Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone

by John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai · 25 Jul 2025

many merits, target date funds are not perfect. Some of these funds err on the side of caution and assign too high a weight to fixed-income markets for young investors. Others charge high fees for active equity management with little gain in performance. And while they condition asset allocation on an

…

. I’ve been doing so.… They want full payout for the house and that is something that I don’t have. I’m on a fixed income.… They are able to take people’s homes by asking for large sums of money and proceeding with foreclosure once they don’t get it

…

to solve the investor’s lifecycle asset allocation problem, by leaning more heavily towards equities early in working life and becoming more conservative—shifting toward fixed-income securities—as the investor approaches retirement. Funds like this, made available within a retirement savings account, make it easier to fund retirement and provide households

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

by Kenneth Rogoff · 27 Feb 2025 · 330pp · 127,791 words

secondary market at a small discount. At the time of the Russian default, LTCM held a position in an astounding 5 percent of the global fixed-income market, which led to a liquidity panic that briefly froze the U.S. Treasury bill market, the world’s largest and most liquid financial market

Gambling Man

by Lionel Barber · 3 Oct 2024 · 424pp · 123,730 words

’t know’ or, even more irritating, ‘OK, so let me tell you how this goes …’ Anshu Jain was known at Deutsche as ‘the father of fixed income’, better known as bond trading. After Edson Mitchell died in a plane crash just before Christmas 2000, leaving a gaping hole in Deutsche’s senior

Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice

by Pierre Vernimmen, Pascal Quiry, Maurizio Dallocchio, Yann le Fur and Antonio Salvi · 16 Oct 2017 · 1,544pp · 391,691 words

the system is flawed because the real return to investors is zero or negative. Their savings are insufficiently rewarded, particularly if they have invested in fixed-income vehicles. The savings rate in a credit-based economy is usually low. The savings that do exist typically flow into tangible assets and real property

…

risky and the β of Orange is now below 1. 2. Parameters behind beta By definition, the market b is equal to 1. β of fixed-income securities ranges from about 0 to 0.5. The β of equities is usually higher than 0.5, and normally between 0.5 and 1

…

and valuation of securities After having studied the yield curve, it is easier to understand that the discounting of all the cash flows from a fixed-income security at a single rate, regardless of the period when they are paid, is an oversimplification, although this is the method that will be used

…

throughout this text for stocks and capital expenditure. It would be wrong to use it for fixed-income securities. In order to be more rigorous, it is necessary to discount each flow with the interest rate of the yield curve corresponding to its

…

conditions that are very likely to have changed since the original issue. Section 20.3 Floating-rate bonds So far we have looked only at fixed-income debt securities. The cash flow schedule for these securities is laid down clearly when they are issued, whereas the securities that we will be describing

…

; market rates: the lower the level of market rates, the higher a bond’s modified duration. Modified duration represents an investment tool used systematically by fixed-income portfolio managers. If they anticipate a decline in interest rates, they opt for bonds with a higher modified duration, i.e. a longer time to

…

fall in interest rates leads to a loss on the reinvestment of coupons and to a capital gain. Intuitively, it seems clear that for any fixed-income debt portfolio or security, there is a period over which: the loss on the reinvestment of coupons will be offset by the capital gain on

…

. Agrawal, C. Mann, Explaining the rate spread on corporate bonds, Journal of Finance, 56(1), 247–278, February 2001. F. Fabozzi, The Handbook of European Fixed Income Securities, 8th edn, McGraw-Hill, 2011. J. Finnerty, D. Emery, Debt Management: A Practitioner’s Guide, Oxford University Press, 2001. J. Hand, R. Holthausen, R

…

yield spreads: Default risk or liquidity? New evidence from the credit default swap market, Journal of Finance, 60(5), 2213–2247, October 2005. P. Veronesi, Fixed Income Securities: Valuation, Risk, and Risk Management, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010. And also: www.fitchratings.com www.moodys.com www.standardandpoors.com www.spreadresearch.com

…

. Stein, Convertible bonds as backdoor equity financing, Journal of Financial Economics, 32(1), 3–21, August 1992. On exchangeable bonds: F. Fabozzi, The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 8th edn, McGraw-Hill, 2011. On hybrid securities: F. Black, M. Scholes, The pricing of options and corporate liabilities, Journal of Political Economy, 81

…

, who coordinates all aspects of an offering; the global coordinator is also lead manager and usually serves as lead and book-runner as well. For fixed-income issues, the global coordinator is called the arranger; the lead manager is responsible for preparing and executing the deal. The lead helps choose the syndicate

…

de l’association française de finance, 31(2), 51–92, December 2010. J. Helwege, P. Kleiman, The pricing of high-yield debt IPOs, Journal of Fixed Income, 8(2), 61–68, September 1998. R. Taggart, The growing role of junk bonds in corporate finance, in D. Chew (Ed.), The New Corporate Finance

…

on corporate investment, Journal of Finance, 54(6), 1939–1967, December 1999. P. Fernandez, Levered and unlevered beta, Journal of Applied Finance, 2005. K. Garbade, Fixed Income Analytics, MIT Press, 2002. L. Jui, R. Merton, Z. Bodie, Does a firm’s equity returns reflect the risk of its pension plan?, Journal of

…

in market value of the underlying asset (or a fall in interest rates). The notion of position is very important for banks operating on the fixed-income and currency markets. Generally speaking, traders are allowed to keep a given amount in an open position, depending on their expectations. However, clients buy and

Stigum's Money Market, 4E

by Marcia Stigum and Anthony Crescenzi · 9 Feb 2007 · 1,202pp · 424,886 words

model for options pricing. This model, which was developed for the pricing of options on equities, must be modified in order to be applied to fixed-income securities. Also, theoreticians—rocket scientists or quants to the Street—are constantly tinkering with this model to improve its accuracy and extend its reach.

…

in immunizing portfolios, in hedging trading positions, in comparing investment alternatives, and in performing various other analyses. Duration has become a key measurement for fixed-income securities; and it is a key element in the investment decision-making process. It’s impossible to derive results concerning duration without using simple calculus

…

sentiment can occur in any market, including the bond market in which tracking market sentiment is helped immensely by tracking the collective duration levels of fixed-income portfolios. Since the bond market is largely an institutional business, aggregate duration surveys conducted by Wall Street firms and economic research firms are a

…

microcosm of the risk profiles of the universe of fixed-income portfolios. Indeed, most duration surveys include portfolios that have a combined total of several hundred billion dollars or more in assets. The best and

…

curve to display over its entire price-yield range. REVIEW IN BRIEF • Duration and convexity are key considerations in the decision to buy and sell fixed-income securities. • Duration measures a bond’s price sensitivity to changes in interest rates, although not precisely. Nevertheless, duration provides a close approximation if the

…

when calculating price changes that will occur when yield changes are large. • Duration can be used as a gauge of market sentiment, which can help fixed-income portfolio managers in the investment decision-making process. PART TWO The Major Players Copyright © 2007, 1990, 1983, 1978 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

…

of risk that a trading operation can take. These can be defined as either market risks or credit risks. In a money market or other fixed-income portfolio, these risks can be defined by portfolio duration, average maturity, convexity, foreign-exchange exposure, or credit ratings, for example. In a large organization

…

used for a variety of purposes other than as pure investments. One of these is for the financing of Wall Street’s large holdings of fixed-income securities. The Street’s primary dealers finance their holdings via repurchase agreements (repos), which are essentially short-term loans secured by collateral deemed safe

…

a notional value of over $200 billion (2 million contracts × $100,000 of notional value per contract). No other futures contract on any other fixed-income security comes close. For example, the number of federal agency futures outstanding is scant at only a few thousand contracts. Many loans granted to both

