hub-and-spoke system

description: form of transport topology optimization in which traffic planners organize routes as a series of "spokes" that connect outlying points to a central "hub"

96 results

Virtual Competition

by

Ariel Ezrachi

and

Maurice E. Stucke

Published 30 Nov 2016

It is important to note how the algorithm-fueled hub and spoke differs from our first scenario—the Messenger—which considered the computer as a mere extension of the humans’ illegal agreement. In an algorithmdriven hub and spoke, the computer does not merely execute the orders of humans; rather, it is the competitors’ use of the same pricing algorithm that stabilizes prices and dampens competition. It is also important to distinguish between the traditional hub and spoke conspiracy, in which the immediate aim is horizontal collusion, and each vertical link is in furtherance of that aim, from an algorithm-driven hub and spoke. The latter may, of course, be the result of an intentional attempt to dampen competition, but it may also occur due to unintentional alignment and use of similar algorithms to monitor prices.

…

As messengers, algorithms are neither a negative nor positive force; rather, they are a technological extension of the human will. 6 Hub and Spoke H AVING CONSIDERED the “simple” Messenger scenario, we next consider instances in which computer algorithms are used as the central “hub” to coordinate competitors’ pricing or activities. While the competitors do not directly contact or communicate with each other, the overall impact of the practice is akin to horizontal collusion. Traditional Hub and Spoke Hub-and-Spoke conspiracies are not unique to the online environment or antitrust. After all, both cocaine and price-fi xing cartels may be facilitated by such arrangements.

…

Supreme Court noted, “an unlawful conspiracy may be and often is formed without simultaneous action or agreement on the part of the conspirators.”3 But to show a single hub-and-spoke conspiracy, rather than multiple independent conspiracies, there must be a rim: there must be some overall awareness of the conspiracy and that “each defendant knew or had reason to know of the scope of the conspiracy and . . . reason to believe that their own benefits were dependent upon the success 46 Hub and Spoke 47 of the entire venture.”4 In a hub-and-spoke price-fi xing conspiracy, the competitors who form the wheel’s spokes must be aware of the concerted effort to stabilize prices.

The Data Warehouse Toolkit: The Definitive Guide to Dimensional Modeling

by

Ralph Kimball

and

Margy Ross

Published 30 Jun 2013

So our concepts of dimensional modeling are often applied in this architecture, despite the complete disregard for some of our core tenets, such as focusing on atomic details, building by business process instead of department, and leveraging conformed dimensions for enterprise consistency and integration. Hub-and-Spoke Corporate Information Factory Inmon Architecture The hub-and-spoke Corporate Information Factory (CIF) approach is advocated by Bill Inmon and others in the industry. Figure 1.9 illustrates a simplified version of the CIF, focusing on the core elements and concepts that warrant discussion. Figure 1.9 Simplified illustration of the hub-and-spoke Corporate Information Factory architecture. With the CIF, data is extracted from the operational source systems and processed through an ETL system sometimes referred to as data acquisition.

…

See G/L (general ledger) ch7¶7 generic dimensions, abstract ch2¶249 geographic location dimension ch11¶52 G/L (general ledger) ch7¶7 chart of accounts ch7¶9 currencies, multiple ch7¶23 financial statements ch7¶34 fiscal calendar, multiple ch7¶31 hierarchies, drill down ch7¶33 journal entries ch7¶24 period close ch7¶15 periodic snapshot ch7¶8 year-to-date facts ch7¶21 GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) ch12¶40 goals of DW/BI ch1¶9 Google Analytics (GA) ch15¶57 governance business-driven ch4¶91 objectives ch4¶95 grain ch2¶18 accumulating snapshots ch2¶53 atomic grain data ch3¶25 budget fact table ch7¶40 conformed dimensions ch4¶81 declaration ch3¶24 retail sales case study ch3¶17, ch3¶23, ch3¶30, ch3¶96 dimensions, hierarchies and ch11¶19 fact tables ch1¶31, ch1¶34, ch1¶40, ch1¶41, ch1¶61 accumulating snapshot ch1¶40 periodic snapshot ch1¶40 transaction ch1¶40 periodic snapshots ch2¶50 single, facts and ch11¶17 transaction fact tables ch2¶47 granularity ch11¶15 GROUP BY clause ch1¶62 growth Lifecycle ch17¶19 market growth ch3¶202 H Hadoop, MapReduce/Hadoop ch21¶14 HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) ch14¶9 HDFS (Hadoop distributed file system) ch21¶12 headcount periodic snapshot ch9¶23 header/line fact tables ch2¶185 header/line patterns ch6¶51, ch6¶65 healthcare case study ch14¶3 billing ch14¶11 claims ch14¶11 date dimension ch14¶23 diagnosis dimension ch14¶24 EMRs (electronic medical records) ch14¶7 HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) ch14¶10 HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) ch14¶9 ICD (International Classification of Diseases) ch14¶10 images ch14¶44 inventory ch14¶45 measure type dimension ch14¶38 payments ch14¶11 retroactive changes ch14¶49 subtypes ch14¶32 supertypes ch14¶32 text comments ch14¶43 heterogeneous products ch10¶43 hierarchies accounting case study ch7¶74 customer dimension ch6¶24, ch8¶54 dimension granularity ch11¶19 dimension tables, multiple ch3¶77 drill down, ETL development ch20¶15 employees ch9¶37 ETL systems ch19¶113 fixed-depth positional hierarchies ch2¶160 G/L (general ledger), drill down ch7¶32 management, drilling up/down ch9¶45 many-to-one ch3¶62 matrix columns ch4¶204 multiple ch2¶84 nodes ch7¶58 ragged/variable depth ch2¶166 slightly ragged/variable depth ch2¶163 trees ch7¶58 high performance backup ch19¶302 HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) ch14¶8 historic fact tables extracts ch20¶51 statistics audit ch20¶53 historic load data, ETL development ch20¶25 dimension table population ch20¶26 holiday indicator ch3¶54 hot response cache ch8¶201 hot swappable dimensions ch2¶246, ch10¶52 household dimension ch10¶17 HR (human resources) case study ch9¶1 bus matrix ch9¶26 employee profiles ch9¶3 dimension change reasons ch9¶17 effective time ch9¶12 expiration ch9¶12, ch9¶13 fact events ch9¶23 type 2 attributes ch9¶23 hierarchies management ch9¶1, ch9¶3 recursive ch9¶37 managers key as foreign key ch3¶93 embedded ch9¶41 packaged analytic solutions ch9¶28 packaged data models ch9¶28 periodic snapshots, headcount ch9¶23 skill keywords ch9¶54, ch9¶59, ch9¶61 bridge ch9¶65, ch9¶66 text string ch9¶68 survey questionnaire ch9¶67, ch9¶74 text comments ch9¶74 HTTP (Hyper Text Transfer Protocol) ch15¶16 hub-and-spoke CIF architecture ch1¶107, ch1¶110 hub-and-spoke Kimball hybrid architecture ch1¶112 human resources management case study. See HR (human resources) ch9¶1 hybrid hub-and-spoke Kimball architecture ch1¶112 hybrid techniques, SCDs ch2¶150 SCD type 5 (add mini-dimension and type 1 outrigger) ch2¶150, ch5¶73 SCD type 6 (add type 1 attributes to type 2 dimension) ch2¶153, ch5¶76, ch5¶80, ch5¶81 SCD type 7 (dual type 1 and type 2 dimension) ch2¶156, ch5¶82, ch5¶87 hyperstructured data ch21¶9 I ICD (International Classification of Diseases) ch14¶9 identical conformed dimensions ch4¶80 images, healthcare case study ch14¶44 impact reports ch10¶24 incremental processing, ETL system development ch20¶77 changed dimension rows ch20¶81 dimension attribute changes ch20¶89 dimension table extracts ch20¶78 fact tables ch20¶92 new dimension rows ch20¶81 in-database analytics, big data and ch21¶45 independent data mart architecture ch1¶103, ch1¶104, ch1¶105, ch1¶106 indicators abnormal, fact tables ch8¶97 as textual attributes ch2¶87 dimension tables ch3¶55 junk dimensions and ch6¶42 satisfaction, fact tables ch8¶93 Inmon, Bill ch1¶107 insurance case study ch16¶2 accidents, factless fact tables ch2¶56 accumulating snapshot, complementary policy ch16¶37 bus matrix ch16¶56, ch16¶57 detailed implementation ch16¶58 claim transactions ch16¶60, ch16¶62, ch16¶65, ch16¶69, ch16¶73, ch16¶74 claim accumulating snapshot ch16¶73 junk dimensions and ch16¶61 periodic snapshot ch16¶42, ch16¶82 timespan accumulating snapshot ch16¶78 conformed dimensions ch16¶42 conformed facts ch16¶43 dimensions ch16¶20 audit ch16¶21 degenerate ch16¶30 low cardinality ch16¶31 mini-dimensions ch16¶26 multivalued ch16¶28 SCDs (slowly changing dimensions) ch16¶21 NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) ch16¶29 numeric attributes ch16¶29 pay-in-advance facts ch16¶44 periodic snapshot ch16¶39 policy transactions ch16¶16, ch16¶33 premiums, periodic snapshot ch16¶40 SIC (Standard Industry Classification) ch16¶29 supertype/subtype products ch16¶36, ch16¶47 value chain ch16¶10 integer keys ch3¶116 sequential surrogate keys ch3¶125 integration conformed dimensions ch4¶76 customer data ch8¶100, ch8¶101, ch8¶105 customer dimension conformity ch8¶105 single customer dimension ch8¶101 dimensional modeling myths ch1¶124 value chain ch4¶48 international names/addresses, customer dimension ch8¶26 interviews, Lifecycle business requirements ch17¶48 data-centric ch17¶55 inventory case study ch4¶6 accumulating snapshot ch4¶30 fact tables, enhanced ch4¶18 periodic snapshot ch4¶6 semi-additive facts ch4¶13 transactions ch4¶23 inventory, healthcare case study ch14¶48 invoice transaction fact table ch6¶67 J job scheduler, ETL systems ch19¶166 job scheduling, ETL operation and automation ch20¶116 joins dimension-to-dimension table joins ch2¶213 fact tables, avoiding ch8¶110 many-to-one-to-many ch8¶111 multipass SQL to avoid fact-to-fact joins ch2¶53 journal entries (G/L) ch7¶24 junk dimensions ch2¶99, ch6¶42 airline case study ch12¶31 ETL systems ch19¶116 insurance case study ch16¶62 order management case study ch6¶42 justification for program/project planning ch17¶21 K keys dimension surrogate keys ch2¶69 durable ch2¶72 foreign ch3¶93, ch10¶38 managers key (HR) ch9¶46 natural keys ch2¶72 supernatural keys ch2¶72 smart keys ch3¶127 subtype tables ch10¶47 supernatural ch2¶72 supertype tables ch10¶47 surrogate ch2¶173, ch3¶116, ch3¶119, ch3¶220, ch3¶120, ch11¶29 assigning ch2¶125 degenerate dimensions ch2¶78 ETL system ch19¶8, ch19¶11, ch19¶13, ch19¶27, ch19¶31, ch19¶33, ch19¶34 fact tables ch1¶31, ch1¶34, ch1¶40 generator ch19¶110 lookup pipelining ch20¶63 keywords, skill keywords ch9¶54 bridge ch9¶59 text string ch9¶61 Kimball Dimensional Modeling Techniques.

