One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

by

Michael Dobbs

Published 3 Sep 2008

The most sensible approach for the researcher is to find multiple sources, and use documentary evidence to corroborate oral history, and vice versa. The starting point for my archival research was the extensive Cuban missile crisis documentation assembled by the National Security Archive, an indispensable reference source for contemporary historians. The Archive, under the direction of Tom Blanton, has taken the lead in aggressively using the Freedom of Information Act to pry historical documents out of a frequently recalcitrant U.S. bureaucracy. In the case of the Cuban missile crisis, it fought a landmark court battle in 1988 to obtain access to a collection compiled by the State Department historian.

…

Sergei Karlov, official historian, Peter the Great Military Academy of Strategic Rocket Forces (RSVN), May 2006. 28 Military statisticians later estimated: Ibid. 28 "barreled gas oil": NSA Cuban missile crisis release, October 1998. 28 McNamara estimated Soviet troop: JFK2, 606. The CIA had estimated 3,000 Soviet "technicians" in Cuba on September 4. By November 19, they increased the estimate to 12,000–16,000. In January 1963, they concluded retrospectively that there were 22,000 Soviet troops in Cuba at the peak of the crisis. See Raymond L. Garthoff, Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1989), 35. 28 "For the sake of the revolution": Author's interview with Capt.

…

: WP, October 23, 1962, A1; Beschloss, 482. 42 "This is not a war": Fursenko and Naftali, Khrushchev's Cold War, 474. 42 "We've saved Cuba": Oleg Troyanovsky, Cherez Gody y Rastoyaniya (Moscow: Vagrius, 1997), 244–5. 42 The 11,000-ton Yuri Gagarin: I have reconstructed the positions of Soviet ships on October 23 from CIA daily memorandums for October 24 and 25, NSA intercepts, plus research in Moscow by Karlov. See also Statsenko report. 43 Her cargo included:Yesin et al., Strategicheskaya Operatsiya Anadyr', 114. 43 After a sixteen-day voyage: For the positions of the Aleksandrovsk and Almetyevsk, see NSA Cuban missile crisis release, vol. 2, October 1998. 43 In addition to the surface ships: Svetlana Savranskaya, "New Sources on the Role of Soviet Submarines in the Cuban Missile Crisis," Journal of Strategic Studies (April 2005). 44 The vessels closest to Cuba:The ships that continued to Cuba were the Aleksandrovsk, Almetyevsk, Divnogorsk, Dubno, and Nikolaevsk, according to CIA logs and Karlov research. 44 "In connection with": Havana 2002, vol. 2, Document 16, author's trans. 44 "Order the return": Fursenko, Prezidium Ts.

Winds of Change

by

Peter Hennessy

Published 27 Aug 2019

Sherry Sontag and Christopher Drew with Annette Lawrence Drew, Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of Cold War Submarine Espionage (Arrow, 1998), p. 45. 194. Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, p. 85. 195. May and Zelikow (eds.), The Kennedy Tapes, p. 519. 196. Ted Sorensen, Kennedy (Hodder, 1965), p. 789. 197. May and Zelikow (eds.), The Kennedy Tapes, p. 571. 198. Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, pp. 91–2. 199. Ibid., p. 101. 200. Fursenko and Naftali, Khrushchev’s Cold War, pp. 478–80. 201. Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, p. 104. 202. Quoted in Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, p. 105. 203.

…

TNA, PRO, CAB 158/47, JIC (62) 70 (Final) (E), ‘Escalation’, 14 November 1962. 185. Scott, Macmillan, Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis, p. 159. 186. Catterall (ed.), The Macmillan Diaries, vol. 2, p. 513, diary entry for 28 October 1962; Macmillan diaries (unpublished), diary entry for 26 October 1962. 187. Tuchman, The Guns of August, p. 74. 188. Kennedy letter to Khrushchev, 29 October 1962, reproduced in May and Zelikow (eds.), The Kennedy Tapes, pp. 636–7. 189. Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, p. 71. 190. Ibid., pp. 71, 80, 100, 120, 147–8. 191. Scott, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Threat of Nuclear War, p. 134. 192. Ibid., pp. 1–2. 193.

…

TNA, PRO, CAB 158/47, JIC (62) 104. 319. Extract from David Bruce’s diary for 23 and 24 October 1962, reproduced in Scott, Macmillan, Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis, pp. 87–8. 320. May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes, p. 333. 321. Scott, Macmillan, Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis, p. 88. 322. Richard Taylor, Against the Bomb: The British Peace Movement, 1958–65 (Oxford University Press, 1988); Grant, After the Bomb, pp. 173–4, 175–6, 185–6, 187, 191. 323. Scott, Macmillan, Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis, p. 88. 324. Driver, The Disarmers, p. 146. 325. Ibid., p. 120. 326. Ibid., p. 143. 327. May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes, p. 369. 328.

Risk: A User's Guide

by

Stanley McChrystal

and

Anna Butrico

Published 4 Oct 2021

intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) sites: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 76. discuss and debate options: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 109–137. settles on the “blockade-ultimatum”: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 136–138. formally convenes ExComm: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 151. informs Congress of his decision: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 163–183. addresses the American people: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 183–189.

…

addresses the American people: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 183–189. letter to Chairman Khrushchev: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 189–190. expressing grievance and frustration: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 242–243. continue to ready their missile sites: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 269. Soviet ships headed to Cuba: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 297–99. seemingly contradictory letter: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 311–14.

…

seemingly contradictory letter: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 311–14. American U-2 plane: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 356–61. remove and dismantle their missiles: May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 402–404, 436–37. Executive Committee of the National Security Council: Kennedy, Thirteen Days, Section 1; May and Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, 151. “the new chairman of the joint chiefs”: Josh Zeitz, “When Daily Intelligence Briefings Prevented a Nuclear War,” Politico Magazine, December 12, 2016, https://politico.com/magazine/story/2016/12/trump-daily-intelligence-briefings-history-jfk-cuban-missile-crisis-214521.

Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam

by

H. R. McMaster

Published 7 May 1998

He surrounded himself with people who “knew a hell of a lot more” than he did about national security issues and learned from them. He was a good student, however, and “by the time of the Cuban missile crisis [his] views were pretty well fixed and [hadn’t] changed to this day.”29 McNamara was proud of what he portrayed as a personal triumph during the Cuban missile crisis. When he turned his attention to Southeast Asia, he exuded confidence that he had gained in the Caribbean. The defense secretary was determined to remove obstacles that might prevent him from assuming the role of chief strategist in the Pentagon. During the Cuban missile crisis, McNamara kept tight control over the ships, submarines, and aircraft enforcing the quarantine around Cuba to ensure that the demonstration of American resolve sent the proper message to the Soviets.

…

He would become Lyndon Johnson’s “oracle” for Vietnam. 4 Graduated Pressure January–March 1964 We had seen the gradual application of force applied in the Cuban Missile Crisis and had seen a very successful result. We believed that, if this same gradual and restrained application of force were applied in South Vietnam, that one could expect the same result. –CYRUS VANCE, 19701 Robert S. McNamara and his principal assistants in the Department of Defense, convinced that traditional military conceptions of the use of force were irrelevant to contemporary strategic and political realities, developed courses of action for Vietnam that reflected their experience during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis (which molded their thinking on strategy) and their predisposition toward quantitative analysis.

…

In keeping with McNamara’s views, Taylor told the Chiefs on March 2 that the White House intended to use South Vietnam as a “laboratory, not only for this war, but for any insurgency.”49 McNamara became the principal architect of the new strategy of graduated pressure, which he would test in Vietnam.50 While in his estimation military experience was irrelevant to the new kind of war, McNamara drew heavily upon his personal experience during the Cuban missile crisis. The rejection of JCS advice in October 1962 had led to the withdrawal of the offensive weapons without war. He acknowledged that the missile crisis “was very influential in [his] decisions relating to Vietnam.”51 Indeed, U.S. Military Action Against North Viet Nam—An Analysis, Annex A to the report that McNamara drafted for the president in early March 1964, contained several direct references to the Cuban missile crisis.52 Although McNamara believed that JCS advice was inapplicable, he thought that the use of American military force was integral to the foreign policy of the Cold War period.

Red November: Inside the Secret U.S.-Soviet Submarine War

by

W. Craig Reed

Published 3 May 2010

RESOURCES Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency, James Bamford, Anchor, April 30, 2002, offered information regarding John Arnold and Cuban SIGINT missions conducted by the USS Nautilus and Oxford, as well as details about the USS Pueblo. Jeffrey G. Barlow, “Some Aspects of the U.S. Navy’s Participation in the Cuban Missile Crisis,” in A New Look at the Cuban Missile Crisis, Colloquium on Contemporary History, June 18, 1992, No. 7, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy Command in Crisis: Four Case Studies, Joseph F. Bouchard, Columbia University Press, 1991 The Cuban Missile Crisis, ed. Laurence Chang, National Security Archive, 1992 “The Naval Quarantine of Cuba, 1962,” Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1963, http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq90-5.html October Fury, Peter Huchthausen, John Wiley & Sons, 2002 Presidential Recordings: John F.

