The Means of Prediction: How AI Really Works (And Who Benefits)

by Maximilian Kasy · 15 Jan 2025 · 209pp · 63,332 words

the first time, we are faced “with something that’s going to be far more intelligent than us.” Sam Altman, of OpenAI, has claimed that generative AI could bring about the end of human civilization, and that AI poses a risk of extinction on a par with nuclear warfare and global pandemics

…

us, but it will render human workers obsolete, inevitably leading to mass unemployment and social unrest. A 2023 Goldman Sachs report, for instance, claimed that generative AI might replace three hundred million full-time workers in Europe and the United States. The story told in Hollywood and in Silicon Valley tends to

…

abundant, such as image recognition or language modeling. Neural nets, and in particular transformers (a special kind of neural net), have also been central for generative AI—AI that produces text, images, or other media. This includes large language models, where the goal is to predict the most likely word to come

…

next. (Large language models power applications such as ChatGPT.) Generative AI also includes image generation, where images are predicted based on text labels, as well as video generation. Supervised learning is a form of offline learning

…

solving. In deep learning, as in AI more broadly, such a discussion needs to be the starting point for democratic governance. Self-Supervised Learning and Generative AI As noted earlier, a lot of problems in AI are prediction problems. Supervised learning solves these prediction problems. But there is an issue that we

…

language modeling have succeeded at doing convincingly, most notably in chatbots such as ChatGPT or Claude. Text generation is not the only success story of generative AI; the automatic generation of realistic images has also made great advances, notably in algorithms such as Stable Diffusion. Both text generation and image generation build

…

out to generate realistic, high-quality images. Just as was the case for transformers, the popularity of this approach is due to its practical success. Generative AI, whether for the generation of text or of images, raises important questions of data ownership. Both large language models and image generation models are trained

…

for the concentration of economic power in general, and for the allocation of control over AI more specifically. This is discussed later in the book. Generative AI also raises interesting questions about objective functions and control over AI. Throughout this book, I emphasize that AI maximizes or minimizes some objective function—such

…

as predictive loss (i.e., prediction errors) for the next word on the internet, in the case of large language models. For generative AI, we need to modify this statement slightly: The model minimizes predictive loss for the next word in response to a prompt that is chosen by

…

the user of the generative AI tool. Control over objectives is thus effectively split for generative AI. A central entity, such as OpenAI, controls the foundation model, such as the language model GPT-4. This foundation model

…

., OpenAI/Microsoft) and the user who chooses the prompt. Neural nets and deep learning have had surprising successes in many domains, one of which is generative AI. But deep learning remains within the framework of supervised learning—that is, of prediction. There is something very important that is missing in the prediction

…

platforms greatly contribute to the common good. They also serve as one of the prime sources of training data for large language models, and for generative AI more broadly. All the works of art and writing that are available on the internet but that are considered someone’s intellectual property under current

…

for the purpose of training AI. The business models of several industries that were built on intellectual property are being jeopardized by AI, especially by generative AI. This includes the news media, the music industry, movies, and television. The collapse of old business models in these industries started with the expansion of

…

for predictions of technological unemployment due to technological change. One example of this genre is a 2023 report by researchers at Goldman Sachs predicted that generative AI might replace three hundred million full-time workers in the industrialized West. So far, so familiar. But maybe this time is different, after all? Maybe

…

, and tools based on machine learning more generally, seem destined to have big impacts in the workplace. We can only speculate on the impact that generative AI and related technologies will have. The recent debate has emphasized a few possible directions. For one, the ideal of artificial intelligence as an imitation of

…

, novice workers and those considered less productive benefited most from these assistants, while experienced and productive workers did not benefit. A possible explanation is that generative AI sets a baseline quality of work. Those workers who would otherwise fall below this baseline stand to gain from the new tools, while those workers

…

of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press, 2021. Goldman Sachs. “Generative AI could raise global GDP by 7%.” April 5, 2023. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent. Kelly, S. “Sam Altman Warns AI Could Kill Us All: But

…

, no. 2 (2008): 300–323. Becker, G. S. The Economics of Discrimination. University of Chicago Press, 1957. Brynjolfsson, E., D. Li, and L. R. Raymond. “Generative AI at Work.” Working Paper No. 31161. National Bureau of Economic Research, revised November 2023. Dwork, C., and A. Roth. “The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy

…

, 45, 63–65; and early stopping, 42–43; energy consumption of, 93–95; factors in success of, 45, 49–50, 63–65, 89–90; and generative AI, 53–56; how it works, 45–50; reinforcement learning and, 63; relative simplicity of, 49; self-supervised, 52–53; technical meaning of, 47 deep reinforcement

…

, 19–20 functions, 46 gambling for resurrection, 126 Gaza, 6, 31–32, 133 Gebru, Timnit, 6 General Data Protection Regulation (European Union), 86, 141–42 generative AI: augmentative uses of, 157–58; intellectual property and, 108; labor market effects of, 149, 157–58; objectives of, 55–56; technological advances contributing to, 11

…

, 173–74, 186–88, 194; democratic governance of, 5, 7–8, 16, 34–35, 52, 107–8, 111–13, 135, 173–74, 186–88, 195; generative AI and, 55–56; incomplete/misdefined, 122; optimization of, 5; reward/loss defined by, 23–24; social power determining control of, 6; worker input to, 160

Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist

by Liz Pelly · 7 Jan 2025 · 293pp · 104,461 words

the relationship between AI and creative labor has taken hold, the whole streaming conversation now takes place under this looming cloud: how tracks created with generative AI software are flooding the streaming services and the effects this will have on working musicians and aspiring artists alike. And while the potential of

…

generative AI feels urgent, it’s also important to remember the less flashy ways that artists and listeners have been impacted by different systems of automation and

…

make him into the coolest music producer that you can find.” In retrospect, the bio sort of sounds like it could have been written using generative AI. It was just one example of what was all over Spotify at that point, in 2023: “A range of artists, in genres such as hip

…

-up problem of misinformation and media degradation, issues that were only going to grow more insidious as the functional music trend opened the door for generative AI music makers to walk right in. “When you are a DSP and you have that much power and influence over people’s education about music