…

Greenspan’s tenure had been institutionalized. The Fed’s Impact on Spread Products The Federal Reserve can greatly influence the performance of spread products, or fixed-income securities other than Treasuries such as agency securities, corporate bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and emerging markets securities. These securities are called “spread” products because

…

, or, as it is formally called, the Bloomberg Professional system, has arguably been the most important information, analytics, and trading system used by the fixed-income community over the past two decades. The Bloomberg system is crammed with a deep database and functionality, but in its infancy it was initially blocked

…

a vital role in the money market, connecting participants throughout the world. • Information, analytics, and trading systems such as Bloomberg are widely used in the fixed-income community, providing an array of tools for professionals. CHAPTER 11 The Investors: Running a Short-Term Portfolio Copyright © 2007, 1990, 1983, 1978 by The

…

U.S. Aggregate Index. Indeed, Lehman claims that over 90% of U.S. investors use one or more of its fixed-income benchmarks to assist in analyzing their portfolios. Fixed-income managers use the indices largely to compare how their portfolios are constructed and to compare performance. The indices are an important resource

…

knowledgeably buy a lesser-grade commercial paper that other portfolio managers wouldn’t touch. Portfolio managers face many choices with respect to what type of fixed-income security they should buy. The decision often rests on expectations regarding the economy and hence the outlook for monetary policy. 2 Commercial paper, as

…

$2.29 trillion in reverses. During the quarter, over $99.5 trillion in repo trades were submitted by the Government Securities Division of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), an SEC-registered clearing agency that facilitates orderly settlements in the U.S. government securities market and tracks repo trades settled through

…

two things. First, dealers were running huge matched books. Second, in March 2006, dealers were borrowing money to fund other activities including their holdings in fixed-income securities. Data from the New York Fed, which collects such statistics on a weekly basis, show that dealers were short $113 billion Treasuries, but

…

appear to suggest that dealer financing has increased sharply during the period. Adrian and Fleming counter this simplistic analysis, arguing that dealer borrowing involving fixed-income securities grew only modestly in recent years and that the increase is unrelated to an increase in net positions held.12 The researchers assert that

…

Current Issues in Economics and Finance, March 2005. sharp increase in net repo financing—the net amount of money primary dealers borrow through repos on fixed-income securities (calculated as repos minus reverses)—net repo financing is an incomplete and potentially misleading measure of dealer leverage. One reason is that net repo

…

financing, which is measured as securities out minus securities in. Net financing measures the net amount of funds that primary dealers borrow through all fixed-income security financing transactions. Figure 13.11 shows the sharp difference between the amount of net repo financing and net financing during the period 1994–2004

…

amount of bond issuance increased compared to the previous year, a factor that tends to boost volume. Record amounts of foreign purchases of U.S. fixed-income assets also boosted volume. Over time, three of the biggest factors affecting trading volume in Treasuries include: the Federal Reserve, the state of the

…

half of Treasuries are held by foreign investors. Another factor that boosts Treasury volume is its transparency. Treasury prices are more transparent than any other fixed-income instrument, meaning that both the price and size of the bids and offers for Treasury securities are readily discerned. Moreover, the bid and offer

…

prices for Treasuries tend to be quite narrow relative to other fixed-income securities, which also boost their attractiveness. In fact, in a study the Federal Reserve estimates that the average bid-ask spread for Treasuries is

…

their trading activities, cash, futures, and financing market positions in Treasury and other securities. Primary dealers tend to carry larger amounts of inventories of fixed-income securities and a greater variety of these securities. The dealers also tend to have a greater ability than smaller market participants to participate in offerings

…

bidders take delivery of their Treasury securities directly from the Treasury, although about 75% of all auction deliveries are made to dealers indirectly through the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), which is a clearing agency registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission that acts as the central clearing corporation for Treasury

…

their respective clearing banks. Now, trades done through brokers are to be cleared via a netting process run by the Government Securities Division of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation, which we discussed earlier. The Government Securities Division clears, nets, settles, and manages risk arising from a broad range of U.S.

…

type of system, the dealers act as principals, meaning that they buy and sell securities for their own account. The full range of major fixed-income products are currently being offered through this system. This system enables investors to peruse a dealer’s inventory of bonds, thereby helping customers locate bonds

…

led by the explosive growth of TradeWeb, a New York-based online trading firm that enables institutional customers to buy and sell various types of fixed-income securities electronically with multiple primary dealers. In early 2006, over 2,200 of the largest buy-side institutions were using TradeWeb to both price

…

themselves reports on inflation. Inflation, after all, is the bane of the bond market because it erodes the value of the cash flows associated with fixed-income securities. Yields are therefore greatly affected by inflation expectations, which are influenced daily by many factors. The inflation data are enormously influential on the

…

7% would be the more attractive investment. Factors That Cause Real Yields to Fluctuate There are many factors that determine the real yield on a fixed-income security. (For simplicity, we again focus on government bonds rather than corporate and other types.) Here is the list of factors: • Inflation expectations • Opportunity

…

much more than bills, at $997 billion, and bonds, at $526 billion. • Primary dealers customarily hold net short positions in Treasuries as hedges against other fixed-income securities that they hold. Indeed, dealers were net short in every week during the 4½ years ending March 2006. • In various studies, the yield curve

…

accelerated pace at which federal regulators began to approve new contracts led to a rapid expansion in the menu of securities—financial futures, options on fixed-income securities, and options on futures—being traded. The specifications of the principal financial futures contracts and of options on those contracts that are traded

…

. Commercial traders in Treasuries are the true end users of the contracts: the hedgers and those who are in the business of buying and selling fixed-income securities. Commercial traders are known as “smart money.” They can be primary dealers, insurance companies, pension funds, and the like. Noncommercials are considered speculators.

…

speculative traders have relatively less information in hand than do commercial traders with respect to market fundamentals and the true level of underlying demand for fixed-income securities. In addition, speculators frequently have a herd mentality and are therefore more likely to alter their positions when commercial players ignite a change

…

segments of the bond market, including the mortgage and corporate securities markets. • Futures are also used as a vehicle for boosting the returns of fixed-income portfolios via strategies designed to take advantage of volatility in the interest-rate environment, yield curve shifts, and so on. Calendar spreads and the NOB

…

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Alex Edmans is a Ph.D. candidate in financial economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and previously worked in both fixed income and investment banking for Morgan Stanley. FIGURE 17.1 Puts and calls: rights, contingent obligations, and features (European call) or up to the maturity

…

May 2005, a number of prominent international bond issuers known to draw significant buying interest from the world’s central banks, issued more SEC-registered fixed-income securities than nonregis-tered securities (Table 18.1). For example, the Republic of Italy registered over 90% of its dollar issues during the period.

