military-industrial complex

description: concept in military and political science

463 results

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy

by

David Hoffman

Published 1 Jan 2009

"Over the previous five-year plans, military spending had been growing twice as fast as national income. This Moloch was devouring everything that hard labor and strain produced ... What made matters worse was the fact that it was impossible to analyze the problem. All the figures related to the military-industrial complex were classified. Even Politburo members didn't have access to them." 13 On the staff of the Central Committee, one man knew the secret inner workings of the military-industrial complex. Vitaly Katayev had the appearance of a thoughtful scientist or professor, with a long, angular face and wavy hair brushed straight back. As a teenager he loved to design model airplanes and ships.

…

There was a "permanent gap," he said, between the drawing boards and the factories. This was the underside of the Soviet military machine. Katayev's notes show that the military-industrial complex was indeed as large as Gorbachev feared. In 1985, Katayev estimated, defense took up 20 percent of the Soviet economy.16 Of the 135 million adults working in the Soviet Union, Katayev said, 10.4 million worked directly in the military-industrial complex at 1,770 enterprises. Nine ministries served the military, although in a clumsy effort to mask its purpose, the nuclear ministry was given the name "Ministry of Medium Machine Building," and others were similarly disguised.

…

Defense factories were called upon to make the more advanced civilian products, too, including 100 percent of all Soviet televisions, tape recorders, movie and still cameras and sewing machines. 17 Taking into account all the ways the Soviet military-industrial complex functioned and all the raw materials it consumed and all the tentacles that spread into civilian life, the true size of the defense burden on the economy may well have been even greater than Katayev estimated. Gorbachev would need deep reserves of strength and cunning to challenge this leviathan. At one Politburo meeting, he lamented, "This country produced more tanks than people." The military-industrial complex was its own army of vested interests: generals and officers in the services, designers and builders of weapons, ministers and planners in the government, propaganda organs, and party bosses everywhere, all united by the need, unquestioned, to meet the invisible Cold War threat.

Marx at the Arcade: Consoles, Controllers, and Class Struggle

by

Jamie Woodcock

Published 17 Jun 2019

They were early curiosities and experiments, technical demonstrations rather than something fun to play around with. The technological basis for videogames was laid by the US military. As Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter have argued, “They originated in the U.S. military-industrial complex, the nuclear-armed core of capital’s global domination, to which they remain umbilically connected.”26 The military-industrial complex was enlisting the “first draft of immaterial labor, the highly educated techno-scientific personnel recruited to prepare, directly or indirectly, for nuclear war with the Soviet Union.” This preparation meant establishing academic research centers with military funding and developing “the massive defense-contracting system, in which the giants of U.S. corporate power, including information and telecommunication companies,” including IBM, “prepared for doomsday.”27 The expertise put to work in academic, military, and corporate laboratories was also applied to early games.

…

This would later involve Sony, a much larger Japanese company, entering the stage too.57 The rise of Japanese videogames is also linked to the military-industrial complex. The irony is that Japan, defeated by the military and nuclear forces of the US, later “excelled in adopting the victors’ techno-cultural innovations.”58 The state-led policies in Japan pushed for a postindustrial reconstruction after the Second World War, laying the technical basis for the videogames industry. (This is analogous, in part, to the later experience of South Korea with online gaming.)59 While the military-industrial complex remained a key part of Japan’s development of videogames, so too was there a subversive element drawn into the industry.

…

Douglas created a noughts and crosses game (more commonly known as “tic-tac-toe” in the US) on Cambridge’s EDSAC computer for research. Two years later, at the Los Alamos laboratory (infamous for the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb), programmers in their spare time developed the first blackjack game for the IBM 701.28 These early videogame links to the military-industrial complex were further solidified in 1955 with the introduction of the military war game Hutspiel, which simulated a war between NATO and the Soviet Union, represented, respectively, by blue and red characters. The similarities between these simulations and later videogames was riffed on in the 1983 film WarGames, in which Matthew Broderick’s character hacks into a military supercomputer.

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by

Robert Higgs

and

Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr.

Published 15 Jan 1987

Graham, Jr., Toward a Planned Society: From Roosevelt to Nixon (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), esp. pp. 79-82. 2. The literature on the military-industrial complex is voluminous. See, for example, James L. Clayton, ed., The Economic Impact of the Cold U'tzr: Sources and Readings (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970); Steven Rosen, ed., Testing the Theory of the Military-Industrial Complex (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1973); Paul A. C. Koistinen, The Military-Industrial Complex: A Historical Perspective (New York: Praeger, 1980); Jacques S. Gansler, The Defense Industry (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1980); J.

…

The ensuing "war within a war," the scene of "continuous conflict, acrimony, and bureaucratic infighting as civilian and military agencies clashed in the forwarding of their opposing interests," affords many lessons for students of public administration and politics. 37 My focus, however, is on another aspect of this experience. The great military-industrial mobilization of 1940-1945 created a new institution (or set of connected institutions), the military-industrial complex, pregnant with implications for the character of the postwar political economy. The origins and nature of that complex in World War II are at issue here. The military-industrial complex denotes the institutionalized arrangements whereby the military procurement authorities, certain large corporations, and certain executive and legislative officials of the federal government cooperate in an enormous, ongoing program to develop, produce, and deploy weapons and related products.

…

"Labor for the Picking: The New Deal in the South." Journal of -Economic History 43 (Dec. 1983). Wilbur, Ray Layman, and Arthur Mastick Hyde. The Hoover Policies. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1937. WORLD WAR II Beaumont, Roger A. "Quantum Increase: The MIC [military-industrial complex] in the Second World War." In U'tlr, Business, and American Society: Historical Perspectives on the Military-Industrial Complex, ed, Benjamin Franklin Cooling. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1977. Blum, Albert A. "Birth and Death of the M-Day Plan." In American Civil-Military Decisions, ed. Harold Stein. Birmingham: University of Alabama Press, 1962.

The New Rules of War: Victory in the Age of Durable Disorder

by

Sean McFate

Published 22 Jan 2019

Ultimately, the deep state of the military-industrial complex encourages the militarization of foreign policy, forming a challenge to world peace. A favorite tactic of deep state doubters is to deride the idea as fringe kooky, but Eisenhower’s credibility is beyond reproach. He was a two-term president, a retired five-star general, and a hero of World War II—he had unparalleled authority in the matter. The language he used to describe the military-industrial complex mirrors how we think about deep states today. “We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence . . . by the military-industrial complex,” he said, adding, “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”17 For his sins, the military, with congressional approval, renamed its top war college for arms procurement after him.18 At least the deep state has a sense of humor.

…

The plutocrats met their match with the new president, Theodore Roosevelt, who was the first White House occupant to say it aloud: “Behind the ostensible government sits enthroned an invisible government, owing no allegiance and acknowledging no responsibility to the people.”16 The secret marriage of corporate and political agendas birthing an American deep state may shock some, but it shouldn’t. President Eisenhower famously warned the nation against the corrupting influence of what he termed the “military-industrial complex” in his farewell address. The military-industrial complex is a deep state alliance among the military, the arms industry that supplies it, and Congress, which oversees it. It’s an infinity loop fueled by corporate contributions to politicians, congressional approval for military spending, lobbying to support bureaucracies, and pliant government oversight of the industry.

