The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

by

Benjamin H. Bratton

Published 19 Feb 2016

The Stack, as a whole, structures the City layer through the consolidation of urban nodes into megacities and also through the consolidation of both public and private urban systems in megastructures. We'll find that instead of heterogeneous and open interfacial platforms, for their own footprints Cloud platforms prioritize instead urban-scale walled gardens. The megastructure provides a bounded total space in which architectural and software program can be composed by complete managerial visualization; for it, the border, the gate, and the wall bend into closed loops containing vast interiors, sometimes in pursuit of utopian idealization and isolation. The megastructure is an enclave within the city that also holds a miniaturized city within itself, and so the specific and different terms of that miniaturization are the vocabularies of differing utopian agendas, whether explicit or suppressed.

…

The City layer of The Stack itself operates as a massively distributed megastructure and draws on, however obliquely and opportunistically, the reservoir of speculative, even utopian megastructural design projects of years past (built and unbuilt), even realizing them after the fact with a sometimes perverse inversion of their original intent. As discussed in the Earth chapter, in and around the years when the first photographs of Earth were taken from space, speculative architectural design was inspired by the visual scale of the whole Earth as a comprehensive site condition and spawned scores of now canonical megastructure projects. Many proposed total utopian spaces (islands cut off from the rest of the world, per Fredric Jameson's discussion of the utopian genre in science fiction), including, as already mentioned, OMA's Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture (1972) and Superstudio's planet-spanning Continuous Monument (1969), while others sought the utopian through the maximal perforation of boundaries by ludic interfaces and absolute grids, including No-Stop City (1969) or Constant's New Babylon (1959–1974).

…

In anticipation of the ultimate footprint and expression of the Apple Cloud platform into the City layer of The Stack, we also note that the integration of the closed megastructural platform model is now planned to include Foster's refresh and redesign of Apple's most public terrestrial presence, its hundreds of brand retail stores. That Foster's office would become the house architect of the Apple platform's human-facing earthly permeation suggests that his acumen with megastructures serves to organize the physical expression of the Apple Cloud Polis's City layer more generally. Apple has invested in the biological extravagance of the iconic megastructure in ways that the other platforms have not, including its resolute ambition to utopian totality.

Vertical: The City From Satellites to Bunkers

by

Stephen Graham

Published 8 Nov 2016

Skywalk/Skytrain/Skydeck: Multilevel Cities 1See Antonio Sant’Elia, Luciano Caramel and Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, Rome: Rizzoli International Publications, 1988. 2Antonio Sant’Elia, Architettura Futurista, Milan: Galleria Fonte d’Abisso, 1984 [1914]. 3Ibid, p. 280. 4See Jean-Louis Cohen and Hubert Damisch, Scenes of the World to Come: European Architecture and the American Challenge, 1893–1960, Paris: Flammarion, 1995. 5See Peter Cook and Michael Webb, Archigram, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999. 6Japanese architect Maki Fumihiko defined a ‘megastructure’ in 1964 as a ‘large frame in which all the functions of a city are housed’. Megastructures had, he argued, ‘been made possible by present day technology’, Maki Fumihiko, Investigations in Collective Form, St Louis: Washington University Press, 1964, p. 1. 7Hideo Obitsu and Nagase Ichirou, ‘Japan’s Urban Environment: The Potential of Technology in Future City Concepts’, in Gideon Golany, Keisuke Hanaki and Osamu Koide, eds, Japanese Urban Environment, Oxford: Elsevier Science, 1988, pp. 324–36; and Zhong-Jie Lin, ‘From Megastructure to Megalopolis: Formation and Transformation of Mega-Projects in Tokyo Bay’, Journal of Urban Design 12:1, 2007, pp. 73–92. 8Cook and Webb, Archigram.

…

Crucial here was the shift from one all-purpose system of roads to a labyrinth of single-purpose ones, organised three-dimensionally within the huge new concrete megastructures of the city. (Critics suspected from the outset that the dominating motivation behind the idea of raised walkways in the UK was simply to remove people from the accelerating momentum of proliferating vehicles.) City centres would thus be progressively re-engineered into huge multifunctional and multilevel containers12: three-dimensional megastructures designed using the latest modernist and functionalist concepts to ‘heap up’ housing, commerce, retailing and leisure while providing enough space for the mass-automobile society.

…

Megastructures had, he argued, ‘been made possible by present day technology’, Maki Fumihiko, Investigations in Collective Form, St Louis: Washington University Press, 1964, p. 1. 7Hideo Obitsu and Nagase Ichirou, ‘Japan’s Urban Environment: The Potential of Technology in Future City Concepts’, in Gideon Golany, Keisuke Hanaki and Osamu Koide, eds, Japanese Urban Environment, Oxford: Elsevier Science, 1988, pp. 324–36; and Zhong-Jie Lin, ‘From Megastructure to Megalopolis: Formation and Transformation of Mega-Projects in Tokyo Bay’, Journal of Urban Design 12:1, 2007, pp. 73–92. 8Cook and Webb, Archigram. See Reyner Banham’s definitive Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, London: Harper Collins, 1976. 9Ibid., p. 10. 10Aileen Tatton-Brown, and William Tatton-Brown, ‘Three-Dimensional Town Planning’, Architectural Review 40, September 1941, p. 83. 11Newcastle City Council, ‘Central Area Redevelopment Plan’, Newcastle, 1963, p. 12. 12The quote comes from John Gold, ‘The Making of a Megastructure: Architectural Modernism, Town Planning and Cumbernauld’s Central Area, 1955–75’, Planning Perspectives 21:2, 2006, p. 113. 13Institution of Municipal Engineers, Town Centre Redevelopment, Proceedings of the Institution’s Convention, London: Institution of Municipal Engineers, 1962. 14London County Council, The Administrative County of London: Development Plan First Review, London: London County Council, 1960, p. 169.

Supertall: How the World's Tallest Buildings Are Reshaping Our Cities and Our Lives

by

Stefan Al

Published 11 Apr 2022

For some people, this may be terrifying, maybe even leading them to cling to the ground. From an urbanistic perspective, however, it is unprecedented. More than just a building, this is a vertical city, where tens of thousands of people can live, work, and play in one single complex, without ever having to leave. The world of megastructures is fundamentally different from the world of regular buildings. Decades before megastructures became a reality, avant-garde architects like Frank Lloyd Wright obsessed over structures this size. It wasn’t all about height, however. Some toiled over highly efficient circulation, like the Italian futurist Antonio Sant’Elia, who in 1914 envisioned La Città Nuova (“The New City”) as an array of monolithic skyscrapers articulated with snaking lifts, railways, and aerial bridges.

…

Five years later, the city of Chengdu, in China, constructed a building that is bigger and perhaps even bolder: New Century Global Center is a shopping mall with offices, several hotels, an ice-skating rink, a Mediterranean village, and an artificial beach enlivened by a 500-foot-long screen displaying sunrises and sunsets. What stopped us seventy years ago from erecting these megastructures, and why are we building them today? It wasn’t the geometry of Wright’s proposal. Surprisingly, both the Jeddah Tower and the Burj Khalifa resemble Wright’s vision. The towers have a footprint shaped like a tripod, from which the building rises and tapers to a spire, giving it the silhouette of a minaret.

