Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by

Satyajit Das

Published 15 Nov 2006

A fund manager was concerned about the view that you shouldn’t buy what you don’t understand, making the point that most investment products that are bought by everyone are not understood at some level. It appears, at best, everything is a known unknown. At worst, they are unknown unknowns. In his opinion, if you wanted to understand everything in sufficient depth then you keep money under your mattress or perhaps, if you were a little more daring, government securities, preferably short term treasury bills. Otherwise? Did you invest in known unknowns? It wasn’t clear. He seemed keen on an index. A group of known unknowns or unknown unknowns was better than a single one of the same kind. Dealers love sophisticated investors. They are easy pickings.

…

After all, the august figure of Warren Buffet said so, there was no doubt Derivatives were a known that they existed. The results of the use of known – known to be WMDs littered financial history – Barings, WMDs (weapons of Proctor & Gamble, Gibson Greeting Cards, mass destruction). Orange County, Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). A known unknown was why people dabbled with WMDs. What could they hope to gain? It was definitely a known unknown. The unknown known was also self-evident. Derivatives were a simple case of greed and fear. Clients used these instruments to make money (greed) or protect themselves from the risk of loss (fear). Frequently, they confused the two. Clients were fearful that they would miss out on the DAS_C01.QXD 5/3/07 11:45 PM Page 13 P ro l o g u e 13 promised bonanza – fear of losing out on greed.

…

We proselytized with evangelical fervour on the benefits of derivatives for hedging. The poor farmer and the unfortunate multinational mining company subject to wicked and uncontrollable market forces figured prominently in our pitches. Our audiences listened to how derivatives would save them from an awful fate. And the risk of derivatives themselves – the known unknowns, unknown knowns, unknown unknowns? Well, they were generally left for the clients to discover for themselves. The rule was caveat emptor – buyer beware. So, what was the great secret? There were a few. Derivatives are typically cash settled. This means that the farmer does not need to deliver the wheat. Instead, at the agreed delivery date a calculation is done.

Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence

by

Ajay Agrawal

,

Joshua Gans

and

Avi Goldfarb

Published 16 Apr 2018

Where Machines Are Poor at Prediction Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said: There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.9 This provides a useful structure for understanding the conditions under which prediction machines falter. First, known knowns are when we have rich data, so we know we can make good predictions. Second, known unknowns are when there is too little data, so we know that prediction will be difficult.

…

This is the sweet spot for the current generation of machine intelligence. Fraud detection, medical diagnosis, baseball players, and bail decisions all fall under this category. Known Unknowns Even the best prediction models of today (and in the near future) require large amounts of data, meaning we know our predictions will be relatively poor in situations where we do not have much data. We know that we don’t know: known unknowns. We might not have much data because some events are rare, so predicting them is challenging. US presidential elections happen only every four years, and the candidates and political environment change.

…

For example, scientists imagined the atom as a miniature solar system for decades, and it is still taught that way in many schools.11 While computer scientists are working to reduce machines’ data needs, developing techniques such as “one-shot learning” in which machines learn to predict an object well after seeing it just once, current prediction machines are not yet adequate.12 Because these are known unknowns and because humans are still better at decisions in the face of known unknowns, the people managing the machine know that such situations may arise and thus they can program the machine to call a human for help. Unknown Unknowns In order to predict, someone needs to tell a machine what is worth predicting. If something has never happened before, a machine cannot predict it (at least without a human’s careful judgment to provide a useful analogy that allows the machine to predict using information about something else).

What We Cannot Know: Explorations at the Edge of Knowledge

by

Marcus Du Sautoy

Published 18 May 2016

Source ISBN: 9780007576661 Ebook Edition © May 2016 ISBN: 9780007576579 Version: 2016-04-21 Dedication To my parents, who started me on my journey to the edges of knowledge CONTENTS Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Edge Zero: The Known Unknowns First Edge: The Casino Dice Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Second Edge: The Cello Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Third Edge: The Pot of Uranium Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Fourth Edge: The Cut-Out Universe Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Fifth Edge: The Wristwatch Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Sixth Edge: The Chatbot App Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Seventh Edge: The Christmas Cracker Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Further Reading Index Acknowledgements Illustration Credits Also by Marcus du Sautoy About the Publisher EDGE ZERO: The Known Unknowns Everyone by nature desires to know.

…

One of the dangers when faced with currently unanswerable problems is to give in too early to their unknowability. But if there are unanswerables, what status do they have? Can you choose from the possible answers and it won’t really matter which one you opt for? Talk of known unknowns is not reserved to the world of science. The US politician Donald Rumsfeld strayed into the philosophy of knowledge with the famous declaration: There are known knowns; there are things that we know that we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know. Rumsfeld received a lot of stick for this cryptic response to a question fired at him during a briefing at the Department of Defense about the lack of evidence connecting the government of Iraq with weapons of mass destruction.

…

For Kelvin it was relativity and quantum physics that turned out to be the unknown unknown that he was unable to conceive of. So in this book I can at best try to articulate the known unknowns and ask whether any will remain forever unknown. Are there questions that by their very nature will always be unanswerable, regardless of progress in knowledge? I have called these unknowns ‘Edges’. They represent the horizon beyond which we cannot see. My journey to the Edges of knowledge to articulate the known unknowns will pass through the known knowns that demonstrate how we have travelled beyond what we previously thought were the limits of knowledge.

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by

Gabriel Weinberg

and

Lauren McCann

Published 17 Jun 2019

Because there are reports that there is no evidence of a direct link between Baghdad and some of these terrorist organizations. Rumsfeld: Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones. The context and evasiveness of the exchange aside, the underlying model is useful in decision making.

…

When faced with a decision, you can use a handy 2 × 2 matrix (see Chapter 4) as a starting point to envision these four categories of things you know and don’t know. Knowns & Unknowns Known Unknown Known What you know you know What you know you don’t know Unkown What you don’t know you know What you don’t know you don’t know This model is particularly effective when thinking more systematically about risks, such as risks to a project’s success.

…

Each category deserves its own attention and process: Known knowns: These might be risks to someone else, but not to you since you already know how to deal with them based on your previous experience. For example, a project might require a technological solution, but you already know what that solution is and how to implement it; you just need to execute that known plan. Known unknowns: These are also known risks to the project, but because of some uncertainty, it isn’t exactly clear how they will be resolved. An example is the risk of relying on a third party: until you engage with them directly, it is unknown how they will react. You can turn some of these into known knowns by doing de-risking exercises (see Chapter 1), getting rid of the uncertainty.

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by

William Baker

and

Addison Wiggin

Published 2 Nov 2009

In this way Wall Street has inventively adapted to the threat raised by passive management, the case for which seemed airtight once the efficient market theorists were given their due. What is it about human nature that we value the present so highly, but we lose sight of the big picture? Unknown Unknowns 15 Unknown Unknowns There are known knowns. There are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we do not know we don’t know. Donald Rumsfeld, statement from Defense Department briefing, 200210 In his bestseller, The Black Swan, the financial commentator Nassim Taleb claims that investors and economists err in understanding the direction of markets because they underestimate what they do not know, a concept he names “tunneling.”

…

But it has produced a market full of capital awarded to funds based upon historical trends, which are subject to dramatic realignment, particularly in light of what may be a generational 29 Wings of Wax economic episode that may result in the realignment of trade between nations, the bankruptcy of major global entities, or even entire countries and their currencies, Iceland being the first to fall. Market participants can only seek to hedge against perceived risk, or known unknowns. When many stand on the same side of the boat in the belief that they are protected by the latest technology, the iceberg below the surface has a tendency to create a Titanic moment. The Greatest Risk To combust, a fire requires three conditions: fuel, oxygen, and heat. Derivatives and evidence-based investing are not enough to cause a financial meltdown.

…

The Russian attack upon Georgia in 2008, although initially shrugged off by financial and commodity markets as inconsequential, may embolden this former enemy and signal the restart of another Cold War. Foreign policy has thus shifted from being an “unknown unknown,” as Rumsfeld would say, to being a “known unknown.” With an intelligence service that is not hamstrung by conferring Constitutional rights to alien combatants, from rights to trials in the U.S. justice system to blocking the monitoring of phone calls between aliens on foreign soil, less would be unknown. Human intelligence, which is essential in the fight against terrorism, was decimated first by the Church Committee in 1975, the application of the Torricelli Principle (1995), and President Clinton’s Directive 35.

