We Need New Stories: Challenging the Toxic Myths Behind Our Age of Discontent

by

Nesrine Malik

Published 4 Sep 2019

This makes it easier for the tool of universalism to be effective. But again, this is not the fault of representative identity politics, it is the fault of white monopoly on the means of cultural production. The very origin of the identity politics movement was an effort to find common cause, rather than ghettoise demands for equality. The history of the term ‘identity politics’ and how it was first used illustrates how much it has been corrupted and deliberately misunderstood over the years as divisive and distracting from ‘universal’ causes. In the mid-1970s, a group of Afrocentric black feminist scholars and activists in the United States formed an organisation specifically to address the concerns of black women, concerns which they felt had been ignored by the wider feminist movement.

…

This is an additional complication of narrator dominance – it exhausts and confounds the flourishing of new voices by restricting their ability to expand, to create a body of work that is not restricted to constantly responding to and challenging myths. And even this effort, to expand the knowledge bank, as Lola and her fellow students tried to do at Cambridge University, is met with resistance. Ferguson also has strong views on #MeToo. The ghettoisation of women or people of colour in ‘their lane’ in publishing and journalism is not an issue for him. If one is ‘an’ authority, they are then ‘the’ authority, moving from economic history to empire, to Islamism, to sexual politics and consent. On the latter he has this to say: ‘I wonder: do we risk sliding into a kind of secular sharia, in which all men are presumed to be sexual predators and only severe punishments can prevent routine rape?

…

Of the three books and book series by these writers, only one had a main non-white character, who was half Latina. In 2017, the Sunday Times top ten bestselling hardback non-fiction chart did not include any writers who weren’t white. In the UK, the Writing the Future research reported in 2015 on the effect of ghettoising minority voices in either confessional non-fiction or literary fiction about race or colonialism. The result is an under representation of black and ethnic minority British writers in the bestselling writing genres. The problem is in the ranks of publishing as well, according to the report, only 8 per cent of UK publishing comes from a black and ethnic minority background.

Legacy of Empire

by

Gardner Thompson

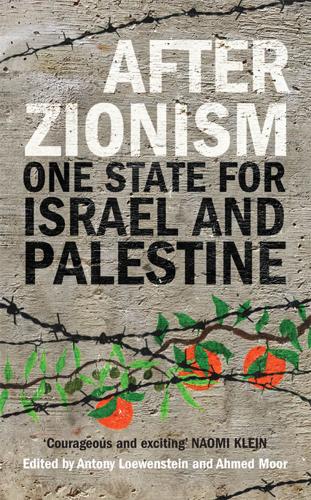

As noted above, even in the early twentieth century Israel Zangwill’s Jewish Territorial Organisation saw no necessary link between the search for a homeland and Palestine: ‘we do not attach any real value to our supposed “historical rights” to that country’.23 Jewish experience in the post-70-ad diaspora has been distorted by generalisation. The Zionist version of history presents these Jewish communities, over many centuries, as uniformly powerless and constantly subjected to persecution. There were, of course, some solid grounds for this view. Ghettoisation is a historical fact, as are innumerable episodes of persecution (and apprehension of persecution, even in its absence). The pogroms in Russia, where so many Jews were living, were an accompaniment of modern political Zionism and, up to a point, explain it. This much is certainly not myth. Nonetheless, Zionist history was knowingly misleading.