…

disconnect listeners from the makers of the music they’re consuming, laying the groundwork for users to accept the hyper-normalization of music made using generative AI software. The reality of this power imbalance was ultimately why another musician, who made ambient tracks for a different, non-Epidemic PFC licensor, ended up

…

hit play, as well as “daylist,” a personalized playlist that changed throughout the day, and “AI DJ,” auto-recs spliced with intros made by a generative AI DJ voice. A former employee said this proliferation of new features caused friction between the very concepts of the playlist versus the personalization algorithms. “There

…

.” Introduced in the winter of 2023, the new DJ function immediately seemed like nothing more than an eager attempt at capitalizing on the then-ongoing generative AI hype cycle. But it was also something the company had been working on for many years, an elusive vision they’d long been after: one

…

if you can get fans to process the data for you? Aesthetics Wiki itself was eventually absorbed as a data source for a number of generative AI companies. The new paradigms of being a fan online—the niche vibes, the meme playlists, the infinite descriptors—started feeling more attuned to this broader

…

culture reshaped by algorithmic ubiquitousness, which is to say, by tools of surveillance.3 11 Sounds for Self-Optimization In 2023, Spotify temporarily prohibited a generative AI start-up called Boomy from releasing new music to the platform. The app has been around since 2018 and claims to have released over 14

…

out “stream manipulation” to “protect royalty payouts for honest, hardworking artists.” But the company made one thing clear: Boomy was not being penalized for releasing generative AI content. It had already been doing so for years: in fact, in its first year, tracks generated with Boomy software had seen so much success

…

matter—be impacted when streaming services were inevitably (always inevitably!) flooded with thousands and thousands of AI-generated tracks? Would “streambait” be supplanted by the generative AI content? Would all of those “fake artists” just be auto-generated one day? Daniel Ek, for one, was into it. On a 2023 conference call

…

content could be “great culturally” and allow Spotify to “grow engagement and revenue.” His company was also figuring out new ways to use the emerging generative AI narratives to ship new playlist products. Similarly to Boomy, Spotify used the language of creative empowerment to describe the beta version of “AI Playlist” in

…

for relatively uncontroversial purposes, basic audio functions like volume and signal correction. But some of it had more serious implications, including the various apps for generative AI music. It was challenging to make sense of it all; to separate the smoke and mirrors from the legitimate threats, the real from the fake

…

worried about a future that was seeming increasingly imminent: How would musicians know if their work had been used as training data to create a generative AI system? What intellectual property rights would apply? Who could control unauthorized sonic deepfakes? On the other hand, more optimistic artists and technologists urged that AI

…

legacy of blackface performance as the origin of all popular music, entertainment, and culture in the United States.” The music industry seemed set on using generative AI to author a new chapter in its long history of exploiting marginalized voices.6 Another AI music controversy consumed the music press in 2023, when

…

were clamoring to harness its potential: it opened up a possible new pool of cheap content.8 * * * When people were paying attention, the debate about generative AI was fierce. But what if it could be deployed in the corners of music where people weren’t paying attention? Indeed, this seemed to be

…

-further-develop-its-ai-powered-sound-wellness-technology/; Mandy Dalugdug, “Amazon Music Strikes Playlist Partnership with Generative AI Music Company Endel,” Music Business Worldwide, February 20, 2023, https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/amazon-music-strikes-playlist-partnership-with-generative-ai-music-company-endel12/. 13 Sheldon Pearce, “James Blake & Endel: ‘Wind Down,’ ” New Yorker, June 3

…

, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/goings-on-about-town/night-life/james-blake-and-endel-wind-down; “Generative AI Can Be a Co-Songwriter, Not a Copycat: Guest Post by Endel CEO Oleg Stavitsky,” Variety, March 29, 2023, https://variety.com/2023/music/opinion

…

/generative-ai-csongwriter-endel-oleg-stavitsky-artificial-intelligence-1235568233/. 14 Bob Wilson, “The Science behind Focus,” Endel, June 28, 2022, https://endel.io/blog/the-science-behind-

Gambling Man

by Lionel Barber · 3 Oct 2024 · 424pp · 123,730 words

the problem was timing. During the six years Masa raised and deployed money for SoftBank Vision Fund 1 and 2, the opportunities to invest in generative AI companies were few and far between. Aside from Open AI, these businesses were either small scale, early in development or out of the public eye

…

data firm Tempus and the UK self-driving car technology start-up Wayve. The emergence of ChatGPT, according to Masa, has changed everything. So-called generative AI points to a future he has long predicted: the moment when machines think faster, learn faster and react faster than humans. ‘It’s like the

…

of the biggest swings and misses in the history of investing. ‘If we had the same $100 billion right now, maybe we would focus on generative AI-related companies. Now these are true AI revolution companies. We were probably five years too early. But I think my instinct on the direction is

…

to view technology as a job-killer or a corrupting force, creating a world where disinformation is spread at scale and speed. The debate about generative AI threatens to move in an even darker direction. Tesla’s Elon Musk has warned of a ‘Terminator future’, where AI would remove the need for

…

Covid pandemic, 299; as disruptor of VC sector, 84, 260–61, 281–2, 283–5; Foxconn investment in US, 268, 269; and Gates, 267; and generative AI companies, 328; and geopolitical changes, 320–21; and Grannan’s Light, 285–6; and Greensill, 293–4, 319–20; investments in China, 321; Langham Huntington

Mattering: The Secret to Building a Life of Deep Connection and Purpose

by Jennifer Breheny Wallace · 13 Jan 2026 · 206pp · 68,830 words

less likely to have changed organizations two years later. Even the least humancentered corporation is well incentivized to address this crisis. The rapid adoption of generative AI is intensifying the sense of replaceability among workers. In a Wall Street Journal article titled “‘Everybody’s Replaceable’: The New Ways Bosses Talk About Workers

…

Sachs: Jan Hatzius et al., “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth,” Goldman Sachs Economic Research (March 2023), goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent. 165 Technology leaders like Bill Gates: Tom Huddleston Jr., “Bill Gates: Within 10 Years, AI Will Replace Many

