Trillions: How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever

by Robin Wigglesworth · 11 Oct 2021 · 432pp · 106,612 words

the Leuthold Group Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Wigglesworth, Robin, author. Title: Trillions : how a band of Wall Street renegades invented the index fund and changed finance forever / Robin Wigglesworth. Description: New York : Portfolio, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2021027549 (print) | LCCN 2021027550 (ebook) | ISBN

…

Prizes of some of his Chicago contemporaries, his contributions to the intellectual ferment of the university’s economics department—and, ultimately, the invention of the index fund—are undeniable. * * * ♦ BORN IN 1922 IN KANSAS CITY, the horse-loving, backgammon enthusiast21 Lorie combined a genial temperament and a love for jokes—Johnny

…

, as it reflects the optimal tradeoff between risks and returns. This laid the intellectual groundwork for the coming invention of the index fund. Sharpe never made explicit mention of any index funds—after all, none had been invented yet, and he was unaware of the radical Renshaw paper proposing an “unmanaged investment company

…

Leuthold Group, a Minneapolis-based financial research group, famously distributed a poster where Uncle Sam declared, “Help stamp out index funds. Index funds are un-American!” Copies continue to float around the offices of index fund managers as mementos of the hostility they initially faced. Of course, as the writer Upton Sinclair once observed, it is

…

decades and reshaped their industry, and, in some minds, perhaps even capitalism itself. Many acquaintances called Bogle “messianic” over his titanic crusade on behalf of index funds and the cultlike environment he inculcated at Vanguard. Others preferred “iron-willed,” recalling how he would rarely yield in an argument. He preferred “determined,” the

…

great-grandfather Philander B. Armstrong, an insurance executive who railed against the industry’s anticonsumer practices in the nineteenth century2—Bogle was not always the index fund zealot he ultimately became. Initially, he was entranced by the professional investing industry that was blossoming as he entered adulthood. At the time of writing

…

simple product for the masses undoubtedly resonated. Nonetheless, despite Bogle’s later emergence as the leading champion of passive investing, the birth of the first index fund for ordinary everyday investors—an innovation that would ultimately upend the entire investment industry—was simply a result of Vanguard’s hamstrung circumstances and his

…

board accepted this tenuous logic and approved the proposal. The game was on. * * * ♦ TO GET A BETTER UNDERSTANDING of what was needed to run an index fund, Twardowski reached out to John McQuown at Wells Fargo, Rex Sinquefield at American National Bank, and Dean LeBaron at Batterymarch. Sinquefield proved particularly helpful to

…

Time Is Coming.” It explored the intellectual underpinnings, detailed the poor performance of most fund managers, explained the initial pioneering efforts, and presciently argued that “index funds now threaten to reshape the entire world of professional money management.”16 In August, Samuelson in Newsweek noted with delight the response to his challenge

…

Investment Trust.” However, the initial optimism faded when the brokerages took Bogle and Riepe on a roadshow to talk to their clients around the country. Index funds might have been trendy among the financial cognoscenti of Chicago, but financial advisors and ordinary investors in Buffalo or Minneapolis were noticeably less enthusiastic. By

…

tracking nearly everything.” Finally, ordinary savers were following in the footsteps of pension funds and directly benefiting from the cheapness—and better average performance—of index funds. The billions of dollars that had historically flowed into the pockets of Wall Street’s well-heeled denizens were finally staying a little more in

…

in 1983. But Sauter set about writing new trading programs in his spare time that reduced trading costs and improved how well the index funds tracked their benchmarks. When index funds finally started to grow dramatically in the early 1990s—accounting for over a tenth of Vanguard’s assets by 199113—Bogle refocused on

…

somewhat controversial. Nonetheless, the origin story of index investing is still incomplete. If Wells Fargo’s Management Sciences unit was the original Manhattan Project of index funds, most of the subsequent iterations were important but arguably incremental. They mostly consisted of proliferation, of spreading the approach to new corners of the investment

…

proves to be the most successful investment idea of the century remains to be seen.” * * * ♦ LIKE MANY OF HIS PREDECESSORS in the history of index funds, Most was an unlikely revolutionary. A cerebral, almost painfully modest former physicist, he stumbled into the finance industry late in life, after a peripatetic career

…

ran aground. Moreover, the Amex was not the only struggling exchange desperate for a commercial boost and aware of the immense potential of a tradable index fund. * * * ♦ THE PHILADELPHIA STOCK EXCHANGE WAS America’s oldest, founded in 1790 and instrumental in raising money for the nineteenth-century railroad boom. But New

…

financial system, the consequences of passive funds accounting for more and more of the global investment industry, and the narrowing club of titans dominating the index fund business. Chapter 15 PURDEY SHOTGUNS FAITH HAD ALWAYS BEEN CENTRAL to the life of Robert Netzly, sustaining him through a tough childhood and an itinerant

…

by its members.7 There are thousands more being maintained by various banks, which construct them to produce bespoke investment products for their clients, and index fund companies making their own to avoid paying the chunky licensing fees to the major index providers—something dubbed “self-indexing.”* In contrast, there are

…

”—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—and many of their smaller rivals have eschewed these, concerned that these more niche, complex products may tarnish the entire index fund universe. * * * ♦ IN EARLY 2018, THE STOCK MARKET was basking in the afterglow of President Donald Trump’s corporate tax cut, which had added at

…

vehicles, which means that they rarely amass huge assets compared to their plain-vanilla peers. * * * ♦ AFTER A RELENTLESS DECADE, there are signs that the index fund launch bonanza is slowing down. Most major tracts of industry real estate are now utterly and likely permanently controlled by a handful of big players

…

but the consequence was that the two stocks fluctuated wildly through January. Yet small, idiosyncratic instances such as these obscure the wider distortive impact of index funds, according to some skeptics. They fret that the undoubted benefits for many investors are increasingly outweighed by the more ephemeral costs to the overall health

…

OF THE NEGATIVE side effects are fairly uncontroversial, with only the degree and importance disputed by proponents and detractors of passive investing. Given that most index funds are capitalization-weighted, that means that most of the money they take in goes into the biggest stocks (or the largest debtors). Critically, and

