Mastering Private Equity

by

Zeisberger, Claudia,Prahl, Michael,White, Bowen

,

Michael Prahl

and

Bowen White

Published 15 Jun 2017

These teams act both as a first point of contact for intermediaries and as drivers of the firm’s proprietary deal flow. However, deal sourcing typically involves the entire firm, as there is no telling where the next quality lead will come from, e.g. former portfolio firms and their owners or entrepreneurs may well add to the deal flow. There are two main ways to source deals: proprietary deal flow sourced through in-house resources and intermediated deal flow sourced through paid third parties. PROPRIETARY DEAL FLOW: Proprietary deals are sourced directly by a PE firm without the assistance of financial advisors.

…

Some covenants are checked on a regular basis (maintenance covenants) while others are only tested upon the occurrence of a specific event (incurrence covenants). Data Room A database (physical or virtual) established by a target company and its advisors that contains all material documentation for due diligence. Deal Flow Investment opportunities available to a PE firm. If sourced by a PE firm directly it's called “proprietary” deal flow, if through an advisor (e.g., banks, accountants) then “intermediated” deal flow. Deal-by-deal Structure In a deal-by-deal fund structure, a dedicated vehicle will be created for the purposes of making an investment in a single target opportunity. Debt Capacity An assessment on the amount of debt a company can service and pay back over a certain period.

…

PE professionals express a preference for proprietary deals as they are often more tailored to a fund’s size and sector requirements, provide a direct link to a target company’s management team, and have a higher chance for exclusivity than deals sourced through intermediaries. In addition, proprietary deals are often faster and cheaper to execute once they mature. LPs clearly favor firms with strong proprietary deal flow. However, proprietary deal flow has certain drawbacks. As proprietary targets are often not in urgent need of capital, it can take a significant amount of time—often years—for a PE firm to build the relationship and make a case for its involvement, with no guarantee that an investment will ultimately materialize.

Mastering the VC Game: A Venture Capital Insider Reveals How to Get From Start-Up to IPO on Your Terms

by

Jeffrey Bussgang

Published 31 Mar 2010

The process by which VCs consider deals—known as processing the “deal flow”—is one of the most fascinating things about the VC business. In most VC firms, the deal flow process is most evident when partners gather to discuss which deals they will pursue and why, and which ones they’ll pass on. This conversation usually takes place in “the Monday morning meeting,” which is the meeting of the VC firm’s partners held each week at their offices. It is dreaded by entrepreneurs, because the thumbs-up or thumbs-down call usually comes in right after this meeting has adjourned. How to best manage their deal flow is a quandary for the VC. A VC wants to see every interesting start-up that is happening, particularly those led by proven entrepreneurs.

…

The more deals a VC sees, the more likely he will have the opportunity to select a high-quality deal in which to invest. And there’s a secondary benefit to having high-volume, high-quality deal flow as well. By looking at as many deals as possible, VCs become smarter investors—learning a little something from every deal seen, and becoming more adept at detecting useful patterns. The volume of possible deals is so great, however, that no partner can review all the business plans, let alone fund all the companies that might be worthy. A VC with a healthy deal flow may get an opportunity to review as many as three hundred to five hundred deals per year. Most “active” VCs—those who will join the board of the company in which they invest—typically have capacity to do no more than one or two deals a year.

…

“Passive” VCs—those who may come in at a later stage, take a smaller ownership stake, and don’t join the board—have greater deal capacity but still only do three or four deals annually per partner. So for VCs, managing their deal flow is a matter of examining as many deals as possible, winnowing them down to a manageable number as efficiently as possible, and following a process of evaluation that is as effective as possible. It is essentially a sales process, with a bit of mutual selling (and evaluating) by both the VC and the entrepreneur, and it usually proceeds through a number of stages before the deal is closed. As I’ve mentioned, typically a deal flows from an initial meeting (a half hour to an hour) to a follow-up meeting (one or two hours, when more specific issues are addressed) to the light diligence phase.

Buy Then Build: How Acquisition Entrepreneurs Outsmart the Startup Game

by

Walker Deibel

Published 19 Oct 2018

Which brings us to the lesson: you need to get upstream. In investment banking and private equity, professionals look for “deal flow.” Since they are evergreen professional buyers, what typically differentiates the pros in the business is “who has the deal.” Getting the best deal flow means that a firm is always at the top of the list for potential sellers and somehow gets early looks at the best opportunities. The opacity and fragmentation of the market allows for this and makes navigating deal flow a 89 major part of what makes a good firm—they get access to the good deals! This is exactly what you are trying to achieve, and I assure you professional buyers aren’t hanging out exclusively on bizbuysell.

…

This is exactly what you are trying to achieve, and I assure you professional buyers aren’t hanging out exclusively on bizbuysell. Instead, you need to get out and meet the people who have deal flow in your area. In your case, this is the business brokers, intermediaries, I-bankers, and M&A 44 Advisors who get the listings in the first place. If you need proof of this, I would ask you to draw a on your own experience looking for a job online. Using online job post sites like Monster and CareerBuilder can work, but more than likely, focusing on them just kills your job search. This is because they are mostly geared toward entry-level candidates who aren’t networked well, they are postings that generate thousands of applicants, and frankly, if the company couldn’t find anyone they knew to hire for the job, then it ends up on a website as an afterthought.

…

Finding a business is no different. This trend exists at every level of the market, from Main Street to solidly middle-market investment bankers, from bizbuysell to Axial.net; the deal doesn’t hit the website if they can engage a buyer before they have to. These sites exist for people who do not have deal flow themselves. Yet at least 80 percent of the private equity professionals I know that pay the high fees to services like Axial have expressed in one way or another that they aren’t there to get the specific deals on the platform. Instead, they are there to learn who has the deals, then build relationships with them.

The Website Investor: The Guide to Buying an Online Website Business for Passive Income

by

Jeff Hunt

Published 17 Nov 2014

Other marketplaces may have some of these same options or others that Flippa doesn’t have, but the principles will apply just about anywhere that you might list your site for sale. Clicking on SELL in Flippa will initiate a series of forms prompting you for details about your website. The first decision point is whether to list your website under Flippa’s exclusive brokerage service called Deal Flow. Deal Flow is for sites valued at greater than $10,000. Deal Flow auctions are advertised to a group of pre-qualified buyers. Flippa will look at your site and do some pre-validation prior to presenting the listing to its buyer list. The listing fee is free. There is a 10% success fee paid by the seller and a $1,000 finder’s fee paid by the buyer at the time of this writing.

…

In addition, buyers and sellers are pre-qualified, so you don’t have to spend as much time checking each other out and the listings are not made public, so any proprietary info has a more limited viewing audience. The high-end buyers that participate in Deal Flow also look at normal Flippa listings, so you won’t necessarily miss out on their perusal, but you will probably have a better chance at attracting their attention with Deal Flow. The next important question in the listing process is whether to have Google Analytics information verified by Flippa. I suggest you do this if at all possible. This lends credibility to your listing. When presented with “The Pitch” form, you will enter your listing’s title, called Tagline by Flippa.

…

Some go for as low as $10,000, but most have minimums of $25,000, $50,000, or even $100,000. This is by no means a comprehensive list of website brokers, but some of the popular ones include: • AcquisitionsDirect.com • DaltonsBusiness.com • DigitalExits.com • EmpireFlippers.com • FEInternational.com • FlipFilter.com • Flippa.com (Deal Flow) • Latonas.com • QuietLightBrokerage.com • TheWebsiteBrokers.com • W3BusinessAdvisors.com • WebsiteProperties.com • WeSellYourSite.com Unlike traditional brick and mortar business brokers, website brokers sell Internet properties whose assets are primarily digital. They understand the importance of certain metrics that are specific to websites, like traffic statistics, conversion rates, email open rates, and earnings per page view.

