Good Times, Bad Times: The Welfare Myth of Them and Us

by

John Hills

Published 6 Nov 2014

• Benefit erosion: if benefit and tax credit rates grow more slowly than earnings, their cost to government falls as a share of national income – benefits that are a smaller share of average earnings are easier to pay for. The larger part of the overall saving, 57 per cent, comes from benefit erosion, with 43 per cent coming from fiscal drag. Figure 8.7: Effects of fiscal drag and benefit erosion over 20 years, if real earnings grew by 2 per cent per year The figure shows that the effects of fiscal drag are more important for those with higher incomes, reducing their incomes in this hypothetical scenario by 4 per cent. By contrast, for the bottom income groups, fiscal drag only reduces income by around 1 per cent. However, benefit erosion is far more important for those with low incomes, equivalent to more than 15 per cent of income for the bottom tenth and 17 per cent for the second group, but less than 1 per cent for the top two groups.

…

(Men born in 1958 and 1970) 7.11 The Great Gatsby curve 7.12 Education earnings premiums and earnings mobility 8.1 Losses from general cuts in social benefits and services or general tax increases averaging £1,000 per household, 2013–14 8.2 Distributional effects of Labour’s tax and benefit reforms from 1997 to 2009 compared to systems adjusted with prices or incomes 8.3 Effects of reforms to direct taxes, tax credits and benefits, May 2010 to 2015–16 (compared to price-linked base) 8.4 Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates of effects of tax and benefit reforms, January 2010 to April 2015, by household type 8.5 HM Treasury estimates of distributional effects of tax, benefit and public service changes by 2015–16 8.6 Distributional effects of direct tax and benefit changes in six countries, 2008–13 8.7 Effects of fiscal drag and benefit erosion over 20 years, if real earnings grew by 2 per cent per year 8.8 Effects of fiscal drag and benefit erosion if part of revenue used for tax cuts or benefit increases 8.9 ONS projections for percentage of population in each age range, 2011 and 2051 8.10 OBR long-term public spending projections, 2013 9.1 Spending on the welfare state, 2016–17 (£ billion) 9.2 Agreement that ‘social benefits and services make people lazy’, 2008 9.3 Commitment to work and benefit levels in different countries Glossary and acronyms BENEFIT EROSION Situation where benefits fall in value relative to average incomes, for instance, because they are increased each year in line only with prices, when incomes are growing in real terms CASH TRANSFERS Cash benefits and tax credits from government DECILE GROUP One-tenth of a population divided up in order of income, wealth, etc DEFINED BENEFIT Kind of pension where the amount paid depends on final salary (or other measure of earnings) rather than on investment returns DEFINED CONTRIBUTION Kind of pension where the amount paid depends on how much is paid in and on subsequent investment returns DISPOSABLE INCOME Income after direct taxes DIRECT TAXES Taxes paid by an individual or a household where the amount paid depends on their circumstances; they include Income Tax and National Insurance Contributions EFFECTIVE MARGINAL TAX RATE (OR DEDUCTION RATE) The proportion of any increase in earnings or other earnings that is taken in direct taxes and reduced means-tested benefits EQUIVALISED INCOME Income adjusted for family size FISCAL DRAG Situation where tax takes a greater proportion of people’s income because tax allowances and brackets grow more slowly than average incomes GINI COEFFICIENT Index of inequality (equal to zero if all households or individuals have the same and 1 or 100 per cent if one person has everything and the rest nothing) INDEXATION Adjustment each year of benefits, tax allowances, etc, for inflation or to keep in line with earnings or income growth INDIRECT TAXES Taxes where the amount paid does not depend on an individual’s income, but on things such as spending on particular goods, and often collected via businesses, such as Value Added Tax MARKET INCOME Income from wages, private pensions, interest and other investment income, before taxation or state benefits MEDIAN The middle level of income, wealth, etc, in a population, with half having more and half having less NET INCOME Income after direct taxes PEN’S PARADE Way of showing income or wealth distribution, with the height of each column in proportion to the amount received by each group in order PERCENTILE Value separating each 1 per cent of a population arranged in order of income, wealth, etc POVERTY TRAP Situation where people on low incomes gain little from any increase in gross income because of combined effects of taxes and reduced means-tested benefits PROGRESSIVE TAXATION Tax system where those with higher resources pay taxes that are a greater proportion of those resources QUINTILE GROUP One-fifth of a population divided up in order of income, wealth, etc REGRESSIVE TAXATION Tax system where those with higher resources pay taxes that are a lower proportion of those resources TRIPLE LOCK Guarantee that pensions rise each year by the higher of prices, earnings, or 2.5 per cent WELFARE STATE Public spending on and provision for healthcare (such as NHS), education, housing, personal care, pensions and cash benefits of all kinds (as opposed to ‘welfare’, as used in the US, referring narrowly to means-tested cash benefits for out-of-work working-age people) AHC After Housing Costs BHC Before Housing Costs BHPS British Household Panel Survey BSA British Social Attitudes survey CPI Consumer Prices Index CTC Child Tax Credit DCLG Department for Communities and Local Government DfE Department for Education DWP Department for Work and Pensions EMA Education Maintenance Allowance ESA Employment and Support Allowance EUROMOD Essex University tax and benefit microsimulation model FSM Free School Meals GDP Gross Domestic Product HB Housing Benefit HBAI Households Below Average Income HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs IFS Institute for Fiscal Studies ILO International Labour Organization (measures unemployment in terms of those looking for work, not just those claiming unemployment benefits) IS Income Support ISA Individual Savings Account JSA Jobseeker’s Allowance LAs Local Authorities LFS Labour Force Survey LHA Local Housing Allowance NMW National Minimum Wage NAO National Audit Office NSP National Scholarship Programme OBR Office for Budget Responsibility OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ONS Office for National Statistics PAYE Pay As You Earn PEP Personal Equity Plan RPI Retail Prices Index SERPS State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme TESSA Tax Exempt Special Savings Account UC Universal Credit VAT Value Added Tax WFP Winter Fuel Payment WTC Working Tax Credit WFTC Working Families’ Tax Credit Acknowledgements The time to research for and prepare this book was generously supported by a fellowship from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (on ‘Dynamics and design of social policies’, RES-05127-2034).