…

wrong in almost every market disruption, especially in the weeks of March.” Similarly, despite frequent predictions of financial doom when the supposedly fickle inflows into index funds inevitably go into reverse, investment in them has time and again proven far “stickier” than money in traditional, active funds. “This suggests that the

…

. In other words, mathematically the market represents the average returns, and for every investor who outperforms the market someone must do worse. Given that index funds charge far less than traditional funds, over time the average passive investor must do better than the average active one. Other academics have later quibbled

…

still better than blindly allocating money according to the vagaries of an arbitrary index. Although the framing was deliberately provocative, it is undeniably true that index funds are free riders on the work done by active managers, which has an aggregate societal value—something even Jack Bogle admitted. If everyone merely

…

demanding stricter controls, and conservatives insisting that the immediate aftermath was a time for “thoughts and prayers,” not hasty action. But for the first time, index funds found themselves dragged into the tragedy, after activists pointed out that they were among the biggest owners of the biggest listed gun manufacturers. David Hogg

…

for plans on how to mitigate the risks posed by the proliferation of their firearms and prevent more tragedies like Parkland. They would also offer index funds that excluded gunmakers for any investors who wanted this. “For manufacturers and retailers of civilian firearms, we believe that responsible policies and practices are

…

onto passive investing instead. The main thrust of his incendiary letter was that corporate accountability has been declining for decades, and that the rise of index funds was exacerbating it.4 Whatever their investment merits, Singer argued that they constitute lazy, inattentive owners, who encourage corporate sloth and waste that in extremis

…

and sparked BlackRock’s new crusade. Yet this is not without potential pitfalls. No matter how worthy and important the issue, it will inevitably drag index fund providers into politically controversial territory. The biggest challenge in the coming era of passive investing will be to navigate the balance between being passive and

…

active owners, especially at a time of intense political and cultural polarization. For the index fund companies, the multitude of often conflicting attacks is frustrating. Barbara Novick, BlackRock’s steely former public policy supremo, has described their predicament as a

…

regulators, and economists on December 8, 2018. But the hearing, arranged by the Federal Trade Commission, tackled one of the most controversial theories dogging the index fund industry: “Common ownership.” The common ownership theory is that companies have fewer incentives to invest in new products or services, or to compete on price

…

to send their kids to university, to buy a house, or just for a rainy day indirectly or directly reaps the benefits of the humble index fund. Yes, index funds are subtly rewiring modern finance. But so did mutual funds before them, or the investment trusts before that. Despite legitimate concerns about the concentration

…

and Navy engineer who entered finance with an unusual amount of drive and love for computers. The combination proved vital when he launched the inaugural index fund at Wells Fargo. Onetime jock Gene Fama and his revolutionary efficient-markets hypothesis became synonymous with the University of Chicago and gave the intellectual cover

…

, Jack Bogle, Jim Norris. When David Booth, Rex Sinquefield, and Larry Klotz teamed up to start Dimensional Fund Advisors and run the next-generation of index funds, they enlisted their mentors John McQuown and Gene Fama to sit on their board. From left to right: McQuown, Klotz, Fama, Booth, Sinquefield. The

…

Hill Education, 2016), 7. 36. Charles D. Ellis, “The Loser’s Game,” Financial Analysts Journal, 1975. 37. Ian Liew, “SBBI: The Almanac of Returns Data,” Index Fund Advisors, July 19, 2019, www.ifa.com/articles/draft_dawn_creation_investing_science_bible_returns_data/. 38. Lorie, “Current Controversies on the Stock Market.” 39

…

the-King/. 12. Donald MacKenzie, An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 100. 13. Deborah Ziff Soriano, “Index Fund Pioneer Rex Sinquefield,” Chicago Booth Magazine, May 2019, www.chicagobooth.edu/magazine/rex-sinquefield-dimensional. 14. Margaret Towle, “Being First Is Best: An Adventure Capitalist

…

, NJ: Wiley, 2011), 105. 8. Mehrling, Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance, 101. 9. James Hagerty, “Bill Fouse Taught Skeptical Investors to Love Index Funds,” Wall Street Journal, October 31, 2019. 10. “William Lewis Fouse,” San Francisco Chronicle (obituary), October 17, 2019. 11. Robin Wigglesworth, “William Fouse, Quantitative Analyst,

…

MIT Press, 2006), 85. 19. Frank Fabozzi, Perspectives on Equity Indexing (New York: Wiley, 2000), 44. 20. Bernstein, Capital Ideas, 248. 21. Deborah Ziff Soriano, “Index Fund Pioneer Rex Sinquefield,” Chicago Booth Magazine, May 2019, www.chicagobooth.edu/magazine/rex-sinquefield-dimensional.” 22. Pensions & Investments, June 23, 1975. 23. Dean LeBaron, speech

…

Perspectives on Equity Indexing, 43 38. Institutional Investor, June 1977. 39. Institutional Investor, February 1976. 40. Fabozzi, Perspectives on Equity Indexing, 42. 41. Paul Samuelson, “Index-Fund Investing,” Newsweek, August 1976. CHAPTER 6: THE HEDGEHOG 1. Jack Bogle, Stay the Course: The Story of Vanguard and the Index Revolution (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

…

Dan Callahan, and Darius Majd, “Looking for Easy Games. How Passive Investing Shapes Active Management,” Credit Suisse, January 4, 2017. 25. Robin Wigglesworth, “Why the Index Fund ‘Bubble’ Should Be Applauded,” Financial Times, September 23, 2019. 26. Mary Childs, “Gary Shteyngart’s View from Hedge Fund Land,” Barron’s, September 7, 2018

…

. BlackRock, “BlackRock’s Approach to Companies That Manufacture and Distribute Civilian Firearms,” press release, March 2, 2018. 3. Jack Bogle, “Bogle Sounds a Warning on Index Funds,” Wall Street Journal, November 29, 2018. 4. Simone Foxman, “Paul Singer Says Passive Investing Is ‘Devouring Capitalism,’ ” Bloomberg, August 3, 2017. 5. Bill McNabb, “