One Click: Jeff Bezos and the Rise of Amazon.com

by

Richard L. Brandt

Published 27 Oct 2011

So he decided to spice up his love life and become what he was later to describe as a “professional dater.” He took a particularly geeky approach to the problem. Having always been the methodical type, he set about trying to find a great girlfriend by using the same methodology that Wall Street bankers use to find a great investment: He set up a “deal flow” chart. Wall Streeters’ deal flow charts are listings of all the attributes a deal must have before they will take a chance on it, in order to remain objective and not be influenced by an emotional response. Likewise, Jeff’s “women flow” chart listed the criteria his potential partners had to have before he would consummate a deal.

…

His big challenge was to figure out what product to sell. To answer that question, he created a deal flow chart to analyze several opportunities. He made a list of twenty possible products. Which one offered the best set of features for quickly building an Internet presence? “I was looking for something that you could only do online, something that couldn’t be replicated in the physical world,” he said. The answer turned out to be books. Imagine the criteria an ambitious young executive with a penchant for computers would put on a deal flow list. Familiar product: Everyone knows what a book is. When ordering a particular title online, nobody has to worry about whether it is a cheap knockoff or an imitation, as they might with, say, consumer electronics.

…

The conversation between Bezos, Kaphan, and his friend lasted for several months as Bezos made his plans. Bezos had not yet decided where to base his company. While most entrepreneurs were moving to Silicon Valley as the obvious place to become an entrepreneur, Jeff took a different approach: Yes, he would create another deal flow list to help decide. He came up with three criteria: It had to be a place with an established population of entrepreneurs and software programmers. He wanted to locate the business in a state with a relatively low population because only residents of that state would have to pay sales tax on the products he sold.

How to Be the Startup Hero: A Guide and Textbook for Entrepreneurs and Aspiring Entrepreneurs

by

Tim Draper

Published 18 Dec 2017

The network limped along for several years until we hired Gabe Turner, who steadily and systematically brought the network back to life, rebranding it as the Draper Venture Network (DVN) because of branding confusion issues we ran into, and building on its strong global reputation. Today, the DVN spans 14 relationship firms, with 8 alumni firms, covering over 50 cities around the world and managing several billion dollars in nearly 1000 companies. And the power of the network is unprecedented for deal flow, due diligence, best practices, and the connections the teams make for their portfolio companies around the world. Companies in the network include Right-Click Capital in Australia, Dalus Capital in Mexico, Wavemaker in Singapore and South East Asia, Blume Ventures in India, as well as the various Draper branded funds: Draper Dragon in China, Draper Athena in Korea, Draper Nexus in Japan, Draper Esprit in the UK, Draper Triangle in the Midwestern US, Draper Aurora in Russia, and Draper Associates in Silicon Valley as well as three smaller firms in our DVN beta program, and we are adding more partners every year.

…

More nodes on a network increase the power of the network as the square of the number of nodes on the network increases. This concept is known as Metcalfe’s Law, after entrepreneur, venture capitalist, educator and pundit Bob Metcalfe. The DVN allows me to evaluate and potentially fund any company from anywhere in the world. My deal flow has also expanded and improved. My judgment can only have been improved by seeing more companies from more regions, and Draper Associates’ returns should continue to improve because we see so many more companies for each one I invest in. Additionally, my entrepreneurs can easily grow their businesses internationally because our network has such great reach.

…

The company built the platform out, and then we easily raised $300 million through a brokerage firm from small investors who wanted to participate in the returns venture capital could provide them. Our pitch was simple. DFJ had an extraordinary track record, and we had a great global network of funds that could all generate deal flow for the fund. We pitched that we would manage the fund, and that was an even bigger attraction. Our thinking was that we would be able to invest alongside our existing funds with the same terms we got for our private investors, and the public would finally be able to invest in venture capital. All of this was cleared and recleared with attorneys and government officials.

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by

Keach Hagey

Published 19 May 2025

“Paul wrote honest, helpful stuff that people read and respected—he didn’t do what we did, which was to comb through hundreds of startups hunting for investments. He let the founders come to him, entranced by the power and truth of his writing.” Graham saw the program as doing something fundamentally different than what venture capitalists do. “These later-stage investors are playing a zero-sum game. There is a fixed amount of deal flow, and they’re just trying to find the good startups in it, whereas YC is trying to encourage more good startups to be founded,” Graham said. “We knew this was possible because we knew how ambivalent we were about starting a startup ourselves. We knew how lame, in certain respects, founders could be and still be successful.”

…

He looked at the carnage around him, the partners who had sat on boards for years watching their companies now go bankrupt, and wondered if he’d joined the party too late. Moritz assured him he had not. “You’re coming at the perfect time,” Moritz said. To survive, he and his fellow new partners, like Jim Goetz and Roelof Botha, tried to think of novel ways to learn about promising startups before anyone else. “We’d gotten very aggressive about finding new deal flow, just looking where everybody was not looking,” he said. One technique was to forge relationships with the attorneys that startup founders might go to form their companies. “You know, take them out to lunch, take them out to dinner. We even started doing office hours where we take these attorneys and we’d say, ‘I don’t care what the company does, there’s no filter, every young founder you’re working with, I will give them twenty minutes.’ ” One of the attorneys McAdoo cultivated via regular lunches was Mailliard.

…

Y Combinator posted the SAFE legal documents on its website, open-source-style, and it quickly became the industry standard.7 Through Altman, Graham and Livingston also met McAdoo, who eventually led a Sequoia investment into Y Combinator batches, giving the firm a prime position in evaluating a new crop of pre-vetted, promising startups looking for funding—the all-important concept in venture capital known as “deal flow.” Even before his own startup was off the ground, Altman proved to be the indispensable startup connector. “He knows everyone,” Graham wrote in 2012. “He has not only done countless introductions for alumni, but did most of the initial intros in Silicon Valley for YC itself. . . . YC now does many intros per day, but if you follow the tree back to the beginning, Sam was the root node.”8 The arrival of Y Combinator in Silicon Valley that winter accelerated the rush of optimism in the tech sector.

The Middleman Economy: How Brokers, Agents, Dealers, and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit

by

Marina Krakovsky

Published 14 Sep 2015

“It’s not like an agency—‘I’ll introduce you to these Hollywood producers, and if you raise money, I’ll get five percent of the profit you make at the end of the day’—it never was like that.”6 At one point, as I began posing a question about “deal flow,” a piece of VC jargon that had slipped from his lips, he interrupted to make sure I didn’t get the wrong idea. “A lot of people look at deal flow,” he said, “but these are all human beings, and we try not to call companies ‘deals’ or ‘deal flow.’” Similarly, when I wondered whether he’s thought about what his network looks like, he cut me off, as if objecting to the instrumental implication of the question. “I don’t look at it as tools, I look at it as my friends,” he said.

…

How Contrarianism Attracts Opportunity * * * In pitch fests and media interviews, the Floodgate partners have expressed these ideas many times; the more they do, and the more times they put their money where their mouths are through their funding decisions, the better known these VCs will become as entrepreneur-friendly, especially among entrepreneurs who don’t fit the traditional mold. That gives the Floodgate partners an edge in the competition among VCs for good deal flow. A quarter of Floodgate’s portfolio companies are women-led, as are a quarter of the companies pitching Floodgate.44 If the next Leah Busque is seeking seed-stage financing, it’s a good bet Floodgate will be high on her list of VC firms to pitch. “We fundamentally believe that some woman will start a company worth more than $50 billion in the next five to ten years,” Maples says, “and we have a better chance of winning her preference if we’re not a firm full of 6-foot-tall white dudes.”

Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley

by

Antonio Garcia Martinez

Published 27 Jun 2016

Heavyweight funds like Mayfield and August knew this, and started doing seed investing, not to own some little piece of a company (they could write small checks all day and still not invest their entire funds) but merely as an option on the real rounds down the road. Which brings us (finally) to our point: in the day-to-day, the lifeblood of a VC wasn’t money, it was deal flow. Getting a first look at a potential Uber or Airbnb is what distinguished a first-class VC from an also-ran. Given Y Combinator’s immense success in drawing the best entrepreneurs, it had a quasi-stranglehold on the best early-stage deal flow in the Valley. And since early-stage deal flow today translated into later-stage deal flow tomorrow, via the follow-on investing phenomena described, Y Combinator was the gatekeeper to the best present and future deals in the Valley.

