Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order

by

Bruno Maçães

Published 1 Feb 2019

The Chinese political and economic model converges with Western patterns—but less drastically than in the first scenario—and, more importantly, the liberal world order survives unscathed: multilateral institutions, open trade, international cooperation on common challenges and even some form of individual and community rights. The third scenario is one where China takes over from the Unites States as the center of global power with the result that the very structure and values of the world system are rethought and reconfigured. The liberal world order is replaced with a Chinese order, Western values give way to Chinese values and the pace of historical development is increasingly dictated from Beijing.

…

China has become ever more entrenched inside Europe and the question at present is whether and how European countries can regain some measure of control over the mechanisms of Chinese influence. As a recent report puts it, China remains convinced that it is Europe which stands at risk of leaving itself stranded in a world where even the United States may be moving away from the liberal world order. Increasingly isolated, the European Union will try to avoid conflict at all costs. Europe will have to come around to the essential goals and values of the Belt and Road or face isolation, not the reverse. As the initiative is gradually implemented, the EU’s ability to shape it in a particular direction will tend to disappear.13 Geographically, the sixteen countries in Central and Eastern Europe with which China has been developing closer ties form the last link in the complex future network linking Asia and Europe.

…

Instead of integrating into the existing world order, China could be creating a separate economic bloc, with different dominant companies and technologies, and governed by rules, institutions, and trade patterns dictated by Beijing.26 A balance between China and the United States may take place within the framework of common values and principles or it may be organized around fundamental differences on the question of the world order. Increasingly, it seems that Chinese leaders regard the ability to break with the liberal world order as a measure of their success and the Belt and Road as the main tool to bring about an alternative vision. Convergence was a powerful idea, perhaps the most powerful foreign policy idea of the last three decades. As Thomas Wright puts it, everyone or almost everyone believed that as countries embraced globalization their political systems would become more liberal and democratic.

The Light That Failed: A Reckoning

by

Ivan Krastev

and

Stephen Holmes

Published 31 Oct 2019

And it does so condescendingly, with the aim of humiliating the Americans and cutting them down to size. Resentment of Americanization provides a powerful (if only partial) explanation for Central Europe’s domestic illiberalism and Russia’s foreign-policy belligerence. But what about the United States? Why would so many Americans support a president who sees America’s commitment to the liberal world order as its main vulnerability? Why would Trump’s supporters implicitly accept his eccentric idea that the United States should stop being a model for other countries and perhaps even remake itself in the image of Orbán’s Hungary and Putin’s Russia? Trump won both popular and business support by declaring the United States to be the greatest loser from the Americanization of the world.

…

The white voter’s perception that China is stealing American jobs and the business community’s perception that China is stealing American technology helped Trump’s eccentric message of American victimization – despite its being a radical break from the country’s traditional self-image – gain a crude plausibility that it had never previously enjoyed. This preliminary example illustrates how the model and not only the mimics can come to resent the politics of imitation and, in this case, how the leader of the country that built the liberal world order could decide to do everything in his power to tear it down. China also provides a natural finale to our argument because the rise of an internationally assertive China, ready to contest US hegemony, signals the end of the Age of Imitation as we understand it. In his December 2018 resignation letter to the US President, Secretary of Defense James Mattis wrote that Chinese leaders ‘want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model’.

…

At around that time, for reasons to be discussed, the Kremlin shifted to a strategy of selective mirroring or violent parody of Western foreign policy behaviour meant to expose the West’s relative weakness in the face of Kremlin aggression and to erode the normative foundations of the American-led liberal world order. We are still in this third phase today. Life after the end of history has stopped being a ‘sad time’ characterized by ‘bourgeois ennui’ and has begun to resemble the iconic Hall of Mirrors scene in Orson Welles’ 1947 classic The Lady from Shanghai, a world of shared paranoia and escalating aggression.

This America: The Case for the Nation

by

Jill Lepore

Published 27 May 2019

Over that same stretch of time, the United States waged wars of conquest across the continent, fell into a civil war, fought two world wars, and entered a cold war, while a people held in bondage fought for their emancipation only to face a legal regime of segregation and a vigilante campaign of terrorism, leading to a decades-long struggle for civil rights, even as the United States became the leader of a liberal world order. If American historians didn’t always succeed in affirming a common history during these tumultuous years—and they didn’t—they nevertheless engaged in the struggle, offering appraisals and critiques of national aims and ends, advancing arguments, fostering debate, defending democracy, and celebrating, often lyrically, the beauty of the land, the inventiveness of the people, and the vitality of American ideals.

