A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload

by

Cal Newport

Published 2 Mar 2021

As a result, the knowledge sector prefers to leave these processes unspecified, relying instead on the hyperactive hive mind workflow to informally organize their work. For sure, a major explanation for this process aversion is the insistence on knowledge worker autonomy that we explored earlier. Production processes, by definition, require rules about how work is coordinated. Rules reduce autonomy—creating friction with the belief that knowledge workers “must manage themselves,” as Peter Drucker commanded. This dislike of processes, however, goes beyond a general bias toward autonomy. There’s a belief, implicitly held by many knowledge workers, that the lack of processes in this sector is not just an unavoidable side effect of self-management, but actually a smart way to work.

…

Drucker argued this approach was doomed to fail in the new world of knowledge work, where productive output was created not by expensive equipment stamping out parts, but instead by cerebral workers applying specialized cognitive skills. Indeed, knowledge workers often knew more about their specialties than those who managed them. The best way to deploy these highly skilled individuals, Drucker concluded, was to give them clear objectives and then leave them alone to accomplish their brainy work however they saw fit. While it might have been efficient to tell an assembly line worker exactly how to install a steering wheel, it was futile to try to tell a marketing copywriter exactly how to brainstorm a new product slogan. Drucker preached this idea of knowledge worker autonomy throughout his long career.

…

Drucker preached this idea of knowledge worker autonomy throughout his long career. As late as 1999, he still emphasized its importance: [Knowledge work] demands that we impose the responsibility for their productivity on the individual knowledge workers themselves. Knowledge workers have to manage themselves. They have to have autonomy.35 It’s hard to overestimate the influence of this idea. With the exception of some routinized bureaucratic processes, like filing expense reports, the intricacies of how the myriad demanding tasks that define modern office work are accomplished remain largely beyond the scope of management. They’re pushed instead into the hazy realm of personal productivity.

Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout

by

Cal Newport

Published 5 Mar 2024

* * * — As I witnessed this fast-growing discontent, it became clear to me that something important was happening. Knowledge workers were exhausted—burned out from an increasingly relentless busyness. The pandemic didn’t introduce this trend so much as push its worst excesses beyond the threshold of tolerability. More than a few knowledge workers, thrust suddenly into remote work, their kids screaming in the next room as they suffered through yet another Zoom meeting, began to wonder, “What are we really doing here?” I began extensively covering knowledge worker discontent, as well as alternative constructions of professional meaning, on my long-standing newsletter, as well as on a new podcast I launched early in the pandemic.

…

As I read through more of my surveys, an unsettling revelation began to emerge: for all of our complaining about the term, knowledge workers have no agreed-upon definition of what “productivity” even means. This vagueness extends beyond the self-reflection of individuals; it’s also reflected in academic treatments of this topic. In 1999, the management theorist Peter Drucker published an influential paper titled “Knowledge-Worker Productivity: The Biggest Challenge.” Early in the article, Drucker admits that “work on the productivity of the knowledge worker has barely begun.” In an attempt to rectify this reality, he goes on to list six “major factors” that influence productivity in the knowledge sector, including clarity about tasks and a commitment to continuous learning and innovation.

…

I was interested in Davenport because, earlier in his career, he was one of the few academics I could find who seriously attempted to study productivity in the knowledge sector, culminating in his 2005 book, Thinking for a Living: How to Get Better Performance and Results from Knowledge Workers. Davenport ultimately became frustrated with the difficulty of making meaningful progress on this topic and moved on to more rewarding areas. “In most cases, people don’t measure the productivity of knowledge workers,” he explained. “And when we do, we do it in really silly ways, like how many papers do academics produce, regardless of quality. We are still in the quite early stages.” Davenport has written or edited twenty-five books.

Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines

by

Thomas H. Davenport

and

Julia Kirby

Published 23 May 2016

The obvious peril in Era Three is more job loss. This time the potential victims are not tellers and tollbooth collectors, much less farmers and factory workers, but rather all those “knowledge workers” who assumed they were immune from job displacement by machines. People like the writers and readers of this book. Knowledge Workers’ Jobs Are at Risk The management consulting firm McKinsey thinks a lot about knowledge workers; they make up essentially 100 percent of its own ranks as well as its clientele. When its research arm, the McKinsey Global Institute, issued a report on the disruptive technologies that would most “transform life, business, and the global economy” in the next decade, it included the automation of knowledge work.

…

They might finally lead to that fifteen-hour workweek. But our belief is that they will—and should—follow the path blazed by spreadsheets. Instead of replacing knowledge workers, they should give them more to think about. Some decisions and actions may be taken by automated systems, but that should free up knowledge workers to accomplish larger and more important tasks. Of course, there is a downside to working as much as knowledge workers tend to (particularly in the United States) today. But there is perhaps an even greater downside to not working enough or at all. The price we have to pay for thinking expansively about work is never having enough time to do it all.

…

When its research arm, the McKinsey Global Institute, issued a report on the disruptive technologies that would most “transform life, business, and the global economy” in the next decade, it included the automation of knowledge work. Having studied typical job compositions in seven categories of knowledge workers (professionals, managers, engineers, scientists, teachers, analysts, and administrative support staff), McKinsey predicts dramatic change will have already taken hold by 2025. The bottom line: “we estimate that knowledge work automation tools and systems could take on tasks that would be equal to the output of 110 million to 140 million full-time equivalents (FTEs).”3 Since we’ll continue to use the term “knowledge workers” quite a bit, we should pause to define who these people are. In Tom’s 2005 book, Thinking for a Living, he described them as workers “whose primary tasks involve the manipulation of knowledge and information.”4 Under that definition, they represent a quarter to a half of all workers in advanced economies (depending on the country, the definition, and the statistics you prefer), and they “pull the plow of economic progress,” as Tom put it then.

Slack: Getting Past Burnout, Busywork, and the Myth of Total Efficiency

by

Tom Demarco

Published 15 Nov 2001

In my experience, there is never less than a 15 percent penalty due to time-sharing a knowledge worker between two or more tasks. Moving a person who had been assigned to a single job to work part-time on a second exposes you to a loss of at least six hours per week of that person’s time. And the penalty is greater when the partitioning is greater. I limit this statement to knowledge workers, since manual and blue-collar workers may not be affected, or may be less affected, by some of the components of the task-switching penalty. For knowledge workers, though, the minimum penalty is 15 percent. The only method I have used so far to substantiate the 15 percent minimum penalty is a time-honored approach called proof by repeated assertion.

…

Part Four Risk taking and risk management: Why running away from risk is a no-win strategy, and why running toward it makes sense when managed sensibly (and what that entails). Slack is directed toward management at all levels in knowledge organizations and other modern corporations where knowledge workers predominate. It is also directed to the knowledge workers themselves. It’s directed toward you if you sense that there is something terribly wrong in the infernal busyness of the modern workplace, if you know in your heart that the slack that has been squeezed out of your organizations over the last ten years now has to be reintroduced, or no further meaningful progress will ever be possible.

…

Growth is essential to Eve, as essential as her paycheck. You can no more expect her to work without meaningful challenge than you could expect her to work without salary. The nearly equal status of challenge and pay is unique to knowledge workers. They are different from the blue-collar workers that our fathers managed a generation ago. The easy, dumb error of managing knowledge workers is to forget that they are different and assume that basic rules developed on factory floors a century ago apply to them. The Nonprofit Model I had occasion recently to manage a small not-for-profit organization where most of the work was done by volunteers.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

by

Cal Newport

Published 5 Jan 2016

The ubiquity of deep work among influential individuals is important to emphasize because it stands in sharp contrast to the behavior of most modern knowledge workers—a group that’s rapidly forgetting the value of going deep. The reason knowledge workers are losing their familiarity with deep work is well established: network tools. This is a broad category that captures communication services like e-mail and SMS, social media networks like Twitter and Facebook, and the shiny tangle of infotainment sites like BuzzFeed and Reddit. In aggregate, the rise of these tools, combined with ubiquitous access to them through smartphones and networked office computers, has fragmented most knowledge workers’ attention into slivers.

