do-ocracy

description: forms of governance where individuals independently choose and perform their tasks

23 results

They Don't Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy

by

Lawrence Lessig

Published 5 Nov 2019

Swing-state Democrats turn a blind eye to steel tariffs. Democrats generally don’t. Rather than a bias that runs in an obvious direction, the sum of these different inequalities bends consistently in no particular direction. This is not the physics of a plutocracy. It is the dynamic of a vetocracy—a “veto-ocracy,” as Francis Fukuyama puts it.129 As Fukuyama describes, the American Constitution already embeds many veto points for any substantial legislation. A law can be stopped in either house. A law can be slowed by the president. A law can be struck down by the courts. A president can refuse to enforce a law.

…

FEC (2010), 61, 140, 146 EndCitizensUnited.org, 258 civic juries, 180–182, 228 candidate selection advice, 196 shadow conventions, 182–186 Civil Rights Act (1964), 26 Clinton, Bill, 36, 107, 227 Clinton, Hillary 2016 in New Jersey, 241 broken system, 231, 235 email “scandal,” 99–101 media negativity, 102 pizza parlor pedophilia ring, 103 comedy importance, 203–204 Congress amendment ratification, 182 bipartisanship of yore, 26 bribery laws, 48 congressional jury, 188–190 the Congressional Record, 78 constitutional jury results, 185 election equality oversight, 10–14, 17, 153 governing separated from elections, 229–230 informational independence, 228–230 pay raises needed, 228 polarization within, 25–27 political stalemate vs. congressional jury, 189–190 political system failing the nation, 66 Reform Caucus, 256–258 roll call votes measuring influence, 27, 272n64 “safe seats,” 22, 24–25, 28, 29, 62–63, 152, 153 shadow Congress, 188–190 status quo defended by, ix, 64–66 See also House of Representatives; Senate Constitution Article V convention movement, 182–186, 258–261, 307n17 Article V Equal Suffrage Clause, 31, 139, 156, 300n23 constitutional jury, 183–186 election equality oversight by Congress, 10–11, 17, 153 Electoral College winner take all system, 36 electors for legislature, 35 electors for president, 34–36 equal allocation of political power, [168n38], 170, 304n38 equality in representation, 139 Iceland crafting new, 177, 306n7 Mongolian amendment process, 175–177 one person, one vote, 8 proportional representation vs. Senate, 3–4, 31, 34 right to vote, 6–7 vetocracy (veto-ocracy), 64 constitutional jury, 183–186 copyright in digital age, [111n92], 113, 290n92 corporate speech regulated, 58, 146 corruption regulation bribery laws, 47–48, 147 campaign contributions, 61, 140–141, 146, 147 campaign donations as favors, 57–62, 224–225 dependence corruption, 150, 299n17 SuperPACs, 140, 147–151, 261, 298n13 Cramer, Katherine, 10 Crosscheck and voter rolls, 15–16 Crossly, Archibald, [68nn4–5], 69, 281n4, 282n5 crowdsourcing skills for reform, 235–236, 239–240, 246, 247, 256–257 dark money, [59n120], 140, 279n120 data consent to use, [111n92], 113, 290n92 Facebook collecting, 109, 114–117 Facebook harming democracy, 117, 118–123 Facebook inducing to reveal, 115–117, 122–123, 292n108 fiduciary duty applied, 212–219 monetization of, 109–113 use and privacy, [111n92], 113, 117–119, 290n92 deliberative polling about, 175–178, 307n11 civic juries, 180–182, 196, 228 congressional jury, 188–190 constitutional juries, 183–186 informing representatives, 228 selecting candidate for mayor, 196 democracy advertising and information, 91–93, 98–99, 101, 105–107, 120–123, 200–201 elite rule “the people,” xiii, 61–66 experimental projects for improvement, [178n11], 307n11 Facebook harming, 117, 118–125 Georgia building, 133–134 Georgia tearing down, 168–169 growth in twentieth century, xiii ignorance weakening, 135–136, 174.

…

See also ignorance loss of faith in, xi–xiv, 179–180, 264n3 majoritarianism defeated by Senate, 33–34 majoritarianism via ranked-choice voting, 153–155, 240, 315n9 media educating public, 85, 101–104, 173, 192, 201–203, 204–212, 288nn71–72 muddled middle importance, 108–109, 124 “the people” caring about fixing, 235–237, 246, 247 “the people” ruling, xiii, 61–66, 130–132, 135–136, 174, 249, 294n125 polarization what we want, 121–123 post-broadcasting, 79–88, 127–128 public opinion poll role, 71, 131–133, 135–136, 226, 283n17, 283n20 representativeness importance, 139, 221–230 representatives not needed, 68–69 “republic” as “representative,” 3–5 sortition vs. elections, 186–190 vetocracy (veto-ocracy), 63–66 See also knowledge; representative democracy democracy coupons (DC), 142–146, 151, 166–167, 296n6 Democracy R&D, [178n11], 307n11 Democracy When the People Are Thinking (Fishkin), [178n10], 307n10 Democrats 2018 midterm sweep, 227 control of all three branches, 204 gerrymandering attempt, 241–246 HR1 (116th Congress), 250–252 moneyed special interests, 59.

Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America

by

Conor Dougherty

Published 18 Feb 2020

YIMBYs had so infected the narrative that even candidates who didn’t agree with them were defensively using some version of “build” in their pitch. Growth had its challenges. Four years earlier, it was a do-ocracy called SF BARF that consisted of Sonja and a few friends showing up at public meetings. Housing was just a fun way to rabble‐rouse and use politics as a means of meeting other people who were new to the Bay Area. Now Sonja was yelling at campaign consultants in high‐pressure moments, prompting other consultants to pull her behind shut doors to say, “You can’t do that.” Sacramento political operators had to tell Brian that he wouldn’t go far in the capitol if he kept doing things like Tweeting a cartoon picture of the California flag in which the state’s iconic grizzly bear emblem was being stabbed in the back with a knife bearing the name of a Marin County assemblyman that he considered to be overly NIMBYish.

…

It was around a thousand words long and veered from philosophical ramblings on the nature of power to the success of Christianity being in its many sects. Sonja talked about how people can only really control themselves and her belief that life is a “do-ocracy.” Finally, she ended: “If you have a group in your city that you think is too extremely YIMBY, lucky for you, they’ve created a very cushy role for you called ‘good cop.’” That seemed just about right. She’d blown a hole in the public conversation and in doing so had created the space for gentler voices to help fill it. Nobody was going to thank her for the service, but it was necessary dirty work, and now it was done. The day after the election she called Matt Haney to congratulate him on winning and reverted to her advocate role by pressing him to introduce her affordable housing everywhere proposal.

…

Realizing that housing was a potent and winning issue, Laura started a group called Grow SF and joined Sonja in indignant public comment. Laura was confident and argumentative like Sonja, but this was not to say they were exactly alike. Sonja’s roughness bordered on performance art and she described SF BARF as a “do‐ocracy” where anyone could work on anything they wanted, so long as they actually did it. This wasn’t just a motivator. It was a means of self-protection that prevented Sonja from having to endure the emotional labor of organization building by discouraging anyone who wasn’t self-motivated from sticking around.

Who Owns England?: How We Lost Our Green and Pleasant Land, and How to Take It Back

by

Guy Shrubsole

Published 1 May 2019

Yet 703,289 were owners of less than an acre, leaving 269,547 who owned an acre or above. Even this, the clerks pointed out, was likely an overestimate, based on county-level figures: anyone who owned land in multiple counties would be double-counted. It fell to an author and country squire, John Bateman, to interpret and popularise the return. In 1876 he published The Acre-Ocracy of England, in which he summarised the owners of 3,000 acres and above. It became a best-seller, going through four editions and updates which culminated in Bateman’s last work on the subject in 1883, The Great Land-Owners of Great Britain and Ireland. Bateman’s analysis confirmed the radicals’ worst fears: just 4,000 families owned over half the country.

…

whether it is The Earl of Derby, ‘Number of Land and House Owners: Question to the Lord Privy Seal’, House of Lords debate 19 February 1872, Hansard vol. 209 cc639–43. upwards of 300,000 Local Government Board, Return of Owners of Land 1873 (July 1875), Vol. 1. In 1876 he published John Bateman, The Acre-Ocracy of England (1876), available online at: httphttps://archive.org/details/acreocracyengla00bategoog Bateman’s last work John Bateman, The Great Land-Owners of Great Britain and Ireland, 1883, available online at: https://archive.org/details/greatlandownerso00bateuoft the legend of 30,000 Cahill, Who Owns Britain, p. 39.