…

Index Symbols 3NF (third normal form) models ch1¶21 ERDs (entity-relationship diagrams) ch1¶22 normalized 3NF structures ch1¶23 4-step dimensional design process ch2¶11, ch3¶5 A abnormal scenario indicators ch8¶97 abstract generic dimensions ch2¶249 geographic location dimension ch11¶52 accessibility goals ch1¶303 accidents (insurance case study), factless fact tables ch16¶77 accounting case study ch7¶3 budgeting ch7¶36 fact tables, consolidated ch7¶80 G/L (general ledger) ch7¶7 chart of accounts ch7¶9 currencies ch7¶20 financial statements ch7¶34 fiscal calendar, multiple ch7¶31 hierarchies ch7¶59 journal entries ch7¶24 period close ch7¶16 periodic snapshot ch7¶9 year-to-date facts ch7¶22 hierarchies fixed depth ch7¶53 modifying, ragged ch7¶70 ragged, alternative modeling approaches ch7¶74 ragged, bridge table approach ch7¶78 ragged, modifying ch7¶70 ragged, shared ownership ch7¶67 ragged, time varying ch7¶68 ragged, variable depth ch7¶58 variable depth ch7¶62 OLAP and ch7¶86 accumulating grain fact tables ch1¶40 accumulating snapshots ch2¶53, ch4¶30, ch6¶89 claims (insurance case study) ch16¶65 complex workflows ch16¶101 timespan accumulating snapshot ch16¶78 ETL systems ch19¶132 fact tables ch4¶41, ch13¶201 complementary fact tables ch4¶33 milestones ch4¶42 OLAP cubes ch4¶45 updates ch4¶44 healthcare case study ch14¶16 policy (insurance case study) ch16¶40 type 2 dimensions and ch6¶96 activity-based costing measures ch6¶60 additive facts ch1¶35, ch2¶38 add mini dimension and type 1 outrigger (SCD type 5) ch2¶150 add mini-dimension (SCD type 4) ch2¶147 multiple ch5¶62, ch5¶64, ch5¶65, ch5¶66, ch5¶68, ch5¶69 add new attribute (SCD type 3) ch2¶144, ch5¶51, ch5¶62 multiple ch5¶61 add new row (SCD type 2) ch2¶140, ch5¶36 effective date ch5¶44 expiration date ch5¶44 type 1 in same dimension ch5¶50 addresses ASCII ch8¶26 CRM and, customer dimension ch8¶20 Unicode ch8¶27 add type 1 attributes to type 2 dimension (SCD type 6) ch2¶153 admissions events (education case study) ch13¶17 aggregate builder, ETL system ch19¶157 aggregated facts as attributes ch2¶228 CRM and, customer dimension ch8¶35 aggregate fact tables ch2¶59 clickstream data ch15¶54 aggregate OLAP cubes ch1¶27, ch2¶59 aggregate tables, ETL system development ch20¶114 agile development ch1¶132 conformed dimensions and ch4¶96 airline case study ch12¶2 bus matrix ch12¶4 calendars as outriggers ch12¶37 class of service flown dimension ch12¶30 destination airport dimension ch12¶33 fact tables, granularity ch12¶7 origin dimension ch12¶33 passenger dimension ch12¶14 sales channel dimension ch12¶18 segments, linking to trips ch12¶20 time zones, multiple ch12¶42 aliasing ch6¶14 allocated facts ch2¶188 allocating ch6¶59 allocations, profit and loss fact tables ch2¶191 ALTER TABLE command ch1¶59 analytics big data management ch21¶19 GA (Google Analytics) ch15¶57 in-database, big data and ch21¶45 analytic solutions, packaged ch9¶28 AND queries, skill keywords bridge ch9¶59 architecture big data best practices backflow ch21¶35 boundary crashes ch21¶38 compute resources ch21¶44 data highway planning ch21¶28 data quality planning ch21¶33 data value ch21¶34 ecosystems ch21¶32 fact extractor ch21¶31 in-database analytics ch21¶45 performance improvements ch21¶40 prototypes ch21¶23 streaming data ch21¶37 DW/BI alternatives ch1¶100 enterprise data warehouse bus architecture ch1¶77, ch4¶52 hub-and-spoke CIF architecture ch1¶107, ch1¶110 hybrid hub-and-spoke Kimball architecture ch1¶112 independent data mart architecture ch1¶103, ch1¶104, ch1¶105, ch1¶106 MapReduce/Hadoop ch21¶14 RDBMS, extension ch21¶8 real-time processing ch20¶127 archiving ch19¶23, ch19¶174 artificial keys ch3¶116 ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) ch8¶26 atomic grain data ch1¶59, ch3¶25 attributes aggregated facts as ch2¶228 bridge tables, CRM and ch8¶64 changes ch20¶89 detailed dimension model ch18¶40 expiration ch9¶11 flags ch2¶87 indicators ch2¶87 null ch2¶90, ch3¶95 numeric values as ch2¶179 pathstring, ragged/variable depth hierarchies ch2¶169 product dimensions ch4¶82 SCD type 3 (add new attribute) ch5¶51 multiple ch5¶61 audit columns, CDC (change data capture) ch19¶43 audit dimensions ch2¶252, ch6¶85 assembler ch19¶78 insurance case study ch16¶32 key assignment ch20¶70 automation, ETL system development errors ch20¶120 exceptions ch20¶120 job scheduling ch20¶116 B backflow, big data and ch21¶35 backups ch19¶305 backup system, ETL systems ch19¶171 archiving ch19¶174 compliance manager ch19¶26 dependency ch19¶195 high performance ch19¶302 lights-out operations ch19¶304 lineage ch19¶195 metadata repository ch19¶215 parallelizing/pipelining system ch19¶22 problem escalation system ch19¶197 recovery and restart system ch19¶179 retrieval ch19¶174 security system ch19¶204, ch19¶205 simple administration ch19¶303 sorting system ch19¶192 version control system ch19¶185 version migration system ch19¶187 workflow monitor ch19¶189 banking case study ch10¶4 bus matrix ch10¶4 dimensions household ch10¶20 mini-dimensions ch10¶28, ch10¶33 multivalued, weighting ch10¶21 too few ch10¶7 facts, value banding ch10¶39 heterogeneous products ch10¶43 hot swappable dimensions ch10¶52 user perspective ch10¶45 behavior customers, CRM and ch8¶70 sequential, step dimension and ch8¶78 study groups ch2¶225, ch8¶71 behavior tags facts ch8¶43 time series ch2¶222, ch8¶38 BI application design/development (Lifecycle) ch17¶98, ch17¶211 BI applications ch1¶80 BI (business intelligence) delivery interfaces ch19¶27 big data architecture best practices backflow ch21¶35 boundary crashes ch21¶38 compute resources ch21¶44 data highway planning ch21¶28 data quality planning ch21¶33 data value ch21¶34 ecosystems ch21¶32 fact extractor ch21¶12 in-database analytics ch21¶45 performance improvements ch21¶40 prototypes ch21¶23 streaming data ch21¶37 data governance best practices ch21¶60 dimensionalizing and ch21¶47 privacy ch21¶62 data modeling best practices data structure declaration ch21¶56 data virtualization ch21¶60 dimension anchoring ch21¶52 integrating sources and confined dimensions ch21¶48 name-value pairs ch21¶58 SCDs (slowly changing dimensions) ch21¶55 structured/unstructured data integration ch21¶54 thinking dimensionally ch21¶49 management best practices analytics and ch21¶19 legacy environments and ch21¶20 sandbox results and ch21¶23 sunsetting and ch21¶26 overview ch21¶3 blobs ch21¶10 boundary crashes, big data and ch21¶38 bridge tables customer contacts, CRM and ch8¶68 mini-dimensions ch10¶33 multivalued CRM and ch8¶17, ch8¶20, ch8¶26, ch8¶34, ch8¶35, ch8¶36, ch8¶37, ch8¶50, ch8¶54 time varying ch2¶219 multivalued dimensions ch2¶216, ch19¶144 ragged hierarchies and ch7¶79 ragged/variable depth hierarchies ch2¶166 sparse attributes, CRM and ch8¶67 bubble chart, dimension modeling and ch18¶31 budget fact table ch7¶39 budgeting process ch7¶36 bus architecture ch4¶53 enterprise data warehouse bus architecture ch2¶121 business analyst ch17¶201 Business Dimensional Lifecycle ch17¶5 business-driven governance ch4¶91 business driver ch17¶202 business initiatives ch3¶7 business lead ch17¶203 business motivation, Lifecycle planning ch17¶19 business processes characteristics ch3¶5 dimensional modeling ch2¶15, ch11¶13 retail sales case study ch3¶21 value chain ch4¶4 business representatives, dimensional modeling ch18¶12 business requirements dimensional modeling ch18¶17 Lifecycle ch17¶9, ch17¶42 documentation ch17¶57 forum selection ch17¶32, ch17¶38 interviews ch17¶48, ch17¶72 launch ch17¶47 prioritization ch17¶60 representatives ch17¶42 team ch17¶39 business rule screens ch19¶69 business sponsor ch17¶18 Lifecycle planning ch17¶18 business users ch17¶204 perspectives ch10¶45 bus matrix accounting ch7¶3 airline ch12¶4 banking ch10¶4 detailed implementation bus matrix ch2¶127 dimensional modeling and ch18¶48 enterprise data warehouse bus matrix ch2¶124 healthcare case study ch14¶3 HR (human resources) ch9¶28 insurance ch16¶2, ch16¶10 detailed implementation ch16¶57 inventory ch4¶7 opportunity/stakeholder matrix ch4¶69 order management ch6¶6 procurement ch5¶4, ch5¶18 telecommunications ch11¶4 university ch13¶4 web retailers, clickstream integration ch15¶63 C calculation lag ch6¶97 calendar date dimensions ch2¶93 calendars, country-specific as outriggers ch12¶37 cannibalization ch3¶101 cargo shipper schema ch12¶27 case studies accounting ch7¶3 budgeting ch7¶38 consolidated fact tables ch7¶83, ch7¶89 G/L (general ledger) ch7¶8, ch7¶8, ch7¶9, ch7¶9, ch7¶10, ch7¶16, ch7¶22 