discovery of the americas

description: the exploration and subsequent colonization of the Americas by European powers, starting with Christopher Columbus in 1492

47 results

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

James Robinson

Published 20 Mar 2012

In much of Africa the substantial profits to be had from slaving led not only to its intensification and even more insecure property rights for the people but also to intense warfare and the destruction of many existing institutions; within a few centuries, any process of state centralization was totally reversed, and many of the African states had largely collapsed. Though some new, and sometimes powerful, states did form to exploit the slave trade, they were based on warfare and plunder. The critical juncture of the discovery of the Americas may have helped England develop inclusive institutions but it made institutions in Africa even more extractive. Though the slave trade mostly ended after 1807, subsequent European colonialism not only threw into reverse nascent economic modernization in parts of southern and western Africa but also cut off any possibility of indigenous institutional reform.

…

Despite such an inauspicious history, it was in England that the first truly inclusive society emerged and where the Industrial Revolution got under way. We argued earlier (this page–this page) that this was the result of a series of interactions between small institutional differences and critical junctures—for example, the Black Death and the discovery of the Americas. English divergence had historical roots, but the view from Vindolanda suggests that these roots were not that deep and certainly not historically predetermined. They were not planted in the Neolithic Revolution, or even during the centuries of Roman hegemony. By AD 450, at the start of what historians used to call the Dark Ages, England had slipped back into poverty and political chaos.

…

After the seventh century, Ethiopia remained isolated in the mountains of East Africa from the processes that subsequently influenced the institutional path of Europe, such as the emergence of independent cities, the nascent constraints on monarchs and the expansion of Atlantic trade after the discovery of the Americas. In consequence, its version of absolutist institutions remained largely unchallenged. The African continent would later interact in a very different capacity with Europe and Asia. East Africa became a major supplier of slaves to the Arab world, and West and Central Africa would be drawn into the world economy during the European expansion associated with the Atlantic trade as suppliers of slaves.

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World

by

Peter Frankopan

Published 26 Aug 2015

For one Spanish chronicler, this was nothing less than ‘the greatest event since the Creation – other than the incarnation and the death of the one who created it’.64 For another, it was clearly God himself who had revealed ‘the provinces of Peru, from which such a great treasure of gold and silver had been concealed’; future generations, opined Pedro Mexía, would not believe the quantities that had been found.65 The discovery of the Americas was soon followed by the import of slaves, bought in the markets of Portugal. As the Portuguese knew from their experiences in the Atlantic island groups and West Africa, European settlement was expensive, was not always economically rewarding and was easier said than done: persuading families to leave their loved ones behind was hard enough, but high death rates and testing local conditions made this even more difficult.

…

This was glossed over as artists, writers and architects went to work, borrowing themes, ideas and texts from antiquity to provide a narrative that chose selectively from the past to create a story which over time became not only increasingly plausible but standard. So although scholars have long called this period the Renaissance, this was no rebirth. Rather, it was a Naissance – a birth. For the first time in history, Europe lay at the heart of the world. 12 The Road of Silver Even before the discovery of the Americas, trading patterns had begun to pick up after the economic shocks of the fifteenth century. Some scholars argue that this was caused by improved access to gold markets in West Africa, combined with rising output in mines in the Balkans and elsewhere in Europe, perhaps made possible by technological advances that helped unlock new supplies of precious metals.

…

To cover the shortfalls in agricultural production and to pay for weapons and munitions, the Allies took on huge commitments, commissioning institutions such as J. P. Morgan & Co. to ensure a constant supply of goods and materials.122 The supply of credit resulted in a redistribution of wealth every bit as dramatic as that which followed the discovery of the Americas four centuries earlier: money flowed out of Europe to the United States in a flood of bullion and promissory notes. The war bankrupted the Old World and enriched the New. The attempt to recoup losses from Germany (set at an eye-watering and impossibly high level equivalent to hundreds of billions of dollars at today’s prices) was a desperate and futile attempt to prevent the inevitable: the Great War saw the treasuries of the participants ransacked as they tried to destroy each other, destroying themselves in the process.123 As the two bullets left the chamber of Princip’s Browning revolver, Europe was a continent of empires.

Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen

by

James Suzman

Published 10 Jul 2017

Their voyages were, after all, instrumental in reshaping the world. In tandem with Christopher Columbus’s accidental discovery of the Americas, da Gama’s voyage to the Indies would later be hailed as the “big bang” of economic globalization—the moment that catalyzed the transformation of the world from a series of often discrete economic communities into a single complex and multifaceted economic system. Articulating a view that would later be reaffirmed by many others, Adam Smith, the “father of economics,” declared da Gama’s voyage and Columbus’s “discovery” of the Americas to be “the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind.”2 Whether this particular moment was more important than any others in the emergence of a globalized economy is debatable.

Origins: How Earth's History Shaped Human History

by

Lewis Dartnell

Published 13 May 2019

† India’s black peppercorns are botanically very different from bell (sweet) peppers and chilli peppers, which are both fruits of Capsicum plants native to Central and South America. These New World species were unknown to the rest of the world until the great fifteenth-century transfer of domesticated plants and animals that occurred after the European discovery of the Americas, known as the Columbian Exchange. ‡ So much so that in the late seventeenth century, after the Second Anglo-Dutch War, it was agreed that the Dutch claim over Manhattan be ceded to the English in exchange for the spice island of Run, one of the smallest Banda islands. Run is just 3.5 kilometres long, but its acquisition allowed the Dutch to secure their nutmeg trading monopoly in the East Indies.

…

It began to dawn on Europeans that perhaps the lands to the west were all one continuous coastline, that they had stumbled across not a series of new islands, but an entire continent–a whole New World. THE GLOBAL WIND MACHINE The Portuguese had spent the best part of a century inching their way down the coast of Africa before they finally found its southern tip and the gateway into the Indian Ocean. Now, within a generation of the discovery of the Americas in 1492, European sailors ventured across all the world’s oceans and completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth. This was a revolution that heralded the birth of today’s global economy. All this was only possible because mariners had come to understand the patterns of reliable winds and currents around the globe, which now determined the trade routes that brought great riches to Europe.