…

You can use your ebook reader’s search tool to find a specific word or passage. 38 Degrees 42 57 Whitehall SARL 147 Abbeystead, Lancashire 97 Abdullah, Prince Khalid 123 Abramovich, Roman 125, 127 Abu Dhabi 122 Access to Mountains Act (1939) 251 Acland Committee (1916) 172 Acland, Sir Richard 242 Adams, Richard, Watership Down 257 Addison, Christopher 154, 227 Afolami, Bim 231 agriculture: effect of industrialised practices on 11; farm subsidies 39–40, 106–7, 274, 278, 282, 306–7; organic 12–13; use of pesticides 11–12, 13 Air Ministry 160, 162 Al-Fayed, Mohamed 120–1 Al-Maktoum, Rashid bin Saeed, Sheikh of Dubai 121 al-Maktoum, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, Emir of Dubai 121–2, 123 Al-Tajir, Mahdi 121 al-Yamamah arms deals 124 Albanwise Ltd 37 Albert, Prince 46 Alderley Edge, Cheshire 131 Aldermaston 13 Alfriston, Sussex 240 allotments 223, 224–5, 226, 286 Allotments Acts (1887 & 1908) 30, 225, 286 Alnwick Castle 76 Alton Towers, Derbyshire 100–1 Amazon 191 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 26 Anstruther, Sir Sebastian 249 Arago Ltd (Jersey) 122, 301 Arat Investments (Guernsey) 122, 303 Argentina 116–17 aristocracy: apparent decline 84–7; benefits of land ownership 79–80; bloodsports 95–8, 106, 108; challenges facing 280; coal mining and fracking 90–1; dilution of wealth and power 113, 119; estimates of land ownership 87–8, 266–7; extent of land ownership 75–7; farming subsidies 106–7; formation and acquisition of estates 77–80, 107, 270–1; hereditary titles 81–3; land owned by dukes 306–7; and male primogeniture 80–1, 281; newcomers 83; parkland 88–9; rental income and urban estates 92–5, 108; as stewards of the landscape 89–90; taxation and death duties 98–106, 107–8 Arlington, Napier Sturt, 3rd Baron 160, 161, 163 arms deals 123–4 Arundel 76 Arundel, Earls of 76 Ashworth, Lindsey 184 Assynt Estate, Sutherland 116 Astor, Charles John 118n Astor family 18, 118 and note Astor, James Alexander Waldorf 118n Astor, Nancy 118 Astor, Robert 118n Astor, William, 4th Viscount 118 Astor, William Waldorf, 1st Viscount 118 Atomic Weapons Establishment 169; Burghfield 13; Orford Ness 170–1 Attlee, Clement 228, 243, 275 Avery, Mark 98, 280 Badanloch, Sutherland 117 Badgworthy Land Company 249, 302 BAE Systems 124, 190 Baggini, Julian 235 Balmoral 46, 47, 51, 97 Balnagown, Easter Ross 121 Bandar, Prince 124 Banks, Catherine 42 Barbour, Mary 227 Barclays Bank 192 Barnett, Anthony 36 Barrington Court, Somerset 240 Barron, Gill 67 Bateman, John: The Acre-Ocracy of England 30; The Great Land-Owners of Great Britain and Ireland 30 Bath, Henry Thynne, 6th Marquess 101 Bathurst, Allen, 9th Earl 103 Bayer 12 the Beatles 212 Beckett, Andy 14–15 Beckett, John 85 Beckett, Matthew 100 Beckett, Sir Richard 248n Bedford, Andrew Russell, 15th Duke 91 Bedford, Ian Russell, 13th Duke 101 Bedgebury Estate, Kent 173 Beeching, Dr Richard 178–9 bees 12, 13 Beke, Dr 28 Bell, Steve 224 Bellingham, Sir Henry 21 Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire 88 Benn, Tony 63 Bentley, Daniel 230 Benyon, Richard 19–21 Berezovsky, Boris 126 Berkhamsted Common 215 Bevan, Aneurin ‘Nye’ 228 Biffa 194 Biological Weapons Convention (1972) 168 Birkenhead 70 Birmingham Back-to-Backs 243 Black Prince (Edward of Woodstock) 58 Blackfriars Holdings Ltd 68 Blagdon Estate, Northumberland 90–1 Blair, Tony 36, 106, 124, 132, 206 Blatchford, Robert: Land Nationalisation 229; Merrie England 229 Blavatnik, Sir Len 135 Bledisloe, Charles Bathurst, 1st Viscount 99 Blickling Estate, Norfolk 242 Bloomberg, Michael 111 Blue Star Line 115 Bodiam Castle, Sussex 241 Bodmin Moor 59 Boles, Nick 231 Bollihope grouse moor, North Pennines 122 Bolton Abbey 97 Bonham-Carter, Victor 173 Borisovich, Roman 128 Boughton, John 227 Bowes Moor, County Durham 168 Boyne, Gustavus Hamilton-Russell, 11th Viscount 248n Brand, Russell 19 Brand, Stewart 41 ‘Breckland exodus’ (1942) 158 Brexit 40, 64, 107, 130, 278 Brideshead Revisited (ITV series, 1981) 105 Briggs, Raymond, When the Wind Blows 143 Bright, John 222 Bristol 78 British Coal 180 British Overseas Territories 129, 274 British Virgin Islands 38, 68, 109, 118, 126, 129, 131 Brodrick, George 30 Brooke, Rupert 155 Brooks, Rebekah 132 Brooks, Richard 188 Brougham, Lord 28 Brown, Lancelot ‘Capability’ 78, 89 Bryant, Chris 88 Buckenham Tofts 158 Bureau of Investigative Journalism 192 Burke’s Peerage 82 Burnt Common, Berkshire 20 Burrell, Sir Charles 260 Burton-upon-Trent 56 Bush, M.L. 92 cadastral maps/surveys 27–8, 273 Cade, Jack 219 Cadogan, Charles, 8th Earl 94 Caesar, Ed 126 Cahill, Kevin 66; Who Owns Britain 4, 86 Callaghan, James 230, 257 Cambridgeshire 226 Cameron, David 20, 118, 132, 146, 176, 181 Cameron, Samantha 118 Campaign for Freedom of Information (1984) 36 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) 13 campaigning organisations 307–8 Campbell, Duncan 14, 140, 143; War Plan UK 143 Candy Brothers 111 Cannadine, David 84, 101; The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy 84 Cannock Chase, Staffordshire 50 Canute, King 62 CAP see EU Common Agricultural Policy Carlisle 91 Carlisle, George Howard, 13th Earl 105 Carnarvon, George Herbert, 8th Earl 9–10 Carphone Warehouse 131, 248 and note Carroll, Lewis, Alice in Wonderland 9 Carson, Rachel, Silent Spring 167, 257 Castle Howard, North Yorkshire 105 Cayman Islands 18, 103, 274 Census 27, 29 Centre for Policy Studies 276 Chamberlain, Joseph 222–3, 225; The Radical Programme 223 Chamberlain, Neville 156, 195 Chanctonbury Ring, South Downs 251 Channel Islands 37, 38, 46, 68, 103, 119, 121, 122, 123 Charles I 26, 52, 211 Charles, Prince ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ 65 Charles, Prince of Wales 58, 59–60, 281 Charter 88 36 Charter of the Forest (1217) 50–1 Charterville, Oxfordshire 221 Chartist Co-operative Land Society 221 Chartist Land Company 221 Chartist Land Plan 220–1 Chartists 220, 222 Chatsworth House, Derbyshire 88, 97 Chelsea Football Club 125 Chesham, John Cavendish, 5th Baron 142 Cheshire 56, 75 Chipping Norton set 132 Cholmondeley, David, 7th Marquess 46, 103 Christophers, Brett 179, 284 Church Commissioners 68–72, 94, 298 Church lands 27, 72–3, 265, 283, 297, 298; financial management of 68–72; glebe land 65–8, 72; historical background 64–5; and housing crisis 72; loss of 66–8; mineral rights and fracking 71–2 Churchill, Winston 1, 2, 3, 24, 33, 139, 140, 141, 157, 158, 160; The People’s Rights 31 City of London 103, 193 City of London Corporation 215, 256 Civil List 52–3, 54 Civitas 230, 276, 308 CLA see Country Land and Business Association ClampK lobby group 125 Clare, John 78 Clarion cycling clubs 251 Clark, Kenneth, Baron 103 Clayton, Steve 226 ClearChannel 193 Clifton-Brown, Geoffrey 21 Cliveden House, Berkshire 101, 118 Clover, Charles 10 Cobden, Richard 222 Cold War 13–15, 24, 34, 36, 133, 137, 143, 147, 148, 159 Cole, Marilyn 120 Coleridge, Samuel Taylor 244 College of Arms 82 College Valley 248 common land 213–17 Common Wealth Party 242 Commons Preservation Society 214, 232, 238 Community Infrastructure Levy 231 Community Land Trusts 287 Community Right to Buy 217, 287 Companies House 37, 41, 196 Compton Wynyates, Warwickshire 102 Conservatives, Conservative Party 20, 29, 31, 32, 39, 42, 95, 104, 105, 118, 176, 206, 209, 226, 230, 231 Constable of the Graveship of Holme 216 Corbyn, Jeremy 224 Cormack, Patrick, Heritage in Danger 104 corporate land ownership 183–7, 283–4; data concerning 187–93, 299–305; effect on housing crisis 197–203; landfill 193–7 Cory Environmental 194 Costain 10 Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) 173, 231, 276 Country Land and Business Association (CLA) 86–7, 99 and note, 100, 107, 266, 270, 278 Countryside Alliance 106 and note Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act (2000) 17, 252, 259, 288 County Durham 70–1 County Farms 178, 223, 225–6, 232 County Farms Estate 225 Cowdray Estate 117–18, 303 Cowdray, Michael Pearson, 4th Viscount 91, 118 Cowdray, Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount 117–18 CPRE see Council for the Preservation of Rural England Crag Hall estate, Peak District 41 Cranborne Chase (southern England) 50 Cranborne Manor, Dorset 103 Crichel Down, Dorset 160–3 Criminal Justice Act (1994) 25 Cripps, Stafford 243 Cromwell, Oliver 26, 52, 211, 220 crony capitalists 125–9 CRoW Act see Countryside and Rights of Way Act Crown Estate 72–3, 94, 149, 174, 265, 267, 282; background 46–8; as commercial institution 53–4; and forest law 49–51; land ownership 297, 298; and the Norman Conquest 48–9; and reorganisation of the royals’ finances 54–5; royal residences and parks 61–2; and the seabed 54 and note; Stuart and Georgian holdings 52–3; suggested merging of Duchies into 282; taxes payable 57, 58, 60; and the two Duchies 55–61 Crown Estate Act (1961) 46 The Crown (Netflix series) 88 Culden Faw, Henley-upon-Thames 131 Cunningham, Alex 55 Cunningham, John 122 Curzon, Nathaniel, 1st Marquess 240–1 Cutler, Karen 14 Dacre, Paul 131 Dahl, Roald, Danny the Champion of the World 95 Daily Express 61, 236 Daily Mail 131, 207, 208, 213, 244, 247 Daily News 99 Daily Telegraph 117, 198, 202 Dalton, Hugh 243 Darkest Hour (film, 2017) 141 Dartmoor 59, 149, 157, 248 Davidson, Duncan 131 Davies, Mary 93 Dawson, Robert 27 Debrett’s 82 Defence of the Realm (Acquisition of Land) Bill (1916) 154–5 Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) 163, 166 DEFRA see Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Delesius Investments Ltd 127 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 62 Department for the Environment 268 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) 21, 87, 261 Derby, Edward Stanley, 15th Earl 29, 41, 79 Derby, Edward Stanley, 18th Earl 101 Derby, Edward Stanley, 19th Earl 41 Deripaska, Oleg 126 ‘The Destruction of the English Country House’ (V&A exhibition, 1974) 104 Devon Great Consols 91 Devonshire, Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke 250 Devonshire, Peregrine Cavendish, 12th Duke 91, 97, 102 Dick, Philip K., The Man In The High Castle 140 Dickens, Charles: A Tale of Two Cities 112; Great Expectations 255 ‘Dig for Victory’ 33 the Diggers 78–9, 210–13, 214, 215, 216, 232 Diocesan Boards of Finance 66 Director of Public Prosecutions 34 Domesday Book (1086) 25–6, 43, 49, 64, 76, 77, 269 Domesday Office 32 Doré, Gustav 214 Dorset, Maiden Castle 59 Douglas-Home, Alec 102 Dover 235–7 Dover Immigration Removal Centre 236–7 Downe, Richard Dawnay, 12th Viscount 248n Downton Abbey (TV series) 9 Drax, Richard (Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Drax) 21 Driver, Alasdair 247, 280–1 Drove Committees 216 Dubai, Sheikh of 111 Duchy of Cornwall 55, 58–61, 149, 248, 265, 282, 298 Duchy of Lancaster 51, 55–7, 60–1, 248 and note, 265, 282, 298 Dugdale, Thomas 161 Dungeness 255 Dunn, Chido 127 Dunn, George 226 Durant-Lewis, John 158 Durham 70–1 Durham, Edward Lambton, 7th Earl 81 Dyson, Sir James 39, 130 Earl’s Court Farm Ltd 11 EarthFirst!

