A Brief History of Motion: From the Wheel, to the Car, to What Comes Next

by

Tom Standage

Published 16 Aug 2021

Because such licenses had to be purchased annually, part-time jitney driving was effectively outlawed. Other rules prevented jitneys from driving on streets with streetcar rails, picking up passengers from streetcar stops, or passing streetcars or buses. In some cities, groups of jitney drivers mounted legal challenges. But by the end of 1915, anti-jitney rules had been introduced in 125 of the 175 cities where jitneys operated; the remaining cities followed suit the next year. Some jitney drivers switched to become taxi drivers, but most did not. The jitney experiment was over less than three years after it had begun. Banning jitneys did nothing to alleviate traffic congestion because some riders responded by buying their own cars, rather than going to back to streetcars.

…

By this time the idea had spread to San Francisco, where at least six jitneys were operating on Market Street. The jitney craze spread rapidly as newspapers across America wrote about it, instantly prompting drivers and riders in new cities to try it. In Kansas City, for example, the number of jitneys went from zero to two hundred in two weeks, carrying twenty-five thousand passengers a day—and twice that number two weeks later. By the summer of 1915, sixty-two thousand jitneys were operating in cities across the United States. One contemporary report referred to “The Jitney Invasion.” Because most cars were open bodied, jitneys were most popular in warm, dry parts of the country.

…

Streetcar companies in many cities were resented for prioritizing high returns for their investors over service to riders. So jitneys were hailed, like omnibuses before them, as emblems of freedom. They represented “a new page in the history of locomotion when convenience and economy came together,” declared one jitney enthusiast in the Independent newspaper in May 1915. “Nothing can stop the jitney now, no corporation, no legislation. The era of extortion and of corruption is over.” A car being used as a jitney in New York, 1915. That prediction proved to be wide of the mark. Streetcar companies lobbied furiously against jitneys. The Electric Railway Journal denounced them as “a menace,” “a malignant growth,” and “this Frankenstein of transportation.”

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

They relied on workers who were struggling as a result of the recession, and were “often yesterday’s unemployed locomotive engineer, policeman, bartender, printer, barber, or clerk.”1 Due to the cost of the vehicle, depreciation, and various other costs such as fuel and maintenance, it was unlikely that many jitney drivers were actually making a profit, and as a result there was a high turnover. The real beneficiaries of these drivers’ precarity were the customers: businessmen, people “with a high valuation of time,” and some younger people; as fares increased at peak times, taking a jitney was largely unaffordable to lower-income residents.2 As jitneys pulled riders from streetcars and, in some cities, caused traffic that delayed them, streetcars began losing money. Unlike jitneys, which originally paid little in taxes or fees, the private streetcar companies of the time had significant obligations written into their municipal franchise agreements.

…

But there was another big issue that accelerated the need to do something about jitneys. For their time, jitneys were fast. They could get a rider to their destination far quicker than a streetcar—that was the main benefit riders were paying for—and speed also allowed the drivers to complete more rides, and so earn more money. However, automobiles and streetcars were not the only vehicles navigating the streets; there were still plenty of people using them, and jitneys created a new hazard. In Los Angeles, collisions had increased 22 percent by March 1915 and jitneys were involved in 26 percent of all traffic accidents.3 This trend was replicated in every city where jitneys operated.

…

In Los Angeles, collisions had increased 22 percent by March 1915 and jitneys were involved in 26 percent of all traffic accidents.3 This trend was replicated in every city where jitneys operated. They also had a reputation for being used for abductions, robberies, and rapes. Through 1915 and 1916, cities across the United States regulated jitneys by requiring them to carry insurance, get proper licensing, pay taxes, and observe other requirements that varied by city. There were estimated to be 62,000 jitneys in service at their peak in 1915, but by October 1918 there were fewer than 5,900 remaining, and their numbers continued to decline. The jitney was dead, but that did not mean the streetcar returned to its dominant position.

Machinery of Freedom: A Guide to Radical Capitalism

by

David Friedman

Published 2 Jan 1978

The cost is low because my transit system is already over 99 percent built; its essence is the more efficient use of our present multibillion dollar investment in roads and automobiles. I call it jitney transit; it can most easily be thought of as something between taxicabs and hitch-hiking. Jitney stops, like present-day bus stops, would be arranged conveniently about the city. A commuter heading into town with an empty car would stop at the first jitney stop he came to and pick up any passengers going his way. He would proceed along his normal route, dropping off passengers when he passed their stops. Each passenger would pay a fee, according to an existing schedule listing the price between any pair of stops.

…

Both of these books describe what really happened during the Industrial Revolution and how it got reported by historians. Ross D. Eckert and George W. Hilton, 'The Jitneys', Journal of Law and Economics XV (October 1972), pp. 293-325. This article is the historical background for Chapter 16. It describes the brief flourishing of jitneys in America and how the trolly companies, unable to win on the economic market, succeeded in legislating the jitneys out of existence. Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr., The Decline of American Liberalism, rev. ed., (New York: Atheneum, 1980). The author uses "liberalism" not in its modern sense of democratic socialism in dilute solution but in its old sense of support for freedom — roughly speaking, libertarianism.

…

Furthermore, cars already exist and are being driven hither and yon in great numbers; the additional cost of jitney transit is merely the cost of setting up the stops and arranging price schedules and the like. Would commuters be willing to carry passengers? Given certain conditions, which I will deal with later, yes; the additional income from doing so would be far from trivial. Assume a charge of $2 a head. A commuter who regularly carried four passengers each way, five days a week, would make $4,000 a year — no mean sum. He would also convert his automobile, for tax purposes, into a business expense. There are two difficulties with jitney transit. The first is safety; the average driver is not eager to pick up strangers.

The Docks

by

Bill Sharpsteen

Published 5 Jan 2011

They piled the cargo on the dock, where clerks counted the boxes and confirmed that the cargo matched the manifest. A jitney, a truck with a small cab, waited to take the cargo away to the warehouse for temporary storage. Jitneys, sometimes called Fordsoms, had magneto engines that made an incredible racket when revved up, but they were powerful little trucks, able to pull a four-wheeler loaded with cargo. To support the load, the four-wheelers had heavy rubber wheels and were connected to the jitney with a hook called a stinger, named for the obvious pain it would inflict if it landed on someone’s foot. Once they took the cargo to the warehouse, the jitney drivers brought back an empty four-wheeler for another load.

…

In the same vein, longshoremen embraced the concept of multiple handling, which stipulated that cargo coming off a ship must actually touch the so-called skin of the dock. Thus once a loaded lift board was set down on the dock, the cargo couldn’t go anywhere until it had been hauled off the pallet onto the dock by longshoremen and then onto a jitney’s four-wheeler by Teamsters, who had jurisdiction at the time over loading and unloading trucks and trains. ╯ ╯ ╯ ╯ ╯ The Hold Menâ•… /â•… 193 In fairness, this also allowed clerks to easily check the cargo against their manifests before it went to the warehouse. But even the union recognized there was something less than efficient about the practice, and it no doubt occurred to everyone involved that a lift board could be loaded directly onto or off a four-wheeler.

…

That was the tradition in San Pedro, and no matter how seductively some other vocation called, you listened to your father first. He tried taking accountant classes at night school, but that fizzled, and he became a full-time clerk whose main ambition was to stay alive, always an issue for a clerk standing amid the swinging cargo loads and rushing jitneys. He also had to wonder whether this was such a great deal: back then, clerks barely worked during the slow winter times, and he had to collect unemployment occasionally to pay the bills. It helped that he was single and could live simply. Just the same, the job had a basic honesty about it he liked.

Straight to Hell: True Tales of Deviance, Debauchery, and Billion-Dollar Deals

by

John Lefevre

Published 4 Nov 2014

It’s my first time there. I have a colleague who usually calls dibs on the Manila business trips. Given his infatuation with love monkeys and the fact that he still lives with his parents, I don’t object. The weekend festivities kick off in local style—a private jitney from the hotel to the Hobbit House. Not to be confused with the Hampton Jitney, a Manila jitney is a semi-open-air hybrid between a taxi and a bus, constructed from old World War II vehicles that the US government abandoned in the Philippines at the end of the war, complete with long bench seating. They have become a ubiquitous symbol of the local culture and tend to be ornately painted and operated by colorful street entrepreneurs.

