Appeal of Good Work A Theology of Enterprise Suggestions for Further Reading CHAPTER 4 - Why the “Creative Destruction” of Capitalism Is More Creative than Destructive Creative Destruction, Creative Flourishing Globalization, Christianity, and Culture Globalization and Coercive Destruction Globalization and Culture Suggestions for Further Reading CHAPTER 5 - Why Greed

…

, 2009). PovertyCure website (www.povertycure.org). Robert Sirico, The Entrepreneurial Vocation (Acton Institute, 2001). CHAPTER 4 Why the “Creative Destruction” of Capitalism Is More Creative than Destructive Q: It’s easy to talk about “creative destruction” when it’s not your job, your family, or your town being destroyed. Unemployment ruins lives. Shouldn’t

…

my depth. What he was saying made sense to me on a technical level, but all my intuitions cried out against it. It looked horrible. Creative Destruction, Creative Flourishing I relate this story as an illustration of the fact that sometimes what appears to be beaten back and damaged is really healthy

…

and preparing for new growth. This is the case with what economists call creative destruction—the phenomenon whereby old skills, companies, and sometimes entire industries are eclipsed as new methods and businesses take their place

…

. Creative destruction is seen in layoffs, downsizing, the obsolescence of firms, and, sometimes, serious injury to the communities that depend on them. It looks horrible, and, especially

…

though every ditch digger is going to lose his job when bulldozers come on line. Let’s not forget the creative and progressive part of creative destruction. Technological advance does not destroy ditch diggers, even the ones who lose their jobs. It places them behind the controls of bulldozers or in factories

…

a false nostalgia blind us to the good of human progress. If we were to eliminate the positive results of even a hundred years of creative destruction—eliminate them overnight—the result would be the swift death of literally billions of human beings, since the resources available to civilization a hundred years

…

to live in an alternate reality, and if we are to preserve it we need to recognize that it is only when the process of creative destruction is allowed that new jobs, new skills, new ways of leveraging human energy can spring up and create the opportunities that previous generations never even

…

going to help us. What is needed, rather, is an economically informed perspective. We need to look more closely at all the factors contributing to creative destruction, and consider both the positives and negatives of a creative market economy. That involves not only attending to the people thrown out of work as

…

industries and technologies change but also thinking about what would happen to the people if there were no creative destruction. Once we realize that we have to attend to all of the long-range consequences, then we can start coming at the problems generated by

…

creative destruction from the most productive angle. The challenge for all who are concerned with promoting a free and virtuous society is to minimize the damage done

…

like the holly bush that is never pruned. Of course, workers and other economic players who are caught in the midst of this drama of creative destruction aren’t landscape plants; they are human persons and members of families. Every job is filled by a human being of inestimable inherent dignity and

…

effect on their co-workers or the consumers of their products. There is something fundamentally alarming about that. To resist the creative destruction inherent in a dynamic economy is only to replace creative destruction with a slow destruction without creativity. This isn’t theory. It’s the present reality in the United States. For

…

, and setbacks is a recipe for decline. Globalization, Christianity, and Culture It is impossible to talk about creative destruction without talking about the increasingly interconnected global economy. The global economy is where we see creative destruction writ large, and in recent years many Americans have had to come face to face with the destructive

…

Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir Brooks, Arthur bureaucracy business, environment for global business morality of poverty and profits and small business “Business as Mission,” C capital capitalism “creative destruction” and global capitalism greed and Caritas in Veritate Catholicism Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good Center for Faith and Public Life Centesimus Annus central

…

competition Congress consumerism consumption Constitution, The Consumer Reports contraception contracts Copernicus Cornwall Declaration on Environmental Stewardship cost-benefit analysis Council for Environmental Stewardship Cox, Harvey “creative destruction,” Cronyism CT scans D Dalrymple, Theodore de Soto, Hernando de Sales, Francis de Tocqueville, Alexis “Dead, The,” Decalogue Declaration of Independence, the Department of Health

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

examples, they show how institutional developments, sometimes based on very accidental circumstances, have had enormous consequences. The openness of a society, its willingness to permit creative destruction, and the rule of law appear to be decisive for economic development.” —Kenneth J. Arrow, Nobel laureate in economics, 1972 “The authors convincingly show

…

than two thousand years of political and economic history. Imagine that they weave their ideas into a coherent theoretical framework based on limiting extraction, promoting creative destruction, and creating strong political institutions that share power, and you begin to see the contribution of this brilliant and engagingly written book.” —Scott E.