Ellul, Jacques-The Technological Society-Vintage Books (1964)

by

Unknown

Published 7 Jun 2012

. >37, 270 C la rk , C o lin , 8 8 ,1 0 4 C N R S , in F ran ce, 3 1 1 - 1 2 , 3 1 3 C o lb ert, Jean B aptiste, 41 co lle ctiv e incubation, 48, 59 colonialism , 1 1 8 , 1 1 9 (n e w s p a p e r), 349 com bin e, cre ated b y tech n ica l n e cessity, 15 6 com fort: in tech n ical society, 66; Combat in M id d le A g es, 6 6 - 7 com m ons, en closure of, 5 7 C om m unism , 8 1, 8a, 1 * 1 ,1 4 4 , 1 9 6 . 206, >21, 260, >66, 2 8 2 -3 , *89, a g o , 322, 365, 383, 384, 403, 420, 422; Marxism; socialism; S o viet Union C om m unist P arty, in So v iet U nion: see also an d IT R , 2 5 5 -6 ; an d L ysen k o, 315 com pass, n au tical, invention of, 38 com petition , 204; ad v erse to lib eralism , 203 com pu ter, e lectro n ic, 1 6 , 89, 16 3 , 4 2 9 -3 0 ; autom ation; cy bern etics see also concentration cam p, 1 3 1 - 2 , 2 7 2 -3 , 386, 388, 398; im posed b y technical n ecessity, 1 0 2 -3 , M ° consciousness: intervention o f, in tech n ica l operation , 20, 21; b e clo u d e d b y am usem ent tech n iques, 3 8 0 ,3 8 1 consum er research, 2 7 3 cybernetics, 4 5 , 136 , 279 n , 342, 392; autom ation; ele c tron ic c a lc u la tin g m achine cyclotron , 145 , 236 C zech oslovak ia, 382 see also D ardenne, A frica n Inquiry b y , 1 5 5 D a w e s p lan , 18 2 D .D .T ., as poison for w arm blood ed animals, 106 d ecen tralization , 199 -20 0 34 Deffontaines, Pierre, 23 n ., 76 D efo e, D aniel, 56 D e G au lle, C h arles, xi d e la M attrie, Julien O ffro y , 395 n . d em ocracy: techn ique opposed to , De CMtate Dei, 2 0 8 -18 ; p erverted b y accum ula tion o f prop agan d a techniques, 2 75 -6 ; dictatorship im itated b y , 28 8-9 ; d evalu ed b y p rop agan d a, 373 -d D en m ark, 2 4 8 ,2 6 9 depression, econ om ic, 15 1 D escartes, Rend, xiv, 4 0 ,4 3 ,5 2 determ inism , tech n ological form o f, xxxin dialectics, opposed to statistics, 206 D ickson, W . J., 305 d ictatorship: problem of, posed b y decolon ization , 123; im plied b y standardization, 2 1 3 ; politicians and techn ician s in, 2 5 6 -7 ; im i ta ted b y dem ocracy, 288-9; tech n icized sport in, 383; w orld corporation, 1 1 3 , 15 4 , 1 5 5 , 170; 235; tech n ical a n d basic sci entific research b y , 3 1 7 dissociation o f m an, 398-402 corporatism , 1 8 3 ,1 8 5 ,1 8 6 ,2 4 6 D N A , 14 3 C o rt, H en ry, 58 C o u ffign al, L o u is , 34 9 counselor, industrial, 353 C ro m w ell, O liver, 56 C ro zier, M ic h el, 3 5 3 ,4 1 9 C ru sades, 3 5 ,6 8 w ide totalitarian, 434 D id erot, D en is, 46 “ dreams, great,’ 404 D riencourt, Jacques, quoted , 286 125, D u b o in , Jacques, 1 3 7 D u cassd , Pierre, 3, 3 8 ,6 2 D uch am p , M arcel, 40 4 285; iv) INDEX Engineers and the Price System, The, v D um on t, Ren£, 108 D u p rie z, H u go , 88 E A C , 259 E a st G e rm an D em ocratic R ep ub lic, N e w W o rk C o d e in, 104 E C A , 182 econom etrics, 1 6 , 1 6 4 ,1 6 5 , 1 7 1 econom ic m an , 2 1 8 - 2 7 econom ic scien ce, 15 9 ff.; economic te c h n iq u e (s ), 22, 1 1 4 1 5 , 1 4 8 -2 2 7 secret w a ys of, 15 8 -8 3 statistics in, passim; passim; 169. 170 . 195 . 1 6 3 -5 , 196: o f observation, 1 6 3 - 7 1 ; acco un tin g in, 1 6 6 - 7 ; m eth o d o f m odels in, 1 6 7 -8 ; public-opinion analysis in, 1 6 8 -9 ; ° f action, 1 7 1 - 7 ; technique ( s ) , econom ic system s con fron ted b y see also econom y: centralized , 19 3 -2 0 0 ; authoritarian, 20 0-8 ; antidem o cratic, 2 0 8 -18 econom y o f forms, prin ciple o f; 6 7 ecstatic phenom ena, 420 and n., 4 2 1, 422, 4 2 3 ,4 2 4 ,4 2 6 educational tech n ique, 3 4 4 -9 ; p edago gy also see efficiency, as en d o f technique, 2 1 , 7 2 ,7 3 ,7 4 ,8 0 , 110 E gypt, ancient, 36, 52, 68, 70, 295 Einstein, A lb ert, 1 0 ,3 1 7 ,4 3 5 interconnec electronic banks, in yea r 2000, 432 electronic calculating m achin e, 16, see also 89, 163, 429 -30 ; mation; cybernetics Elkin, A.