The Knowledge Illusion

by

Steven Sloman

Published 10 Feb 2017

Donald Rumsfeld was the U.S. secretary of defense under both presidents Gerald Ford and George W. Bush. One of his claims to fame was to distinguish different kinds of not knowing: There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know. Known unknowns can be handled. It might be hard, but at least it is clear what to prepare for. If the military knows an attack is coming but doesn’t know where or when, then they can put their reserves on notice, prepare their weaponry, and make everything as mobile as they can.

…

See also technology investment game example, 138–39 and people’s cognitive self-esteem, 136–39 search study, 137 team effect of an individual’s online research, 137–38 WebMD diagnosis study, 138–39 interpersonal relationships and causal reasoning, 57–58, 75 interviewing example of intelligence, 201 intuition vs. deliberation, 75–84 anagram example, 76–77 Aristotle, 77 chakras, 79–80 CRT (Cognitive Reflection Test), 80–84 Frederick, Shane, 80–82 passion and reason, 78–79 Plato, 78 the power of thinking as a community, 80, 200 the reflective response, 81–84, 238 inverted text example of familiarity and illusion of comprehension, 217 investment game example of the Internet and people’s sense of understanding, 138–39 Iranian attitudes about nuclear capabilities as example of sacred values, 185–86 Israeli-Palestinian conflict example of values vs. consequences arguments, 186–87 Jane Doe example of the role of the community of knowledge in science, 224–25 Janis, Irving, 173 jellyfish, sophistication of a, 42 Julie and Mark example of moral dumbfounding, 181–82 Kahan, Dan, 160 Kahneman, Daniel, 76 kayak example of long-term planning and causal reasoning, 56–57 Keil, Frank, 20–23, 21–24, 137 Kennedy, John F., 263 King, Martin Luther, Jr., 195–97, 214 knowledge accessibility of, 13–14, 123–25, 127–28 author’s daughters example, 261–62, 264–65 calibrated, being, 262 collaboration, 14, 17, 115–16 community of, 80, 200, 206–14, 221, 223–27 compatibility of different group members’, 126 cumulative culture, 117–18 curse of, 128 estimating, 24–26 false information, spreading, 231–32 flying as an example of shared knowledge, 18 geology article example, 123–24 groupthink, 173–75 hive mind collaboration, 5–6, 128, 244–46 illusion, 127–29, 262–65 interdependence of, 226 “known unknowns,” 32, 173 lack of depth, individuals’, 9–10, 73–74, 127, 163–64, 257–58 medical information example, 125 placeholders, 125–26 and skills, 258 Sphinx example, 125–26 understanding science and technology, 156–59, 162–64, 169–70, 221–28 “unknown unknowns,” 32–33 “known unknowns,” 32, 173 Kurzweil, Ray, 132 Landauer, Thomas, 24–26 language, 113–14 lateral inhibition, 43–45 Lawson, Rebecca, 23–24 leaders, qualities of strong, 192–93 learning to accept what you don’t know, 220–21, 223–24 communal, 228–31 expressing desire to learn that which is unknown, 221 one’s place within a community of knowledge, 220–21 lessons for making good decisions gathering information to increase understanding, 252–53 just-in-time education, 251–52 reducing complexity, 250 simple decision rules, 250–51 libertarian paternalism, 247–49 food choices example, 248–49 nudges, behavioral, 248–49 opting out instead of opting in, 249 organ donation example, 248–49 Liersch, Michael, 235 lily pad problem from Cognitive Reflection Test, 81–82 Limulus polyphemus (horseshoe crabs), 42–45 linear vs. nonlinear change, 234–37 lithium-7, 2–3 logic affirmation of the consequent, 54–55 causal, 56 inferences, 55–56 propositional, 54–56 long-term planning and causal reasoning, 56–57 Ludd, Ned, 153–54 Luddites, 153–54 Lynch, John G., Jr., 251–52 machine intelligence.

Think Like an Engineer: Use Systematic Thinking to Solve Everyday Challenges & Unlock the Inherent Values in Them

by

Mushtak Al-Atabi

Published 26 Aug 2014

We do not want to roll out the new technology nationwide at a huge cost just to realise that correcting it is going to affect the viability of the bank. 12.3 Failure, Risk and Uncertainty Donald Rumsfeld, US secretary of defence during the US invasion of Iraq, said that there are two kinds of unknowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. Known unknowns are events for which we know their probability of happening; for example, we know how many people die of heart-related diseases each year in a certain population group. When the known unknowns are negative in consequences, they are called risk. There are data available on the probability of the success of new business ventures, such as restaurants. So anyone who wishes to open a new restaurant should know that only 10% of new restaurants survive and make money.

Everydata: The Misinformation Hidden in the Little Data You Consume Every Day

by

John H. Johnson

Published 27 Apr 2016

On February 12, 2002, Rumsfeld (former U.S. secretary of defense) appeared at a U.S. Department of Defense briefing and said: “There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” On Rumsfeld’s website (http://papers.rumsfeld.com/about/page/authors-note), he says he “first heard a variant of the phrase ‘known unknowns’ in a discussion with former NASA administrator William R. Graham, when we served together on the Ballistic Missile Threat Commission in the late 1990s.” 27.

…

And that’s okay. You don’t have to know every confidence interval of every study you read about. But you should know that they exist, what they mean, and how they influence the data you consume every day. Or, in the words of Donald Rumsfeld, you want to distinguish between “unknown unknowns” and “known unknowns.”26 Of course, media interpretation of data is a different issue from original scientific studies that may have false findings. In a paper titled “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” John Ioannidis wrote, “There is increasing concern that in modern research, false findings may be the majority or even the vast majority of published research claims.”27 As Science News put it, “if you believe what you read in the scientific literature, you shouldn’t believe what you read in the scientific literature.”28 We’re not sure about Ioannidis’s claims about the “majority” of published claims being false, but we’ve certainly seen dozens—if not hundreds—of published studies that had notable concerns regarding statistical significance.

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

by

Chris Hedges

Published 12 Jul 2009

And if the president can declare American citizens living inside the United States to be enemy combatants and order them stripped of constitutional rights, which he effectively can under this authorization, what does this mean for us? How long can we be held without charge? Without lawyers? Without access to the outside world? The specter of social unrest was raised at the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College in November 2008, in a monograph by Nathan Freier titled Known Unknowns: Unconventional “Strategic Shocks” in Defense Strategy Development. The military must be prepared, Freier warned, for a “violent, strategic dislocation inside the United States” that could be provoked by “unforeseen economic collapse,” “purposeful domestic resistance,” “pervasive public health emergencies,” or “loss of functioning political and legal order.”

…

Blair, “Far-Reaching Impact of Global Economic Crisis,” Annual Threat Assessment, Senate Armed Services Committee (March 10, 2009), 3. http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2009_hr/031009blair.pdf. 10 Quoted in James Bamford, “Big Brother Is Listening,” Atlantic (April 2006), http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200604/nsa-surveillance/4. 11 Nathan Frier, “Known Unknowns: Unconventional ‘Strategic Shocks’ in Defense Strategy Development,” U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB890.pdf. 12 George Orwell, The Collected Letters, Essays and Journalism of George Orwell. Vol, 4: In Front of Your Nose, 1945-1950.

…

Kamata, Satoshi Kane (wrestler) Kant, Immanuel Keller, Bronwen Keltner, Dacher Kenci (porn actress) Kennedy, John F. Kerbel, Jarrett Kerry, John Khomeini, Ayatollah Khosrow Ali Vaziri, Hossein (Iron Sheik) Klein, Naomi Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) schools Known Unknowns: Unconventional “Strategic Shocks” in Defense Strategy Development (Freier) Korten, David Kristy (The Swan contestant) Krypton, Roger Ku Klux Klan Kucinich, Dennis LA Weekly (newspaper) Labor unions LaFarge, Peter Lahde, Andrew Landay, Jonathan Lane, Robert Lane, Sunny Las Vegas, Nevada described porn expo in Lasch, Christopher The Last Honest Place in America (Cooper) The Last Professors: The Corporate University and the Fate of the Humanities (Donoghue) Law, John Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Layfield, John Bradshaw (JBL) Lazarus, Richard S.

First Light: Switching on Stars at the Dawn of Time

by

Emma Chapman

Published 23 Feb 2021

Radio emission escaping from microwave ovens during the magnetron shut-down phase neatly explains all the observed properties of the peryton signals.’3 Whoops. They hadn’t discovered a new astrophysical entity after all. Someone next door had just got hungry while the telescope was taking data. Anything can happen with unknown unknowns! The known unknowns We have managed to cover a lot of the known knowns and known unknowns. We have followed the many paths of the first light, whether it came from stars, black holes or galaxies. Simulations have become so advanced that we can now follow the births of individual stars in a fragmenting gas cloud, and follow whole families as they form, merge, fly out or explode.

