The Mysterious Mr. Nakamoto: A Fifteen-Year Quest to Unmask the Secret Genius Behind Crypto

by

Benjamin Wallace

Published 18 Mar 2025

Skye Grey had made a similar point when he doubled down on his Nick Szabo theory with a follow-up post: “Occam’s Razor: Who Is Most Likely to Be Satoshi Nakamoto?” “Occam’s razor,” I was starting to notice, was a go-to trope in Nakamotology. You could harness it in favor of just about any argument, which made it effectively meaningless. Something I heard almost as often was the medical-diagnostic injunction “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” “Bitcoin is a very non-obvious idea, of the kind that takes years of crystallization, maybe an entire lifetime,” Grey wrote. “An idea born of the cypherpunk mindset, developed over time by a person with a deep passion for economics of the most abstract kind and a mastery of unusual cryptography concepts.

…

And to conceive of Satoshi Nakamoto as a group, you had to imagine that a cabal in possession not only of the biggest secret in technology but also of the keys to a monstrously huge fortune, had defied incomprehensible odds and agreed: Mum’s the word. Every theory worth considering, in other words, had a critical flaw. My brain rang with buzzwords and clichés. Confirmation bias. Occam’s razor. When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras. I started seeing in my wife’s eyes a look I had tried to keep out of my own eyes during my first foray into Bitcoinland. It was that look of frank uninterest common to anyone who’d ever been stuck at a party listening to a blockchain bore. I found myself describing a family scheduling issue as “suboptimal.”

…

Perhaps his silence was cypherpunk omertà, or maybe it was a mark of respect for his friend’s wishes. Maybe Nick’s defenses of Bitcoin had been on behalf of his stricken pal, about whom Nick wrote, on his death, “we will miss you Hal Finney.” Maybe everyone had made this too complicated. Occam’s razor. If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras. If Hal was indeed Nakamoto, it would be the best possible outcome for Bitcoin enthusiasts. It would justify the sanctification of Satoshi. It would support the belief that he had acted from a benevolent selflessness—that Bitcoin was his gift to the world. James Donald was the Satoshi people feared.

The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts

by

Shane Parrish

Published 22 Nov 2019

We know that generally the flu is far more common than Ebola, so when a good doctor encounters a patient with what looks like the flu, the simplest explanation is almost certainly the correct one. A diagnosis of Ebola means a call to the Center for Disease Control and a quarantine—an expensive and panic-inducing mistake if the patient just has the flu. Thus, medical students are taught to heed the saying, “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” And for patients, Occam’s Razor is a good counter to hypochondria. Based on the same principles, you factor in the current state of your health to an evaluation of your current symptoms. Knowing that the simplest explanation is most likely to be true can help us avoid unnecessary panic and stress.

How Doctors Think

by

Jerome Groopman

Published 15 Jan 2007

In medical school, and later during residency training, the emphasis is on learning the typical picture of a certain disorder, whether it is a peptic ulcer or a migraine or a kidney stone. Seemingly unusual or atypical presentations often get short shrift. "Common things are common" is another cliché that was drilled into me during my training. Another echoing maxim on rounds: "When you hear hoofbeats, think about horses, not zebras." Rachel Stein, trawling through the long list of causes of Pneumocystis pneumonia, found a zebra. A nutritional deficiency can cause impaired immune defense and provide fertile ground for this infection. With his characteristic élan, Pat Croskerry, at Dalhousie University in Halifax, has coined the phrase "zebra retreat" to describe a doctor's shying away from a rare diagnosis.

…

When you or your loved one asks simply, "What else could it be?" you help bring closer to the surface the reality of uncertainty in medicine. "What else could it be?" is a key safeguard against these errors in thinking: premature closure, framing effect, availability from recent experience, the bias that the hoofbeats are horses and not zebras. Each cognitive error constrains the pursuit of answers, and correcting the error helps the doctor think of a test or procedure that he didn't previously consider and can make the diagnosis. "Is there anything that doesn't fit?" may be your next question. This follow-up should further prompt the physician to pause and let his mind roam more broadly.