…

Papin, D en is, 8 ,7 1 Pascal, Blaise, 4 1 , 7 1 Pasderm aidjan, Hrant, 249 Pasteur, Louis, 45 p ed a go gy , 22, 252; ucation al tech n ique P6guy, Charles, 223 p olitical doctrine, an d technique, 28 0-4 politicians, in con flict w ith tech nicians, 2 5 5 - 6 7 p o litics of engagem ent, 4 1 5 , 4 17 Pom bal, M arquis de, 59 pop ulation : related to technique, 48, 59; w o rld , increase o f, 328 141, 18 9 n., 2 2 2 -3 ed Penseeartificielle, La, 430 Perrin, Porter Gale, 75 Perroux, Francois, 1 6 1 , 175 , 2 1 7 personality, total integration o f, a s o bject o f tech n ique, 4 1 0 - 2 7 Peter th e G reat, 59 xiii, PhSnomenologie des Oeistes, xv Ph ilip IV , 230, 239, 284 physics: p re ced ed b y tech n iqu e, 8; n uclear, an d state, 2 3 6 Picasso, Pablo, 404 Pitt, W illiam , 56 p lan n in g, econom ic, 1 5 7 , 1 7 3 - 7 , 18 4 -9 0 19 4 , 19 5 , 2 0 1, 2 1 3 - 1 4 , 269, 270, 307; criti cize d b y Perroux, 1 7 5 , 2 17; an d lib erty, 1 7 7 - 8 3 ; econ om y, antidem ocratic passim, see oho P lato, xii, xiii, xxix Point F o u r, Trum an’s, 1 1 9 , 120, p rop agan d a, 22, 84, 9 1, 1 0 1 , 115 , 1 2 1 , 125, 2 1 6 , 2 2 1, 240, 261, 7 6 * S - , 2 8 5 -6 , 344, 36 3 -7 5; conditioned reflexes created by, 36 5 . 3 7 5 ; d u rin g w ar, 365-6; scapegoats in troduced b y , 3668; m anipulation o f subconscious 37 373 375 b y , 36 7, 369. *. ; O edipus com plex m anipulated b y , 368; critical fa c u lty sup pressed b y , 369, 370; good social conscience p rovid ed by, 369, 370; overall effects of, 3 6 9 -7 0 ; m anipulability o f mas ses as o b je ct o f, 3 7 0 - 1 ; de m ocracy devalued b y , 373-4; difference from am usem ent tech n iqu e, 3 7 5 - 6 363 n., 3 72 ». Propagandes, Prosperity and Depression, 150 Proudhon, Pierre J., 222 psychoanalysis, 14, 142, 143, 226, 2 8 s 340, 341, 344, 370; social, 3 6 8 ,3 8 7 184 Poland, 2 72 p sych ological technique, 3 2 1 , 3223 , 3 2 4 ,4 0 9 ,4 1 0 ,4 1 1 ,4 1 2 p sychom etry, 342 p o lice control, te c h n iq u e o f, i o o - l , 102, 103, 1 1 1 , 13 3 , 4 1 2 - 1 3 p sych op ed agogy, 34 6 ,34 8 p sychosom atic m edicine, 392 INDEX *) p u b lic opinion: analysis o f, 1 6 8 -9 ; a n d m orality, 30 a, o rien ted to w a r d tech n ique, 30 3, 304, 3 1 0 p u b lic relations, 3 4 1 , 3 5 1 , 373 P u ritan s, 36 rad io: im po rtan ce o f, fa p rop a g a n d a h ierarch y, 3 7 5 ; as instru m e n t o f hum an isolation, 3 7 9 D ig e s t, 3 * 3 reason, intervention b y , fa tech n ic a l operation, 2 0 -1 reciprocal su ggestion , 369 R eform ation, 3 5 ,3 8 ,3 9 , 56 R eiw ald , P ., 206 R enaissance, 3 8 ,4 1 P lato ’s, xiii R ey, A b e l, 28 Rice, Stu art A rth u r, 19 5 Richelieu, 4 1 , 284 to 178 Robin, A rm and, 3 7 1 Roethlisberger, F r itz Jules, 334 Rom e, ancient, 6 7, 77 , 12 5 ; and tech n iqu e, 2 9 -3 2 , 33. 36, 60, 125; law in, 30, 6 8 -9 , 7 1 , 7 7 , 284, 29 7 n.,- sla very in, 66, 70; ath letes of, 382, 383 R8pke, W ilhelm , 283 Rostand, Ed m on d , 223 Rousseau, Jean Jacques, xlx Russell, Bertrand, 153 Russian R evolution, 209, 322, 365 Reader's Republic, Road Serfdom, S a very, T h o m as, 8 S a vig n y, F ried rich K a rl von , 292 scholasticism , 3 5 scien ce: an d tech n iq u e, 7 - 1 1 , 43, 3 1 7 ; in an cien t C r e e c e , 28, 2 9 S cien ce T e ch n iq u e, 28 Sciencet of Man Re-establish Hie Supremacy, The, 336 scientists, n a iv e ty o f, 4 3 4 -6 Sco tt, Jerom e, 126, 3 3 4 ,3 5 5 Semainee m idicalei de Paris, 331 servo-m echanism , 14 and n., 8 8 ,2 1 7 Seym onds, A rth ur, 258 Shannon, C la u d e E ., 2 79 n.

…

. * . 26 2 , *8*. 30*. 347; a n d tech n ological un em ploy m ent, 103, 154 ; at tech n ical p ow er, 119 ; tech n ician s su p p lied b y , to un d erd evelo p ed p eop les, 1*1; concentration cam ps in, 1 3 a , 1 7 a ; statisticians in, 164; econ om ic planning b y , 73 74 > . ‘ , 189, * 1 3 - 1 4 ; d o te to syn th esis o f p olitics an d eco nomics, 19 7 ; tech n ical intel ligentsia in, *55-6; MYD in, *7* ; A ca d em y o f Sciences in, 3 1 4 - 1 5 . 43*; tem p o o f change ; trade unionism in, 357; vocational g u id a n c e in, 3 6 0 -1; n ew s fak e d in, 3 7 1 ; prop agan d a in, 3 7 1 , 3 7 3 , 3 8 *; tech n icized sport in 38*; advertising p ub lic ity in, 406; criticism p erm itted in, reason fo r, 424, 4 * 5 ; Com m unism ; M arxism; socialism 349 tee alto space, 3*8 m odified by tech n ique, Spain, *6 3 specialization, b rid g ed b y tech nique, 1 3 1 Spengler, O s w a ld , v spirituality, in tegration o f, 4 1 5 , 4i7.4i8 sport, 38 2-4 Sputnik, 1 4 5 ,3 1 7 Stakhanovism , * 2 5 ,1 4 6 ,3 4 * Stalin, Joseph, 59, 144, * 1 4 , * * 3 , * 5 4 ,2 6 0 ,2 6 2 , 290 standardization: M as quoted on, 1 1 - 1 2 ; Bertolino's v ie w of, * 1 1 , * 1 2 , * 1 3 ; authoritarian state action im plied b y , * 1 1 - 1 * state; tech n iques o f, for control o f in d ivid u al, 1 1 5 ; atom ic en ergy controlled b y , 1 5 7 , 235 ; a n d ce n tralized econom y, 1 9 3 -8 sta te (C o n tin u ed ) ancient techniques u ti lized by, * 2 9 -3 3 ; political function o f, 232; new tech niques u tilized b y, 2 3 3 -9 , 3 0 7 11; radio controlled by, 23$; and n u clear physics, 236; reaction of, to techniques elabo rated b y individuals, 2 4 3 -7 ; conjoined w ith tech n ique, *45, 246, 2 4 7; repercussions on, o f conjunction w ith technique, 2 4 7 - 9 1 ; evolution of, follow ing conjunction w ith technique, 2 4 8 - 52; as technical organism , * 5 * - 5 ; constitution o f, and tech n ique, 2 6 7-8 0 ; totalitarian, 2 8 4 -9 1 , 36 4 , 365, 384; m edical tech n iques u tilized b y , 3 8 5 -6 state capitalism , 24 5, 24 7 patriot; state-nation, 2 3 7 -8 , 26 5 statistics: in econom ic technique, 195 163 -5. 169 . 170 . . 196 ; opposed to dialectics, 206; m ass society im plied b y , a o y Steelm an rep ort ( 1 9 4 7 ) , 3 1 7 stochastics, 165, 216 Stravinsky, Igor, quoted, 129 suggestion: reciprocal, 369; masses receptive to, 4 10 "superm an,” rem ote possibility of, 337-8 "surplus v a lu e ," persistence of, in socialist regim es, 1 4 6 surrealism , 4 1 5 ,4 1 6 ,4 1 7 ,4 2 5 S w ed en , 38*, 4 *1, 422 Sw ift, Jonathan, 56 Sw itzerland, 4 2 1 ,4 2 * system ics, unknow n effects of, 108 taboos: resulting from Christi anity, 49; sociological, 49, 50, 5$ T A T , 363 taxation, 269 XU) INDEX Taylor, Frederick W inslow, 133, 264, 350 T aylo rism , >46, 336 T ch akotin, Serge, 84, 3 4 1 , 365 technical anesthesia, 4 1 2 - 1 5 tech n ical autom atism , 79 -111; defined, 80; an d capitalism , 8 1-2 tech n ical civilization , defined, 1 2 7 -8 tech n ical com plex, form ation o f, 4 7 tech n ical consciousness, 5 7 , 58, 59, 1 2 6 ,1 2 7 tech n ica l co n vergen ce, 3 g i , 392 tech n ical in telligentsia, in Soviet U nion, 2 5 5 -6 technical intention, 60; defined, 52 tech n ical operation, 19, 20, 2 1 tech n ical organism , developm en t o f state into, 2 5 2 -5 tech n ical phenom enon, 19, 20, 2 1, 22, 5 2 , 63, 6 9 , 85; present aspect of, 61, 62, 78; rational process in, 7 8 -9 ; artificiality of, 79; lim itless progress open for, 90; m onism of, 9 4 - 1 1 1 , 195; im personality of, 3 8 7; m a c h in e ( s ); tec h n iq u e(s) techn ical universalism , 116 -3 3 , *uG, 355 tech n ician s: in conflict w ith p o li tician s, 2 5 5 -6 7; as n e w elite, 275; as specialists, 389; and m y th o f a b stra ct M an, 390; un aw are of tech n ical con vergen ce, 3 9 1 te c h n iq u e (s ): definitions o f , v i viii, x, xviii, xix, x x v -x x v i, xxviii, xxxvi, 1 3 - 1 8 , 19; an d m achines, 3 - 1 1 , 42, 242; an d science, see also 45 7 -11. , 3 1 7 ; o f organ ization , 1 1 - 1 3 , 2 1 . 22; U N E S C O C o l loquium on, 17; efficien cy as e n d o f, 2 i, 72, 73, 74, 80, 110 ; econom ic, econ om ic techn iq u e ( s ) ; hum an , hum an see see tech n ique (C o n tin ued ) tech n iq u e (s ); prim itive, 3 3 - 7 , 63; an d an cien t G reece, 2 7 - 9 , 33, 44, 45; and ancient Rom e, 2 9 -3 2 . 33. 36, 60, 125; an d C h ristian ity, 3 2 -8 ; in sixteenth cen tu ry, 38 -4 2 ; an d Industrial R evolution, 4 2 -6 0 in tellectu al, 4 3, 1 16 ; in eigh teenth cen tu ry, 44, 4 5 , 46, 4 7, 52; in n ineteenth century, 44, 45, 4 7, passim; 1 1 2 ; population related to, 48, 59; involved w ith , 5 3 - 4 , 1 4 4 -5 ; masses con verted to , 5 4 - 5 ; agricultural, 57, 104, 105, 108, 1 16 , 1 5 1 - 2 , 274 ; fiv e facto rs in grow th o f, sum m ary o f, 5 9 - 6 o ; ch aracterology o f, 6 1-14 7 traditional, and so ciety, 6 4 - 7 7 ; in civilization , 6 4 - 7 9 ; instrum ental, 67; a b s tra ct, 7 1, 73; slo w evolution o f, 7 1-2 ; characteristics o f m o d em , 7 7 - 1 4 7 ; and autom a tism o f tech n ical ch o ice, 7 9 —85; political, 83, 84, 136 s ta te ); m ilitary, 83, 229-30; self-augm entation o f, 8 5-9 4 ; geom etric progression in selfaugm entation of, 89, 9 1; inter d epen d en ce and com binations o f, 9 1 , 1 1 1 - 1 6 ; monism of, 9 4 1 1 1 ; m oral judgm ents n o t o b served b y , 9 7, 134; necessity as ch aracteristic o f, 99, 1 1 1 - 1 6 ; o f p o lice control, 1 0 0 -1, 102, 103, 1 1 1 , 133, 4 1 2 - 1 3 ; unfore seeability o f secon dary effects o f, 1 0 5 - 1 1 ; com m ercial, 1 1 2 13; transportational, 113 ; fi nancial, 1 1 3 , 2 3 0 - 1 ,2 4 4 - 5 ; city planning, 1 13 , 237, 270; o f am usem ent, 1 1 3 - 1 4 , 1 15 , 3 7 5 82; o f state, fo r control o f individual, 1 1 5 s ta te ); universalism of. 1 1 6 - 3 3 , 206, bourgeoisie passim; (see also (see also (xiii Index Continued) tech n iqu e ( 35 5; cu ltural b rea k d o w n pro voked by, 1 2 1 , 122, 12 3 , 124, 126, 130; literature subordi nated to, 128; art subordinated to, 128, 129, 404; o f operational research , 129 , 1 7 3 ; fo r “ ob jective” m usic, 129 -3 0 ; special ization brid g ed b y , 132; au tonom y o f, 1 3 3 -4 7 ; hum an b ein g subservient to, 1 3 7 -9 , 3 0 6 -7, 340; w orship o f, 1 4 3 -6 , 3 0 2 -3 , 324; a n d econom y, econom ic man; econom ic science; econom ic te c h n iq u e (s ); econom ic system s confronted b y , 183-90 ; h opes o f progress aw ak en ed b y , 1 9 0 -3 ; centrali zation p resupposed by, 1 9 3 -4 ; as facto r in d estruction o f capitalism , 198 , 2 3 6 - 7 ; op posed to liberalism , 2 0 0 -5 ; o p posed to d em ocracy, 2 0 8 -18 ; an d econom ic m an , 2 1 8 -2 7 ; ancient, u tilized b y state, 2 2 9 33; adm inistrative, 2 3 1 - 2 ; new, u tilize d b y state, 2 3 3 -9 , 3 0 7 1 1 ; p rivate an d p u blic, 2 3 9 43, 3 0 0 -1; conjoined w ith state, 245, 246, 247; an d reper cussions on state, 2 4 7 - 9 1 ; and state constitution, 2 6 7-8 0 ; and p o litical doctrines, 28 0 -4 ; judicial, 2 9 1-3 0 0 ( la w ); repercussions on, 300—18; no counterbalance to, 3 0 1 - 7 ; in stitutions in service o f, 3 1 1 - 1 8 ; a n d hum an tension, 3 1 9 -2 5 ; psych ological, 321, 3 2 2 -3 , 324, 409, 410 , 4 1 1 , 4 1 2 p sych oa n alysis); m ilieu an d space m odified b y , 325— 8; tim e and m otion m odified b y , 3 2 8 -32; an d hum anism , see see also (see also 336 . 337, 338 , 339 , 34 ° , 348 , 350, 409; education al, 3 4 4 -9 Continued) (see also p e d a g o g y ); tech n iqu e ( 3 4 9 -5 8 ; of hum an o f work, relations, 3 5 4 -6 ; m edical, 3 8 4 -7 ; special ized , efficiency of, 388, 389; hum an dissociation p rod uced by, 398 -40 2; initiative censored by, 420; and ecstatic phenom ena, 4 2 1 , 422, 4 23, 424; revolt integrated by, 4 2 5-6 , 427; future of, 428—36; economic technique (s ) ; hum an te c h n iq u e (s ); states; technical phenom ena technocracy, 336 tech n ological un em ploym en t, 10 3 -4 see also television: artificial paradise cre ated b y , 377; a s m eans o f es ca p e, 3 7 8 -9 ; as destroyer of personality and hum an relations, 380 329 n. tension, hum an, 3 1 9 - 2 5 Temps harcelant, Le, T h em atic A pp ercep tion T est, 363 Tib etans, 76, 12 1 T illich , Paul, xi time, m odified b y tech n ique, 328 - 30 tools: and skill o f w o rk er, 67, 68; co n q u est belon gin g to, 146 totalitarian sta te, 2 8 4 -9 1 , 364, 365. 384 T o yn b ee, Arnold, 1 1 , 1 2 , 2 1 trace elem ents, an d soil conser vation, 339 tra d e unionism, 3 5 7 -8 on 327 Treatise Bread, Trum an, H arry S , 1 1 9 , 120, 184 trusts, 202, 235 “ truth serum ," 385 T u rk ey, 123 T V A , 108, unconscious, 4 0 2 -5 182, 2 6 5 , 323, 324 th e, trium ph of, xiv) INDEX u n d erd evelo p ed p eop les, 1 1 7 , 1x8, 1 2 0 , 1 2 1 ,1 2 2 ,1 2 3 u n em ploym en t, tech n ological, 1 0 3 -4 U N E S C O , 1 7 , 1 2 1 , 12 3 , 346, 361 unionism , labor, 3 5 7 - 8 U n ite d States, 10 7 , 108, 1 1 9 , 147, 196, 235, 252, 263, 284, 286, 326 , 347; invention in ( 1 7 5 0 > 8 50 ), 52; as tech n ical p ow er, 1 1 9 ; technicians supplied b y , to u n d erd evelo p ed p eop les, 120; crash program s in, to re co n stru ct soil, 14 3 ; concentra tio n o f ca p ita l in, 15 4 , 15 5 ; overproduction in, 156 ; statis ticians in, 16 4 ; econ o m ic p lan ning in, 184, 270; B ureau o f th e B u d g et in, 19 5 ; and synthe sis o f p olitics an d econom ics, 19 7; p olitical technicians in, * 5 8 -9 ; antitrust la w s in, 266; F B I in, 272; sales en gin eerin g in, 1 7 3 ; in a b ility o f, to p a y for co m plete disarm am ent, 277; lobbyists in , 278; Japan o ccupied b y , 282; scien tific research in, 3 1 5 . 316 . 3 1 7 ; la rge-sca le a g ricu ltu re in, 339 ; tem p o o f ch a n ge in, 349; labor unionism in, 357; p ostw ar neuroses in, 369, 370; and p rop ag an d a, 372 37 3 . 374!