…

Orlov, Captain Second Rank, Russian Navy (retired; unpublished memoir) CINCLANT SOSUS contact reports during the Cuban Missile Crisis “Khrushchev, Castro and Kennedy: Motivation, Intention, and the Creation of a Crisis,” Robin R. Pickering, thesis presented to the faculty of Humboldt State University, May 2006 Deck logs obtained for various naval platforms during the Cuban Missile Crisis Eyeball to Eyeball, The Inside Story of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Dino A. Brugioni, Random House, 1991 Soviet Naval Developments, third edition, foreword by Norman Polmar, The Nautical and Aviation Publishing Co. of America, 1984 Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Robert F. Kennedy, W. W. Norton & Co., 1969 Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies, 1718–1990, Norman Polmar and Jurrien Noot, Naval Institute Press, 1991 Combat Fleets of the World 1980/81, Jean Labayle Couhat, Naval Institute Press, 1980 U.S.

…

Courtesy of Ryurik Ketov But they also forced three of the Foxtrot submarines, including Captain Savitsky’s B-59 (above) to the surface during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The United States did not know at the time that each Foxtrot carried a nuclear-tipped torpedo capable of destroying everything within a ten-mile radius, and all four Soviet subs came within minutes of firing. U.S. Navy photograph The U.S. Navy was primarily focused on blocking Soviet merchant ships from bringing more nuclear missiles to Cuba. U.S. Government photograph Living conditions aboard the Soviet Foxtrot-class submarines involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis were deplorable, and crews suffered from heat exhaustion.

Cuba: An American History

by

Ada Ferrer

Published 6 Sep 2021

Photograph in Harpers, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/01/the-real-cuban-missile-crisis/309190/; Alexa Kapsimalis interview, Storycorps, https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/grandpa-cuban-missile-crisis/. 15. Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, 380; Dobbs, One Minute, 84–85. 16. Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, 380; Fidel Castro speech, October 23, 1962; Adolfo Gilly, “A la luz del relámpago: Cuba en Octubre,” Viento Sur 102 (March 2009), 82. 17. Fursenko and Naftali, One Hell, 265–67; Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 42 and p. 387. 18. James Blight and janet M.

…

Kennedy Library, https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct26/doc2.html: See also NSA, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 46, and p. 387; Wilson Digital Archive, https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114501; Diez Acosta, Octubre, 177–78; Blight and Lang, Dark, 39–40. 21. Khrushchev to Kennedy, October 26, 1962 and October 27, 1962 (Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, docs. 45 and 49); Fursenko and Naftali, One Hell, 273–74. 22. Transcript of ExComm meetings, October 27, 1962, DNSA, Cuban Missile Crisis Collection; Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 50. 23. Fursenko and Naftali, One Hell, 282. 24. Transcript of ExComm meetings, October 27, 1962, Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 50; Dobbs, One Minute, 309, 312–13; Jack Raymond, “Airmen Called Up,” New York Times, October 28, 1962. 25.

…

Permanent Representative of Cuba to the UN Secretary General, October 28, 1962, in Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 57. 30. Khrushchev to Castro, October 28, 1962, and Castro to Khrushchev, October 28, 1962, Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, docs. 55 and 56. 31. Kennedy to Khrushchev, October 27, 1962, in https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct27/; Khrushchev to JFK, October 27, 1962, https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct27/doc4.html. 32. Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, 402–3; Naftali and Fursenko, One Hell, 304–9. 33. Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, 405. 34. Kennedy, transcript of November 20, 1962 press conference, https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-press-conferences/news-conference-45; Kennedy to Khrushchev, November 21, 1962, in Chang and Kornbluh, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, doc. 79. 35.

Spies, Lies, and Algorithms: The History and Future of American Intelligence

by

Amy B. Zegart

Published 6 Nov 2021

Fursenko and Naftali, “Soviet intelligence and the Cuban missile crisis,” Intelligence and National Security 13, no. 3 (2008): 64–87. 80. Fursenko and Naftali; Renshon, “Mirroring risk”; James G. Blight and David A. Welch, eds., Intelligence and the Cuban Missile Crisis (London: Frank Cass, 1999); Allison and Zelikow, Essence of Decision. 81. Raymond L. Garthoff, “U.S. intelligence in the Cuban missile crisis,” Intelligence and National Security 13, no. 3 (1998): 47. 82. Quoted in Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 705. 83. Arthur Schlesinger, remarks at “On the Brink: The Cuban Missile Crisis,” John F.

…

Kessel, and Melissa Chan, “Made in China, Exported to the World: The Surveillance State,” New York Times, April 24, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/technology/ecuador-surveillance-cameras-police-government.html (accessed September 24, 2020). 23. Zegart and Morell, “Spies, lies, and algorithms.” 24. Amy Zegart, “The Cuban missile crisis as intelligence failure,” Policy Review, Hoover Institution, October 2, 2012, https://www.hoover.org/research/cuban-missile-crisis-intelligence-failure (accessed September 20, 2020). 25. Jeff Jardins, “How much data is generated each day?” World Economic Forum, April 17, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/how-much-data-is-generated-each-day-cf4bddf29f/ (accessed September 24, 2020). 26.

…

Walter Pincus, “Spy Agencies Faulted for Missing Indian Tests,” Washington Post, June 3, 1998. 74. Central Intelligence Agency, “Jeremiah News Conference.” 75. Ovodenko, “(Mis)interpreting threats,” 277. 76. Amy Zegart, “The Cuban missile crisis as intelligence failure,” Policy Review, Hoover Institution, October 2, 2012, https://www.hoover.org/research/cuban-missile-crisis-intelligence-failure (accessed September 20, 2020); U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “SNIE 80-62: The Threat to U.S. Security Interests in the Caribbean Area,” January 17, 1962, in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963 [FRUS], Vol. 12: American Republics, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v12/d91 (accessed September 2, 2020); U.S.

The Cold War

by

Robert Cowley

Published 5 May 1992

Few people there, he once told me, were aware of the Cuban Missile Crisis; the Soviet media had blacked out all mention of it. “But they knew something big was up,” he added, “even if we didn't know precisely what until Khrushchev made a talk at the end, hiding lots of things and twisting others into a Soviet victory. I knew much more than most people, because while the crisis was on, I happened to bump into a friend from the American embassy staff on a busy street. He told me. Still, I knew too little to be scared that I might be killed by an American nuclear bomb at any moment.” The precarious two weeks of the Cuban Missile Crisis came close to overshadowing the emergency in Europe of a year earlier, the erection of the Berlin Wall.

…

LeMay was eventually made chief of staff of the air force, the position he held during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Privately, he believed that JFK behaved like a coward, that we should have exercised a first-strike option. The Sunday morning after the two Ks cemented their deal, the president summoned his military chiefs to the Cabinet Room to inform them. LeMay pounded the table, his cigar no doubt clenched in his teeth. “It's the greatest defeat in our history, Mr. President…. We should invade today!” For the rest of his life, he remained convinced that we had “lost” the Cuban Missile Crisis—and, indeed, the entire Cold War. VICTOR DAVIS HANSON retired last year as a professor of classics at California State University, Fresno, and is now a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

…

A large crash shattered the window and threw the pieces into the four corners of the room. Sirens screeched. I had difficulty trying to breathe in the fog that now filled the room. We got to our feet and made our way through the crowded halls to the air raid shelter.” Life, for the narrator, would never be the same. A year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, apocalypse was still on our minds. We were not quite halfway through the Cold War, and the Bomb—Bombs, rather—seemed to be our undeserved future. As I read my wife's story, written in her properly neat schoolgirl script, the memory of the nuclear clock resurfaced, its hands perpetually stuck at one minute to midnight.

Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth

by

Frederick Kempe

Published 30 Apr 2011

In the words of William Kaufman, a Kennedy administration strategist who worked both Berlin and Cuba from the Pentagon, “Berlin was the worst moment of the Cold War. Although I was deeply involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis, I personally thought that the Berlin confrontation, especially after the wall went up, where you had Soviet and U.S. tanks literally facing one another with guns pointed, was a more dangerous situation. We had very clear indications mid-week of the Cuban Missile Crisis that the Russians were not really going to push us to the edge…. “You didn’t get that sense in Berlin.” Fred Kempe’s contribution to our crucial understanding of that time is that he combines the “You are there” storytelling skills of a journalist, the analytical skills of the political scientist, and the historian’s use of declassified U.S., Soviet, and German documents to provide unique insight into the forces and individuals behind the construction of the Berlin Wall—the iconic barrier that came to symbolize the Cold War’s divisions.

…

Most surprised of all by Kennedy’s demonstration of strength was Khrushchev himself, who had bet so much against it. General Clay suggested to diplomat William Smyser that the Cuban Missile Crisis never would have occurred had it not been for Khrushchev’s perception of Kennedy’s weakness, and Clay believed as well that the threat to Berlin only receded once Kennedy made it clear he would no longer tolerate Moscow’s bullying. West Berliners celebrated the outcome of the Cuban Missile Crisis more enthusiastically than any others. They concluded that the Soviet threat to them had passed. RATHAUS SCHÖNEBERG, CITY HALL OF WEST BERLIN WEDNESDAY, JUNE 26, 1963 Kennedy would make his first and last presidential trip to Berlin eight months after the Cuban crisis, on June 26, 1963.