…

In aggregate, the rise of these tools, combined with ubiquitous access to them through smartphones and networked office computers, has fragmented most knowledge workers’ attention into slivers. A 2012 McKinsey study found that the average knowledge worker now spends more than 60 percent of the workweek engaged in electronic communication and Internet searching, with close to 30 percent of a worker’s time dedicated to reading and answering e-mail alone. This state of fragmented attention cannot accommodate deep work, which requires long periods of uninterrupted thinking. At the same time, however, modern knowledge workers are not loafing. In fact, they report that they are as busy as ever. What explains the discrepancy? A lot can be explained by another type of effort, which provides a counterpart to the idea of deep work: Shallow Work: Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted.

…

Benn needed to learn a hard skill, and needed to do so fast. It’s here that Benn ran into the same problem that holds back many knowledge workers from navigating into more explosive career trajectories. Learning something complex like computer programming requires intense uninterrupted concentration on cognitively demanding concepts—the type of concentration that drove Carl Jung to the woods surrounding Lake Zurich. This task, in other words, is an act of deep work. Most knowledge workers, however, as I argued earlier in this introduction, have lost their ability to perform deep work. Benn was no exception to this trend.

The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes

by

Phillip Brown

,

Hugh Lauder

and

David Ashton

Published 3 Nov 2010

Smokestack industries had given way to California’s Silicon Valley and Route 128 in Boston. Working-class occupations were in decline as a larger share of the workforce joined the burgeoning ranks of knowledge workers. Peter Drucker, a leading management guru, wrote of another power shift from the owners and managers of capital to knowledge workers, as the prosperity of individuals, companies, and nations came to depend on the application of knowledge. Knowledge workers were gaining the upper hand because “the firm’s most valuable knowledge capital tends to reside in the brains of its key workers, and ownership of people went out with the abolition of slavery.”10 This required a new approach to management within a dynamic global environment.

…

See mass production mechatronics, 101, 174n27 knowledge economy, 15, 20, 25, 79 knowledge transfer, 70 knowledge wars, 19–23, 28, 30–36, 32, 38, mental revolution, 71 meritocracy, 9, 18, 133–36, 146, 182n3, 187n31 40–41, 43–48, 59, 123, 150–51, 158–59, 164, 168n3. See also knowledge workers; knowledge-driven economy knowledge workers, 6, 8–9, 18–19, 66, 68, 72–76, 80–82, 84, 96, 99, 104, 108, 110–12, 123, 126–27, 137–38, 147–48, Mexico, 35 MG Rover, 42 Michaels, Ed, 85–86, 93, 176n8 micromanagement, 74 middle class as agrarian peasants, 182n48 153, 159, 180n17. See also knowledge wars; knowledge-driven economy knowledge-driven economy, 2, 4–5, 23–27, 37, 65–68, 85, 96, 155, 173n9. See also knowledge wars; knowledge workers 194 labor arbitrage, 97, 99, 106–7, 111, 159 Index Brazil, 182n43 China, 2, 130 corporate profits, 110 downward mobility, 138 emerging economies, 130–31 erosion of benefits, 121–22 financial crash of 2008, 6 global, 128–29, 130, 131 Nike, 102 global poverty, 182n43 globalization, 47–48 growth of, 18 income inequalities, 9, 118–19, 120 income stagnation, 5 Obama, Barack, 3, 23, 27, 147 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 31, 35, 91, 109, 149, 168n2 office management, 72, 127 India, 2, 30, 34, 130 Italy, 130, 182n43 mechanical Taylorism, 81 offshoring, 109, 152 offshoring, 8, 46, 51–52, 55–56, 60, 73, 75, 77–78, 90–93, 99, 107–11, 119, 129, 152, 170–71n2, 180n17 Ohmae, Kenichi, 104–5 opportunity bargain, 132 opportunity gap, 141 opportunity bargain American Dream, 27, 132 oasis operations, 64 opportunity trap, 143 politics of more, 186n16 positional conflict, 134 bidding wars, 183–84n22 corporate profits, 124 credentials, 184–85n2 prosperity, 2 purchasing power parity (PPP), 129, 131 development of, 4–6 digital Taylorism, 65, 155 quality-cost revolution, 59 salaries, 118–19, 120 soft currencies, 140–41 economy of hope, 148–49, 164 education and, 4–6, 27–28 and the global auction, 132 war for talent, 84, 91, 96–97 Mills, C.

…

It encourages the segmentation of talent in ways that reserve permission to think to a small proportion of elite employees responsible for driving the business forward, functioning cheek by jowl with equally wellqualified workers in more Taylorized jobs. Many knowledge workers may disappear off the talent radar screen. This process is at an early stage in many organizations, as we’ve already indicated, but we can distinguish three types of knowledge worker: developers, demonstrators, and drones. Developers include the high potentials and top performers discussed in the next chapter. They represent no more than 10–15 percent of an organization’s workforce given “permission to think” and include senior researchers, managers, and professionals.

Business Metadata: Capturing Enterprise Knowledge

by

William H. Inmon

,

Bonnie K. O'Neil

and

Lowell Fryman

Published 15 Feb 2008

Is this the same type of experience that people would have if they were unable to find information to do their jobs? 4.4.1.1 Information and “Knowledge Workers” Peter Drucker first created the term “knowledge worker” in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The economy of the twenty-first century is an information economy, and most workers today are knowledge workers who produce abstract work products consisting mainly of information, not tangible items like cars or pencils. Therefore, the know-how of the knowledge worker is not necessarily knowledge of everything, but knowing where to find it. Samuel Johnson, who compiled the first English dictionary in the 1700s, said: 66 Chapter 4 Business Metadata, Communication, and Search Figure 4.4 Searching for a Needle in a Haystack.

…

. ✦ The average knowledge worker spends 2.5 hours/day (30%) searching for information. ✦ The enterprise employs 1000 knowledge workers. ✦ 50% of information is not centrally indexed (housed in silos as on someone’s notebook computer or a database). ✦ 50% of Web searches fail/are abandoned. 4.4.2.3 Employee Time Wasted Based on these assumptions, Feldman calculated that the enterprise wastes $48,000 per week, or almost $2.5 million a year in searches. This number is an estimate only; she did not factor in employee vacations. 4.4.2.4 Duplicating/Reworking Information Knowledge workers inadvertently re-create information because they can’t access the original work products.

…

Here is IAIDQ’s definition of information quality (three separate definitions are given, one having two components): Information quality: (1) Consistently meeting all knowledge worker and end-customer expectations in all quality characteristics of the information products and services required to accomplish the enterprise mission (internal knowledge worker) or personal objectives (end customer). (2) The degree to which information consistently meets the requirements and expectations of all knowledge workers who require it to perform their processes. (Larry English, noted data and information quality expert and author) Information Quality: The fitness for use of information; information that meets the requirements of its authors, users, and administrators.