The Debian Administrator's Handbook, Debian Wheezy From Discovery to Mastery

by

Raphaal Hertzog

and

Roland Mas

Published 24 Dec 2013

People in charge of those areas are free to drive their own boat. As long as they keep up with the quality requirements agreed upon by the community, no one can tell them what to do or how to do their job. If you want to have a say on how something is done in Debian, you need to put yourself on the line and be ready to take the job on your shoulders. This peculiar form of meritocracy — which we sometimes call do-ocracy — is very empowering for contributors. Anyone with enough skills, time, and motivation can have a real impact on the direction the project is taking. This is testified by a population of about 1 000 official members of the Debian Project, and several thousands of contributors world-wide.

…

Even if this constitution establishes a semblance of democracy, the daily reality is quite different: Debian naturally follows the free software rules of the do-ocracy: the one who does things gets to decide how to do them. A lot of time can be wasted debating the respective merits of various ways to approach a problem; the chosen solution will be the first one that is both functional and satisfying… which will come out of the time that a competent person did put into it. This is the only way to earn one's stripes: do something useful and show that one has worked well. Many Debian “administrative” teams operate by appointment, preferring volunteers who have already effectively contributed and proved their competence.

…

This method is practical, because the most of the work these teams do is public, therefore, accessible to any interested developer. This is why Debian is often described as a “meritocracy”. CULTURE Meritocracy, the reign of knowledge Meritocracy is a form of government in which authority is exercised by those with the greatest merit. For Debian, merit is a measure of competence, which is, itself, assessed by observation of past actions by one or more others within the project (Stefano Zacchiroli, the previous project leader, speaks of “do-ocracy”, meaning “power to those who get things done”). Their simple existence proves a certain level of competence; their achievements generally being free software, with available source code, which can easily be reviewed by peers to assess their quality.

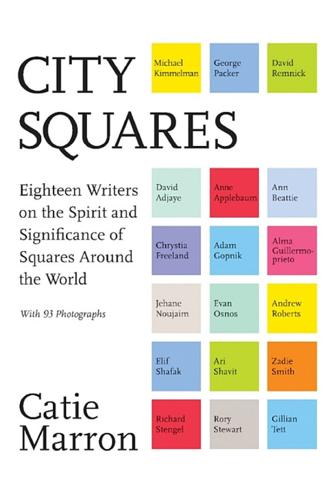

City Squares: Eighteen Writers on the Spirit and Significance of Squares Around the World

by

Catie Marron

Published 11 Apr 2016

Russian history, which spans a thousand years of autocracy and totalitarianism, could not be overcome quite so easily. The pursuit of both democratic politics and a free market in the 1990s was so chaotic, so untethered from a legal structure, so riddled by greed and corruption, that Russians came to scoff at the word demokratia and use the derisive dermokratiya (“shit-ocracy”). Putinism is the nationalist-authoritarian reaction to those years. But even while the regime is said to be enormously popular (thanks in large part to the state’s grip on television and, increasingly, the Internet), the urge toward the public square does not fade. In January 2012, as an anti-Kremlin, anti-corruption movement was brewing in Moscow, eight members of the radical-feminist anti-Putin collective known as Pussy Riot, wearing identity-concealing balaclavas, climbed Lobnoye Mesto, chanted, “Putin is scared shitless,” and began singing their song “Raze the Pavement!”

…

For Palestinian refugees, the creation of any urban amenity, by implying normalcy and permanence, undermines their fundamental self-image, even after several generations have passed, as temporary occupants of the camps, preserving the right of return to Israel. Moreover, in refugee camps, public and private do not really exist as they do elsewhere. There is, strictly speaking, no private property in the camps. Refugees do not own their homes. Streets are not municipal properties, as they are in cities, because refugees are not citizens of their host countries, and the camp is not really a city. The legal notion of a refugee camp, according to the United Nations, is a temporary site for displaced, stateless individuals, not a civic body.