…

If love of the nation had driven American historians to the study of the past in the nineteenth century, hatred for nationalism drove American historians away from it in the second half of the twentieth century. That nationalism is a contrivance, an artifice, a fiction, had long been clear. After the Second World War, even as Roosevelt was helping to establish what came to be called the liberal world order, internationalists began predicting the end of the nation-state, Harvard political scientist Rupert Emerson declaring “that the nation and the nation-state are anachronisms in the atomic age.” By the 1960s, an era marked by a rising tide of anti-Americanism, the nation-state looked rather worse than an anachronism.

Kicking Awaythe Ladder

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 4 Sep 2000

Britain was then able to play the role of the architect and hegemon of a new 'Liberal' world economic order, particularly once it had abandoned its deplorable agricultural protection (the Corn Laws) and other remnants of old mercantilist protectionist measures in 1846. In its quest for this Liberal world order, Britain's ultimate weapon was its economic success based on a free-market/free-trade system; this made other countries realize the limitations of their mercantilist policies and start to adopt free (or at least freer) trade from around 1860. However, Britain was also greatly helped in its project by the works of its classical economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who theoretically proved the superiority of laissez-faire policy, in particular free trade.

…

According to Willy de Clercq, the European Commissioner for External Economic Relations during the early days of the Uruguay Round (1985-9): Only as a result of the theoretical legitimacy of free trade when measured against widespread mercantilism provided by David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and David Hume, Adam Smith and others from the Scottish Enlightenment, and as a consequence of the relative stability provided by the UK as the only and relatively benevolent superpower or hegemon during the second half of the nineteenth century, was free trade able to flourish for the first time [in the late nineteenth century].2 This Liberal world order, perfected around 1870, was based on: laissezfaire industrial policies at home; low barriers to the international flows of goods, capital and labour; and the macroeconomic stability, both nationally and internationally, which was guaranteed by the Gold Standard and the principle of balanced budgets.

…

Nowadays, some economists even believe that the Great Depression was caused primarily by these tariffs'. 3 The likes of Germany and Japan erected high trade barriers and also started creating powerful cartels, which were closely linked with fascism and these countries' external aggression in the following decades.4 The world free trade system finally ended in 1932, when Britain, hitherto its champion, succumbed to temptation and reintroduced tariffs. The resulting contraction and instability in the world economy, and then the Second World War, destroyed the last remnants of the first Liberal world order. After the Second World War, so the story goes, some significant progress was made in trade liberalization through the early GATT (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs) talks. However, dirigiste approaches to economic management dominated the policy-making scene until the 1970s in the developed world, and until the early 1980s in developing countries (as well as the Communist world until its collapse in 1989).

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 7 Apr 2004

The Contested Role of the State It is safe to say that politics in the twentieth century were heavily shaped by controversies over the appropriate size and strength of the state. The century began with a liberal world order presided over by the world’s leading liberal state, Great Britain. The scope of state activity was not terribly broad in Britain or any of the other leading European powers, outside of the military realm, and in the United States, it was even narrower. There were no income taxes, poverty programs, or food safety regulations. As the century proceeded through war, revolution, depression, and war again, that liberal world order crumbled, and the minimalist liberal state was replaced throughout much of the world by a much more highly centralized and active one.

Reaching for Utopia: Making Sense of an Age of Upheaval

by

Jason Cowley

Published 15 Nov 2018

’ * * * Blair says that he has never met Donald Trump, although he knows his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, the real estate multimillionaire. Trump’s venality, belligerence, isolationist rhetoric and narrow definition of the national interest has alarmed the Anglo-American foreign policy establishment, which considers Trump to be a clear and present danger to the rules-based liberal world order. The urgent challenge facing the West in an age of intensifying nationalism, great power rivalry and demagogic plutocracy will be to hold together the alliance structure that has defined the world for the past seventy years. Under Trump’s presidency, the political scientist Robert Kagan has written, the US is likely to retreat into ‘national solipsism’.

…

How does it feel to have spent three decades on the back benches pursuing various radical and fringe causes unconstrained by the usual career considerations or by the discipline of collective responsibility – only to find yourself in late middle age becoming the accidental leader of a great national political party at a time of profound crisis for the left? As Martin Jacques, the former editor of Marxism Today, put it to me, Corbyn has unlocked something long repressed on the left. His consistency, his uncompromising socialism and his hostility to American power and the liberal world order have inspired many who turned away from Labour after the Iraq War to re-engage with politics. He has awakened, too, the interest of young people who are angry about entrenched intergenerational inequalities of wealth. Why, in the era of the hipster beard, even the facial hair is working for him.

…

The speech made clear that her foreign policy would not be amoral or ethically neutral. Nor would it be ‘idealist’ or universalist, as Blair’s was. Rather, it would be cautiously ‘realist’: she reaffirmed Britain’s commitment to free trade, to multilateral institutions such as NATO and to the rules-based liberal world order, but conceded the limits of Western liberalism, which, she said, cannot be exported or imposed by military intervention. May and her advisers understand that liberal values are not absolutes but practices that evolve over a long time and can easily be disrupted, as is happening in Trump’s America.