…

Early on in my career the most I had been paid for a public lecture was a doughnut, and grateful I was for that too. 2 A £1,000 reward from the Air Ministry for anyone who could kill a sheep at a distance of 100 yards went unclaimed. 3 Always antennas, never antennae. The latter belong to an insect. 4 A petabyte is equivalent to about 2000 years worth of MP3 songs. CHAPTER ELEVEN Unknown Unknowns In science there are the known knowns (those that you already know), the known unknowns (those that you are aware of), and the unknown unknowns (those that you didn’t even see coming). The data rates of modern telescopes are torrential, and real-time searching of that data for anomalies is near impossible. But if we can store the data and then review it later, sometimes surprises pop out.

Escape From Model Land: How Mathematical Models Can Lead Us Astray and What We Can Do About It

by

Erica Thompson

Published 6 Dec 2022

The subjectivity of that second escape route may still worry you. It should. There are many ways in which our judgement, however expert, could turn out to be inadequate or simply wrong. As Donald Rumsfeld, former US secretary of defense, put it: there are ‘known unknowns’ and there are ‘unknown unknowns’. If the known knowns are things that we can model, and the known unknowns are things that we can subjectively anticipate, there will always be unknown unknowns lurking in the darkness beyond the sphere of our knowledge and experience. But how else can we account for them? By definition, we cannot infer them from the data we have, and yet we must still make decisions.

…

These are common concerns. Winsberg answers his own rhetorical questions, however, in the final paragraphs of the book itself, where he notes the possibility of abrupt and disruptive changes that are not modelled adequately and that could happen over a very short period of time. In failing to model ‘known unknowns’ like methane release or ecosystem collapse, climate modellers are indeed writing a zero-order polynomial when we know for sure that the truth is something more complex. We know what the timescale of applicability for weather models is: a few days to weeks, determined by the timescale on which we find major divergence in the range of forecasts.

Nerds on Wall Street: Math, Machines and Wired Markets

by

David J. Leinweber

Published 31 Dec 2008

However, if one makes the simplifying assumption that all events are either “scheduled” or “unanticipated,” then one concludes that optimal execution is always a game of static trading punctuated by shifts in trading strategy that adapt to material changes in price dynamics. (p. 5) This is a Ph.D.-ified version of the wisdom of two-time Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld that there are “known unknowns and unknown unknowns.” 78 Nerds on Wall Str eet Examples of known unknowns include scheduled announcements that affect particular stocks, like earnings releases or conference calls; announcements that affect groups of stocks, like housing starts; and announcements that affect broad markets, like macroeconomic data and interest rates.

…

CONTENTS Foreword by Ted Aronson Acknowledgments Introduction xi xiii xv Part One Wired Markets 1 Chapter 1: An Illustrated History of Wired Markets 5 Chapter 2: Greatest Hits of Computation in Finance 31 Financial Technology Stars; Hits and Misses; The Crackpot as Billionaire; Future Technological Stars; Mining the Deep Web; Language Technology; EDGAR; Greatest Hits, and the Mother of All Greatest Misses Chapter 3: Algorithm Wars 65 Early Algos; Algos for Alpha; Algos for the Buy Side; From Order Pad to Algos; A Scientific Approach; Job Insecurity for Traders; So Many Markets, So Little Time; Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns; Models Aren’t Markets; Robots, RoboTraders, and Traders; Markets in 2015, Focus on Risk; Playing Well with Robots and Algorithms; Seeing the Big Picture in Markets; Agents for News and Pre-News; Algorithms at the Edge Part Two Alpha as Life 89 Chapter 4: Where Does Alpha Come From?

…

Source: Robert Almgren and Neil Chriss, “Optimal Execution of Portfolio Transactions,” Journal of Risk 3, no. 2 (Winter 2000/2001). 10 Share Holdings 8 C B 6 4 A 2 0 0 1 2 3 Time Periods 77 4 5 Mathematical models of markets can become very elaborate. Game theoretic approaches to other market participants, human and machine, in the spirit of the Beautiful Mind ideas of John Nash, bring another level of insight. Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns Almgren and Chriss close with an important point about the limitations of all model-driven strategies. As part of the Algos 201 track, here is what they say about connecting algorithms to real-world events: Finally, we note that any optimal execution strategy is vulnerable to unanticipated events.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

Our ability to make the most out of uncertainty is what creates the most potential value. We should be fueled not by a desire for a quick catharsis but by intrigue. Where certainty ends, progress begins. Our obsession with certainty has another side effect. It distorts our vision through a set of funhouse mirrors called unknown knowns. Unknown Knowns On February 12, 2002, amid escalating tensions between the United States and Iraq, US secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld took the stage at a press briefing. He received a question from a reporter about whether there was any evidence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction—the basis for the subsequent American invasion.

…

A typical answer would be packaged in preapproved political stock phrases like ongoing investigation and national security. But Rumsfeld instead pulled out a rocket-science metaphor from his linguistic grab bag: “There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”16 These remarks were widely ridiculed—in part because of their controversial source—but as far as political statements go, they’re surprisingly accurate. In his autobiography, Known and Unknown, Rumsfeld acknowledges that he first heard the terms from NASA administrator William Graham.17 But Rumsfeld conspicuously omitted one category from his speech—unknown knowns.

…

Determining what to be alarmed about requires following the timeless wisdom of Yoda: “Named must your fear be before banish it you can.”72 The naming, I’ve found, must be done in writing—with paper and pencil (or pen, if you’re into technology). Ask yourself, What’s the worst-case scenario? And how likely is that scenario, given what I know? Writing down your concerns and uncertainties—what you know and what you don’t know—undresses them. Once you lift up the curtain and turn the unknown unknowns into known unknowns, you defang them. After you see your fears with their masks off, you’ll find that the feeling of uncertainty is often far worse than what you fear. You’ll also realize that in all likelihood, the things that matter most to you will still be there, no matter what happens. And don’t forget the upside.

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by

John Lanchester

Published 5 Oct 2014

Since this would obviously involve large population displacements, and probably the total breakdown of order, not just in the cities affected but all around them, this study is in effect predicting the end of life as we know it, sometime this decade. Let’s hope the Hawaii team is wrong; but for sure this counts as a “known unknown.” A third “known unknown” is that the world is likely to look more and more like a genuinely multipolar place. For a long time we lived with two superpowers, then with one; now there will be several sources of global power and influence. We haven’t had a world that looks like that for a long time, and it is likely to have many surprising features.

…

This one isn’t going away, anywhere—and that in itself is a strange and new thing, because we face the prospect of a world in which, arguably for the first time, every political dispensation, from Communist China to mixed-economy India to free-market America to the resource producers of South America to the welfare state capitalist societies of northern Europe, everybody, is for the first time, arguing about the same issue. In Beijng or Rio, Sydney or Paris, New York or London, it’s about the inequality, stupid. So where do we go from here? The two biggest “known unknowns” are those of inequality and crises in relation to resources. We simply can’t know how these issues are going to play out over the next few years, even though we can be sure that the subjects are going to be at the top of the global agenda. I think there we’re likely to see a gradually increasing distinction between the developed and the emerging worlds, in terms of their attitudes to wealth and in particular to public displays of wealth and conspicuous consumption.

What They Do With Your Money: How the Financial System Fails Us, and How to Fix It

by

Stephen Davis

,

Jon Lukomnik

and

David Pitt-Watson

Published 30 Apr 2016

But if the economic model gives a narrow view of the world, the risk model does a poor job predicting how it functions. This happens for two reasons. The first has to do with the difference between risk and uncertainty. Donald Rumsfeld, the former US defense secretary, made this distinction when he talked about “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns.”34 We might think of known unknowns as representing risk. If we throw a pair of dice, we don’t know what the outcome will be, but we know that it will be between two and twelve and that each outcome will come up a predictable percentage of times. But some outcomes cannot be predicted, even probabilistically.

…

They find that the key factors were association with US banks, the simple leverage ratio of the bank, and the fragility of its financing—that is, the likelihood that lenders will withdraw funds. They point out that the fundamental problem with Basel III is that it aims to control the wrong thing. It focuses on risk, that is, the “known unknowns” for each bank, rather than uncertainty, that is, “unknown unknowns” for the system as a whole. R. A Brealey, I. Cooper and E. Kaplanis, “International Propagation of the Credit Crisis: Implications for Bank Regulation,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 24, no. 4 (2012): 36–45. 3. Haldane, “The Dog and the Frisbee.” 4.

