Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time

by

James Suzman

Published 2 Sep 2020

This was roughly in line with the average annual numbers for the preceding decade. But Japan’s Ministry of Labour will only ever declare a death by karoshi or karo jisatsu under exceptional circumstances, and when it can be proved beyond doubt that the worker has dramatically exceeded reasonable limits for overtime, and that there were no other significant contributing factors (like severe hypertension). As a result, some, like Hiroshi Kawahito, the secretary general of Japan’s National Defence Counsel for Victims of Karoshi – one of a host of anti-karoshi organisations in Japan – insists that the government is reluctant to embrace the true scale of the problem.

…

This was roughly in line with the average annual numbers for the preceding decade. But Japan’s Ministry of Labour will only ever declare a death by karoshi or karo jisatsu under exceptional circumstances, and when it can be proved beyond doubt that the worker has dramatically exceeded reasonable limits for overtime, and that there were no other significant contributing factors (like severe hypertension). As a result, some, like Hiroshi Kawahito, the secretary general of Japan’s National Defence Counsel for Victims of Karoshi – one of a host of anti-karoshi organisations in Japan – insists that the government is reluctant to embrace the true scale of the problem.

…

The Japanese Ministry of Labour officially recognises two categories of death as a direct consequence of overworking. Karoshi describes such a death as a result of cardiac illness attributable to exhaustion, lack of sleep, poor nutrition and lack of exercise, as in Sado’s case. Karo jisatsu describes when an employee takes their own life as a result of the mental stresses arising from overworking. At the end of the year, the Ministry of Labour certified that 190 deaths occurred over the course of 2013 as a result of either karoshi or karo jisatsu, with the former outnumbering the latter two to one. This was roughly in line with the average annual numbers for the preceding decade.

The Naked Presenter: Delivering Powerful Presentations With or Without Slides

by

Garr Reynolds

Published 29 Jan 2010

Three days later, when I asked other students to recall the most salient points of the presentation, what they remembered most vividly was not the labor laws, the principles, and changes in the labor market in Japan. Rather, they remembered the topic of karoshi (literally, “death by overwork”) and the issue of suicides in Japan—topics that were quite minor points in the hour-long presentation. About five minutes of the hour-long presentation was spent on karoshi, but that’s what the audience remembered most. It’s easy to understand why. The issue of death-from-overwork and the relatively high number of suicides are extremely emotional topics that are not often discussed. The presenters cited actual cases and told stories of people who died as a result of karoshi. The stories and the emotional connections they triggered—surprise, sympathy, and empathy—with the audience caused these relatively small points to be remembered most in people’s minds.

…

eBook <WoweBook.Com> making call for action, 172 making sticky, 163–166 on powerful note, 167–169, 172, 181 cognitive overload, avoiding, 37 Collins, Phil, 115 Comedian, 136 comedians, stand-up, 136 communication enhancing, 5 face-to-face, 17–18 removing barriers to, 16 communication experts, 7 computers getting away from, 32 using in presentations, 117 conclusion, beginning with, 167 confidence gaining, 88– 91 necessity of, 125 conflict, including in stories, 44 Confucius, 144 Connection, role in three Cs, 193 contrasts, compelling nature of, 44–45 Contribution, role in three Cs, 193 conversation versus performance, 11–12 conversational language, 147 core points identifying, 50 summarizing in ending, 168 Craft, Chris, 36– 37 The Craft of Scientific Presentations, 40 critical incidents, using, 158 Cs of presenting with impact, 193– 195, 197 D “Deadliest Catch,” 79 death by overwork (karoshi), 47 Decker, Bert, 7, 80–81 deep or wide, 40 defensiveness, avoiding, 177 deGrasse Tyson, Neil, 16, 145 demos, performing, 117–118 depth vs. scope (illustration), 41 design thinking, 24 differences, compelling nature of, 44–45 discussion groups, using for participation, 157 distractions, removing, 49 dojo, lessons from, 190–191 Duarte, Nancy, 7, 34, 164 E Earth Wind & Fire, 103 eat only until 80 percent full (Hara Hachi Bu), 22, 143 ECS (emotionally competent stimulus), 138 education as entertainment, 129– 130 self-, 192 Eisler, Barry, 91 emotional contagion, power of, 109– 110 emotionally competent stimulus (ECS), 138 emotions, 131.

…

See also visuals imagination, stimulating, 158 “impatient optimists,” 188 improvement, 188 improvisation, leaving room for, 121 information determining amount of, 40 sharing via stories, 47 interested vs. interesting, 105 international audience, speaking to, 170–171 interruptions, avoiding during preparation, 30–31 interviews for jobs, expressing true self in, 77–79 J Japanese bath (ofuro), 5, 20–23 Japanese forest, seven lessons from, 70–73 Japanese hot springs (onsen), 5– 6 jazz, comparing to presentations, 8– 9, 11, 121 job interviews, expressing true self in, 77–79 Jobs, Steve, 75, 117, 139, 148–151 jounetsu (passion), 100 judo (the way of gentleness), 190 The Naked Presenter Wow! eBook <WoweBook.Com> K N kaizen (continuous improvement, 72 Kanji, 100 karoshi (death by overwork), 47 Kashima Shin School, 124 Kawasaki, Guy, 81 Keynote technology, 9 keynote, presentation tips from, 148– 151. See also presentations Ki (life force), 176 Kodo: Ancient Ways, 71 Nakamura, Masa, 112 naked approach, explained, 10 naked relationship, (hadaka no tsukiai), 5– 6 natural delivery, 25 natural expression of self, 13–14 naturalness, 6 of childhood, 195 speaking with, 7–8 nature Japanese affection for, 6–7 learning from, 6 negatives, overcoming in stories, 44 Negroponte, Nicholas, 129–130 nervousness, avoiding mention of, 74 Newman, Paul, 76–77 notes overcoming dependence on, 15–16 using, 54 Novel aspect of PUNCH, 66– 67 numbers, interpreting, 150, 153 L lavalier mic, considering, 86–87 learning by doing, 144– 145 process of, 72, 111 role of play in, 123 lectern, presenting from, 116 life force (ki), 176 Life in Three Easy Lessons, 176 lifelong learning (shogai gakushu), 186 lights, leaving on, 88 Lusensky, Jakob, 85 M Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, 164 Marsalis, Wynton, 8, 11 martial way (budo), 124 masks, removing, 21 material, knowing, 121 Maui photo of girl, 122–123 Road to Hana, 48 warning sign, 48 McKee, Robert, 43–44, 46 Medina, John, 32, 40, 108, 137–138 memory and emotions, 108 microphone, considering, 86 Mifune, Kyuzo, 190–191 mirror neurons, 110–112 mistakes, overcoming, 119 Miwa, Yoshida, 112 monotone, impact on speeches, 139 Monta Method, 157 Moon, Richard, 176 moving audiences, 34 moving with purpose, 83– 84 multitasking myth, 32 O ofuro (Japanese bath), 5, 20–23 onsen (Japanese hot springs), 5– 6 O-sensei (great teacher), 175 outline, introducing, 75 outside onsen (roten-buro), 21 P pace attention and need for change, 137–138 changing, 140–143 changing for speaking, 159 varying, 136–140 varying in keynotes, 151 participation, 144 asking for volunteers, 156 asking questions, 152 audience activity, 144– 145 building with hands, 156 conducting brainstorming activities, 155 discussion groups, 157 encouraging, 152, 154– 159 showing visuals, 154 sketching ideas, 156 stimulating imaginations, 158 Index 203 Wow!

The End of Work

by

Jeremy Rifkin

Published 28 Dec 1994

The problem has become so acute that the Japanese government has even coined a term, karoshi, to explain the pathology of the new production-related illness. A spokesperson for Japan's National Institute of Public Health defines karoshi as "a condition in which psychologically unsound work practices are allowed to continue in such a way that disrupts the worker's normal work and life rhythms, leading to a buildup of fatigue in the body and a chronic condition of overwork accompanied by a worsening of preexisting high blood pressure and finally resulting in a fatal breakdown."12 Karoshi is becoming a worldwide phenomenon. The introduction of computerized technology has greatly accelerated the pace and flow of activity at the workplace, forcing millions of workers to adapt to the rhythms of a nanosecond culture.

…

Dohse, Knuth, Jurgerns, Ulrich, and Maisch, Thomas, "From Fordism to Toyotism? The Social Organization of the Labor Process in the Japanese Automobile Industry," Politics and Society 14 #2, 1985, pp. ll5-146. 5. Sakuma, Shinju, and Ohnomori, Hideaki, "The Auto Industry," ch. 2 in Karoshi: When the Corporate Warrior Dies, National Defense Council for Victims of Karoshi (Tokyo: Mado-sha Publishers, 1990). 6. Kenney, Martin, and Florida, Richard, Beyond Mass Production: The japanese System and Its Transfer to the u.s. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 271. 7. Ibid., p. 278. 8. "Management by Stress," Technology Review, October 1988, p. 37.

…

S., 182-83 Israel, agriculture in, 115 Italy demand for shorter workweek in, 224 fear of immigrants in, 214 third/volunteer sector in, 276 unemployment in, 203 Japan auto industry in, 99-100,130,131 demand for shorter workweek in, 226-27 elimination of jobs in, 105 jichikai,277-78 just-in-time production in, 99-100 kaizen, 97-98 Index karoshi,186 koeki hojin, 277 lean production in, 96-100 post-Fordist production, 94-95 Real-World Program in, 61 steel industry in, 133 -34 stress in the workforce in, 183-84, 185,186 third/volunteer sector in, 276-78 unemployment in, 4, 198 - 99 Jeantet, Thierry, 242 Jichikai,277-78 John Deere Co., 110 Johnson, John, 78 Johnson, Lyndon, 82,261 Jones, Barry, 223 Jones, Daniel, 94-95, 96, 99,100 Joseph, Jim, 275 Just-in-time production, 99-100, 201 Just This Once, 159 Kahn, Tom, 74 Kaizen,97-98 Kajdasz, Ann, 171 Karoshi,186 Kawasaki, 133 Keener, Robert, 193 Kellogg, W.

Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked

by

Adam L. Alter

Published 15 Feb 2017

Since the late 1960s, but especially in the past two decades, Japanese workers have whispered about karoshi, literally “death from overworking.” The term applies to workers, particularly mid- and high-level executives who struggle to leave work behind at the end of the day. As a result, they die prematurely from strokes, heart attacks, and other stress-induced ailments. In 2011, for example, the media described an engineer who died at his desk at a computer tech company called Nanya. The engineer had worked between sixteen and nineteen hours per day, sometimes from home, and an autopsy suggested that he died from “cardiogenic shock.” A recurring theme in karoshi cases is that victims spend far more time at work than necessary.

…

Etkin, “The Hidden Cost of Personal Quantification,” Journal of Consumer Research, forthcoming). The same technology: On overworking and karoshi, see: Daniel S. Hamermesh, and Elena Stancanelli, “Long Workweeks and Strange Hours,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review (forthcoming); Christopher K. Hsee, Jiao Zhang, Cindy F. Cai, and Shirley Zhang, “Overearning,” Psychological Science 24 (2013): 852–59; Lauren F. Friedman, “Here’s Why People Work Like Crazy, Even When They Have Everything They Need,” Business Insider, July 10, 2014, www.businessinsider.com/why-people-work-too-much-2014-7; International Labour Organization, “Case Study: Karoshi: Death from Overwork,” International Labour Relations, April 23, 2013, www.ilo.org/safework/info/publications/WCMS_211571/lang—en/index.htm ; China Post News Staff, “Overwork Confirmed to Be Cause of Nanya Engineer’s Death,” China Post, October 15, 2011, www.chinapost.com.tw/taiwan/national/national-news/2011/03/15/294686/Overwork-confirmed.htm.

…

(IGN column), 178 Italian Job, The (movie), 191–92, 204 Jarecki, Andrew, 199 Jeong, Ken, 279–80 Jinx, The (real-life crime documentary), 199–200 Jobs, Steve, 1, 2, 4 John, Daymond, 279–80 Johnson, Eric, 209 Journey, 202 juice, 137–39 Just Press Play program, 304–5 Kagan, Jerome, 19–20 Kahneman, Daniel, 282 Kaiser Foundation, 245–46 Kappes, Heather, 161 Kardashian, Kim, 158 “Karma Police” (Radiohead), 195 karoshi (death from overworking), 186–87 Keas, 300–302 Kennedy, Joe, 279–80 khat leaf, 31 King, 137 Klosterman, Chuck, 109–10 Koenig, Sarah, 196, 197, 203 Kondo, Marie, 207–8 KonMari, 207–8 Kotler, Steven, 142 Kraft, Robert, 116 Krieger, Mike, 216–17 Kulagin, Mikhail, 172–73 Lancet, 296 Lantz, Frank, 164–65, 188–89, 300 Larson, Michael, 100–106 Larson, Teresa, 106 Lawrence, Andrew, 82–85 laziness, 305–6 leaderboards, 298 League of Legends (game), 228 learning, gamification of, 302–5 Lee, Hae Min, 196, 198, 200, 203 Lego, 174 Lewis, Michael, 119 Liar’s Poker (Lewis), 119 Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, The (Kondo), 207–8 likes/like button, 127–29, 217 Lindner, Emilee, 159 LinkedIn, 128 Litras, Janie, 103 Little Mister Cricket (game), 138–39 LiveOps, 306–7 Long, Ed, 103 Lord of the Rings (Tolkien), 305 loss aversion, 152–54 losses disguised as wins, 133–34 love, 75–78 Love and Addiction (Peele), 76 “Love Is Like Cocaine” (Fisher), 75–76 Lovematically, 128–29 Love (TV show), 212 Luckey, Palmer, 141–42 Lucky Larry’s Lobstermania (slot machine), 133–34 ludic loops, 177–79 Lumos Labs, 313 MacInnis, Cara, 265 Mad Men (TV show), 290 Making a Murderer (real-life crime documentary), 199–200 mapping, 139 marathon runners, and goal-setting, 95–97 Marks, Isaac, 76–77 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 275 Matheus, Kayla, 282–83 Medalia, Hilla, 252 medical benefits, of gamification, 309–12 Meier, Darleen, 206–7 melatonin, 69–70 memory, and addiction, 57–60 micro-cliffhangers, 205–8 microfeedback, 136–37 Microsoft, 28–29 Milner, Peter, 52–57, 67 Miyamoto, Shigeru, 147–49, 155, 166 Mochon, Daniel, 173 Moment (app), 13–15 Morrissey, Tracie, 159 Moti, 282–83 motivated perception, 144–45 motivational interviewing, 258–62 MUDs (multiuser dungeons), 227–28 Murphy, Morgan, 48 Muscat, Luke, 164 Myst, 3 Myst (game), 178 nail-biting, 267–69 Nanya, 186 National Public Radio, 196 Nature, 312 NBC News Online, 197 Neanderthals, 30 near wins, 145–46, 181–83 negative reinforcement, 21 Netflix, 3, 199, 208, 210–12, 287–89, 291 NeuroRacer, 312 New York Times, 48, 141, 215–16 Nguyen, Dong, 42–43 nicotine, 31 nicotine gum, 267 Nintendo, 148, 171 Nixon, Richard, 47–48 no. 3 heroin, 46 no. 4 heroin, 47 nomophobia, 15 Norton, Michael, 173 O’Brien, Conan, 84, 243 obsession, 20–21 obsessive passion, 21–22 Oculus VR, 140–42 Olds, James, 52–57, 58, 67 O’Neill, Essena, 220–21 online shopping, 4 on-the-job training, gamification of, 308–9 opium, 31 optimal distinctiveness, 226 origami, 173–74 overcoming addictive behaviors, 263–92 behavioral architecture and, 273–92 distraction and, 267–73 habits and, 268–73 replacing bad routines with good, 268–71 subconscious attraction to ideas railed against and, 264–65 willpower, role of, 265–66 overworking, 186–88 pain, and gamification, 309–10 Pajitnov, Alexey, 170, 171, 172, 173 Parkinson’s disease patients behavioral addictions as side effect of drug treatments for, 82–85 overcoming small hurdles and, 93–95 Paskin, Willa, 212 passion, 21 Patrick, Vanessa, 272 Pavlok, 279–81 Peele, Stanton, 76, 77–79, 88 Pelling, Nick, 298, 306 Pemberton, John, 36–38, 273 Penfield, Wilder, 19 Penn, Hugh, 46 penny auction websites, 152–55 Peretz, Jeff, 194–94 perfectionism, 107–9 Perry, Steve, 202, 203 Petrie, Ryan, 226–27 Pettijohn, Adrienne, 103 Pfizer, 301–2 Phelps, Andy, 305 Philips Sonicare, 300 pineal gland, 69–70 Pinterest, 122 pituri plant, 31 planning fallacy, 289–90 “pleasure center” of brain, 55 points, 298, 299 Pokémon (game), 155 Pokhilko, Vladimir, 170 Polk, Sam, 118–19 Polkus, Laura, 216 Pommerening, Katherine, 41–42 Popular Science, 17 pornography, 4, 265–66 post-play, 208, 210–12 post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), gamification as intervention for, 311–12 Powell, Mike, 100 Power of Habit, The (Duhigg), 268 Prelec, Dražen, 188 predatory video games, 155–59 Press Your Luck (TV show), 101–5 progress, 147–66 barriers to entry, lack of, 161–64 beginner’s luck and, 159–62 Dollar Auction Game, trap in, 149–52 energy systems, use of, 155–57 hooks in games and, 149–55 penny auction websites and, 152–55 positive feedback and, 158–59 smartphone delivery of games and, 164–66 proximity of temptation, 273–77 psychological response to experience of addiction, 73–75, 77–79 Pullen, John Patrick, 8 punding behaviors, 81–82 punishment, in breaking habits, 278–81 PurseForum, 207 Quest to Learn (Q2L), 302–4 Quibids.com, 152 Radiohead, 195 Rae, Cosette, 178–79, 249, 274 Raising Men Lawn Care, 307–8 rat experiments, of Olds and Milner, 52–57 readiness ruler, 259 Realism, 269–70 real-life crime documentaries, 196–201 Reddit, 122–25 red light, 69 regrams, 217 reinforcing good behaviors, 282–84 relational spending, 284 repression, 264 reSTART, 17–18, 62–63, 178, 228, 248–50, 255 reward, of habits, 268–69 Ricciardi, Laura, 199 Rift (game), 140–42 Robins, Lee, 50–52, 60, 67 Rochester School of Technology Just Press Play program, 304–5 Rolling Stone, 196 routine, of habits, 268–69 Routtenberg, Aryeh, 56–59 Rustichini, Aldo, 315 Ryan, Maureen, 203 Rylander, Gösta, 81, 84 Sacca, Chris, 140 Sales, Nancy Jo, 41–42 Saltsman, Adam, 155–56, 163–64 SAT vocabulary learning, gamification of, 296–97 Schachter, Stanley, 275–76 Schreiber, Katherine, 112–13, 115, 185 Schüll, Natasha Dow, 130, 134–35, 155, 183 Science, 168 Sedaris, David, 113–14 Self-Determination Theory (SDT), 260–62 “September” (Earth, Wind & Fire), 194–95, 196 Serial (podcast), 196–99, 200, 203, 204 Sesame Street (TV show), 247 Sethi, Maneesh, 279, 280–81 sexuality, 264–65 Shlam, Shosh, 252 shopping, compulsive, 205–8 Shubik, Martin, 149–51 Sign of the Zodiac (game), 130, 131 Sim, Leslie, 112–13, 114–15, 185–86 Simester, Duncan, 188 Simmons, Bill, 140 Simpsons, The (TV show), 145–46 Singer, Robert, 264 SiteJabber.com, 154 Sitzmann, Traci, 308–9 sleep deprivation, 68–70 Sleep Revolution, The (Huffington), 68–69 slot machines, 130–36, 183 smartphone addiction, 22 disruptive nature of, 15–16 overuse of, 13–15 Realism as treatment for, 269–70 scope of, 27–28 video games and, 164–66 smart watches, 113 Smith, Rodney, Jr., 307 Smith, Sandra, 112 SnowWorld, 309–10 SnŪzNLŪz, 278 social comparison, 118–19 social confirmation, 224–25 social interaction, 214–33 extensive online interactions at young ages, long-term effect of, 228–33 Hot or Not website and, 221–26 Instagram and, 216–17, 218 in multiuser games, 227–28 negative feedback in, 219–21 optimal distinctiveness and, 226 positive feedback in, 218–19 social confirmation and, 224–25 Sopranos, The (TV show), 201–3, 204 Space Invaders (game), 148 Spark Joy (Kondo), 208 Sperry, Roger, 19 SpongeBob SquarePants (TV show), 247 Steele, Robert, 48 Steiner-Adair, Catherine, 39, 41, 250–51 Stephen, Christian, 141 stereotypies, 84 Stern, Rick, 103 stopping rules, disruption of, 184–90 butt-brush effect and, 184 credit cards and, 188 exercise and, 185–86 overworking and, 186–88 video games and, 188–89 streaks, 115–16, 117 Strumsky, Dawn, 115 Strumsky, John, 115, 116 substance addiction, 8–9, 29–39 blurring of line behavioral addiction and, 81, 82–85 brain patterns and, 70–71 in early civilizations, 30–31 Freud’s research and experiments with cocaine and, 33–36 manufacturing process and, 31–32 Pemberton’s French Wine Coca (Coca-Cola) and, 37–38 punding behaviors and, 81–82 trial and error, discovery of drug effects by, 32 of Vietnam War veterans, 46–52 Sullivan, Roy, 111 Super Hexagon (game), 179–81 Super Mario Bros.

