mittelstand

description: a term used in the German-speaking world to describe small and medium-sized enterprises that form the backbone of the German economy

52 results

Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power

by

Patrick Major

Published 5 Nov 2009

Yet significant numbers of smallholding ‘new farmers’, beneficiaries of the 1945 land reform, were also heading west.⁴⁴ The Mittelstand felt next in line. Artisans, businessmen, and factory owners left in massive numbers in 1953, following the introduction of Manual Production Collectives. Significantly, neither farmers nor the Mittelstand were natural candidates for flight. Farmers were tied to the land, and the commercial sector to its businesses.⁴⁵ Members of the ‘old’ Mittelstand of artisans and shopkeepers knew there was little call for them in the West, so it was all the more remarkable when these groups departed.

…

Yet, as the GDR aged and the outlet to the West was closed, this pattern switched. By 1970 Berlin had reached pole position, at 0.66 per cent, followed by Potsdam at 0.41 per cent, a pattern repeated with minor changes ten years later in 1980. BAB, DA-5/5999. 20 Behind the Berlin Wall intelligentsia, the Mittelstand , and women of all classes, than it was for other groups.¹⁰⁴ Furthermore, the special status of travel petitions is revealed by the fact that from the 1970s the security section of the SED’s Central Committee, in conjunction with the MfS, became the arbiter on travel and emigration. Indeed, the vast majority of its surviving files consist of alphabetized special pleading by citizens to travel west.

…

As long as the German question remained open, uncommitted East Germans might harbour hopes that the socioeconomic clock could be turned back. The SED’s Party Information labelled this the ‘it-could-turn-out-different’ attitude, a form of domestic Hallstein doctrine ascribed to wide sections of the rural population, the Mittelstand and intelligentsia. Pre-emptively, therefore, the party would follow each diplomatic initiative with a barrage of media coverage, and its agitators engaged the population in ‘discussions’, at the workplace or on the doorstep, often based on readings of the current diplomatic notes. Invariably, a party spokesperson was on hand to give the official view.

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by

John Kay

Published 2 Sep 2015

Although there are niche producers such as these in the USA, Italy and Japan, two-thirds of the ‘hidden champions’ come from Germany and the German-speaking areas of Switzerland and Austria. These ‘hidden champions’ are the stars of the Mittelstand, the small and medium-size companies that are the basis of Germany’s extraordinary strength in manufacturing exports. German exports per head are four times those of the USA and more than ten times those of China. The businesses of the Mittelstand are predominantly family-owned. ‘Hidden champions’ have little need of external capital – like quoted companies, they typically generate more than sufficient cash for their investment needs from their internal resources.

…

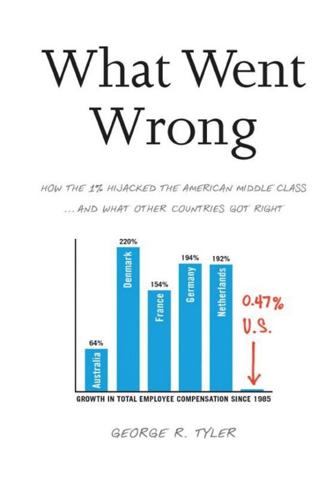

Since these figures relate to gross income, and benefits and top rates of taxation increased everywhere, the equalising effect was even greater than these figures suggest. Many people may be surprised that Germany in 1970 was significantly less equal than Britain, France or the USA. The main explanation is the success of that country’s largely family-owned Mittelstand, or medium-size business sector, which I will discuss further in Chapter 5. The egalitarian trends did not continue. In France and Germany they simply came to an end; these measures of income inequality have not changed since 1970. In Britain and the USA incomes of the top 1 per cent and 0.1 per cent have increased sharply.

…

WestLB, the Landesbank of North Rhine-Westphalia, was one of the prime European casualties of the global financial crisis, and the federal government took control of Commerzbank, the second-largest German bank. Yet the co-operative and savings bank sector, which provides around two-thirds of lending to the Mittelstand and is willing to provide long-term debt finance of a kind and on terms virtually unavailable to small business in Britain and the USA, emerged largely unscathed. Throughout financialisation, global investment banks have sought to promote the development of capital markets in debt and equity in Germany and have frequently found support for this objective from the European Commission.

The Rare Metals War

by

Guillaume Pitron

Published 15 Feb 2020

For a more detailed explanation, see the French Geological Survey’s public report: ‘Panorama du marché du tungstène’ [‘View of the Tungsten Market’], BRGM, July 2012. Interview with Chris Ecclestone, 2016. The Mittelstand may have won the battle, but they did not win the war. China has a keen interest in some of Germany’s star industrial robots, such as KUKA. See ‘Allemagne: le “Mittelstand” face à l’offensive chinoise’ [‘Germany: the Mittelstand faces the Chinese offensive’], Le Monde, 4 June 2016. Graphene’s applications are astounding: bendy mobile phones, see-through laptops, ultra-powerful nanoprocessors, or nanochips that can be inserted into the human body to detect cancers, and so on.

…

The Chinese feel like rare earths are to them what vineyards are to the French.’26 This strategy of moving up the ladder is not limited to rare earths. As early as the 1990s, a wave of concern rippled through the fabric of German small-to-medium-sized enterprises (known as the Mittelstand) specialising in the manufacture of machine tools. (Machine tools are used for factory work automation, from basic milling machines to ultra-connected machining centres.) The Mittelstand acted pre-emptively by gradually replacing humans with robots, allowing it to remain competitive to the extent that German industry still represents 30 per cent of the country’s GDP.27 Except that industrial robots require terrific amounts of tungsten.

…

‘They drove down tungsten prices [from 1985 to 2004],29 hoping that Westerners concerned about getting their raw materials at the best price would buy exclusively from the Chinese, and that competing mines would shut down.’30 We can guess what could have happened next: the Middle Kingdom — now the hegemonic power in tungsten production — would have used the same blackmail tactic to force the Germans to move their factories as close as possible to the raw materials. The Chinese would have crushed any German lead in the cutting-tools industry, and would then have made off with the machine-tools segment — a pillar of the Mittelstand. It would have been the hold-up of the century! But the Germans saw the Chinese coming, and aligned instead with other tungsten producers (Russia, Austria, and Portugal, among others). ‘They preferred paying more for their resources to sustain the alternative mines and not depend on the Chinese,’ the Australian consultant told me.31 No matter.

Democracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism Through a Turbulent Century

by

Torben Iversen

and

David Soskice

Published 5 Feb 2019

This is the exact opposite of the almost century-long agreement in the Labour Party that the party did not concern itself with so-called “industrial questions,” notably about skills and vocational training; the whole issue of apprenticeships belonged to the craft unions, preeminently the engineers. This argument is reinforced by the fact that other social groups—for example, the Catholics, as well as the Protestant farmers, the Mittelstand, and so on—were already organized in their own parties; in general, representative parties can best expand support intensively within the broad social groups they represent. A similar argument applies to other protocorporatist countries, since they were characterized by representative parties linked to broad social groups.

…

Confessional parties were no exception: while Christian Democratic parties defended (within limits) the interests of the Church (though by no means always Rome) they were also, in the words of Manow and Van Kersbergen (2009), “negotiating communities” for the many different economic groups—handwork and the Mittelstand, smallholding peasants, larger peasants, Catholic unions, as well as landlords and sometimes business (see also Kalyvas 1996 and Blackbourn 1980). This reflected the fact that economic life was partially organized on confessional lines in the relevant countries. The adoption of PR in this setting did not require exceptionally rational forecasting: once the move to the national level of industry and politics made it apparent that the preexisting majoritarian institutions of representation were producing stark disproportionalities, PR was the natural choice to restore representivity.

…

The reason that Catholics with different economic interests remained with a party that is Catholic largely only in name is explained, we submit, by the interdependencies of these economic interests. The rural-urban, peasant-artisan-small employer-merchant cospecific asset network acted, if our hypothesis is correct, to create a peasant-Mittelstand constituency that had an incentive to remain within the Catholic party. Another way of putting this is to use Manow and van Kersbergen’s (2009) notion of Christian democratic parties as negotiating communities with a range of different economic interests in terms of income levels and hence redistribution, but also with a common interest in sharing and managing cospecific assets.

The Euro and the Battle of Ideas

by

Markus K. Brunnermeier

,

Harold James

and

Jean-Pierre Landau

Published 3 Aug 2016

In the United States, between 1980 and 2005, all net new private sector jobs were in companies less than five years old. By contrast, most large companies have tried to rationalize or downsize employment. German statistics also show small and medium enterprises as net creators of jobs in 2000–2005 (with a million new jobs) and large enterprises as losers (a loss of 800,000 jobs). German Mittelstand The German Mittelstand is geographically concentrated, above all in the south of the country, in the states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg (as well as to some extent in the southern states of former East Germany, Saxony and Thuringia). The historical heart of the German economy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Rhine-Ruhr basin, was just as dominated by large companies as France.