…

INDEX Page numbers in bold refer to tables; page numbers in italics refer to illustrations; ‘n’ after a page number indicates the endnote number. 1929 violence and disturbances, 159, 161, 184, 195, 203, 215–16, 223 1930 Hope-Simpson Report, 183, 186, 187, 297 1930 Passfield White Paper, 76, 187–90 1930 Shaw Report, 186, 187, 197, 202, 297 casualties, 185 Hebron, 184–5 inter-communal antagonism, 211 land issue, 186, 209–10 racial character of, 185 Western Wall, Jerusalem, 184, 185, 186 1933 protests and rioting, 215 1936 Arab Revolt/Great Revolt, 126, 161, 203, 208, 218–21, 223 British army, 220–1 casualties, 221 Hebron, 220 Jaffa, 218, 220–1 Peel Commission and Report, 221, 222, 233 strikes and boycotts of Jewish businesses, 221 truce, 220, 221 see also Peel Commission and Report 1938 Arab Revolt, 126, 207, 228–33, 249 Arab-on-Arab violence, 230–1 British army, 228, 230, 230 casualties, 230 destruction, 231, 232 Haganah, 229 Irgun militia, 229 Jenin, 231, 232 Jewish Agency, 229 partnership of British and Jewish authorities, 228–9 repression and group/village punishments, 228, 229 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 264–72, 294–5, 333n6 1st stage/‘civil war’, 265–9, 270, 272 2nd stage/inter-state stage, 269–72 1948 invasion of Israel by Arab League forces, 269 1949 Armistice lines, 261 Abdullah I, King of Transjordan, 266, 268–9, 270 armistices, 270 Ben-Gurion, David, 264–5, 270 Deir Yassin, 332n4 Haganah, 265–6, 271 Haifa, 266 IDF 266, 270, 271 Israeli victory, 271, 274 Palestinian refugees, 274, 276 terrorism, 265 truce, 270 yishuv, 264–6 1956 Suez Crisis (Second Arab–Israeli War), 272, 332n9 1967 Six Day War (Third Arab-Israeli War), 272–3, 274, 284 Palestinian refugees, 274 settlement programme, 274 UN 242 Resolution, 275 1973 Yom Kippur, 273 nuclear exchange, 273 Aaronovitch, David, 289 Abbas, Mahmoud, 279 Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman Sultan, 34–5 Abdullah I, King of Transjordan, 266, 332n6 Arab Legion/Royal Jordanian Army, 268, 270 Peel Report, 268–9 Achcar, Gilbert, 294, 300 Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginsberg), 14, 15, 16, 29, 36, 80, 116, 241, 286 AHC (Arab Higher Committee), 218–20, 219, 238, 244, 262 banning of, 230 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 220 partition of Palestine, opposition to, 227–8 UNSCOP, 260 Alexander II, Tsar of Russia, 4 aliyah (wave of Jewish immigration into Palestine), 316n30 1st aliyah, 22–3, 28, 39, 42 2nd aliyah, 16, 21, 23, 25, 26, 28, 39 see also Jewish immigration to Palestine Allenby, Edmund Henry Hynman, Field Marshal, 71, 101 American Council of Judaism, 253–4, 331n11 American Zionist Federation, 296 Amery, Leo, 87, 93 Andrews, Lewis, 228 anti-Semitism, 264, 298 1905 Aliens Act, 84–5 anti-Zionism/anti-Semitism distinction, ix, 22, 39, 123, 304, 318n6 Balfour Declaration, xi–xii, 85–6, 88, 89 Britain, xi–xii, 85–6 British Mandate for Palestine, 141 as conspiracy theory, 87–8, 322n59 Europe, xi, xii, 4 Evian Conference, 247–8, 299 France, 315n11 Jewish Question, x, 3, 6 Nazi Germany and state-sponsored anti-Semitism, 161, 247, 296 Poland, 161, 247 USA, xi, 86, 298 see also discrimination; persecution Arab Agency, 168, 170, 180, 199, 327n15 Arab opposition to, 164, 168–9, 303 Arab-Israeli conflict, ix, 163, 280, 289, 304 Arab-Israeli reconciliation, xv, 280, 304 Arab-Jewish rapprochement in Palestine, 22 Arab League, 266, 267, 269, 275, 332n5 Arabic, 21, 29, 109, 112, 149, 181, 209 as official language of Palestine, 133, 158 Arabs, 182 anti-British feeling, 118–19 Arab Agency, opposition to, 164, 168–9, 303 ‘Arab Jews’, 21–2 Arab kingdom in Palestine, 170–1 Balfour Declaration, Arab population in, 97–8, 99, 100, 101, 121 Balfour Declaration, opposition to, 55, 65, 105, 108–109, 119, 121, 125–6, 129, 136, 153, 177, 197 British Mandate for Palestine, 133, 135, 141–2, 197, 264 Chancellor, John and, 195–201 Christian Arabs, 30–1, 32, 33, 39, 55, 109, 214, 224, 284 destruction of Arab property, 228 disillusionment with the British, 115 disregard for, 141–2, 172, 213, 250–1 eviction from Palestinian land, 24, 183, 186, 209, 210, 271, 278 exclusion from Palestinian land, 26, 30, 200, 271 as indigenous Palestinian population, xi, 12, 17–18, 23, 36–7, 39, 44, 49, 58–9, 89–90, 91, 116, 149, 151, 152, 262, 271, 295, 302–303 Jewish Agency and, 168 Legislative Council, opposition to, 164, 165–6, 169, 177, 199 Palestine as Jewish national home, opposition to, 217, 223, 228, 240 Peel Commission and Report, opposition to, 161, 221, 227–8 self-determination, 131–2, 140 unemployment, 192, 197, 210, 285 Zionist excess against, 163 Arafat, Yasser, 275, 277 arms, 112, 140, 154 armed Arab resistance, 215, 220, 241 armed Jews in Palestine, 30, 118, 171 death penalty for unauthorised possession of, 228 Haganah, 121, 216 intifadas, 279 PLO armed struggle, 275 Zionism and, 121, 147, 264, 284, 297 Ashkenazi Jews, 21–2, 41, 155 Asquith, Herbert Henry, xii, 58, 59, 61, 68, 69, 77, 100 replaced as Prime Minister by Lloyd George, 70 assimilation, 20, 42, 43, 162 criticism of, 7–10 intermarriage and, 9 Jewish identity and, 9–10 Jewish Question and, 5, 6–8 Montagu, Edwin, 88–9 reverse assimilation, 28 secularism and, 5 support for, 12 USA, 42, 48–9 Weizmann, Chaim, 8–9, 49 Zionism and, 7–10 see also identity Atatürk, Kemal, 136 Attlee, Clement, 243, 256–7 Australia, 12, 248 Azouri, Najib, 31 Babylonia, 44, 45 Baldwin, Stanley, 169 Balfour, Arthur, 85, 142, 147, 148–9, 258, 300 1905 Aliens Act, xi, 41, 84–5 Balfour Declaration, 72, 73, 74, 76, 93, 97, 101, 110, 148 death, 233, 331n15 Ireland, 125 Zionism and, 84 Balfour Declaration (1917), 36, 57–8, 72–4, 116, 148, 188, 263, 294, 300, 301, 304 1st anniversary, 108 4th anniversary, 122 100th anniversary of, xiii–xv, 324n15 Balfour, Arthur, 72, 73, 74, 76, 93, 97, 101, 110, 148 Black Letter, 190, 191, 193 British Mandate for Palestine and, 105, 115, 127, 132, 134, 135, 138, 146, 148 Chancellor, John, Sir, 195–6, 197, 199, 200, 201 Christian Zionism and, 55, 74, 92–4 Jewish state in Palestine, 96–7, 99 League of Nations Mandate and, 105, 115, 127, 132, 134, 135, 138, 146, 148, 170, 199 legitimacy, 263 Lloyd George, David, x–xi, 58, 73, 74–80, 93, 97, 100, 101, 105, 148 Montagu, Edwin, 74, 88–91, 92 Palestine as Jewish national home, 72, 95, 189, 197 policy review, 105, 113, 137, 170 self-determination, 77, 105, 110, 115, 263 text of, 72, 95–8 Weizmann, Chaim, 36, 74, 75, 80–3, 90–1, 94, 96, 97, 98, 