…

“I’m telling you right now,” Work said, “ten years from now if the first person through a breach isn’t a friggin’ robot, shame on us.” 11 The colonel was sharing his iPhone with his neighbors, who were equally impressed. The presentation ended with a shout-out to the defense industry, whose representatives nearly stood up and whooped. The Third Offset Strategy bestows a multibillion-dollar shopping list to the military-industrial complex. To push matters along, the Department of Defense set aside $18 billion as seed money.12 It also took the unprecedented step of establishing its own venture capital fund in California’s Silicon Valley, courtesy of US taxpayers. It need not be profitable, just supply the warfighter with gee-whiz technology.

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

Academic scientists, not politicians and bureaucrats, spurred the funding for and shaped the design of more-powerful computers, breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, and the Internet—a marvelous communication network of many nodes but no single command center. Government largesse extended beyond the military-industrial complex, too. Deregulation and tech-friendly tax policies, lobbied for and especially benefiting computer hardware and software companies and their investors, helped the Valley grow large; ongoing public investments in research and education trained and subsidized the next generation of high-tech innovators.

…

Supersonic planes demanded sophisticated electronics to help their human pilots, because “the airplanes simply blast through space faster than the human mind can think,” as one aerospace executive put it. By 1955, thanks to the money being shoveled in the electronics industry’s direction, it had revenue of $8 billion a year—the third largest in the United States, behind only autos and steel.20 THE YOUNG AND TECHNICAL The military-industrial complex ran on people power too. Ramping up R&D required thousands of physicists, engineers, mathematicians, and chemists with cutting-edge skills and a Terman-esque work ethic. Need far outpaced supply. Altogether, the nation’s universities had produced only 416 physicists and 378 mathematicians between 1946 and 1948.

…

The university was also quite young—in business for barely sixty years by the start of the Korean War—and had relatively few traditions or entrenched practices that might resist the machinations of an engineer-administrator determined to turn Stanford into the perfect laboratory for the military-industrial complex. Such license allowed Terman to not only build up basic research capacity but also move his university into even more applied work, bringing together star faculty and lab resources into the new Stanford Electronics Laboratories. The facility quickly became one of the military’s most important hubs of reconnaissance and radar R&D.

The Oil Age Is Over: What to Expect as the World Runs Out of Cheap Oil, 2005-2050

by

Matt Savinar

Published 2 Jan 2004

Cheney's house is equipped with state-of-the-art energy-conservation devices installed by Al Gore. Think they know something we don't? 104. How am I supposed to help stop the military-industrial complex that seems to have taken over the world? Are you ready to be a truly revolutionary American and put down your wallet? The military-industrial complex has taken over because we've given it our money, mostly for useless items that we don't need. Limit your consumer purchasing as much as you can and you will do more to slow down, and perhaps stop, the military-industrial complex than you will ever do by attending a peace march. Marching for peace does nothing to address our situation.

…

What are some steps that I can personally take in the next few days to begin addressing this situation?............................................................................................ 105 103. Would it be a good time to look into buying a solar-powered home, if I have the financial resource to do so? ........................................................................................ 106 104. How am I supposed to help stop the military-industrial complex that seems to have taken over the world?.................................................................................................. 106 105. How am I supposed to maintain a positive mental attitude now that I know industrial civilization is about to collapse? How should I prepare emotionally?

…

Corporations have been enthroned and an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money power of the county will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until all wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed.” -Abraham Lincoln (1864) “Fascism should more properly be called corporatism because it is the merger of state and corporate power.” -Benito Mussolini “Beware of the military-industrial complex.” -Dwight D. Eisenhower 72 The Oil Age is Over 71. Does Peak Oil have anything to do with September 11th and the war in Afghanistan? The standard story regarding 9-11 is that Osama Bin Laden and his followers were angry at the US because we have military bases located near Muslim holy sites in Saudi Arabia.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power

by

Max Chafkin

Published 14 Sep 2021

“We owe it all to the hippies,” as the futurist (and countercultural activist) Stewart Brand famously put it, positing that the “real legacy of the sixties generation is the computer revolution.” But Silicon Valley—the real Silicon Valley—had never been about subverting the military-industrial complex. Silicon Valley, in its purest form, was the military-industrial complex. Its founders weren’t dropping LSD. They were proud squares, with politics that were closer to those of David Starr Jordan than to the radicals of Stewart Brand’s imagination. The man who’d coined the phrase “traitorous eight” (and the boss whom those eight men rebelled against) was William Shockley, a physicist who worked on radar for B-29 bombers during World War II, then invented a new kind of transistor, and then, after closing his company and taking a job as a professor of electrical engineering at Stanford, picked up Jordan’s mantle to become the campus eugenicist.

…

. | Power (Social sciences) Classification: LCC HG172.T46 C43 2021 (print) | LCC HG172.T46 (ebook) |DDC 332.092 [B]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021007920 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021007921 designed by meighan cavanaugh, adapted for ebook by shayan saalabi pid_prh_5.8.0_c0_r1 CONTENTS Introduction 1. Fuck You, World 2. A Strange, Strange Boy 3. Hope You Die 4. World Domination Index 5. Heinous Activity 6. Gray Areas 7. Hedging 8. Inception 9. R.I.P. Good Times 10. The New Military-Industrial Complex 11. The Absolute Taboo 12. Building the Base 13. Public Intellectual, Private Reactionary 14. Backup Plans 15. Out for Trump 16. The Thiel Theory of Government 17. Deportation Force 18. Evil List 19. To the Mat 20. Back to the Future Epilogue: You Will Live Forever Photographs Acknowledgments Notes Image Credits Index About the Author INTRODUCTION It may seem hard to remember, but there was a time when the world seemed ready to put Silicon Valley in charge of everything.

…

He didn’t just want to break into government contracting; he wanted to take it over. He didn’t just want to persuade college administrators to root out campus political correctness; he wanted to turn fears about political correctness into an issue that could swing an American election. 10 THE NEW MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Most histories of the American tech industry begin in September 1957, at a laboratory in Mountain View, California, when a group of the country’s best young engineers at Shockley Semiconductor announced that they had decided to quit. The Traitorous Eight, as they would become known, would go on to start Fairchild Semiconductor.

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by

Grace Blakeley

Published 11 Mar 2024

Ultimately, Boeing ended up issuing $25 billion in new bonds, making its bond sale the largest of 2020 and the sixth largest on record at the time.60 The now-useless $17 billion slush fund created for Boeing and other businesses by the Treasury was hastily distributed to a wide assortment of other questionable companies, bringing them into the orbit of the US’s already sizable military-industrial complex.61 These included a company hoping to develop facial recognition software to track immigrants; a firm that relies on minimum-wage prison labor to make products for the military; and an “experimental spaceflight technology firm” already backed by wealthy venture capitalists.62 How were these decisions made?

…

The failure of Fordlândia may have been a personal disappointment for Ford, but it didn’t dent the Ford Motor Company’s growth in subsequent years, growth that rested upon the company’s close links with the US state. By the Second World War, Ford had become one of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world—and an integral part of the US military-industrial complex. By 1944, Ford was making 50 percent of all B-24 planes produced in the US, and by 1945, 70 percent, many of which were constructed at a new plant built by the company in Willow Run, Michigan.31 When the factory was constructed in 1941 it was thought to be the largest war factory in the world; and the US government had contributed $200 million to its construction.32 Ford was also, of course, helping the other side.

…

In the prewar period of “laissez-faire” capitalism, Ford was able to exercise its corporate sovereignty largely unrestrained by competition or organized labor and supported by the state—at home and abroad. During the war, the line between Ford and the states in which it operated—particularly the US and Germany—became even blurrier, as the company was absorbed into the Allied and Axis military-industrial complexes, guaranteeing significant profits. But, as I’ll show in the next section, after the war Ford was forced to confront a much more powerful labor movement and a state that encouraged the company to cooperate with labor unions. The leadership of Ford executives was perennially frustrated by the limitations this placed on the company’s formerly much less constrained sovereignty.

