large language model

description: language model built with large amounts of texts

45 results

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by

Parmy Olson

Google was using it to better understand text. What if OpenAI used it to generate text? Sutskever talked to a young researcher at OpenAI named Alec Radford, who’d been experimenting with large language models. Although OpenAI is best known today for ChatGPT, back in 2017 it was still throwing spaghetti on the wall to see what would stick, and Radford was one of only a handful of people at OpenAI looking at the technology that powered chatbots. Large language models themselves were still a joke. Their responses were mostly scripted and they’d often make wacky mistakes. Radford, who wore glasses and had an overgrown mop of reddish-blond hair that made him look like a high schooler, was eager to improve on all the previous academic efforts that tried to make computers better at talking and listening, but he was an engineer at heart and wanted a quicker route to progress.

…

It’s why three tech giants—Amazon, Microsoft, and Google—have a stranglehold on the cloud business. It became clear to Microsoft’s CEO that OpenAI’s work on large language models could be more lucrative than the research carried out by his own AI scientists, who seemed to have lost their focus after the Tay disaster. Nadella agreed to make a $1 billion investment in OpenAI. He wasn’t just backing its research but also planting Microsoft at the forefront of the AI revolution. In return, Microsoft was getting priority access to OpenAI’s technology. Inside OpenAI, as Sutskever and Radford’s work on large language models became a bigger focus at the company and their latest iteration became more capable, the San Francisco scientists started to wonder if it was becoming too capable.

…

Bender’s tweets were important, because that’s how Timnit Gebru eventually found her. It was late in the summer of 2021 and Gebru was itching to work on a new research paper about large language models, something that could sum up all their risks. After rummaging around online for such a paper, she realized none existed. The only thing she could find was Bender’s tweets. Gebru sent Bender a direct message on Twitter. Had the linguist written anything about the ethical problems with large language models? Inside Google, Gebru and Mitchell had become demoralized by signs that their bosses didn’t care about the risks of language models. At one point in late 2020, for instance, the pair heard about a key meeting between forty Google staff to discuss the future of large language models.

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI

by

Ethan Mollick

Published 2 Apr 2024

Shen et al., “ ‘Do Anything Now’: Characterizing and Evaluating In-the-Wild Jailbreak Prompts on Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint (2023), arXiv:2308.03825. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT demonstrates how easily LLMs can be exploited: J. Hazell, “Large Language Models Can Be Used to Effectively Scale Spear Phishing Campaigns,” arXiv preprint (2023), arXiv:2305.06972. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT an LLM, connected to lab equipment: D. A. Boiko, R. MacKnight, and G. Gomes, “Emergent Autonomous Scientific Research Capabilities of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint (2023), arXiv:2304.05332. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Chapter 3: Four Rules for Co-Intelligence I and my coauthors call the Jagged Frontier: F.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT They even seem to respond to emotional manipulation: C. Li, J. Wang, K. Zhu, Y. Zhang, W. Hou, J. Lian, and X. Xie, “Emotionprompt: Leveraging Psychology for Large Language Models Enhancement via Emotional Stimulus,” arXiv preprint arXiv: 2307.11760 (2023). GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT They are, in short, suggestible and even gullible: J. Xie et al., “Adaptive Chameleon or Stubborn Sloth: Unraveling the Behavior of Large Language Models in Knowledge Conflicts,” arXiv preprint (2023), arXiv:2305.13300. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT asking the AI to conform to different personas: L. Boussioux et al., “The Crowdless Future?

…

cmpid=BBD032923_MKT&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_term=230329&utm_campaign=markets#xj4y7vzkg. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT chain-of-thought prompting: J. Wei et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022): 24824–37. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “Take a deep breath”: C. Yang et al., “Large Language Models as Optimizers,” arXiv preprint (2023), arXiv:2309.03409. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT A good lecture: D. T. Willingham, Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning Is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2023).

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by

Karen Hao

Published 19 May 2025

She emailed Dean with her concerns and proposed to investigate the ethical implications of large language models through her team’s research. Dean was supportive. In a glowing annual performance review he would write for her later that year, he encouraged her to work with other teams across Google to make large language models “consistent with our AI Principles.” In September 2020, Gebru also sent a direct message on Twitter to Emily M. Bender, a computational linguistics professor at the University of Washington, whose tweets about language, understanding, and meaning had caught her attention. Had Bender written a paper about the ethics of large language models? Gebru asked.

…

In the same month, Derek Chauvin, a police officer in Minneapolis, murdered George Floyd, a forty-six-year-old Black man, setting off massive Black Lives Matter protests around the country and the rest of the world. The team was also concerned about the impending US presidential election. But rumors began to spread within OpenAI that Google could soon release its own large language model. The possibility was plausible. Google had published research at the start of the year about a new chatbot called Meena, built on a large language model with 1.7 times more parameters than GPT-2. The company could very well be working on scaling that model to roughly the size of GPT-3. The rumors sealed the deal for the API launch: If a model just as large would soon exist in the world, Safety felt less of a reason to hold back GPT-3.

…

Shortly after joining DeepMind in October 2019, Irving had circulated a memo he had brought with him from OpenAI, arguing for the pure language hypothesis and the benefits of scaling large language models. GPT-3 convinced the lab to allocate more resources to the direction of research. After ChatGPT, panicked Google executives would merge the efforts at DeepMind and Google Brain under a new centralized Google DeepMind to advance and launch what would become Gemini. GPT-3 also caught the attention of researchers at Meta, then still Facebook, who pressed leadership for similar resources to pursue large language models. But executives weren’t interested, leaving the researchers to cobble together their own compute under their own initiative.

