invisible hand

description: economic concept popularized by Adam Smith

733 results

The Invisible Hands: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Bubbles, Crashes, and Real Money

by Steven Drobny · 18 Mar 2010 · 537pp · 144,318 words

? II. The Evolution of Real Money III. RETHINKING REAL MONEY—MACRO PRINCIPLES Chapter 2 - The Researcher Chapter 3 - The Family Office Manager Part Two - The Invisible Hands Chapter 4 - The House Chapter 5 - The Philosopher Chapter 6 - The Bond Trader Chapter 7 - The Professor Chapter 8 - The Commodity Trader Chapter 9 - The

…

books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our Web site at www.wiley.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drobny, Steven. The invisible hands : hedge funds off the record-rethinking real money / Steven Drobny; foreword by Jared Diamond. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN : 978-0-470

…

and into 2009, the book highlights certain valuable elements of the global macro approach that could be applied to other mandates within money management. The Invisible Hands begins by defining and discussing the importance of real money management. It then discusses the evolution of real money management and raises some important questions

…

. Then, “The Family Office Manager,” Jim Leitner, addresses the lessons he learned in 2008 and offers his own thoughts on rethinking real money. Next, the “Invisible Hands”—10 anonymous global macro hedge fund managers, the Philosopher, the House, the Professor, et al—discuss how they approach money management, how they managed to

…

focus the possibility of buying cheap insurance when the market is willing to sell it, before the horse has left the barn. Part Two The Invisible Hands [E]every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote

…

may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part

…

of my partner in crime, wordsmith extraordinaire, editorial genius, and cocreator, John Bonaccolta. John was instrumental in both Inside the House of Money and The Invisible Hands, and for that I am forever indebted. Working together dulled the pain of writing by not only having someone to collaborate with on words, but

…

follow-up. Their intellectual curiosity and boundless energy in dissecting world markets at our conferences is a constant source of motivation. Despite their anonymity, the “Invisible Hands” featured in this book took a bold step to reveal details of their work and broader thoughts for how to reshape the real money world

Globalists

by Quinn Slobodian · 16 Mar 2018 · 451pp · 142,662 words

lawyer Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann, wrote, “The common starting point of the neoliberal economic theory is the insight that in any well-functioning market economy the ‘invisible hand’ of market competition must by necessity be complemented by the ‘visible hand’ of the law.” He listed the well-known neoliberal schools of thought: the

…

implied that the economy was like the weather, a sphere outside of direct human control. One could adapt Adam Smith’s famous metaphor of the invisible hand to speak of the invisible wind of the market, captured in charts and graphs. The economic conditions portrayed in three lines were experienced as a

…

used to make debtors pay.”95 For Mises, a good version of the League had the capacity to act as an iron glove for the invisible hand of the market. Mises’s EDU proposal sought to realize a strong version of the League dream for the eastern half of Europe by radically

…

Society (New York: Verso, 2014); William Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition (Los Angeles: Sage, 2014); Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009); Ralf Ptak, Vom Ordoliberalismus zur sozialen Marktwirtschaft

…

. 4 (1981): 142. 13. Jörg Guido Hülsmann, Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007), 822–824; Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 43, 55. Mises served on the Economics

…

York Times, June 16, 1971; “Cortney, Philip,” in Current Biography (New York: H. W. Wilson, 1958), 4. 67. On the NAM, see Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009). 68. Hülsmann, Mises, 822–825, 829. 69

…

Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 55. 91. Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 56–58. 92. Rick Perlstein, Before the

…

Consensus (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 33. 93. Röpke to Paul Wilhelm Wenger, August 5, 1964, RA, file 89, p. 568. 94. Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands, 57, 59. Kim Phillips-Fein, “Business Conservatives and the Mont Pèlerin Society,” in Mirowski and Plehwe, The Road from Mont Pèlerin, 292. 95. See George

…

, p. 148. 131. Hunold to Röpke, March 20, 1964, RA, file 22, p. 298. On Goodrich’s role in financing MPS meetings, see Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands, 48–51. 132. Hennecke, Wilhelm Röpke, 224. 133. Kirk to Röpke, March 19, 1963, RA, file 21, p. 649. 134. For his resignation letter, see

…

des Neoliberalismus: Eine Studie zu Entwicklung und Ausstrahlung der “Mont Pelerin Society” (Stuttgart: Lucius und Lucius, 2008), 189. 141. On Spiritual Mobilization, see Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands, 71–74. 142. Hunold to Röpke, March 20, 1964, RA, file 22, p. 298. 143. Wilhelm Röpke, Against the Tide (Chicago: H. Regnery Co., 1969

Life After Cars: Freeing Ourselves From the Tyranny of the Automobile

by Sarah Goodyear, Doug Gordon and Aaron Naparstek · 21 Oct 2025 · 330pp · 85,349 words

.” That answer doesn’t satisfy the menacing, all-seeing vehicle. The voice commands him to get in the back seat. And then, controlled by some invisible hand, the car rolls off, taking Mead to the Psychiatric Center for Research on Regressive Tendencies. Walking? Just walking? In the year 2053? That’s insane

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

have felt like a Wild West, but it appeared to net out as a positive force. Backed by the power of crowds, the internet’s invisible hand could seemingly channel even the most destructive energies toward meaningful collective action. * * * The rumors about The Social Network sounded ludicrous: David Fincher, the director of

The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America

by John Fabian Witt · 14 Oct 2025 · 735pp · 279,360 words

of six novels on the problem in what he called his “Dead Hand” series. The name was in part a play on Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of capitalism. Sinclair, who was a sometime member of the Socialist Party, thought capitalism’s influence far more destructive than Smith’s

…

invisible hand metaphor had famously suggested. But the name of Sinclair’s series had a more specific meaning, too. The dead hand was the influence of the

…

Court, and the Battle for Racial Justice in the North (FSG, 2025). enervating effects: Stone, “The Post-War Paradigm.” anti-union campaigns: Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (W. W. Norton, 2009), 87–114. obsolete: Reuel Schiller, Forging Rivals: Race, Class

…

, 194 capitalism, 4–6, 9, 14, 91, 161, 200, 241, 257–60, 281, 305, 334, 358, 376, 412, 468, 497, 506, 537 culture and, 226 invisible hand of, 105 and nationalization of industry, 307, 309 Capper, Arthur, 431 Carnegie, Andrew, 3, 89, 96 Carnegie organizations, 89, 96, 174, 175, 178, 540 Caron

Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy

by Quinn Slobodian · 4 Apr 2023 · 360pp · 107,124 words

extensive interventions of government.”6 This got it backward. As one economist put it, it was the “long arm of state intervention” more than the “invisible hand of the free market” that explained Singapore’s success.7 While private interests shaped Hong Kong with the government in a supporting role, in Singapore

…

236 (2018): 968. 5. Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 327. 6. Milton Friedman, “The Invisible Hand in Economics and Politics,” Inaugural Singapore Lecture, Sponsored by the Monetary Authority of Singapore and Organized by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, October 14

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by Jackson Lears

may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part

…

the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. By the time Smith published these words in 1776, the invocation of an invisible hand or its equivalent was a familiar rhetorical move in natural history as well as social, economic, and political thought. Enlightenment thinkers were keenly aware of