…

terms. For issuers, the growth of the asset-backed securities market has significantly expanded the pool of funding sources to include the broad array of fixed-income investors, a market consisting of $26 trillion in mid-2006. Commercial banks have become increasingly reliant upon securitization as a way of diversifying their

…

for all projects, debt issuance costs, and the cost of purchasing commercial bond insurance. Moving to Book Entry and Real-Time Reporting As with other fixed-income securities, municipal notes used to be issued as bearer notes (Figure 25.1). For securities of such short duration, registration wasn’t worth the

…

free money fund companies to purchase securities from their portfolios to prevent losses to investors. Earlier in 1994, which was a tumultuous year in the fixed-income markets with yields rising sharply, more than 20 money funds were negatively impacted by investments in money market derivatives. Many of these funds needed

…

trading. actuals: The cash commodity as opposed to the futures contract. actual/360: The day-count convention applied to the calculation of interest on a fixed-income security. Calculations are based on a 360-day calendar. This day-count convention is applied in the Eurosystem’s monetary policy operations. ACUs (Asian

…

provision that permits conversion to the issuer’s common stock at some fixed exchange ratio. convexity: The slope of the price-yield relationship for a fixed-income security. Convexity is normally positive, but it can be negative. corporate bond equivalent: See equivalent bond yield. corporate taxable equivalent: Rate of return required

…

selling the proceeds of the investment forward for dollars. credit default swap (CDS): A credit derivative that enables parties to exchange the credit risk of fixed-income securities. CDS buyers purchase protection against a bond’s default, paying a fee to protection sellers. credit enhancement: The backing of paper with collateral,

…

bids through the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as well as any customer who submits through a primary dealer. inflation-index security: A fixed-income security whose cash flows and principal value are linked to an inflation index such as to a particular consumer price index. interbank: When interbank refers

…

Fedwire Funds Transfer Service vs. CHIPS FFB (see Federal Financing Bank) FHCs (see financial holding companies) FHLB (see Federal Home Loan Bank System) FICC (see Fixed Income Clearing Corporation) FICO (see Financing Corporation) Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) asset-backed paper loan participations financial futures (see also futures) financial holding companies (

…

financial stability, Fed Financing Corporation (FICO) S&L crisis financing gap financing use, Treasury fine-tuning quotes, brokers’ market First Report on the Public Credit Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), Treasury securities float, Fed floating-rate CDs floating-rate MTNs floating-to-floating swaps, money market swaps flower bonds, Treasury securities FOMC

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

of the investment analyst may be thought to have little or no concern with market prices. His typical function is the selection of high-grade, fixed-income-bearing bonds, which upon investigation he judges to be secure as to interest and principal. The purchaser is supposed to pay no attention to their

…

common stocks, whereas, so far as investment practice is concerned, the former undoubtedly belong with bonds. The typical or standard preferred stock is bought for fixed income and safety of principal. Its owner considers himself not as a partner in the business but as the holder of a claim ranking ahead of

…

world hadn’t yet heard of Warren Buffett, for example, and only a small circle recognized his teacher at Columbia, Ben Graham. The world of fixed income bore little resemblance to that of today. There was no way to avoid uncertainty regarding the rate at which interest payments could be reinvested because

…

dogma and too many formulas incorporating numerical constants like “multiply by x” or “count only y years.” My more recent reading of the chapters on fixed income securities in the 1940 edition of Security Analysis served to remind me of some of the rules I had found too rigid. But it also

…

of investment standards. • At least through 1940, there were well-accepted and very specific standards for what was proper and what was not, especially in fixed income. Rules and attitudes governed the actions of fiduciaries and the things they could and could not do. In this environment, a fiduciary who lost money

…

turn toward what we would consider very modern thinking—it references some absolute standards but dismisses many others and reflects an advanced attitude toward sensible fixed income investing. Investment Absolutes The 1940 edition certainly contains statements that seem definite. Here are some examples: Deficient safety cannot be compensated for by an abnormally

…

apparent quality and safety alone shouldn’t be expected to make some things successful investments or rule out others. Here are several examples: [Given that fixed income securities lack the upside potential of equities,] the essence of proper bond selection consists, therefore, in obtaining specific and convincing factors of safety in compensation

…

followed by intelligent risk bearing (as opposed to knee-jerk risk avoidance). Our Methodology for Bond Investing To examine the relevance of Security Analysis to fixed income investments, I reviewed Graham and Dodd’s process for bond investing, and I compared their approach to the one applied by my firm, Oaktree Capital

…

an insurance company. (pp. 165–166) To wrap up on the subject of investment approach, we feel the successful assumption of credit risk in the fixed income universe depends on the successful assessment of the company’s ability to service its debts. Extensive financial statement analysis is not nearly as important as

…

refute existing rules of investing, substituting common sense for “accepted wisdom,” that great oxymoron. To me, this represents the greatest strength of the section on fixed income securities. In the end, Graham and Dodd remind us, “Investment theory should be chary of easy generalizations.” (p. 171) Security Analysis through the Years Many

…

returns. Graham and Dodd were among the first to apply careful financial analysis to common stocks. Until then, most serious investment analysis had focused on fixed income securities. Graham and Dodd argued that stocks, like bonds, have a well-defined value based on a stream of future returns. With bonds, the returns

…

I decided it was time to pick up Graham and Dodd and see what all the buzz was about. The first 300 pages dealt with fixed income securities, which I have seldom owned and were of little interest to me. The equity section seemed dated: topics such as determining the earnings power

…

1980s. The inflationary spiral ultimately led to higher interest rates and large losses for bond investors. Second was the expansion of the fixed income markets and the proliferation of innumerable fixed income securities that created opportunities for value investing in the bond market for those willing to sift through vast numbers of similar instruments

…

yourself full-time to researching investments, you’re probably better off engaging some professional assistance. The prolific pair also advised institutions to invest solely in fixed income investments, if doing so would fulfill their needs. Fortunately, for universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, men such as Jack Meyer, David Swensen, and

…

first glance, those two ideas appear to be antithetical, but Marks says that’s not the case. His introduction to Part II, which is about fixed income investments, explains how the ideas in Security Analysis can be applied profitably to today’s corporate bond market. J. Ezra Merkin, managing partner of Gabriel

House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street

by William D. Cohan · 15 Nov 2009 · 620pp · 214,639 words

account was “one or two million light.” In 2007, Peloton's asset-backed securities fund returned 87 percent to investors and was named the best fixed-income fund of the year by EuroHedge magazine. But the fund closed in February 2008 after its investments in Alt-A mortgages fell precipitously in the

…

it was. “February 29 was the day Peloton blew up,” explained Paul Friedman, a Bear senior managing director and the chief operating officer of the fixed-income division, “and so you had a huge liquidation, us and others, of really high-quality stuff that went at really distressed prices. There were a

…

we think the P&L's going to be, and the status of funding and liquidity. Nothing formally prepared, just brief discussions around equity repo, fixed-income repo, commercial paper, bank funding, some of the things that were still hanging in.” Rumors were now rife about how other Wall Street firms' clients

…

other senior Bear executives joined the party, including Elizabeth Ventura, head of media relations, Mike Solender, general counsel, and Ken Kopelman, general counsel of the fixed-income division. There was “lots of talk with lots of lawyers,” Friedman said, “but to take this firm and have a rational bankruptcy plan in six

…

market environment.” Moody's and Fitch also cut their ratings on Bear Stearns's debt. “What their rating is now is irrelevant,” Andrew Harding, chief fixed-income investment officer at Allegiant Asset Management, in Cleveland, told Bloomberg. “Whether it's BB, AAA or A, I just think it's a response to

…

heard from Steve Begleiter and Sam Molinaro that the board had approved the $2 deal. Then Jeff Mayer, one of the two heads of the fixed-income division, called everyone together. “Mayer got up on the trading desk and called everybody over and told them about it,” Friedman said. “He said, ‘

…

out of body experience.” Just after midnight, as the few remaining Bear Stearns stalwarts were trickling out of 383 Madison, James Egan, head of Global Fixed-Income Sales, sent an e-mail to his bosses, Craig Overlander and Jeff Mayer, and a few others, including Tom Marano. “I had always heard

…

focus on cost and risk controls. Only those business lines that had proven an ability to make money—such as clearing, the brokerage, and the fixed-income division—were given more capital, albeit parsimoniously. “A firm philosophy was to never anticipate what businesses would be good or bad,” explained one longtime senior

…

of revelatory information about the firm, the vast majority of which had never before been public. The filing revealed that the firm was primarily a fixed-income shop—involved in the buying, selling, trading, and underwriting of debt securities issued by the U.S. Treasury, affiliated government agencies, municipalities, and corporations—

…

got rid of the third guy.” Paul Friedman had a ringside seat for Cayne's seriatim and ruthless eviscerations of Friedman's bosses in the fixed-income division. “He forced out over the years a list of extraordinarily bright people—who could have provided big amounts of leadership—because they threatened him