Surviving AI: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence

by

Calum Chace

Published 28 Jul 2015

Getting its retaliation in first A superintelligence with access to Wikipedia will not fail to realise that humans do not always play nicely together. Throughout history, meetings between two civilisations have usually ended badly for the one with the less well-developed technology. The discovery of the Americas by Europeans was an unmitigated disaster for the indigenous peoples of North and South America, and similarly tragic stories played out across much of Africa and Australasia. This is not the result of some uniquely pernicious characteristic of European or Western culture: the Central and South American empires brought down by the Spaniards had themselves been built with bloody wars of conquest.

Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension

by

Samuel Arbesman

Published 18 Jul 2016

With a cabinet of curiosities, you could take in the entirety of the universe and all its complications at a glance. But not only did some of these cabinets appear to be little more than a miscellaneous hodgepodge; it was soon realized that they could never be big enough. Ball quotes a point made by the writer Patrick Mauries: that after the discovery of the Americas there was too much diversity to be contained within a single collection. The world was beginning to be recognized as too various and complex. Now, choices had to be made: What should make it into these rooms, and what could be ignored? Cabinets of curiosities persisted for a long time, in their own way.

Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies

by

Jared M. Diamond

Published 15 Jul 2005

Tensions among the groups that Achmad, Wiwor, Sauakari, and Ping Wah represent dominate the politics of Indonesia, the world's fourth-most- populous nation. These modern tensions have roots going back thousands of years. When we think of major overseas population movements, we tend to focus on those since Columbus's discovery of the Americas, and on the resulting replacements of non-Europeans by Europeans within historic times. But there were also big overseas movements long before Columbus, and prehistoric replacements of non-European peoples by other non-Euro- pean peoples. Wiwor, Achmad, and Sauakari represent three prehistorical waves of people that moved overseas from the Asian mainland into the Pacific.

…

Let us now return to that collision of hemispheres, applying what we have learned since Chapter 3. The basic question to be answered is: why did Europeans reach and conquer the lands of Native Americans, instead of vice versa? Our starting point will be a comparison of Eurasian and Native American societies as of A.D. 1492, the year of Columbus's “discovery” of the Americas. OUR COMP ARISON BEGINS with food production, a major determi- nant of local population size and societal complexityhence an ultimate factor behind the conquest. The most glaring difference between American and Eurasian food production involved big domestic mammal species. In Chapter 9 we encountered Eurasia's 13 species, which became its chief source of animal protein (meat and milk), wool, and hides, its main mode of land transport of people and goods, its indispensable vehicles of war- fare, and (by drawing plows and providing manure) a big enhancer of crop production.

A Short History of Humanity: How Migration Made Us Who We Are

by

Johannes Krause

and

Thomas Trappe

Published 8 Apr 2021

When exactly it arrived in Europe is unclear, but there’s plenty of evidence to suggest the disease was around during the Middle Ages. Numerous skeletons dating from the period before 1493—in Great Britain, for instance—show clear signs of syphilis. Until now, these finds have usually been taken as evidence that the disease existed in Europe before the discovery of the Americas, but I am almost certain that the dead people in question suffered from yaws. AN UNDERESTIMATED THREAT * * * FOR MOST PEOPLE IN THE MODERN WEST, PLAGUE, leprosy, paratyphoid, tuberculosis, and syphilis are little more than ancient ghosts. Bacterial infections such as these are no longer viewed as potentially fatal, having been largely replaced in the public consciousness by appalling viral pandemics.

Fall of Civilizations: Stories of Greatness and Decline

by

Paul Cooper

Published 31 Mar 2024

The Fall of Byzantium disrupted long-established trade routes that joined Europe to Asia along the Silk Road, forcing European traders to search for new routes to the markets of the East, and develop maritime technologies. Within forty years of the siege of Constantinople, European explorers rounded the southernmost cape of Africa, opening up the sea route to India, and just a few years later their desire to find a western route to Asia would lead to the discovery of the Americas. Christopher Colombus had been inspired to undertake his voyage in part because of the ancient Greek text known as the Geographia, written by the philosopher Claudius Ptolemy, which had been preserved in the libraries of Byzantium and brought to Western Europe after its fall. Byzantium would also continue to welcome the tired and huddled masses of the world to shelter behind its walls.

…

Some were forced to work as labourers and domestic servants, others to fight as soldiers in medieval armies. Slavery was a cruel fact of life at this time — but the resource that truly defined West Africa’s trade at this time was not people, or even ivory or spices, but gold. West Africa is remarkably rich in this rare metal, and until the discovery of the Americas in the sixteenth century was the world’s top producer. So much gold left this region during the Middle Ages that Europeans and Arabs believed that it must be home to a single monumental mine, a mountain of gold that was being kept a secret by African kings — perhaps even the legendary mines of King Solomon.

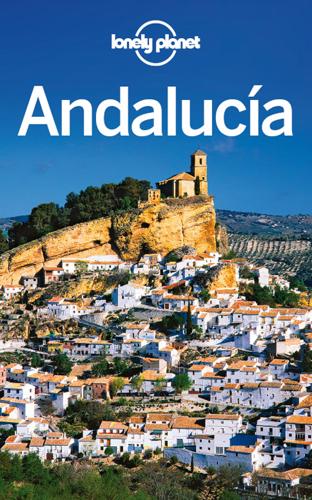

Lonely Planet Andalucia: Chapter From Spain Travel Guide

by

Lonely Planet

Published 31 May 2012

But as Almohad power dwindled after the disastrous defeat of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, Castile’s Fernando III (El Santo; the Saint) went on to capture Seville in 1248. Fernando brought 24,000 settlers to Seville and by the 14th century it was the most important Castilian city. Seville’s biggest break was Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492. In 1503 the city was awarded an official monopoly on Spanish trade with the new-found continent. It rapidly became one of the biggest, richest and most cosmopolitan cities on earth. But it was not to last. A plague in 1649 caused the death of half the city’s population, and as the 17th century wore on, the Río Guadalquivir became more silted and less navigable.