hierarchies ch7¶59, ch7¶60 OLAP and ch7¶86 airline ch12¶2 calendars as outriggers ch12¶43 class of service flown dimension ch12¶35 destination airport dimension ch12¶38 fact table granularity ch12¶7 origin dimension ch12¶38 passenger dimension ch12¶16 sales channel dimension ch12¶21 time zones, multiple ch12¶40 CRM (customer relationship management) analytic ch8¶11 bridge tables ch8¶59 complex customer behavior ch8¶74 customer data integration ch8¶106, ch8¶107, ch8¶112 customer dimension and ch8¶17 fact tables, abnormal scenario indicators ch8¶97 fact tables, satisfaction indicators ch8¶93 fact tables, timespan ch8¶85 low latency data ch8¶122 operational ch8¶11 step dimension, sequential behavior ch8¶81 education ch13¶4, ch13¶17 accumulating snapshot fact table ch13¶6, ch13¶41 additional uses ch13¶38 admissions events ch13¶17 applicant pipeline ch13¶7 attendance ch13¶37 change tracking ch13¶20 course registrations ch13¶18, ch13¶28 facility use ch13¶33 instructors, multiple ch13¶29 metrics, artificial count ch13¶22 research grant proposal ch13¶14 student dimensions ch13¶20 term dimensions ch13¶19 electronic commerce clickstream data ch15¶1, ch15¶4, ch15¶7, ch15¶9, ch15¶11, ch15¶14, ch15¶19, ch15¶58, ch15¶60 profitability, sales transactions and ch15¶65 financial services ch10¶2, ch10¶4, ch10¶21 dimensions, household ch10¶17 dimensions, too few ch10¶6 healthcare ch14¶3, ch14¶6 billing ch14¶12 claims ch14¶12 date dimension ch14¶23 diagnosis dimension ch14¶26 EMRs (electronic medical records) ch14¶7 HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System) ch14¶10 HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) ch14¶9 ICD (International Classification of Diseases) ch14¶10 images ch14¶49 inventory ch14¶50 measure type dimension ch14¶38, ch14¶40 payments ch14¶12 retroactive changes ch14¶49 subtypes ch14¶35 supertypes ch14¶35 text comments ch14¶48 HR (Human Resources Management) bus matrix ch9¶28 employee hierarchies ch9¶37 employee profiles ch9¶3, ch9¶12, ch9¶17, ch9¶23 hierarchies ch9¶37, ch9¶45 managers key ch9¶41, ch9¶46 packaged data models ch9¶28, ch9¶34, ch9¶36 periodic snapshots ch2¶22, ch4¶7 skill keywords ch9¶54, ch9¶56, ch9¶58, ch9¶59, ch9¶61, ch9¶66 survey questionnaire ch9¶67, ch9¶74 insurance ch16¶2, ch16¶4, ch16¶7 accident events factless fact table ch16¶76 accumulating snapshot ch16¶37, ch16¶65 bus matrix ch16¶14, ch16¶61 claim transactions ch16¶67, ch16¶70, ch16¶73, ch16¶78 conformed dimensions ch16¶45 conformed facts ch16¶46 degenerate dimension ch16¶30 dimensions ch16¶31, ch16¶32, ch16¶49 dimensions, audit ch16¶32 dimensions, low cardinality ch16¶31 dimensions, multivalued ch16¶27 junk dimensions ch16¶61 mini-dimensions ch16¶26 multivalued dimensions ch16¶48 NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) ch16¶29 numeric attributes ch16¶30 pay-in-advance facts ch16¶47 periodic snapshot ch16¶42 policy transaction fact table ch16¶33 policy transactions ch16¶17, ch16¶34 premiums, periodic snapshot ch16¶43 SCDs (slowly changing dimensions) ch16¶21 SIC (Standard Industry Classification) ch16¶29 supertype/subtype products ch16¶39, ch16¶51 timespan accumulating snapshot ch16¶69 value chain ch16¶10 inventory accumulating snapshot ch4¶31 fact tables ch4¶16, ch4¶37, ch4¶41 periodic snapshot ch4¶7 semi-additive facts ch4¶13, ch4¶16, ch4¶17 transactions ch4¶25, ch4¶38, ch4¶40 order management ch6¶6 accumulating snapshots ch4¶31, ch4¶45, ch4¶48 audit dimension ch6¶92 customer dimension ch6¶26, ch6¶28, ch6¶32 deal dimension ch6¶40 header/line pattern ch6¶49 header/line patterns ch6¶49, ch6¶51 invoice transactions ch6¶75 junk dimensions ch6¶46 lag calculations ch6¶97 multiple currencies ch6¶52 product dimension ch6¶20, ch6¶21, ch6¶275, ch6¶22, ch6¶206 profit and loss facts ch6¶87 transaction granularity ch6¶84 transactions ch6¶11, ch6¶47 units of measure, multiple ch6¶99 procurement ch5¶4, ch5¶7 bus matrix ch5¶7 complementary procurement snapshot fact table ch5¶18 transactions ch5¶7, ch5¶9 retail sales ch3¶16 business process selection ch3¶23 dimensions, selecting ch3¶32 facts ch3¶15, ch3¶35, ch3¶38, ch3¶41, ch3¶43, ch3¶144 facts, derived ch3¶38 facts, non-additive ch3¶41 fact tables ch3¶43 frequent shopper program ch3¶108 grain declaration ch3¶25 POS schema ch3¶103 retail schema extensibility ch3¶107 telecommunications ch11¶4 causal dimension ch3¶85, ch10¶200 CDC (change data capture) ETL system ch19¶8 audit columns ch19¶43 diff compare ch19¶45 log scraping ch19¶46 message queue monitoring ch19¶47 timed extracts ch19¶44 centipede fact tables ch2¶176, ch3¶144 change reasons ch9¶15 change tracking ch5¶19, ch5¶23 education case study ch13¶20 HR (human resources) case study, embedded manager's key ch9¶41 SCDs ch5¶21 chart of accounts (G/L) ch7¶9 uniform chart of accounts ch7¶13 checkpoints, data quality ch20¶95 CIF (Corporate Information Factory) ch1¶107, ch1¶110 CIO (chief information officer) ch16¶8 claim transactions (insurance case study) ch16¶60 claim accumulating snapshot ch16¶65 junk dimensions and ch16¶62 periodic snapshot ch16¶73 timespan accumulating snapshot ch16¶69 class of service flown dimension (airline case study) ch12¶30 cleaning and conforming, ETL systems ch19¶201 audit dimension assembler ch19¶78 conforming system ch19¶84 data cleansing system ch19¶62 quality event responses ch19¶57 quality screens ch19¶52 data quality improvement ch19¶58 deduplication system ch19¶80 error event schema ch19¶71 clickstream data ch15¶1 dimensional models ch15¶19, ch15¶26 aggregate fact tables ch15¶54 customer ch15¶31, ch15¶33 date ch15¶31, ch15¶33 event dimension ch15¶26 GA (Google Analytics) ch15¶57 page dimension ch15¶21 page event fact table ch15¶41 referral dimension ch15¶29 session dimension ch15¶27 session fact table ch15¶30 step dimension ch15¶58 time ch15¶32, ch15¶34 session IDs ch15¶15 visitor identification ch15¶18 visitor origins ch15¶11 web retailer bus matrix integration ch15¶63 collaborative design workshops ch2¶8 column screens ch19¶67 comments, survey questionnaire (HR) ch9¶74 common dimensions ch4¶76 compliance, ETL system ch19¶11 compliance manager, ETL system ch19¶26 composite keys ch1¶42 computer resources, big data and ch21¶44 conformed dimensions ch2¶109, ch4¶76, ch11¶33 agile movement and ch4¶96 drill across ch4¶77, ch4¶79 grain ch4¶81 identical ch4¶80 insurance case study ch16¶42 limited conformity ch4¶88 shrunken on bus matrix ch4¶86 shrunken rollup dimensions ch4¶82 shrunken with row subset ch4¶84 conformed facts ch2¶44, ch4¶14 insurance case study ch16¶43 inventory case study ch4¶11 conforming system, ETL system ch19¶84 consistency adaptability ch1¶200 goals ch1¶9 consolidated fact tables ch2¶160 accounting case study ch7¶80 contacts, bridge tables ch8¶68 contribution amount (P&L statement) ch6¶201 correctly weighted reports ch10¶22 cost, activity-based costing measures ch6¶60 COUNT DISTINCT ch8¶49 country-specific calendars as outriggers ch12¶37 course registrations (education case study) ch13¶18 CRM (customer relationship management) ch8¶1 analytic ch8¶11 bridge tables customer contacts ch8¶68 multivalued ch8¶61 sparse attributes ch8¶67 complex customer behavior ch8¶70 customer data integration ch8¶100 multiple customer dimension conformity ch8¶105 single customer dimension ch8¶101 customer dimension and ch8¶17 addresses ch8¶26 addresses, international ch8¶27 counts with Type 2 ch8¶49 dates ch8¶34 facts, aggregated ch8¶35 hierarchies ch8¶54, ch8¶55 names ch8¶26 names, international ch8¶27 outriggers, low cardinality attribute set and ch8¶51 scores ch8¶36 segmentation ch8¶36 facts abnormal scenario indicators ch8¶103 satisfaction indicators ch8¶98 timespan ch8¶89 low latency data ch8¶115 operational ch8¶11 overview ch8¶5 social media and ch8¶8 step dimension, sequential behavior ch8¶78 currency, multiple fact tables ch2¶194 G/L (general ledger) ch7¶8 order transactions ch6¶52 current date attributes, dimension tables ch3¶56 customer contacts, bridge tables ch8¶68 customer dimension ch6¶23, ch6¶24, ch6¶29, ch6¶34 clickstream data ch15¶32 CRM and ch8¶17 addresses ch8¶26 addresses, international ch8¶27 counts with Type 2 ch8¶49 dates ch8¶35 facts, aggregated ch8¶35 hierarchies ch8¶52, ch8¶56 names ch8¶26 names, international ch8¶27 outriggers, low cardinality attribute set and ch8¶51 scores ch8¶36 segmentation ch8¶36 factless fact tables ch6¶34 hierarchies ch6¶24 multiple, partial conformity ch8¶15 single ch8¶11 single versus multiple dimension tables ch6¶29 customer matching ch8¶14 customer relationship management. case study.