The Lights in the Tunnel

by

Martin Ford

Published 28 May 2011

There is no need for robotic arms or, in fact, any moving parts at all. Another, more common, term for people with software jobs is, of course, knowledge worker. Software jobs are also highly subject to offshoring. The conventional wisdom used to be that becoming a knowledge worker represented the best path to a prosperous future. The advent of offshoring has increasingly called this proposition into question. Today, offshoring is impacting knowledge workers across the board. Jobs in fields such as radiology, accounting, tax preparation, graphic design, and especially all types of information technology are already being shipped to India and to other countries.

…

In fact, we can reasonably say that software jobs (or knowledge worker jobs) are typically high paying jobs. This creates a very strong incentive for businesses to offshore and, when possible, automate these jobs. Another point we can make is that there is really no relationship between how much training is required for a human being, and how difficult it is to automate the job. To become a lawyer or a radiologist requires both college and graduate degrees, but this will not hold off automation. It is a relatively simple matter to program accumulated knowledge into an algorithm or enter it into a database. For knowledge workers, there is really a double dose of bad news.

…

Not only are their jobs potentially easier to automate than other job types because no investment in mechanical equipment is required; but also, the financial incentive for getting rid of the job is significantly higher. As a result, we can expect that, in the future, automation will fall heavily on knowledge workers and in particular on highly paid workers. In cases where technology is not yet sufficient to automate the job, offshoring is likely to be pursued as a interim solution. Given this reality, it may be that the simulation we performed in Chapter 1 was actually somewhat conservative. Look back at the table listing traditional jobs. Very few of these people are knowledge workers. In our simulation, we assumed that automation would fall evenly on some significant percentage of the average lights in the tunnel.

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 29 Nov 2011

Drucker’s enthusiasm for empowerment was reinforced by his belief that the old industrial proletariat was being replaced by knowledge workers. He believed that the advanced world was moving from “an economy of goods” to “a knowledge economy,” and that management was changing as a result: managers needed to learn how to engage the minds, rather than simply control the hands, of their workers. This softer approach was a direct challenge to Taylor’s stopwatch theories and their fans in business. But the idea of a “knowledge worker” (a term that Drucker coined in 1959) also posed questions for politicians. It suggested that rather than defending dying industries against cheaper, less “knowledgeable” workers abroad, governments should concentrate on improving the country’s stock of knowledge, but otherwise keep well out of the way.

…

It suggested that rather than defending dying industries against cheaper, less “knowledgeable” workers abroad, governments should concentrate on improving the country’s stock of knowledge, but otherwise keep well out of the way. Drucker did not confine himself to the question of how managers and governments ought to handle these new knowledge workers. He spent much of his career looking at how the knowledge workers themselves could come to terms with this new world in which they were neither workers nor bosses. Knowledge workers have much more freedom than old-fashioned workers because they control the most important productive asset of modern society: their brainpower. Brainworkers are free, or, in the jargon that Drucker did not invent but unfortunately helped to legitimize, “empowered” to shape their own careers, hopping from firm to firm in pursuit of the highest salary or the most interesting job.

…

Brainworkers are free, or, in the jargon that Drucker did not invent but unfortunately helped to legitimize, “empowered” to shape their own careers, hopping from firm to firm in pursuit of the highest salary or the most interesting job. But freedom could be destabilizing as well as liberating: knowledge workers needed more training and different pension arrangements, for example. Drucker knew whereof he spoke: an itinerant Mittel-European who had dabbled in banking and journalism and always remained ambivalent about America’s hyperspecialized academic system, he was an archetypical knowledge worker. But he was a knowledge worker with a growing number of acolytes in the real world. The younger Henry Ford took The Concept of the Corporation as his text when he tried to rebuild his company after the war.

Head, Hand, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Sep 2020

Clearly some of the value of Teach First has been in attracting more able young people with top degrees back into teaching, but wherever it has been tried it has usually been accompanied by other changes, such as breaking the monopoly of teacher training in education faculties and generally disrupting groupthink in public service professions. A concluding observation: the knowledge worker is increasingly a female worker. The rise and rise of the knowledge worker in the last three decades is also, in part, about the rise and rise of the female professional. Women in the United Kingdom have not only caught up with but overtaken men in jobs that require higher education. In 1997, 28 percent of men and 23 percent of women were in such jobs.

…

Artisanal skills are also being rediscovered in some corners of the economy, especially in food and drink production, often by affluent young professionals. Indeed, a shift away from Head and toward Hand and Heart seems to be programmed into many of the biggest social and economic trends: in the knowledge economy’s declining appetite for all but the most able knowledge workers; the growing concern for place and environmental protection, including more labor-intensive organic farming; and the inevitable expansion of care functions of various kinds in an aging society. These are trends that are likely to be reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis, which revealed that most of the “key workers” who support our daily lives were Hand and Heart workers, mainly people without university degrees.

…

Political parties of both the center-left and center-right have taken as axiomatic that modern society will see a continuing expansion of secure, middle-class, professional graduate jobs. Both education and social mobility policy are based on this assumption. Yet it is almost certainly wrong. The knowledge economy does not need an ever-growing supply of knowledge workers. (See Chapter Nine.) It still needs a top layer of the cognitively most able and original, but much of the work required of middle ranking professionals is already substantially routinized, a kind of digital Taylorism. The American economist Paul Krugman spotted this back in 1996. Writing for the New York Times but imagining himself looking back from one hundred years in the future, he saw that manipulating information was going to lose its value: “The long-ago prophets of the information age seem to have forgotten basic economics… A world awash in information is one in which information has very little market value.

Becoming Data Literate: Building a great business, culture and leadership through data and analytics

by

David Reed

Published 31 Aug 2021

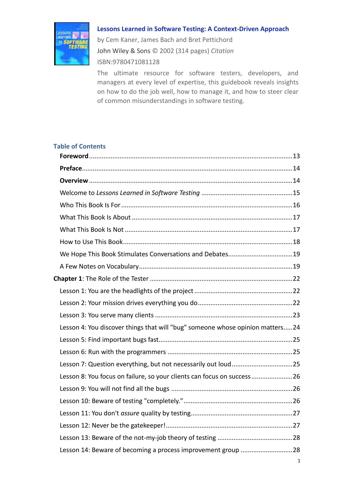

As Figure 6.1 shows, these strongly correlate with creating a data culture, demonstrating leadership and putting key enablers in place. Figure 6.1: The six factors of knowledge worker productivity Source: Centre for Evidence-Based Management - CEBMa The study also identified weightings for five of these factors which had the largest effect (see Table 6.2). Surprisingly, external communication was not found to influence knowledge worker productivity, perhaps because this usually takes place after tasks have been completed and is therefore extrinsic to the work, rather than being intrinsic. Table 6.2: Knowledge worker productivity factors Rank Factor Weighting 1 Social cohesion 0.5–0.7 2 Perceived supervisory support 0.5 3 Information sharing 0.5 4 Vision/goal clarity 0.5 5 Trust 0.3–0.6 Source: Centre for Evidence-Based Management – CEBMa As this analysis clearly indicates, there is huge potential for the data leader to have a positive impact on the productivity of the data department (or indeed the opposite effect), depending on their approach.

…

In service industries, especially those employing knowledge workers (a term coined by Drucker in 1959 in his book, Landmarks of Tomorrow), it is hard to apply such management when there is no predetermined process to follow. Data often relies on a degree of test-and-learn and fail fast in order to reach the appropriate end point. Even then, it is likely that a data set or a model will be subject to constant iteration and optimisation. Sticking at it to achieve the best outcome and recognising the need for continuous improvement is about doing the right thing. A key distinction between traditional workers and knowledge workers stems from this – instead of being subordinates to a boss, they are associates.

