The End of Indexing: Six Structural Mega-Trends That Threaten Passive Investing

by

Niels Jensen

Published 25 Mar 2018

It is not quite so dramatic in the UK, but the number is still high. Here is the problem. Across the world, many who live this way have experienced a drop in real wages in recent years, so even if the overall employment situation is quite robust, as there are no savings to fall back on, many have suffered a fall in living standards. The decline in real wage growth started all the way back in the 1970s and has coincided with an increase in corporate profits. More recently the trend has gained momentum, though, to the extent that real wages are now falling in some countries, which has had the effect of suppressing aggregate consumer demand even further.

…

See ‘The problem in a nutshell (second take)’ below for more on this topic. 89 Source RP Siegel (2012). 90 The greenhouse gas problem could also be addressed by accelerating the implementation of renewable energy forms, but that wouldn’t address our desperate need for cheaper energy, as renewables are still comparatively expensive. 91 In this context, the painful subject of falling real wages (i.e. falling living standards – at least in nominal terms) in certain countries is being conveniently ignored. 92 Hedonic regression is a method of valuing a product by breaking it into its constituent parts and then estimating the contribution of each part. 93 Although Feldstein’s comments are US specific, most other countries use the same approach when calculating inflation. 11.

The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It

by

Owen Jones

Published 3 Sep 2014

Siddarth sums up the general mentality: ‘I think the City is a convenient whipping boy, because everybody loves having a scapegoat,’ he says. ‘Everybody was more than happy to get a zero per cent interest rate on their credit card, everybody’s happy to spend, consume, and spend money that ultimately they don’t have.’ In truth, workers who had been experiencing real-term falls in their living standards long before the crash had been forced to top up their increasingly meagre income with cheap credit. In the City, you risked ridicule for even mentioning the impact of austerity on people’s lives. ‘If I started talking to people about cuts, I would be a figure of fun,’ says former City trader Darren.

…

Modern capitalism has become completely ‘financialized’, as Professor Costas Lapavitsas puts it. Modern businesses themselves indulge independently in financial speculation with their retained earnings, or the money that is not distributed to shareholders. Households are ever more dependent, too, as the growth of home ownership and the dependence on credit to top up falling living standards lands them in debt. The modern Establishment has been financialized to an unprecedented degree. Above all, the financial sector is a threat to British democracy. Governments have surrendered their economic powers, whether it be through the abandonment of exchange controls or the promotion of deregulation.

…

We should levy restrictions on foreign ownership of residential property, deflating potentially economically crippling housing bubbles that price Britons out of the market.6 Above all, this would shift economic sovereignty from corporate interests to elected governments, representing a sizeable blow to the Establishment’s position. A democratic revolution would have redistribution of wealth at its very heart. The bank accounts of the wealthy continue to boom, even as the recession causes a fall in living standards. This is not just manifestly unjust; it also represents a huge pile of cash that is not being invested and could be put to productive use. Money is being hoarded when it could be invested and put to social use. And while the poorest 10 per cent pay 43 per cent of their income in taxes, the richest 10 per cent pay just 35 per cent – surely an indefensible state of affairs from any rational perspective.7 More prosperous European countries, such as Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands and Belgium, have significantly higher top rates.

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by

Grace Blakeley

Published 9 Sep 2019

The Tories’ Economic Adviser on the Thatcher Years”, New Statesman, 8 March. https://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/the-staggers/2010/03/thatcher-economic-budd-dispatches 21 Shabani et al (2014) 22 This account draws on: Stockhammer (2010); Keynes (1936); Lapavitsas (2013); Hein (2012); Lysandrou, P (2011) ‘Global inequality, wealth concentration and the subprime crisis’, Development and Change, vol. 42. 23 The Institute of Employment Rights (2014) “Real Wages Have Been Falling Since the 1970s and Living Standards Are Not About to Recover”, 31 January. http://www.ier.org.uk/news/real-wages-have-been-falling-1970s-and-living-standards-are-not-about-recover 24 TUC (2016) 25 Shabani et al (2014) 26 Ibid. 27 Lawrence (2017) 28 World Bank (2019) “Gross Fixed Capital Formation (% GDP)”, World Bank dataset NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS?

…

Nationalists use dog-whistle racism to link voters’ experience of hardship and deteriorating living standards with an ill-defined “other” that can shoulder the blame. The only movements that have managed to absorb the discontent that would ordinarily fuel the far right are those that locate the blame for falling living standards where it belongs — with elites. Few traditional social democratic parties have lived up to the task, clinging instead to old narratives about a “third way” for workers between freedom and exploitation. As a result, they have been Pasokified — consigned to electoral insignificance just like the Greek social democratic party Pasok — leaving space for the far-right to take up the mantle of economic agitation.

Hostile Environment: How Immigrants Became Scapegoats

by

Maya Goodfellow

Published 5 Nov 2019

And so Miliband used his first party conference speech to declare: ‘You wanted your concerns about the impact of immigration on communities to be heard, and I understand your frustration that we didn’t seem to be on your side.’68 We got it wrong on immigration, he would repeatedly say as leader, implying New Labour let ‘too many’ people in. As Labour was pandering to anti-immigration sentiment, the Tories were charging ahead with their own agenda. Implementing austerity, cutting public services and overseeing a fall in living standards, the Conservatives also zeroed in on immigration. Under Theresa May and David Cameron, the government pledged to get immigration down to the tens of thousands. With this target in mind, May, as home secretary, oversaw the chilling 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts, which aimed to create a ‘hostile environment’ for undocumented migrants.

…

‘I’m hoping after the general election I can do a toast in that mug as we get on and change Britain for the better.’76 That celebration would never happen; with a net loss of twenty-six, Labour lost forty-eight seats in the election, Balls’s among them. As Patrick Gordon Walker is said to have done in Smethwick decades earlier, Miliband inadvertently reinforced the very rhetoric the far right thrived off. UKIP told the public that immigration was to blame for their falling living standards and the country’s creaky public services; Labour and the Conservatives said they were right. Unsurprisingly, people who were significantly motivated by immigration chose the genuine article over the unenthusiastic imitation; UKIP or the Tories rather than Labour. When I ask Harvey Redgrave, ex-Downing Street staffer and Ed Miliband’s former adviser on migration, why Labour didn’t robustly challenge anti-immigration messages at the 2015 General Election, he claims that had already been done.

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by

Anne Case

and

Angus Deaton

Published 17 Mar 2020

Since the end of the Great Recession, between January 2010 and January 2019 nearly sixteen million new jobs were created, but fewer than three million were for those without a four-year degree. Only fifty-five thousand were for those with only a high school degree.12 The prolonged decline in wages is one of the fundamental forces working against less educated Americans. But a simple link to despair from falling material living standards cannot by itself account for what has happened. For a start, the wage decline has come with job decline—from better jobs to worse jobs—with many leaving the labor force altogether because the worse jobs are unattractive, because there are few jobs at all, or because they cannot easily move, or some combination of these reasons.

…

Some people invent new tools, drugs, or gadgets, or new ways of doing things, and benefit many, not just themselves. They profit from improving and extending other people’s lives. It is good for great innovators to get rich. Making is not the same as taking. It is not inequality itself that is unfair but rather the process that generates it. The people who are being left behind care about their own falling living standards and loss of community, not about Jeff Bezos (of Amazon) or Tim Cook (of Apple) being rich. Yet when they think the inequality comes from cheating or from special favors, the situation becomes intolerable. The financial crisis has much to answer for. Before it, many believed that the bankers knew what they were doing and that their salaries were being earned in the public interest.