116, 117, 134, 321n43 World War I, 73, 76–7, 83–4, 98, 101, 105, 148 Zionism and, xi, xiii, 95–6, 98, 99, 194, 251 as Zionism’s ‘Magna Carta’, 98, 317n74 see also Balfour Declaration, criticism and opposition to Balfour Declaration, criticism and opposition to, xiv, 88–92, 98–101, 106, 108, 113, 148, 159 1919 King-Crane Commission Report, 110–13, 114, 115, 142, 233 1920 disturbances of Nabi Musa, Jerusalem, 113–17, 174 1921 Deedes Letter, 121–3 1921 disturbances in Jaffa, 118–20, 121, 127, 148, 174 1921 Haycraft Report, 118–20, 123, 144 anti-Semitism and, xi–xii, 85–6, 88, 89 Arab opposition to, 55, 65, 105, 108–109, 119, 121, 125–6, 129, 136, 153, 177, 197 Arab population in the Declaration, 97–8, 99, 100, 101, 121 Christian Arabs, 109 colonialism, 95, 142 consequences, xiii, 64, 99, 102, 120, 125, 138, 148–9, 185–6, 195, 198 contradictions, x–xi, 18, 99–100, 105, 106, 115, 138, 161, 162, 195–6, 200, 297 failure of, 58, 100–102, 139, 189, 195, 233 Ireland, 105, 125–7 London, 105, 122, 127 nimbyism, xi, 74, 86–8 Palestine, 108–15 as short-term appeal for help, 74 suspension of Jewish immigration, 120, 177, 203 violence, 105, 113, 118, 122 Zionism, opposition to, 108, 111–13, 115, 118–19, 122 Bar Kokhba revolt (132 AD), 45 Barbour, Nevill, 149 Barr, James, 69, 140 Basel (Switzerland), 1, 2 1st Zionist Congress (1897), 15, 34, 42, 251, 314n6 Basel Programme, 2, 29, 33, 38, 251, 285, 287, 289, 296 full text, 3 Bedouins, 24, 153 Begin, Menachem, 246 Bell, Gertrude, 108 Ben-Ami, Shlomo, 289, 296 Ben-Gurion, David, 24, 26, 27, 30, 37, 50, 80, 109–10, 152–3, 229, 238, 257, 326n5 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 264–5, 270 Biltmore Programme, 251–2 Declaration of Independence, 267 as first Prime Minister of Israel, 326n5 Histadrut, 180 IDF 333n25 Judaism, 52 transfer of population, 226 World War II, 245, 249 Zionism, 180, 289–90, 295–6 Bentwich, Herbert, 17 Bentwich, Norman, 163 Betar, 173, 185 Bethlehem, 45, 225 Bevin, Ernest, 255–6, 257–8, 297 Bible/Hebrew Bible, 11, 48, 53, 75, 94, 229, 285, 314n8 Old Testament, 51, 52, 53, 84, 93 Zionism and, 50–2, 93 Biltmore Conference (New York, 1942), 247, 251, 254 Biltmore Programme, 251–3 Birnbaum, Nathan, 41 Black Letter, 190–4, 204, 206, 213 see also MacDonald, Ramsay Bloudan Conference (1937, Syria), 231 Blum, Leon, 48 Bols, General, 117 Bonaparte, Napoleon, 92, 302 Borochov, Ber, 25–6, 28, 293, 316n48, 333n1 Brandeis, Louis, 84, 86 Bren, Josef Chaim, 148 Breuer, Isaac, 19 Brezhnev, Leonid, 273 Britain 1905 Aliens Act, xi, 41, 84–5 anti-Semitism, xi–xii, 85–6 colonialism, xii, xiii, 124, 300–301 endorsement of Zionism, x, 38, 52, 53, 57, 72, 74, 296, 302 fascism, 48 France and, 63–4, 68, 69–70, 77, 100, 139–40 ‘indirect rule’, 327n15 Jewish characters in English novels, 54, 319n44 Jews in, 35, 41, 48, 89, 237 legacy for Palestine, xiii, 239, 300 Middle East, 68, 70, 72, 234 nimbyism, 141, 254, 298, 300, 334n10 Ottoman Empire and, 61–2, 64, 71, 72 Palestine and, xii, 57, 58–9, 66, 68–9, 148, 239–40 responsibility for Palestine, xv, 298–300, 304 USA and, 243, 255–6 War Cabinet, 70, 87, 93, 95 World War I, 70–1, 72, 76–7, 87, 123, 139 see also the entries below related to Britain; Balfour Declaration; House of Commons; House of Lords; Sykes-Picot Agreement British army, 138, 139, 142, 255 1929 Manual of Military Law, 228 1936 Arab Revolt, 220–1 1938 Arab Revolt, 228, 230, 230 British military administration in Palestine, 146–7 British Mandate for Palestine, x, xi, xii, 17, 74, 103, 104, 105, 127 1923: 164, 169–71, 173, 215 1945 onwards, 255 1947 British abdication, x, xi, 222, 243, 244, 255, 257–8, 264, 297, 298 anti-Semitism, 141 Arab opposition to, 135, 197, 264 Arab population in, 133, 141–2 Balfour Declaration, 105, 115, 127, 132, 134, 135, 138, 146, 148 British government in London, 135, 136–42 British personnel in Palestine, 138–9 case against keeping Palestine, 139 colonialism, 135, 138, 174, 240 contradictions, 223, 224, 226 criticism of, 234–5, 240–1, 263 ‘divide and rule’, 174, 175, 231 failure of, 240, 258, 297, 302 ‘indirect rule’, 174, 179, 327n15 Jewish Agency, 121, 123, 132, 133, 143, 167, 168, 180 Jewish capital and enterprise, 135, 142–4, 158, 262 legitimacy of, 131, 197, 262–3 nimbyism, 141, 254 notables/eminent families, 174–5, 241 Palestinian underdevelopment/backwardness, 150, 151, 153, 154 UNSCOP, 263–4 violence against British targets, 246, 255 Weizmann, Chaim, 134, 146, 147, 149, 158 Wilson’s Fourteen Points and origins of the mandate, 106–107 World War II, 234, 239, 254, 257 Zionism, 115, 132, 133, 134, 135, 138, 140, 142–7, 149, 158, 161, 167, 173–4, 190, 194, 211, 217, 241, 254, 297–8 see also ‘Handbook of Palestine’; League of Nations Mandate British White Paper (1922), 49, 127–30, 134, 188 Arab reply to, 129, 141, 199 Balfour Declaration and, 128, 130 ‘economic absorptive capacity’, 128–9, 167, 188 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 128 Legislative Council, 128, 129, 164 Palestine as Jewish national home, 127, 130 self-government in Palestine, 128 Zionism, 127–8, 129, 130 British White Paper (1930, Passfield White Paper), 76, 187–90, 191, 192, 203–204 annulled by Zionists, 190, 194 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 188, 203–204, 206 Palestine as Jewish national home, 188, 189, 193, 194 British White Paper (1939), 161, 171, 233–9, 240, 242, 244, 251, 260, 266, 297 criticism and opposition to, 238–9, 245 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 254 Jewish state in Palestine, 238 nimbyism, 237 Palestine as Jewish national home, 235–6, 240, 255 Palestine as unitary state, 234 Zionism, 236, 243, 245 the Bund, 20 Cable, J.E., 269 Cambon, Jules, 78 Camp David, 278 Canaan, 11, 51, 53–4 Canaanites, 44, 155 Canada, 12, 248, 299 Carson, Edward, Sir, 70, 87 Carter, Morris, Sir, 330n82 Cassius Dio, 45 Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, 4 Cecil, Robert, Lord, 93, 95–6 Chamberlain, Joseph, 79 Chancellor, John, Sir, 194, 195, 212, 257, 302 Arabs and, 195–201 Balfour Declaration, 195–6, 197, 199, 200, 201 as British High Commissioner of Palestine, 159, 161, 185, 187, 189, 194–203 despatch of January 1930: 197–200 League of Nations Mandate, 199–200 ‘Reasons for Retiring’, 201 Channing, William Ellery, 286 Childers, Erskine, 301 children of Israel, 51, 75, 318n15 Chomsky, Noam, 281, 289 Christian Zionism, 51, 53–5, 75, 229, 253 anti-Semitism, 88 Balfour Declaration, 55, 74, 92–4 Britain, 82, 142 Christian