…

At the same time…Soviet ships: Beschloss, Crisis Years, 412–415; Taubman, Khrushchev, 549–551; Fursenko and Naftali, Khrushchev’s Cold War, 451; Raymond L. Garthoff, Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1987, 18–22, 208 (table showing type and numbers of missiles). Fechter’s murder snapped something: “City’s Mood: Anger and Frustration,” New York Times, 08/26/1962. Meanwhile, over Cuba: Anatoli I. Gribkov and William Y. Smith, “Operation Anadyr”: U.S. and Soviet Generals Recount the Cuban Missile Crisis. Chicago: Edition Q, 1994, 5–7, 24, 26–57; Taubman, Khrushchev, 550; Fursenko and Naftali, One Hell of a Gamble, 188–189, 191–193.

Who Rules the World?

by

Noam Chomsky

Domínguez, “The @#$%& Missile Crisis (Or, What Was ‘Cuban’ About U.S. Decisions During the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Diplomatic History 24, no. 5 (Spring 2000): 305–15. 20. Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, concise edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002), 47. 21. Jon Mitchell, “Okinawa’s First Nuclear Missile Men Break Silence,” Japan Times, 8 July 2012. 22. Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight, 309. 23. Sheldon M. Stern, Averting “The Final Failure”: John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), 273. 24.

…

Stern, Averting “The Final Failure.” 30. Ibid., 406. 31. Raymond L. Garthoff, “Documenting the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Diplomatic History 24, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 297–303. 32. Papers of John F. Kennedy, Presidential Papers, National Security Files, Meetings and Memoranda, National Security Action Memoranda [NSAM]: NSAM 181, Re: Action to be taken in response to new Bloc activity in Cuba (B), September 1962, JFKNSF-338-009, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, Massachusetts. 33. Garthoff, “Documenting the Cuban Missile Crisis.” 34. Keith Bolender, Voices From the Other Side: An Oral History of Terrorism Against Cuba (London: Pluto Press, 2010). 35.

…

Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival, 78–83. 41. Stern, The Week the World Stood Still, 2. 42. Desmond Ball, Politics and Force Levels: The Strategic Missile Program of the Kennedy Administration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 97. 43. Garthoff, “Documenting the Cuban Missile Crisis.” 44. Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight, 342. 45. Allison, “The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50.” 46. Sean M. Lynn-Jones, Steven E. Miller, and Stephen Van Evera, Nuclear Diplomacy and Crisis Management: An International Security Reader (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press 1990), 304. 47. William Burr, ed., “The October War and U.S. Policy,” National Security Archive, published 7 October 2003, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB98/. 48.

The Cold War: A New History

by

John Lewis Gaddis

Published 1 Jan 2005

Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers, translated and edited by Strobe Talbott (New York: Bantam, 1971), p. 546. 59 Taubman, Khrushchev, p. 537. 60 See the transcripts of conversations between American and Soviet veterans of the crisis in Blight, Allyn, and Welch, Cuba on the Brink; and in James G. Blight and David A. Welch, On the Brink: Americans and Soviets Reexamine the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989). 61 Kennedy meeting with advisers, October 22, 1962, in Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 235. 62 Taubman, Khrushchev, p. 552. 63 Blight, Allyn, and Welch, Cuba on the Brink, p. 259. 64 Ibid., p. 203. 65 Gaddis, We Now Know, p. 262; “NRDC Nuclear Notebook: Global Nuclear Stockpiles, 1945–2002,” p. 104. 66 Blight, Allyn, and Welch, Cuba on the Brink, p. 360. 67 Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (New York: St.

…

Great Society programs of Vietnam War and Johnson administration Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. Justice Department, U.S. Kádár, János Kant, Immanuel Katyn Wood massacre Kazakhstan Kennan, George F. “long telegram” of on role of C.I.A. on U.N. Kennedy, John F. Cuban missile crisis and U.S.-Soviet relations and Kennedy, Robert F. Kent State incident K.G.B. Khmer Rouge Khomeini, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khrushchev, Nikita background and personality of Berlin Wall and Cuban missile crisis and East German alliance and Eisenhower’s meetings with Hungarian uprising and nuclear weapons policy of ouster of rise of Sino-Soviet relations and Stalin denounced by Suez crisis and Tito visited by U.S. visited by U-2 incident and “We will bury you” remark of Khrushchev, Sergei Kim Il-sung King, Martin Luther, Jr.

…

But my students sign up for this course with very little sense of how the Cold War started, what it was about, or why it ended in the way that it did. For them it’s history: not all that different from the Peloponnesian War. And yet, as they learn more about the great rivalry that dominated the last half of the last century, most of my students are fascinated, many are appalled, and a few—usually after the lecture on the Cuban missile crisis—leave class trembling. “Yikes!” they exclaim (I sanitize somewhat). “We had no idea that we came that close!” And then they invariably add: “Awesome!” For this first post–Cold War generation, then, the Cold War is at once distant and dangerous. What could anyone ever have had to fear, they wonder, from a state that turned out to be as weak, as bumbling, and as temporary as the Soviet Union?

This Is Only a Test: How Washington D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War

by

David F. Krugler

Published 2 Jan 2006

Fursenko, One Hell, 188–9 (the quote is on 189); “Chronologies of the Crisis,” compiled for Laurence Chang and Peter Kornbluh, eds., The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962: A National Security Archive Documents Reader (New York: The New Press, 1992), accessed June 23, 2005 at the National Security Archive http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/chron.htm.. 22. “Chronologies of the Crisis”; Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997), 45–76, 189–203. Furensko, One Hell, 242–3; “Chronologies of the Crisis”; “Radio and Television Report to the American People,” October 22, 1962, PPP: John F.

…

Phillip, 11–12 Rapalus, Henry, 115, 140–1 Raven Rock Mountain, 63–4, 66–7, 87, 108, 167 see also Site R Rayburn, Sam, 50, 56, 167 Reston, Va., 6, 147, 185 Reynolds, W.E., 60, 121 Rockville, Md., 115, 139–41, 173 Rodericks, George, 172, 175, 178, 184 Roosevelt, Eleanor, 13–14 Roosevelt, Franklin civil defense and, 13–14 death of, 16 Pentagon and, 17–18, 67 White House and, 15, 70–1 Schwartz, Max, 52, 54, 87 shelters see fallout shelters Sherry, Michael, 90 Silvers, Hal, 131, 133–4 Site R, 64–5, 67–8, 95, 126–7, 132, 158, 162, 165–6, 180, 183, 185–6 see also Raven Rock Mountain Smith, Howard, 62–3 Social Science Research Council, 22, 89 Soviet Union aircraft of, 1, 5, 10, 82, 87, 90, 111, 113, 116, 132 Cold War and, 18–20, 48, 59 Cuban Missile Crisis and, 174–9 deterrence of, 91–2, 98 espionage of, 6, 18, 104 nuclear weapons of, 1, 10, 131–2, 136, 142, 169, 182, 235 n.44 propaganda of, 25, 85, 87 striking capability of, 10, 108, 116, 120–1, 158–60, 166 test of atomic bomb, 32, 35–6, 41, 64, 171 test of hydrogen bomb, 75, 99–100 War Scare of 1948 and, 23–5 see also Washington, D.C., imagined attacks on Spencer, Samuel, 121, 132 Springfield, Va., 34 Stalin, Joseph, 6, 18 State Department Cuban Missile Crisis and, 177, 180–1 offices in Washington, D.C., 17, 21, 50, 61, 101, 144 participation in exercises, 109, 121, 127–8, 161 relocation site of, 93–6, 109, 121, 128, 155, 165–6, 180, 183 Steelman, John, 32 Stein, Clarence, 28, 60, 147 Stewart Air Force Base, 112, 150 Stowe, David, 49–50, 75, 96 Strategic Air Command (SAC), 111, 114, 179 Strauss, Lewis, 102, 133 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) see ballistic missiles Suitland, Md., 34 Supreme Court continuity of, 7, 168, 177–8 during Cuban Missile Crisis, 177–8, 181 participation in exercises, 129 rulings on racial segregation, 145–6 Symington, Stuart, 55–7, 59, 91, 171 Takoma Park, Md., 48, 122 Teague, Olin, 122–3 ‘tempos’ on National Mall, 17, 21, 26, 31, 38–9, 43, 50–1, 61–2, 103–4 proposed construction of, 34–6 Treasury Department continuity of, 106, 180 participation in exercises, 81, 109, 117, 127–8, 161 relocation sites of, 183 tunnel to White House, 69, 73 Truman, Harry S. authorization of Conelrad, 112 authorization of development of hydrogen bomb, 6 continuity of government planning of, 5, 64, 75, 96, 105 Doctrine of, 23, 171 end of World War II and, 16–18 Korean War and, 48–9, 59 reaction to Soviet atomic test, 35, 171 reelection of, 31 support for civil defense, 23–4, 46, 55–6, 81, 86, 90–2, 170 support for desegregation of Washington, D.C., 3, 145 support for dispersal, 4, 49–52, 59, 61–3, 104 treatment of NSRB, 25, 31–2 use of the Bureau of the Budget, 37 White House renovation and, 69–71, 73–4 Tuve, Dr.