@War: The Rise of the Military-Internet Complex

by

Shane Harris

Published 14 Sep 2014

When the employee opened such an e-mail, it installed a digital backdoor and allowed the Chinese to monitor every keystroke the employee typed, every website visited, every file downloaded, created, or sent. Their networks had been infiltrated. Their computers compromised and monitored. America’s military-industrial complex had, in the language of hackers, been owned. And the spies were still inside these companies’ networks, mining for secrets and eavesdropping on employees’ communications. Maybe they were monitoring the executives’ private e-mails right now. “A lot of people went into that room with dark hair, and when they came out, it was white,” says James Lewis, a prominent cyber security expert and a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, who knows the details of the meeting.

…

The government cannot possibly protect or patrol all of them. But most of the world’s communications travel through equipment located in the United States. The government has a privileged position to exploit those networks, and an urgent need to protect them. To those ends, a military-Internet complex has emerged. Like the military-industrial complex before it, this new cooperative includes the makers of tanks and airplanes, missiles and satellites. But it includes tech giants, financial institutions, and communications companies as well. The United States has enlisted, persuaded, cajoled, and in some cases compelled companies into helping it fend off foreign and domestic foes who have probed the American electrical grid and looked for other weaknesses in critical infrastructures.

…

Indeed, his embrace of the historic importance of intelligence to warfare underscored his desire to protect the NSA and keep its mission intact. The timing of Obama’s speech was fitting, if unintentionally so. On January 17, 1961, exactly fifty-three years earlier, President Dwight Eisenhower had warned in his farewell address to the nation of a “military industrial complex,” whose “total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the federal government.” Eisenhower said the military of the day bore little resemblance to the one in which he served during World War II or that his predecessors in the White House had commanded.

From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

by

Fred Turner

Published 31 Aug 2006

The 1960s seem to explode onto the scene in a Technicolor swirl of personal exploration and political protest, much of it aimed at bringing down the cold war military-industrial bureaucracy. Those who accept this version of events [ 4 ] Introduction tend to account for the persistence of the military-industrial complex today, and for the continuing growth of corporate capitalism and consumer culture as well, by arguing that the authentically revolutionary ideals of the generation of 1968 were somehow co-opted by the forces they opposed. There is some truth to this story. Yet, as it has hardened into legend, this version of the past has obscured the fact the same military-industrial research world that brought forth nuclear weapons—and computers—also gave rise to a free-wheeling, interdisciplinary, and highly entrepreneurial style of work.

…

Finally, if the bureaucracies of industry and government demanded that men and women become psychologically fragmented specialists, the technology-induced experience of togetherness would allow them to become both self-sufficient and whole once again. For this wing of the counterculture, the technological and intellectual output of American research culture held enormous appeal. Although they rejected the military-industrial complex as a whole, as well as the political process that brought it into being, hippies from Manhattan to HaightAshbury read Norbert Wiener, Buckminster Fuller, and Marshall McLuhan. Introduction [ 5 ] Through their writings, young Americans encountered a cybernetic vision of the world, one in which material reality could be imagined as an information system.

…

In that sense, both he and his students agreed that the university was an information machine. Second, he suggested that this machine had a particular role to play in the ongoing cold war. “Intellect has . . . become an instrument of national purpose,” he wrote, “a component part of the ‘military-industrial complex.’ . . . In the war of ideological worlds, a great deal depends on the use of this instrument.”4 For the students of the Free Speech Movement, the university’s role as knowledge producer could not be separated from its engagement with cold war politics. Moreover, the entanglement threatened many at a deeply personal level.

The Market for Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security

by

Deborah D. Avant

Published 17 Oct 2010

Lashman, Paul, “Spicer’s Security Firm in Battle with DynCorp over $290m Deal,” Independent (4 July 2004). Lee, Dwight R., “Public Goods, Politics, and Two Cheers for the Military Industrial Complex,” in R. Higgs, ed., Arms, Politics, and the Economy: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (New York: Homes and Meier, 1990). Legro, Jeffrey, Cooperation Under Fire (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995). Lens, Sidney, The Military Industrial Complex (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1970). Leppard, David and Nicholas Rufford, “Arms to Africa: ‘no prosecution’” Sunday Times (17 May 98). Levi, Margaret Of Rule and Revenue (University of California Press, 1989).

…

The Pan-Am contract allowed the US to build airstrips on some bases in the British West Indies (acquired through the Lend-lease Program) without violating its neutral status, and the contract with TWA allowed the army to quickly train new pilots. After Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt nationalized the airline industry. Ibid., pp. 454–55. Sidney Lens, The Military Industrial Complex (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1970), pp. 129–30; James Collins Jr., The Development and Training of the South Vietnamese Army, 1950–1972 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1975), pp. 111–12; William Proxmire, Report From the Wasteland (New York: Praeger, 1970), pp. 9–10. State capacity and contracting for security 115 the US forces could not do for legal reasons or lack of resources.171 In the wake of Vietnam and the concerns it engendered over US intervention, the 1980s brought an increased focus on military training as a substitute to direct US involvement and private firms played a role here as well.

…

.: How a US Company Props up the House of Saud,” Progressive Vol. 60 (April 1996). Cynthia Arnson, Crossroads: Congress, the President, and Central America, 1976–1993 (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Press, 1993); Jonathan Feldman, Universities in the Business of Repression: the Academic–Military–Industrial Complex and Central America (Boston: South End Press, 1989). Most of these programs were in concert with established institutions, community colleges, technical institutes, or proprietary schools. Lawrence Hanser, Joyce Davidson, and Cathleen Stasz, Who Should Train? Substituting Civilian Provided Training for Military Training (Santa Monica: RAND, 1991), ch. 2. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a076.pdf.

The Profiteers

by

Sally Denton

In the end, McCone’s legacy in both government and industry would be one of global saber rattling, covert intervention, war profiteering, and billion-dollar energy and defense contracts for his associate on the West Coast. McCone was “the greatest organizer in the United States,” Steve told Jack Anderson. CHAPTER TEN Weaving Spiders “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” President Eisenhower had warned in his 1961 farewell address to the nation. “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” He cautioned against the unhealthy alliance between defense contractors, the Pentagon, and their friends on Capitol Hill. “We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes,” he continued.

…

Yet even Eisenhower could not have foreseen the near-total influence the defense industry would have over American foreign policy in the coming decades. Among the inherent ironies of Eisenhower’s grim prescience is how two of his associates—John McCone and Steve Bechtel—would become iconic figures of his envisioned military-industrial complex. “Rarely does a big Pentagon construction project surface that doesn’t have a role set aside especially for Bechtel,” a press account said of Bechtel’s twenty-first-century position as one of the country’s top defense contractors. Eisenhower had long worried about a post–World War II Japan turning toward China and Russia, sounding an alarm as early as 1954 that the shift of Indochina toward Communism would usher in such a tilt and declaring that the “possible consequences of the loss of Japan to the free world are just incalculable.”