…

In the 2000s, Landesbanken had engaged heavily via offshore vehicles (mostly in Ireland) in the US subprime market. The Sachsen LB and the LB Rheinland-Pfalz needed to be rescued with public money and were then consolidated with the more solid LB Baden-Württemberg (where the traditional Mittelstand orientation was much greater). Another Landesbank, West LB, required €8 billion of assistance. IKB bank, a German institution that had its roots in the public sector encouragement of Mittelstand finance, was bailed out in 2007 and then sold to a private equity firm. One of the few bankers worldwide to be jailed as a consequence of the crisis was Gerhard Gribkowsky, head of risk management at Bayern LB.

…

Printed in the United States of America 13579108642 Contents 1 Introduction 1 PART I: POWER SHIFTS AND GERMAN-FRENCH DIFFERENCES 2 Power Shifts 17 Lethargy of European Institutions 18 The First Power Shift: From Brussels to National Capitals 20 The Second Power Shift: To Berlin-Paris and Ultimately to Berlin 27 After the Power Shift 33 3 Historical Roots of German-French Differences 40 Cultural Differences 41 Federalism versus Centralism 43 Mittelstand versus National Champions 48 Collaborative versus Confrontational Labor Unions 51 Historical Inflation Experiences 54 4 German-French Differences in Economic Philosophies 56 Fluid Traditions: Switch to Opposites 56 German Economic Tradition 59 French Economic Tradition 67 International Economics 74 PART II: MONETARY AND FISCAL STABILITY: THE GHOST OF MAASTRICHT 5 Rules, Flexibility, Credibility, and Commitment 85 Time-Inconsistency: Ex Ante versus Ex Post 86 External Commitments: Currency Pegs, Unions, and the Gold Standard 89 Internal Commitments: Reputation and Institutional Design 91 Managing Current versus Avoiding Future Crisis 94 6 Liability versus Solidarity: No-Bailout Clause and Fiscal Union 97 The No-Bailout Clause 98 Fiscal Unions 100 Eurobonds 111 Policy Recommendations 115 7 Solvency versus Liquidity 116 Buildup of Imbalances and the Naked Swimmer 117 Solvency 118 Liquidity 119 Crossing the Rubicon via Default 125 Sovereign-Debt Restructuring and Insolvency Mechanism 126 Fiscal Push: Increasing Scale and Scope of EFSF and ESM 127 Monetary Push 131 Policy Recommendations 133 8 Austerity versus Stimulus 135 The Fiscal Multiplier Debate 137 The Output Gap versus Unsustainable Booms Debate 143 Politics Connects Structural Reforms and Austerity 145 The European Policy Debate on Austerity versus Stimulus 148 Lessons and Policy Recommendations 153 PART III: FINANCIAL STABILITY: MAASTRICHT’S STEPCHILD 9 The Role of the Financial Sector 157 Traditional Banking 159 Modern Banking and Capital Markets 162 Cross-Border Capital Flows and the Interbank Market 166 10 Financial Crises: Mechanisms and Management 173 Financial Crisis Mechanisms 175 Crisis Management: Monetary Policy 185 Crisis Management: Fiscal Policy and Regulatory Measures 194 Ex Ante Policy: Preventing a Crisis 206 11 Banking Union, European Safe Bonds, and Exit Risk 210 Banking in a Currency Union 211 Safe Assets: Flight-to-Safety Cross-Border Capital Flows 222 Redenomination and Exit Risks 226 Policy Recommendations 233 PART IV: OTHERS’ PERSPECTIVES 12 Italy 237 Battling Economic Philosophies within Italy 237 Mezzogiorno: Convergence or Divergence within a Transfer Union 239 Italy’s Economic Challenges 242 Politics and Decline 245 13 Anglo-American Economics and Global Perspectives 249 Diverging Traditions 251 The United States: The Politics of Looking for Recovery 261 The United Kingdom: Brexit and the Politics of Thinking Outside Europe 267 China and Russia 279 Conclusion 286 14 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) 287 The IMF’s Philosophy and Crisis Management 289 The IMF’s Initial Involvement in the Euro Crisis 295 The IMF and the Troika 300 A Change in the IMF’s Leadership 304 Loss of Credibility: Muddling Through, Delayed Greek PSI 306 15 European Central Bank (ECB) 313 The ECB before the Crisis: Institutional Design and Philosophy 315 The ECB’s Early Successes and Defeats 325 The ECB and Conditionality 331 Lending and Asset Purchase Programs 343 Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) for European Banks 368 Taking Stock: Where Does the ECB Stand?

Vassal State

by

Angus Hanton

Published 25 Mar 2024

Learn from the Europeans too – structure and attitudes Continental Europe consciously stands against foreign incursions, a stance which contrasts with the warm reception the Americans have received in the UK. In resisting, Europe’s businesses are often helped by the way they are owned and integrated into the community. Some 60 per cent of the German economy is represented by the Mittelstand companies.11 The rough equivalent in Britain are the SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises), but the Mittelstand is a much bigger group and accounts for two-thirds of German exports. Usually these enterprises are family-owned, and were often set up after the Second World War with the expectation that they would be handed down the generations. By their nature they are fiercely independent and locally integrated: a sale to a US firm would usually be seen as both short-termist and socially unethical.

…

Employees have an emotional attachment to these companies, and the owners’ sense of social responsibility and local loyalty would usually stop them from even entertaining takeover discussions. Often Mittelstand companies have grown by doing one thing really well, with a focus on innovation and excellence. Their managers plan for long-term profitability, even at the cost of lower short-term profits. To varying extents, a similar Mittelstand of companies exists in France, Italy and Spain, where family ownership and community integration protect them from predators. Despite this, a few have succumbed, especially when there is a succession issue.

All Day Long: A Portrait of Britain at Work

by

Joanna Biggs

Published 8 Apr 2015

Despite this, Britain is still the eleventh largest manufacturer in the world, after India, largely because planes, cars and drugs are still made here by high-tech robots in co-operation with precision engineers. Our MPs have jealously looked to Germany’s Mittelstand, the substantial but unsexy ‘middle group’ of businesses that accounted for 52 per cent of the country’s output in 2011. Mittelstand businesses have fewer than 500 employees and a turnover below €50 million; they make unrivalled glass eyes or movie cameras or fish feed and then export them to the world. Freed of London, a family-founded business that makes specialised shoes needed in great quantities, is what a British Mittelstand firm would look like. There have been advances in pointe-shoemaking since 1929: US-based Gaynor Minden produces shoes with an ‘elastomeric’ toe of urethane foam which is supposed to never soften and St Petersburg’s Grishko adds silver to their shoes for its antibacterial properties.

…

PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that manufacturing jobs in the UK have diminished from 1 in 4 to 1 in 10 in a report of April 2009 called ‘The Future of UK Manufacturing: Reports of its Death are Greatly Exaggerated’. The Manufacturer magazine classes the UK as the eleventh biggest manufacturer in the world using figures from the World Bank and Wikipedia, and my definition of the Mittelstand is borrowed from the Financial Times lexicon. Details about Gaynor Minden and Grishko’s shoes can be found on their websites. The myth of Pygmalion first appeared in Book Ten of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the quotes from Capek’s play Rossum’s Universal Robots come from Acts One and Three of the Dover eBook edition.

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

Published 7 Jan 2021

One of the biggest, most successful manufacturers in Ravensburg was a family enterprise that eventually renamed itself Ravensburger.7 It resumed its production of puzzles and children's books, a business that continues to this day. And in Friedrichshafen, ZF, a subsidiary of the Zeppelin Foundation, re-emerged as a manufacturer of car parts. Companies like these, often from Germany's famous Mittelstand, i.e., the small and mid-sized businesses that form the backbone of the German economy, played a critical part in the post-war economic transformation. The Glorious Thirty Years in the West For many people living in Europe—myself included—the relief of the end of the war soon made way for the fear of another one.

…

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which as the name implied focused on a common market for a few key resources, had in the preceding years evolved to become the more all-encompassing European Economic Community (EEC). It allowed for a freer trade of goods and services across the continent. Many Mittelstand companies used that opening to set up subsidiaries and start sales in neighboring EEC countries. It was thanks in part to this increase in intra-regional trade that growth could continue in the 1970s. But some economic variables with a critical effect on growth, employment, and inflation, such as the price of energy, were not favorable.