…

friendship recession, fighting, 78–81 fuel, 179 Gallup on disengagement, 174–75 on employee sense of mattering, 180 Gates, Bill, 165–66 Gehl, Jan, 210 generative AI, 175 generativity, 196 Georgia-Pacific, 44 gestures acts of kindness as, 54–56 of recognition, 19–20, 131–32 Ginsburg, Marty, 82 Ginsburg, Ruth Bader

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

real. In early 2023, a thirty-one-year-old Chicago construction worker had made this piece of art while high on psychedelic mushrooms using the generative AI tool Midjourney. He first shared the image in the Facebook group AI Art Universe before posting it to Reddit, where he was quickly banned. By

…

evil Skynet in Terminator to the malevolent robots of The Matrix. But OpenAI, run by Sam Altman, went on a full-out marketing blitz for “generative AI” with the release of the image-generation software DALL-E in early 2021 and large language model ChatGPT in late 2022

…

. Generative AI empowered everyday users to produce stunningly humanlike creations from simple text prompts. As ChatGPT stole the cultural spotlight, the tech world pivoted en masse: Major

…

determined to steamroll over civilization rather than act in service of its users. Neoliberal economics had already shipped well-paying blue-collar work overseas; now generative AI threatened to replace workers in routine service roles. White-collar fields like law and medicine seemed next in line. More than just displacing jobs, AI

…

Michelle, 118 Gelman, Audrey, 104 gender norms, 20, 265 General Electric, 142–43 General Mills, 198 General Motors, 142–43 Generations (Howe and Strauss), 98 generative AI, 225–26 Gen X, 98, 107, 111, 215, 218 Gen Y, 98 Gen Z, 215–21, 231 “Get Lucky” (song), 126 Getty, J. Paul, 154

Money in the Metaverse: Digital Assets, Online Identities, Spatial Computing and Why Virtual Worlds Mean Real Business

by David G. W. Birch and Victoria Richardson · 28 Apr 2024 · 249pp · 74,201 words

what has been going on with ChatGPT – and other large language models (LLMs) – is a window into that future. ChatGPT is a form of generative AI, and generative AI is – let’s not beat about the bush – astonishing. It has become part of the mainstream discourse in business, and this is why Microsoft have

…

the overall rate of change in the sector, and it signals the need for a response from the financial services world because the impact of generative AI is both substantial and immediate. As figure 20 shows, growth in this field has been orders of magnitude more rapid than for other technology-enabled

…

2023). This does not mean that LLMs are useless, it just means they must be deployed in the right places. In most financial services organizations, generative AI is seen as a force multiplier. A 2023 Cap Gemini survey of executives identified a number of corporate functions where they saw potential for significant

…

even make payments. This was done not to create a minimum viable product but to demonstrate how simple it is to connect together developments in generative AI and live open banking services. Bloomberg GPT We strongly suspect that financial services organizations will come together to develop their own models, much as Bloomberg

…

economic avatars that we imagine for the Metaverse may not be so far away. Commonwealth Bank of Australia is already examining how it can use generative AI to create faux consumers who can test new products (Adams 2023). They will use the technology to enable machines to process and interpret patterns to

Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley

by Jacob Silverman · 9 Oct 2025 · 312pp · 103,645 words

enriching companies in which Schmidt was an investor. “We are in a decisive decade of military competition with China,” an SCSP official wrote in 2023. “Generative AI should be used to help invalidate the PLA’s investments, increase their uncertainty, reduce risk, and ultimately, help prevent conflict.”3 While nominally a liberal

…

, but few Americans seemed to be enjoying its glories. Software engineers reported leaps forward in productivity, as AI began to write code. The tools of generative AI and video manipulation were initially novel but became less interesting the more one interacted with them. They felt like parlor tricks, modern-day player pianos

…

monetizing its new innovation, and some analysts wondered if the promised gains would ever arrive. Some observers thought that large language models—the technology behind generative AI—had inherent limitations that would limit AI’s potential to go beyond inference and prediction to actual thinking and reasoning. “AI technology is exceptionally expensive

…

-war-fighting-machine/ 3 https://defensescoop.com/2023/09/08/eric-schmidt-led-panel-pushing-for-new-defense-experimentation-unit-to-drive-military-adoption-of-generative-ai/ 4 https://www.techtransparencyproject.org/articles/eric-schmidt-cozies-up-to-chinas-ai-industry-while 5 https://www.politico.com/newsletters/digital-future-daily/2024

…

in writing from the publishers; or ii) used or reproduced in any way for the training, development or operation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, including generative AI technologies. The rights holders expressly reserve this publication from the text and data mining exception as per Article 4(3) of the Digital Single Market

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

by Madhumita Murgia · 20 Mar 2024 · 336pp · 91,806 words

others, to speed up the scientific discovery process.3 Over the past year, we have seen the rise of a new subset of AI technology: generative AI, or software that can write, create images, audio or video in a way that is largely indistinguishable from human output

…

. Generative AI is built on the bedrock of human creativity, trained on digitized books, newspapers, blogs, photographs, artworks, music, YouTube videos, Reddit posts, Flickr images and the

…

book, I wanted to find real-world encounters with AI that clearly showed the consequences of our dependence on automated systems. Now, the rise of generative AI systems has made this need obvious and urgent. Over the past year, we have begun to see, already, the early human impact of technologies like

…

this way now augment or stand in for human judgement in areas as varied as medicine, criminal justice, social welfare and mortgage and loan decisions. Generative AI, the latest iteration of AI software, can create words, code and images. This has transformed them into creative assistants, helping teachers, financial advisers, lawyers, artists

…

, as new AI techniques have grown in sophistication. In the past two years, a new technology known as the transformer has spurred on advances in generative AI, software that can create entirely new images, text and videos simply from a typed description in plain English. AI art tools like Midjourney, Dall-E

…

of AI-generated misinformation in the political areas, and impact on democracy. Other areas of the law being examined include issues of copyright violation by generative AI software, since the systems require the use of copyrighted words, images, voices and likenesses of creative professionals for their training. At an inaugural summit held

…

, policy advocates and human rights defenders from across these regions.22 Their goal has been to discuss the threats and opportunities that deepfakes and other generative AI technologies could bring to human rights work, including identifying the most pressing concerns and recommendations for future policy work in this area. During these workshops