…

It is worth noting that even in the middle of the distribution benefit erosion effects (on things like tax credits and Child Benefit) are more important than fiscal drag. These kinds of effect are often how chancellors – in normal times, at least – can pull rabbits out of hats on Budget day, using the unseen boost to the public finances to pay for some much more visible initiative. But how the money is ‘given back’ has a critical effect on the distribution. Figure 8.8 shows what would happen if a little under half (£20 billion at 2006–07 income levels, equivalent to all of the amount coming from fiscal drag) was used in one of two different ways. That would still leave a net gain to the public finances of more than 2 per cent of GDP (for instance, as one way of coping with the pressures from ageing discussed in the next section).

The Wake-Up Call: Why the Pandemic Has Exposed the Weakness of the West, and How to Fix It

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 1 Sep 2020

Lyndon Johnson promised to create a “Great Society” (a phrase stolen from the title of a book by Graham Wallas, a close friend of the Webbs) by reducing poverty, banning racial discrimination, and improving educational opportunities. One reason why Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic left’s champion, wanted to stay in Vietnam was that he thought that it too could benefit from having a Great Society of its own.31 With America’s economy doubling in size every decade, economists agonized about “fiscal drag”—that if they didn’t spend money fast enough fiscal surpluses would eventually act as a deflationary break on economic growth—so they tried to spend even more.32 “I’m sick of all the people who talk about the things we can’t do,” LBJ said in March 1964, seven months before his landslide win over the libertarian Republican candidate Barry Goldwater: “Hell, we’re the richest country in the world, the most powerful.