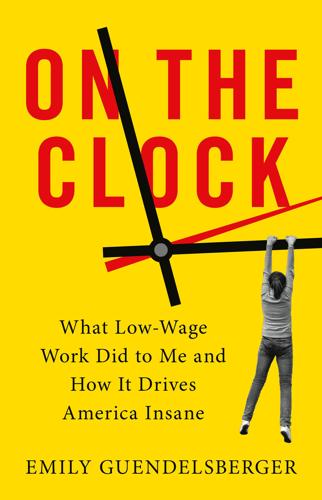

On the Clock: What Low-Wage Work Did to Me and How It Drives America Insane

by

Emily Guendelsberger

Published 15 Jul 2019

It’s making us sick and terrified and cruel and hopeless. And it’s killing us. In the 1970s, Japan coined a new word—karoshi, meaning death by overwork—after businessmen in their thirties and forties started dropping dead from strokes, heart attacks, and suicide after working twenty-hour days for months at a time. Giving the phenomenon a name, starting to measure it, and imposing a nontrivial punishment on the companies driving it were the first steps in keeping karoshi from getting out of hand. There’s now words for karoshi in Mandarin, Korean, and other Asian languages, though today they’re mostly applied to blue-collar factory workers, not well-paid businessmen.

…

Ciulla The Betrayal of Work: How Low-Wage Jobs Fail 30 Million Americans, Beth Shulman Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century, Jessica Bruder Where Bad Jobs Are Better: Retail Jobs Across Countries and Companies, Francoise Carre and Chris Tilly “We Are All Fast-Food Workers Now”: The Global Uprising Against Poverty Wages, Annelise Orleck On Wanda Stone Age Economics, Marshall Sahlins Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, Robert Sapolsky Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir The Panopticon Writings, Jeremy Bentham Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work, Paul Babiak and Robert D. Hare Karoshi, National Defense Counsel for Victims of Karoshi On tech, automation, and the future of work The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee The Glass Cage: Automation and Us, Nicholas Carr Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World, Christopher Steiner Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions, Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, Simon Head Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, Martin Ford The Robots Are Coming!

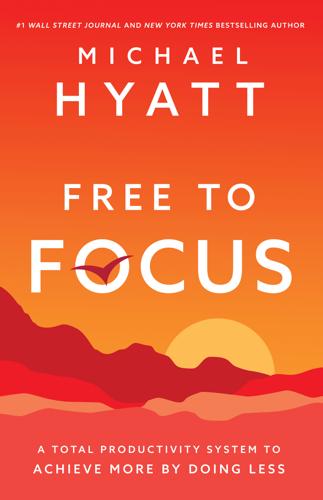

Free to Focus: A Total Productivity System to Achieve More by Doing Less

by

Michael Hyatt

Published 8 Apr 2019

They identified low pay, long hours, and heavy workloads as the three biggest contributors.7 Unsurprisingly, a recent Global Benefits Attitudes Survey of workers found stressed employees have significantly higher absentee and lower productivity rates than their happier, healthier peers.8 Most sobering of all, researchers say workplace stress factors in at least 120,000 deaths per year in the US alone.9 During the 1970s in Japan the problem was so acute, they coined a word for it: karoshi, “death by overwork.”10 Clearly, if our goal in increasing productivity is to achieve some vague notion of “success,” we aren’t doing it right. Sick, dead, or dying doesn’t sound successful to me. We aren’t robots. We need time off, rest, time with family, leisure, play, and exercise. We need big chunks of time when we aren’t thinking about work at all, when it’s not even on our radar.

…

Michael Blanding, “National Health Costs Could Decrease If Managers Reduce Work Stress,” Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, January 26, 2015, https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/national-health-costs-could-decrease-if-managers-reduce-work-stress. 10. Chris Weller, “Japan Is Facing a ‘Death by Overwork’ Problem,” Business Insider, October 18, 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-karoshi-japanese-word-for-death-by-overwork-2017-10. Jake Adelstein, who has worked in Japanese media, said 80-to-100-hour weeks are routine: “Japan Is Literally Working Itself to Death: How Can It Stop?” Forbes, October 30, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/adelsteinjake/2017/10/30/japan-is-literally-working-itselfto-death-how-can-it-stop. 11.