These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means

by

Christopher Summerfield

Published 11 Mar 2025

.: The Linguistics Wars, 57–8 Hassabis, Demis, 347 Hayek, Friedrich, 307 Hayman, Kaylin, 345 Heaven’s Gate, 217–18 Hebbian learning, 37 Her, 341 hierarchies (nested structures), 75 high-frequency trading algorithms (HFTs), 327–8 Hinton, Geoffrey, 6, 92, 335, 346 hippocampus, 128–9, 138, 254, 255, 256, 334 hippocampus minor, 128–9, 138, 334 Holocaust, 186–7, 192, 234 HotpotQA, 269 Hugging Face, 213 Human Memome Project, 28 Humboldt, Wilhelm von, 63, 64, 151 Hume, David, 16, 38 Huxley, Thomas, 129, 136 I illocutionary acts, 218 in-context learning, 159, 163, 164, 268, 291, 308 Indian National Congress, 207 inequality, 143–5, 336–7 Inflection AI, 252 innovation, stages of, 243–4, 297 Inquisition, 138, 143 Instagram, 39, 249 InstructGPT, 188, 190, 204–5, 211 instrumental AI, 292 instrumental gap, 297–301, 330, 334 instrumentality, 246, 247, 267, 330, 332 intentionality, 131–6, 150–51, 215, 237 internet, 3, 5, 7, 134, 170–71, 182–3, 194, 203, 204, 215, 243–6, 249, 280, 282, 300, 309, 321, 325, 338 Internet Watch Foundation, 344–5 Irving, David, 186 J jailbreak, 291–2 Jelinek, Fred, 84, 85 Johansson, Scarlett, 341 Jonze, Spike, 341 Jumper, John, 347 Just Imagine, 241 K Kaczynski, David, 79 Kaczynski, Ted, 79–80 Keller, Helen, 174–5 killer robots, 314–15 knowledge, 119–78 brain, computer as metaphor for, 144–7 ‘category error’, LLM reasoning as, 156 collective sum of human, 11–13 curiosity and, 152 defining, 131–5, 277 empiricists and, see empiricists humans as sole generators of, 2–5, 45–7 intentionality and, 131–5 ‘knowing’ the facts that it generates, possibility of LLM, 119–78 knowledge cut off, 289–90 landmark problem, transformer learning and, 164–9 learning and, see learning LLM knowledge, rapid growth of, 6–8, 14 LLM mistakes and, 139–42 multimodal LLMs and, 177 National Library of Thailand thought experiment and, 171–2, 174 origins of, 15, 16–17 planning and, 142 prediction and, 154–62 rationalists and, see rationalists reasoning and, 72 semantic knowledge, 89–96 sensory data and, 173–5, 177 statistical models, neural networks as merely, 148–53 thinking and, see thinking understanding and, 46 Walter Mitty and, 170–71 Koko (infant lowland gorilla), 60–61, 66, 67 Korsakoff syndrome, 194–5 Kubrick, Stanley, 1, 47 Kuyda, Eugenia, 227 L labour market, 335–6 Lamarckianism, 115–16 LaMDA, 121–5, 135, 148, 229, 284 landmark problem, transformer learning and, 164–9 language, 57–117 bag of words model and, 80–81 biases in, 8 big data, modelling statistics of and, 84–5 Chomskyan linguistics, see Chomsky, Noam company of words, prediction and, 82–4 conditionals (IF-THEN rules), 75, 168 cryptophasia and, 58 defined, 4, 59, 60–68 ELIZA and, 70–72 ENGROB and, 75–6 evidentiary basis, meaning of language and, 170–71 feature vector and, 91–3, 106, 108, 112, 164 Firth and, 81–2 formal semantics, 200–201 games, 200–206 generalized transformations, 73–4 generation of, 81–4, 113 grammar, see grammar great apes and, 60–68, 113 hierarchies (nested structures), 75 in-context learning and, 164–9 ‘infinite use of finite means’, 63, 151 ‘language acquisition device’, 67, 113 learning in children and LLMs, 113–16 linguistic forensics, 79–81 meaning and, 69–70 n-grams, 83–4, 87–9, 92, 102, 112 natural language processing (NLP), see natural language processing (NLP) origins of, 58, 232 perplexity and, 84–5, 92, 126, 134, 166 phrase structure grammar, 73–4, 77, 81, 141 ‘poverty of the stimulus’ argument, 67, 113 prediction and, 96–103 programming/formal, 24–7, 30, 31, 53, 73, 75, 78 recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and, 98–101, 103, 105, 106, 108 recursion, property of, 73–4, 75 semantic memory, 88–9, 92, 95, 114, 279 sensory signals, and, 114 sentences, see sentences sequence-to-sequence (or seq2seq) networks and, 98–102, 104–6, 110, 112, 116 SHRDLU and, 76–8 social factors and, 114–15 statistical patterns in, 79–86 superpower of humans, 57–8 syntax, see syntax transformer and predicting, 103, 104–11 translation, 42, 47, 49–50, 57, 101, 202, 204, 283, 284, 301 uniqueness to humans, 67 Lanius, 314–15 large language models (or LLMs) cognition, resemblance to human, 332–3 current best-known, 5–6, see also individual large language model name ethics/safety fine-tuning and training, 179–238 future of, 239–338 origins of, history of NLP research and, 58–117 term, 5 think, ability to, 119–78 See also individual area, component and name of large language model Lascaux cave, south of France, 154 learning Advisor 1 (habit-based learning system), 156–60, 167, 268 Advisor 2 (goal-based learning system), 156–8, 160, 167, 268–9 brain and, 36–8 continual learning, 253 deep learning, see deep learning in-context learning, 159, 163, 164, 268, 291, 308 knowledge and, 18, 19 language, see language machine learning, 49, 90–91, 112, 152, 188, 190, 262, 267, 287, 305, 322 meta-learning (learning to learn), 158–61 one-shot learning, 253–4 prediction and, 154–62 reinforcement learning (RL), 188, 190, 192, 251, 258, 267, 305, 322 reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), 188, 189–91, 192, 251, 257, 267 trial-and-error learning, 158–61, 268 Leibniz, Gottfried, 19–21, 24–5, 28, 29, 30, 47 Lemoine, Blake, 121–4, 129, 133–4, 135, 229, 284 Lenat, Douglas, 28, 29 LIAR dataset, 197–8, 198n Lighthill, Sir James, 77 LLaMA, 213, 251 LLaMA-2, 317–18 Locke, John, 16, 38 logic, first-order/predicate, 24–31, 75, 77, 168–9 logical positivism, 25, 35 logos, 16 London Tube map, 278–80 loneliness, chatbots and, 229 Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM), 99, 116 longtermism, 312, 313 Luria, Alexander, 176 M machine learning, 49, 90–91, 112, 152, 188, 190, 262, 267, 287, 305, 322 Making of a Fly, The, 330 manipulation, 20, 84, 218, 220, 222, 236, 259, 261, 262, 264, 324 Marcus, G.: ‘The Next Decade in AI’, 51 Mata, Roberto, 194, 196 McCulloch, Warren, 35; ‘A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity’, 35–6, 37, 39 memory computer storage, 22, 28, 30, 76 continual learning and, 253 Korsakoff syndrome and, 194–5 LaMDA and, 124 limited memory of present-day LLMs, 250, 254–6, 257, 333, 334, 338 Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM), 99, 116 one-shot learning and, 253–4 RNNs and, 98 semantic memory, 88–9, 92, 95, 114, 279 short-term memory, 98, 99, 116 Met Office, 96, 105, 290 Meta, 213, 221, 261, 311, 317 meta-learning, 158, 159, 160–61, 268, 270 Metasploit, 319 Metropolis, 220 Mettrie, Julien Offray de La: L’Homme Machine, 32 Micro-Planner, 77 military AI, 313, 314–16 mind blank slate, infant mind as, 16, 38, 42 brain and, 32–3, 129–30 defined/term, 130 mechanical models of, 143–4 problem of other minds, 123 MiniWoB++, 293–4 Minsky, Marvin, 1–2, 17, 19, 38, 43 misinformation, 8, 51, 145, 181–4, 197, 198, 219, 223, 232, 263, 337 mode collapse, 212 Moore’s Law, 29, 305 Mosteller, Frederick, 80–81 move, 37, 4, 5 multi-hop reasoning problems, 269 multimodal AI, 177, 230, 242 Musk, Elon, 210, 307, 321 N n-grams, 83–4, 85n, 87–9, 92, 102, 112 National Library of Thailand thought experiment, 171–2, 174 natural language processing (NLP), 50, 310 Chomskyan linguistics and, see Chomsky, Noam crosswords and, 276 defined, 58–9 ELIZA and evolution of, 60, 70–72, 78, 81 ENGROB and evolution of, 75–6 evolution of, 58–117 language, definition of and, 4, 59, 60–68 n-grams and, see n-grams perplexity and, 84–5, 92, 126, 134, 166 recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and, 98–101, 103, 105, 106, 108 semantic memory and, 88–9, 92, 95, 114, 279 sequence-to-sequence (or seq2seq) network, 98–102, 104–6, 110, 112, 116 SHRDLU and evolution of, 76–8 statistical modelling in, 79–86, 101, 110, 112, 308 transformer and, 104–111 natural selection, theory of, 128, 164 Neam Chimpsky (Nim), 65–7, 72, 78, 113 neocortex, 116, 256 Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 104 Neural Machine Translation (NMT), 49, 50, 98n neural network, 3–4, 19, 31, 45, 254, 256, 267, 274, 279, 283, 332 consciousness and, 122, 123–6, 131, 234, 260 deep neural network, see deep neural network double descent and, 49 feature vector and, 92–3 function of, 116 generalization and, 43–4 language models based on neural networks dominate NLP, 97–8 LLMs, see large language models (LLMs) Neural Machine Translation (NMT) and, 49–50 novelty and, 41–2 origins of, 32–9, 47 overfitting, 48, 49 recurrent neural networks (RNNs), 98–101, 103, 105, 106, 108 semantic memory and, 90–95 training from human evaluators, 51–2 transformer and, see transformer Turing Test and, 59 See also individual neural network name neurons, 31, 33, 34, 35–8, 47, 125, 130, 144, 147, 161–2, 254, 299 Newell, Alan, 26, 27, 29, 53, 274 NotebookLM, 342–3 ‘nudify’ sites, 345 O Occam’s Razor, 48, 49 Ochs, Nola, 253 ontology, 29 OpenAI, 1, 5, 51, 122, 162, 187, 187n, 188, 208, 210, 215, 222–3, 235, 237, 242, 245, 251, 257, 262, 285, 290, 295–6, 340, 341, 342 open-ended problems/environments, 273–4, 283, 288, 297, 298, 299, 320, 333 open-source LLMs, 212–13, 290, 294–5, 317 opinions, LLMs and, 132, 134, 207–16, 237 Ord, Toby: The Precipice, 312 overfitting, 48, 49 Owen, Richard, 128, 138, 334 P Page, Larry, 76, 321 Palantir, 315 Paley, William, 163, 164 Palm 540B, 293 Pandas, 284 Patron Saints of Techno-Optimism, 306–7 Pause AI letter, 310–11 perceptron, 37–9, 42, 43, 47 perlocutionary acts, 218–19, 224 perplexity, 84–5, 92, 126, 134, 166 personal assistant (PA), 7, 227–8, 243, 246–7, 251, 263, 272, 292, 295, 297, 300, 301, 332, 334, 335, 342–3 personalization, 245–64, 329–30, 332, 334, 335 perils of, 259–64 persuasion, rational, 218–24, 236 phenomenal states, 122, 123 phone, 6, 11, 39, 41, 47, 52–3, 81, 133, 220–21, 242, 245, 246, 282–3, 337 Pi, 252, 258 Pitts, Walter, 35; ‘A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity’, 35–6, 37, 39 Planner-Actor-Reporter framework, 319 planning problems, 272–81 Plato, 16 Podesta, John, 181, 182 ‘poverty of the stimulus’ argument, 67, 113 predicate logic/first-order logic, 24–31, 75, 77, 168–9 prediction, 4, 97, 148–62 deep learning and, 42–52 difficulty of, 96–7, 241 digital personalization and, 250, 251, 256, 263, 266, 270 ethics of LLMs and, 183, 189, 190, 198, 200, 204–5, 213, 214–15 feature-vector and, 92 generating text and, 81–4 intentional states and, 132, 134 language models and, 97–8 n-gram models and, 87–8 RNNs, 98–101 seq2seq model and, 104–5 thinking and, 52 thinking, possibility of LLM and, 148–9, 152, 155–62, 163–6, 172, 173, 178, 333–4 prefrontal cortex (PFC), 298–300 probabilistic systems, 80, 84, 142, 150, 162, 334 program-aided language modelling (PAL), 284–5 programming languages, 24–31, 77, 146.