…

Sentiments, which revealed a kind of invincible innocence: The rich … divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessities of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among

…

thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interests of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species. While Smith’s invisible hand was one of many instruments of self-organization imagined by eighteenth-century thinkers, his particular version of the trope met a peculiarly urgent ideological need

…

in John Sutton, Philosophy and Memory Traces: Descartes to Connectionism (1998), 103. “always include a force”: Pierre Gassendi, cited in Jonathan Sheehan and Dror Wahrman, Invisible Hands: Self-Organization and the Eighteenth Century (2015), 28. “moving animal spirits”: Thomas Willis, The Practice of Physick (1684), 36. “Magically and Sympathetically”: Ralph Cudworth, The

…

True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678), 162. “there must be something more”: Sheehan and Wahrman, Invisible Hands, 168. declared the only legitimate prayer to be spontaneous: Lori Branch, Rituals of Spontaneity: Sentiment and Secularism from Free Prayer to Wordsworth (2006), chap. 1

…

[er] is impressive”: Fortia de Piles, cited in Buchan, Law, 221. “The madness of stock-jobbing”: Robert Harley’s son, cited in Sheehan and Wahrman, Invisible Hands, 102. “City gamblers”: Defoe, cited in Backscheider, Defoe, 452. “Extravagant gamesters”: Defoe, cited in ibid., 454. “What makes a homely woman fair?”: Defoe, cited in

…

and; character and; corporate; corruption in; Defoe on; deregulation of; Dutch innovation in; evangelical rationality and; industrial; inequality under, see also labor; inflation in; international; invisible hand in; “lifestyles” created by; as market society; masculinity and; mental health under; metaphors of; money as life-force of; nature under; pleasure of; positive thinking

Impact: Reshaping Capitalism to Drive Real Change

by Ronald Cohen · 1 Jul 2020 · 276pp · 59,165 words

make a transformative difference, and each of us has a significant role to play in making it happen. The economist Adam Smith famously introduced the ‘invisible hand of markets’ in The Wealth of Nations at the end of the eighteenth century, to describe how everyone’s striving for profit results in everyone

…

-first century, he might well have combined his two books into one, and written about impact as the invisible heart of markets that guides their invisible hand. Chapter 1 THE IMPACT REVOLUTION: RISK–RETURN–IMPACT We must shift impact to the center of our consciousness We cannot change the world by throwing

…

it in his speech at the Consumer Goods Forum in Berlin, ‘Unlike what Wall Street is trying to tell us, there is no invisible hand. In particular, there is no invisible hand when it comes to [doing] the right or the wrong thing.’64 A much younger American yoghurt company, Chobani, is approaching the

…

and economic realm. As Rousseau was launching his political ideas on the world, Adam Smith introduced the theory of the ‘invisible hand of markets’ in The Wealth of Nations. In his view, ‘the invisible hand’– a metaphor for individuals acting in their own self-interest within a free market economy – created an equilibrium between

…

now call impact, he might have merged the two works and described a single economic system, in which the invisible heart of markets guides their invisible hand. The new ideas brought by The Wealth of Nations helped shift our economic system from mercantilism (which held that countries should use trade and the

…

) 64, 68–9 ‘Operating Principles for Impact Management’ 68–9 ‘The Promise of Impact’ report 69 Investing with Impact Platform 81–2 Invest Palestine 163 ‘invisible hand’ of markets 10, 97, 184, 185 invisible heart of markets 6, 10, 185 iPhone 77 Ireland 171 Israel 7, 39, 40, 50, 52, 53, 83

Ten Billion Tomorrows: How Science Fiction Technology Became Reality and Shapes the Future

by Brian Clegg · 8 Dec 2015 · 315pp · 92,151 words

were available to a human brain. The significance of this development is that where someone using the BrainGate approach would have to consciously control an invisible hand—fine to move a cursor, but very slow for an action like typing—this approach would make it possible to think about typing and to

…

inclined to perform acts of kindness and valor, or even to hide from enemies. Time after time, he or she will peek and pry where invisible hands should not reach, will steal or abuse others in misdemeanors from petty pinching, eventually pushing to sexual transgressions and murder. In early stories, the ability

Why Government Is the Problem

by Milton Friedman · 1 Feb 1993 · 25pp · 7,179 words

is against the self-interest of the rest of us. You remember Adam Smith's famous law of the invisible hand: People who intend only to seek their own benefit are "led by an invisible hand to serve a public interest which was no part of" their intention. I say that there is a

…

reverse invisible hand: People who intend to serve only the public interest are led by an invisible hand to serve private interests which was no part of their intention. I believe our present predicament exists because we

The Vanishing Middle Class: Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy

by Peter Temin · 17 Mar 2017 · 273pp · 87,159 words

The Growth Delusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-Being of Nations

by David Pilling · 30 Jan 2018 · 264pp · 76,643 words

Exploring Everyday Things with R and Ruby

by Sau Sheong Chang · 27 Jun 2012

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by Ed Finn · 10 Mar 2017 · 285pp · 86,853 words

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by William Easterly · 4 Mar 2014 · 483pp · 134,377 words

Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle

by Silvia Federici · 4 Oct 2012 · 277pp · 80,703 words

From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

by Fred Turner · 31 Aug 2006 · 339pp · 57,031 words

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race

by Nicole Perlroth · 9 Feb 2021 · 651pp · 186,130 words

Anarchy State and Utopia

by Robert Nozick · 15 Mar 1974 · 524pp · 146,798 words

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

by Benjamin H. Bratton · 19 Feb 2016 · 903pp · 235,753 words

The Origins of the Urban Crisis

by Sugrue, Thomas J.

Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century

by Mark Leonard · 4 Sep 2000 · 131pp · 41,052 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny

by Robert Wright · 28 Dec 2010

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

Emotional Labor: The Invisible Work Shaping Our Lives and How to Claim Our Power

by Rose Hackman · 27 Mar 2023

Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters

by Brian Klaas · 23 Jan 2024 · 250pp · 96,870 words

Sleeping Giant: How the New Working Class Will Transform America

by Tamara Draut · 4 Apr 2016 · 255pp · 75,172 words

Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess

by Robert H. Frank · 15 Jan 1999 · 416pp · 112,159 words

In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? The History and Future of Artificial Intelligence

by George Zarkadakis · 7 Mar 2016 · 405pp · 117,219 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

Bleeding Edge: A Novel

by Thomas Pynchon · 16 Sep 2013 · 532pp · 141,574 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life

by Robert Wright · 1 Jan 1994 · 604pp · 161,455 words

The Penguin and the Leviathan: How Cooperation Triumphs Over Self-Interest

by Yochai Benkler · 8 Aug 2011 · 187pp · 62,861 words

Mindwise: Why We Misunderstand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want

by Nicholas Epley · 11 Feb 2014 · 369pp · 90,630 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by Benjamin R. Barber · 1 Jan 2007 · 498pp · 145,708 words

Jihad vs. McWorld: Terrorism's Challenge to Democracy

by Benjamin Barber · 20 Apr 2010 · 454pp · 139,350 words

Class Acts: Service and Inequality in Luxury Hotels

by Rachel Sherman · 18 Dec 2006 · 380pp · 153,701 words

Social Life of Information

by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid · 2 Feb 2000 · 791pp · 85,159 words