…

Merle, 135 Tysons Corner, Va., 66, 185 UFOs, 85–6 Underhill, John Garrett, 123, 130 United States air defense systems described, 91, 111–14 nuclear weapons of, 9–10, 170, 179 part in Cold War’s origins, 18–19 United States Information Agency (USIA), 95, 134, 177, 183 United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 21–2, 27, 36, 61, 119 Valley Forge Foundation, 79 Vanderbilt, Tom, 185, 237 n.21 Virginia, 2, 5, 15, 34, 43, 62, 101–2, 146, 187 see also individual cities and counties Wadsworth, James, 33–4 Warning Red defined, 77, 173 test activation of, 47, 113, 116, 121–2 see also attack warning Warning Yellow accidental declaration of, 114, 154 declaration of, 96, 112–13, 124, 132, 136, 141 defined, 77, 173 difficulty of keeping secret, 114–15, 124, 134 test activation of, 126–7, 149–50, 156, 160 see also attack warning Warren, Earl, 168–9, 177–8 Warrenton, Va., 95–6, 183 War Scare of 1948, 24–6 wartime essential agencies defined, 4–5, 196 n.16 dispersal of, 30, 38, 40–1, 101–2, 147 participation in exercises, 108–9, 121, 124–9, 156–63, 160, 182 responsibilities of, 105–6, 164, 186 vulnerability of, 105 wartime essential personnel advance evacuation of, 113–14, 120, 124, 155, 163, 177–8, 181 cadres of at Mount Weather, 7, 106, 159, 163, 165, 176 during Cuban Missile Crisis, 176, 178–9 expected actions during crisis, 115, 129, 134, 162–3, 181–2 Washington Area Survival Plan committee (WASP), 132, 135, 138, 141 Washington and Lee University, 15, 95, 157, 165 Washington Board of Trade, 46, 81 Washington, D.C. on 9/11, 185–7 Alert America in, 77–80 attack warning system of, 14, 111–15, 150–5 civil defense in see under D.C. Office of Civil Defense civil defense during World War II, 14–16 during Cuban Missile Crisis, 175–6 difficulty of evacuating, 109, 115, 121–4, 132–5 effects of World War II on, 11–12, 14, 16–17 exercises staged in, 116–17, 119–21, 124–30 government of, 3, 45–6 ground observer posts in, 82–5, 138–9 imagined attacks on, 1–2, 23, 36, 47, 67, 111–14, 117, 136, 158–60, 179–81 see also Operation Alert lack of home rule, 3, 93 national security state in, 21 planning for civil defense office in, 45–7 population of, 12, 26, 122, 145 present–day emergency plans of, 187–9 segregation of, 2–3, 14–15, 54, 84, 145–7 slavery in, 3 symbolic importance of, 3–4, 8, 49, 122–3, 135 UFO scare in, 85–6 see also dispersal, plans for metropolitan Washington, D.C.