…

Once described by President Hoover as “the greatest men’s party on earth” (a non sequitur apparently lost on Hoover, who was once described as “that swinging Bohemian . . . who was running for the presidency on a ‘dry’ platform”), the Grove is where emerging geopolitical trends are discussed in the privacy of 127 primitive camps. The most esteemed of these camps is Mandalay—named for the Kipling poem—where Steve Jr., like his father before him and his father’s partner, McCone, had been a member his entire adult life, following the patrilineal formation of the Grove. A “virtual personification of Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex,” author Joan Didion once pronounced Mandalay’s roster of members and guests. “Here, shielded from intrusion by a chain-link fence and the forces of the California Highway Patrol,” wrote Laton McCartney, “men like Justin W. Dart, William F. Buckley, George Bush, Edgar Kaiser, Jr., and Tom Watson could walk in the woods, skinny-dip in the Russian River, toast marshmallows over a fire, dress in drag for a ‘low jinks’ dramatic production, and, for a few days at least, hew to The Grove’s motto: ‘Spiders Weave Not Here.’ ” Its edict, taken from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, refers to a strict directive that prohibits Bohemians from explicitly conducting business at the Grove.

American Secession: The Looming Threat of a National Breakup

by

F. H. Buckley

Published 14 Jan 2020

How did America abandon its happy isolation to become the world’s dominant military power, with an empire of influence and strength of a kind never before seen in world history? There are three possible answers: interest-group corruption, a presidential constitution and the country’s bigness. The Military-Industrial Complex The first explanation is the form of interest-group corruption that President Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex” in his Farewell Address.5 He warned against a defense industry that teams up with the military to shape policy decisions about spending and diplomacy. As if to evidence this, defense industry stock prices fell when Trump signaled that a meeting with North Korea’s President Kim had been a success.6 By itself, the influence of the defense industry doesn’t explain why we spend more per capita on our military than other countries.

…

As if to evidence this, defense industry stock prices fell when Trump signaled that a meeting with North Korea’s President Kim had been a success.6 By itself, the influence of the defense industry doesn’t explain why we spend more per capita on our military than other countries. Every First World country has a military-industrial complex, and if our defense industry is bigger, the reason might be that our military and our defense budget are bigger. We have a military budget of over $600 billion, and about half of this is awarded to defense contractors. Like bears to honey, lobbyists are drawn to that money. The size of our defense industry is arguably not just a consequence of a large military, since causation can also work in the other direction.

…

Eisenhower, Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960–61 (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Federal Register, 1961), p. 1038. Gillian Rich, “Defense Stocks Fall As Trump Makes This Concession at North Korea Summit,” Investors Business Daily, June 12, 2018. William D. Hartung, “How the Military-Industrial Complex Preys on the Troops,” Common Dreams, October 10, 2017. Clay Dillow, “Defense Contractors Outgun Other Industries in Corporate PAC Donations,” Fortune, July 15, 2015. Charles W. Ostrom and Brian Job, “The President and the Political Use of Force,” American Political Science Review, vol. 80, no. 2 (June 1986): 541–66; Patrick James and John R.

The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991

by

Robert Service

Published 7 Oct 2015

The result is an incomparable record of deliberations and decisions in Soviet foreign policy; it is a pleasure to bring them to attention for the first time.2 Vitali Kataev of the Party Secretariat’s Defence Department assiduously documented the discussions inside the Soviet leadership on arms reduction. This material is unusually helpful in elucidating the links between the politicians and the ‘military-industrial complex’. Anatoli Adamishin, who headed the First European Department in the Foreign Affairs Ministry before his appointment as Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister, kept a diary through the 1980s and beyond. His observations offer an enthralling and largely unexamined source on the USSR’s internal politics and international relations.

…

Only a fool in the Kremlin or the White House could expect to emerge unscathed from any conflict involving nuclear ballistic missiles. Yet no serious attempt was made to end the Cold War. At best, the leaders strove to lessen the dangers. Their policies were conditioned by influential lobbies that promoted the interests of national defence. For decades the Soviet ‘military-industrial complex’ had imposed its priorities on state economic policy, and the Western economic recession that arose from the rise in the price of oil in 1973 encouraged American administrations to issue contracts for improved military technology to stimulate recovery.1 The Cold War therefore seemed a permanent feature of global politics, and pacifists and anti-nuclear campaigners seemed entirely lacking in realism.

…

Reagan’s trust in Gorbachëv grew at the summits in Geneva, Reykjavik, Washington and Moscow in 1985–1988. Bush was Gorbachëv’s friend from the Malta summit of 1989 onwards. The leaders in Moscow and Washington had to find ways to carry their political establishments along with them. For years before the mid-1980s it had been argued that the American military-industrial complex had no interest in moves towards global peace. The heavy industry ministries and army high command in the USSR were similarly regarded as eternally attached to militarist objectives.9 Reagan and Bush were conscious of the scepticism among American conservatives about the agreements that they wanted to finalize with the Kremlin.

Servant Economy: Where America's Elite Is Sending the Middle Class

by

Jeff Faux

Published 16 May 2012

Cold War strategy, reminded the foreign policy elite of the importance of U.S. economic power: “One of the most significant lessons of our World War II experience was that the American economy, when it operates at a level approaching full efficiency, can provide enormous resources for purposes other than civilian consumption while simultaneously providing a high standard of living.”19. For Paul Nitze, the principal author, “purposes other than civilian consumption” meant the defense budget. This “military Keynesianism” was the perfect economic engine to fuel the ambitions of U.S. policy makers. Inasmuch as a large part of the budget of the military-industrial complex was secret, even from government auditors, decisions were hidden under a cloak of national security. Military spending was no less politically motivated than civilian spending was. Bases and contracts were allocated to keep congressional support for the big Department of Defense budget.

…

Like Kotkin and Slaughter, he believes that the U.S. tolerance for immigration will keep the country supplied with workers and low labor costs. For the nation-state, he says, per capita income is not what is important. He is indifferent to the fate of the U.S. standard of living. The key, he believes, is to keep total income high enough to support the military-industrial complex. Friedman too is not worried about China. Like the other happy-face forecasters, he believes that China is permanently hooked on U.S. markets and will always need us. For the next few decades, at least, China’s navy is too weak and its military electronics too primitive to undercut our strategic position in the Pacific.

…

In its 2011 final report to Congress after three years of study, the Commission on Wartime Contracting made a conservative estimate that the waste, fraud, and abuse in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars might come to sixty billion dollars, but the commission didn’t know for sure because it never could get a good accounting. There is no stomach in the political parties for a knock-down, drag-out fight with the military-industrial complex. Defense contractors are important employers in every state and in a majority of congressional districts. They hire legions of lobbyists armed with generous campaign contributions. The military reaches into virtually every nook and cranny of American consciousness. The Pentagon is a major financier of universities through research grants and scholarships.

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by

Chris Impey

Published 12 Apr 2015

With too much government and military control, technologies can’t reach their full potential. President Dwight Eisenhower used his farewell address to warn of the dangers of the “military-industrial complex.”22 It’s ironic that this five-star general and two-term president—the quintessential Washington insider—issued such a clarion call against concentration of influence within and around the government. He said: “We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for disastrous use of misplaced power exists, and will persist.”23 The analogy between access to space and access to information seems to break down.

…

Amateur Computerist, vol. 2, no. 2, and “A Brief History of the Internet” by B. M. Leiner et al. 2009, online at http://www.internetsociety.org/internet/what-internet/history-internet/brief-history-internet. 22. “Eisenhower’s Warning: The Military-Industrial Complex Forty Years Later” by W. D. Hartung 2001. World Policy Journal, vol. 18, no. 1. 23. Unwarranted Influence: Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Military-Industrial Complex by J. Ledbetter 2011. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 5: Meet the Entrepreneurs 1. “Private Space Exploration a Long and Thriving Tradition” by M. Burgan 2012. In Bloomberg View, online at http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2012-07-18/private-space-exploration-a-long-and-thriving-tradition. 2.