Economic Dignity

by Gene Sperling · 14 Sep 2020 · 667pp · 149,811 words

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero

by Tyler Cowen · 8 Apr 2019 · 297pp · 84,009 words

A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market

by John Allen Paulos · 1 Jan 2003 · 295pp · 66,824 words

Virtual Competition

by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke · 30 Nov 2016

The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good

by William Easterly · 1 Mar 2006

Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976-1980

by Rick Perlstein · 17 Aug 2020

Emergence

by Steven Johnson · 329pp · 88,954 words

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by Ann Pettifor · 27 Mar 2017 · 182pp · 53,802 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

by Tim Sullivan · 6 Jun 2016 · 252pp · 73,131 words

The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

by Kevin Kelly · 6 Jun 2016 · 371pp · 108,317 words

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Apr 2008 · 304pp · 22,886 words

The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good

by Robert H. Frank · 3 Sep 2011

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by John Kay · 24 May 2004 · 436pp · 76 words

Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet

by Andrew Blum · 28 May 2012 · 314pp · 83,631 words

The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information

by Frank Pasquale · 17 Nov 2014 · 320pp · 87,853 words

The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet

by Jeff Goodell · 10 Jul 2023 · 347pp · 108,323 words

Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings

by Jay Barbree, Howard Benedict, Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton and Neil Armstrong · 1 Jan 1994 · 469pp · 124,784 words

For Profit: A History of Corporations

by William Magnuson · 8 Nov 2022 · 356pp · 116,083 words

Humankind: Solidarity With Non-Human People

by Timothy Morton · 14 Oct 2017 · 225pp · 70,180 words

The Fabric of the Cosmos

by Brian Greene · 1 Jan 2003 · 695pp · 219,110 words

The Controlled Demolition of the American Empire

by Jeff Berwick and Charlie Robinson · 14 Apr 2020 · 491pp · 141,690 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

Gravity's Rainbow

by Thomas Pynchon · 15 Jan 2000 · 1,051pp · 334,334 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (And How to Take Advantage of It)

by William Poundstone · 1 Jan 2010 · 519pp · 104,396 words

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by Vito Tanzi · 28 Dec 2017

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

Respectable: The Experience of Class

by Lynsey Hanley · 20 Apr 2016 · 230pp · 79,229 words

Making Globalization Work

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 16 Sep 2006

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by Meghnad Desai · 15 Feb 2015 · 270pp · 73,485 words

The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism

by Arun Sundararajan · 12 May 2016 · 375pp · 88,306 words

Cities Are Good for You: The Genius of the Metropolis

by Leo Hollis · 31 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 118,314 words

Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality

by Richard G. Wilkinson · 19 Nov 1996 · 268pp · 89,761 words

"They Take Our Jobs!": And 20 Other Myths About Immigration

by Aviva Chomsky · 23 Apr 2018 · 219pp · 62,816 words

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

by James Clear · 15 Oct 2018 · 301pp · 78,638 words

Stacy Mitchell

by Big-Box Swindle The True Cost of Mega-Retailers and the Fight for America's Independent Businesses (2006)

Will Storr vs. The Supernatural: One Man's Search for the Truth About Ghosts

by Will Storr · 4 Sep 2006 · 341pp · 99,940 words

The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times

by Giovanni Arrighi · 15 Mar 2010 · 7,371pp · 186,208 words

10% Less Democracy: Why You Should Trust Elites a Little More and the Masses a Little Less

by Garett Jones · 4 Feb 2020 · 303pp · 75,192 words

Platform Scale: How an Emerging Business Model Helps Startups Build Large Empires With Minimum Investment

by Sangeet Paul Choudary · 14 Sep 2015 · 302pp · 73,581 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

I You We Them

by Dan Gretton

Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing

by Rachel Plotnick · 24 Sep 2018 · 359pp · 105,248 words

Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science

by Michael Nielsen · 2 Oct 2011 · 400pp · 94,847 words

User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design Are Changing the Way We Live, Work & Play

by Cliff Kuang and Robert Fabricant · 7 Nov 2019

Snow Crash

by Neal Stephenson · 15 Jul 2003 · 550pp · 160,356 words

The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions

by Greta Thunberg · 14 Feb 2023 · 651pp · 162,060 words

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 7 May 2024 · 470pp · 158,007 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community

by David C. Korten · 1 Jan 2001

Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 27 Nov 2012 · 651pp · 180,162 words

Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2009 · 471pp · 97,152 words

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by Roger Scruton · 16 Nov 2017 · 190pp · 56,531 words

Wealth and Poverty: A New Edition for the Twenty-First Century

by George Gilder · 30 Apr 1981 · 590pp · 153,208 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution

by Wendy Brown · 6 Feb 2015

Fuller Memorandum

by Stross, Charles · 14 Jan 2010 · 366pp · 107,145 words

The Village Effect: How Face-To-Face Contact Can Make Us Healthier, Happier, and Smarter

by Susan Pinker · 30 Sep 2013 · 404pp · 124,705 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall · 19 Mar 2019 · 393pp · 115,217 words

The Player of Games

by Iain M. Banks · 14 Jan 2011 · 216pp · 115,870 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

The New Rules of War: Victory in the Age of Durable Disorder

by Sean McFate · 22 Jan 2019 · 330pp · 83,319 words

Fool Me Twice: Fighting the Assault on Science in America

by Shawn Lawrence Otto · 10 Oct 2011 · 692pp · 127,032 words

The Ages of Globalization

by Jeffrey D. Sachs · 2 Jun 2020

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by Michael Shermer · 8 Apr 2020 · 677pp · 121,255 words

The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism

by Jeremy Rifkin · 31 Mar 2014 · 565pp · 151,129 words

Culture & Empire: Digital Revolution

by Pieter Hintjens · 11 Mar 2013 · 349pp · 114,038 words

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right

by Jane Mayer · 19 Jan 2016 · 558pp · 168,179 words

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by William Davidow and Michael Malone · 18 Feb 2020 · 304pp · 80,143 words

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by Phil Thornton · 7 May 2014

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber · 1 Jan 2010 · 725pp · 221,514 words

The Equality Machine: Harnessing Digital Technology for a Brighter, More Inclusive Future

by Orly Lobel · 17 Oct 2022 · 370pp · 112,809 words

Break Through: Why We Can't Leave Saving the Planet to Environmentalists

by Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus · 10 Mar 2009 · 454pp · 107,163 words

Energy: A Human History

by Richard Rhodes · 28 May 2018 · 653pp · 155,847 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds - the Original Classic Edition

by Charles MacKay · 14 Jun 2012 · 343pp · 41,228 words

Shampoo Planet

by Douglas Coupland · 28 Dec 2010

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

The Pirate's Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism

by Matt Mason

The Gene: An Intimate History

by Siddhartha Mukherjee · 16 May 2016 · 824pp · 218,333 words

Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree World

by Robert Lawson and Benjamin Powell · 29 Jul 2019 · 164pp · 44,947 words

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by Jaron Lanier · 21 Nov 2017 · 480pp · 123,979 words