Disaster Capitalism: Making a Killing Out of Catastrophe

by

Antony Loewenstein

Published 1 Sep 2015

The New Economics Foundation found in 2013 that Britain had recently seen the biggest drop in living standards since the Victorian era, most severely affecting public sector workers and women.29 The bald facts of this austerity craze were enough to indicate that something was horribly wrong with modern politics. British prime minister David Cameron felt the need, in 2013, after years of austerity and falling living standards, to teach schoolchildren about the glories of capitalism—which seemed like a defensive impulse. It was vital, he said, to celebrate a culture “that values that typically British, entrepreneurial, buccaneering spirit.”30 Multinational corporations spent the twentieth century gradually reducing their obligations in the various jurisdictions in which they operated.

…

So dreams can unfurl.” 25Andrew Hill and Gill Plimmer, “G4S: The Inside Story,” Financial Times, November 14, 2013. 26“The Shadow State: A Report about Outsourcing of Public Services,” Social Enterprise UK, December 2012, at socialenterprise.org.uk. 27Larry Elliott, “Britain’s Five Richest Families Worth More than Poorest 20%,” Guardian, March 17, 2014. 28Paul Krugman, “The Austerity Agenda,” New York Times, May 31, 2012. 29Nigel Morris, “The Poorest Pay the Price of Austerity: Workers Face Biggest Fall in Living Standards since Victorian Era,” Independent, December 9, 2013. 30Tom McTague, “David Cameron Calls for Capitalism Lessons in Schools to Celebrate Profits in the Classroom,” Mirror, November 11, 2013. 31Rajeev Syal and Alan Travis, “Britain’s Immigration System in Chaos, MPs’ Report Reveals,” Guardian, October 29, 2014. 32Randeep Ramesh, “Hundreds of Contracts Signed in ‘Biggest Ever Act of NHS Privatisation,’” Guardian, October 3, 2012. 33Charlie Cooper, “NHS Funding Crisis: Boss Warns of 75 Pounds a Night Charge for Hospital Bed,” Independent, October 7, 2014. 34Benedict Cooper, “The NHS Privatisation Experiment Is Unravelling Before Our Eyes,” New Statesman, January 9, 2015. 35“‘People Will Die’—The End of the NHS.

This Land: The Struggle for the Left

by

Owen Jones

Published 23 Sep 2020

During this period, Labour cravenly failed to combat this migrant scapegoating, making repeated interventions which only helped stoke the issue, and, during Ed Miliband’s 2015 general election campaign, even selling election mugs emblazoned with the slogan ‘Controls on immigration’. By the time of the referendum, immigration frequently topped polls as voters’ main concern. With very few in public life willing to make a pro-migrant case – and with government policies fuelling social crises, ranging from falling living standards to a lack of affordable housing to crumbling public services, for which migrants were now being blamed – the backdrop for the referendum could hardly have been less favourable for Remain. In the first months of Corbyn’s leadership, Labour was split on how to approach the referendum: whether to follow Hilary Benn’s wholehearted embracing of the EU; or Corbyn’s own strategy of ‘Remain and Reform’ – a phrase coined by Seumas Milne – acknowledging that there were things wrong with the EU and reforms were needed, but that it was right to stay in.

…

While they are often flawed, it’s striking that in 1945, at the end of the war, the incumbent government led by a Conservative prime minister was swept aside in a landslide victory for a reforming Labour government, a Labour government which shredded the old status quo in favour of a new settlement, of a welfare state, National Health Service, public ownership and state intervention. Now the war had been won, Labour argued, it was time to win the peace. If Corbynism showed anything, then it is that ours is an age in which people are demanding radical solutions to a fall in living standards unprecedented for generations. The Covid-19 pandemic may well prove only the warm-up act for a far greater emergency that threatens human existence itself: a climate crisis, which demands a fundamental transformation of our social and economic system. Far from being answered, the injustices that led to the rise of Corbynism have only intensified.

The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It

by

Paul Collier

Published 26 Apr 2007

Although the reforms were modest, they were remarkably successful: output grew more rapidly than at any time during the oil boom. But these few percentage points of growth in non-oil output were completely swamped by the fall in the value of oil and the switch from borrowing to repayment, with the consequent contraction in expenditure. The reform-induced growth only helped slightly to offset the misery of falling living standards. That is what happened, but it is not what Nigerians think happened. Unsurprisingly, Nigerians think that the terrible increase in poverty they experienced was caused by the economic reforms that were so loudly trumpeted. Until reform, life was getting better; then along came reform, and poverty soared.

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

by

Andrew Yang

Published 2 Apr 2018

In his book Ages of Discord, the scholar Peter Turchin proposes a structural-demographic theory of political instability based on societies throughout history. He suggests that there are three main preconditions to revolution: (1) elite oversupply and disunity, (2) popular misery based on falling living standards, and (3) a state in fiscal crisis. He uses a host of variables to measure these conditions, including real wages, marital trends, proportion of children in two-parent households, minimum wage, wealth distribution, college tuition, average height, oversupply of lawyers, political polarization, income tax on the wealthy, visits to national monuments, trust in government, and other factors.

Servant Economy: Where America's Elite Is Sending the Middle Class

by

Jeff Faux

Published 16 May 2012

Men are bombarded with macho cultural icons: the athletes, the swaggering Wall Street speculators, and the gunslingers of interactive electronic games. Men have to earn a living, so most will work at whatever they have to, but by and large they will not like it. The surrounding culture will relentlessly push back the shame and ache of falling living standards back on the individual. The pronouncements from TVs, classrooms, and pulpits will continue to hammer home the message that people are responsible for their own fate. Self-help books, videos, and guest lecturers will promise that you can beat the odds if only you submit to the Seven Principles, the Five Steps, or the Ten Tenets of Success.

Getting By: Estates, Class and Culture in Austerity Britain

by

Lisa McKenzie

Published 14 Jan 2015

This has risen significantly since the austerity measures started to have an impact on communities after the 2010 General Election. In 2013 the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) published a report revealing that in the first full year of the coalition government, 300,000 more children faced a real fall in living standards that had pushed them into dire levels of poverty (Cribb et al, 2013). The entire increase is from homes where parents are working – there are now 2.4 million children in working households living in severe poverty. And on top of the 300,000 extra young people living below the breadline, half-a-million working-age adults have fallen into the extreme poverty bracket, along with an additional 100,000 pensioners (Cribb et al, 2013).

…

By 2014 – in the aftermath of the weakest economic recovery since the Victorian era – the Conservative-led coalition government was lauding the return of economic growth as vindication of its assault on public spending. But while it certainly was boom time for the rich – the Sunday Times Rich List recorded a doubling of the wealth of the richest 1,000 Britons between 2009 and 2014 – working people suffered the longest fall in living standards in well over a century. Disabled people faced the slashing of benefits, and the indignity and stress of appealing to win back their desperately needed support; workers enduring plummeting pay packets had their in-work benefits cut in real-terms; while no private pensions, no paid leave or no set hours became the reality for workers driven into zero-hour contracts or bogus self-employment.