Atomic Obsession: Nuclear Alarmism From Hiroshima to Al-Qaeda

by

John Mueller

Published 1 Nov 2009

See escalation fear fear mongering, brotherhood or peace, 26–27 Ferguson, C., Russian or Pakistan bomb, 20–21, 166–167 fictional accounts, future war, 244–245n.19 financial costs, bombs, 178 Finel, Bernard, hijackers of 9/11, 192 Fingar, Tom, al-Qaeda and fissile material, 207–208 “firestorms,” fire, 5 Fischoff, Baruch, radiation and panic, 195–196 fissile material al-Qaeda and, 207–208 inventory and securing, 194 Israel bombing reactor of, 262n.12 Mahmood, 271n.16 procuring, 169–172 yield, 168 flash of heat and light, nuclear explosion, 5 “football war,” Honduras and El Salvador, 255n.33 foreign policy, proliferation fixation, 137–141 forensics, nuclear, 155, 164, 190, 194, 264n.6 Fox Television’s 24, suitcase bombs, 167 France Algeria, 109 arsenals as insurance against Iran, 87 President de Gaulle and first bomb, 105–106 France and Germany, general stability, 67 Franks, General Tommy, freedom and liberty, 21 Freud, S., Civilization and Its Discontents, 24 Frost, Robin, fissile materials, 170–171 Fursenko, Aleksandr, 76, 249n.12, 263n.29 future war, fictional accounts, 244–245n.19 Gadahn, Adam, propaganda video, 219 Gaddis, John, 31, 69–70 Garwin, Richard, 111, 181, 188 gas attacks, war between Iran and Iraq, 245n.26 gas fatalities, war, 244n.16 Gates, Defense Secretary Robert Iraqis and sanctions, 134 nuclear weapon worry, 163 worries, xi Gavin, Francis, 95–96, 148 Gerges, Fawaz The Far Enemy, 221 jihadis, 199, 275n.28 Middle East outrage over 9/11, 225 Germany, 106–107, 244n.16 Germany and France, general stability, 67 Gilmore Commission, 12, 186, 231 Gilpatric Report of 1965, 91, 99 Gilpin, Robert, international prestige, 105 Goldstein, Joshua, society and economy, 20 Gorbachev, Mikhail end of cold war, 50–51 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement, 80 reexamining basic ideology, 250n.21 Goss, Porter, chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear materials, 272n.24 governments, Pakistan and United States, 164 Graham Commission (2008), 260n.28 Great War, 23–24, 55–56 Grenier, Robert, al-Qaeda as own worst enemy, 227 GRIT: Graduated Reciprocation in Tension-reduction, 254n.30 Group of Five, rich nations club, 107 group solidarity, terrorists, 276n.47 Guiliani, Rudy, security experts, 161 Gulf War of 1991, 109, 132, 133–134 The Guns of August, Tuchman, 40 Haig, Secretary of State A., 32, 59–60 Halevi, Yossi Klein, 262n.20, 263n.27, 264n.24 Hamas, 262n.20 Hasegawa, T., Soviet neutrality, 46 health facilities, nuclear attack, 8 heat and light, nuclear explosion, 5 Hebrew University, “A Nuclear Iran,” 263n.31 Hezbollah, 262n.20 highly enriched uranium (HEU) acquisition scenario, 190, 265n.20 adequate supply for terrorists, 188 atomic terrorist’s task, 185, 186 fissile material, 169–172 googling, on internet, 268–269n.16 safety, 175 South African break-in, 171 hijackers, terrorism probability, 192–193 Hiroshima “atomic age,” ix atomic bomb, 9–10 bomb size, 266n.30 damage, 3 historical impact of weapons, 29 human costs, 141, 248–249n.1 military value of atomic bomb, 10 product testing, 175 Stalin’s program to get atom bomb, 47, 49–50 surrender of Japanese, 43 taboo of nuclear weapons, 61–63 Holland, nuclear opponents, 251n.13 Holloway, David, bomb as diplomacy, 32, 46–47, 59 Holocaust, second, 262n.20 horizontal proliferation, nuclear weapons, 73 “hormesis” hypothesis, 242n.12 human costs Hiroshima, 141, 248–249n.1 Nagasaki, 141 Human Rights Watch, Iraqi attacks, 245n.26 Hurricane Katrina, death toll, 22, 244n.13 Hussein, Saddam Bush’s war against, 98 chemical weapons, 227 Gulf War of 1991, 109, 132 human costs, 141–142 human costs for obtaining nuclear weapons, 142 Iraq War, 132–134 weapons of mass destruction, 259n.5 hydrogen bomb, plutonium trigger, 250n.17 Hymans, Jacques, 94, 146, 148, 263n25 bi-national bomb program, 257n.13 fighting smoke with fire, 158 hysteria and North Korea, 263n.25 international prestige, 107 nuclear proliferation pace, 119–120 nuclear weapons programs, 111, 113 “oppositional nationalist,” 261n.2 state’s decision to go nuclear, 110 threats and going nuclear, 144 Washington threat consensus, 132, 254n.14, 257n.1 hyperbole, 18, 231 hysteria Langewiesche’s book, 183, 268n.5 North Korea, 263n.25 ideology, Soviet, 33–35 ideology disagreements, cold war, 51, 53 Ignatieff, Michael, 20, 21, 244n.10 improvised nuclear device (IND) acquisition scenario, 190 atomic terrorist’s task, 185 devotion and technical skills, 176 difficulties, 175 predicting bombing, 195 simplest design, 168 transportation, 177–178 India economics of nuclear weapons, 111 nuclear tests and bin Laden, 212 nuclear weapons capability, 90, 91 prestige or influence, 108 indirect effects, nuclear attack, 8 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF), 80 International Atomic Energy Agency, x, 93 international attention, nuclear weapons, 108 international pressure, nuclear programs, 113–114 international relations, alliance and structure, 52–53 international terrorism, threat, 274–275n.20 invasion, potential Soviet, of Europe, 35–38 inventory, fissile material, 194 Iran atomic arsenal, 238 axis of evil, 144–145 calm policy discussion, 151, 153–155 deterrence, 156 France insuring against, 87 hostility to Israel, 154 Israeli anxieties about security, 150–151 nuclear weapon, x proliferation, 93 sanctions, 145–146 Iranian nuclear threat, 262n.20, 263n.27 Iraq al-Qaeda as own worst enemy, 226–227 axis of evil, 144–145 deaths in war, 258n.3 economics of nuclear weapons, 111 Iraqis and sanctions, 134 nuclear theme in run-up to war in, 130–131 proliferation fixation, 130–135 sanctions, 145 war against Saddam Hussein’s, 98 war and Washington threat consensus, 132 weapons of mass destruction (WMD), 131 Iraq Study Group Report, 175 irrationality, impact, 101 Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, 204 Israel anxieties about security, 150–151 bombing reactor of fissile material, 262n.12 conference on “A Nuclear Iran,” 263n.31 hostility of Iran, 154 Iran’s capacity to do harm, 262–263n.21 military budget, 111 military value of nuclear arsenal, 110 nuclear weapons capability, 90, 91 perception of United States, 260n.26 possible nuclear weapons use, 138 prestige or influence, 108 “Samson Option,” 110 second Holocaust, 262n.20 Israeli intelligence, Iranian threat, 263n.27 Italy, status, 107 Japan North Korea support, 136 nuclear attacks, 22 status vs. security, 106–107 wake of World War II, 27 Japanese Aum Shinrikyo, 172–173, 227–228 defending homeland and Soviet neutrality, 46 kamikaze, 249n.5 reaction of surrender on, 44–45 shock effect of new weapon, 44 Soviet intervention, 45–46 surrender following bombings, 43 Japanese-American war, hatreds, 45 Jenkins, Brian, 18, 64, 162–163, 166, 170, 189, 209–210, 220, 228, 231–232 Jervis, Robert, irrationality, 36, 101, 108 Johnson, Robert H., nuclear metaphysics, 63–64, 68, 97, 255n.22 Kahn, Herman, 57, 73–74, 92 kamikaze, Japanese, 249n.5 Kaplan, Fred, 64 Kaplan, Lawrence, 261n.4 Kay, David, nuclear arms, 103, 155–156, 157 Kazakhstan, 110, 122–124, 138 Kean, Governor Thomas, worries, xi Keller, Bill, worries, xi, 162–163, 179 Kennedy, President John F., 81 Chinese nuclear test, 96 Cuban missile crisis, 40, 248n.33 missile trade, 248n.33 proliferation problem, 90, 93, 94, 98 test ban treaty, 76 UN as only true alternative to war, 75 war and mankind, 25 Kenney, Michael, Islamic militants, 223 Kerry, John, nuclear weapon worry, 163 Khan, A. Q. bin Laden’s interest in, network, 213 intelligence agencies closing operation, 164–165 selling secrets, 169–170, 207 Khattab, Ibn, connection to bin Laden, 202–203 Khrushchev, Nikita Britain and France reversing invasion at Suez, 249n.12 Cuban missile crisis, 39–40 struggle against capitalism, 34–35 supporting Shevchenko, 248n.31 world war, 33 Korean War, 38, 47–48, 50 Kornienko, Georgy, world war and Soviets, 33 Kosko, Bart, government overestimating threat, 220 Kramer, Stanley, On the Beach, 57 Krauthammer, Charles, Arab world, 261n.1, 261n.4 Kremlin, 246n.15, 247n.22 Kristof, Nicholas, Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe, 181 Kristol, William, 261n.4 Langewiesche, William Atomic Bazaar, 183, 268n.5 book jacket flap, 268n.5 constructing bomb, 111, 173 obtaining nuclear weapons, 105 odds against terrorists, 184 passed “point of no return,” 93 Lapp, Ralph, A-bombs, 242n.19 Laqueur, Walter, proliferation of WMD, 228 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 266–267n.43 leadership, nuclear weapons programs, 113 Lenin, Vladimir, 34 Levi, Michael, 165, 171, 175, 184, 187, 189, 213, 264n.6 Lewis, Jeffrey, 178, 191 Libya, 124–126, 145, 258n.31 likelihood acceptable risk, 197–198 acquisition scenarios, 190–191 arraying barriers, 184, 186 assessing, 186–191 assigning and calculating probabilities, 187–189 comparisons of improbable events, 191–193 multiple attempts, 189–190 policy for reducing, 193–197 probability of nuclear fission bomb, 267n.48 terrorist bomb, 183, 238 World at Risk, 182 Lockerbie bombing, 125, 258n.32 London, image of destruction, 24 longer-term effects, nuclear attack, 8 The Looming Tower, Wright, 201 “loose nukes,”165–168, 208–210, 238 Los Alamos National Laboratory, 267n.48 Los Alamos scientists bomb design, 173–174 difficulties of making nuclear weapons, 174–175 sensitive detection equipment, 176 Los Angeles, port security, 141 Los Angeles International Airport, 19 lottery tickets, terrorism comparison, 191 Lugar, Senator Richard, 20, 171, 181, 194 McCain, Senator John, 130–131, 230 McCarthyism, Communist menace, 49 McCone, CIA Director John, Chinese threat, 91, 96 McNamara, Robert, 66–67, 68, 248n.33 McNaugher, Thomas, missiles, 116 McPhee, John, sense of urgency, 162 Mahmood, Sultan Bachiruddin, 203–205, 271n.16 Majid, Abdul, Pakistani nuclear scientist, 203–204 marijuana bale, smuggling atomic device, 177 Martin, Susan, 232 measured ambiguity, catchphrase, 86 melancholy thought, Winston Churchill, 35 Middle East, 225, 261n.4 Milhollin, Gary, 174, 175 military, Canada, 106 military attacks, appeal of nuclear weapons, 147 military planning, nuclear weapons, 14–15 military strategy, stabilizing or destabilizing, 66 military value, nuclear weapons, 108–110, 236, 237–238 Mir, Hamid, 164, 210–211, 264n.7 credibility of, 273n.36 missile capacity, 153, 154 missile crisis, Cuba, 40 The Missiles of October, Cuba, 40 Mohammed, Khalid Sheikh, 9/11 attack, 206 morality, Canada without weapons, 112–113 Morison, Samuel Eliot, 269n.23 Morrison, Phillip, chance for working peace, 26 Mowatt–Larssen, Rolf, xi, 20 Mueller, Robert, xi, 228, 274n.16, 276n.37 Mukhatzhanova, Gaukhar, points of no return, 94–95 Muller, Richard, 146, 172, 192 multiple groups, likelihood, 189–190 Musharraf, General Pervez, criticism, 260n.24 Muslim extremists, publications of violence, 223 mustard gas, calculation for causalties, 12 mutual assured destruction (MAD), deterrence, 64 Myers, General Richard, 20, 22 Naftali, Timothy, 76, 249n.12, 263n.29 Nagasaki atomic bomb, 9–10 human costs, 141 military value of atomic bomb, 10 surrender of Japanese, 43 taboo of nuclear weapons, 61–63 napalm, 243n.30 National Intelligence Estimate (1958), 119 National Intelligence Estimate (2007), 274n.16 National Planning Association, diffusion, 104 national security threat, terrorism and U.S., 233 NATO missiles, European demonstrations, 60 “naughty child” effect, Russia, 108 neglect, cold war, 86 Negroponte, John, probability of attack, 181 nerve gas, calculation for causalties, 12 Netanyahu, Benjamin, 264n.33 Neufeld, Michael, missiles, 116 neutron bomb, 4, 14, 81 New Jersey Lottery, 270n.6 Nimitz, Admiral Chester W., 269n.23 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), nuclear, 119–121 North Korea American-led forced invading, 247n.27 attention, 108, 238 axis of evil, 144 calm policy discussion, 151, 152–153 deterrence, 262n.19 “eating problem,” 152 hysteria, 263n.25 invasion of South Korea, 49 nuclear weapon, x proliferation, 93 proliferation fixation, 135–137 sanctions, 136, 145 “supreme priority” of, 149–150 Nth country problem, nuclear weapons, 91 nuclear age, verge of new, x nuclear arsenals, 64–65, 145, 237 nuclear bomb, 17, 269n.16 “The Nuclear Bomb of Islam,” bin Laden, 211–212 nuclear crisis, Cuba, 39 nuclear diffusion, 237 nuclear energy, security, 139–140 “nuclear era,” Hiroshima, ix nuclear explosion, 61–62, 181, 243n.9 nuclear fears classic cold war, 56–57 declining again, 60–61 On the Beach, 57 reviving in early 1980s, 58–60 subsiding in 1960s and 1970s, 57–58 nuclear fission bomb, probability of attack, 267n.48 nuclear forensics, 155, 164, 190, 194, 264n.6 nuclear fuel, cartelization, 260n.28 nuclear metaphysics, deterrence, 63–67 nuclear proliferation, xiii, 89 nuclear radiation, dirty bomb, 18 nuclear reactor meltdown, Chernobyl, 7 Nuclear Regulatory Agency, radiation, 7 The Nuclear Revolution, Mandelbaum, 246n.7 nuclear sting operation, 194 Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe, Kristof, 181 nuclear tipping point, Brookings Institution, 93–94 nuclear virginity, Canada, 112 nuclear war, x, 64 nuclear weapons.