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by

Fredrik Erixon

and

Bjorn Weigel

Published 3 Oct 2016

In a world where a greater part of equity- and debt-holding follows such a formula, and where market and regulatory trends lead to far greater homogenization of investor behavior, the general profile of corporate ownership gradually comes to reflect broad macro trends and issues around systemic risks rather than the actual merits of a company and its future.5 So let us go back to the riddle: if no one knows who owns a company, no one knows what concerns the investors and why they have invested. It follows that no one will know if a company is following the wishes of the owners or not, or whether the interests of owners and companies are aligned. As a consequence, no one really knows whom the management serves. Do you see where this is going? It is an ownership structure based on known unknowns. That is what makes capitalism betwixt – and gray. Add to this the global linkages of dispersed ownership. The global ownership of companies forms a connecting structure resembling a spider’s web, where the ultimate ownership rests with a small number of financial companies, or spiders. In a study of global concentration of ownership, penetrating into the ownership of as many as 37 million global companies, including financial companies and investors, it turned out that only 147 firms control about 40 percent of all corporate assets.6 When this group of spiders was expanded to include 737 companies, together they were shown to control 80 percent of assets.

…

The paradox is that what is good for the individual saver is not good for economies, at least not in the long run as gray capital plays an increasing part in the total financial economy. Gray capital, then, creates a capitalist economy where ownership is based predominantly on indirect ownership, or known unknowns. It promotes ownership without capitalist characteristics, and is increasingly dependent on gray-haired people, often investing their savings like a rentier. Prospecting for capitalists: meet the owners A few years ago one of the British tabloids ran a story about what is perhaps a usual sight on London’s streets, but which nevertheless caught people’s attention.

…

They affect innovation because they compel companies to innovate in a way that pleases an increasingly risk-averse and precautionary society. They have created a permission-based culture of innovation. Regulation is not neutral between existing and future products: it places a wedge between efforts to improve on current products and putting vastly different products and services on the market. Regulation has become a known unknown – and, by extension, a disruptive force in the innovation process. Business has responded predictably, either cutting down on innovation expenditure or reallocating it in a way that fits with new regulatory demands. Complex regulation has reinforced the growth of the managerialist mentality in corporate management – and suppressed the appetite for radical innovation.

Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind

by

Susan Schneider

Published 1 Oct 2019

No book written today could accurately predict the contours of mind-design space, and the underlying philosophical mysteries may not diminish as our scientific knowledge and technological prowess increase. It pays to keep in mind two important ways in which the future is opaque. First, there are known unknowns. We cannot be certain when the use of quantum computing will be commonplace, for instance. We cannot tell whether and how certain AI-based technologies will be regulated, or whether existing AI safety measures will be effective. Nor are there easy, uncontroversial answers to the philosophical questions that we’ll be discussing in this book, I believe.

…

Nor are there easy, uncontroversial answers to the philosophical questions that we’ll be discussing in this book, I believe. But then there are the unknown unknowns—future events, such as political changes, technological innovations, or scientific breakthroughs that catch us entirely off guard. In the next chapters, we turn to one of the great known unknowns: the puzzle of conscious experience. We will appreciate how this puzzle arises in the human case, and then we will ask: How can we even recognize consciousness in beings that may be vastly intellectually different from us and may even be made of different substrates? A good place to begin is by simply appreciating the depth of the issue.

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by

Nate Silver

Published 31 Aug 2012

In medicine this is called anosognosia:20 part of the physiology of the condition prevents a patient from recognizing that they have the condition. Some Alzheimer’s patients present in this way. The predictive version of this syndrome requires us to do one of the things that goes most against our nature: admit to what we do not know. Was 9/11 a Known Unknown? [T]here are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—there are things we do not know we don’t know.—Donald Rumsfeld21 Rumsfeld’s famous line about “unknown unknowns,” delivered in a 2002 press conference in response to a reporter’s question about the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, is a corollary to Schelling’s concern about mistaking the unfamiliar for the unlikely.

…

—Donald Rumsfeld21 Rumsfeld’s famous line about “unknown unknowns,” delivered in a 2002 press conference in response to a reporter’s question about the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, is a corollary to Schelling’s concern about mistaking the unfamiliar for the unlikely. If we ask ourselves a question and can come up with an exact answer, that is a known known. If we ask ourselves a question and can’t come up with a very precise answer, that is a known unknown. An unknown unknown is when we haven’t really thought to ask the question in the first place. “They are gaps in our knowledge, but gaps that we don’t know exist,” Rumsfeld writes in his 2011 memoir.22 The concept of the unknown unknown is sometimes misunderstood. It’s common to see the term employed in formulations like this, to refer to a fairly specific (but hard-to-predict) threat: Nigeria is a good bet for a crisis in the not-too-distant future—an unknown unknown that poses the most profound implications for US and global security [emphasis added].23 This particular prophecy about the terrorist threat posed by Nigeria was rather prescient (it was written in 2006, three years before the Nigerian national Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab tried to detonate explosives hidden in his underwear while aboard a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit).

…

It’s common to see the term employed in formulations like this, to refer to a fairly specific (but hard-to-predict) threat: Nigeria is a good bet for a crisis in the not-too-distant future—an unknown unknown that poses the most profound implications for US and global security [emphasis added].23 This particular prophecy about the terrorist threat posed by Nigeria was rather prescient (it was written in 2006, three years before the Nigerian national Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab tried to detonate explosives hidden in his underwear while aboard a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit). However, it got the semantics wrong. Anytime you are able to enumerate a dangerous or unpredictable element, you are expressing a known unknown. To articulate what you don’t know is a mark of progress. Few things, as we have found, fall squarely into the binary categories of the predictable and the unpredictable. Even if you don’t know to predict something with 100 percent certainty, you may be able to come up with an estimate or a forecast of the threat.

Trees on Mars: Our Obsession With the Future

by

Hal Niedzviecki

Published 15 Mar 2015

Thus, for the Amondawa and the majority who have walked the earth since the beginning of humanity, there was only the now and the realization that the now was, in some hazy way, related to what had happened and what was almost-about-to happen which were, nevertheless, all the same thing. We lived within and for and through the present day—allowing the reality of its known unknown into our everyday lives the same way we integrated the rituals and patterns of gathering food or mourning the dead into the story we told each other, the ongoing story that made sense of how the tribe lived and survived. In this way, “people,” theorized Marshall McLuhan, “were drawn together into a tribal mesh” and partook of “the collective unconscious.”

…

There could be “a certain script of language,” speculated Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1678, “that perfectly represents the relationships between our thoughts.”15 The seventeenth-century German philosopher and mathematician Leibniz put his faith in a language of pure reason—the language that would allow us to symbolize all disagreement, all controversy, all known unknowns through the pure intractable truth of logic. He spoke of using this mathematical language to “work out by an infallible calculus, the doctrines most useful for life, that is, those of morality and metaphysics.”16 Leibniz invented calculus and even, in 1679, “imagined a digital computer in which binary numbers were represented by spherical tokens, governed by gates under mechanical control.”17 He laid the groundwork for the information-based computer revolution to come.

…

It’s a device that tells us what just happened to our brain in order to help us control what’s going to happen next in our brain. But for many of us, even those of us actively involved in pursuing future and transferring more and more of life into captured information, in some hidden part of the brain, a plate is still a circle and death is still the known unknown to be feared and placated. The old modes linger. We have not yet, and may never, end our longstanding relationship to the magic that once overshadowed almost everything in human life. The process is slow and confusing. “Man the food-gatherer reappears incongruously as information-gatherer,” remarked Marshall McLuhan in 1967.

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived

by

Adam Rutherford

Published 7 Sep 2016

When talking about this era, Birney invokes a much-maligned sentiment expressed by an unlikely accidental philosopher: Donald Rumsfeld. In February 2002, the then US Secretary of State said this about the existence (or otherwise) of weapons of mass destruction in the second Iraq War: . . . as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. Nestled deep in all that wretched inelegance is great wisdom. The range and error of the betting book showed how clearly human genetics was set in the zone of unknown unknowns until the twenty-first century.

…

We estimate based on the number and density of connections between the neurons in our skulls that the brains you and I are using right now are the most complex objects in the known universe. Yet the code that underwrites that spectacular lump of grey meat is basically the same as animals that can do none of this. The greatest achievement of the Human Genome Project was working out exactly how little we knew – known unknowns. Once you know what you need to know, the future is laid out in front of you. And so, the map was sketched, and the landscape was set out – where to explore, and what we might be hunting for. If the paucity of genes was the first great revelation of the Human Genome Project, the second was that almost all the genome is not genes at all.