Capitalism in America: A History

by

Adrian Wooldridge

and

Alan Greenspan

Published 15 Oct 2018

Kennedy nevertheless prepared the way for a spending boom by filling his Council of Economic Advisers with academic Keynesians. The council warned that the biggest problem facing the country was that the Treasury was raising too much money. The large federal surpluses would act as a deflationary brake on economic growth—a phenomenon known as “fiscal drag”—and the government needed to find ways of spending money. Predictably, there was no shortage of ideas for doing the spending: the 1964 tax cut, a program to put a man on the moon, and, of course, lots of social spending. JFK was succeeded by a man who had none of JFK’s caution. LBJ believed, with some justification, that Kennedy’s assassination required a grand gesture in response.

…

See national debt Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 243, 384 Federal Drug Administration (FDA), 284 Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), 244 federal government employees, 154, 156 federalism, 61–67, 157 Federalist Papers, 65, 157, 239 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), 235–36 Federal Reserve, 304, 324–25, 331, 372, 427 creation of, 156–57, 184–85 financial crisis of 2007–2008, 384–86 Great Depression and, 242–43 stock market crash of 1929, 235–36, 237, 238 Federal Reserve Act of 1913, 156–57, 184–85 Federal Trade Commission (FTC), 184, 209 Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, 184 FedEx, 333 female workers, 362–65, 434, 435, 437 Feminine Mystique, The (Friedan), 364 Fessenden, Thomas Green, 73 fiat currency, 38–39, 82, 161, 162–63 Fifties, 273–98, 435–36 financial crisis of 2007–2008, 27, 192–93, 223, 368–69, 373–85, 443 origins of, 376–85 financial cycles, 425–26 financial deregulation, 338–43 financial panics, 42, 135, 425. See also specific panics Firestone, Harvey, 110 first transcontinental railroad, 16, 18, 90, 114 “fiscal drag,” 303 Fischer, David Hackett, 60 Fisher, Irving, 221, 231, 232–33, 256 fishing industry, 36–37 Fishlow, Albert, 50, 53, 54 Fisk, James, 124, 130, 139 Fitch, John, 100–101 Fitzgerald, F. Scott, 195 Flagler, Henry, 128 Flexner, Abraham, 429 Florida Purchase, 5, 40 flu pandemic of 1918, 429 Fogel, Robert, 54 “fog of war,” 34 Food Administration, 186, 187 food preservation, 119–20 Ford, Gerald, 299, 309–10, 323, 328 Ford, Henry, 3, 9, 16, 107, 110, 119, 124, 126, 136, 142, 146–47, 190, 197, 198, 201–2, 268–69, 314, 360, 422, 439, 454 Ford Model T, 107, 194–95, 198 Ford Motor Company, 146–47, 209–10, 212, 294, 314, 422 Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922, 230 Ford Pinto, 312 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, 411 forestry, 37–38 Fountainhead, The (Rand), 277–78 Fourteenth Amendment, 159 fracking revolution, 356–59 franchising, 293 Franklin, Benjamin, 29, 43, 48 Freddie Mac, 379–81 freedmen, 86–87 freedom of contract, 159, 160, 163 Frick, Henry Clay, 136, 173–74 Friedan, Betty, 364 Friedman, Milton, 26, 236, 337 frontier thesis, 180 Fuel Administration, 186, 187 fuel efficiency, 313 Fuld, Dick, 374 futures markets, 120 Gal, Peter, 397 Galbraith, John Kenneth, 235, 295–96, 333 Galton, Francis, 49, 163–64 gambling, 265 Gans, Herbert, 296 Gardner, Erle Stanley, 265 Garfield, James, 167 garment industry, 322–23 Gates, Bill, 9, 323, 333, 338, 354, 356 GDP (gross domestic product), 2, 17 China and, 448 data and methodology, 13, 452–53 financial crisis and, 377, 382, 386 gross domestic savings and government social benefits, 407, 407–8 new workforce and, 361–62 Reagan and, 326–27 Union vs.