…

They have become a ubiquitous symbol of the local culture and tend to be ornately painted and operated by colorful street entrepreneurs. Typically, they are used to haul lower-class people long distances to their soul-crushing jobs, while crammed into an aluminum cattle car and forced to endure sweltering heat, shocking pollution, and agonizing traffic. Tonight, the jitney is like a Disney ride tour of the Valley of Ashes for a dozen investment bankers, most of whom clear seven-figure bonuses. When our driver pulls into the Shangri-La and sees our group standing there, his eyes light up. He knows he’s in for a night of abuse and torture, but he’ll come away with more than an extra month’s salary in his pocket.

…

Apparently, the Hobbit House isn’t what it once might have been, or perhaps never was. It’s quite possible that we have mistaken it for the Ringside Bar in Makati, home (to this day) of midget wrestling, boxing, tossing and all-around belittling. Having been abruptly asked to leave, it’s time to jitney over to Burgos Street, the reddest street in the red-light district that is Manila. This is primarily the reason we’re staying in Makati—Burgos Street is a strip of provocative neon lights and poorly lit bars for expats who seek the company of exotic Filipina girls, while watching dance shows and consuming cheap booze.

Kiln People

by

David Brin

Published 15 Jan 2002

Real people still occupy some of the tallest buildings, where prestigious views are best appreciated by organic eyes. But the rest of Old Town has become a land of ghosts and golems, commuting to work each morning fresh from their owners' kilns. It's an austere realm, both tattered and colorful as zeroxed laborers file off jitneys, camionetas, and buses, their brightly colored bodies wrapped in equally bright and equally disposable paper clothes. We had to finish our raid before that daily influx of clay people arrived, so Blane hurriedly organized his rented troops in predawn twilight, two blocks from the Teller Building.

…

Escaping turned out to be much easier than breaking in -- (too easy?) -- though Beta soon recovered and gave chase. Now I was back and victorious, right? Shutting down this operation must be a real blow to Beta's piracy enterprise. So why did I feel a sense of incompletion? Strolling away from the traffic noise -- a braying cacophony of jitney horns and bellowing dinos -- I found myself confronting an alley marked by ribbons of flickertape, specially tuned to irritate any natural human eye. "Stay Out!" the fluttering tape yammered. "Structural Danger! Stay Out!" Such warnings -- visible only to realfolk -- are growing commonplace as buildings in this part of town suffer neglect.

…

Nowadays shopping is either a chore -- you ask House to arrange deliveries -- or else you do it for pleasure, strolling in person along tree-lined avenues like Realpeople Lane, where balmy venturi breezes flow all year round. Either way, it's hard to picture why our parents did it in sunless grottos. A fluorescent-lit catacomb is no proper world for human beings. So now malls are set aside for the new servant class. Us clayfolk. Jitneys and scooters zip around the vast parking structure, conveying fresh dittos to clients all over town. And not just any dittos. Most bear specialized colors. Snow white for sensuality. Ebony for undiluted intellect. A particular scarlet that's oblivious to pain ... and another that experiences everything with fierce intensity.

The End of Traffic and the Future of Transport: Second Edition

by

David Levinson

and

Kevin Krizek

Published 17 Aug 2015

They face the dilemma that passengers must forego any demand for schedule flexibility. There will not be a vanpool following if you miss this one. Jitneys. Today Via, a smartphone app-powered service operating in Manhattan advertises "Smarter than the subway. Better than the bus. Cheaper than the taxi."241 Often illegal dollar vans have long served immigrant communities in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami, serving over 100,000 riders a day in New York.242 These jitney services run regular routes based on where the market lies, serving a particular set of passengers better than competing modes. The risks with such services are poaching from traditional transit services, which have developed markets in the first place.

…

They are licensed drivers, and any licensed driver (above a certain age and level of experience) is eligible to carry passengers. The cars are private cars (at least sometimes) though that is little different than how taxis operate in other parts of the world. Many Singaporean taxi drivers will take fares when going between where they are going anyway, but otherwise treat the taxis as a personal vehicle. Lyft now does jitney (shared taxi, dollar van, informal transport) type services, dubbed Lyft Line. (Uber has the similar UberPool) These serve either one pickup going to multiple destinations, or multiple pickups going to one destination, or multiple origins to multiple destinations, and compete with both taxi and public transit.

Planet of Slums

by

Mike Davis

Published 1 Mar 2006

One police official reportedly urged his men: "From tomorrow, I need reports on my desk saying that we have shot people. The President has given his full support for this operation so there is nothing to fear. You should treat this operation as war."64 And the police did. Stalls and inventories were systematically burned or looted, and more than 17,000 traders and jitney drivers were arrested. A week later, the police began to bulldoze shacks in MDC strongholds as well as in pro-Mugabe slums (Chimoi and Nyadzonio, for instance) that were located in areas coveted for redevelopment. In one case, Hatcliffe Extension west of Harare, the police evicted 63 Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, "Housing by People in Asia," as well as press releases from the Asian Human Rights Commission and Urban Poor Consortium (see Urban Poor website: www.urbanpoor.or.id). 64 Munyaradzi Gwisai, "Mass Action Can Stop Operation Murambasvina," International Socialist Organisation (Zimbabwe), 30 May 2005; BBC News, 27 May 2005; Guardian, 28 May 2005; Los Angeles Times, 29 May 2005.

…

Simultaneously, bicycle commuters have been penalized by new license fees, restrictions on using arterial roads, and the end of the bicycle subsidies formerly paid by work units.33 The result of this collision between urban poverty and traffic congestion is sheer carnage. More than one million people — two-thirds of them pedestrians, cyclists, and passengers — are killed in road accidents in the Third World each year. " People who will never own a car in their life," reports a World Health Organization researcher, "are at the greatest risk."34 Minibuses and jitneys, often unlicensed and poorly maintained, are particularly dangerous: in Lagos, for example, the buses are known locally as danfos and molues, "flying coffins" and "moving morgues."35 Nor does the snail's pace of traffic in most poor cities reduce its lethality. Although cars and buses crawl through Cairo at average speeds of less than 10 kilometers per hour, the Egyptian capital still manages an accident rate of 8 deaths and 60 injuries per 1000 32 Sperling and Clausen, "The Developing World's Motorization Challenge," p. 3. 33 Example of Beijing in Sit, Beijing, pp. 288—89. 34 Study by WHO-funded Road Traffic Injuries Research Network, quoted in Detroit Free Press, 24 September 2002. 35 Vinand Nantulya and Michael Reich, "The Neglected Epidemic: Road Traffic Injuries in Developing Countries," British Journal of Medicine 324 (11 May 2002), pp. 1139—41.

…

The researchers noted: "In general, informal petty business is the employment of last resort for the most economically vulnerable city residents."29 Moreover, informal and small-scale formal enterprises ceaselessly war with one another for economic space: street vendors versus small shopkeepers, jitneys versus public transport, and so on.30 As Bryan Roberts says about Latin America at the beginning of the twenty-first century, "the 'informal sector' grows, but incomes drop within it."31 Competition in urban informal sectors has become so intense that it recalls Darwin's famous analogy about ecological struggle in tropical nature: "Ten thousand sharp wedges [i.e., urban survival strategies] packed close together and driven inwards by incessant blows, sometimes one wedge being struck, and then another with greater force."

City on the Verge

by

Mark Pendergrast

Published 5 May 2017

Trucks were beginning to take more goods to their final destination, albeit inefficiently. “Many products are transferred by vehicles in city streets a half dozen times before they reach the consumer.” 1914 Atlanta street scene 1924 Atlanta street scene Impeded by traffic congestion, streetcar service slowed. Private unlicensed autos called “jitneys” sped in front of streetcars, offering somewhat cheaper rides and greater flexibility. Many people began to consider the streetcars a nuisance, blaming them rather than automobiles for the congestion. In 1923, Atkinson’s transit company presented a “Constructive Plan for Solving Present and Future Transportation Problems of Atlanta” to the mayor, suggesting improvements to the trolley system along with supplementary bus service.

…

The following year, a New York consulting firm headed by John Beeler submitted a scathing report. “The city’s tardiness in evolving a definite city plan, coupled with the rapid and noteworthy growth in all phases of its life, is the underlying cause of the present acute situation.” The Beeler report recommended banning jitneys, building more viaducts over the rail lines, and adding motor coach service (buses) to extend streetcar lines. Some of these suggestions were implemented, though they actually hastened the switch from rail and streetcar to motorized vehicles. “The evermore massive invasion of the city by the automobile actually negated the benefits of many of the Beeler recommendations,” noted historian O.