Zionism/Jewish Zionism comparison, 55 Christianity, 6, 46 Christian Arabs, 30–1, 32, 33, 39, 55, 109, 214, 224, 284 Christian-Muslim associations, 214 Jesus Christ, 46, 54 Protestantism, 54, 123, 152, 285–6 Roman Catholicism, 40, 77, 123, 315n11, 330n85 see also Christian Zionism Churchill, Winston, 123 1922 British White Paper, 127 as Colonial Secretary, 136, 143 Irgun militia and, 332n6 Palestine and, 136–8 Zionism, 69, 87, 136 Clayton, General, 109 Clemenceau, Georges, 70, 139 Cohen, Hillel, 183, 281, 284, 290 Cohen, Michael J., 34, 39, 193, 236 Cold War, 243, 256, 264, 272, 273, 280 colonialism, 33, 147, 259, 281, 283 Balfour Declaration, 95, 142 Britain, xii, xiii, 124, 300–301 British Mandate for Palestine, 135, 138, 174, 240 European colonialism, 283, 284 hybrid colonialism in Palestine, xiii, 142, 159, 218, 297–8 nationalism and, 289–90, 301 Zionism and, 281, 283–7, 289–90 Zionist colonisation of Palestine, xiii, 3, 15, 16–18, 22, 23, 31, 171, 173, 193, 198, 211, 216, 289, 294, 295, 299 Congreve, General, 49, 125–6, 139, 145–6 conversion, 5–6, 40, 41, 54 Cook, Thomas, 54 Coupland, Reginald, 330n82 Crane, Charles, 110–13 see also King-Crane Commission Report Crimean War, 63, 70 Crossman, Richard, 82 Curzon, Lord, 91–2, 109, 148–9 Cushing, Caleb, 286–7 Cyrus the Great, 44 Daily Mail (newspaper), 66, 95 The Daily Telegraph (newspaper), 233 Dalton, Hugh, 257 Dayan, Moshe, 273, 281 De Bunsen, Maurice, Sir: 1915 Report of the de Bunsen Committee, 61–4, 67, 68, 69, 70 Deedes, Wyndham, Sir, 121–3 diaspora (Jewish diaspora), 10, 24, 41, 53, 185, 265, 275, 280 70 AD diaspora, 45–6 discrimination, 5, 40, 43, 48, 117 Dominican Republic, 247 Dreyfus Affair, 4, 48, 315n11 Drummond Shiels, Thomas, Sir, 186 Dubnow, Ze’ev, 23, 50 East Africa, 11, 36, 75, 84, 107, 137 Eastern Mediterranean, xvi–xvii, 11, 45, 62, 66, 79, 94 The Economist (newspaper), 101 Eder, David, 119–20 Egypt, 45, 274 1936 demonstrations and strikes, 218 1956 Suez Crisis, 272, 332n9 1967 Six Day War, 272–3 1973 Yom Kippur, 273 Britain and, 11, 63, 69, 139 Gaza, 271, 272 Einstein, Albert, 47–8, 81, 159, 243 El Arish (Sinai), 11, 71, 75 Eliot, George: Daniel Deronda, 54, 142, 319n44 English (language), 133, 158, 181 Enlightenment, 3, 5 Haskalah/Jewish Enlightenment, 5, 19 Epstein, Yitzhak, 1, 14, 16–18, 25, 103, 241, 271–2, 286 equality, 8, 120, 190, 252 Eretz Yisrael (The Land of Israel), 13, 27, 28 Europe, xvi–xvii, 4 anti-Semitism, xi, xii, 4 Central Europe, xi, xii, 41 colonialism, 283, 284 Eastern Europe, 4, 7, 23, 47, 84, 240, 284 interest in Palestine, 152 Jewish Question, 3–4 Jews’ conversion to Christianity, 6 Exodus 1947 affair 259–60 Evian Conference (France, 1938), 246–9, 254 anti-Semitism, 247–8, 299 nimbyism, 299 Zionism, 248–9 Faisal I, King of Syria, 58–9, 71, 111, 117, 140, 170, 179, 263, 320n8 Emir, 110, 145 Fatah, 275, 278 fellahin (labourers), 22, 141, 209 Filastin (newspaper), 32, 221 Ford, Henry, 298 France, 4, 48, 58, 59, 218, 315n11 Britain and, 63–4, 68, 69–70, 77, 100, 139–40 Middle East, 68, 139 Palestine and, 140 Syria, 103, 104, 107 Zionism, 78 see also Sykes-Picot Agreement French Revolution, 3, 8 Galilee, 45, 46, 152, 168, 225, 229 Gandhi, Mahatma, 233 Gaza, 225, 259, 261, 273, 279, 280, 282 Egypt and, 271, 272 intifada, 278 Palestinian Arabs in, 280 Palestinian National Authority, 277 George V, King of the United Kingdom, 145 Germany, 70, 71, 73, 100, 139, 237 Jews in, 6–7, 8 see also Nazi Germany ghetto, 10, 14, 16, 89, 91 ghettoisation, 46 Golan Heights, 261, 273, 274–5, 282 Goldie, Annabel MacNicoll, Baroness, xiv–xv Great Powers, 13, 16, 29, 33, 34, 38, 40, 283 Greece, 78–80, 330n86 1919–22 Greco-Turkish War, 79 Grey, Lord, 73, 99–100, 101 Gruenbaum, Yitzhak, 249 Ha’aretz (newspaper), 182 Habash, George, 275 Haganah (Jewish militia), 167, 173, 216, 259, 267, 271, 290, 332n4, 333n25 1938 Arab Revolt, 229 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 265–6, 271 arms, 121, 216 IDF, 266, 271 Plan D, 266 World War II, 245 Haifa, 62, 64, 140, 152, 259, 260, 261, 282, 325n54 1933 protests and rioting, 215 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 266 Jewish population of, 207 Sykes-Picot agreement, 67, 68 terrorism, 229 Young Men’s Muslim Association, 215 Halevi, Chaim, 185 Halifax, Lord, 248 Hamas, 277–8, 329n74 Hammond, Laurie, Sir, 330n82 ‘Handbook of Palestine’ (1922), 150–1, 153–8, 159 see also Samuel, Herbert, Sir Hankey, Maurice, 77 Hapoel Hatzair (Young Worker) party, 26–7 Hashemites, 64, 65, 268 Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), 5, 19 Hattersley, Roy, 302 Haycraft, Thomas, Sir: Haycraft Report, 118–20, 123, 144, 297 Heath, Edward, 334n10 Hebrew, 26, 27, 167, 181, 209 as national language for Zionism in Palestine, 41, 50, 168, 316n36 as official language of Palestine, 133, 158, 168, 175 Hebron, 184–5, 220, 274 Hertzberg, Arthur, 14, 38, 50, 283, 291 The Zionist Idea, 14 Herzl, Theodor, 1, 2, 3, 4, 38, 47, 48, 88, 287, 288, 300, 317n74 alternatives to Palestine, 11 on anti-Semitism, 88 Arabs as indigenous Palestinian population, 36–7 assimilation, 7–8, 49, 162 death of, 34, 36, 37 diplomacy, 34–7, 80 on infiltration, 29, 34 Jewish Question, 1–2, 303 Judenstaat/The Jewish State, 1–2, 7–8, 10, 11, 29, 298 Political Zionism, 2, 15, 16, 50 World Zionist Organisation, 23, 34 Zionism, 2, 36–7, 55, 289, 314n5 Herzog, Chaim, ix Hess, Moses, 13, 314n5 Histadrut (labour federation), 167, 180, 181, 193, 267, 326n5 Hitler, Adolf, xi, 43, 107, 161, 207, 218, 237, 247, 293, 296, 300 al-Husayni, Amin and, 244 see also Nazi Germany; Nazism Hobsbawm, Eric, 48 Holocaust, xiv, 246, 265, 271, 293–4 Auschwitz, 49, 293 survivors of, 49, 254, 259, 294, 304 Holy Land, 11, 14, 21, 47, 54, 63, 93, 108, 112, 154, 198 Holy Places, 63, 64, 67, 75, 77, 175, 214, 216, 303, 320n10 Hope Simpson, John, Sir, 186–7 1930 Hope-Simpson Report, 183, 186, 187, 297 House of Commons (Britain), 76, 137, 190, 201, 258 House of Lords (Britain), 304 2017 debate on occasion of the Balfour Declaration centenary, xiii–xv, 300 Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion), 4, 7, 42 al-Husayni, Abd al-Qadir, 215, 267–8 al-Husayni, Amin, 33, 161, 175, 176, 177, 180, 212–14, 212, 215, 332n6 1937 Bloudan Conference, 231 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 266–8 AHC, 218, 219–20, 219 exile, 230, 244 Hitler, Adolf and, 244 Holy War Army, 267 radicalisation of 217, 244 SMC, 179, 213 al-Husayni, Jamal, 267 al-Husayni, Kamil, 175 al-Husayni, Musa