…

The room off its northern end has an international collection of beautiful, elaborate fans. The Sala de Audiencias (Audience Hall) is hung with tapestry representations of the shields of Spanish admirals and Alejo Fernández’ 1530s painting Virgen de los Mareantes (Virgin of the Sailors), the earliest known painting about the discovery of the Americas. Cuarto Real Alto The Alcázar is still a royal palace. In 1995 it staged the wedding feast of Infanta Elena, daughter of King Juan Carlos I, after her marriage in Seville’s cathedral. The Cuarto Real Alto (Upper Royal Quarters), the rooms used by the Spanish royal family on their visits to Seville, are open for (heavily subscribed) tours several times a day, some in Spanish, some in English.

Does Capitalism Have a Future?

by

Immanuel Wallerstein

,

Randall Collins

,

Michael Mann

,

Georgi Derluguian

,

Craig Calhoun

,

Stephen Hoye

and

Audible Studios

Published 15 Nov 2013

If we polled the contemporary political experts regarding the direction of their world, they would concur above all on the spectacular emergence of new empires across the vast landmass between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. These imagined experts might hardly mention the Protestant Reformation in the far northwestern extension of Eurasia, perhaps not even the recent discovery of the Americas. Ming China was surely the world’s manufacturing and demographic giant. Shortly after 1500 the Mughals imposed their imperial rule in the inherently fractitious India. At the very same time the Safavis were ascendant in Iran, the Ottoman Turks forcefully reclaimed the legacy of the Eastern Roman Empire, while the Spanish Hapsburgs appeared on their way to establishing a Catholic empire in the West.

Ambition, a History

by

William Casey King

Published 14 Sep 2013

A popular saying from the time captures the spirit: “Tres maneras para medrar, iglesia, casa real o mar.”70 In other words, there were three methods for gaining preferment or rank: the church, the royal house, or the sea.71 The sea, and America, Asia, and Africa, the overseas discoveries of Spain and Portugal, represented a substantial opportunity for individuals to garner rank and preferment from a crown that required administration and colonization of newly discovered lands. The religious imperative, saving souls, the conversion of others to Christianity, conflated with conquest and discovery, as personal achievement, ambition, became a means by which God and nation could likewise be elevated. The overseas discovery of the Americas coincided with the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula and the expulsion of the Jews and Moors, lending a swagger of divine favor to the Catholic king and queen of Castile and Aragon bent on the delusion of purity of Spain and its purpose.72 It is in this context that Columbus sailed. In his Diario he reflected the dominant spirit of national, Christian, and individual ambition.73 At the time, his journal was intended not only for the king and queen but was written with the expectation of its importance.

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by

John Plender

Published 27 Jul 2015

Yet even Sir Isaac Newton, father of modern physical science, devoted much of his career to alchemical research. Few were more immoderate in their blindness than sixteenth-century European adventurers, whom John Maynard Keynes regarded as the originators of capitalism. We owe the Europeans’ discovery of the Americas to gold, for gold was the probable motive that drove Christopher Columbus westward: his diary of a voyage that lasted less than a hundred days mentions gold sixty-five times. The Spanish conquistadores who followed – Cortés, Pizarro and their men – were not only brutal and rapacious in their imperialist incursions into Mexico and Peru; by bringing European diseases to the Americas, they also inadvertently wiped out much of the population of the areas they colonised.

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 10 Apr 2016

I shall argue that the modern historical era, the past five hundred years, is characterized by Kuznets waves of alternating increases and decreases in inequality. Before the Industrial Revolution, when mean income was stagnant, there was no relationship between mean income level and the level of inequality. Wages and inequality were driven up or down by idiosyncratic events such as epidemics, new discoveries (of the Americas or of new trade routes between Europe and Asia), invasions, and wars. If inequality decreased as mean income and wages went up and the poor became slightly better off, Malthusian checks would be triggered: the population would increase to unsustainable levels and would ultimately be driven down (as the average per capita income declined) by higher mortality rates among the poor.

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

James A. Robinson

Published 23 Sep 2019

The conditions for the Industrial Revolution were prepared by the progress of British society in the corridor. After the end of the Middle Ages the center of gravity of economic activity in Europe had started moving north toward the Netherlands and England. This was intimately connected with the discovery of the Americas and the impact of the new economic opportunities this created on the race between state and society. Countries that were better poised to take advantage of these opportunities in ways that strengthened state and society were able to move ahead institutionally and then economically. In England, the existing balance of power favored society so that the Tudor state in the sixteenth century was unable to exert monopoly control over access to trade.

…

So while England, France, and the Netherlands moved up in the corridor, Poland, Hungary, and other parts of Eastern Europe launched deeper into the lands of the Despotic Leviathan. Potentially divergent influences on a nation’s political development come not only from military threats or demographic shocks but also from major economic opportunities. Such a change reconfiguring European trajectories arrived with the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus and the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by Bartolomeu Dias. Once again, the different balances between state and society produced divergent responses. In England, as we mentioned in Chapter 6, the tight limits on what the crown and its allies could do in terms of monopolizing overseas trade meant that it was new groups of merchants that benefited most from these economic opportunities.

Your Own Allotment : How to Find It, Cultivate It, and Enjoy Growing Your Own Food

by

Russell-Jones, Neil.