…

That money was just as green either way. That meant that those funds would start losing YC deals wholesale to their competitors, and, as we reviewed earlier, getting locked out in the early rounds likely meant the same in the even juicier later ones. PG was about to flush a whole chunk of their deal flow down the toilet, just like that. I smiled, imagining the sputtering fits pitched by the partners over at Mayfield and August when PG read them the riot act. YC was actually willing to sever ties with some of the most illustrious names in Valley investing over the piss squirt that was AdGrok. It may seem like nothing to you, reader, who maybe inhabits a normal realm of twenty-first-century economic life where things like tit-for-tat reciprocity enforce social codes.

…

On another side, Murthy’s moneymen were likely yelling at him to stop being an asshole and respect unwritten Valley rules about not frivolously picking expensive fights with nascent startups. Thanks to PG’s expulsion of these money changers from the Temple of Demo Day, and what that meant for their future deal flow, the VCs’ very livelihoods were now at risk due to Murthy’s bullshit. And by the way, why aren’t you focusing on our investment, the ailing Adchemy, anyhow? Finally, the next big partner Murthy critically needed, the last card he had to play as entrepreneur with a troubled startup, was telling him the deal hinged on settling the AdGrok mess, or else.

Brotopia: Breaking Up the Boys' Club of Silicon Valley

by

Emily Chang

Published 6 Feb 2018

Specifically, she claimed a male partner, Chi-Hua Chien, suggested that women not be invited to an upcoming dinner hosted by partner Al Gore, because they “kill the buzz.” On the stand, Chien denied saying this but confirmed that an all-male dinner did occur at Gore’s home and that the number of guests was limited because of the size of his living room. Chien also testified that he often invited Pao to get-togethers that might lead to deal flow but she was too busy to attend. Kleiner’s attorneys presented multiple emails that showed Chien inviting Pao to meetings he thought she might find interesting. The implication was that Pao chose to pass on critical social opportunities that might have advanced her position within the firm. • • • WHETHER PAO WASN’T INVITED, or chose not to attend, or was invited but didn’t feel welcome, her experience is a stark reminder that venture capital partnerships are deeply competitive and political.

…

“I think VC has been a boys’ club, and even if many of those boys have great intentions, many of them don’t realize the privilege that they have being male and mostly white and how things they do or say may unintentionally make others feel excluded or uncomfortable or discouraged. At the time, I didn’t think of a lot of those things as bias. I just thought, ‘Oh, there’s a cool kids’ club, and I’m not in it.’” Lee added that when women aren’t invited to male-only social events, or don’t attend, they often don’t know what they’re missing. “You don’t realize they trade deal flow and talk about what they’ve learned and what’s a hot deal,” Lee said. “When that hot deal is raising their next round and someone says, ‘Who should we call?’ Someone says, ‘Oh, how about Jeff?’ And Jeff gets the deal.” When I asked Lee if she felt that these circumstances qualify as gender discrimination, she paused, then said, “I think most women at VC firms, most women in business, if they wanted to could probably put together a case.”

…

In 2016, Sequoia launched a mentorship program called Ascent that pairs women in technical roles with senior women across the industry (though one female founder who was asked to join the program as a mentor said she felt as if Sequoia was asking her to do free work, while the firm took all the credit). Botha has also been working to add more women to Sequoia’s super-secretive “scout” program, a large group of mostly entrepreneurs who unofficially refer deals back to the firm, then get a cut. It’s an ingenious way to get deal flow, but once again male dominated. When the Wall Street Journal compiled a long list of known Sequoia scouts in 2015, only 5 out of 78, or about 6 percent, were women. By September 2017, the number of female scouts had jumped to 25 percent. Still, women have a long way to go before they can have even close to an equal voice at the venture capital table.

Women Leaders at Work: Untold Tales of Women Achieving Their Ambitions

by

Elizabeth Ghaffari

Published 5 Dec 2011

My second job was to improve the deal flow, meaning the number of quality deals presented to the group. Those two metrics go hand in hand. If you don’t have good deals, members won’t come, and if you don’t have members, deals won’t come. So those were my primary goals, and we made very significant improvements in both areas. We ramped up the number of deals. When I came in, they were having trouble ensuring that members would see at least one interesting new deal per week. When I left, we had four new deals every week, as well as a waiting list. So the deal flow was ramped up. There were a lot of things we implemented that improved deal flow, but the visible result was that there were more than enough really quality deals to keep everyone quite busy and engaged.

…

Roden was managing director of The Angels’ Forum, a leading association of individual and corporate early-stage investors, and was president and CEO of the Silicon Valley Association of Startup Entrepreneurs (SVASE), the largest nonprofit in Northern California dedicated to helping technology entrepreneurs. At both entities, she was responsible for dramatic increases in membership, deal flow, events, volunteers, sponsorship, and service offerings. During this period, she was also a lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the College of Business at San Jose State University (2001–2004). Earlier in her career, Ms. Roden spent a decade in key executive-management roles at several emerging technology companies, including PowerTV (1997–2001) as chief financial officer and vice president of finance and administration; Whalen & Company (1996) as director of operations for the Western Americas; Vicarious, Inc. (1994–1996) as chief financial officer; and US Media Group (1992–1994) as co-founder and principal.

…

There were a lot of things we implemented that improved deal flow, but the visible result was that there were more than enough really quality deals to keep everyone quite busy and engaged. On the membership side, we had a declining number of members when I started—down to the high teens. The goal of the group was twenty-five members, but I rebuilt it to over thirty members with a waiting list. Ghaffari: What did you do that was of significance to enhance the number of deals and the membership? Roden: I would say there were two different things. One was pure process improvement, which kind of goes back to my business school and Touche Ross consulting experience.

Alpha Girls: The Women Upstarts Who Took on Silicon Valley's Male Culture and Made the Deals of a Lifetime

by

Julian Guthrie

Published 15 Nov 2019

The look was terrible for women, but she had a secret source of solace—designer shoes. She loved combing through sales racks at Neiman Marcus for discounted designer heels. She would wear the uniform, but she wouldn’t give up her shoes. Theresia’s job as an associate at Accel was to manage and create “deal flow.” Every day partners forwarded dozens of e-mails to her, most without a single word of explanation. She had to read down the e-mail chain and figure out what was being proposed and whether it was worth a partner’s time. It was a heady blend of triage—where she could not afford to miss something critical—and methodical analysis and research.

…

The door closed, and Theresia took a seat at the back of the room. She had been at Accel for less than six months and was sprinting to land a seat at that white marble table. It wasn’t so different from her teenage days flipping burgers at the back of Burger King and setting her sights on working the cash register. She was doing deal flow triage for the partners, meeting with entrepreneurs offline to learn more, and calling on her contacts at Stanford and from her days at Release Software to see who was doing something interesting. She had zeroed in on cybersecurity as an area of specialty, given what she’d already learned about encryption from her time at Release.

…

They were locked into the lease at the same time that they were laying off staff. And Salesforce, which had come out swinging with some early successes, was now struggling like every other start-up. Magdalena was constantly worried that Salesforce might run out of money. Comfort was nowhere to be found. Federman appreciated Magdalena’s deal flow and her judgment. She was not an ideologue who always had to prevail. She was fact-based, data-driven, and practical. Federman felt confident that she would see the pragmatic, who-is-buttering-your-bread side of the Siebel deal. Magdalena soon realized she would have to compartmentalize her brain.