Kazim, 136, 175, 176, 177, 179, 211–12, 212, 213 death, 215 al-Husayni, Tahir, 33, 175 Husayni dynasty, 175, 176, 177, 179, 218 Hussein, Abdullah, 170 Hussein, Faisal, see Faisal I Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, 64–6, 67, 100, 320n8 Hussein bin Talal, King of Jordan, 276 identity, 4, 6 Arab-Jewish identity, 170 assimilation and Jewish identity, 9–10 Jewish identity, 15, 170 Jewishness, 10, 54 ‘melting-pot’ metaphor, 5–6 national identity, 32, 283 Palestinian national identity, 32 see also assimilation IDF (Israel Defense Forces), 272, 273, 276, 278, 290, 333n25 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 266, 270, 271 as army of occupation/instrument of colonial repression, 274 Haganah and, 266, 271 Lebanon, 276 Operation Thunderbolt, Entebbe, 276 PLO, 276 India, 62, 69, 92, 201, 256, 260 intermarriage, 5–6, 9, 40 intifada, 279 1987–1993 first intifada, 278 2000–2005 second intifada, 278–9 Iraq, 251, 280, 330n84 oil, 140 see also Mesopotamia Ireland, 105, 108, 123–7, 133, 255, 300–301 1916 Easter Rising, Dublin, 124, 324n31 independence from Britain, 124 Sinn Fein, 124 Irgun militia, 245, 246, 290, 332n6, 333n25 1938 Arab Revolt, 229 establishment of, 173 violence, 238, 255, 332n4, 332n6 World War II, 245, 246 al-‘Isa, Isa, 32 Islam, 47, 151, 180, 216 Islamic revivalism, 215 Israel (state of Israel), 227, 273–4, 282 1948 Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, ix, 44, 266, 267, 294 the army and, 290–1 origins of, ix, xiii, 290–1, 300 Palestinian Arabs in, 280 settlement policy, 274 territorial limits, 274 UN 242 Resolution, 275 USA and, 280 Istiqlal (Arab Independence Party), 211, 214, 266 Italy, 49 Jabotinsky, Ze’ev (Vladimir), 143, 171, 172, 245, 271, 279, 284 Betar, 173, 185 The Iron Wall, 164, 171 Revisionist Party, 164, 167, 173, 185 Jaffa, 21, 25, 209, 228, 261 1921 disturbances, 118–20, 121, 127, 148, 174, 203 1932 National Congress of Arab Youth, 208 1933 protests and rioting, 215 1936 Arab Revolt, 218, 220–1 Arab population in, 182, 221 Jeffries, Joseph, 65–6, 113, 126, 143, 164, 168–9, 215, 303, 324n15 Balfour Declaration, 95, 96, 99, 101, 116 Palestine: The Reality, 324n15 Jerusalem, 23, 45, 63, 192, 228, 261, 278, 314–15n8 1920 disturbances of Nabi Musa, 113–17, 174, 175, 179, 203 Arab-Jewish relations, worsening of, 114 Britain and, 71 settlement programme, 274 status of, 280 Western Wall, 184, 185, 186, 328n24 Jewish Agency, 188 1938 Arab Revolt, 229 Biltmore Programme, 252 British Mandate for Palestine, 121, 123, 132, 133, 143, 167, 168, 180 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 203, 209 as parallel government alongside the mandatory government, 168 SMC/Jewish Agency comparison, 179–80 unique status of, 167 UNSCOP, 260 see also Zionist Commission Jewish history, 40, 44–50 British Mandate for Palestine and, 134, 146 ‘exile’ from Judea, 45–6 exile from Palestine, 44, 45, 46, 49, 53, 58, 271, 284 ‘return’ to Palestine as Jewish national homeland, 40, 44, 46, 49, 53, 271 Zionist version of, 44, 46, 47, 49–50, 127, 134, 271 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 39, 149, 205, 206, 239, 280, 302–303 1920s, 159, 205–206, 223 1922 White Paper, 128 1930 White Paper, 188, 203–204, 206 1930s, 161, 203, 204, 206–10, 211, 237, 295–6 1931 General Muslim Conference, 214 1939 White Paper, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 254 ‘absorptive capacity’, 128–9, 188, 203–204, 208, 239 AHC, 220 Balfour Declaration, 138 Black Letter, 192, 204, 206 illegal immigration, 76, 129, 204, 207–208, 245, 259, 263 impact on Arabs, 183, 197, 204, 206, 235, 264 Jewish Agency, 203, 209 Jewish/Palestinian clashes and bloodshed, ix, 28–9, 30, 105, 126, 148, 185, 195, 203, 206, 208, 223, 243 Jews leaving Palestine, 39, 42, 158, 205 League of Nations Mandate, 121, 132, 204 limitation/restriction of, 112, 186, 203, 220, 234, 235, 236, 254 Nazism and, 218, 237 Palestine as Jewish national home and, 120, 159, 218, 296 Russian Jews, 4, 21, 22, 25–6, 152 suspension of, 120, 136, 177, 201, 203, 220, 236, 237, 255 World War II, 243 Zionism, 172, 296 see also aliyah Jewish Legion, 41–2 Jewish Question, x, xii, 3–7, 38, 249, 298, 300 anti-Semitism, x, 3, 6 assimilation, 5, 6–8 colonisation of Palestine as answer to, xiii, 7 conversion, 6 Herzl, Theodor, 1–2, 303 identity, 4–5 ‘return’ to Palestine, 13, 94, 105, 208, 227, 237 Zionism as answer to, 3, 38, 43, 291, 322n64 Jewish Reform Movement, 5, 19 Jewish refugees, x, 36, 147, 243, 247, 254, 255, 256, 274, 299 Jewish state in Palestine, 92, 96, 229, 241, 294 1939 White Paper, 238 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 271 Abdullah I, King of Transjordan, 268 Balfour Declaration, 96–7, 99 Biltmore Programme, 252, 253, 254 Churchill, Winston, 69 establishment of, 271 Jewish national home as precursor to, 262 King-Crane Commission Report, 112 Lloyd George, David, 75 Peel Report, 160, 168, 221, 226, 227, 241 Samuel, Herbert, 163 UN, x, 227 Weizmann, Chaim, 97 World War II, 243 Zionism, 189, 202, 224, 252, 253, 254, 289–90 see also partition of Palestine; statehood jihad, 216 JNF (Jewish National Fund), 24, 167, 198, 210 Johnson, Albert, 298 Jordan, 261, 271, 279 Palestinian refugees in, 276 Jordan River, 11, 129, 152, 155, 170, 326n3 JTO (Jewish Territorial Organisation), 12, 46 Judaism, 4–5, 6–7, 13, 15, 46, 52 Judea, 45–6 Kalischer, Zvi, 50 Kalvarisky, Haim, 31 Kenya, 11, 142, 165, 183, 231, 283, 298 Khalidi, Rashid, 304 Khalidi, Walid, 303–04 al-Khalidi, Yusuf Diya, 30 Khalidi, Yusuf Zia, 288 King, Henry, 110–13 see also King-Crane Commission Report King-Crane Commission Report (1919), 110–13, 114, 115, 142, 233, 242, 264, 297 Kipling, Rudyard, 153 Klein, Menachem, 170 Klier, John D., 20 Koestler, Arthur, 297–8, 302–303 Krämer, Gudrun, 39, 138, 179 La Guardia, Anton, 290 Labour Party (Britain), ix Labour Zionism, 173 language, 40, 41 see also Arabic; English; Hebrew; Yiddish Laqueur, Walter, 301 Laski, Neville, 248 Law, Andrew Bonar, 70 Lawrence, T.E., 71 League of Nations, 100, 240, 326n69, 330n86 Covenant, 107, 130–1, 211 Covenant, Article 22: 131, 132, 134, 135, 197, 263, 294 dominated by Britain and France, 130 failure of, 232–3 Mandate Commission, 133, 168 mandates for Arabic-speaking Ottoman provinces, 104, 107 see also British Mandate for Palestine; League of Nations Mandate League of Nations Mandate (1922), 130–5, 170, 188 Article 2: 132, 134, 199–200 Article 4: 121, 122, 123, 132, 133, 167, 168, 199–200 