Uncomfortably Off: Why the Top 10% of Earners Should Care About Inequality

by

Marcos González Hernando

and

Gerry Mitchell

Published 23 May 2023

163 Uncomfortably Off Question ‘business as usual’ As we discussed in Chapter 6, we found that respondents were accepting of how the economy works to deliver profits to the top with excessive pay and bonuses for a few, rather than working to improve the wellbeing of the majority.6 There was no reference, for example, to ten years of wage stagnation. Andy Haldane, a former chief economist at the Bank of England, has said that UK employees’ share of national income has fallen from 70% to 55% since the 1970s, which is less than what they received at the outset of the Industrial Revolution.7 Falling living standards should therefore come as no surprise, and none of this has anything to do with how hard people do or do not work.8 We, therefore, urge high-income earners to pause and consider why they think it is that the UK’s economic and political system doesn’t work for most people. How can they continue to be convinced by the argument that business as usual is best for our economy?

The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive During the Collapse of the Welfare State

by

James Dale Davidson

and

William Rees-Mogg

Published 3 Feb 1997

This chuckling aside, the themes of The Great Reckoning proved less ludicrous than the guardians of orthodoxy pretended. • We extended our forecast of the death of the Soviet Union, exploring why Russia and the other former Soviet republics faced a future of growing civil disorder4 hyperinflation, and falling living standards. • We explained why the 1 990s would be a decade of downsizing, including for the first time a worldwide downsizing of governments as well as business entities. 16 • We also forecast that there would be a major redefinition of terms of income redistribution, with sharp cutbacks in the level of benefits.

…

Therefore, eliminating or sharply reducing the taxes that are negatively compounding against their net worths may not appear to make them much better off-the price of lower taxation is a diminished stream of transfer payments. They will lose income because they will no longer be able to depend upon political compulsion to pick the pockets of persons more productive than themselves. Those without savings who rely upon government to pay their retirement benefits and medical care will in all probability suffer a fall in living standards. This loss of income translates into a depreciation of what financial writer Scott Burns has dubbed "transcendental" or political capital. 88 This "transcendental" or imaginary capital is based not upon the economic ownership of assets but upon the de facto claim to the income stream established by political rules and regulations.

The Year That Changed the World: The Untold Story Behind the Fall of the Berlin Wall

by

Michael Meyer

Published 7 Sep 2009

Nemeth was under no illusions about the depth of Hungary’s crisis, nor why he had been tapped as prime minister. He was being set up. He was to be the communists’ fall guy, the man whom the people would blame when the economy completely crumbled. Grosz and other party leaders feared they could not arrest Hungary’s economic slide—30 percent inflation, the highest per capita foreign debt in Europe, falling living standards and wages. Few Hungarian families could make ends meet without working two or even three jobs. Resentment was growing. So that May, at a fractious party conference, they looked around for a potential scapegoat to become prime minister. Nemeth, then head of the party economics department, was their choice.

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Jan 2017

Inequality has been static in several countries with growing populist movements and has fallen sharply in Poland which actually has a populist government.10 Nevertheless, a delayed reaction to the 2008 crisis and disillusionment with the broader economic and social order—including inequality, falling living standards after the crisis, and fewer good jobs for school leavers not destined for university—is clearly one of the recruiting sergeants for populist disaffection (see more detail in chapter six). The more important factor can be encapsulated in the notion that ‘Britain increasingly feels like a foreign country’—immigration, speed of demographic change and so on.

Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class

by

Owen Jones

Published 14 Jul 2011

After all, the vast majority of people who were out of work or poor did not riot. But there are growing numbers of young people in Britain with no secure future to risk. Youth unemployment is running at over 20 per cent. There is a crisis of affordable housing, the biggest cuts since the 1920s, and falling living standards; university tuition fees have trebled and the Educational Maintenance Allowance for students from poor backgrounds has been scrapped. Many young people have been left with very little to hope for. For the first time since the World War II,the next generation will be worse off than the generation before it. of course, we all have agency: we don't all respond to the same situation in the same way.

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 1 Jan 2010

Europeans know that, even if their industries shut down due to foreign competition, they will be able to protect their living standards (through unemployment benefits) and get re-trained for another job (with government subsidies), whereas Americans know that losing their current jobs may mean a huge fall in their living standards and may even be the end of their productive lives. This is why the European countries with the biggest welfare states, such as Sweden, Norway and Finland, were able to grow faster than, or at least as fast as, the US, even during the post-1990 ‘American Renaissance’. The oldest profession in the world?

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by

Jason Hickel

Published 3 May 2017

But in all cases net outflows strip developing countries of an important source of revenue and finance that could be used for development. The GFI report finds that increasingly large net outflows (since 2009 they have been growing at a rate of 20 per cent per year) have caused economic growth rates in developing countries to decline, and are directly responsible for falling living standards. * What this means is that poor countries are net creditors to rich countries – exactly the opposite of what we would usually assume. But when we consider the aid budget in its broader context, we should look not only at outward flows but also at the losses and costs that developing countries have suffered as a result of policies devised by rich countries.

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by

David Harvey

Published 3 Apr 2014

Does this portend a global capitalism managed under the dictatorship of the world’s central bankers whose foremost charge is to protect the power of the banks and the plutocrats? If so, then that seems to offer very little prospect for a solution to current problems of stagnant economies and falling living standards for the mass of the world’s population. There is also much chatter about the prospects for a technological fix to the current economic malaise. While the bundling of new technologies and organisational forms has always played an important role in facilitating an exit from crises, it has never played a determinate one.

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by

Stephen D. King

Published 22 May 2017

London, January 2017 INDEX Abbasids (i), (ii) Abu Bakr (i) Acemoglu, Daron (i) advertising (i) Afghanistan (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Africa (i) China and (i) high levels of ethnic diversity (i) oil, commodities and (i) population percentages (i) ‘scramble for’ (i), (ii) sub-Saharan nations (i), (ii), (iii) trade flows and slavery (i) ageing population (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Agincourt, Battle of (i) Al Qaeda (i), (ii)n2 Alaska (i) Ali (cousin/son-in-law to Prophet Mohammad) (i) Alibaba (i) Allies (Second World War) (i) Almaty (i) Almohads (i) Almoravids (i) Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (i) Amazon (i) America see United States American Civil War (i), (ii) American dollar (i), (ii) as good as gold (i) global foreign exchange market and (i) peso and (i) premier reserve currency (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) American Dream (i) American Samoa (i) Amin, Idi (i) Amsterdam Treaty (1997) (i), (ii) Anatolia (i) Andalucía (i) Andes (i) Angell, Norman (i), (ii), (iii) Angola (i) ‘animal spirits’ (i) Annecy (i) Apple (i), (ii) Arab nations (i), (ii) Arab Spring (i) Arabic language (i), (ii) Arabs (i), (ii), (iii) Aramaic (i) Arc of Prosperity (i) Argentina (i), (ii), (iii) Armenia (i) ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) (i) Asia see also China and other individual countries 1997/8 crisis (i), (ii), (iii) ageing population (i) balance of payments deficits (i) Central Asia (i), (ii), (iii) Columbus’s belief (i) East Asia (i) emerging market labour (i) events impinging on the West (i) immigrants in America (i) mathematical ability (i) Obama and (i), (ii), (iii) rail connections (i) Russia and (i) Trump and a vacuum (i) Asian Development Bank (i) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Asiatic Barred Zone Act (i) al-Assad, Bashar (i), (ii) asylum seekers (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v)n17 see also immigration; refugees Atatürk, Mustafa Kemal (i) Atlantic (i), (ii) Austen, Jane (i) austerity (i), (ii), (iii) Australia ASEAN and (i) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and (i) average incomes (i) foreign-born share of population (i) Second Gulf War (i) tobacco policy (i) Austria (i), (ii) Austro-Hungarian Empire (i), (ii) Axis (Second World War) (i) Azerbaijan (i) Bagehot, Walter (i) Baghdad (i) Baker, James (III) (i) balance of payments (i) Asian Crisis (i) Latin America (i) Plaza Accord and (i) UK and Suez (i) US (i), (ii) Varoufakis on (i) Balkans (i) Baltic Sea (i), (ii) bancor (i), (ii), (iii) Bangladesh (i) Bank of Credit and Commerce International (i) Bank of England (i), (ii) Bank of Japan (i) bankers (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) see also central banks Barings (i), (ii)n1 Basel I (i) Basel II (i) Basra (i) Battle of Bretton Woods, The (Ben Steil) (i)n4 BBC Two (i) Bedford (i) Beijing (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Belarus (i), (ii) Belgium (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Belt and Road strategy (i), (ii) Benn, Tony (i) Bentham, Jeremy (i) Berbers (i) Bergère, 14 rue (i) Berghof sanatorium (i) Berlin Wall (fall of) asylum seekers after (i) changing times after (i), (ii) Poland goes from strength to strength (i) relative living standards after fall (i) Soviet living standards (i) US military spending and (i) Bernanke, Ben (i) Big Brother (i) Bilderberg Club (i) bin Laden, Osama (i) Bitcoin (i) Black and White Minstrel Show, The (i) Black Death (i) Black Sea (i), (ii), (iii) Blair, Tony (i), (ii), (iii) Blanchard, Olivier (i) Blockchain (i) Blue Feed (i) BMW (i) BNP Paribas (i) Boers (i) Boko Haram (i) Bolsheviks (i) see also communism borders (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) see also cross-border capital flow capital flows see cross-border capital flow EU and (i) globalization and (i) historical accident (i) Mediterranean (i) movement of labour (i), (ii) post-global financial crisis (i), (ii) railways and (i) slowly dissolving (i), (ii) technology and (i), (ii) Triffin Dilemma (i) Boston (i), (ii) Boughton, James M.