…

As they orbited the Earth, many commented on the seamlessness of a planet where no political or cultural boundaries were visible. The iconic image of the fragile Earth hanging in the blackness of space—a blue marble—helped spur the environmental movement in the late 1960s. It is indeed ironic that a supreme feat of the military-industrial complex was embraced by counterculture activists.10 When Frank Sinatra performed “Fly Me to the Moon” on his TV show in 1969, he dedicated it to the astronauts who had “made the impossible possible.” The song’s jaunty melody perfectly captured the lightness of the people who had slipped the bonds of Earth.

The Politics Industry: How Political Innovation Can Break Partisan Gridlock and Save Our Democracy

by

Katherine M. Gehl

and

Michael E. Porter

Published 14 Sep 2020

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”39 What Eisenhower foresaw was a powerful alliance between America’s military and the defense industry. He believed that if this alliance were to be left unchecked, it would perpetuate a build-buy defense-spending cycle that would outpace actual need and create products designed to serve the goals of the complex over the goals of the “customer” (which should be our national security interests). The military-industrial complex would create a supply of defense goods for supply’s sake and, like many other modern American sectors, become too big and too powerful to fail.

…

The need to reform our political system to create healthier competition and better outcomes remains unchanged. A Thriving Political-Industrial Complex In January 1961, in his farewell address, President Dwight D.Eisenhower, a Republican, warned the nation of the threat and misplaced influence of what he called the military-industrial complex: “This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development.

…

See campaign contributions; donors consultants, 7, 31, 38, 42, 187n44 Coons, Chris, 47 Crane, David, 176 cross-partisan approach electoral innovation and, 157–158 Nebraska’s legislative reform with, 164–165 Curry, James M., 193n63 customers average voters as, 27 citizens’ lack of power as, in 1870s, 103 duopoly control and, 23 Final-Five Voting and power of, 130 Five Forces framework on, 20 healthy competition and, 21 military-industrial complex and, 38 nonvoters and, 27 partisan takeover of Congress and, 60 party-primary voters as, 24–25 politics industry and power of, 24–28, 25 special interests and donors as, 25–27 Cutler, Eliot, 50 Dana, Richard Henry III, 204n61 dark money, 26 data analytics, 31, 184n16 Davidson, Roger, 161 Davis, Gray, 149 Dean, Howard, 152 debates, in presidential campaigns, 31, 41–43, 63, 188nn3, 13 Debs, Eugene, 108–109 deficit financing, 67–69 Delaney, John, 209n2 Delaware election machinery in, 46–48 sore-loser law in, 48 Delaware way, 47 democracy African Americans’ participation in, after the Civil War, 101 belief in change and need for constant reinvention of, 95 citizens’ power to reform politics and restore, 96 Constitution with formal blueprint for, 95 duopoly control as problem in, 23 election of representatives in, 94, 95 plurality voting’s impact on, 51 as political innovation, 94–95 political parties’ role in, 19 politics industry and decline of, 39, 66 Progressive Era reforms and, 97–98, 110 public loss of faith in, 72, 196n10 Reconstruction and, 101 reengineered elections and legislative machinery and, 141 Democracy Found, 156, 174 Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, 32 Democratic National Committee (DNC), 42 Democratic Party Affordable Care Act and, 85–86 California primary reform and, 149, 150–151 closed primaries and, 183n10 committee control of Congress and, 56, 61 congressional bill process and, 60, 61 congressional rules and, 136 cross-partisan approach to electoral innovation and, 157–158 declining percentage of moderates in, 67, 68 deficit financing used by, 69 division of voters by, in Gilded Age, 106–108 Federal Election Commission members from, 35 Gilded Age and, 96, 201nn33, 45 Hastert Rule and bill support by, 54 Hayes-Tilden 1876 election and, 101–102 immigration reform and, 73–74, 196nn11, 12, 14, 196n15, 196–197n18, 197n22 machinery of political system engineered by, 3 Maine’s ranked-choice voting and, 150, 152 newspapers backed by, 104, 109, 200n29 partisan takeover of Congress and, 55–59 as part of duopoly in politics industry, 7 percentage of voters’ identification with, 71, 71 political machines in, 104, 201n33, 213n60 Populist Party and, 104–105 presidential debate rules and, 42, 63 public disillusionment with, 70–71 rivalries between Republicans and, in 1870s, 103 rules written by, 18 Social Security Act passage and, 84 spoiler effect and, 51 top-five primaries and, 122, 123 Trump’s election and presidency and adjustments within, 37 volatile swings of voter sentiment and, 71–72 voters and competition in elections and, 119 See also duopoly; two-party system Democratic Party of Washington v.

The Age of Illusions: How America Squandered Its Cold War Victory

by

Andrew J. Bacevich

Published 7 Jan 2020

Applied to military affairs, traditional terms such as “deter,” “defend,” and “destroy” meant something concrete and specific. “Shaping,” by comparison, was amorphous. Requiring nothing in particular, it could permit just about anything. It promised to enlarge American freedom of action. As far as the national security apparatus and all those dependent upon the largesse of the military-industrial complex were concerned, this was its chief attribute. Here was a gift that promised to keep on giving. As it embarked upon the post–Cold War era, the United States faced few pressing dangers. Risks appeared manageable. In such circumstances, self-restraint seemed tantamount to timidity. So in national security circles, the collective mindset began tilting toward activism.

…

Yet he did little to curb American militarism. Global leadership remained largely synonymous with the use of force. The war machine churned on, with most citizens all but numb to its existence. In the year of Obama’s birth, President Dwight D. Eisenhower had decried the rise of what he called the military-industrial complex. In doing so, Ike performed a last great service for his countrymen. Yet a phrase coined in 1961 does not adequately describe the militarized mindset to which Washington had succumbed since the end of the Cold War. In contrast to Ike, Obama did next to nothing to educate Americans about the dangers this mindset poses.

…

First, Clinton’s something-for-everyone set of promises represented the functional equivalent of Donald Trump’s widely ridiculed claim, “Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it.”48 Clinton’s campaign strategists assumed that testifying to her own mastery of that system held one key to electoral success. So whatever the problem, Clinton had readily at hand her own plan to “fix it”—a chorus of dog whistles designed to resonate with just about every group of potential supporters: workers, women, the elderly, vets, people of color, gays, Jews, the military-industrial complex, and even big business. Yet in marketing their competing “I alone” claims, both candidates were in effect endorsing the post–Cold War paradigm of the U.S. president as maximum leader and ultimate source of salvation. Second, if Clinton’s vision was stupefyingly grandiose, it was also strikingly banal, its contents carefully vetted by Democratic think tanks and pollsters.

Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

by

Serhii Plokhy

Published 1 Mar 2018

The continuing Cold War, which led the West to impose embargoes on the sale of advanced technologies to the Soviet Union, lent weight to their argument. The government-funded military-industrial complex was eager to move into the economic sphere while maintaining its monopoly on high-tech industries and products. Many, including Gorbachev, saw this as the most effective solution to the country’s economic troubles. THE DESIRES, fears, and aspirations of the Soviet military-industrial complex and its scientific wing were articulated to the congress by Anatolii Aleksandrov, the president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. The fact that he was the first representative of the Soviet intelligentsia to address the congress underscored the symbolic importance of his position in the party hierarchy as well as the hopes that the new leaders were now placing in the scientific establishment.13 A tall man with a long face, a big nose, and a shaved, egg-shaped head, Aleksandrov had turned eighty-three earlier that month.