…

As the economy tanked, in 2010 the Clayton County commissioners abruptly cancelled C-Tran, the public bus service that had provided 2 million rides a year, leaving impoverished residents without a way to get to jobs, schools, or medical services. Some apartment complexes along the former bus lines were half empty. The county supplied many of the janitors, rental car employees, and other low-paid workers at the nearby Atlanta airport, the world’s busiest and the largest employer in Georgia. Private jitney buses, charging relatively high fees, began to ferry Clayton residents to work. According to 2010 census data, the average per capita income of the 267,000 residents of Clayton County was about $19,000, the lowest of any county near Atlanta. Clayton is shaped something like New Hampshire, long from north to south and broader at the top, with Forest Park, Riverdale, Morrow, and Jonesboro the principal cities nearest Atlanta.

Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City

by

Peter D. Norton

Published 15 Jan 2008

“Bulk and distance haulage is exclusively a steam railroad function,” said a truck manufacturer in 1924. “We would much rather have the railroad for a customer than a competitor.”9 The front line of battle was not between road and rail; rather, it divided regulated and unregulated modes. The most regulated vehicle in cities was the streetcar; for a time its greatest rival was the unregulated jitney.10 Their fight was an early sign of growing rivalry between those modes of transportation regulated as public utilities (whether on rails or not) and those not so regulated. Under the stress of increasing traffic congestion, regulated modes tried to expand the sphere of such regulation to other modes, while other modes fought against the application of public utility principles in urban transportation.

…

But with the new pressures, the railways could no longer afford such inefficiencies. Bankruptcies crested in 1919, when 51 street railways were turned over to receivers.5 These stresses cast a shadow of popular suspicion over regulation itself. Street railways took refuge in their franchise protections, bandied them at upstarts such as jitney operators and independent bus companies, and demanded fare increases, while the quality of service declined. State public service commissions generally granted fare increases. Riders smelled a rat. Defenders of state regulation complained of a “public attitude toward utility commissions” that “has been critical rather than constructive, reflecting a feeling of uneasiness and distrust.”

…

Powell, “Function of the Motor Truck in Reducing Cost and Preventing Congestion of Freight in Railroad Terminals,” Annals 116 (Nov. 1924), 87–89; Graham, “Recent Developments in Highway Transport,” 14. See also F. W. Fenn, “Transportation–the Keynote of Prosperity,” American City 23 (Dec. 1920), 598–600). 10. Howard L. Preston, Automobile Age Atlanta: The Making of a Southern Metropolis, 1900–1935 (University of Georgia Press, 1979), 55–63; Ross D. Eckert and George W. Hilton, “The Jitneys,” Journal of Law and Economics 15 (Oct. 1972), 293–325. 11. See esp. Barrett, The Automobile and Urban Transit, esp. 211–212, and Albro Martin, Enterprise Denied: Origins of the Decline of American Railroads, 1897–1917 (Columbia University Press, 1971), and Railroads Triumphant: The Growth, Rejection, and Rebirth of a Vital American Force (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Lonely Planet Jamaica

by

Lonely Planet

Yaaman Adventure ParkPLANTATION ( GOOGLE MAP ; %994-1058; www.yaamanadventure.com; full-day package adult/child US$149/79; hMon-Sat) Formerly the more sedately named Prospect Plantation, this beautiful old hilltop great house and 405-hectare property has rebranded as an active adventure park. Get off-road in the 'wet & dirty' buggy ride. More relaxing are tours through scenic grounds among banana, cassava, cocoa, coconut, coffee, pineapple and pimento by Segway (adult/child US$76/54), horse (US$54/43) or tractor-powered jitney (US$39/22). Bamboo Beach ClubBEACH ( GOOGLE MAP ; J$1000; h9am-5pm) This clean yellow-sand beach is hustler-free and popular with tourists only, due to the high admission rate. Locals still call it by its old name, Reggae Beach. Kayaks are available for rent, and jerk chicken and fish are readily available.

…

Lifeguards assist you with the rope swing above one of the pools and a stone staircase follows the cascades to the main waterfall. There are no lockers, so watch your stuff. The more adventurous can fly, screeching, over the falls along a canopy zip line for US$50/35 per adult/under-12. A tractor-drawn jitney takes all visitors to the cascades, where you’ll find picnic grounds, changing rooms, a tree house and a shallow pool fed with river water. Almost every tour operator in Jamaica (and many hotels) offer trips to YS Falls, but if you want to get here ahead of the crowds, drive yourself (or charter your own taxi) and arrive right when the grounds open.The YS Falls entrance is just north of the junction of the B6 toward Maggotty.

…

The prettiness of the place is all the more remarkable when one considers this was once the scarred remains of a bauxite mine; Patrick Lee helped bring the area back to nature after hiring locals and subsequently boosting the surrounding economy, and for this reason we give some of the wear and tear evident on the grounds a pass. The 169-hectare family nature park is only open by appointment, so call ahead. The owners also operate a tractor-pulled jitney from the old train station in Maggotty. 8Getting There & Away Public transportation vehicles infrequently arrive and depart from opposite Shakespeare Plaza at the north end of Maggotty, connecting to Mandeville (J$240) and Black River (J$210). Middle Quarters This small village on the A2, 13km north of Black River, is a tiny vortex of good eats: it’s renowned for women higglers (street vendors) who stand at the roadside selling delicious (spicy) pepper crayfish – pronounced ‘swimp’ in these parts – cooked at the roadside grills ( GOOGLE MAP ; Hwy A2; bag of shrimp J$500).

We're Going to Need More Wine: Stories That Are Funny, Complicated, and True

by

Gabrielle Union

Published 16 Oct 2017

We were kids with no jobs, so every morning the conversation went like this: “Where are we gonna go today?” “What boy’s house can we walk to?” “Whose parents aren’t home?” “Who has a car?” Just finding somebody with a car was incredibly rare. In Pleasanton, everybody had a car. But in Omaha, people got around through what they called “jitneys”: elderly people that you knew your whole life would say, “Hey, call me if you need me to get to the store. Just give me three dollars.” Teenagers even drank differently in North Omaha. It wasn’t the binge drinking of mixed drinks in plastic cups, like in Pleasanton. If you were kicking back on the stoop you had a forty or a wine cooler.

…

He went to prison. Lucky was killed the following summer, leading everyone to think they were the first one to say, “Guess he wasn’t so lucky.” Another friend got shot and had to wear a colostomy bag for the rest of his life. Kevin joined a gang, then his best friend Dennis died. A girl I knew stabbed a jitney driver rather than pay him five dollars. He lived. He’d known her since she was a baby and was able to tell police exactly where she lived, who her grandfather was, hell, who her great-grandmother was. Another boy that I thought was so cute shot up a Bronco Burgers. The mom of one of our friends decided she had to get her son out of Omaha.

Straphanger

by

Taras Grescoe

Published 8 Sep 2011

Trolleys, it was true, were having trouble operating as automobiles brought them to a near standstill in downtowns across the United States. Pacific Electric, forced to keep its fares at a nickel and maintain service on low-demand lines, saw its business stolen on profitable routes by unregulated “jitneys” and bus companies; the company’s efficiency was further reduced by accidents as reckless drivers crisscrossed the tracks. General Motors and its co-conspirators were not solely responsible for the death of the trolley—but they did manage to deliver the decisive coup de grâce. Streetcars, in other words, didn’t simply fall off the cliff.

…

This, of course, is how public transport worked in New York, Paris, and London in the nineteenth century, with dozens of horsecar and omnibus companies competing for customers—until civic paralysis made the construction of elevateds, metros, and subways inevitable. It is still the way transit functions in many developing-world metropolises. In Manila, for example, colorful jeepneys—a melding of leftover American military Jeeps and jitneys, the unregulated shared taxis that competed with streetcars in the United States at the end of the First World War—dominate public transport. Middle-class Filipinos almost never ride the slow, crowded, and laborintensive jeepneys, which crowd busy avenues but rarely serve the suburbs. Jeepneys and busetas are the libertarian ideal of competition-in-the-market made manifest: public transport is left to the free market, with a minimum of public oversight.

…

Charles believes most of the money goes to feeding TriMet employees’ salaries and fringe benefits. “Transit doesn’t need any more subsidies. We need to cut the subsidies. Transit should be self-supporting. What we need is to deregulate to get rid of this behemoth TriMet, and enable private sector transit with niche markets of legalized jitneys again.” Like most libertarians, Charles believes that if transit can’t pay for itself out of the fare box, it has no business to exist. Privately owned cars should suffice for most people’s transport needs; the rest can rely on dollar vans and share taxis. The flaw in their argument is that the freeways used by private cars aren’t self-supporting, and never have been.