…

29, 2019. 17. José Azar, Martin Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu, “Anti-competitive Effects of Common Ownership,” Journal of Finance, May 2018. 18. Frank Partnoy, “Are Index Funds Evil?,” Atlantic, September 2017. 19. Brooke Fox and Robin Wigglesworth, “Common Ownership of Shares Faces Regulatory Scrutiny,” Financial Times, January 22, 2019. 20. McLaughlin and

…

Massa, “The Hidden Dangers of the Great Index Fund Takeover.” 21. Marc Israel, “Renewed Focus on Common Ownership,” White & Case LLP, May 18, 2018. 22. Einer Elhauge, “How Horizontal Shareholding Harms Our Economy—

…

American Express Asset Management, 68, 79–80 American Import Company, 169–70 American National Bank, 53, 63–65, 78–81, 144 first S&P 500 index fund, 64–65, 78–79 American Savings and Loan, 211 American Statistical Society, 31 American Stock Exchange (Amex) acquisition by NYSE, 182–83 derivatives and,

My Start-Up Life: What A

by Ben Casnocha and Marc Benioff · 7 May 2007 · 207pp · 63,071 words

excite you. Online: Find out about charities that are changing the world. Day 13. Build a smart “personal finance infrastructure.” Start saving money. Invest in index funds. Keep and track a budget. Get wealthy. Online: Personal finance 101. Day 14. Write a blog. Put yourself out there. Share your ideas. Disclose yourself

Turning the Flywheel: A Monograph to Accompany Good to Great

by Jim Collins · 26 Feb 2019 · 44pp · 12,675 words

mindlessly repeating what you’ve done before. It means evolving, expanding, extending. It doesn’t mean just offering Jack Bogle’s revolutionary S&P 500 index fund; it means creating a plethora of low-cost funds in a wide range of asset categories that fit within the Vanguard flywheel. It doesn’t

Money in the Metaverse: Digital Assets, Online Identities, Spatial Computing and Why Virtual Worlds Mean Real Business

by David G. W. Birch and Victoria Richardson · 28 Apr 2024 · 249pp · 74,201 words

2023). Over the last five years, it provided a return of 4.9%, trailing the five-year return of Vanguard’s benchmark S&P 500 index fund (11.78%) and, for further comparison, two large actively managed funds (the American Funds Growth Fund of America, at 9.81%, and Fidelity’s Contrafund

The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America's Wealthy

by Thomas Stanley and William Danko · 15 Nov 2010 · 273pp · 78,850 words

over time. Small amounts invested periodically also become large investments over time. What if the Friends had invested their cigarette money in the stock market (index fund) during their lifetimes? How much would it have been worth? Nearly $100,000. And what if they had used their cigarette money to purchase shares

The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts

by Shane Parrish · 22 Nov 2019 · 147pp · 39,910 words

words, our advisor made more money by giving us one set of advice than another, regardless of its wisdom. Fortunately, the rise of things like index funds of the stock and bond markets has mostly alleviated the issue. In cases like financial advisory, we’re not on solid ground until we know

…

through the achievement of a positive outcome, we could ask ourselves how we might achieve a terrible outcome, and let that guide our decision-making. Index funds are a great example of stock market inversion promoted and brought to bear by Vanguard’s John Bogle.9 Instead of asking how to beat

…

help investors minimize losses to fees and poor money manager selection? The results were one of the greatest ideas—index funds—and one of the greatest powerhouse firms in the history of finance. The index fund operates on the idea that accruing wealth has a lot to do with minimizing loss. Think about your

Shape: The Hidden Geometry of Information, Biology, Strategy, Democracy, and Everything Else

by Jordan Ellenberg · 14 May 2021 · 665pp · 159,350 words

’s endless flitting. Don’t waste your time trying to time the market’s ups and downs; instead, Malkiel says, park your money in an index fund and forget about it. No amount of thought can predict the mosquito’s next move and provide you an advantage. Or, as Bachelier wrote in

Billion Dollar Loser: The Epic Rise and Spectacular Fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork

by Reeves Wiedeman · 19 Oct 2020 · 303pp · 100,516 words

career. Low interest rates enabled speculative investors to fund risky bets that could produce outsize returns. Individual investors were putting more of their money into index funds, which broadly tracked the economy, leaving mutual fund managers seeking alternatives to prove they could beat a market that was already booming. At the end

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

by Cal Newport · 5 Feb 2019 · 279pp · 71,542 words

meet are lower. If you need only $30,000 take-home pay to live comfortably, for example, then saving $750,000 in a low-cost index fund will likely cover these expenses (with inflation adjustments) for decades. Now imagine that you’re a young couple with two good salaries that generate $100

Circle of Greed: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Lawyer Who Brought Corporate America to Its Knees

by Patrick Dillon and Carl M. Cannon · 2 Mar 2010 · 613pp · 181,605 words

the office of the treasurer of the 180,000-member University of California Retirement Fund electronically purchased 200,000 shares of Enron stock through an index fund at an average price of $73 per share. This was just months after a portfolio manager in the same office, alerted by Enron’s ebullient

Having and Being Had

by Eula Biss · 15 Jan 2020 · 199pp · 61,648 words

Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction

by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner · 14 Sep 2015 · 317pp · 100,414 words

The Wealth Ladder: Proven Strategies for Every Step of Your Financial Life

by Nick Maggiulli · 22 Jul 2025

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by Ozan Varol · 13 Apr 2020 · 389pp · 112,319 words