Published 21 Mar 2008

Zanzibar is a well-known producer of spices. I have been there and visited a spice farm, which was fascinating. The spice trade made many people very rich as people sought spices to improve the flavour of food, and also to help to preserve it. The expeditions to the west that resulted in the discovery of the Americas were attempts to find a route to the spice islands of Africa and the East Indies that would break the monopoly of the Arab traders. Popular herbs Below are some of the more popular herbs grown in gardens and allotments. Basil (ocimum basilicum) Basil likes the Mediterranean warmth of its original climate and thrives in a greenhouse or outside as an annual in sunny spots in UK gardens.

Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future

by

Paul Mason

Published 29 Jul 2015

But the most spectacular thing is what happens to the bottom line – the developing world. It grows by 404 per cent after 1989. It is this that prompted the British economist Douglas McWilliams, in his Gresham lectures, to nominate the last twenty-five years as the ‘greatest economic event in human history’. World GDP rose by 33 per cent in the 100 years after the discovery of the Americas, and GDP per person by 5 per cent. In the fifty years after 1820, with the Industrial Revolution underway in Europe and the Americas only, world GDP grew by 60 per cent, and GDP per person by 30 per cent. But between 1989 and 2012 world GDP grew from $20 trillion to $71 trillion – 272 per cent – and, as we’ve seen, GDP per person increased by 162 per cent.

Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart

by

Tim Butcher

Published 2 Jul 2007

The Congo's output of the occasional shipment of ivory or raffia could not compete with the huge volume of silks and spices available in Asia and, in the face of commercial competition, the Portuguese soon found another asset they could take from the Congo - slaves. Slavery was a long-established practice among African tribes. Any raiding party that successfully attacked a neighbour would expect to return with slaves. But what made the Portuguese demand for slaves different was its scale. The simultaneous discovery of the Americas by European explorers created an apparently limitless demand for labour to work on the plantations of the New World, and in Europe's African toeholds slavery was turned overnight from a cottage industry into a major, global concern. The effect on the Congo was devastating. The plunder of people started out on a small scale in the early 1500s, with Portuguese traders paying Congolese warriors for the occasional slave they brought back with them from raids.

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 26 May 2014

Why it started there – rather than, say, China or India, which had been comparable to Western Europe in their levels of economic development until then – is a subject of intense and long-running debate. Everything from the Chinese elite’s disdain for practical pursuits (like commerce and industry), the discovery of the Americas and the pattern of Britain’s coal deposits has been identified as the explanation. This debate need not detain us here. The fact is that capitalism developed first in Western Europe. Before the rise of capitalism, the Western European societies, like all the other pre-capitalist societies, changed very slowly.

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 23 Sep 2019

Some Methodological Issues and Definitions Notes References Acknowledgments Index CHAPTER 1 THE CONTOURS OF THE POST–COLD WAR WORLD [The bourgeoisie] compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image. —Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848) At the particular time when these discoveries [of the Americas and the East Indies] were made, the superiority of force happened to be so great on the side of the Europeans that they were enabled to commit with impunity every sort of injustice in those remote countries. Hereafter, perhaps, the natives of those countries may grow stronger, or those of Europe may grow weaker, and the inhabitants of all the different quarters of the world may arrive at that equality of courage and force which, by inspiring mutual fear, can alone overawe the injustice of independent nations into some sort of respect for the rights of one another.

Lonely Planet Best of Spain

by

Lonely Planet

Published 1 Nov 2016

But Almohad power dwindled after the disastrous defeat of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, and Castilla’s Fernando III (El Santo; the Saint) went on to capture Seville in 1248. Fernando brought 24,000 settlers to Seville and by the 14th century it was the most important Castilian city. Seville’s biggest break was Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492. In 1503 the city was awarded an official monopoly on Spanish trade with the new-found continent. It rapidly became one of the biggest, richest and most cosmopolitan cities on earth. 1 El Arenal & Triana Colonising caballeros made rich on New World gold once stalked the streets of El Arenal on the banks of the Río Guadalquivir, watched over by Spanish galleons offloading their American booty.

The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism

by

Nick Couldry

and

Ulises A. Mejias

Published 19 Aug 2019

Because the language is so incomprehensible, most users simply scroll to the bottom of the document and click the “I agree” button without so much as a quick glance.30 “Exploration” and territorial annexation in historical colonialism were enacted by advances in the technologies of transportation and the sciences of management. Following the “discovery” of the Americas, a global network for the flow of goods and information began to take shape, a network whose infrastructure continues to be visible today and whose development was part and parcel of the growth of Western science and technology. Francis Bacon, for instance, made an explicit connection between long-distance travel (that is, colonial expansion and the knowledge transfers it unleashed) and the growth of various scientific disciplines.31 Since the colonies could not be managed directly by the metropolis, they had to be objectified through scientific means and represented through emerging forms of records that could travel through time and space and thus conquer complexity.

Africa: A Biography of the Continent

by

John Reader

Published 5 Nov 1998

Lovejoy's estimates show that an average of about 2,500 slaves were exported each year between 1450 and 1600; but this figure rose to 18,680 per year for the period 1601 to 1700, and reached a peak of 61,330 per year during the following century (1701 to 1800); even at the end of the nineteenth century (ninety years after abolition) it was still running at an average of 33,300 slaves per year.10 The surge in numbers can be attributed to the discovery of the Americas and the European taste for sugar. Columbus discovered the Caribbean islands and North America for Spain in 1492; Pedro Alvares Cabral discovered Brazil for Portugal in 1500. Both the Caribbean islands and the Brazilian coastlands were ideally suited for the production of sugar; both regions were inhabited by people whom Pêro Vaz da Caminha (a chronicler who sailed with Cabral) described as ‘people of good and pure simplicity [with] fine bodies and good faces’.11 But their natural attributes were no defence against the disease and labour demands of the Portuguese settlers, who began to establish sugar plantations in Brazil during the 1540s.