…

We then built it with concrete-filled steel tubes, instead of Shukhov’s bare steel beams, creating a stronger structure. We embedded hundreds of sensors into the tower, allegedly the world’s first structural health-monitoring system, making sure it would continue to stand. Technological advances alone do not explain the first hyperboloid megastructure. After all, who needs a TV-tower antenna in the age of cable and satellite? Almost as soon as our building was completed, our tower was no longer the world’s only hyperboloid structure breaking the Shukhov barrier. In 2011, the hyperboloid Tower of Fortune was completed in Zhengzhou at 1,273 feet (388 meters).

Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain

by

John Grindrod

Published 2 Nov 2013

‘A Natural Evolution of Living Conditions’: Newcastle Gets the System Building Bug (1959–69) 5. ‘A Contemporary Canaletto’: How Office Blocks Transformed our Skyline (1956–75) 6. ‘A Village With Your Children in Mind’: Span and the Hippy Dreams of New Ash Green (1957–72) 7. ‘A Veritable Jewel in the Navel of Scotland’: Cumbernauld’s Curious Megastructure (1955–72) Part 3: No Future 1. ‘A Pack of Cards’: Tower Block Highs and Lows (1968–74) 2. ‘A Terrible Confession of Defeat’: Protests and Preservation (1969–79) 3. ‘As Corrupt a City as You’ll Find’: Uncovering the Lies at the Heart of the Boom (1969–77) 4. ‘A Little Bit of Exclusivity’: Milton Keynes, the Last New Town (1967–79) 5.

…

Even Buchanan was moved to speculate that ‘perhaps some kind of individual jet-propulsion unit will eventually be developed’ though, practical as ever, he was one of the first to think through the issues around jet packs: ‘The problems of weather, navigation, air space and traffic control appear so formidable that it may be questioned whether such a device would ever be practical for mass use.’63 The Smithsons, naturally, were less cautious, writing in 1970 that ‘we may find that a revolutionised railway system, or the use of helicopters for local high speed passenger services, will make our proposed 120 foot wide “ring roads” ridiculous.’64 So what would Britain look like by the impossibly distant year 2000? Sixties planners did their best to imagine. One of the most ambitious schemes was the superhuman speculative shopping megastructure named High Market. It had been sponsored by the glass manufacturers Pilkington Brothers, and drawn up by yet another husband and wife team, Gordon and Eleanor Michell (who had advised Colin Buchanan while he was writing Traffic in Towns). The Michells imagined an artificial ridge stretching between two hills in the countryside near Dudley in the Midlands, creating what was effectively a dam of shops.

…

‘The ideal town,’ wrote Jellicoe, ‘would seem to be one in which the traffic circulation were piped like drainage and water; out of sight and out of mind, to go as fast as it likes, to smell as it wants, and to make noises.’67 The designs and models he produced looked like a cross between postwar Plymouth’s town centre and Tron. What was the best thing about it? ‘It can be extended indefinitely,’ enthused Jellicoe.68 The countryside may not have become home to High Market-style megastructures, but American-style out-of-town malls and European-style hypermarkets did begin to appear. Sadly lacking space-age transport infrastructure, these malls would instead continue to rely heavily on the car. The early sixties planners would no doubt be shocked that their futuristic plans for city centres never came to pass, and by the ongoing ad hoc sprawl of car-dependent trading estates.

Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities

by

Witold Rybczynski

Published 9 Nov 2010

The first neighborhood center, Lake Anne Village, opened in 1965 and garnered national attention for its modernist architecture (designed by architects Julian H. Whittlesey, William J. Conklin, and Cloethiel Woodward Smith) and its picturesque lakeside plan, said to be influenced by the Italian seaside town of Portofino.13 However, for the main town center, Whittlesey and Conklin designed a conventional sixties megastructure, with all the functions in what was effectively a single building. Simon objected that this solution was too expensive, and too difficult to implement in phases, and suggested a more traditional approach using streets and sidewalks.14 Instead, the planners, some of whom had been involved in the design of Radburn, proposed an all-pedestrian scheme, with car traffic and parking on a lower level.

…

The new projects generally downplayed these constraints and concentrated on architectural form: Foster designed an unusual pair of connected skyscrapers; the team of Meier, Eisenman, Holl, and Gwathmey produced a striking composition of five identical towers; Libeskind placed his buildings around a huge memorial excavation; and the team that included Foreign Office Architects and UNStudio proposed a colossal megastructure of a type that had never been built before—and was, perhaps, unbuildable. Although architecture critics generally praised the results, not everyone was pleased. “It is like putting lipstick on a hog,” complained Yaro. “Nothing has changed except you have a lot of fancy architects on this go-round.

…

The ninety-two-acre project was planned and coordinated by the Battery Park City Authority, a public-benefit corporation created by New York State in 1968, about the same time as the Penn’s Landing Corporation came into being. As in Philadelphia, the first designs for Battery Park City were ambitious megastructures on superblocks, and they suffered the same fate. The project took a different turn in 1979, when the Authority commissioned Alexander Cooper and Stanton Eckstut to create a plan that could be implemented by several different developers in successive phases. Cooper and Eckstut extended the uneven Lower Manhattan street grid into the site, creating small parcels of land that could be filled in with medium- and high-rise apartment blocks.* Like Reston Town Center, Battery Park City was designed to grow piecemeal, building by building, with individual projects financed and built by different developers, in response to changing market demand, but following the architectural guidelines of the master plan.

Norman Foster: A Life in Architecture

by

Deyan Sudjic

Published 1 Sep 2010

It is also the problem of the architect, as planners and developers have failed to rebuild our cities. They are obsessed with numbers (people, money, acreage, units, cars, roads, etc) and forget life itself and the spirit of man,’ Rudolph wrote in his unusually discursive brief for the students. Their proposal took the form of a megastructure, stepping towards the existing campus buildings. A continuous series of buildings, running one into another, was organised around a spine of lower structures that housed car parks, and cafés, with the laboratories radiating off it. What is most striking about Yale in Rudolph’s time is that he produced students with wildly divergent outlooks on architecture.

…

Their campuses were conceived as self-contained worlds that demonstrated new ways to live and work, reflected in an architecture that was more adventurous than would be possible on the outside. Lasdun designed a remarkably powerful, even ruthless scheme that created a continuous wall of concrete structures, like a set of linked stepped pyramids, perhaps the most ambitious attempt at that feverish, half-dystopian, biggest-of-the-big architectural idea of the 1960s – building a megastructure in Britain. Tradition had been abolished. The University of East Anglia wall, backed by an elevated walkway, contains student residences, as well as laboratories, teaching spaces, and classrooms. It has the massive presence of an aircraft carrier beached in a wheat field. As an expression of a single, ruthless architectural will, it would have attracted attention anywhere.