…

,” said Friedman, who now works for Michaelcheck at Mariner Capital. “My first boss, Denis Coleman, who when I got there was head of fixed income, was viewed by many as the ultimate successor to what was then Ace and Jimmy, but Jimmy was already taking command. He was forced out

…

Bill Michaelcheck, forced out by Jimmy in a to-do over compensation, partnership points, hierarchy, succession, who knows? Eased out. Whoever was the head of fixed income, he always took the number two and strengthened them, and used him to push out the head. Then the number two would become the number

…

highly self-assured former national high school bridge champion, was one of the people Cayne spotted and then nurtured. Spector was a trader in the fixed-income department when Cayne marked him for future greatness. “What appealed to me is this guy's making a lot of money,” Cayne said. “I

…

expressed their disappointment with Sites's decision. In truth, Sites left because Cayne had picked Spector to be sole head of the firm's powerful fixed-income division. “Warren is a very brilliant guy but very nervous,” said one of his former partners. “Bites his nails down to the quick.” In

…

make this into some kind of power struggle between Warren and John is totally ridiculous.” There were other departures, too: Both Matthew Mancuso, who headed fixed-income sales, and R. Blaine Roberts, who was co-head of the structured transactions group, left in 1995. THEN, IN SEPTEMBER 1995, another member of

…

equity franchise,” explained Guy Moszkowski, then a research analyst at Salomon Smith Barney, covering the financial services industry. “They were still driven very much by fixed income.” In the days after UBS announced its deal for PaineWebber, as part of his job covering the financial services industry, Moszkowski went to see Cayne

…

predicted, after the bursting of the Internet and emerging telecom bubbles in 2000 and 2001, the businesses that were important again on Wall Street were fixed-income sales and trading and clearing—Bear's two stalwarts—rather than investment banking. While the firm's revenue from its capital markets businesses stayed flat

…

divisions— investment banking, clearing, asset management, and institutional equities—was down meaningfully from the third quarter of the year before, with one exception: fixed income. Net revenues for fixed income were $416.1 million, up 78.4 percent from $233.3 million in the previous year's third quarter. “Although down from last quarter

…

's record results, fixed income revenues remained strong year-over-year, with solid performances in the mortgage-backed securities, high yield and credit derivatives areas,” the firm announced. In short

…

order, Bear Stearns's fixed-income division accounted for one-third of the firm's revenues in the first nine months of 2001, up from 18 percent in the first nine

…

presumably of Dimon,” Muolo wrote. “Bear Stearns could also make an especially good fit with a commercial bank because it is well-known for its fixed-income business, and its highly lucrative clearing business.” (In the end, Dimon sold Bank One to JPMorgan Chase in 2004 for $58 billion in stock;

…

future water, phone, and power outages. THAT SAME MONTH, shortly after announcing quarterly net income of $181 million—powered yet again by the firm's fixed-income businesses, “with [a] particularly strong performance from our industry-leading mortgage-backed securities department,” Cayne emphasized in an SEC filing—Cayne decided to start writing

…

the spate of positive coverage of the firm was the question of why Cayne had not diversified the firm away from its huge concentration in fixed income and clearing. True, that decision had proved lucrative to Bear Stearns in the wake of September 11 and Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan's aggressive

…

classes. Give me yield, give me leverage, give me return.” Bear Stearns put itself at the epicenter of those consequences because of its reliance on fixed income—specifically mortgage-backed and other asset-backed securities—for its profitability and because of its failure to diversify when it had numerous chances. The blame

…

that we want to bring in here.” The intense and solidly built Cioffi, then forty-seven, had joined Bear Stearns in 1985 as an institutional fixed-income salesman, specializing in structured finance products, after stints at Merrill Lynch, Dean Witter Reynolds, and Institutional Direct. He grew up in South Burlington, Vermont,

…

near Lake Champlain. From 1989 to 1991, Cioffi was the New York head of fixed-income sales and then, for the next three years, served as global product and sales manager for high-grade credit products. “He was involved in the

…

covered that account got really rich.” Cioffi was making around $4 million, year after year, as a salesman. “He was the top fixed-income salesman in a firm where fixed income was king,” said one senior managing director. Then Cioffi got promoted to the job of institutional sales manager. He was a disaster. “He

…

had a guy, Rich Marin, running an asset management division that was the traditional asset management business—long only, primarily equities with a trace of fixed income—who suddenly inherits this high-octane mortgage guy and doesn't have any idea what to make of him,” Friedman explained. “Every time Marin and

…

on the expertise of Warren Spector, who himself was becoming more imperious and distant. Spector was the architect of the strategy to bulk up the fixed-income division—not that he did anything without the approval of the executive committee—and he was also the person who had enabled Ralph Cioffi to

…

build a hedge fund devoted to the exotic securities the fixed-income division was manufacturing. Cayne, the former broker, had only a vague understanding of all these exotic financial instruments that Spector's salesmen and traders

…

depth and its “reputation as a sharp-elbowed mercenary trading house that associates with dubious characters,” there was also the acknowledgment that the firm's fixed-income engine was firing on all cylinders, with revenue tripling in the past three years. The most interesting revelation in the article was not about Bear

…

line of competitive and flexible affordable mortgage products. This transaction enables us to continue to aggressively serve those markets.” Her colleague Owen Williams, on the fixed-income side of the bank, hailed the seemingly limitless investor demand for the securities. “We are extremely pleased by how well this transaction was received by

…

highly regarded salesman but short on managerial skills. In a pattern that Friedman had witnessed firsthand from Cioffi's time as a manager in the fixed-income department, in 2006 Cioffi's awkwardly named High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund started getting very sloppy in its paperwork regarding trades (securities bought and

…

think it will, the mortgage business won't be a contributor to their earnings. It will cause some deterioration in their results.” But Spector—the “fixed-income guru,” Paulden called him—remained confident. “We are not afraid of a bear market,” he said. “We've gained market share in these cycles.”

…

performance announcement caused the firm's stock to rally to near $149 per share. “Even though Bear's bread-and-butter has historically been in fixed income, given the slowdown in the residential mortgage market—meaning lower demand for mortgage-backed securities—we were impressed that Bear's credit derivative and distressed

…

same quarter a year earlier, “in part because of the implosion in the market for subprime mortgages.” The results showed definitively that the firm's fixed-income engine had slowed considerably, with revenue of $962 million, down 21 percent from the same period a year earlier. On the conference call about the

…

experienced trader and Grateful Dead lover, moved over to help manage the unwinding of the High-Grade Fund. That left a big hole in the fixed-income department but was thought to be necessary under the circumstances. Marano was going to work with Paul Friedman, whom Spector had already asked to go

…

figure out what to do. There was a considerable cast of characters, from Marin and Cioffi of BSAM to the leaders of the firm's fixed-income business—Craig Overlander, Jeff Mayer, Tommy Marano, and Paul Friedman. “The group dynamics were fascinating,” Friedman said. “By this time, Jimmy had allowed Warren

…

also on their confidence. “The stock drops like a stone,” Upton said. “CDS [credit default swap] spreads start blowing out again. Everyone's concerned. Our fixed-income investors and repo counterparties and banks are calling in. Molinaro comes racing down to my office at like ten-thirty and says, ‘We've got

…

what had caused the rapid decrease in liquidity in the debt markets in June and July. “There's a great deal of uncertainty in the fixed income markets over the level of default and loss expectations in the subprime mortgage market and … generally in the broader mortgage market,” Molinaro answered. In

…

the firm, that Molinaro would add the title of chief operating officer to that of chief financial officer, and that Jeffrey Mayer, co-head of fixed income, would replace Spector on the executive committee. Schwartz tried to convince Spector to stay on in some capacity, as a consultant of sorts to the