Fodor's Caribbean 2012

by

Fodor's Travel Publications Inc.

Published 30 Aug 2010

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Contents TORTOLA Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Contents Once a sleepy backwater, Tortola is definitely busy these days, particularly when several cruise ships tie up at the Road Town dock. Passengers crowd the streets and shops, and open-air jitneys filled with cruise-ship passengers create bottlenecks on the island’s byways. That said, most folks visit Tortola to relax on its deserted sands or linger over lunch at one of its many delightful restaurants. Beaches are never more than a few miles away, and the steep green hills that form Tortola’s spine are fanned by gentle trade winds.

Suburban Nation

by

Andres Duany

,

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

and

Jeff Speck

Published 14 Sep 2010

Cities that wish to be pedestrian-friendly and fully developed should eliminate this ordinance immediately and provide public parking in carefully located municipal garages and lots. Parking must be considered a part of the public infrastructure, just like streets and sewers. Consideration of the pedestrian scale must also play a role in the provision of transit. Diesel-belching buses are a poor substitute for benevolent streetcars, trolleys, and jitneys. Where laying track is not affordable, the city should consider small electric trams, which have brought new life to cities such as Chattanooga and Santa Barbara. The reader will notice that, in discussing the physical form of the city, we have not once advocated the use of brick sidewalks, festive banners, bandstands, decorative bollards, or grassy berms (“the Five B’s”).

…

As such, each is equipped with nothing but the slowest roads, and contains a local “pocket park”—often no bigger than a single house lot—located within a three-minute walk of every dwelling. The neighborhood thus grants freedom of motion and a certain degree of autonomy even to its youngest citizens. MAKING TRANSIT WORK The neighborhood structure is naturally suited for public transit, be it light rail, trolleys, buses, or jitneys. But there are also three rules that transit must follow in order to appeal to users, regardless of the urban framework: 1. Transit must be frequent and predictable. The challenge is not to prove this obvious principle but to create a transit system in which frequency is economically viable. This objective can be achieved only at certain densities; studies suggest that a minimum of seven units per acre is necessary if transit is to be self-supporting.dd For lower densities, the careful organization of neighborhood centers, to be served by smaller vehicles, can result in a successful network.

City 2.0: The Habitat of the Future and How to Get There

by

Ted Books

Published 20 Feb 2013

Even supposedly egalitarian public transit can be out of reach for the poorest urban dwellers. The vast majority of riders on Delhi’s much-touted new subway, for instance, have incomes more than three times higher than the local median. Each metropolis has its own versions of the same paratransit vehicles: small buses, jitneys, three-wheelers, and motorcycles. There are the “trotros” in Lagos; a relative of the “matatus” in Nairobi; and the megataxis in Manila. The “collectivo” minibus of Latin America is similar to the Philippines’ “jeepney” and Pakistan’s minibus. The auto rickshaw is nearly ubiquitous in South Asia.

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by

Anthony M. Townsend

Published 15 Jun 2020

Still to come are even more ambitious schemes to tap the dark tonnage lying idle in transportation networks. Wasted cargo-carrying capacity abounds in the millions of commercial and government vehicles that sit unused much of the day and night. That’s the insight behind Hannah, a self-driving school bus proposed by Seattle-based design studio Teague. The six-seat student jitneys would be the backbone of an on-demand school-shuttle system in the mornings and afternoons, picking students up as an Uber would. But in between and overnight, they could make deliveries. With nearly a half-million school buses in the US, such a move could double current last-mile delivery capacity.

…

“It’s the most valuable space that a city owns and one of the most underutilized,” says Matthew Roe of NACTO, the city transportation officials’ club. I’m all for cities taking their cut of continuous delivery. But it’s unsettling that the pitch for curb pricing has so rapidly moved past the mobility benefits and straight to the payout. Curb pricing was initially proposed as a tool for ensuring that in the future, buses for poor people and jitneys for senior citizens will have a place to pull over amid the herds of Ubers and Amazons. But when you hear so-called experts talk about curb pricing today it sounds like a flat-out money grab. Cities that cash in on the curb through access fees won’t be flirting with the financialization of mobility so much as giving it a giant bear hug.

Caribbean Islands

by

Lonely Planet

Best Beaches » Cabbage Beach ( Click here ) » Cable Beach ( Click here ) » Pink Sands Beach ( Click here ) » Treasure Cay Beach ( Click here ) » Gold Rock Beach ( Click here ) Best Places to Stay » Graycliff Hotel ( Click here ) » Hope Town Harbour Lodge ( Click here ) » Pink Sands Resort ( Click here ) » Kamalame Cay ( Click here ) Itineraries THREE DAYS Explore Pirates of Nassau, the National Art Gallery and Fort Fincastle in downtown Nassau, grab a jitney for beach-bar cocktails, hike over the Paradise Island bridge to gawk at Atlantis’ shark tanks, and snooze on Cabbage Beach. ONE WEEK Add a Bahamas ferry ride to Harbour Island for pink-sand shores and boutique browsing, or to Andros for mind-blowing dives to the Tongue of the Ocean and hikes to hidden blue holes.

…

Rates are fixed by the government and displayed on the wall; all are for two people; each additional person costs BS$3. One-way rates: Cable Beach BS$18; downtown Nassau and Prince George Wharf BS$27; Paradise Island BS$32. Boat Ferries and water taxis run between Woodes Rogers Walk and the Paradise Island Ferry Terminal for BS$6, round-trip. Bus Nassau and New Providence are well served by minibuses called jitneys, which run from 6am to 8pm, although there are no fixed schedules. No buses run to Paradise Island, only to the connecting bridges (the Paradise Island Exit Bridge and the New Paradise Island Bridge). Buses depart downtown from the corner of Frederick and Bay Sts, the corner of West Bay and Queen, and designated bus stops.

…

Destinations are clearly marked on the buses, which can be waved down. To request a stop, simply ask the driver. Standard bus fare is BS$1 to BS$1.50. There are numerous buses and routes, but no central listing. Check with the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism Welcome Centre ( Click here ) for specifics, look at the destinations marked on the front of the jitney , or try one of these common routes: Buses 10 & 10A Cable Beach, Sandyport Bay and Lyford Cay Buses 1, 7 & 7A Paradise Island bridges Car & Scooter You don’t need a car to explore downtown Nassau or to get to the beaches. If you intend to explore New Providence, it’s worth saving taxi fares to and from Nassau by hiring a car.

The Big Book of Words You Should Know: Over 3,000 Words Every Person Should Be Able to Use (And a Few That You Probably Shouldn't)

by

David Olsen

,

Michelle Bevilacqua

and

Justin Cord Hayes

Published 28 Jan 2009

Anna had so much ham left over from Easter dinner that she decided to try to whip up a JAMBALAYA. jejune (ji-JOON), adjective Dull or lackluster. Jejune can also mean immature or lacking in insight. Ralph’s JEJUNE fantasies of stardom brought only laughs of derision from his friends. jitney (JIT-nee), noun A small car or bus charging a low fare. Grandpa told us stories of how he used to make his living driving a JITNEY around town. jocund (JOK-und), adjective Given to merriment. Someone who possesses a cheery disposition is jocund. Tim’s JOCUND personality made him the life of the party. judicature (JOO-di-kuh-choor), noun The authority of jurisdiction of a court of law.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by

Robert J. Gordon

Published 12 Jan 2016

It took longer for the automobile to replace public transit, but the initial threat of the automobile to the established fixed-rail regime was already widespread by 1910 in the form of the “jitneys,” unlicensed taxicabs which operated in a free-for-all to cruise the routes of the streetcars and pick up passengers, especially those loaded with packages. The streetcar operators were particularly irked to see that the jitneys paid no taxes and faced no regulations.115 The first motor bus arrived on New York’s 5th Avenue in 1905, but the development of the motor bus was surprisingly slow. The initial bus designs were converted trucks, with a center of gravity high off the ground.

…

Details about the construction and design of the Merritt Parkway are provided by Radde (1993). He describes (pp. 6–9) Robert Moses’s parkway systems on Long Island and in Westchester County as precursors of the limited access highways. 113. A detailed U.S. highway map dated October 23, 1940, appears in Kaszynski (2000, p. 133). 114. Greene (2008, p. 174). 115. Details about jitneys come from Miller (1941/1960, p. 150–53). 116. Details about the Fageol motor coach are in Miller (1941/1960, pp. 154–56). 117. In table 5–1, a rail trip in 1940 between Los Angeles and New York took less than half the time, two days and eight hours, plus a layover of up to ten hours in Chicago. 118.