Why Airplanes Crash: Aviation Safety in a Changing World

by

Clinton V. Oster

,

John S. Strong

and

C. Kurt Zorn

Published 28 May 1992

Homebuilt aircraft An airplane built from a kit or from basic material; these planes are not subject to the same standards as commercial aircraft, but are restricted as to where and when they can fly. Horizontal stabilizer The fixed horizontal component of an aircraft's tail assembly which controls up and down movement of the tail. Hub and spoke system A pattern of airline service that links outlying communities to a central hub airport. Hub and spoke flights are often arranged to match the collection and distribution of passengers from a number of spoke communities so that connections to cities beyond the hub are facilitated. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) An agency of the United Nations, composed of contracting countries, whose purpose is to develop the principles and techniques of international air navigation, transport, and safety.

…

Deregulation's route freedoms have allowed airlines to exploit the service advantages of hub and spoke route systems. By having a group of aircraft from many destinations all converge at an airport at about the same time, a great many connecting opportunities then can be offered passengers. If too many flights converge at one time, however, airport and airspace capacity can be strained, with congestion-related delays, declines in service quality, and much greater pressure on air traffic control to keep aircraft from colliding in the air or on the ground. In addition to the impacts of intensified hubbing, the increase in traffic volume stimulated in part by deregulation's lower fares, coupled with the 1981 dismissal of striking Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) controllers has increased pressure throughout most of the nation's air traffic control system.

…

The first is the impact of a carrier's financial situation on its safety performance. Second, is the impact of industry consolidation on safety. Third, is the impact of increased traffic handled through intensified hub and spoke route systems. These issues are of current concern in the United States and are becoming of increased concern in Canada and Australia as these countries' airline industries adapt to a less restrictive economic environment. As the economic regulatory environment changes in Europe and perhaps other regions of the world, they are likely to become worldwide concerns. Financial Performance Deteriorating or persistently poor financial performance can increase pressure for cost-cutting by carriers.

Competition Demystified

by

Bruce C. Greenwald

Published 31 Aug 2016

It could focus its local advertising where its route structure was most dense. There were substantial regional economies of scale for the airline that dominated a hub airport, as well as the benefits of needing to fly fewer planes to service its routes. But all the cost and revenue advantages of a hub-and-spoke system were vulnerable to intense competition from weaker carriers who, in order to fill their seats, dropped prices below what it cost to fly the passengers. When one airline dominated a hub, it made money. When two well-established airlines served a single hub city, they often managed to keep prices stable and profitable. But a third carrier, especially one trying to break into a new market, with low labor and other fixed costs, and with an aggressive management out to earn their wings, could wreak havoc on the incumbents’ income statements.

…

See Marketing Aetna Aggression avoiding costs nature of Airbus Aircraft industry Airline Deregulation Act Airline industry barriers to entry buyouts customer loyalty programs deregulation direct competition avoidance government regulation hub-and-spoke system industry map market segments market share stability price competition in returns technology travel agent relations yield management AMD (Advanced Micro Devices) Intel v. America Japan v. manufacturing productivity American Airlines America Online. See AOL Amoco Anheuser-Busch Coors v. market share stability Miller v.

…

Only the customers benefited. Of the many unanticipated changes induced by deregulation, the most far-reaching was the emergence of a hub-and-spoke route system. Under the pressure of competition, the trunk carriers realized that they could lower costs and fill more seats by funneling traffic through hub cities, where long-distance and short-haul flights converged. A single hub connected directly to 40 cities at the ends of its spokes would link 440 city pairs with no more than one stop or change of planes. The airline could concentrate its maintenance and passenger service facilities in the hub airports. It could focus its local advertising where its route structure was most dense.

Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am

by

Robert Gandt

Published 1 Mar 1995

The idea was that you could make money flying a passenger from New York to Europe it you also sold him a ticket to or from somewhere else in your system—Kansas City, Denver, Dallas. Each time Pan Am was poised to build a true domestic system that fed its international web, it had, instead, done something egregiously inappropriate, like buying a regional airline (National, 1980), which it then proceeded to dismantle instead of expanding into a hub-and-spoke operation. Or building a nonfeeder “halo” operation (the Northeast Shuttle, 1987) that was disconnected from the rest of the airline. Now it was too late. There was no money left to build anything. Even the shuttle was for sale. Pan Am’s summer of 1989 came and went, mostly without passengers. Almost all advance bookings had been wiped out by the disaster at Lockerbie.

…

The truth was that almost nobody was making money flying the North Atlantic. Historically, the Pacific had been Pan Am’s only real moneymaker, which was why, of course, United Airlines had bought it from Ed Acker in 1985. The Atlantic had become a cheap-fare market, with too many carriers flying too many seats for ridiculously low fares. The other major players on the Atlantic—United, American, TWA—fed their international flights from strong hub-and-spoke domestic systems—something Pan Am had never developed. The idea was that you could make money flying a passenger from New York to Europe it you also sold him a ticket to or from somewhere else in your system—Kansas City, Denver, Dallas.

…

Delta was one of the first airlines to construct a hub-and-spoke system, concentrating its activity at “hubs” like Atlanta, Dallas, Cincinnati, and Salt Lake City, with feeder routes—“spokes”—radiating outward to its hundreds of satellite destinations. The “Big Three”—American, United, and Delta—had all prospered under deregulation, developing hub-and-spoke networks, frequent-flier programs, computer reservations systems, and sophisticated yield management strategies that enabled them to overwhelm their regional competitors. While American and United, both flush with cash, spent over a billion dollars buying up the routes of Pan Am, TWA, Continental, and Eastern, Delta had held back.

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by

Scott E. Page

Published 27 Nov 2018

If all 45 friendships existed, then the person’s clustering coefficient would equal 1, the maximal possible value. The clustering coefficient for the entire network equals the average of the clustering coefficients of the individual nodes. Figure 10.1: A Hub-and-Spoke Network and a Geographic Network Figure 10.1 shows two networks with thirteen nodes: a hub-and-spoke network and a geographic network. In the hub-and-spoke network, the hub has degree 12 and all other nodes have degree 1, for an average degree of less than 2. The degree distribution is unequal. The hub has a distance of 1 to every node. All other nodes have a distance of 1 to the hub and a distance of 2 to the other nodes.

…

This network, therefore, does not seem to have much of an effect on the likelihood of disease spread. Next, consider the hub-and-spoke network. The first node to get the disease could be the hub or a spoke. If the hub catches the disease, then it could spread the disease to any one of the spokes. We would expect the disease to spread, even for a low probability of spreading. If a spoke caught the disease, then the only possible node that could catch the disease is the hub. And as we just learned, if the hub catches the disease, the disease will spread even for low probabilities of spreading. For the hub-and-spoke network, R0 is less informative because if the hub catches the disease, the disease will spread.

…

The organization of this chapter follows the same structure-logic-function format we applied to distributions. We first characterize the structure of networks using statistical measures of degree, path length, clustering coefficient, and community structure. Then we discuss common classes of networks: random networks, hub-and-spoke networks, geographic networks, small-world networks, and power-law networks. After that we turn to the logic of how networks form. We construct micro-level processes that produce the network structures we see. Last, we take up function, the question of why network structure matters. Here we focus on five implications.

Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet

by

Andrew Blum

Published 28 May 2012

Many engineers use the airport analogy: in addition to the handful of global megahubs, there are hundreds of regional hubs, which exist to capture and redistribute as much of the traffic within their area as is practical. But as with the airlines, the smaller nodes of this hub-and-spoke system are always pressured by the tendency toward global consolidation. As Internet networks (or airlines) merge, the big hubs become even bigger—sometimes with a significant loss of efficiency. In Minnesota, the local network engineers refer to this as the “Chicago problem.” Two small competing Internet service providers in rural Minnesota might find themselves sending and receiving all their data to and from Chicago, by buying capacity on the paths of one of the big nationwide backbones, like Level 3 or Verizon.

…

On his maps, Krisetya portrayed this by showing the most heavily trafficked routes between cities, such as between New York and London, with the thickest lines—not because there were necessarily more cables there (or some single, superthick cable) but because that was the route across which the most data flowed. This was an insight that dated back to that first report. “If you look inside the Internet cloud a fairly distinct hub-and-spoke structure begins to emerge at both an operational (networking) and physical (geopolitical) level,” it explained. The Internet’s structure “is based upon a core of meshed connectivity between world cities on coastal shores—Silicon Valley, New York and Washington, DC; London, Paris, Amsterdam and Frankfurt; Tokyo and Seoul.”