…

Meta’s Horizon Worlds, to play games. Horizon Worlds, for instance, is accessed using Meta’s Oculus Quest 2 virtual reality headset. The platform uses generative AI to build avatars that can provide instantaneous speech translation across languages, to power chatbots in this ecosystem, and even to allow the generation of detailed

…

you’re really experiencing it. You forget it’s not real. It’s just so intimidating.’ The Before and After Ultimately, the human effects of generative AI, or any type of AI-mediated image manipulation, are no different to those engendered by older technologies like Photoshop or even by revenge porn. Clare

…

was so much anxiety and fear around how [frontline workers] were being measured, and if they were measuring up,’ she told me. The rise of generative AI – software that can create human-like text and images – has now normalized the use of AI across modern workplaces. While students have used the likes

…

poor Uber drivers. But this artificial intelligence, it will spread, and it’s coming for everyone.’ CHAPTER 8 Your Rights As algorithm-based decisions and generative AI are woven deeply into our daily lives, people who have found themselves at the sharp end of these systems are finally starting to demand redress

…

Need Is Love’. The paper was first published in June 2017, and it kick-started an entirely new era of artificial intelligence: the rise of generative AI. The genesis of the transformer and the story of its creators helps to account for how we got to this moment in artificial intelligence: an

…

of being shot.’ Cheap Intelligence and Mass Creativity There were, it seemed, two mirror worlds when it came to assessing the potential and impact of generative AI. On the one hand were the businesses, law firms, technologists and students who experimented with it freely and creatively, delighted by its sophisticated and clearly

…

, hours of original music and audio files – all to be labelled by data labourers around the world. Once these human creations had been thoroughly analysed, generative AI models were able to draw out patterns and recreate versions of them. The digital inventions were, of course, inexpensive to create in bulk. They didn

…

robber barons enclosed once-common lands . . . Instead, they are selling us back our dreams repackaged as the products of machines.’15 The promise made by generative AI builders is that the technology will open up a new era of human experience, provide access to cheap intelligence and mass creativity. It will supposedly

…

product line at New York Fashion Week; and in the 2024 movie Here, actors Tom Hanks and Robin Wright will be digitally de-aged using generative AI software. Currently, though – as was the case with the pornographic deepfakes of Noelle Martin and Helen Mort – there are no regulations that govern

…

generative AI technology and therefore legal action is largely non-existent. Artists Holly Herndon and Mathew Dryhurst decided to build something to fight back. They designed a

…

, but actors like Laurence have sparked a wider debate around changing copyright laws to protect human assets like voices and faces from being scraped by generative AI. When we chatted later, she told me she experienced the same Kafkaesque feelings that I had encountered amongst delivery workers at companies like Uber. She

…

vulnerability of having signed away all her rights to it, in any digital media and in perpetuity, as part of exploitative contracts signed years before generative AI was even invented. ‘It isn’t just about protecting jobs,’ she said. ‘AI is nothing more than statistics, it deals in data analytics. It strips

…

knowledge workers, such as lawyers, journalists, consultants and creative professionals, still have work in a few years’ time, when their jobs could be completed by generative AI to a good enough standard? There’s the knock-on question of how a society can be sustained without work, and whether we will need

…

, technologists, philosophers, economists, even politicians – don’t seem to have any, and are just as conflicted and concerned as all the rest of us. Meanwhile, generative AI is catching on like wildfire, racing on through the economy at a pace much faster than any government trying to contain it. I felt that

…

there isn’t.’ * My conversations with Ted led me to look to science fiction as a way to organize my own scattered thoughts on what generative AI could mean for all of us. That’s when I found ‘The Machine Stops’, E. M. Forster’s short story from 1909,21 which I

…

version of reality, which eventually replaces the one people inhabit, felt germane today. When I looked around me, at stories I myself was writing about generative AI producing false or biased content, I began to see this idea everywhere. Forster had described what, more than a century later, we are calling a

…

‘align’ AI software to human values has become central to the current debate – and with it, questions of what these universal human values even are. Generative AI can write fluently, create images and code in a way that is indistinguishable from human creations, and is being transmitted unfiltered to us around the

…

now part of the DNA of AI companies like Anthropic, Google and OpenAI, which is backed by Brad Smith’s Microsoft. These companies have developed generative AI models that run in accordance with a constitution of sorts – a set of ethical rules, compiled internally by the companies – that their AI software is

…

on society’s marginalized and excluded groups: refugees and migrants, precarious workers, socioeconomic and racial minorities, and women. These same groups are disproportionately affected by generative AI’s technical limitations too: hallucinations and negative stereotypes perpetuated in the software’s text and image outputs.7 And it’s because they rarely have

…

inventors and sellers of AI products. It needs the imagination of human artists, writers, actors and musicians whose work is being co-opted to build generative AI, and the expertise of policymakers, economists, academics, philosophers and ethicists, who have seen such waves of radical social change before. Through writing this book and

…

AI systems? 10. What are the channels for citizen empowerment in the face of AI, e.g. opting out of AI systems, data deletion from generative AI systems, the right to choose human over automated decisions? * When I started out as a technology reporter, I was drawn to AI because of the

…

International Peace, April 24, 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/04/24/how-artificial-intelligence-systems-could-threaten-democracy-pub-78984. 22 ‘Deepfakes, Synthetic Media and Generative AI’, WITNESS, 2018, https://www.gen-ai.witness.org/. 23 Yinka Bokinni, ‘Inside the Metaverse’ (United Kingdom: Channel 4, April 25, 2022). 24 Yinka Bokinni, ‘A

…

All You Need’, Arxiv, June 12, 2017, https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762. 3 M. Murgia, ‘OpenAI’s Mira Murati: The Woman Charged with Pushing Generative AI into the Real World’, The Financial Times, June 18, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/73f9686e-12cd-47bc-aa6e-52054708b3b3. 4 R. Waters and T

…

, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/a6d71785-b994-48d8-8af2-a07d24f661c5. 5 M. Murgia and Visual Storytelling, ‘Generative AI Exists Because of the Transformer’, The Financial Times, September 12, 2023, https://ig.ft.com/generative-ai/. 6 Murgia and Visual Storytelling. 7 K. Woods, ‘GPT Is a Better Therapist than Any Therapist I’ve