Den of Thieves

by

James B. Stewart

Published 14 Oct 1991

But in frequent phone calls to Wilkis, Levine did little but complain, especially about his wife. "She's getting in the way of my career," Levine griped. Laurie, wrenched from her comfortable Queens existence, felt isolated in Paris. She was miserable, and ended up in a hospital. Levine wasn't much happier himself. He was frustrated at being out of the "deal flow" in Smith Barney's New York office. Even though, as a junior corporate finance employee, he'd done little there besides spreadsheet analysis, he'd boasted to Wilkis that he knew practically every deal underway in the office. He said he had mastered the ability to read documents on colleagues' desks upside-down.

…

Cecola told Wilkis that he was already at work on a top-secret deal that would be a perfect trading opportunity: Lazard was working for Chicago Pacific Corporation on a bid for Textron, the big conglomerate. Wilkis called Levine that night. He felt he'd proved himself, landing a new recruit with access to a deal flow, just when the loss of Reich threatened the scheme's profitability. Levine was elated, and wasted no time taking advantage of the hot new information about Textron. He bought 51,500 shares; Wilkis bought nearly 30,000. Levine also tried to capitalize on the information to enhance his reputation at Lehman.

…

His bankers often had to scramble to muster enough $100 bills, the currency Levine insisted upon. During 1984 alone, Levine withdrew $200,000 in March, $200,000 in July, and $90,000 in December. He appears to have spent all of it. By the time Levine got the bad news that he was being promoted only to senior vice president, he was already prepared to abandon Shearson Lehman. As the deal flow had steadily increased during the year, other firms were becoming almost desperate for investment bankers with even a modicum of experience in M&A, and Levine's head-hunter at Hadley Lockwood found his once-lackluster resume to be in high demand. Nearly all the top investment banks were at least willing to consider hiring Levine; even Gleacher, now at Morgan Stanley, tried to recruit him.

Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City

by

Brad Feld

Published 8 Oct 2012

Great angel investing organizations exist all over the United States, and around the world, and they have invested in many great companies, as well as helping many angels become better investors. But like so much in a startup community, they are neither necessary nor sufficient. For prospective angel investors who don’t think they have enough deal flow or want someone to help them think through the screening or legal process, an angel investing group can be a good thing. But saying that some angel investors can benefit from being part of organizations doesn’t mean that all will. Communities must feel that their startup community isn’t working if groups of angel investors aren’t meeting every Tuesday night in their city to screen startups.

…

Boulder is home to a small informal angel group, the Boulder Angels. The group was founded in January 2007 by eight investors who were increasingly unsatisfied with the existing, much larger and more organized angel groups in the Boulder-Denver area. The group found the large, formal angel organizations to be expensive and a poor source of deal flow. Boulder Angels was created with two major assumptions in mind. First, we assumed an angel group could be very informal, lightweight, and nimble. We wanted to get moving and start helping the local startup community as fast as possible. We did not consider forming a corporate entity, hiring administrative help, or renting office space.

European Founders at Work

by

Pedro Gairifo Santos

Published 7 Nov 2011

I mean, I agree with you that the venture capital market is extremely different in Europe and in the US. I think that it's about critical mass. Nowadays there are actually quite a lot of venture capitalists even in Europe. But the problem is they are so fragmented on different markets and many European enterpeneurs and investors still don't share the forums. So this makes the deal flow much less open and much less comparable. So, I think that the only place that I found that the words “capital market” truly applied is here in the US. Because here I think it works much more like a market. What I mean by that is that there are buyers and sellers who go to a place and they promote their goods.

…

Farcet: Well, he said, “No, but…” Santos: And how did he pass from the “No, but…”? What did you do then? Farcet: Well, I met the right co-founders. That was Rainmaking. That is a partnership of serial entrepreneurs who built 14 startups in 4 years. They were thinking about how to handle their own deal flow and wanted to extend their brand. We just really hit it off. They had a lot of know-how on legal and financial, and also resources. I had the sweat equity, the drive, and the passion to run an accelarator program (and you have to be a bit crazy to embark on such a journey). So we put it together and we said let's try and do one to see how it goes.

…

Farcet: Well, obviously, for a relatively small amount of money, you get a not insignificant percentage in ten companies that are diversified, highly selected and accelerated. So you spread and lower the risk. We attract really cool projects that you don't have to spend time doing due dilligence for. For that type of early stage investment it's still risky but definitely a safer bet than your own deal flow if you're an angel. Santos: Once the program finishes, how do you provide help to the start-ups? How do the investors keep in touch with the start-ups? Farcet: I keep the investors updated on what's going on with the teams when our they raise money. In terms of helping the teams, we tend to get involved when there are term sheets flying around, if they want our help.

The Smartest Guys in the Room

by

Bethany McLean

Published 25 Nov 2013

One wonders now whether Fastow recognized that he was creating an illusion, especially as the pressure increased, and the sums became larger, and the chicanery required to pull it all off grew more brazen. For the most part, Fastow seemed to exhibit great pride in the work he was doing—he even bragged about some of Enron’s more clever structures. But every once in a while, he would show that he could glimpse a more terrifying reality. Once, a banker asked him what would happen to Enron if the deal flow ever stopped. “It implodes,” Fastow responded. • • • Fastow’s role made him the kind of figure he’d always wanted to be at Enron: truly indispensable. He had never stopped seething over the fact that people in finance weren’t considered as important at Enron as the deal makers or the traders, and part of his motivation was to change that perception.

…

The team was the Holy Trinity of Enron Global Finance: Fastow, Kopper, and Glisan. (Neither Kopper nor Glisan, who later insisted his inclusion in the prospectus was a “mistake,” had requested waivers for their own conflicts.) Just how would their involvement translate into fat returns for investors? They would provide privileged access to Enron’s deal flow (“opportunitities that would not be available otherwise to outside investors”), they’d exploit Enron’s desperation to close deals quickly (LJM2 “will be positioned to capitalize on Enron’s need to rapidly access outside capital”), and they’d bring to the fund their “familiarity with Enron’s assets and their understanding of Enron’s objectives.”

…

“I will always be on the LJM side of the transaction,” he replied. Fastow continued: “Do I know everything that’s going on? Do I have to sign off on every deal that goes in there? Yes.” He would be in the “unique position” of being able to “know everything” about all of Enron’s assets. The sheer volume of Enron deal flow would allow him to cherry-pick great opportunities, Fastow added. (“You’ve got $7 billion in assets coming in every year; that roughly means I’ve got $7 billion in assets coming out the other side.”) And so would Enron’s eagerness to unload assets (“If we want to sell an investment, we want it done by the end of the quarter.”)

Confessions of a Wall Street Analyst: A True Story of Inside Information and Corruption in the Stock Market

by

Daniel Reingold

and

Jennifer Reingold

Published 1 Jan 2006

From Clay’s perspective, research must have seemed like something of a waste of time. It didn’t make any money—and was, in part, paid for by the fees generated by bankers like him. So wasn’t it logical that an analyst, whose salary and bonus inevitably came from the money earned on deals, shouldn’t do anything that could jeopardize that deal flow? Ticked off by Sandy’s conclusions, Clay wrote a memo in September 1990 that shocked all of us on the 20th floor, which was where Morgan Stanley’s research analysts worked. “As we are all too aware,” it said, “there have been too many instances where our Research Analysts have been the source of negative comments about clients of the Firm….

…

Essentially, Wallace was arguing that I was going to torpedo Merrill’s entire investment banking business. The logic went like this: tech was the biggest banking opportunity in the world, and Silicon Valley VCs (venture capitalists) controlled most of the technology IPO candidates. In order to break into this deal flow, Merrill’s relations with the VCs had to get a lot better fast. So if I turned down Pathnet and the venture capitalists took it as a sign that Merrill was too conservative to work with the startup world, Merrill Lynch’s bankers would be screwed. “Sean, I agree that you have a problem,” I said. “But I can’t solve it for you.