The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer

by Dean Baker · 15 Jul 2006 · 234pp · 53,078 words

The Rough Guide to New York City

by Rough Guides · 21 May 2018

The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World's Most Coveted Microchip

by Stephen Witt · 8 Apr 2025 · 260pp · 82,629 words

Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us About Economics and Life

by Alan B. Krueger · 3 Jun 2019

Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity

by Charles L. Marohn, Jr. · 24 Sep 2019 · 242pp · 71,943 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart Contracts

by David Gerard · 23 Jul 2017 · 309pp · 54,839 words

Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines

by Thomas H. Davenport and Julia Kirby · 23 May 2016 · 347pp · 97,721 words

Seriously Curious: The Facts and Figures That Turn Our World Upside Down

by Tom Standage · 27 Nov 2018 · 215pp · 59,188 words

The Impossible Climb: Alex Honnold, El Capitan, and the Climbing Life

by Mark Synnott · 5 Mar 2019 · 389pp · 131,688 words

The Middleman Economy: How Brokers, Agents, Dealers, and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit

by Marina Krakovsky · 14 Sep 2015 · 270pp · 79,180 words

After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

by Tripp Mickle · 2 May 2022 · 535pp · 149,752 words

Exit Strategy

by Sherry Walling, Rob Walling · 22 Nov 2024 · 215pp · 60,241 words

Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 26 Mar 2013 · 316pp · 94,886 words

Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success

by Shane Snow · 8 Sep 2014 · 278pp · 70,416 words

Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices

by Robert McNally · 17 Jan 2017 · 436pp · 114,278 words

Kings of Crypto: One Startup's Quest to Take Cryptocurrency Out of Silicon Valley and Onto Wall Street

by Jeff John Roberts · 15 Dec 2020 · 226pp · 65,516 words

The Chairman's Lounge: The inside story of how Qantas sold us out

by Joe Aston · 27 Oct 2024 · 362pp · 130,141 words

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

Buffett

by Roger Lowenstein · 24 Jul 2013 · 612pp · 179,328 words

How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance

by Parag Khanna · 11 Jan 2011 · 251pp · 76,868 words

The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date

by Samuel Arbesman · 31 Aug 2012 · 284pp · 79,265 words

The Great Fragmentation: And Why the Future of All Business Is Small

by Steve Sammartino · 25 Jun 2014 · 247pp · 81,135 words

Oil: Money, Politics, and Power in the 21st Century

by Tom Bower · 1 Jan 2009 · 554pp · 168,114 words

Flash Boys: Not So Fast: An Insider's Perspective on High-Frequency Trading

by Peter Kovac · 10 Dec 2014 · 200pp · 54,897 words

Chokepoint Capitalism

by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow · 26 Sep 2022 · 396pp · 113,613 words

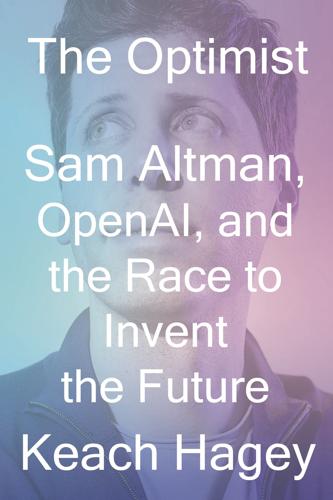

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by Keach Hagey · 19 May 2025 · 439pp · 125,379 words

The Equality Machine: Harnessing Digital Technology for a Brighter, More Inclusive Future

by Orly Lobel · 17 Oct 2022 · 370pp · 112,809 words

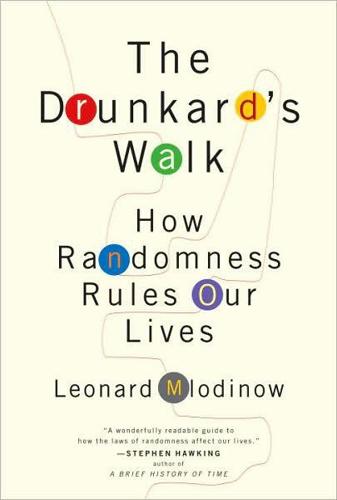

The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives

by Leonard Mlodinow · 12 May 2008 · 266pp · 86,324 words

The Soul of Wealth

by Daniel Crosby · 19 Sep 2024 · 229pp · 73,085 words

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation That Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe

by William Poundstone · 3 Jun 2019 · 283pp · 81,376 words

The Launch Pad: Inside Y Combinator, Silicon Valley's Most Exclusive School for Startups

by Randall Stross · 4 Sep 2013 · 332pp · 97,325 words

Tribe of Mentors: Short Life Advice From the Best in the World

by Timothy Ferriss · 14 Jun 2017 · 579pp · 183,063 words

Super Founders: What Data Reveals About Billion-Dollar Startups

by Ali Tamaseb · 14 Sep 2021 · 251pp · 80,831 words

Early Retirement Extreme

by Jacob Lund Fisker · 30 Sep 2010 · 346pp · 102,625 words

The New Rules of War: Victory in the Age of Durable Disorder

by Sean McFate · 22 Jan 2019 · 330pp · 83,319 words

The Broken Ladder

by Keith Payne · 8 May 2017

Inner Entrepreneur: A Proven Path to Profit and Peace

by Grant Sabatier · 10 Mar 2025 · 442pp · 126,902 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism

by Robin Chase · 14 May 2015 · 330pp · 91,805 words

Money Moments: Simple Steps to Financial Well-Being

by Jason Butler · 22 Nov 2017 · 139pp · 33,246 words

Company of One: Why Staying Small Is the Next Big Thing for Business

by Paul Jarvis · 1 Jan 2019 · 258pp · 74,942 words

The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America

by Warren E. Buffett and Lawrence A. Cunningham · 2 Jan 1997 · 219pp · 15,438 words

Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant

by W. Chan Kim and Renée A. Mauborgne · 20 Jan 2014 · 287pp · 80,180 words

Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet

by Varun Sivaram · 2 Mar 2018 · 469pp · 132,438 words

Fall; Or, Dodge in Hell

by Neal Stephenson · 3 Jun 2019 · 993pp · 318,161 words

The Automatic Millionaire, Expanded and Updated: A Powerful One-Step Plan to Live and Finish Rich

by David Bach · 27 Dec 2016 · 201pp · 62,593 words

Hunger: The Oldest Problem

by Martin Caparros · 14 Jan 2020 · 684pp · 212,486 words

Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings

by Philip A. Fisher · 13 Apr 2015

Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All

by Michael Shellenberger · 28 Jun 2020

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton

by Colin Read · 16 Jul 2012 · 206pp · 70,924 words

The Cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion

by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell · 19 Jul 2021 · 460pp · 130,820 words