Article 6: 121, 132, 167, 199–200, 204 Article 11: 133, 143, 167, 199–200 Article 22: 133 Balfour Declaration and, 105, 115, 127, 132, 134, 135, 138, 146, 148, 170, 199 draft of, 121, 146 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 121, 132, 204 League of Nations Covenant/Mandate comparison, 131–2, 134, 135 Palestine as Jewish national home, 132, 133, 134 preamble, 134 written by the British, 130, 263 see also British Mandate for Palestine Lebanon, 117, 269, 276, 320n12 1975–90 Lebanese Civil War, 276 Israel-Lebanon border/Blue Line, 282 Legislative Council, 122, 135, 158, 164–5 1922 British White Paper, 128, 129, 164 absence of, 164, 165–6, 169, 180, 326–7n6, 327n15 allocations for seats, 165 Arab opposition to, 164, 165–6, 169, 177, 199 Levi, Primo, 49, 293 Levin, Judah, 48 Likud Party, 274 Lloyd George, David, x, 56, 70, 190, 300 Balfour Declaration, x–xi, 58, 73, 74–80, 93, 97, 100, 101, 105, 148 death, 331n15 Ireland, 124–5 memoirs, 75, 76, 321n27 Palestine and, 71, 74–5, 79, 80, 136, 140, 218, 242, 301 Paris Peace Conference, 78 World War I, 71, 72–3, 76 Zionism and, xii–xiii, 57, 71, 75–6, 77, 79, 80, 93, 136, 142, 296 Lucas, F.L., 233 Luke, Harry, Sir, 195 MacDonald, Malcolm, 257, 331n13 MacDonald, Ramsay, 189–90, 200–201, 213 Black Letter, 190–4, 204, 206, 213 McMahon, Henry, Sir: 1915 McMahon letter, 64–6, 69, 100, 262 MacMichael, Harold (British High Commissioner of Palestine), 229, 246, 257 MacMillan, Margaret, 78–9, 84, 96, 124 Maisky, Ivan, 249–51, 253 Marx, Heinrich, 6 Marx, Karl, 6, 283 Marxism, 275 Marxist Zionism, 25–6, 28 Masalha, Nur, 287 Mattar, Philip, 219 Meir, Golda, 268, 269 Mesopotamia, 12, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 68, 137, 139, 140, 186 see also Iraq messianism, 14, 15, 52, 147, 285, 316n27 Middle Ages, 46, 47 Middle East, 273 Britain, 68, 70, 72, 234 France, 68, 139 Milner, Alfred, Lord, 93 Mizrahim/Mizrahi Jews, 21 Money, Major-General, 109 Monroe, Elizabeth, 101 Montagu, Edwin, xi, 40, 41, 74, 88, 90, 254, 274 1917 Montagu Memorandum, 57, 88–92 assimilation, 88–9 Balfour Declaration, 74, 88–91, 92 National Insurance Bill, 322n64 Zionism, 90, 299 Montgomery, Bernard, General, 228, 229 Morris, Benny, 26, 294 Morris, Harold, Sir, 330n82 Moses, 43, 51, 155, 318n15 Mosley, Oswald, 48 Mossessohn, Nehemia, 81 Motzkin, Leo, 287 Moyne, Lord, 246 mukhtars (village headmen), 157, 327n15 Mussolini, Benito, 232 al-Nashashibi, Raghib, 175–6, 177, 178, 212, 213, 217 AHC, 219 Nashashibi dynasty, 175, 177, 209, 218, 268 Nassar, Najib, 31 Nasser, Gamal Abdel, General, 272, 332n9 nation/nationhood, 10, 40 Jewish nationhood, 40–4, 53, 88, 92, 134, 149, 319n41 national identity, 32, 283 ‘nationalisation’ of the Jews, 43 Palestinian nationhood, 32 nationalism, 38, 288–90 Arab nationalism, 29–30, 31, 59, 83, 121, 152, 166, 169, 180, 211, 223, 262 colonialism and, 289–90, 301 Jewish nationalism, 19, 223 Palestinian nationalism, 33, 210, 211, 214, 265, 269, 289 secular nationalism, 9 Zionism as Jewish national movement, 289, 290 see also self-determination Nazi Germany, 203, 207, 295–6, 299 1938 Kristallnacht, 295 Jews in, 237, 238, 295–6 Nazi persecution, 211, 218 Nuremberg Laws, 218 state-sponsored anti-Semitism, 161, 247, 296 see also Germany; Hitler, Adolf; Nazism Nazism, xii, 47, 148, 162 extermination of Jews, 245, 252 Jewish immigration to Palestine, 218, 237 see also Hitler, Adolf; Nazi Germany Netanyahu, Benjamin, 277 Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia, 35 Nietzsche, Friedrich W., 285 nimbyism, 240, 298–300 1939 British White Paper, 237 Balfour Declaration, xi, 74, 86–8 Britain, 141, 254, 298, 300, 334n10 Evian Conference, 299 Peel Report, 226–7, 237 UNSCOP, 264 USA, 207, 299 Nixon, Richard, 273 Nordau, Max, 27 Northern Ireland, 124, 330n85 Occupied Territories, 278, 280, 282 OETA (Occupied Enemy Territory Administration), 109, 113, 116–17, 125, 138, 182 Ormsby-Gore, William, 93, 146 Orthodox Jews, 19, 39, 167 Oslo Accords (1993), 277, 278 Ottoman Empire, 13, 40, 58 1327 Press Law, 156 1858 Land Code, 24, 327–8n21 1916 Arab Revolt, 65, 66, 71 Arab/Jew co-existence, 47 Britain and, 61–2, 64, 71, 72 Herzl, Theodor, 34–5 Palestine and, 24–5, 26, 29, 30, 32, 58, 151–2 post-war partition of Ottoman lands, 64, 66–7, 103, 104, 110, 146 Tanzimat/Reorganisation, 151 Young Turks, 30, 31 Oz, Amos, 9, 41 PAE (Palestinian Arab Executive), 176–8, 183, 194, 199, 208 1929–1930 delegation to London, 211, 212, 212–13 1931 General Muslim Conference, 211, 213–14 demise of, 211 shortcomings, 177 Pakistan, 256, 260 Palestine, 45, 282 1920s, x, 159 1922, 150–1, 153–8 1930s, x, 161, 167 Arabs/Muslims and Christians as indigenous population of, xi, 12, 17–18, 23, 36–7, 39, 44, 49, 58–9, 89–90, 91, 116, 149, 151, 152, 262, 271, 295, 302–303 cultural clash, 29 economy, 154–5, 180–1, 244 education, 181, 209 health issues, 153, 157 independence of, 277 infiltration, 29, 34 internationalisation of the Palestine problem, 231 Islam, 151 national consciousness, 22, 28, 32–3 national identity, 32 Ottoman government and, 24–5, 26, 29, 30, 32, 58, 151–2 population, 39, 152–3, 155, 157, 206, 236, 280 the Promised Land, 52, 58 rights of Palestinians, xii, 72, 95, 96, 97, 100, 121, 132, 134, 169, 183, 196, 197, 289 Sykes-Picot Agreement, 67–8, 69 transfer/population transfer, 37, 137, 162, 186, 226, 251, 253, 285, 287–8 World War I, 32, 49, 58, 59, 83 World War II, 162, 243–6 Zionism and, 3, 10–13, 24, 40, 153, 314–15n8 see also the entries below related to Palestine; British mandate for Palestine; colonialism; Jewish immigration to Palestine; Jewish state in Palestine; partition of Palestine Palestine, territory of, 151, 156, 170, 282, 326n1 1922 British White Paper, 129 coasts, 154, 156 geography, 155 Syria and, 58–9, 65, 174, 214 Palestine Arab Party, 267 Palestine as Jewish national home, 10, 12, 101, 147, 159, 166, 223, 268, 297 1922 League of Nations Mandate, 132, 133, 134 1922 White Paper, 127, 130 1930 White Paper, 188, 189, 193, 194 1931 Black Letter, 191, 213 1939 White Paper, 235–6, 240, 255 Abdullah I, King of Transjordan, 268 alternatives to Palestine as Jewish homeland, 11, 12, 36, 248, 287, 295–6 Arab opposition to, 217, 223, 228, 240 Balfour Declaration, 72, 95, 189, 197 Biltmore Programme, 252 British support for, 57–8, 89, 105, 140, 146, 174, 177, 182, 198, 204, 217, 224, 235, 239, 297 Jewish immigration and, 120, 159, 218, 296 as precursor to a Jewish state, 262 ‘return’ to Palestine as