Building Secure and Reliable Systems: Best Practices for Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Systems

by

Heather Adkins

,

Betsy Beyer

,

Paul Blankinship

,

Ana Oprea

,

Piotr Lewandowski

and

Adam Stubblefield

Published 29 Mar 2020

Some of the advice that follows can help, but there’s no real substitute for understanding the system ahead of time (see Chapter 6). Distinguish horses from zebras When you hear hoofbeats, do you first think of horses, or zebras? Instructors sometime pose this question to medical students learning how to triage and diagnose diseases. It’s a reminder that most ailments are common—most hoofbeats are caused by horses, not zebras. You can imagine why this is helpful advice for a medical student: they don’t want to assume symptoms add up to a rare disease when, in fact, the condition is common and straightforward to remedy.

Mindware: Tools for Smart Thinking

by

Richard E. Nisbett

Published 17 Aug 2015

Probably much more important than the rather minimal formal training in statistics, students learn about medical conditions and human behavior in potentially quantifiable ways and reason about them in explicitly statistical terms. “The patient has symptoms A, B, and C and does not have D and E. What is the likelihood that the patient has Disease Y? Disease Z? Disease Z, you say? You’re probably wrong about that. Disease Z is quite rare. If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras. What tests would you want to order? Tests Q and R, you say? You’re wrong. Those tests are not very statistically reliable; moreover they’re quite expensive. You might order test M or N, which are cheap and statistically reliable, but neither is a very valid predictor of either disease Y or disease Z.”

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation That Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe

by

William Poundstone

Published 3 Jun 2019

Doyle joins Bayes in making the subversive point that the lack of evidence (a dog not barking) can be as revealing as affirmative evidence is. Bayes’s rule says to look at the ratio of probabilities. The dog not barking is probable with a familiar visitor but improbable with a stranger. That is reason to favor the first possibility. 3. “When you hear hoofbeats look for horses, not zebras.” All else being equal, the more common explanation is to be preferred. Here’s another example: In the third grade I won a trophy for kickball. Which was more likely? • I won the trophy because I was the best at kickball out of all the kids in the third grade. • I won because it was a participation trophy (handed out to every kid to boost self-esteem).

Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue

by

Danielle Ofri

Published 31 Mar 2003

Perhaps I was biased, but young people who looked like concentration camp victims in New York City in the early 1990s usually had AIDS. Unless she had a rare genetic syndrome or some exotic tropical disease. But it was the attendings who always admonished the medical students—“When you hear hoofbeats, look for horses, not zebras.” Eileen stabilized in the ICU and was transferred back to my team a few days later. I learned from her family that Eileen had been sick for at least a few months, and that despite her mother’s pleadings, would not see a doctor. She had grown so weak that she could no longer get up from the living room couch.

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by

Gabriel Weinberg

and

Lauren McCann

Published 17 Jun 2019

The Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy (circa A.D. 90–168) stated, “We consider it a good principle to explain the phenomena by the simplest hypotheses possible.” More recently, the composer Roger Sessions, paraphrasing Albert Einstein, put it like this: “Everything should be made as simple as it can be, but not simpler!” In medicine, it’s known by this saying: “When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras.” A practical tactic is to look at your explanation of a situation, break it down into its constituent assumptions, and for each one, ask yourself: Does this assumption really need to be here? What evidence do I have that it should remain? Is it a false dependency? For example, Ockham’s razor would be helpful in the search for a long-term romantic partner.