Willful: How We Choose What We Do

by Richard Robb · 12 Nov 2019 · 202pp · 58,823 words

You've Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All

by Adrian Hon · 14 Sep 2022 · 371pp · 107,141 words

The Elements of Choice: Why the Way We Decide Matters

by Eric J. Johnson · 12 Oct 2021 · 362pp · 103,087 words

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski · 5 Mar 2019 · 202pp · 62,901 words

The Dark Cloud: How the Digital World Is Costing the Earth

by Guillaume Pitron · 14 Jun 2023 · 271pp · 79,355 words

Nobody's Fool: Why We Get Taken in and What We Can Do About It

by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris · 10 Jul 2023 · 338pp · 104,815 words

The Capitalist Manifesto

by Johan Norberg · 14 Jun 2023 · 295pp · 87,204 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Life After Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy

by George Gilder · 16 Jul 2018 · 332pp · 93,672 words

The Transhumanist Reader

by Max More and Natasha Vita-More · 4 Mar 2013 · 798pp · 240,182 words

Meet the Frugalwoods: Achieving Financial Independence Through Simple Living

by Elizabeth Willard Thames · 6 Mar 2018 · 179pp · 59,704 words

Optimization Methods in Finance

by Gerard Cornuejols and Reha Tutuncu · 2 Jan 2006 · 130pp · 11,880 words

SUPERHUBS: How the Financial Elite and Their Networks Rule Our World

by Sandra Navidi · 24 Jan 2017 · 831pp · 98,409 words

Rationality: From AI to Zombies

by Eliezer Yudkowsky · 11 Mar 2015 · 1,737pp · 491,616 words

The Bank That Lived a Little: Barclays in the Age of the Very Free Market

by Philip Augar · 4 Jul 2018 · 457pp · 143,967 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Woke, Inc: Inside Corporate America's Social Justice Scam

by Vivek Ramaswamy · 16 Aug 2021 · 344pp · 104,522 words

The Art of Execution: How the World's Best Investors Get It Wrong and Still Make Millions

by Lee Freeman-Shor · 8 Sep 2015 · 121pp · 31,813 words

AIQ: How People and Machines Are Smarter Together

by Nick Polson and James Scott · 14 May 2018 · 301pp · 85,126 words

The 5 Types of Wealth: A Transformative Guide to Design Your Dream Life

by Sahil Bloom · 4 Feb 2025 · 363pp · 94,341 words

A Hacker's Mind: How the Powerful Bend Society's Rules, and How to Bend Them Back

by Bruce Schneier · 7 Feb 2023 · 306pp · 82,909 words

Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

by Jeff Gramm · 23 Feb 2016 · 384pp · 103,658 words

The Little Book of Hedge Funds

by Anthony Scaramucci · 30 Apr 2012 · 162pp · 50,108 words

Early Retirement Guide: 40 is the new 65

by Manish Thakur · 20 Dec 2015

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber · 29 Oct 2024 · 292pp · 106,826 words

The End of Indexing: Six Structural Mega-Trends That Threaten Passive Investing

by Niels Jensen · 25 Mar 2018 · 205pp · 55,435 words

The Founders: The Story of Paypal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

by Jimmy Soni · 22 Feb 2022 · 505pp · 161,581 words

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World

by Daniel Yergin · 14 May 2011 · 1,373pp · 300,577 words

Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make a Difference

by William MacAskill · 27 Jul 2015 · 293pp · 81,183 words

Brazillionaires: The Godfathers of Modern Brazil

by Alex Cuadros · 1 Jun 2016 · 433pp · 125,031 words

The Land Grabbers: The New Fight Over Who Owns the Earth

by Fred Pearce · 28 May 2012 · 379pp · 114,807 words

The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine

by Michael Lewis · 1 Nov 2009 · 265pp · 93,231 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Mar 2016 · 366pp · 94,209 words

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

Open: The Progressive Case for Free Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital

by Kimberly Clausing · 4 Mar 2019 · 555pp · 80,635 words

The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution

by Gregory Zuckerman · 5 Nov 2019 · 407pp · 104,622 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

Extreme Early Retirement: An Introduction and Guide to Financial Independence (Retirement Books)

by Clayton Geoffreys · 16 May 2015 · 44pp · 13,346 words

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by Nate Silver · 12 Aug 2024 · 848pp · 227,015 words

925 Ideas to Help You Save Money, Get Out of Debt and Retire a Millionaire So You Can Leave Your Mark on the World

by Devin D. Thorpe · 25 Nov 2012 · 263pp · 89,368 words

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel · 7 Sep 2020 · 209pp · 53,175 words

No Ordinary Disruption: The Four Global Forces Breaking All the Trends

by Richard Dobbs and James Manyika · 12 May 2015 · 389pp · 87,758 words

Wall Street Meat

by Andy Kessler · 17 Mar 2003 · 270pp · 75,803 words

The Oil Factor: Protect Yourself-and Profit-from the Coming Energy Crisis

by Stephen Leeb and Donna Leeb · 12 Feb 2004 · 222pp · 70,559 words

Better, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline . . . And the Rise of a New Economy

by Daniel Gross · 7 May 2012 · 391pp · 97,018 words

The Behavioral Investor

by Daniel Crosby · 15 Feb 2018 · 249pp · 77,342 words

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by David Hale and Lyric Hughes Hale · 23 May 2011 · 397pp · 112,034 words

One Up on Wall Street

by Peter Lynch · 11 May 2012

Ethics in Investment Banking

by John N. Reynolds and Edmund Newell · 8 Nov 2011 · 193pp · 11,060 words

The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers (Wiley Finance)

by Feng Gu · 26 Jun 2016

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Apr 2008 · 304pp · 22,886 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

The Einstein of Money: The Life and Timeless Financial Wisdom of Benjamin Graham

by Joe Carlen · 14 Apr 2012 · 398pp · 111,333 words

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It

by Scott Kupor · 3 Jun 2019 · 340pp · 100,151 words

Fortune's Formula: The Untold Story of the Scientific Betting System That Beat the Casinos and Wall Street

by William Poundstone · 18 Sep 2006 · 389pp · 109,207 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