…

Sailors were warned to be silent; facts about the discoveries were carefully garbled; maps and navigation charts were removed from contemporary books, and the making of globes, maps, and charts became the privilege of a single family, whose loyalty to the Portuguese crown was unquestioned.12 Direct action included standing orders which instructed Portuguese sea-captains to seize all foreign vessels encountered on the West African coast and cast their crews into the sea.13 But of course word did leak out, and vessels of other nations persistently defied the Portuguese monopoly. After 1492 the attention of an avaricious neighbour, Spain, was diverted from West Africa by the discovery of the Americas, but the French and the English, the Dutch and the Danish, would not be kept out. Often they not only traded in the territories that Portugal had claimed but took additional profit by seizing Portuguese vessels as well. Between 1500 and 1531, for example, French ships alone captured more than 300 Portuguese vessels in West African waters and along the coast of Brazil.14 During the sixteenth century the Portuguese expanded their empire to include territories spread around the globe from South America to the Spice Islands of the Far East.

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by

William Easterly

Published 4 Mar 2014

The emergence from autocracy toward freedom had happened in a few northern Italian cities. But freedom only had a future if it continued to spread. FREEDOM MOVES TO THE ATLANTIC The most famous son of Genoa, Christopher Columbus, would inadvertently make possible the spread of freedom. The boom in European trade after the discovery of the Americas gave freedom new strongholds 800 miles north of Genoa. Economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson of MIT and political scientist James Robinson of Harvard have been pioneers in reintroducing historical research into economics, with the aim of explaining economic development. In a prominent 2005 article,21 they tackled the question of why the frontiers of freedom had shifted from northern Italy to Western Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by

Justin Fox

Published 29 May 2009

Now, by ditching the equilibrium while sticking with math, economists are finding better ways to describe the dynamics of growth and change. A key word in the new growth theory is “endogenous”—that is, arising from within. In an equilibrium, all disturbance must by definition come from outside. Explaining a spurt in economic growth requires a deus ex machina such as the discovery of the Americas or the invention of the electric motor. In new growth theory, the technological drivers of growth are depicted as the result of economic forces and decisions.31 Bringing this concept of endogenously generated change to the shorter-term fluctuations of the market is a more complex endeavor.

The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World

by

Simon Winchester

Published 7 May 2018

The timetable became a biblically important volume in all libraries and some households; the concept of time zones and their application to cartography all stemmed from railways’ imprint of timekeeping on human society. Yet, before the chronological influence of railways, there was one other profession that above all others truly needed the most precise timekeeping. It was that which had been developing fast since the European discovery of the Americas in the fifteenth century and the subsequent consolidation of trade routes to the Orient: the shipping industry. Navigation across vast and trackless expanses of ocean was essential to maritime business. Getting lost at sea could be costly at best, fatal at worst. Also, because the exact determination of where a ship might be at any one moment was essential to the navigation of a route, and because one part of that determination depends, crucially, on knowing the exact time aboard the ship and, even more crucially, the exact time at some other stable reference point on the globe, maritime clockmakers were charged with making the most precise of clocks.* And none was more sedulously dedicated to achieving this degree of exactitude than the Yorkshire carpenter and joiner who later became England’s, perhaps the world’s, most revered horologist: John Harrison, the man who most famously gave mariners a sure means of determining a vessel’s longitude.

The Taste of Empire: How Britain's Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World

by

Lizzie Collingham

Published 2 Oct 2017

They succeeded in rounding Cape Bojador in 1434, and a decade later discovered that if on the voyage home they counter-intuitively sailed first in a north-westerly direction, they could pick up trade winds that would blow them back towards the European continent.12 The Portuguese were seeking access to Africa’s gold, but soon tapped into the West African slave trade, bringing the first consignment of slaves to reach Europe by sea back to Lisbon in 1434. Their advances in navigation opened up the Atlantic Ocean to European seafarers and eventually led to the discovery of the Americas, where the Portuguese introduced sugar into Brazil and began to transport Africans across the Atlantic to work on the plantations. In the mid seventeenth century other Europeans–French, Prussians, Danes, Swedes, Dutch and the English–joined the Portuguese on the West African coast, all jostling for a share of the lucrative slave trade.

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 28 Feb 2011

It would be Europeans that reached out across the Atlantic Ocean to take possession of a vast landmass that, prior to Martin Waldseemüller’s Universalis cosmographia of 1507, simply did not appear on maps: America – named after the explorer Amerigo Vespucci.* It was Europe’s monarchies – above all Spain and England – who, vying for souls, gold and land, were willing to cross oceans and conquer whole continents. To many historians, the discovery of the Americas (broadly defined to include the Caribbean) is the paramount reason for the ascendancy of the West. Without the New World, it has been asserted, ‘Western Europe would have remained a small, backward region of Eurasia, dependent on the East for transfusions of technology, transmissions of culture, and transfers of wealth.’1 Without American ‘ghost acres’ and the African slaves who worked them, there could have been no ‘European Miracle’, no Industrial Revolution.2 In view of the advances already achieved in Western Europe both economically and scientifically prior to large-scale development of the New World, these claims seem overblown.

How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism

by

Eric Hobsbawm

Published 5 Sep 2011

The source of this labour was partly the former feudal retainers and armies, partly the population displaced by agricultural improvements and the substitution of pasture for tillage. With the rise of manufactures nations begin to compete as such, and mercantilism (with its trade wars, tariffs and prohibitions) arises on a national scale. Within the manufactures the relation of capitalist and labourer develops. The vast expansion of trade as the result of the discovery of the Americas and the conquest of the sea-route to India, and the mass import of overseas products, notably bullion, shook the position both of feudal landed property and of the labouring class. The consequent change in class relations, conquest, colonisation ‘and above all the extension of markets into a world market which now became possible and indeed increasingly took place’26 opened a new phase in historical development.