…

I didn’t change my mind, so the bankers ultimately had no choice but to tell Pathnet we couldn’t do the deal. The company never did go public. But of course no one could know that at the time. All they knew was that Dan Reingold and Megan Kulick were pain-in-the-ass, stick-in-the-mud analysts who were messing up Merrill’s deal flow in a big way. BY THIS POINT, I had managed to antagonize just about everyone, especially my own bankers and some of the companies I covered. I had hoped that this wouldn’t translate to my buy-side clients, but perhaps somehow it did, as I remained in the number two spot on the I.I. poll for the second year in a row, unable to dislodge Jack from his land of boundless sunshine and everlasting opportunity.

The Dealmaker: Lessons From a Life in Private Equity

by

Guy Hands

Published 4 Nov 2021

Andrew had since run wholesale banking and markets at Lloyds Banking Group and I was convinced he could bring some discipline to Terra Firma’s organisation as well as help the talent we had inside the firm flourish. Andrew made it clear that he had strong views about how he wanted to transform the firm, operationally and structurally. He would manage Terra Firma and take control of the deal flow. Justin, meanwhile, would take control of the portfolio businesses and work out how to get them working better. The two of them would run Terra Firma day-to-day. I would be its most active investor and travelling salesman. Within weeks of the second EMI trial ending in June 2016, we announced Andrew’s appointment.

…

Justin brought in a new management team, led by Roger McLaughlan, a veteran retailer who had most recently been in charge of Toys ‘R’ Us in the UK. Their diagnosis was optimistic. Most of the cost of implementation had already been met, they pointed out. The recent decline could be reversed. To sell the company at this stage would be a mistake. Meanwhile, Andrew was working on deal flow. He had managed to get us into a number of transactions including what was known as Project Ford (a chain of Italian motorway service stations), was bringing in new people and had arranged meetings with investors in Asia and Australia to help raise a new fund. Technically, this should have been Terra Firma Fund IV but since four is a very unlucky number in Chinese and Japanese – in both languages it’s similar to the word for death – we decided to count two other funds we had raised and skip to Terra Firma Fund VI.

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by

William D. Cohan

Published 25 Dec 2015

He charmed his partners--to say nothing of his clients--and rewarded them with a meaningful percentage of the profits when he needed them to execute his prodigious deal flow. At the slightest whiff of resentment, disloyalty, or burnout, Felix would dispatch them to irrelevance and excommunication, in some out-of-the-way hovel, before shining his beacon and affections on the next rising Lazard star. He was immensely feared around the halls of Lazard--just as his mentor, Andre Meyer, had been--but could not even for a moment be ignored, so long as he continued to produce 80 percent of the deal flow and profits. No one at Lazard had anything like Felix's client list, CEO access, or annual revenue production.

…

Morale at the firm, always low, dropped even further. "There are rumors of layoffs but no one has been laid off yet," another banker said. "That creates a level of panic that will not subside until they are made or it is made clear that they will not be made. This is coupled with markedly slower deal flow in M&A from a year ago across the Street. Furthermore, there are rumors that Lazard is being sold.... Right now, there is a level of group panic about something that could be very real and very ugly." Another disgruntled employee confided, "First of all for those support staff who have lost jobs and are supporting families, I am truly sorry.

…

At his memorial service in London, Verey, the former head of Lazard in London, remembered Evans--often described by his colleagues as "Verey's brain"--as a man who had the ability to make everyone feel as if he was your best friend. Michel did not attend the memorial service. Soon thereafter, Bruce held a meeting at Paris's Bristol Hotel for about seventy managing directors to discuss ways to improve cross-border marketing and deal flow. "Historically, people had talked about the business in New York or the business in Paris," Chuck Ward said. "They never really talked about the telecom business or the media business." Now, he said, "we have industry groups really talking to each other on a global basis." After the meeting at the Bristol, Michel invited his partners to his fabulous maison particulier on Rue Saint-Guillaume for dinner, wine, and sumptuous surroundings.

Palace Coup: The Billionaire Brawl Over the Bankrupt Caesars Gaming Empire

by

Sujeet Indap

and

Max Frumes

Published 16 Mar 2021

Marc Rowan and Leon Black made calls to the Oaktree brass. Liang believed that these moments when Apollo went over his head only confirmed the strength of Oaktree’s arguments. Apollo had its cudgels, as well as a gift for preying on the pain points of its adversaries. Apollo ominously reminded them that Oaktree and Canyon depended on deal flow from Apollo that they could be excluded from in the future. On March 3, 2014, Caesars announced the sale of the Four Properties. Additionally, Caesars disclosed that the Total Rewards IP was also leaving OpCo. The junior bonds traded down to twelve cents on the dollar on the news. Vazales and Sheffield crunched the numbers and calculated that the terms of the four casino sales were laughable.

…

Deal lawyers even described what had become the de facto path to partnership at Paul, Weiss: Achieve excellence in two of three areas—public company M&A, private equity transactions, or Apollo work. Apollo was a demanding client. The work had to be done quickly and perfectly. But it was often interesting, highly lucrative work, particularly for a firm that was relatively less prominent in blockbuster deal flow. The downside to this arrangement was now evident. Apollo was an aggressive firm that liked to push the envelope. And with Paul, Weiss’s fortune now so tied to the firm there was the risk that the tail was wagging the dog. Even fans of Karp and Paul, Weiss in the legal community had been shocked at how it appeared Paul, Weiss had sold its soul.

Conspiracy of Fools: A True Story

by

Kurt Eichenwald

Published 14 Mar 2005

Neither told him that the board had just approved one, although it was far smaller than what Timmins had in mind. “Okay, so here’s the idea,” Timmins said. “We raise money for the fund under the Enron name. But we let it become more independent over time. The perception will still be that it has access to Enron deal flow.” In essence, the manager would ultimately run a fund that was separate from Enron but that had the credibility of the company name. Fastow was intrigued. He was already planning another fund something bigger and more lucrative in the future. Maybe Timmins had laid out the perfect structure for it.

…

It would be his way out, his step toward becoming a fund manager full-time. No more begging for bonuses. He would be wealthy. He would be a player in Houston society. Fastow had no doubt: LJM2 would transform his life. “LJM2 will have a lot of unique features,” Fastow said. “It will have access to massive deal flow from Enron. It will, in truth, be a virtual Enron.” It was 9:15 on the morning of September 16. Fastow had traveled to New York to present his big proposal to Enron’s bankers. His first visit was with Chase Capital Partners, an investment arm of Chase Manhattan bank. He had described his vision weeks before to Rick Walker, Chase’s banker in charge of Enron, and had won him over.

…

He would have to move fast. Later that day, Mintz was leaning on his desk, his eyes gliding across the words in the LJM3 offering documents. On page 2, he stopped. That can’t be right. He read the sentence again. Fastow was telling investors that they would profit from his access to proprietary deal-flow data from Enron. In effect, he was putting Enron’s inside information up for sale. Mintz grabbed a copy of the LJM2 memorandum and discovered the same bold claim. Any Enron investors who saw this would go nuts; it was their confidential corporate information that Fastow was selling. Mintz rubbed his face.

King of Capital: The Remarkable Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Steve Schwarzman and Blackstone

by

David Carey

Published 7 Feb 2012

Their M.O. on the M&A front was the same one they had employed at Lehman. The fifty-nine-year-old Peterson, with his entrée to executive suites around the country, would get Blackstone in the door and Schwarzman, then thirty-eight, would make the deals happen. Peterson and Schwarzman would cozy up to management to get “deal flow.” With the financial world polarized by the wave of hostile takeover bids, Peterson and Schwarzman knew that they would have to choose sides. In 1985 the backlash against the raiders and Drexel had not reached its peak, but it was clear to them how they would ally themselves in the battles over corporate control.

…

“It was highly successful quickly, and it showed we weren’t looking to antagonize corporations but to be friends. Corporate partnerships became our calling card.” Whereas competing buyout shops typically exercised dictatorial control over their acquisitions, Blackstone was adaptable. Its openness to splitting power or even taking a back seat to a corporate collaborator bolstered its deal flow, as Schwarzman and Peterson had hoped: Of the dozen investments that Blackstone went on to make with its 1987 buyout fund, seven would be partnerships akin to Transtar. In addition to differentiating Blackstone from the competition, Schwarzman also believed the partnerships heightened Blackstone’s odds of success.