Globalists

by

Quinn Slobodian

Published 16 Mar 2018

“Over, under and beside the state-political borders of what appeared to be a purely political international law between states,” he wrote, “spread a free, i.e. non-state sphere of economy permeating everything: a global economy.”44 Schmitt meant the doubled world as something negative, an impingement on the full exercise of national sovereignty. But neoliberals felt he had offered the best description of the world they wanted to conserve. Wilhelm Röpke, who taught in Geneva for nearly thirty years, believed that exactly this division would be the basis for a liberal world order. The ideal neoliberal order would maintain the balance between the two global spheres through an enforceable world law, creating a “minimum of constitutional order” and a “separation of the state-public sphere from the private domain.”45 In a lecture he delivered at the Academy of International Law at The Hague in 1955, Röpke emphasized the importance of the division while also pointing to its paradox.

…

He felt that adherence to the gold standard and the free movement of capital and goods had acted before 1914 as “a sort of unwritten ordre public international, a secularized Res Publica Christiana, which for that reason spread all over the globe,” resulting in a “political and moral integration of the world.”50 As one scholar points out, the system relied as much on “informal constraints, that is, extralegal standards, conventions and moral codes of behavior” as on national laws.51 In Röpke’s view, membership in international society was synonymous with being a responsible actor in the free market. The liberal world order, the heir of a Christian order, was defined as a system of formally ungoverned economic expectations and modes of interaction—it was a community of values, which individual economies could both join and leave, but which supranational institutions could not legislate into existence. Peripheral to Röpke’s account of the era before 1914 as the “glorious sunny day of the western world” was the fact that the nineteenth century was also the era of high imperialism, when much of the earth’s territory was partitioned among the European powers.52 What was to be done, then, in the postwar world, when both the religious basis of international society had been lost and the community of “the West” was splintered by decolonization?

…

Hayek, June 21, 1948, Hayek Papers, box 76. 21. W. H. Hutt, The Economics of the Color Bar (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964). 22. F. A. Hayek, “Internationaler Rufmord,” Politische Studien, special issue no. 1 (1978): 45. 23. On the escalation of criticism, see Ryan M. Irwin, Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). A Special Committee on Apartheid was formed in the UN in 1963. Roland Burke, Decolonization and the Evolution of International Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 60. 24. Thomas Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 124. 25.

Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism

by

Quinn Slobodian

Published 16 Mar 2018

“Over, under and beside the state-political borders of what appeared to be a purely political international law between states,” he wrote, “spread a free, i.e. non-state sphere of economy permeating everything: a global economy.” 44 Schmitt meant the doubled world as something negative, an impingement on the full exercise of national sovereignty. But neoliberals felt he had offered the best description of the world they wanted to conserve. Wilhelm Röpke, who taught in Geneva for nearly thirty years, believed that exactly this division would be the basis for a liberal world order. The ideal neoliberal order would maintain the balance between the two global spheres through an enforceable world law, creating a “minimum of constitutional order” and a “separation of the state- I n t r o d u ctio n 11 public sphere from the private domain.” 45 In a lecture he delivered at the Academy of International Law at The Hague in 1955, Röpke emphasized the importance of the division while also pointing to its paradox.

…

He felt that adherence to the gold standard and the f ree movement of capital and goods had acted before 1914 as “a sort of unwritten ordre public international, a secularized Res Publica Christiana, A W o r l d of Rac e s 155 which for that reason spread all over the globe,” resulting in a “political and moral integration of the world.”50 As one scholar points out, the system relied as much on “informal constraints, that is, extralegal standards, conventions and moral codes of behavior” as on national laws.51 In Röpke’s view, membership in international society was synonymous with being a responsible actor in the free market. The liberal world order, the heir of a Christian order, was defined as a system of formally ungoverned economic expectations and modes of interaction—it was a community of values, which individual economies could both join and leave, but which supranational institutions could not legislate into existence. Peripheral to Röpke’s account of the era before 1914 as the “glorious sunny day of the western world” was the fact that the nineteenth century was also the era of high imperialism, when much of the earth’s territory was partitioned among the European powers.52 What was to be done, then, in the postwar world, when both the religious basis of international society had been lost and the community of “the West” was splintered by decolonization?

…

Hayek, June 21, 1948, Hayek Papers, box 76. W. H. Hutt, The Economics of the Color Bar (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964). F. A. Hayek, “Internationaler Rufmord,” Politische Studien, special issue no. 1 (1978): 45. On the escalation of criticism, see Ryan M. Irwin, Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). A Special Committee on Apartheid was formed in the UN in 1963. Roland Burke, Decolonization and the Evolution of International Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 60. Thomas Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 124.