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by

Vito Tanzi

Published 28 Dec 2017

In spite of the high inflation, the unemployment rates had remained stubbornly high, or had even increased, while the growth rates of the economies had slowed down or, in some countries, had become negative. A prolonged slowdown or recession had taken hold in several economies, contributing to the increase in fiscal deficits and public debts. The increases in fiscal deficits had come in spite of the positive contributions to tax revenues that the so-called fiscal drag – the positive impact that a moderate rate of inflation has on tax revenue, in tax systems with progressive tax rates applied to unchanged nominal incomes – was having (see Tanzi, 1980b). What Ronald Reagan called the “misery index,” the summation of the unemployment and the inflation rates, became high, creating political difficulties for some governments and for the prevailing Keynesian ideology.

…

See 2007-2008 Financial Crisis Financial institutions executive compensation in, 168–69 financial penalties against, 158, 169–70 influence on governments, 113–14 regulations and, 126, 155, 157 rents and, 119 sanctions against, 157 “shadow banking,” 108, 119, 242, 329–30 “too big to fail” and, 84, 119, 168, 169 in UK, 157 in US, 126, 157 Financial instruments, complexity of, 106, 107, 108 Financial sector abuses in, 331 asymmetry in, 330–31 complexity of, 329–31 function of, 330 rents and, 330 securitization in, 330 “shadow financial sector,” 243 transaction activity in, 330 The Financial Times, 217, 352 Financial versus real investment, 106–7 432 Fine, Sidney, 18 Fines, 142 Finland Gini coefficient in, 317 marginal tax rates in, 376 Fiscal councils, 72–73, 272 Fiscal drag, 61 Fiscal policy, stabilization policies and, 237 Fiscal rules, 71–72, 272 Fiscal tools, 38 Fischer, Stanley, 113–14 Fisher, Irving, 46–47 Fishing industry, 149–50 Flat taxes, 381–82 Fogel, Robert William, 67–68 Food industry, 114–15, 167 Forbes, 38, 203, 342, 350 Forte, Francesco, 272 “Fracking,” 167, 283–84 France authorizations in, 137, 145 Cour des Comptes, 290 economic planning in, 27 ex post income distribution in, 118 “fake goods” in, 149 financial accountability in, 291 French Revolution, 89, 305 income inequality in, 306 marginal tax rates in, 376 occupational licensing in, 125–26 public spending in, 23–24, 53 regulations in, 279 wealth tax in, 342 welfare policies in, 43, 214 France, Anatole, 400 Francis (Pope), 28, 81 Frazer Institute, 60–61, 173 Free rider problem, 175–76 Free trade, 396–97 Friedman, Milton generally, 7–8, 60–61, 394 on basic minimum income, 212 on countercyclical policy, 61–62 on deficits, 72 on information in exchanges, 114–15 on irrationality, 141–42 on Keynes, 70 on limited role of government, 85, 313–14 on market, 34 on taxation, 367–68 Fundamental law of regulations, 278–79 Galbraith, John Kenneth, 3, 45–48 Gangs, 97–98 Gates, Bill, 196, 326, 356–57 Index Geithner, Tim, 113–14, 156 General Electric, 377 General Theory (Keynes), 46–47 Genetically modified food, 182–83 Germany authoritarian government in, 23 economic planning in, 27 “fake goods” in, 149 Gini coefficient in, 317 laissez faire in, 18 marginal tax rates in, 376 reforms in, 22 “revolving door policies” in, 335–36 unions in, 231 welfare policies in, 218, 219 welfare states in, 20 Gini, Corrado, 19 Gini coefficient.

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by

Robert Skidelsky

Published 13 Nov 2018

Eisenhower had allowed the surplus on the full employment budget to creep up, and with it American unemployment, which reached 7 per cent by the end of the 1950s. In 1960 the President’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated that the economy was using only 90 per cent of its potential output, because of ‘fiscal drag’. The policy of setting tax rates and spending totals to balance the budget at a high level of employment, and leaving them there, was not enough, because if tax rates were left unchanged, the full employment surplus automatically expanded with the growth of the economy, making the actual budget increasingly deflationary.