Working the Street: What You Need to Know About Life on Wall Street

by

Erik Banks

Published 7 Feb 2004

CUTTING INTO MUSCLE For all of Wall Street’s market savvy and technical prowess, for all the time and effort it puts into recruiting, training, rotating, and promoting, it 1 1 8 | W o r k i n g th e S tr e e t usually falls short in one key area: figuring out how many employees it needs during bad times. It’s no surprise that when things start looking ugly—markets fall apart, deal flow dries up, clients go on very, very long vacations—a firm’s management pulls out the hatchet and starts swinging, sometimes randomly but always energetically. Heads roll, and it’s not a pretty sight. Just how many swings and how many severed heads depend on the perceived depth of the downturn, but it’s not an exact science.

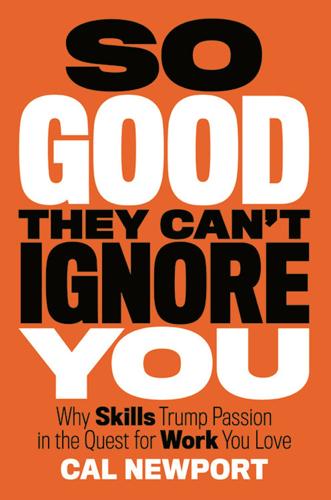

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

by

Cal Newport

Published 17 Sep 2012

Here’s the amount of time he dedicates to each: Mike Jackson’s Work-Hour Allocation Hard-to-Change Commitments Activity Hours Allocated for the Week E-mail 7.5 Lunch/Breaks/Other 4 Planning/Organization 1.5 Partner Meeting/Administrative 4 Weekly Fund-raising Meeting 1 Highly Changeable Commitments Activity Hours Allocated for the Week Improving Fund-raising Materials 3 Fund-raising Process 12 Due Diligence Research 3 Deal Flow Sourcing 3 Meetings/Calls with Potential Investors 1 Work with Portfolio Companies 2 Networking/Professional Development 3 Mike’s goal with his spreadsheet is to become more “intentional” about how his workday unfolds. “The easiest thing to do is to show up to work in the morning and just respond to e-mail the whole day,” he explained.

Statistical Arbitrage: Algorithmic Trading Insights and Techniques

by

Andrew Pole

Published 14 Sep 2007

What is the difference between merger and statistical arbitrage such that massive structural change in the economy—caused by reactions to terrorist attacks, wars, and a series of corporate misdeeds—was accepted as temporarily interrupting the business of one but terminating it (a judgment now known to be wrong) for the other? Immensely important is an understanding of the source of the return generated by the business and the conditions under which that source pertains. The magic words ‘‘deal flow’’ echo in investor heads the moment merger arbitrage is mentioned. A visceral understanding provides a comfortable intellectual hook: When the economy improves (undefined—another internalized ‘‘understanding’’) there will be a resurgence in management interest in risk taking. Mergers and acquisitions will happen.

Getting a Job in Hedge Funds: An Inside Look at How Funds Hire

by

Adam Zoia

and

Aaron Finkel

Published 8 Feb 2008

I had met a lot of nice people there and felt I fit in with the culture of the firm. I chose to join the industrials group, where I thought I would be exposed to not only many different types of companies but also each of the banking products (debt, equity, and M&A). Still, this was 2001 and it was a tough time for deal flow. I was busy during my first year really only pitching deals. It wasn’t until my second year that activity picked up and I managed to close five or six deals. By working closely with my bank’s financial sponsors group, I became involved with several private equity firms advising them on M&A and putting together debt financing packages in support of their buyouts.

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by

Kevin Mellyn

Published 30 Sep 2009

No deals, no fees, no bonus, so the advisor is conflicted between looking out for the client and the need to make deals happen to produce revenue. His or her credibility and usefulness, however, depends on honest, objective advice. Because they are in the markets every day as brokers and dealers, the firms these advisors work in have visibility to something called ‘‘deal flow.’’ They have a pulse on the market, on what things are worth today and likely to be worth tomorrow. INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS As anyone who has been cold called over the phone by a stock broker knows, the whole world of investment banking we have just described is all about selling. Investment banks are always hustling: The brokers and dealers push trades, the advisory folks pitch ideas in the hope they will turn into deals.

Makers

by

Chris Anderson

Published 1 Oct 2012

He can watch the flows of fabrication, the tides of tooling. The Americans sourcing in China and those who are returning to the States. The Germans sourcing in Poland and the French sourcing in, well, anywhere but Germany. It’s a fascinating glimpse into culture, economics, and globalization. Forget the rhetoric—this is the raw deal flow of what companies are actually doing every day. What’s even more interesting than what’s being ordered is who’s doing it. It’s not just big companies ordering custom parts and molds from global machine shops, but little ones, too: bike makers and furniture shops; electrical contractors and toymakers.

Do More Faster: TechStars Lessons to Accelerate Your Startup

by

Brad Feld

and

David Cohen

Published 18 Oct 2010

When I first started angel investing, I quite naturally joined the local angel group in my city. I'd estimate that 95 percent of the members of the group had done at most one angel investment in their entire lives and many had never done any. I quickly figured out that I could generate much more interesting deal flow by getting to know other real angel investors and by creating my own independent brand and visibility. It turns out that strong entrepreneurs are pretty good at finding people who actually make angel investments. And it seems to me that people who don't actually make angel investments, but tell the world they do, aren't really serious about it.

Fed Up!: Success, Excess and Crisis Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Macro Trader

by

Colin Lancaster

Published 3 May 2021

Not just the long hours he needs to work, but the sacrifices he needs to make to his values, his personal code. He needs to change. And who knows if he could handle the additional opportunities that come with that extra dough—not just business opportunities. I’m talking about a different kind of deal flow: blondes, brunettes, redheads, and all the other extras that find their way to you when you succeed. Jerry likes to wear the skinniest of suits, but he’s starting to gain weight due to the long hours. And his name really isn’t Jerry. It’s a nickname from a movie. Then there’s the Rabbi, heavy set with high blood pressure and an ornery edge.

The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

by

Sebastian Mallaby

Published 1 Feb 2022

He had begun his investing career at Accel, where he had absorbed the idea of the “prepared mind,” and he saw that this top-down, anticipatory approach could be especially useful at Sequoia. Because of Sequoia’s status as the Valley’s leading venture firm, most startup founders were eager to pitch to it; by the partnership’s own reckoning, it was invited to consider around two-thirds of the deals that ended up getting funded by the top two dozen venture shops. But this privileged deal flow was both a blessing and a curse. The partners’ days were crammed with meetings organized at the visitors’ request. It was easy to become reactive.[16] To manage this danger, Goetz brought Accel’s prepared-mind approach to Sequoia, leading the partners in mapping out tech trends and anticipating which sorts of startups would prosper from them.

…

One year earlier, Doug Leone had given a talk for entrepreneurs at Nozad’s carpet store and had encouraged Nozad to look out for deals that might be interesting.[37] After that encounter, Nozad had become Sequoia’s ambassador to the Iranian diaspora in the Valley, a group that included Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, and Dara Khosrowshahi, later the boss of Uber.[38] Sequoia valued Nozad’s connections because of its belief in immigrant grit: Moritz, Leone, and Botha were born in Wales, Italy, and South Africa, respectively, and three in five Sequoia-backed successes had at least one immigrant founder.[39] What seemed like serendipity, in other words, was actually the opposite. Nozad was part of Sequoia’s strategy to ensure the best possible deal flow. Three years after Nozad flagged Dropbox, Sequoia’s formal scouts program got off the ground, and stories of this sort became more common. Angel investing, at times a counterweight to the power of VCs, was now transformed into a mechanism that enriched Sequoia’s links to the next generation of founders.