Near and Distant Neighbors: A New History of Soviet Intelligence

by

Jonathan Haslam

Published 21 Sep 2015

He had finally allowed the imbalance of military power in Europe, which had stood provocatively and overwhelmingly to Soviet advantage since 1945, to be broken unopposed. Behind all this lay a basic truth: Moscow had effectively already given up the ideological struggle. The Russia reborn in 1992 had to confront the unexpected need to substitute at short notice raw patriotism for a long-outmoded belief in a global ideal, all in the face of falling living standards and full consciousness—not least via MTV, now beamed freely into city apartments—of what the West could offer in return for betrayal. The negative impact on intelligence assets and their recruitment was severe, given how heavily Moscow depended upon human resources once attracted by and tied to the Soviet model.

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by

Judith Stein

Published 30 Apr 2010

In April 1950 the Bureau of the Budget announced: “Foreign economic policies should not be formulated in terms primarily of economic objectives; they must be subordinated to our politico-security objectives and the priorities which the latter involve.”27 Three years later, the National Security Council urged the entry of Japanese goods to the United States to halt “economic deterioration and falling living standards” in Japan that “create fertile ground for communist subversion.”28 The State Department judged that “Japan’s resistance to Soviet-Sino pressures will depend in large measure on whether the free world [is] willing [to] make reasonable place for Japan’s trade.”29 Many believed that American industry was so strong that it would not suffer from unilateral trade measures that drew in imports from Europe and Japan.

Protest and Power: The Battle for the Labour Party

by

David Kogan

Published 17 Apr 2019

May was accused of being a liar, of regretting calling the election, and of not getting into a debate. Corbyn was asked about his record on Northern Ireland and his position on the use of nuclear weapons. What was the reality of him ever exercising their use? Would he allow Iran or North Korea to bomb us first? The key soundbite was Theresa May under attack about falling living standards, from a nurse of twenty-six years’ experience, living on the same salary as 2009. May produced the line ‘there isn’t a magic money tree’ which both patronised the nurse and infantilised the answer. This was the latest in a series of appearances where Corbyn had surpassed expectations and May had under-performed.

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by

Johan Norberg

Published 14 Sep 2020

The domestic population was always big enough to sustain a division of labour, and – even if contact with the rest of the world was limited to invasions, government barter, kidnappings and espionage – they did know the world was there and they preyed on the innovations taking place elsewhere. And yet, in every case it resulted in something similar to the Late Bronze-Age Collapse and the fall of the Roman Empire: stagnation and falling living standards. Often the protectionist backlash was a response to increased imports that helped consumers but hurt producers and workers in affected industries. The Great Depression is the classic example. Just as free trade started to make the West rich, the forces opposing it gathered momentum. Open trade combined with cheaper transportation and the invention of refrigeration made it possible for cheap American grain and meat to reach hungry Europeans, and for cheaper European manufacturing goods to enter American homes.

England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country – and How to Set Them Straight

by

Tom Baldwin

and

Marc Stears

Published 24 Apr 2024

Like Brexit itself, which was always an abstract idea rather than a specific proposal, this vague hostility towards immigration and people of different ethnicity nonetheless had a big effect on politics in these years, particularly for a Labour Party that too often appeared to have taken working-class voters in northern towns for granted. Robert Ford, who was one of the first pollsters to spot UKIP’s potential, has shown how a significant portion of voters in places like Blackpool preferred to blame falling living standards and status not on global capitalism or ‘Tory austerity’ but on asylum seekers and immigrants.38 In 2014, two unassuming academics from the University of Southampton, Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker, crystallised this into the idea that there were ‘Two Englands’. Since the start of this century, they explained, growing economic inequality had opened up an ever-widening chasm in values and identity.

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by

Stewart Lansley

Published 19 Jan 2012

In an echo of Ronald Reagan’s war on air traffic controllers in the 1980s, this was an attempt to dismantle what was left of union power, one which led to sustained protests across the country. A similar divide has been emerging in the UK. After falling in every year from 2005-2010, real take-home pay is now predicted to continue to fall for the next year or two at least. This is the first time since the 1920s there have been six successive years of falling real living standards, a process that started well before the crash. In both the US and the UK, the likelihood is that wages will continue to lag productivity postrecovery, living standards will continue to stagnate while the wealth and income gap will remain at historic highs. Indeed, the new independent economic overseer set up by the Coalition, the Office for Budget Responsibility, has forecast that the United Kingdom’s wage share will continue to fall until 2016.416 The risk now is that the fundamental economic factor that has driven rising instability and created the conditions for the crash—the two-decade long growing wage-productivity gap in both the UK and the US—is set to continue.

Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire

by

Danny Dorling

and

Sally Tomlinson

Published 15 Jan 2019

Here’s why’, The Guardian, 22 November, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/22/british-empire-museum-colonial-crimes-memorial 6 Buchan, L. (2017) ‘Britain’s debt will not fall to 2008 levels until 2060s, IFS says in startling warning’, The Independent, 23 November, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/british-debt-uk-deficit-not-fall-below-2008-levels-2060-financial-crash-economy-warning-a8071696.html 7 Watts, J. (2017) ‘UK facing longest fall in living standards for over 60 years, finds think tank’, The Independent, 23 November, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/uk-living-standards-fall-longest-60-years-records-began-economy-household-incomes-costs-energy-a8071146.html 8 Wearmouth, R. (2017) ‘Budget 2017: Chancellor Blasted For Finding More Additional Money For Brexit Than The NHS’, Huffington Post, 22 November, http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/brexit-nhs-budget_uk_5a158a00e4b09650540e914c 9 Alexander, A. (2017) ‘Britain without a judge on the International Court of Justice for first time since 1946’, Daily Telegraph, 20 November, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/11/20/britain-without-judge-international-court-justice-first-time/.