…

They are not marching on the Pentagon, or surrounding Westminster, or massing at the Knesset. All they are doing is gathering at the foot of the terrace of an unimportant municipal building in a square demarcated by nondescript residential blocks. All they are doing is standing on the beige granulite tiles and waiting for the helicopters from the evening news to document them and estimate their number and report that Rabin Square is again overflowing with protesters. Even when they come out in anguish, their anguish has no address. They do not expect to be heard. This is why they gather in a banal plaza, surrounded by banal buildings, and shout out banal exclamations against a banal political adversary whose hold on power is tenuous at best.

Sexual Intelligence: What We Really Want From Sex and How to Get It

by

Marty Klein

Published 7 Feb 2012

If we choose, a good therapist or physician can investigate a patient’s life and often uncover the logic (conscious or unconscious) that makes sense of these “symptoms”: trauma, fear of abandonment, insecurity about masculinity, fear of intimacy—the whole Oprah-ocracy of inner torment we regularly see. Given America’s twisted sexual culture, if we’re looking for stuff like that, we can almost always find it. Then, theoretically, we help our patients resolve it, the blocks to sexual function dissolve, and their genitalia are rescued from the ash heap of history. Good-bye, sexual “dysfunction.” Whether that’s the best we can do for our patients is another matter. I’m not so eager to agree that I’ll work with a patient to fix presenting problems like unreliable erections and discouraged vaginas.

…

But this was no time for indulging my curiosity—alas, there never is. “Why do you want to bring her in?” “So you can explain what we’ve discussed, and she can understand that I’m not just being a pussy.” “You have to do that,” I said. “You don’t need me, and you shouldn’t have me do it.” “Why?” “Because part of growing up is sitting her down and telling her exactly who you are right now. It’s time to reach out to her and for you to lead the two of you through things collaboratively. You can do it.” “It’s easier if you do it.” “Yes, you’re right. But this isn’t about doing what’s easier. Sometimes sex is a vehicle for growing up, which is never the easiest option.

…

There’s so much mystery integral to our sexuality, so much romance in getting to know a new body and a new person (or enjoying familiar things we’ve learned to expect), that we really don’t need to add more of either one by hesitating to communicate, plan, or acknowledge what we’re doing. I believe that when people say they want sex to be spontaneous, they’re thinking one or more of the following: • I don’t want to think about what I’m doing. • I don’t want to think about the consequences of what I’m doing. • I don’t want to be that close to the person I’m doing this with. • I’m concerned that if either of us thinks about this, we won’t do it. • I’m concerned that talking about what we’re doing will make it less interesting. • I’m concerned that if I think too much about it my body won’t “function.”

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by

Philip Mirowski

Published 24 Jun 2013

“A Long Strange Trip: The State and Mortgage Securitization, 1968–2010,” in Preda and Knorr-Cetina, Handbook of the Sociology of Finance. Flitter, Emily, Kristina Cooke, and Pedro DaCosta. “For Some Professors, Disclosure Is Academic,” Reuters special report, 2010, at http://link.reuters.com/heq72q. Foer, Franklin. “Nudge-ocracy,” New Republic, May 6, 2009. Fontaine, Philippe. “Blood, Politics and Social Science,” Isis 93 (2002): 401–34. Forrester, Katrina. “Tocqueville Anticipated Me,” London Review of Books, April 26, 2012. Foucart, Stephane. “When Science Is Hidden Behind a Smokescreen,” Guardian Weekly, June 28, 2011.

…

The dividing line between the postwar generation of neoclassical economists and the post-1980 cohort is that the former believed they could abjure all dependence on academic psychology, whereas the latter believed they could pick and choose among psychological doctrines to elevate those that seemingly reinforced the neoclassical orthodoxy. 52 Foer, “Nudge-ocracy.” 53 Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny, “Neglected Risks, Financial Innovation and Financial Fragility.” Of course, since this is an orthodox model, fluctuations are relative to a rational-expectations equilibrium, and not of employment, income, and output. This is compounded by the fact that rational-expectations forecasts of identical agents are replaced by identical inaccurate forecasts.

…

In the Samuelsonian synthesis, one must count on the government to ensure more or less full employment; only once that can be taken as given do the usual virtues of free markets come to the fore. It’s a deeply reasonable approach—but it’s also intellectually unstable. For it requires some strategic inconsistency in how you think about the economy. When you’re doing micro, you assume rational individuals and rapidly clearing markets; when you’re doing macro, frictions and ad hoc behavioral assumptions are essential. So what? Inconsistency in the pursuit of useful guidance is no vice.29 I do not wish to suggest one should never, ever simultaneously entertain A and Not-A.

Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism

by

Robin Chase

Published 14 May 2015

Chris placed his experience with Jordi in a broader context, telling me, “In the 21st century, it matters less and less where you live, how old you are, what school you went to (or didn’t), or where you’ve worked. All that matters is what you can do; online innovation communities are the ultimate ‘do-ocracies.’ ” How we uncover our personal strengths is transformed. Gretchen’s parents weighed in on her early career options. Many people don’t feel like they have many options; others may make a choice but change their minds later in light of new life circumstances. Others might be like me. When I was just starting to work, it took me years to figure out what I liked to do and what I was good at. I hated my first job, and my second as well. But my mother wouldn’t let me quit right away.

…

“Thinking fast” is what we usually do. He argues that humans are great at fast pattern recognition, recognizing subtle local cues and context, and adjusting immediately to take these into account. Conversely, computers are pretty terrible at these things. While we have to trick ourselves into “thinking slow,” taking the time to make the mathematical and rational calculations, this type of analysis is easy for computers. The optimal Peers Inc platforms allow computers to do what they do best—complex and not-so-complex math—and deliver the results to people, allowing us to engage in what we do best: creativity, pattern recognition, and contextualizing.

…

They have given up the right to manage the projects they are paying for, and their competitors have immediate access to everything they do. It’s not IBM’s product.17 Doc Searls, senior editor of Linux Journal, says: “Dan Frye, who runs systems development at IBM and employs many Linux kernel hackers, once told me it took six years for the company to learn that it couldn’t tell those hackers what to do—and that in fact the situation was reversed: The kernel hackers were really the ones in charge. This is not a matter of governance, but of authority, influence, and constructive working-together in which all parties contribute what they are in the best position to contribute. The kernel hackers, as peers, do what they do best, while IBM, as an Inc, does what it does best.

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by

Nathan Schneider

Published 10 Sep 2018

On a windy day in May, gusts swelled through the unMonastery’s first-floor caves, blowing from the walls various colored sticky notes and hand-drawn posters made in meetings heady with excitement and hope. They were schedules, sets of principles, slogans to remember, lists of things to do. A maxim for the Edgeryders’ doctrine of do-ocracy, for instance: “Who does the work calls the shots.” These relics remained on the floor for hours, apparently provoking insufficient motivation to pick them up. There had been a kind of monastic routine at the unMonastery in the first weeks. At specified times, the group would sit in circles to share feelings and discuss concerns.

…

But once I run into public platforms, once I need to connect with others and do things together, it’s over. I’m stuck. This is where my personal piety doesn’t help. If I want to do slow computing over networks, sensitive to the communities and value chains I’m interacting with, I need platform cooperativism. I need platform co-ops. There are too few of them. Most that do exist are still getting their start. Except for a few cases here and there, in a few parts of the world, life in the platform co-op stack remains mostly a feat of imagination, a possible future based on projects of the present that may or may not succeed. As some do, it will be easier for more to as well.

…

Co-ops tend to take hold when the order of things is in flux, when people have to figure out how to do what no one will do for them. Farmers had to get their own electricity when investors wouldn’t bring it; small hardware stores organized co-ops to compete with big boxes before buying local was in fashion. Before employers and governments offered insurance, people set it up for themselves. Co-ops have served as test runs for the social contracts that may later be taken for granted, and they’re doing so again. This book is a sojourn among the frontiers of cooperation, past and present—cooperation not in the general sense of playing nice, but in the particular sense of businesses truly accountable to those they claim to serve.

Why It's Still Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions

by

Paul Mason

Published 30 Sep 2013

The historian Allan Nevins argued that by the late 1850s America contained no longer just two political factions, or parallel economic systems, but ‘two peoples’ who were culturally, socially and ethnically different (by this time 90 per cent of all European migrants were headed for the north). Another historian, James McPherson, explained why, to the white slave-ocracy and its plebeian supporters, the rise of industrial capitalism and its liberal values did look like a revolution: The ascension to power of the Republican Party, with its ideology of competitive, egalitarian, free-labor capitalism, was a signal to the South that the Northern majority had turned irrevocably towards this frightening, revolutionary future.9 While it would be wrong to force an analogy, there are worrying echoes of 1850s America in today’s USA.

…

Now they sleep, dad and daughter, side by side with eighty people they do not know. ‘It’s not bad,’ says Michelle. ‘It’s safe; I stay at school till six o’clock to get my homework done.’ Do they know she’s homeless? ‘I didn’t tell them.’ Why not? ‘They didn’t ask.’ This means she does not show up on New Mexico’s register of homeless children, which already numbers 5,500. She’s trying to keep her Latin dance class going; Larry is still working on his screenplay ‘about a biker who gets accused of doing something he didn’t do’. His eyes drift towards some inner memory, and Michelle smiles. Larry says: The job market was supposed to make progress a little in May, but it levelled off and now it’s dropped back.

…

By contrast, May 1968 looks less like a wave of revolutions and more like a surge of protest: students in the lead, workers and the urban poor taking it to the verge of insurrection only in France, Czechoslovakia and America’s ghettoes. Nineteen eighty-nine was—with the exception of Romania—achieved by demonstrations, passive resistance and a large amount of diplomacy. In each of these global spasms, issues of class were crucial. The key questions were always: what do the workers do? Do they lead? What is their ideology? How fast do they move from a democratic to a social agenda? How does the middle class react? But these worldwide protests were not only about class. With the rise of social micro-history, we’ve begun to understand that these events were also about ‘the personal’: about relationships, freedom of action, culture, the creation of small islands of autonomy and control.