…

See smartphone Center for Creative Leadership, 15 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 74 Chesterfield, Lord, 162, 180 Churchill, Winston, 71, 81–82 circumstances, 61 clarifying one’s objectives, 225 Clayton, Russell, 75–76 clearing the decks, 224–25 Cloud, Henry, 77 clutter, 218–19 commitments, 96–99 elimination of, 108–10 to free time, 111 confusion, 193 connect, 195 connections, 77–79 Consolidate, 21, 161–81 contribution, 48 control, taking vs. surrendering, 196 coordination, 168–69 Costolo, Dick, 81 counterproductive productivity, 17–18 Covey, Stephen, 191 coworkers, 78 “cozy rut,” 99 creativity and changing environment, 72 through disengagement, 37 freeing up, 117 and play, 79 Currey, Mason, 117 Cut, 19–21, 89–158, 227 Daily Big 3, 196–202, 204, 220, 226 Daily Rituals Worksheet, 135 decluttering workspace, 218–19 deep work, 33, 52, 164, 197, 210, 215, 218 deferring, 190 delayed communication, 208–9 Delegate, 21, 137–57, 168 levels of, 148, 149–56 and mentoring, 153 process, 145–49 as smart and organizationally sound, 140 Delegation Hierarchy, 141–46 Designate, 21, 183–204 Desire Zone, 49, 51–53, 55–59, 97, 98, 101, 140, 144–45, 146, 199–201 developing potential, 61 development, 168, 169–70 Developmental Zone, 53–55 digital technology, 14–16 Dillard, Annie, 161 disappointing people, 107–8 discipline, 59–60 Disinterest Zone, 49–50, 55, 100, 116, 143–44, 146 disruptions, minimizing of, 221 Distraction Economy, 13–14, 185, 206, 227 distractions, 35, 212–15, 226 Distraction Zone, 50–51, 55, 99, 100, 144, 146 doing nothing from time to time, 36–37 Doland, Erin, 218 dopamine, 209, 215 downhill tasks, 213–15 drink, 73 Drudgery Zone, 48–49, 50, 55, 58, 100, 109, 116, 142–43, 144 eating, 72–74, 195 Edison, Thomas, 71 efficiency, 27–30 Eisenhower, Dwight, 81 Eisenhower Priority Matrix, 191–94, 199 Eisner, Michael, 69 Eliminate, 21, 91–113, 168, 190 email, 13, 15–16, 29, 85, 120, 163, 179 filtering software, 130–31 signature feature, 124 templates, 123–24 energy, 74, 86–87 energy drinks, 73 energy flexing, 68, 87, 101 energy management, 78 energy producers and drains, 78 environment, taking charge of, 218 Ericsson, Anders, 54 Evaluate, 19, 43–64, 87 evening ritual, 119 Evernote, 127 exercise, 74–77 exhaustion, 66–67 Fabritius, Friederike, 208, 220 Facebook, 71, 78, 213 factory workers, 28, 38 fake work, 14, 99, 214 family and friends, time with, 35–36, 41, 170 fear of missing out, 193 feedback, 149 focus, 33–35, 180, 206 Focus@Will, 217 Focus Defense Worksheet, 221 focus tactics, 215–20 food, 72 Ford, Henry and Edsel, 38 Ford Motors, 38–40 Formulate, 19, 25–42, 87 freedom, 41 Freedom (app), 215–16 Freedom Compass, 45, 55–58, 64, 96–97, 195, 226 freedom (productivity objective), 33–37 freedom to be present, 35–36 freedom to be spontaneous, 36 freedom to do nothing, 36–37 freedom to focus, 33–35 free time, commitment to, 111 frenetic schedules, 84 Fried, Jason, 164 friendships, time for, 79 Front Stage, 166, 167–68, 171, 173, 176, 178–79, 197 frustration tolerance, 219–20 gardening, 97 Gates, Bill, 81 Gazzaley, Adam, 213 Gernsback, Hugo, 205, 212 Google Voice number, 210 Grant, Ulysses S., 81 guilt, 193 Hagemann, Hans, 208, 220 Hallowell, Edward, 215 Hansen, Morten T., 67 Hardy, Benjamin, 218 Hastings, Reed, 71 health, 228 Heinemeier, David, 164 hobbies, 41, 79, 228 Holland, Barbara, 71 Ideal Week, 119, 162, 172–81, 226 Ideal Week template, 182 I Love Lucy (TV program), 25–26 impairment, 70 Information Economy, 13 innovation, and changing environment, 72 instant communication, 207–11 instant-gratification culture, 84 interruptions, 207–11, 226 Isolator, 205–6, 212 Jobs, Steve, 111 Johnson, Paul, 81–82 Jones, Charlie “Tremendous”, 50 journaling, 220 karoshi (death by overwork), 32 Kennedy, John F., 71 King, Stephen, 223 knowledge workers, 28 Koch, Jim, 200, 202 Lewis, Penelope A., 70 liberating truths, 59–63 lifestyle objectives, 38 limiting beliefs, 59–63 “loss of separation,” 184 lunch, 72 MacArthur, Douglas, 71 McCartney, Paul, 99 McKeown, Greg, 183 macro-processing software, 131–32 maintenance, 168, 169 margin, 33, 36, 52, 111, 157, 224, 225, 226 meals, and building relationships, 74 meetings, 197 MegaBatching, 162, 163–66, 172, 180–81 mental health, 83 mentoring, 153 Michel, Alexandra, 65–66 Michelangelo, 21, 100 micro-breaks, 82–83 micromanagers, 149 Miller, Megan Hyatt, 54 mindset, 54 Minor, Dylan, 78 morning ritual, 119 Mortimer, Ian, 223 movement (exercise), 74–77, 195 multitasking, 161–62, 212 music, 217 musicians, 46 Musk, Elon, 67–68 Naish, John, 161, 212 naps, 71 Nashville, 46 natural foods, 73 nature, 82–83 necessary routines, 147–48 Netflix, 71 Newport, Cal, 161–62, 164 Not-to-Do List, 93, 99–100, 113 Nozbe, 202 nutrition, 73 nutritional supplement protocol, 73 offloading tasks, 138, 225–26 Off Stage, 166, 170, 173, 176, 195 OneNote, 127 Opipari, Ben, 75 outdoors, 82–83 overgrowth.

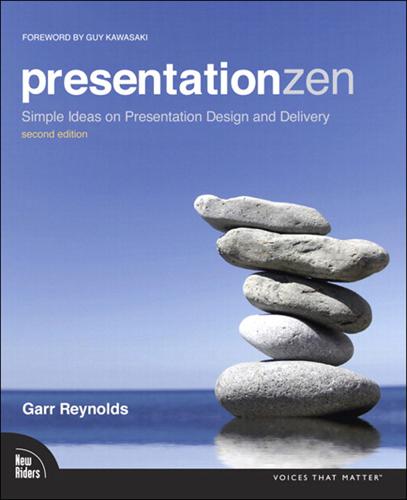

Presentation Zen

by

Garr Reynolds

Published 15 Jan 2012

Three days later, when I asked other students to recall the most salient points of the presentation, what they remembered most vividly were not the labor laws, the principles, and the changes in the labor market in Japan but, rather, the topic of karoshi, or suicide related to work, and the issue of suicides in Japan, topics that were quite minor points in the hour-long presentation. Perhaps five minutes out of the hour were spent on the issue of karoshi, but that’s what the audience remembered most. It’s easy to understand why. The issue of death from overworking and the relatively high number of suicides are extremely emotional topics that are not often discussed. The presenters cited actual cases and told stories of people who died as a result of karoshi. The stories and the connections they made with the audience caused these relatively small points to be remembered because emotions such as surprise, sympathy, and empathy were all triggered

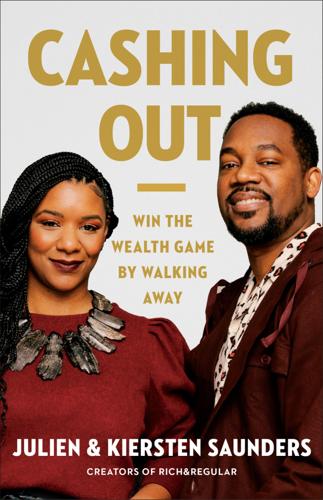

Cashing Out: Win the Wealth Game by Walking Away

by

Julien Saunders

and

Kiersten Saunders

Published 13 Jun 2022

Public opinion didn’t start to shift until President Eisenhower, famous for smoking four packs of cigarettes a day, collapsed on vacation. His heart attack caused the stock market to plummet $14 billion in a single day.[6] What has to happen before we connect the dots between public health and work? Do we need a big scary name for it? In Japan they call it karoshi—death caused by overwork or exhaustion. According to a Business Insider article, “In the US, 16.4% of people work an average of 49 hours or longer each week. In Japan, more than 20% do.”[7] From climate change and nutritional standards, to the health benefits of cannabis and extreme wealth inequality, to the struggle for civil rights and the current push for economic empowerment, America has proven how gifted it is at ignoring the truth until there is little choice left.

…

BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 5 Sean Braswell, “President Eisenhower’s $14 Billion Heart Attack,” OZY, April 12, 2016, www.ozy.com/true-and-stories/president-eisenhowers-14-billion-heart-attack/65157. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 6 Chris Weller, “Japan Is Facing a ‘Death by Overwork’ Problem—Here’s What It’s All About,” Business Insider, Oct. 18, 2017, www.businessinsider.com/what-is-karoshi-japanese-word-for-death-by-overwork-2017-10. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 7 Faith Among Black Americans, Pew Research Center, Feb. 16, 2021, www.pewforum.org/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 8 Chapter 3 | The Purpose(s) of Income “It’s in the Bag: Black Consumers’ Path to Purchase,” Nielsen Holdings, Sept. 12, 2019, www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/09/2019-african-american-DIS-report.pdf.

…

Black neighborhoods, 40 HSAs (health savings accounts), 94, 168 thehumblepenny.com, 215 I identity and constraints of labels, 191–92 decoupling from employment status, 95, 146–47, 231 maintaining, 34 and millionaire status, 233 tied to belongings, 59 See also personality types, financial impostor syndrome, 209 income assumptions about future levels of, 62 building an income portfolio, 85 dual-income households, 75–76 envisioning new ceilings for, 147 exchanging time for wages/salary, 124–27, 138 and fifteen-year careers, 75–76 focusing on earning more, 72–73 and inflation, 148 influence of boss on potential, 101 and low-wage workers, 76 median earning in 2019, 59 and net worth, 54–55 from outside your primary job, 94–95 qualitative assessments of, 148 from real estate investing, 86–88 as related to wealth, 54–55 relative value of, 90 and six-figure salaries, 147 stagnation in wages, 173 technology’s unlocking of, 139 and wage gaps, 3, 139 See also purpose(s) of income index funds advantages of, 162–63, 177–78 and author’s early investments, 157 Bogle’s championing of, 167 and compensation of financial advisers, 152–54 deflecting costly alternatives to, 169–71 and great American experiment, 158–59 and historical average returns in stock market, 162–63 low costs associated with, 161, 164–65 passive management of, 161 performance of, in 2020, 230 power of, 154–58, 171 Purple’s embrace of, 92 in taxable brokerage accounts, 168 individualism in America, 214 individual retirement accounts (IRAs), 94, 114 inflation, 148, 173 influencers, 141–45 initial public offerings (IPOs), 174 insinuation anxiety, 171 Instacart, 131 intelligence, 112 internet and content creators, 141–45 FI community on, 216–17, 220–21 as global marketplace, 139 impact on entrepreneurship, 128–29 selling on, 137, 139–40 See also social media platforms investment/brokerage accounts (unrelated to employer) apps of, 131 of authors, 168 contributing to, 97 opening, 89, 176 rounding-up programs at, 118 for short-term needs, 94 See also investments investment clubs, 170 investments actively managed funds, 160, 166, 171 authors’ self-management of, 6 calculated risks in, 174–75 and compound interest, 140, 155, 172 and consistency in investing, 175, 176 and downturns in market, 98–99, 173–74 early growth in, 167 and expense ratios, 163–64 fees associated with, 163–66, 170, 171, 172 and financial vs. fiduciary advisors, 149–54 the first $100,000, 166–69 and 4 percent rule, 66–67 and historical average returns in stock market, 162–63, 168 in individual retirement accounts (IRAs), 94, 114 and investment firms, 167 and market boom of 2020, 232–33 and matching by employers, 156, 176 and money’s ability to work harder than you can, 172–73, 228 procrastinating on, 154–55, 177 Purple’s financial independence, 92–93 reluctance to manage, 150–51 rules and richuals for, 172–78 and taxes, 165 true costs of, 163–66, 171 in years 11–15 of career, 94 See also 401(k)s; index funds; mutual funds IPOs (initial public offerings), 174 IRAs (individual retirement accounts), 94, 114 “I” statements, power of, 194 J Jackson, Michael, 101–2 Japan, average hours spent at work in, 32 Johnson, Dwayne “the Rock,” 112–13, 114 Johnson, Sue, 189 Journey to Launch (Souffrant), 217 K Kajabi, 137 karoshi, 32 thekeyresource.com, 85 King, Martin Luther, Jr., 40–41 L labels, constraints of, 191–92 lending practices, unfair, 3 lifestyles and financial freedom, 34–35 “lifestyle inflation,” 39, 61 values focused, 26, 35 work focused, 25–26 LinkedIn, 90, 134 literacy, financial, 108–11 livestreaming, 145 living below your means, 72.