…

, https://www.ft.com/content/40ba0b91-7e72-415b-8ac6-4031252576cc. 7 L. Nicoletti and D. Bass, ‘Humans Are Biased. Generative AI Is Even Worse’, Bloomberg, June 9, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2023-generative-ai-bias/. 8 ‘Microsoft Responsible AI Standard’, Microsoft, June 2022. Index Abeleira, Carlos (Charlie) ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5

…

data annotation/data-labelling see data annotation/data-labelling deepfakes and see deepfakes facial recognition and see facial recognition future of and see China generative AI see generative AI gig workers and see gig workers growth of ref1 healthcare and see healthcare policing and see policing regulation of see regulation teenage pregnancy and see

…

Central St Martins ref1 CGI ref1 Channel 4 ref1 ChatGPT ref1, ref2 ‘ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web’ ref1 deep learning and ref1 generative AI and ref1 language used to describe ref1 lawyers and ref1 origins and launch of ref1 Sama and ref1, ref2, ref3 transformer and ref1 chemical structures

…

, Pete ref1 Galeano, Eduardo ref1 gang rape ref1, ref2 gang violence ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Gebru, Timnit ref1, ref2, ref3 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) ref1 generative AI ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 AI alignment and ref1, ref2, ref3 ChatGPT see ChatGPT creativity and ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4

AI in Museums: Reflections, Perspectives and Applications

by Sonja Thiel and Johannes C. Bernhardt · 31 Dec 2023 · 321pp · 113,564 words

the development of AI art has played and continues to play a crucial role and might further transform and redesign creative processes. The increase in generative AI and especially large language models (LLMs) has led to a distortion of the public perception of what is meant by AI. At the same time

…

, Schwabe Verlag. https://doi.org/10.24894/978-3-7965-4634-1. Chui, Michael/Hazan, Eric/Roberts, Roger et al. (2023). The Economic Potential of Generative AI. The Next Productivity Frontier. New York, McKinsey & Company. Available online at https://www.mckinsey.de/news/presse/genai-ist-ein-hilfs mittel-um-die-produktivitaet

…

LAION, which provides large datasets to democratize the ability to train models; or even Stability AI, a company that embraces the idea of opensource for generative AI and has worked in the past with the Ludwig Maximilian University Munich. What are also missing are approaches to how citizens might participate in the

…

rest of this paper, let us, however, focus on one specific up-and-coming use of AI, which is strongly connected to the rise of generative AI in the last several years. According to Esposito (2022), modern forms of AI are characterized by algorithms acting as communication partners. We interact with language

…

deeper understanding of the collection by making new connections visible, supporting accessibility, or providing in-depth information. When the survey was conducted, the possibilities of generative AI were not yet widely known, which means that an assessment today would probably be different or lead to other results. Users wanted a tool to

…

have shown the ability of these systems to, for example, generate images from a textual description. This family of techniques has been referred to as generative AI, although generative methods based on machine learning have always existed alongside the other types of tasks mentioned above, such as classification techniques or clustering. One

…

example illustrating this possible use of AI is a recent work commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which involved training a generative AI model on a collection of 180,000 works of art from the museum’s collection. The resulting work titled Unsupervised by the artist Refik Anadol

…

example of content generation can be found in the restoration of works of art. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has collaborated with companies to use a generative AI technique to restore missing edges to Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch. He originally produced a painting slightly larger than the existing one. But the

…

discussed the direction and goals of AI solutions in the museum and accompanied the development of xCurator. For example, the sessions discussed the possibilities of generative AI in ex15 https://karlsruhe.digital/2022/08/ki-pilot-innen-blm/. 237 238 Part 3: Applications ploring the extent to which users would like to

…

see the results of generative image or language models applied to museum data. In this way, developments in multimodal and generative AI were monitored and user requirements were explored in the museum context. The results were documented in written and video form, evaluated, and transferred and applied

…

Hofmann’s interactive installation Wishing Well was produced between 2022 and 2023 as part of the ‘intelligent.museum’ project. It is an artwork that uses generative AI to transform the dreams, wishes, and fantasies orally expressed by exhibition visitors into images. A urinal serves as a wishing well into which visitors speak

…

to question and challenge established artistic conventions and push the boundaries of what can be considered art. Today, we are discussing a similar question, since generative AI models are able to take over artistic tasks such as writing, making music, and painting. This major shift in cultural production has an impact on

…

the future role and self-image of artists. Given the growing influence of new mul- 247 248 Part 3: Applications timodal generative AI models, the question that arises is whether the art world is facing a paradigm shift comparable in scope to the ‘conceptual turn’ (LeWitt 1967; Godry

…

text. This also results in new ways of thinking about creativity and art that are currently being explored through and with the use of multimodal generative AI-technologies. The focus is thus shifting from a final artistic work or product viewed in an exhibition space in a distanced, silent, and contemplative way

…

into the Stable Diffusion 249 250 Part 3: Applications model to generate prompt-based images using AI. There are several examples of multimodal models of generative AI that can generate images from text descriptions, also known as text-to-image generators. The software pipeline of Wishing Well employs the second version of

…

filter. This is also due to the fact that various sensitivities have to be taken into account for different cultural settings—and the results of generative AI therefore have to be evaluated depending on specific countries and cultures. For example, in a US-American setting, AI-generated results that include Nazi content

…

competent and taking diverse cultural, social, political, historical, and religious perspectives and sensitivities into account is thus certainly one of the major challenges in using generative AI technologies. Another ethical issue that has been extensively discussed is the issue of consent regarding the use of artists’ images. Training datasets for text-to

…

AI-generated images and the need for greater transparency and communication regarding the use of artists’ works in AI development. The use and application of generative AI with multimodal models falls within a broader ongoing debate surrounding large language models. Several AI researchers have issued an open call for a moratorium on

…

a manipulated image of Donald Trump evading arrest by law enforcement. In this context, it is always important to keep in mind that the results generative AI technologies produce can be factual, but might also be speculative. For this reason, generative text production as it occurs in the context of large language

…

repeat the content they have been trained on without being able to check it for facticity. 253 254 Part 3: Applications Finally, the use of generative AI technologies is accompanied by a loss of control in the curatorial and artistic process. If artificial creativity is used, agency is automatically relinquished or in