…

of $1.4 billion had already surpassed the 2006 annual total. Understandably, he spoke about Bear's bright spots, not its problem areas, such as fixed income (the home of its increasingly toxic assets) and asset management (the home of its problem hedge funds). In his presentation, Molinaro focused on the progress

…

cause. But he would have helped his own cause, probably, if he would have come right back.” Then there were the bankers and traders in fixed income who remained quite unhappy that Cayne had fired Spector unceremoniously and then brought embarrassing media attention to the firm. “Around us, firms are getting rid

…

very not all there. He wanted to hear that he needed to stay on.” Before the Christmas break, Schwartz called together the senior executives of fixed income, equities, and banking and, according to one of the participants, gave them a pep talk. He did not want all the bankers and traders going

…

all seemed like that made sense. Even through February.” With Spector long gone, both Cayne and Schwartz—neither of whom really knew very much about fixed income or exotic securities or how to make them or sell them—started spending more and more time on the seventh floor of 383 Madison trying

…

at the Credit Suisse conference, Upton was in Europe reassuring Bear's creditors. “Let's be honest,” he said. “There was creditor angst. There was fixed-income investor and creditor concern about Bear Stearns. It was particularly bad in overseas markets, arising first from the hedge funds, second from the belief—right

…

real estate books to see if they felt comfortable putting together financing to facilitate Barclays's acquisition of the rest of Lehman, including its global fixed-income, equities, investment banking, and asset management businesses, which totaled some $600 billion of assets. Fuld and Lowitt had announced on Wednesday that the commercial

…

745 Seventh Avenue and two data centers in New Jersey that Barclays wanted to buy. Barclays wanted all of Lehman's U.S. investment banking, fixed income, equity sales and trading, research, and certain support functions. Barclays did not want the investment management division or any of the commercial real estate assets

Principles of Corporate Finance

by Richard A. Brealey, Stewart C. Myers and Franklin Allen · 15 Feb 2014

in such cases were called consols. Consols are perpetuities. These are bonds that the government is under no obligation to repay but that offer a fixed income for each year to perpetuity. The British government is still paying interest on consols issued all those years ago. The annual rate of return on

…

debt maturing in a year or less. These short-term securities are known as Treasury bills. Treasury bonds, notes, and bills are traded in the fixed-income market. Let’s look at an example of a U.S. government bond. In 1985 the Treasury issued 11.25% notes maturing in 2015. These

…

promising to pay higher rates of interest. ● ● ● ● ● FURTHER READING Two good general texts on fixed income markets are: F. J. Fabozzi and S. V. Mann, Handbook of Fixed Income Markets, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011). S. Sundaresan, Fixed Income Markets and Their Derivatives, 3rd ed. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2009). Schaefer’s paper

…

nature of the inefficiency. Trading Opportunities—Are They Really There for Nonfinancial Corporations? Suppose that the treasurer’s staff in your firm notices mispricing in fixed-income or commodities markets, the kind of mispricing that a hedge fund would attempt to exploit in a convergence trade. Should the treasurer authorize the staff

…

. Its competition included the trading desks of all the major investment banks, hedge funds, and fixed-income portfolio managers. P&G had no special insights or competitive advantages on the fixed-income playing field. There was no evident reason to expect positive NPV on the trades it committed to. Why was it trading at

…

paper but are sold in a similar way. ● ● ● ● ● FURTHER READING A useful general work on debt securities is: F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011). For nontechnical discussions of the pricing of convertible bonds and the reasons for their use, see: M

…

pension plans) and wealthy individuals. In mid-2014 RA had about £1.1 billion under management, invested in a wide range of common-stock and fixed-income portfolios. Its management fees average 55 basis points (.55%), so RA’s total revenue for 2014 will be about .0055 × £1.1 billion = £6.05

…

as time passes and interest rates change. Also explain why SPX’s proposal is not advisable for a conservative company like Tintagel. RA manages several fixed-income portfolios. For simplicity, you decide to propose a mix of the following three portfolios: • A portfolio of long-term government bonds with an average duration

…

compensating balances and toward direct fees. 30-5 Marketable Securities In September 2011 Apple was sitting on an $81.6 billion mountain of cash and fixed income investments, amounting to 70% of the company’s total assets. Of this sum, $2.9 billion was kept as cash and the remainder was invested

…

Finance 19 (Summer 2007), pp. 74–81. For descriptions of the money-market and short-term lending opportunities, see: F. J. Fabozzi, The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012). F. J. Fabozzi, S. V. Mann, and M. Choudhry, The Global Money Markets (New York: John Wiley

…

-stage financing, 372 Fisher, A. C., 277n Fisher, F., 509n Fisher, Irving, 62–63, 699n Fitch credit ratings, 65–66, 595, 628n Fitzpatrick, Dan, 4n Fixed-income market, 47 Fixed-rate debt, 357 Flat (clean) price, 48n FleetBoston, 812 Fleet Financial Group, 812 Floating charge, 626 Floating-price convertibles, 622 Floating-rate

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies

by Tim Koller, McKinsey, Company Inc., Marc Goedhart, David Wessels, Barbara Schwimmer and Franziska Manoury · 16 Aug 2015 · 892pp · 91,000 words

, which don’t need basis in solid facts.”1 Bill Gross, cofounder and former chief investment officer of PIMCO, one of the world’s largest fixed-income investment managers, claims that the last 100 years of U.S. stock returns “belied a commonsensical flaw much like that of a chain letter or

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom

by Tony Robbins · 18 Nov 2014 · 825pp · 228,141 words

promise—to return my money with a specific rate of interest after X period of time (the maturity date). That’s why bonds are called “fixed-income investments.” The income—or return—you’ll get from them is fixed at the time you buy them, depending on the length of time you

…

. And later I’ll be showing you an amazing portfolio that uses bond funds in a totally unique way. But meanwhile, let’s consider another fixed-income investment that might belong in your Security Bucket. 3. CDs. Remember them? With certificates of deposit, you’re the one loaning the money to the

…

recent long periods of time—ten, twenty, fifty, one hundred years—you see that the equity returns are superior to those that you get in fixed income.” Historical data certainly back him up. Have a look at the visual below that traces the returns of stocks and bonds for periods of 100

…

Pension (with a Few Catches),” writer Anne Tergesen highlights the benefits of putting away $100,000 today (for a male age 65) into a deferred fixed-income annuity. This man has other savings and investments, which he thinks will last him to age 85 and get him down the mountain safely. But

…

$100,000 for an immediate fixed annuity can get about $7,600 a year for life . . . But with a longevity policy [a long-term deferred fixed-income annuity—I know the language is long] that starts issuing payments at age 85, his annual payout will be $63,990, New York Life says

…

returns. I have a straw-man portfolio in my book, and 70% of the assets in there are equities [or equity-like], and 30% are fixed income. TR: Let’s start with the equity side of the portfolio: the 70%. One of your rules for diversification is to never have anything weighted

…

then I probably put 10% in emerging markets, 15% in foreign development, and 15% in real estate investment trusts. TR: Tell me about the 30% fixed-income securities. DS: I’ve got all of them in Treasury securities. Half of them are traditional bonds. The other half are in inflation-protected TIPS

…

concept of, 90 critical mass of, 33 decumulation phase, 89, 90 earnings and, 259–72 environment for, 385–88 and fees, 87, 105–15, 534 fixed-income (bonds), 304 goal of, 98 long-term, 93, 104, 329–30, 351, 474, 504 lump-sum, 365–66 mistakes in, 297 offer, 84 passive (indexing

DIY Investor: How to Take Control of Your Investments & Plan for a Financially Secure Future

by Andy Bell · 12 Sep 2013 · 348pp · 82,499 words

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

Investment Banking: Valuation, Leveraged Buyouts, and Mergers and Acquisitions

by Joshua Rosenbaum, Joshua Pearl and Joseph R. Perella · 18 May 2009 · 444pp · 86,565 words