Late Bloomers: The Power of Patience in a World Obsessed With Early Achievement

by

Rich Karlgaard

Published 15 Apr 2019

The Good, the Bad and the History

by

Jodi Taylor

Published 21 Jun 2023

The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload

by

Daniel J. Levitin

Published 18 Aug 2014

The base rate for doctors is higher, and so if you know nothing at all about the party, your best guess is you’ll run into more doctors than cabinet members. Similarly, if you suddenly get a headache and you’re a worrier, you may fear that you have a brain tumor. Unexplained headaches are very common; brain tumors are not. The cliché in medical diagnostics is “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” In other words, don’t ignore the base rate of what is most likely, given the symptoms. Cognitive psychology experiments have amply demonstrated that we typically ignore base rates in making judgments and decisions. Instead, we favor information we think is diagnostic, to use a medical term.

The Pragmatic Programmer

by

Andrew Hunt

and

Dave Thomas

Published 19 Oct 1999

When finally forced to sit down and read the documentation on select, he discovered the problem and corrected it in a matter of minutes. We now use the phrase "select is broken" as a gentle reminder whenever one of us starts blaming the system for a fault that is likely to be our own. Tip 26 "select" Isn't Broken Remember, if you see hoof prints, think horses—not zebras. The OS is probably not broken. And the database is probably just fine. If you "changed only one thing" and the system stopped working, that one thing was likely to be responsible, directly or indirectly, no matter how farfetched it seems. Sometimes the thing that changed is outside of your control: new versions of the OS, compiler, database, or other third-party software can wreak havoc with previously correct code.

The Last Stargazers: The Enduring Story of Astronomy's Vanishing Explorers

by

Emily Levesque

Published 3 Aug 2020

Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems

by

Betsy Beyer

,

Chris Jones

,

Jennifer Petoff

and

Niall Richard Murphy

Published 15 Apr 2016

Fixing the first and second common pitfalls is a matter of learning the system in question and becoming experienced with the common patterns used in distributed systems. The third trap is a set of logical fallacies that can be avoided by remembering that not all failures are equally probable—as doctors are taught, “when you hear hoofbeats, think of horses not zebras.”4 Also remember that, all things being equal, we should prefer simpler explanations.5 Finally, we should remember that correlation is not causation:6 some correlated events, say packet loss within a cluster and failed hard drives in the cluster, share common causes—in this case, a power outage, though network failure clearly doesn’t cause the hard drive failures nor vice versa.

The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum

by

Temple Grandin

and

Richard Panek

Published 15 Feb 2013

Oral stereotypies are common in all grazing animals, because that’s what they do all day. They graze. Other ARBs—rocking, repetitive jumping, and so on, or “non-locomotory body movements.” The zoo animals I call the “big pretty animals”—the big predators such as the lions, tigers, and bears—pace. Ungulates, which are the hoofed animals—horses, cows, rhinoceroses, pigs, zebras, llamas—do stereotypies with their mouths. Most of the other animals, including primates and lab rats, develop movement stereotypies in the third category. In human disorders such as autism, the abnormal behavior is usually in the first or third category. One of the most extreme cases of stereotypy I’ve ever seen was in a female wolf I saw at a wolf shelter.

Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take It Back

by

Oliver Bullough

Published 5 Sep 2018

And why, as Cole had asked him when that first ambulance attended his house, if he had such a quintessentially English name, did he sound so very Russian? But these were tiny details only picked up later. Any doctor will tell you that the guiding mantra for dealing with newly arrived patients is that common things are common. If you see hoof prints, think horses, not zebras; if you see an otherwise healthy man vomiting and suffering from diarrhoea, think gastroenteritis, not assassination ordered at the highest levels of a foreign government. The next morning, Carter was started on ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic that would combat any nasty bugs that were upsetting his stomach.

Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick

by

Maya Dusenbery

Published 6 Mar 2018

On average, it takes them over seven years to be correctly diagnosed. Along the way, these patients visit four primary care doctors and four specialists and receive two to three misdiagnoses. That it takes longer to be diagnosed with a rare disease than a more common one is not surprising. Doctors are taught that when they hear hoofbeats, they should think of horses, not zebras, and it may take some time to rule out more likely conditions and realize that they may, in fact, be looking at a zebra. But this staggering seven-year delay is decidedly not simply because it takes that long for doctors to crack a challenging case. According to a survey of 12,000 patients with several rare diseases in Europe, published by Eurordis in 2009, those who were initially misdiagnosed experienced longer diagnostic journeys.