…

To avoid that impression, he wanted Lasdun’s endorsement. Foster conceived of the Sainsbury Centre as a gleaming silver tube, turning away from the campus to look out over the green landscape, and a lake. Foster’s building seems barely to touch the ground; it is tethered to Lasdun’s concrete megastructure by the most tenuous of umbilical cords, a high-level glass walkway. It penetrates the tube at an oblique angle, and then descends into the gallery by way of a sculptural spiral staircase with no visible means of support. It was typical of Foster’s approach at the time. He abolished design problems – the joint between two materials, for example, or how to make a formal approach to a building – by avoiding them altogether.

A Burglar's Guide to the City

by

Geoff Manaugh

Published 17 Mar 2015

It’s a bit like climbing up into an airport control tower, and in some ways, that’s exactly what you’ve done. The building’s landing deck is the size of an aircraft carrier: a vast meadow of painted concrete baking in the Southern California sun. This makes the Air Support Division’s HQ a kind of beached warship in the heart of the city. The inner sanctum of this megastructure is a dense sequence of small corridors and stairways, and even this at times resembles the guts of a military ship. Helicopter timetables and safety-procedure posters are tacked up on the walls, and an erasable whiteboard keeps track of who is flying what and when. I have never seen the facility crowded, although there are an awful lot of chairs, as if waiting for some future gathering.

…

He would describe things to me in precisely detailed sequences, hoping I would come to see these intricate geometries the way he could, every metal-on-metal contact and even the tiniest of grooved surfaces invisible within the lock itself. For Towne, each lock could clearly be blown up to the scale of a megastructure, a palace the size of a city block, its inner gates and cylinders like cavernous hallways and rooms his mind could then wander through. He seemed to hold a detailed, three-dimensional model of each lock in his head, and he could manipulate it back and forth, round and round, like a hologram rotating in space.

…

Codella describes a monstrous residential complex known only as the Site Four and Five Houses: “Site Four and Five was a multistory poured concrete rabbit warren so sprawling and generic that even seasoned cops would get completely lost in its hallways or not be able to give the correct address for where they were when calling Central for backup.” If we recall LAPD tactical flight officer Cole Burdette’s interest in clarifying the city’s system of house numbers and addresses, Codella is just describing the indoor equivalent: making state-funded megastructures numerically legible to the police forces tasked with patrolling them. Even navigating their behemoth interiors required tactical innovation. Residential tower blocks require what are known as vertical patrols, for example, during which officers will walk the stairways up and down, often navigating only by flashlight, as dead bulbs can go for days or weeks at a time without being replaced.

The New Gold Rush: The Riches of Space Beckon!

by

Joseph N. Pelton

Published 5 Nov 2016

For too long there has been minimal progress made against these dangers because of what is a stupendous case of cosmic myopia. The time of change is now. It is time for a clear-cut change in the top strategic goals for all the world’s space agencies. Save Earth first! Explore and research outer space second. 4. The Unrealized Potential of Mega-structures and Intellectual Infrastructure in Space. It is possible that some space scientists and experts will say, “But the Sun’s power and processes are much too vast for human tools to change its behavior.” The answer is that one does not have to change the Sun’s behavior. We only need to create a solar shield, most likely at the L-1 Lagrange Point some 1.5 million km away from Earth—at the “balance point” between the Sun’s and Earth’s gravitational forces.

…

If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara> Reference 1. Joseph N. Pelton, “Let’s Build a Megastructure in Space to Save Earth,” Room Space Journal, Summer, 2016. Appendix: Current Status of the U. S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, Public Law 114-90 , as of June 2016 In December 2015 the U. S. Congress passed Public Law 114-90 that was signed into law by President Obama. Part of the requirements of that act was that the President was required to recommend a process whereby the U.S. would fulfill the requirements of the Outer Space Treaty to provide oversight of activities carried out by U.S. entities in space.

…

S. regulatory actions Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG) Space navigation Space R&D programs Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act of 2015 common heritage of mankind global commons legal enforcement outer space change policing regulatory system Sentinel infrared telescope space colonies traffic control and management Space Resource Utilization Space Swiss Systems (S3) Space tourism Space transportation ICAO radiation danger radio frequencies, allocation of SARPS traffic management and control Space-based navigation Space-based war-fighting systems SpaceHab Spaceplane system aerospace organizations safe and non-polluting development Space Ship 2 Space Swiss Systems (S3) SpaceShipOne and space tourism SpaceShipOne SpaceShipTwo Star wars Stratobus Stratolaunch Subspace/protospace Super automation Super urbanization Syncom 2 T TASI SeeTime Assignment Speech Interpolation (TASI) TDRS SeeTracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) system Ten Point Program the global commons global population control humanity laws and regulation mega-structures and intellectual infrastructure planetary protection programs singularity space- and ground-based infrastructure sustainability urban sprawl Time and human technological progress Time Assignment Speech Interpolation (TASI) Tiny 40-kg Early Bird satellite Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) system Transformational Satellite System (TSat) Transitional satellite (TSAT) Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space Tripartite space governance unit TSat SeeTransformational Satellite System (TSat) TSAT SeeTransitional satellite (TSAT) U U.

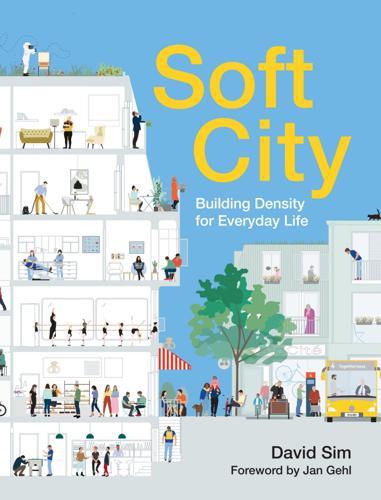

Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life

by

David Sim

Published 19 Aug 2019

However, there are particular challenges in accommodating buildings with uses that require very large surfaces in a way that makes them good neighbors to the medium-sized and smaller structures surrounding them. Clearly, some larger activities can fill an entire block, or at least a significant part of one. The larger buildings should be integrated into the local streetscape without breaking up the smaller-scale rhythm and life of local streets. 01. Edinburgh, Scotland. In a polite gesture, the mega-structure of the Victorian Balmoral Hotel (left) lifts its skirts to present small shops (unrelated to the hotel business) to the back steps leading to Edinburgh’s main railway station, offering useful services to hurried passengers. The 1980s shopping mall (right) does not afford such courtesy. 02.

…

The building has an active ground floor, which brings life to the surrounding streets, with independent restaurants, cafés, and shops. The hotel takes advantage of the enclosed block with a loop for servicing and access/evacuation. Section through hotel showing central atrium and aquarium tank. Landing a Big-Box Megastructure in a Fine-grained Neighborhood: IKEA, Altona, Hamburg, Germany In a time when online retail is increasing and large stores are pushed farther into suburban locations, the placement of a full-size IKEA store in a human-scale city neighborhood in Altona, Hamburg, Germany is a significant achievement.