The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order

by

Bruno Macaes

Published 25 Jan 2018

Significantly, even when the European Union expresses the wish to treat Russia as an equal partner this means something entirely different from what the Russian leadership understands by it. For Europeans it means that Russia will subscribe to the same values and rules that are accepted in Europe, something notably distinct from what Moscow actually demands: sharing the power to create or set the rules at the heart of the world order.20 Russia does not want to replace the liberal world order with a world without rules, but it does believe that such a world is the natural state of mankind and, therefore, that chaos is only to be avoided by the creative exercise of power by a strong sovereign. This is the case for international affairs no less than for domestic politics. Chaos is never completely left behind.

…

What was remarkable about the Brexit referendum was that the country which had invented free trade and taken it to the four corners of the world was now refusing to be part of the largest and freest economic bloc ever created. As for Trump, he has come to symbolize a precipitous retreat from the previous American foreign policy consensus. At times he seems to want to jettison the existing liberal world order and replace it with something else, defined around a strong national idea and appealing to a world of cut-throat competition. He has criticized a political culture that prizes the diffusion of power, in the belief that without a strong state, citizens will have no one to defend them against other countries.

The Deluge: The Great War, America and the Remaking of the Global Order, 1916-1931

by

Adam Tooze

Published 13 Nov 2014

A figure such as Ludendorff was under no illusion that his grand visions of the total redesign of Eurasia were expressions of traditional statecraft.49 He justified the scale of his ambition precisely on the basis that the world was entering a new and radical phase, the ultimate or the penultimate phase in a final global struggle for power. Men like these were no exponents of any kind of ‘ancien régime’. They were often highly critical of traditionalists who in the name of balance and legitimacy shrank from seizing the historic opportunity. Far from being exponents of the old world the most violent antagonists of the new liberal world order were themselves futuristic innovators. They were not, however, realists. The commonplace distinction between idealists and realists concedes too much to Wilson’s opponents. Though Wilson may have been humiliated, the imperialists also found themselves on the back foot. Already during the war the problems inherent in any truly grandiose programme of expansion had become amply apparent.

…

The suspicion of bad faith hanging over Berlin had the effect both of making the Bolsheviks appear as victims and of handing the initiative back to the Western Powers. In January 1918, in response to the German-Bolshevik talks at Brest, both Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson felt obliged to make powerful statements of the liberal world order they envisioned for the post-war period. Of the two statements it was Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Points manifesto that would echo around the world. But far from challenging Lenin and Trotsky, as Cold War legend would have it, Wilson chose to conciliate them. In the process, by portraying Lenin and Trotsky as potential partners in a democratic peace and a unitary ‘Russian people’ as the victim of German aggression, Wilson helped to consolidate the black legend of Brest.

…

And the willingness of world opinion not only to give far greater attention to Wilson’s 14 Points, but to read into his text phrases that Lloyd George rather than Wilson had actually uttered, was a harbinger of things to come. But it should not be allowed to obscure the point that if the leaders of the British Empire emerged in a confident mood in November 1918, it was because they felt they had secured the foundations of the empire as a key pillar of the emerging, liberal world order. 10 The Arsenals of Democracy France, Britain and Italy contained the crisis of political legitimacy that felled Russia and would soon tear the Central Powers apart. But what kept the populations of the Entente off the streets and drove their armies across the line was a remarkable economic effort.

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 26 Dec 2007

According to this history, globalization has progressed over the last three centuries in the following way:6 Britain adopted free-market and free-trade policies in the 18th century, well ahead of other countries. By the middle of the 19th century, the superiority of these policies became so obvious, thanks to Britain’s spectacular economic success, that other countries started liberalizing their trade and deregulating their domestic economies. This liberal world order, perfected around 1870 under British hegemony, was based on: laissez-faire industrial policies at home; low barriers to the international flows of goods, capital and labour; and macroeconomic stability, both nationally and internationally, guaranteed by the principles of sound money (low inflation) and balanced budgets.

…

The world free trade system finally ended in 1932, when Britain, hitherto the champion of free trade, succumbed to temptation and itself re-introduced tariffs. The resulting contraction and instability in the world economy, and then, finally, the Second World War, destroyed the last remnants of the first liberal world order. After the Second World War, the world economy was re-organized on a more liberal line, this time under American hegemony. In particular, some significant progress was made in trade liberalization among the rich countries through the early GATT (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs) talks.