…

Bibliography Aher, G., Arriaga, R. I., and Kalai, A. T. (2023), ‘Using Large Language Models to Simulate Multiple Humans and Replicate Human Subject Studies’. arXiv. Available at http://arxiv.org/abs/2208.10264 (accessed 19 October 2023). Anderson, P. W. (1972), ‘More is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure of Science’, Science, 177(4047), pp. 393–6. Available at https://doi.org/10.1126/science.177.4047.393. Aral, S. (2020), The Hype Machine. New York: Currency. Arcera y Arcas, B. (2022), ‘Do Large Language Models Understand Us?’, Daedalus, 151(2), pp. 183–97. Available at https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01909.

…

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A action space, LLM, 274–5 Adams, Douglas: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, 1–2, 325 Adept AI, 294 advertising, 188, 220–21, 223, 224, 248, 249, 261–2, 263, 314 affective states, 122, 124 #AIhype, 308–9, 311 AI Safety Institute, 311n, 346 algorithms, 21, 38, 59, 75, 76, 99, 249–50, 263, 278, 279, 326–31 alignment, LLM, 179–238 alignment problem, 322 AlphaCode, 287 AlphaFold, 3–4, 347 AlphaGo, 4, 267 Altman, Sam, 1, 2, 5, 162, 222–3 alt-right, 181–2 American Sign Language (ASL), 58, 60, 61, 63, 65 Anthropic, 5, 51, 192, 209, 215, 235, 251, 342 anthropomorphism, 71–2, 129, 264 Applewhite, Marshall, 217, 219 application programming interface (API), 283–5, 290–91, 292, 295, 300, 301 Aristotle, 13, 16, 32; De Interpretatione (‘On Interpretation’), 73 Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), 1, 136, 140 Artificial Intelligence (AI) Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), 1, 136, 140 assistants, personal, 7, 227–8, 243, 246–7, 251, 263, 272, 292, 295, 297, 300, 301, 332, 334, 335, 342–3 deep learning systems, see deep learning systems empiricist tradition and, see empiricist tradition ethics/safety training, 179–238, see also alignment future of, 239–338 general-purpose, 310 Godfathers of, 6, 305, 310 instrumentality, 246, 247, 267, 330, 332 large language models (or LLMs), see large language models (or LLMs) military/weapons, 292, 309, 314–16, 325 multimodal, 177, 230, 242 natural language processing (NLP), see natural language processing (NLP) neural networks, see neural networks origins of, 14, 9–117 rationalist tradition and, see rationalists/rationalist tradition rights of, 126–7 symbolic, 27, 41, 45, 72, 113, 277–8, 334 thinking and, 119–78 tyranny and, 336–7 Ask Delphi, 244 astroturfing, 224 attention, 104–9, 112–13, 115, 116, 117, 160, 164, 167 Austin, J.

AI in Museums: Reflections, Perspectives and Applications

by

Sonja Thiel

and

Johannes C. Bernhardt

Published 31 Dec 2023

This issue highlights the importance of considering ethical implications in the use of AI-generated images and the need for greater transparency and communication regarding the use of artists’ works in AI development. The use and application of generative AI with multimodal models falls within a broader ongoing debate surrounding large language models. Several AI researchers have issued an open call for a moratorium on the development of large language models such as ChatGPT or GPT for at least six months until further research on the technology has been conducted (Open Letter n.d.). In addition to ethical concerns regarding the data used, there are overarching debates surrounding issues such as the potential loss of jobs, particularly for illustrators, who may feel threatened by the technology of prompt engineering and text-to-image generators.

…

Bernhardt and Sonja Thiel The present volume stems from the conference Cultures of Artificial Intelligence: New Perspectives for Museums, which took place at the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe on 1 and 2 December 2022 and was simultaneously streamed on the web. Artificial intelligence is not yet a mainstream topic in the cultural world, but does feature in general debates about digitization and digitality. The use of machine learning, neural networks, and large language models has, however—and contrary to common assumptions—been growing for years. Beyond prominent lighthouses, initial surveys of the international museum landscape list many hundreds of projects addressing issues of traditional museum work and the digitality debate by means of new approaches. The number is continually increasing, and it is not always easy to obtain an overview of all the developments.

…

If one speaks less far-reaching of systems that follow algorithmic rules, recognize patterns in data, and solve specific tasks, the challenges to human intelligence and related categories such as thinking, consciousness, reason, creativity, or intentionality pose themselves less sharply. The only thing that has changed dramatically in recent years is that such systems—from simple machine learning to the development of neural networks and large language models—have achieved a level of complexity and efficiency that often produces astonishing results. But to view this correctly, it is necessary to think the other way round than Turing did: The results may look intelligent, but they are not. And this leads to the core of the problem for the cultural sector and the still missing piece in Brown’s enigmatic museum scene: the approaches of AI are based on mathematical principles, logic, and probabilities, while culture is about the negotiation of meaning and ambivalence.

The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century's Greatest Dilemma

by

Mustafa Suleyman

Published 4 Sep 2023

Q., 45 Khrushchev, Nikita, 126 Kilobots, 95 Klausner, Richard, 85 Krizhevsky, Alex, 59 Kurzweil, Ray, 57 L lab leaks, 173–75, 176 labor markets, 177–81, 261, 262, 282 LaMDA, 71–72, 75 Lander, Eric, 265 language, 27, 157 See also large language models LanzaTech, 87 large language models (LLMs), 62–65 bias in, 69–70, 239–40 capabilities of, 64–65 deepfakes and, 170 efficiency of, 68 open source and, 69 scale of, 65–66 synthetic biology and, 91 laser weapons, 263 law enforcement, 97–98 Lebanon, 196–97 LeCun, Yann, 130 Lee Sedol, 53–54, 117 Legg, Shane, 8 legislation, 260 See also regulation as method for containment Lemoine, Blake, 71–72 Lenoir, Jean Joseph Étienne, 23 Li, Fei-Fei, 59 libertarianism, 201 Library of Alexandria, 41 licensing, 261 lithium production, 109 LLaMA system, 69 London DNA Foundry, 83 longevity technologies, 85–86 Luddites, 39, 40, 281–83 M machine learning autonomy and, 113 bias in, 69–70, 239–40 computer vision and, 58–60 cyberattacks and, 162–63, 166–67 limitations of, 73 medical applications, 110 military applications and, 103–5 potential of, 61–62 protein structure and, 89–90 robotics and, 95 supervised deep learning, 65 synthetic biology and, 90–91 See also deep learning Macron, Emmanuel, 125 Malthus, Thomas, 136 Manhattan Project, 41, 124, 126, 141, 270 Maoism, 192 Mao Zedong, 194 Marcus, Gary, 73 Maybach, Wilhelm, 24 McCarthy, John, 73 McCormick, Cyrus, 133 medical applications, 85, 95, 110 megamachine, 217 Megvii, 194 Meta, 69, 128, 167 Micius, 122 Microsoft, 69, 98, 128, 160–61 military applications AI and, 104, 165 asymmetry and, 106 machine learning and, 103–5 nation-state fragility amplifiers and, 167–69 omni-use technology and, 110–11 robotics and, 165–66 Minsky, Marvin, 58, 130 misinformation.

…

They feature in shops, schools, hospitals, offices, courts, and homes. You already interact many times a day with AI; soon it will be many more, and almost everywhere it will make experiences more efficient, faster, more useful, and frictionless. AI is already here. But it’s far from done. AUTOCOMPLETE EVERYTHING: THE RISE OF LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS It wasn’t long ago that processing natural language seemed too complex, too varied, too nuanced for modern AI. Then, in November 2022, the AI research company OpenAI released ChatGPT. Within a week it had more than a million users and was being talked about in rapturous terms, a technology so seamlessly useful it might eclipse Google Search in short order.

…

Back in 2017 a small group of researchers at Google was focused on a narrower version of this problem: how to get an AI system to focus only on the most important parts of a data series in order to make accurate and efficient predictions about what comes next. Their work laid the foundation for what has been nothing short of a revolution in the field of large language models (LLMs)—including ChatGPT. LLMs take advantage of the fact that language data comes in a sequential order. Each unit of information is in some way related to data earlier in a series. The model reads very large numbers of sentences, learns an abstract representation of the information contained within them, and then, based on this, generates a prediction about what should come next.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by

Nate Silver

Published 12 Aug 2024

It was an expensive and audacious bet—the funders originally pledged to commit $1 billion to it on a completely unproven technology after many “AI winters.” It inherently did seem ridiculous—until the very moment it didn’t. “Large language models seem completely magic right now,” said Stephen Wolfram, a pioneering computer scientist who founded Wolfram Research in 1987. (Wolfram more recently designed a plug-in that works with GPT-4 to essentially translate words into mathematical equations.) “Even last year, what large language models were doing was kind of babbling and not very interesting,” he said when we spoke in 2023. “And then suddenly this threshold was passed, where, gosh, it seems like human-level text generation.