Affluenza: When Too Much Is Never Enough

by

Clive Hamilton

and

Richard Denniss

Published 31 May 2005

Superannuation fund advertisements showing couples in their golden years walking hand in hand on the beach exploit this image, yet many retirees find that after a lifetime of long working hours they have neither the relationship nor the living skills to realise the dream. Working ourselves sick Health The Japanese workplace is notorious for karoshi—death by overwork. A study of Japanese employees who had died from cardiovascular 92 OVERWORK attack found that over two-thirds had worked more than 60 hours a week, 50 overtime hours a month or more than half of their fixed holidays before their attack.15 In Australia, too, many employees are working themselves towards an early death.

…

CHAPTER 11 1 Lambesis Agency 2004, L Style Report, 9th edn, <http://www.lstylereport.com> [11 January 2005]. 209 INDEX Abbott, Tony, 133 advertising, 4, 28, 36–40, 41, 43, 55, 61, 101, 109, 120, 126,172, 187 and neuroscience, 41–2 fake memories in, 46 children and, 47, 50–51 of breakfast cereals, 48–50, 150–1 of cars, 10, 45 of junk food, 51 of margarine, 43 of tobacco, 51–2, 125 of vitamins, 94 restrictions on, 188 use of nagging, 53–4 affluenza, defined, 3, 7 alcohol, 115–17, 180 annual leave see holiday leave anorexia, 16 appliances, 22–3, 37, 38 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, 55 Aussie battler, 3, 133–4, 136, 139, 151, 180, see also politics Australian Labor Party, 3, 137–9, 151, 191 bankruptcy, 72–3, 175 banks, 12, 75–6, 77–80 barbecues, 23–4 210 INDEX Blair, Tony, 191 botox, 37, 128 brands, 23, 34, 38–40, 41–33, 45, 53, 55, 56, 110, 187 brand loyalty, 39, 55, 189 brand disloyalty, 190 see also advertising; marketing Bray, Robert, 66 Buddhism, 17 caesareans, 34 Calvinism, 16, 17 cars, 10, 13, 45 4WDs, 44–5, 188 see also advertising celebrity, need for, 56–7 children, 21 advertising and, 47–57, 150 and clothes, 33–4 as fashion accessories, 33 behavioural problems of, 55 financial calculus of having, 34–5, 142–5, impact of materialism on, 149–50 sexualisation of, 57 tinys, 52–3 tweens, 55–7 see also downshifting choice, alleged benefits of, 40–1 clothes, 13, 45, 166 see also children Coalition Government, 136–9 see also Liberal Party community, 95, 119, 146, 148, 183 compulsive shopping, 15, 61 see also oniomania conscious consumption, 166, 186–90 conspicuous consumption, 8, 88, 96 cosmetic surgery, 10, 57, 127–9, see also botox cosmetics, 37 Costello, Peter, 35, 141 credit cards, 10–2, 19, 72–81, 102, 103 see also debt debt, 71 passim, 137, 179 attitudes to, 74, 75 Debtors Anonymous, 61, 80–1 foreign debt truck, 82 home equity loans, 79–80 marketing of, 71, 75–7 national debt, 81–4 211 AFFLUENZA deferred happiness syndrome, 89–2, 98, 169 deferrers, 175–6 see also deferred happiness syndrome democratisation of luxury, 26 depression, 16, 38, 93, 114 deprivation, 3, 66, 192, see also poverty, hardship disease-mongering, 120–7 doorbuster sales, 78 downshifters characteristics of, 154–6 motivations of, 156–7, 158 passim new lifestyle of, 165–7 regrets of, 173 downshifting, 17, 152, 153 passim, 180 children and, 156, 159, 160, 166–7 defined, 153 for dogs, 33 politics of, 175, 183–6 reactions to, 176–70 drugs, 114–16, 118 Easterlin, Richard, 6 Eckersley, Richard, 148 economic growth, 3, 4–5, 62–3, 114, 118, 136, 141, 159, 185, 190, 193 environment, 111, 112, 157, 179, 190, 193, 194 evangelical Christianity, 182–3 family size, 20–1 federal election 2004, 3, 136–8 female sexual dysfunction, 121–3 feminism, 27 flexible work hours see work hours Frank, Robert, 9 Frey, Bruno, 63 full employment, 192 gratifiers, 175 growth fetishism, viii, 18, 142, 193 Guevara, Che, 28 happiness, 58, 63–4, 113, 118, 127, 146, 152, 175–6 hardship imagined, 64 genuine, 66 212 INDEX Hayek, Friedrich, 186 health, 113, 156, 157, 164, 166, 179, 193 see also work hours hedonic treadmill, 6, 58, 184 holiday leave, 87, 88, 93 Hood, Robin, 190 houses, 13, 20, 60, 101 size of, 20, 21–2, 37 prices of, 20, 21–2, 134, 137, 179 Howard, John, 82, 138, 141, 142 Idell, Cheryl, 53 identity, 13–4, 45 imports, 73, 83–4 incomes, 4, 58–9, 112 Indigenous Australians, 113 intermittent husband syndrome, 91 karoshi, 92 Kasser, Tim, 14 Klein, Naomi, 38 Latham, Mark, 137, 138 Liberal Party, 136, 138, 139, 151 Luis Vuitton, 9, 28 luxury fever, 8–10, 12, 19, 135, 143, 178 luxury goods, 9–10, 13, 16, 19, 21, 26, 127, 170 Mandelson, Peter, 191 marketing, 13, 28, 37–8, 42, 45, 47, 53, 104, 110–1, 118, 120, 126, 179 see also advertising materialism, 14–5, 17, 47, 55, 89, 119, 154, 184 and values, 146–52 meningococcal disease, 120 middle class, 8–9, 59, 74, 136 middle-class welfare, 139-42, 180 Mill, John Stuart, 138, 186 money, 5, 7, 11, 16–7, 19, 58, 63, 67–8, 80, 97, 98–9, 103, 107, 112, 120, 139, 143–4, 148, 152, 159, 166, 171, 175–7, 178, 187 hunger for, 6, 17, 18, 137, 146, 180, 183–4 see also debt money coma, 80 Moynihan, Ray, 121, 123 213 AFFLUENZA needs, 4, 7, 29, 59–63, 65, 66, 100, 147, 148 neoliberalism, 7, 17, 36, 39–40, 79, 138 as new form of oppression, 186 of relationships, 182 of tax cuts, 136, 139 of the Aussie battler, 133–5, 151 of welfare, 139, 140, 141, 180 of wellbeing, 193–4 progressive, 181, 182 pornography, 151 post-materialism, 4, 155, 157, 184 poverty, 18, 181, 190–2 poverty line, 66–7 presenteeism, 94 privatisation, 40 psychology, role in marketing, 36–41, 46, 51, 53–4, 61 obesity, 118 obsolescence, 110 oniomania, 15–6 see also compulsive shopping Olsen twins, 57 O’Neill, Jessie, 7 ovens, 22–3 overconsumption, 7, 19 passim, 72, 96, 122, 178 overwork see work hours Pavlov, Ivan, 41, 47 plastic bag levy, 103 pets, 28–33 humanisation of, 30, 33 pharmaceutical companies, 120–1, 126 Pocock, Barbara, 98 politics, 60–1, 66, 119, 183 conservative, 144, 181, 190 of choice, 168, 172 relationships, 14, 81, 97, 179, 193, 194 relationship debts, 175 see also work hours retail therapy, 16, 100–1 retirement anxiety, 92, 173–4 right-hand ring, 27 Ritalin, 118 Roberts, Kevin, 39 saving, 71, 82 see also debt 214 INDEX Schor, Juliet, 48 sea change, 153, 155 see also downshifting self-storage industry, 25, 102 social anxiety disorder, 124–6 status, 170 Stutzer, Alois, 63 suffering rich, 63 sunglasses, 25–6 television, 9, 21, 22, 60, 183, 188 lifestyle programs, 37 sales, 24–5 Trapaga, Monica, 49–50 trickle down theory, 191 twin deficits theory, 83 values, 180–3 see also materialism Veblen, Thorstein, 8 Vidal, Gore, 6 voluntary simplicity, 154, 187 see also downshifting wasteful consumption, 100 passim, 179, 190, 194 and guilt, 106–8, 112 wealth, 81–2 whitegoods, 23 see also appliances wellbeing, 14, 40, 54, 58, 113, 115, 118, 142, 163, 190 wellbeing manifesto, 193, 217–24 work hours, 81, 91, 95–6, 158, 161, 163, 174, 179 and children, 90–1 excessive, 85–9, 158 impact on communities, 95–7 impact on health, 90–4, 122 impact on relationships, 85, 90, 91, 97–9, 122, 149 working class, 8–9 workophiles, 87 215 A political manifesto for wellbeing Preamble Australians are three times richer than their parents and grandparents were in the 1950s, but they are not happier.