New York 2140

by

Kim Stanley Robinson

Published 14 Mar 2017

You don’t know; you can’t see it, and the whole story has never been told to you. Sorry. Just the way it is. But if you then think furthermore that the bankers and financiers of this world know more than you do—wrong again. No one knows this system. It grew in the dark, it’s a stack, a hyperobject, an accidental megastructure. No single individual can know any one of these megastructures, much less the mega-megastructure that is the global system entire, the system of all systems. The bankers—when they’re young they’re traders. They grab a tiger by the tail and ride it wherever it goes, proclaiming that they are piloting a hydrofoil. Expert overconfidence. As they age out, a good percentage of them have made their pile, feel in their guts (literally) how burned out they are, and go away and do something else.

…

Over the scrubby pine barrens, then the green and empty New Jersey shore, which had been a drowned coastline even before the floods; then out over the blue Atlantic. Thus, as she reminded her audience, they had flown over one corridor in the great system of corridors that now shared the continent with its cities and farms, and the interstate highways and the railways and power lines. Overlapping worlds, a stack of overlays, an accidental megastructure, a postcarbon landscape, each of the many networks performing its function in the great dance, and the habitat corridors providing a life space for their horizontal brothers and sisters, as Amelia called them on her broadcasts. All creatures made good use of these corridors, which if not pure wilderness were at least wildernessy, and it was easy to wax enthusiastic about their success while flying over them at five hundred feet.

…

But they were on the hunt, so she sat in the corner and waited. Eventually they split off an inquiry and gave it to her to work on. She settled in and began to apply overlay maps to the snaps of the days when Rosen and Muttchopf had been kidnapped. Stacks within the great stack that was the city in four dimensions. An accidental megastructure, a maze they could reconstruct and then weave threads through. Outside the carrel the station emptied as people went home or out to dinner. They ate sandwiches brought in for them. More time passed, and the graveyard shift came in on a waft of cold air and bad coffee. On they worked. Gen paused at one point to regard her assistants.

From Satori to Silicon Valley: San Francisco and the American Counterculture

by

Theodore Roszak

Published 31 Aug 1986

the electronic new some was There point, a Marshall media as the "global village" that was 30 somehow cozy, participative, and yet at the same time technologically sophisticated. There was Paolo Soleri, who believed that the solution to the ecologi- modern world was the building of megastructural "arcologies" - beehive cities in cal crisis of the which the urban billions could tally environments. artificial who barnstormed O'Neill, be compacted into to- There was Gerard the country whipping enthusiasm for one of the zaniest schemes of all: up the launching of self-contained space colonies for the millions.

Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller

by

Alec Nevala-Lee

Published 1 Aug 2022

Although Jordan was disappointed by its presentation, she remained close to Fuller, whose support allowed her to pursue her studies of community planning “for participation by Harlem residents in the birth of their new reality.” In an era when the journalist Jane Jacobs was exposing the failures of urban projects in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Fuller continued to think in terms of megastructures, which kept him in the public eye at the expense of his vision of decentralization. By contrast, many of his other views were strikingly progressive. Fuller said that America was already “the most socialized of all countries in the world,” although it concealed this by underwriting corporations rather than individuals.

…

The project included a park, but Disney was more interested in a futuristic planned community, as the general manager of Disneyland recalled: “He expected a house that would be completely self-sufficient, its own power plant, its own electricity.” In the original plan, the town center was covered by a dome—a concept that was based partially on the Houston Astrodome, which had made a strong impression on Disney. Beneath this megastructure, conceived to enclose fifty acres, internal buildings such as a hotel tower, stores, and theaters would benefit from total climate control, allowing for a variety of architectural styles, while emissions would be minimized by an electric transit system. Disney called it the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, or Epcot.

…

Some time later, however, the admiral was asked to chair a task force on wind power, and he confessed to Luce that Fuller might have had a point. Fuller busied himself with a hexagonal hanging bookshelf that gained stability as its weight increased, which became his last patent, and he asked his Cleveland office—to which he owed tens of thousands of dollars—to work on a huge model of a megastructure called the Gigundo Dome. With Norman Foster, he designed the Autonomous House, a rigid “double deresonated dome” with concentric shells that could rotate to regulate the capture of solar energy. Fuller hoped that a prototype could become his home in Los Angeles, as well as a house in Wiltshire County, England, for Foster’s family.

Exoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial Life

by

Donald Goldsmith

Published 9 Sep 2018

Dustlike material orbiting the star—typical of stars as they form, but absent from the vicinity of mature stars—could swirl in complex ways, blocking different amounts of light at different times.2 Rings of material in the far outer solar system might provide the answer, if those rings happened to lie between Kepler’s line of sight and the star.3 Perhaps the data have errors, either in the measured light variations or in the spectral observations that establish Tabby’s Star as no youngster. Or perhaps—and here the public mind grows most heavily engaged—a megastructure surrounds the star, a variation on a “Dyson sphere,” the enormous light- and heat-trapping shield around a star that the physicist Freeman Dyson suggested in 1960 could result from an advanced civilization’s attempt to capture all of its star’s energy. If the shield were only partial, perhaps composed of many parts in orbit around the star, its motions could at times block a large portion of the stellar output from our view.4 In scientific circles, all hypotheses remain subject to a basic approach: How can we attempt to check on their validity?

…

,” Scientific American news posting, May 1, 2017, available at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/have-aliens-built-huge-structures-around-boyajian-rsquo-s-star/#; see also Jason Wright et al., “The G Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies: IV. The Signatures and Information Content of Transiting Megastructures,” Astrophysical Journal 816 (2016): 17. 5. Gerry Harp et al., “Radio SETI Observations of the Anomalous Star KIC 8462852,” Astrophysical Journal 825 (2016): 155. 6. Jason Wright and Steinn Sigurðsson, “Families of Plausible Solutions to the Puzzle of Boyajian’s Star,” Astrophysical Journal Letters 829 (2016): L3. 7.

City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age

by

P. D. Smith

Published 19 Jun 2012

We live today in an age of rapidly expanding megacities, and it is therefore not difficult to imagine a future in which the world itself has become a continuous city, such as Trantor in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation and Empire series of novels, a phenomenon known as ‘Ecumenopolis’, a word first used in 1967. In a future world with ever more people and fewer resources, it no longer seems fanciful to imagine the creation of ‘megastructures’ (a word coined by Rayner Banham in the 1970s), in which a whole city is contained within a single building. The Situationist architect Constant Nieuwenhuys proposed a utopian megastructure called New Babylon as early as 1956. If, as scientists predict, the glaciers melt and sea levels rise dramatically, then ship-cities such as Armada in China Miéville’s The Scar, or cities built out across water, as in architect Kenzo Tange’s elegant ‘Plan for Tokyo’ (1960) which extended the Japanese capital out into the bay, might become reality.