…

See income inequality infant mortality, 50, 61; contaminated milk and, 81; germ theory and, 219; improvements in (1870–1940), 206, 208, 209, 211, 213, 244–45, 322, 463; racial differences in, 484 infectious diseases, 210, 213–15, 218, 462 information technology (IT), 325; from 1870 to 1940, 202–5; in GDP, 441–42; on Internet, 460; news, 433–35; newspapers and magazines for, 174–77; post-World War II, 411; telegraph for transmission of, 178–79; in Third Industrial Revolution, 577, 578 Ingram, Edgar, 167 Ingrassia Paul, 382 injuries: industrial, 270–73; railroad-related, 238 innovation: as cause of Great Leap Forward, 555–62; future of, 567, 589–93; history of, 568–74; since 1970, 7; total factor productivity as measurement of, 2, 16–18, 319, 537 installment loans, 296, 317 insurance, 288, 289; fire and automobile, 307–9, 317; health insurance, 230, 235–36, 487–95; life insurance, 303–7, 317; workers’ compensation, 230, 272–73 Intel (firm), 445, 453 internal combustion engines, 131, 149–50, 374; as General Purpose Technology, 555–56; See also automobiles Internet, 442–43, 453–57, 459–60, 578; digital music on, 436; early history of, 643; e-commerce using, 457–58; smartphones for, 438; as source of news, 434, 435; video streaming on, 436–37 Interstate Commerce Act (1887), 313 Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), 313, 318 Interstate Highway System, 159, 375, 389–93, 407; automotive safety and, 385–86 interurbans, 149 inventions: by decade, 556; forecastable, 593–601; patents for, 312–13, 570–74; sources of, 570 iPhone, 577 iPod (MP3 player), 435–36 iron and steel industries, 267–69; industrial accidents and deaths in, 271 iTunes, 435–36, 579 J. C. Penney (department store), 90, 294 Japan, 562 The Jazz Singer (film), 201, 202 Jefferson, Thomas, 210 Jell-O (firm), 73 jet aircraft, 393, 398–99 JetBlue (firm), 598 jitneys, 160 Jobs, Steve, 452, 567 Johns Hopkins Medical School, 233 Johnson, Lyndon B., 419 joint replacement surgery, 466 Jolson, Al, 201 Jorgenson, Dale, 543, 636 The Jungle (Sinclair), 82, 221–22, 267, 313 Kaiser, Henry, 549 Kansas City (Missouri), 219 Katz, Lawrence, 15, 284, 624–25, 636 KDKA (radio station), 192, 193 Keeler, Theodore, 403 Kellogg, J.

The Crying of Lot 49

by

Thomas Pynchon

Published 1 Jan 1966

Whatever else was being denied them out of hate, indifference to the power of their vote, loopholes, simple ignorance, this withdrawal was their own, un-publicized, private. Since they could not have withdrawn into a vacuum (could they?), there had to exist the separate, silent, unsuspected world. Just before the morning rush hour, she got out of a jitney whose ancient driver ended each day in the red, downtown on Howard Street, began to walk toward the Embarcadero. She knew she looked terrible knuckles black with eye-liner and mascara from where she'd rubbed, mouth tasting of old booze and coffee. Through an open doorway, on the stair leading up into the disinfectant-smelling twilight of a rooming house she saw an old man huddled, shaking with grief she couldn't hear.

American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers

by

Nancy Jo Sales

Published 23 Feb 2016

Dating lots of guys, it won’t make you happy, she said, looking at Sydney with her worried eyes. “Oh, Mommy, can I just go to the party?” Sydney said, repeating how it was at a very nice girl’s house and the parents would be there and they were very rich people, so it was likely to be a nice place and lots of nice kids were going. It was Sydney’s first time on the Hampton Jitney, the bus to Long Island, and all the way she imagined how it would be. There was a boy from another school going, named Tim, who she kind of had her eye on. He seemed nice, he was quiet and calm, and he kind of gave her “the look.” All the way out to the Hamptons Sydney ignored Clara and Stacy, who were drinking vodka from a flask and acting like it was so cool.

…

As if they’d been married for several years and just suddenly saw each other in the kitchen and thought, I have to kiss her, I have to kiss him, this wonderful woman, this man, that I’m married to. It felt so intimate. A little while later, Sydney saw Tim on the porch making out with the rando. His hands all up in her shirt. Sydney went and sat on the beach and looked at the waves. When she was on her way home from the party on the Jitney the next day, she got a text from Tim. “Yo, I’ll get you next time,” it said. Online “Hooking up” wasn’t invented by millennials, or American college kids, or Tinder. It’s been a long, lusty road since the 1848 founding of the Oneida Community, the utopian religious commune in Oneida, New York, which practiced “free love.”

Capitalism 3.0: A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons

by

Peter Barnes

Published 29 Sep 2006

They’d grow more food organically and sell more through farmers’ markets and urban buying clubs, cutting out middlemen and keeping more of their products’ value. For nonperishables, consumers would shop more on the Internet and less at drive-and-haul malls. Thanks to eBay, Craigslist, and similar services, they’d also buy more secondhand goods and dump fewer into landfills. More workers would ride bikes, jitneys, and trains, and work online from home. Cities would favor footpower, suburbs would reorganize around transit hubs, and new 152 | MAKING IT HAPPEN forms of co-housing would spread. All these changes would be profitable and even exciting. And they’d proceed with relative smoothness if we placed the global atmosphere in trust.

Kowloon Tong

by

Paul Theroux

When hard-up people named a figure it was always absurd—sometimes a pittance, more often a fortune. And they were just as silly in talking about houses or cars. "Why you don't have a Mercedes-Benz?" Luz asked him one rainy night—he was giving her a lift—jeering at his aged Rover. Luz was from Manila, city of bangers and jitneys. These people were single-minded and credulous, and you could never please them, and that was why a million was meaningless, just funny money. He suspected that of Mr. Hung, who could not possibly ever have had money. The whole point about the Chinese until just the other day was that every one of them was equally broke and pathetic.

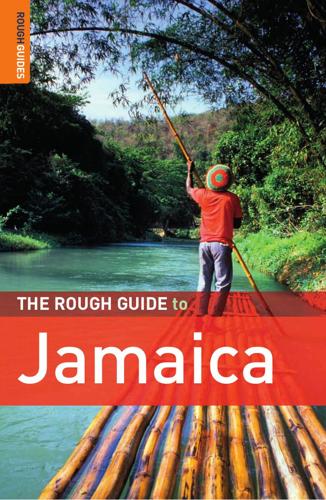

The Rough Guide to Jamaica

by

Thomas, Polly,Henzell, Laura.,Coates, Rob.,Vaitilingam, Adam.

Back on the main road and half a mile into St Mary, the former haunt of planter Harold Mitchell has been reincarnated as Prospect Plantation (daily; T 994 1058, W www .prospectplantationtours.com; 3–5 hours; US$44–90), now owned by Dolphin Cove. The traditional tour is designed to introduce the more sedentary visitor to the delights of tropical farming with an hour-long jitney ride through sugar cane and groves of coconut, pimento, lime, ackee, breadfruit and soursop trees, stopping to spot butterflies, feed ostriches and sample fruits. You’ll feel less like a member of a cattle herd if you indulge in the camel safari, mountain bike or horseback rides through the plantation or down into White River gorge, the site of Jamaica’s first hydroelectric plant – though they’re significantly more expensive.

…

The name is thought to derive from the farm’s original owners in 1684, John Yates and Richard Scott, whose initials were stamped on their cattle and the hogsheads of sugar that they exported. Today the farm covers around 2300 acres and raises pedigree red poll cattle – a Jamaican breed that you’ll see all over the country. The YS Falls, a series of ten greater and lesser waterfalls, are great fun (Tues–Sun 9.30am–3.30pm; closed on public holidays, W www .ysfalls.com; US$15). A jitney pulls you through the farm’s land and alongside the YS River to a grassy area at the base of the falls, where there are changing rooms and toilets. You can climb up the lower falls or take the wooden stairway, which leads to a platform beside the uppermost and most spectacular waterfall. There are lianas and ropes for aspiring Tarzans, and pools for gentle bathing at the foot of each fall as well as a spring water swimming pool on the flat for lounging.

Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking About Public Transit Can Enrich Our Communities and Our Lives

by

Jarrett Walker

Published 22 Dec 2011

TECHNOLOGY: TOOL OR GOAL? When someone asks me what I do, and I say I’m a transit planner, their next question is almost always about technology. They ask my opinion INTRODUCTION | 7 about a rail transit proposal that’s currently in the news, or ask me what I think about light rail, or monorails, or jitneys. They assume, like many journalists, that the choice of technology is the most important transit planning decision. Technology choices do matter, but the fundamental geometry of transit is exactly the same for buses, trains, and ferries. If you jump too quickly to the technology choice question but get the geometry wrong, you’ll end up with a useless service no matter how attractive its technology is.

Give People Money

by

Annie Lowrey

Published 10 Jul 2018

In some ways, Uber has offered the city a salvation, creating thousands of flexible ridesharing gigs and a smallish number of highly compensated positions for scientists and technologists at its local Advanced Technologies Group office. But salvation has seemed chimerical, with those ridesharing jobs paying little and pulling work away from the city’s taxi and jitney drivers and those highly compensated positions at the Advanced Technologies Group dedicated in part to eliminating the need for human drivers entirely. The former problem is the pressing one, the drivers told me. “Their immediate concern is their immediate experience,” said Erin Kramer, the executive director of One Pennsylvania, a local community organizing group, who was sharing burgers and beers with us.

Young Money: Inside the Hidden World of Wall Street's Post-Crash Recruits

by

Kevin Roose

Published 18 Feb 2014

Jeremy had gone in with more than a dozen other first- and second-year Goldman analysts on a house share in Westhampton, a tony beachside enclave roughly two hours from the city. Every Friday, the young Goldmanites and their friends and significant others would pile onto the Long Island Railroad or the Hampton Jitney and head to the beach, where they would swim and drink by day and head to clubs by night, before coming back to sleep on floors, couches, and air mattresses sprinkled throughout the four-bedroom house. Packing dozens of people into a relatively modest house wasn’t the over-the-top experience many older and richer Hamptons summer home owners had, but it kept their costs down to just over $1,500 a person for the whole summer, and it allowed them to invite their friends to “my Hamptons house,” which was half the fun.

After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back

by

Juliet Schor

,

William Attwood-Charles

and

Mehmet Cansoy

Published 15 Mar 2020

In 2010 three Harvard Business School students went ahead with the P2P model anyway and started RelayRides.29 We Are the “Uber of X” Within a few years startups were being founded at a frenzied pace, with many describing themselves as “the Uber of x.”30 Investors poured an astonishing $23 billion into the sector between 2010 and 2017.31 Researchers began predicting that Uberization “might replace the modern corporation.”32 One journalist cataloged 105 American “Uber for x’s” founded between 2009 and 2019.33 Transportation sites offered real-time ridesharing (with drivers who were making trips for their own purposes rather than to earn), jitney services, and apps that promised to treat drivers better than Uber and Lyft. Peer-to-peer rental schemes emerged for boats, airplanes, bicycles, and cars left at airports while their owners were traveling. In lodging, the offerings were less varied, perhaps because Airbnb had hit upon a winning formula.34 Platforms specializing in “idle capacity” grew, offering parking spaces, yards (for gardening), attics, and storage space.

Stealth of Nations

by

Robert Neuwirth

Published 18 Oct 2011

Buses are the other common form of mass transit in Lagos, and, as with okada, this huge enterprise, with tens of thousands of vehicles, is a System D creation. Once upon a time decades ago, this was a public system. The government owned the molue—large buses that fit thirty or forty people—and danfo—smaller jitneys that fit between a dozen and twenty, depending on how the seating is installed. But the authorities walked away from public transportation. In desperation, the bus system was kept alive by the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW)—but in the most haphazard manner you can imagine. The union essentially bought the city’s fleet of seventy-five thousand buses.

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by

Richard Florida

Published 9 May 2016

Connectivity can be accomplished in other, less expensive ways tailored to local conditions. When my Creative Class Group colleagues and I developed the inaugural Philips Livable City Awards, one of our three winners in 2011 was a small shade stand that functions as a shelter from the hot sun or pouring rain. But more than that, it was a way of organizing and structuring stops for the jitneys and simple buses that residents could use to get around in Kampala, Uganda, and other rapidly expanding African cities. I saw a couple of other ingenious solutions for local connectivity during my visit to Medellín. Not long ago, the city was one of the most violent and lawless in the world, overrun by drug kingpin Pablo Escobar and his notorious Medellín Cartel.

Zeitgeist

by

Bruce Sterling

Published 1 Nov 2000

Starlitz lit one of Viktor’s cigarettes, put his hands in his pockets, and began to drift. Midmorning found Starlitz sitting on a bus bench, eating from a large bag of chocolate croissants and sipping a Styrofoam Nescafé. Urban crowds went about their business, men in flat hats and patterned sweaters, women heaving baby carriages along the black-and-white-striped curb. A rust-spotted jitney pulled over. A backpacking American woman climbed out of it. Her skin was the color of a Starbucks frappuccino, and she had black, kinked hair in big clusters of thread-knotted twists. She wore a nylon tropical shirt, knotted at the midriff, and chocolate-chip desert-camo cutoffs, unconvincingly cinched up with a gleaming concho belt.

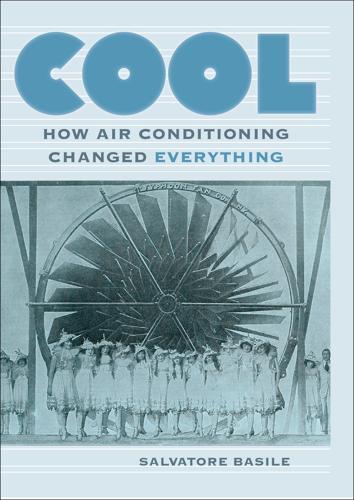

Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything

by

Salvatore Basile

Published 1 Sep 2014

It listed lawmakers’ methods for summer survival: lemonade stirred up by Senate cloakroom attendants, perhaps a refreshing bath (“bathing rooms” had been in the basement since the 1870s, and it wasn’t uncommon for congressional members to disappear in the middle of the day for a quick restorative plunge). Most effective of all was a ride in the twelve-seater jitney provided for travel in the Capitol Subway; the tunnel was far enough underground that it was perpetually cool. As to any talk of refrigeration equipment, the article provided yet another red herring when it mentioned that “an ultra-modern plant” for cooling would be installed “in another year.” When Woodrow Wilson succeeded Taft in 1913, he discovered his predecessor’s cooling system.

Frommer's Caribbean 2010

by

Christina Paulette Colón

,

Alexis Lipsitz Flippin

,

Darwin Porter

,

Danforth Prince

and

John Marino

Published 2 Jan 1989

You can swim in the pool and sample a wide v ariety of br ews and concoctions. The Plantation Tour Eating House offers typical Jamaican dishes for lunch, and ther e’s a souvenir shop with a good selection of ceramics, ar t, straw goods, woodcar vings, rums, liqueurs, and cigars. You can also take a tour ar ound the working plantation in a tractor-drawn jitney 398 to see the tropical fruit trees and coffee plants; the knowledgeable guides will explain the various processes necessary to produce the fine fruits of the island. This is far more interesting than the trip to C roydon Plantation in M ontego Bay, so if y ou’re visiting both places and have time for only one plantation, make it B rimmer Hall.

…

Island Village and Island Village Shopping C enter Island Village, Turtle Beach Rd . No c entral swit chboard—each establishment has its o wn phone . Free admission. Daily 9am–midnight. Golf Course. A visit to this pr operty is an educational, r elaxing, and enjo yable experience. On a leisurely tour by covered jitney through the scenic beauty of P rospect, you’ll readily see why this section of Jamaica is called “the garden parish of the island.” You can view the many tr ees planted b y such visitors as Winston Chur chill, H enry Kissinger, Charlie Chaplin, Pierre Trudeau, and Noël Coward. You’ll learn about and see pimento (allspice), bananas, cassava, sugar cane, coffee, cocoa, coconut, pineapple, and the famous leucaena (“Tree of Life”).