…

Møller–Mærsk) [Denmark], 90, 167–168, 199–201, 202–207, 208, 213, 215 Mærsk Drilling, 205 Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møler ship, 200 Mærsk Oil, 205 Mærsk Tankers, 205 Magellan, Ferdinand, 101 Maisonrouge, Jacques, 11 Ma, Jack, 128 Majendie, Adam, 229 Majority Action, 216 Malaysia economic recession (1997) in, 98 inclusive approach to government in, 186 predicted economic growth (2020–2021) in, 65–66 Maluku islands spices, 97 MAN Energy Solutions (Denmark), 117–118 Mao Zedong, 56, 57 Marco Polo, 99 Marriage rights (Singapore), 123 Marshall, George, 6 Marshall Plan (US), 6–7 Marx, Karl, 105, 131 Massey University, 223 Maybach (German manufacturer), 4 Mazzucato, Mariana, 112, 184–185, 191, 234 McKinley, William, 133 McKinsey's Global Institute, 197 Medicaid, 135 Medicare, 135 Megacities, 159 Mellon, Andrew, 132 Mercedes (Germany), 9 Merkel, Angela, 79, 81, 83 #Me Too movement, 250 Mexico health coverage disparities in, 43 IT and Internet revolution role in expanding economy of, 137 “21st century socialism” of, 225 Micronesia, 181 Microplastics pollution, 50 Microsoft (US), 69, 126, 127, 137, 143, 209, 211 EU's anti-competition ruling against, 139–140, 141 Microsoft Office and Microsoft Windows products of, 139 Middle Eastern countries emerging markets in, 63 Locust–19 plague (2020) in, 176 OPEC membership among, 12 Migration increasing tendency of countries to stem, 177 as reminder of interconnectedness of people, 177 Migration Agency (IOM) [UN], 52 Milanovic, Branko, 45, 46, 84, 137, 138, 173 Milanovic's First Technological Revolutions, 45fig–46 Minimum rights rules (European Parliament) [2019], 243 Les Misérables (Hugo), 131 Mittelstand (Germany), 7, 12 Modern Company Management in Mechanical Engineering (Schwab, Kroos, Maschinenbau-Anstalten), 174, 175fig Modi, Prime Minister (India), 68 Modrow, Hans, 78 Mohammed, 99 Møller, A. P., 199 Møller, Arnold Mærsk Mc-Kinney, 203 Møller, Peter Mærsk, 199 Møller–Mærsk (Denmark), 167–168, 199–201, 202–207, 208, 213, 215 Moments of Life app (Singapore), 232 Monopolies antitrust legislation breaking up, 132–134, 135–136 AT&T, 127, 135 Big Tech, 127–129, 140–142, 145, 211 the EU Commission's Microsoft ruling on its, 139–140, 141 European regulators on the abuses of, 209 evolution of factual oligopolies of, 140–141 Microsoft successfully resisting breakup, 139 of the robber barons (19th century), 132–134 Standard Oil breakup (1911), 134 See also Competition Moran, Daniel, 160 Morgan, John Pierpont, 132 Moynihan, Brian, 214, 249, 250 Muslim traders (Middle Ages), 99–100 MYCL (Indonesia), 93–94, 96, 98, 114 MyInfo Business app (Singapore), 232 N Nadella, Satya, 69 Nagasaki bombing (1945), 5 Nanyang Commercial Bank (Hong Kong), 57–58 Narayen, Shantanu, 69 NASA's Earth Observatory, 160 National Academic of Sciences (US), 166 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 22, 44 National government.

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

and

Peter Vanham

Published 27 Jan 2021

One of the biggest, most successful manufacturers in Ravensburg was a family enterprise that eventually renamed itself Ravensburger.7 It resumed its production of puzzles and children's books, a business that continues to this day. And in Friedrichshafen, ZF, a subsidiary of the Zeppelin Foundation, re-emerged as a manufacturer of car parts. Companies like these, often from Germany's famous Mittelstand, i.e., the small and mid-sized businesses that form the backbone of the German economy, played a critical part in the post-war economic transformation. The Glorious Thirty Years in the West For many people living in Europe—myself included—the relief of the end of the war soon made way for the fear of another one.

…

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which as the name implied focused on a common market for a few key resources, had in the preceding years evolved to become the more all-encompassing European Economic Community (EEC). It allowed for a freer trade of goods and services across the continent. Many Mittelstand companies used that opening to set up subsidiaries and start sales in neighboring EEC countries. It was thanks in part to this increase in intra-regional trade that growth could continue in the 1970s. But some economic variables with a critical effect on growth, employment, and inflation, such as the price of energy, were not favorable.

…

Møller–Mærsk) [Denmark], 90, 167–168, 199–201, 202–207, 208, 213, 215 Mærsk Drilling, 205 Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møler ship, 200 Mærsk Oil, 205 Mærsk Tankers, 205 Magellan, Ferdinand, 101 Maisonrouge, Jacques, 11 Ma, Jack, 128 Majendie, Adam, 229 Majority Action, 216 Malaysia economic recession (1997) in, 98 inclusive approach to government in, 186 predicted economic growth (2020–2021) in, 65–66 Maluku islands spices, 97 MAN Energy Solutions (Denmark), 117–118 Mao Zedong, 56, 57 Marco Polo, 99 Marriage rights (Singapore), 123 Marshall, George, 6 Marshall Plan (US), 6–7 Marx, Karl, 105, 131 Massey University, 223 Maybach (German manufacturer), 4 Mazzucato, Mariana, 112, 184–185, 191, 234 McKinley, William, 133 McKinsey's Global Institute, 197 Medicaid, 135 Medicare, 135 Megacities, 159 Mellon, Andrew, 132 Mercedes (Germany), 9 Merkel, Angela, 79, 81, 83 #Me Too movement, 250 Mexico health coverage disparities in, 43 IT and Internet revolution role in expanding economy of, 137 “21st century socialism” of, 225 Micronesia, 181 Microplastics pollution, 50 Microsoft (US), 69, 126, 127, 137, 143, 209, 211 EU's anti-competition ruling against, 139–140, 141 Microsoft Office and Microsoft Windows products of, 139 Middle Eastern countries emerging markets in, 63 Locust–19 plague (2020) in, 176 OPEC membership among, 12 Migration increasing tendency of countries to stem, 177 as reminder of interconnectedness of people, 177 Migration Agency (IOM) [UN], 52 Milanovic, Branko, 45, 46, 84, 137, 138, 173 Milanovic's First Technological Revolutions, 45fig–46 Minimum rights rules (European Parliament) [2019], 243 Les Misérables (Hugo), 131 Mittelstand (Germany), 7, 12 Modern Company Management in Mechanical Engineering (Schwab, Kroos, Maschinenbau-Anstalten), 174, 175fig Modi, Prime Minister (India), 68 Modrow, Hans, 78 Mohammed, 99 Møller, A. P., 199 Møller, Arnold Mærsk Mc-Kinney, 203 Møller, Peter Mærsk, 199 Møller–Mærsk (Denmark), 167–168, 199–201, 202–207, 208, 213, 215 Moments of Life app (Singapore), 232 Monopolies antitrust legislation breaking up, 132–134, 135–136 AT&T, 127, 135 Big Tech, 127–129, 140–142, 145, 211 the EU Commission's Microsoft ruling on its, 139–140, 141 European regulators on the abuses of, 209 evolution of factual oligopolies of, 140–141 Microsoft successfully resisting breakup, 139 of the robber barons (19th century), 132–134 Standard Oil breakup (1911), 134 See also Competition Moran, Daniel, 160 Morgan, John Pierpont, 132 Moynihan, Brian, 214, 249, 250 Muslim traders (Middle Ages), 99–100 MYCL (Indonesia), 93–94, 96, 98, 114 MyInfo Business app (Singapore), 232 N Nadella, Satya, 69 Nagasaki bombing (1945), 5 Nanyang Commercial Bank (Hong Kong), 57–58 Narayen, Shantanu, 69 NASA's Earth Observatory, 160 National Academic of Sciences (US), 166 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 22, 44 National government.

Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex

by

Rupert Darwall

Published 2 Oct 2017

Schmidt, and Colin Vance, “Economic Impacts from the Promotion of Renewable Energy Technologies: The German Experience,” November 2009, http://www.rwi-essen.de/media/content/pages/publikationen/ruhr-economic-papers/REP_09_156.pdf, p. 15. 38Ibid., p. 14. 39Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, “German Mittelstand: Engine of the German Economy,” (undated), https://www.bmwi.de/English/Redaktion/Pdf/factbook-german-mittelstand,property=pdf,bereich=bmwi2012,sprache=en,rwb=true.pdf, p. 3. 40BDEW Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft e.V. (Federal Association of Energy and Water Industries), Strompreisanalyse März 2015, https://www.bdew.de/internet.nsf/id/9D1CF269C1282487C1257E22002BC8DD/$file/150409%20BDEW%20zum%20Strompreis%20der%20Haushalte%20Anhang.pdf. 41Eric Heymann, “Carbon Leakage: A Barely Perceptible Process,” Deutsche Bank Research, January 23, 2014, p. 1. 42Ibid., p. 9. 43Ibid., p. 8. 44Ibid., p. 1. 45Eric Heymann, “Capital Investment in Germany at Sectoral Level,” Deutsche Bank Research, January 9, 2015, p. 7. 46Ibid. 47Ibid., p. 1. 48Rupert Darwall, Central Planning with Market Features: How Renewable Subsidies Destroyed the UK Electricity Market (London, 2015), pp. 14–15. 49Bill Peacock and Josiah Neeley, “The Cost of the Production Tax Credit and Renewable Energy Subsidies in Texas,” Texas Public Policy Foundation, November 2012. 50Vladimir Rakov and Martin Uman, Lightning: Physics and Effects (Cambridge, 2003), Table 1. 51Mark Mills, “The Clean Power Plan Will Collide with the Incredibly Weird Physics of the Electric Grid,” forbes.com, August 7, 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/markpmills/2015/08/07/the-clean-power-plan-will-collide-with-the-incredibly-weird-physics-of-the-electric-grid/ (accessed October 2, 2015). 14.