…

A key distinction between traditional workers and knowledge workers stems from this – instead of being subordinates to a boss, they are associates. Drucker tackled the shift in approach this requires in his 1999 book, Management Challenges for the 21st Century, where he noted that: “Knowledge workers must know more about their job than their boss does – or else they are no good at all. In fact, that they know more about their job than anybody else in the organisation is part of the definition of knowledge workers.” In recognising that data practitioners are likely to know more about their work – and certainly to be more technically proficient than the data leader – it is clear that a different approach to leading such individuals and teams is required.

Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Writing Science)

by

Thierry Bardini

Published 1 Dec 2000

Engelbart believed that the activity of the knowledge worker actually in- volves "core" processes that for the most part are not themselves highly spe- cialized: "a record of how this person used his time, even if his work was highly specialized, would show that specialized work . . . while vital to his ef- fectiveness, probably occupied a small fraction of his time and effort" (ibid., 10). If so, that meant knowledge workers didn't have to be isolated from each other, segregated by the specific demands of the software necessary to their individual tasks. Instead, they could use a common interface and be connected into a network that would link the user with other users. Envisioning the user as a knowledge worker and conceptualizing the knowledge worker in this par- ticular way allowed Engelbart to begin to see a way in which one central aspect of his crusade could be realized.

…

One way Engelbart sought to exert influence over "the human side" was by developing what he called "the augmented knowledge workshop," "the place in which knowledge workers do their work" (Engelbart, Watson, and Norton 1973, 9). This application of the bootstrapping principle was used between 1965 and 1968 to add another dimension to the ARC lab's conceptualization of the virtual user. Engelbart believed that the activity of the knowledge worker actually in- volves "core" processes that for the most part are not themselves highly spe- cialized: "a record of how this person used his time, even if his work was highly specialized, would show that specialized work . . . while vital to his ef- fectiveness, probably occupied a small fraction of his time and effort" (ibid., 10).

…

If you were will- Ing to put In these ten hours of effort, and also you had to be a little bIt adaptable. You had to be a computer person. (Kay 1992) Thus, the knowledge worker again became a "computer person," but this time it was not the sort of computer person who had undergone the transforma- tions of the bootstrapping enterprise within the community that had evolved within the ARC lab at SRI, but real computer users. What had seemed the most "natural" group of people to start augmenting now became the only group augmented: the knowledge worker became a generic programmer again. The growth of the number of potential users via the ARPANET quickly re- vealed what some considered to be technological flaws in the system: The communIcation, in our lab [ARC at SRI], was very high performance. . . a quarter second response was not at all unusual.

Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won or Lost Together

by

Ian Goldin

and

Tom Lee-Devlin

Published 21 Jun 2023

Inequality has risen in most metropolitan areas in the United States since 1980, but it has risen fastest in large, thriving cities like New York, San Francisco and Chicago, where it is now much higher than the national average.25 Wages for high-skilled knowledge workers in these places have soared, but pay for the low-skilled service workers supporting them has languished, a gulf that is compounded by the rapidly rising cost of living in these cities. As knowledge workers have flocked to gentrifying inner cities in recent decades, these global metropolises have increasingly come to resemble ivory towers, with a highly concentrated core of prosperity served by a sprawling periphery of disadvantage.

…

In one global survey in 2021, a quarter of workers never wanted to go into the office again, while another quarter never wanted to work from home again; the remaining half preferred some kind of middle ground.6 With time we expect that the downsides of remote working – for employee experience and company performance – will lead many companies to increase the share of days that staff are expected to be present in the office. That will place a ceiling on how far away these workers can move. And many knowledge workers with the financial means to do so have chosen to continue living in urban centres despite a shorter commute no longer offering the same advantage. As argued in Chapter 4, the lifestyle of the inner city, with its cultural variety and ease of access to a wide range of services, is a major factor in the appeal of these neighbourhoods. Equally, cities have no cause for complacency. The exodus of knowledge workers from inner cities may well have peaked, but the transition to hybrid arrangements will still have significant implications for offices, public transport systems and municipal finances.

…

The result is that companies in many fast-growing industries want to be located in cities where they feel confident they can access the types of skills they require. This further reinforces the benefit to workers from locating in such areas, in a virtuous cycle of increasing talent density. A second reason for the increasing strength of agglomeration effects is the way in which knowledge workers in particular become more productive when located near to one another. Information may be more available than ever, but the evidence suggests that it still tends to flow largely through in-person networks, spurred on by casual encounters within and outside the workplace. Inventors filing for patents are twice as likely to cite patents from their own city than from other places, even after excluding those generated within the same company.25 The physical proximity of people in cities is particularly important when it comes to drawing inspiration and knowledge from diverse fields.

Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything

by

Steven Levy

Published 2 Feb 1994

In 1973, enchanted by the ideas of economist Peter Drucker, he coauthored a paper called "The Augmented Knowledge Workshop," which was based on the idea, formulated by Drucker, that information was destined to be the fulcrum of the economy. "By 1960," wrote Engelbart, "the largest single group [of Americans] was professional, managerial, and technical-that is knowledge workers. By 1975-1980 this group will embrace the majority of Americans." It was these knowledge workers who would sit in the cybercockpits of the Engelbart augmentation scheme: as he termed it, "the office of the future." Knowledge workers. The office of the future. These twO catch phrases would later be appropriated by the marketers charged with selling the Macintosh. But Engelbart's bosses at SRI weren't concerned with marketing his product.

…

''A computer for the rest of us." Now, the bulk of people-those who would drive the curve up to the mountain peak, and ring the curve-shaped bell-would be computer customers. These, he would say, echoing Doug Engelbarr's prediction of a decade before, were the knowledge workers-the target market for the Mac. "Our definition of knowledge worker is someone who sits behind a desk and plans to take information and crunch it with ideas," he'd say. Then he would mention the philosophical dream: "The philosophical dream is How can we do something that will improve people's lives?" Murray would pause and confide that, "You don't find that in any other computer company."

…

Poor Barbara Koalkin had to pry me away from the machine in order to give her canned spiel, which was sort of an overture before the opera, introducing themes I would hear developed with great intensity later on in the performance. I don't recall a word of it, really, but my notebook shows that I was dutifully jotting down key phrases, like "designed to be low-cost personal computer," "personal productivity tool for knowledge workers," and "we want everybody in the world using Mac software." Anyway, I was dazzled, a feeling that would only accelerate as the day went on. Each person I met was a young wizard bubbling with enthusiasm-I could almost feel electricity crackling as they told me their stones. Jerry Manock, the industrial designer who had literally molded the Apple II and now the Macintosh.

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by

Richard Florida

Published 9 May 2016

Boston had not offered Lycos any tax breaks or other bribes; in fact, the costs of doing business in Boston, from rents to salaries, were much higher than in Pittsburgh. Lycos was moving because the talent it needed was already in Boston. The key to urban success, I argued in my 2002 book, The Rise of the Creative Class, was to attract and retain talent, not just to draw in companies. The knowledge workers, techies, and artists and other cultural creatives who made up the creative class were locating in places that had lots of high-paying jobs—or a thick labor market; lots of other people to meet and date—what I called a thick mating market; and a vibrant quality of place, with great restaurants and cafés, a music scene, and lots of other things to do.2 By the turn of the twenty-first century, the ranks of the creative class had grown to some 40 million members, a third of the US workforce.