…

He had been greatly impressed by Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August and concluded that in 1914 the Europeans “somehow seemed to tumble into war … through stupidity, individual idiosyncrasies, misunderstandings, and personal complexes of inferiority and grandeur.” He had no intention, he made clear, of becoming a central character in a “comparable book about this time, The Missiles of October.”33 Of course the Cuban missile crisis would not have happened, at least in the same way, had there been no nuclear weapons for the Soviets to deploy to the island. The point here, however, is that even with the image of nuclear war staring at them, Kennedy and Khrushchev were referencing horrors remembered from prenuclear wars to warrant their intense concern about escalation.

…

Snow was publishing his alarmist broadside proclaiming it to be a “certainty” that, if the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union were to continue and accelerate, a nuclear bomb would go off “within, at the most, ten years.”4 Nuclear Fear Subsides: The 1960s and 1970s None did, as it happened. Indeed, within, at the most, four years after Snow’s urgent pronouncement, anxiety about nuclear cataclysm began to subside. In the aftermath of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, the United States and the Soviet Union signed some arms control agreements and, although these agreements did not reduce either side’s nuclear capacity in the slightest, the generally improved diplomatic atmosphere engendered a considerable relaxation in fear that they would actually use their weapons against each other.

Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion ofSafety

by

Eric Schlosser

Published 16 Sep 2013

“To get the population used to the idea”: Ibid. If Khrushchev’s scheme worked: Dozens of books have been written about the Cuban missile crisis. I found these to be the most interesting and compelling: Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, “One Hell of a Gamble”: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997); Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Longman, 1999); Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002); Max Frankel, High Noon in the Cold War: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Cold War (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005); and Michael Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War (New York: Knopf, 2008).

…

Minuteman missiles became operational for the first time during the Cuban Missile Crisis. To err on the side of safety, the explosive bolts were removed from their silo doors. If one of the missiles were launched by accident, it would explode inside the silo. And if President Kennedy decided to launch one, some poor enlisted man would have to kneel over the silo door, reconnect the explosive bolts by hand, and leave the area in a hurry. • • • WHILE THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE publicly dismissed fears of an accidental nuclear war, the Cuban Missile Crisis left McNamara more concerned than ever about the danger.

…

“The Madman Nuclear Alert,” International Security, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2003, 150–83. Scott, Len, and S. Smith. “Lessons of October: Historians, Political Scientists, Policy Makers and the Cuban Missile Crisis,” International Affairs, Vol. 70, No. 4, October 1994, 659–84. Searle, Thomas R. “‘It Made a Lot of Sense to Kill Skilled Workers’: The Firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945,” Journal of Military History, Vol. 66, No. 1, January 2002, 103–33. Seckel, Al. “Russell and the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Russell: Journal of the Bertrand Russell Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2, 253–61. Skidmore, David. “Carter and the Failure of Foreign Policy Reform,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 108, No. 4, 1993, 699–729.

Bomb Scare

by

Joseph Cirincione

Published 24 Dec 2011

He created the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency to pursue his vision and to provide some balance in national policy discussions. If he had any doubts about the urgency of reducing nuclear dangers, these were dispelled by the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The discovery that the Soviet Union had placed missiles in Cuba capable of hitting the United States set off a diplomatic and military confrontation that terrified the world. Former Kennedy speech writer Arthur Schlesinger Jr. recalled the crisis in 2006: The Cuban missile crisis was not only the most dangerous moment of the Cold War. It was the most dangerous moment in all human history. Never before had two contending powers possessed between them the technical capacity to destroy the planet.

…

chemical weapons Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) Cheney, Richard China: and India, and Japan, and national security model, and nuclear arms race, nuclear arsenal extent, and regional tensions, U.S. policies Chirac, Jacques Christopher, Warren Churchill, Winston civilian nuclear stockpiles Clinton, Bill: and domestic political model, and nonproliferation regime, and Ukraine Cohen, Avner Cold War: and Atoms for Peace program, Cuban Missile Crisis, and Hiroshima/Nagasaki bombing, and nuclear risk, and regional tensions. See also nuclear arms race; U.S. nuclear guarantees Committee on Assurances of Supply Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) Compton, Arthur Conan, Neal Conant, James Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) core counter-proliferation. See also Bush administration policies Coyle, Philip critical mass cruise missiles CTBT (Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty) CTR (Cooperative Threat Reduction) Cuban Missile Crisis cultural responses: Hiroshima/Nagasaki bombing, nuclear arms race CWC (Chemical Weapons Convention) Czech Republic Davis, Zachary Davy Crockett de Gaulle, Charles DeGroot, Gerard Democritus deterrence.

…

From 1951 to 2000, only some twenty million people suffered that same fate.2 “Well-managed proliferation,” some say, with perhaps double the number of today’s nuclear-armed states, would extend the benefits of nuclear deterrence to many areas of the world, helping to keep the peace in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere.3 The pessimists disagree. They believe that “we lucked out” during the Cold War, when the two nuclear superpowers stood “eyeball to eyeball,” in former secretary of state Dean Rusk’s famous description of the Cuban Missile Crisis.4 The spread of nuclear weapons, they argue, reduces real security. States are not always rational actors, for example. State leaders may act irrationally and initiate a nuclear strike. Nor are states monolithic. Substate actors with their own agendas, such as military commanders, may ignore orders and trigger a nuclear attack.

1983: Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink

by

Taylor Downing

Published 23 Apr 2018

Finally, as it was American policy not to launch nuclear weapons in a first strike, a system had to be devised by which the United States had sufficient nuclear capability held back so that it could survive a pre-emptive attack and still be able to retaliate. All of this was contained within Kennedy’s new Single Integrated Operational Plan. The new SIOP had only just come in when the scariest confrontation of the Cold War to date came with the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962. When the US discovered that Khrushchev was siting missiles in Fidel Castro’s Cuba only a few miles from the Florida coast, it was clear that much of the US mainland would soon be within range of Soviet nuclear weapons. The military wanted to bomb the missile sites before they were finished but Kennedy insisted on restraint and launched a naval blockade of Cuba instead.

…

In addition new radar systems were created to give early warning of the launch of missiles by the other side. Over the years, every innovation within the United States was matched by an equivalent development in the Soviet Union. A vast arsenal of nuclear weapons was created with the capacity to destroy all forms of life on planet Earth. Something had to give. In the wake of the Cuban missile crisis, the United States and the Soviet Union had signed a Partial Test Ban Treaty to stop further atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons. This was a small first step on the long road of slowing up the arms race. In 1968 the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty was signed by the US, the USSR and Britain, which had its own small nuclear capability, prohibiting the export of nuclear technology to other countries (France and China by this time also possessed nuclear weapons but did not sign).

…

And of course also to the maverick Khrushchev, who liked to lead foreign affairs from the front, often deciding on initiatives without consulting his colleagues. These were momentous years in the Cold War that saw a growing split between Moscow and Beijing, the building of the Wall to divide Berlin, the test explosion of a new generation of thermonuclear weapons, and the Cuban missile crisis. Throughout these years Andropov took a moderate position, arguing against a complete falling out with China and in favour of modest reforms in the client states. But he was no liberal, and Khrushchev’s fall in 1964 did not deflect his progress up the political ladder. He stayed loyal to the conventional orthodoxy of Marxism-Leninism, writing a series of articles for party publications with such catchy titles as ‘Leninism Lights Our Way’, ‘Friendship of the Soviet Peoples: The Inexhaustible Source of Our Victories’ and ‘Proletarian Internationalism: The Communists’ Battle Banner.’9 In May 1967 Andropov was appointed head of the KGB, and the following month he became a non-voting member of the Politburo.

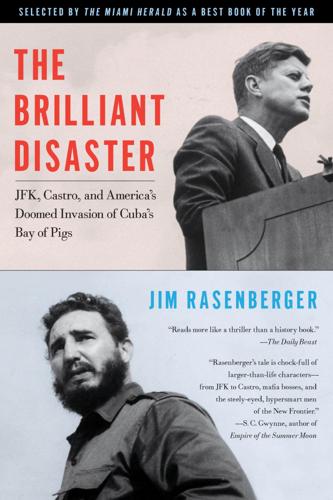

The Brilliant Disaster: JFK, Castro, and America's Doomed Invasion of Cuba's Bay of Pigs

by

Jim Rasenberger

Published 4 Apr 2011

He also draws compelling portraits of the other figures who played key roles in the drama: Fidel Castro, who shortly after achieving power visited New York City and was cheered by thousands (just months before the United States began plotting his demise); Dwight Eisenhower, who originally ordered the secret program, then later disavowed it; Allen Dulles, the CIA director who may have told Kennedy about the plan before he was elected president (or so Richard Nixon suspected); and Richard Bissell, the famously brilliant “deus ex machina” who ran the operation for the CIA—and took the blame when it failed. Beyond the short-term fallout, Rasenberger demonstrates, the Bay of Pigs gave rise to further and greater woes, including the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and even, possibly, the assassination of John Kennedy. Written with elegant clarity and narrative verve, The Brilliant Disaster is the most complete account of this event to date, providing not only a fast-paced chronicle of the disaster but an analysis of how it occurred—a question as relevant today as then—and how it profoundly altered the course of modern American history.