Free to Choose: A Personal Statement

by Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman · 2 Jan 1980 · 376pp · 118,542 words

The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being

by William Davies · 11 May 2015 · 317pp · 87,566 words

Why Nudge?: The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism

by Cass R. Sunstein · 25 Mar 2014 · 168pp · 46,194 words

The Meritocracy Myth

by Stephen J. McNamee · 17 Jul 2013 · 440pp · 108,137 words

Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order

by Parag Khanna · 4 Mar 2008 · 537pp · 158,544 words

Zero History

by William Gibson · 6 Sep 2010 · 457pp · 112,439 words

The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View From the Future

by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway · 30 Jun 2014 · 105pp · 18,832 words

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

by Yuval Noah Harari · 1 Mar 2015 · 479pp · 144,453 words

The Trouble With Billionaires

by Linda McQuaig · 1 May 2013 · 261pp · 81,802 words

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

by Anand Giridharadas · 27 Aug 2018 · 296pp · 98,018 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

Talk on the Wild Side

by Lane Greene · 15 Dec 2018 · 284pp · 84,169 words

Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism

by Peter Marshall · 2 Jan 1992 · 1,327pp · 360,897 words

Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets

by John McMillan · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 103,988 words

Small Change: Why Business Won't Save the World

by Michael Edwards · 4 Jan 2010

Who Rules the World?

by Noam Chomsky

Nomad Citizenship: Free-Market Communism and the Slow-Motion General Strike

by Eugene W. Holland · 1 Jan 2009 · 265pp · 15,515 words

Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut

by Mike Mullane · 24 Jan 2006 · 506pp · 167,034 words

The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life

by Steven E. Landsburg · 1 May 2012

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Servants: A Downstairs History of Britain From the Nineteenth Century to Modern Times

by Lucy Lethbridge · 18 Nov 2013 · 457pp · 128,640 words

Wanderland

by Jini Reddy · 29 Apr 2020 · 225pp · 74,210 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

Spin

by Robert Charles Wilson · 2 Jan 2005 · 541pp · 146,445 words

The Stolen Year

by Anya Kamenetz · 23 Aug 2022 · 347pp · 103,518 words

Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own

by Garett Jones · 15 Feb 2015 · 247pp · 64,986 words

Artificial Whiteness

by Yarden Katz

The Loop: How Technology Is Creating a World Without Choices and How to Fight Back

by Jacob Ward · 25 Jan 2022 · 292pp · 94,660 words

The Classical School

by Callum Williams · 19 May 2020 · 288pp · 89,781 words

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by Thomas W. Malone · 14 May 2018 · 344pp · 104,077 words

The Metric Society: On the Quantification of the Social

by Steffen Mau · 12 Jun 2017 · 254pp · 69,276 words

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by Gary Gerstle · 14 Oct 2022 · 655pp · 156,367 words

Sickening: How Big Pharma Broke American Health Care and How We Can Repair It

by John Abramson · 15 Dec 2022 · 362pp · 97,473 words

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by Edward Fishman · 25 Feb 2025 · 884pp · 221,861 words

This Is for Everyone: The Captivating Memoir From the Inventor of the World Wide Web

by Tim Berners-Lee · 8 Sep 2025 · 347pp · 100,038 words

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by Astra Taylor · 4 Mar 2014 · 283pp · 85,824 words

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 14 Sep 2017 · 520pp · 153,517 words

Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be

by Diane Coyle · 11 Oct 2021 · 305pp · 75,697 words

Fancy Bear Goes Phishing: The Dark History of the Information Age, in Five Extraordinary Hacks

by Scott J. Shapiro · 523pp · 154,042 words

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America

by Gabriel Winant · 23 Mar 2021 · 563pp · 136,190 words

Rummage: A History of the Things We Have Reused, Recycled and Refused To Let Go

by Emily Cockayne · 15 Aug 2020

The confusion

by Neal Stephenson · 13 Apr 2004 · 1,020pp · 339,564 words

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by Brink Lindsey · 12 Oct 2017 · 288pp · 64,771 words

The Ministry for the Future: A Novel

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 5 Oct 2020 · 583pp · 182,990 words

Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire

by Brad Stone · 10 May 2021 · 569pp · 156,139 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain

by David Eagleman · 29 May 2011 · 383pp · 92,837 words

Why We Work

by Barry Schwartz · 31 Aug 2015 · 86pp · 27,453 words

The Class Ceiling: Why It Pays to Be Privileged

by Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison · 28 Jan 2019

Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress--And a Plan to Stop It

by Lawrence Lessig · 4 Oct 2011 · 538pp · 121,670 words

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by Matt Ridley · 395pp · 116,675 words

To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise

by Bethany Moreton · 15 May 2009 · 391pp · 22,799 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer-And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class

by Paul Pierson and Jacob S. Hacker · 14 Sep 2010 · 602pp · 120,848 words

Aerotropolis

by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay · 2 Jan 2009 · 603pp · 182,781 words

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by Danielle Dimartino Booth · 14 Feb 2017 · 479pp · 113,510 words

A Line in the Tar Sands: Struggles for Environmental Justice

by Tony Weis and Joshua Kahn Russell · 14 Oct 2014 · 501pp · 134,867 words

Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life

by Eric Klinenberg · 10 Sep 2018 · 281pp · 83,505 words

Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It's Doing to Us

by Will Storr · 14 Jun 2017 · 431pp · 129,071 words

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion

by Jonathan Haidt · 13 Mar 2012 · 539pp · 139,378 words

Who Owns the Future?

by Jaron Lanier · 6 May 2013 · 510pp · 120,048 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic

by John de Graaf, David Wann, Thomas H Naylor and David Horsey · 1 Jan 2001 · 378pp · 102,966 words

Life Inc.: How the World Became a Corporation and How to Take It Back

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Jun 2009 · 422pp · 131,666 words

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by Paul Tucker · 21 Apr 2018 · 920pp · 233,102 words

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

Complexity: A Guided Tour

by Melanie Mitchell · 31 Mar 2009 · 524pp · 120,182 words

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design

by Matthew Carmona, Tim Heath, Steve Tiesdell and Taner Oc · 15 Feb 2010 · 1,233pp · 239,800 words

The First Tycoon

by T.J. Stiles · 14 Aug 2009

Money: The Unauthorized Biography

by Felix Martin · 5 Jun 2013 · 357pp · 110,017 words

Losing Control: The Emerging Threats to Western Prosperity

by Stephen D. King · 14 Jun 2010 · 561pp · 87,892 words

A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Carbon Emissions

by Muhammad Yunus · 25 Sep 2017 · 278pp · 74,880 words

Shantaram: A Novel

by Gregory David Roberts · 12 Oct 2004 · 1,222pp · 385,226 words

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by Branko Milanovic · 9 Oct 2023

Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice

by Jamie K. McCallum · 15 Nov 2022 · 349pp · 99,230 words

The Revolution That Wasn't: GameStop, Reddit, and the Fleecing of Small Investors

by Spencer Jakab · 1 Feb 2022 · 420pp · 94,064 words

Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets

by Brett Scott · 4 Jul 2022 · 308pp · 85,850 words

Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture

by Kyle Chayka · 15 Jan 2024 · 321pp · 105,480 words

Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves From the American Dream

by Alissa Quart · 14 Mar 2023 · 304pp · 86,028 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

by Madhumita Murgia · 20 Mar 2024 · 336pp · 91,806 words

The Three-Body Problem (Remembrance of Earth's Past)

by Cixin Liu · 11 Nov 2014 · 420pp · 119,928 words

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life

by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky · 18 Jun 2012 · 279pp · 87,910 words

Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time

by Jeff Speck · 13 Nov 2012 · 342pp · 86,256 words

Sunfall

by Jim Al-Khalili · 17 Apr 2019 · 381pp · 120,361 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

by Jay Barbree · 18 Aug 2008 · 386pp · 92,778 words

How to Fix the Future: Staying Human in the Digital Age

by Andrew Keen · 1 Mar 2018 · 308pp · 85,880 words

Buffett

by Roger Lowenstein · 24 Jul 2013 · 612pp · 179,328 words

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition

by Charles Eisenstein · 11 Jul 2011 · 448pp · 142,946 words

Hyperion

by Dan Simmons · 15 Sep 1990 · 584pp · 170,388 words

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by Joel Mokyr · 8 Jan 2016 · 687pp · 189,243 words

Investing Demystified: How to Invest Without Speculation and Sleepless Nights

by Lars Kroijer · 5 Sep 2013 · 300pp · 77,787 words

Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age

by Virginia Eubanks · 1 Feb 2011 · 289pp · 99,936 words

Year 501

by Noam Chomsky · 19 Jan 2016

The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom

by Evgeny Morozov · 16 Nov 2010 · 538pp · 141,822 words

Occupy

by Noam Chomsky · 2 Jan 1994 · 75pp · 22,220 words

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by Mariana Mazzucato · 1 Jan 2011 · 382pp · 92,138 words

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge

by Vernor Vinge · 30 Sep 2001 · 659pp · 203,574 words

How Did We Get Into This Mess?: Politics, Equality, Nature

by George Monbiot · 14 Apr 2016 · 334pp · 82,041 words

The Battery: How Portable Power Sparked a Technological Revolution

by Henry Schlesinger · 16 Mar 2010 · 336pp · 92,056 words

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Blyth · 24 Apr 2013 · 576pp · 105,655 words

It's Better Than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear

by Gregg Easterbrook · 20 Feb 2018 · 424pp · 119,679 words

The Techno-Human Condition

by Braden R. Allenby and Daniel R. Sarewitz · 15 Feb 2011

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

by Arlie Russell Hochschild · 5 Sep 2016 · 435pp · 120,574 words

The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

by Robert Zubrin · 30 Apr 2019 · 452pp · 126,310 words

Fantasyland

by Kurt Andersen · 5 Sep 2017

99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It

by Mark Thomas · 7 Aug 2019 · 286pp · 79,305 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski · 5 Mar 2019 · 202pp · 62,901 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

Ambition, a History

by William Casey King · 14 Sep 2013 · 317pp · 84,674 words

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor

by David S. Landes · 14 Sep 1999 · 1,060pp · 265,296 words

Underground

by Suelette Dreyfus · 1 Jan 2011 · 547pp · 160,071 words

The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention

by William Rosen · 31 May 2010 · 420pp · 124,202 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen

by James Suzman · 10 Jul 2017

Saturn's Children

by Charles Stross · 30 Jun 2008 · 360pp · 110,929 words

Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the US City

by Mike Davis · 27 Aug 2001

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth

by Sarah Smarsh · 17 Sep 2018 · 279pp · 90,278 words

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 2002 · 901pp · 234,905 words

Fifty Degrees Below

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 25 Oct 2005 · 560pp · 158,238 words

The God Delusion

by Richard Dawkins · 12 Sep 2006 · 478pp · 142,608 words

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1997 · 1,106pp · 335,322 words

The Inequality Puzzle: European and US Leaders Discuss Rising Income Inequality

by Roland Berger, David Grusky, Tobias Raffel, Geoffrey Samuels and Chris Wimer · 29 Oct 2010 · 237pp · 72,716 words

Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am

by Robert Gandt · 1 Mar 1995 · 371pp · 101,792 words

Empire of Guns

by Priya Satia · 10 Apr 2018 · 927pp · 216,549 words

Schild's Ladder

by Greg Egan · 31 Dec 2003 · 353pp · 101,130 words

Patriot Games

by Tom Clancy · 2 Jan 1987

Darwin Among the Machines

by George Dyson · 28 Mar 2012 · 463pp · 118,936 words

Debunking Economics - Revised, Expanded and Integrated Edition: The Naked Emperor Dethroned?

by Steve Keen · 21 Sep 2011 · 823pp · 220,581 words

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration

by Isabel Wilkerson · 6 Sep 2010 · 740pp · 227,963 words

The Snow Queen

by Joan D. Vinge · 1 Feb 2001 · 687pp · 191,073 words

Vultures' Picnic: In Pursuit of Petroleum Pigs, Power Pirates, and High-Finance Carnivores

by Greg Palast · 14 Nov 2011 · 493pp · 132,290 words

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

Democracy for Sale: Dark Money and Dirty Politics

by Peter Geoghegan · 2 Jan 2020 · 388pp · 111,099 words

Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire

by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson · 15 Jan 2019 · 502pp · 128,126 words

Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming

by Mckenzie Funk · 22 Jan 2014 · 337pp · 101,281 words

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by Alex Zevin · 12 Nov 2019 · 767pp · 208,933 words

The Demon in the Machine: How Hidden Webs of Information Are Finally Solving the Mystery of Life

by Paul Davies · 31 Jan 2019 · 253pp · 83,473 words

The Passenger: Berlin

by The Passenger · 8 Jun 2021 · 199pp · 63,724 words

The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas

by Janek Wasserman · 23 Sep 2019 · 470pp · 130,269 words

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by Judith Stein · 30 Apr 2010 · 497pp · 143,175 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right

by Jennifer Burns · 18 Oct 2009 · 495pp · 144,101 words

Braiding Sweetgrass

by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by Jeremias Prassl · 7 May 2018 · 491pp · 77,650 words

Capital Ideas Evolving

by Peter L. Bernstein · 3 May 2007

The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as if the Future Matters

by Diane Coyle · 21 Feb 2011 · 523pp · 111,615 words

Apollo's Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live

by Nicholas A. Christakis · 27 Oct 2020 · 475pp · 127,389 words

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design

by Charles Montgomery · 12 Nov 2013 · 432pp · 124,635 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

by Andrew Yang · 2 Apr 2018 · 300pp · 76,638 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

The Profiteers

by Sally Denton · 556pp · 141,069 words

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

by Nancy Isenberg · 20 Jun 2016 · 709pp · 191,147 words

Methland: The Death and Life of an American Small Town

by Nick Reding · 1 Jul 2009 · 250pp · 83,367 words

To the Ends of the Earth: Scotland's Global Diaspora, 1750-2010

by T M Devine · 25 Aug 2011

Team Human

by Douglas Rushkoff · 22 Jan 2019 · 196pp · 54,339 words

Stealth of Nations

by Robert Neuwirth · 18 Oct 2011 · 340pp · 91,387 words

A Beautiful Mind

by Sylvia Nasar · 11 Jun 1998 · 998pp · 211,235 words

Red Moon

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 22 Oct 2018 · 492pp · 141,544 words