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 12 May 2014

Turning to England, Smith observed that American silver did not seem ‘to have had any very sensible effect upon the price of things in England till after 1570; though even the mines of Potosi had been discovered more than twenty years before’.45 Yet, of the modern economists, it was John Maynard Keynes who most frequently returned to the theme of the discovery of the Americas and their effect on the modern world. In 1930 he wrote: ‘The modern age opened . . . with the accumulation of capital which began in the sixteenth century. I believe . . . that this was initially due to the rise of prices, and the profits to which that led, which resulted from the treasure of gold and silver which Spain brought from the New World into the Old.’46 The possibilities thrown up by the expansion of Spain into the Americas, with the flow of bullion and treasure which accompanied the discovery of new mines, fascinated Keynes.

The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible

by

Simon Winchester

Published 14 Oct 2013

Diary of My Travels in America, tr. Stephen Becker. New York: Delacorte Press, 1977. Lyell, Charles. A Second Visit to the United States of North America. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855. ———. Travels in North America in the Years 1841–1842. New York: Charles E. Merrill, 1909. Mann, Charles C. 1493: How Europe’s Discovery of the Americas Revolutionized Trade, Ecology and Life on Earth. London: Granta, 2011. Marx, Leo. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1964. Masters, Edgar Lee. Spoon River Anthology. New York: Macmillan, 1916; Signet Classics, 1992.

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by

Will Hutton

Published 30 Sep 2010

Without it, the growth of science would have been impossible as there could have been no codifying or dissemination of scientific discoveries. Then there is the three-masted sailing ship, which allowed large vessels to sail close to the wind, permitted the Portuguese and then their European imitators to sail around the world. Without this GPT, there would have been no circumnavigation of the globe; no discovery of the Americas, leading to new centres of power and productive capacity; no European colonisation; no long-distance sea trade; no rich European merchant class; no consequent financial innovations, such as joint stock companies and marine insurance, to deal with the risk and uncertainty of long voyages; and less possibility of the principles of magnetism being understood.

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by

Philip Coggan

Published 6 Feb 2020

Madeira experienced a phenomenal boom and bust, with sugar production rising from 280 tons in 1472 to 2,500 tons in 1506, before falling 90% by 1530. In the process, Madeira, whose name means island of wood, was almost completely deforested, since sugar production required massive amounts of energy.16 After the discovery of the Americas, the Portuguese first planted sugar cane in Brazil in 1516, and started to produce a commercial crop after 1550. At first they relied on indigenous workers, but there was a huge death rate from disease. So they focused instead on slaves from West Africa, where there was a rivalry between the kings of Congo and Ndongo (modern Angola) over who should be their main supplier.17 For African leaders who handed over prisoners of war, or other unfortunates captured during raids, it was a highly lucrative business.

Spain

by

Lonely Planet Publications

and

Damien Simonis

Published 14 May 1997

The room gives on to the pretty Patio del Yeso, a 19th-century reconstruction of part of the 12th-century Almohad palace. PATIO DE LA MONTERÍA The rooms on the western side of this patio were part of the Casa de la Contratación, founded by the Catholic Monarchs in 1503 to control American trade. The Sala de Audiencias contains the earliest known painting on the discovery of the Americas (by Alejo Fernández, 1530s), in which Columbus, Fernando El Católico, Carlos I, Amerigo Vespucci and Native Americans can be seen sheltered beneath the Virgin in her role as protector of sailors. PALACIO DE DON PEDRO (MUDEJAR PALACE) He might have been ‘the Cruel’, but between 1360 and 1364 Pedro I humbly built his exquisite palace in ‘perishable’ ceramics, plaster and wood, obedient to the Quran’s prohibition against ‘eternal’ structures, reserved for the Creator.

…

From the train station ( 902 24 02 02) three daily trains head to Seville (€7.50, 1½ hours). Return to beginning of chapter LUGARES COLOMBINOS The Lugares Colombinos (Columbus Sites) are the three townships of La Rábida, Palos de la Frontera and Moguer, along the eastern bank of the Tinto estuary east of Huelva. All three played key roles in the discovery of the Americas and can be combined in a single day trip from Huelva, the Doñana area or the nearby coast. La Rabida pop 600 In this pretty and peaceful town, don’t miss the 14th-century Monasterio de La Rábida ( 959 35 04 11; admission €3; 10am-1pm & 4-7pm Tue-Sat Apr-Jul & Sep, 10am-1pm to 6.15pm Tue-Sat Oct-Mar, 10am-1pm & 4.45-8pm Tue-Sat Aug, 10.45am-1pm Sun year-round), visited several times by Columbus before his great voyage of discovery.

…

Posada Restaurante Dos Orillas (927 65 90 79; www.dosorillas.com; Calle de Cambrones 6; meals €25-30; lunch & dinner Tue-Sat, lunch Sun; ) Just as the hotel is a gem, so the restaurant is a place of quiet, refined eating, whether al fresco on the patio or in dining room with its soft-hued fabrics. Vegetarian dishes include pasta with broccoli and cheese and courgettes stuffed with oyster mushrooms; carnivores won’t go hungry. * * * EXTREMADURA & AMERICA Extremeños jumped at the opportunities opened up by Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492. In 1501 Fray Nicolás de Ovando from Cáceres was named governor of all the Indies. He set up his capital, Santo Domingo, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. With him went 2500 followers, many of them from Extremadura, including Francisco Pizarro, the illegitimate son of a minor noble family from Trujillo.

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

Simon Johnson

Published 15 May 2023

The changes in the countryside may have been even more momentous. This is the period during which we see the emergence of the yeoman farmers and skilled artisans as both economic and social forces. The social changes that were underway accelerated because of England’s overseas expansion. The “discovery” of the Americas by Columbus in 1492 and the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by Vasco da Gama in 1497 opened up new, lucrative opportunities for Europeans. England was a latecomer to the colonial adventures, and by the end of Elizabeth’s reign, it had no significant colonies abroad and a navy that was barely strong enough to confront the Spanish or the Portuguese.