The Art of Community: Building the New Age of Participation

by

Jono Bacon

Published 1 Aug 2009

The direction for the Drupal Association is set by its board of directors, of which I’m president. It is not always easy, but we elect the board of directors such that they represent the different aspects of our community. By doing so, we make sure that the Drupal Association serves the needs of the community, and not the other way around. What makes the Drupal Association special is that it has no influence over the technical direction of Drupal. The Drupal community uses a do-ocracy model, meaning people work on what they want to work on, instead of being told what to work on. Decisions are usually made through consensus building and based on technical merit, trust, and respect.

…

Consider the rebuilding of Europe after World Wars I and II, expanding the right to vote, equal access to public accommodations, reducing disease, reducing workplace discrimination, legislation around safe food and drinking water, the nationwide construction of highways, financial security in retirement, scientific funding and technical research, reducing hunger and improving nutrition, space exploration, and more. It is government that helped forward these worthy achievements. When the system works, beautiful things can happen. orm-interview-snippet: The Community Case Book The Drupal community uses a do-ocracy model, meaning people work on what they want to work on, instead of being told what to work on. Decisions are usually made through consensus building and based on technical merit, trust, and respect. As the project lead, and with the help of my co-maintainers, I help guide the community in strategic directions.

…

How can you ensure an easy flow of ideas and progress between two teams who focus on different parts of the community? How does your art team communicate well with your development team? This opens up a huge array of questions. Even with the three teams in Figure 2-4, how do they communicate? What mediums do they use? How do they deal with geographic and time zone issues? How do they report their interactions to the wider community? How do they track progress? How do we understand how different teams work together? Not an easy problem to solve. These questions are not merely about how two or three teams communicate. They get to the heart of the ethos of the community as a whole: the standard for how teams are structured, how they behave, and how they communicate.

Habeas Data: Privacy vs. The Rise of Surveillance Tech

by

Cyrus Farivar

Published 7 May 2018

Hofer, frustrated, tried to point out that their street theater efforts were unlikely to result in meaningful change. Still, Katz asked Hofer a few basic questions: “Do you want to meet with the city council? How can you not, with the people voting on the project? What’s your strategy?” Katz impressed upon him the motto of Sudoroom and other hacker-spaces like it: it’s an anarchist collective, yes, but it’s also a do-ocracy. If you want something done, do it. Hofer decided to take him up on the offer. Amazingly, it worked. Within weeks, Hofer, who had no political connections whatsoever, had meetings scheduled with city council members and other local organizations.

…

One March 2017 article in McClatchy noted that the body “barely functions.” The White House seems wholly uninterested in reviving it. But the law is on the books for any administration—Republican or Democrat—to bring it back. After all, doing something is better than doing nothing. Back in Oakland, Saied Karamooz articulated what many legislators should take to heart: “Do you think people have the time to protect their privacy? They don’t even know that they’ve been violated—doing nothing is admitting defeat.” NOTES The fantastic advances: Lopez v. United States, 373 U.S. 427 (1963). I just hate Fourth: Justice Antonin Scalia, interview with Susan Swain, C-SPAN, June 19, 2009.

…

As far as he knew, this little law was mostly used for courts to obtain procedural results—transporting a prisoner from one place to another, for example—but not to order a company to provide sophisticated technical assistance beyond what it would normally do during its course of business. “It was extraordinary and unheard of, the kind of order they had obtained,” he told me, calling the order “offensive” to Apple. “We never said the company couldn’t do it and didn’t have the ability or the resources to do it, that wasn’t the hardship. It was the threats that it would cause and it was an anathema to the company and the consumers.” Wilkinson and her DOJ colleagues were cordial, but aggressive.

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Story of Anonymous

by

Gabriella Coleman

Published 4 Nov 2014

The mask, which has become its signature icon, functions as a eternal beacon, broadcasting the overriding value of equality, even in the face of bitter divisions and inequalities. Of course, despite the lack of a stable hierarchy or a single point of control, some Anons are more active and influential than others—at least for limited periods. Anonymous abides by a particular strain of what geeks call “do-ocracy,” with motivated individuals (or those with free time) extending its networked architecture by contributing time, labor, and attention to an existing enterprise or by starting their own as they see fit. Whether a movement even fesses up to the existence of soft leaders is a whole other important question intimately related to another issue plaguing many social movement: how to keep the membranes permeable/osmotic enough so newcomers can join existing working groups, whose tendency is to become cliquish; without overt recognition that leadership exists, a project can fall easily into the “tyranny of structurelessness”—a situation whereby the vocalizing of an ideology of decentralization works as a platitude that obscures or redirects attention away from firmly entrenched but hidden nodes of power behind the scenes.17 Following the heated controversy that erupted on Why We Protest, many Anons came to accept that marblecake played a valuable organizational role.

…

We ask, why is a news source like AlJazeera one of the few covering these earth shaking riots while the rest remain quiet? The world is getting the impression that unless western economic interests are involved, our media does not care to report upon it. Perhaps you didn’t know? Now that you do, you can help us spread the news. After all, you do not have to wear a mask to do it. Sincerely, Anonymous12 “Dudes believe me the key of this is having no ego” But Anonymous was doing more than pestering the mainstream media to do its job. By January 2, 2011, a technical team on #internetfeds forsook their holidays to work nearly nonstop for two weeks. Indeed, Adnon told me he barely slept for two weeks. During an interview, he explained that the operation took a different approach than Avenge Assange and Operation Payback: Adnon: With Tunisia we had a plan Adnon: We thought carefully about what to do and when in a small group Adnon: presented a list of options in a poll Adnon: then took the result of the poll Adnon: It was much less a big group decision than other ops OpTunisia marked, both internally and externally, a sea change.

…

Hoglund then changes tack, appealing to Anonymous’ supposed sense of self-preservation: greg: do you guys realize that attacking a U.S. company and stealing private data is something you have never done before? greg: no, I think you might have considered your public reputation - it doesn’t look good. Agamemnon: Greg. Please answer: do you understand who we are and why we do what we do? CogAnon: I was never going to sell u have it wrong. evilworks: we don’t CARE about reputation Sabu: greg, our reputation is not at stake here. yours is. greg: i mean this was a real hack - and btw, i have to concede you really did hack us good evilworks: we do what we think is right c0s: Greg, and the people here dont care about reputation, at all evilworks: there are numerous ways to make us look bad evilworks: we dont care […] Baas: Granted, you guys don’t do burn notices proper…But it’s the thought that counts.

Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know

by

P. W. Singer

and

Allan Friedman

Published 3 Jan 2014

.… We have this agenda that we all agree on and we all coordinate and act, but all act independently toward it, without any want for recognition. We just want to get something that we feel is important done.” With no single leader or central control authority, the group visualizes itself not as a democracy or a bureaucracy, but as a “do-ocracy.” Members communicate via various forums and Internet Relay Chat (IRC) networks to debate potential causes to support and identify targets and actions to carry out. If enough of a collective is on board for action, a date will be selected and plan put into action; one member described it as “ultra-coordinated motherfuckery.”

…

Approach It as a Public-Private Problem: How Do We Better Coordinate Defense? Exercise Is Good for You: How Can We Better Prepare for Cyber Incidents? Build Cybersecurity Incentives: Why Should I Do What You Want? Learn to Share: How Can We Better Collaborate on Information? Demand Disclosure: What Is the Role of Transparency? Get “Vigorous” about Responsibility: How Can We Create Accountability for Security? Find the IT Crowd: How Do We Solve the Cyber People Problem? Do Your Part: How Can I Protect Myself (and the Internet)? CONCLUSIONS Where Is Cybersecurity Headed Next? What Do I Really Need to Know in the End?

…

Why Is There a Cybersecurity Knowledge Gap, and Why Does It Matter? How Did You Write the Book and What Do You Hope to Accomplish? PART I HOW IT ALL WORKS The World Wide What? Defining Cyberspace Where Did This “Cyber Stuff” Come from Anyway? A Short History of the Internet How Does the Internet Actually Work? Who Runs It? Understanding Internet Governance On the Internet, How Do They Know Whether You Are a Dog? Identity and Authentication What Do We Mean by “Security” Anyway? What Are the Threats? One Phish, Two Phish, Red Phish, Cyber Phish: What Are Vulnerabilities? How Do We Trust in Cyberspace? Focus: What Happened in WikiLeaks?

Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing

by

Ted Conover

Published 20 Jan 2010

Two iron rings had been fastened to the wall; hanging nearby were a number of the whips, known as the cat-o’-nine-tails, and—according to one inmate account—a gag. The inmate was stripped, his hands were tied to the rings, and then, to use a modern phrase, it was payback time: The keeper he had offended administered blows to his back. Levi Burr, an inmate imprisoned for perjury, published a detailed memoir in 1833. Sing Sing, he charged, was a “cat-ocracy.” The cat-o’-nine-tails was generally made of six strands of hard, waxed cord, sometimes metal-tipped, that were attached to a hickory handle about a foot and a half long. The cords were “almost as hard as a piece of wire,” Burr wrote. While Beaumont had speculated that the fear of upsetting the inmate population would make keepers moderate in their use of the cat, Burr wrote, It would be an endless task to attempt to enumerate the many applications of this instrument of discipline, or tell the number of blows that are generally applied at one flogging, as they vary according to the will and temper that the keeper happens to be in at the time.

…

Forget running a gate or being an escort or doing construction supervision or transportation or manning a wall tower—a good robot might almost do those. The real action was on the gallery looking after inmates. To do this job well you had to be fearless, know how to talk to people, have thick skin and a high tolerance for stress. Nigro had told us that whenever prison administrators wanted to know what was really going on in a prison, what the mood of the inmates was, they asked the gallery officers. We were like cops on a beat, the guys who knew the local players, the ones who saw it all. I thought I could do it. I wanted to do it, to satisfy myself that the toughest job was not beyond my capacity.