…

—Washingtonian magazine “Rasenberger provides an outstanding chronological day-by-day, nearly minute-by-minute, account of the operation that was first planned during the Eisenhower administration and inherited by JFK.… In the end, Rasenberger makes the case for the large impact that the Bay of Pigs had on historic events that followed, including the Cuban Missile Crisis, the building of the Berlin Wall, the involvement in Vietnam, and the election of President Nixon and Watergate, among others.” —Idaho Statesman “A brilliant book … Students of history too young to remember the events of that April in 1961 will appreciate the thoroughness. For those who lived through that chilling time, it is a page-turner.

…

—Studies in Intelligence “A gripping narrative … Rasenberger provides interesting details about the aftermath, including the Christmas-time release of the captured fighters several years later, his attorney father’s role in that episode, and sums up how the Bay of Pigs continued to reverberate from the Cuban Missile Crisis to Watergate.” —Publishers Weekly “What I love about Jim Rasenberger’s richly detailed, startlingly revisionist account of the Bay of Pigs invasion is his sheer storytelling ability, the wonderful, steady march of plot and counterplot, of heroes and foils. His tale is chock-full of larger-than-life characters—from JFK to Castro, mafia bosses, and the steely-eyed, hypersmart men of the New Frontier.

The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President

by

Bandy X. Lee

Published 2 Oct 2017

As he was reaching to phone the president, a third call came in announcing that the report of the incoming missiles was a false alarm caused by a computer glitch. It is extremely disconcerting to note that false alarms and accidents are by no means a rare occurrence. The Cuban Missile Crisis: President Kennedy Unlike the nightmarish false alarm of 1979, lasting five minutes, which few were aware of, the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 lasted thirteen white-knuckle days, played out before the entire world in a series of very real, terrifying actions and reactions between America and the USSR. At several junctures, the world was within an eyelash of all-out nuclear holocaust.

…

Mika explains how tyrannies are “toxic triangles,” as political scientists call them, necessitating that the tyrant, his supporters, and the society at large bind around narcissism; while the three factors animate for a while, the characteristic oppression, dehumanization, and violence inevitably bring on downfall. In “The Loneliness of Fateful Decisions,” Fisher recounts the Cuban Missile Crisis and notes how, even though President Kennedy surrounded himself with the “best and the brightest,” they disagreed greatly, leaving him alone to make the decisions—which illustrates how the future of our country and the world hang on a president’s mental clarity. In “He’s Got the World in His Hands and His Finger on the Trigger,” Gartrell and Mosbacher note how, while military personnel must undergo rigorous evaluations to assess their mental and medical fitness for duty, there is no such requirement for their commander in chief; they propose a nonpartisan panel of neuropsychiatrists for annual screening.

…

Returning to our historical examples of nuclear emergencies, is there anyone who could possibly believe DT would have shown Brzezinski’s grace under pressure had he himself received that 3:00 a.m. call? If, indeed, Trump harbors grandiose and paranoid delusions (for which there is mounting evidence), he would have launched missiles faster than he fires off paranoid tweets on a Saturday morning. Given the thirteen days of excruciating tension during the very real nuclear threat of the Cuban Missile Crisis, is there anyone who possibly believes that DT could have demonstrated JFK’s composure, wisdom, and judgment, especially in the face of unanimous pressure from his military advisers? If DT were indeed merely “crazy like a fox,” it would still be a huge stretch—but, increasingly, that appears not to be the case.

If Then: How Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future

by

Jill Lepore

Published 14 Sep 2020

Martin, Adlai Stevenson and the World, 719–21. “U.S. Imposes Arms Blockade,” NYT, October 23, 1962. Aldous, Schlesinger, 292–93. See also “The World on the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis—Day 10,” Kennedy Library, https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct25/. Martin, Adlai Stevenson and the World, 728–37. “The World on the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis—Department of State Telegram,” Kennedy Library, https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct26/doc4.html. Aldous, Schlesinger, 290. Martin, Adlai Stevenson and the World, 728–37. Paine Knickerbocker, “Gene Burdick Attacks a ‘Lie’ on ‘Fail-Safe,’ ” San Francisco Chronicle, October 9, 1964.

…

Stevenson, echoing warnings issued by the Kennedy administration, said that the United States would consider the establishment of a missile site as an act of aggression. On October 14, Stevenson met with Kennedy in New York. That same day, a CIA-run U-2 flying a secret surveillance mission over Cuba took photographs that revealed the existence of a launching pad and at least one nuclear missile in San Cristóbal.33 The Cuban Missile Crisis had begun. Over the next thirteen days, the United States—and the world—would come closer to nuclear war than at any other point during the Cold War. On Tuesday, October 16, Kennedy called for the first of a series of secret meetings in the White House of a group that came to be called “ExComm”—the Executive Committee of the National Security Council.

…

By the time it had been read in the White House, Khrushchev, not having received any reply, had already sent a second, harder-line message. The delay might have been fatal. In Fail-Safe, Burdick and Wheeler had argued that a failure of communications, even just a small computer glitch, could lead to Armageddon. After the Cuban Missile Crisis ended, representatives of the United States and the USSR met in Geneva to sign a “Memorandum of Understanding . . . Regarding the Establishment of a Direct Communications Link”: they set up a hotline between the Kremlin and the Pentagon, a link by teletype. Eugene Burdick took credit for that idea, since this very hotline links Moscow and Washington in Fail-Safe.

I, Warbot: The Dawn of Artificially Intelligent Conflict

by

Kenneth Payne

Published 16 Jun 2021

Why would they favour the offence? Speed is certainly important, but there’s more at work than that. First a caveat—the distinction between offence and defence can be rather subjective, and sometimes depends on the intent with which the weapon is used, rather than its physical capabilities. In the famous Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, for example, President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev fell to debating whether the missiles that the USSR had secretly sent to their Cuban ally Fidel Castro were offensive weapons.17 Yes, said Kennedy, arguing that they posed a direct threat to the security of the United States, and were a dangerous escalation in the already febrile Cold War.

…

You could model them formally, via game theory, using probabilities and payoffs. But the big question with both metaphors was how to translate them into international politics. Was there a real-world version of chicken? Some genuine crises did have elements of Schelling’s logic to them, whether or not that was intentional. In the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, there was plenty of randomness to contend with, like the accidental U2 surveillance flight that strayed into Soviet airspace in the middle of the drama. And sometimes leaders deliberately cultivated the erratic, even unhinged, behaviour of Schelling’s man on a clifftop. President Nixon became the arch exponent of what he termed the ‘madman theory’ of statecraft—crafting an image of an irascible leader who might take dangerous escalatory steps unless the enemy backed down.

…

‘Merkel Is “Outraged” by Russian Hack but Struggling to Respond’, The New York Times, 13 May 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/13/world/europe/merkel-russia-cyberattack.html. 17. See especially, Beschloss, Michael R. Kennedy v. Khrushchev: The Crisis Years, 1960–63. London: Faber and Faber, 1991; and Fursenko, A. A., and Timothy J. Naftali. One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, Kennedy, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1958–1964. London: Pimlico, 1999. 18. Elsewhere I argue for the offence, Payne, Kenneth. ‘Artificial intelligence: a revolution in strategic affairs?’ Survival 60, no. 5 (2018): 7–32. Agreement comes from Altmann, Jürgen and Frank Sauer, ‘Autonomous Weapon Systems and Strategic Stability’, Survival 59, no. 5 (2017): 117–142; one argument about defence dominance not yet in print but much discussed among theorists has to do with the vulnerability of AI platforms to electronic warfare.

The Age of Radiance: The Epic Rise and Dramatic Fall of the Atomic Era

by

Craig Nelson

Published 25 Mar 2014

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. Crowell, William P. “Remembrances of Venona.” CIA Headquarters, July 11, 1995. http://www.nsa.gov/public_info/declass/venona/remembrances.shtml. “Cuban Missile Crisis.” AtomicArchive.com. http://www.atomicarchive.com/Docs/Cuba/index.shtml. “Cuban Missile Crisis.” Wilson Center Digital Archive. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/collection/31/Cuban-Missile-Crisis. Cumings, Bruce. “Korea: Forgotten Nuclear Threats.” Le Monde Diplomatique, December 2004. Curie, Ève. Madame Curie. New York: Doubleday, 1937. Curie, Marie. Cher Pierre que je ne reverrai plus (Journal 1906–1907).