When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Rise of the Middle Kingdom

by

Martin Jacques

Published 12 Nov 2009

In the light of the economic transformation of so many former colonies after 1950, it is clear that the significance of decolonization and national liberation in the first two decades after the Second World War has been greatly underestimated in the West, especially Europe. Arguably it was, bar none, the most important event of the twentieth century, creating the conditions for the majority of the world’s population to become the dominant players of the twenty-first century. As Adam Smith wrote presciently of the European discovery of the Americas and the so-called East Indies: To the natives, however, both of the East and West Indies, all the commercial benefits which can have resulted from these events have been sunk and lost in the dreadful misfortunes which they have occasioned . . . At the particular time when these discoveries were made, the superiority of force happened to be so great on the side of the Europeans, that they were enabled to commit with impunity every sort of injustice in those remote countries.

Lonely Planet London

by

Lonely Planet

Published 22 Apr 2012

Richard III didn’t have long to enjoy the hot seat: he was killed in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field by Henry Tudor, first monarch of the eponymous dynasty. Tudor London London became one of the largest and most important cities in Europe during the Tudor reign, which coincided with the discovery of the Americas and thriving world trade. Henry’s son and successor, Henry VIII, was the most ostentatious of the clan, instructing new palaces to be built at Whitehall and St James’s, and bullying his lord chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, into gifting him Hampton Court. Begging was treated very harshly in 16th century London.

Migrant City: A New History of London

by

Panikos Panayi

Published 4 Feb 2020

These new global cities, epitomized by London, therefore appear to share several characteristics, above all: the internationalization of their economy through the entry of firms from other parts of the world; the increasing ethnic diversity of their workforce and population; and, as a consequence of the first two, increasing inequality.6 Such assumptions lack historical perspective, viewing the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in particular against the background of the relative equality of the post-war consensus years; failing to take account of the history of globalization, which has impacted upon everyday life since the European ‘discovery’ of the Americas; as well as ignoring the role of local, national, continental and international migration in the evolution of many of the major metropolises which exist in the world today over decades if not centuries. While London has much in common with many of the other global cities which exist today, it has, purely from the point of view of migration, five characteristics that help to make it unique.

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

by

David Abulafia

Published 2 Oct 2019

This makes the last five centuries more manageable. But it also represents reality: the oceans had become intimately interconnected, as a quick glance at the Portuguese, Dutch or Danish maritime networks quickly shows. This interconnection of the oceans was the great revolution that followed the discovery of the Americas and of the route from Europe to Asia by way of the southern tip of Africa, and it has received too little attention. One important theme of this book is the human occupation of previously uninhabited islands, beginning with the extraordinary achievements of Polynesian sailors in settling the scattered islands of the largest ocean of all.

…

However, the persecution waned and the community recovered.50 Aden was also a base from which the Cairo merchants sent letters eastwards to India, with information about the state of the pepper market – anticipating where prices would be profitable was fundamental to the business practice of these merchants, who were not mere passive agents.51 The sailing season out of Aden was, by natural circumstances, well co-ordinated with that of the Mediterranean, with ships setting out for India at the start of autumn, which gave time for goods that were being carried down the Red Sea to reach their eastern Mediterranean destinations from as far away as Sicily, Tunisia and Spain. Aden was therefore a nodal point not just in the Indian Ocean maritime networks, but in what can reasonably be called (before the discovery of the Americas) a global network that stretched from Atlantic Seville to the Spice Islands of the Indian Ocean. Broadly speaking the port was very lively from the end of August to May of the following year. Ships converged on Aden from India, Somalia, Eritrea and Zanj (east Africa), so that Aden became a market where the produce of Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean was exchanged.52 V Moving deeper into the Indian Ocean, the Egyptian merchants who had called in at Aden took advantage of the monsoons to head across the open sea to India.

Lonely Planet London City Guide

by

Tom Masters

,

Steve Fallon

and

Vesna Maric

Published 31 Jan 2010

Richard III didn’t have long to enjoy the hot seat, however, as he was deposed within a couple of years by Henry Tudor, the first monarch of the dynasty of that name. Return to beginning of chapter TUDOR LONDON London became one of the largest and most important cities in Europe during the reign of the Tudors, which coincided with the discovery of the Americas and thriving world trade. Henry’s son and successor, Henry VIII, was the most ostentatious of the clan. Terribly fond of palaces, he had new ones built at Whitehall and St James’s, and bullied his lord chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, into gifting him Hampton Court. His most significant contribution, however, was the split with the Catholic Church in 1534 after the Pope refused to annul his marriage to the non-heir-producing Catherine of Aragon.

The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous

by

Joseph Henrich

Published 7 Sep 2020

During the first half of the second millennium, the leading candidates for the source of this earth-shaking economic transformation would have been China, India, and the Islamic world, not Europe. Proposed explanations for “Why Europe?” emphasize the development of representative governments, the rise of impersonal commerce, the discovery of the Americas, the availability of English coal, the length of European coastlines, the brilliance of Enlightenment thinkers, the intensity of European warfare, the price of British labor, and the development of a culture of science. I suspect that all of these factors may have played some role, even if minor in some cases; but, what’s missing is an understanding of the psychological differences that began developing in some European populations in the wake of the Church’s dissolution of Europe’s kin-based institutions.

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by

Jan Lucassen

Published 26 Jul 2021

Remarkably, until the end of the eighteenth century, labour relations in parts of Eurasia, Western Europe, India, China and Japan developed in a similar way, namely by increasing the input of labour on the market – that of men and, now, women and even children – called the ‘industrious revolution’.3 However, this increased labour intensity in vast areas of Eurasia, in what was home to perhaps the largest part of the global population at that time, cannot hide the fact that Western Europe was stealing a march in other areas, to the extent that, from around 1800, it would dominate the whole world. This happened in a number of steps. Firstly, the discovery of the Americas swiftly culminated in conquest, and the existing tributary labour relations of the Aztecs and the Inca were upended, with great benefits for the Spanish and Portuguese and later the Dutch, French, English and other invaders. Secondly, captives sold to Europeans in the ports of West Africa were put to work as slaves on plantations in the Americas.