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

Nuclear War and Environmental Catastrophe

by Noam Chomsky and Laray Polk · 29 Apr 2013

Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order

by Noam Chomsky · 6 Sep 2011

Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts

by Jill Abramson · 5 Feb 2019 · 788pp · 223,004 words

Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health

by H. Gilbert Welch, Lisa M. Schwartz and Steven Woloshin · 18 Jan 2011 · 302pp · 92,546 words

The Cardinal of the Kremlin

by Tom Clancy · 2 Jan 1988

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by James C. Scott · 8 Feb 1999 · 607pp · 185,487 words

The Dreaming Void

by Peter F. Hamilton · 1 Jan 2007 · 773pp · 214,465 words

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

by Adam Winkler · 27 Feb 2018 · 581pp · 162,518 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History

by Kurt Andersen · 4 Sep 2017 · 522pp · 162,310 words

The Asian Financial Crisis 1995–98: Birth of the Age of Debt

by Russell Napier · 19 Jul 2021 · 511pp · 151,359 words

What About Me?: The Struggle for Identity in a Market-Based Society

by Paul Verhaeghe · 26 Mar 2014 · 208pp · 67,582 words

The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us

by Robert H. Frank, Philip J. Cook · 2 May 2011

I'm Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59

by Douglas Edwards · 11 Jul 2011 · 496pp · 154,363 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

A Small Farm Future: Making the Case for a Society Built Around Local Economies, Self-Provisioning, Agricultural Diversity and a Shared Earth

by Chris Smaje · 14 Aug 2020 · 375pp · 105,586 words

Women Talk Money: Breaking the Taboo

by Rebecca Walker · 15 Mar 2022 · 322pp · 106,663 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier

by Ian Urbina · 19 Aug 2019

No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Apr 2015 · 324pp · 93,606 words

Shutdown: How COVID Shook the World's Economy

by Adam Tooze · 15 Nov 2021 · 561pp · 138,158 words

The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order

by Benn Steil · 14 May 2013 · 710pp · 164,527 words

The Great American Stickup: How Reagan Republicans and Clinton Democrats Enriched Wall Street While Mugging Main Street

by Robert Scheer · 14 Apr 2010 · 257pp · 64,763 words

Reskilling America: Learning to Labor in the Twenty-First Century

by Katherine S. Newman and Hella Winston · 18 Apr 2016 · 338pp · 92,465 words

Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World

by Liaquat Ahamed · 22 Jan 2009 · 708pp · 196,859 words

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by John Darwin · 5 Feb 2008 · 650pp · 203,191 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought

by Ayn Rand, Leonard Peikoff and Peter Schwartz · 1 Jan 1989 · 411pp · 136,413 words

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by James Rickards · 7 Apr 2014 · 466pp · 127,728 words

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

by Naomi Klein · 15 Sep 2014 · 829pp · 229,566 words

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

by Robert Fisk · 2 Jan 2005 · 1,800pp · 596,972 words

The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities

by John J. Mearsheimer · 24 Sep 2018 · 443pp · 125,510 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

by Dan Ariely · 19 Feb 2007 · 383pp · 108,266 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

Zeitgeist

by Bruce Sterling · 1 Nov 2000 · 333pp · 86,662 words

Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now

by Douglas Rushkoff · 21 Mar 2013 · 323pp · 95,939 words

New York 2140

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 14 Mar 2017 · 693pp · 204,042 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

The America That Reagan Built

by J. David Woodard · 15 Mar 2006

Leading From the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies

by Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer · 14 Apr 2013 · 351pp · 93,982 words

Owning the Sun

by Alexander Zaitchik · 7 Jan 2022 · 341pp · 98,954 words

Please Report Your Bug Here: A Novel

by Josh Riedel · 17 Jan 2023 · 287pp · 85,518 words

The Midnight Library

by Matt Haig · 12 Aug 2020 · 291pp · 72,937 words

Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus

by Rick Perlstein · 17 Mar 2009 · 1,037pp · 294,916 words

There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America

by Brian Goldstone · 25 Mar 2025 · 512pp · 153,059 words

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company That Addicted America

by Beth Macy · 4 Mar 2019 · 441pp · 124,798 words

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

by Brian Merchant · 25 Sep 2023 · 524pp · 154,652 words

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal

by M. Mitchell Waldrop · 14 Apr 2001

The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution

by Richard Dawkins · 21 Sep 2009

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

Business Lessons From a Radical Industrialist

by Ray C. Anderson · 28 Mar 2011 · 412pp · 113,782 words

Running Money

by Andy Kessler · 4 Jun 2007 · 323pp · 92,135 words

The Ripple Effect: The Fate of Fresh Water in the Twenty-First Century

by Alex Prud'Homme · 6 Jun 2011 · 692pp · 167,950 words

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

Daemon

by Daniel Suarez · 1 Dec 2006 · 562pp · 146,544 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously About the Planet

by Roger Scruton · 30 Apr 2014 · 426pp · 118,913 words

Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems

by Didier Sornette · 18 Nov 2002 · 442pp · 39,064 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 20 Feb 2018 · 306pp · 82,765 words

Evidence-Based Technical Analysis: Applying the Scientific Method and Statistical Inference to Trading Signals

by David Aronson · 1 Nov 2006

The Big U

by Neal Stephenson · 2 Jan 1984 · 344pp · 103,532 words

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by Charles Handy · 12 Mar 2015 · 164pp · 57,068 words

Brazillionaires: The Godfathers of Modern Brazil

by Alex Cuadros · 1 Jun 2016 · 433pp · 125,031 words

Ethics in Investment Banking

by John N. Reynolds and Edmund Newell · 8 Nov 2011 · 193pp · 11,060 words

Hopes and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Jan 2009

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by Branko Milanovic · 10 Apr 2016 · 312pp · 91,835 words

Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn

by Chris Hughes · 20 Feb 2018 · 173pp · 53,564 words

Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy

by Lawrence Lessig · 2 Jan 2009

How Will Capitalism End?

by Wolfgang Streeck · 8 Nov 2016 · 424pp · 115,035 words

The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry

by Gary Greenberg · 1 May 2013 · 480pp · 138,041 words

Wool Omnibus Edition

by Hugh Howey · 5 Jun 2012

How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 5 Oct 2015 · 424pp · 121,425 words

Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time

by James Suzman · 2 Sep 2020 · 909pp · 130,170 words

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

Licence to be Bad

by Jonathan Aldred · 5 Jun 2019 · 453pp · 111,010 words

The Rare Metals War

by Guillaume Pitron · 15 Feb 2020 · 249pp · 66,492 words

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

by Richard Heinberg · 1 Jun 2011 · 372pp · 107,587 words

New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI

by Frank Pasquale · 14 May 2020 · 1,172pp · 114,305 words

The 5 Types of Wealth: A Transformative Guide to Design Your Dream Life

by Sahil Bloom · 4 Feb 2025 · 363pp · 94,341 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain

by Brett Christophers · 6 Nov 2018

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi · 1 Jul 2008 · 453pp · 132,400 words

