joint-stock company

description: business entity which is owned by shareholders

245 results

The end of history and the last man

by Francis Fukuyama · 28 Feb 2006 · 446pp · 578 words

children. But families don’t really work if they are based on liberal principles, that is, if their members regard them as they would a joint stock company, formed for their utility rather than being based on ties of duty and love. Raising children or making a marriage work through a lifetime requires

Self-Reliance and Other Essays

by Ralph Waldo Emerson · 12 Oct 1993 · 62pp · 13,939 words

’s a hard thing to do, but it’s worth it every time. I never lose when I trust myself. Ji Lee ● ● ● Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The

Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order

by Noam Chomsky · 6 Sep 2011

A History of Zionism

by Walter Laqueur · 1 Jan 1972 · 965pp · 267,053 words

carry them out, wind up the affairs of the emigrants, and organise trade and commerce in the new country. The Jewish Company would be a joint stock company, framed according to English law, with its principal centre in London and a capital of approximately £50 million. At the very beginning of his book

Virus of the Mind

by Richard Brodie · 4 Jun 2009 · 289pp · 22,394 words

146 C hapter nine C ultur al Viruses “Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The

God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 31 Mar 2009 · 518pp · 143,914 words

be because we have turned them against God in much the same way as we previously poisoned their minds against American conservatives, management gurus and joint-stock companies. Having studied the tricks of the pulpit, we have repeatedly promised Fev and Amelia that salvation is just around the corner, that the book will

Are Trams Socialist?: Why Britain Has No Transport Policy

by Christian Wolmar · 19 May 2016 · 79pp · 24,875 words

that was greatly accelerated by the advent of the railways. The key financial mechanism that enabled the canals to be financed and built was the joint stock company. The concept had been around for centuries (there are competing claims in several European countries to being the first such venture) but the canal age

The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being

by William Davies · 11 May 2015 · 317pp · 87,566 words

. Anticipating Thatcherism and workfare nearly two centuries beforehand, one of Bentham’s policy recommendations was for the state to establish a National Charity Company (a joint stock company, modelled on the East India Company), which would alleviate poverty by employing hundreds of thousands of people in privately managed ‘industry houses’.21 His proposal

A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn - the Last Great Battle of the American West

by James Donovan · 24 Mar 2008

colonies.) Their generosity was not repaid in kind. The settlers were soon told by their superiors — who were, after all, directors of a for-profit joint-stock company — to do whatever it took to acquire all the land they could. Indian tempers grew short after a series of humiliations and attacks (no doubt

Inheritance

by Leo Hollis · 334pp · 103,106 words

Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape Our World

by Gaia Vince · 22 Aug 2022 · 302pp · 92,206 words

The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters

by Rose George · 13 Oct 2008 · 346pp · 101,255 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

The Basque History of the World

by Mark Kurlansky · 4 Jul 2010

More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources – and What Happens Next

by Andrew McAfee · 30 Sep 2019 · 372pp · 94,153 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

Extreme Economies: Survival, Failure, Future – Lessons From the World’s Limits

by Richard Davies · 4 Sep 2019 · 412pp · 128,042 words

Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton · 3 Feb 2002 · 353pp · 148,895 words

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy J. Siegel · 18 Dec 2007

How to Own the World: A Plain English Guide to Thinking Globally and Investing Wisely

by Andrew Craig · 6 Sep 2015 · 305pp · 98,072 words

The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Sep 2019

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by Harsha Walia · 9 Feb 2021

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

The Big Oyster

by Mark Kurlansky · 20 Dec 2006

American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History

by Casey Michel · 23 Nov 2021 · 466pp · 116,165 words

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

Investing Amid Low Expected Returns: Making the Most When Markets Offer the Least

by Antti Ilmanen · 24 Feb 2022

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

The Cable

by Gillian Cookson · 19 Sep 2012 · 136pp · 42,864 words

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It

by Arthur Herman · 27 Nov 2001 · 510pp · 163,449 words

The Social Life of Money

by Nigel Dodd · 14 May 2014 · 700pp · 201,953 words

A Voyage Long and Strange: On the Trail of Vikings, Conquistadors, Lost Colonists, and Other Adventurers in Early America

by Tony Horwitz · 1 Jan 2008

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

The New Rules of War: Victory in the Age of Durable Disorder

by Sean McFate · 22 Jan 2019 · 330pp · 83,319 words

CultureShock! Egypt: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette (4th Edition)

by Susan L. Wilson · 20 Dec 2011

A History of the World in 6 Glasses

by Tom Standage · 1 Jan 2005 · 231pp · 72,656 words

I Never Knew That About London

by Christopher Winn · 3 Oct 2007 · 395pp · 94,764 words

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

The Nature of Technology

by W. Brian Arthur · 6 Aug 2009 · 297pp · 77,362 words

Let them eat junk: how capitalism creates hunger and obesity

by Robert Albritton · 31 Mar 2009 · 273pp · 93,419 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