…

A 2009 study found that the EEG increased the profits of Italian and Spanish coal-burning utilities, boosting the profits of Enel and Endesa by 9 percent and 16 percent, respectively.37 Overall, the paper came to a damning verdict on Germany’s renewables policy: “the EEG’s net climate effect has been equal to zero.”38 The most lasting damage caused by Germany’s failed climate policies is likely to be on the German economy. The EEG exemption was structured to benefit large energy consumers. This put the vast majority of small- and medium-sized businesses—the famed German Mittelstand, contributing to over half the nation’s total economic output and generating two trillion euros of annual revenues—on the hook for the rising costs of Energiewende.39 In the eight years to 2014, electricity prices for businesses consuming between 160 to 120,000 megawatt hours (MWh) a year increased by 35 percent, a lower rise than for households, as they did not have to foot the bill for exempting the largest electricity consumers.40 The value of the 90 percent exemption created a perverse incentive to overconsume electricity to keep above the threshold.

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by

Jonathan Haskel

and

Stian Westlake

Published 4 Apr 2022

They invest in R&D and design in order to produce cutting-edge products, in organisational development and training to increase factory productivity, and in software and data not only related to their own production but also as an adjunct to the physical goods they sell. If we consider rich countries that are thought to have particularly healthy manufacturing sectors, we usually find a story of sustained and distinctive investment in intangibles. The consultant Hermann Simon’s exploration of the German Mittelstand—Germany’s cadre of profitable, globally competitive medium-sized manufacturing businesses—finds that the sources of their profitability include a commitment to research, development, and innovation; strong, durable, information-rich relationships with suppliers and customers; and excellent workforce skills and organisation: all intangible assets.40 The success of the so-called developmental state in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea would be impossible without heavy investment in intangibles such as R&D, process design, and training that led to the emergence of globally competitive manufacturing businesses in sectors from shipbuilding to semiconductors.

…

See intellectual property rights (IPRs) Jefferson, Thomas, 184–85 Jennings, Will, 29 Jensen, Thais, 273n47 Jiang, Wei, 160 job conditions, 31–32 Johnson, Boris, 257–58 Johnson, Noel, 250 Johnson, Simon, 85 Johnstone, Bob, 145 Jona-Lasinio, Cecilia, 45 Jorgenson, Dale, 270n6 Juicero, 79 Kadyrzhanova, Dalida, 152 Kariko, Katalin, 22 Katz, Lawrence, 126 Kay, John, 36, 162 Kerr, William, 204 Keynes, John Maynard, 25, 148 Khan, Lina, 212 Khan, Zorina, 133 King, Mervyn, 36, 162 Kirzner, Israel, 124 Kleiner, Morris, 135 Kling, Arnold, 10, 85–86 knowledge economy, 54–56 Kortum, Sam, 176 Koyama, Mark, 250 Kremer, Michael, 265n1 Krieger, Joshua, 58 Krugman, Paul, 25, 189 Kuhn, Peter, 32 Lachmann, Ludwig, 124, 269n6 Lakonishok, Josef, 156 Leacock, Eleanor, 91 Leamer, Ed, 36 left-behind places, 28, 40, 76, 185, 195, 201–6 legitimacy, 143–44 Lerner, Josh, 172, 176 Leth-Petersen, Soren, 273n47 Lev, Baruch, 157 Levitt, Theresa, 268n24 Lian, Chen, 152 libertarianism, 250, 252 lighthouses, 100–104, 268nn24–26, 268nn30–31 Lindberg, Erik, 268n24, 268n29 Lindbergh, Charles, 140 Lorenzetti, Ambrogio, 3, 82, 83f Lost Golden Age, 37–40 Ma, Song, 160 Ma, Yueran, 152 Machin, Stephen, 232 Machlup, Fritz, 54–55 Manthorpe, Rowland, 257 market segmentation, 223 Markovits, Daniel, 32, 72–73, 231, 233 markup, 214–15 markups hypothesis, 46–47, 46f, 217–18 Marshall, Alfred, 64–65 Mass Flourishing (Phelps), 136 Matthew effect, 158, 189–90 Mauro, Paolo, 179–80 May, Theresa, 257 Mayer, Marissa, 208 Mazzucato, Mariana, 123, 136–37 McAfee, Andrew, 39–40, 59 McNally, Sandra, 232 McRae, Hamish, 28 mean reversion, 156 Meritocracy Trap, The (Markovits), 32, 72–73 Metcalfe, Robert, 277n22 metric tide, 128 Milgrom, Paul, 142, 245 Minoiu, Camelia, 152 mismeasurement hypothesis, 40 Mittelstand, 57 Mokyr, Joel, 43, 242, 258 Mondragon Corporation, 204–5 monetary policy, 14, 162–74, 168f, 170f monopolies, 211–12 Moore, John, 91 More from Less (McAfee), 59 Moretti, Enrico, 28–29, 186, 190 Motion Picture Patents Company, 2–3 movies, 2–3 Myers, John, 197 Nanda, Ramana, 172, 273n47 Narrow Corridor, The (Acemoglu and Robinson), 96 Nelson, Richard, 108 Nelson, Robert, 199 New Geography of Jobs, The (Moretti), 190 New Institutional Economics, 84 New Public Management, 252, 254 NIMBYism, 194–95, 200 Norquist, Grover, 252 North, Douglass, 10, 88, 92, 250 Occupy Wall Street, 148 Olson, Mançur, 110–11, 267n15 Open Data movement, 139 OpenSAFELY, 129 Organization Man, The (Whyte), 32 Orteig Prize, 140 Osborne, Matthew, 225 Ostrom, Elinor, 85, 106 pandemic.

SUPERHUBS: How the Financial Elite and Their Networks Rule Our World

by

Sandra Navidi

Published 24 Jan 2017

A family office platform facilitates networking so that families can benefit from each other’s experiences, coinvest, and leverage buying power. A Saudi Arabian family in the oil business might share insights on commodity prices, while a German industrialist provides intelligence on potential acquisition targets in the highly coveted German Mittelstand companies. A British billionaire can invite other families to participate in his socially responsible infrastructure investments, while an Indian entrepreneur might look for coinvestors in the telecom sector. The point is to obtain original information directly from the source rather than secondary, diluted information from a third party with incongruent interests.

…

See Long Term Capital Management “Lucky Sperm Club,” 137 Lutnick, Howard, 76 M Ma, Jack, 103 Macroeconomic trends, 70 Magic Mountain, The, 2 “Magic roundabout,” 134 Malloch-Brown, Lord Mark, 27 Manchurian Candidate, The, 67 Mankiw, Greg, 84 Mann, Thomas, 2 Mannesmann AG, 142–143 “Mansplaining,” 152–153 Marks, Howard, 90 Marrakech, 194 Marron, Donald, 209 Marx, Karl, 219 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 36, 81, 84, 149, 185 Masters, Blythe, 156 “Matchers,” 104 Matrix Advisors, 184 “Matthew Effect,” 52 McDonough, William J., 209 McKinsey, 87, 115, 152 Meade, Michael, 201 Media scrutiny, 136–137 Meditation, 62, 70 Medley, Richard, 43 Mentoring gap, 154–155 Meritocracy, 71, 80, 83, 213 Meriwether, John, 207–209 Merkel, Chancellor Angela banker interactions with, 174 at Davos, 114 in Euro crisis, 177 general references to, 39, 61, 193 Josef Ackermann and, 142–144 Merrill Lynch, 56, 179, 183 Merton, Robert, 52, 208 Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute Benefit, 76 Metzler, Jakob von, 136 Microsoft, 153 Middle East, 171 Milgram, Stanley, 18 Miliband, Ed, 137 Milken, Lowell, 191 Milken, Mike, 63–64, 129, 190–193 Milken Institute, 190, 192 Min Zhu, 27 Mindich, Eric, 109, 170 “Mind-reading,” 149 Minimum wage, 211 Minorities discrimination against, 148 integration of, 226 old boys’ network exclusion of, 82 Misinformation, 41 MIT. See Massachusetts Institute of Technology Mitchell, David, 87 Mittelstand, 123 Money. See also Wealth creation of, 32 network power of, 31 status associated with, 22 Mongolia, 171 Monness Crespi Hardt & Co., 110 Monoculture, 227 “Monopoly power,” 224 Monti, Mario, 84 Moore Capital, 109 Morgan Stanley, 89, 139 Moyers, Bill, 164 Moynihan, Brian, 115 Mozambique, 171 Murdoch, Elizabeth, 115 Musk, Elon, 69 Musk, Justine, 69 Myspace, 100 N Nadella, Satya, 153 National Bureau of Economic Research, 86 National Economic Council, 39, 165–166, 168, 184, 186 Nazarbayev, Nursultan, 171 Nazre, Ajit, 201 Negotiation, 153 Netherlands, 120 Netscape, 199 Network(s).