…

See also specific hub Hubs + Spokes: A TeleGeography Internet Reader (TeleGeography), 26 Hugh O’Kane Electric Company, 165, 166, 167 Hurricane Electric, 121, 266 IBM, 52 IMP (interface message processor) beginning of Internet and, 36, 39–49 expansion of Internet and, 50 first successful transmission of, 48 India, 204 “information highway”: Internet as, 19–20, 63–64 ING Canada, 124 International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, 166 Internet backbone of, 14, 18 cables as “inter” part of, 97 capitalization of, 106–7 centers of, 9, 108–9, 112–13, 268 decentralization of, 54 earth’s connection to, 101–3 efficiency of, 231 essence of, 47, 135 expansion of, 6, 49–57, 109, 118, 138 fail-safe for, 100 286 as fantasy, 8 fickleness of, 261 founding ideology of, 54, 133 geography of, 28 globalization of, 70–71, 87, 193 Gore as inventor of, 63 “ground truth” of, 29 as handmade, 118 history of, 35–57, 107, 147 as hub-and-spoke system, 109–10 as human construction, 158 images of, 5, 6–8, 9, 18, 34, 107–8, 229–30, 266–68 as “information highway,” 19–20, 63–64 Kleinrock as a father of, 41–42 light of, 162, 163 limits of, 3 as math made manifest, 163 meshed connectivity of, 27, 64–65 most important places on, 127 myths about, 40 openness/publicness of, 30–31, 73–75, 116, 117–18, 124, 133 as overlap of geographical and physical elements, 19 photographs of, 21 prevalence of, 3, 34 questions about what is the, 2–10, 264–68 quintessence of, 163 reality of, 9 as self-healing, 200 as series of tubes, 5–6 shutdown of Blum’s, 1–4, 18, 144, 264 smell of, 44, 49 structure of, 27, 54, 64–65, 87 threats to, 116–17 uneven distribution of, 262 as unfinished, 67 uniqueness of, 106 usage of, 3, 34, 55, 66–67 Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, 29, 30, 31, 45 Internet exchanges “IX” as center of Internet, 108–9, 112–13 characteristics of largest, 111–13 competition among, 133–35 definition of, 109 gap between average-size and large, 130 as hub-and-spoke system, 109–10 location of, 113 peering and, 121–22, 126, 127, 129, 130 problems of, 109–11 rationale for, 109 security at, 113–16 See also specific exchange Internet Explorer (Microsoft), 57 Internet Heritage Site and Archive, Kleinrock, 44–45 “Internet Mapping Project” (Kelly), 7–8 Interxion, 140 Inventing the Internet (Abbate), 35–36 IP addresses, 29, 30, 31–32 The IT Crowd (TV show), 108, 143 Jagiellonian University (Poland): Traceroute example for, 31–32 Japan, 27, 33, 111, 113, 196, 198, 199, 201, 208 Jobs, Steve, 267 JPNAP (Tokyo), 111, 113 Juniper routers, 99–100 Justice Department, US, 123 Karlson, Dave, 244–45 Kelly, Kevin, 7, 8–9 Kenya, 198 Kingdom Brunel, Isambard, 203, 253 Kirn, Walter, 38 Kleinrock Internet Heritage Site and Archive (UCLA), 44–45 Kleinrock, Leonard, 36, 41–49, 51, 52, 69, 158 Kozlowski, Dennis, 195 KPN, 148, 155, 266 Krisetya, Markus, 13–17, 21, 23, 25, 26–27, 28, 45 Kubin-Nicholson Corporation, 13–14, 16–17, 21 landing stations, cable, 193, 202, 203.

The Sushi Economy: Globalization and the Making of a Modern Delicacy

by

Sasha Issenberg

Published 1 Jan 2007

Shinji ended up in the fish business only when, after graduating from college with an economics degree and no career prospects, his rugby coach introduced him to a relative who worked at Toiichi. Shinji took the entrance test and became an auctioneer at Tsukiji, handling sales of “sushi fish,” as non-tuna seafood for the raw market is classified. After a few years, he joined the family business, and in 1985 inherited the store. It was a precipitous time to become a fishmonger. The hub-and-spoke network of municipal fish markets and local retailers had long provided the Japanese their central source of protein, given the abundance of seafood in all parts of the country and the limited availability of livestock in most of them. (There is little dairy in traditional Japanese cuisine because farmers never practiced large-scale animal husbandry.)

…

Kliss also decided he didn’t need a dockside presence in Gloucester and instead set up shop in an old Hood milk factory in the industrial suburb of Lynn. It was a long way from any open water, but minutes from Boston’s Logan Airport and more or less equidistant between Cape Cod and the north shore. Kliss was relying on a hub-and-spoke mentality; he would just dispatch trucks to Gloucester docks when fish came in and bring them back to Lynn for processing. He would have someone run a truck along Cape Cod to do the same there. It demanded more flexibility than being able to sit on the wharf like Godfried and wait for boats to come in, but would help reduce the most significant fixed costs an agent faces.

…

See China; sushi economy Gibraltar globalization and black market seafood sushi economy Tsukiji Market (Tokyo) See also sushi economy Gloucester, Massachusetts Glynn, Andy Godfried, Mark “Golden Age of American food chemistry,” “Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention” (Friedman) Gomi, Yoshitomo good, tuna becoming a Google satellite maps gratuities, pooling Griffin, Albert hake hakozushi (box sushi) hamachi handling standards for fish handrolls “hard cargo,” harvesting tuna Hawaii haya-zushi (“quick sushi”) head sushi chef Hepburn, Audrey Hibino, Terutoshi hierarchical division of labor, sushi bars Hirohito (Emperor of Japan) Hitch, Steve Hollywood and sushi home chefs Hori, Takeaki horse mackerel (aji) horseradish to kill toxins Hoshizaki, Sadagoro hub-and-spoke mentality Hudson, Rock hunter-gatherers hurricanes Hussein, Saddam ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of the Atlantic Tuna) iceboxes ice for insulating fish Iida, Toichiro Iida, Tsunenori Imaizumi, Teruo, 90 immigrants to California, 81–82 inari India ingredients, adding innovation, promise of intelligence gathering on tuna ranching intermediate wholesaler (nakaoroshi) International Commission for the Conservation of the Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT), 232 internment of Japanese inventory, checking inventory control, sushi chefs Islam, Seif alIzawa, Arata JAL.

The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future

by

Chris Guillebeau

Published 7 May 2012

Strategies to do this include outsourcing, affiliate recruitment, and partnerships. Use the hub-and-spoke model of maintaining one online home base while using other outposts to diversify yourself. When it comes to outsourcing, decide for yourself what’s best. The decision will probably come down to two things: the kind of business you’re building and your personality. Carefully chosen partnerships can create leverage; just make sure that’s what you want to do. Use the One-Page Partnership Agreement for simple arrangements. *I’m grateful to Chris Brogan for the term outposts as well as the general concept of the hub and spoke applied to building a brand.

…

As a business grows and the business owner begins itching for new projects, he or she essentially has two options for self-made franchising: Option 1: Reach more people with the same message. Option 2: Reach different people with a new message. Either option is valid, and both can be rewarding. For the first option, it may be helpful to think of the “hub-and-spoke” model when building a brand, especially online. In this model, the hub is your main website: often an e-commerce site where something is sold, but it could also be a blog, a community forum, or something else. The hub is a home base with all the content curated by you or your team and ultimately where you hope to drive new visitors, prospects, and customers.

…

Clients tell Gary where they want to go, which airline their miles are coming from, and any restrictions they have on their travel dates. Then Gary gets to work, combing databases to check on availability, phoning the airlines, and taking advantage of every loophole. It may sound strange to pay $250 for something you could do on your own for free, but the value Gary provides through the service is immense: Many of the trips he arranges would otherwise cost $5,000 or more. He specializes in first- and business-class itineraries, and some of them feature as many as six airlines on a single award ticket. You want a free stopover in Paris en route to Johannesburg?

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by

William Davidow

and

Michael Malone

Published 18 Feb 2020

Part-time workers now perform jobs that once came with salaries, health care, and other benefits. A part-time Uber worker displaces the fleet taxi driver. A skilled union electrician suddenly finds himself doing part-time work via TaskRabbit. A lot more people are going to be working in the gig economy. But perhaps the most significant phenomenon of all is what we would call the hub-and-spoke business model, in which a small, highly compensated core group works for a company that organizes the work of hundreds, thousands, and tens of thousands of subcontractors. Uber has about 12,000 employees and contracts with approximately 1.5 million drivers worldwide—a 100 to 1 ratio.54 Facebook tops that, with about 25,000 employees and approximately 2 billion active users who provide the company with monetizable content for free, a ratio of 8,000 to 1.55 These companies illustrate another of the important commercial trends identified at the start of this chapter: that the sharing economy will drive the transformation of a whole range of commercial enterprises.

…

Hotels will not go away. Many people will never use shared office space or even consider sharing a stranger’s car. But new business models will exert price pressures on many capital-intensive businesses, making it much more difficult for them to grow and compete. From a commercial and social point of view, the hub-and-spoke model of business in the shared economy may be of greater significance than the asset-sharing aspect. It might be said that the “secret sauce” of the shared economy is the principle that the more workers you can outsource, the better it will be for the owners and senior management. A permanent employee is a double-edged sword.

…

The transition from tribal cultures to agricultural communities depended on the development of better modes of transportation—wagons drawn by horses and oxen and ships that could transport goods. Cities would never have been viable without the means to get food and energy (firewood at first, and later coal and other petroleum products) in from the countryside and the goods that they manufactured out to distant markets. The railroad created densely populated industrial cities and the hub-and-spoke pattern of suburban infrastructure, in which homes were built along railroad lines. The automobile created a more sprawling, two-dimensional suburban infrastructure, in which homes, businesses, and shopping centers could be located anywhere a car could reach. A lot of the economic and employment growth of the post–World War II period was created by building those highways, shopping centers, and detached houses.