Jewish national homeland, 40, 44, 46, 49, 53, 147, 271 ‘the shutting down’ of, 223 USA, 207 Weizmann, Chaim, 13, 82, 98, 158, 169 World War II, 244, 255, 296 Zionism, 249 Palestine National Congress, 176, 177 Palestinian Arab politics, 211–18, 240–1, 244 radicalisation of Arab politics, 216–17 weakness of, 217 Palestinian land, 33, 148 1858 Land Code, 24, 327–8n21 1920s, 159, 182–4, 186, 198 1929 violence and disturbances, 186, 209–10 1930 Hope-Simpson Report, 183, 186, 187 1930s, 161, 206–207, 209–10 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 271 absentee landlords, 24, 31, 182–3, 328n21 eviction of Arabs from, 24, 183, 186, 209, 210, 271, 278 exclusion of Arabs from, 26, 30, 200, 271 farming, 28 inter-communal antagonism, 210 Jewish Agency, 209 Jewish agricultural colonies, 155 Jewish national territory, 210 Jews/Palestinian clashes over, 29, 223 Jezreel valley, 183 JNF, 210 kibbutz movement, 28 partition proposal and, 225 tenant farmers, 24, 25, 209 uncultivated land, 25 Zionist land reserves, 198 Zionist purchase of, 24–6, 31, 35, 159, 174, 182, 209, 210, 225, 284 Palestinian National Authority, 277, 279 Palestinian refugees, 274, 276, 278 Palin, Philip, Major-General Sir: Palin Report, 114–16, 297 Pappé, Ilan, 93 Paris Peace Conference (1919), 75, 78, 88, 96, 110, 112, 113, 124, 146, 263 League of Nations Covenant, 130 Parthian Empire, 45, 318n20 partition of Palestine, 182, 244, 256, 294 1937 Peel Commission Partition Proposal, 160, 221, 223–6, 288, 302 1947 UN Partition of Palestine, 261, 263, 299 1949 Armistice lines, 261 AHC, 227–8 cantonisation/federalism, 225, 256 Jewish/Palestinian segregation, 180–2, 221, 279, 287, 294 Palestine as unitary state, 224, 234, 254, 260, 301 ‘two-state solution’, xiii, 227, 263, 271, 277, 280 Zionism, 227 see also Jewish state in Palestine; UNSCOP Passfield, Lord (Sidney Webb), 197–200 see also British White Paper (1930, Passfield White Paper) Peel, Robert, Sir, 222 Peel, William, Lord, 222 see also Peel Commission and Report Peel Commission and Report (1937), 158, 161, 166, 168, 207, 231, 233, 240, 295, 297 1936 Arab revolt, 221, 222, 233 Abdullah I, King of Transjordan, 268–9 Arab opposition to, 161, 221, 227–8 British Mandate, abdication, 222 historic significance of, 221 Jewish state in Palestine, 160, 168, 221, 226, 227, 241 members of the Commission, 222, 330n82 nimbyism, 226–7, 237 Partition Proposal, 160, 221, 223–6, 288, 302 population transfer, 226, 288, 330n86 Report extracts, 222–3 ‘two-state solution’, xiii, 271 UNSCOP, 227, 262, 263 PEF (Palestine Exploration Fund), 54 Peres, Shimon, 27, 50, 52 persecution, 5, 35, 40, 43, 209, 295, 298 ghettoisation, 46 Nazi persecution, 211, 218 Zionism and, 46–7, 52, 108 Persian Gulf, 62, 66, 68 PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), 275, 276 Picot, François Georges-, 66 see also Sykes-Picot Agreement Pinsker, Leo, 7, 15, 28, 42, 315n15 PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation), 275–7 Black September, 276 IDF, 276 Palestinian National Covenant, 275 ‘two-state solution’, 277 UN observer status, 276 Plumer, Herbert, Field Marshal (British High Commissioner of Palestine), 196 Poale Zion (Workers of Zion), 25–6 pogrom, 38, 46, 47, 87, 107, 252, 255 Russia, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12, 35, 46, 47, 294 see also anti-Semitism; violence Poland, 4, 248, 251, 255 anti-Semitism, 161, 247 Jewish Question, x Jews in, x, 43, 207 Pollock, James, Captain, 117 al-Qassam, Izz ad-din, 215–16, 329n74 death, 216, 218 jihad, 216 Rabbinical Council, 155 Rabin, Yitzhak, 277 race, 41, 83, 87, 132, 185, 248 Jewish race, 61 rationalism, 5 Reagan, Ronald, 280 regeneration, 13, 14, 22, 27–8, 144, 205, 286 Revisionist Party, 164, 167, 172, 173, 185, 245 return ‘return’ to Palestine as answer to the Jewish Question, 13, 94, 105, 208, 227, 237 ‘return’ to Palestine as Jewish national homeland, 40, 44, 46, 49, 53, 94, 147, 271 ‘right of return’, 271, 280, 319n42 Rogan, Eugene, 64–5 Roman Empire, 45 Romans, 44, 45, 49, 53, 315n8 Roosevelt, Franklin, 247, 253 Rose, Norman, 39, 47, 193, 285 Rothschild, Edmond de, Baron, 24, 118, 144 Rothschild, Nathan, 2nd Baronet and Lord, 72, 76, 81, 83, 95, 96, 190 Rumbold, Horace, Sir, 330n82 Ruppin, Arthur, 25 Russia, 35, 70 Jewish Question, x, 4 Jews in, x, 4, 20, 42, 57, 73–4 Jews’ conversion to Christianity, 6 Pale of Settlement, 4, 8–9, 20, 47 pogrom, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12, 35, 46, 47, 294 see also USSR Rutenberg, Pinhas, 143 1921 Rutenberg affair, 143–4 Said, Edward, 98–9, 284, 285, 294, 302 al-Sakakini, Khalil, 30 Samaria, 45 Samuel, Herbert, Sir, 59, 60, 75, 80, 95, 115–16, 150, 303 1915 ‘The Future of Palestine’, 59–61, 63, 69 1922 British White Paper, 127 assimilation, 162 Balfour Declaration, 120–1 as British High Commissioner of Palestine, 117, 120, 122, 126, 150, 162–9, 170, 175, 179, 182, 196 gradualism, 163 Peel Report, 226 Zionism, 162, 196 see also ‘Handbook of Palestine’ San Remo Conference (1920), 103, 116, 146, 147, 162 Sand, Shlomo, 42, 44, 45, 46, 50, 318n21 Schneer, Jonathan, 69, 83, 91 Scott, C.P., 75, 77, 83, 326n64 secularism/secularisation, 5, 10, 14, 43 secular nationalism, 9 Zionism, 14, 19, 39, 40, 50, 52, 55, 149 self-determination, 43, 79, 106, 107, 260, 263 Arab self-determination, 131–2, 140 Balfour Declaration, 77, 105, 110, 115, 263 Zionism, 14, 32, 43, 52, 77, 105, 147, 285 see also nationalism Sephardi Jews, 21–2, 23, 41, 155 Seychelles, 267, 330–1n93 Shaftesbury, Lord, 54, 88, 92–3 Shamir, Yitzhak, 246 Sharon, Ariel, 278, 279 Shavit, Ari, 10, 17, 47, 141, 144 Shaw, Walter, Sir, 186, 187, 197, 202, 297 Shertok, Moshe, 229–30 Shlaim, Avi, 32, 173, 288–9, 318n6 Shuckburgh, John, Sir, 122, 123, 127, 139 Simms, William Gilmore, 288 Sinai, 11, 71, 272, 273, 274 SMC (Supreme Muslim Council), 178–80, 213, 215 Jewish Agency/SMC comparison, 179–80 Smuts, Jan, 93 socialism/socialist Zionism, 25, 26, 28, 31, 39, 48, 180, 181, 284, 286 inter-communal socialism, 246 Sokolow, Nahum, 78, 96, 146 South America, 23, 237 sovereignty, 88, 106, 124, 275, 283 Jewish sovereignty, 1, 10, 29, 34 Stalin, Joseph, 264, 293 Stanislawski, Michael, 73 statehood, 15, 40, 44, 52, 173, 294 Palestinian statehood, 269, 280 Zionism and, 294 see also Jewish state in Palestine Stein, Kenneth, 25, 163, 210 Stern, Avraham, 245 Stern Gang, 245–6, 332n4 Storrs, Ronald, 175 Suez Canal, 61, 63, 69, 77, 82, 83, 94, 139, 140, 256 1956 Suez Crisis, 272, 332n9 