…

You’ll learn about and see pimento (allspice), bananas, cassava, sugar cane, coffee, cocoa, coconut, pineapple, and the famous leucaena (“Tree of Life”). You can even sample some of the ex otic fruit and drinks. Horseback riding ($80 per person for 1 1/2 hr.) is av ailable for adults on thr ee scenic trails at Prospect. Dolphin Cove Tours runs a jitney bus tour to the plantation fr om the center of Ocho Rios Monday to Saturday at 10:30am, 2pm, and 3:30pm. Rte. A3, 5km (3 miles) east of Ocho Rios, in St. Ann. & 876/994-1058. Tours $44 adults, free for children 7 and under. Tours Mon–Sat at 10:30am, 2pm, and 3:30pm. SHOPPING For many, Ocho Rios provides an introduction to Jamaica-style shopping.

The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros Are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy

by

Bruce Katz

and

Jennifer Bradley

Published 10 Jun 2013

Five bright, colorful buildings on four acres house a K–5 charter school; a health clinic; a community development credit union and a free tax-preparation center; a citizenship and outreach center where immigrants can start to navigate the naturalization process; rooms for adult classes in English and in health and wellness; an arts center; a business incubator; an outdoor stage; a splash park; a green space for community gatherings and arts and cultural festivals; and a jitney service, called the “magic bus,” which stops at grocery stores, health clinics, and other service locations 05-2151-2 ch5.indd 90 5/20/13 6:52 PM HOUSTON: EL CIVICS 91 (staffers joke that it is called the magic bus because they count on magic to bring in the money that pays for it). Baker-Ripley opened in 2010, and in its first year and a half, 23,000 people came there to take classes, ask questions, play games, or otherwise participate in the life of the community.10 Although it is located in a neighborhood with a substantially higher crime rate than the city of Houston, high juvenile delinquency rates, and considerable gang activity, Baker-Ripley has no security guards or fences to protect the four-acre campus—there has never been a need for them.11 The facility has no traces of vandalism or graffiti.

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by

James Rickards

Published 15 Nov 2016

An intruder attempting to arrive on foot would have to cross miles of desert, descend canyons around the mesa, climb the mesa walls, and penetrate a secure perimeter. Motion, noise, and infrared sensors and a heavily armed security force ensure that no uninvited visitors make it that far. On April 8, 2009, I was in a U.S. government jitney with physicists and national security experts invited to attend classified briefings on new initiatives at LANL. The laboratory, and the government city around it, were visible in the distance as we approached on the access road from Santa Fe. Desert heat gave it a glimmering look. The city stood out in its isolation.

The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam

by

Max Boot

Published 9 Jan 2018

Lansdale, reading the same newspapers in Manila, summed it up: “As far as the Manila press was concerned, the ‘big white brothers’ are just so many s.o.b.’s.” The newspapers now were full of criticism that, as Lansdale noted, “GI drivers were racing through the streets killing off pedestrians or bumping into jitneys (which were probably built out of stolen Army jeeps).” Another sore point was the location of U.S. military bases—“The Filipinos want military bases in the Philippines, but not near anybody and certainly not near Manila.”52 GIs did not help their own cause with wanton displays of racism against “Flips,” as they often called the locals.

…

”66 In response, all that the modest major could do was shrug his shoulders. In fact, he knew the answer—that he had succeeded in integrating and ingratiating himself with all levels of Philippine society. During the previous three years, he had traveled from the streets of Manila, jammed with pedestrians and jitneys, to the dense jungles and isolated nipa huts of the boondocks. He had met bandits and congressmen, Negrito tribesmen and farmers, soldiers and Huks. He had seen for himself how both the insurgency and the government operated. He had become, in short, one of the leading experts on the Philippines not just in the U.S. armed forces but in the entire U.S. government.

The Devil's Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square

by

James Traub

Published 1 Jan 2004

The decline of Broadway provoked Stanley Walker, hard-boiled city editor, into a mighty blast of dismay. The street, he wrote, “has degenerated into something resembling the main drag of a frontier town. . . . There are chow-meineries, peep shows for men only, flea circuses, lectures on what killed Rudolf Valentino, jitney ballrooms and a farrago of other attractions which would have sickened the heart of the Broadwayite of even ten years ago.” The great old chophouses had given way to penny restaurants, “where a derelict just this side of starvation may get something known as food for as little as one cent.” The very faces on the street had become grotesque: “cauliflower ears, beggars, sleazy crones, skinny girls who would be out of place in even the cheapest dance hall, twisted old men, sleek youths with pale faces, the blind and the maimed.”

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy

by

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Published 2 Oct 2017

We stopped for lunch at Pearl’s Place, a homey southern restaurant on South Michigan Avenue. We ate chicken, and Black broke down the South Side’s place in black American lore with unabashed pride. “We were always entrepreneurial types,” he explained. “We couldn’t yell for taxis. They wouldn’t come into the black community. So we created taxi companies. The concept of the jitney was created in Chicago. You couldn’t afford to die, because white mortuaries wouldn’t bury you. So we did it ourselves. We made places like this—places to eat. A single man could come up from the South and get good home cooking and companionship.” Black’s memories of Chicago strivers draw from a deep well of myth and fact.

Wireless

by

Charles Stross

Published 7 Jul 2009

I suppose I’ll have to pack the bloody pachyderm, won’t I? What a bore. Will he fit in the trunk?” Miss Feng sighed, very quietly. “I believe that may be a remote theoretical possibility. I shall endeavor to find out while Sir is enjoying himself not dying.” “Try beer,” I called as I picked up my surf board and climbed aboard the orbital delivery jitney. “Jeremy loves beer!” Miss Feng bowed as the door closed. I hope she doesn’t give him too much, I thought. Then the gravity squirrelizer chittered to itself angrily, decided it was on the wrong planet, and tried to rectify the situation in its own inimitable way. I lay back and waited for orbit. I wasn’t entirely certain of the wisdom of my proposed course of action—there are few predicaments as grim as facing a mammoth with a hangover across the breakfast table—but Miss Feng seemed like a competent sort, and I supposed I’d just have to trust her judgment.

On the Road

by

Jack Kerouac

Published 1 Jan 1957

The heart cards always surround him—the queen of hearts is never far. See this jack of spades? That’s Dean, he’s always around.” “Well, we’re leaving for New York in an hour.” “Someday Dean’s going to go on one of these trips and never come back.” She let me take a shower and shave, and then I said good-by and took the bags downstairs and hailed a Frisco taxi-jitney, which was an ordinary taxi that ran a regular route and you could hail it from any corner and ride to any corner you want for about fifteen cents, cramped in with other passengers like on a bus, but talking and telling jokes like in a private car. Mission Street that last day in Frisco was a great riot of construction work, children playing, whooping Negroes coming home from work, dust, excitement, the great buzzing and vibrating hum of what is really America’s most excited city—and overhead the pure blue sky and the joy of the foggy sea that always rolls in at night to make everybody hungry for food and further excitement.

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape

by

James Howard Kunstler

Published 31 May 1993

T H E G E O G R A P H Y O F N O W H E R E Hydrogen was a pipe dream. Solar, for now, was a joke. In short, there was no real alternative to gasoline, but a lot of people seemed to be banking on the hope that "they'll come up with something. " In the meantime, the AQMD plan would require employers to arrange for car pooling, or even operate their own jitney fleets to reduce the number of total vehicles on the road. That was the transportation component of the plan. Next there was a whole burdensome set of new restrictions on industrial activities-and in the 1980s Southern California had become America's leading man ufacturing region. Many common industrial solvents were out, because they evaporated easily.

Policing the Open Road

by

Sarah A. Seo

A Michigan judge noted that cars had “a capacity for speed rivaling express trains” and provided “a disguising means of silent approach and swift escape unknown in the history of the world before their advent.” Another commentator described “the average policeman, on foot, horseback or depending upon a jitney … about as powerful an enemy of a man in a high[-]powered car as would [be] Don Quixote grappling with an American tank.” Foot patrolmen, they all argued, were ill-equipped to pursue criminals in this motorized world. Vollmer thus arrived at the conclusion—in fact, the conviction—that officers must be “motor-mounted.”56 Police officer on a bicycle, stopping a car, undated.

Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War

by

Mark Bowden

Published 3 Jan 2002

He could hear waves of gunfire crackling over the city, and heard the fight was at the Bakara Market. At Brown & Root, all Somali employees were sent home. “Something has happened,” Abdi was told. Abdi lived with his family between the market and the K-4 traffic circle, which was just north of the Ranger base. The rickety jitneys, so crammed with passengers that the American soldier called them “Kling-on Cruisers” (a nod to Star Trek), were still running up Via Lenin. The sounds of gunfire increased and the sky was thick with helicopters speeding low over the rooftop, flying great looping orbits over the market area. There were bullets snapping over his head when he got home.