…

opposition to economic growth has its own, unfortunately coherent, logic. Economic growth and technological change are accompanied by what the great economist Joseph Schumpeter called creative destruction. They replace the old with the new. New sectors attract resources away from old ones. New firms take business away from established ones. New technologies

…

income was from landholdings or from trading privileges they enjoyed thanks to monopolies granted and entry barriers imposed by monarchs. Consistent with the idea of creative destruction, the spread of industries, factories, and towns took resources away from the land, reduced land rents, and increased the wages that landowners had to

…

just a process of more and better machines, and more and better educated people, but also a transformative and destabilizing process associated with widespread creative destruction. Growth thus moves forward only if not blocked by the economic losers who anticipate that their economic privileges will be lost and by the political

…

somewhat, even if not completely, inclusive economic institutions. Many societies with extractive political institutions will shy away from inclusive economic institutions because of fear of creative destruction. But the degree to which the elite manage to monopolize power varies across societies. In some, the position of the elite could be sufficiently secure

…

develop military technologies and even pull ahead of the United States in the space and nuclear race for a short while. But this growth without creative destruction and without broad-based technological innovation was not sustainable and came to an abrupt end. In addition, the arrangements that support economic growth under

…

oceans just at the wrong time, when Ming emperors decided in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries that increased long-distance trade and the creative destruction that it might bring would be likely to threaten their rule. In India, institutional drift worked differently and led to the development of a

…

either because of infighting over the spoils of extraction, leading to the collapse of the regime, or because the inherent lack of innovation and creative destruction under extractive institutions puts a limit on sustained growth. How the Soviets ran hard into these limits will be discussed in greater detail in the

…

getting locally autonomous groups under control. But absolutism persisted until the First World War, and reform efforts were thwarted by the usual fear of creative destruction and the anxiety among elite groups that they would lose economically or politically. While Ottoman reformers talked of introducing private property rights to land in

…

, a commodity coveted worldwide. The production of sugar based on gangs of slaves was certainly not “efficient,” and there was no technological change or creative destruction in these societies, but this did not prevent them from achieving some amount of growth under extractive institutions. The situation was similar in the Soviet

…

not to have changed. Building and artistic techniques became much more sophisticated over time, but in total there was little innovation. There was no creative destruction. But there were other forms of destruction as the wealth that the extractive institutions created for the k’uhul ajaw and the Maya elite led

…

different in nature from growth created under inclusive institutions, however. Most important, it is not sustainable. By their very nature, extractive institutions do not foster creative destruction and generate at best only a limited amount of technological progress. The growth they engender thus lasts for only so long. The Soviet experience gives

…

toward fully inclusive institutions looked unstoppable. But there was a tension in all this. Economic growth supported by the inclusive Venetian institutions was accompanied by creative destruction. Each new wave of enterprising young men who became rich via the commenda or other similar economic institutions tended to reduce the profits and economic

…

was based on relatively high agricultural productivity, significant tribute from the provinces, and long-distance trade, but it was not underpinned by technological progress or creative destruction. The Romans inherited some basic technologies, iron tools and weapons, literacy, plow agriculture, and building techniques. Early on in the Republic, they created others:

…

used existing technology, though the Romans perfected it. There could be some economic growth without innovation, relying on existing technology, but it was growth without creative destruction. And it did not last. As property rights became more insecure and the economic rights of citizens followed the decline of their political rights, economic

…

is good news, until the government decides that it is not interested in technological development—an all-too-common occurrence due to the fear of creative destruction. The great Roman writer Pliny the Elder relates the following story. During the reign of the emperor Tiberius, a man invented unbreakable glass and

…

they will often resist and try to stop such innovations. Thus society needs newcomers to introduce the most radical innovations, and these newcomers and the creative destruction they wreak must often overcome several sources of resistance, including that from powerful rulers and elites. Prior to seventeenth-century England, extractive institutions were the