…

Every building would be ‘a city in itself, completely self-sustaining, receiving its supplies from great merchandise ways far below the ground’. The magazine predicted that an urban utopia awaited us in which pollution would be eliminated and people would ‘live in the healthy atmosphere of the building tops’.32 A Walking City, a robotic megastructure designed by Ron Herron of Archigram in 1964. In the same year as this was published, Dorothy and her fellow travellers in The Wizard of Oz caught their first glimpse of the sky-high crystalline towers and domes of the Emerald City glittering on the horizon. ‘It’s beautiful isn’t it? Just like I knew it would be,’ says Dorothy.

The Paths Between Worlds: This Alien Earth Book One

by

Paul Antony Jones

Published 19 Mar 2019

I will automatically recognize it and assimilate the information.” I nodded at the robot. “Will do.” “Thank you, Meredith.” Silas dipped his shoulders in acknowledgment. I leaned back against the rocks. The clouds that had earlier obscured the monolith had moved on, so now most of the huge mega-structure was visible. It was hard to look at it without feeling uneasy; it was just so massive. But it was also beautiful. The reflected sunlight shone like a distant beacon. A sudden realization hit me like a slap across my face. I jumped to my feet. “Are you okay, Meredith?” Silas said. “I’m fine,” I replied, then, “Come on.

…

“I would not even hazard a guess,” Chou admitted quietly, in a rare moment of technical ignorance. “It is just like a leisurely boat ride on a Sunday afternoon,” Freuchen said, only half joking. I playfully elbowed him in his ribs and laughed. “Sure is,” I said, “if you ignore the robot, the woman from the far-flung future, and the mega-structures built by some long forgotten unknown hand.” “Vell, ven you put it like that.” We all laughed. “It is a pleasant change,” Chou said, a smile playing across her lips. Freuchen stood up, placed a foot on the gunwale, and leaned against the roof of the pilothouse, his eyes fixed on the ever-nearing coastline.

Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve And/or Ruin Everything

by

Kelly Weinersmith

and

Zach Weinersmith

Published 16 Oct 2017

Thus, the vision of an architect becomes less constrained by the nature of factory production. If we ever get to a point where an architect can design a building and then just tell the machines to go build it, we’ll have cheaper, better, faster housing for regular homes, and we’ll have more incredible, beautiful, wondrous megastructures. So let’s get to it. Actually, wait. First can we just for a moment discuss how weird some of the architecture literature is? It’s like, for a second someone will talk about the technical details of how to build a certain steel facade, then suddenly they’re rhapsodizing about “exploring a new digitally influenced materiality.”

…

.* One possible virtue of solar arrays was that they might (in the very distant future) be valuable for space transport. The idea is that you harvest energy from panels near the sun and then beam power to vehicles that are already in space. This might actually be the way things go in the long term, since the sun represents an enormous amount of free energy. But by the time we can launch megastructures with robot repairmen onboard, we’re guessing there’ll be better options. We looked at a lot of far-out technologies for this book, and no doubt some of them will not materialize, or at least not materialize in the form we find most exciting. But space solar seemed to us to be undesirable even under its most ideal conditions.

Reset

by

Ronald J. Deibert

Published 14 Aug 2020

The entire ecosystem was not developed with a single well-thought-out design plan, and security has largely been an afterthought. New applications have been slapped on top of legacy systems and then patched backwards haphazardly, leaving persistent and sometimes gaping vulnerabilities up and down the entire environment for a multitude of bad actors to exploit.12 It’s all an “accidental megastructure,” as media theorist Benjamin Bratton aptly put it.13 The global communications ecosystem is not a fixed “thing.” It’s not anywhere near stasis either. It’s a continuously evolving mixture of elements, some slow-moving and persistent and others quickly mutating. There are deeper layers, like those legacy standards and protocols, that remain largely fixed.

…

Why information security is hard — An economic perspective. Seventeenth Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (358–365). IEEE; Anderson, R. (2000). Security Engineering: A Guide to Building Dependable Distributed Systems, 3rd Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Retrieved from https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/book.html An “accidental megastructure”: Bratton, B. H. (2016). The stack — On software and sovereignty. MIT Press. A bewildering array of new applications: Lindsay, J. R. (2017). Restrained by design: The political economy of cybersecurity. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 19(6), 493–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPRG-05-2017-0023 Merriam-Webster defines social media: Merriam-Webster.

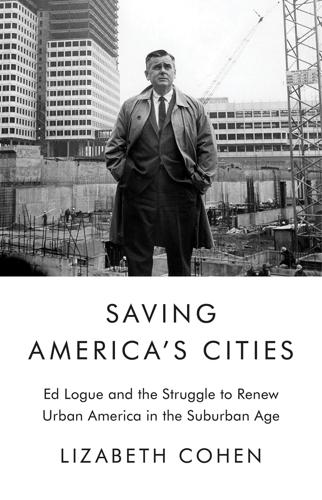

Saving America's Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age

by

Lizabeth Cohen

Published 30 Sep 2019

Stern, already embarked on his own path toward postmodernism, accused urban renewal’s architects of promoting “heroic” designs rigidly loyal to orthodox modernist principles rather than more flexibly responding to how people actually used a particular urban site. He singled out “piazza compulsion,” obsession with towers, and technologically innovative “mega-structures” as common mistakes.122 Even the Temple Street Parking Garage, designed by Stern’s Yale professor Paul Rudolph, came in for criticism, with its “arbitrary” and “unbending geometry of stacks of identically sized structural elements”—the aqueduct-inspired arches much beloved by Logue and Lee—and for an accommodation to the automobile that was “perhaps too expensive and too prominent.”123 Logue, Abrams, and many other patrons of the era’s urban architecture would not have agreed with Stern’s critique.

…

Rudolph brilliantly figured out a way of integrating three fragmented, uninspiring designs into one cohesive, triangular, and sculptural complex enclosing a bowl-like central courtyard intended as a counterpoint to the convex dome on the Massachusetts State House several blocks away.60 He gave the megastructure the massiveness he felt its social importance required, prescribed ambitious design standards for all three units, planned a grand serpentine stairway entrance, and faced the entire surface with his distinctive corrugated concrete, originally developed for the Yale Art and Architecture Building.

…

Wilson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966), 561–62, originally published in Abrams, The City Is the Frontier (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), chapter 9. 122. Robert A. M. Stern, New Directions in American Architecture (New York: George Braziller, 1969), 8, 10, 80–108; for “piazza compulsion,” 91–94; for towers, 94–98; on technologically inspired mega-structures, 105–8. 123. Stern, New Directions in American Architecture, 15, 17; also see discussion of Rudolph, 12. 124. Logue to Eugene Rostow, December 5, 1961, EJL, Series 6, Box 150, Folder 445. 125. Quotes from Logue, interview, Schussheim, 20; Talbot, Mayor’s Game, 127, 131, also see 117–18, 126–34.