…

Both the conventional wisdom and economic research tell us that people do better economically in large, dense, knowledge-based cities where they earn higher wages and salaries. But when a colleague and I looked into how the members of each of the three different classes fared after paying for housing, we uncovered a startling and disturbing pattern: The advantaged knowledge workers, professionals, and media and cultural workers who made up the creative class were doing fine; their wages were not only higher in big, dense, high-tech metros, but they made more than enough to cover the costs of more expensive housing in these places. But the members of the two less advantaged classes—blue-collar workers and service workers—were sinking further behind; they actually ended up worse off in large, expensive cities and metro areas after paying for their housing.4 The implications were deeply disturbing to me.

…

In these places, mere gentrification has escalated into what some have called “plutocratization.”6 Some of their most vibrant, innovative urban neighborhoods are turning into deadened trophy districts, where the global super-rich park their money in high-end housing investments as opposed to places in which to live. It’s not just musicians, artists, and creatives who are being pushed out: growing numbers of economically advantaged knowledge workers are seeing their money eaten up by high housing prices in these cities, and they have started to fear that their own children will never be able to afford the price of entry in them. But it is the blue-collar and service workers, along with the poor and disadvantaged, who face the direst economic consequences.

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by

Erik Baker

Published 13 Jan 2025

Even many entrepreneurship enthusiasts, like Peter Drucker, did not think there was anything wrong with this reality, at least initially: while a “steady supply of enterprising men” was needed atop American firms, Drucker wrote in 1950, there was no reason in theory why “efficient big-business bureaucrats” could not thrive in the ranks beneath them. In fact, most knowledge workers were precisely those efficient big-business bureaucrats who made the firm run beneath the entrepreneurial executive: “administrators” rather than “organization builders,” in the language that University of California president Clark Kerr and his collaborators liked to use in the 1950s. The vocation of the entrepreneurial leader, then, was in a sense to redeem the bureaucratic work experience to which the typical knowledge worker was relegated by the exigencies of modern, large-scale capitalism—to make their work subjectively what it could not be objectively.6 If the complaints of the counterculture and the student movement were any indication, however, this act of transubstantiation was easier said than done.

…

“I wanted GE to run more like . . . a company filled with self-confident entrepreneurs who would face reality every day.”37 As Welch implied, there was certainly room in the entrepreneurial theory of value for “intrapreneurs” as well as CEOs—for subordinate entrepreneurs further down the corporate ladder. But if the Pinchots saw their task as persuading executives in established corporations that they could allow all knowledge workers to experience a simulacrum of entrepreneurship, a decade later the restructurers preached that entrepreneurial knowledge workers formed a special value-creating elite within the firm that ought to be cultivated at the expense of the rest of the company’s workforce. “Those who embody critical core competencies should know that their careers are tracked and guided by corporate human resource professionals,” Prahalad and Hamel urged.

…

Anticipating Jobs by nearly two decades, the commission predicted a “new technology” that would “seek to make work more meaningful rather than merely more productive,” with “machines and automated processes” performing “the routine and mechanical work” so that “human resources” could be “released and available for new activities beyond those that are required for mere subsistence.”38 For other personal computing researchers working in the Valley at roughly the same time as Jobs—such as Douglas Engelbart, the driving force behind Stanford’s Augmentation Research Center (ARC), and Alan Kay, one of the leaders of the effort to develop a personal computer at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC)—the muse of their hopes for personal computing was not just Brand but Peter Drucker, who had argued as early as the late 1960s that “the computer is a tool of liberation if used correctly.” Alan Kay would later remark, reportedly, that he envisioned the personal computer as the kind of tool that the entrepreneurial knowledge worker as described by Drucker would need to use.39 The most genuinely countercultural aspect of Jobs’s thinking was his conflation of the PC, as a putatively entrepreneurial product, and Apple, as a putatively entrepreneurial company. Jobs shared with Ralph Nader not only a penchant for hundred-hour work weeks and a dislike of furniture, but also a belief that the external mission and internal culture of an organization were inseparably entwined: the organization was either a force for enlightenment and entrepreneurship or it wasn’t.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

by

Cal Newport

Published 17 Sep 2012

Put another way, if you just show up and work hard, you’ll soon hit a performance plateau beyond which you fail to get any better. This is what happened to me with my guitar playing, to the chess players who stuck to tournament play, and to most knowledge workers who simply put in the hours: We all hit plateaus. When I first encountered the work of Ericsson and Charness, this insight startled me. It told me that in most types of work—that is, work that doesn’t have a clear training philosophy—most people are stuck. This generates an exciting implication. Let’s assume you’re a knowledge worker, which is a field without a clear training philosophy. If you can figure out how to integrate deliberate practice into your own life, you have the possibility of blowing past your peers in your value, as you’ll likely be alone in your dedication to systematically getting better.

…

To help these efforts I introduced the well-studied concept of deliberate practice, an approach to work where you deliberately stretch your abilities beyond where you’re comfortable and then receive ruthless feedback on your performance. Musicians, athletes, and chess players know all about deliberate practice. Knowledge workers, however, do not. This is great news for knowledge workers: If you can introduce this strategy into your working life you can vault past your peers in your acquisition of career capital. RULE #3 Turn Down a Promotion (Or, the Importance of Control) Chapter Eight The Dream-Job Elixir In which I argue that control over what you do, and how you do it, is one of the most powerful traits you can acquire when creating work you love.

…

This insight brought me into the world of performance science, where I encountered the concept of deliberate practice—a method for building skills by ruthlessly stretching yourself beyond where you’re comfortable. As I discovered, musicians, athletes, and chess players, among others, know all about deliberate practice, but knowledge workers do not. Most knowledge workers avoid the uncomfortable strain of deliberate practice like the plague, a reality emphasized by the typical cubicle dweller’s obsessive e-mail–checking habit—for what is this behavior if not an escape from work that’s more mentally demanding? As I researched these ideas, I became increasingly worried about the current state of my academic career.

The Long Boom: A Vision for the Coming Age of Prosperity

by

Peter Schwartz

,

Peter Leyden

and

Joel Hyatt

Published 18 Oct 2000

People have to understand how the way we work is being transformed, where this New Economy is heading, and how it will change our lives and the lives of our families. This is where the politics of the Long Boom conies in, A clear vision needs to be articulated by strong leaders to everyone, humanity at large, not just an elite of financial traders or knowledge workers. Everybody has to have a general understanding of the direction we're heading. That's the way through the anxiety and back onto the Long Boom. As if the anxiety over the turndown in the global economy weren't enough, there's the mounting anxiety over the state of our technology. As the new century approaches, the year 2000, or Y2K, problem looms large.

…

California tends to be the place to study this ideology because the people who embrace it tend to congregate in large numbers there. These people are the technologists and programmers and engineers who are building the new technologies in Silicon Valley. They are creators of new and old media based in Los Angeles. They are the entrepreneurs and knowledge workers of this New Economy. They are the business elite and global finance class chasing after the massive opportunities. They are the young people creating this new digital, wired culture. California attracts a lot of them—from all over the world. The draw of California has created the multicultural mix that has led to some of the key characteristics of the New American Ideology, such as its global mentality.

…

In that hypothetical town, everyone on the network benefits from the addition of every new member, and everyone will benefit most by having everyone wired. The same logic applies to the Internet of today. There's a strong incentive to get everyone into this emerging new network—not just the top quarter of the population, who fit the knowledge worker profile. Getting everyone on the Net is not just some philanthropic urge to be nice to all people. It makes good business sense. You want to sell your products over the Internet? The first step is getting every potential customer into that network to begin with. You want to streamlin costs by doing away with employee paperwork?