Aerotropolis

by

John D. Kasarda

and

Greg Lindsay

Published 2 Jan 2009

Competition proved fatal for Braniff, Dallas’s hometown airline since 1928 and one of the fastest growing in America until deregulation. Four years later it was defunct, followed by Eastern and Pan Am within a decade and more than a hundred others in their wake. The surviving majors scrambled to be more efficient in the face of the industry’s first perfect storm. (There would be so many others in the years to come.) Suddenly able and expected to fly to and from every city, they found it impossible to do so profitably. American Airlines was the first to stop trying and to switch to a hub-and-spoke system instead. The advantage was mathematical: Routes increased exponentially as the number of cities served increased arithmetically.

…

R., 279, 282 Gordon, Gerry, 43–44, 45 Gore, Al, 343, 344–45 Gou, Terry, 396–97, 432 Granholm, Jennifer, 183 Great Depression, 210 Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, 176 Greater Westchester Homeowners Association, 29 Great Tea Race, 385–86 green cities, New Songdo City as, 4, 356–357; New York as, 356 greenhouse gases: from air travel, 333;from cattle, 232–33; global emissions of, 333 Green Metropolis (Owen), 356–57 Greenpeace, 346; opposition to Heathrow expansion by, 15 Green Revolution, 233 Guangzhou, China: Africans living in, 320; airport plans in, 373, 379; designed as aerotropolis hub, 377, 383–84; FedEx hub outside, 372–73; size and growth of, 373, 378, 380, 383 Guangzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone (GETDZ), 384 Guardian, The, 292 Guenzel, Robert, 188 Haddock, Ronald, 204, 205 Hamilton, Ontario, aerotropolis plans in, 193 Hamzeh, Assem and Dina, 287–89 Hansen, James, 343 Harvey, David, 136 Hatoyama, Yukio, 403 Hawley, Amos, 7, 11, 185, 424, 425 Hayden, Tom, 31 health care: aerotropolis dedicated to, 277; cities as medical hubs for, 269; globalization of, 267, 268; medical tourism and, 265–76; reforms, 267; as service industry, 168; U.S. cost of, 267–68 health care reform, medical tourism as boon to, 274 Heathrow Airport, 13–17, 176; economic engine surrounding, 15; expansion of, 15–17, 168, 343, 351–52; high-speed rail to, 351–52, 432; as victim of its own success, 14 Hennig, Joe, 128–29 Henry Ford Museum, 206 Heritage Creek, Ky., 64, 89–90 Hewlett, Bill, 365 High Court, British, 16 Highland Ranch, Colo., 139 High Point, N.C., 111 high-speed rail (HSR), 351–52, 432 Hilverda De Boer, 215, 216 Hobbes, Thomas, 207 Hong Kong, China, 24; as aerotropolis, 378, 382; capacity challenges facing, 372; connected via high-speed rail to Pearl River Delta, 378; economy of, Hong Kong (cont. ) 374; as export gateway, 372; Pear River Delta managed by, 375, 376, 377–78, 380–81; political autonomy of, 377; smiley curve managed by, 374–75, 380 Hong Kong International Airport, 372 Hon Hai Precision Industry, 396 housing: carbon footprint of, 431; greenhouse gases from, 336, 337 housing bust, 394 Hsieh, Tony, 70–71, 74 Huang, Bunnie, 367 hub-and-spoke, 95 Hubbert, M. King, 330 Hubbert’s Peak, 330 hubs, hubbing, 95–107; population within, 99 Hughes Aircraft, 27, 28 Hui, Stanley, 380 Human Genome Project, 349 humanity, as urban species, 10 Human Rights Watch, 253 Hunan Sunzone Optoelectronics, 409 Hyderabad, India, 277–78, 279, 281 Iberia (airline), 16 IBM, 9, 172, 368 Immelt, Jeff, 202–203, 388, 426 Incheon International Airport, 4, 354 Inconvienent Truth, An (Gore), 345 India: aerotropolis plans in, 19, 277–79; airline expansion in, 276, 282; aviation infrastructure in, 278–79, 282–85; democracy in, 280; economy of, 277–78, 279, 285; infrastructure spending in, 279–82; medical tourism in, 275–77 Indian Airways, 278 Indira Ghandi International Airport, 279, 284–85 Infosys, 281, 283 infrastructure, government spending on, 10, 178, 279–82 Innovator’s Dilemma, The (Christensen), 370 Instant Age: aerotropolis as product of, 6; Amazon Prime as product of, 76; cities of, 12–13, 19–20, 23–24; competitiveness among cities in, 175, 192–93, 195, 352; globalization in, 17; increasing connectivity in, 414; price of speed vs. oil in, 338 instant cities, 353–58; badly planned, 4, 261, 353, 355; hobbled by utopianism, 355; near airports, 358; New Songdo City as template for, 357 Intercity Railway, 406 Intergovermental Panel on Climate Change, 230 International Air Transport Association, 346 International Enegery Agency, 342, 344 International Floral and Gift Center, 110 International Monetary Fund (IMF), 353–54 Internet: aerotropoli as physical, 9–10; aviation as physical, 176; Dulles as capital of, 41–42; as early military project, 28; economic boom of, 210; globalization fostered by, 176; retail accelerated by, 76–77; Silicon Valley shaped by, 12; social networking as fuel of, 113; start-ups and, 42–43; as utility, 357 Inventec, 397 iPad, 371 Iranian Revolution, 342 Irvine Business Complex, 37 Irvin Industries, 211 iWonder, 371 Jackson, Jesse, Jr., 52, 57; airport proposal of, 53–56 Jacobs, Jane, 22, 186, 201 Japan, 391, 393, 403; car ownership in, 187; floral market in, 223; high-speed rail in, 351 jatropha curcas, 347 Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority, 292–93 Jebel Ali harbor, 294–95 Jet Age, launched by Boeing 707s, 27 Jet Airways, 278 JetBlue, 22, 405 jet fuel, peak price of, 337 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, CalTech, 28 Jevons, William Stanley, 328 Jevons Paradox, 328–29, 344, 351 J.

…

“And they have always valued family and extended family. Wherever they go, they always find a gateway home.” The American hub at DFW was the world’s first. Its opening in 1981 was to the modern era of aviation what the interstate highway system was to the postwar car culture: the innovation that made everything else possible. The hub-and-spoke system, with its waves of flights to anywhere and everywhere, created a critical mass of connectivity—so much that the laws of nature governing how we live, how we work, and how far we’ll travel to do either on any given day were seemingly repealed. One unintended consequence was several thousand Tongans appearing on its door-step; another was a six-foot-two, 297-pound tackle screaming “Mate ma’a Tonga!”

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by

Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou

Published 15 Feb 2015

Such business models include: software as a service (SaaS) in computing; power by the hour in aircraft engines; massive open online courses (MOOCs) in education; hub-and-spoke and yield management models in airlines; online retailing; and cloud computing. By flexing their assets, airlines such as Southwest Airlines, easyJet and Ryanair have created a new, low-cost market segment for flyers within the US and Europe, and have succeeded in challenging long-haul incumbents. First, the low-cost carriers rebased the existing airline business model by maximising the time that their most valuable assets – their aircraft – spend in the air, and reducing the time they spend on the ground. Second, they use a hub-and-spoke model that maximises reach while minimising the typical journey distance.