The Right to Earn a Living: Economic Freedom and the Law

by Timothy Sandefur · 16 Aug 2010 · 399pp · 155,913 words

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

by Steven Johnson · 15 Nov 2016 · 322pp · 88,197 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

The Ages of Globalization

by Jeffrey D. Sachs · 2 Jun 2020

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2020 · 505pp · 138,917 words

How the World Works

by Noam Chomsky, Arthur Naiman and David Barsamian · 13 Sep 2011 · 489pp · 111,305 words

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by Jackson Lears

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by John Darwin · 5 Feb 2008 · 650pp · 203,191 words

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by John Lanchester · 5 Oct 2014 · 261pp · 86,905 words

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by Charles Handy · 12 Mar 2015 · 164pp · 57,068 words

Rigged Money: Beating Wall Street at Its Own Game

by Lee Munson · 6 Dec 2011 · 236pp · 77,735 words

Branded Beauty

by Mark Tungate · 11 Feb 2012 · 290pp · 87,084 words

From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

by Pankaj Mishra · 3 Sep 2012

Empires of the Weak: The Real Story of European Expansion and the Creation of the New World Order

by Jason Sharman · 5 Feb 2019 · 265pp · 71,143 words

About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks

by David Rooney · 16 Aug 2021 · 306pp · 84,649 words

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by Jeremy Paxman · 6 Oct 2011 · 427pp · 124,692 words

Mongolia - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture

by Alan Sanders · 1 Feb 2016 · 122pp · 37,785 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 14 Sep 2017 · 520pp · 153,517 words

The Emperor's New Road: How China's New Silk Road Is Remaking the World

by Jonathan Hillman · 28 Sep 2020 · 388pp · 99,023 words

Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously About the Planet

by Roger Scruton · 30 Apr 2014 · 426pp · 118,913 words

Reinventing Capitalism in the Age of Big Data

by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Thomas Ramge · 27 Feb 2018 · 267pp · 72,552 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded

by Simon Winchester · 1 Jan 2003 · 582pp · 136,780 words

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by Matt Ridley · 395pp · 116,675 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take It Back

by Oliver Bullough · 5 Sep 2018 · 364pp · 112,681 words

Toward Rational Exuberance: The Evolution of the Modern Stock Market

by B. Mark Smith · 1 Jan 2001 · 403pp · 119,206 words

The Tyranny of Metrics

by Jerry Z. Muller · 23 Jan 2018 · 204pp · 53,261 words

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy Siegel · 7 Jan 2014 · 517pp · 139,477 words

Money: 5,000 Years of Debt and Power

by Michel Aglietta · 23 Oct 2018 · 665pp · 146,542 words

Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society

by Nicholas A. Christakis · 26 Mar 2019

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson · 23 Sep 2019 · 809pp · 237,921 words

The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community

by David C. Korten · 1 Jan 2001

The Transhumanist Reader

by Max More and Natasha Vita-More · 4 Mar 2013 · 798pp · 240,182 words

The Gun

by C. J. Chivers · 12 Oct 2010 · 845pp · 197,050 words

The Meritocracy Myth

by Stephen J. McNamee · 17 Jul 2013 · 440pp · 108,137 words

Empire of Cotton: A Global History

by Sven Beckert · 2 Dec 2014 · 1,000pp · 247,974 words

World Economy Since the Wars: A Personal View

by John Kenneth Galbraith · 14 May 1994 · 293pp · 91,412 words

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by Adam Greenfield · 29 May 2017 · 410pp · 119,823 words