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by

Chrystia Freeland

Published 11 Oct 2012

But Drucker also, more than half a century ago, predicted the shift to what he dubbed a “knowledge economy” and, with it, the rise of the “knowledge worker.” Drucker made his name in America, but he was a product of the Viennese intellectual tradition—Joseph Schumpeter was a family friend and frequent guest during his boyhood—of looking for the big, underlying social and economic forces and trying to spot the moments when they changed. Accordingly, he saw the emerging knowledge worker as both the product and beneficiary of a profound shift in how capitalism operated. “In the knowledge society the employees—that is, knowledge workers—own the tools of production,” Drucker wrote in a 1994 essay in the Atlantic.

…

But that logic collapses in the knowledge economy: “Increasingly, the true investment in the knowledge society is not in machines and tools but in the knowledge of the knowledge worker. . . . The market researcher needs a computer. But increasingly this is the researcher’s own personal computer, and it goes along where he or she goes. . . . In the knowledge society the most probable assumption for organizations . . . is that they need knowledge workers far more than knowledge workers need them.” Here, then, is another way that some of the highly talented are catapulted into the super-elite: when it becomes possible for them to practice their profession independently.

…

But they still didn’t have the royal jelly: “They don’t have the killer instinct, they don’t want to fight, they won’t go for the jugular.” By way of evidence, he described a subordinate who had cried when he told her she had made a mistake. You can’t do that and win, he said. THREE SUPERSTARS A society in which knowledge workers dominate is under threat from a new class conflict: between the large minority of knowledge workers and the majority of people, who will make their living traditionally, either by manual work, whether skilled or unskilled, or by work in services, whether skilled or unskilled. —Peter Drucker It is probably a misfortune that . . . popular writers . . . have defended free enterprise on the ground that it regularly rewards the deserving, and it bodes ill for the future of the market order that this seems to have become the only defense of it which is understood by the general public. . . .

Smart and Gets Things Done: Joel Spolsky's Concise Guide to Finding the Best Technical Talent

by

Joel Spolsky

Published 1 Jun 2007

In either case, you should enforce the simple rule “no code without spec.” The Joel Test 163 8. Do Programmers Have Quiet Working Conditions? There are extensively documented productivity gains provided by giving knowledge workers space, quiet, and privacy. The classic software management book Peopleware3 documents these productivity benefits extensively. Here’s the trouble. We all know that knowledge workers work best by getting into “flow,” also known as being “in the zone,” where they are fully concentrated on their work and fully tuned out of their environment. They lose track of time and produce great stuff through absolute concentration.

…

All because the metrics in place just didn’t have a way to recognize different types of contributors. If it wasn’t bad enough that metrics don’t measure, they also screw up perfectly happy, productive teams. True, Some Developers Just Don’t Pull Their Weight Even though metrics simply don’t work with knowledge workers, it’s still true that there are great developers and decent developers and crappy developers. Interestingly, everybody pretty much knows who is who. You just can’t quite measure it. Fixing Suboptimal Teams 129 You still need to triage the team into three categories: 1. Great developer 2. Needs specific improvements 3.

…

If a coworker asks you a question, causing a oneminute interruption, but this knocks you out of the zone badly enough that it takes you half an hour to get productive again, your overall productivity is in serious trouble. If you’re in a noisy bullpen environment like the type that caffeinated dotcoms love to create, with marketing guys screaming on the phone next to programmers, your productivity will plunge as knowledge workers get interrupted time after time and never get into the zone. With programmers, it’s especially hard. Productivity depends on being able to juggle a lot of little details in short-term memory all at once. Any kind of interruption can cause these details to come crashing down. When you resume work, you can’t remember any of the details (like local variable names you were using, or where you were up to in implementing The Joel Test 165 that search algorithm) and you have to keep looking these things up, which slows you down a lot until you get back up to speed.

The End of Work

by

Jeremy Rifkin

Published 28 Dec 1994

Their ranks are made up largely of the new professionals, the highly trained symbolic analysts or knowledge workers who manage the new high-tech information economy. This small group, numbering fewer than 3.8 million individuals, earns as much as the entire bottom 51 percent of American wage earners, totaling more than 49.2 million. 40 In addition to the top 4 percent of American income earners who make up the elite of the knowledge sector, another 16 percent of the American workforce also consists mostly of knowledge workers. Altogether, the knowledge class, which represents 20 percent of the workforce, receives $1,755 billion a year in income, more than the other four fifths of the population combined.

…

A fair and equitable distribution of the productivity gains would require a shortening of the workweek around the world and a concerted effort by central governments to provide alternative employment in the third sector-the social economy-for those whose labor is no longer required in the marketplace. If, however, the dramatic productivity gains of the high-tech revolution are not shared, but rather used primarily to enhance corporate profit, to the exclusive benefit of stockholders, top corporate managers, and the emerging elite of high-tech knowledge workers, chances are that the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots will lead to social and political upheaval on a global scale. All around us today, we see the introduction of breathtaking new technologies capable of extraordinary feats. We have been led to believe that the marvels of modem technology would be our salvation.

…

Today, however, as all these sectors fall victim to rapid restructuring and automation, no "significant" new sector has developed to absorb the millions who are being displaced. The only new sector on the horizon is the knowledge sector, an elite group of industries and profeSSional disciplines responsible for ushering in the new high-tech automated economy of the future. The new professionals-the so-called symbolic analysts or knowledge workers-come from the fields of science, engineering, management, consultancy, teaching, marketing, media, and entertainment. While their numbers will continue to grow, they will remain small compared to the number of workers displaced by the new generation of "thinking machines." 36 THE TWO F ACE S 0 F TEe H N 0 LOG Y RETRAINING FOR WHAT?

The Power of Pull: How Small Moves, Smartly Made, Can Set Big Things in Motion

by

John Hagel Iii

and

John Seely Brown

Published 12 Apr 2010

As we will explore in a later chapter, these individuals, too, will have an increasing opportunity to become passionate about their work. Most jobs in Western corporations have been engineered (and we use this word advisedly) to become highly routinized, especially if they are not performed by “knowledge workers.” As we begin to realize that scalable efficiency cannot see us through a shift to near-constant disruption, we will begin to see that performance improvement by everyone counts, not just performance improvement for “knowledge workers.” We will begin to redefine all jobs, especially those performed at the “bottom of the institutional pyramid,” in ways that facilitate problem solving, experimentation, and tinkering.

…

The real opportunity is to rethink all aspects of the institution through the talent lens—what would the strategy, operations, and organization of the firm be like if talent development were the top priority of the firm? We’ve already talked about how institutional leaders have to focus on everyone in their organization—and not just the so-called knowledge workers. But let’s take it one step further, because there are yet more misunderstandings that arise on the topic of talent development, revealing some of the key assumptions that most executives bring to this topic. We have already noted in earlier chapters that Western executives tend to draw a firm line between “knowledge workers” and the rest of the workforce. If we are going to mobilize our entire workforce, we need to abandon this artificial distinction and recognize that everyone brings talent to the job that must be developed.

…

We will begin to redefine all jobs, especially those performed at the “bottom of the institutional pyramid,” in ways that facilitate problem solving, experimentation, and tinkering. This will foster more widespread performance improvement. Everyone, even the most unskilled worker, will be viewed as a critical problem-solver and knowledge-worker contributing to performance improvement. One need only walk through the assembly lines of a Toyota plant to see highly motivated workers who are passionate about their jobs because they can tangibly see how they are making a difference by tackling challenging work problems and contributing to greater value. Others will rightly point out that in recessionary times many people may lose their jobs no matter how passionate they might be.