…

., 243–4 technological change, 130, 299, 300, 370–72 Thatcher, Margaret, 1, 181, 186–7, 249, 292, 319 think-tanks, financing of, 13 Thomas, Ryland, 281–2 Thornton, Henry, 46–7, 68, 278 Thurow, Lester, 151 Tobin, James, 138, 153, 154–5 Tooke, Thomas, 49 Torrens, Robert, 49 trade, international balance of trade, 37, 76, 78 and capital flows, 56–7, 332–5, 333, 334, 335, 336–43, 337 see also global imbalances commodity structure of (before 1914), 56 and Cunliffe Report (1918), 54–5, 102, 145 Hume’s ‘price-specie-flow’ mechanism, 37–8, 53, 54, 104, 285, 332 mercantilist view, 36–7, 78–81, 380 nineteenth-century adjustment mechanism, 54–5, 58 Ricardo’s doctrine of comparative advantage, 79, 88, 378, 379 sterling as main vehicular currency, 43, 58–9, 101 between Western Europe and ‘peripheries’, 56–7 trade unions, 16, 56, 130, 167 capital–labour co-operation, 147, 167 destruction of from 1980s, 169 and fall of Heath (1974), 168 in the Keynesian era, 131, 147, 148, 161, 303, 304 in post-W W1 period, 96, 100 power of shop stewards in U K, 147 Trichet, Jean-Claude, 275 Triffin, Robert, 161 Trouble Asset Relief Program, 217 Trump, Donald, 192, 316*, 352, 373, 379, 381 Turner, Adair, 246, 285, 307, 366 under-consumption theory, 293–6, 297–8, 303–6, 370 unemployment during 2008 crisis, 261–2 490 i n de x in classical theory, 10, 37, 56, 96, 118, 121–2, 123, 128, 129, 130, 138, 172 economic deterioration (1969–73), 164–6 and emigration to New World, 15, 56, 58 employment targets, 141–2 during Great Moderation, 4, 202, 348 growth Keynesianism (1960–70), 151–3 Hitler’s reduction in, 111, 112, 129–30 increases from 1980s, 32, 186–7 Keynesian full employment phase (1945–60), 141–8 and Keynesian revolution, 75, 76, 98, 103, 129–30 as main inter-war challenge, 8, 96, 97, 97–8, 103–4, 107, 108–24, 129–31 Marxist view of, 128–9, 130, 304, 350 ‘natural’ rate of, 2, 163, 177, 181, 192–3, 197, 206, 208, 222, 232–3, 384 oil price shock (1973–4), 166 Phillips Curve, 144–5, 147, 162, 163, 180, 194, 205, 205–12, 207 as primary government responsibility, 87–8, 98, 130–31, 139–40, 141–6, 147, 150, 168–9, 303 and protectionism, 378 and quantitative easing, 269–70, 270 rates (1929–38), 112 and ‘speculative demand for money’, 36 word in Oxford English Dictionary, 9 United States and 2008 crash, 217, 218, 241–2, 242 491 adoption of Keynesian policy, 141, 143–4 adopts full gold standard (1879), 50 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009), 242 bimetallist controversy, 44, 50–52 capital–labour co-operation, 147 Civil Rights movement, 149 current account deficit, 333, 334, 336, 338–41, 342 dollar as main reserve currency, 338 dollar convertibility into gold, 27 Economic Stimulus Act (2008), 242 European catch-up (after 1945), 156–7, 158–9 European Payments Union, 159 excess demand conditions in mid-1960s, 163, 164, 166 fall in wages (1929–32), 122 Fanny Mae & Freddie Mac nationalized (2008), 217, 256 ‘fiscal drag’ in 1950s/early 60s, 151, 152–3 fiscal formula (1945–61), 143 and free trade, 9, 90 Full Employment Act (1946), 141 GDP per capita growth (1919–2007), 154 Glass–Steagall Act (1933), 319, 361, 362 and Great Depression, 97, 98, 127 growth Keynesianism (1960–70), 148–9, 151–3, 162–3, 164 hegemony in post-war world, xviii, 139, 158–60, 162–3, 374 housing bubble (from 2001), 304–5 Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ programme, 153, 161, 163, 164 National Homeownership Strategy (1994), 309 nineteenth-century protectionism, 89–90 i n de x United States – (cont.) post-crash bank liquidity ratios, 364 as post-W W1 creditor, 95, 103, 159 Reagan’s deficits, 186, 190–91 recession of early 1980s, 186–7 resurgence of protectionism in, 373, 379, 380, 381–2 role in first phase of golden age (1950s), 159–60 Roosevelt’s New Deal, 16, 129–30 Schlesinger Jr’s epochs, 15 Security and Exchange Commission, 320–21 sharp rise in inequality since 1970s, 288–9, 289, 299–300, 300 university campus revolts (1968), 164 see also Federal Reserve, US value at risk (VaR) framework, 314–15, 315, 330 Verdoorn’s law, 150 Vickers, Sir John, 362 Victorian fiscal constitution, 9, 29, 59, 76, 85–8, 86, 106 Vietnam War, 153, 161, 163, 164 Viner, Jacob, 131 Volcker, Paul, 185–6, 191, 307, 362 Wall Street Crash (1929), 3, 97, 104–6 Walras, Leon, 10, 173, 181, 385 warfare British W W1 borrowing, 95, 97, 106–7 bullionist vs ‘real bills’ controversy, 44, 45–9 classical view of, 73, 74, 75, 78, 79, 81–2, 83, 84 eighteenth century British victories over France, 43, 80, 81 and mercantilism, 37, 74, 75, 78, 79–82 post-W W2 catch-up process, 156–7, 158 and recoinage crisis (1690s), 41, 42 relative absence of (1871–1914), 58, 85 and Rothschild lending, 91 ‘strategic industry’ argument, 379 war debt, 43, 45–8, 80–86, 86, 87, 91, 95, 97, 106–7, 129 Warwick, University of, xvii Washington consensus, 198 Webb, Beatrice and Sidney, The Decay of Capitalist Civilisation, 96 Weidmann, Jens, 257 welfare state, 9, 15–16, 96, 149, 291, 374 Bismarck’s Germany, 89 Liberal government’s social reforms (1900s), 87 Where Does Money Come From?