…

Nuclear power stations like the one in Chernobyl were no longer the responsibility of Yefim Slavsky, the all-powerful head of the Ministry of Medium Machine Building, which was the hub of the Soviet nuclear program and its military-industrial complex. Slavsky’s ministry was a virtual empire, a state within a state with its own manufacturing plants capable of producing most of the equipment needed for the nuclear industry. Those plants had been used to build the nuclear power station at the Sosnovyi Bor settlement near Leningrad, where the first reactor began producing electrical energy in December 1973. But soon after that the construction of nuclear power stations had become the responsibility of the Ministry of Energy and Electrification, which was not part of the military-industrial complex; it had a poor manufacturing base of its own and none of the political clout that came with Slavsky’s power and prestige.

…

Rumor had it that he went so far as to declare that his reactors were safe enough to be installed on Red Square.18 That never happened, but after the new reactor was tested, at a plant in Slavsky’s ministry, it was deemed safe enough to be transferred to the Ministry of Energy and Electrification, which had no experience with nuclear energy. Few doubted the positive effect that the fusion of science and technology would have on the country as a result of the military-industrial complex’s stewardship of the nuclear industry. Aleksandrov’s RBMK reactors were placed all over the European part of the Soviet Union, producing much-needed clean energy for the country. With a capacity of 1 million megawatts of electrical energy per unit, they were more powerful than their Soviet competitors, the VVERs (or Water-Water Energy Reactors, meaning water-cooled and water-moderated), which had been produced starting in the early 1970s.

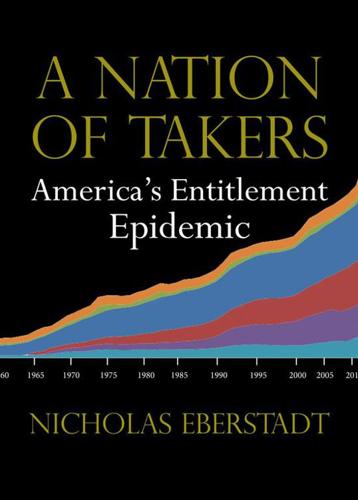

A Nation of Takers: America’s Entitlement Epidemic

by

Nicholas Eberstadt

and

Nick Eberstadt

Published 18 Oct 2012

Commentators on the right and left of the U.S. political spectrum decry what they call the American “national security state” (a term that has acquired a marked opprobrium in the decades since its early and decidedly more neutral Cold War coinage). And concern about excessive defense spending has hardly been a preserve of fringe extremists. No less a figure than Dwight Eisenhower, architect of the D-Day invasion and onetime supreme commander of NATO forces, warned of the dangers of a “military-industrial complex” in his famous 1961 farewell presidential address.62 A healthy measure of informed public skepticism toward any and all proposed military expenditures is not only suitable but essential for open democratic societies. A free people, after all, will jealously guard against impingements upon their liberties—including those arising from excessive, wasteful, or unwise outlays in the name of national defense.

…

U.S. government outlays on entitlements do not merely exceed those for defense nowadays, they completely overshadow defense outlays. Increasingly, moreover, our seemingly insatiable national hunger for government transfer payments to individual citizens stand to compromise our present and future capabilities for military readiness. In 1961, the year of Eisenhower’s admonition about the military-industrial complex, America was devoting close to two dollars on defense for every dollar it provided in domestic entitlement payments.63 Up to that point, defense expenditures had routinely exceeded any and all allocations for social insurance and social welfare throughout American history.64 But in 1961 a geometric growth of entitlement payments was just commencing.

…

But why, exactly, should America’s current and (heretofore) future military commitments be regarded as “unaffordable”? In 2010 the national defense budget amounted to 4.8 percent of current GDP (see Figure 28). As a fraction of U.S. national output, our military burden was thus lower in 2010 than in almost any year during the four-plus decades of the Cold War era. In 1961—the year of Eisenhower’s “military industrial complex” address—the ratio of defense spending to GDP was 9.4 percent68; in other words, almost twice as high as in 2010. Put another way: America’s overall military burden was nearly twice as high in 1961 as in 2010. Americans may have deemed our defense commitments in 2010 to be ill-advised, poorly purchased, or otherwise of questionable provenance—but as a pure question of affordability, the United States is in a better position to afford our current defense burden than at virtually any time during the Cold War era.

Stealth

by

Peter Westwick

Published 22 Nov 2019

Stealth was not just a product of the 1970s but rather drew on decades of R&D, which itself reflected a national willingness to make long-term investments in uncertain ventures. And those investments came from both the public and the private sectors. Stealth represented a vast integration of the state and private industry, what is commonly called the military-industrial complex. In order to demonstrate the superiority of an unfettered free market over a command economy in the Cold War, the US embraced a strong public-private partnership. The Cold War military-industrial complex often carries negative connotations, of a corrupting intrusion of the state into private enterprise and, in the other direction, of private interests into public policy. And indeed Stealth, as some observers argued, could seem like a waste of money and brainpower, enabled by official secrecy and encouraged by pork-barrel politics, all just to produce yet another weapon and a new lap of the arms race.

…

In his farewell address, in January 1961, he issued a dire warning about the emergence of “a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions,” which the old Army general viewed as a dangerous incursion both by the state into private enterprise and by private interests into public policy. Eisenhower gave it a name: the “military-industrial complex,” thereafter usually invoked in the pejorative sense Ike intended.9 More recent scholars have taken a more positive view of the military-industrial complex, framing the public-private partnership as a remarkable engine driving technological innovation. What has been called the “hidden developmental state,” “entrepreneurial state,” or “innovation hybrids” was every bit the match of Japan’s vaunted Ministry of International Trade and Industry, or MITI, which was heralded in the early 1980s, just when Stealth was emerging, as the reason for Japan’s high-tech lead over the US.10 Japan’s MITI, of course, promoted commercial consumer technologies, whereas Stealth projected military strength but did little for economic competitiveness.

…

One is the long-haired, tie-dyed hippie; the other is the aerospace engineer, in short-sleeved white button-down, skinny dark tie, and crew cut, with pocket protector and slide rule. The images seem orthogonal: the hippie a free spirit, flipping the bird to authority and denouncing the military-industrial complex; the aerospace engineer dedicated, conservative, and patriotic. On one side, romantic hedonism, turning on and dropping out; on the other, rocket-science rationality and can-do discipline. Norman Mailer saw it that way; after the moon landing, he mocked the hippies: “You’ve been drunk all summer… and they have taken the moon.”12 But the realms of the hippie and the engineer were not completely opposed.

The Dream Machine: The Untold History of the Notorious V-22 Osprey

by

Richard Whittle

Published 26 Apr 2010

—Steve Weinberg, Dallas Morning News “Drawing on more than 200 interviews, Whittle reconstructs the Pentagon strategy sessions and covert Capitol Hill meetings that kept the Osprey going despite crashes, production delays, and billion-dollar cost overruns… . a fine book.” —Dale Eisman, The Virginian-Pilot “Whittle takes the reader behind the closed doors of the military-industrial complex and into the cockpits of the Ospreys that went down, telling a story as gripping as it is important.” —Aviation Maintenance Whittle “pulls no punches, but takes no cheap shots either. The result is a truly readable book that spins a fascinating yarn of science, politics, and intrigue.”