The New Science of Asset Allocation: Risk Management in a Multi-Asset World

by Thomas Schneeweis, Garry B. Crowder and Hossein Kazemi · 8 Mar 2010 · 317pp · 106,130 words

A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation

by Richard Bookstaber · 5 Apr 2007 · 289pp · 113,211 words

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy J. Siegel · 18 Dec 2007

Financial Independence

by John J. Vento · 31 Mar 2013 · 368pp · 145,841 words

The Investopedia Guide to Wall Speak: The Terms You Need to Know to Talk Like Cramer, Think Like Soros, and Buy Like Buffett

by Jack (edited By) Guinan · 27 Jul 2009 · 353pp · 88,376 words

Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined

by Lasse Heje Pedersen · 12 Apr 2015 · 504pp · 139,137 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

Expected Returns: An Investor's Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards

by Antti Ilmanen · 4 Apr 2011 · 1,088pp · 228,743 words

The Invisible Hands: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Bubbles, Crashes, and Real Money

by Steven Drobny · 18 Mar 2010 · 537pp · 144,318 words

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy Siegel · 7 Jan 2014 · 517pp · 139,477 words

Financial Statement Analysis: A Practitioner's Guide

by Martin S. Fridson and Fernando Alvarez · 31 May 2011

Debtor Nation: The History of America in Red Ink (Politics and Society in Modern America)

by Louis Hyman · 3 Jan 2011

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by Grace Blakeley · 9 Sep 2019 · 263pp · 80,594 words

My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance

by Emanuel Derman · 1 Jan 2004 · 313pp · 101,403 words

Capital Ideas Evolving

by Peter L. Bernstein · 3 May 2007

Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners

by Larry Harris · 2 Jan 2003 · 1,164pp · 309,327 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by William D. Cohan · 25 Dec 2015 · 1,009pp · 329,520 words

Digital Accounting: The Effects of the Internet and Erp on Accounting

by Ashutosh Deshmukh · 13 Dec 2005

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by Adam Tooze · 31 Jul 2018 · 1,066pp · 273,703 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

The Bank That Lived a Little: Barclays in the Age of the Very Free Market

by Philip Augar · 4 Jul 2018 · 457pp · 143,967 words

Planet Ponzi

by Mitch Feierstein · 2 Feb 2012 · 393pp · 115,263 words

After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead

by Alan S. Blinder · 24 Jan 2013 · 566pp · 155,428 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

by Matthew Desmond · 1 Mar 2016 · 444pp · 138,781 words

The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a Lifetime

by Mj Demarco · 8 Nov 2010 · 386pp · 116,233 words

Investing Amid Low Expected Returns: Making the Most When Markets Offer the Least

by Antti Ilmanen · 24 Feb 2022

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Frequently Asked Questions in Quantitative Finance

by Paul Wilmott · 3 Jan 2007 · 345pp · 86,394 words

How to Retire the Cheapskate Way

by Jeff Yeager · 1 Jan 2013 · 212pp · 70,224 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

The Trade Lifecycle: Behind the Scenes of the Trading Process (The Wiley Finance Series)

by Robert P. Baker · 4 Oct 2015

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival

by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan · 8 Aug 2020 · 438pp · 84,256 words

Shortchanged: Life and Debt in the Fringe Economy

by Howard Karger · 9 Sep 2005 · 299pp · 83,854 words

The Euro and the Battle of Ideas

by Markus K. Brunnermeier, Harold James and Jean-Pierre Landau · 3 Aug 2016 · 586pp · 160,321 words

Financial Freedom: A Proven Path to All the Money You Will Ever Need

by Grant Sabatier · 5 Feb 2019 · 621pp · 123,678 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by Ann Pettifor · 27 Mar 2017 · 182pp · 53,802 words

Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Achieving Financial Independence: Revised and Updated for the 21st Century

by Vicki Robin, Joe Dominguez and Monique Tilford · 31 Aug 1992 · 426pp · 115,150 words

Understanding Asset Allocation: An Intuitive Approach to Maximizing Your Portfolio

by Victor A. Canto · 2 Jan 2005 · 337pp · 89,075 words

The Lost Bank: The Story of Washington Mutual-The Biggest Bank Failure in American History

by Kirsten Grind · 11 Jun 2012 · 549pp · 147,112 words

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

Be Your Own Financial Adviser: The Comprehensive Guide to Wealth and Financial Planning

by Jonquil Lowe · 14 Jul 2010 · 433pp · 53,078 words

The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America

by Warren E. Buffett and Lawrence A. Cunningham · 2 Jan 1997 · 219pp · 15,438 words

Getting a Job in Hedge Funds: An Inside Look at How Funds Hire

by Adam Zoia and Aaron Finkel · 8 Feb 2008 · 192pp · 75,440 words

Meltdown: How Greed and Corruption Shattered Our Financial System and How We Can Recover

by Katrina Vanden Heuvel and William Greider · 9 Jan 2009 · 278pp · 82,069 words

All About Asset Allocation, Second Edition

by Richard Ferri · 11 Jul 2010

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Blyth · 24 Apr 2013 · 576pp · 105,655 words

Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment

by David F. Swensen · 8 Aug 2005 · 490pp · 117,629 words

Debunking Economics - Revised, Expanded and Integrated Edition: The Naked Emperor Dethroned?

by Steve Keen · 21 Sep 2011 · 823pp · 220,581 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

The Power of Passive Investing: More Wealth With Less Work

by Richard A. Ferri · 4 Nov 2010 · 345pp · 87,745 words

Hedge Fund Market Wizards

by Jack D. Schwager · 24 Apr 2012 · 272pp · 19,172 words

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by Matthew C. Klein · 18 May 2020 · 339pp · 95,270 words

The Global Money Markets

by Frank J. Fabozzi, Steven V. Mann and Moorad Choudhry · 14 Jul 2002

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

The Bond King: How One Man Made a Market, Built an Empire, and Lost It All

by Mary Childs · 15 Mar 2022 · 367pp · 110,161 words

China's Great Wall of Debt: Shadow Banks, Ghost Cities, Massive Loans, and the End of the Chinese Miracle

by Dinny McMahon · 13 Mar 2018 · 290pp · 84,375 words

Who Owns England?: How We Lost Our Green and Pleasant Land, and How to Take It Back

by Guy Shrubsole · 1 May 2019 · 505pp · 133,661 words

The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions

by Victor Haghani and James White · 27 Aug 2023 · 314pp · 122,534 words

The Handbook of Personal Wealth Management

by Reuvid, Jonathan. · 30 Oct 2011

Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History

by Milton Friedman · 1 Jan 1992 · 275pp · 82,640 words

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by Kevin Mellyn · 30 Sep 2009 · 225pp · 11,355 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by Nouriel Roubini · 17 Oct 2022 · 328pp · 96,678 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future

by Chris Guillebeau · 7 May 2012 · 248pp · 72,174 words

Fed Up!: Success, Excess and Crisis Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Macro Trader

by Colin Lancaster · 3 May 2021 · 245pp · 75,397 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton · 3 Feb 2002 · 353pp · 148,895 words

Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World

by William D. Cohan · 11 Apr 2011 · 1,073pp · 302,361 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

State of Emergency: The Way We Were

by Dominic Sandbrook · 29 Sep 2010 · 932pp · 307,785 words

Street Fighters: The Last 72 Hours of Bear Stearns, the Toughest Firm on Wall Street

by Kate Kelly · 14 Apr 2009 · 258pp · 71,880 words

All the Devils Are Here

by Bethany McLean · 19 Oct 2010 · 543pp · 157,991 words

Portfolio Design: A Modern Approach to Asset Allocation

by R. Marston · 29 Mar 2011 · 363pp · 28,546 words

High-Frequency Trading

by David Easley, Marcos López de Prado and Maureen O'Hara · 28 Sep 2013

Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JPMorgan Chase

by Duff McDonald · 5 Oct 2009 · 419pp · 130,627 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing (Eleventh Edition)

by Burton G. Malkiel · 5 Jan 2015 · 482pp · 121,672 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