Who Stole the American Dream?

by Hedrick Smith · 10 Sep 2012 · 598pp · 172,137 words

Worn: A People's History of Clothing

by Sofi Thanhauser · 25 Jan 2022 · 592pp · 133,460 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

Rage Inside the Machine: The Prejudice of Algorithms, and How to Stop the Internet Making Bigots of Us All

by Robert Elliott Smith · 26 Jun 2019 · 370pp · 107,983 words

The Quants

by Scott Patterson · 2 Feb 2010 · 374pp · 114,600 words

Firefighting

by Ben S. Bernanke, Timothy F. Geithner and Henry M. Paulson, Jr. · 16 Apr 2019

Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the World

by Tom Burgis · 7 Sep 2020 · 476pp · 139,761 words

Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia

by Dariusz Jemielniak · 13 May 2014 · 312pp · 93,504 words

How to Be a Liberal: The Story of Liberalism and the Fight for Its Life

by Ian Dunt · 15 Oct 2020

The Cigarette: A Political History

by Sarah Milov · 1 Oct 2019

The Locavore's Dilemma

by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu · 29 May 2012 · 329pp · 85,471 words

When Free Markets Fail: Saving the Market When It Can't Save Itself (Wiley Corporate F&A)

by Scott McCleskey · 10 Mar 2011

Let them eat junk: how capitalism creates hunger and obesity

by Robert Albritton · 31 Mar 2009 · 273pp · 93,419 words

Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery

by Henry Marsh · 3 May 2017 · 257pp · 84,498 words

Age of Anger: A History of the Present

by Pankaj Mishra · 26 Jan 2017 · 410pp · 106,931 words

Conscious Capitalism, With a New Preface by the Authors: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business

by John Mackey, Rajendra Sisodia and Bill George · 7 Jan 2014 · 335pp · 104,850 words

When More Is Not Better: Overcoming America's Obsession With Economic Efficiency

by Roger L. Martin · 28 Sep 2020 · 600pp · 72,502 words

The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis

by Jeremy Rifkin · 31 Dec 2009 · 879pp · 233,093 words

Modern Monopolies: What It Takes to Dominate the 21st Century Economy

by Alex Moazed and Nicholas L. Johnson · 30 May 2016 · 324pp · 89,875 words

A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

by Bruce Cannon Gibney · 7 Mar 2017 · 526pp · 160,601 words

After the Fall: Being American in the World We've Made

by Ben Rhodes · 1 Jun 2021 · 342pp · 114,118 words

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

The End of Absence: Reclaiming What We've Lost in a World of Constant Connection

by Michael Harris · 6 Aug 2014 · 259pp · 73,193 words

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe

by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Alex Hyde-White · 24 Oct 2016 · 515pp · 142,354 words

Tomorrow's Capitalist: My Search for the Soul of Business

by Alan Murray · 15 Dec 2022 · 263pp · 77,786 words

The Billion-Dollar Molecule

by Barry Werth · 543pp · 163,997 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

We Need New Stories: Challenging the Toxic Myths Behind Our Age of Discontent

by Nesrine Malik · 4 Sep 2019

Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town

by Lamorna Ash · 1 Apr 2020 · 319pp · 108,797 words

Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C

by Bruce Schneier · 10 Nov 1993

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 2 Jul 2009 · 387pp · 110,820 words

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

by Lawrence Lessig · 14 Jul 2001 · 494pp · 142,285 words

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by Jonathan Taplin · 17 Apr 2017 · 222pp · 70,132 words

India's Long Road

by Vijay Joshi · 21 Feb 2017

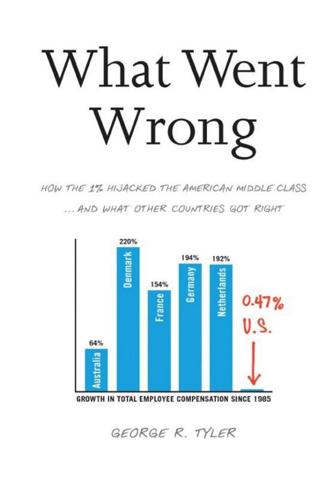

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

by Joshua B. Freeman · 27 Feb 2018 · 538pp · 145,243 words

The Boy Who Could Change the World: The Writings of Aaron Swartz

by Aaron Swartz and Lawrence Lessig · 5 Jan 2016 · 377pp · 110,427 words

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World

by General Stanley McChrystal, Tantum Collins, David Silverman and Chris Fussell · 11 May 2015 · 409pp · 105,551 words

Utopia Is Creepy: And Other Provocations

by Nicholas Carr · 5 Sep 2016 · 391pp · 105,382 words

1967: Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East

by Tom Segev · 2 Jan 2007 · 1,145pp · 310,655 words

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by Margaret O'Mara · 8 Jul 2019

The Ape That Understood the Universe: How the Mind and Culture Evolve

by Steve Stewart-Williams · 12 Sep 2018 · 1,132pp · 156,379 words

Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt

by Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco · 7 Apr 2014 · 326pp · 88,905 words

Dollars and Sense: How We Misthink Money and How to Spend Smarter

by Dr. Dan Ariely and Jeff Kreisler · 7 Nov 2017 · 302pp · 87,776 words

Making It in America: The Almost Impossible Quest to Manufacture in the U.S.A. (And How It Got That Way)

by Rachel Slade · 9 Jan 2024 · 392pp · 106,044 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy

by Nick Romeo · 15 Jan 2024 · 343pp · 103,376 words

The Name of the Rose

by Umberto Eco · 26 Sep 2006 · 1,166pp · 373,031 words

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by Alec Ross · 13 Sep 2021 · 363pp · 109,077 words

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

Risk: A User's Guide

by Stanley McChrystal and Anna Butrico · 4 Oct 2021 · 489pp · 106,008 words

Social Democratic America

by Lane Kenworthy · 3 Jan 2014 · 283pp · 73,093 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

A Fraction of the Whole

by Steve Toltz · 12 Feb 2008 · 773pp · 220,140 words

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 22 Oct 2018 · 402pp · 126,835 words

A Man for All Markets

by Edward O. Thorp · 15 Nov 2016 · 505pp · 142,118 words

The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World

by Jeremy Rifkin · 27 Sep 2011 · 443pp · 112,800 words

The Irrational Economist: Making Decisions in a Dangerous World

by Erwann Michel-Kerjan and Paul Slovic · 5 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 108,119 words

The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom

by Jonathan Haidt · 26 Dec 2005 · 405pp · 130,840 words

The Limits of the Market: The Pendulum Between Government and Market

by Paul de Grauwe and Anna Asbury · 12 Mar 2017

Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City

by Peter D. Norton · 15 Jan 2008 · 409pp · 145,128 words

Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing

by Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman · 20 Nov 2012 · 307pp · 92,165 words