…

Metaphors in science should clarify or enlighten, not obfuscate because they sound profound. To me, it is using one thing we don’t understand to explain another, and thus has no explicatory power itself. Instead it merely reinforces the mystery, as if it were not simply a scientific problem of known unknowns, but something mystical. We have no room for the mystical in science. All these bits and bobs of genetic switches, scaffold, detritus, and mystery make up almost all of the genome. The Human Genome Project wasn’t easy, and took the best part of a decade, the invention of brand new technologies, unprecedented computing power and $3 billion.

Bulletproof Problem Solving

by

Charles Conn

and

Robert McLean

Published 6 Mar 2019

In an update of “Strategy Under Uncertainty,” author Hugh Courtney gave the example of early‐stage biotech investments having Level 4 uncertainty.2 Level 5 is the nearly absolute uncertainty of events that are unpredictable with current knowledge and technology, sometimes called unknown unknowns. Uncertainty levels 1 through 4 are colorfully called “the known unknowns,” in contrast to level 5. We don't put them in a too‐hard basket. Instead we approach them recognizing and quantifying the level and type of uncertainty, and then develop approaches to move toward our desired outcomes by managing the levers that we control. The next and harder step is to identify what actions you can take to deal with a particular level of uncertainty.

…

See Independent science review Issues disaggregation, 5 prioritization, 5 J Jefferson, Thomas, 69 Johnson & Johnson (J&J), staircase/associated capability platform, 221e Judgment in Managerial Decision Making (Bazerman/Moore), 216 K Kaggle, 164–166 Kahneman, Daniel, 99, 101, 107, 123 Keeney, R., 73 Kenny, Thomas, 213 King, Abby C., 143 Kirkland, Jane, 199 Knee arthroscopy, election (question), 125e Knezevic, Bogdan, 143 Knock‐out analysis, 92–93 Known unknowns, 198 Koller, Tim, 214 Komm, Asmus, xvii L Labor market, 205e Leadership, team structure (relationship), 97–98 Lean project plans, 93, 94e Learning algorithms, 159 Leskovec, Jure, 143 Levels of uncertainty, 197–198 Levers impact, 65e profit lever tree, 23e strategies, 66 Lewis, Michael, 201 LIDAR, usage, 226 Linear regression, 159–160 Local school levy support (case study), 25–28 problem, 26 sample, 28e Logic trees, 14e, 127, 180 deductive logic trees, 58–59, 67 disaggregation, map basis, 232 inductive logic trees, 67–68 reduction, 71–73 sketching, 255 types, 51–53, 52e usage, 199–202 Logic, usage, 7 London air quality, case study, 141, 142e Longevity runway estimation, 209 sketching, 210–211 Long term.

Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know

by

P. W. Singer

and

Allan Friedman

Published 3 Jan 2014

WeMo switched the fan on Clive Thompson, “No Longer Vaporware: The Internet of Things Is Finally Talking,” Wired, December 6, 2012, http://www.wired.com/opinion/2012/12/20-12-st_thompson/. WHAT DO I REALLY NEED TO KNOW IN THE END? Donald Rumsfeld Charles M. Blow, “Knowns, Unknowns, and Unknowables,” New York Times, September 26, 2012, http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/26/blow-knowns-unknowns-and-unknowables/. GLOSSARY advanced persistent threat (APT): A cyberattack campaign with specific, targeted objectives, conducted by a coordinated team of specialized experts, combining organization, intelligence, complexity, and patience.

…

Undoubtedly, new technologies and applications will emerge that will revolutionize our conceptions, just as the explosive growth of cyberspace over the last two decades has upended much of what we knew about security. Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had a famous laugh line that explained the world as being made up of three categories: “Known knowns, there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns, that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” It may not have been the most eloquent way to say it, but he was actually right. The extent of present and future known and unknown knowns makes the world of cyberspace seem an incredibly intimidating and even scary place, both today and maybe more so tomorrow.

The Laws of Medicine: Field Notes From an Uncertain Science

by

Siddhartha Mukherjee

Published 12 Oct 2015

Some of the newly discovered mutations in cancer were truly unexpected: the genes did not control growth directly, but affected the metabolism of nutrients or chemical modifications of DNA. The transformation has been likened to the difference between measuring one point in space versus looking at an entire landscape—but it was more. Looking at cancer before genome sequencing was looking at the known unknown. With genome sequencing at hand, it was like encountering the unknown unknown. Much of the excitement around the discovery of these genes was driven by the idea that these could open new vistas for cancer treatment. If cancer cells were dependent on the mutant genes for their survival or growth—“addicted” to the mutations, as biologists liked to describe it—then targeting these addictions with specific molecules might force cancer cells to die.

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You

by

Eli Pariser

Published 11 May 2011

This is one other way that personalized filters can interfere with our ability to properly understand the world: They alter our sense of the map. More unsettling, they often remove its blank spots, transforming known unknowns into unknown ones. Traditional, unpersonalized media often offer the promise of representativeness. A newspaper editor isn’t doing his or her job properly unless to some degree the paper is representative of the news of the day. This is one of the ways one can convert an unknown unknown into a known unknown. If you leaf through the paper, dipping into some articles and skipping over most of them, you at least know there are stories, perhaps whole sections, that you passed over.

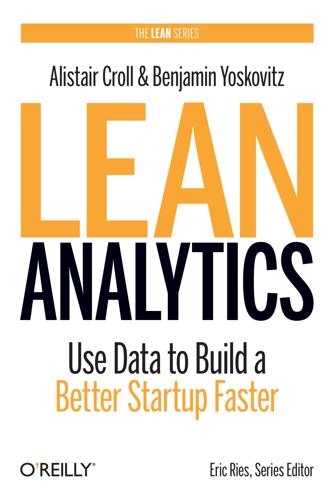

Lean Analytics: Use Data to Build a Better Startup Faster

by

Alistair Croll

and

Benjamin Yoskovitz

Published 1 Mar 2013

Exploratory Versus Reporting Metrics Avinash Kaushik, author and Digital Marketing Evangelist at Google, says former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld knew a thing or two about analytics. According to Rumsfeld: There are known knowns; there are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns; that is to say there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns—there are things we do not know, we don’t know. Figure 2-1 shows these four kinds of information. Figure 2-1. The hidden genius of Donald Rumsfeld The “known unknowns” is a reporting posture—counting money, or users, or lines of code. We know we don’t know the value of the metric, so we go find out. We may use these metrics for accounting (“How many widgets did we sell today?”)

…

jobs-be-done approach, User Engagement Johnson, Clarence “Kelly”, Span of Control and the Railroads Jones, Healy, OfficeDrop’s Key Metric: Paid Churn Just For Laughs show, Sharing with Others K Katz, Keith, Average Revenue Per User, Mobile Customer Acquisition Cost Kaushik, Avinash, Eight Vanity Metrics to Watch Out For, The Long Funnel Kennedy, Bryan, Mobile Customer Acquisition Cost key performance indicators (see KPIs (key performance indicators)) keywords driving traffic to site, A Practical Example, WineExpress Increases Revenue by 41% Per Visitor Kijiji site, What DuProprio Watches Kim, Ryan, Mobile Customer Lifetime Value KISSmetrics site, Instrumenting the Viral Pattern Klein, Laura, How to Handle User Feedback known knowns, Eight Vanity Metrics to Watch Out For known unknowns, Eight Vanity Metrics to Watch Out For KP Elements, Shopping Cart Abandonment KPIs (key performance indicators) about, What Makes a Good Metric? for engines of growth, Eric Ries’s Engines of Growth Moz case study, Moz Tracks Fewer KPIs to Increase Focus OMTM and, The Discipline of One Metric That Matters WP Engine case study, WP Engine Discovers the 2% Cancellation Rate Krawczyk, Jack, Engaged Time L lagging metrics about, What Makes a Good Metric?

Space at the Speed of Light: The History of 14 Billion Years for People Short on Time

by

Becky Smethurst

Published 1 Jun 2020

There’s a popular way of thinking about what we know and what we don’t know. First, there are the known knowns—things we know that we know: that the Earth is a sphere; that there are planets around other stars; that the universe is expanding. Then there are things that we know we don’t know—the known unknowns: we don’t know what dark matter is made of; what form matter takes in black holes; or whether direct collapse black holes are possible. Then there are the unknown unknowns—things we don’t know that we don’t know. Hindsight gives us a few examples of these, such as the discovery of radioactivity after Marie Curie’s experiments with uranium, or Benjamin Franklin’s discovery of electricity.