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 4 Jul 2007

According to this history, globalization has progressed over the last three centuries in the following way.6 Britain adopted free-market and free-trade policies in the 18th century, well ahead of other countries. By the middle of the 19th century, the superiority of these policies became so obvious, thanks to Britain’s spectacular economic success, that other countries started liberalizing their trade and deregulating their domestic economies. This liberal world order, perfected around 1870 under British hegemony, was based on: laissez-faire industrial policies at home; low barriers to the international flows of goods, capital and labour; and macroeconomic stability, both nationally and internationally, guaranteed by the principles of sound money (low inflation) and balanced budgets.

…

The world free trade system finally ended in 1932, when Britain, hitherto the champion of free trade, succumbed to temptation and itself re-introduced tariffs. The resulting contraction and instability in the world economy, and then, finally, the Second World War, destroyed the last remnants of the first liberal world order. After the Second World War, the world economy was re-organized on a more liberal line, this time under American hegemony. In particular, some significant progress was made in trade liberalization among the rich countries through the early GATT (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs) talks.

The WikiLeaks Files: The World According to US Empire

by

Wikileaks

Published 24 Aug 2015

At the heart of postwar US policy-making is the doctrine of liberal internationalism. Pioneered by Woodrow Wilson, and embellished by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, this doctrine is generally understood as the justification of military and other interventions by the US if they help produce a liberal world order: a global system consisting of liberal-democratic nation-states, connected by more or less free markets and ruled by international law. In this world-view, the goal of achieving a liberal world system trumps the commitment to state sovereignty. The US sees itself as the natural vanguard of such a global order, as well as the chief bearer of any right to suppress state sovereignty in the pursuit of liberal goals.

…

The vagueness of this definition of torture is not simply a matter of unfortunate phrasing in the convention, but derives from two facts external to the text. The first is that “torture” is inherently a prescriptive, normative term and, like any term in political language, is contested. The second is to do with the legal system itself. The US empire is based on a liberal world order under law. But these norms pull in opposing directions. The right to be free from torture comes into conflict here with the right of states to punish. This partially explains why, even though the American empire has always tortured, it has never had a coherent position on torture—those who torture have always had to confront those for whom torture is anathema by America’s own standards.

…

Indeed, one of the reasons why so much information has been disclosed is a struggle between factions of the US state, in which many argued that torture was counterproductive. But there has been no final resolution of this struggle, and the United States has still not ceased to torture: it seems likely that, as long as America is an empire, it will torture again.118 But that bind, between the normative claims attached to America’s stewardship of a liberal world order and the harsh realities of military domination, is one that has repeatedly caught its leaders out. Even as they authorize torture, they must seek to define it out of existence. This eBook is licensed to Edward Betts, edward@4angle.com on 04/01/2016 3. War and Terrorism Armies march, but they must have a destination.

Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

by

Adom Getachew

Published 5 Feb 2019

Asli Bâli and Aziz Rana, “Constitutionalism and the American Imperial Imagination,” University of Chicago Law Review 85 (March 2018): 257–92. 41. Martin Staniland, American Intellectuals and African Nationalists, 1955–1970 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), 76–78; Ryan M. Irwin, Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 76. 42. Eliga H. Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 1–2. 43. Ibid., 211. 44. Rana, Two Faces of American Freedom, 134–35. 45. In an examination of why early postcolonial federations—the United States, Australia, and Canada—succeeded while twentieth-century versions failed, Thomas Franck identifies the absence of imperial expansion in the latter as an important contributing factor.

…

International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty. The Responsibility to Protect: Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 2001. Irwin, Ryan M. Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. ——— —. “Sovereignty in the Congo Crisis.” In Decolonization and the Cold War: Negotiating Independence, edited by Leslie James and Elisabeth Leake, 203–18. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015. Isaac, Jeffrey C. “A New Guarantee on Earth: Hannah Arendt on Human Dignity and the Politics of Human Rights.”

The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Metropolitan Elite

by

Michael Lind

Published 20 Feb 2020

In Europe, this means “Euroskepticism” and “sovereigntism,” the assertion of the sovereignty of the democratic nation-state and the democratic national legislature against the power of the transnational bureaucracies of the European Union. In the United States, the equivalent is the Trump administration’s transactional approach to treaties and international organizations, which tend to be venerated by technocratic neoliberals as pillars of a “liberal world order.” In the economy, today’s populist leaders tend to be economic nationalists, opposing global labor arbitrage policies of offshoring and mass immigration, which the overclass establishment claims are both inevitable and beneficial. Populist constituencies include many workers in manufacturing districts hit hard by foreign competition, including China’s subsidized “social dumping,” and others who view immigrants as competitors for jobs, public services, or status.