Distrust That Particular Flavor

by

William Gibson

Published 3 Jan 2012

Business Times editor Patrick Daniel, Monetary Authority of Singapore official Shanmugaratnam Tharman, and two economists for regional brokerage Crosby Securities, Manu Bhaskaran and Raymond Foo Jong Chen, pleaded not guilty to violating Singapore’s Official Secrets Act. South China Morning Post, 4/29/93 Reddy Kilowatt’s Singapore looks like an infinitely more livable version of convention-zone Atlanta, with every third building supplied with a festive party hat by the designer of Loew’s Chinese Theater. Rococo pagodas perch atop slippery-flanked megastructures concealing enough cubic footage of atria to make up a couple of good-sized Lagrangian-5 colonies. Along Orchard Road, the Fifth Avenue of Southeast Asia, chockablock with multilevel shopping centers, a burgeoning middle class shops ceaselessly. Young, for the most part, and clad in computer-weathered cottons from the local Gap clone, they’re a handsome populace; they look good in their shorts and Reeboks and Matsuda shades.

Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind

by

Susan Schneider

Published 1 Oct 2019

Indeed, barring blaringly obvious scenarios in which alien ships hover over Earth, as in films like Arrival and Independence Day, I wonder if we could even recognize the technological markers of a truly advanced superintelligence. Some scientists project that superintelligent AIs could be found near black holes, feeding off their energy.8 Alternately, perhaps superintelligences would create Dyson spheres, megastructures such as that pictured on the following page, which harness the energy of an entire star. But these are just speculations from the vantage point of our current technology; it’s simply the height of hubris to claim that we can foresee the computational structure or energy needs of a civilization that is millions or even billions of years ahead of our own.

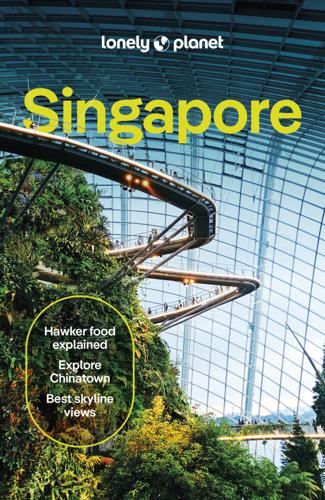

Lonely Planet Singapore

by

Lonely Planet

Published 14 May 2024

DON'T MISS Supertree Observatory OCBC Skyway Cloud Forest Flower Dome Floral Fantasy Heritage Gardens Kingfisher Wetlands Flower Dome & Cloud Forest To the far north, two asymmetrical space-age bio-domes act as conservatories for more than 217,000 plants from 800 species. The Flower Dome holds the Guinness World Record for the largest glass greenhouse, occupying an area equivalent to 75 Olympic-size swimming pools. The innovative megastructure replicates a dry Mediterranean climate, maintaining a temperature of 23°C to 25°C. Free tours run every weekend from 2pm to 5pm. Dine inside the Flower Dome at the Michelin-starred Marguerite (marguerite.com.sg), helmed by Melbourne-born chef Michael Wilson, for the ultimate back-to-nature experience.

The Oil and the Glory: The Pursuit of Empire and Fortune on the Caspian Sea

by

Steve Levine

Published 23 Oct 2007

Next he offered Remp access to geological and seismic documents containing the most vital secrets of Baku’s “elephants.” Until now, the materials had been kept carefully hidden from outside eyes. Remp could see why. They depicted world-class oil fields waiting to be drilled, clearly visible in painstakingly drawn maps and sketches and well logs that revealed what Remp recognized as “super megastructures” offshore. In August 1990, Remp returned to Scotland, where he drafted a five-page letter to the two big oil companies with U.K. headquarters, British Petroleum and Shell. In it, he noted his appointment as agent for Azerbaijan’s oil industry, summarized Effendiev’s data, and invited their inquiries.

…

Out came his personal: Khoshbakht Yusufzade took the photograph from his office safe, November 28, 1996. “was dead”: Author interview with Remp. “You never felt”: Author interview with Tim Hartnett, August 29, 1996. “We will liquidate”: Author interview with Tom Doss (September 15, 2004), who headed Amoco’s Baku negotiations starting in 1991. “super megastructures”: Author interview with Remp. “What do you suggest?”: Author interview with Fehlberg, April 1, 1996. “coming-out party”: Ibid. an American citizen, “one in ten”: Author interview with Ray Leonard, Amoco’s vice president for frontier exploration, February 7, 2005. “risk-taker,” “liked technical people”: Author interview with Doss.

The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century

by

George Friedman

Published 30 Jul 2008

Since reunification in 1871, Germany has been the economic powerhouse of Europe. Even after World War II, when Germany had lost its political will and confidence, it remained the most dynamic economic power on the continent. After 2020 that will no longer be the case. The German economy will be burdened by an aging population. The German proclivity for huge corporate megastructures will create long-term inefficiencies and will keep its economy enormous but sluggish. A host of problems, common to much of Central and Western Europe, will plague the Germans. But the Eastern Europeans will have fought a second cold war (allied with the leading technological power in the world, the United States).

White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa

by

Sharon Rotbard

Published 1 Jan 2005

Intrinsically then, Zandberg portrayed the local International Style architecture as neither part of a great historical movement nor a revolutionary aesthetic, but primarily as a useful model for everyday city life, as a vehicle to promote values such as usability, economy, modesty, cleanliness, logic and common sense. Tel Aviv had only just begun to digest Israel’s post-1967 war testosterone-pumped architecture and its huge megastructures, like the Atarim Piazza, the Dizengoff Center and the New Central Bus Station. With the corporate offensive of the 1990s already emerging, such ‘effeminate’ values were certainly needed. Zandberg helped set the moral ground for the transformation of the White City narrative from being an academic chapter in an architectural journal into an integral part of the city’s urban agenda.

Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life

by

Colin Ellard

Published 14 May 2015

When I conducted research at the site in 2012, my interest in the building, though perhaps connected to the tumult over gentrification, was more pedestrian—and literally so. On my first visit to the location, undertaken to plan a series of psychogeographic studies in collaboration with New York’s Guggenheim Museum, I was mostly interested in how this gigantic megastructure, plopped into a neighborhood more commonly populated with tiny bars and restaurants, bodegas, pocket parks, playgrounds, and many different styles of housing might influence the psychological state of the urban pedestrian. What happens inside the mind of a city-dweller who turns out of a tiny, historic restaurant with a belly full of delicious knish, and then encounters a full city block filled with nothing but empty sidewalk beneath their feet, a long bank of frosted glass on one side, and a steady stream of honking taxicabs on the other?

Carmageddon: How Cars Make Life Worse and What to Do About It

by

Daniel Knowles

Published 27 Mar 2023

Oddly enough in the architectural drawings it was never raining, the concrete was shiny and white, and the cars seem to be moving at a decent pace, never stuck in traffic. Yet as Saumarez Smith, an enthusiast for the period’s optimism, wrote in his book, Boom Cities, when constructed, the actual result was largely schemes “made up of a gimcrack modernism of tacky pedestrian precincts, grim underpasses, budget megastructures and gargantuan car parks.” The need for developers to make money meant that architects did not always get their visionary way. Instead, car parking did. And Britain was scarcely alone in this. All of Europe was doing it. Italy began building an orbital motorway around Rome, the Grande Raccordo Anulare, in 1952.