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by

Mervyn King

and

John Kay

Published 5 Mar 2020

His famous response was widely derided: ‘There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.’ 6 Yet Rumsfeld was saying something important. 7 The follow-up question to Rumsfeld’s musings is less well remembered than the observation that provoked it. The Defense Secretary was asked in which category – known knowns, known unknowns or unknown unknowns – did intelligence about terrorism and weapons of mass destruction fall? Rumsfeld’s response was ‘I am not going to say which it is’. 8 But no link between Iraq and the 9/11 attack has been established, and no weapons of mass destruction were found.

…

And the Xerox Corporation, which had contributed more than any other company to the innovations that made mobile computing possible, never derived commercial benefit from the inventiveness of its scientists. The pioneers of computing had built puzzle-solving machines of extraordinary power. But they had failed to understand the mysteries of business strategy as applied to their industry. From unknown unknowns to known unknowns Mysteries can sometimes be resolved by advances in knowledge. Dinosaurs dominated Earth for 130 million years (humans have done so for perhaps 100,000 years). But around 65 million years ago, an extraordinary event in our planet’s history led to the disappearance of most species, including the dinosaurs – the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction.

Spies, Lies, and Algorithms: The History and Future of American Intelligence

by

Amy B. Zegart

Published 6 Nov 2021

Some thought it was a gaffe. Others called it convoluted thinking. Some even set his comments to music.23 Here’s what he said: Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is that latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.24 But Rumsfeld wasn’t rambling.

…

For example, whether China has an aircraft carrier is a knowable fact, and it is known by U.S. intelligence agencies: China’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, was purchased from Ukraine in 1998.26 Kent described a second type of information as “things which are knowable but happen to be unknown to us,” or what Rumsfeld called the “known unknowns.” How exactly does the Liaoning maneuver at sea under various conditions? That information exists, but it requires first-hand knowledge on board the ship over long stretches of time. Chinese sailors know it, but U.S. intelligence agencies may not. Kent called the third type of information “things which are not known to anyone,” or Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns.”

…

How long, for example, will the Chinese Communist Party remain in power? Not even Chinese leader Xi Jinping has the answer. Leaders’ intentions often fall into the unknown unknown category, too—because they are not clear even to the leaders themselves.27 TABLE 4.1 Three Types of Intelligence Known Knowns Known Unknowns Unknown Unknowns Description Indisputable facts: things that are knowable and known by U.S. intelligence agencies Things that are knowable but unknown to U.S. intelligence agencies Things that are not knowable to anyone Example Existence of Chinese aircraft carrier Performance of Chinese aircraft carrier at sea Longevity of the Chinese Communist Party’s rule Difficulty Hard Harder Hardest Getting inside someone’s head is actually difficult, even for them.

Seeking SRE: Conversations About Running Production Systems at Scale

by

David N. Blank-Edelman

Published 16 Sep 2018

Yet this category persists as a source of outages today, perhaps because of a widely held practice in the industry of treating operations as a cost center, meaning that no business owner will invest it in, because it is not seen as something that can generate revenue for the business, as opposed to simply accumulate costs.15 For known-unknown problems, the path away from manual action is generally more resources or pausing normal processing in a controlled way, with some buffer of normal operation before more-detailed remediation work is required. Indeed, the conditions in which the full concentration of an on-call engineer are legitimately needed to resolve a known-unknown problem usually involve a flaw in the higher-level system behavior. An application layer problem, such as a query of death16 or resource usage that begins to grow superlinearly with input, is again amenable to programmatic ways of keeping the system running (automatically blocking queries found to be triggering restarts, graceful degradation to a different datacenter where the query is not hitting, etc.).

…

As discussed, sometimes it is cheaper, sometimes not, but it is typically a decision made by business owners that the particular code paths that recover a system should be run partially inside the brains of their staff rather than inside the CPUs of their systems. (I suppose this is externalizing your call stack with a vengeance.) In this bucket, therefore, engineers are put on call because of cost; in reality, the problem is perfectly resolvable with software. Known-unknowns Many software failures result from external action or interaction of some kind, whether change management, excessive resource usage beyond a quota limit, access control violations, or similar. In general, failures of this kind are definitely foreseeable in principle, particularly after you have some experience under your belt, even if the specific way in which (as an example) quota exhaustion comes into play is not clear in advance.

…

, Monitoring, Metrics, and KPIs Kim, Gene, SRE Patterns Loved by DevOps, SRE Patterns Loved by DevOps People Everywhere-Conclusion Kissner, Lea, The General Landscape of Privacy Engineering Klein, Matt, SRE throughout the development cycleon service meshes, The Service Mesh: Wrangler of Your Microservices?-The Future of the Service Mesh Knight Capital, Sacrifice Decisions Take Place Under Uncertainty known-knowns, software failure and, Underlying Assumptions Driving On-Call for Engineers known-unknowns, software failure and, Underlying Assumptions Driving On-Call for Engineers Kobayashi Maru, Active Learning Example: Wheel of Misfortune Koen, Brian, Approaching Operations as an Engineering Problem Kriegsspiel, Active Learning Kubrick, Stanley, The Awakening of Applied AI L Lafeldt, Mathias, Approaching Operations as an Engineering Problem Lamott, Anne, Better > Best: Set Realistic Standards for Quality large enterprises, Introducing SRE in Large Enterprises-Closing Thoughtsdefining current state, Defining Current State-To establish a roadmap for what products SRE will be responsible for, survey the current infrastructure landscape defining SRE for, Defining SRE-Defining SRE DevOps–SRE relationship, Replies identifying/educating stakeholders, Identifying and Educating Stakeholders implementing the SRE team, Implementing the SRE Team-Defining the role of supporting divisions introducing SRE into, Introducing SRE-Closing Thoughts lessons learned from process of introducing SRE, Lessons Learned preparing business case for SRE, Prepare the business case: personalize and evaluate the cost of having engineering resources responsible for reliability presenting business case for SRE, Presenting the Business Case sample implementation roadmap, Sample Implementation Roadmap launch readiness review (LRR), Pattern 2: Launch and Handoff Readiness Review at Google-Pattern 2: Launch and Handoff Readiness Review at Google leaders, as advocates for SRE, Start having conversations with leaders and champions in the organization Lean manufacturing movement, Start by Leaning on Lean-Start by Leaning on Lean learning, active (see active learning) Lee, Francis, Beyond culpability: building capacity instead of assigning blame Legeza, Vladimir, From SysAdmin to SRE in 8,963 Words, From SysAdmin to SRE in 8,963 Words-Conclusion LGBTQ+ inclusivity, Mental Disorders Are Missing from the Diversity Conversation, Benefits Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), Understanding External Dependencies Limoncelli, Thomas A.on DevOps–SRE relationship, Replies on LRR, Pattern 2: Launch and Handoff Readiness Review at Google on shared source repository, Pattern 3: Create a Shared Source Code Repository LinkedIn, Testing and staging, Uses for RUM load balancers (see scriptable load balancers) logging, Logging logical backups, Full and incremental logical backups logical isolation, Logical isolation long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, Why Now?

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by

John Elkington

Published 6 Apr 2020

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011. 4.Susan Freinkel, Plastic. 5.https://www.plasticsmakeitpossible.com/about-plastics/types-of-plastics/professor-plastics-how-many-types-of-plastics-are-there/ 6.University of Georgia, “More than 8.3 billion tons of plastics made: Most has now been discarded,” ScienceDaily, July 19, 2017. See also: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/07/170719140939.htm. 7.“The known unknowns of plastic pollution,” The Economist, March 3, 2018. See also: https://www.economist.com/international/2018/03/03/the-known-unknowns-of-plastic-pollution. 8.“WHO launches health review after microplastics found in 90 percent of bottled water,” The Guardian, 15 March 2018. See also: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/15/microplastics-found-in-more-than-90-of-bottled-water-study-says. 9.https://www.newplasticseconomy.org 10.Rob Dunn, “Science Reveals Why Calorie Counts Are All Wrong,” Scientific American, September 1, 2013.