Global Governance and Financial Crises

by

Meghnad Desai

and

Yahia Said

Published 12 Nov 2003

The supporters of new forms of regulation believe, however, that the neo-liberal view of regulation and state action, which has been dominant in the last three decades, is far too pessimistic about the possibilities of building on co-operation between states to create transnational regimes which can effectively regulate financial markets. They argue that unless steps are taken to control the effects of deregulated financial markets on employment and investment in those countries most susceptible to financial crisis, the future of a liberal world order will be put at risk, because pressure for protectionist and isolationist economic policies will revive, with grave consequences for world prosperity and world peace (Smith 2000). Without minimising the difficulties of securing the required co-operation from states to establish effective regulatory agencies, some economists believe that the past performance of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) gives some grounds for optimism that its remit could be extended (Eatwell 1999).

War for Eternity: Inside Bannon's Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers

by

Benjamin R. Teitelbaum

Published 14 May 2020

It scared some of them, and they struggled to believe it: in a poignant analogy, one white nationalist writer compared the sensation to that of an unattractive young man who grandly rejects future romance rather than be rejected himself, only to cower when against all odds opportunity knocks on his door one day. Could it really be true, the end of the liberal world order—the dying gasps of the tiger? Dare they open themselves up to hope? Might the radical right have become attractive instead of a pariah—a milieu that serious, powerful people want to be on good terms with and treat as an asset? Michael Bagley seemed to think so. He knocked; Jason planned to answer

Corbyn

by

Richard Seymour

Now that Corbyn has, by depriving the Conservatives of their majority and setting Labour up for a future win, proved the critics wrong, what needs to be rethought? III The world, for a start. In the past few decades, it has been taken for granted among the majority of journalists and politicians that something miraculous was taking place: globalisation. The world was converging, under the relatively benign tutelage of Washington, toward a liberal world order. With the vast global expansion of trade availed by the global rollback of capital controls and tariffs, a series of institutions of global governance sprang up, as well as a patchwork of regional trading alliances rolling out property rights, and rolling back barriers to trade such as public ownership, and environmental or labour protections.

How Long Will Israel Survive Threat Wthn

by

Gregg Carlstrom

Published 14 Oct 2017

The vote drew the requisite condemnations from the international community (“deeply concerned”, in the words of John Kirby, the State Department spokesman). But it came at a fortuitous time for the Netanyahu government, days after Trump’s election, while the West was preoccupied with the seeming demise of the liberal world order. Then the attorney general piped up again, warning that any effort to authorize Amona would undermine the Supreme Court and the separation of powers. So in another bizarre twist, the language related to Amona was dropped from the bill. What began as an effort to keep forty families in their homes had metastasized into a law that “legalized” nearly 4,000 illegal residences—but the original forty would still be evicted.

Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War

by

Raj M. Shah

and

Christopher Kirchhoff

Published 8 Jul 2024

And he brought up how free trade and open borders, long assumed to draw global talent to the U.S. and Europe, had now begun to work in reverse, with foreign Ph.D.s and post-docs returning to Beijing or Shanghai. The last line of Chris’s paper summed up how the tide had turned: “Technology—once an unmistakable comparative advantage of the liberal world order—now almost equally empowers those who seek its undoing.” McMaster had traveled from Washington with Dr. Nadia Schadlow, the national security advisor’s lead strategist. Schadlow, a brilliant scholar of the Cold War, was responsible for writing the Trump administration’s national security strategy, the plan the U.S. would use to counter China.

Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take It Back

by

Oliver Bullough

Published 5 Sep 2018

Corruption has become so widespread that whole countries are unable to tax their wealthiest residents, meaning only those least able to pay are forced to support the government. This undermines democratic legitimacy, and angers the people who live under such governments. For people who believe in a liberal world order, there is no upside to this. Commentators from all sides of politics have expressed concerns about the effect of inequality on the fabric of society in the United States, where the share of wealth held by the richest 1 per cent of the country rose from a quarter to two-fifths between 1990 and 2012.

What's Left?: How Liberals Lost Their Way

by

Nick Cohen

Published 15 Jul 2015

You no more have to suggest how to improve their lives, than an angry customer has to suggest ways to repair faulty goods. We no longer believe in internationalism and fraternity. Sticking by your comrades is as absurd a notion as staying loyal to Microsoft when Apple has a better product. Join us, and revel in the righteousness of your solipsistic anger. Nothing the neo-liberal world order produced suited the consumer society as well as the thinkers who purported to oppose it. It took one more war and one more professor for protest’s new brand to go global. CHAPTER FIVE Tories Against the War Douglas, Douglas, you would make Neville Chamberlain look like a warmonger.