Poorly Made in China: An Insider's Account of the Tactics Behind China's Production Game

by

Paul Midler

Published 18 Mar 2009

The impression that I got at some of the factories that engaged in quality manipulation schemes is that they did so after growing bored with their more conventional successes. There was a great deal of excitement that came with getting a new business off the ground. These manufacturers were thrilled when they signed up their first major customer, and they got another kick from orders that were especially large. When deal flow leveled out, factory owners looked for others ways in which they could capture that hint of thrill. The poverty myth was dispelled at least to some extent by one rather public example. Mattel’s supplier in the lead-paint case was run by an industrialist said to be worth US$1.1 billion. The manufacturer, coincidentally, had a 15-year relationship with the toy giant, which countered another argument made—that these supplier relationships necessarily improved over time and with greater familiarity.

The End of Growth

by

Jeff Rubin

Published 2 Sep 2013

That meant bigger deals and larger profits. The razor-thin margins earned by traditional deposit-taking and commercial banking operations paled in comparison with the spectacular returns notched by the investment banking arm, encouraging CIBC to give more of its balance sheet to the rainmakers from Wood Gundy. By the late 1990s, the deal flow at CIBC shifted into overdrive. Backed by the capital of a major Canadian bank, the scale of deals soon dwarfed anything ever dreamed of at Wood Gundy. CIBC World Markets became the newly minted investment banking arm of CIBC. And for a while all seemed right with the bank’s world. CIBC World Markets was in the top tier of Enron’s banking group, a lucrative spot to be in at the time.

Young Money: Inside the Hidden World of Wall Street's Post-Crash Recruits

by

Kevin Roose

Published 18 Feb 2014

He’d gotten over the disappointment of his meager first-year bonus, and he had consoled himself with the fact that this year’s would probably be much better. The year 2011 was shaping up to be a good one in the markets—not nearly as good as the pre-crisis days, but the best J. P. had experienced since he was hired. Already, there was talk of increased deal flow, and of promoting a few of the third-year analysts to associate during the next bonus cycle. But when he turned on his BlackBerry after a week of inactivity, J. P. got a startle. Among the hundreds of e-mails waiting for him upon his return was a farewell e-mail from an analyst in his class, a kid named Terrance Hawk.

Lurking: How a Person Became a User

by

Joanne McNeil

Published 25 Feb 2020

Annie Karni’s Politico story “In Jared Kushner, Trump Finds a Kindred Spirit” (November 18, 2016) details, “At The New York Observer, which he bought when he was 25, Kushner pushed for the newspaper to launch a standalone website called ‘Socialite Slapdown.’ It was fully his idea: to rate Manhattan’s 64 reigning socialites by ‘birth, brains, beauty and brio’ to see ‘who comes out on top.’” See also reports about Jeff Bezos’s “women flow,” which wasn’t an actual app but an approach to dating inspired by “deal flow” on Wall Street. The updates on Myspace Tom drew from Business Insider (Nicholas Carlson, “Myspace Tom: I Am ‘The Guy Who Sold Myspace for $580 Million While You Slave Away Hoping for a Half-Day Off,’” December 20, 2012). Kyunchi’s “Myspace is the new Woodstock” comment comes from a Paper magazine interview (Katherine Gillespie, “Kyunchi Is Making MySpace Music for 2019,” January 28, 2019).

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by

Philip Augar

Published 20 Apr 2005

For example, in global currency dealing the biggest player, UBS, recently had a market share more than double that of Goldman Sachs, the highest placed investment bank in sixth place;18 and in credit derivatives, a vast and rapidly growing area that involves repackaging and swapping corporate debt, the big financial conglomerates are the market leaders. However, as we have already seen, corporate advisory work and underwriting are the key investment banking products in terms of deal flow and prestige. These remain dominated by the top investment banks. With at least a dozen global investment banks theoretically able to carry out most transactions, the customer clearly has plenty of choice. Yet when it comes to exercising that choice there has been an increasing tendency for customers to go with the leading players.

When the Wolves Bite: Two Billionaires, One Company, and an Epic Wall Street Battle

by

Scott Wapner

Published 23 Apr 2018

Shares quickly popped 15 percent on the news—a sign that, at least at face value, many on Wall Street liked the deal.20 After the transaction was announced, Pearson addressed the company’s critics in an interview with CNBC’s mergers and acquisitions expert David Faber, who asked Pearson point-blank whether the market was forcing him to keep the deal flow going, irrespective of whether it made good business sense. “That’s my job,” Pearson scoffed. “It’s our board’s job to do whatever we can to create value for shareholders.”21 Ackman was so smitten with Pearson’s game plan that he even compared Valeant to Warren Buffett’s hallowed Berkshire Hathaway and its own platform strategy of scooping up businesses and seamlessly adding them into the fold.

Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers

by

Timothy Ferriss

Published 6 Dec 2016

Party rounds often lead to poor due diligence and few people with enough skin in the game to really care. Checking these boxes allowed me to add a lot of value quickly, even as relatively cheap labor (i.e., I took a tiny stake in the company). My ability to help spread via word of mouth, and I got what I wanted: great “deal flow.” Deals started flowing in en masse from other founders and investors. Fast forward to 2015, and great deal flow was paralyzing the rest of my life. I was drowning in inbound. Instead of making great things possible in my life, it was preventing great things from happening. I’m excited to go back to basics, and this requires cauterizing blessings that have become burdens.

Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism

by

Robin Chase

Published 14 May 2015

At Prosper, more than 80 percent of the loans made in March 2014 were financed by hedge funds, pension funds, asset managers, sovereign wealth funds, and foreign banks.11 And at Lending Club, that number—the percentage of loans fulfilled by institutional lenders—was about 70 percent.12 In October 2014, institutional investors issued $177 million in loans, three-and-a-half times more than they had in October 2013.13 Larry Summers, secretary of the treasury during the Clinton administration and now a Lending Club board member, said, “Lending Club’s platform has the potential to profoundly transform traditional banking over the next decade.”14 The question is, transform it into what? A different cover on the same deal flow? Or a totally different group of lenders? In some city markets, Airbnb has seen the same takeover: professionals using the platform to market their apartments, condos, and houses. In early 2014, after a battle of several months, the New York State attorney general received data on New York rentals from Airbnb for the period from January 1, 2010, through June 2, 2014.

The Revolution That Wasn't: GameStop, Reddit, and the Fleecing of Small Investors

by

Spencer Jakab

Published 1 Feb 2022

An April 2021 study by Futu, a Chinese brokerage firm with a US subsidiary, found that members of Generation Z opened their trading app 8.2 times a day and traded 147 times a year on average.[3] Where do the forgone gains of frequent traders go? Not money heaven. Some accrue to people in the market who are preternaturally patient—the Warren Buffetts of the world. He has earned 120 times the market’s return since 1965. And a good deal flows to people who are the opposite of patient but happen to be pretty good at capturing short-term profits in the market from amateurs. High-frequency traders don’t care about how a company is doing or what is happening with the economy. They profit by programming their computers to find a small inefficiency and then get in and out faster than a human possibly can, earning as little as fractions of a penny.

Too big to fail: the inside story of how Wall Street and Washington fought to save the financial system from crisis--and themselves

by

Andrew Ross Sorkin

Published 15 Oct 2009

By his estimation AIG had only about a week to find a solution, or it, too, could falter. Of the handful of principals involved in the dialogue about the enveloping crisis—the government included—Dimon was in an especially unusual position. He had the closest thing to perfect, real-time information. That “deal flow” enabled him to identify the fraying threads in the fabric of the financial system, even in the safety nets that others assumed would save the day. Dimon began contemplating a worst-case scenario, and at 7:30 a.m. he went into his home library and dialed into a conference call with two dozen members of his management team.