The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World

by

Linsey McGoey

Published 14 Sep 2019

Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld pointed to the complexity of ignorance when he offered his now-infamous remark about the problem of ‘unknown unknowns’ nearly 20 years ago. Rumsfeld offered his much-quoted comment during a Department of Defense briefing in 2002, in response to being pressed about the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. ‘As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know,’ he said. ‘We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.’2 He is right. The full realm of the unknown is quite literally unknowable, and we do not know exactly how much we do not know. But Rumsfeld’s take on ignorance is also a highly limited one.

…

, 108–9 inherited privilege, 182–4 inherited wealth, 200 institutional ignorance, 33–4, 294–5 International Monetary Fund, 33–4, 137 Iraq war, 17, 31–2, 52 Jews, anti-Semitism, 79–81, 97–8 Johann-Liang, Rosemary, 273 judiciary, 199 Kant, Immanuel, 9, 308–9, 318–19 Kelsey, Frances Oldham, 254, 255–8 Kendall, Tim, 249–52, 286–7 Kerviel, Jérôme, 120 Ketek, 269–77; adverse reactions, 253–4, 271, 272–4; drug trial irregularities, 271–2, 274–7; FDA failings, 269–70, 272–3; labelling, 273; reliance on expert ignorance, 276–7; withdrawal, 253 Keynes, John Maynard, 31, 167, 170, 172–3 Khurana, Rakesh, 118–19 Kim, Jim Yong, 219–20 Kirkman-Campbell, Anne, 270–2, 274–6, 276–7 Knight, Frank, 133–4, 152 knowledge: derived from torture, 74–5; equal unknowers, 47–9; low desire for knowledge of life events, 38–9; political knowledge, 66–7, 95–6 known unknowns, 52 Koch, Charles and David, 65, 237, 238, 244 Kuttner, Stuart, 103–4 labour: Adam Smith’s wage labourers, 139; domestic labour, 125; exploitation, 129–30; weakened labour protection, 134, 137, 218–20; see also servitude; slavery laissez-faire economy, 20, 21, 126–7, 194–5, 200 The Lancet, 252, 259, 286 language, in ignorance pathways, 168, 169, 200–1 Lay, Kenneth, 235 Leeson, Nick, 120 Leveson inquiry, 109, 110–11 Lippmann, Walter, 16 List, Friedrich, 188–91 Liverpool Football Club, 88–9 Lorde, Audre, 18, 163, 317–18, 319–21, 326–8 Loveland, Douglas, 274, 275 Macdonald, John A., 26–7, 28, 313 McIntosh, Glenn, 288–90 macro-ignorance, 12–15, 169, 225–6 Madison, James, 47 Mandeville, Bernard, 248 Mankiw, Gregory, 132; Macroeconomics, 152–3, 216 marginal productivity theory, 76, 130–5, 152–3 market fundamentalism, 4–5, 6–7, 13 Mason, Paul, 43 Mazzucato, Mariana, 152, 304; The Value of Everything, 134–5 meat industry, 255 medical experiments, 72 Medicines Act (1968) (UK), 291–2 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA): antidepressant reviews, 282–6; dependence on pharmaceutical companies, 278, 284–5; GlaxoSmithKlein investigation, 252, 290, 291–2; non-prosecutions, 252, 253, 278, 291, 292; unpublished medical trials, 251–2, 286; useful unknowns, 51 Meikson Woods, Ellen, 296 Mens Rea Reform Act (US), 236–44 mental health: National Collaborating Centre, 249–50; see also antidepressants Mercer, Robert, 85–6, 87 Merck, 258–61 Merrell, 256, 257 Meyer, Eugene, 219 MHRA see Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) micro-ignorance, 12–15, 141–2, 168, 225–6 Middle East, 14–15, 68–9, 202–3 Mill, George, 159 Mill, James, 161 Mill, John Stuart, 37, 41; as an ‘unknower’, 156–7, 162, 299; Autobiography, 157–60; Britain’s peaceful global dominance, 202, 203; co-authorship with wife and stepdaughter, 7, 60–1, 153, 157–60; Considerations on Representative Government, 161; and the coolie trade, 155–6; On Liberty, 7, 60–1, 153, 158, 166; Principles of Political Economy, 158; The Subjection of Women, 202, 203; voter franchise limitations, 156 Mills, Charles, 45, 304 mining companies, 185, 222–4 Miranda, Lin-Manuel, 193 Mishra, Pankaj, 44, 304 Monod, Jacques, 6 Montesquieu, Albert de Secondat, 29 Mosholder, Andrew, 287–8 Mulcaire, Glenn, 104, 105, 106, 112–13 multinational companies, 185, 219, 222–4 Murdoch, Elisabeth, 101, 115–16, 117 Murdoch, James, 100, 102 Murdoch, Lachlan, 102 Murdoch, Rupert: ignorance of phone hacking, 19; and racist news outlets, 85–6; select committee appearance, 99, 100–1, 114; Sun office meeting, 114–15; wilful blindness, 101–2 Muttitt, Greg, 32 Nasaw, David, 207, 208, 210 Nazism, 72, 74 neoclassical theory, 130–3, 303 Nevsun Resources, 223–4 New York Times, 54–5, 87, 238 News Corporation, 115–16, 117, 119–20, 274–5; see also phone hacking News of the World: Gordon Taylor lawsuit, 105–6; phone hacking, 19, 99, 101, 102–3; use of private investigators, 103–4 Nobel prize, 60–1 Nuremberg Code, 72 Obama, Barack, 82, 91–2, 148–9 oil companies: and Iraq war, 31–2; Standard Oil, 4, 211–14 On Liberty (Mill), 7, 60–1, 153, 158, 166 Open Society (Popper), 164 Operation Motorman, 107–8 oracular power: Brennan’s ‘simulated oracle’ test, 66–7, 95–6; concept, 16, 61–2; divine providence, 67–9; financial advisors, 67; historical context, 62–4; mainstream economic theories, 217; natural and social scientists, 64–7 Orwell, George, 129, 131–2, 164, 168, 225, 309–10 Ostrich instruction, 21, 228, 231–2; see also wilful ignorance Owens, Alec, 109–11 Paine, Thomas: ‘Agrarian Justice’, 183–4; blame-shifting, 180, 307; on divine providence, 174; and elite ignorance, 18–19; on hereditary privilege, 182–4, 308; Rights of Man, 149, 183 Patnaik, Utsa, 44, 304 pharmaceutical industry: damage settlements, 261; distortion of evidence, 11–12, 75; fear of reputational damage, 263–4; fraud, 22; medical trial data, 250–2, 259–60, 262; Merck settlement, 261; presumption of innocence, 291, 292–3; regulation seen as barrier to progress, 257–8; UK’s weak regulatory system, 252–3, 278, 291, 292; useful unknowns, 51, 257; Vioxx and heart failure, 258–62; see also drug trials; drugs philanthropy, 97–8, 204, 308 phone hacking: Caryatid Operation, 112–13; and corporate ignorance, 19; Culture, Media and Sport Committee report, 99–101; Gordon Taylor lawsuit, 105–6; ICO failure to pursue journalists, 109–12; method, 104–5; News of the World, 19, 99, 101, 102–3; victims, 19, 100, 105–6, 112 Pinker, Steven: Bannon-Pinker conundrum, 34–5; Enlightenment Now, 20, 36, 37, 135–6, 142, 202, 203, 224; globalization, 175; information avoidance theories, 37–8; poverty and in-country inequality, 36–7; on wealth distribution, 147–8 Plato, 164, 296, 297 plausible deniability, 56, 120 political deceptions, 30–1 political liberalism, 41 Popper, Karl, 163–5, 297–8; Open Society, 164 positive-sum theory, 123, 136, 147 Powell, Enoch, 68 press freedom, 199 Preston, Lewis, 219 prisoners of war, 72–3 private investigators, 103–4, 107–8 Proctor, Robert, 11 The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, 79–81 Prozac, 280–1, 289, 290 Pulquero, Ramiro Obrajero, 272 Puri, Poonam, 222–3, 304 race realism, 48 racial exploitation, 304 racism, 45, 48, 84–7, 319 Rampell, Catherine, 171, 217 rational ignorance, 46–7 Rawls, John, ‘veil of ignorance’, 8–9, 46 Reagan, Ronald, 68 reckless ignorance, 54–6, 235, 304 regulation: Adam Smith legacy, 20–1, 121, 126–7, 136–7, 140–1; anti-regulation stance, 246–8, 258, 303, 307; Hayek’s disdain, 248, 301, 303; pharmaceutical industry, 252–3, 257–8, 