The Making of a World City: London 1991 to 2021

by

Greg Clark

Published 31 Dec 2014

In London: World City, rivals such as Tokyo, New York and Berlin were analysed for their initiatives in the soft economy and their active pursuit of the benefits of agglomeration (LPAC, 1991: 26–27). The report was, it turned out, prescient in identifying inter-urban competition around human capital and quality of life. Subsequently, however, more subtle understandings of the push-and-pull factors for mobile knowledge workers and international firms have prompted more refined and targeted attraction and retention strategies. Innovative solutions have been applied to the intricacy of negotiated and collaborative governance, both between tiers of government and between public and private sectors. London now has a much wider set of practices to learn from other cities, from Singapore to Seattle, from Seoul to São Paulo.

…

Partnerships with institutional investors, sovereign wealth funds, niche fund managers and syndicated investment clubs are under negotiation in cities everywhere. Finally, the new business cycle has brought into clarity the reality of demographic change that is profoundly shaping cities’ revenue capabilities and service delivery demands. As well as increased mobility, especially of younger knowledge workers and aspirational immigrants, cities are confronted with dramatically extended life expectancies often coupled with low birth rates. As a result, urban life is for the most part becoming more and more racially, socially and economically diverse. This produces greater heterogeneity in citizenry aspirations, and the need for world cities to provide distinctive services and representation to different population segments.

…

Key developments in the global system of cities in 2015 The composite of index results has indicated since at least 2011 that Singapore and Hong Kong form part of an expanded ‘big six’ of top-tier world cities. The pair, which possess distinct self-governing capacities, have continued to record exceptional results among executives, knowledge workers and tourists in 2013 and 2014, and have moved ahead of Paris and Tokyo as financial centres. Investment from Europe, North America and the Middle East still flows heavily into these two cities, not least because of their proximity to a rapidly expanding Asian middle class. Singapore is now a world-class research hub, and the only world city consistently positively evaluated for its commuting experience, health and security outcomes.

Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams

by

Tom Demarco

and

Timothy Lister

Published 2 Jan 1987

Same with user support for another product. To the extent that knowledge workers are required to multitask, their managers need to take account of the flow requirements of the different tasks. Mixing flow and highly interruptive activities is a recipe for nothing but frustration. In particular, it assures that no reasonable telephone ethic (“Leave me alone. I’m working.”) can emerge. More important than any gimmick you introduce is a change in attitude. People must learn that it’s okay sometimes not to answer their phones, and their managers need to understand that as well. That’s the character of knowledge workers’ work: The quality of their time is important, not just its quantity.

…

There is probably no hope of changing the view that Wall Street takes of treating investment in people as an expense. But companies that play this game will suffer in the long run. The converse is also true: Companies that manage their investment sensibly will prosper in the long run. Companies of knowledge workers have to realize that it is their investment in human capital that matters most. The good ones already do. Part IV: Growing Productive Teams Think back over a particularly enjoyable work experience from your career. What was it that made the experience such a pleasure? The simplistic answer is, “Challenge.”

…

As a manager, you may have convinced yourself that you ought to be the principal coach to the team or teams that report to you. That certainly was a common model in the past, when high-tech bosses tended to be proven experts in the technologies their workers needed to master. Today, however, the typical team of knowledge workers has a mix of skills, only some of which the boss has mastered. The boss usually coaches only some of the team members. What of the others? We are increasingly convinced that the team members themselves provide most of the coaching. When you observe a well-knit team in action, you’ll see a basic hygienic act of peer-coaching that is going on all the time.

Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business

by

David J. Anderson

Published 6 Apr 2010

Take actions to get to this level of maturity incrementally—follow the Recipe for Success. Attack Sources of Variability to Improve Predictability Both the effects of variability and how to reduce it within a process are advanced topics. Reducing variability in software development requires knowledge workers to change the way they work—to learn new techniques and to change their personal behavior. All of this is hard. It is therefore not for beginners or for immature organizations. Variability results in more work-in-progress and longer lead times. This is explained more fully in chapter 19. Variability creates a greater need for slack in non-bottleneck resources in order to cope with the ebb and flow of work as its effects manifest on the flow of work through the value stream.

…

For example, if we had ten people and anticipated two people per item, the WIP limit might be five plus a few more to smooth the impact of a blockage. Perhaps eight (five plus three) would be the right limit in such circumstances. There has been some research and empirical observation to suggest that two items in progress per knowledge worker is optimal. This result is often quoted to justify multi-tasking. However, I believe that this research tends to reflect the working reality in the organizations observed. There are a lot of impediments and reasons for work to become delayed. The research does not report the organizational maturity of the organizations studied, nor does it correlate the data with any of the external issues (assignable-cause variations, discussed in chapter 19) occurring.

…

Demonstrating the Value of Managers The operations review also shows the staff what managers do and how management can add value in their lives. It also helps to train the workforce to think like managers, and to understand when to make interventions and when to stand back and leave the team to self-organize and resolve its own issues. Operations review helps to develop respect between the individual knowledge workers and their managers and between different layers of management. Growing respect builds trust, encourages collaboration, and develops the social capital of the organization. Organizational Focus Fosters Kaizen While individual project retrospectives are always useful, an organization-wide ops review fosters institutionalization of changes, improvements, and processes.

Tomorrow's Capitalist: My Search for the Soul of Business

by

Alan Murray

Published 15 Dec 2022

It was a stakeholder crisis from the start, and it highlighted a host of stakeholder issues. The pandemic put workers at risk, as they were forced to address the threat of being exposed to the virus in the workplace. And it quickly became clear the pandemic would widen the rifts that had plagued Western society in recent years—between knowledge workers and manual workers, between well-educated and less well-educated, between top-tier cities and the rest. Faced with that new reality, CEOs became even more convinced that it was time for business to step forward and play a greater role in healing society’s divides. As Emmanuel Faber, CEO of Danone, told me, “Everything we have seen during the last several months suggests companies will have even more stakeholders than before, with government stepping in, health authorities stepping in, and so on.

…

But plentiful labor is not the same as plentiful talent, and the pandemic seemed to be leading an increasing number of talent-forward companies to take an “employees first” approach. Indeed, as the economy bounced back from COVID in 2021, it became clear that there was an unprecedented battle for talent, giving knowledge workers even more power in the economic debates to come. > Demands for systemic change also intensified. The pandemic exposed flaws in business’s approach to global markets, deepening the divisions within countries and between them, and threatening supply chains. Geopolitical tension between the US and China also challenged the globalist model.

…

Most of the CEOs I talked to believed that, as in the past, technology would create new jobs even as it eliminated old ones. But they weren’t at all convinced that we had the systems in place to prepare the workforce for these new jobs at a fast enough pace. Then the pandemic hit, dealing its hardest blow to those who weren’t knowledge workers—those who worked in factories, or restaurants and retail stores, or in health care or public service, the very people who were most at risk of being left behind by technology. They didn’t have the option of simply taking their work home. Many were furloughed or lost their jobs altogether. Others dropped out of the workforce to take care of children who were not in school, or elderly parents who were most at risk of contracting the disease.

Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy

by

Jonathan Haskel

and

Stian Westlake

Published 7 Nov 2017

Drop into a coffee shop in any of the world’s major cities, and you will see peripatetic knowledge workers of the type that Handy described in the early 1990s. Look at the way people talk about the world’s most admired businesses (“What Would Google Do?”), and you will see praise for the kind of knowledge-intensive, collaborative, networked business innovation that would not have seemed out of place in 1990s California or Japan. But some things have turned out somewhat differently, either because they buck the trend of knowledge-intensive, modular businesses and the nomadic, entrepreneurial knowledge workers, or simply because they were less obvious back in 1999.