…

and the exhibition space, as striven for not least in the participatory turn. Nevertheless, there are also implications and challenges associated with multimodal models of generative AI that can also be experienced through the interactive installation Wishing Well. This is the case, for example, when the Stable Diffusion model generates images based

…

co-creativity between humans and machines in the exhibition space, as well as conveying ethical dilemmas that are to be expected in any use of generative AI. Yannick Hofmann and Cecilia Preiß: Say the Image, Don’t Make It References Bender, Emily M. et al. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots

…

for museum operators, AI algorithms will also penetrate other areas of museums’ (Fuchs/Lorenz 2019, 140). In future projects, it would be conceivable to use generative AI systems such as ChatGPT to support text production through automation. At the same time, the elaboration of characters and their emotional states, the accentuation of

…

as well as the critical questioning of traditional narratives remain a fundamentally human role in the production of AI-based mediation offers. The use of generative AI systems thus challenges museum art mediation even more so in the area of reworking and fact-checking as well as maintaining a discrimination-critical perspective

…

Preiß discuss the use of AI technologies in art by means of the interactive installation Wishing Well. Wishing Well by media artist Yannick Hofmann uses generative AI to transform the dreams, wishes, and fantasies expressed by exhibition visitors into images. Central aspects addressed are the use of AI technologies in art and

…

how co-creativity between humans and machines can be facilitated, as well as conveying ethical dilemmas that are to be expected in any use of generative AI. In this way, Wishing Well is representative of the ’intelligent.museum’ project, within whose framework it was developed. Abstracts Oliver Gustke, Stefan Schaffer, Aaron Ruß

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by Karen Hao · 19 May 2025 · 660pp · 179,531 words

ideological drives of the people who create them and the winds of hype and commercialization. While ChatGPT and other so-called large language models or generative AI applications have now taken the limelight, they are but one manifestation of AI, a manifestation that embodies a particular and remarkably narrow view about

…

thing I’ve learned: This current manifestation of AI, and the trajectory of its development, is headed in an alarming direction. On the surface, generative AI is thrilling: a creative aid for instantly brainstorming ideas and generating writing; a companion to chat with late into the night to ward off loneliness

…

school friends, or for sparking positive and transformative social movements, there is more to the sleek, entrancing exterior than meets the eye. Under the hood, generative AI models are monstrosities, built from consuming previously unfathomable amounts of data, labor, computing power, and natural resources. GPT-4, the successor to the first ChatGPT

…

South, all suffering new degrees of precarity. Rarely have they seen any “trickle-down” gains of this so-called technological revolution; the benefits of generative AI mostly accrue upward. Over the years, I’ve found only one metaphor that encapsulates the nature of what these AI power players are: empires. During

…

short-term commercial benefit. Companies themselves, which once invested in sprawling exploratory research, can no longer afford to do so under the weight of the generative AI development bill. Younger generations of scientists are falling in line with the new status quo to make themselves more employable. What was once unprecedented has

…

AI-generated content, in part due to growing demands from superiors to do more work. In a November Bloomberg article reviewing the financial tally of generative AI impacts, staff writers Parmy Olson and Carolyn Silverman summarized it succinctly—the data “raises an uncomfortable prospect: that this supposedly revolutionary technology might never deliver

…

are being replaced by the very AI models that were built from their work without their consent or compensation. The journalism industry is atrophying as generative AI technologies spawn heightened volumes of misinformation. Before our eyes, we’re seeing an ancient story repeat itself—and this is only the beginning. OpenAI

…

It is continuing to chase even greater scales with unparalleled resources, and the rest of the industry is following. To quell the rising concerns about generative AI’s present-day performance, Altman has trumpeted the future benefits of AGI ever louder. In a September 2024 blog post, he declared that the “

…

popularity of neural networks, data-processing software loosely designed to mirror the brain’s interlocking connections, now the basis of modern AI, including all generative AI systems. Over subsequent decades the two camps vied for a limited pool of funding and control over the popular imagination of what AI could be

…

short-term profitability. * * * — The entwining of deep learning with commercial interests simultaneously transformed the tech industry and the face of AI development. To the public, generative AI would erupt seemingly out of nowhere in late 2022 with OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT. But from 2012 to 2022, beginning with the ImageNet breakthrough

…

, it was these shifts during the first major era of AI commercialization that laid the groundwork for many characteristics of the generative AI revolution today. For industry, deep learning fueled the improvement and emergence of new products and services, from faster access to information to more efficient

…

text.” People and vehicles in pictures were merely “objects.” Surveillance was merely “detection.” That culture is now at the crux of a raging debate in generative AI over whether tech companies can scrape books and artwork wholesale to train their AI systems. To many AI developers who have long operated under this

…

capitalism. It is fueled and abetted by the culture of AI research that views consuming as much data as possible as its moral responsibility. Generative AI is now also pushing each of these phenomena even further. What made ChatGPT in November 2022 appear as such a stunning leapfrog ahead of anything

…

of neural networks compared with humans would go away at sufficient scale, the challenges have in fact persisted and, by many accounts, only gotten worse. Generative AI models are still unreliable and unpredictable. Even as image generators have grown more photorealistic, they can make mistakes in eerie and strange ways, such as

…

And those patterns are still at times faulty or irrelevant, now just more intricate and more inscrutable than ever. As companies have attempted to refashion generative AI models as search engines, these shortcomings have led to new problems. The models are not grounded in facts or even in discrete pieces of information

…

data or riddled with falsehoods and conspiracy theories. The AI industry calls these inaccuracies “hallucinations.” Researchers have sought to get rid of hallucinations by steering generative AI models toward higher-quality parts of their data distribution. But it’s difficult to fully anticipate—as with Roose and Bing, or Uber and Herzberg

…

behavior is an aberration, a bug, when it’s actually a feature of the probabilistic pattern-matching mechanics of neural networks. This misplaced trust in generative AI could once again lead to real harm, particularly in sensitive contexts. Startups are pushing police departments to adopt software built atop OpenAI’s models for