278, 291, 292; Tocqueville’s recommendations, 20–1, 197–200, 301 rent, 128 rent-seeking, 127–8, 131, 132 Rhodes, Cecil, 313 Ricardo, David, 186–7 Robbins, Lionel, 146 Robins, Nick, 180–1 Robinson, Joan, 133, 135, 147, 152 Rockefeller, John D.: belief in self-made success, 205, 214; beneficiary of laissez-faire practices, 205–6; deceitful opposition to anti-monopoly legislation, 4; master of ignorance, 20; new cooperation principle, 215; philanthropy, 204; secretive railroad deals, 211–13; South Improvement Company cartel, 213; Standard Oil, 4, 211–14; strategic ignorance of business takeovers, 213–14 Roosevelt, Franklin D., 196 Rosenfeld, Sophia, 58 Ross, David, 269–70, 272–3 Rumsfeld, Donald, 52 Samuelson, Paul, 134, 152 sanctioned ignorance, 40–2 Sand, George, 166–7, 324–6 Sanofi-Aventis, 269–77 Sarch, Alexander, 231–2, 233–5, 304 Sartre, Jean-Paul, 293–4 Schiebinger, Londa, 11 Schwartz, Anna, 54–5, 59–61 science, 8, 64–7 scientific racism, 48, 319 Scotland Yard, 112–14 Scott, Tom, 207, 212 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), 53–4 self-interest, 125–6, 126, 136, 139–40 Seroxat, 250–2, 282 servitude, 41–2, 44, 155–6 Shapiro, Aaron, 79 shared prosperity theory, 123, 136, 147 Sherman, Rachel, 117–18 Shine lawsuit, 115–16, 117 Simons, Henry, 246 Simpson, Jeffrey, 28 Sinclair, Niigaanwewidam James, 27 Sinclair, Upton, The Jungle, 255 slavery, 43–4, 205; see also servitude Smarsh, Sarah, 84 smarts see strong/smart groups Smith, Adam, 9; Britain a nation of shopkeepers, 192; criticism of monopoly protections, 127–9; criticisms of merchants, 247, 320; economic classes of society, 138–40, 143; and economic inequality, 136; on government regulation, 20–1, 121, 126–7, 136–7, 140–1; his mother’s influence, 125; inevitability of conflict, 186; misrepresentation of his ideas, 142–6, 310–12; on relative poverty, 142–3; on self-interest, 126, 136; strategic and wilful ignorance of, 122–3; tiered justice system, 121; timing and motives for helping the poor, 245; trade protectionism, 186, 190–1; on wealth distribution, 142–4, 191; Wealth of Nations, 6–7, 121, 125–6, 136, 169, 189, 245; Wealth of Nations abridged versions, 144–6 Smith, David, 109–10 snowmobile fallacy, 241–3 social silence, 53 Société Générale, 120 Socrates, 45, 63 Somin, Ilya, 94–5, 96 Sorel, Georges, 17 Soviet Union, uncomfortable facts, 5, 13 Spivak, Gayatri, 40–1 SSRI drugs see antidepressants Standard Oil, 4, 211–14 Steinzor, Rena, 244–5 Stewart, Maria W., 130–1 Stigler, George, 133, 246–7, 248 strategic ignorance: autocratic exploitation, 69–71; business practices, 20, 205; Carnegie, 208–10; corporate anonymity, 45–6; definition, 3; of drone strikes, 91–2; economic theory, 122–3; emancipatory nature, 315–17; exposure efforts treated as inexcusable, 269–70; Ford, 79–81, 98; MHRA’s non-prosecution record, 291–2, 293–4; and political networks, 22; Rockefeller, 213–14 strong/smart groups, 16–17, 69–71, 77, 173–4, 312–13 student loans, 185 Suez crisis, 31 suicide rates, 307 Sun, 114–15 Sutherland, Kathryn, 145–6, 159 Syll, Lars, 187 Symons, Baroness, 32 taxation, Paine’s proposals, 184, 308 Taylor, Gordon, 105–6 Taylor, Harriet, 7, 60–1, 153, 157–60, 166, 299 Taylor, Helen, 157–60 Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta, 68 Teicher, Martin, 280 Temple, Robert, 287–8 Tett, Gillian, 53 Thalidomide, 254, 256–8 think tanks, 65 Thomas, Richard, 110, 111 Tillerson, Rex, 214 tobacco industry, 51 Tocqueville, Alexis de: Democracy in America, 197–200, 309, 322–3; and divine providence, 322–4; French workers, 325–6; government regulation of industry, 20–1, 197–200, 301; prejudice against women, 166–7, 324–6 torture, 72–5 trade: free trade, 17–13, 57, 200–1; mercantilism, 169–70, 171; protectionism, 186, 188, 190–1; Ricardo’s comparative advantage theory, 186–8; US policy, 171, 188, 190, 217 Trefgarne, George, 179–80 Trump, Donald: class myths of voter support, 81–4, 162, 163; elite ignorance, 90–1, 93–4; on history, 314; on Obama, 82, 148–9; presidential election, 19; selective use of facts, 92–4; on torture, 73–4; and truth, 17; wealthy backers, 83–4 truth, liberating potential, 9–10 United Kingdom: male enfranchisement, 42; market interventionism, 43–4; military interventions, 14–15; Suez crisis, 31; trade policies, 44, 57, 186, 190–1; weak regulation of pharmaceutical companies, 252–3, 278, 291–2 United States: conscription, 14–15; drone strikes, 91–2; in-country inequality, 14–15, 36–7; labour oppression, 129–30; laissez-faire policies, 194–5; military interventions, 14–15, 68–9, 185; New Deal, 196; origins myths, 169; suicide rates, 307; trade policies, 171, 188, 190, 217; War Crimes Act (1996), 73; workplace deaths, 219–20 United States Department of Justice, 102, 238, 252, 261 Unser, Bobby, 242–3 unwitting ignorance, 42, 122–3 useful unknowns, 51–6, 257, 277 utilitarianism, 8, 155 ‘veil of ignorance’, 8–9, 46 Viner, Jacob, 300, 302–3 Vinson and Elkins, 235 Vioxx, 258–62 von Eschenbach, Andrew, 273 voter ignorance: Brexit, 82–3, 89–90, 162; collective, shared problem, 243–4; definition, 94; justification for disenfranchisement, 70, 156, 174; political knowledge test, 66–7, 95–6; solutions, 94–5; Trump election, 19, 162; see also democracy, and disenfranchisement War Crimes Act (1996) (US), 73 Washington Consensus, 34 Washington Post, 89, 171, 217, 257 Watkins, Sherron, 235 Watson, Mathew, 187, 188 wealth: evidence of intelligence, 77, 81; financial oligarchy, 65; ignorance and inherited wealth, 139; inherited wealth, 117–18; and morality, 162–3; and racism, 84–7; US voter support for Trump, 83–4, 162, 163 wealth inequality: effect on social wellbeing, 135, 147; God’s will, 75–7; growth, 137; in-country inequality, 36–7; India-England, 129; legitimisation, 75–6; as natural law, 71; relative poverty, 143 Wealth of Nations (Smith), 6–7, 121, 125–6, 136, 169, 189; abridged versions, 144–6 Weber, Max The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 67 welfare systems, 185–6 wellbeing, and inequality, 135, 147 whistle-blowers, 40, 262–3 White, William Allen, 81, 97, 111–12 white-collar crime, Mens Rea Reform Act, 236–44 Whittam Smith, Andreas, 102 Whittamore, Steve, 107–8, 109, 110 wilful ignorance: definition, 21–2, 228–9; difficult to prove, 22; Enron, 21–2; equal culpability thesis, 233–5; financial law, 239–40; first court appearances, 227–8; Grenfell Tower fire, 24–6; ‘ignorance doesn’t excuse’ principle, 231–3, 239–40; News International, 274–5; and reckless ignorance, 235; Rupert Murdoch, 101–2; suspected fraud Ketek trials fraud, 271–2, 274–7 Williams, Zoe, 90 Williamson, Kevin, 83 Wollstonecraft, Mary, 20–1, 163, 317; economic fairness, 122; family background and social norms, 268, 269; legacy, 151–2; on mixed education, 312; ‘Rights of Men’ rebuttal of Burke, 149, 150–1 women: domestic violence, 59; ignorance of co-authorship, 7, 60–1; minority women, 59 Woods, Kent, 285–6, 290–1, 292 workplace health and safety, 217, 218–19, 238 World Bank: disputed assumption of neutrality, 221–2; Employing Workers Indicator, 225; institutional ignorance, 33–4; presidents, 219–20; weakened labour protection, 137, 218–20 Zinn, Howard, 196

Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 18 Jan 2018