…

In 2018, it was reported by the statistics portal Statista that most recently China had 34 per cent of the world market, South Korea 22 per cent and Japan 21 per cent. The EU, which included Britain, and to which was added Norway, took only 11 per cent of the market, leaving just 12 per cent for the rest of the world, including what little shipbuilding is still undertaken in the USA. Today, Brexiteers ignore the impact of the falling pound on inflation and living standards, preferring to suggest that the fall will be ‘good for trade’. When doing this, they are also ignoring the investment problem. We know that without investment, cheaper exports have a limited impact for a limited time. As the then Prime Minister Edward Heath told the Institute of Directors in 1973: The curse of British industry is that it had never anticipated demand.

Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power

by

Patrick Major

Published 5 Nov 2009

These were all prominent GDR artists—Biermann had been deported in 1976, while Krug and Mueller-Stahl were allowed to leave the following year. ¹⁰⁴ Cited in Madarász, Conflict, 143. ¹⁰⁵ Jena citizens to Volkskammer, 12 July 1983, exhibit in Museum Haus am Checkpoint Charlie, 2001. ¹⁰⁶ Lehmann to Eichler, 3 Jan. 1975, BAB, DA-5/9013. 212 Behind the Berlin Wall mould growing on their furniture.¹⁰⁷ Others attacked falling living standards. In such cases the authorities usually tried to remedy the immediate cause of the aggravation, in the interests of achieving a retraction. Such applications could, it has to be said, range from the sublime to the ridiculous and petitions officers must occasionally have wondered if pranks were being played.

Dictatorland: The Men Who Stole Africa

by

Paul Kenyon

Published 1 Jan 2018

Facing a fall in their wages, the police and army began setting up extra road blocks to shake money from motorists. Cocoa drivers went on strike. Gradually people began taking to the streets, mainly students and teachers at first, but even former loyalists soon joined them. It wouldn’t have escaped the president’s notice that the favourite chant was ‘Corrupt Houphouet’. Resentment over falling living standards turned into demands to move away from a single-party state and introduce multi-party elections. Leading the protests was the young history professor he had chastized in his study all those years before. Laurent Gbagbo could smell blood; the president had never experienced such public dissent.

Money: 5,000 Years of Debt and Power

by

Michel Aglietta

Published 23 Oct 2018

When investment opportunities weakened in Britain, British savings were invested in the areas being colonised. The capital flows to these regions increased the supply of raw materials from mining and, especially, agricultural production. At the same time, stagnation in Britain reduced demand. The prices of the imported food products began to fall. Living standards in British agriculture were reduced and the population was thus pushed to move to the cities. The concomitant low cost of subsistence goods and the excess labour force increased capital profitability. An investment boom took off in Britain. It lasted until the increase in employment levels and the rise in the cost of subsistence goods pushed up wages to the point that profitability again began to decline.

Growth: A Reckoning

by

Daniel Susskind

Published 16 Apr 2024

These ‘subsistence ratios’ provide an insight into economic life in a given place: a ratio of one means that people there could just afford that barebones diet.5 Figure 2 shows Allen’s ‘subsistence ratios’ for several cities. Figure 2: Subsistence ratios for labourers before 18006 Figure 2 shows that before 1800, the global trends were similar to the English ones of Figure 1: there are some rises and falls in living standards but no overall upwards movement. In fact, if there is a general trend, it is a decline in living standards after a bounce in the fourteenth century following the Black Death. These subsistence ratios also show that while people in cities such as London and Amsterdam may have escaped starvation, those elsewhere – in Europe, India and China – led a more wretched economic existence.

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

James Robinson

Published 20 Mar 2012

The Luddite Riots of 1811–1816, where workers fought against the introduction of new technologies they believed would reduce their wages, were followed by riots explicitly demanding political rights, the Spa Fields Riots of 1816 in London and the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 in Manchester. In the Swing Riots of 1830, agricultural workers protested against falling living standards as well as the introduction of new technology. Meanwhile, in Paris, the July Revolution of 1830 exploded. A consensus among elites was starting to form that the discontent was reaching the boiling point, and the only way to defuse social unrest, and turn back a revolution, was by meeting the demands of the masses and undertaking parliamentary reform.

The Economic Weapon

by

Nicholas Mulder

Published 15 Mar 2021

The prospect of material damage rather than moral stigma would induce publics to restrain their governments’ aggressive behavior. Identifying public opinion with the primacy of commercial motives was no doubt appealing to the bourgeois officials on the IBC. Still, their conviction that a population’s fear of falling living standards could preserve peace was striking. Would the doux commerce of economic exchange always trump the amour-propre that encouraged nationalism and aggression? In light of the deep distrust and division left behind by the war, many commentators were skeptical. Even Norman Angell, the most famous early twentieth-century proponent of the softening commerce argument, concluded that same year, “What we have seen in recent history is not a deliberate choice of ends with a consciousness of moral and material cost.

Paper Promises

by

Philip Coggan

Published 1 Dec 2011

The second category consists of those borrowers who had secured their debts against an asset which has fallen in value. In such circumstances, both the borrower and the creditor lose out. The borrower’s wealth is less than it was and so is the creditor’s. They have discovered, like the clients of Bernie Madoff, that part of their wealth was illusory. The result could be a substantial fall in living standards, rather than just sluggish growth. THE LONG VIEW As this book has explained, the world has seen cycle after cycle in which money and debts have expanded. These cycles are initially self-reinforcing as the extra money begets confidence, as in John Law’s experiment in the early eighteenth century.

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by

Ian Kershaw

Published 29 Aug 2018

But why had the Soviet Union faced no significant problem before then from the Czechs and Slovaks? In fact, there had been a serious wave of strikes in Czechoslovakia in May 1953, triggered by the announcement of a swingeing currency devaluation to be introduced the next month (widely dubbed ‘the Great Swindle’) and following months of sharply rising prices and falling living standards. Strikers from the Škoda factory in Plzeň had even thrown busts of Lenin, Stalin and Klement Gottwald (the Czech communist leader, who had died within days of Stalin’s death) out of the window of the town hall, which they had occupied. But the disturbances were savagely put down by the police and never developed into the outright challenge to the regime similar to that which was shortly to explode in the German Democratic Republic.

The Great Reset: How the Post-Crash Economy Will Change the Way We Live and Work

by

Richard Florida

Published 22 Apr 2010

Or, as the blogger Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism put it, “The US needs to wean itself of unsustainable overconsumption, and since consumption has come to depend on growth in indebtedness, a reversal, however painful, is necessary. Our excesses have been so great that there is no way out of this that does not lead to a general fall in living standards.”9 At a deeper level, the financial meltdown also signaled the rise of a new economic system broadly. The Long Depression was the crisis of the First Industrial Revolution. The massive growth and productivity of the textile, steel, and railroad industries could not be contained by the larger, mainly rural society of the period.