…

It was in the resulting battle that Paulson came to dislike Grasso’s cronies, who seemed all too ready to throw Paulson under a bus if it suited their purposes. But as secretary of the Treasury, he was obliged to be a diplomat, and as such, needed to maintain good relationships with all the Wall Street CEOs. They would be huge assets, his eyes and ears on the markets. If he needed “deal flow,” he preferred to get it directly from them, and not from some unconnected Treasury lifer whose job it was to figure these things out. About a month after he settled into the job, in the summer of 2006, Paulson called Fuld, whom he reached playing golf with a friend in Sun Valley, where he had a home.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by

Nate Silver

Published 12 Aug 2024

The sharpest sports bettors I’ve met aren’t necessarily super extroverted, but they aren’t lone wolves, either—they’re the kind of guys who know a lot of guys. They usually delegate their work and need networks of people to provide them with models and information. It also helps to have an ear to the ground to sniff out potential opportunities—the sports-betting equivalent of what venture capitalists call “deal flow.” And since they inevitably face severe limits from sportsbooks, they’ll also need people to assist them in placing bets. If I were to develop a series of sports-betting action figures, you’d already have collected two of them and their respective superpowers: Spanky Kyrollos (the Better Bettor)[*14] and Rufus Peabody (the Modeler).

…

Furthermore, they syndicate into each other’s deals, Series A, Series B, Series C.” There’s also one particular characteristic of Silicon Valley that especially encourages groupthink—you can’t go short. “It’s not a public market, you can’t short the stock. And because you’re syndicating and you want deal flow, you can’t even speak short, you can’t say negative things about other people’s deals.”[*24] Yet for all its Mean Girls conformity—Rabois trying to figure out what his five best frenemies will think—Silicon Valley’s opinions are still relatively uncorrelated with those of the outside world, Mallaby thinks.

Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Gobal Crisis

by

James Rickards

Published 10 Nov 2011

Low rates also set off a search for yield by institutional investors who needed higher returns than were being offered in risk-free government securities or highly rated bonds. The subprime residential loan market and the commercial real estate market both exploded in terms of loan originations, deal flow, securitizations and underlying asset prices due to Greenspan’s low rate policies. The great real estate bubble of 2002 to 2007 was under way. In September 2002, just as the low rate policy was taking off, Greenspan gained an ally, Ben Bernanke, appointed as a new member of the Fed Board of Governors.

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by

Peter H. Diamandis

and

Steven Kotler

Published 3 Feb 2015

Operational assets, meanwhile, are those things required for business to run effectively. For example, if you are running a software business, these assets include the algorithms powering your software, your database architecture and server implementation, technical designs, models, and frameworks that organize deal flow and customer acquisition strategies, and so on. A number of companies allow you to crowdsource the creation of operational assets. In fact, doing so is one of the keys to becoming a data-driven, exponential organization. A great example of this is TopCoder (www.topcoder.com). You’ve probably heard about hackathons—those mysterious tournaments where coders compete to see who can hack together the best piece of software in a weekend.

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by

Rana Foroohar

Published 5 Nov 2019

I remember coming into work day after day and feeling that people were just pretending to be busy, researching fruitless ideas in the open-plan spaces that I will forever believe are actually counterproductive to getting real work done (who can think with people constantly talking around them?). Although the founders kept a deal flow going and the press kept writing naïvely positive stories about London’s homegrown tech incubator,9 internally, the firm was already starting to revert to what it really was—a collection of ex–City bankers looking to make a quick buck. When you pull back the lens, that’s really what much of the late ’90s/early 2000s dot-com boom was all about.

The Accidental Investment Banker: Inside the Decade That Transformed Wall Street

by

Jonathan A. Knee

Published 31 Jul 2006

These firms are deal machines: all they do is buy, sell, and finance, all of which are the core fee generators of the investment banking business. Understandably, keeping financial sponsors happy is a very high priority. Financial sponsors view many of the services investment bankers provide as commodities. What they constantly demand and need to survive is deal flow—access to transactions that can allow them to put their capital to use. As a result, bankers whose job is to manage relationships with financial sponsors comb their firms looking for deals that can be shown to their clients—then actively encourage merger bankers to coax their selling clients to offer the potential deal to the broadest possible universe.

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon

by

Brad Stone

Published 14 Oct 2013

Bezos thought analytically about everything, including social situations. Single at the time, he started taking ballroom-dance classes, calculating that it would increase his exposure to what he called n+ women. He later famously admitted to thinking about how to increase his “women flow,”2 a Wall Street corollary to deal flow, the number of new opportunities a banker can access. Jeff Holden, who worked for Bezos first at D. E. Shaw & Co. and later at Amazon, says he was “the most introspective guy I ever met. He was very methodical about everything in his life.” D. E. Shaw had none of the gratuitous formalities of other Wall Street firms; in outward temperament, at least, it was closer to a Silicon Valley startup.

eBoys

by

Randall E. Stross

Published 30 Oct 2008

Greenberg called him up to see whether he liked his new life at Benchmark. Beirne said yes, and you’ve got to meet my partners. Before he knew it, Greenberg was invited to become an entrepreneur in residence at Benchmark. EIRs, as they were known, were funded by many of the leading venture firms in the Valley as a source of “deal flow”; by having EIRs tinker with a new business plan while under the same roof, the firm gets the first peek; if it likes what it sees, it also is in the best position to be the earliest investor. At any given time, Benchmark hosted one or two EIRs, who usually stayed four to six months. One of Greenberg’s dearly learned tenets drawn from his earlier experience was that it was best to have many venture firms bidding against one another.

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by

Nicholas Lemann

Published 9 Sep 2019

Just before LinkedIn went public, Hoffman joined Greylock, one of the top-tier venture capital firms on Sand Hill Road, as a partner. He began spending part of every week at Greylock and part at LinkedIn, where he worked in an office next to Jeff Weiner’s. This put him more formally in the position he’d been in informally for years, with as much access to deal flow, the lifeblood of Silicon Valley, as anybody. As he casually remarked to a visitor once, “If there’s anything in the Valley, I’m going to know about it.” Greylock played host to an endless procession of people who wanted funding for start-ups, almost all of them young men in jeans and T-shirts.

Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment

by

David F. Swensen

Published 8 Aug 2005

Franchise Firms Atop the hierarchy of venture capital partnerships stand a relatively small number of venture firms that occupy an extraordinary position. This group of eight or ten firms enjoys a substantial edge over less exalted practitioners. Top-tier venture capitalists benefit from extraordinary deal flow, a stronger negotiating position, and superior access to capital markets. In short, participants in the venture capital process, from the entrepreneur to the investment banker, prefer dealing with this small set of “franchise firms.” In no other area of the capital markets does the identity of the source of funds matter in the way that it does in the venture capital world.

How to Build a Billion Dollar App: Discover the Secrets of the Most Successful Entrepreneurs of Our Time

by

George Berkowski

Published 3 Sep 2014

Venture capitalists can be harsh and unforgiving: some will dismiss you outright; others will feign interest with the goal of investing later. One of the first things you should do at this point is figure out which VCs do invest early in Series A funding rounds. A lot of VCs will take meetings and talk with you at any stage to ensure they are building their deal-flow pipeline (and make sure they are building up valuable information about what startups like yours are doing). But be careful, and identify investors with a strong history of investing early so that you don’t spend too much time pitching to investors who won’t actually be useful at this point. In the best possible scenario, the process of securing a Series A investment, from the initial meeting to cold hard cash in the bank, is about two months.

Inner Entrepreneur: A Proven Path to Profit and Peace

by

Grant Sabatier

Published 10 Mar 2025

However, I don’t recommend buying physical businesses through websites, as brokers often list them only as a last resort when they can’t sell them through their networks. It will be harder to find a good deal. It’s better to establish relationships with brokers who can provide you with a constant stream of new deals, also known as “deal flow.” But these websites are great for learning, and you can get a good sense of the economics of many types of businesses. Then, you can watch a few YouTube videos to identify the risks and challenges of these business models more specifically. Just yesterday, I watched a video on the pros and cons of buying a FedEx delivery route and quickly determined it was not a great business, as prices are set by corporate, and contract delivery labor is hard to manage.

What Should I Do With My Life?

by

Po Bronson

Published 2 Jan 2001