…

, as shown in the last two chapters, especially when they’ve contained inclusive elements, as in Venice and Rome. But they did not permit creative destruction. The growth they generated was not sustained, and came to an end because of the absence of new innovations, because of political infighting generated by

…

by Dionysius Papin, a French physicist and inventor. The story of Papin’s invention is another example of how, under extractive institutions, the threat of creative destruction impeded technological change. Papin developed a design for a “steam digester” in 1679, and in 1690 he extended this into a piston engine. In

…

to cotton, as Foster did. Newcomers were needed to develop and use the new technologies. The rapid expansion of cotton decimated the wool industry—creative destruction in action. Creative destruction redistributes not simply income and wealth, but also political power, as William Lee learned when he found the authorities so unreceptive to his invention

…

moved policy in the direction favored by these newly represented interests; in 1846 they managed to get the hated Corn Laws repealed, demonstrating again that creative destruction meant a redistribution not just of income, but also of political power. And naturally, changes in the distribution of political power in time would

…

further redistribution of income. It was the inclusive nature of English institutions that allowed this process to take place. Those who suffered from and feared creative destruction were no longer able to stop it. WHY IN ENGLAND? The Industrial Revolution started and made its biggest strides in England because of her

…

the same urges as any other person. They wanted to block others from entering their businesses and competing against them and feared the process of creative destruction that might put them out of business, as they had previously bankrupted others. But after 1688 this became harder to accomplish. In 1775 Richard

…

can master literacy. This threatened to undermine the existing status quo, where knowledge was controlled by elites. The Ottoman sultans and religious establishment feared the creative destruction that would result. Their solution was to forbid printing. THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION created a critical juncture that affected almost every country. Some nations, such as

…

particularly pernicious form of Russian serfdom. Absolutism was not the only type of political institution preventing industrialization. Though absolutist regimes were not pluralistic and feared creative destruction, many had centralized states, or at least states that were centralized enough to impose bans on innovations such as the printing press. Even today,

…

weak, political centralization are two different barriers to the spread of industry. But they are also connected; both are kept in place by fear of creative destruction and because the process of political centralization often creates a tendency toward absolutism. Resistance to political centralization is motivated by reasons similar to resistance to

…

the scheme went nowhere because Emperor Francis again simply said no. The opposition to industry and steam railways stemmed from Francis’s concern about the creative destruction that accompanied the development of a modern economy. His main priorities were ensuring the stability of the extractive institutions over which he ruled and

…

corrupted and eventually turn into a class as miserable as they are dangerous for their masters. Just as with Francis I, Nicholas feared that the creative destruction unleashed by a modern industrial economy would undermine the political status quo in Russia. Urged on by Nicholas, Kankrin took specific steps to slow

…

usual logic of extractive institutions. As most rulers presiding over extractive institutions, the absolutist emperors of China opposed change, sought stability, and in essence feared creative destruction. This is best illustrated by the history of international trade. As we have seen, the discovery of the Americas and the way international trade was

…

trading relations worthless or even worse. The reasoning of the Ming and Qing states for opposing international trade is by now familiar: the fear of creative destruction. The leaders’ primary aim was political stability. International trade was potentially destabilizing as merchants were enriched and emboldened, as they were in England during

…

other absolutist regimes—for example, in Austria-Hungary, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and China, though in these cases the rulers, because of fear of creative destruction, not only neglected to encourage economic progress but also took explicit steps to block the spread of industry and the introduction of new technologies that

…

playing field: Thomas Edison’s 1880 patent for the lightbulb Records of the Patent and Trademark Office; Record Group 241; National Archives Economic losers from creative destruction: machine-breaking Luddites in early-nineteenth-century Britain Mary Evans Picture Library/Tom Morgan Consequences of a complete lack of political centralization in Somalia REUTERS

…

people of Western European countries, while black South Africans were scarcely richer than those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. This economic growth without creative destruction, from which only the whites benefited, continued as long as revenues from gold and diamonds increased. By the 1970s, however, the economy had stopped

…

of economic growth. Australia and the United States could industrialize and grow rapidly because their relatively inclusive institutions would not block new technologies, innovation, or creative destruction. Not so in most of the other European colonies. Their dynamics would be quite the opposite of those in Australia and the United States. Lack

…

monarchs and by aristocracies whose major source of income was from their landholdings or from trading privileges they enjoyed thanks to prohibitive entry barriers. The creative destruction that would be wrought by the process of industrialization would erode the leaders’ trading profits and take resources and labor away from their lands.