Platform Capitalism

by

Nick Srnicek

Published 22 Dec 2016

‘Microsoft’s Nadella Taps Potential of Industrial Internet of Things’. Financial Times, 22 April. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/c8e2e1d0-0861-11e6-a623-b84d06a39ec2.html (accessed 30 June 2016). Webb, Alex. 2015. ‘Can Germany Beat the US to the Industrial Internet?’ Bloomberg Businessweek, 18 September. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-18/can-the-mittelstand-fend-off-u-s-software-giants- (accessed 29 May 2016). Wheelock, Jane. 1983. ‘Competition in the Marxist Tradition’. Capital & Class, 7 (3): 18–47. Wile, Rob. 2016. ‘There Are Probably Way More People in the “Gig Economy” Than We Realize’. Fusion. Accessed 24 March. http://fusion.net/story/173244/there-are-probably-way-more-people-in-the-gig-economy-than-we-realize (accessed 29 May 2016).

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by

Alec Ross

Published 13 Sep 2021

Walking through the neighborhood in the university district of Bologna, Italy, where I lived during my time there as a professor, I am struck by the number and variety of locally owned bookstores, grocery stores, and myriad other specialty retailers that would never stand a chance in the United States. Germany, Switzerland, and Austria are home to millions of what are called the Mittelstand, family-owned businesses of small to moderate size that tend to measure their impact across generations rather than quarters and refuse to be acquired by larger firms. As firms have gotten bigger, they have also taken a larger share of the profits generated in the economy. The companies on the original Fortune 500 list earned a combined $8.3 billion in profit in 1955 (approximately $79 billion in 2019 dollars).

…

Li, Robin Lillis, Paddy Lincoln Tunnel LinkedIn Lionel lobbying Lockheed Martin Loeb, Daniel Lord Mayor of London Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) Luckey, Palmer Luff, Jonathan Luxembourg Lyft Lynch, Chris Macau Macy’s Ma Jun Malaysia Maniam, Aaron Mao Zedong Marcario, Rose market consolidation Marlboro Marxism Maryland mass mobilization Mattatuck Manufacturing Company Mauritius McCartin, Joseph McMillon, Doug Meany, George Medicaid Medicare Mehlman, Bruce Merck Merck, George W. mergers and acquisitions. See also market consolidation Mexico MI6 Michigan Microsoft Middle East. See also Gulf States; specific countries migration Miliband, David military power, traditional minimum wage Minnesota minority groups MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Mittelstand Molson Coors Monaghan, Paul Mongolia monopolies Montserrat Mook, Nate Morehouse College Moscow Narodny Bank Mounk, Yascha Mountaire Farms Mugabe, Robert Mussolini, Benito Namibia NASA National Guard National People’s Congress National Science Foundation Native Americans Nazism Nelson, Gaylord Netherlands New Deal New Jersey Newmark, Craig New Zealand Nigeria Nike Nixon, Richard Nordic countries.

Invention: A Life

by

James Dyson

Published 6 Sep 2021

This has always puzzled and saddened me, partly because I believe that a business loses something when it goes public but also because so many of these businesses end up in foreign hands, losing their way and ending up as vassal companies. Entrepreneurial family businesses, on the other hand, may be handed down through generations. Britain has remarkably few compared with other countries. In Germany, for example, there are the famous Mittelstand, medium-size private businesses, often multigenerational, as well as giants like BMW and our competitor Bosch. France has big family-owned fashion houses, Italy and Spain the same. The U.S. has the largest number of family businesses in the world, including Mars and Cargill, the agri-chemicals business.

…

See Dyson Farming Faurecia 217 Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios 288 Fenlands 247 Fiennes, Ranulph 128 Finch, John M. 74 First World War (1914–18) 51, 60, 179, 245, 252 Flos 281 focus group–led designing 45 Ford, Henry 44, 119, 214, 255 Foster, Norman 26, 28, 30, 120 Foxconn 59 France, Dyson in 174, 181, 183–84, 232 Friends 188 Fry, Jeremy 104, 268 Amway lawsuit and 95 Ballbarrow, offers to back 61, 84 influence upon JD 44–6, 67, 78, 86, 120, 147–48, 292, 306 JD begins to work for 32–34 Le Grand Banc and 60 motorized wheelchairs and 92, 94, 303 Prototypes Ltd 90 Sea Truck and 32–35, 37–39, 46, 49, 51–2, 59, 60, 61, 120 Fuller Brush company 90 Fuller, Buckminster 26, 30–31, 32, 52, 124, 142, 233 Fuller, Thomas 268 Furst, Anton 30–31 Gammack, Peter 104, 108, 179, 297 Chelsea Flower Show garden and 137 DC01 and 113, 127 DC12 and 186 DC35 Digital Slim and 154, 156, 158 Digital Motor and 148 EV, Dyson (electric vehicle) (N526) and 221, 222, 224 Pure Hot + Cool purifier and 164 recruited by JD 98–99, 104 Supersonic hairdryer and 170 Garbstore, The 300 Garnett, Andy 46, 184 gas-filled shock absorbers 41 General Electric (GE) 58 Genius of Britain 123 geodesic domes 30, 31, 142, 268 Germany, Dyson in 183–84 G-Force 94, 96–97, 186, 187, 299, 305 Gloster Meteor 57 Good Morning America 164 Goodwood Revival 56 Google Glass 141 Gordon, Alexander 200 Gove, Michael 269, 271, 272 Great Exhibition (1851) 262–63 Great Smog (1952) 209 Great Western Railway 261 “greenwash” 123, 226, 243–44 Gresham’s School 5–7, 8, 9, 11, 18, 142, 245, 289–91 Dyson Building 289–90 Gresley, Sir Nigel 40–41 GUS (General Universal Stores) 109–110 Gustin, Daniel 73 Habitat (exhibit), Montreal Expo 277 Hall, Jerry 138 Hardie, George 27 Harrison, George 49 Harvey Norman 183 Hastings, Sir Max 256 Heath, Edward 64 Heinkel 178 57 Henry IV, King of England 89, 159 HEPA filters 133, 161–62, 165, 235 Heyerdahl, Thor 61 Hill, Jane 27 Hillman Imp 267 Hitler, Adolf 43, 56 Hockney, David 17, 27, 28 Honda Accord 53 Civic 67 50 Super Cub 19–20, 22, 185 Honey, Jim 137, 138 Hoover 57, 82–83, 89, 107, 110, 116 Junior 82–83, 84, 85 hovercraft 6, 35, 91 Howe, Elspeth 118 Howe, Geoffrey 118 Hughes, Lucy 288 Hullavington Airfield campus, Dyson 177, 189, 198, 199, 224, 225, 228–34, 231, 235, 241, 278 Hunt, David 109, 111 Hunt, Tony 30, 31, 90, 120, 121 hydrolastic suspension system 51 ICI 68 Ideal Home Exhibitions 90 Imperial College London 26, 98–99, 127, 177, 262, 274, 282, 284 Dyson School of Design Engineering 177, 282 India, Dyson in 202–3 Indonesia 193, 194–95, 203 Industrial Revolution 40, 42, 248, 261, 265, 283, 296 infrared tracking technology 289 “Ingenious Britain: Making the UK the leading high tech exporter in Europe” (JD report) 270 injection molding 68–70, 133 Institute of Mechanical Engineers 43 Institution of Civil Engineers 43 International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 204, 206 Iona Appliances 97–98, 99, 100, 102, 105 Isle of Wight Pop Festival (1970) 64 Issigonis, Alec 17, 26, 37, 38–39, 50, 51, 52, 53–54, 55, 78, 88, 216, 217, 267 Jacob, Lord Justice Robin 158 Jaguar 8, 53, 74 D-Type 16 Mark 2 51 XJS 224 XK8 224 James and Deirdre Dyson Trust 288 James Dyson Building for Engineering, Cambridge University 281–82 James Dyson Foundation 239, 267–68, 271, 272, 273, 275, 281–2, 283, 284, 389–90, 313 Japan DC12 designed for 151 Dyson cyclone vacuum motor sourced from 123, 145, 147 Dyson Japan 185–87, 188, 194, 215 G-Force and 95, 96, 97, 99 Jaray, Paul 233 JCB 122, 293, 295 jet engine 56–58, 122, 148, 151, 265, 266, 293 JLR (Jaguar Land Rover) 225 John Lewis 113, 115, 116–18, 119 Johnson, Boris 233 Johnson, Jo 273–74, 275 Johnson Wax 99, 182 Jones, Allen 28 Junkers, Hugo 230, 232 Jupp, Simeon 98, 99, 104, 113 Kalms, Stanley 119 Karajan, Herbert von 54 Kettering, Charles 214 Kevlar 91, 268 Kier & Co. 232 Kimberly-Clark 162 King, Sir David 131, 211 King, Spen 223 King’s Road, London 23, 27, 300 Kirby 90 Kirk-Dyson 63, 64–80 Ballbarrow and see Ballbarrow cyclonic separators, first use of 73–74 JD ousted from 78–80 origins of 63, 64 Trolleyball and 77–78 Waterolla and 77, 77 Kirkwood, Stuart 70 Kite Light 21 Kleeneze Rotork Cyclon 89–90 Klimov, Vladimir Yakovlevich 58 Knickerbocker Corporation 74 Kon-Tiki raft 61 Kuenssberg, Laura 238 Lagerfeld, Karl 170 Lamella hangars 232 Lamont, Brian 109–110 Land Rover 47, 49, 94, 217, 223, 225 lean engineering 123–24, 244 Le Corbusier 24, 28 Ledwinka, Hans 233 Lee Hsien Loong 225 Lee Kuan Yew 190 Lefèbvre, André 50, 55, 87–88 Le Grand Banc 60, 61, 94 Lightcycle task lamp, Dyson 202–3 Linacre, Edward 287 Linolite 120, 121 Linpac 104, 249 lithium-ion batteries 152, 159, 175, 177, 212, 213, 214, 224 Littlewood, Joan 31–32 Littlewoods 109, 110, 115 Ljungström, Gunnar 50 London Fire Brigade 48 London Olympics (2012) 42 Lutyens, Edwin 230 Lux meters 289 MacDonald, Ramsay 230 Magès, Paul 41, 55 Maigue, Carvey Ehren 286–87 Malaysia 39, 125, 189, 190, 191, 192, 195, 196, 198, 281 Malmesbury campus, Dyson 78, 130, 137, 150, 170, 182, 189, 192, 195, 241, 245, 274, 275, 277, 279, 293, 299 D4 building 211 DIET Village 276, 277, 279 D9 building 126 The Hangar 125 Lightning Café 126 Morris Mini Minor at 54 origins of 78, 120–25, 120–21 renewal of offices and upgrading of laboratories 198 Rolls-Royce RB.23 Welland at 56 management structure, Dyson 237–38 manufacturing, British attitudes toward 39–44, 57–59, 64–67, 189–93, 203–8, 236–41, 259, 260–91 Maple Tree 200–1 MarinaTex 288 Masaru Ibuka 54 May, Theresa 203, 225 McCullin, Don 127 Mechanics’ Institute 261–62 Meikle, Andrew 248 Meningitis Research Foundation 288 Michelin 55, 217, 277 middle-class buyers, Dyson products and 119 Mig-15 fighter 58 Millennium Experience 263 Minards, Ian 223–24 Mini 17, 26, 28, 29, 38, 45, 49–51, 53, 54, 55, 88, 125, 216, 217, 267, 293–94 Ministry of Defence 91, 228 Minoru Mori 186 MIRA (Motor Industry Research Association) wind tunnel 221 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries 282 Mittelstand (medium-size private German businesses) 295 Miyake, Issey 139–41, 186 Model T, Ford 214 MOM 288 monocoque 51, 224 Moore, Charles 135, 137 Morris Marina 53, 67 Mini Minor 54 Minor 12, 17, 28, 43, 53 1100 37, 51 Oxford 22 Traveller 17 Morris, Estelle 269 Morita, Akio 38 Morton, Lord 121, 122 Moulton, Alex 51–53 Moulton bike 52–53, 268 Moulton, John Coney 51 Mr.