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming

by

David Wallace-Wells

Published 19 Feb 2019

There is the “zoo hypothesis,” which suggests that aliens are just watching over us and letting us be for now, presumably until we reach their level of sophistication; and something like its inverse—that we haven’t heard from aliens because they’re the ones sleeping, in a civilization-scale system of extended-sleep pods like the ones we know from science fiction spaceships, waiting while the universe evolves a shape more suitable to their needs. As far back as 1960, the polymath physicist Freeman Dyson proposed that we may be unable to find alien life in our telescopes because advanced civilizations may have literally closed themselves off from the rest of space—encasing whole solar systems in megastructures designed to capture the energy of a central star, a system so efficient that from elsewhere in the universe it would not appear to glow. Climate change suggests another kind of sphere, manufactured not out of technological mastery but first through ignorance, then indolence, then indifference—a civilization enclosing itself in a gaseous suicide, a running car in a sealed garage.

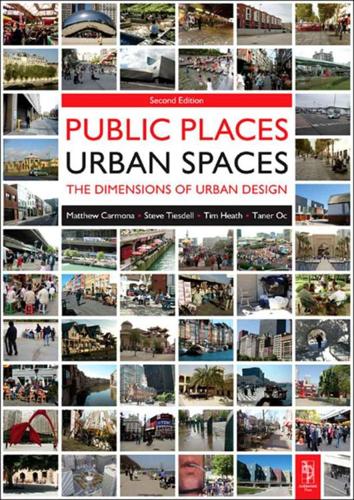

Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design

by

Matthew Carmona

,

Tim Heath

,

Steve Tiesdell

and

Taner Oc

Published 15 Feb 2010

BOX 4.2 The Battery Park City Method Masterplanned by Cooper & Eckstut (adopted in 1979), Battery Park City has become established as a ‘durable paradigm for larger-scale urban real estate development in North America (Love 2009: 210). Based on extending the streets of the Manhattan grid, as Panerai et al (2004: 181) explain:‘Instead of the superblocks and megastructure that implied one designer and a single investor for a few very large and expensive projects, these streets defined moderately sized urban blocks that were capable of accommodating buildings designed by a variety of architects using different developers’ Love (2009: 212) suggests it has endured because of its real estate development logic, whereby dividing large development parcels into independent ‘blocks’ has two main benefits: first, it is divided into flexible phases, readily adaptable to suit the changing real estate market and, second, by dimensioning blocks to correspond to the optimum parcel size for a typical residential or commercial development project, the resulting building is guaranteed open exposures and free access on all sides (i.e. no party walls).

…

Hillier (1996a: 169) argues that:‘It is this positive feedback loop built on a foundation of the relation between the grid structure and movement which gives rise to the urban buzz, which we prefer to be romantic or mystical about – but which arises from the co-incidence in certain locations of large numbers of different activities involving people going about their business in different ways.’ Hillier (1996a: 169) illustrates this by a negative example – London’s South Bank, an area built in the 1970s of Modernist megastructures and separated pedestrian walkways. Despite (at the time) the co-existence in a small area of many major functions, there was little ‘urban buzz’. Hillier attributed this to the configuration of space, which failed to bring the different groups of space users – concert attendees, gallery visitors, residents, office workers, etc. – into patterns of movement prioritising the same spaces – groups moved through the area like ‘ships in the night’, depriving the area of the multiplier effects of different space users ‘sparking off’ each other.

B Is for Bauhaus, Y Is for YouTube: Designing the Modern World From a to Z

by

Deyan Sudjic

Published 17 Feb 2015

His account of the past thirty years of British architecture reduces Norman Foster, James Stirling, Alison and Peter Smithson and Denys Lasdun to walk-on parts; the greater part of the action is focused on such figures as Owen Luder, Rodney Gordon and Robert Lister, responsible for provincial shopping-centre megastructures, bush-hammered concrete car parks and trade union offices. Blueprint’s tabloid format, powerfully designed by Simon Esterson, was borrowed from Skyline, a short-lived New York magazine art directed by Massimo Vignelli that set a worrying precedent by going under just before our first issue came out.

Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World's Tallest Skyscrapers

by

Jason M. Barr

Published 13 May 2024

Another possibility was that Khan got the idea from his own residence, designed by world-famous architect I. M. Pei. “I wouldn’t call them tube structures, more like proto-tubes,” architectural historian Tom Leslie told me. “Their innovation was just enlarging the typical mullions until they became structural, but they definitely don’t have the megastructural properties that Khan’s tube structures do. Khan and his family lived in the University Apartments that Pei designed in the late 1950s, so there’s no doubt that he understood the principle.” Dewitt Chestnut Apartments (1966), Chicago (Chicago History Museum, Hedrich-Blessing Collection, HB-28864-F) To add additional stiffness, the core could also be designed as a tube to create a tube-in-tube structure.

The Devil's Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square

by

James Traub

Published 1 Jan 2004

Venturi described his thinking in a subsequent book, Learning from Las Vegas (written with Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown). “Times Square is not dramatic space,” he wrote, “but dramatic decoration. It is two-dimensional, decorated by symbols, lights and movement.” Thus he concluded that “a decorated shed” would be a more apt homage to its traditions than “megastructural bridges, balconies and spaces.” Venturi was the first architect to propose a new idiom faithful to Times Square’s helter-skelter, mongrelized past; but since he had done so with an almost perverse indifference to the site’s economic value, the developer rejected the idea. Sharp was, on the other hand, dazzled by the work of John Portman, the architect-developer who had built the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and who was becoming known for his glass hotels with soaring interior spaces.

Making the Modern World: Materials and Dematerialization

by

Vaclav Smil

Published 16 Dec 2013

DocID=54693 (accessed 23 May 2013). Porada, E. (1965) The Art of Ancient Iran: Pre-Islamic Cultures, Crown Publishers, New York. Potonik, J. (2012) Any Future for the Plastic Industry in Europe? http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-12-632_en.htm (accessed 23 May 2013). Prak, M. (2011) Mega-structures of the middle ages: the construction of religious buildings in Europe and Asia, c. 1000-1500. Journal of Global History, 6: 381–406. President's Materials Policy Commission (1952) Resources for Freedom, A Report to the President by the President's Materials Policy Commission, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape

by

James Howard Kunstler

Published 31 May 1993

It wasn't the final solution, but it might do as long as the buildings lasted-which was not necessarily long. One infamous project, the crime-plagued Pruitt-Igoe apartment complex in St. Louis, was demolished only four teen years after completion. Another type of Radiant City, the "big footprint" megastructure 7 9 _ T HE GE O G RA P H Y O F N O W HE RE embedded in an old bulldozed central business district, such as the Empire State Plaza in Albany, New York, and the Renaissance Center in Detroit, were grimly tole;;rted by the new postwar leg�oureaU: crats and corporate drones. The employee--a step above "worker" arrived from a green suburb in his car, parked in an underground garage, ate lunch within the complex, and had no need to venture out into the agoraphobic voids between the high-rise office slabs, let alone beyond the voids to the actual city, with its messy street life, crime, and squalor.