…

its responsibility was for the development of infrastructure, such as ports and roads, but as in Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Sierra Leone, this often threatened creative destruction and could have destabilized the system. Therefore, the development of infrastructure, rather than being implemented, was often resisted. For example, the development of a port

…

more inclusive political institutions following the Glorious Revolution and the French Revolution. The first was new merchants and businessmen wishing to unleash the power of creative destruction from which they themselves would benefit; these new men were among the key members of the revolutionary coalitions and did not wish to see

…

in the middle of a boom in the world prices of these commodities. Like all such experiences of growth under extractive institutions, it involved no creative destruction and no innovation. And it was not sustainable. Around the time of the First World War, mounting political instability and armed revolts induced the

…

that growth under extractive institutions will not be sustained, for two key reasons. First, sustained economic growth requires innovation, and innovation cannot be decoupled from creative destruction, which replaces the old with the new in the economic realm and also destabilizes established power relations in politics. Because elites dominating extractive institutions fear

…

institutions. Despite the recent emphasis in China on innovation and technology, Chinese growth is based on the adoption of existing technologies and rapid investment, not creative destruction. An important aspect of this is that property rights are not entirely secure in China. Every now and then, just like Dai, some entrepreneurs

…

heavy industry. Such growth was feasible partly because there was a lot of catching up to be done. Growth under extractive institutions is easier when creative destruction is not a necessity. Chinese economic institutions are certainly more inclusive than those in the Soviet Union, but China’s political institutions are still

…

about the case on the New York Times and Financial Times Web sites. Because of the party’s control over economic institutions, the extent of creative destruction is heavily curtailed, and it will remain so until there is radical reform in political institutions. Just as in the Soviet Union, the Chinese

…

political institutions in China, though likely to continue for a while yet, will not translate into sustained growth, supported by truly inclusive economic institutions and creative destruction. Second, contrary to the claims of modernization theory, we should not count on authoritarian growth leading to democracy or inclusive political institutions. China, Russia,

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Leading From the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies

by Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer · 14 Apr 2013 · 351pp · 93,982 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber · 29 Oct 2024 · 292pp · 106,826 words

Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms

by David S. Evans and Richard Schmalensee · 23 May 2016 · 383pp · 81,118 words

Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right

by Jennifer Burns · 18 Oct 2009 · 495pp · 144,101 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

by David Moon, Patrick Ruffini, David Segal, Aaron Swartz, Lawrence Lessig, Cory Doctorow, Zoe Lofgren, Jamie Laurie, Ron Paul, Mike Masnick, Kim Dotcom, Tiffiniy Cheng, Alexis Ohanian, Nicole Powers and Josh Levy · 30 Apr 2013 · 452pp · 134,502 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

Innovation and Its Enemies

by Calestous Juma · 20 Mar 2017

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

by J. Bradford Delong · 6 Apr 2020 · 593pp · 183,240 words

Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet

by Jeffrey Sachs · 1 Jan 2008 · 421pp · 125,417 words

Wealth and Poverty: A New Edition for the Twenty-First Century

by George Gilder · 30 Apr 1981 · 590pp · 153,208 words

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Mar 2016 · 366pp · 94,209 words

Hacking Capitalism

by Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City

by Richard Sennett · 9 Apr 2018

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation Is the Key to an Abundant Future

by Jeff Booth · 14 Jan 2020 · 180pp · 55,805 words

More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded)

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 1 Jan 2006 · 348pp · 83,490 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies

by Geoffrey West · 15 May 2017 · 578pp · 168,350 words

That Used to Be Us

by Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum · 1 Sep 2011 · 441pp · 136,954 words

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

by Adam Grant · 2 Feb 2016 · 410pp · 101,260 words

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by Duff McDonald · 24 Apr 2017 · 827pp · 239,762 words