Paint Your Town Red

by

Matthew Brown

Published 14 Jun 2021

In Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Spain and France, community and agricultural cooperative banks make up as much as 64% of the banking market.10 Locally focused mutual banks increase the democratic oversight of the depositors and ensure that money deposited is then lent out into the local economy. This is one of the ways that the German Mittelstand tier of SMEs has been developed and financed, and is key to reflating an economy at the scale of a combined authority. The CSBA says that in contrast to the bailouts needed in the UK and elsewhere, small local banks in Germany were able to continue lending as usual throughout the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis, enabling them to avoid the predicament that engulfed their larger competitors.

The Downfall of Money: Germany's Hyperinflation and the Destruction of the Middle Class

by

Frederick Taylor

Published 16 Sep 2013

The state and the communities must guard against letting the officials feel that they are being given up to the storms of economic developments without protection. The same went for white-collar staff in industry, who, unlike their manual co-workers, were unwilling to compromise their hard-won and precious social standing by going on strike for higher wages. As for small businessmen and craftsmen, the backbone of the much-admired German Mittelstand, many found their businesses shut down as inessential to the war effort, starved of raw materials diverted to more vital sectors or simply bereft of customers.22 They represented millions more Germans subjected to dramatically reduced incomes and loss of status – and accordingly ripe to blame those seen as profiteering.

…

A sample of working-class families’ living costs, for instance, reveals that rent made up 19.7 per cent of expenditure in 1907, 8 per cent in 1917, 7.3 per cent in 1919, and, at the climax of the inflation, a mere 0.3 per cent!22 This was, of course, bad news for landlords. While it might be that they were able to pay off mortgages quickly because of the inflation, the financial return on their properties was miserable. Landlords, often not wealthy people but simply once-prosperous members of the Mittelstand – skilled artisans, shopkeepers, small tradesmen – who had invested in rental property as a form of saving and supplementary income, made up yet another aggrieved class in Weimar Germany. Given the virtual cessation of residential construction during the war, and the lack of incentive to build for rent after peace came, the housing shortages, particularly in the big cities, became even more chronic.

Start It Up: Why Running Your Own Business Is Easier Than You Think

by

Luke Johnson

Published 31 Aug 2011

Not surprisingly, the business underperformed and he was replaced. Another characteristic of top managers is that they manage for the long term. Sudden strategic moves to suit quarterly targets or shorter-term bonus measures are damaging. Family stewardship often beats publicly traded or private equity as a form of ownership for this reason. Germany’s Mittelstand companies, which are principally family owned, are the backbone of their economy: often world-class operations that adopt prudent financing, and invest in capital expenditure and research and development. Incentives at all levels tend to be long term. The best managers have real domain knowledge.

The People vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (And How We Save It)

by

Jamie Bartlett

Published 4 Apr 2018

In a similar fashion, productivity in the UK increased by 80 per cent between 1973 and 2011 (although it is still low by the standards of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) but the hourly compensation of the median worker went up by only 10 per cent in real terms. All over the world – including in socialist Sweden and Mittelstand Germany – top earners and top jobs have been doing just fine, while for a lot of people in the middle and bottom, earnings and wealth haven’t increased at all in real terms since the 1970s. There are other forms of inequality that no one is thinking about at play here too. As a general rule, technology empowers those who have either the money or the skills to take advantage of it.

The Default Line: The Inside Story of People, Banks and Entire Nations on the Edge

by

Faisal Islam

Published 28 Aug 2013

The success in forklift trucks was replicated in other industries and across their supply chains. Germany has been brilliant at identifying and exploiting specialist high-quality export niches with a global market, and has spawned a range of medium-sized companies, the so-called Mittelstand, to supply these markets with items ranging from conveyor belts to industrial springs. One company has cornered the world market in antennae for skyscrapers. The top Mittelstand companies adhere to the ‘80 per cent model’ – an 80 per cent global market share, and 80 per cent of production exported. Such products are rarely glamorous, but all, in retrospect, are rather obvious commercial bets as emerging economies develop.

America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism

by

Anatol Lieven

Published 3 May 2010

The American middle classes may not have suffered so badly economically— although that situation may be changing as the economy ceases to generate adequate numbers of "middle-class" jobs—but the nation's openness to immigration means that the middle classes have suffered even more from demographic pressure and the cultural tension and change that immigration has encouraged. This clash has generated much of the electricity which drives the turbines of nationalism and other radical political tendencies across the world. A classic example is the role of the endangered and declining nobility, peasantry and traditional middle class (Mittelstand) of Germany in generating German "radical conservatism," and the new nationalism which was its intimate partner, in the later nineteenth century.14 These social strata generated movements which often combined radical economic protest against the new capitalism with intense nationalism and cultural conservatism.15 And as the example of the Prussian nobility shows, absolute decline does not necessarily have to occur to drive an old elite in a radical direction—the threat can be enough.

…

Cf. Bennett, Party of Fear, pp. 27-182; Hofstadter, Paranoid Style, pp. 19-23. 13. Hardisty, Mobilizing Resentment, p. 32. 14. See John Weiss, Conservatism in Europe, 1770-1945: Tradition, Reaction and CounterRevolution (London: Thames and Hudson, 1977), pp. 71-89. For the role of the small town Mittelstand and the effects on later German nationalism of the destruction of 239 N O T E S TO P A G E S 93-96 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. their ancient social and political order by the modern state, see Mack Walker, German Home Towns: Community, State and General Estate, 1648-1817 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), especially pp. 405-431.

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 4 Mar 2003

The biggest were the “universal banks” that managed to be commercial banks, investment banks, and investment trusts all rolled into one. (J. P. Morgan achieved something similar, but only by getting around state laws, rather than being encouraged by them.) Deutsche Bank (formed in 1870) and Dresdner Bank (1872) concentrated on financing large-scale industry, leaving smaller banks to concentrate on the Mittelstand of medium-sized family firms that also powered the country’s success. In 1913, seventeen of the biggest twenty-five joint-stock companies were banks. Universal banks financed almost half of the country’s net investment. Bankers also sat on the supervisory boards of all Germany’s great industrial companies, providing advice and contacts as well as capital (it was the bankers that organized Siemens’s merger with German Edison in 1883).