…

They were willing to put money into a program in order to advance technology that might be an advantage on the battlefield.” Since World War II, the military’s “patient capital” has led to innumerable, often stunning advances in technology. It also spawned and sustains what President Dwight D. Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex.” Eisenhower was referring to the web of political and personal relationships between industry representatives and military officials that germinates when they do business or collaborate on projects. As institutions, defense companies and the government are often at odds over the costs and capabilities of weapons and other equipment; there is plenty of friction in the relationship.

…

Sometimes it can blur the line between the best interests of industry and the nation. Eisenhower, who as a five-star general had led the Allies in defeating Nazi Germany, warned of this larger danger in a farewell address as he left the White House in 1961. “We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” Eisenhower declared. He also noted that the “conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience.” During the Great Depression, the U.S. military wasn’t immense and the aircraft industry was tiny. Both would grow rapidly with the approach of World War II, but for most of the decade preceding that conflict, America’s armed forces numbered around 250,000 active-duty personnel, compared to roughly 1.4 million today, and the entire military budget was under $1 billion—less than one five-hundredth of its size in recent years, without adjusting for inflation.

10% Less Democracy: Why You Should Trust Elites a Little More and the Masses a Little Less

by

Garett Jones

Published 4 Feb 2020

People need their phones and need their electricity, and there’s a lot of monopoly power there to exploit, so regulated businesses have a strong incentive to pressure any regulator for higher prices and lax quality requirements. The theory of regulator capture has some overlap with President Dwight Eisenhower’s worries about the military-industrial complex, which Ike discussed in a shocking and powerful speech toward the end of his presidency. He wanted to tell Americans that they needed to be vigilant about monitoring both the military and military contractors. He warned that in the post–World War II era, this conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience.

…

The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. . . . In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.¹⁶ Note that top military officials and top electricity regulators have something in common: they’re both interacting closely with the same small number of large businesses on a regular basis, and it’s often the government official’s job to give bad news to those large businesses.

…

The cynical, and thus plausible, case for electing electricity and telecom regulators is that the fear of looming elections will discourage regulators from selling out completely to the industries they regulate. The power of voters is a form of what Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith used to call “countervailing power”: power that has a chance to stand up to dangerous forces. But just because there’s a problem doesn’t mean there’s an easy solution. The risks of the military-industrial complex that Ike warned about are real, but that doesn’t mean we should be voting for our admirals. There are benefits and costs to democratic checks on insider power, and as we’ve already seen, it’s pretty likely that in the case of judges, central bankers, and city treasurers, we’re probably better off with the devil of insider influence than with the devil of democratic influence.

Masters of Mankind

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 1 Sep 2014

That a situation such as this is fraught with perils is obvious. From the point of view of the liberal technocrat the solution to the problem lies in strengthening the federal government (the “radical centralizer” goes further, insisting that all power be vested in the central state authorities and the “vanguard party”). Only thus can the military-industrial complex be tamed and controlled: “The filter-down process of pump-priming the civilian economy by fostering ever-greater economic concentration and income inequality must be replaced by a frank acceptance of federal responsibility to control the tide of economic bigness, and to plan the conservation and growth of all sectors of the economy and the society.”48 The hope lies in skilled managers such as Robert McNamara, who “has been the unflinching hero of the campaign to reform and control the ‘Contract State.’”49 It is probably correct to suppose that the technostructure offers no greater hope than McNamara, who has clearly explained his own views regarding social organization: “Vital decision-making, in policy matters as well as in business, must remain at the top.

…

The above prospect, Nossiter concludes from his study, is this: Powerful industrial giants eagerly pressing for more military business, Pentagon defense planners eager to get on with the new weapons production, Congressmen whose districts profit directly from the anticipated contracts, and millions of Americans from the blue collar aircraft worker to the university physicist drawing their paychecks from the production of arms. About to take over the White House is a new president whose campaign left little doubt of his inclination to support the ABM and other costly arms spending while tightening up on expenditures for civilian purposes. This is the military-industrial complex of 1969. Of course, any competent economist can sketch other methods by which government-induced production can serve to keep the economy functioning. “But capitalist reality is more intractable than planners’ pens and paper. For one thing too much productive expenditure by the state is ruled out.

…

Similarly, the American people “understand” the necessity for the grotesquerie of the space race, which is quite susceptible to Madison Avenue techniques and thus, along with the science-technology race in general, serves as “a transfigured, transmuted and theoretical substitute for an infinite strategic arms race; it is a continuation of the race by other means.”53 It is fashionable to decry such analyses—or even references to the “military-industrial complex”—as “unsophisticated.” It is interesting, therefore, to note that those who manipulate the process and stand directly to gain by it are much less coy about the matter. There are some perceptive analysts—J. K. Galbraith is the best example—who argue that the concern for growth and profit maximization has become only one of several motives for management and technostructure, that it is supplemented, perhaps dominated, by identification with and adaptation to the needs of the organization, the corporation, which serves as a basic planning unit for the economy.54 Perhaps this is true, but the consequences of this shift of motivation may nevertheless be slight, since the corporation as planning unit is geared to production of consumer goods55—the consumer, often, being the national state—rather than satisfaction of social needs, and to the extension of its dominion in the organized international economy.

China's Future

by

David Shambaugh

Published 11 Mar 2016

At the current rate of accelerating growth in the state R&D budget (up from 1.6 to 2.1 percent since 2012), China could overtake the United States around 2022, when it will spend more than $600 billion annually. China has a huge R&D network in terms of personnel and institutions.53 The government has a sprawling bureaucracy of national laboratories under most of the State Council ministries and within the nation’s large military-industrial complex. For decades China’s military industries were chronically incapable of innovation (imitation even gave them severe problems), but that is changing rapidly. As the work of expert Tai Ming Cheung has demonstrated, China’s civil-military integration and defense technological innovation is really taking off.54 However, innovation requires much more than government investment in R&D—it fundamentally requires an educational system premised on critical thinking and freedom of exploration.

…

Politically, it would involve an even greater tightening and crackdown—Hard Authoritarianism morphing into restored totalitarianism. Coercion and control (already reinforced) would be stepped up. Social and ideological conformity would be enforced by a pervasive state security apparatus. In terms of the economy, privatization would give way to renationalization and collectivization by the state. The military-industrial complex would become the favored economic sector. Strict controls would be placed on the labor market. Nationalism would spike, with possible aggressive moves against Japan and other neighbors. While this possibility is not unimaginable, I judge it unfeasible given the already tremendous growth and dominance of the private sector of the economy and the relative freedoms that Chinese citizens do enjoy.

…

This was literally on display in massive military parades in Tiananmen Square on October 1, 2009 and September 3, 2015 (the former to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the PRC and the latter to commemorate the seventieth anniversary of the end of World War II). China’s military power is not a new phenomenon; it has steadily been built over the past quarter century. Fueled by a booming economy, China’s military-industrial complex has been the beneficiary of annual budget increases in excess of GDP growth. From 1998 to 2007 China’s GDP has averaged 12.5 percent growth, but its (official) defense spending grew at an average of 15.9 percent.44 Since then it has leveled off at between 10–12 percent annual increases.

The Global Minotaur

by

Yanis Varoufakis

and

Paul Mason

Published 4 Jul 2015

This is what happened in Argentina in the late 1990s, when, in the absence of a surplus recycling mechanism, the country’s deteriorating trade deficit eventually took its toll on the fixed exchange rate with the US dollar. The same negative dynamic is currently at play within the eurozone – see chapter 8. The two surplus recycling mechanisms characteristic of the United States since the Second World War have been the simple transfer union instituted by the New Deal in the late 1930s and the complicated military-industrial complex, which developed in the 1940s. The former works straightforwardly, by ensuring that the unemployment and health benefits of deficit states are paid for by Washington, dipping into taxes raised in surplus states, e.g. California and New York. The second mechanism, too, turns on a political arrangement: whenever a conglomerate like Boeing receives a large Pentagon contract to build a new fighter jet or missile system, it is stipulated that some of the production facilities must be located in depressed, deficit states.