Understanding Asset Allocation: An Intuitive Approach to Maximizing Your Portfolio

by

Victor A. Canto

Published 2 Jan 2005

The tax environment was not perfect back then, with Congress having passed what I considered anti-growth and anti-savings tax increases earlier in the decade. Yet, the U.S. economy and stock market were surging at mid-decade, with inflation holding near two percent. My argument, then and now, is that inflation is a tax on savings and investment, and low inflation acts like a tax cut—so much so that it can offset the fiscal drag of the high taxes that might be in place. I use this example to illustrate top-down thinking, which is not only critical for economists but also for investors of all stripes. In the “macro” top-down world of investing, all the great forces within an economy exert their unique pressures, combining to give an economy its individual stamp—its look, its feel, its function, its promise.

The Verdict: Did Labour Change Britain?

by

Polly Toynbee

and

David Walker

Published 6 Oct 2011

Labour got by thanks to Tory taxes. The IFS estimated a third of the increase in tax revenues as a share of GDP since 1997 came from tax started by the Tories and continued under Labour – such as the fuel and tobacco duty escalators. A third came from Labour’s own tax increases and a third from growing incomes or ‘fiscal drag’, where earnings increases push taxpayers into higher tax brackets. When it did increase National Insurance in 2001, clearly earmarking it for health, the public applauded. The pollsters called it the most popular budget for twenty-five years and this could have been a lesson for Labour. NI was, after all, a kind of income tax.