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by

Charles Handy

Published 12 Mar 2015

The list includes schools, hospitals, sports teams, clubs, even families; once these had reached what seemed to be the optimum size any further addition would be pointless, might even be damaging. For these organisations the key question was not bigger but better, which, of course, begged the question, better in what way? We are back to those unanswered questions, why? what? and for whom? Better not bigger is also the watchword of many of Germany’s Mittelstand family businesses. These medium-sized businesses, mostly family-owned and mostly in manufacturing, are the mainstay of the German economy. They treat debt with suspicion, invest for the long term and shun the stock market. The market leaders in many niche products, their aim is to do one thing really well.

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by

Ruchir Sharma

Published 5 Jun 2016

In these cases, blood ties may not be the enemy of clean and open corporate governance, particularly in cases where the family has stepped back to play an ownership and oversight role in a publicly traded company, leaving the management of the company in professional hands. This can be a strong combination because the family keeps the company focused on the long term, and the market keeps it open to scrutiny. This, for example, is the model in Germany, were billionaire families control some of the world’s most productive companies, including many of the Mittelstand companies that drive the flourishing manufactured export sector and are more a source of pride than resentment. This also seems to be the case in Italy and France, which have seen quite a few new names appearing on recent billionaire lists. Many of these new entrants derive their wealth from old family companies and have risen slowly from the multimillionaire ranks to the billionaire lists.

…

This move has been attacked as a “beggar thy neighbor policy” by fellow members of the Eurozone, who now share a continental currency with Germany and can no longer respond to falling German labor costs by allowing their own national currencies to fall. But Germany has also pushed reform in many other ways: It has a core of medium-size industrial companies known as the Mittelstand, whose family owners are known for thinking in the long term, and they have made smart strategic use of the abundant supply of cheap, well-educated labor that opened up to them after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Many have invested in new factories in Poland and the Czech Republic, as well as in the United States and China, effectively exporting the German industrial model. 2010 was the first year in which German car companies made more cars abroad than at home, helping to forge what is arguably the leading global industrial power.

The Metric Society: On the Quantification of the Social

by

Steffen Mau

Published 12 Jun 2017

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255699242_Why_Do_Credit_Rating_Agencies_Issue_Unsolicited_Ratings_And_Why_Do_Issuers_Solicit_Ratings_If_They_Can_Get_Them_For_Free. Gantz, John, and David Reinsel (2012) ‘The digital universe in 2020: big data, bigger digital shadows, and biggest growth in the Far East’, https://www.emc.com/collateral/analyst-reports/idc-the-digital-universe-in-2020.pdf. Geiger, Theodor (1930) ‘Panik im Mittelstand’, Die Arbeit. Zeitschrift für Gewerkschaftspolitik und Wirtschaftskunde 7/10 (pp. 637-54). Gilbert, Paul (2000) ‘The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: the role of the evaluation of social rank’, Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 7/3 (pp. 174-89). Gillespie, Tarleton (2012) ‘Can an algorithm be wrong?’

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by

Stewart Lansley

Published 19 Jan 2012

In the UK, and to a lesser extent the US, the investment process was much more dominated by impersonal institutions obsessed with short-term returns and with little interest in the individual companies in which they invest.328 In continental Europe, in contrast, companies have been under less pressure for short-term performance from their shareholders and the banks that have supported them. A large chunk of Germany’s banking system consists of a network of regional banks aimed at supporting the Mittelstand, local small and medium-sized businesses. In the UK, small firms have suffered from the increasing concentration of financial power in the large London-based boardrooms. An empirical study of the United States found, for the period from 1973 to 2003, a negative relationship between the growth of ‘financialisation’—the growing importance of financial markets—and the real economy, leading to a decline in real investment at the firm level.

Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets

by

Brett Scott

Published 4 Jul 2022

City to Ban Cashless Stores’, Wall Street Journal, 7 March 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/philadelphia-is-first-u-s-city-to-ban-cashless-stores-11551967201 8. Shedding and Re-skinning Commerzbank has set up its own fintech incubator: See Commerzbank’s description here https://www.commerzbank.de/en/nachhaltigkeit/markt___kunden/mittelstand/main_incubator/main_incubator.html Mel Evans refers to this phenomenon by which coldly commercial institutions patronise art as ‘artwash’: Mel Evans, Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts (Pluto Press, 2015) a Kentridge video animation called ‘Second Hand Reading’: The video can be seen here https://www.youtube.com/watch?

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 14 May 2014

Famous for its budget wrangles, its extremes of partisanship, gerrymandering, and money politics, its pathetic levels of voter participation, its ruinous ballot initiatives, its absurdly complicated structure, and its crumbling infrastructure, California government has been big, broke, and inefficient. The gap between Palo Alto and Sacramento is repeated all across the West: Wall Street operates in a different time zone from Washington, D.C.; Bavaria’s Mittelstanders, Milan’s fashion moguls, and Soho’s multimedia entrepreneurs work to different rules (and hours and pay) from the politicians in Berlin, Rome, and Whitehall. But there is no political distemper that cannot be found in its most extreme form in California. It is hard to think of anywhere else where the rhetoric of small government and the reality of big government have collided so spectacularly—and where the failures of Milton Friedman’s half revolution have been demonstrated so clearly.

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 10 Apr 2016

Unlike the preceding period, it was a time when people contended that “small is beautiful” (to quote the title of another influential book, by Ernest F. Schumacher, published in 1973). The future no longer seemed to belong to industrial giants like IBM, Boeing, Ford, and Westinghouse. It was a time to celebrate the flexibility and small scale of the German Mittelstand (mid-sized manufacturers) and the family enterprises in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Japan’s rise began to look unstoppable. No one took notice of China yet. And of course the end of communism was not foreseen at all. A final wave of literature that I want to mention here is from the 1990s. It was dominated by the Washington Consensus (a set of policy prescriptions that emphasized deregulation and privatization) and the forecasting of the “end of history” (the title of an influential 1989 article by Francis Fukuyama, leading to the book The End of History and the Last Man [1992]).

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Jan 2017

In any case, if the exceptional openness of the British economy to foreign ownership has contributed to the decline story the bigger share of blame must lie with that familiar bogeyman of short-termism: the narrow focus on shareholder returns and the active market in corporate control stimulated by investment banks in the City of London that often creates a disincentive to plan and invest long. The Anglo-Saxon corporate governance model puts British businesses at a disadvantage compared with their competitors in Europe and Asia. German companies, particularly the Mittelstand of medium-sized family businesses, tend not to be quoted on the stock market. Managers can plan ahead—in developing new export markets, for example—without fear of a takeover, losing their job, or losing out on bonuses. The greater weight that shareholders, and stock market sentiment, have in big British businesses means managers are often on a treadmill of maximising short-term earnings.

Revolution Française: Emmanuel Macron and the Quest to Reinvent a Nation

by

Sophie Pedder

Published 20 Jun 2018

Such experiences were repeated in different corners across the country. France launched plenty of small firms, especially after it simplified the registration of new companies under Nicolas Sarkozy, when the country introduced the ‘auto-entrepreneur’ regime for new microbusinesses. But it singularly failed to develop a French version of the German ‘Mittelstand’, those mid-sized, export-oriented, mostly family-run industrial firms. The competitiveness of French industry, and with it economic growth, seemed to be on a path of inexorable decline. Between 2005 and 2010 France’s share of world exports shrank by almost 20 per cent, a decline exceeded within the eurozone only by Greece.

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by

Rebecca Henderson

Published 27 Apr 2020

By some measures it is ranked as the world’s most innovative economy.70 Nearly 25 percent of German GDP is in manufacturing (in the United States, for comparison, manufacturing makes up only about 15 percent of output). The World Bank’s 2016 Logistics Performance Index ranks Germany’s logistics performance and infrastructure as the best in the world.71 Eight of the world’s one hundred largest companies are German, and the country also boasts a highly successful Mittelstand, or group of globally successful small and middle-sized firms. Of the world’s roughly 2,700 “hidden champions”—firms that are in the top three in their industry and first on their continent and have less than €5 billion in sales—almost half are in Germany. By one estimate these relatively small firms have created 1.5 million new jobs, grown by 10 percent per year, and registered five times as many patents per employee as large corporations.

The Pyramid of Lies: Lex Greensill and the Billion-Dollar Scandal

by

Duncan Mavin

Published 20 Jul 2022

NoFi was founded in 1927, in Bremen, at the height of the Weimar Republic. For most of its existence, the small bank had been a bit of a disaster, struggling from one near-collapse to the next and switching owners every few years. It had just a handful of branches and a few dozen staff. The bank took deposits from ordinary Germans, made loans to Germany’s Mittelstand group of small businesses, and provided financing for mortgages and car buyers too. Since the 1960s, NoFi had also been a provider of factoring services. Over the past few decades, NoFi had been passed from new owner to new owner. Each time, a different strategic plan was put in place, but the bank mostly languished.

Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?

by

Thomas Geoghegan

Published 20 Sep 2011

Here, it’s whether Obama or Pelosi or Reid is “winning” or “losing,” without all that much interest as to what exactly is being won or lost. Here I could talk politics with H. and S. and many others without anyone ever mentioning the name of “Schroeder” or “Kohl.” Ah, I wish I could explain it. Well, let me try an example from that first night. We were talking about the Mittelstand, the middle-sized manufacturers. “They’re being cut out by the government,” S. said. “Cut out of what?” I said. “Research. Basic research. Now the global companies get it all.” “Do the two of you—do you really think this will affect your lives?” “Of course,” S. said, and looked annoyed. “The problem is, Germany is not interested in research—” “Who is?”