…

summaries. In one extreme example, the chatbot simplified a report detailing a growing mass in the brain as “brain does not seem to be damaged.” Generative AI models also remain vulnerable to cybersecurity hacks. In 2023, researchers at several universities and Google DeepMind replicated Dawn Song’s data extraction attack against ChatGPT

…

caused the underlying model to regurgitate its training data, which included personally identifiable information, bits of code, and explicit content scraped from the internet. And generative AI models amplify discriminatory and hateful content. Bloomberg, Rest of World, The Washington Post, and many others have shown how image generators like Stable Diffusion and

…

industry as doctrine. And should the industry’s adherence to that doctrine continue unabated, future deep learning models will make the once-unfathomable size of generative AI models today look paltry. In April 2024, Dario Amodei, by then the CEO of Anthropic, told New York Times columnist Ezra Klein that the

…

benign content to frequently disturbing content, including for the purposes of content moderation, much like social media before it. Such moderation was necessary to prevent generative AI systems from reproducing the most vile parts of their all-encompassing datasets—descriptions and depictions of violence, sexual abuse, or self-harm—to hundreds of

…

limits. ChatGPT would make Mark Zuckerberg deeply regret sitting out the trend and marshal the full force of Meta’s resources to shake up the generative AI race. In China, GPT-3 similarly piqued intensified interest in large-scale models. But as with their US counterparts, Chinese tech giants, including e

…

a new process at the company for more comprehensive reviews of critical research. After ChatGPT, these norms would harden with the frenzied race to commercialize generative AI systems. OpenAI would largely stop publishing at research conferences. Nearly all of the companies in the rest of the industry would seal off public access

…

of its hidden workers and its views on whose labor is or isn’t valued, with OpenAI’s empire-esque vision for unprecedented scale. * * * — Before generative AI, self-driving cars were the biggest source of growth for the data-annotation industry. Old-school German auto giants like Volkswagen and BMW, feeling threatened

…

like the chatbots who need them. As self-driving car work largely disappeared from the platform, so did Venezuelans. “They wouldn’t use Venezuelans for generative AI work,” says a former Scale employee. “That country is relegated to image annotation at best.” Scale would soon ban Venezuela from its platform completely, citing

…

Stable Diffusion or Midjourney, which many users deemed the higher-quality products. It was just one example of how, even within the narrow realm of generative AI, scale was not the only, or even the highest-performing, path to more expanded AI capabilities. * * * — With DALL-E 2’s remarkable jump in

…

shifted GPUs away from Microsoft’s research teams to support OpenAI. The company also consolidated all of its GPUs into one pool for better supporting generative AI workloads. “The typical Microsoft employee had no fucking clue what OpenAI was before January last year,” one Microsoft employee remembers. Now they were receiving

…

their superiors about finding ways to intersect their work with OpenAI technologies. The tech giant would experience a rapid proliferation of over one hundred new generative AI projects within just a few months as employees experimented with various ways of using GPT-4 and ChatGPT. In an ironic twist, the aggressive

…

adoption would force Microsoft to grapple with many of the same challenges that other companies would face as they raced to adopt generative AI without fully understanding it. That included causing headaches for the risk and compliance teams. Not everyone was using Microsoft’s internal versions of the technologies

…

ethereal form its name invokes. To train and serve up AI models requires tangible, physical data centers. And to train and run the kinds of generative AI models that OpenAI pioneered requires more and larger data centers than ever before. Before AI, data centers were already growing and sprawling. They were

…

have amped up their public and policymaker influence campaigns with powerful counternarratives: Data centers will grow so efficient, their impact will stop being a problem; generative AI will unlock new climate innovation; AGI will solve climate change once and for all. While the last claim is impossible to prove, the first two

…

There are indeed many AI technologies, as cataloged by the initiative turned nonprofit Climate Change AI, that can accelerate sustainability, but rarely are they ever generative AI technologies. “What you need for climate are supervised learning models or anomaly detection models or even statistical time series models,” says Luccioni, who is also

…

of AI technologies—primarily machine learning tools—that are small and energy efficient, and in some cases could even run on a powerful laptop. “Generative AI has a very disproportionate energy and carbon footprint with very little in terms of positive stuff for the environment,” she adds. Luccioni says her past

…

. In one paper, together with Hugging Face machine learning and society lead Yacine Jernite, the two measured the carbon footprint of running open-source generative AI models as a proxy to what closed companies are building. They found that producing one thousand pieces of text from generative models used as much

…

international politics,” says Cristina Dorador, a microbiologist who lives in the north and studies its rich biodiversity. Now the same narratives are being recycled with generative AI. The accelerated copper and lithium extraction to build megacampuses—and to build the power plants and thousands more miles of power lines to support them

…

of the world’s—ability to imagine different paths where development could exist without plundering natural resources, Ramos says. By enabling the production of massive generative AI models, that scale has also led to the perpetuation of racist stereotypes about the Indigenous peoples already suffering from how the technology was physically built

…

to bargain in part for better protections against AI, the artists, too, had planned to speak candidly about the devastating effects that generative AI was already having on their profession. Generative AI developers had trained on millions of artists’ work without their consent in order to produce billion-dollar businesses and products that now

…

concept artist known for her work on Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange, who was part of the group and filed the first artist lawsuit against several generative AI companies. As they arrived in Washington, several of their meetings were bumped by Altman’s testimony to the following day, scrambling their schedules and

…

boost to advance. But the biggest challenger to its efforts was the vibrant cross-border open-source AI movement, which was rapidly replicating closed corporate generative AI models and putting them out on the internet for anyone to download and use. After vigorously playing catch-up, Meta had become a dominant

…

open-source development; chief scientist Yann LeCun believed in the importance of open science. It was also smart business. Meta didn’t need to sell generative AI models to make money, but unleashing free ones, while integrating them into its core products, could help it establish its AI leadership, attract top

…

Europe, which settled on 1025 for something slightly more restrictive, as lawmakers pushing through the long-gestating EU AI Act felt steamrolled by the sudden generative AI developments and hurriedly searched for ways to account for them. At the start of 2024, the approach would then spread to California with the