The Skeptical Economist: Revealing the Ethics Inside Economics

by

Jonathan Aldred

Published 1 Jan 2009

There is much evidence that this outcome (high income elasticity and low price elasticity) holds for education and health in the US. See for instance Ryan (1992). 44 Triplett and Bosworth (2003, 2005). 45 For recent evidence from US health care for this ‘two service sectors’ argument, see Frogner (2008). 46 See for example Krugman and Wells (2006). 47 Baumol (2001), p24. 48 This ignores so-called ‘fiscal drag’ arising from tax-free allowances and higher-rate tax thresholds remaining unchanged in the face of rising incomes, so that a larger proportion of income is in fact taken in tax (another way of seeing this is to realize that the value of the tax-free allowance falls in real terms). I ignore this possibility because it raises relatively little additional revenue, and is in any case best understood as a hidden increase in tax rates. 49 Baumol (1993), p22. 50 Baumol (1993), p25.

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by

David Hale

and

Lyric Hughes Hale

Published 23 May 2011

In 2010, the recession had reduced the tax share of GDP to only 14.8 percent while the Obama stimulus program had boosted the spending share of GDP to 25.4 percent. The resolution of fiscal policy uncertainties will play a major role in shaping the business cycle post-2010. If the government were to introduce a 10 percent VAT in 2012 or 2013, it would depress consumer spending. The Fed might have to offset the fiscal drag by easing interest rates. If there is no change in fiscal policy, bond yields could rise to 7–8 percent and jeopardize the upturn in the housing market. Large interest rate hikes would also raise the cost of capital and depress investment. There is no way to predict exactly how these policy uncertainties will play out.

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by

Charles Wheelan

Published 18 Apr 2010

Let’s step out of our cynical mode for a moment and return to the idea that government has the capacity to do many good things. Even then, when government is doing the things that it is theoretically supposed to do, government spending must be financed by levying taxes, and taxes exert a cost on the economy. This “fiscal drag,” as Burton Malkiel has called it, stems from two things. First, taxes take money out of our pockets, which necessarily diminishes our purchasing power and therefore our utility. True, the government can create jobs by spending billions of dollars on jet fighters, but we are paying for those jets with money from our paychecks, which means that we buy fewer televisions, we give less to charity, we take fewer vacations.

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by

Judith Stein

Published 30 Apr 2010

And Volcker’s soaring interest rates did their part in raising the inflation rate. “A MOST WASTED YEAR” Carter himself thought that government frugality could reduce inflation. The only new spending in his 1981 budget was $4 billion for defense, added after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979; on the revenue side no attempt was made to offset the fiscal drag that pushed people into higher tax brackets. Consumption was further restrained by higher social security taxes. But the president aimed in the wrong direction. Higher energy prices—oil more than doubled, to $24 a barrel—and 17 percent interest rates produced an inflation rate of nearly 20 percent at the end of February.

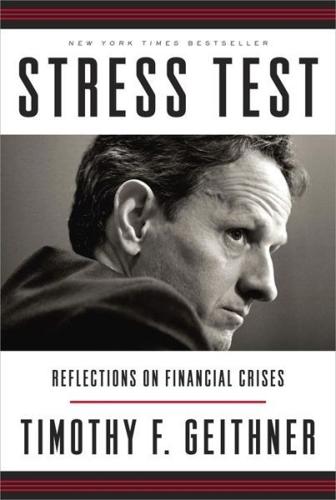

Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises

by

Timothy F. Geithner

Published 11 May 2014

THE UNITED States was in a lull, too, economically and politically. Growth was steady but unimpressive. Unemployment had declined to 8.3 percent, better than double digits but still way too high. The Fed and other forecasters kept predicting that the recovery was about to take off, but Europe, our fiscal drag, and our other economic headwinds kept holding it back. Inside the administration, we had countless meetings to discuss ways to boost jobs and growth. But with Republicans now in charge of the House—and focusing mainly on symbolic votes repealing Obamacare, financial reform, and other Obama achievements—there weren’t many realistic legislative options.