…

He himself had finished his training just a few weeks before, he would tell me later in the day, and did not have much experience on the galleries. He was, I would ascertain, not especially smart, and his slow wits and mild manner were no match for the chaos swirling around him. I watched helplessly, awaiting further direction. “What do we do now?” I finally asked. “Get them into their cells,” said Fay. “And how do we do that?” “You just tell ’em,” said Fay. “Why don’t you take that side”—he gestured to W gallery—“and I’ll take this.” I took about five steps and looked both ways down W. It was 425 feet long and three and a half feet wide. At the exact center of it was the staircase, where I stood.

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by

Kelly Weinersmith

and

Zach Weinersmith

Published 6 Nov 2023

The KFC employees attempting to set up a lunar chicken-ocracy still have to launch from somewhere and be from somewhere. So if they go to the Moon and claim sovereignty, they’re doing it under the jurisdiction of some nation. Also, just as a matter of common sense, the law couldn’t permit this sort of thing because it would make Article II pointless. Try to imagine how the international community would feel if the United States gave $10 trillion to Kentucky Fried Chicken to claim all of Mars. They’d be finger lickin’ pissed. More important, they would refuse to recognize the land title the US government granted to KFC. What you can do is set up a research station where your sovereign law applies, similar to how nations have sovereignty over their ships at sea.

…

Space law is too slow and nobody agrees on the path forward, so we should just pass national rules, try to get friendly nations to agree to go along with them, and do our thing. The problem as we see it is that doing our thing may involve quasi-territorial claims that push the interpretation of international law to its limits. Most worrisome, this decision to rush headlong into crisis might be taken even if there’s no good economic or military reason to do it. Zach once talked to some international security scholars about why nations do things that make no sense. His specific question was about something called helium-3, which is a substance several governments, companies, and space agencies say they will mine from the Moon for its economic value.

…

OceanofPDF.com Part I Caring for the Spacefaring If you are a space settler, and the goal is to have a large population in space, one of the best things you can do is not die. Or, if you’re planning to die, don’t do it right away. If you can swing it, have a few kids, raise them to reproductive age, then go gentle into that good night. We don’t know how to do this. Not really, anyway. Humans have been in space for over sixty years now and we do know plenty about what astronauts experience. But astronauts aren’t normal people. To be frank, they’re better than us. Although this is changing a little as the era of space tourism permits the schlubby among us to reach orbit, the average astronaut is someone who combines deep specialist skills with the ability to pass a battery of physical and mental tests that most of us would bail on in a few days.

Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time

by

James Suzman

Published 2 Sep 2020

Besides the many who through history have died while ‘trying to save the farm’, there are the countless souls who were worked to death under whips held by others: the slaves that ancient Romans dispatched to their mines and quarries; the descendants of the men and women stolen from Africa who led hard, abbreviated and brutalised lives in the cotton and sugar plantations of the Americas; the tens of millions who perished in twentieth-century gulags, labour colonies, prisons and concentration camps as a result of committing crimes or finding themselves on the wrong side of one or another -ocracy, -ism or ego; and those who, like the rubber harvesters in King Leopold’s Congo or along the Putamoyo River in Colombia at the turn of the twentieth century, were viewed as little more than a disposable mass of cheap labourers. But what makes the individual stories of karoshi and karo jisatsu different from these is the fact that what drove the likes of Miwa Sado to lose or take their lives was not the risk of hardship or poverty but their own ambitions refracted through the expectations of their employers.

…

In much the same way that John Lubbock considered careful scientific research and writing lengthy monographs to be leisure, for many of us the only distinction between work and leisure is whether we are paid to do an activity or whether we are doing it by choice – and, often enough, actually paying cash earned in regular jobs to do it. Taking into account time spent getting to and from the workplace and doing essential household activities like shopping, housework and childcare, working a standard forty-hour week does not leave a great deal of time for leisure. Unsurprisingly, most people in full-time employment use the bulk of their pure leisure time for restful, passive activities like watching TV.

…

But unlike in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, most employees have weekends to themselves as well as several weeks of paid annual vacation. And many people choose not to spend these precious hours resting but instead use them for doing work of their choice. Beyond those who disappear into computer games (which often involve activities that mimic actual work), many of the most popular hobbies people choose to spend their free time on involve doing forms of work that in the past we might have been paid to do or that other people are still paid to do. Thus while fishing and hunting were work for the foragers, they are now expensive but very popular leisure activities; where growing vegetables or gardening was viewed as odious labour by farmers, for many it is now a deeply satisfying form of pleasure; and where sewing, knitting, pottery and painting were once a source of much needed income, people now find peace in their relaxing, often repetitive rhythms.

Autonomia: Post-Political Politics 2007

by

Sylvere Lotringer, Christian Marazzi

Published 2 Aug 2005

; b) the process of liberation is not first "political" and then "military"; it learns the use of arms throughout its course; it frees the army to carry out the thousand functions of political struggle; it mixes in the life of everyone, the civilian with the fighter; it forces everyone to learn the art of war or peace, One cannot claim to live the process of communist liberation and to have the same relationship to violence, the same idea of beauty and of good and right, of desirable, the same idea of normalcy, the same habits of a middle-aged bank clerk from Turin: living with earthquakes is living always with terrorism and in order not to have an "heroic" idea of war one must first of all avoid a beggarly (dea of peace, Pacifists such as Lama enlist policemen, while those "most to the left" ask for the legitimization of "violence of the masses", of the "armed proletariat", The actual Movement was more realistic and less bellicose, more human and heroic: it put peace up for debate because it criticlzed war and It shattered the criterion of delegation and of legitimization because it rejected the army; It has done this with errors and Inaccurate approximations, with terrible deviations, by cultlyating absurd myths, all within a history, It has been contradictory, but it has learned and has improved a process that has modified reality more than an insurrection, MUNIST ICISM OF OCRACY Consequently, a critique of politics is also a critique of the war/peace distinction. The peace to which we refer Is the peace of democracy and the violence which it uses is "legitimate violence", which the majority has delegated to the institutions of the State: to criticize that violence means to criticize the most developed principle of political legitimization, democracy, That Is because the problem of legitimacy is the problem of the majority, and the problem of the majority is that of the institutions through which it expresses itself, In other words, the State: "majority" and "minority" belong to the universe of political thought, they divide their hold over the "common interest", they live through the separation of "public" and "private", of State and society, immersing their roots into the relationship of dominion which alone forces men to see themselves in terms of quantity, The majority constitutes itself in order to administer power: the more power is concentrated, the more the majority can do, and the less each individual can do; the more the "publiC" is well off, which is the Interest of everyone, so much the more Is the "private" poor, expropriated; the more dispossessed, destitute of expression, is the indiVidual Interest.

…

are in prison. 2 Sifo, Fontana, and Marchi are still in prison; Bifo, Fontana, and Marchi are always in prison. There isn't a single comrade who does not ask me, "And what do we do now?" Silence. And they take advantage of our silence. A month has already passed. But it was like a month in the mind of someone who Isn't thinking: an In· stant. A month has already passed since the arrest of Bifo and we have not got. ten him out of there. There is no proof, it's all a plot, we know it. And now what do we do? And now what do we do? We must do something, I want to do something, it isn't true that we are powerless before the monsters, the angels of death, the gray, the obtuse, the dangerous, I cannot keep quiet much longer.

…

The power of the opposition man/woman and woman/woman. "What bothered me most was the continuous repetition of "we are half, we are half, we are half." Are we half or do we want half? Are we half of the clear, beautiful, wild, but never conventional sky, or do we want to eat our half of the cake here on earth. I do not want half of what there Is today, of those values! refuse and fight I want the unity of the sky, even though I am only half the sky. do not refuse anything, I want everything. But I do not want what e)(ists already, 1 want what I create, what Is created through struggle." (Ua) "If one grants the Inevitable distortions faced In talking about the vas.t , theoretical practical aspects of the Movement, one can then summarize In three fundament~1 paints all the themes on power: 1) analysis of power and of th~ powers of the male society divided in classes; 2) analysis of the power relations created within the Women's Movement; 3) the elaboration of a liberation plan with regard to power.

Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the World

by

Tom Burgis

Published 7 Sep 2020

He went into government – by now he was one of the foremost figures in the new Kazakhstan – in charge of power supply, then as minister of energy, industry and trade. He alone stood up to the president, denouncing the promotion of Nazarbayev’s relatives and the creeping establishment of what he called a ‘clan-ocracy’. When he refused to continue in the cabinet, Nazarbayev demanded to see him. ‘You don’t respect your president,’ he ranted, ‘you don’t respect me as a person, you’re not loyal to me.’ He calmed down and asked again: ‘Come back and work for me.’ Again Ablyazov refused. ‘Well, in that case, you’re going to have to give me a chunk.’

…

He had often wondered how such crimes come about. ‘I have been able to answer that question by assuming and believing that most of us have a little voice inside us which speaks to us when we think of or are about to do something wrong. It says to us, “Don’t do it, it is wrong.” And there were times that I have come to know that there are some persons who don’t have that little voice. They never hear it, never listen to it. And there are some who do.’ Felix Sater, the judge thought, had heard the voice but declined to listen to it when his old friend offered him in on the scam. And this was no petty crime. Most people, he said, define serious offences as those that ‘inflict serious physical harm: murder, rape, burglary, assault.

…

‘I’m sorry to have to address it,’ Sasha began, ‘but I’ve heard that you are now working against the president as allies of Mukhtar Ablyazov.’ ‘I’m not a traitor,’ Khrapunov replied. ‘If the president chooses to believe this malicious gossip, I can do nothing but regret it.’ ‘Is that the message you want me to give?’ ‘Exactly.’ ‘So it’s a declaration of war?’ ‘You’ve been asked to repeat my answer word for word,’ Khrapunov said. ‘Just do that.’ Sasha wanted to be sure Khrapunov understood the consequences of perfidy. ‘You do know that the entire state machinery will be mobilised against you?’ Khrapunov replied that, if attacked, he would defend himself and his family. There was one more matter to discuss.

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It

by

Arthur Herman

Published 27 Nov 2001