Working Hard, Hardly Working

by

Grace Beverley

We’re then sold this idea of ‘working smart’ as an alternative, savvy option, but even that doesn’t seem to be legitimate unless we also put in a humbly braggable number of hours. In this sense, ‘productivity’ has lost its value as a desired part of our working lives, and become equivalent to a machine-like churning of output, getting as much work out of ourselves as we physically can before we just pack in one day and, well, die. (Not-so-fun fact: karoshi is the haunting Japanese term to describe those who die from a sudden heart attack or stroke caused by excessive overworking,1 most commonly translated as ‘overwork death’.) Or maybe, the churning stops when we realise we can never win this contest, and we take a step back and settle in for the long run.

…

Chapter Four: Defining Success 1 ‘who we are …’, Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success (Allen Lane, 2008). 2 Diagram on this page adapted from an Instagram post by Dr Nicole LePera (@the.holistic.psychologist), 2 May 2020. 3 ‘Impostor syndrome’, definition taken from Audrey Ervin, quoted in Abigail Abrams, ‘Yes, Impostor Syndrome Is Real. Here’s How to Deal With It’, Time, 20 June 2018. 4 ‘inner thermostat setting’, Gay Hendricks, The Big Leap: Conquer Your Hidden Fear and Take Life to the Next Level (New York: HarperOne, 2009). Chapter Five: Redefining Productivity 1 ‘karoshi is the …’, Justin McCurry, ‘Japanese woman “dies from overwork” after logging 159 hours of overtime in a month’, Guardian, 5 October 2017. 2 ‘In 2019 (while …’, Trade Unions Congress, ‘British workers putting in longest hours in the EU, TUC analysis finds’, issued 17 April 2019, available on tuc.org.uk. 3 ‘compared to any …’, Alan Jones, ‘British workers put in longest hours in EU, study finds’, Independent, 17 April 2019. 4 ‘Taking a look …’, Alanna Petroff and Océane Cornevin, ‘France gives workers “right to disconnect” from office email’, CNN Business, 2 January 2017. 5 ‘divvy up jobs …’, Jacinda Ardern, quoted in Karen Foster, ‘The day is dawning on a four-day work week’, The Conversation, 4 June 2020. 6 ‘In her essay …’, Jia Tolentino, ‘The I in Internet’, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion (London: Fourth Estate, 2019).

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by

Rodrigo Aguilera

Published 10 Mar 2020

As a recent article on the Harvard Business Review stated, [T]o be ideal workers, people must choose, again and again, to prioritize their jobs ahead of other parts of their lives: their role as parents (actual or anticipated), their personal needs, and even their health.7 Work also kills. Less so in the old ways of dying in an industrial accident, but more through the grinding accumulation of stress and unhealthy habits that in the long run take their physiological toll, whether through heart attacks, strokes, or just dropping dead. The Japanese have a name for it — karōshi — which literally means “overwork death”, and in their first comprehensive survey of the problem published in 2016 listed ninety-six such deaths the year before plus ninety-three suicides and suicide attempts. That was only the tip of the iceberg. Japanese authorities also revealed that as many as 2,159 suicides in 2015 were partly work-related.8 This would represent nearly one in ten suicides, hardly an insubstantial figure, and the problem also appears endemic in many East Asian countries, including China and South Korea.9 Why does liberal democracy tolerate these excesses?

…

, Glassdoor Economic Research, 17 Feb. 2016, https://www.glassdoor.com/research/studies/europe-fairest-paid-leave-unemployment-benefits/ 7 Reid, E. and Ramarajan, L., “Managing the High-Intensity Workplace”, Harvard Business Review, Jun. 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/06/managing-the-high-intensity-workplace 8 Otake, T., “1 in 4 Firms in Japan Say Workers Log Over 80 Overtime Hours a Month”, Japan Times, 7 Oct. 2016, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/10/07/national/social-issues/1-in-4-firms-say-some-workers-log-80-hours-overtime-a-month-white-paper-on-karoshi/ 9 “Suicides Down in 2015 in Japan but Numbers Still Serious Among Young, Elderly”, Japan Times, 31 May 2016, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/05/31/national/social-issues/suicides-2015-japan-numbers-still-serious-among-young-elderly 10 Roser, M., “Economic growth”, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth 11 Zakaria, T., “Bush Defends Free Market System Ahead of G20”, Reuters, 13 Nov. 2008, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-financial-summit-bush-idUKTRE4AC7Z320081113 12 “State of the Union with Candy Crowley”, CNN, 14 Nov. 2010, http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1011/14/sotu.02.html 13 “Obama on the opportunities of capitalism”, Kellog School of Management, 2 Oct. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Extreme Teams: Why Pixar, Netflix, AirBnB, and Other Cutting-Edge Companies Succeed Where Most Fail

by

Robert Bruce Shaw

,

James Foster

and

Brilliance Audio

Published 14 Oct 2017

The same is true for the work done by visionary leaders in cutting-edge firms—they will stay with a task and strive to reach a goal to a degree that can only be described as abnormal. Obsession, then, is essential to reach the highest levels of performance. But most people view obsession as a negative quality—a type of psychological disorder. In Japan, the word karoshi refers to those who die as a result of working around the clock. In English, it roughly translates into “worked to death and died like an ox.” Japan, of course, is not alone in having a segment of its population that is addicted to work. In the United States, there is an association that calls itself Workaholics Anonymous.

…

Herrin, Jessica, on hiring highly aligned hiring process at Airbnb cultural fit in at Pixar at Zappos holacracy Holbrook, Richard, on conflict House of Cards (television show) Housman, Michael Hsieh, Tony on culture on customer service as founder of Zappos influence of, at Zappos ideas conflict about generation of IDEO incremental innovation ingroups innovation at Airbnb at Google incremental at Netflix at Whole Foods Inside Out (film) internal competition Ives, Jony, on results vs. relationships Jobs, Steve communal culture created by as founder of Pixar legacy of on results Kahn, Matthew, on military desertion karoshi Lasseter, John on Disney Animation and Pixar as founder of Pixar on supporting employees loosely coupled loyalty, to teams Ma, Jack on culture on ethics on finding right people as founder of Alibaba leadership of on obsession on playful culture Mackey, John Appalachian Trail hiked by on building teams as founder of Whole Foods on teams on transparency Maner, Jon Mayer, Marissa, on priorities McCord, Patty, on performance measurement Mead, Margaret, on change men, expectations for Michaud, Jon Microsoft military loyalty Minor, Dylan missions, non-financial Motorola Musk, Elon, as visionary leader Musk, Justine NASA Nemeth, Charlie Nest Labs Netflix accountability at autonomous culture at changing priorities at context setting at cultural fit at culture at experimentation with priorities at future of incremental innovation at personnel management by relationships and results at self-imposed limitations on transparency at Net Promoter Score (metric) New York Times Nike Notes, at Pixar obsession benefits and risks of in building teams as characteristic of extreme teams characteristics of companies with with culture definition of and grit at Patagonia at Pixar risks of with societal impact of company as team vs. personal trait with work at Zappos Onward (Howard Schultz) origins stories, of companies outcomes, for key priorities Patagonia “all in” culture at cultural fit at culture at ingroups at obsession at relationships at self-imposed limitations on shift to organic cotton at Perez, William performance metrics for evaluation of teams for individuals and teams at Zappos Personal Emotional Connection (metric) personal trait, obsession as personnel management at Nest Labs at Netflix at Pixar Pixar collaboration at communal culture at conflict at cultural fit determined at culture at Disney Animation under leadership of emotional support at experimentation with priorities at future-forward focus of hiring process at obsession at performance evaluation at personnel management by teams at work reviewed at playful culture plussing postmortems, at Pixar power issues priorities at Airbnb in building teams as characteristic of extreme teams context setting for development of priorities, (cont.)

Busy

by

Tony Crabbe

Published 7 Jul 2015

We are flatlining at full speed ahead. When we don’t allow this pulsing between on and off, we fail to allow ourselves to recover. This causes an allostatic load6—best described as accelerated wear and tear on the body and brain. In Japan there is a word for the consequences of this: karoshi, which means “death from overwork.” Karoshi happens when chronic fatigue, stemming from long hours and persistent stress, lead otherwise healthy young adults to drop down dead from a stroke or heart attack. Increasing your allostatic load through constant busyness reduces your thinking power, your performance and your memory, and increases all kinds of health risks: cardiovascular disease, reduced immune system performance and early death.

No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention

by

Reed Hastings

and

Erin Meyer

Published 7 Sep 2020

The behavior of the boss is so influential that it can even wipe out national cultural norms. Before becoming CPO, Greg served for a time as Netflix’s general manager in Tokyo. In Japan, businesspeople are famous for long work hours and taking little time off. There are stories of people working so much there, they literally die from it. There’s even a word for this phenomenon, karoshi. The average Japanese worker uses about seven vacation days a year, and 17 percent take none at all. One evening over beer and sushi, Haruka, a manager in her early thirties, told me, “In my last job, I worked for a Japanese company. For seven years, I arrived at work at 8:00 a.m. and I took the last train home just after midnight.