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by Benjamin R. Barber · 1 Jan 2007 · 498pp · 145,708 words

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by Philippe Legrain · 22 Apr 2014 · 497pp · 150,205 words

City: Urbanism and Its End

by Douglas W. Rae · 15 Jan 2003 · 537pp · 200,923 words

Good Profit: How Creating Value for Others Built One of the World's Most Successful Companies

by Charles de Ganahl Koch · 14 Sep 2015 · 261pp · 74,471 words

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by Jackson Lears

Black Box Thinking: Why Most People Never Learn From Their Mistakes--But Some Do

by Matthew Syed · 3 Nov 2015 · 410pp · 114,005 words

The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 1 Jan 2010 · 369pp · 94,588 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant

by W. Chan Kim and Renée A. Mauborgne · 20 Jan 2014 · 287pp · 80,180 words

The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics

by William R. Easterly · 1 Aug 2002 · 355pp · 63 words

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

by Edward E. Baptist · 24 Oct 2016

Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age

by W. Bernard Carlson · 11 May 2013 · 733pp · 184,118 words

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2020 · 505pp · 138,917 words

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by Gary Gerstle · 14 Oct 2022 · 655pp · 156,367 words

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words

The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare in the Robot Age

by Roger Bootle · 4 Sep 2019 · 374pp · 111,284 words

The Secret War Between Downloading and Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine

by Peter Lunenfeld · 31 Mar 2011 · 239pp · 56,531 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

Vertical: The City From Satellites to Bunkers

by Stephen Graham · 8 Nov 2016 · 519pp · 136,708 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

Dual Transformation: How to Reposition Today's Business While Creating the Future

by Scott D. Anthony and Mark W. Johnson · 27 Mar 2017 · 293pp · 78,439 words

The Rise of the Network Society

by Manuel Castells · 31 Aug 1996 · 843pp · 223,858 words

Cities Are Good for You: The Genius of the Metropolis

by Leo Hollis · 31 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 118,314 words

Age of Anger: A History of the Present

by Pankaj Mishra · 26 Jan 2017 · 410pp · 106,931 words

Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist's Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations

by Thomas L. Friedman · 22 Nov 2016 · 602pp · 177,874 words

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century

by Geoffrey Parker · 29 Apr 2013 · 1,773pp · 486,685 words

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by Michael Shermer · 8 Apr 2020 · 677pp · 121,255 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

Does Capitalism Have a Future?

by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, Craig Calhoun, Stephen Hoye and Audible Studios · 15 Nov 2013 · 238pp · 73,121 words

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by Douglas Rushkoff · 7 Sep 2022 · 205pp · 61,903 words

The Government of No One: The Theory and Practice of Anarchism

by Ruth Kinna · 31 Jul 2019 · 405pp · 103,723 words

The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath

by Nicco Mele · 14 Apr 2013 · 270pp · 79,992 words

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by Nate Silver · 12 Aug 2024 · 848pp · 227,015 words

Explore Everything

by Bradley Garrett · 7 Oct 2013 · 273pp · 76,786 words

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism

by Stephen Graham · 30 Oct 2009 · 717pp · 150,288 words

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker · 13 Feb 2018 · 1,034pp · 241,773 words

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by Brink Lindsey · 12 Oct 2017 · 288pp · 64,771 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by William Easterly · 4 Mar 2014 · 483pp · 134,377 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by Jonathan Taplin · 17 Apr 2017 · 222pp · 70,132 words

The Age of Em: Work, Love and Life When Robots Rule the Earth

by Robin Hanson · 31 Mar 2016 · 589pp · 147,053 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages

by Carlota Pérez · 1 Jan 2002

How Will Capitalism End?

by Wolfgang Streeck · 8 Nov 2016 · 424pp · 115,035 words

Against Intellectual Monopoly

by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine · 6 Jul 2008 · 607pp · 133,452 words

Your Computer Is on Fire

by Thomas S. Mullaney, Benjamin Peters, Mar Hicks and Kavita Philip · 9 Mar 2021 · 661pp · 156,009 words