Too big to fail: the inside story of how Wall Street and Washington fought to save the financial system from crisis--and themselves

by Andrew Ross Sorkin · 15 Oct 2009 · 351pp · 102,379 words

Toward Rational Exuberance: The Evolution of the Modern Stock Market

by B. Mark Smith · 1 Jan 2001 · 403pp · 119,206 words

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by Robert Higgs and Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. · 15 Jan 1987

Smart Money: How High-Stakes Financial Innovation Is Reshaping Our WorldÑFor the Better

by Andrew Palmer · 13 Apr 2015 · 280pp · 79,029 words

Learn Algorithmic Trading

by Sebastien Donadio · 7 Nov 2019

High-Frequency Trading: A Practical Guide to Algorithmic Strategies and Trading Systems

by Irene Aldridge · 1 Dec 2009 · 354pp · 26,550 words

Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

by Bruce C. N. Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul D. Sonkin and Michael van Biema · 26 Jan 2004 · 306pp · 97,211 words

file:///C:/Documents%20and%...

by vpavan

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

A Colossal Failure of Common Sense: The Inside Story of the Collapse of Lehman Brothers

by Lawrence G. Mcdonald and Patrick Robinson · 21 Jul 2009 · 430pp · 140,405 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by Richard R. Lindsey and Barry Schachter · 30 Jun 2007

The Gone Fishin' Portfolio: Get Wise, Get Wealthy...and Get on With Your Life

by Alexander Green · 15 Sep 2008 · 244pp · 58,247 words

Mastering Private Equity

by Zeisberger, Claudia,Prahl, Michael,White, Bowen, Michael Prahl and Bowen White · 15 Jun 2017

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

King of Capital: The Remarkable Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Steve Schwarzman and Blackstone

by David Carey · 7 Feb 2012 · 421pp · 128,094 words

Trading Risk: Enhanced Profitability Through Risk Control

by Kenneth L. Grant · 1 Sep 2004

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition

by Charles Eisenstein · 11 Jul 2011 · 448pp · 142,946 words

Your Money: The Missing Manual

by J.D. Roth · 18 Mar 2010 · 519pp · 118,095 words

Commodity Trading Advisors: Risk, Performance Analysis, and Selection

by Greg N. Gregoriou, Vassilios Karavas, François-Serge Lhabitant and Fabrice Douglas Rouah · 23 Sep 2004

Crash of the Titans: Greed, Hubris, the Fall of Merrill Lynch, and the Near-Collapse of Bank of America

by Greg Farrell · 2 Nov 2010 · 526pp · 158,913 words

Inside the House of Money: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Profiting in a Global Market

by Steven Drobny · 31 Mar 2006 · 385pp · 128,358 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

Electronic and Algorithmic Trading Technology: The Complete Guide

by Kendall Kim · 31 May 2007 · 224pp · 13,238 words

Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism

by Wolfgang Streeck · 1 Jan 2013 · 353pp · 81,436 words

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Apr 2008 · 304pp · 22,886 words

On the Brink: Inside the Race to Stop the Collapse of the Global Financial System

by Henry M. Paulson · 15 Sep 2010 · 468pp · 145,998 words

How Will Capitalism End?

by Wolfgang Streeck · 8 Nov 2016 · 424pp · 115,035 words

Framing Class: Media Representations of Wealth and Poverty in America

by Diana Elizabeth Kendall · 27 Jul 2005 · 311pp · 130,761 words

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by Kwasi Kwarteng · 12 May 2014 · 632pp · 159,454 words

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by John Kay · 2 Sep 2015 · 478pp · 126,416 words

Greed and Glory on Wall Street: The Fall of the House of Lehman

by Ken Auletta · 28 Sep 2015 · 349pp · 104,796 words

Money: The Unauthorized Biography

by Felix Martin · 5 Jun 2013 · 357pp · 110,017 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing

by Burton G. Malkiel · 10 Jan 2011 · 416pp · 118,592 words

The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio

by William J. Bernstein · 26 Apr 2002 · 407pp · 114,478 words

Paper Money Collapse: The Folly of Elastic Money and the Coming Monetary Breakdown

by Detlev S. Schlichter · 21 Sep 2011 · 310pp · 90,817 words

Smarter Investing

by Tim Hale · 2 Sep 2014 · 332pp · 81,289 words

Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves From the American Dream

by Alissa Quart · 14 Mar 2023 · 304pp · 86,028 words

925 Ideas to Help You Save Money, Get Out of Debt and Retire a Millionaire So You Can Leave Your Mark on the World

by Devin D. Thorpe · 25 Nov 2012 · 263pp · 89,368 words

The Permanent Portfolio

by Craig Rowland and J. M. Lawson · 27 Aug 2012

The Complete Novels Of George Orwell

by George Orwell · 3 Jun 2009 · 1,497pp · 492,782 words

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

Risk Management in Trading

by Davis Edwards · 10 Jul 2014

Retirementology: Rethinking the American Dream in a New Economy

by Gregory Brandon Salsbury · 15 Mar 2010 · 261pp · 70,584 words

Personal Investing: The Missing Manual

by Bonnie Biafore, Amy E. Buttell and Carol Fabbri · 24 May 2010 · 250pp · 77,544 words

Freedom Without Borders

by Hoyt L. Barber · 23 Feb 2012 · 192pp · 72,822 words

The Crisis of Crowding: Quant Copycats, Ugly Models, and the New Crash Normal

by Ludwig B. Chincarini · 29 Jul 2012 · 701pp · 199,010 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer-And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class

by Paul Pierson and Jacob S. Hacker · 14 Sep 2010 · 602pp · 120,848 words

The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking

by Saifedean Ammous · 23 Mar 2018 · 571pp · 106,255 words

The Physics of Wall Street: A Brief History of Predicting the Unpredictable

by James Owen Weatherall · 2 Jan 2013 · 338pp · 106,936 words

The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan

by Sebastian Mallaby · 10 Oct 2016 · 1,242pp · 317,903 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

How to Predict the Unpredictable

by William Poundstone · 267pp · 71,941 words

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1990 · 1,335pp · 336,772 words

The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives

by Sasha Abramsky · 15 Mar 2013 · 406pp · 113,841 words

Barometer of Fear: An Insider's Account of Rogue Trading and the Greatest Banking Scandal in History

by Alexis Stenfors · 14 May 2017 · 312pp · 93,836 words

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by James Rickards · 15 Nov 2016 · 354pp · 105,322 words

Fool's Gold: How the Bold Dream of a Small Tribe at J.P. Morgan Was Corrupted by Wall Street Greed and Unleashed a Catastrophe

by Gillian Tett · 11 May 2009 · 311pp · 99,699 words

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Hedgehogging

by Barton Biggs · 3 Jan 2005

Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America

by Conor Dougherty · 18 Feb 2020 · 331pp · 95,582 words

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by Satyajit Das · 15 Nov 2006 · 349pp · 134,041 words

The Soul of Wealth

by Daniel Crosby · 19 Sep 2024 · 229pp · 73,085 words

Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

by Parag Khanna · 18 Apr 2016 · 497pp · 144,283 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by William Baker and Addison Wiggin · 2 Nov 2009 · 444pp · 151,136 words

Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change

by Dieter Helm · 2 Sep 2020 · 304pp · 90,084 words

Crisis and Dollarization in Ecuador: Stability, Growth, and Social Equity

by Paul Ely Beckerman and Andrés Solimano · 30 Apr 2002

What They Do With Your Money: How the Financial System Fails Us, and How to Fix It

by Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik and David Pitt-Watson · 30 Apr 2016 · 304pp · 80,965 words

Optimization Methods in Finance

by Gerard Cornuejols and Reha Tutuncu · 2 Jan 2006 · 130pp · 11,880 words

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by James Rickards · 7 Apr 2014 · 466pp · 127,728 words

Rigged Money: Beating Wall Street at Its Own Game

by Lee Munson · 6 Dec 2011 · 236pp · 77,735 words

Everybody's Guide to Small Claims Court

by Ralph E. Warner · 2 Jan 1978

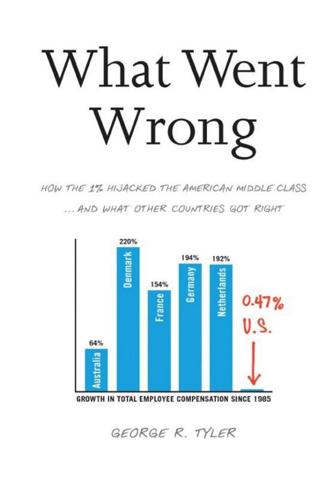

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Keeping at It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government

by Paul Volcker and Christine Harper · 30 Oct 2018 · 363pp · 98,024 words

Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet

by Varun Sivaram · 2 Mar 2018 · 469pp · 132,438 words

Work Less, Live More: The Way to Semi-Retirement

by Robert Clyatt · 28 Sep 2007

Market Sense and Nonsense

by Jack D. Schwager · 5 Oct 2012 · 297pp · 91,141 words

Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings

by Philip A. Fisher · 13 Apr 2015

Losing Control: The Emerging Threats to Western Prosperity

by Stephen D. King · 14 Jun 2010 · 561pp · 87,892 words

When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor

by William Julius Wilson · 1 Jan 1996 · 399pp · 116,828 words

A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Carbon Emissions

by Muhammad Yunus · 25 Sep 2017 · 278pp · 74,880 words

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns

by John C. Bogle · 1 Jan 2007 · 356pp · 51,419 words

Red Flags: Why Xi's China Is in Jeopardy

by George Magnus · 10 Sep 2018 · 371pp · 98,534 words

Practical Doomsday: A User's Guide to the End of the World

by Michal Zalewski · 11 Jan 2022 · 337pp · 96,666 words

Beyond Diversification: What Every Investor Needs to Know About Asset Allocation

by Sebastien Page · 4 Nov 2020 · 367pp · 97,136 words

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber · 1 Jan 2010 · 725pp · 221,514 words

There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America

by Brian Goldstone · 25 Mar 2025 · 512pp · 153,059 words

The Tyranny of Nostalgia: Half a Century of British Economic Decline

by Russell Jones · 15 Jan 2023 · 463pp · 140,499 words

Rough Sleepers: Dr. Jim O'Connell's Urgent Mission to Bring Healing to Homeless People

by Tracy Kidder · 17 Jan 2023 · 270pp · 88,213 words

The Clash of the Cultures

by John C. Bogle · 30 Jun 2012 · 339pp · 109,331 words

Quit Like a Millionaire: No Gimmicks, Luck, or Trust Fund Required

by Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung · 8 Jul 2019 · 389pp · 81,596 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

The Quants

by Scott Patterson · 2 Feb 2010 · 374pp · 114,600 words

The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich

by Timothy Ferriss · 1 Jan 2007 · 426pp · 105,423 words

Cryptoassets: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond

by Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar · 19 Oct 2017 · 416pp · 106,532 words

The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

by David Callahan · 1 Jan 2004 · 452pp · 110,488 words

The Predators' Ball: The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham and the Rise of the JunkBond Raiders

by Connie Bruck · 1 Jun 1989 · 507pp · 145,878 words

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

The Price of Silence: The Duke Lacrosse Scandal

by William D. Cohan · 8 Apr 2014 · 1,061pp · 341,217 words

The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers (Wiley Finance)

by Feng Gu · 26 Jun 2016

The Dollar Meltdown: Surviving the Coming Currency Crisis With Gold, Oil, and Other Unconventional Investments

by Charles Goyette · 29 Oct 2009 · 287pp · 81,970 words

The End of Wall Street

by Roger Lowenstein · 15 Jan 2010 · 460pp · 122,556 words

Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side

by Howard Marks · 30 Sep 2018 · 302pp · 84,428 words

Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy

by Chris Hayes · 11 Jun 2012 · 285pp · 86,174 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

Bank 3.0: Why Banking Is No Longer Somewhere You Go but Something You Do

by Brett King · 26 Dec 2012 · 382pp · 120,064 words

Alpha Trader

by Brent Donnelly · 11 May 2021

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by Jan Lucassen · 26 Jul 2021 · 869pp · 239,167 words

Warren Buffett Accounting Book: Reading Financial Statements for Value Investing (Warren Buffett's 3 Favorite Books)

by Stig Brodersen and Preston Pysh · 30 Apr 2014 · 261pp · 63,473 words

Trading at the Speed of Light: How Ultrafast Algorithms Are Transforming Financial Markets

by Donald MacKenzie · 24 May 2021 · 400pp · 121,988 words

Young Money: Inside the Hidden World of Wall Street's Post-Crash Recruits

by Kevin Roose · 18 Feb 2014 · 269pp · 83,307 words

Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World

by J. Doyne Farmer · 24 Apr 2024 · 406pp · 114,438 words

Sunbelt Blues: The Failure of American Housing

by Andrew Ross · 25 Oct 2021 · 301pp · 90,276 words

Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk

by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz · 8 Jul 2024 · 259pp · 89,637 words

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber · 29 Oct 2024 · 292pp · 106,826 words

Trillions: How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever

by Robin Wigglesworth · 11 Oct 2021 · 432pp · 106,612 words

The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization Are Destroying the Idea of America

by Victor Davis Hanson · 15 Nov 2021 · 458pp · 132,912 words

More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite

by Sebastian Mallaby · 9 Jun 2010 · 584pp · 187,436 words

The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything

by Jason Kelly · 10 Sep 2012 · 274pp · 81,008 words

The Best Business Writing 2013

by Dean Starkman · 1 Jan 2013 · 514pp · 152,903 words

The Downfall of Money: Germany's Hyperinflation and the Destruction of the Middle Class

by Frederick Taylor · 16 Sep 2013 · 473pp · 132,344 words

The Intelligent Asset Allocator: How to Build Your Portfolio to Maximize Returns and Minimize Risk

by William J. Bernstein · 12 Oct 2000

The Trouble With Billionaires

by Linda McQuaig · 1 May 2013 · 261pp · 81,802 words

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality From the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century

by Walter Scheidel · 17 Jan 2017 · 775pp · 208,604 words

Stock Market Wizards: Interviews With America's Top Stock Traders

by Jack D. Schwager · 1 Jan 2001

The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalization

by Michael O’sullivan · 28 May 2019 · 756pp · 120,818 words

The Only Game in Town: Central Banks, Instability, and Avoiding the Next Collapse

by Mohamed A. El-Erian · 26 Jan 2016 · 318pp · 77,223 words

When Money Dies

by Adam Fergusson · 25 Aug 2011

Poverty for Profit

by Anne Kim · 384pp · 112,825 words

How Money Became Dangerous

by Christopher Varelas · 15 Oct 2019 · 477pp · 144,329 words

American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History

by Casey Michel · 23 Nov 2021 · 466pp · 116,165 words

Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America's Edge

by Ted Conover · 1 Nov 2022 · 391pp · 106,255 words

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

by Jeff Gramm · 23 Feb 2016 · 384pp · 103,658 words