…

A Academy Awards, xvii, 165, 233 “accept or discard” feedback guideline, 31, 33 accidents and safety issues, management style and, 213–14, 269–71 “actionable” feedback guideline, 30, 31, 33, 36, 193, 257 “adapt” feedback guideline, 264 “aim to assist” feedback guideline, 30, 31, 33, 36 Airbnb, 136 Alexa and Katie, 145 alignment, 217–18, 231 on a North Star, 218–21 as tree, 221–31 Allmovie.com, 87 Amazon, 3, 81, 97, 136, 208, 232 Prime, 146, 148 amygdala, 21 Anitta, 97 annual performance reviews, 191 Antioco, John, xi–xii AOL, xviii, 236 Apple, xvii, 77, 97 “appreciate” feedback guideline, 31, 33 Arc de Triomphe, 268–69 Ariely, Dan, 83 Armstrong, Lance, 207, 232–33 Aronson, Elliot, 124 Aspen Institute, 107–8 autonomy, 133 see also decision-making; decision-making approvals, eliminating Avalos, Diego, 151 B Ballad of Buster Scruggs, The, xviii Ballmer, Steve, 122–23 Baptiste, Nigel, 64–66, 68 Bazay, Dominique, 223, 224, 227–31 Bde Maka Ska, 267, 268 Becker, Justin, 35–36 belonging cues, 24–25 bet-taking analogy, 138–40, 153–57, 225–27 Bird Box, 165 Blacklist, The, 26 Black Mirror, 157–59 Blitstein, Ryan, 52 Blockbuster, 3, 171, 236 bankruptcy of, xii, xviii late fees of, 3 Netflix’s offer to, xi–xii size of, xi, xii bonuses, 80–84 Booz Allen Hamilton, 81 brain: feedback and, 20, 21 secrets and, 103 Branson, Richard, xxiv, 50 Brazil, 137, 150, 224–26, 243, 247, 249–51, 257, 264 Brier, David, xxiv brilliant jerks, 34–36, 200 Brown, Brené, 123 Bruk, Anna, 123–24 Bull Durham, 169 Bullock, Sandra, 165 bungee jumping, 194–95 C Canada, 241 candor, 18–21, 141, 175 cultural differences around the world, 250-55, 260, 263–64 culture of, 22–23 dentist visits compared to, 190–91 as disliked but needed, 20–22 failure to speak up, 18, 27, 141 increasing, xx, xxi, 1, 12–37, 72, 100–127, 188–205 jerks and, 34–36 misuse of, 29, 30, 36 “only say about someone what you will say to their face,” 15, 189–90 performance and, 17–20 and readiness to release decision-making controls, 133–35 saying what you really think with positive intent, 13–37 see also feedback; transparency Carey, Chris, 181 Caro, Manolo, 137 Caruso, Rob, 113–14 Casa De Papel, La, xviii celebrating wins, 140, 152 Chapman, Jack, 86 Chase, Chevy, 222 cheating, 62–64 Chelsea, 115–16 children’s programming, 144–45, 226–31 Choy, Josephine, 252–54, 257 Christensen, Nathan, 51 circle of feedback (360-degree assessments), 26–27, 189–205 benefits of, 202–3 discussion facilitated by, 194 in Japan, 256 live, 197–203 stepping out of line during, 200–201 tips for, 199–200 written, names used in, 191–97 Cobb, Melissa, 221–27, 231 Coen, Joel and Ethan, xii Coherent Software, 101, 104 collaboration, 170, 178 Colombia, 251 Comparably, xvii competitiveness, internal, 177–78 compliments and praise, 21, 23 computer software, 77–78, 216 conformity, 141–42 connecting the dots, xxiv first dot, 10–11 second dot, 36 third dot, 69 fourth dot, 98 fifth dot, 125 sixth dot, 160 seventh dot, 185 eighth dot, 203–4 ninth dot, 233 last dot, 264–65 consensus building, 149 contagious behavior, 8–10 context, see leading with context, not control contract signing, 149–51 control, leadership by, 209 ExxonMobil example of, 213–14 leading with context versus, 209–12 see also leading with context, not control controls, removing, xx, xxi, 1, 38–72, 128–61, 206–36 decision-making approvals, 129–61 bet-taking analogy in, 138–40, 153–57, 225–27 Informed Captain model in, 140, 149–52, 216, 223, 224, 231, 248 and picking the best people, 165–66 readiness for, 133–35 signing contracts, 149–51 travel and expense approvals, 55–72 cheating and, 62–64 company’s best interest and, 58, 59, 61, 66, 68–69 context and, 59–62 Freedom and Responsibility ethos and, 60–62 frugality and, 64–69 vacation policy, xv, 39–53, 56, 69–70 freedom and responsibility and, 52–53 Hastings’ nightmares about, 40–41, 42, 44 Hastings’ vacations, 44, 45, 47 Japanese workers and, 46–47 leaders’ modeling and, 42–47 loss aversion and, xv–xvi and setting and reinforcing context to guide employee behavior, 48–49 value added by, 50–52 see also leading with context, not control corporate culture, xiii of Netflix, xiii, xxii, xxiii, 45 Netflix Culture Deck, xiii–xvi, 172–73 Costa, Omarson, 150–51 coupling: alignment and, 218 loose versus tight, 215–17 Coyle, Daniel, 24 creative positions, 78–79, 83–84 criticism (negative feedback), 19–21, 23 belonging cues and, 24 brain and, 20, 21 cultural differences around the world, 251, 261 as disliked but needed, 20–22 language used in, 251–52 responding to, 24, 31 upgraders and downgraders in, 251–52 see also feedback Crook-Davies, Danielle, 19–20 Crown, The, xvii Cryan, John, 82–83 Cuarón, Alfonso, xii, 165 cultural differences around the world, see global expansion and cultural differences Culture Code, The (Coyle), 24 culture map, 242–50 Culture Map, The (Meyer), xxii, 19, 242–50 culture of freedom and responsibility, see Freedom and Responsibility D Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead (Brown), 123 Dark, xvii days off, 39–40 see also vacation policy, removing decision-making: dispersed, 216–17 innovation and, 130, 131, 135, 136 and leading with context, 210, 216, 217 to please the boss, 129–30, 133, 152–53 pyramid structure for, 129, 221–23 spreadsheet system and, 143–44 talent density and, 131 transparency and, 131 decision-making approvals, eliminating, 129–61 bet-taking analogy in, 138–40, 153–57, 225–27 Informed Captain model in, 140, 149–52, 216, 223, 224, 231, 248 and picking the best people, 165–66 readiness for, 133–35 signing contracts, 149–51 Del Castillo, Kate, 138 Del Deo, Adam, 207–9, 232–33 Disney, 144, 221, 222, 226, 227 dissent, farming for, 140–44, 158 diversity, 241 Dora the Explorer, 145 Dormen, Yasemin, 157–59 dot-com bubble, 4 dots, see connecting the dots downloading, 146–48 dream teams, 76 DreamWorks, 145, 221, 226 driver feedback, 22 Dutch, Netherlands, 242, 243, 246, 248, 251, 261–63 DVDs, 3–4, 5, 129 Qwikster and, 140–42 shift to streaming from, xii, xvii, 140–41, 236 E Edmondson, Amy, xv Eichenwald, Kurt, 176 Eisner, Michael, 195 elephants, penguins versus, 174 Elite, xvii Emmy Awards, xvii, 145 “Emperor’s New Clothes” syndrome, 23–29 empowerment, 109, 133, 134 see also decision-making; decision-making approvals, eliminating; Freedom and Responsibility Engadget, 158 Enron, xiii entrepreneurship, 138 error prevention, and management style, 213–14, 220, 269–71 Escobar, Pablo, 132 Estaff meetings, 218–19, 243 Evening Standard, 25 Eventbrite, 50 expenses, see travel and expenses; travel and expense approvals, removing experimentation, 138 Explorer project, 154–55, 157 Express, 158 ExxonMobil, 213–14 F Facebook, xiii, 77, 97, 130, 137, 195 failures, 140, 152–59 asking what learning came from the project, 153, 155 not making a big deal about, 153–55 sunshining of, 153, 155–59 family business metaphor, 166–68 moving to sports team metaphor from, 168–70, 173–74 farming for dissent, 140–44, 158 Fast Company, xxiv, 213 fear of losing one’s job, xv, 178–80, 183–84 Fearless Organization, The (Edmondson), xv FedEx, 139 feedback, 14–17, 139, 175, 190, 240 annual performance reviews and, 191 belonging cues and, 24 brain’s response to, 20, 21 circle of (360-degree assessments), 26–27, 189–205 benefits of, 202–3 discussion facilitated by, 194 in Japan, 256 live, 197–203 stepping out of line during, 200–201 tips for, 199–200 written, names used in, 191–97 cultural differences and, 250-57, 260, 261–64 for drivers, 22 “Emperor’s New Clothes” syndrome and, 23–29 failure to speak up with, 18, 27, 141 4A guidelines for, 29–36, 255, 264 accept or discard, 31, 33 actionable, 30, 31, 33, 36, 193, 257 adding 5th A to (adapt), 264 aim to assist, 30, 31, 33, 36 appreciate, 31, 33 cultural differences and, 260 for giving feedback, 30 for receiving feedback, 31 frequency of, 18 Hastings and, 26–29 honesty in, 18; see also candor Japanese culture and, 251–57 loop of, 22–23 Meyer and, 19, 32 negative (criticism), 19–21, 23 belonging cues and, 24 brain and, 20, 21 cultural differences around the world, 251, 261 as disliked but needed, 20–22 language used in, 251–52 responding to, 24, 31 upgraders and downgraders in, 251–52 positive, brain and, 21 responding to, 24, 31 and speaking and reading between the lines, 253 spreadsheet system for gathering, 143–44 survey on, 21–22 teaching employees how to give and receive, 29–32 from teammates, 199 when and where to give, 31–34 see also candor Felps, Will, 8–9 firing, see letting people go Fisher Phillips, 50 five-year plans, 219–20 Flint, Joe, 178 flexibility, and leading with context or control, 220, 221 Fogel, Bryan, 207–8, 233 4K ultra high definition televisions, 65–66 Fowler, Geoffrey, 65–66 Fox, 221 France, 240, 251 Paris, 268–69 Freedom and Responsibility (F&R), xx–xxi, 191, 236, 267, 268 expenses and, 60–62 first steps to, 1–72 Informed Captain model in, 140, 149–52, 216, 223, 224, 231, 248 next steps to, 73–161 techniques to reinforce, 163–236 vacations and, 52–53 weight of responsibility in, 150–52 Friedland, Jonathan, 196 Fuller House, 145 G Game of Thrones, 131–32 Garden Grove, Calif., 22 Gates, Bill, 78 General Electric (GE), 177–78 Germany, 147–48, 250–51 Gizmodo, 178 Gladwell, Malcolm, 142 Glassdoor, xv, 50 global expansion and cultural differences, 237–65, 239–65 adjusting your style for, 257–61 Brazil, 137, 150, 224–26, 243, 247, 249–51, 257, 264 candor and, 250–55, 260, 263–64 culture map, 242–50 feedback and, 250–57, 260, 261–64 Google and, 240–41 Japan, 46–47, 183, 224, 225, 257, 261 in culture map, 243, 247, 248 feedback and criticism in, 251–57 Japanese language, 252–53 360 process and, 256 Netherlands, 242, 243, 246, 248, 251, 261–63 Schlumberger and, 240–41 Singapore, 243, 246, 248, 251, 257–59, 261, 264 trust and, 248, 249 Golden Globe Awards, xvii, 76 Goldman Sachs, 177 Golin, 50 Google, xvii, 77, 94–96, 98, 136 global expansion of, 240–41 gossip, 189 Guillermo, Rob, 207 H Handler, Chelsea, 115–16 happiness, xvii Harvard Business Review, xxii Hastings, Mike, 87 Hastings, Reed: childhood of, 10, 13 at Coherent Software, 101, 104 downloading issue and, 146–48 feedback and, 26–27 interview with, 173–80 in leadership tree, 224–25 marriage of, 13–15 Meyer contacted by, xxii–xxiii Netflix cofounded by, xi, 3–4 in Netflix’s offer to Blockbuster, xi–xii in Peace Corps, xxii, xxiii, 14, 101, 239–40 Pure Software company of, xviii–xix, xxiv, 3, 4, 6, 7, 13–14, 55, 64, 71, 101, 122, 123, 236 Qwikster and, 140–42 HBO, 113–14, 208 Hewlett-Packard (HP), 66–67 hierarchy of picking, 165–66 Hired, xvii hiring: hierarchy of picking and, 165–66 talent density and, see talent density honesty, xvi, xxiii, 178 and spending company money, 58–59 see also candor; transparency hours worked, 39 House of Cards, xvii, 65, 75, 171, 236 HubSpot, xvii, 50 Huffington Post, xxii Hulu, 208, 232 humility, 123 Hunger Games, The, 176 Hunt, Neil, 41, 45, 94, 98, 154, 196 downloads and, 146, 148 and Netflix as team, not family, 173–74 360s and, 197, 198 vacations of, 41 I Icarus, 207–8, 232–33 India, 83, 84, 147–48, 224–26 Mighty Little Bheem in, 228–31 industrial era, 269, 271 industry shifts, xvii–xviii, xix Informed Captain model, 140, 149–52, 216, 223, 224, 231, 248 innovation, xv, xix, xxi, 84, 135–36, 155, 271–72 decision-making and, 130, 131, 135, 136 and leading with context or control, 214–15, 217 Innovation Cycle, 139–40 asking what learning came from the project, 153, 155 celebrating wins, 140, 152 failures and, 140, 152–59 farming for dissent, 140–44, 158 not making a big deal about failures, 153–55 placing your bet as an informed captain, 140, 149–52 socializing the idea, 140, 144–45, 158, 159 spreadsheet system and, 143–44 sunshining failures, 153, 155–59 testing out big ideas, 140, 146–48 International Olympic Committee, 232 internet, 146–48, 154 internet bubble, 4 iPhone, 130 Italy, 131–32 J Jacobson, Daniel, 166–68 Jaffe, Chris, 153–57 Japan, 46–47, 183, 224, 225, 257, 261 in culture map, 243, 247, 248 feedback and criticism in, 251–57 Japanese language, 252–53 360 process and, 256 jerks, 34–36, 200 Jobs, Steve, xxiv, 130 Jones, Rhett, 178 K karoshi, 46 kayaking, 180 Keeper Test, xiv, 165–87, 240, 242 Keeper Test Prompt, 180–83 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), 81, 191, 209 Kilgore, Leslie, 14–15, 81, 94, 171 expense reports and, 61–62 on hiring and recruiters, 95–96 “lead with context, not control” coined by, 48, 208–9 new customers and, 81–82 signing contracts and, 149–50 360s and, 192, 193, 197, 198 King, Rochelle, 27–29 Kodak, xviii, 236 Korea, 224, 225 Kung Fu Panda, 221 L Lanusse, Adrien, 148 Latin America, 136, 241, 249 Brazil, 137, 150, 224–26, 243, 247, 249–51, 257, 264 Lawrence, Jennifer, 176 lawsuits, 175 layoffs at Netflix, 4–7, 10, 77, 168 leading with context, not control, 48, 207–36 alignment in, 217–18, 231 on a North Star, 218–21 as tree, 221–31 control versus context, 209–12 decision-making in, 210, 216, 217 Downton Abbey-type cook example, 211–12, 218 error prevention and, 213–14, 220, 269–71 ExxonMobil example, 213–14 Icarus example, 207–8, 232–33 innovation and, 214–15, 217 Kilgore’s coining of phrase, 48, 208–9 and loose versus tight coupling, 215–17 Mighty Little Bheem example, 228–31 parenting example, 210–11 spending and, 59–62 talent density and, 212, 213 Target example, 213–15 lean workforce, 79 letting people go, 173–76 “adequate performance gets a generous severance,” xv, xxii, 171, 175–76, 242 employee fears about, xv, 178–80, 183–84 employee turnover, 184–85 in Japan, 183 Keeper Test, xiv, 165–87, 240, 242 Keeper Test Prompt, 180–83 lawsuits and, 175 at Netflix, 185 Netflix layoffs in 2001, 4–7, 10, 77, 168 post-exit communications, 117–20, 183–84 quotas for, 178 LinkedIn, 50, 51, 137 Little Prince, The (Saint-Exupéry), 215 loose versus tight coupling, 215–17 Lorenzoni, Paolo, 131–33, 135, 138 loss aversion, xv–xvi Low, Christopher, 258–60 M Mammoth, 51 Management by Objectives, 209 Man of the House, 222 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 83 McCarthy, Barry, 14–15, 56 McCord, Patty, 4–7, 9, 10, 15, 27–28, 41, 53, 71, 173 all-hands meetings and, 108 departure from Netflix, 171 expense policy and, 55, 60–61 financial data and, 110 salary policy and, 78, 81, 94, 96 team metaphor and, 169 360s and, 197–99 vacation policy and, 40, 43, 45, 52–53 Memento project, 156, 157 Mexico, 136–38 Meyer, Erin, xxii The Culture Map, xxii, 19, 242–50 Hastings’ message to, xxii–xxiii keynote address of, 19, 32 Netflix employees interviewed by, xxiii, 19–20 in Peace Corps, xxii micromanaging, 130, 133, 134 Microsoft, 78, 122, 176–78 Mighty Little Bheem, 228–31 Mirer, Scott, 200–201 mistakes, 121–25, 271–72 distancing yourself from, 157 management style and, 213–14, 220, 270 sunshining of, 157 see also failures Morgan Stanley, 123 Moss, Trenton, 50–51 Mr.