The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes

by Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder and David Ashton · 3 Nov 2010 · 209pp · 80,086 words

The Great Disruption: Why the Climate Crisis Will Bring on the End of Shopping and the Birth of a New World

by Paul Gilding · 28 Mar 2011 · 337pp · 103,273 words

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by Carl Benedikt Frey · 17 Jun 2019 · 626pp · 167,836 words

The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas

by Janek Wasserman · 23 Sep 2019 · 470pp · 130,269 words

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by Robert J. Gordon · 12 Jan 2016 · 1,104pp · 302,176 words

The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 7 May 2024 · 470pp · 158,007 words

The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century's Greatest Dilemma

by Mustafa Suleyman · 4 Sep 2023 · 444pp · 117,770 words

Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration―and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives

by Danny Dorling and Kirsten McClure · 18 May 2020 · 459pp · 138,689 words

Free Ride

by Robert Levine · 25 Oct 2011 · 465pp · 109,653 words

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by William D. Cohan · 25 Dec 2015 · 1,009pp · 329,520 words

Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places

by Sharon Zukin · 1 Dec 2009 · 415pp · 119,277 words

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 2 Jul 2009 · 387pp · 110,820 words

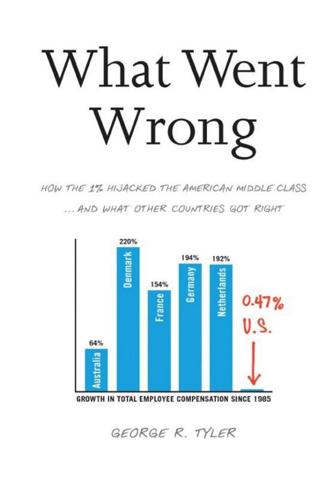

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

For the Win

by Cory Doctorow · 11 May 2010 · 624pp · 180,416 words

Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth

by Juliet B. Schor · 12 May 2010 · 309pp · 78,361 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

The Patient Will See You Now: The Future of Medicine Is in Your Hands

by Eric Topol · 6 Jan 2015 · 588pp · 131,025 words

The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter

by David Sax · 8 Nov 2016 · 360pp · 101,038 words

Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy

by Robert W. McChesney · 5 Mar 2013 · 476pp · 125,219 words

The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and the Rise of the Outsider

by Michiko Kakutani · 20 Feb 2024 · 262pp · 69,328 words

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by Astra Taylor · 4 Mar 2014 · 283pp · 85,824 words

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality

by Don Watkins and Yaron Brook · 28 Mar 2016 · 345pp · 92,849 words

The Capitalist Manifesto

by Johan Norberg · 14 Jun 2023 · 295pp · 87,204 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by Joel Mokyr · 8 Jan 2016 · 687pp · 189,243 words

How to Fix Copyright

by William Patry · 3 Jan 2012 · 336pp · 90,749 words

Rogue States

by Noam Chomsky · 9 Jul 2015

Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence

by Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb · 16 Apr 2018 · 345pp · 75,660 words

Rationality: From AI to Zombies

by Eliezer Yudkowsky · 11 Mar 2015 · 1,737pp · 491,616 words

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

The Origins of the Urban Crisis

by Sugrue, Thomas J.

The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium

by Martin Gurri · 13 Nov 2018 · 379pp · 99,340 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

by Alain Bertaud · 9 Nov 2018 · 769pp · 169,096 words

The Cultural Logic of Computation

by David Golumbia · 31 Mar 2009 · 268pp · 109,447 words

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

by David Christian · 21 May 2018 · 334pp · 100,201 words

The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power

by Jacob Helberg · 11 Oct 2021 · 521pp · 118,183 words

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life

by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky · 18 Jun 2012 · 279pp · 87,910 words

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson · 15 May 2023 · 619pp · 177,548 words

The Nature of Technology

by W. Brian Arthur · 6 Aug 2009 · 297pp · 77,362 words

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by Jaron Lanier · 21 Nov 2017 · 480pp · 123,979 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