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by

Michael Bhaskar

Published 2 Nov 2021

All figures below taken from this paper unless stated otherwise. 48 Ibid. 49 See for example Wong (2017) 50 Bloom et al. (2020) 51 Cowen (2011) 52 Ibid., pp. 14–15. These figures are calculated by Cowen in 2004 dollars. 53 Thanks to Mikko Packalen for this and many other suggestions. 54 See for example Erixon and Weigel (2016). It could be argued that European innovation is concentrated in smaller companies like those forming the German Mittelstand. However that then prompts the question of why Europe cannot scale innovative companies – another but related problem in executing big ideas. 55 Erixon and Weigel (2016), p. 11 56 Greenspan and Wooldridge (2018), p. 395 57 Naudé (2019) 58 Cowen (2018a), p. 6 59 Ibid., p. 73., see also Shambaugh et al. (2018).

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by

Linda Yueh

Published 4 Jun 2018

Despite these challenging times, Schumpeter witnessed the impressive wholesale reinvention of business, which fed into his theory of ‘creative destruction’ where the innovators flourish. Small and medium-sized German businesses, mostly family owned, upgraded their operations and became known globally for their quality. Many of these Mittelstand companies are still around today, for example Hohner harmonicas, Krones labelling machines and the Jil Sander fashion label. Big businesses also reinvented themselves. Five of Germany’s ten largest firms manufactured steel at the time of his move to Bonn. By the time he left, several had merged to become Vereinigte Stahlwerke (United Steelworks), which was the biggest steel and mining company in Europe.

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by

Linda Yueh

Published 15 Mar 2018

Despite these challenging times, Schumpeter witnessed the impressive wholesale reinvention of business, which fed into his theory of ‘creative destruction’ where the innovators flourish. Small and medium-sized German businesses, mostly family owned, upgraded their operations and became known globally for their quality. Many of these Mittelstand companies are still around today, for example Hohner harmonicas, Krones labelling machines and the Jil Sander fashion label. Big businesses also reinvented themselves. Five of Germany’s ten largest firms manufactured steel at the time of his move to Bonn. By the time he left, several had merged to become Vereinigte Stahlwerke (United Steelworks), which was the biggest steel and mining company in Europe.

Greater: Britain After the Storm

by

Penny Mordaunt

and

Chris Lewis

Published 19 May 2021

German capitalism mixes seemingly impossible ingredients, like strong trade unions and efficiency, high-cost workers that also compete in manufacturing, and generous unemployment benefits alongside low levels of unemployment. It also has a strong base of independent, small and medium-sized family-run manufacturers called the Mittelstand. (Literally, the middle class.) This is partly the reason that Germany overtook China in 2017 with the world’s largest trade surplus.62 Germany’s economic strength is a result of its own particular circumstances. In the mid-1990s, it suffered with the twin problems of high debt and high unemployment.

Super Continent: The Logic of Eurasian Integration

by

Kent E. Calder

Published 28 Apr 2019

This dynamic Central European industrial complex is becoming a key global manufacturing base, focusing on precision machinery and chemicals as well as autos and electronics, that generates 42 percent of the European Union’s entire manufacturing value-added exports.60 This competitive cluster, drawing investment from throughout the world, is sourcing increasing quantities of components in China, while Chinese firms move up the value chain into Central Europe by acquiring German Mittelstand (small and medium-sized) manufacturers and robotics firms as well.61 German logistics firms like DHL and DB Schenker Logistics, as well as massive Chinese intermodal transport conglomerates like COSCO and China Railway Corporation, compete to control railways and ports, with the BRI conferring major strategic advantages on the Chinese.62 Arctic Transit Routes There are, finally, also the transit routes from Northeast Asia to Europe across the Arctic seas, recently termed the “Polar Silk Road” by the Chinese government.63 These routes are also shorter than the traditional maritime routes around the southern rim of Eurasia, and could be efficient if only frigid conditions did not block the way.

Investing Amid Low Expected Returns: Making the Most When Markets Offer the Least

by

Antti Ilmanen

Published 24 Feb 2022

Vissing-Jørgensen and Moskowitz (2002), Kartashova (2014), and Randl-Westerkamp-Zechner (2018) discuss the relative sizes and relative profitability of listed and unlisted sectors. Early research suggested that these unlisted firms are less profitable than the listed firms, but the new research challenges this finding. Unlisted private sector is likely as important outside the US, famously including the “Mittelstand” firms in Germany and huge family-owned private ventures in the Far East. 4 The results are broadly similar if I use their longest common sample for housing and equities (1891–2015), though inflation was lower, and equity returns came about 1% more from income than capital gains. 5 See Demers-Eisfeldt (2021) on US housing, Chambers-Spanjers-Steiner (2021) on UK real estate, and Pagliari (2017) on US commercial real estate.

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by

Harold James

Published 15 Jan 2023

The lower middle classes and the middle classes lost precisely the elements that made their lifestyles distinct from the working class: the gut bürgerliche Küche (the hallmark of respectable working-class eateries) vanished with the peace. The first wartime survey of the War Committee for Consumer Interests reported a “grinding down of the Mittelstand [middle orders] and the rise of a ‘barbaric’ economy in which there are only ‘rich and poor.’”25 In order to anticipate future grain shortages, the pig population was drastically reduced in early 1915 in the so-called Schweinemord, with much of the resulting meat wasted because of inadequate conservation and canning techniques.

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by

Philippe Legrain

Published 22 Apr 2014

Lufthansa is Europe’s biggest airline by passengers, but lags far behind Easyjet by profits.469 Majority-state-owned Deutsche Bahn, which owns Arriva in Britain, is Europe’s biggest railway operator, but far from its best. While Germany has plenty of big companies, it is perhaps best known for its mid-sized ones, the Mittelstand. These are mostly manufacturers which focus on machinery, auto parts, chemicals and electrical equipment. Many have carved out specialised niches so narrow that they face little global competition. Their perceived virtues – notably the patient, long-term view that these often family-owned firms can take – contrast with the adrenaline-rush, rollercoaster ride of Anglo-American financial capitalism.

Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

by

Parag Khanna

Published 18 Apr 2016

According to the WTO, 80 percent of global trade is supported by financial institutions, but postcrisis regulations (such as Basel III, which requires banks to hold more capital onshore) inadvertently choked this crucial conduit between the financial sector and the real economy that helps companies produce exportable goods and has proven to be a reliable investment given its low default rate. Funds such as the European Investment Bank and the Abraaj Group have stepped in to back region-wide funding exchanges for the Middle East and Africa so that SMEs can more easily raise capital. Germany has five times more such Mittelstand companies than the entire United States (which has four times as many people), indicating a much greater emphasis on rooted entrepreneurs such as toolmakers who can benefit from trade finance to expand to growth markets in Asia. The spread of European SMEs into Asia and ASEAN SMEs into the rest of Asia, Africa, and back to Europe is a testament to how channeling global capital to local companies creates real and productive new flows.

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by

Philip Coggan

Published 6 Feb 2020

West Germans owned just 200,000 cars in 1948 but 9 million by 1965.14 The West German economy became an export machine, driven by the production of capital goods. An enduring aspect of the German system was that the big manufacturers had a strong relationship with a group of smaller suppliers, known as the Mittelstand. The French economy laid a greater emphasis on planning than did the German, and had particular success in car manufacturing, thanks to Citroën, Peugeot and Renault. Italy had its strengths in Fiat, the car manufacturer, chemicals companies like Edison, and the fashion industry. The Netherlands had Philips, the electronics group, a successful chemicals industry, and, from the late 1950s onwards, enjoyed a gas boom.

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

by

Joshua B. Freeman

Published 27 Feb 2018

The German model of codetermination, which gave an extensive role to unions in corporate management, and high wages and generous social benefits (including large profit-sharing payments) helped ensure peaceful labor relations. Unlike contemporary American manufacturers, Volkswagen did not fear that workers might take advantage of concentration to disrupt production and force their will on the company.58 Though the Mittelstand of small and medium-sized enterprises continued to dominate the West German and later unified German economy, there were, besides Volkswagen, some manufacturers with very large plants. The chemical giant BASF, once part of IG Farben but reformed as a separate entity after World War II, concentrated production at its long-established complex along the Rhine in Ludwigsafen.

Trust: The Social Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 1 Jan 1995

Because they were export oriented, the potential inefficiencies of domestic monopoly were minimized; large German firms were kept honest by large firms in other countries rather than by each other. Although the German economy is dominated by large firms, it (like Japan) also has a large and dynamic small-firm sector, the so-called Mittelstand. Family businesses are as prevalent and important in Germany as anywhere else; indeed, there are more cases of families’ retaining management control of large businesses in Germany than in the United States.12 But the family has never constrained the creation of large, professionally managed firms to the degree it has in China, Italy, France, or even Britain.

Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech

by

Jamie Susskind

Published 3 Sep 2018