Work Less, Live More: The Way to Semi-Retirement

by

Robert Clyatt

Published 28 Sep 2007

. • Dutch, Austrians, and Swedes working more than 48 hours per week: 1% to 2% • Western Europeans working more than 48 hours per week: 5% • Americans working more than 48 hours per week: 20% • Japanese working more than 48 hours per week: 28% • Japanese dying each year from karoshi, the official term for Death by Overwork: 10,000 Sources: Jon Messenger, “Working Time and Workers’ Preferences in Industrial Countries, Finding the Balance” (Routledge Studies in the Modern World Economy, 50); and Hiroshi Kawahito, National Defense Council for Victims of Karoshi, quoted in Yomiuri Shimbun Online 50 | Work Less, Live More Slow Progress in America America has experienced various reform movements designed to make work more meaningful and empowering.

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by

Gabriel Weinberg

and

Lauren McCann

Published 17 Jun 2019

There are lots of phrases related to this concept—overdoing it, trying too hard, etc. (see the Too Much of a Good Thing section in Chapter 2). Law of Diminishing Returns Overdoing it is also a quick path toward burnout, where high stress can take its toll and eventually extinguish your motivation, or worse. In the late 1970s in Japan the term karoshi was coined to describe the increasing number of people, some as young as their twenties and thirties, dying from strokes and heart attacks attributed to overwork. Similar negative returns and burnout are prevalent in the high-stress environment of modern life throughout the world. In the quest for athletic success, for example, children all over the United States are suffering extreme injuries from overtraining—a clear sign of negative returns.

…