Scotland’s Jesus: The Only Officially Non-Racist Comedian

by

Frankie Boyle

Published 23 Oct 2013

Who cares if she had a facelift? It’s like people talking about whether Hitler dyed his moustache. She’s an anti-abortion feminist, placing her on the list of great feminists somewhere between Peter Sutcliffe and Henry VIII. The Tories have done a brilliant job while in power. The UK has suffered the worst fall in living standards since the Second World War. I’d add an ‘apparently’ to that as I’m not convinced downgrading from Sainsbury’s to Asda quite compares with picking dead relatives out of the rubble. Cameron says it’s time for Britain to show the world what it’s made of. Though I’m not sure exactly what you can knock together out of debt and diabetes.

The New Class Conflict

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 31 Aug 2014

Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries,” OECD Multilingual Summaries, 2008, p. 2; Andrew Grice, “New Law to Enforce Social Mobility,” Independent, January 14, 2009; Mia Shanley, “Swedish Equality Fades Away as Rich Get Richer,” Reuters, Mar 21, 2012; Joel Kotkin, “The Broken Ladder: The Threat to Upward Mobility in the Global City,” Legatum Institute, May 2010, http://www.newgeography.com/files/The-Broken-Ladder-Joel-Kotkin.pdf. 18. Gary Duncan, “Brown’s Legacy Is a Nation More Divided than Ever,” Times (UK), June 8, 2009; Ilona Billington and Nicholas Winning, “U.K. Politicians Vie to Address Fall in Living Standards,” Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2013. 19. Katya Vasileva, “6.5% of the EU Population Are Foreigners and 9.4% Are Born Abroad,” Eurostat, July 7, 2011, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-11-034/EN/KS-SF-11-034-EN.PDF; World Population Review, “Sweden Population 2014,” http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/sweden-population; U.S.

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by

Mervyn King

Published 3 Mar 2016

One day German voters may rebel against the losses imposed on them by the need to support their weaker brethren, and undoubtedly the easiest way to divide the euro area would be for Germany itself to exit. But the more likely cause of a break-up of the euro area is that voters in the south will tire of the grinding and relentless burden of mass unemployment and the emigration of talented young people. The counter-argument – that exit from the euro area would lead to chaos, falls in living standards and continuing uncertainty about the survival of the currency union – has real weight. But if the alternative is crushing austerity, continuing mass unemployment, and no end in sight to the burden of debt, then leaving the euro area may be the only way to plot a route back to economic growth and full employment.

The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity

by

Lynda Gratton

and

Andrew Scott

Published 1 Jun 2016

In fact, one study found that 70 per cent of people aged 70 or under felt there was a minimal chance of selling their house to pay for retirement.7 Another study found that when people retire they are equally as likely to move into a larger house as a smaller one.8 It is generally only traumatic events, such as death of a partner or illness, that tends to trigger house sales as people age. Given that owning a house provides imputed rent, and selling a house involves a fall in living standards, it is no surprise that equity release schemes have been growing in popularity with older home owners. Equity release helps provide financing without the loss of imputed rent. This clearly has a role to play in providing financing for old age, but while these schemes make a contribution, they cannot be relied upon to solve the problem.

Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1945-1956

by

Anne Applebaum

Published 30 Oct 2012

Initial discussion topics included the peasants’ revolt of 1514 (a pretext for a debate on agricultural policy) and an analysis of Hungarian historiography (a pretext for a debate about the falsification of history in communist textbooks).55 The choice of name quickly proved “double-edged,” as one Hungarian writer put it: Petőfi had been a revolutionary fighting for Hungarian independence and the group bearing his name soon felt empowered to become revolutionary too.56 Changes had been taking place in other regime institutions at the same time. At Szabad Nép, the communist party’s hitherto reliable newspaper, reporters had become restless. In October 1954, a group of them, sent to cover life in the country’s factories, returned wanting to write about faked production statistics, falling living standards, and workers who had been blackmailed into buying “peace bonds.” In a published article, they declared that “though the life of the workers has changed and improved a great deal in the last ten years, many of them still have serious problems. Many are still living in overcrowded and shabby apartments.

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 26 Dec 2007

Even if we discount the 1980s as a decade of adjustment and take it out of the equation, per capita income in the region during the 1990s grew at basically half the rate of the ‘bad old days’ (3.1% vs 1.7%). Between 2000 and 2005, the region has done even worse; it virtually stood still, with per capita income growing at only 0.6% per year.21 As for Africa, its per capita income grew relatively slowly even in the 1960s and the 1970s (1–2% a year). But since the 1980s, the region has seen a fall in living standards. This record is a damning indictment of the neo-liberal orthodoxy, because most of the African economies have been practically run by the IMF and the World Bank over the past quarter of a century. The poor growth record of neo-liberal globalization since the 1980s is particularly embarrassing.

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 4 Jul 2007

Even if we discount the 1980s as a decade of adjustment and take it out of the equation, per capita income in the region during the 1990s grew at basically half the rate of the ‘bad old days’ (3.1% vs 1.7%). Between 2000 and 2005, the region has done even worse; it virtually stood still, with per capita income growing at only 0.6% per year.21 As for Africa, its per capita income grew relatively slowly even in the 1960s and the 1970s (1–2% a year). But since the 1980s, the region has seen a fall in living standards. This record is a damning indictment of the neo-liberal orthodoxy, because most of the African economies have been practically run by the IMF and the World Bank over the past quarter of a century. The poor growth record of neo-liberal globalization since the 1980s is particularly embarrassing.

The Rent Is Too Damn High: What to Do About It, and Why It Matters More Than You Think

by

Matthew Yglesias

Published 6 Mar 2012

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 26 May 2014

The growth acceleration was so dramatic that the half-century following 1820 is typically referred to as the Industrial Revolution.6 In those fifty years, per capita income in Western Europe grew at 1 per cent, a poor growth rate these days (Japan grew at that rate during the so-called ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s), but compared to the 0.14 per cent growth rate between 1500 and 1820, it was a turbo-charged drive. Expect to live for seventeen years and work eighty hours a week: misery increases for some This acceleration of growth in per capita income, however, was initially accompanied by a fall in living standards for many. Some with old skills – such as textile artisans – lost their jobs, having been replaced by machines operated by cheaper, unskilled workers, including many children. Some machines were even designed with the small sizes of children in mind. Those who were hired to work in factories, or in the small workshops that supplied inputs for them, worked long hours – seventy to eighty hours per week was the norm, and some worked more than 100 hours a week with usually only half of Sunday free.

Licence to be Bad

by

Jonathan Aldred

Published 5 Jun 2019

People enter the market with different housing assets (some inherit a house) and some prices rise much faster than others, so there can be relative winners and losers from rising average house prices. But these complications do not undermine the main argument. 48 The price of some positional goods (such as desirable houses) will fall; in other cases, where prices reflect international demand (sports cars), the price may not fall but living standards are unlikely to be much affected from having to scale back from, say, a Ferrari Berlinetta to a Porsche 911 Turbo at half the price. See below. 49 Frank, 91. 50 For the UK, see Atkinson, Inequality, 237–9. For the US, see Stiglitz, 336–55. 51 Interview with Rupert Cornwell, Toronto Globe and Mail, 6 July 2002. 52 For more discussion and references see Mcquaig and Brooks, 121–3. 10.