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by

Michael Bhaskar

Published 2 Nov 2021

So-called fifth wave technologies begin to emerge: antimatter engines, light sails, ramjet fusion engines and nanoships. Nanotechnology assemblers are a reality, rendering the physical world an effortlessly malleable creative platform, even as robotic fabricators grow to the next level of sophistication, constructing vast gossamer megastructures in space. Yet more significant are the first fully functioning Von Neumann probes: self-replicating robots thrown out into the galaxy to endlessly reproduce themselves, ultimately to form a numberless swarm strung out across space. A full Type II civilisation is eventually realised with the construction of a Dyson sphere around the Sun, collecting all its energy.

Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old

by

Andrew Steele

Published 24 Dec 2020

These fibrils then bind together, along with various other molecules, to form even thicker structures called fibres – like the thick, many-stranded cables which hold up a suspension bridge. The exact structure of individual collagen molecules is absolutely critical to the multi-thousand-molecule megastructure of a collagen fibre. It dictates how the molecules coalesce into fibrils, and how the fibrils assemble into fibres, and what other molecules are drawn in to act as support, glue or lubricant. The result, in turn, controls a fibre’s properties – not too stiff, not too flexible, but just right in a huge range of biological contexts.

Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World

by

Henry Grabar

Published 8 May 2023

Parking requirements helped trigger an extinction-level event for bite-sized, infill apartment buildings like row houses, brownstones, and triple-deckers; the production of buildings with two to four units fell more than 90 percent between 1971 and 2021. What apartments did get built were clustered in megastructures whose design was dictated by parking placement. One popular model is the “Texas donut,” in which a ring of apartments encircles a five- or six-story parking garage (this is the type of building you see in the cool neighborhoods of growing cities). Another is the “parking podium tower,” like Chicago’s corncob Marina City, in which the housing sits atop the parking.

The Terraformers

by

Annalee Newitz

The path took them along the edges of agricultural zones and through clusters of drying trellises that looked like they would be mills one day. A group of parrots flew overhead, their voices lost in the wind. It was almost like they had left the city behind. And then they turned around and saw Lefthand’s skyline of unsteady megastructures, doomed to rot in a decade. Today’s agenda, Misha explained later over breakfast, would be to meet with the top Emerald rep in town and ask her what she thought about public transit for the city. “What?” Sulfur gulped their marshelder porridge too fast, and it became a knob in their throat.

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by

Adam Greenfield

Published 29 May 2017

The more audacious observers of technical advancement dare to speculate that the point is not far off at which molecular nanotechnology and the “effectively complete control over the structure of matter” it affords finally bring the age of material scarcity to its close.25 In places where Green Plenty has broken out, most large-scale interventions in the built environment are intended to democratize access to the last major resource truly subject to conditions of scarcity: the land itself. Placeless urban sprawl is overwritten by high-density megastructures woven of recovered garbage by fleets of swarming robots.26 Equal parts habitat and ecosystem, they bear the signature aesthetic of computationally generated forms no human architect or engineer would ever spontaneously devise, and are threaded into the existing built fabric in peculiar and counterintuitive ways.

The Edifice Complex: How the Rich and Powerful--And Their Architects--Shape the World

by

Deyan Sudjic

Published 27 Nov 2006

From then on, Rockefeller treated the reconstruction of a city as if he were an eighteenth-century English landowner adding a wing to his country seat and supervising the construction of a series of follies in the grounds. It was Rockefeller’s idea that Harrison should design an artificial ground level for the mall, creating a megastructure, spanning a shallow valley. The inspiration, bizarrely enough, seems to have been the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa. According to Harrison, Rockefeller showed him how ‘he wanted to stop the valley with a great wall going north and south. He had seen a something like it on a trip to Tibet. He wanted the feeling of separating the mall into a localized community, up on top of the hill so that he could not only get the vista of the wall, but of the whole capitol adjunct at the top.

How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

by

Ryan North

Published 17 Sep 2018

* While the foundations of even the simplest intercontinental weather control apparatus are unfortunately too complex to be included in this book, we promise that once you invent umbrellas (the recipe is “fabric plus a few sticks,” and they were first invented in China around 400 BCE), you’ll hardly notice. Honest. * Specifically, give it several decades of sustained interplanetary engineering advances before your civilization can begin to think about constructing variable solar megastructures. * And by “allows,” we mean “induces.” * Wheelbarrows are easy to invent: they’re just a wheel combined with a lever. Mount the wheel at the end of two planks, and build a box on top of those planks to carry the load. Add feet to the end of the planks opposite the wheel so that when it’s not being lifted the box rests flat, and there’s your wheelbarrow.

Retrofitting Suburbia, Updated Edition: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs

by

Ellen Dunham-Jones

and

June Williamson

Published 23 Mar 2011

Well intended to separate people from fast-moving cars, this is an urbanism of superblocks with separated uses, separated transportation systems, and buildings separated from streets. A mix of mostly horizontal pedestrian linkages are then employed to connect the parts back together, including megastructures, pedestrian malls, raised walkways, plinths, plazas, and public art pieces.24 Housing was rarely integrated into the mix, especially in the edge-city examples, and the pedestrian infrastructure generally stopped at the ring of surface or structured parking, discouraging connection to future or existing adjacent development except by car.

The Last Astronaut

by

David Wellington

Published 22 Jul 2019

Trying to keep her breathing normal and calm, she twisted it all the way to the left. The suitport connection behind her gasped as it released. She felt herself drift forward, just a few centimeters. She was free of the ship. Floating free, eight million kilometers above the Earth. Two kilometers away from an alien megastructure. Very much alone, with nothing at all above or below her, forever. “Suit is responding as expected,” she said. “Internal temperature is a comfortable twenty-one Celsius.” There was a reason astronauts endlessly reported their status while on EVAs. It wasn’t for the sake of NASA, which was too far away to do anything if something went wrong.

Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World

by

Nick Bostrom

Published 26 Mar 2024

The more that we boost our capacities of understanding, the more we may simultaneously accelerate our cultural creativity and complexity, so that the former never catches up with the latter—just as a sprinter may never catch his shadow, no matter how fast and far he runs. Even a “Jupiter brain” (to use a term from the old transhumanist lexicon—a computational megastructure with a mass comparable to that of a gas giant like the planet Jupiter) might remain intellectually stimulated and challenged in a peer group that includes other Jupiter brains, which keep learning and improving and creating at pace with its own advances in skill and understanding. It might be that the idea that interestingness could in this manner be long extended derives its plausibility from our concept of interestingness having a social component embedded within it.

Matter

by

Iain M. Banks

Published 14 Jan 2011