Driverless: Intelligent Cars and the Road Ahead

by Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman · 22 Sep 2016

Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts

by Jill Abramson · 5 Feb 2019 · 788pp · 223,004 words

The Right to Earn a Living: Economic Freedom and the Law

by Timothy Sandefur · 16 Aug 2010 · 399pp · 155,913 words

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by James Rickards · 15 Nov 2016 · 354pp · 105,322 words

Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making

by David Rothkopf · 18 Mar 2008 · 535pp · 158,863 words

The Techno-Human Condition

by Braden R. Allenby and Daniel R. Sarewitz · 15 Feb 2011

The Asian Financial Crisis 1995–98: Birth of the Age of Debt

by Russell Napier · 19 Jul 2021 · 511pp · 151,359 words

Samsung Rising: The Inside Story of the South Korean Giant That Set Out to Beat Apple and Conquer Tech

by Geoffrey Cain · 15 Mar 2020 · 540pp · 119,731 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being in Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be

by Moises Naim · 5 Mar 2013 · 474pp · 120,801 words

Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 27 Nov 2012 · 651pp · 180,162 words

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by Anthony M. Townsend · 15 Jun 2020 · 362pp · 97,288 words

The Musical Human: A History of Life on Earth

by Michael Spitzer · 31 Mar 2021 · 632pp · 163,143 words

In Defense of Global Capitalism

by Johan Norberg · 1 Jan 2001 · 233pp · 75,712 words

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by Mariana Mazzucato · 1 Jan 2011 · 382pp · 92,138 words

How Did We Get Into This Mess?: Politics, Equality, Nature

by George Monbiot · 14 Apr 2016 · 334pp · 82,041 words

Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2012 · 206pp · 9,776 words

The New Geography of Jobs

by Enrico Moretti · 21 May 2012 · 403pp · 87,035 words

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by Evgeny Morozov · 15 Nov 2013 · 606pp · 157,120 words

The Great Reset: How the Post-Crash Economy Will Change the Way We Live and Work

by Richard Florida · 22 Apr 2010 · 265pp · 74,941 words

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

by Chris Hedges · 12 Jul 2009 · 373pp · 80,248 words

Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future

by Martin Ford · 4 May 2015 · 484pp · 104,873 words

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

Hawaii

by Jeff Campbell · 4 Nov 2009

The Content Trap: A Strategist's Guide to Digital Change

by Bharat Anand · 17 Oct 2016 · 554pp · 149,489 words

Brave New Work: Are You Ready to Reinvent Your Organization?

by Aaron Dignan · 1 Feb 2019 · 309pp · 81,975 words

The Day the World Stops Shopping

by J. B. MacKinnon · 14 May 2021 · 368pp · 109,432 words

The Warhol Economy

by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett · 15 Jan 2020 · 320pp · 90,115 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by Anne Case and Angus Deaton · 17 Mar 2020 · 421pp · 110,272 words

Work in the Future The Automation Revolution-Palgrave MacMillan (2019)

by Robert Skidelsky Nan Craig · 15 Mar 2020

A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

by Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore · 16 Oct 2017 · 335pp · 89,924 words

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by Chrystia Freeland · 11 Oct 2012 · 481pp · 120,693 words

The Locavore's Dilemma

by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu · 29 May 2012 · 329pp · 85,471 words

Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976-1980

by Rick Perlstein · 17 Aug 2020

Winds of Change

by Peter Hennessy · 27 Aug 2019 · 891pp · 220,950 words

The Dark Net

by Jamie Bartlett · 20 Aug 2014 · 267pp · 82,580 words

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

by Eric Topol · 1 Jan 2019 · 424pp · 114,905 words

Who Needs the Fed?: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America's Central Bank

by John Tamny · 30 Apr 2016 · 268pp · 74,724 words

Designing Social Interfaces

by Christian Crumlish and Erin Malone · 30 Sep 2009 · 518pp · 49,555 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Engineers of Dreams: Great Bridge Builders and the Spanning of America

by Henry Petroski · 2 Jan 1995

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

Epic Win for Anonymous: How 4chan's Army Conquered the Web

by Cole Stryker · 14 Jun 2011 · 226pp · 71,540 words

The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan

by Robert Kanigel · 25 Apr 2016

Dealers of Lightning

by Michael A. Hiltzik · 27 Apr 2000 · 559pp · 157,112 words

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson · 23 Sep 2019 · 809pp · 237,921 words