Hard Times: The Divisive Toll of the Economic Slump

by

Tom Clark

and

Anthony Heath

Published 23 Jun 2014

‘Benefit fraud could lead to 10-year jail terms, says DPP’, BBC News, 16 September 2013, at: www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk–24104743 By way of comparison, the official figures for average punishments for some other crimes are reported on by Alan Travis, ‘Rape sentences now average eight years, Ministry of Justice figures show’, Guardian, 27 May 2011, at: www.theguardian.com/society/2011/may/26/rape-sentence-average-eight-years-justice-figures 22. Curtice, ‘Thermostat or weather vane?’. 23. British polling by YouGov from spring 2013 suggests that a majority (52%) of poorer families (gross income below £20,000) anticipate a continuing fall in living standards, compared to less than one-third (31%) of households where income exceeds £70,000. Details reported in: Resolution Foundation, 2015: The living standards election, 2013, at: www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/media/downloads/2015_-_The_living_standards_election.pdf 24. Tom Clark, ‘Britons favour state responsibilities over individualism, finds survey’, Guardian, 15 April 2013, at: www.theguardian.com/society/2013/apr/14/britons-sympathetic-unemployed-france-germany 25.

The Classical School

by

Callum Williams

Published 19 May 2020

State of Emergency: The Way We Were

by

Dominic Sandbrook

Published 29 Sep 2010

Although most people had read in their newspapers about Britain’s competitive decline, and were certainly aware that the country had lost power and prestige since the Second World War, their own lives, by and large, had been marked by greater affluence and opportunity. They had not yet realized the penalties – in higher prices, falling living standards, pay freezes and strikes – they would have to pay for Britain’s economic problems, and there was little sense that they wanted radical change. What was more, Heath’s bloodless brand of time-and-motion modernization was not always very attractive, a classic example being Walker’s reform of local government.

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by

Philip Coggan

Published 6 Feb 2020

All of the member countries bar Portugal traded more with EEC countries than with each other. Britain’s trade with the EEC grew faster in the first half of the 1960s than with other EFTA members.18 So in 1962, the British government applied to join the EEC, only to be rebuffed by the French president, Charles de Gaulle.19 Britain continued to worry that it was falling behind European living standards and, in 1967, it applied again, and faced a second veto by De Gaulle. The UK only managed to join the EU in 1973 (along with Denmark and Ireland) after De Gaulle left office. The move was designed to stop the rot in Britain’s economic performance: in 1950, the UK’s per capita GDP was almost a third larger than the average of the six original EEC members, but by 1973, it was 10% below it.20 In the immediate post-war period, Britain made an enormous effort to repair its position, restricting domestic consumption through rationing and focusing on overseas trade; by 1950, the country produced 22% of global manufacturing exports.21 Yet it was dogged by balance of payments issues and sterling crises, and by its poor industrial relations record.

Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change

by

George Marshall

Published 18 Aug 2014

When results for different time scales are plotted on a chart, the resulting curve is hyperbolic—that is to say that the sense of relative loss is most acute in the near future but declines in the distant future. Hence—not too surprisingly—this is called hyperbolic discounting. Taken together, this research relates directly to climate change, suggesting, as Kahneman feared, that people will be strongly disposed to avoid short-term falls in their living standard and to take their chances on the uncertain but potentially far higher costs that might come in the longer term. As predicted by the hyperbolic discounting model, governments have proven to be extremely unwilling to incur costs in the short term but perfectly willing to accept far greater costs in the future.

Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

by

R. Christopher Whalen

Published 7 Dec 2010

Grant imposed legal tender laws on Americans via the subversion of the Supreme Court set a pattern of duplicity by the Executive Branch that remains strongly embedded in American jurisprudence today. By giving the federal government control over the issuance of “money,” which was now defined as a piece of paper, an expedient war leader doomed future generations of Americans to live with inflation and falling real living standards, the bitter legacy of all legal tender laws going back centuries before the founding of the United States. When émigrés from Europe came to the United States seeking freedom, it was not just religious liberty or freedom from physical bondage, but also freedom from the tendency of monarchs to compel their subjects to use the king’s money, which was frequently light in terms of metal content.

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by

Marc Levinson

Published 31 Jul 2016

The Passenger: Greece

by

The Passenger

Published 11 Aug 2020

Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing

by

Josh Ryan-Collins

,

Toby Lloyd

and

Laurie Macfarlane

Published 28 Feb 2017

This of course disguises large regional variations – in more desirable areas such as London and the South East the ratio is up to twenty times (ONS, 2015c). Recent research shows that when housing costs (including mortgage debt and rents) are included in an assessment of changing living standards since 2002, over half of UK households across the working age population have seen falling or flat living standards (Clarke et al., 2016). Figure 5.2 House prices and mortgage debt compared to income in the UK (source: ONS, Nationwide and Bank of England; data de‹ated using 2010 prices) The impact of rising housing costs is not distributed equally across populations of course. In 2013, 1.17 million households had mortgage debts amounting to more than 4.5 times their disposable income – representing nearly one in seven (13.2%) households with mortgages (ONS, 2015a, p. 1).

Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy Is a Sign of Success

by

Dietrich Vollrath

Published 6 Jan 2020

It would probably be wise to avoid the latter, but nevertheless let me offer some tentative predictions about what to expect with respect to growth over the next few decades. You may not be surprised that I believe the growth rate will continue to be low relative to the twentieth century and may fall further as living standards continue to improve. I see no obvious reason that the growth rate would accelerate in the near future. Take human capital first. At some point the demographic changes that have been pulling down the growth rate will subside, as the baby boom generation will not live forever. But that is still several decades into the future, so for the time being this drag on the growth rate will persist.

A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841-1997

by

Steve Tsang

Published 14 Aug 2007

Severe inflation had occurred as a result of the shortages caused by wartime disruptions and the rapid increase in population, which pushed up rent and the price of various commodities while wages remained static.21 This rise in the cost of living without a compensatory increase in wages put a serious strain on the working people, with the low-paid labourers being hit the hardest. A manifestation of this problem was the rice riots of 1919. They broke out as prices shot up following the failure of the rice crop in Thailand, restriction of exports in Indo-China and India, as well as an unexpected upsurge in demand in Japan.22 The fall in living standards among the Chinese working class created serious social tension and laid the ground for a period of labour unrest and social changes after the end of the Great War. Labour Unrest The first wave of labour unrest was a 19-day strike organised by the Hong Kong Chinese Engineers’ Institute in March 1920, which had been established only six months earlier.

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by

Guy Standing

Published 13 Jul 2016

It is an instance of the Lauderdale Paradox, in which commodification is an act of privatisation that contrives scarcity of space or time. These forms of labour intensify the pressure to commodify all aspects of life. Intensifying self-exploitation is a sad way for the precariat to respond to adversity. It is how those experiencing falling wages and living standards cover up the decline, for a while. In addition, governments will have fiscal problems due to the changing character of labour and work. The shift to taskers will reduce tax revenue through lower employee and employer contributions and will push more people below tax thresholds, for example by expanding part-time labour.

GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

by

Diane Coyle

Published 23 Feb 2014

The Downfall of Money: Germany's Hyperinflation and the Destruction of the Middle Class

by

Frederick Taylor

Published 16 Sep 2013

Good Times, Bad Times: The Welfare Myth of Them and Us

by

John Hills

Published 6 Nov 2014

The further benefit cuts announced since the 2015 election, alongside further increases in income tax allowances, will extend the regressiveness of the Coalition’s reforms. In the long run, the quiet and often hidden processes of how we adjust the level of benefits and tax allowances from year to year can have just as great an effect. Left on autopilot, if and when the economy returns to growth, each year benefits and tax credits tend to fall behind general living standards (although pensions are now insulated from this), and fiscal drag brings a bigger share of income into tax, and into tax at higher rates. Letting this run on helps public finances, but does so in a way that increases inequality and poverty. Recent short-term fiscal adjustments have been regressive, but so – unless conscious decisions are made to offset it – are the long-term effects of how we adjust the tax and benefit systems to allow for growth and inflation.