…

Modern economists, displaying an admirable flair for taking something exciting and giving it a boring name, called this trend “skills-biased technical change.” Labor market economists, particularly Martin Goos, Alan Manning, and David Autor, have suggested a twist on this story that computers are especially good at replacing routine tasks. The twist is that computers don’t replace high-paid knowledge workers, but they are not necessarily replacing the low-paid either. The reason is that many currently low-paid tasks are distinctly nonroutine: waiting on a table, cleaning a bath, or looking after the elderly. Rather, the routine tasks that computers are good at tend to be middle-income jobs, and so they “hollow out” the labor market by replacing middle-income workers (Goos and Manning 2007; Autor 2013).

…

Charles Handy’s 1994 book The Future of Work forecasted, presciently, a future of portfolio jobs and careers for the well-educated and precarious subcontracting for others. Charles Leadbeater’s Living on Thin Air, published at the height of the dot-com bubble, begins with a portrait of the author as a portfolio knowledge worker and then identifies eight characteristics that successful new economy companies would have: they would be cellular, self-managing, entrepreneurial, and integrative; they would offer their staff ownership stakes; and they would need deep reservoirs of knowledge, public legitimacy, and collaborative leadership.

Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era

by

Tony Wagner

and

Ted Dintersmith

Published 17 Aug 2015

Midway through the last century, our industrial base began to contract, and low-wage routine jobs moved offshore. As growth in manufacturing jobs stalled, millions of new white-collar jobs for “knowledge workers” (a term coined by Peter Drucker in 1959) were created, fueling the next phase of U.S. economic growth and creating a robust middle class. The economic landscape was dominated by large organizations hungry for mid-level knowledge workers to produce, refine, and manage information. To keep pace with these changes, Americans put increasing priority on education, largely by extending the number of years students spent in school.

…

The number of high school and college graduates soared. With some tweaks (such as including a college prep track in public high schools), the core of the Prussian-American education model—the transfer of basic literacy and numeracy skills and content knowledge from teachers to students—remained effective in preparing students for knowledge-worker jobs. Our education system and economy maintained their productive alliance. As we moved into the 1980s, a handful of people began voicing concerns about the state of education in the United States. They cited data questioning the international competitiveness of our students, reflected in lackluster performance on standardized tests.

…

What matters most in our increasingly innovation-driven economy is not what you know, but what you can do with what you know. The skills needed in our vastly complicated world, whether to earn a decent living or to be an active and informed citizen, are radically different from those required historically. Quite simply, the world has changed, and our schools remain stuck in time. “Knowledge workers” have become obsolete. What the world demands today are “smart creatives,” the term that Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg use to describe the kind of people Google needs to hire in their book How Google Works. In our efforts to “fix” education, we’ve taken a course of action that extirpates the creative spirit and confidence from our youth while drilling them on frivolous things, like memorizing the definition of extirpate for the SAT verbal exam.

The Trouble With Brunch: Work, Class and the Pursuit of Leisure

by

Shawn Micallef

Published 10 Jun 2014

Many of us work from home, or from actual cafés, freelance vagabonds who move from one rickety table to the next, renting the space with our coffee purchases, getting more wired as the day goes on. In January 2014, the Guardian reported that the first British branch of the Russian chain Ziferblat opened in Islington, a London neighbourhood well-known for its clusters of peripatetic knowledge workers. What makes Ziferblat (clock face in Russian) different is that it charges five pence per minute, and patrons get free snacks and coffee, and can make their own food in the kitchen. It’s essentially like renting an office on a micro, minute-by-minute basis. As permanent employment has slowly evaporated in favour of temporary and contract labour, many of us find ourselves with multiple jobs, sometimes spread over several different fields.

…

The trouble with brunch is that it could be so much more, and a closer look at brunch itself reveals its potential. The brunching class, if it embraced a little Veblen and Florida, and took a critical look at how it spends its time, and how others around it do, a collective identity across heretofore loosely related kinds of knowledge workers could be formed. What’s more, that the brunching class exists in places with radically different economic circumstances demonstrates it’s a class consciousness that could be global in scope. The Transnational Buenos Aires Brunch It was nearly two o’clock on a Sunday afternoon and we were walking the near-deserted streets of Buenos Aires looking for a very particular brunch spot.

…

A related reshaping of the tectonic plates of class are those knowledge- and creative-class workers who don’t identify with the traditional working class, even if their pay and lack of job security is commensurate with older forms of working-class life (Dickens’ famous Bob Cratchit, though a working-class icon of the early industrial revolution, was essentially a knowledge worker on a contract job with no security, no benefits and poor pay). Taste and sensibility get in the way of seeing the commonalities among the creative and working classes. Work is work, but even if a creative earns less money than a unionized worker, class becomes a kind of ideology that limits the perception of different kinds of work, failing to allow for cross-class identity, but also limits the conversation around a development like Walmart.

Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation

by

Kevin Roose

Published 9 Mar 2021

“Nobody can do what we do.” * * * — Part of what’s confusing people about this wave of AI and automation is that the danger zone has expanded. For decades, most automation was focused on repetitive manual tasks, which were concentrated in blue-collar manufacturing jobs, and white-collar knowledge workers largely considered themselves safe. But today, many of the most promising applications of AI and machine learning are in fields like accounting, law, finance, and medicine, which involve lots of tasks like planning, prediction, and process optimization. As it turns out, these are exactly the kinds of things AI does well.

…

Some of the most automation-prone jobs, the study found, were in highly paid occupations in major metropolitan areas like San Jose, Seattle, and Salt Lake City. This is radically different from the way we normally think about AI and automation risk. And it should be a wake-up call to hyper-educated knowledge workers who have historically assumed that automation was someone else’s problem. Wall Street traders learned a hard lesson about their own replaceability many years ago, when high-frequency trading algorithms and computerized stock exchanges wiped out thousands of jobs for human traders on the exchange floors.

…

The industrial economies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries required workers who could perform repetitive tasks at a high, consistent level, and individuality, in a factory setting, could be a liability. (Henry Ford’s famous supposed lament about his workers—“Why is it every time I ask for a pair of hands, they come with a brain attached?”—echoed the feelings of many old-economy barons.) White-collar knowledge workers performed cognitive labor instead of manual labor, but they, too, often benefited from suppressing their humanity in the quest for peak performance. But as I started reporting more on AI and automation, the message I heard from experts about the modern economy was, essentially, the exact opposite.

Brave New World of Work

by

Ulrich Beck

Published 15 Jan 2000

The leading social groups of the knowledge society will be ‘knowledge workers’ – knowledge executives who know how to allocate knowledge to productive use; knowledge professionals; knowledge employees. Practically all these knowledge people will be employed in organizations. Yet unlike the employees under capitalism they own both the ‘means of production’ and the ‘tools of production’ – the former through their pension funds which are rapidly emerging in all developed countries as the only real owners, the latter because knowledge workers own their knowledge and can take it with them wherever they go.

…

Drucker, Scott Lash/John Urry and Manuel Castells – will fundamentally change not only the world of work but the very concept of work itself. The most prominent feature of this new society will be the centrality of knowledge as an economic resource. Knowledge, not work, will become the source of social wealth; and ‘knowledge workers’ who have the capacity to translate specialized knowledge into profit-producing innovations (products, technological and organizational innovations, etc.) will become the privileged group in society. The basic economic resource – the ‘means of production’ to use the economist's term – is no longer capital, nor natural resources (the economist's ‘land’), nor ‘labour’.

…