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

by Joshua B. Freeman · 27 Feb 2018 · 538pp · 145,243 words

Capital Without Borders

by Brooke Harrington · 11 Sep 2016 · 358pp · 104,664 words

A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories)

by Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf · 27 Sep 2006

Railways & the Raj: How the Age of Steam Transformed India

by Christian Wolmar · 3 Oct 2018 · 375pp · 109,675 words

A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century

by Witold Rybczynski · 1 Jan 1999

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India

by Shashi Tharoor · 1 Feb 2018 · 370pp · 111,129 words

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

by Niall Ferguson · 1 Jan 2002 · 469pp · 146,487 words

The Money Machine: How the City Works

by Philip Coggan · 1 Jul 2009 · 253pp · 79,214 words

Money: The Unauthorized Biography

by Felix Martin · 5 Jun 2013 · 357pp · 110,017 words

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by Branko Milanovic · 9 Oct 2023

Who Owns This Sentence?: A History of Copyrights and Wrongs

by David Bellos and Alexandre Montagu · 23 Jan 2024 · 305pp · 101,093 words

Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World's Tallest Skyscrapers

by Jason M. Barr · 13 May 2024 · 292pp · 107,998 words

Energy: A Human History

by Richard Rhodes · 28 May 2018 · 653pp · 155,847 words

After the New Economy: The Binge . . . And the Hangover That Won't Go Away

by Doug Henwood · 9 May 2005 · 306pp · 78,893 words

Rummage: A History of the Things We Have Reused, Recycled and Refused To Let Go

by Emily Cockayne · 15 Aug 2020

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 23 Dec 2010 · 356pp · 103,944 words

Alistair Cooke's America

by Alistair Cooke · 1 Oct 2008 · 369pp · 121,161 words

Stealth of Nations

by Robert Neuwirth · 18 Oct 2011 · 340pp · 91,387 words

Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations

by Simon Jenkins · 28 Jul 2017 · 253pp · 69,529 words

Life Inc.: How the World Became a Corporation and How to Take It Back

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Jun 2009 · 422pp · 131,666 words

Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity From Politicians

by Joe Quirk and Patri Friedman · 21 Mar 2017 · 441pp · 113,244 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

The Great Crash 1929

by John Kenneth Galbraith · 15 Dec 2009 · 319pp · 64,307 words

Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by Christian Wolmar · 1 Mar 2010 · 424pp · 140,262 words

Why the Dutch Are Different: A Journey Into the Hidden Heart of the Netherlands: From Amsterdam to Zwarte Piet, the Acclaimed Guide to Travel in Holland

by Ben Coates · 23 Sep 2015 · 300pp · 99,410 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Does Capitalism Have a Future?

by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, Craig Calhoun, Stephen Hoye and Audible Studios · 15 Nov 2013 · 238pp · 73,121 words

Night Trains: The Rise and Fall of the Sleeper

by Andrew Martin · 9 Feb 2017 · 238pp · 76,544 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Water: A Biography

by Giulio Boccaletti · 13 Sep 2021 · 485pp · 133,655 words

Money: Vintage Minis

by Yuval Noah Harari · 5 Apr 2018 · 97pp · 31,550 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

Quicksilver

by Neal Stephenson · 9 Sep 2004 · 1,178pp · 388,227 words

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations

by Jacob Soll · 28 Apr 2014 · 382pp · 105,166 words

The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession

by Peter L. Bernstein · 1 Jan 2000 · 497pp · 153,755 words

When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Rise of the Middle Kingdom

by Martin Jacques · 12 Nov 2009 · 859pp · 204,092 words

The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 1 Jan 2010 · 369pp · 94,588 words

Imagining India

by Nandan Nilekani · 25 Nov 2008 · 777pp · 186,993 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by Nathan Schneider · 10 Sep 2018 · 326pp · 91,559 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

The Rough Guide to Toronto

by Helen Lovekin and Phil Lee · 29 Apr 2006 · 257pp · 56,811 words

Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol

by Iain Gately · 30 Jun 2008 · 686pp · 201,972 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by Philip Coggan · 6 Feb 2020 · 524pp · 155,947 words

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

by Yuval Noah Harari · 1 Jan 2011 · 447pp · 141,811 words

Kicking Awaythe Ladder

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Sep 2000 · 192pp

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by Matthew C. Klein · 18 May 2020 · 339pp · 95,270 words