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by

Charles Handy

Published 12 Mar 2015

The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East

by

Andrew Scott Cooper

Published 8 Aug 2011

Insolvency beckoned and with it the specter of national bankruptcy. Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey defended the loan and warned Britons that failure to act would result in an “economic policy so savage that I think it would produce riots in the streets. It would mean an immediate and very heavy fall in living standards and unemployment, maybe 3 million.” Healey also knew that Britain was obliged to somehow meet the first payment on a separate $5.93 billion international standby credit due to fall on December 9. There was wild talk of the overthrow of the government. “Nobody wants to talk about it, but the possibility of a breakdown in law and order, or an extremist revolt in Great Britain, gives the United States and other NATO governments the chills,” reported The Washington Post.

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by

Matthew C. Klein

Published 18 May 2020

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by

Edward Fishman

Published 25 Feb 2025

Russian firms slashed investment to conserve cash for debt repayments, and demand for safety-deposit boxes shot up as ordinary Russians hoarded foreign currency. Putin’s popularity had skyrocketed in the wake of the Crimea annexation. His approval rating hit an all-time high of 88 percent. But it was doubtful Russians would remain so supportive if their economy went into free fall. Plummeting living standards would be a high price to pay for new classroom maps that shaded Crimea in the same color as Russia. Putin charged Elvira Nabiullina with navigating the storm. On November 5, Nabiullina hiked interest rates to 9.5 percent. The central bank stood ready “at any moment,” she declared, to deploy far more of its hard currency reserves to support the ruble.

The Growth Delusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-Being of Nations

by

David Pilling

Published 30 Jan 2018

Certainly, Japan had problems and it was true that its economic miracle, which had so astonished the world in the 1980s, had run out of steam. But Japan’s supposed misery—as measured by nominal GDP—really didn’t feel like misery at all.12 Unemployment was extremely low, prices stable or falling, and most people’s living standards rising. Communities were intact, certainly in comparison to those in America, Britain, and France. Crime was low, drug use almost nonexistent, the quality of food and consumer goods world class, and health and life expectancy among the highest in the world.13 And yet, viewed through the prism of economics, Japan was an abject failure.

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

by

Richard Heinberg

Published 1 Jun 2011

Meltdown: How Greed and Corruption Shattered Our Financial System and How We Can Recover

by

Katrina Vanden Heuvel

and

William Greider

Published 9 Jan 2009

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by

Matt Ridley

The Rise of the Outsiders: How Mainstream Politics Lost Its Way

by

Steve Richards

Published 14 Jun 2017

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by

Erik Brynjolfsson

and

Andrew McAfee

Published 20 Jan 2014

The Wealth of Humans: Work, Power, and Status in the Twenty-First Century

by

Ryan Avent

Published 20 Sep 2016

Invisible Women

by

Caroline Criado Perez

Published 12 Mar 2019

A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s

by

Alwyn W. Turner

Published 4 Sep 2013

Equally important to his image as a Thatcherite, however, was a simple cultural perception of his humble origins. His father was a trapeze artist in the music halls, who had moved with some success into the garden ornaments business, before the bottom dropped out of the gnome market on the outbreak of the Second World War. By the time John Major was born in 1943, the family had suffered a severe fall in living standards, and he grew up in straitened circumstances in South London, leaving school with just three O-levels. The fact that he subsequently rose so high was entirely due to his involvement in the Conservative Party, and was seen as a fine illustration of a new meritocracy. ‘What does the Conservative Party offer a working class kid from Brixton?’

The Future Is Asian

by

Parag Khanna

Published 5 Feb 2019

Paper Girl: A Memoir of Home and Family in a Fractured America

by

Beth Macy

Published 6 Oct 2025

Break Through: Why We Can't Leave Saving the Planet to Environmentalists

by

Michael Shellenberger

and

Ted Nordhaus

Published 10 Mar 2009

Instead of inspiring his audience around a vision of global interdependence—where economic prosperity, ecological restoration, and crosscultural understanding are woven together—Blair offered a dry, textbook description of global warming science and a defensive insistence that Kyoto wouldn’t harm the economy. “However,” Blair said, “behind the dispute over science is another concern. Political leaders worry they are being asked to take unacceptable falls in economic growth and living standards to tackle climate change.” It is tempting to chalk up the speech’s shortcomings to un-creative speechwriting. But Blair’s oratorical skills are fine—witness his powerful speeches on terrorism in the wake of September 11. Blair lacked neither the proper emotional commitment nor good speechwriters.

The Transformation Of Ireland 1900-2000

by

Diarmaid Ferriter

Published 15 Jul 2009

Although Ireland’s national debt may not have been large by contemporary European standards, control of credit was curtailed by the link with sterling, and despite the establishment of a Central Bank in 1943, Irish bank lending was still heavily concentrated in the City of London.42 If any more proof was needed that economic self-sufficiency was an irrational and unachievable quest, it was provided with the Emergency, though the war also focused Irish economic planners on change and adaptation. Industrial output fell by one fifth during the Emergency, rationing was introduced (in 1943 Ireland had only 28 per cent of its normal requirements for its beloved tea) and a wide-scale turf development plan was implemented. But it is fair to assert that stagnation, inflation and a fall in living standards were not the only developments which contained lessons for Irish economic planners. The concept of long-term planning was also given a boost by a recognition that the economy could be directed and guided, particularly in the context of general European post-war reconstruction and recovery plans.

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by

Matt Ridley

Published 17 May 2010

The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession

by

Peter L. Bernstein

Published 1 Jan 2000

Making It Happen: Fred Goodwin, RBS and the Men Who Blew Up the British Economy

by

Iain Martin

Published 11 Sep 2013

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by

Ruchir Sharma

Published 5 Jun 2016

Spiraling prices for staple foods and collapsing growth conspired to unseat the left-wing government in Argentina and the left-wing legislature in Venezuela. As the price of onions rule warns, rapidly rising prices for basics like onions doom economic prospects and often unseat leaders, particularly when high inflation is accompanied by falling growth and dwindling living standards. One simple rule of thumb is to watch out for countries where inflation is well above the emerging-world average, which has fallen recently to around 4 percent. In Argentina the combination of 25 percent inflation and zero growth toppled President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her populist party, which had been in power for twelve years.

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 1 Mar 2015

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by

Nicholas Shaxson

Published 10 Oct 2018

Oil: Money, Politics, and Power in the 21st Century

by

Tom Bower

Published 1 Jan 2009

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by

Carl Benedikt Frey

Published 17 Jun 2019

A History of Modern Britain

by

Andrew Marr

Published 2 Jul 2009

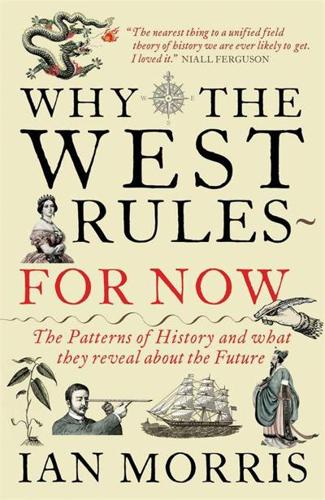

Why the West Rules--For Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future

by

Ian Morris

Published 11 Oct 2010