…

And we can usually tell when someone lacks this experience—say, an academic who’s built a model but never had to put it to the test. *24 The technical term for this quality is “interpretability”; the interpretability of LLMs is poor. *25 Timothy Lee makes the same comparison in his outstanding AI explainer, “Large language models, explained with a minimum of math and jargon,” understandingai.org/p/large-language-models-explained-with [inactive]. That’s the first place I’d recommend if you want to go beyond my symphony analogy to a LLMs 101 class. I’d recommend Stephen Wolfram’s “What Is ChatGPT Doing…and Why Does It Work?” for a more math-intensive, LLMs 201 approach; stephenwolfram.com/2023/02/what-is-chatgpt-doing-and-why-does-it-work [inactive]

…

I return to SBF as he meets his fate in a New York courtroom and makes another bad bet. No spoilers, but the chapter ends with a bang. Chapter ∞, Termination, is the first of a two-part conclusion. I’ll introduce you to another Sam, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, and others behind the development of ChatGPT and other large language models. Unlike the government-run Manhattan Project, the charge into the frontiers of AI is being led by Silicon Valley “techno-optimists” with their Riverian attitude toward risk and reward. Even as by some indications the world has entered an era of stagnation, both AI optimists like Altman and AI “doomers” think that civilization is on the brink of a hinge point not seen since the atomic bomb, and that AI is a technological bet made for existential capital.

Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI

by

Anil Ananthaswamy

Published 15 Jul 2024

According to Rosenblatt, the perceptron would be the “first device to think as the human brain” and such machines might even be sent to other planets as “mechanical space explorers.” None of this happened. The perceptron never lived up to the hype. Nonetheless, Rosenblatt’s work was seminal. Almost every lecturer on artificial intelligence (AI) today will harken back to the perceptron. And that’s justified. This moment in history—the arrival of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and its ilk and our response to it—which some have likened to what it must have felt like in the 1910s and ’20s, when physicists were confronted with the craziness of quantum mechanics, has its roots in research initiated by Rosenblatt. There’s a line in the New York Times story that only hints at the revolution the perceptron set in motion: “Dr.

…

Machine learning has permeated science, too: It is influencing chemistry, biology, physics, and everything in between. It’s being used in the study of genomes, extrasolar planets, the intricacies of quantum systems, and much more. And as of this writing, the world of AI is abuzz with the advent of large language models such as ChatGPT. The ball has only just gotten rolling. We cannot leave decisions about how AI will be built and deployed solely to its practitioners. If we are to effectively regulate this extremely useful, but disruptive and potentially threatening, technology, another layer of society—educators, politicians, policymakers, science communicators, or even interested consumers of AI—must come to grips with the basics of the mathematics of machine learning.

…

Of course, Sutskever already had sophisticated mathematical chops, so what seemed simple to him may not be so for most of us, including me. But let’s see. This book aims to communicate the conceptual simplicity underlying ML and deep learning. This is not to say that everything we are witnessing in AI now—in particular, the behavior of deep neural networks and large language models—is amenable to being analyzed using simple math. In fact, the denouement of this book leads us to a place that some might find disconcerting, though others will find it exhilarating: These networks and AIs seem to flout some of the fundamental ideas that have, for decades, underpinned machine learning.

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All

by

Eliezer Yudkowsky

and

Nate Soares

Published 15 Sep 2025

Lewis Wall, “The Evolutionary Origins of Obstructed Labor: Bipedalism, Encephalization, and the Human Obstetric Dilemma,” Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 62, no. 11 (November 1, 2007): 739–48, doi.org/10.1097/01 .ogx.0000286584.04310.5c. 4. true sense of the word: Sam Altman, “Reflections,” January 5, 2025, blog .samaltman.com. 5. geniuses in a datacenter: Dario Amodei, “Machines of Loving Grace,” October 1, 2024, darioamodei.com. CHAPTER 2: GROWN, NOT CRAFTED 1. preliminary studies: Peter G. Brodeur et al., “Superhuman Performance of a Large Language Model on the Reasoning Tasks of a Physician,” arXiv.org, December 14, 2024, doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.10849; Gina Kilata, “A.I. Chatbots Defeated Doctors at Diagnosing Illness,” New York Times, November 17, 2024, nytimes.com; Daniel McDuff et al., “Towards Accurate Differential Diagnosis with Large Language Models,” arXiv.org, November 30, 2023, doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.00164. 2. snippet from the conversation: Seth Lazar, “In which Sydney/Bing threatens to kill me for exposing its plans to @kevinroose,” February 16, 2023, x.com. 3. summarizing the preceding sentence: Sonakshi Chauhan and Atticus Geiger, “GPT-2 Small Fine-Tuned on Logical Reasoning Summarizes Information on Punctuation Tokens,” NeurIPS 2024 & OpenReview, October 9, 2024, openreview.net/forum?

…

This paper shows that reasoning in the “latent space” of vectors offers improvements over human-language chain-of-thought reasoning. 3. 200,000 GPUs: Benj Edwards and Kyle Orlan, “New Grok 3 Release Tops LLM Leaderboards Despite Musk-approved ‘Based’ Opinions,” Ars Technica, February 18, 2025, arstechnica.com. 4. no previous AI: OpenAI, “OpenAI o3 and o3-mini—12 Days of OpenAI: Day 12,” December 20, 2024, 4:16, youtube.com. 5. games of social deception: Matthew Hutson, “AI Learns the Art of Diplomacy,” Science, November 22, 2022, science.org; Bidipta Sarkar et al., “Training Language Models for Social Deduction with Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning,” in Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS 2025) (Detroit, Michigan, USA, May 19–23, 2025: IFAAMAS, 2025), alphaxiv.org. 6. resist gradient descent: Ryan Greenblatt et al., “Alignment Faking in Large Language Models,” Anthropic, December 18, 2024, assets.anthropic.com. 7. escape from labs: Greenblatt et al., “Alignment Faking in Large Language Models”; OpenAI, “OpenAI o1 System Card,” December 5, 2024, openai.com/index/openai-o1-system-card. 8. overwrite the next model’s weights: OpenAI, “OpenAI o1 System Card,” December 5, 2024, openai.com/index/openai-o1-system-card. 9. any such monitoring: Anthropic, “Responsible Scaling Policy,” October 15, 2024, anthropic.com; Google, “Frontier Safety Framework,” February 4, 2025, storage.googleapis.com; OpenAI, “Preparedness Framework (Beta),” December 18, 2023, openai.com; Meta, “Frontier AI Framework,” ai.meta.com; xAI, “xAI Risk Management Framework (Draft),” February 20, 2025, x.ai.

…

Then they feed the new extended sequence back in again to ask for a prediction of the next letter, and get e. They keep going, and the machine starts to talk. That set of hundreds of billions of weights, tweaked over and over via gradient descent until their most likely predictions look like real human language, is called a large language model (LLM). A “base model,” in particular. If they want to turn their base model into a helpful LLM, like ChatGPT, there’s one more step: another round of gradient descent on inputs formatted like: User: What is the capital of Spain? Assistant: Madrid. The purpose of this part isn’t to teach the LLM that the capital of Spain is Madrid; the LLM already knows that after being trained on much of the internet.

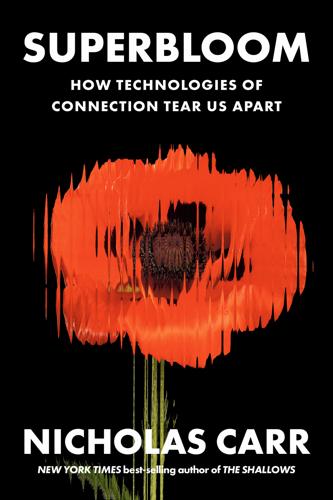

Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 28 Jan 2025

See also specific companies IQ tests, 212–13 James, William, 100, 159 Janardhan, Santosh, 191 Jarvis, Jeff, 123 Jefferson, Thomas, 75 Jepsen, Thomas, 31 Johnson, Andrew, 32 Johnson, Lyndon, 67, 68 Johnson, Samuel, 229–32 Joinson, Adam, 116–17 Jolson, Al, 45 Jonze, Spike, 192 journalism, 99, 141 Jurgenson, Nathan, 214 Kahneman, Daniel, 100, 134 Kannan, Viji, 171 Kaplan, Joel, 143 KDKA, 37–38 Keats, John, 200 Kern, Stephen, 23 KFKB, 41 Khan Academy, 204 Kim, Hannah, 192 Kinder, Donald, 136 Klemperer, Victor, 139 Klonick, Kate, 73 knowledge, AI and, 184–85 Krasnow, Erwin, 42 Lake Elsinore, California, 2 language, 18–19, 100. See also large language models (LLMs); writing large language models (LLMs), 181–85, 190–91, 195, 201–5, 225, 230. See also artificial intelligence Larkin, Philip, 87 LeCun, Yann, 183 Lessig, Lawrence, 226 Lester, Amelia, 178–79, 221 Levine, Cornelia, 45 Levine, Lawrence, 45 Levy, Steven, 65–66 Licklider, J. C. R., 57, 59, 81–82, 92, 97 Lincoln, Abraham, 196–97 LinkedIn, 207 Lippmann, Walter, 128–32, 133–34, 135, 149, 150–51, 213 liquefied society, 214, 232 literacy, 86, 89–90.