Dead Companies Walking

by Scott Fearon · 10 Nov 2014 · 232pp · 71,965 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Retrofitting Suburbia, Updated Edition: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs

by Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson · 23 Mar 2011 · 512pp · 131,112 words

The Scandal of Money

by George Gilder · 23 Feb 2016 · 209pp · 53,236 words

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

Practical Doomsday: A User's Guide to the End of the World

by Michal Zalewski · 11 Jan 2022 · 337pp · 96,666 words

Capital Allocators: How the World’s Elite Money Managers Lead and Invest

by Ted Seides · 23 Mar 2021 · 199pp · 48,162 words

Just Keep Buying: Proven Ways to Save Money and Build Your Wealth

by Nick Maggiulli · 15 May 2022 · 287pp · 62,824 words

The Tyranny of Nostalgia: Half a Century of British Economic Decline

by Russell Jones · 15 Jan 2023 · 463pp · 140,499 words

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World

by Brett Chistophers · 25 Apr 2023 · 404pp · 106,233 words

Chaos Kings: How Wall Street Traders Make Billions in the New Age of Crisis

by Scott Patterson · 5 Jun 2023 · 289pp · 95,046 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

100 Baggers: Stocks That Return 100-To-1 and How to Find Them

by Christopher W Mayer · 21 May 2018

Who Stole the American Dream?

by Hedrick Smith · 10 Sep 2012 · 598pp · 172,137 words

A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market

by John Allen Paulos · 1 Jan 2003 · 295pp · 66,824 words

Trade Your Way to Financial Freedom

by van K. Tharp · 1 Jan 1998

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by Nate Silver · 31 Aug 2012 · 829pp · 186,976 words

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by Richard R. Lindsey and Barry Schachter · 30 Jun 2007

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Quants

by Scott Patterson · 2 Feb 2010 · 374pp · 114,600 words

Fred Schwed's Where Are the Customers' Yachts?: A Modern-Day Interpretation of an Investment Classic

by Leo Gough · 22 Aug 2010 · 117pp · 31,221 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

Bernie Madoff, the Wizard of Lies: Inside the Infamous $65 Billion Swindle

by Diana B. Henriques · 1 Aug 2011 · 598pp · 169,194 words

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded)

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 1 Jan 2006 · 348pp · 83,490 words

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by William Baker and Addison Wiggin · 2 Nov 2009 · 444pp · 151,136 words

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

How Boards Work: And How They Can Work Better in a Chaotic World

by Dambisa Moyo · 3 May 2021 · 272pp · 76,154 words

Evidence-Based Technical Analysis: Applying the Scientific Method and Statistical Inference to Trading Signals

by David Aronson · 1 Nov 2006

Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Achieving Financial Independence: Revised and Updated for the 21st Century

by Vicki Robin, Joe Dominguez and Monique Tilford · 31 Aug 1992 · 426pp · 115,150 words

The Little Book That Still Beats the Market

by Joel Greenblatt · 2 Jan 2010 · 120pp · 39,637 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

Playing With FIRE (Financial Independence Retire Early): How Far Would You Go for Financial Freedom?

by Scott Rieckens and Mr. Money Mustache · 1 Jan 2019

Electronic and Algorithmic Trading Technology: The Complete Guide

by Kendall Kim · 31 May 2007 · 224pp · 13,238 words

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

Red-Blooded Risk: The Secret History of Wall Street

by Aaron Brown and Eric Kim · 10 Oct 2011 · 483pp · 141,836 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by Danielle Dimartino Booth · 14 Feb 2017 · 479pp · 113,510 words

The Misbehavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Financial Turbulence

by Benoit Mandelbrot and Richard L. Hudson · 7 Mar 2006 · 364pp · 101,286 words

Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World

by Christopher Steiner · 29 Aug 2012 · 317pp · 84,400 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

How to Predict the Unpredictable

by William Poundstone · 267pp · 71,941 words

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by John Kay · 2 Sep 2015 · 478pp · 126,416 words

Smart Money: How High-Stakes Financial Innovation Is Reshaping Our WorldÑFor the Better

by Andrew Palmer · 13 Apr 2015 · 280pp · 79,029 words

Alpha Trader

by Brent Donnelly · 11 May 2021

Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

by Bruce C. N. Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul D. Sonkin and Michael van Biema · 26 Jan 2004 · 306pp · 97,211 words

Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk

by Peter L. Bernstein · 23 Aug 1996 · 415pp · 125,089 words

The Barefoot Investor: The Only Money Guide You'll Ever Need

by Scott Pape · 22 Nov 2016 · 229pp · 64,697 words

Madoff Talks: Uncovering the Untold Story Behind the Most Notorious Ponzi Scheme in History

by Jim Campbell · 26 Apr 2021 · 369pp · 107,073 words

Quantitative Trading: How to Build Your Own Algorithmic Trading Business

by Ernie Chan · 17 Nov 2008

The Bond King: How One Man Made a Market, Built an Empire, and Lost It All

by Mary Childs · 15 Mar 2022 · 367pp · 110,161 words

The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets

by Thomas Philippon · 29 Oct 2019 · 401pp · 109,892 words

Two and Twenty: How the Masters of Private Equity Always Win

by Sachin Khajuria · 13 Jun 2022 · 229pp · 75,606 words

Damsel in Distressed: My Life in the Golden Age of Hedge Funds

by Dominique Mielle · 6 Sep 2021 · 195pp · 63,455 words

Unknown Market Wizards: The Best Traders You've Never Heard Of

by Jack D. Schwager · 2 Nov 2020

Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone

by John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai · 25 Jul 2025

Work Optional: Retire Early the Non-Penny-Pinching Way

by Tanja Hester · 12 Feb 2019 · 231pp · 76,283 words

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by Satyajit Das · 15 Nov 2006 · 349pp · 134,041 words

Quit Like a Millionaire: No Gimmicks, Luck, or Trust Fund Required

by Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung · 8 Jul 2019 · 389pp · 81,596 words

The Dhandho Investor: The Low-Risk Value Method to High Returns

by Mohnish Pabrai · 17 May 2009 · 172pp · 49,890 words

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

The Future of Money: How the Digital Revolution Is Transforming Currencies and Finance

by Eswar S. Prasad · 27 Sep 2021 · 661pp · 185,701 words

Irrational Exuberance: With a New Preface by the Author

by Robert J. Shiller · 15 Feb 2000 · 319pp · 106,772 words

Why Aren't They Shouting?: A Banker’s Tale of Change, Computers and Perpetual Crisis

by Kevin Rodgers · 13 Jul 2016 · 318pp · 99,524 words

Trend Following: How Great Traders Make Millions in Up or Down Markets

by Michael W. Covel · 19 Mar 2007 · 467pp · 154,960 words

Advanced Stochastic Models, Risk Assessment, and Portfolio Optimization: The Ideal Risk, Uncertainty, and Performance Measures

by Frank J. Fabozzi · 25 Feb 2008 · 923pp · 163,556 words

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite

by Sebastian Mallaby · 9 Jun 2010 · 584pp · 187,436 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

The greatest trade ever: the behind-the-scenes story of how John Paulson defied Wall Street and made financial history

by Gregory Zuckerman · 3 Nov 2009 · 342pp · 99,390 words

How the City Really Works: The Definitive Guide to Money and Investing in London's Square Mile

by Alexander Davidson · 1 Apr 2008 · 368pp · 32,950 words

Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton · 3 Feb 2002 · 353pp · 148,895 words

Pound Foolish: Exposing the Dark Side of the Personal Finance Industry

by Helaine Olen · 27 Dec 2012 · 375pp · 105,067 words

Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems

by Didier Sornette · 18 Nov 2002 · 442pp · 39,064 words

Your Money: The Missing Manual

by J.D. Roth · 18 Mar 2010 · 519pp · 118,095 words

Financial Freedom: A Proven Path to All the Money You Will Ever Need

by Grant Sabatier · 5 Feb 2019 · 621pp · 123,678 words

Inside the House of Money: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Profiting in a Global Market

by Steven Drobny · 31 Mar 2006 · 385pp · 128,358 words

What They Do With Your Money: How the Financial System Fails Us, and How to Fix It

by Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik and David Pitt-Watson · 30 Apr 2016 · 304pp · 80,965 words

Reset: How to Restart Your Life and Get F.U. Money: The Unconventional Early Retirement Plan for Midlife Careerists Who Want to Be Happy

by David Sawyer · 17 Aug 2018 · 572pp · 94,002 words

Rigged Money: Beating Wall Street at Its Own Game

by Lee Munson · 6 Dec 2011 · 236pp · 77,735 words

Money Mavericks: Confessions of a Hedge Fund Manager

by Lars Kroijer · 26 Jul 2010 · 244pp · 79,044 words

A Man for All Markets

by Edward O. Thorp · 15 Nov 2016 · 505pp · 142,118 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined

by Lasse Heje Pedersen · 12 Apr 2015 · 504pp · 139,137 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

Asset and Risk Management: Risk Oriented Finance

by Louis Esch, Robert Kieffer and Thierry Lopez · 28 Nov 2005 · 416pp · 39,022 words

Take the Money and Run: Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Demise of American Prosperity

by Eric C. Anderson · 15 Jan 2009 · 264pp · 115,489 words

The Dollar Meltdown: Surviving the Coming Currency Crisis With Gold, Oil, and Other Unconventional Investments

by Charles Goyette · 29 Oct 2009 · 287pp · 81,970 words

Big Mistakes: The Best Investors and Their Worst Investments

by Michael Batnick · 21 May 2018 · 198pp · 53,264 words

Nerds on Wall Street: Math, Machines and Wired Markets

by David J. Leinweber · 31 Dec 2008 · 402pp · 110,972 words

Toward Rational Exuberance: The Evolution of the Modern Stock Market

by B. Mark Smith · 1 Jan 2001 · 403pp · 119,206 words

Stock Market Wizards: Interviews With America's Top Stock Traders

by Jack D. Schwager · 1 Jan 2001

I Will Teach You To Be Rich

by Sethi, Ramit · 22 Mar 2009 · 357pp · 91,331 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

The Invisible Hands: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Bubbles, Crashes, and Real Money

by Steven Drobny · 18 Mar 2010 · 537pp · 144,318 words

A Wealth of Common Sense: Why Simplicity Trumps Complexity in Any Investment Plan

by Ben Carlson · 14 May 2015 · 232pp · 70,835 words

The Money Machine: How the City Works

by Philip Coggan · 1 Jul 2009 · 253pp · 79,214 words

Retire Before Mom and Dad

by Rob Berger · 10 Aug 2019 · 239pp · 60,065 words

file:///C:/Documents%20and%...

by vpavan

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies

by Tim Koller, McKinsey, Company Inc., Marc Goedhart, David Wessels, Barbara Schwimmer and Franziska Manoury · 16 Aug 2015 · 892pp · 91,000 words

The Secret Club That Runs the World: Inside the Fraternity of Commodity Traders

by Kate Kelly · 2 Jun 2014 · 289pp · 77,532 words

How I Invest My Money: Finance Experts Reveal How They Save, Spend, and Invest

by Brian Portnoy and Joshua Brown · 17 Nov 2020 · 149pp · 43,747 words

Buy Now, Pay Later: The Extraordinary Story of Afterpay

by Jonathan Shapiro and James Eyers · 2 Aug 2021 · 444pp · 124,631 words

Beyond Diversification: What Every Investor Needs to Know About Asset Allocation

by Sebastien Page · 4 Nov 2020 · 367pp · 97,136 words

Finding Alphas: A Quantitative Approach to Building Trading Strategies

by Igor Tulchinsky · 30 Sep 2019 · 321pp

Systematic Trading: A Unique New Method for Designing Trading and Investing Systems

by Robert Carver · 13 Sep 2015

The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions

by Victor Haghani and James White · 27 Aug 2023 · 314pp · 122,534 words

Concentrated Investing

by Allen C. Benello · 7 Dec 2016

The Handbook of Personal Wealth Management

by Reuvid, Jonathan. · 30 Oct 2011

The Revolution That Wasn't: GameStop, Reddit, and the Fleecing of Small Investors

by Spencer Jakab · 1 Feb 2022 · 420pp · 94,064 words

The Big Secret for the Small Investor: A New Route to Long-Term Investment Success

by Joel Greenblatt · 11 Apr 2011 · 89pp · 29,198 words

How to Own the World: A Plain English Guide to Thinking Globally and Investing Wisely

by Andrew Craig · 6 Sep 2015 · 305pp · 98,072 words

Cashing Out: Win the Wealth Game by Walking Away

by Julien Saunders and Kiersten Saunders · 13 Jun 2022 · 268pp · 64,786 words

Hedgehogging

by Barton Biggs · 3 Jan 2005

The Clash of the Cultures

by John C. Bogle · 30 Jun 2012 · 339pp · 109,331 words

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History

by Diana B. Henriques · 18 Sep 2017 · 526pp · 144,019 words

The Gone Fishin' Portfolio: Get Wise, Get Wealthy...and Get on With Your Life

by Alexander Green · 15 Sep 2008 · 244pp · 58,247 words

The New Science of Asset Allocation: Risk Management in a Multi-Asset World

by Thomas Schneeweis, Garry B. Crowder and Hossein Kazemi · 8 Mar 2010 · 317pp · 106,130 words

Capital Ideas Evolving

by Peter L. Bernstein · 3 May 2007

Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners

by Larry Harris · 2 Jan 2003 · 1,164pp · 309,327 words

The Permanent Portfolio

by Craig Rowland and J. M. Lawson · 27 Aug 2012

Beyond the Random Walk: A Guide to Stock Market Anomalies and Low Risk Investing

by Vijay Singal · 15 Jun 2004 · 369pp · 128,349 words

Personal Investing: The Missing Manual

by Bonnie Biafore, Amy E. Buttell and Carol Fabbri · 24 May 2010 · 250pp · 77,544 words

Commodity Trading Advisors: Risk, Performance Analysis, and Selection

by Greg N. Gregoriou, Vassilios Karavas, François-Serge Lhabitant and Fabrice Douglas Rouah · 23 Sep 2004

The Intelligent Investor (Collins Business Essentials)

by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig · 1 Jan 1949 · 670pp · 194,502 words

The Simple Path to Wealth: Your Road Map to Financial Independence and a Rich, Free Life

by J L Collins · 17 Jun 2016 · 194pp · 59,336 words

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy J. Siegel · 18 Dec 2007

Portfolio Design: A Modern Approach to Asset Allocation

by R. Marston · 29 Mar 2011 · 363pp · 28,546 words

Understanding Asset Allocation: An Intuitive Approach to Maximizing Your Portfolio

by Victor A. Canto · 2 Jan 2005 · 337pp · 89,075 words

Investing Demystified: How to Invest Without Speculation and Sleepless Nights

by Lars Kroijer · 5 Sep 2013 · 300pp · 77,787 words

The Investopedia Guide to Wall Speak: The Terms You Need to Know to Talk Like Cramer, Think Like Soros, and Buy Like Buffett

by Jack (edited By) Guinan · 27 Jul 2009 · 353pp · 88,376 words

The Intelligent Asset Allocator: How to Build Your Portfolio to Maximize Returns and Minimize Risk

by William J. Bernstein · 12 Oct 2000

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing (Eleventh Edition)

by Burton G. Malkiel · 5 Jan 2015 · 482pp · 121,672 words

The Bogleheads' Guide to Investing

by Taylor Larimore, Michael Leboeuf and Mel Lindauer · 1 Jan 2006 · 335pp · 94,657 words

Work Less, Live More: The Way to Semi-Retirement

by Robert Clyatt · 28 Sep 2007

The Smartest Investment Book You'll Ever Read: The Simple, Stress-Free Way to Reach Your Investment Goals

by Daniel R. Solin · 7 Nov 2006

Market Sense and Nonsense

by Jack D. Schwager · 5 Oct 2012 · 297pp · 91,141 words

All About Asset Allocation, Second Edition

by Richard Ferri · 11 Jul 2010

Expected Returns: An Investor's Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards

by Antti Ilmanen · 4 Apr 2011 · 1,088pp · 228,743 words

Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment

by David F. Swensen · 8 Aug 2005 · 490pp · 117,629 words

The Power of Passive Investing: More Wealth With Less Work

by Richard A. Ferri · 4 Nov 2010 · 345pp · 87,745 words

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy Siegel · 7 Jan 2014 · 517pp · 139,477 words

Hedge Fund Market Wizards

by Jack D. Schwager · 24 Apr 2012 · 272pp · 19,172 words

Principles of Corporate Finance

by Richard A. Brealey, Stewart C. Myers and Franklin Allen · 15 Feb 2014

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns

by John C. Bogle · 1 Jan 2007 · 356pp · 51,419 words

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom

by Tony Robbins · 18 Nov 2014 · 825pp · 228,141 words

A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing

by Burton G. Malkiel · 10 Jan 2011 · 416pp · 118,592 words

The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio

by William J. Bernstein · 26 Apr 2002 · 407pp · 114,478 words

The Simple Path to Wealth (Revised & Expanded 2025 Edition): Your Road Map to Financial Independence and a Rich, Free Life

by JL Collins · 191pp · 66,998 words

Investing Amid Low Expected Returns: Making the Most When Markets Offer the Least

by Antti Ilmanen · 24 Feb 2022

Heads I Win, Tails I Win

by Spencer Jakab · 21 Jun 2016 · 303pp · 84,023 words

Millionaire Teacher: The Nine Rules of Wealth You Should Have Learned in School

by Andrew Hallam · 1 Nov 2011 · 274pp · 60,596 words

Smarter Investing

by Tim Hale · 2 Sep 2014 · 332pp · 81,289 words