…

Convinced that ‘free market capitalism’ had to be planned meticulously by Washington, and in a manner not too dissimilar to the successful running of the war economy, they sought to project onto a global canvas the successful recipe that had brought America out of the doldrums. Intent on winning the peace, they sought to empower US business through a combination of New Deal-inspired interventions and the technological advances achieved by the military-industrial complex. The four men were: • James Forrestal, secretary of defence (and previously secretary of the navy) • James Byrnes, secretary of state • George Kennan, director of policy planning staff at the State Department and renowned ‘prophet’ of Soviet containment • Dean Acheson, leading light in all major post-war designs (the Bretton Woods agreement, the Marshall Plan, the prosecution of the Cold War, etc.) and secretary of state from 1949 onwards.

…

Although most of the New Dealers had been influenced by the writings of John Maynard Keynes, and had taken note of his crucial advice not to trust markets to organize themselves in a manner that can bring about prosperity and stability, the Cold War, which they had to pursue at the same time as managing the Global Plan, and their closeness to the military-industrial complex prevented them from seeing as clearly as Keynes had the imperative of creating a formal, cooperative system for recycling surpluses. Many observers note the deep chasm separating the New Deal mindset from European, or British, Keynesianism. To begin with, whereas Keynes had become convinced that global capitalism required a cooperative, non-imperial global surplus recycling mechanism (GSRM), the New Dealers both wanted and were obliged to tailor their Global Plan in the context of Cold War imperatives and in clear pursuit of American hegemony.

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 14 Sep 2015

Today the agency maintains headquarters in an unmarked glass and steel building four miles from the Pentagon, in Arlington, Virginia. DARPA’s director reports to the Office of the Secretary of Defense. In its fifty-seven years, DARPA has never allowed the United States to be taken by scientific surprise. Admirers call DARPA the Pentagon’s brain. Critics call it the heart of the military-industrial complex. Is DARPA to be admired or feared? Does DARPA safeguard democracy, or does it stimulate America’s seemingly endless call to war? DARPA makes the future happen. Industry, public health, society, and culture all transform because of technology that DARPA pioneers. DARPA creates, DARPA dominates, and when sent to the battlefield, DARPA destroys.

…

The revelation that the university was working with the Defense Department on nuclear weapons work had an explosive effect on an already charged student body. “The University has proven that it is not a neutral institution,” declared the antiwar group Radical Union, “but is actively supporting the efforts of the military-industrial complex.” One article after the next alleged malevolent intentions on the part of Professor Slotnick and the dean of the Graduate College, Daniel Alpert, in having tried to conceal from the student body the true nature of the computer. “The horrors ILLIAC IV may loose on the world through [the] hands of military leaders of this nation” could not be underestimated, the Daily Illini editorialized.

…

Why is the Defense Science Board so focused on pushing robotic warfare on the Pentagon? Why force military personnel to learn to “trust” robots and to rely on autonomous robots in future warfare? Why is the erasure of fear a federal investment? The answer to it all, to every question in this book, lies at the heart of the military-industrial complex. Unlike the Jason scientists, the majority of whom were part-time defense scientists and full-time university professors, the majority of DSB members are defense contractors. DSB chairman Paul Kaminski, who also served on President Obama’s Intelligence Advisory Board from 2009 to 2013, is a director of General Dynamics, chairman of the board of the RAND Corporation, chairman of the board of HRL (the former Hughes Research Labs), chairman of the board of Exostar, chairman and CEO of Technovation, Inc., trustee and advisor to the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, and trustee and advisor to MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory—all companies and corporations that build robotic weapons systems for DARPA and for the Pentagon.

Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed

by

Ben R. Rich

and

Leo Janos

Published 1 Jan 1994

We’d delay an attack five minutes knowing they’d have to stop firing to cool down their guns—then we’d come in and hit them. We drew all the demanding high-precision bombing of the most heavily defended, highest-priority targets. The powers that be decided to use B-52s to pour down bombs on the big North Taji military industrial complex. But it was protected by surface-to-air missiles that could knock down our bombing armada. So we went in the night before and took out all fifteen missile sites using ten stealth airplanes. They never saw us coming. That mission won us a standing ovation from General Schwarzkopf and the other brass monitoring us back in the coalition war room.

…

Ultimately, he ran all the spy plane and satellite operations for the agency until the last months of the Eisenhower administration in late 1959, when Allen Dulles put him in charge of organizing a group of Cuban émigrés into a rag-tag battle brigade that would attempt to invade the island at the Bay of Pigs. But in the early days of the U-2, he was a mysterious figure to most of us, part of a complicated working arrangement involving the agency, Lockheed, and the Air Force that was unprecedented in the annals of the military-industrial complex. The operational plan for deploying our highly secret airplane was approved personally by President Eisenhower. Under this plan, the CIA was responsible for overseeing production of the airplane and its cameras, for choosing the bases and providing security, and for processing the film, no mean feat since the special, tightly wound film developed by Eastman Kodak would stretch from Washington halfway to Baltimore on each mission.

…

And at the end of the line we were actually able to refund about 15 percent of the total U-2 production cost back to the CIA and in the bargain build five extra airplanes from spare fuselages and parts we didn’t need because both the Skunk Works and the U-2 had functioned so beautifully. This was probably the only instance of a cost underrun in the history of the military-industrial complex. The first group of six U-2 pilots recruited from the SAC fighter squadrons showed up at the Skunk Works in the fall of 1955 wearing civilian clothes and carrying phony IDs. They spent three days getting a thorough briefing on the airplane before flying off to the secret base to begin training with our test pilots.

Rethinking Camelot

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 7 Apr 2015

Their attitudes toward the man who escalated the war from terror to aggression are perhaps more surprising, though it should be recalled that the picture of Kennedy as the leader who was about to lead us to a bright future of peace and justice was carefully nurtured during the Camelot years, with no little success, and has been regularly revived in the course of the critique of the Warren report and the attempts to construct a different picture, which have reached and influenced a wide audience over the years. Within both categories, some have taken the position that JFK truly departed from the political norm, and had become (or always was) committed to far-reaching policy changes: not only was he planning to withdraw from Vietnam (the core thesis), but also to break up the CIA and the military-industrial complex, to end the Cold War, and otherwise to pursue directions that would indeed have been highly unpopular in the corridors of power. Others reject these assessments, but argue that Kennedy was perceived as a dangerous reformer by right-wing elements (which is undoubtedly true, as it is true of virtually everyone in public life).

…

In this case, as noted earlier, it is largely grassroots elements (often called “the left”36) that have taken up the cudgels in the defense of President Kennedy, on the theory that he was assassinated by powerful groups that perceived him to be a dangerous “radical reformer.” These dark forces are variously identified as the CIA, the far right, militarists, etc. Many on the left accept this perception as accurate, holding that JFK was about to withdraw from Vietnam, end the Cold War and the arms race, smash the CIA to a thousand pieces, dismantle the military-industrial complex, and set the country on a course towards peace and justice. Others hold only that the assassins exaggerated his reformist zeal. Some popular variants bring in other assassinations, real and alleged. The plot also becomes intertwined with theories of a “secret team” that has “hijacked the state,” bringing us to our current sorry pass.

…