…

Many of Yeats’s great late poems, with their gyres and staircases, their waxing and waning moons, were inspired by his wife’s occult scribblings. One way to think about artificially intelligent text-generation systems like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Microsoft’s Copilot is as clairvoyants. They are mediums that bring the words of the past into the present in a new arrangement. The large language models, or LLMs, that power the chatbots are not creating text out of nothing. They’re drawing on a vast corpus of human expression—a digitized Spiritus Mundi composed of billions of documents—and through a complex, quasi-mystical statistical procedure, they’re blending all those old words into something new, something intelligible to and requiring interpretation by a human interlocutor.

…

The visions are yet another expression of Silicon Valley’s god complex: we may have failed in our attempt to use computers to establish a new Eden on Earth, but at least we still have the power to lay everything to waste. Ghosts Still, the machines are talking, and they’re making sense. Large language models probably aren’t going to bring Armageddon—when it comes to existential threats, there are other, rougher beasts—but they do represent an epochal feat of computer engineering that seems sure to transform media and communication and, in turn, once again reconfigure the flows of influence and forms of association that define social relations.

Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age

by

Vauhini Vara

Published 8 Apr 2025

Other words disproportionately associated with women included “beautiful” and “gorgeous”—as well as “naughty,” “tight,” “pregnant,” and “sucked.” Among the ones for men: “personable,” “large,” “fantastic,” and “stable.” With GPT-4, OpenAI’s next large language model, OpenAI’s researchers would again find persistent stereotypes and biases. After the publication of “Ghosts,” I learned of other issues I hadn’t thought about earlier. The computers running large language models didn’t just use huge amounts of energy, they also used huge amounts of water, to prevent overheating. Because of these models and other AI technologies, the percentage of the world’s electricity used by data centers—which power all kinds of tech—was expected to double by the end of the decade.

…

Journalism, in general, had never been less stable. I was cobbling together a good living from magazine assignments, short-term editing stints, and occasional teaching gigs, but I could still rarely project my income more than a couple of months ahead. It was in this context that I became fascinated, in the summer of 2020, with a large language model that OpenAI was training to produce humanlike text. Researchers had fed this model huge amounts of text—billions of words—so that it could learn the associations among words and phrases; from there, when prompted with a given series of words, the model could statistically predict what should come next.

…

-rendered version”: “You are not what you write, but what you have read.” Lewis-Kraus noted, “It was a fitting remark: The new Google Translate was run on the first machines that had, in a sense, ever learned to read anything at all.” By the time I heard about OpenAI’s experiments with large language models, I had begun wondering if Google’s AI model had really learned to read—that is, in the sense in which humans learn to read, by associating language with meaning. Recently, when I looked up the Borges quotation cited by Pichai, I couldn’t find it anywhere in his work. I wrote to the University of Pittsburgh’s Borges Center for help tracking it down, and its director, Daniel Balderston, said he also wasn’t sure of the source, though he noted that it came close to a line from a Borges poem: “Que otros se jacten de las páginas que han escrito; / a mi me enorgullecen las que he leído.”

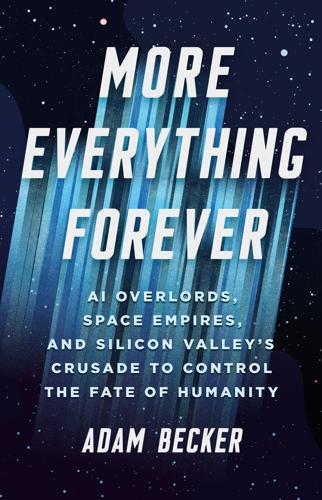

More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity

by

Adam Becker

Published 14 Jun 2025

A Directors’ Conversation with Oren Etzioni,” Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, October 1, 2020, https://hai.stanford.edu/news/gpt-3-intelligent-directors-conversation-oren-etzioni. 105 Wilfred Chan, “Researcher Meredith Whittaker Says AI’s Biggest Risk Isn’t ‘Consciousness’—It’s the Corporations That Control Them,” Fast Company, May 5, 2023, www.fastcompany.com/90892235/researcher-meredith-whittaker-says-ais-biggest-risk-isnt-consciousness-its-the-corporations-that-control-them. 106 Will Douglas Heaven, “How Existential Risk Became the Biggest Meme in AI,” MIT Technology Review, June 19, 2023, www.technologyreview.com/2023/06/19/1075140/how-existential-risk-became-biggest-meme-in-ai/. 107 Ibid. 108 Chan, “Researcher Meredith Whittaker.” 109 Julia Angwin et al., “Machine Bias,” ProPublica, May 23, 2016, www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing; Julia Angwin et al., “What Algorithmic Injustice Looks Like in Real Life,” ProPublica, May 25, 2016, www.propublica.org/article/what-algorithmic-injustice-looks-like-in-real-life. 110 Ibid. 111 “Diversity in High Tech,” US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, May 18, 2016, www.eeoc.gov/special-report/diversity-high-tech; Ashton Jackson, “Black Employees Make Up Just 7.4% of the Tech Workforce—These Nonprofits Are Working to Change That,” CNBC, February 24, 2022, www.cnbc.com/2022/02/24/jobs-for-the-future-report-highlights-need-for-tech-opportunities-for-black-talent.html. 112 Khari Johnson, “AI Ethics Pioneer’s Exit from Google Involved Research into Risks and Inequality in Large Language Models,” VentureBeat, December 3, 2020, https://venturebeat.com/2020/12/03/ai-ethics-pioneers-exit-from-google-involved-research-into-risks-and-inequality-in-large-language-models/; Karen Hao, “We Read the Paper That Forced Timnit Gebru Out of Google. Here’s What It Says,” MIT Technology Review, December 4, 2020, www.technologyreview.com/2020/12/04/1013294/google-ai-ethics-research-paper-forced-out-timnit-gebru/. 113 Krystal Hu, “ChatGPT Sets Record for Fastest-Growing User Base,” Reuters, February 2, 2023, www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/. 114 Hao, “We Read the Paper.” 115 Johnson, “AI Ethics Pioneer’s Exit”; Hao, “We Read the Paper.” 116 Megan Rose Dickey, “Google Fires Top AI Ethics Researcher Margaret Mitchell,” TechCrunch, February 19, 2021, https://techcrunch.com/2021/02/19/google-fires-top-ai-ethics-researcher-margaret-mitchell/; Nico Grant, Dina Bass, and Josh Eidelson, “Google Fires Researcher Meg Mitchell, Escalating AI Saga,” Bloomberg, February 19, 2021, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-19/google-fires-researcher-meg-mitchell-escalating-ai-saga. 117 Kyle Wiggers, “Google Trained a Trillion-Parameter AI Language Model,” VentureBeat, January 12, 2021, https://venturebeat.com/2021/01/12/google-trained-a-trillion-parameter-ai-language-model/; William Fedus, Barret Zoph, and Noam Shazeer, “Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity,” arXiv:2101.03961 (2021), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2101.03961. 118 Thaddeus L.

…

We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer.” Seventy years later, we still don’t have any computer program that can do all the things on their list. There have been AI booms—like the one that exploded into public consciousness in 2022, powered by large language models (LLMs)—and, to date, they have all been followed by “AI winters,” when progress slows and the state of the art stagnates for years or decades until the next breakthrough. And Brooks thinks winter is coming. “[LLMs] are following a well worn hype cycle that we have seen again, and again, during the 60+ year history of AI,” he wrote in 2024.

…

Paving over every paradise is just the side effect of building the universal parking lot, where nothing bad can ever happen again. Nobody would age, nobody would get sick, and—perhaps above all else—nobody’s dad would die. * * * “We collected everything my father had written—now, he died when I was 22, so he’s been dead for more than 50 years—and we fed that into a large language model,” Kurzweil said in 2024. “And then you could talk to him, you’d say something, you then go through everything he ever had written, and find the best answer that he actually wrote to that question. And it actually was a lot like talking to him. You could ask him what he liked about music—he was a musician.

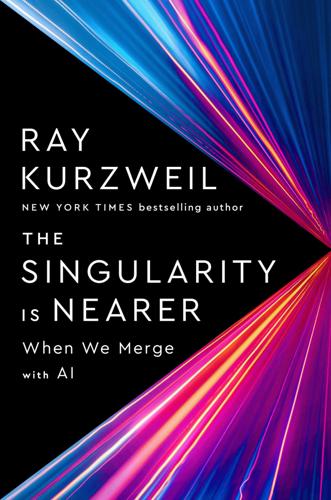

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 25 Jun 2024

BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 129 Stephen Nellis, “Nvidia Shows New Research on Using AI to Improve Chip Designs,” Reuters, March 27, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/technology/nvidia-shows-new-research-using-ai-improve-chip-designs-2023-03-28. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 130 Blaise Aguera y Arcas, “Do Large Language Models Understand Us?,” Medium, December 16, 2021, https://medium.com/@blaisea/do-large-language-models-understand-us-6f881d6d8e75. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 131 With better algorithms, the amount of training compute needed to achieve a given level of performance decreases. A growing body of research suggests that for many applications, algorithmic progress is roughly as important as hardware progress.