Sykes, Mark, Sir, 66, 87, 93, 95, 109 anti-Semitism, 87 Zionism, 140 see also Sykes-Picot Agreement Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916), 64, 66–8, 87, 107 Palestine, 67–8, 69, 140 partition plan, 66–7, 320n12 synagogue, 47, 184, 289 Syria, 63, 218 Greater Syria, 58, 65, 69, 174, 179, 214, 320n8 Palestine and, 58–9, 65, 174, 179, 214 Syrkin, Nahman, 287 Tel Aviv, 144, 184, 261, 270, 282 population, 207 as separate ‘Jewish’ port, 221 as separate municipality, 182 settlement programme, 274 territorialism, 12, 287 terrorism, 220, 229, 255, 265, 274, 276, 277 suicide bombing, 278–9 see also Haganah; Hamas; Irgun militia; PLO; Stern Gang The Times (newspaper), 72, 92, 96 Tolstoy, Leo, 302 Torah, 19 trade union issues 181 see also Histadrut Transjordan, 170, 186, 197, 220, 221, 266, 268 Truman, Harry, 256, 264 Turkey, 136–7, 140, 330n86 UN (United Nations), xiii, 257, 258, 259–60, 280 Jewish state in Palestine, x, 227 ‘Palestine’, observer status, 278 PLO, observer status, 276 Resolution 242, 275, 277 UN General Assembly’s vote on partition proposals, 265, 277 UNSCOP (UN Special Committee on Palestine), 260–4 1947 UN Partition of Palestine, 261, 263, 299 Arab case, 262–3 awarding 55% of Palestinian land to a Jewish state, x, 274 British Mandate for Palestine, 263–4 nimbyism, 264 Peel Report, 227, 262, 263 ‘two-state solution’, xiii, 227, 263, 271 USA (United States of America), 304, 332n9 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, 207, 237, 298–9, 329n62 as alternative to Palestine as Jewish homeland, 12, 23 annual quota of Jewish immigration, 237–8, 248, 254, 329n62 anti-Semitism and, xi, 86, 298 assimilation, 42, 48–9 Great Depression, 237 Israel and, 280 Jewish population in, 23, 237–8, 315n10 Jews in, xii, 23, 43, 57, 73–4, 107–108, 207, 295 Manifest Destiny, 286–7 ‘melting-pot’ metaphor, 5–6 nimbyism, 207, 299 Palestine as Jewish national home, 207 Protestantism and native Americans, 285–7 restrictions on immigration, 207, 237–8, 298–9 Statue of Liberty, 23 Zionism and, xi, 74, 86, 100, 145, 253, 285–7 Ussishkin, Menachem, 81, 288 USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), 256, 264, 273, 280, 300, 332n9 see also Russia Venizelos, Eleutherios, 78–80 Victor Emmanuel II, King of Italy, 35 Vienna (Austria), 1–2, 4 Vital, David, 6, 247 Viton, Albert, 208 Von Plehve, Vyacheslav Konstantinovich, 35, 88 Wasserstein, Bernard, 274 Wauchope, Arthur, General Sir (British High Commissioner of Palestine), 194, 196, 220 Weinstock, Nathan, 259, 314n5 Weizmann, Chaim, 20, 25, 36, 38, 52, 72–3, 78–83, 81, 147, 177, 182, 201, 285 1941 London meeting with Maisky, 247, 249–51 on Arab nationalism, 29–30 Arabs, disregard of, 141, 250–1 assimilation, 8–9, 49 Balfour Declaration, 36, 74, 75, 80–3, 90–1, 94, 96, 97, 98, 116, 117, 134, 321n43 Black Letter, 190 British Mandate for Palestine, 134, 146, 147, 149, 158 Deedes letter, answer to, 122–3 Jews as nation, 40, 42, 43 Palestine as Jewish national home, 13, 82, 98, 158, 169 Peel Report, 227 as President of World Zionist Organisation, 314n6 ‘transfer’/population transfer, 186, 251, 253 What is Zionism, 8, 12, 43 World War II, 246, 249–50 Zionism, 80, 82, 254, 289, 321n43 Zionist Commission, 145 West Bank, 261, 268, 270, 271, 275, 278, 282, 320n13 1967 Six Day War, 272, 273 Palestinian Arabs in, 280 Palestinian National Authority, 277 settlement programme, 274 West Bank Barrier, 279 Wilhelm II, German Emperor, 35 Wilson, Henry, Field Marshal Sir, 125 Wilson, Thomas Woodrow, 73, 77, 100, 130–1, 146, 326n69 Fourteen Points, 106–107, 131, 135 Wingate, Orde, 229 World War I, 41–2, 49, 57, 70–1 Allies, 76–7 Balfour Declaration, 73, 76–7, 83–4, 98, 101, 105, 148 Britain, 70–1, 72, 76–7, 87, 123, 139 Israel, origins of the state of, ix Palestine, 32, 49, 58, 59, 83 Zionism, 73, 83 World War II Axis powers, 244 British Mandate for Palestine, 234, 239, 254, 257 Haganah, 245 Irgun militia, 245, 246 Israel, origins of the state of, ix Jewish immigration to Palestine, 243 Jewish state in Palestine, 243 Palestine, 162, 243–6 Palestine as Jewish national home, 244, 255, 296 Zionism, 245–6, 252–3 see also Holocaust World Zionist Organisation, 23, 24, 34, 39, 122, 167, 314n6 Yiddish, 20, 41, 47, 316n36 yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine) 39, 119, 166, 167, 180, 221, 241, 252, 296, 327n15 1920s, 205 1947–1949 First Arab-Israeli War, 264–6 British administration and, 217 revenue from, 144 Zionist Commission and, 145 Young Turks, 30, 31, 40 Zangwill, Israel, 12, 46, 287 The Melting Pot, 12 Zionism, 13, 171–4, 257, 288, 297 aim of, 3, 14, 24, 55 alternatives to, 19, 21–2 anachronism, 47, 48 anti-Zionism, 22, 123, 169, 304, 318n6 arms and violence, 121, 147, 264, 284, 288, 297 assimilation and, 7–10 Balfour Declaration, xi, xiii, 95–6, 98, 99, 194, 251, 317n74 birth of modern Zionism, 1–3, 47, 314n5 British Mandate for Palestine, 115, 132, 133, 134, 135, 138, 140, 142–7, 149, 158, 161, 167, 173–4, 190, 194, 211, 217, 241, 254, 297–8 colonialism, 281, 283–7, 289–90 colonisation of Palestine, xiii, 3, 15, 16–18, 22, 23, 31, 171, 173, 193, 198, 211, 216, 289, 294, 295, 299 criticism of, 17, 19–20, 22, 30, 38, 90, 93, 254, 280, 286 different notions of, 13–18 diplomacy for Palestine, 33–7, 40 hybridity, 52 industrialisation of Palestine, 144 as ideology, 22, 37, 38, 40–53, 55, 130, 281, 288 as Jewish national movement, 289, 290 Jewish opposition to, 19–22 Jewish Question and, 3, 38, 43, 291, 322n64 lack of appeal to Jews, 39, 42–3, 48, 74 messianism, 14–15, 52 as movement, 22, 130, 281, 289 Political Zionism, 15, 16, 22, 38, 43, 46 secularism, 14, 19, 39, 40, 50, 52, 55, 149 self-determination, 14, 32, 43, 52, 77, 105, 147, 285 Spiritual/Cultural Zionism, 15–16, 286 the term, 314–15n8 transfer/population transfer, 37, 137, 186, 226, 251, 285, 287–8 World War I, 73, 83 World War II, 245–6, 252–3 see also Christian Zionism Zionist Commission, 108, 117, 119, 122, 126, 163, 324n21 criticism of, 144, 145–6 establishment of, 145 organisational structure, 167–8 see also Jewish Agency; Zionist Executive Zionist Congress, 27, 251 1st Zionist Congress (1897), 15, 34, 42, 251, 314n6 7th Zionist Congress (1905), 11 12th Zionist Congress (1921), 128 16th Zionist Congress (1929), 198 17th Zionist Congress (1931), 227 18th Zionist Congress (1933), 296 see also Biltmore Conference Zionist Executive, 167, 171 Zionist organisation, registering fee, 42–3 see also World Zionist Organisation

…