…

(Daru) 169 data, sharing with partners 59–60 data analytics 206 Datta, Munish 183 De Geer, Jacob 40 Decathlon 126–7, 128 deceleration of energy consumption 53, 54 decentralisation 47, 50, 51–2, 53–4, 66–7 Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) 49 Delabroy, Olivier 206, 207 delayed differentiation 57–8 Deloitte 14, 171 demand forecasts 58 democratisation of innovation 50–1, 127, 132, 166 deregulation 53, 54 design 75, 88–9 inclusive 194–5 for longevity 121 modular 67, 90 for next-generation customers 121–2 for postponement 67 for sustainability 82–4, 92, 93, 120–1, 195–6 see also CAD; C2C; E&I; R&D design-led organisations 71 designers 88, 93, 152 Detourbet, Gérard 4–5, 199 Deutsche Telekom 194 developed economies 190, 207 consumers 2, 9, 102, 189, 206 energy sector 52–3 frugal innovation in xvii frugality in 8, 218 development costs 22, 36 development cycle 21, 23, 42, 72, 129, 200 DHL 143 differentiation 57–8, 76, 150 digital disrupters 16–17 digital enrichment 89 digital integration 65–6 digital monitoring 65–6 digital prototyping 52 digital radiators 89 digital tools 47, 50, 53, 62, 164, 170 for tracking customer needs 28–9, 29–31 digitisation 53, 65–6, 174 disruptive innovation 10–11, 40, 70, 91, 170, 199 “disruptive value solutions” 191–3 distributed energy systems 53–4 distributed manufacturing 9 distribution 9, 54, 57, 96, 161 distributors 59–60, 76, 148 DIWO (do it with others) 128 DIY (do-it-yourself) 9, 17–18, 89, 128, 130–1, 134–6 health care 109–12 see also TechShops; FabLabs Doblin 171 doing better with less 12–16, 215 doing less for less 205–6 doing more with less 1–3, 16, 177, 181, 206, 215 Dougherty, Dale 134 dreamers 144 Dreamliner (Boeing) 92 dreams 140–1 DriveNow 86 drones 61, 150 Drucker, Peter 179 drug development 22, 23, 35, 171 see also GSK; Novartis drug manufacture 44–6 Dubrule, Paul 172–3 Duke 72 DuPont 33, 63 durability 83, 124 dynamic portfolio management techniques 27, 33 Dyson 71 E E&I (engage and iterate) principle xviii, 19–21, 27–34, 41–3, 192 promoting 34–41 e-commerce 132 e-learning 164–5 e-waste 24, 79, 87–8, 121 early movers 45, 200, 215 easyCar 85 easyJet 60 Eatwith 85 eco-aware customers 22, 26, 215 eco-design principles 74 see also C2C eco-friendly behaviour 108 eco-friendly products 3, 73–7, 81–2, 93, 122, 153, 185, 216 Ecomobilité Ventures 157 economic crisis 5–6, 46, 131, 180 economic growth 76–7 economic power, shifting 139 economic problems 153, 161–2 economies of scale 46, 51, 55, 137 Ecover 82 EDC (Cambridge University Engineering Design Centre) 194–5 Edelman Good Purpose survey 101 Trust Barometer 7 EdEx 61, 112 Edison, Thomas 9, 149, 151 education 16–17, 60, 61, 112–14, 135–6, 164–5, 181–3 efficacy 181–3 efficiency 33, 60, 71, 154, 209 Ehrenfeld, John 105 Eisenhower, Dwight D. 93 electric cars 47, 86, 172 electricity consumption 196 generation 74, 104 electronic waste see e-waste electronics, self-build 51 Ellen MacArthur Foundation 76, 81 emerging markets 16, 35, 40, 94, 190, 198, 205 aspirations 119–20, 198 cars aimed at 4–5, 16, 198–9 competitors 16, 205–6, 216 consumers 197–8, 198, 199, 203 distribution models 57 IBM and 199–202 infrastructure 56, 198, 207 innovation in 4, 39–40, 188–9, 205–6 products tailored to 38, 198–9, 200–2 Siemens and 187–9 suppliers 56 testing in 192 wages in 55 in Western economies 12–13 emissions 47, 78, 108 see also carbon emissions; greenhouse gas emissions employees 14, 37, 39, 84, 127, 174–5, 203–8, 217 as assets 63–5 cutting 153 empowering 65, 69–70 engaging 14, 64–5, 178–9, 180, 203–8, 215 health care for 210–11 incentives 7, 37, 38–9, 91–2, 184, 186, 207–8 and MacGyvers 167 Marks & Spencer 187 mental models 193–203 motivation 178, 180, 186, 192, 205–8 performance 69, 185–6 recruiting 70–1 training 76, 93, 152, 170, 189 younger 14, 79–80, 124, 204 see also organisational change empowering consumers 22, 105, 106 empowering employees 65, 69–70 empowering prosumers 139–43 energy 51, 103, 109, 119, 188, 196, 203 generation 52–4, 74, 104, 197 renewable 8, 53, 74, 86, 91, 136, 142, 196 energy companies 52–4, 99, 103 energy consumption 9, 53, 54, 107, 196 homes 54, 98–100, 106–9 reducing 74, 79, 91, 108, 159, 180 energy costs 161, 190 energy efficiency 12, 54, 75, 79, 191, 193–4, 194, 206 factories 197 Marks & Spencer 180–1, 183 workplaces 80, 193–4 energy sector 52–4, 197 engage and iterate see E&I engaging competitors 158–9 engaging customers 19–21, 24–6, 27–33, 34, 35, 38–9, 42–3, 115, 128, 170 advertising 71–2 engaging employees 14, 64–5, 178–9, 180, 203–8, 215 engaging local communities 52, 206–7 engaging prosumers 139–43, 143–6 “enlightened self-disruption” 206 “enlightened self-interest” 172 entrenched thinking 14–16 entrepreneurial culture 76 entrepreneurs 150, 163–4, 166 engaging with 150, 151, 152, 163–4, 168, 173–6, 207 environmental cost 11 environmental degradation 7, 105 environmental footprint 12, 45, 90–1, 97, 203 environmental impact 7, 27, 73, 77, 90, 92, 174, 196 environmental problems, solving 82, 204 environmental protection agencies 74, 76 environmental responsibility 7, 10, 14, 124, 197 environmental standards 80, 196 environmental sustainability 73–5, 76, 85, 186 Ericsson 56 Eschenbach, Erich Ebner von 86 Esmeijer, Bob 32 Essilor 57, 146, 161 ethnographic research 29–31, 121–2, 157–8 Etsy 132 EU energy consumption 54 sustainability regulation 8, 78, 79, 216 Europe 12–13, 22, 40, 44, 120, 161, 188 ageing populations 194 energy consumption 54 frugal innovation in 215–16, 218 greener buildings 196 horizontal economy 133 incomes 5–6 regulation 8, 78, 79, 216 sharing 85, 138–9 tinkering culture 18, 133–4 European Commission 8, 103, 137 Eurostar 10, 163 evangelists 145 EveryoneOn 162 evolutionary change 177–9 execution agility 33–4 Expedia 173, 174 expert customers 146 “experts of solutions” 164 Expliseat 121 ExploLab 42 “Eye Mitras” 146 F F3 (flexible, fast and future) factories 66–7 Faber, Emmanuel 184 FabLabs 9, 134–5 Facebook 16, 29, 62, 133, 144, 146, 147, 150 factories 66–7, 134, 197 see also micro-factories “factory in a box” 134 factory-agnostic products 67 Fadell, Tony 99 failures 33–4, 42 at launch 22, 25, 141, 171 FastWorks 41, 170 FDA (Food and Drug Administration) 39, 79 FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) 13, 17, 161 FedEx 65, 154 Ferrero 57 FGI Research 29 FI (frugal intensity) 10–11, 189–93 FIAM Italia 88–9 Fields, Mark 70 FieldTurf 75, 76 financial habits 115–16 financial measurements 118 financial services 13, 18, 57, 63, 124–5, 135, 161–2, 201 underserved public 13, 17, 161–2 Finland 103 first-mover advantage 45, 200 FirstBuild 52, 152 fixed assets 46, 161 fixers 146 flexibility 33, 35, 65, 90, 143 of 20th-century model 23, 46, 51, 69 lattice organisation 63–4 manufacturing 57, 66, 191 of sharing 9–10, 124 supply chain 57–8 flexible logistics 57–8, 191 flexing assets xviii–xix, 44–6, 65–72, 190 employees 63–5, 69–71 manufacturing 46–54, 65 R&D 67 services 60–3, 65 supply chain 54–60, 65, 66–7, 67–8 FLOOW2 161 Flourishing: A Frank Conversation about Sustainability (Ehrenfeld and Hoffman, 2013) 105 FOAK (First of a Kind) 142 “follow me home” approach 20 Food and Drug Administration see FDA Ford, Henry 9, 70, 98, 129, 165 Ford Motor Company 50, 58, 70, 89, 165–7, 171 Forrester Research 16, 25, 143 Frampton, Jez 142 France 5–6, 40, 93, 133, 138, 172, 194 consumer behaviour 102, 103 Francis, Simon 71 Franklin, Benjamin 134, 218 freight costs 59 Fried, Limor 130 frugal competitors 16–18, 26, 216 frugal consumers 197–200 frugal economy 5–12 frugal engineering 4, 40 frugal health-care 208–13 frugal innovation xvii–xx, 4, 10–16, 215–18 six principles xvii–xx frugal intensity see FI frugal manufacturing 44–54 frugal mindset xvii–xviii, 198–203 frugal organisations 63–5, 69 see also organisational culture frugal services 60–3, 216 frugal supply chain 54–60 frugality 5, 8, 119–20, 204, 218 fuel consumption, reducing 106–7 fuel costs 121 fuel efficiency 8, 12, 24, 47, 78, 131, 197 Fujitsu 11, 29–31 future customers 193–5, 205 FutureLearn 61, 112, 113 G GAFAs (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon) 150, 155, 211, 216 gamification 108, 112, 113–14, 162 Gap 7 Gartner 59–60 Gates, Bill 138 GDF Suez 53–4 GDP (gross domestic product) 104 GE (General Electric) 9, 21, 40, 139, 149–53, 161, 171, 215 additive manufacturing 49 “culture of simplification” 170 learning from start-ups 40–1 micro-factory 52 GE Aviation 49 GE Distributed Power 53 GE Garages 152 GE Healthcare 40 GE Ventures 151 Gebbia, Joe 163 General Electric see GE General Motors see GM Genzyme 45 Gerdau Corporation 159 Germany 66, 85, 93, 103, 136, 156, 194 ageing workforce 13, 49, 153 impact of recession 5, 7 market 85, 189 Mars distribution in 57, 161 Gershenfeld, Neil 134 Ghosn, Carlos 4, 198–9, 217 Giannuzzi, Michel 73, 76 Gibson, James 120 giffgaff 147–8 Gillies, Richard 185 GlaxoSmithKline see GSK Global Innovation Barometer 139 global networks 39–40, 52, 152–3, 202 Global Nutrition Group (PepsiCo) 179 global recovery of waste (GROW) 87–9 global supply chains 36, 137 Global Value Innovation Centre (GVIC) (PepsiCo) 190–2 GlobeScan 102 GM (General Motors) 21, 50, 68, 155, 166 see also Opel goals 94, 178, 179–89, 217 “big, hairy audacious” 90–1, 158–9, 179, 191–2 good-enough approach 27–8, 33–4, 42, 170, 188–9, 200 Google 17, 38, 63, 130, 136, 150, 155, 172 Gore, Bill 63–4, 69 Gore, Bob 63 Gore, Vieve 63 governments 6–7, 7–8, 13, 109, 161 Graeber, Charles 201 Greece 5, 6 greenhouse gas emissions 102, 196 reducing 8, 78, 78–9, 95 see also carbon emissions gross domestic product see GDP Groth, Olaf 153 GROW (global recovery of waste) 87–9 growth 6, 13, 76–7, 79, 80, 104–5 of companies 72, 100 sustainability 72, 76–7, 79–80 GSK (GlaxoSmithKline) 35–6, 36–7, 39, 45, 215 GSK Canada 29 gThrive 118 GVIC (Global Value Innovation Centre) (PepsiCo) 190–2 Gyproc 160 H hackers 130, 141–2 Haier 16 “handprint” of companies 196 Harley-Davidson 66, 140 Hasbro 144 Hatch, Mark 134–5 health care 13, 109–12, 135, 153, 161, 198, 202–3, 208–13 health insurance 109, 208–13 heat, harvesting 89 Heathrow Airport 195 Heck, Stefan 87–8 Heineken 84 Herman Miller 84 HERs (home energy reports) 109 Hershey 57 Higgs Index 90 Hilton 10, 163 Hippel, Eric Von 130 Hoffman, Andrew 105 home energy reports (HERs) 109 homes 157–8 energy 53, 103, 109 horizontal economy 133–9 horizontal ecosystems 154–5 Hosking, Ian 195 Howard, Steve 78 hub-and-spoke models 60 HubCap 107–8 human-sized factories 63, 64 Hurtiger, Jean-Marie 1–2 HVCs (hybrid value chains) 161–2 hybrid make/move model 57–8 hybrid value chains (HVCs) 161–2 hyper-collaboration 153–76, 190–1 I I-Lab 206–7 Ibis 173 IBM 17, 39, 142, 154, 171, 171–2, 199–202 R&D in Nairobi 200–2 ideas42 109 ideators 144–5 IDEO 121 IKEA 78, 100, 108, 132, 142, 194 IME (Institute of Mentorship for Entrepreneurs) 175 Immelt, Jeff 170, 217 immersion 29–31, 31–2, 193–4 Impact Infrastructure 197 improvisation 27, 179, 182 Inc. magazine 81–2 incentives 7, 37, 38–9, 91–2, 184, 186, 207–8, 213 inclusion 7, 13 inclusive design 194–5 Inclusive Design Consortium 195 incomes 5, 6, 102, 194 India 40, 57, 102, 191, 200, 216 aspirations 119, 198 emerging market 4, 12, 38, 146, 169, 197, 205, 207 frugal innovation 4–5, 169 mobile phones 56, 198 Renault in 4–5, 40, 198–9 selling into 119, 187–8 Indiegogo 137, 138, 152 industrial model 46, 55, 80–1 industrial symbiosis 159–60 inequality 6, 13 inflation 6 infrastructure 46, 92–3, 198, 207 ingenuity xx, 2, 14, 18, 70, 76, 164, 166, 217 jugaad xvii, 199 Ingredion 158–9 InHome 157–8 innovation 14, 23, 40, 50–1, 70, 153, 200 costs 10–11, 150, 168, 171 democratisation 50–1, 127, 132, 166 disruptive 10–11, 40, 70, 91, 170, 199 process 28–34, 43 speed 10–11, 129, 150, 167–8, 173 technology-led 26 see also frugal innovation; prosumers; R&D innovation brokering 168–9, 173–6 Innovation Learning Network 203 innovative friends xx, 150–3, 176 see also hyper-collaboration InProcess 121–2, 157–8 Institute of Mentorship for Entrepreneurs (IME) 175 insurance sector 116 intellectual capital 171–2 Interbrand 142 Interface 90–1, 123 interfaces 98, 99 internal agility 169–70 internet 62, 65, 85, 103, 106, 133, 174, 206 Internet of Things 32, 106, 150, 169, 174 Intuit 19–21, 29, 145 inventors 50–1, 134, 137–9, 149, 150–1 inventory 54, 58 investment crowdfunding 137–9 in R&D 15, 22, 23, 28, 141, 149, 152, 171, 187 return on 22, 197 investors 123–4, 180, 197, 204–5 iPhones 16, 100, 107, 131, 148 Ispo 84 Italy 6, 103, 133 iteration 20–1, 31, 36, 38, 41, 52, 170, 179, 200, 213–14 iZettle 40 J Janssen Healthcare Innovation 111 Japan 8, 22, 40, 52, 102, 196, 200 ageing population 6, 194 ageing workforce 2, 13, 49, 153 austerity 5, 6 environmental standards 78–9 and frugal innovation 215–16, 218 horizontal economy 133 regulation 216 robotics 49–50 Jaruzelski, Barry 23 Jawbone 110 Jeppesen Sanderson 145 jiejian chuangxin 200, 202 Jimenez, Joseph 45 Jobs, Steve 68–9, 164 John and Catherine T.