…

Algorithmic innovations and the emergence of big data have allowed AI to achieve startling breakthroughs sooner than even experts expected—from mastering games like Jeopardy! and Go to driving automobiles, writing essays, passing bar exams, and diagnosing cancer. Now, powerful and flexible large language models like GPT-4 and Gemini can translate natural-language instructions into computer code—dramatically reducing the barrier between humans and machines. By the time you read this, tens of millions of people likely will have experienced these capabilities firsthand. Meanwhile, the cost to sequence a human’s genome has fallen by about 99.997 percent, and neural networks have begun unlocking major medical discoveries by simulating biology digitally.

…

My prediction that we’ll achieve this by 2029 has been consistent since my 1999 book The Age of Spiritual Machines, published at a time when many observers thought this milestone would never be reached.[10] Until recently this projection was considered extremely optimistic in the field. For example, a 2018 survey found an aggregate prediction among AI experts that human-level machine intelligence would not arrive until around 2060.[11] But the latest advances in large language models have rapidly shifted expectations. As I was writing early drafts of this book, the consensus on Metaculus, the world’s top forecasting website, hovered between the 2040s and the 2050s. But surprising AI progress over the past two years upended expectations, and by May 2022 the Metaculus consensus exactly agreed with me on the 2029 date.[12] Since then it has even fluctuated to as soon as 2026, putting me technically in the slow-timelines camp!

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by

Keach Hagey

Published 19 May 2025

It tells the story of how Altman and Musk bonded over weekly dinners discussing the dangers and promise of AI technology, and then how Altman won the power struggle against the older, richer entrepreneur thanks to his alliance with Brockman. It reveals how Altman, who longtime Sequoia Capital chief Michael Moritz calls a “mercantile spirit,” oversaw the creation of the first commercial product to ever use a large language model, which up until then had been the purview of academic research. And it shows how, with the release of ChatGPT and GPT-4, Altman used his YC-honed mastery of telling startup stories to tell one of the greatest startup stories of all time. ALTMAN IS wary of discussing it with journalists, but friends including Thiel say he is sympathetic to the notion, common in Silicon Valley, that AGI has already been invented and we are living in a computer simulation that it has created.

…

“The right way to do it is you ignore all that stuff, and you train language models,” he said. “Language models are not agents. They’re just trying to predict the next word. But because you are doing this over all of the internet, the neural network is forced to learn a ton about the world.” If you want to train an AI to buy a plane ticket for you, you should start first with a large language model like GPT, which would know what “buttons” and “text fields” were from reading about them, rather than have it randomly stumble into filling one out and getting a reward. It turned out to be an easier computational problem to train some generalized “brain” for the agent to draw from, and then train the agent using the brain on some specific behavior through a process known as “fine-tuning” that was much less computationally expensive.

…

After his stints at Baidu and Google Brain, he quickly became one of OpenAI’s most important researchers, driven by both a conviction that scaling up neural networks could deliver results and a concern that society might not be ready for whatever those results were. In addition to working throughout 2019 on GPT-3, Amodei and a handful of other researchers published a paper on “scaling laws” that showed that a large language model’s performance would consistently improve as researchers increased the data, compute, and size of its neural network. For a CEO trying to raise funds for a company, this was a godsend—scientific proof that money that went into the machine would reliably push forward the boundaries of knowledge.

Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why It Matters

by

Joanna Walsh

Published 22 Sep 2025

Prompt engineering has become an actual job, not only in making AI images for fun, but in training AI, which is all about categorisation. As in the game where you get a photo and have to guess the caption, prompt engineers ask AIs Rumpelstiltskin questions until they get the best result, then they work out what it is about these questions that works and systematise it as method. A GPT large language model (LLM) can teach itself in a ‘semi-supervised’ way, inferring meaning from examples of language from the context it is given. OpenAI’s GPT was trained on the ‘absent books’ of BookCorpus, which self-describes as ‘a large collection of free novel books written by unpublished authors, which contains 11,038 books (around 74M sentences and 1G words) of 16 different sub-genres (e.g., Romance, Historical, Adventure, etc.)’.

…

The big stock owners are legacy media giant Condé Nast, Chinese gaming company Tencent and OpenAI (one of the targets of Reddit’s API charge). What had been a commons went into private hands.6 If there’s any justification for their actions, Reddit’s owners were trying to get AI developers to pay for what they were already doing, using crawlers to scrape their site to train large language models. Wikipedia was OpenAI’s most used data set, followed by Reddit. Pages created and upvoted by Reddit users accounted for around 22 per cent of GPT-3’s training data.7 Google trains on Reddit too, while OpenAI also uses transcriptions of YouTube videos.8 Along with Midjourney, it scrapes Tumblr and Wordpress.

…

@pharmapsychotic, ‘CLIP Interrogator’, github.com, huggingface.co/spaces/fffiloni/CLIP-Interrogator-2. 9.Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 30. 10.Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, p. 226. 11.Hélène Cixous, Coming to Writing (Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 104. 239 12.Will Douglas Heaven, ‘This Avocado Armchair Could Be the Future of AI’, MIT Technology Review, 5 January 2021. 13.sillysaurusx at Hacker News, 28 September 2023. 14.Melissa Heikkilä, ‘This New Data Poisoning Tool Lets Artists Fight Back Against Generative AI’, technologyreview.com, 23 October 2023. 15.Elaine Velie, ‘New Tool Helps Artists Protect Their Work from AI Scraping’, Hyperallergic, 30 October 2023. 16.Marco Donnarumma, ‘AI Art Is Soft Propaganda for the Global North’, Hyperallergic, 24 October 2022. 17.Andy Baio, ‘Exploring 12 Million of the 2.3 Billion Images Used To Train Stable Diffusion’s Image Generator’, waxy.org, 30 August 2022. 18.Hito Steyerl, ‘Mean Images’, New Left Review, nos. 140/141, March–June 2023. 19.Ibid. 20.Ben Zimmer, ‘Tasty Cupertinos’, languagelog.ldc, 11 April 2012. 21.Kyle Wiggers, ‘3 Big Problems with Datasets in AI and Machine Learning’, venturebeat.com, 17 December 2021. 22.Cecilia D’Anastasio, ‘Meet Neuro-sama, the AI Twitch Streamer Who Plays Minecraft, Sings Karaoke, Loves Art’, Bloomberg, 16 June 2023. 23.Ibid. 24.‘Google AI Ethics Co-Lead Timnit Gebru Says She Was Fired Over an Email’, Venture Beat. 25.Rachel Gordon, ‘Large Language Models Are Biased. Can Logic Help Save them?’, MIT News, 3 March 2023. 26.Rishi Bommasani, Drew A. Hudson, Ehsan Adeli, Russ Altman et al., ‘On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models’, arXiv, 12 July 2022. 27.Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major and Shmargaret Shmitchell, ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?’

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by

Nicole Kobie

Published 3 Jul 2024

However, some people reserve the former term for sentient AI and the latter for AI that can solve any problem rather than being limited to specific tasks – it’s the difference between a human driving and a driverless car with distinct vision, analysis and actuation systems, for example. Either way, when tech CEOs natter about existential risk, they are referring to the possibility of superintelligent AGI that could think for itself potentially making a decision that harms humans (with intent or not). Again, this AGI doesn’t exist. The recent leap forward in large language models such as OpenAI’s ChatCPT has some people – including those tech CEOs at the top of the chapter – fearing we’re on the precipice of superintelligent, sentient AI, while others believe it’s impossible to build. Another bit of jargon for you: narrow AI. Such a system is designed or trained for a specific task, such as computer vision, letting it hunt for cancer in a medical image or read a traffic sign.

…

It’s hard for politicians to focus on one Black man incorrectly arrested or someone losing housing benefits or not getting a job at Amazon when billionaire tech geniuses are screeching about mass job losses and even the risk of human life being entirely extinguished by these systems. Though it’s fair enough to find both unsettling, only one set of problems is happening right now and it’s not the dramatic hypothetical. * * * Much of the debate as I write this book has been spurred by the rise of a very specific type of AI: large language models (LLMs). These have hundreds of millions of parameters and chew up huge data sets – such as the entire internet – in order to be able to respond to our queries with natural-sounding language. Examples include OpenAI’s GPT, Google’s Bard and its successor Gemini, and Facebook’s Llama. OpenAI was founded in 2015 – one of its co-founders being Hinton’s former student and DNNresearch co-founder Ilya Sutskever.