For Profit: A History of Corporations

by William Magnuson · 8 Nov 2022 · 356pp · 116,083 words

Nervous States: Democracy and the Decline of Reason

by William Davies · 26 Feb 2019 · 349pp · 98,868 words

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by Nouriel Roubini · 17 Oct 2022 · 328pp · 96,678 words

Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy

by Alexandrea J. Ravenelle · 12 Mar 2019 · 349pp · 98,309 words

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by Giles Slade · 14 Apr 2006 · 384pp · 89,250 words

The Pirate's Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism

by Matt Mason

How Boards Work: And How They Can Work Better in a Chaotic World

by Dambisa Moyo · 3 May 2021 · 272pp · 76,154 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by David Hale and Lyric Hughes Hale · 23 May 2011 · 397pp · 112,034 words

Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles

by Ruchir Sharma · 8 Apr 2012 · 411pp · 114,717 words

The Firm

by Duff McDonald · 1 Jun 2014 · 654pp · 120,154 words

Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself

by Peter Fleming · 14 Jun 2015 · 320pp · 86,372 words

AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

by Kai-Fu Lee · 14 Sep 2018 · 307pp · 88,180 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Born in Flames

by Bench Ansfield · 15 Aug 2025 · 366pp · 138,787 words

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by Harold James · 15 Jan 2023 · 469pp · 137,880 words

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by Rana Foroohar · 5 Nov 2019 · 380pp · 109,724 words

A New History of the Future in 100 Objects: A Fiction

by Adrian Hon · 5 Oct 2020 · 340pp · 101,675 words

The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History Since 1900

by David Edgerton · 7 Dec 2006 · 353pp · 91,211 words

Floating City: A Rogue Sociologist Lost and Found in New York's Underground Economy

by Sudhir Venkatesh · 11 Sep 2013 · 318pp · 92,257 words

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee · 20 Jan 2014 · 339pp · 88,732 words

Free culture: how big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity

by Lawrence Lessig · 15 Nov 2004 · 297pp · 103,910 words

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future

by Paul Mason · 29 Jul 2015 · 378pp · 110,518 words

How to Fix the Future: Staying Human in the Digital Age

by Andrew Keen · 1 Mar 2018 · 308pp · 85,880 words

The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking

by Saifedean Ammous · 23 Mar 2018 · 571pp · 106,255 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall · 19 Mar 2019 · 393pp · 115,217 words

Trust: The Social Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 1995 · 585pp · 165,304 words

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by Robert Higgs and Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. · 15 Jan 1987

The Participation Revolution: How to Ride the Waves of Change in a Terrifyingly Turbulent World

by Neil Gibb · 15 Feb 2018 · 217pp · 63,287 words

Debunking Economics - Revised, Expanded and Integrated Edition: The Naked Emperor Dethroned?

by Steve Keen · 21 Sep 2011 · 823pp · 220,581 words

New York 2140

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 14 Mar 2017 · 693pp · 204,042 words

Fool's Gold: How the Bold Dream of a Small Tribe at J.P. Morgan Was Corrupted by Wall Street Greed and Unleashed a Catastrophe

by Gillian Tett · 11 May 2009 · 311pp · 99,699 words

The Big Score

by Michael S. Malone · 20 Jul 2021

Uncharted: How to Map the Future

by Margaret Heffernan · 20 Feb 2020 · 335pp · 97,468 words

Wasps: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy

by Michael Knox Beran · 2 Aug 2021 · 800pp · 240,175 words

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by William Davidow and Michael Malone · 18 Feb 2020 · 304pp · 80,143 words

99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It

by Mark Thomas · 7 Aug 2019 · 286pp · 79,305 words

The Crux

by Richard Rumelt · 27 Apr 2022 · 363pp · 109,834 words

When McKinsey Comes to Town: The Hidden Influence of the World's Most Powerful Consulting Firm

by Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe · 3 Oct 2022 · 689pp · 134,457 words

Car Guys vs. Bean Counters: The Battle for the Soul of American Business

by Bob Lutz · 31 May 2011 · 249pp · 73,731 words

How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism