Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff Between Privacy and Security

by

Daniel J. Solove

Published 28 Jun 2011

During President Franklin Roosevelt’s tenure, the size of the FBI increased more than 1000 percent.12 It has continued to grow, tripling in size over the past sixty years.13 Despite its vast size, extensive and expanding responsibilities, and profound technological capabilities, the FBI still lacks the congressional authorizing statute that most other federal agencies have. The Growth of Electronic Surveillance The FBI came into being as the debate over surveillance of communications entered a new era. Telephone wiretapping technology appeared soon after the invention of the telephone in 1876, making the privacy of phone communications a public concern. State legislatures responded by passing laws criminalizing wiretapping. In 1928, in Olmstead v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment did not apply to wiretapping. “There was no searching,” the Supreme Court reasoned.

…

According to Kerr, courts, unlike legislatures, “cannot update rules quickly as technology shifts.”6 But Congress has failed in this regard as well. During the development of the Internet, email, and the dizzying array of other new technologies throughout the past quarter-century, Congress made only a few major revisions to electronic-surveillance law. And though the invention of the telephone and the rise of wiretapping occurred in the late nineteenth century, Congress didn’t regulate wiretapping until 1934. That statute quickly proved to be ineffective, and it accomplished the amazing feat of earning the scorn of privacy advocates as well as lawenforcement officials.7 Finally, in 1968, Congress reworked the law of wiretapping, and the law regulating the telephone was at long last in decent shape.

A Week at the Airport: A Heathrow Diary

by

Alain de Botton

Published 1 Jan 2009

asked Adam Smith in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), going on to answer, ‘To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency, and approbation’ – a set of ambitions to which the creators of the Concorde Room had responded with stirring precision. As I took a seat in the restaurant, I felt certain that whatever it had taken for humanity to arrive at this point had ultimately been worth it. The development of the combustion engine, the invention of the telephone, the Second World War, the introduction of real-time financial information on Reuters screens, the Bay of Pigs, the extinction of the slender-billed curlew – all of these things had, each in its own fashion, helped to pave the way for a disparate group of uniformly attractive individuals to silently mingle in a splendid room with a view of a runway in a cloud-bedecked corner of the Western world.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by

Robert J. Gordon

Published 12 Jan 2016

Throughout the 1890–1915 period, when RFD became universal, political pressure was generated for better roads, supporting the view that better roads made the automobile possible as much as the automobile created the demand for rural roads. “NUMBER, PLEASE” AS THE TELEPHONE ARRIVES Like the 1879 invention of electric light discussed in chapter 4 or the nearly simultaneous invention of the internal combustion engine summarized in chapter 5, the invention of the telephone had been preceded by several decades of speculation and experimentation. But the gestation period for the telephone was shorter; its 1876 invention occurred only twenty-two years after Philip Reis’s idea, in 1854, that a flexible plate vibrating in response to air pressure changes created by the human voice could open and close an electric circuit.22 Further progress was limited by the inability to provide the variable pitch and tone of the human voice rather than the simple on-off alternation created by the telegraphic switch.

…

How rapidly did household use of the phonograph grow in comparison with the telephone and the radio? Figure 6–4 compares the number of phonographs per household with the number of residential telephones per household.50 The race between the telephone and phonograph was surprisingly close. Note that fully fifty years elapsed between the nearly simultaneous invention of the telephone and phonograph and the date when they were present in half of American homes. Figure 6–4 also contrasts the very different pattern of telephone and radio use in the 1930s, when the percentage of households that had telephones declined from 45 percent in 1929 to 33 percent in 1933. Because telephones were rented rather than bought outright, phones simply disappeared from homes in which the Depression had slashed incomes so much that the telephone bill could not be paid.

…

Perhaps no other profession than the medical doctors embraced the automobile so enthusiastically. “Besides making house calls in one-half the time,” wrote a physician from Oklahoma, “there is something about the auto that is infatuating, and the more you ride the more you want to ride.”66 Medical care provides an example of the consumer benefits of the invention of the telephone. Before the telephone reached the farm, extra travel was required by a relative or friend of the patient who had to go and fetch the doctor in person. In many cases, the doctor could not be found because he was out on another call, and the emissary would have to wait or frantically try to find out where the doctor had traveled.

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

by

Nir Eyal

Published 26 Dec 2013

A striking number of world-changing innovations were written off as mere novelties with limited commercial appeal. George Eastman’s Brownie camera, preloaded with a film roll and selling for just $1, was originally marketed as a child’s toy.5 Established studio photographers saw the device as little more than a cheap plaything. The invention of the telephone was also dismissed at first. Sir William Henry Preece, the chief engineer of the British post office, famously declared, “The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.”6 In 1911 Ferdinand Foch, the future commander in chief of the Allied forces in World War I, said, “Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value.”7 In 1957 the editor of business books for Prentice Hall told his publisher, “I have traveled the length and breadth of this country and talked with the best people, and I can assure you that data processing is a fad that won’t last out the year.”

Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly

by

John Kay

Published 30 Apr 2010

The Japanese approach to Singapore from the landward side was both direct and oblique, and the eventual attack could then be direct. The oblique, unaccustomed perspective was how Brunelleschi cracked the egg, built the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore and discovered how to represent perspective. Many great achievements are of this kind. Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone, like Akio Morita’s creation of the Sony Walkman and Steve Jobs’s reinterpretation of Morita’s idea in the iPod, was a solution to a problem people did not know they had. It is hard to overstate the damage done recently by people who thought they knew more about the world than they really did.

Victorian Internet

by

Tom Standage

Published 1 Jan 1998

Electrical signals produced by the reeds would be combined, sent down a telegraph wire, and then separated out again at the other end using an identical set of reeds, each of which would respond only to the signals generated by its counterpart. Morse telegraphy would then be possible by stopping and starting the vibration of each reed to make dots and dashes. Elisha Gray, the inventor whose work on a harmonic telegraph contributed to the invention of the telephone. Elisha Gray, one of those working on a harmonic telegraph, produced a design that he believed would be capable of carrying sixteen messages along a single wire. But when he tested his design, he found that in practice only six separate signals could be sent reliably. Nevertheless, Gray was confident that he would eventually be able to improve his apparatus.

The Decline and Fall of IBM: End of an American Icon?

by

Robert X. Cringely

Published 1 Jun 2014

bojennett December 21, 2011 9:01 am Apple on the offense “You are right about the well-documented industrials of the past that go on uncontrolled (albeit slow) death spirals for they could ‘a this or should ‘a that, but didn’t – Digital anyone? U.S. Steel? Western Union on A.G. Bell’s invention of the telephone? All those losers have one thing in common – they were all defensive and not offensive. Apple, for example, is obviously offensive in nature. They try to out-innovate anyone who tries to get near. Being as offensive as Apple relegates an existing market to obsolescence just when startups and competitors start to catch up.

How We Got Here: A Slightly Irreverent History of Technology and Markets

by

Andy Kessler

Published 13 Jun 2005

., and in 1873, when the North Pacific failed so did Jay Cooke, and the Panic of 1873 whipped through the country. Wall Street reemerged yet again from this financial crisis, but this time insisted on even more information, not just stock prices, but news from companies, so it could figure out what to fund, and what not to fund. It got what it was looking for with the invention of the telephone. 1878 saw telephones on the floor of the exchange, when a specialist picked up a phone and said “buy-bid-‘em-up-sell.” In the 19th century, the U.S. population was growing like a weed, filling in the wide-open spaces out West, and following the British industrialization, albeit with a 50-year lag.

Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centres

by

Jamie Woodcock

Published 20 Nov 2016

The authors themselves are quite vague about the history of call centres, writing, ‘although we can’t really tell you when the first call center opened, we imagine that call centers started around the time that the telephone became a common household device . . . the evolution of call centers just makes sense’.22 11 Working the Phones This common sense point about the development of call centres is useful; however, as with many phenomena, it is important to go beyond the conclusion that something happened because it ‘just makes sense’. A logical starting point is the invention of the telephone. The telephone is one of a number of technologies – alongside the automobile, the television, the computer and so on – that have had a far-reaching social impact on modern society. Claude S. Fischer argues that the telephone ‘captures most cleanly the magnification of social contact’.23 However, as with other examples of modern technology, there is a danger of falling into technological determinism, particular in a context of advertising and media hype.

Great American Railroad Journeys

by

Michael Portillo

Published 26 Jan 2017

The task was completed the following year. By 1866, a telegraph line had been laid across the Atlantic Ocean, linking the US and Europe. At the time, Western Union sent 5.8 million messages a year. By the turn of the century the annual figure had risen to 63.2 million. Technology did not stand still, however, and soon the inventions of the telephone and radio with wireless telegraphy were threatening the primacy of the telegraph. TELEGRAPHS, TRAINS & TIMETABLES From 1851, the telegraph was used for routing trains, a valuable safety measure on the railroad system. So far, mostly single tracks had been laid, leaving trains at risk of head-on crashes or same-direction shunts.

The Great Reset: How the Post-Crash Economy Will Change the Way We Live and Work

by

Richard Florida

Published 22 Apr 2010

“It created a chemical industry with no chemistry, an iron industry without metallurgy, power machinery without thermodynamics.”11 By applying science to invention directly and systematically to industry, inventions were generated that vastly increased productivity and brought all this technological innovation into the daily lives of the middle class and the working class. George Westinghouse was another great systems-builder. Inspired by Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone and recognizing the inefficiencies inherent in Edison’s use of direct current, Westinghouse assembled teams of experts, including the great Serbian engineer Nikola Tesla, who developed signaling and switching systems and transformers, all of which allowed for faster and more widespread distribution of electricity.

Billions & Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium

by

Carl Sagan

Published 11 May 1998

The real binding up and deprovincial-ization of the planet requires a technology that communicates much faster than horse or sailing ship, that conveys information all over the world, and that is cheap enough to be available, at least occasionally, to the average person. Such a technology began with the invention of the telegraph and the laying of submarine cables; was greatly expanded by the invention of the telephone, using the same cables; and then enormously proliferated with the invention of radio, television, and satellite communications technology. Today we communicate—routinely, casually, with hardly ever a second thought—at the speed of light. From the speed of horse or sailing ship to the speed of light is an improvement by a factor of almost a hundred million.

The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism

by

Calum Chace

Published 17 Jul 2016

Tipping points and exponentials New technologies sometimes lurk for years or even decades before they are widely adopted. 3D printing (also known as additive manufacturing[cxxxi]) has been around since the early 1980s but is only now coming to general attention. Fax machines, surprisingly, were first patented in 1843, some 33 years before the invention of the telephone.[cxxxii] Sometimes the delay happens because there is at first no obvious application for the inventions or discoveries. Sometimes it is because they are initially too expensive, and engineers have to work on reducing their cost before they can become popular. And sometimes it is because they are simply not good enough when they are first demonstrated by researchers.

Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money That We Understand to Money That Understands Us (Perspectives)

by

David Birch

Published 14 Jun 2017

The past is about money as atoms. The present: Money 2.0 The present era began in 1871, when Western Union started formal electronic funds transfer (EFT) by telegraph and thus helped us to distinguish properly between invention and innovation. At the time, Western Union’s management team turned down the invention of the telephone, rather famously commenting: The ‘telephone’ has too many short-comings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us. That’s management for you, you might say, but there was no more reason for a telegraph company to catch the telephone wave than there was for Microsoft to invent Google or, for that matter, for a bank to invent the successor to the payment card.

The Eureka Factor

by

John Kounios

Published 14 Apr 2015

While enjoying the natural beauty that surrounded him, he suddenly realized that sound waves could be transformed into flowing currents of electricity. Conducted along wires, these electrical currents could be converted back into sound waves at a distant location. This idea was the basis for his invention of the telephone. A common thread runs through the stories of Jerry Swartz, Alexander Graham Bell, and many other creative figures. Hermann von Helmholtz explained how a good mood and relaxing walks in the country stoked his creativity. Art Fry was happily singing in church, fumbling with bookmarks in his hymnal, when he suddenly thought of the perfect use for a weak adhesive recently developed at his company, 3M: Post-it Notes.

The Trouble With Billionaires

by

Linda McQuaig

Published 1 May 2013

More importantly, it turned out that the mechanism outlined by Bell in his original patent wouldn’t have actually worked – he had to file another patent soon afterward, correcting some of his design problems – while Gray’s original submission would have worked. After years of unsuccessful litigation by Gray, Bell’s claim now stands unchallenged in popular history.7 But clearly, Alexander Graham Bell was not indispensable to the invention of the telephone. There’s even evidence that half a decade before 1876, when Bell and Gray were virtually tied in the race to ‘invent’ the telephone, Antonio Meucci, an Italian stage technician, had quietly crossed the finish line. Meucci had already essentially developed a telephone, which he called the ‘teletrofono’.

Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms

by

David S. Evans

and

Richard Schmalensee

Published 23 May 2016

The early work by economists on network effects nevertheless laid the foundations for the later research on multisided platforms.3 So it is worth spending some time describing the older research before we explain what went wrong when people started applying a simple theory with just one kind of customer to a complex multisided world with several different kinds of customers. A pioneering paper by Jeffrey Rohlfs dealt with the early days of landline telephone service, which was introduced in the United States following the 1876 invention of the telephone.4 A telephone was useless if nobody else had one. Even Bell and Watson started with two. A telephone was more valuable if a user could reach more people. Economists call this phenomenon a direct network effect. The more people connected to a network, the more valuable that network is to each person who is part of it.

Lurking: How a Person Became a User

by

Joanne McNeil

Published 25 Feb 2020

Nowadays, if there is any unique content an ISP provides (say, the Comcast home page), a user probably bypasses it, without a second of delay, to connect to the rest of the internet. Advertising for these online services told a story with a common theme: that of psychic teleportation, the power to travel beyond the borders of the physical world. The invention of the telephone celebrated sound over distance (the magic was the distance, two people connected through wires). But online services, early on, conceived of their products as more than objects or communication tools. The language used in these ads seemed to borrow from Emily Dickinson’s lyricism about books (a “Frigate … To take us Lands away”).

The Rise of the Network Society

by

Manuel Castells

Published 31 Aug 1996

Lessons from the Industrial Revolution Historians have shown that there were at least two industrial revolutions: the first started in the last third of the eighteenth century, characterized by new technologies such as the steam engine, the spinning jenny, the Cort’s process in metallurgy, and, more broadly, by the replacement of hand-tools by machines; the second one, about 100 years later, featured the development of electricity, the internal combustion engine, science-based chemicals, efficient steel casting, and the beginning of communication technologies, with the diffusion of the telegraph and the invention of the telephone. Between the two there are fundamental continuities, as well as some critical differences, the main one being the decisive importance of scientific knowledge in sustaining and guiding technological development after 1850.22 It is precisely because of their differences that features common to both may offer precious insights in understanding the logic of technological revolutions.

…

The Historical Sequence of the Information Technology Revolution The brief, yet intense history of the information technology revolution has been told so many times in recent years as to render it unnecessary to provide the reader with another full account.39 Besides, given the acceleration of its pace, any such account would be instantly obsolete, so that between my writing this and your reading it (let’s say 18 months), microchips will have doubled in performance at a given price, according to the generally acknowledged “Moore’s law.”40 Nevertheless, I find it analytically useful to recall the main axes of technological transformation in information generation/processing/transmission, and to place them in the sequence that drifted toward the formation of a new socio-technical paradigm.41 This brief summary will allow me, later on, to skip references to technological features when discussing their specific interaction with economy, culture, and society throughout the intellectual itinerary of this book, except when new elements of information are required. Micro-engineering macro-changes: electronics and information Although the scientific and industrial predecessors of electronics-based information technologies can be found decades before the 1940s42 (not the least being the invention of the telephone by Bell in 1876, of the radio by Marconi in 1898, and of the vacuum tube by De Forest in 1906), it was during the Second World War, and in its aftermath, that major technological breakthroughs in electronics took place: the first programmable computer, and the transistor, source of microelectronics, the true core of the information technology revolution in the twentieth century.43 Yet I contend that only in the 1970s did new information technologies diffuse widely, accelerating their synergistic development and converging into a new paradigm.

From Gutenberg to Google: electronic representations of literary texts

by

Peter L. Shillingsburg

Published 15 Jan 2006

Time and place of script generation cease to be the demarcating boundaries they are to speech generation – though they remain a palpable element of every script reception, as they are to listening. The advent of radio and television and of voice recordings which make possible the one-way extension of oral speech across distance and time has, of course, parallels to the conventions of writing and printing, as does the invention of the telephone and teleconference communication that allow ‘‘real time’’ two-way communication between individuals and small groups in separate locations. These similarities are important, particularly in any exploration of how communication fails. My subject is primarily writing and printing, and I draw on oral forms only for analogies and contrasts.

Oil Panic and the Global Crisis: Predictions and Myths

by

Steven M. Gorelick

Published 9 Dec 2009

The point is that increasing demand for a finite resource, as reflected by increasing production, does not necessarily create either economic scarcity or price increases. Copper, the first metal to come into widespread use on a large scale, is a good example of a commodity whose scarcity has been improperly projected. After the invention of the telephone in 1887, copper became an essential commodity in the industrialized world. Demand grew by almost 6 percent a year through the mid-1900s, reflecting copper ’s widespread use in construction and industry. In 1950, the US Geological Survey estimated worldwide reserves at 91 million metric tons, an amount that only would have lasted for 38 years at the production rates of the day.

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by

Tim Harford

Published 1 Jan 2008

There is one simple explanation for this pattern: When people are in cities, they are getting smarter quickly because they are learning from one another. Lucas and Marshall were quite right: Learning really is invisibly hanging “in the air” in cities. And looking at how wages change allows you to see the invisible. But the world is changing. Marshall was writing less than a decade after the invention of the telephone; even Lucas was speaking several years before the development of the World Wide Web, and could scarcely have imagined Facebook or the BlackBerry. Are ubiquitous, cheap, and powerful new communications technologies eroding the special advantages of cities? And if so, will cities continue to be centers of learning in the future as they have been in the past?

The Upside of Inequality

by

Edward Conard

Published 1 Sep 2016

No one would take them seriously. Yet supposedly serious economists make exactly this argument all the time. Or they compare America today with the 1990s, when the Internet, e-mail, and cell phones were first commercialized.19 Those inventions had a substantial impact on boosting productivity akin to the invention of the telephone. The enormous payoff for deploying these technologies overwhelmed small changes in the tax rate. These economists also ignore the fact that growth pushed all government spending (i.e., federal, state, and local) to a low of 32 percent of GDP in the 1990s.20 Similarly, they point to the success of innovation in California despite the difference of a couple of points in the state tax rate, which is small compared with the enormous benefit of working alongside the experts in Silicon Valley.21 When making comparisons to contemporary Europe, advocates of income redistribution avoid comparisons to Southern Europe and focus exclusively on Scandinavia, where academic test scores are higher than those in America.22 In knowledge-based economies, academic capabilities accelerate growth.

The Digital Divide: Arguments for and Against Facebook, Google, Texting, and the Age of Social Netwo Rking

by

Mark Bauerlein

Published 7 Sep 2011

One or another of them may mark a fabulous breakthrough, but they don’t stand out for long as striking advances in the march of technology. Soon enough they settle into one more utility, one more tool or practice in the mundane course of job and leisure. How many decades passed between the invention of the telephone and its daily use by 90 percent of the population? Today, the path from private creation to pandemic consumption is measured in months. Consider the Facebook phenomenon. The network dates back to 2004, but seems to have been around forever. In six years it has ballooned from a clubby undergraduate service at Harvard into a worldwide enterprise with more than 500 million users.

Augmented: Life in the Smart Lane

by

Brett King

Published 5 May 2016

One of my favourite disruption stories is that of the Pony Express in the days of the so-called “Wild West”. The Pony Express closed on 26th October 1861, just two days after the first transcontinental telegraph line connecting the eastern and western parts of the United States went into operation—now that wasn’t a coincidence. The telegraph was, in turn, rapidly disrupted by the invention of the telephone. Today, we know Western Union as a money transmitter but, back in 1856, Western Union was the largest provider of telegraph services across the United States, and by 1890 its reach extended even across the Atlantic. Inflation adjusted, Western Union was capitalised at around US$850 million dollars (US$41 million actual) in 1876.

Is That a Fish in Your Ear?: Translation and the Meaning of Everything

by

David Bellos

Published 10 Oct 2011

TWENTY-FOUR A Fish in Your Ear: The Short History of Simultaneous Interpreting Speech predates writing by eons, and oral translation is far, far older than the written kind. Because speech is such an ephemeral thing—it’s gone in a puff of warm air, which is all it is in the material sense—nothing can be known directly about speech translation for almost the entire duration of its history. Two things caused a huge change in the twentieth century: the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, and a political need of the most pressing kind. The Nuremberg Trials of Nazi war criminals in 1945 was one of the most important courts of law in modern history and also an unprecedented event in the history of translation. The panel of judges and the prosecuting teams came from the four Allied powers—the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union—speaking three different languages, and the defendants spoke a fourth language, German.

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century

by

Steven Pinker

Published 1 Jan 2014

Writers can profit by reading more than one style guide, and much of Strunk and White (as it is commonly called) is as timeless as it is charming. But much of it is not. Strunk was born in 1869, and today’s writers cannot base their craft exclusively on the advice of a man who developed his sense of style before the invention of the telephone (let alone the Internet), before the advent of modern linguistics and cognitive science, before the wave of informalization that swept the world in the second half of the twentieth century. A manual for the new millennium cannot just perpetuate the diktats of earlier manuals. Today’s writers are infused by the spirit of scientific skepticism and the ethos of questioning authority.

Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language

by

Gretchen McCulloch

Published 22 Jul 2019

There’s not that much difference between a late-1990s teenager constantly sending mundane but vital updates via AOL Instant Messenger and creating social drama about who was in their top eight friends on MySpace and a mid-2010s teen who’s constantly sending mundane but vital updates via Snapchat and creating social drama about who liked whose selfie on Instagram. But we haven’t seen an older generation mass-adopt a large-scale communications technology in quite a while—perhaps not since the invention of the telephone. So far, we’re only getting the first glimmerings of what it’s like for a whole cohort of seniors to be longtime Internet People, but small-scale efforts to teach older folks how to use the internet do suggest it can lead them to feeling more socially connected. I’d love to see a proper corpus study comparing postcards and texts from younger and older people, to see what else we can learn by drawing together informal writing across different generations and mediums.

The Future of Money

by

Bernard Lietaer

Published 28 Apr 2013

We know that the technological changes that have the most radical revolutionary impact on societies are those that change the tools by which people relate to each other. Fundamental shifts in civilisation have been traced back to the invention of writing, the alphabet and to the printing press. The breathtaking social, political and economic implications of the invention of the telephone, car, and television are classic examples of such shifts that occurred during the 20th century. Changes in the nature of money will have at least as great an impact as any of the above examples. Money is our key tool for material exchanges with people beyond our immediate intimate circle.

QI: The Book of General Ignorance - The Noticeably Stouter Edition

by

Lloyd, John

and

Mitchinson, John

Published 7 Oct 2010

Meucci died in 1889, while his case against Bell was still under way. As a result, it was Bell, not Meucci who got the credit for the invention. In 2004, the balance was partly redressed by the US House of Representatives who passed a resolution that ‘the life and achievements of Antonio Meucci should be recognized, and his work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged.’ Not that Bell was a complete fraud. As a young man he did teach his dog to say ‘How are you, grandmamma?’ as a way of communicating with her when she was in a different room. And he made the telephone a practical tool. Like his friend Thomas Edison, Bell was relentless in his search for novelty.

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 24 Dec 2011

“Even before wireless access, we saw people leaving their cubicles to work on park benches with their laptops and cell phones,” said Anthony Townsend, the same research scientist at New York University’s Taub Urban Research Center and NYCWireless cofounder we met in Chapter 6.67 When I called Townsend to talk about community wireless networking, we also talked about the way changes in communication practices influence the way people use cities. I knew that he had written about the subject: “The modern city of office towers is as much an artifact of the invention of the telephone as the decentralization of manufacturing and residences to the suburbs.”68 Wireless Internet access points provided by NYCWireless in Washington Square Park in 2001 and Bryant Square Park in 2002 are changing the way the people who work in those neighborhoods go about their business—in ways that Townsend believes can be more convivial than constant confinement in cubicles.

Empire of the Sum: The Rise and Reign of the Pocket Calculator

by

Keith Houston

Published 22 Aug 2023

Gibberd, “Davy, Edward (1806–1885),” Australian Dictionary of Biography (National Centre of Biography, Australian National University), accessed June 11, 2021, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/davy-edward-1966. 23 Lewis Coe, The Telegraph: A History of Morse’s Invention and Its Predecessors in the United States (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1993), 30–31. 24 R. W. Burns, “Bell, Alexander Graham (1847–1922), Teacher of Deaf People and Inventor of the Telephone,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/30680. 25 G.W.O. Howe, “Alexander Graham Bell and the Invention of the Telephone,” Nature 159, no. 4040 (1947): 455–457, https://doi.org/10.1038/159455a0. 26 Paul E. Ceruzzi, Reckoners: The Prehistory of the Digital Computer, from Relays to the Stored Program Concept, 1935–1945 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983), 74. 27 Burns, “Bell, Alexander Graham”; Howe, “Alexander Graham Bell”; Benjamin Lathrop Brown, “The Bell Versus Gray Telephone Dispute: Resolving a 144-Year-Old Controversy,” Proceedings of the IEEE 108, no. 11 (November 1, 2020): 2083–2096, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2020.3017876. 28 “Bell Telephone Laboratories,” Physics History Network (American Institute of Physics), accessed June 14, 2021, https://history.aip.org/phn/21506003.html. 29 J.A.N.

Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America Into the Space Age

by

Robert Stone

and

Alan Andres

Published 3 Jun 2019

Clarke confided to Bernstein Jeremy Bernstein, “The Grasshopper and His Space Odyssey: A Scientist Remembers the Celebrated Science Fiction Writer Arthur C. Clarke,” American Scholar (Summer 2008). Semaphore and smoke-signal era ACC, interview filmed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Conference on the Centennial of the Invention of the Telephone (March 9, 1976), ATT 16mm film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1vQ_cB0f4w. Cranks were littering ACC, interview with Malcolm Kirk, Omni (March 1979). Motivated by anger Bill Kaysing, interview with Nardwuar, aka John Ruskin (February 16, 1996), https://nardwuar.com/vs/bill_kaysing/.

Binge Times: Inside Hollywood's Furious Billion-Dollar Battle to Take Down Netflix

by

Dade Hayes

and

Dawn Chmielewski

Published 18 Apr 2022

“These early marvels had equally marvelous names,” he writes, like the fantascope, the phenakistoscope, and the zoetrope. “They were made by imprinting drawings around the edges of a disc. When the disc spun and was seen through a viewer, the pictures appeared to be in continuous motion.” After the astonishing invention of the telephone after the Civil War, a feat credited to AT&T cofounder Alexander Graham Bell, spellbound Americans started to anticipate that images would one day mingle with voices. An 1879 spread in Punch magazine showed a fanciful rendering by George du Maurier of a fictional but entirely plausible device beaming moving pictures onto a living room wall.

Hacking Capitalism

by

Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

The boys played pranks while connecting customers and they were soon replaced with more reliable, female personnel.1 This historical anecdote is in accordance with the portrayal of hacking as it comes across in mainstream media. Hacking is regularly reduced to an apolitical stunt of male, juvenile mischievousness, and, ultimately, it is framed as a control issue. In order to emphasise the political dimension of hacking, it is apt to outline a different ‘mythical past’ of hackers. This story too begins with the invention of the telephone. Graham Bell was not only a prominent inventor but also a forerunner in exercising his patent rights. The business model which his family built up around the patent was no less prophetic. Telephones were leased rather than sold to customers and the monopoly service was provided through a network of franchised subsidiaries.

Paper: A World History

by

Mark Kurlansky

Published 3 Apr 2016

There is also a popular belief that now the world is changing more dramatically or more swiftly than it ever has before. That too is probably not true. During the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, scarcely a year passed without at least one life-changing new invention. The invention of the cell phone has changed our lives, but has it had as great an influence as did the invention of the telephone? Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone in 1876, the same year that Nikolaus August Otto developed the first usable internal-combustion engine, which led the way to automobiles. The following year, Edison invented the phonograph, and Eadweard Muybridge the moving picture. The year after that, Joseph Wilson Swan built the incandescent lightbulb, the first bulb that would burn long enough for practical applications, and transparent film was invented.

Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity

by

Edward Tenner

Published 8 Jun 2004

Succeeding decades saw the prime of artistic iconoclasm, the ferment of movements from futurism to surrealism. Yet none of these changes seriously challenged the familiar arrangement of keys. The piano keyboard dominated the first years of electronic music. When the American inventor Elisha Gray, Alexander Graham Bell’s unsuccessful rival for priority in the invention of the telephone, introduced a “musical telegraph” in 1876, he activated his row of oscillators (really buzzers) with piano-style controls. The English physicist William Du Bois Duddell discovered how to make the carbon-arc lamps of the day produce tones—controlled by the familiar device. The most majestic electronic instrument ever, Thomas Cahill’s Telharmonium, had 145 customized dynamos generating currents of different audio frequencies that were picked up by acoustic horns attached to telephone receivers.

The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 30 Sep 2009

The Underground system was not only used by vast numbers of commuters, both directly and connecting in from the main line railway, but also attracted other sections of the population who travelled on it for business or leisure purposes. For example, there were the innumerable messengers who, before the invention of the telephone, were the principal way of conveying information quickly between offices. Even more important were the various groups of leisure travellers. The most significant in terms of numbers were the shoppers visiting the large department stores which had begun to spring up following the opening of the Army and Navy store in 1872.

Tools and Weapons: The Promise and the Peril of the Digital Age

by

Brad Smith

and

Carol Ann Browne

Published 9 Sep 2019

We chose the Willard hotel for a reason—not only to attract the attention of federal lawmakers, but as a nod to a special occasion that took place at that same spot on March 7, 1916. Alexander Graham Bell, the leaders of American Telephone &Telegraph, and luminaries from across the nation had gathered at the grand hotel for a lavish banquet hosted by the National Geographic Society to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Bell’s invention of the telephone. AT&T’s leaders, however, wanted to do more than celebrate the past. They had developed a plan to use the evening to sketch a bold vision for the future.20 Theodore Vail, AT&T’s president, wanted to inspire the nation with a vision of bringing long-distance telephones to every corner of the country, no matter how remote.

Googled: The End of the World as We Know It

by

Ken Auletta

Published 1 Jan 2009

When Google Earth started displaying paintings from the Prado in Madrid, allowing users to zoom in and see the art as an up-close digital photo, it was giving many people access to art they would never see, granting them the time to study paintings that security guards in the bustling museum would never allow them. This was a wonderful opportunity to extend the public’s appreciation of great art. But perhaps we’ll learn that it wasn’t so wonderful for the museum’s box office. Just as the invention of the telephone crushed the telegraph, so motion pictures crippled vaudeville, television eclipsed radio, cable weakened broadcasting, and iTunes shattered CD music album sales. In some cases, new technologies brought new opportunities. The movie studios, after huffing about television, belatedly discovered a lucrative new platform to sell their movies.

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by

Tim Wu

Published 2 Nov 2010

Danielian, AT&T: The Story of Industrial Conquest (New York: Vanguard, 1939); Arthur Page, The Bell Telephone System (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941); Horace Coon, American Tel & Tel: The Story of a Great Monopoly (New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1939); Sonny Kleinfeld, The Biggest Company on Earth: A Profile of AT&T (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1981); John Brooks, Telephone: The First One Hundred Years (New York: Harper & Row, 1976). 2. William W. Fisher III, “The Growth of Intellectual Property: A History of the Ownership of Ideas in the United States,” in Intellectual Property Rights: Critical Concepts in Law, vol. I, 83, David Vaver ed., (New York: Routledge, 2006). 3. The controversy over the invention of the telephone has engendered a small industry, including four volumes written in the twenty-first century. It begins with “How Gray Was Cheated,” New York Times, May 22, 1886; see also A. Edward Evenson, The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876: The Elisha Gray–Alexander Bell Controversy (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000); Burton H.

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by

John Kay

Published 24 May 2004

The market for pigs became a market for pork bellies, and you would not be welcomed to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange if you brought along the commodities you proposed to sell. But there was still a place where buyers and sellers met. The assumption that markets would have a physical location Culture and Prosperity { 149} changed with the invention of the telephone, which made it easy for people who were not in the same place to negotiate deals. But communication by telephone was one to one. Only with the development of modern electronic systems was it possible to secure access to information about other trades and other traders-the access that San Remo traders enjoy by watching each other-without an actual physical meeting place.