…

It makes the world’s lightest aircraft seats entirely out of titanium, each weighing just 4 kilograms. The seats can save an airline up to $500,000 per plane per year on fuel cost alone. Although an Expliseat costs more than rival products, each seat can be assembled and installed within minutes and can be used 100,000 times without deteriorating. Furthermore, its ergonomic design and lower bulk provide an extra 5 centimetres of legroom and better shock absorption. Although Expliseat’s economy-class seats may not match the $400,000 business-class seats for comfort, low-cost airlines are eager to offer something extra for those on a tight budget. Design for next-generation customers Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, an international design and consulting company, challenges designers to “invent for the future consumer”.

Boeing Versus Airbus: The Inside Story of the Greatest International Competition in Business

by

John Newhouse

Published 16 Jan 2007

CHAPTER SEVEN The Very Large Airplane AFTER THE AIRCRAFT industry’s downturn in the early 1990s, it appeared that the only new airliner likely to be built for the next several years would be a superjumbo. A much bigger airplane, the argument ran, would increase the number of passengers who could be flown between major urban centers connected by the hub-and-spoke airlines. Seat mile costs had to come down, and only the very large commercial transport—the VLCT as it was then labeled—would allow airlines to accomplish that, provided, of course, they could fill all those seats. The unknown but unavoidably huge cost of building the very large airplane, or VLA, as it was also known, was intimidating.

…

AIRBUS AND ESPECIALLY Boeing each gambled massively on two new airplanes that represent radically different approaches to the market. There is probably no precedent for such a divergence. The A380, because it can carry a huge number of passengers, is designed to fit within the hub-and-spoke pattern of air travel that the big airlines have favored. An A380 could take 550 passengers from Tokyo to, say, Los Angeles or New York, where many of them would then transfer to flights going to Denver, Phoenix, Cleveland, and so on. And, Airbus argues, this superjumbo airplane will be cheaper to operate than other aircraft, partly because it will burn less fuel per passenger.

…

Credit wasn’t a problem—there was a great deal of money chasing airplanes; airlines were borrowing 120 percent of the net purchase of their new aircraft. And they were busily expanding their hub airports. Airline deregulation, a useful step in principle, was never about building a strong industry; it was about lowering ticket prices by creating competition. And it did give rise to a commodity marketplace, hence competition. But most airlines either didn’t favor deregulation or, like Delta Airlines, openly opposed it. United Airlines, the nation’s largest carrier at the time, was the only strenuous advocate. The other big airlines had been reluctant to give up a regulated environment, which had offered an unstable industry protection against its prodigal tendencies.

How the Post Office Created America: A History

by

Winifred Gallagher

Published 7 Jan 2016

(One of their first projects was building a fort, called the Campus Martius, to protect themselves from the understandably aggrieved Native Americans they sought to displace.) Marietta got a post office in 1794, but by the time of statehood in 1803, it was one of just eighteen in all of sprawling Ohio. Delivering a letter from the East Coast to Ohio required heroic efforts from the post. In 1800, Postmaster General Habersham inaugurated the “hub and spoke” circulation system, in which large, centralized “distributing post offices” sorted an entire region’s mail, then dispersed it to the spokes, or local “common” post offices, where the recipients retrieved it. Most of the new state’s postal facilities were strung along the great Ohio River or its tributaries, which were the best means of transportation in wild terrain and the inspirations for its early “river roads.”

…

The new Highway Post Offices that were installed inside some trucks and buses were slower, prey to traffic jams, and less efficient than the smooth-sailing Railway Post Offices had been; they swayed more, which made sorting more difficult and induced more motion sickness. The mail had to be processed somewhere, however, and the post was forced to return to its old hub-and-spokes circulation system centered on large regional distributing post offices. This back-to-the-future strategy worked reasonably well in the burgeoning suburbs and exurbs, where the big trucks could sail into giant new mail processing centers that were custom-built for the purpose and conveniently positioned just off the new freeways.

…

To curb the contractors’ profitable practice of flying junk mail, he changed the basis of their compensation to the size of a plane’s cargo space rather than the mail’s weight. Partly to sweeten this bitter medicine, he also offered the carriers ten-year rather than four-year contracts. In exchange for this added security, the airlines greatly expanded their routes at no cost to the government. The act also empowered Brown to extend or consolidate airmail routes as he saw fit. When the new postal contracts were awarded to just the three large airlines, later United, American, and TWA, that had been personally invited to attend what was dubbed the postmaster general’s “Spoils Conference,” the charge that the post was bankrolling cronyism and discriminating against the smaller carriers led to the sensational scandal of 1934.

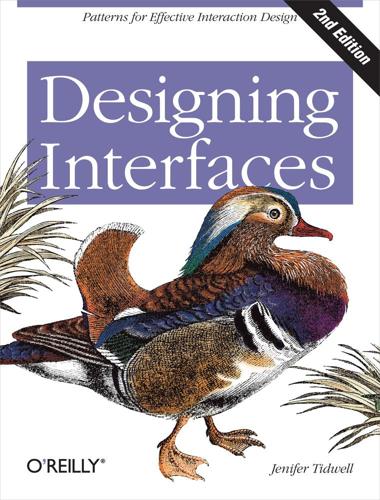

Designing Interfaces

by

Jenifer Tidwell

Published 15 Dec 2010

Now let’s look at a few models found in typical sites and apps: Hub and spoke Most often found on mobile devices, this architecture (Figure 3-1) lists all the major parts of the site or app on the home screen, or “hub.” The user clicks or taps through to them, does what she needs to do, and comes back to the hub to go somewhere else. The “spoke” screens focus tightly on their jobs, making careful use of space—they may not have room to list all the other major screens. The iPhone home screen is a good example; the Menu Page pattern found on some websites is another. Figure 3-1. Hub and spoke Fully connected Many websites follow this model.

…

Now, if these are pages that users can reach via search results, it’s doubly important that Figure 3-10 be put on each page. Visitors can click these to get to a “normal” page that tells them more about where they actually are. How Put a button or link on the page that brings the user back to a “safe place.” This might be a home page, a hub page in a hub-and-spoke design, or any page with full navigation and something self-explanatory on it. Exactly what it links to will depend upon the application’s design. Examples Websites often use clickable site logos as home-page links, usually in the upper left of a page. These provide an Escape Hatch in a familiar place, while helping with branding.

…