Big Bang

by

Simon Singh

Published 1 Jan 2004

Applying Occam’s razor, you decide that the storm, rather than the twin meteorites, is the more likely explanation because it is the simpler one. Occam’s razor does not guarantee the right answer, but it does usually point us towards the correct one. Doctors often rely on Occam’s razor when diagnosing an illness, and medical students are advised: ‘When you hear hoof beats, think horses, not zebras.’ On the other hand, conspiracy theorists despise Occam’s razor, often rejecting a simple explanation in favour of a more convoluted and intriguing line of reasoning. Occam’s razor favoured the Copernican model (one circle per planet) over the Ptolemaic model (one epicycle, deferent, equant and eccentric per planet), but Occam’s razor is only decisive if two theories are equally successful, and in the sixteenth century the Ptolemaic model was clearly stronger in several ways; most notably, it made more accurate predictions of planetary positions.

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

by

Steven Pinker

Published 14 Oct 2021

And translated into common sense, it works like this. Now that you’ve seen the evidence, how much should you believe the idea? First, believe it more if the idea was well supported, credible, or plausible to start with—if it has a high prior, the first term in the numerator. As they say to medical students, if you hear hoofbeats outside the window, it’s probably a horse, not a zebra. If you see a patient with muscle aches, he’s more likely to have the flu than kuru (a rare disease seen among the Fore tribe in New Guinea), even if the symptoms are consistent with both diseases. Second, believe the idea more if the evidence is especially likely to occur when the idea is true—namely if it has a high likelihood, the second term in the numerator.

The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really True

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 3 Oct 2011

Code Complete (Developer Best Practices)

by

Steve McConnell

Published 8 Jun 2004

A pair of studies performed many years ago found that, of total errors reported, roughly 95% are caused by programmers, 2% by systems software (the compiler and the operating system), 2% by some other software, and 1% by the hardware (Brown and Sampson 1973, Ostrand and Weyuker 1984). Systems software and development tools are used by many more people today than they were in the 1970s and 1980s, and so my best guess is that, today, an even higher percentage of errors are the programmers' fault. If you see hoof prints, think horses—not zebras. The OS is probably not broken. And the database is probably just fine. — Andy Hunt Dave Thomas Clerical errors (typos) are a surprisingly common source of problems. One study found that 36% of all construction errors were clerical mistakes (Weiss 1975). A 1987 study of almost 3 million lines of flight-dynamics software found that 18% of all errors were clerical (Card 1987).

The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 21 Sep 2009

Similarly, impalas and gnus* are close cousins of each other, and slightly more distant cousins of giraffes and okapis. All four of them are more distant cousins still of other cloven-hoofed animals, such as pigs and warthogs (which are cousins of each other and of peccaries). All the cloven-hoofed animals are more distant cousins of horses and zebras (which don’t have cloven hooves and are close cousins of each other). We can go on as long as we like, bracketing pairs of cousins into groups, and groups of groups of cousins, and (groups of (groups of (groups of cousins))). I have slipped into using brackets automatically, and you know just what they signify.

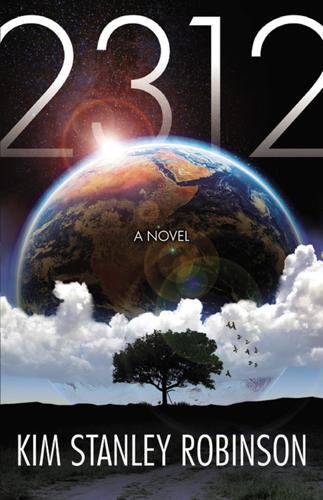

2312

by

Kim Stanley Robinson

Published 22 May 2012