Why the West Rules--For Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future

by

Ian Morris

Published 11 Oct 2010

Yet the last two hundred years have seen more economic growth than all earlier history put together. The reason, Pomeranz explains in his important book The Great Divergence, is that western Europe, and above all Britain, just got lucky. Like Frank, Pomeranz sees the West’s luck beginning with the accidental discovery of the Americas, creating a trading system that provided incentives to industrialize production; but unlike Frank, he suggests that as late as 1800 Europe’s luck could still have failed. It would have taken a lot of space, Pomeranz points out, to grow enough trees to feed Britain’s crude early steam engines with wood—more space, in fact, than crowded western Europe had.

Caribbean Islands

by

Lonely Planet

But it wouldn’t be his last campaign – he would run once more at the age of 92, winning 23% of the vote in the 2000 presidential election. Thousands would mourn his death two years later, despite that he had prolonged the Trujillo-style dictatorship for decades. His most lasting legacy may be the Faro a Colón, an enormously expensive monument to the discovery of the Americas that drained Santo Domingo of electricity whenever the lighthouse was turned on. Breaking with the Past The Dominican people signaled their desire for change in electing Leonel Fernández, a 42-year-old lawyer who grew up in New York City, as president in the 1996 presidential election; he edged out three-time candidate José Francisco Peña Gómez in a runoff.

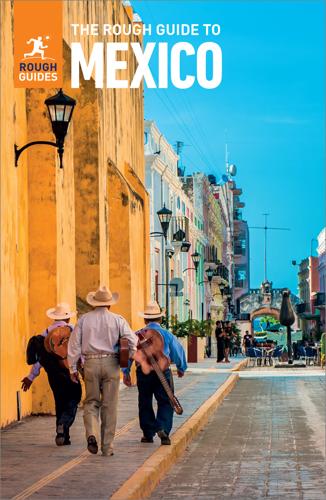

The Rough Guide to Mexico

by

Rough Guides

Published 15 Jan 2022

Celebrated in Morelia (see page 251). Fiestas de Octubre (all month). Massive cultural festival in Guadalajara (see page 217). Día de San Francisco (Oct 4). Saint’s day celebrations in Uruapan (see page 240). Día de la Raza (Oct 12). Uruapan (see page 240) celebrates Columbus’s “discovery” of the Americas. Día de la Virgen de Zapopan (Oct 12). Massive pilgrimage in Guadalajara (see page 217). Festival de Coros y Danzas (Oct 24–26). Singing and dancing competitions in Uruapan (see page 240). Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead; Nov 2). Celebrated everywhere, but especially around Pátzcuaro (see page 250).

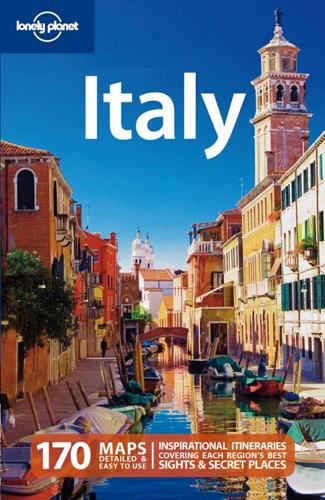

Italy

by

Damien Simonis

Published 31 Jul 2010

By the mid-15th century, Venice was swathed in golden mosaics, imported silks and clouds of incense to cover the belching, sulphuric smells that were the downsides of a lagoon empire. But events beyond Venice’s control took their toll. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the Venetian territory of Morea (in Greece) in 1499 gave the Turks control over Adriatic Sea access. The Genovese gained the upper hand with Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492, calling dibs on New World trade routes. Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope in 1498, opening up new trade routes that bypassed the Mediterranean – and Venetian taxes and duties. As it lost its dominion over the seas, Venice changed tack and began conquering Europe by charm.

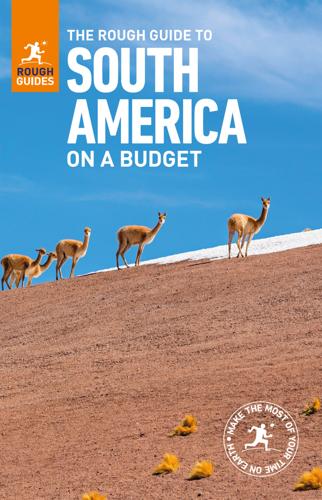

The Rough Guide to South America on a Budget (Travel Guide eBook)

by

Rough Guides

Published 1 Jan 2019

Public holidays January 1 New Year’s Day (Año Nuevo) Easter (Semana Santa) national holidays on Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday May 1 Labour Day (Día del Trabajo) May 21 Navy Day (Día de las Glorias Navales) marking Chile’s naval victory at Iquique during the War of the Pacific June 29 St Peter and St Paul (San Pedro y San Pablo) July 16 Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Solemnidad de la Virgen del Carmen, Reina y Patrona de Chile) August 15 Assumption of the Virgin Mary (Asunción de la Virgen) September 17 If it falls on a Monday, an extension of Independence celebrations September 18 National Independence Day (Fiestas Patrias) celebrates Chile’s proclamation of independence from Spain in 1810 September 19 Armed Forces Day (Día del Ejército) September 20 If it falls on a Friday, an extension of Independence celebrations October 12 Columbus Day (Día del Descubrimiento de Dos Mundos) celebrates the European discovery of the Americas November 1 All Saints’ Day (Día de Todos los Santos) December 8 Immaculate Conception (Inmaculada Concepción) December 25 Christmas Day (Navidad) Festivals January 20 San Sebastián. Spaniards brought the first wooden image of San Sebastián to Chile in the seventeenth century. After a Mapuche raid on Chillán, the image was buried in a field, and no one was able to raise it.