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

by David Abulafia · 2 Oct 2019 · 1,993pp · 478,072 words

Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires and the Conflict That Made the Modern World

by Andrew Lambert · 1 Oct 2018 · 618pp · 160,006 words

The Enablers: How the West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption - Endangering Our Democracy

by Frank Vogl · 14 Jul 2021 · 265pp · 80,510 words

On Grand Strategy

by John Lewis Gaddis · 3 Apr 2018 · 461pp · 109,656 words

The Trains Now Departed: Sixteen Excursions Into the Lost Delights of Britain's Railways

by Michael Williams · 6 May 2015 · 332pp · 102,372 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

by Jeff Gramm · 23 Feb 2016 · 384pp · 103,658 words

Flight of the WASP

by Michael Gross · 562pp · 177,195 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution

by Charles R. Morris · 1 Jan 2012 · 456pp · 123,534 words

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by Chrystia Freeland · 11 Oct 2012 · 481pp · 120,693 words

China's Superbank

by Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe · 26 Sep 2012

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Divided Nation: A History of Germany, 1918-1990

by Mary Fulbrook · 14 Oct 1991 · 934pp · 135,736 words

Making It Happen: Fred Goodwin, RBS and the Men Who Blew Up the British Economy

by Iain Martin · 11 Sep 2013 · 387pp · 119,244 words

McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld

by Misha Glenny · 7 Apr 2008 · 487pp · 147,891 words

The system of the world

by Neal Stephenson · 21 Sep 2004 · 1,199pp · 384,780 words

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems

by Didier Sornette · 18 Nov 2002 · 442pp · 39,064 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

by Nancy Isenberg · 20 Jun 2016 · 709pp · 191,147 words

The Invisible Web: Uncovering Information Sources Search Engines Can't See

by Gary Price, Chris Sherman and Danny Sullivan · 2 Jan 2003 · 481pp · 121,669 words

To the Ends of the Earth: Scotland's Global Diaspora, 1750-2010

by T M Devine · 25 Aug 2011

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry

by Peter Warren Singer · 1 Jan 2003 · 482pp · 161,169 words

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean

by David Abulafia · 4 May 2011 · 1,002pp · 276,865 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

Philanthrocapitalism

by Matthew Bishop, Michael Green and Bill Clinton · 29 Sep 2008 · 401pp · 115,959 words

The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power

by Joel Bakan · 1 Jan 2003

Trust: The Social Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 1995 · 585pp · 165,304 words

New World, Inc.

by John Butman · 20 Mar 2018 · 490pp · 146,259 words

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by Kwasi Kwarteng · 12 May 2014 · 632pp · 159,454 words

Fire and Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain

by Christian Wolmar · 1 Mar 2009 · 493pp · 145,326 words

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by Jane Gleeson-White · 14 May 2011 · 274pp · 66,721 words

The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815-1914

by Richard J. Evans · 31 Aug 2016 · 976pp · 329,519 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and How They Broke Capitalism

by Richard Brooks · 23 Apr 2018 · 398pp · 105,917 words

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber · 1 Jan 2010 · 725pp · 221,514 words

A Pipeline Runs Through It: The Story of Oil From Ancient Times to the First World War

by Keith Fisher · 3 Aug 2022

Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity

by Yoni Appelbaum · 17 Feb 2025 · 412pp · 115,534 words

On the Wrong Line: How Ideology and Incompetence Wrecked Britain's Railways

by Christian Wolmar · 29 May 2005

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds - the Original Classic Edition

by Charles MacKay · 14 Jun 2012 · 343pp · 41,228 words

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor

by David S. Landes · 14 Sep 1999 · 1,060pp · 265,296 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 27 Nov 2012 · 651pp · 180,162 words

Commuter City: How the Railways Shaped London

by David Wragg · 14 Apr 2010 · 369pp · 120,636 words

Running Money

by Andy Kessler · 4 Jun 2007 · 323pp · 92,135 words

The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, a Cunning Revenge, and a Small History of the Big Con

by Amy Reading · 6 Mar 2012 · 349pp · 112,333 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy

by David Hoffman · 1 Jan 2009 · 719pp · 209,224 words

Dr. Johnson's London: Coffee-Houses and Climbing Boys, Medicine, Toothpaste and Gin, Poverty and Press-Gangs, Freakshows and Female Education

by Liza Picard · 1 Jan 2000 · 505pp · 137,572 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion

by Gareth Stedman Jones · 24 Aug 2016 · 964pp · 296,182 words

Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa

by Martin Meredith · 1 Jan 2007 · 649pp · 181,179 words

Empire of Guns

by Priya Satia · 10 Apr 2018 · 927pp · 216,549 words

The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin

by H. W. Brands · 1 Jan 2000 · 961pp · 302,613 words

A History of Future Cities

by Daniel Brook · 18 Feb 2013 · 489pp · 132,734 words

Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making

by David Rothkopf · 18 Mar 2008 · 535pp · 158,863 words

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

How We Got Here: A Slightly Irreverent History of Technology and Markets

by Andy Kessler · 13 Jun 2005 · 218pp · 63,471 words

An Empire of Wealth: Rise of American Economy Power 1607-2000

by John Steele Gordon · 12 Oct 2009 · 519pp · 148,131 words

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by Jan Lucassen · 26 Jul 2021 · 869pp · 239,167 words

The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

by Jonathan Kaufman · 14 Sep 2020 · 415pp · 103,801 words

City: Urbanism and Its End

by Douglas W. Rae · 15 Jan 2003 · 537pp · 200,923 words

Layered Money: From Gold and Dollars to Bitcoin and Central Bank Digital Currencies

by Nik Bhatia · 18 Jan 2021

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000

by Paul Kennedy · 15 Jan 1989 · 1,477pp · 311,310 words

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States

by James C. Scott · 21 Aug 2017 · 349pp · 86,224 words

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by Phil Thornton · 7 May 2014

The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time

by Karl Polanyi · 27 Mar 2001 · 495pp · 138,188 words

The Enlightened Capitalists

by James O'Toole · 29 Dec 2018 · 716pp · 192,143 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

For Profit: A History of Corporations

by William Magnuson · 8 Nov 2022 · 356pp · 116,083 words

The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

by William Dalrymple · 9 Sep 2019 · 812pp · 205,147 words

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

by Daniel Yergin · 23 Dec 2008 · 1,445pp · 469,426 words

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by Kevin Mellyn · 30 Sep 2009 · 225pp · 11,355 words

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

Money for Nothing

by Thomas Levenson · 18 Aug 2020 · 495pp · 136,714 words

The Great Race: The Global Quest for the Car of the Future

by Levi Tillemann · 20 Jan 2015 · 431pp · 107,868 words

Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

by William Quinn and John D. Turner · 5 Aug 2020 · 297pp · 108,353 words

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

Europe: A History

by Norman Davies · 1 Jan 1996

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages

by Carlota Pérez · 1 Jan 2002

The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times

by Giovanni Arrighi · 15 Mar 2010 · 7,371pp · 186,208 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

The First Tycoon

by T.J. Stiles · 14 Aug 2009

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

The World's First Railway System: Enterprise, Competition, and Regulation on the Railway Network in Victorian Britain

by Mark Casson · 14 Jul 2009 · 556pp · 46,885 words

Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice

by Pierre Vernimmen, Pascal Quiry, Maurizio Dallocchio, Yann le Fur and Antonio Salvi · 16 Oct 2017 · 1,544pp · 391,691 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

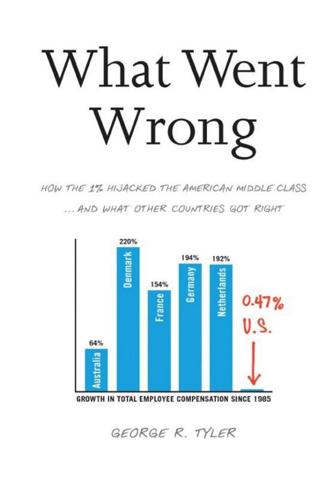

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices

by Robert McNally · 17 Jan 2017 · 436pp · 114,278 words

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

by Adam Winkler · 27 Feb 2018 · 581pp · 162,518 words

From Peoples into Nations

by John Connelly · 11 Nov 2019

The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous

by Joseph Henrich · 7 Sep 2020 · 796pp · 223,275 words

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by Harold James · 15 Jan 2023 · 469pp · 137,880 words

The Life and Death of Ancient Cities: A Natural History

by Greg Woolf · 14 May 2020

The Railways: Nation, Network and People

by Simon Bradley · 23 Sep 2015 · 916pp · 248,265 words

The Communist Manifesto

by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels · 1 Aug 2002 · 51pp · 14,616 words

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by Costas Lapavitsas · 14 Aug 2013 · 554pp · 158,687 words