…

OpenSubtitles of the dialogue in more than 53,000 movies and 85,000 TV episodes. Alex Reisner, “Revealed: The Authors Whose Pirated Books Are Powering Generative AI,” The Atlantic, August 19, 2023, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/08/books3-ai-meta-llama-pirated-books/675063/; Alex Reisner, “There’s No Longer

…

a New Global Underclass (Harper Business, 2019), 1–288; and author interview with Mary L. Gray, May 2019. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Before generative AI: Florian Alexander Schmidt, “Crowdsourced Production of AI Training Data—How Human Workers Teach Self-Driving Cars How to See,” Working Paper Forschungsförderung 155 (2019), hdl

…

Jade Abbott, April 2023; Matteo Wong, “The AI Revolution Is Crushing Thousands of Languages,” The Atlantic, April 12, 2024, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/04/generative-ai-low-resource-languages/678042. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Among the over seven thousand: “Kevin Scannell on ‘Language from Below: Grassroots Efforts to Develop

…

48, 55 Frontier Model Forum, 305–6, 309 funding, 61–62, 65–68, 71–72, 132, 141, 156, 262, 320–21, 331, 367, 377, 405 generative AI and, 110–15, 121–22 Johansson crisis, 382, 390–92, 393 launch of, 50–51, 52–53 logo, 4, 82, 385 Microsoft partnership. See Microsoft

The Age of AI: And Our Human Future

by Henry A Kissinger, Eric Schmidt and Daniel Huttenlocher · 2 Nov 2021 · 194pp · 57,434 words

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI

by Ethan Mollick · 2 Apr 2024 · 189pp · 58,076 words

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by Parmy Olson · 284pp · 96,087 words

The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians

by Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar · 14 Oct 2024 · 175pp · 46,192 words

The Measure of Progress: Counting What Really Matters

by Diane Coyle · 15 Apr 2025 · 321pp · 112,477 words

These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means

by Christopher Summerfield · 11 Mar 2025 · 412pp · 122,298 words

Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk

by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz · 8 Jul 2024 · 259pp · 89,637 words

Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI

by Anil Ananthaswamy · 15 Jul 2024 · 416pp · 118,522 words

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by Keach Hagey · 19 May 2025 · 439pp · 125,379 words

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by Ray Kurzweil · 25 Jun 2024

Extremely Hardcore: Inside Elon Musk's Twitter

by Zoë Schiffer · 13 Feb 2024 · 343pp · 92,693 words

The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century's Greatest Dilemma

by Mustafa Suleyman · 4 Sep 2023 · 444pp · 117,770 words

Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War

by Raj M. Shah and Christopher Kirchhoff · 8 Jul 2024 · 272pp · 103,638 words

What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures

by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson · 17 Sep 2024 · 588pp · 160,825 words

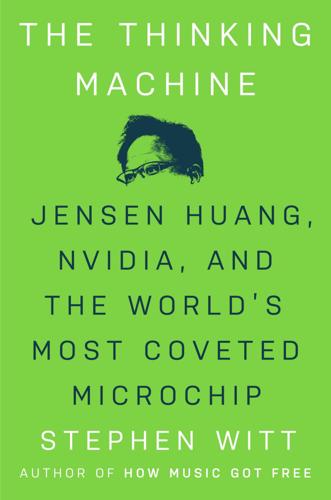

The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World's Most Coveted Microchip

by Stephen Witt · 8 Apr 2025 · 260pp · 82,629 words

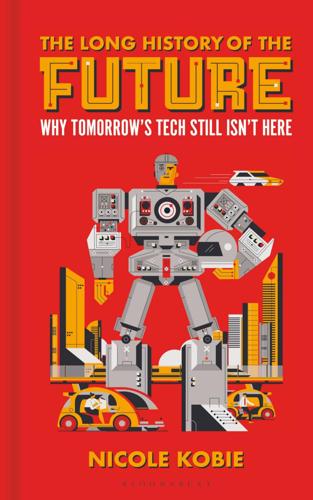

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by Nicole Kobie · 3 Jul 2024 · 348pp · 119,358 words

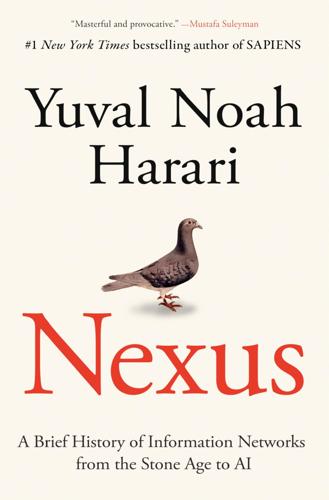

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks From the Stone Age to AI

by Yuval Noah Harari · 9 Sep 2024 · 566pp · 169,013 words

Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age

by Vauhini Vara · 8 Apr 2025 · 301pp · 105,209 words

Architects of Intelligence

by Martin Ford · 16 Nov 2018 · 586pp · 186,548 words

Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart

by Nicholas Carr · 28 Jan 2025 · 231pp · 85,135 words

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber · 29 Oct 2024 · 292pp · 106,826 words

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

by Brian Merchant · 25 Sep 2023 · 524pp · 154,652 words

Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why It Matters

by Joanna Walsh · 22 Sep 2025 · 255pp · 80,203 words

The Sirens' Call: How Attention Became the World's Most Endangered Resource

by Chris Hayes · 28 Jan 2025 · 359pp · 100,761 words

Irresistible: How Cuteness Wired our Brains and Conquered the World

by Joshua Paul Dale · 15 Dec 2023 · 209pp · 81,560 words

Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity

by Paul Kingsnorth · 23 Sep 2025 · 388pp · 110,920 words

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by Anu Bradford · 25 Sep 2023 · 898pp · 236,779 words

Hope Dies Last: Visionary People Across the World, Fighting to Find Us a Future

by Alan Weisman · 21 Apr 2025 · 599pp · 149,014 words

Breaking Twitter: Elon Musk and the Most Controversial Corporate Takeover in History

by Ben Mezrich · 6 Nov 2023 · 279pp · 85,453 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

Abundance

by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson · 18 Mar 2025 · 227pp · 84,566 words

Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference

by Bregman, Rutger · 9 Mar 2025 · 181pp · 72,663 words

The BBQ Book

by Tom Kerridge · 26 Feb 2025 · 132pp · 39,547 words