The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalization

by

Michael O’sullivan

Published 28 May 2019

Many social trends—such as obesity, the overuse of social media, and the reemergence of developed-world poverty—are raising the level of concern that human-specific factors, to put it as dryly as that, are being neglected. In politics, cracks are appearing in the system as voters begin to act, gravitating toward radical parties and sanctioning extreme events. Geopolitically, the idea of the liberal world order is under attack, and China is now a clear rival to the United States. American foreign policy is seen as aggressive, whereas it was once seen as benevolent. More change will come. Another recession or geopolitical crisis would only compound the sense of confusion. We are still simply at the early part of the paradigm shift, when the existing or consensual order is crumbling and slowly being rejected.

The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities

by

John J. Mearsheimer

Published 24 Sep 2018

Those alternative accounts, in other words, do not emphasize the importance of inalienable rights, which is the liberal explanation for this purported phenomenon. In chapter 7, I assess those particular attributes of democracies that are said to prevent war between liberal democracies. 5. Quoted in G. John Ikenberry, “Liberal Internationalism 3.0: America and the Dilemmas of Liberal World Order,” Perspectives on Politics 7, no. 1 (March 2009): 75. 6. Michael W. Doyle, “Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs,” part 2, Philosophy and Public Affairs 12, no. 4 (Fall 1983): 324. Also see Doyle, “Liberalism and World Politics,” pp. 1156–63. 7. Quoted in Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), p. 111.

Destined for War: America, China, and Thucydides's Trap

by

Graham Allison

Published 29 May 2017

Acknowledging that the “lines between [civilizations] are seldom sharp,” Huntington argued that they are nonetheless “real.”12 Huntington by no means ruled out future violent conflicts between groups within a common civilization. His point, rather, was that in a post–Cold War world, civilizational fault lines would not dissolve in a global convergence toward liberal world order—as one of Huntington’s former students, the political scholar Francis Fukuyama, had predicted in his 1989 article “The End of History?”13—but become more pronounced. “Differences do not necessarily mean conflict, and conflict does not necessarily mean violence,” Huntington allowed. “Over the centuries, however, differences among civilizations have generated the most prolonged and the most violent conflicts.”14 Huntington was keen to disabuse readers of the Western myth of universal values, which he said was not just naive but inimical to other civilizations, particularly the Confucian one with China at its center.

Super Continent: The Logic of Eurasian Integration

by

Kent E. Calder

Published 28 Apr 2019

China’s distributive globalism, focused on providing connectivity infrastructure, is thus advancing into the vacuum created by Trump’s abdication of American global leadership, accelerating the coming of a Global Crossover Point, under which a Beijing consensus gradually and quietly subverts the already eroding legitimacy of the liberal world order, even as Chinese leadership ritually affirms many of its central tenets. In Conclusion The core institutions of the contemporary global political economy have proven to be remarkably durable. The most basic ones—the IMF and the World Bank—were born at the Bretton Woods conference of July 1944.

Economic Dignity

by

Gene Sperling

Published 14 Sep 2020

An all-Republican Congress for his last six years in office, however, made major reform a legislative impossibility. The core motivation for bringing China into the WTO was far less related to economics and far more part of a broader post–Cold War strategy aimed at bolstering the global rule of law and binding China to the liberal world order. Nonetheless, Clinton effectively held up the agreement for many months in part to secure an “anti-surge” provision to block or slow down imports if they were having severe impacts on jobs without having to prove any unfair trade practices. Had Al Gore followed Clinton as president, there is little question that the anti-surge provision would have been a powerful tool used again and again to both protect manufacturing communities and send a strong message to China.

How to Be a Liberal: The Story of Liberalism and the Fight for Its Life

by

Ian Dunt

Published 15 Oct 2020

Trump had already shown that the international rules didn’t matter to him. He had sent a signal to every other nationalist that they could do whatever they wanted. Simply by virtue of acting, he was creating the world he wanted. The size of the US, in terms of trading clout and political authority, meant that any action it took became a new norm. The liberal world order was falling down. Orbán was undermining the EU from within. Britain was undermining it from without. And Trump was humbling the WTO. Decades of delicate construction work were being dismantled. Inside these countries, the same process was undermining the institutions which kept executive power in check.

The end of history and the last man

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 28 Feb 2006

It would therefore appear that we will not get beyond the nation-state any time soon as the fundamental source of legitimate democratic authority. In place of global government, we will have to be satisfied with global governance, that is, partial international institutions that promote collective action among nations and that create some degree of accountability among them. A liberal world order that is both just and feasible would have to be based not on a single, overarching global institution, but rather on a diversity of international institutions that could organize themselves around functional issues, regions, or specific problems. This kind of world order is in the process of being created, but there is still a great deal of productive work that can be done in this area.

Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order

by

Colin Kahl

and

Thomas Wright

Published 23 Aug 2021

He rejected the notion that the United States should try to lead the international community, and believed other countries were ripping the American people off. Whereas his predecessors saw the post–World War II alliances and international institutions Washington had created as an integral part of American power, Trump saw the so-called liberal world order as rigged against the United States. He pulled out of international agreements, including the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Iran nuclear deal, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement. He levied tariffs on America’s closest allies while treating U.S. treaty commitments to NATO and South Korea like protection rackets.

Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism

by

Pippa Norris

and

Ronald Inglehart

Published 31 Dec 2018

His ‘America First’ rhetoric has signaled US withdrawal from multilateral agreements and alliances, such as the TPP, the Paris climate accord, the Iran accord, and America’s leadership role of the free world, as well as tearing up the State Department’s investment in democracy promotion, human rights, and the United Nations. President Trump has sharply attacked the G7, NATO, and the European Union, breaking diplomatic norms and deeply undermining the pillars of the liberal world order. He has attacked and sought to destabilize some of America’s most stalwart allies, including leaders in Canada, Germany, and the UK, while expressing warm admiration for many authoritarians around the world, such as in Russia, China, North Korea, the Philippines, and Saudi Arabia. Yet his administration has also maintained several foreign policies; for example, the Pentagon has signaled the continuing engagement of troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by

Alex Zevin

Published 12 Nov 2019

The oil price quadrupled after the Yom Kippur War, and a new word was coined to describe the effects this had down the decade: stagflation. Perhaps most alarming of all, these very developments seemed to strengthen the Soviet Union, which gained hard currency from surging oil prices and a freer hand abroad after America’s geopolitical setback in Southeast Asia.63 At this moment of apparent crisis for the American-led liberal world order, Andrew Knight became editor of the Economist. In contrast to past occupants of this position, Knight found it more difficult to get hired in the first place than to obtain the top job. On his second try in 1964, Brian Beedham thought him ‘brooding’ but ‘with the large advantage of not being a smooth young man’, and ‘worth bearing in mind’.

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by

Anu Bradford

Published 25 Sep 2023

Democracy: The Greatest Game 4–5 (2020), https://hfxchinahandbook.s3.amazonaws.com/EN_HFX+China+Handbook_FINAL_WEB.pdf. 98.See Cohen & Fontaine, supra note 94. 99.See id. 100.See China Strategy Group, Asymmetric Competition: A Strategy for China & Technology: Actionable Insights for China & Technology 3–4, 17, 26–27 (2020), https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/20463382/final-memo-china-strategy-group-axios-1.pdf. See generally Erik Brattberg & Ben Judah, Forget the G-7, Build the D-10, Foreign Pol’y (June 10, 2020), https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/10/g7-d10-democracy-trump-europe/; Ash Jain, Like-Minded and Capable Democracies: A New Framework for Advancing a Liberal World Order (Council on Foreign Rels. Working Paper, Jan. 2013), https://cdn.cfr.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2012/11/IIGG_WorkingPaper12_Jain.pdf; Anja Manuel, The Tech 10: A Flexible Approach for International Technology and Governance, in Domestic and International (Dis)Order: A Strategic Response 71 (Leah Bitounis & Niamh King eds., 2020), https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Foreign-Policy-2021-ePub_FINAL.pdf. 101.See Adrian Shabaz, The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism, Freedom House (2018), https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism. 102.See Jon Bateman, Biden Is Now All-In on Taking Out China, Foreign Pol’y (Oct. 12, 2022), https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/12/biden-china-semiconductor-chips-exports-decouple/. 103.See The Summit for Democracy, U.S.

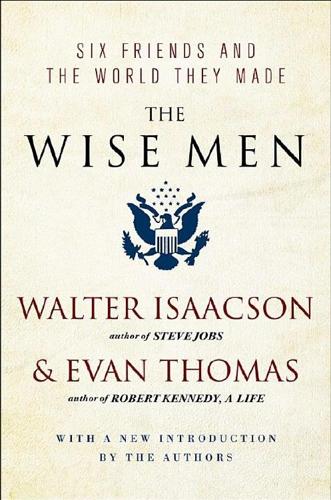

The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made

by

Walter Isaacson

and

Evan Thomas

Published 28 Feb 2012

The unchecked interventionist spirit resulted in unwise political and military involvements that the nation, by the end of the Vietnam War, was neither willing nor able to keep. Their policies also did nothing to alleviate, and perhaps even exacerbated, the evil they were designed to combat: Moscow’s paranoia, expansionism, and unwillingness to cooperate in a liberal world order. Their reaction to the Soviet threat, Walter Lippmann has charged, “furnished the Soviet Union with reasons, with pretexts, for an iron rule behind the iron curtain, and with the ground for believing what Russians are conditioned to believe: that a coalition is being organized to destroy them.”