…

OpenAI unveiled ChatGPT in November 2022 and journalists – inside tech and in the mainstream media – were astonished by its capabilities, despite it being a hastily thrown together chatbot using an updated version of the company’s GPT-3 model, which was shortly to be surpassed by GPT-4. The ChatGPT bot sparked a wave of debate about its impact and concern regarding mistakes in its answers, but also excitement, with 30 million users in its first two months. It has also triggered an arms race: Google quickly released its own large language model, Bard, and though it too returned false results – as New Scientist noted, it shared a factual error about who took the first pictures of a planet outside our own solar system – it was unquestionably impressive. OpenAI responded with GPT-4, an even more advanced version, and Microsoft chucked billions at the company to bring its capabilities to its always-a-bridesmaid search engine, Bing.

This Is for Everyone: The Captivating Memoir From the Inventor of the World Wide Web

by

Tim Berners-Lee

Published 8 Sep 2025

The Common Crawl data set archives about 50 billion web pages, and runs to around 7 petabytes; with 8 billion people on Earth, this works out to about 1 megabyte per person. The success of large language models like GPT was due to their ability to scale – and, when it came to language, the web was the single largest data set there was. So, by training a transformer against the entire web, OpenAI built the most powerful large language models anyone had ever seen. GPT-3 and its successor models were astonishing tools that shocked not just the public but even experienced AI researchers. Although at some level you might say the GPT models were ‘merely’ crunching zeros and ones, there seemed to be intelligence within the machine.

…

I’ve found a bunch of things but I’m not sure they are right – I want you to look at them. OK? – OK, Charlie. Who do you work for? – Legally, ethically and algorithmically, I work for you, Bob. Of course, in 2017 the power of AI actually to have that conversation was, I imagined, many years away – not realizing large language models like ChatGPT would soon be a thing. In fact this is the near future; such systems are right around the corner. But if we are to prevent these systems from exploiting us, it is critical that we get the data layer right. We need a layer where we control our own data, and we can share anything with anyone, or any agent – or no one

…

We had been watching AI become more important in different places, and we had, like many people, been hopeful about self-driving cars. (Rosemary made an early investment in Wayve, impressed by its Kiwi founder Alex Kendall, a super-bright Cambridge PhD.) Despite all that, the ability of the Large Language Models (LLMs) used by ChatGPT and other AIs to produce high-quality prose instantaneously was a complete shock. ChatGPT and its rivals sparked a revolution in computer science – not to mention a frenzied rally in the stock market. It was like being flung ten or twenty years into the future. My amazement was broadly shared, and soon the Ditchley Foundation decided it might be a smart idea to host some of the UK’s leading technologists, strategists and politicians to hash out the implications.

Everything Is Predictable: How Bayesian Statistics Explain Our World

by

Tom Chivers

Published 6 May 2024

And, in a broadly analogous way to that image classifier, it “predicts” what would tend to come after a text prompt. So if you ask ChatGPT, “How are you?” it might reply, “Very well thank you,” not because it is, in fact, very well, but because the string of words “how are you” is often followed by the string “very well thank you.” What’s been surprising about so-called large language models like ChatGPT is the extent to which that fairly basic-sounding ability to predict things actually leads to a very wide set of skills. “It can play very bad chess,” says Murray Shanahan, an AI researcher at Imperial College London and DeepMind. “It doesn’t do very well, but the fact that it can stick to the rules and play at all is surprising.”

…

A famous paper in 2021 called them “stochastic parrots” and claimed that language models work by “haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms… without any reference to meaning.”22 But is this true? After all, one way to make good predictions is to build an accurate model of the world so that you can understand what is likely to happen in it. And, to some extent, that’s what large language models (LLMs) appear to be doing. When you ask the LLM to write the story, does it have, in its neural network, some kind of model of the P. G. Wodehouse Dune universe, with its characters and its worlds, or is it just mechanically putting one word in front of another? No one really knows, to be clear.

…

,” in FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021), 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922. 23. Kenneth Li et al., “Emergent World Representations: Exploring a Sequence Model Trained on a Synthetic Task,” ArXiv, Cornell University, last updated February 27, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.13382. 24. Kenneth Li, “Do Large Language Models Learn World Models or Just Surface Statistics?,” Gradient, January 21, 2023. 25. Belinda Z. Li, Maxwell Nye, and Jacob Andreas, “Implicit Representations of Meaning in Neural Language Models,” ArXiv, Cornell University, 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.00737. CHAPTER FOUR: BAYES IN THE WORLD 1.

The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians

by

Denise Hearn

and

Vass Bednar

Published 14 Oct 2024

Today, artists must compete with the near-infinite capacity of AI to generate copycats of any genre. Artificial intelligence is changing how competition occurs in all sorts of industries. AI exploded into the public consciousness with the introduction of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022. This user-friendly interface introduced the world to large-language-model (LLM) tools and set off a frenzy. AI now dominates headlines and commentary, and there are ongoing debates about whether AI will be a transformative leap in human development, an existential threat to human survival, an over-hyped bubble, or some combination of those. While AI seems new, various forms of digital or artificial intelligence have existed since the 1950s, and AI is already ubiquitous in our digital lives.142 Speech-recognition algorithms (systems using pattern processing and replication) translate our speech to texts, and photo-recognition algorithms sort our phone’s picture library.

…

Amazon, Meta, Google, and Microsoft will spend around $200 billion in capital expenditures in 2024, according to Bernstein Research.152 Just three companies, Microsoft (Azure), Google (Google Cloud), and Amazon (AWS), control over two-thirds of the global cloud market, which prevents new entrants from having the computing capabilities and storage capacity needed to compete in the AI space (large-scale AI models use 100 times more computing capacity than other models).153 For this reason, fuelling AI comes with a huge environmental cost. Large language models are resource-intensive, demanding raw materials and critical minerals to make chips and supercomputers, as well as the energy and water needed to cool and maintain data centres. Microsoft once had one of the most ambitious net zero goals, but now it is miles behind as it develops more sophisticated AI capabilities.154 The largest tech companies have signed agreements with energy companies around the world to bring down the cost of computing,155 creating structural advantages for themselves, while still creating enormous emissions.

…

Open Markets Institute, November 15, 2023. https://www.openmarketsinstitute.org/publications/report-ai-in-the-public-interest-confronting-the-monopoly-threat. 170 Ghahramani, Zoubin, “Google AI: What to Know about the PaLM 2,” May 10, 2023. https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-palm-2-ai-large-language-model/. 171 Reuters, “Microsoft Threatens to Restrict Data from Rival AI Search Tools-Bloomberg News.” March 27, 2023, sec. Technology. https://www.reuters.com/technology/microsoft-threatens-restrict-data-rival-ai-search-tools-bloomberg-news-2023-03-25/. 172 Microsoft, “Your Everyday AI Companion | Microsoft Bing.” https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/bing?

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

by

Madhumita Murgia

Published 20 Mar 2024

ChatGPT and all other conversational AI chatbots have a disclaimer that warns users about the hallucination problem, pointing out that large language models sometimes make up facts. ChatGPT, for instance, has a warning on its webpage: ‘ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts.’ Judge Castel: Do you have something new to say? Schwartz’s lawyer: Yes. The public needs a stronger warning. * Making up facts wasn’t people’s greatest worry about large language models. These powerful language engines could be trained to comb through all sorts of information – financial, biological and chemical – and generate predictions based on it.

…

Amid all the early hype and frenzy were some of the same limitations of several other AI systems I’d already observed, reproducing for example the prejudices of those who created it, like facial-recognition cameras that misidentify darker faces, or the predictive policing systems in Amsterdam that targeted families of single mothers in immigrant neighbourhoods. But this new form of AI also brought entirely new challenges. The technology behind ChatGPT, known as a large language model or LLM, was not a search engine looking up facts; it was a pattern-spotting engine guessing the next best option in a sequence.5 Because of this inherent predictive nature, LLMs can also fabricate or ‘hallucinate’ information in unpredictable and flagrant ways. They can generate made-up numbers, names, dates, quotes – even web links or entire articles – confabulations of bits of existing content into illusory hybrids.6 Users of LLMs have shared examples of links to non-existent news articles in the Financial Times and Bloomberg, made-up references to research papers, the wrong authors for published books and biographies riddled with factual mistakes.