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by

James Rickards

Published 7 Apr 2014

I was assigned to become expert in sharia and assist in the conversion of Citibank’s operations from Western banking to Islamic banking. I arrived in Karachi in February 1982 and went to work. Citibank’s country head, Shaukat Aziz, later prime minister of Pakistan, would occasionally pick me up at my hotel. In monsoon season, we would barrel through flooded Karachi streets choked with ubiquitous decorated buses and three-wheeled jitneys, speeding past vendors spitting bright red betel nuts they chewed for a buzz. As I told these tales to the fund manager, I noticed his face became taut and his stare serious. He motioned me to a corner of the deck away from the other guests. He leaned forward and said sotto voce, “Look, it seems you know a lot about Islamic finance and you know your way around Pakistan.”

Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia

by

Anthony M. Townsend

Published 29 Sep 2013

They exert a powerful gravitational pull on the young and the ambitious, and we are drawn to them by the millions, in search of opportunities to work, live, and socialize with each other. While in the end it took slightly longer than the original forecast, by the spring of 2009, most likely in one of China’s booming coastal cities or the swelling slums of Africa, a young migrant from the hinterlands stepped off a train or a jitney and tipped the balance between town and country forever.2 Cities flourished during the twentieth century, despite humanity’s best efforts to destroy them by aerial bombardment and suburban sprawl. In 1900, just 200 million people lived in cities, about one-eighth of the world’s population at the time.3 Today, just over a century later, 3.5 billion call a city home.

Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America

by

Alec MacGillis

Published 16 Mar 2021

There was a “specialty doughnut” cafe where varieties included pumpkin-spice latte crème brûlée, salted dulce de leche, and caramel apple streusel. This was at the Wharf, the $2.5 billion redevelopment of D.C.’s Southwest waterfront—four hotels, 1,375 luxury apartments, restaurants that didn’t accept cash, and nearly a million square feet of offices—where visitors could arrive by jitney motorboats or yachts, and where a firepit called the Torch sent flames leaping twelve feet in the air. And there was Chapman Stables. This was a large new condominium complex in the Truxton Circle neighborhood, near the intersection of New York Avenue and North Capitol Street. A couple decades ago, this part of town was heavily Black and working class.

A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds

by

Scott Weidensaul

Published 29 Mar 2021

We’d already been driving for hours through Assam, a culturally Indian state that occupies the immense Brahmaputra River valley, framed to the north by the foothills of the Himalayas, whose white peaks occasionally nudged the horizon. Our drivers wove through an endlessly flowing torrent of noise and color, people and vehicles and livestock—cars and mopeds, bikes and motorcycles; cows, goats, dogs, donkeys, and bullock carts; three-wheeled jitneys and traditional rickshaws pulled by wiry men. We passed through throngs of schoolgirls, afoot or on bikes, in brightly pigmented saris or uniform dresses, and schoolboys in crisp matching shirts and ties, color-coded by grade—a phalanx of teenaged girls in turquoise, another batch in lemon-yellow, then mobs of small boys sporting white shirts and maroon ties.

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by

Kurt Andersen

Published 14 Sep 2020

A few years later, one very cold morning just after Thanksgiving, I had another slow-road-to-Damascus moment from whatever I had been (complacent neoliberal?) to whatever I was becoming (appalled social democrat?). I was actually on the road to Eppley Airfield in Omaha after my first visit to my hometown since both my parents had died, sharing a minivan jitney from a hotel with a couple of Central Casting airline pilots—tall, fit white men around my age, one wearing a leather jacket. We chatted. To my surprise, even shock, both of them spent the entire trip sputtering and whining—about being baited and switched when their employee ownership shares of United Airlines had been evaporated by its recent bankruptcy, about the default of their pension plan, about their CEO’s recent 40 percent pay raise, about the company to which they’d devoted their entire careers but no longer trusted at all.

Bleeding Edge: A Novel

by

Thomas Pynchon

Published 16 Sep 2013

One thing to build a house with its foundation in the sand, right, somethin else to pay for it with money not everybody believes is real.” “I Ching talk.” “She noticed.” The semimischievous look again. Uh, huh, “A boat, how about a boat, they own a boat?” “Lease one maybe.” “Oceangoing?” “What am I, Moby Dick? You’re that curious, go out there and see.” “Yeah, right, who springs for the jitney, where’s the per diem, see what I’m saying.” “What. You doin this on spec?” “So far it’s a buck and a half for the subway down here, that I can probably absorb. Beyond that . . .” “Shouldn’t be a problem.” Picking up the phone, “Yes Lupita mi amor, could you cut us a check, please, for . . . uh,” raising his eyebrows at Maxine, who shrugs and holds up five fingers, “five thousand U.S., payable to—” “Hundred,” sighs Maxine, “Five hundred, jeez all right I’m impressed, but it’s only enough so I can start a ticket.

The Year's Best Science Fiction: Twenty-Sixth Annual Collection

by

Gardner Dozois

Published 23 Jun 2009

Quivera laughed harshly (I’d already started de-cushioning his emotions, to ease the shock of my removal) and shook his head. “Put it on my tab, girls,” he said, and climbed into the lander. Hours later he was in home orbit. And once there? I’ll tell you all I know. He was taken out of the lander and put onto a jitney. The jitney brought him to a transfer point where a grapple snagged him and flung him to the Europan receiving port. There, after the usual flawless catch, he was escorted through an airlock and into a locker room. He hung up his suit, uplinked all my impersonal memories to a data-broker, and left me there.

Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas

by

Natasha Dow Schüll

Published 15 Jan 2012

The anthropologist Philippe Bourgois similarly describes how methadone patients “mix” the drug with a range of others, including “cocaine, wine, prescription pills, and even heroin” (2000, 170): “by strategically varying, supplementing, or destabilizing the effects of their dose with poly-drug consumption, methadone addicts can augment the otherwise marginal or only ambiguously pleasurable effects of methadone” (ibid., 180; see also Lovell 2006, 153). 23. Derrida 1981, 100. 24. See Rivlin 2004, 45. Given that seniors comprise 20 percent of the Las Vegas area population, many locals-oriented casinos find it in their interest to operate jitneys that shuttle back and forth to assisted living centers; one property transports 8,000 to 10,000 seniors per month. “We’re happy to take the people that are handicapped in any way, oxygen tanks, walkers. We do a lot of that. We have a lot of wheelchairs,” said a casino shuttle driver for Arizona Charlie’s (quoted in Rivera 2000). 25.

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by

Tim O'Reilly

Published 9 Oct 2017

Instead, a swarm of drivers are summoned and managed by algorithms that match drivers and passengers in a real-time online marketplace, with surge pricing to bring more drivers into the market when the algorithm determines that there are not enough of them to meet demand. There are many historical examples of peer-to-peer public transportation. Zimride, Logan Green and John Zimmer’s predecessor to Lyft, was inspired by the informal jitney systems they observed in Zimbabwe. But using the smartphone to create a two-sided, real-time market in physical space was something profoundly new. After initial skepticism, Uber copied the peer-to-peer model a year later. Driven by an aggressive CEO, a stronger technical focus on logistics and marketplace incentives, a take-no-prisoners corporate culture, and huge amounts of capital, it has spent billions to outpace its rivals.

Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas

by

Natasha Dow Schüll

Published 19 Aug 2012

The anthropologist Philippe Bourgois similarly describes how methadone patients “mix” the drug with a range of others, including “cocaine, wine, prescription pills, and even heroin” (2000, 170): “by strategically varying, supplementing, or destabilizing the effects of their dose with poly-drug consumption, methadone addicts can augment the otherwise marginal or only ambiguously pleasurable effects of methadone” (ibid., 180; see also Lovell 2006, 153). 23. Derrida 1981, 100. 24. See Rivlin 2004, 45. Given that seniors comprise 20 percent of the Las Vegas area population, many locals-oriented casinos find it in their interest to operate jitneys that shuttle back and forth to assisted living centers; one property transports 8,000 to 10,000 seniors per month. “We’re happy to take the people that are handicapped in any way, oxygen tanks, walkers. We do a lot of that. We have a lot of wheelchairs,” said a casino shuttle driver for Arizona Charlie’s (quoted in Rivera 2000). 25.

In Pursuit of Privilege: A History of New York City's Upper Class and the Making of a Metropolis

by

Clifton Hood

Published 1 Nov 2016