…

Robert Oppenheimer,” 261–65 iodine, 188, 215, 271, 308, 336, 350, 356, 365, 377 Iran, 6, 338, 373 Israel, 334, 337–38, 360, 370 Jaczko, Gregory, 355 Japan, 364 demand for surrender of, 211 earthquakes in, 342–45, 352–53 firebombing of, 209–11 nuclear power plants in, 340–41, 342 nuclear research in, 210 regulation of nuclear technology in, 341 thermonuclear testing affecting fishermen from, 273, 340 See also Fukushima Daiichi power plant disaster, Japan; Hiroshima, Japan, bombing; Nagasaki, Japan, bombing Joachimsthal, Czechoslovakia, mine, 36, 195, 231 Johnson, Lyndon, 211, 337 Joliot-Curie, Irène, 61, 82, 376 death of, 188 deuterium source for, 120 education of, 49–50 family background of, 25, 30, 31, 39, 41, 48 fame of, 98, 369 Fermi’s research and, 90 Hahn and Meitner on errors in research of, 90 man-made radiation research of, 61, 105 marriage of, 51–52 Meitner’s research and, 103 nuclear fission research of, 112, 117, 120, 142, 193 uranium sources and, 154 work with husband Fred, 52–53, 54, 61, 62, 90, 103, 112 Joliot-Curie, Jean-Frédéric (Fred), 376 deuterium source for, 120 French resistance work of, 188 health of, 188 marriage of, 51–52 nuclear fission research of, 142 uranium sources and, 154 work with wife Irène, 52–53, 54, 61, 62, 90, 103, 112 Jungk, Robert, 178, 180, 181 Kahn, Herman, 290–91, 292 Kan, Naoto, 346, 351, 352, 357 Karle, Isabella, 127 Kaufman, Irving, 241–42 Kazakhstan, atomic tests in, 233, 235, 336, 372 Kelvin, Lord William Thomson, 22–23, 39 Kennan, George¸ 256–57 Kennedy, John F., 265 arms race and, 276–77, 282, 289, 376 atomic satellite programs and, 305–06 Bay of Pigs invasion and, 286, 293–94 Cuban Missile Crisis and, 294–99 fallout shelters and, 286 joint moon mission proposal and, 284 Khrushchev and, 285–86 missile gap and, 282, 285–86, 293–94 nuclear air power programs and, 305 nuclear defense strategies and, 288–89 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and, 374 presidential campaign against Nixon by, 282, 284–85 Kennedy, Robert, 297 KGB, 172, 238, 240, 292, 293, 327 Khan, Abdul Qadeer, 338 Khrushchev, Nikita, 370–71 arms race and¸ 245, 254, 267, 276–77, 284–85, 373 Bay of Pigs invasion and, 286, 293–94 Cold War and, 300 Cuban Missile Crisis and, 294–95, 296–97, 298, 299 joint moon mission proposal and, 284 rise to power by, 254 Szilard’s meeting with, 267 US perception of threats from, 256 Khrushchev, Sergei, 246, 256, 284, 290, 294–95, 297, 298 Killing a Nation defense strategy, 277, 292, 293, 372 Kim Il Sung, 243, 373 King, Ernest, 221–22 Kissinger, Henry A., 282, 335 Kistiakowsky, George (Kisty), 169, 171, 173, 196, 197–98, 199, 202, 228 Klaproth, Martin, 25 Knuth, August, 130 Kolbert, Elizabeth, 360–61 Korea.

…

Szilard was promised fifteen minutes but unsurprisingly to any of his friends, the talk went on for two hours, with Khrushchev finally agreeing to the possibility of an international agency that would limit arms escalation and a communications hotline between the Soviet premier and the American president in case of nuclear crisis. That hotline would also appear in Dr. Strangelove, but would not exist in the real world until the Cuban Missile Crisis and its series of delayed telegrams made it clear to both sides that this was worthwhile. In April 1958, the USSR unilaterally suspended nuclear testing, and after the AEC’s Strauss warned Eisenhower that a reciprocal American test ban would turn Los Alamos and Livermore into “ghost towns,” the president growled that he “thought scientists, like other people, have a strong interest in avoiding nuclear war.”

The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

by

Toby Ord

Published 24 Mar 2020

A key difference between the two framings is that the pacing problem refers to the speed of technological change, rather than to its growing power to change the world. 58 Sagan (1994), pp. 316–17. 59 Barack Obama, Remarks at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (2016). Consider also the words of John F. Kennedy on the twentieth anniversary of the nuclear chain reaction (just a month after the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis): “our progress in the use of science has been great, but our progress in ordering our relations small” (Kennedy, 1962). 60 In his quest for peace after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy (1963) put it so: “Our problems are manmade—therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.” Of course one could have some human-made problems that have gone past a point of no return, but that is not yet the case for any of those being considered in this book.

…

His name was Valentin Savitsky. He was captain of the submarine B-59—one of four submarines the Soviet Union had sent to support its military operations in Cuba. Each was armed with a secret weapon: a nuclear torpedo with explosive power comparable to the Hiroshima bomb. It was the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Two weeks earlier, US aerial reconnaissance had produced photographic evidence that the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles in Cuba, from which they could strike directly at the mainland United States. In response, the US blockaded the seas around Cuba, drew up plans for an invasion and brought its nuclear forces to the unprecedented alert level of DEFCON 2 (“Next step to nuclear war”).

…

But as more and more behind-the-scenes evidence from the Cold War has become public, it has become increasingly clear that we have only barely avoided full-scale nuclear war. We saw how the intervention of a single person, Captain Vasili Arkhipov, may have prevented an all-out nuclear war at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis. But even more shocking is just how many times in those few days we came close to disaster, only to be pulled back by the decisions of a few individuals. The principal events of the crisis took place over a single week. On Monday, October 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy gave a television address, informing his nation that the Soviets had begun installing strategic nuclear missiles in Cuba—directly threatening the United States.

Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 1 Jan 2003

With different threats in mind, strategic analyst Michael Krepon regarded the final days of 2002 as “the most dangerous time since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.” A high-level task force concluded that “we are entering a time of especially grave danger [as we] are preparing to attack a ruthless adversary [Iraq] who may well have access to [weapons of mass destruction].” Such dangers are likely to become even more grave in the longer term as a consequence of the easy resort to violence, as many have pointed out.1 The reasons behind these concerns merit close attention, but too narrow a focus can be misleading. We can gain a more realistic perspective on them by asking why the Cuban missile crisis was such a “dangerous time.”

…

Rather, they were spoken by the respected liberal elder statesman Dean Acheson in 1963. He was justifying US actions against Cuba in full knowledge that Washington’s international terrorist campaign aimed at “regime change” had been a significant factor in bringing the world close to nuclear war only a few months earlier, and that it was resumed immediately after the Cuban missile crisis was resolved. Nevertheless, he instructed the American Society of International Law that no “legal issue” arises when the US responds to a challenge to its “power, position, and prestige.” Acheson’s doctrine was subsequently invoked by the Reagan administration, at the other end of the political spectrum, when it rejected World Court jurisdiction over its attack on Nicaragua, dismissed the court order to terminate its crimes, and then vetoed two Security Council resolutions affirming the court judgment and calling on all states to observe international law.

…

The word noise connotes “discordant, unintelligent clamor,” Costigliola adds.11 Perhaps many Europeans might not be too happy about the significance accorded their survival, even if respected US commentators are confident that their reluctance to “come along” is a sign of “paranoid anti-Americanism,” “ignorance and avarice,” and other “cultural deficiencies.” International terrorism dominated the headlines as the retrospective conference took place; so did Washington’s allegedly novel doctrine of regime change. But there is little novel here: The Cuban missile crisis grew directly out of a campaign of international terrorism aimed at forceful regime change. Historian Thomas Paterson concludes, quite plausibly, that “the origins of the October 1962 crisis derived largely from the concerted U.S. campaign to quash the Cuban revolution” by violence and economic warfare.12 We can gain a better insight into current implications by looking at how the crisis evolved, and the guiding principles that motivated policy.

Destined for War: America, China, and Thucydides's Trap

by

Graham Allison

Published 29 May 2017

Reflecting on his own responsibilities, Kennedy pledged that if he ever found himself facing choices that could make the difference between catastrophic war and peace, he would be able to give history a better answer than Bethmann Hollweg’s. Kennedy had no inkling of what lay ahead. In October 1962, just two months after he read Tuchman’s book, he faced off against Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in the most dangerous confrontation in human history. The Cuban Missile Crisis began when the United States discovered the Soviets attempting to sneak nuclear-tipped missiles into Cuba, a mere ninety miles from Florida. The situation quickly escalated from diplomatic threats to an American blockade of the island, military mobilizations in both the US and USSR, and several high-stakes clashes, including the shooting down of an American U-2 spy plane over Cuba.

…

In analyzing how wars break out, historians focus primarily on proximate, or immediate, causes. In the case of World War I, these include the assassination of the Hapsburg archduke Franz Ferdinand and the decision by Tsar Nicholas II to mobilize Russian forces against the Central Powers. If the Cuban Missile Crisis had resulted in war, the proximate causes could have been the Soviet submarine captain’s decision to fire his torpedoes rather than allow his submarine to sink, or a Turkish pilot’s errant choice to fly his nuclear payload to Moscow. Proximate causes for war are undeniably important. But the founder of history believed that the most obvious causes for bloodshed mask even more significant ones.

…

Think again about the game of chicken discussed in chapter 8. Consider each clause of the paradox. On the one hand, if war occurs, both nations lose. There is no value for which rational leaders could reasonably choose the deaths of hundreds of millions of their own citizens. In that sense, in the Cuban Missile Crisis President Kennedy and Chairman Khrushchev were partners in a struggle to prevent mutual disaster. But this is the condition for both nations, and the leaders of both nations know it. Thus, on the other hand, if either nation is unwilling to risk waging (losing) a nuclear war, its opponent can win any objective by creating conditions that force the more responsible power to choose between yielding and risking escalation to war.

The Secret War Between Downloading and Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine

by

Peter Lunenfeld

Published 31 Mar 2011