Future Tense: Jews, Judaism, and Israel in the Twenty-First Century

by Jonathan Sacks · 19 Apr 2010 · 305pp · 97,214 words

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World

by Laura Spinney · 31 May 2017

Names for the Sea

by Sarah Moss · 27 Apr 2018

Among the Braves: Hope, Struggle, and Exile in the Battle for Hong Kong and the Future of Global Democracy

by Shibani Mahtani and Timothy McLaughlin · 7 Nov 2023 · 348pp · 110,533 words

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by Nate Silver · 31 Aug 2012 · 829pp · 186,976 words

The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America's Food Business

by Christopher Leonard · 18 Feb 2014 · 444pp · 128,701 words

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel · 7 Sep 2020 · 209pp · 53,175 words

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

Microchip: An Idea, Its Genesis, and the Revolution It Created

by Jeffrey Zygmont · 15 Mar 2003

Thinking in Systems: A Primer

by Meadows. Donella and Diana Wright · 3 Dec 2008 · 243pp · 66,908 words

This Is Memorial Device

by David Keenan · 15 Feb 2017 · 410pp · 99,654 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

Pity the Billionaire: The Unexpected Resurgence of the American Right

by Thomas Frank · 16 Aug 2011 · 261pp · 64,977 words

The new village green: living light, living local, living large

by Stephen Morris · 1 Sep 2007 · 289pp · 112,697 words

The power broker : Robert Moses and the fall of New York

by Caro, Robert A · 14 Apr 1975

The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable

by Amitav Ghosh · 16 Jan 2018

George Marshall: Defender of the Republic

by David L. Roll · 8 Jul 2019

The Scandal of Money

by George Gilder · 23 Feb 2016 · 209pp · 53,236 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom

by Graham Farmelo · 24 Aug 2009 · 1,396pp · 245,647 words

After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

by Tripp Mickle · 2 May 2022 · 535pp · 149,752 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

The Green New Deal: Why the Fossil Fuel Civilization Will Collapse by 2028, and the Bold Economic Plan to Save Life on Earth

by Jeremy Rifkin · 9 Sep 2019 · 327pp · 84,627 words

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community

by Ray Oldenburg · 17 Aug 1999

The Wake-Up Call: Why the Pandemic Has Exposed the Weakness of the West, and How to Fix It

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 1 Sep 2020 · 134pp · 41,085 words

Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love

by Simran Sethi · 10 Nov 2015 · 396pp · 112,832 words

How to Run a Government: So That Citizens Benefit and Taxpayers Don't Go Crazy

by Michael Barber · 12 Mar 2015 · 350pp · 109,379 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet (Information Policy)

by Benjamin Peters · 2 Jun 2016 · 518pp · 107,836 words

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by Marc Levinson · 31 Jul 2016 · 409pp · 118,448 words

The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America

by Warren E. Buffett and Lawrence A. Cunningham · 2 Jan 1997 · 219pp · 15,438 words

Chomsky on Mis-Education

by Noam Chomsky · 24 Mar 2000

The Fire Starter Sessions: A Soulful + Practical Guide to Creating Success on Your Own Terms

by Danielle Laporte · 16 Apr 2012 · 203pp · 58,817 words

Austerity Britain: 1945-51

by David Kynaston · 12 May 2008 · 870pp · 259,362 words

Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey Into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley

by Corey Pein · 23 Apr 2018 · 282pp · 81,873 words

Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money That We Understand to Money That Understands Us (Perspectives)

by David Birch · 14 Jun 2017 · 275pp · 84,980 words

Against Intellectual Monopoly

by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine · 6 Jul 2008 · 607pp · 133,452 words

The End of Doom: Environmental Renewal in the Twenty-First Century

by Ronald Bailey · 20 Jul 2015 · 417pp · 109,367 words

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

The Streets Were Paved With Gold

by Ken Auletta · 14 Jul 1980 · 407pp · 135,242 words

The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers

by Richard McGregor · 8 Jun 2010

Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (And What It Says About Us)

by Tom Vanderbilt · 28 Jul 2008 · 512pp · 165,704 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Money: 5,000 Years of Debt and Power

by Michel Aglietta · 23 Oct 2018 · 665pp · 146,542 words

First Friends: The Powerful, Unsung (And Unelected) People Who Shaped Our Presidents

by Gary Ginsberg · 14 Sep 2021 · 418pp · 134,401 words

Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity

by Edward Tenner · 8 Jun 2004 · 423pp · 126,096 words

Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World

by Jeffrey Tucker · 7 Jan 2015

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

1948. A Soldier's Tale – the Bloody Road to Jerusalem

by Uri Avnery and Christopher Costello · 14 Jul 2008 · 535pp · 147,528 words

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception

by George A. Akerlof, Robert J. Shiller and Stanley B Resor Professor Of Economics Robert J Shiller · 21 Sep 2015 · 274pp · 93,758 words

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future

by Laurence C. Smith · 22 Sep 2010 · 421pp · 120,332 words

The Art of SQL

by Stephane Faroult and Peter Robson · 2 Mar 2006 · 480pp · 122,663 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

The Fallen Blade: Act One of the Assassini

by Jon Courtenay Grimwood · 27 Jan 2011 · 470pp · 118,051 words

Democracy Incorporated

by Sheldon S. Wolin · 7 Apr 2008 · 637pp · 128,673 words

Decline of the English Murder

by George Orwell · 24 Jul 2009 · 96pp · 33,963 words

Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History

by Stephen Jay Gould · 1 Jan 1977 · 266pp · 76,299 words

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences

by Rob Kitchin · 25 Aug 2014

Big Data and the Welfare State: How the Information Revolution Threatens Social Solidarity

by Torben Iversen and Philipp Rehm · 18 May 2022

China's Great Wall of Debt: Shadow Banks, Ghost Cities, Massive Loans, and the End of the Chinese Miracle

by Dinny McMahon · 13 Mar 2018 · 290pp · 84,375 words

Begin the World Over

by Kung Li Sun · 14 Jun 2022 · 288pp · 84,613 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

On Grand Strategy

by John Lewis Gaddis · 3 Apr 2018 · 461pp · 109,656 words

Shorting the Grid: The Hidden Fragility of Our Electric Grid

by Meredith. Angwin · 18 Oct 2020 · 376pp · 101,759 words

Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex

by Rupert Darwall · 2 Oct 2017 · 451pp · 115,720 words

In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan

by Seth G. Jones · 12 Apr 2009 · 566pp · 144,072 words

Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World

by Kwasi Kwarteng · 14 Aug 2011 · 670pp · 169,815 words

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations

by Jacob Soll · 28 Apr 2014 · 382pp · 105,166 words

Trading Risk: Enhanced Profitability Through Risk Control

by Kenneth L. Grant · 1 Sep 2004

Free Market Missionaries: The Corporate Manipulation of Community Values

by Sharon Beder · 30 Sep 2006 · 273pp · 34,920 words

An Edible History of Humanity

by Tom Standage · 30 Jun 2009 · 282pp · 82,107 words

And Then All Hell Broke Loose: Two Decades in the Middle East

by Richard Engel · 9 Feb 2016 · 251pp · 67,801 words

Powers and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 16 Sep 2015

The End of Wall Street

by Roger Lowenstein · 15 Jan 2010 · 460pp · 122,556 words

Imperial Ambitions: Conversations on the Post-9/11 World