Capitalism in America: A History

by

Adrian Wooldridge

and

Alan Greenspan

Published 15 Oct 2018

Telegraph lines were much cheaper to construct than railway lines: by 1852, America had twenty-two thousand miles of telegraph lines compared with eleven thousand miles of tracks. They also had a more dramatic effect: information that once took weeks to travel from place A to place B now took seconds. The invention of the telegraph was a much more revolutionary change than the invention of the telephone a few decades later. The telephone (rather like Facebook today) merely improved the quality of social life by making it easier for people to chat with each other. The telegraph changed the parameters of economic life—it broke the link between sending complicated messages and sending physical objects and radically reduced the time it took to send information.

The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

by

Jon Gertner

Published 15 Mar 2012

Working in an environment of applied science, as one Bell Labs researcher noted years later, “doesn’t destroy a kernel of genius—it focuses the mind.”9 Finally, something else seemed important. “A new device or a new invention,” Kelly once remarked, “stimulates and frequently demands other new devices and inventions for its proper use.”10 Just as the invention of the telephone had led to countless developments in switching and transmission, an invention like the transistor seemed to point to even more developments in switching, transmission, and computer systems. Or to put it another way, the solution to a technological problem invariably created other problems that needed solutions.

Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don't Have To

by

David A. Sinclair

and

Matthew D. Laplante

Published 9 Sep 2019

And if you are a politician wondering how it will be possible to provide meaningful, productive work to all the people, consider the city of Boston, where I live. Since it opened the first American university in 1724 and the first American patent office in 1790, the city has been home to the invention of the telephone, razor, radar, microwave oven, the internet, Facebook, DNA sequencing, and genome editing. In 2016 alone, Boston produced 1,869 start-ups and the state of Massachusetts registered more than 7,000 patents, about twice as many per capita as California.69 It is impossible to know how much wealth and how many jobs Boston has generated for the United States and globally, but in 2016 the robotics industry alone employed more than 4,700 people in 122 start-ups and generated more than $1.6 billion in revenue for the state.70 The best way to create jobs for productive people of any age, even less skilled workers, is to build and attract companies that hire highly skilled ones.

Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies

by

Geoffrey West

Published 15 May 2017

Before the coming of the railway most people didn’t travel more than twenty miles from their home during their entire lifetime: suddenly Brighton was in relatively easy reach of London, and Chicago in reach of New York. Messages that took days, weeks, or even months to be communicated before the invention of the telephone could now be communicated instantaneously. The changes were fantastic. Relatively speaking, these had a greater impact on our lives and, in particular, in speeding up life and changing our visceral perception of space and time than our present IT revolution. But these didn’t result in a de-urbanizing phenomenon or a contraction of our cities.

Aerotropolis

by

John D. Kasarda

and

Greg Lindsay

Published 2 Jan 2009

So what if oil goes back above a hundred dollars a barrel? They’ll adapt, they’ll restruc-ture, some will fold. What does that mean for the aerotropolis? It means businesses are going to aggregate even more closely around the major hubs, because that’s where connectivity will be the most abundant. Tele-commuting won’t make a dent. From the invention of the telephone to Facebook, every advance in communication only increases our desire to travel. The trillions of connections occurring now will create a need for mobility that never previously existed. What would we turn to without planes? Trains? Cars? Think of the carbon that goes into paving a fifty-mile stretch of highway.

The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 14 Jul 2005

Early human civilizations with oral histories were able to preserve stories for hundreds of years. With the advent of written language the permanence extended to thousands of years. As one of many examples of the acceleration of the technology paradigm-shift rate, it took about a half century for the late-nineteenth-century invention of the telephone to reach significant levels of usage (see the figure below). 17 In comparison, the late-twentieth-century adoption of the cell phone took only a decade.18 Overall we see a smooth acceleration in the adoption rates of communication technologies over the past century.19 As discussed in the previous chapter, the overall rate of adopting new paradigms, which parallels the rate of technological progress, is currently doubling every decade.

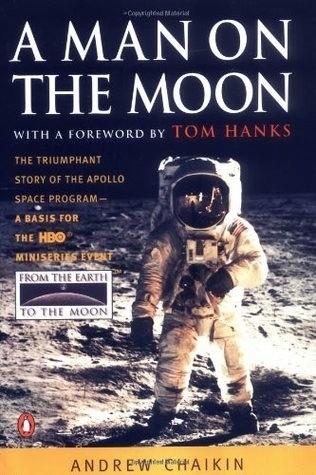

A Man on the Moon

by

Andrew Chaikin

Published 1 Jan 1994

Born in Liberia, he'd been taken aboard a slave ship at the age of twelve and brought to Galveston, Texas, where he grew up on a white man's ranch. He'd toted a .45 since he was thirteen, and could tell tales of riding with Jesse James and Billy the Kid. In his adult life he had witnessed the invention of the telephone, the automobile, the airplane, television, the atomic bomb, and the microchip. In December 1972, Charlie Smith's age was given at one hundred and thirty years. As the oldest living American he was invited to the launch of Apollo 17, and so he and his seventy-year-old son Chester traveled from a central-Florida town called Bartow to the Kennedy Space Center.