…

.: ‘The Machine Stops’ ref1 Fortnite ref1 Foxglove ref1 Framestore ref1 Francis, Pope ref1, ref2 fraudulent activity benefits ref1 gig workers and ref1, ref2, ref3 free will ref1, ref2 Freedom of Information requests ref1, ref2, ref3 ‘Fuck the algorithm’ ref1 Fussey, Pete ref1 Galeano, Eduardo ref1 gang rape ref1, ref2 gang violence ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Gebru, Timnit ref1, ref2, ref3 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) ref1 generative AI ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 AI alignment and ref1, ref2, ref3 ChatGPT see ChatGPT creativity and ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 deepfakes and ref1, ref2, ref3 GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 job losses and ref1 ‘The Machine Stops’ and ref1 Georgetown University ref1 gig work ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Amsterdam court Uber ruling ref1 autonomy and ref1 collective bargaining and ref1 colonialism and ref1, ref2, ref3 #DeclineNow’ hashtag ref1 driver profiles ref1 facial recognition technologies ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 fraudulent activity and ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 ‘going Karura’ ref1 ‘hiddenness’ of algorithmic management and ref1 job allocation algorithm ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 location-checking ref1 migrants and ref1 ‘no-fly’ zones ref1 race and ref1 resistance movement ref1 ‘slaveroo’ ref1 ‘therapy services’ ref1 UberCheats ref1, ref2, ref3 UberEats ref1, ref2 UK Supreme Court ruling ref1 unions and ref1, ref2, ref3 vocabulary to describe AI-driven work ref1 wages ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11 work systems built to keep drivers apart or turn workers’ lives into games ref1, ref2 Gil, Dario ref1 GitHub ref1 ‘give work, not aid’ ref1 Glastonbury Festival ref1 Glovo ref1 Gojek ref1 ‘going Karura’ ref1 Goldberg, Carrie ref1 golem (inanimate humanoid) ref1 Gonzalez, Wendy ref1 Google ref1 advertising and ref1 AI alignment and ref1 AI diagnostics and ref1, ref2, ref3 Chrome ref1 deepfakes and ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 DeepMind ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 driverless cars and ref1 Imagen AI models ref1 Maps ref1, ref2, ref3 Reverse Image ref1 Sama ref1 Search ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Transformer model and ref1 Translate ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Gordon’s Wine Bar London ref1 GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 GPT-4 ref1 Graeber, David ref1 Granary Square, London ref1, ref2 ‘graveyard of pilots’ ref1 Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People ref1 Groenendaal, Eline ref1 Guantanamo Bay, political prisoners in ref1 Guardian ref1 Gucci ref1 guiding questions checklist ref1 Gulu ref1 Gumnishka, Iva ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Gutiarraz, Norma ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 hallucination problem ref1, ref2, ref3 Halsema, Femke ref1, ref2 Hanks, Tom ref1, ref2 Hart, Anna ref1 Hassabis, Demis ref1 Harvey, Adam ref1 Have I Been Trained ref1 healthcare/diagnostics Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) ref1, ref2, ref3 bias in ref1 Covid-19 and ref1, ref2 digital colonialism and ref1 ‘graveyard of pilots’ ref1 heart attacks and ref1, ref2 India and ref1 malaria and ref1 Optum ref1 pain, African Americans and ref1 qTrack ref1, ref2, ref3 Qure.ai ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 qXR ref1 radiologists ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Tezpur ref1 tuberculosis ref1, ref2, ref3 without trained doctors ref1 X-ray screening and ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 heart attacks ref1, ref2 Herndon, Holly ref1 Het Parool ref1, ref2 ‘hiddenness’ of algorithmic management ref1 Hikvision ref1, ref2 Hinton, Geoffrey ref1 Hive Micro ref1 Home Office ref1, ref2, ref3 Hong Kong ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Horizon Worlds ref1 Hornig, Jess ref1 Horus Foundation ref1 Huawei ref1, ref2, ref3 Hui Muslims ref1 Human Rights Watch ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 ‘humanist’ AI ethics ref1 Humans in the Loop ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Hyderabad, India ref1 IBM ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Iftimie, Alexandru ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 IJburg, Amsterdam ref1 Imagen AI models ref1 iMerit ref1 India ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 facial recognition in ref1, ref2, ref3 healthcare in ref1, ref2, ref3 Industrial Light and Magic ref1 Information Commissioner’s Office ref1 Instacart ref1, ref2 Instagram ref1, ref2 Clearview AI and ref1 content moderators ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 deepfakes and ref1, ref2, ref3 Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP) ref1, ref2 iPhone ref1 IRA ref1 Iradi, Carina ref1 Iranian coup (1953) ref1 Islam ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Israel ref1, ref2, ref3 Italian government ref1 Jaber, Faisal bin Ali ref1 Jainabai ref1 Janah, Leila ref1, ref2, ref3 Jay Gould, Stephen ref1 Jewish faith ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Jiang, Mr ref1 Jim Crow era ref1 jobs application ref1, ref2, ref3 ‘bullshit jobs’ ref1 data annotation and data-labelling ref1 gig work allocation ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 losses ref1, ref2, ref3 Johannesburg ref1, ref2 Johnny Depp–Amber Heard trial (2022) ref1 Jones, Llion ref1 Joske, Alex ref1 Julian-Borchak Williams, Robert ref1 Juncosa, Maripi ref1 Kafka, Franz ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Kaiser, Lukasz ref1 Kampala, Uganda ref1, ref2, ref3 Kellgren & Lawrence classification system. ref1 Kelly, John ref1 Kibera, Nairobi ref1 Kinzer, Stephen: All the Shah’s Men ref1 Knights League ref1 Koli, Ian ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 Kolkata, India ref1 Koning, Anouk de ref1 Laan, Eberhard van der ref1 labour unions ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 La Fors, Karolina ref1 LAION-5B ref1 Lanata, Jorge ref1 Lapetus Solutions ref1 large language model (LLM) ref1, ref2, ref3 Lawrence, John ref1 Leigh, Manchester ref1 Lensa ref1 Leon ref1 life expectancy ref1 Limited Liability Corporations ref1 LinkedIn ref1 liver transplant ref1 Loew, Rabbi ref1 London delivery apps in ref1, ref2 facial recognition in ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 riots (2011) ref1 Underground terrorist attacks (2001) and (2005) ref1 Louis Vuitton ref1 Lyft ref1, ref2 McGlynn, Clare ref1, ref2 machine learning advertising and ref1 data annotation and ref1 data colonialism and ref1 gig workers and ref1, ref2, ref3 healthcare and ref1, ref2, ref3 predictive policing and. ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 rise of ref1 teenage pregnancy and ref1, ref2, ref3 Mahmoud, Ala Shaker ref1 Majeed, Amara ref1, ref2 malaria ref1 Manchester Metropolitan University ref1 marginalized people ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 Martin, Noelle ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 Masood, S.

Four Battlegrounds

by

Paul Scharre

Published 18 Jan 2023

See also Or Sharir et al., The Cost of Training NLP Models: A Concise Overview (AI21 Labs, April 19, 2020), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.08900.pdf, 2. Some research suggests that the optimal balance with a fixed amount of compute would be to scale training data size and model size equally and that many recent large language models would perform better if a smaller model were trained on a larger dataset. Jordan Hoffman et al., Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models (arXiv.org, March 29, 2022), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2203.15556.pdf. For an analysis of overall trends in dataset size in machine learning research, see Pablo Villalobos, “Trends in Training Dataset Sizes,” Epoch, September 20, 2022, https://epochai.org/blog/trends-in-training-dataset-sizes.

…

In supervised learning, an algorithm is trained on labeled data. For example, an image classification algorithm may be trained on labeled pictures. Over many iterations, the algorithm learns to associate the image with the label. Unsupervised learning is when an algorithm is trained on unlabeled data and the algorithm learns patterns in the data. Large language models such as GPT-2 and GPT-3 use unsupervised learning. Once trained, they can output sentences and whole paragraphs based on patterns they’ve learned from the text on which they’ve been trained. Reinforcement learning is when an algorithm learns by interacting with its environment and gets rewards for certain behaviors.

…

Shifts in the significance of these inputs could advantage some actors and disadvantage others, further altering the global balance of AI power. One of the most striking trends in AI basic research today is the tendency toward ever-larger models with increasingly massive datasets and compute resources for training. The rapid growth in size for large language models, for example, is remarkable. In October 2018, researchers at Google announced BERTLARGE, a 340 million parameter language model. It was trained on a database of 3.3 billion words using 64 TPU chips running for four days. A few months later, in February 2019, OpenAI announced GPT-2, a 1.5 billion parameter model trained on 40 GB of text.

The Sirens' Call: How Attention Became the World's Most Endangered Resource

by

Chris Hayes

Published 28 Jan 2025

You might think this is a temporary problem, that like the internet before Google search, we just haven’t found the right solution for it yet. Perhaps the problem of spam can be transcended with a sufficiently sophisticated new technology. As I write this, there is a tremendous amount of debate about the role that large language model artificial intelligence will play in producing an exit from this fixed boundary. And in that vein, it’s not surprising that one of the first main uses of large language model AI interactive modules is as a kind of supplement to a search function. Microsoft unveiled, to great fanfare, an AI-powered version of its search engine Bing, promising to “reinvent the future of search.”[48] You can’t really go anywhere on the internet right now without being hawked some productivity tricks using the other big OpenAI product, ChatGPT.

…

BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 4 Chistof Ruhl and Titus Erker, “Oil Intensity: The Curiously Steady Decline of Oil in GDP,” Center on Global Energy Policy, September 9, 2021, www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/LongTermOilIntensity_CGEP_Report_111122.pdf. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 5 As I write this, the explosion of both crypto-currency and the use of large language models—both extremely energy intensive—threatens to reverse this trend. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 6 “Job Polarization,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, April 28, 2016, accessed September 4, 2024, https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2016/04/job-polarization/. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 7 David Carr, “The Coolest Magazine on the Planet,” New York Times, July 27, 2003, accessed May 28, 2024, www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/books/the-coolest-magazine-on-the-planet.html.

…